|

Arts >

Music >

Reggae, Ska, Dub poetry

20th, 21st century > Jamaica, UK

Timeline

in articles, pictures and podcasts

UB 40 UK

formed in December 1978

in Birmingham, England

https://www.theguardian.com/music/

ub40

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

UB40

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

UB40_discography

https://www.npr.org/2021/11/07/

1053338020/astro-ub40-terence-wilson-dies-at-age-64

Steel Pulse UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2017/may/05/

eddie-chambers-black-british-identity-in-pictures

Winston Rodney Jamaica

better known

by the stage name Burning Spear

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Burning_Spear

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2022/aug/08/

burning-spear-racism-rebellion-reggae-power-heal-spiritual

https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2001/aug/02/

artsfeatures4

https://www.theguardian.com/culture/1999/aug/11/

artsfeatures2

https://www.nytimes.com/1980/10/15/

archives/the-reggae-burning-spear.html

https://www.nytimes.com/1976/08/10/

archives/music-burning-spear-jamaicans-on-first-american-tour-

emerge-as.html

Pablo Moses Jamaica

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Pablo_Moses

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2005/mar/04/

https://www.nytimes.com/1987/09/18/

arts/biko-memorial.html

1

https://www.nytimes.com/1984/11/11/

arts/critics-choices-077161.html

https://www.nytimes.com/1984/01/02/

arts/pop-pablo-moses-performs.html

Bunny Wailer Jamaica

Bunny Wailer

(born Neville

Livingston)

http://www.npr.org/2016/05/18/

478562770/on-anniversary-tour-bunny-wailer-is-still-a-blackheart-man

The Gladiators

Jamaica

https://www.nytimes.com/1984/11/25/

arts/with-its-crooners-and-toasters-reggae-is-thriving.html

Third World

Jamaica, USA

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Third_World_(band)

https://www.nytimes.com/1982/03/28/

arts/reggae-the-third-world-at-the-ritz.html

Linton Kwesi Johnson

Jamaica, UK

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Linton_Kwesi_Johnson

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Forces_of_Victory - 1979

Max Romeo Jamaica

1944-2025

(born Maxwell Livingston

Smith)

His early hits were filled with sexual

innuendo.

But he later switched to a soulful political

message

that resonated in 1970s Jamaica and beyond.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/19/

arts/music/max-romeo-dead.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Max_Romeo

