|

History

> USA >

Journalism > Watergate 1972-1974

Reporters