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/19/

arts/music/max-romeo-dead.html

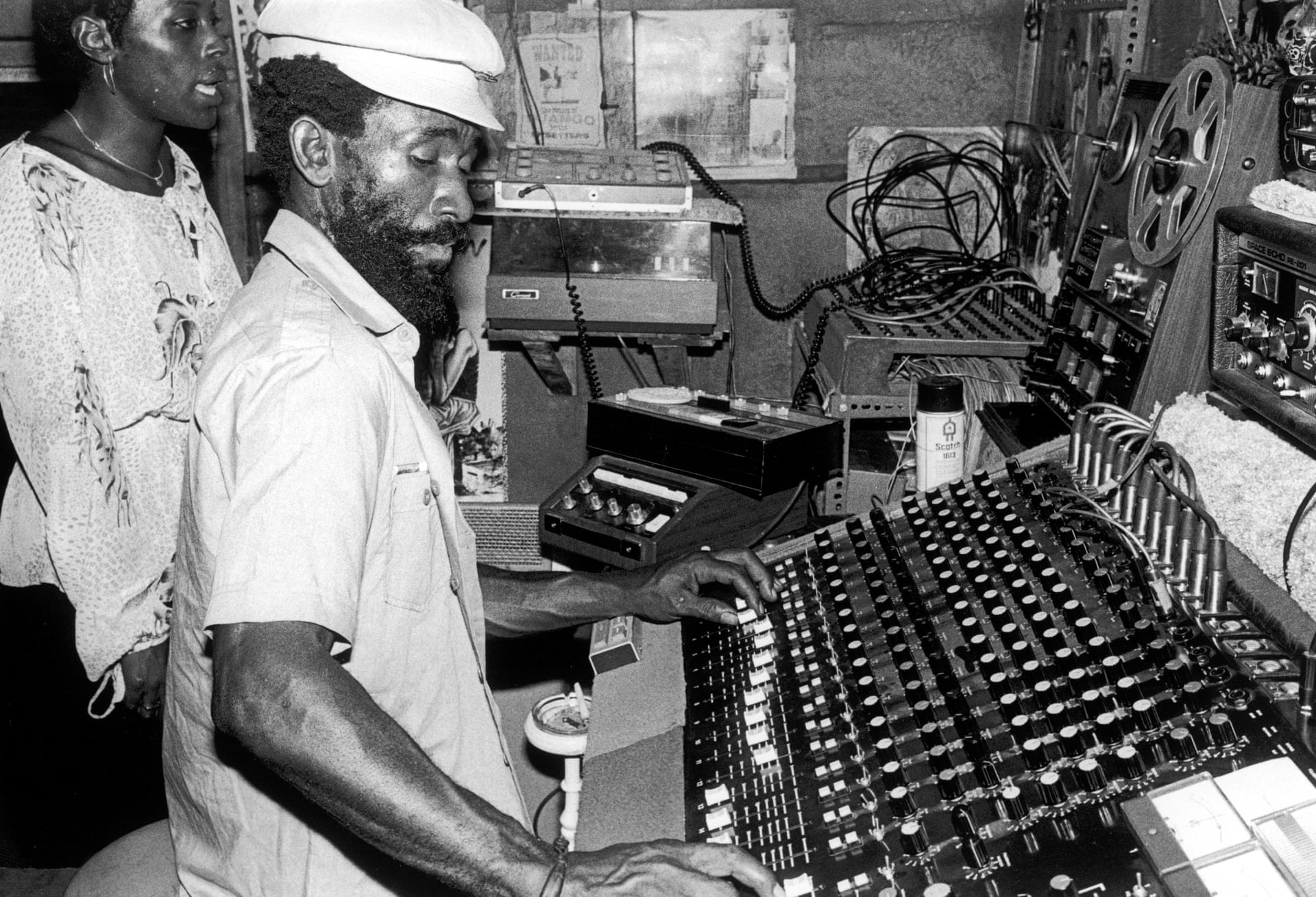

Lee "Scratch" Perry 1936- 2021

Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry

at his Black Ark studio in Kingston in the

1970s.

Photograph: Dennis Morris

Camera Press

Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry: a life in pictures

A celebration of the Jamaican producer and performer who has

died aged 85.

Perry was often hailed as a genius and was a major influence

on Bob Marley.

He also pioneered dub and roots reggae styles

G

Sun 29 Aug 2021 23.08 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/music/gallery/2021/aug/29/

lee-scratch-perry-a-life-in-pictures

Lee "Scratch" Perry 1936-2021

born Rainford Hugh Perry

Jamaican producer and performer

(...)

Perry was often hailed as a genius

and was a major influence on Bob Marley.

He also pioneered dub

and roots reggae styles

https://www.theguardian.com/music/gallery/2021/aug/29/

lee-scratch-perry-a-life-in-pictures

https://www.theguardian.com/music/

lee-scratch-perry

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Lee_"Scratch"_Perry

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2022/sep/01/

all-back-to-the-black-ark-a-lifetime-of-lee-scratch-perry-

in-pictures

https://www.npr.org/2021/09/10/

1035510633/the-magic-of-lee-scratch-perry

https://www.npr.org/2021/08/29/

1032226388/reggae-lee-scratch-perry-dies

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2021/aug/30/

lee-scratch-perry-10-of-his-greatest-recordings

https://www.theguardian.com/music/gallery/2021/aug/29/

lee-scratch-perry-a-life-in-pictures

Toots and the Maytals

Jamaica

formed in the early 1960s

Toots (Frederick Nathaniel)

Hibbert 1942-2020

https://www.theguardian.com/music/

toots-hibb

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/12/

arts/music/toots-hibbert-dead.html

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/sep/12/

toots-hibberts-pure-powerful-voice-carried-reggae-to-the-world

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/sep/12/

toots-hibbert-obituary-maytals

https://www.npr.org/2020/09/12/

912245520/toots-hibbert-

reggae-ambassador-and-leader-of-toots-and-the-maytals-

dies-at-77

Johnny Osbourne Jamaica

born Errol Osbourne

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Johnny_Osbourne

The Skatalites

Jamaica

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

The_Skatalites

Barrington Llewellyn 1947-2011

founding member of the popular

Jamaican harmony

trio the Heptones

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/30/

arts/music/barry-llewellyn-a-founder-of-the-heptones-

dies-at-63.html

Gregory Isaacs 1950-2010 USA

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Gregory_Isaacs

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/26/

arts/music/26isaacs.html

Jamaica's roots reggae sound >

Joseph Hill, singer-songwriter 1949-2006 UK

http://www.theguardian.com/news/2006/aug/24/

guardianobituaries.artsobituaries

Desmond Adolphus Dacres 1941-2006 UK

aka Desmond Dekker

singer and songwriter

http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2006/may/27/

arts.artsnews

http://www.theguardian.com/news/2006/may/27/

guardianobituaries.artsobituaries

Clement Seymour Dodd 1932-2004

UK

record producer and entrepreneur

http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/2004/may/06/

guardianobituaries.artsobituaries

https://www.economist.com/obituary/2004/05/20/

clement-sir-coxsone-dodd

Island Records

UK / USA

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Island_Records

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/30/

arts/music/barry-llewellyn-a-founder-of-the-heptones-dies-at-63.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/musicblog/2009/mar/23/

island-records-fifty-simon-reynolds

https://www.npr.org/2007/12/09/

17031857/bob-marleys-reggae-landmark

Barry Llewellyn,

a Founder of the Heptones,

Dies at 63

November 29, 2011

The New York Times

By ROB KENNER

Barry Llewellyn, a founding member of the popular Jamaican harmony trio the

Heptones, died on Nov. 23 in St. Andrew, Jamaica. He was 63 and lived in

Brooklyn.

The cause was pneumonia, said his wife, Monica.

Founded by Mr. Llewellyn and his schoolmate Earl Morgan, the Heptones rose from

singing on the streets of Trenchtown to take their place alongside the Wailers

and the Maytals as one of the island’s most important vocal groups. As Jamaican

popular music shifted from the hard-driving ska beat to a dreamier sound known

as rock steady, the Heptones were among the most consistent hit makers in

reggae, with romantic records like “Sweet Talking” and “Party Time.”

Barrington Llewellyn was born in Kingston, Jamaica, on Dec. 24, 1947, began

singing around the age of 14, and formed the Heptones with Mr. Morgan shortly

afterward. Inspired by American R&B groups like the Drifters and the

Impressions, the Heptones progressed from lighthearted love songs to weightier

themes on records like “Equal Rights” and “Sufferers Time.” During a prolific

five-year run with Clement S. Dodd’s Studio One label, they created a deep

catalog of hits that has been re-recorded over and over by successive

generations of musicians.

They went on to work with the visionary producer Lee (Scratch) Perry at the

height of his powers, and released the classic album “Night Food” on Chris

Blackwell’s Island Records label in 1976.

Although Leroy Sibbles wrote and sang lead on most of the group’s songs, he

credited Mr. Llewellyn — also known to friends and fans as Barry Heptones — for

his creative influence. “He was more than a member of the group,” Mr. Sibbles

said in a telephone interview on Sunday. “Barry had more talent than the other

guys who were singing with us. He was more musical. He added more inspiration.”

Usually responsible for singing harmonies, Mr. Llewellyn took the lead on songs

like “Nine Pounds of Steel” and “Take Me Darling” as well as the Heptones’

biggest international hit, “Book of Rules,” which he adapted from “Bag of

Tools,” a poem by R. L. Sharpe. The song was included in two movie soundtracks.

Mr. Llewellyn was not prone to boast about the song’s success. “He was a very

humble person,” Ms. Llewellyn said. “He would just do what he had to do to make

others happy.”

Though he lived in Brooklyn, he was in Jamaica working to establish a learning

center to help young people in his native Kingston. “The youth need that father

figure,” Ms. Llewellyn said. “That’s what he was really focusing on.” He also

recently recorded an album of his own music titled “On the Road Again,” which

has yet to be released.

When Mr. Sibbles left the group to pursue a solo career in 1978, Mr. Llewellyn

and Mr. Morgan recruited another lead singer, Naggo Morris, and continued to

record, but with diminished success. The original Heptones lineup reunited in

1995. Mr. Sibbles said that he and Mr. Llewellyn toured Europe together for the

past five years. “We actually did a tour about three months before his passing,”

he said. “The last date was in Germany, and he was still singing as strong as

ever. We never foresaw a problem with him.”

In addition to his wife, he is survived by several children and grandchildren,

as well as four brothers and four sisters.

Barry Llewellyn, a Founder of the Heptones,

Dies at 63,

NYT,

29.11.2011,

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/30/

arts/music/barry-llewellyn-a-founder-of-the-heptones-

dies-at-63.html

Reggae: the sound

that revolutionised Britain

Punk may have got all the headlines,

but reggae proved vital in ending the rift

between black and white teenagers

and introducing cross-pollination to the charts

Neil Spencer

The Observer

Sunday 30 January 2011

This article appeared

on p30 of the The New Review section

of the Observer

on

Sunday 30 January 2011.

It was published on guardian.co.uk at 00.05 GMT

on Sunday 30 January 2011.

It was last modified at 00.05 GMT

on Sunday 30 January 2011.

It was punk's "summer of hate", 1977, and the required pose was a sneer, a

leather jacket and something hacked about – a spiky haircut, a ripped T-shirt, a

sawn-off school tie. And, of course, no flares, the despised flag of hippiedom.

But at the cold, concrete roots of Britain a very different aesthetic was also

in the ascendant, one calling for an oversized tam, dreadlocks and a display of

"the red, gold and green", the colours of Rastafari. Flares? Fine!

The two looks represented the different worlds inhabited by young white and

black Britain, worlds which a year previously had been remote from each other

but which by the summer of 1977 were unexpectedly and often uncomfortably

rubbing shoulders. At Hackney town hall, under portraits of whiskery Victorian

aldermen, I watched the Cimarons chant down Babylon while Generation X snarled

their way through "Wild Youth". In Brixton, I gaped as the Slits, the acme of

unruliness, shared a stage with Birmingham's Steel Pulse, the most militant of

Britain's proliferating reggae bands.

More than just the "Punky Reggae Party" Bob Marley had playfully celebrated on

disc that summer, these were gigs that signalled the birth of a new Britain, one

in which the neofascist National Front was consigned to the margins and musical

cross-pollination became the norm. Rock-reggae bands such as the Police, ska

revivalists such as the Specials and home-grown reggae acts such as Janet Kay

would soon occupy the charts. Further down the line would come UB40, Culture

Club, Soul II Soul and then the current era in which, to quote Soul II Soul

singer Caron Wheeler: "You can't distinguish between colour any more – it's just

people."

These days, punk is to be found in the cultural academy, in lecture halls, art

galleries and fashion history books. By contrast, British reggae remains

half-forgotten and little praised, represented mainly by the Specials' "Ghost

Town" as the default tune for any retrospective on the bleak, Thatcherite early

80s.

By way of correcting the imbalance comes Reggae Britannia, a BBC4 documentary in

the vein of the channel's Soul Britannia and Folk Britannia, which follows

Britain's romance with Jamaican music from "My Boy Lollipop", Millie Small's

1964 hit, through to the late 80s. Its broadcast is preceded by a Barbican

concert featuring a selection of Jamaican and UK acts – Big Youth, Ali Campbell,

Carroll Thompson and Ken Boothe among others.

Those 1977 shows, organised by a nascent Rock Against Racism, meant it had taken

29 years since the arrival of the Empire Windrush for black and white Britain to

share the same stage. Preposterous though it now seems, it hadn't happened too

often before. Jazz had long provided a cross-racial haven (black bandleaders

such as Ken "Snakehips" Johnson were active as far back as the 1930s), but most

often the only place to find the two communities mixing was in a soul club or at

an Al Green or Stevie Wonder concert. As late as 1978, Joe Strummer would sing

of being the only "(White Man) in Hammersmith Palais" at a reggae extravaganza

(Joe exaggerated; there were at least six).

In reggae terms, it had taken the emergence of Bob Marley to effect the uneasy

coalition of rock fans, black youth, lofty Rastas and proto-punks that

confronted each other at his celebrated 1975 Lyceum shows. After Marley, reggae

was taken seriously as music of substance and innovation, where previously it

had been treated at best as a novelty or simply ridiculed.

The series of reggae hits that had made the UK's pop charts in the late 60s and

early 70s seemed only to harden prejudice; Tony Blackburn, in his pomp as Radio

1's premier DJ, declared them "rubbish", despite the British public regularly

sending the likes of Desmond Dekker's "Israelites" and "It Mek" into the Top 10.

Catchy numbers such as the Upsetters' "Return of Django" and Dave and Ansel

Collins's "Monkey Spanner" reflected reggae's popularity among skinheads (odd

given the skins' racist tendencies), while other hits – Bob and Marcia's "Young,

Gifted and Black" (originally a solemn Nina Simone song), Nicky Thomas's "Love

of the Common People" – had jaunty orchestral arrangements added to the Jamaican

originals ("stringsed up" was the saying) to sweeten them for export.

Though hits such as Bobby Bloom's "Montego Bay" were unashamed gimmicks, others,

like Dekker's "Israelites", reflected the Jamaican ghetto experience. A

surprising number became part of the fabric of British life, popular as run-out

theme tunes for football clubs (notably Harry J's "The Liquidator") and

advertising jingles.

Yet British reggae acts remained thin on the ground. Bands such as the Cimarons

existed principally to supply backing for visiting Jamaican stars or were

expected to provide a medley of soul hits rather than reggae. "You had to be

more of a showband," recalls Dennis Bovell, who established Matumbi early in the

70s and who would become a groundbreaking figure in British reggae. "We'd play

some rocksteady but mostly Otis Redding, James Brown and the like – soul music

was considered the music of emancipation."

Matumbi found work at a variety of venues – American air force bases,

chicken-in-a-basket supper clubs in places such as Huddersfield and Cannock –

though black Britain, like Jamaica, preferred to keep up to speed with the

latest releases via the "sound system" (disco) and the "blues dance" (a house

party with pay bar). "A blues was the only place you could get a girl," says

Bovell. "Reggae dancing was full embrace, and if you were young and living at

home, that was your only chance to spend a night in someone's arms."

Sound systems had long played a pivotal role in Jamaican life, providing escape

and a showcase for hot tunes, usually with added commentary from talk-over DJs

such as Dennis Alcapone and Big Youth. "Sound systems were our BBC or CNN, a way

to communicate with people on the street," says Big Youth in Reggae Britannia.

In Britain, sound systems were almost the only conduit for reggae. "There was

nothing on the radio," points out Bovell, who alternated his role in Matumbi

with running London's Jah Sufferer system.

British sound systems, which drew cachet from having the latest Jamaican

releases, were snooty about home-grown product. Bovell, exasperated at the

exclusion of his music, eventually bought a "dinking" machine to knock out the

centre of his records so he could pass them off as Jamaican imports.

For the sons and daughters of the Windrush generation, reggae became an

underground code of defiance, part of the quest for selfhood. "We rejected the

caution and restraint our parents had in a hostile racial environment," says

poet Linton Kwesi Johnson. "We were the rebel generation – reggae afforded us

our own identity."

Singer Brinsley Forde, who helped found Aswad in 1975, echoes the sentiment.

"What we sang about was our experience in London. People were copying Jamaica

but weren't telling their own story."

A key element of that story was police use of the hated "sus" laws, which

allowed people to be picked up on "suspicion" of committing a crime, while

hostility to the police was stoked by the deployment of phalanxes of cops to

protect National Front marches through black areas.

A simmering atmosphere of distrust was brought to boiling point at the end of

1976's long hot summer, when the Notting Hill carnival turned into a battle

between black youth and police. The confrontation would be played out in more

extreme form in 1980 and 1981, as Brixton, Southall, Liverpool, Birmingham,

Bristol and Leeds all experienced incendiary riots, one result of which was the

repeal of the sus laws.

The summer of 1976 brought another pivotal event, Eric Clapton's drunken rant on

stage at Birmingham, in which he acclaimed Enoch Powell as the politician who

would "stop Britain from becoming a black colony… the black wogs and coons and

fucking Jamaicans don't belong here". From a man which had topped the US charts

with a cover of Marley's "I Shot the Sheriff", this was shocking stuff and

inspired the formation of Rock Against Racism (RAR).

British reggae swiftly acquired a new militancy and ubiquity. Steel Pulse sang

"Ku Klux Klan" with the Klan's white hoods on their heads. Linton Kwesi Johnson

proclaimed it was "Dread Inna Inglan" and warned "get ready for war". The

growing roster of home-grown acts – Misty in Roots, Reggae Regular, Black Slate

– found exposure on RAR stages and, after John Peel's conversion from prog rock,

on his Radio 1 show and its live sessions.

Aside from its social commentary, reggae became chic due to its sonic

radicalism, with its dub, rap and special disco mixes picked up by rock and

soul. "Reggae taught us about space, leaving gaps. It was such a relief after

the strictness and minimalism of punk," says Viv Albertine, guitarist with the

Slits, whose 1979 album, Cut, was produced by Dennis Bovell.

In the post-punk era, the Clash, the Members and the Ruts were other rock bands

incorporating reggae into their sound, along with the Police, who deftly

integrated reggae on hits 'Message in a Bottle" and "Walking on the Moon". "We

plundered reggae mercilessly," acknowledges drummer Stewart Copeland on Reggae

Britannia.

By the close of the decade, another strand of Brit reggae was in play; the 2

Tone ska revivalism of Coventry's Specials. Their nostalgia for the ska of the

mod and skinhead era quickly blossomed into a ska-punk fusion. As Specials

founder Jerry Dammers remarks: "We were the beginning of the imitation

generation. We didn't know how to play Jamaican ska so we ended up creating

something that never happened in the first place."

Together with the Selecter, the Beat, Madness and more, the 2 Tone bands

straddled the fault lines of British racism, their multiracial line-ups

attracting an audience that included sieg heiling skinheads intent on trashing

their shows. It was a crazy, unsustainable scenario that helped capsize the

Specials, though their swan song, "Ghost Town", became the defining hit of 1981.

The angst and confrontation of British reggae ebbed during the 80s – "The fun

had gone out of the music," says Bovell – though by then it had melded into

mainstream pop. Janet Kay's "Silly Games" reached No 2, a representative of

sweet, home-grown lovers rock that found an echo in the catchy output of Culture

Club with what singer Boy George describes as "reggae that wouldn't frighten

white people". Some said the same of Birmingham's UB40 – "They cashed in on our

hard work with a weaker, pastel version," opines Steel Pulse's Mykaell Riley –

though the Brum troupe would prove world conquerors, popular even in Jamaica.

A few years later, the arrival of Soul II Soul and Massive Attack, collectives

weaned on sound systems and punky reggae, rendered the old categories obsolete.

Was their music reggae, funk, hip-hop, pop or something else? It was all and

none of those things, but mostly it was just British.

The Reggae Britannia concert is at the Barbican,

London on 5 February. Members

of the Guardian

and Observer's Extra scheme can save

£5 off top-price stall

seats. www.guardian.co.uk/extra.

Reggae Britannia, the documentary,

will be broadcast on BBC4 at 9pm on 11

February,

followed by film of the Barbican concert

Reggae: the sound that

revolutionised Britain,

O,

30.1.2011,

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2011/jan/30/

reggae-revolutionary-bob-marley-britain

Alton

Ellis,

Jamaican Singer,

Dies at 70

October 17,

2008

The New York Times

By ROB KENNER

Alton

Ellis, the smooth Jamaican singer and songwriter known as the Godfather of Rock

Steady, died early Saturday morning (local time) in London. He was 70 and had

lived in Middlesex, England, for nearly two decades.

The cause was multiple myeloma, a form of bone cancer, said his business

manager, Trish De Rosa.

Starting in the 1950s, Mr. Ellis helped lay the foundations of the Jamaican

recording industry, singing songs that would profoundly influence global pop

music.

“Alton was a bigger artist in Jamaica than Bob Marley,” said Dennis Alcapone,

another Jamaican recording artist working in Britain who often performed with

Mr. Ellis. “Everybody, even Bob, would love if he could sing like Alton Ellis.

All of them would sit back and listen to Alton because Alton was the king.”

Alton Ellis was born and raised in Trenchtown, the same underprivileged Kingston

neighborhood that was home to stars like Marley. Mr. Ellis and his younger

sister Hortense got their start as schoolchildren competing on Kingston talent

shows like “Vere John’s Opportunity Hour.” In 1959, as half of the duo Alton &

Eddie, he recorded the R&B-style scorcher “Muriel,” which became one of the

first hit records for the pioneering local producer Clement Dodd, known as

Coxsone.

Bouncing between Mr. Dodd’s Studio One label and the Treasure Isle label of a

rival producer, Arthur Reid, known as Duke, Mr. Ellis blazed a trail with a

series of classic love songs like “Girl I’ve Got A Date,” “I’m Just a Guy” and

his signature, “Get Ready Rock Steady,” a 1966 dance-craze record that inspired

a new era in Jamaican music. (Much later he established his own label,

All-Tone.)

Rock steady was a sweeter, slower sound that formed the bridge between the

hard-driving brass of ska and the rebel reggae that Marley later spread

throughout the world. Rock steady’s easy pace and spare arrangements were the

perfect showcase for Mr. Ellis’s soulful tenor, an elegant instrument that fell

somewhere between the roughness of Otis Redding and the silkiness of Sam Cooke.

“Alton ruled the rock steady era,” Mr. Alcapone said. But Mr. Ellis’s influence

did not stop there.

“Get Ready Rock Steady” was used in 1969 on “Wake the Town,” featuring a

Rastafarian D.J. named U-Roy; the track would be described by some as the

world’s earliest rap recording. The instrumental track to Mr. Ellis’s

composition “Mad Mad” became one of the most covered recordings in reggae

history, influencing generations of dancehall and hip-hop artists. And his 1967

composition “I’m Still in Love With You” was covered several times, most

recently by the dancehall artists Sean Paul and Sasha, reaching No. 3 on

Billboard’s Hot Singles chart in 2004.

Mr. Ellis was awarded Jamaica’s Order of Distinction in 1994 and was inducted

into the International Reggae and World Music Hall of Fame in 2006.

Ms. De Rosa said his body would lie in state in the National Arena in Jamaica to

accommodate the crowds expected to pay their respects to Mr. Ellis, who never

stopped working until he collapsed after a London performance in August. He had

juggled demands to perform and record even as he underwent chemotherapy, making

a final trip to Jamaica in June.

“My dad did a lot for music, but he didn’t really boast about it like he could

have,” said his 23-year-old son Christopher, who often performed with his father

and was one of his more than 20 children. “He’s got a lot of respect, and his

name is really big, but financially he’s been robbed over the years. He told me,

‘Son, do not let them rob you like they robbed me.’ ”

After a long battle for royalties, Mr. Ellis received a check for “I’m Still in

Love With You” a few weeks before he died, Ms. De Rosa said.

Alton Ellis, Jamaican Singer, Dies at 70,

NYT,

17.10.2008,

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/17/

arts/music/17ellis.html

Desmond Dekker, 64,

Pioneer of Jamaican

Music,

Dies

May 27, 2006

The New York Times

By JON PARELES

Desmond Dekker, the Jamaican singer whose 1969

hit, "The Israelites," opened up a worldwide audience for reggae, died on

Wednesday. He was 64.

He died after collapsing from a heart attack at his home in Surrey, England, his

manager, Delroy Williams, told Reuters.

"The Israelites" was the peak of Mr. Dekker's extensive career, selling more

than a million copies worldwide. He was already a major star in Jamaica and well

known in Britain. The song was his only United States hit, but it was a turning

point for Jamaican music among international listeners.

The Jamaican rhythm of ska had already generated hits in the United States,

notably Millie Small's 1964 hit, "My Boy Lollipop." But that song was treated as

a novelty. "The Israelites," with its biblical imagery of suffering and

redemption, showed the world reggae's combination of danceable rhythm and

serious, sometimes spiritual intentions.

Mr. Dekker was named Desmond Adolphus Dacres when he was born in Kingston,

Jamaica, in 1941. As a teenager he worked in a welding shop alongside Bob Marley

and auditioned unsuccessfully for various producers until Mr. Marley encouraged

him to try out for his own first producer, Leslie Kong.

Mr. Kong produced Mr. Dekker's first single, "Honour Thy Father and Mother," in

1963, and it reached No. 1 in Jamaica. Like many of Mr. Dekker's songs, it

carried a message. A string of Jamaican hits followed, including "It Pays,"

"Sinners Come Home" and "Labour for Learning." Mr. Dekker had a total of 20 No.

1 hits in Jamaica.

A series of songs including "Rude Boy Train" and "Rudie Got Soul" made Mr.

Dekker a hero of Jamaica's rough urban "rude boy" culture.

His 1960's songs used the upbeat ska rhythm, a precursor to reggae also known as

bluebeat. By the end of the decade, Mr. Dekker had won the Golden Trophy award,

presented annually to Jamaica's top singer, five times and was known as the King

of Bluebeat. He won the Jamaican Song Festival in 1968 with "Intensified."

"Honour Thy Father and Mother" was released in Britain in 1964 on Chris

Blackwell's Island label, which would later release Bob Marley's albums. Three

years later, Mr. Dekker had his first British Top 20 hit with "007 (Shanty

Town)," a tale of rude-boy ghetto violence — "Dem a loot, dem a shoot, dem a

wail" — sung in a thick patois, which Americans would hear later as part of the

soundtrack to the film "The Harder They Come" in 1972. Paul McCartney slipped

Mr. Dekker's first name into the lyrics to the Beatles' ska song, "Ob-La-Di,

Ob-La-Da," on "The Beatles" (also known as the White Album) in 1968, the year

Mr. Dekker moved to England.

With "The Israelites," released in Jamaica in December 1968, Mr. Dekker had an

international impact. "I was telling people not to give up as things will get

better," he said in a interview last year for the Set the Tone 67 Web site.

"The Israelites" reached No. 1 in Britain and No. 9 in the United States in

1969. The song would return to the British charts in 1975 and was reissued as a

single after being used in a commercial for Maxell recording tape in 1990.

Although Mr. Dekker had no further hits in the United States, he continued to

have hits in England with "It Mek" in 1969 and the first recording of Jimmy

Cliff's "You Can Get It if You Really Want" in 1970. But while Mr. Dekker kept

up a busy performing career, the death of Mr. Kong in 1971 ended his streak of

hits. He returned to the British charts with "Sing a Little Song" in 1975.

The punk era of the late 1970's brought with it an English revival of ska by

groups like Madness and the Specials. Mr. Dekker's songs were rediscovered, and

he was signed by Madness's label, Stiff Records. His 1980 album, "Black and

Dekker," featured members of a venerable Jamaican band, the Pioneers, and Graham

Parker's band, the Rumour. The British hitmaker Robert Palmer produced Mr.

Dekker's next album, "Compass Point," in 1981. But in 1984 Mr. Dekker declared

bankruptcy, blaming his former manager.

In 1993, the Specials reunited and backed up Mr. Dekker on the album "King of

Kings," with remakes of ska hits. In 2000 he released the album "Halfway to

Paradise." He continued to tour regularly; his final concert was on May 11 at

Leeds University.

Mr. Dekker was divorced and is survived by a son and daughter.

Desmond Dekker, 64, Pioneer of Jamaican Music, Dies,

NYT,

27.5.2006,

https://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/27/

arts/music/27dekker.html

Related > Anglonautes >

Arts >

Music >

Reggae

Bob

Marley 1945-1981

Related > Anglonautes >

Vocapedia >

Arts >

Music

genre >

ska, rocksteady, reggae >

Jamaica, UK

|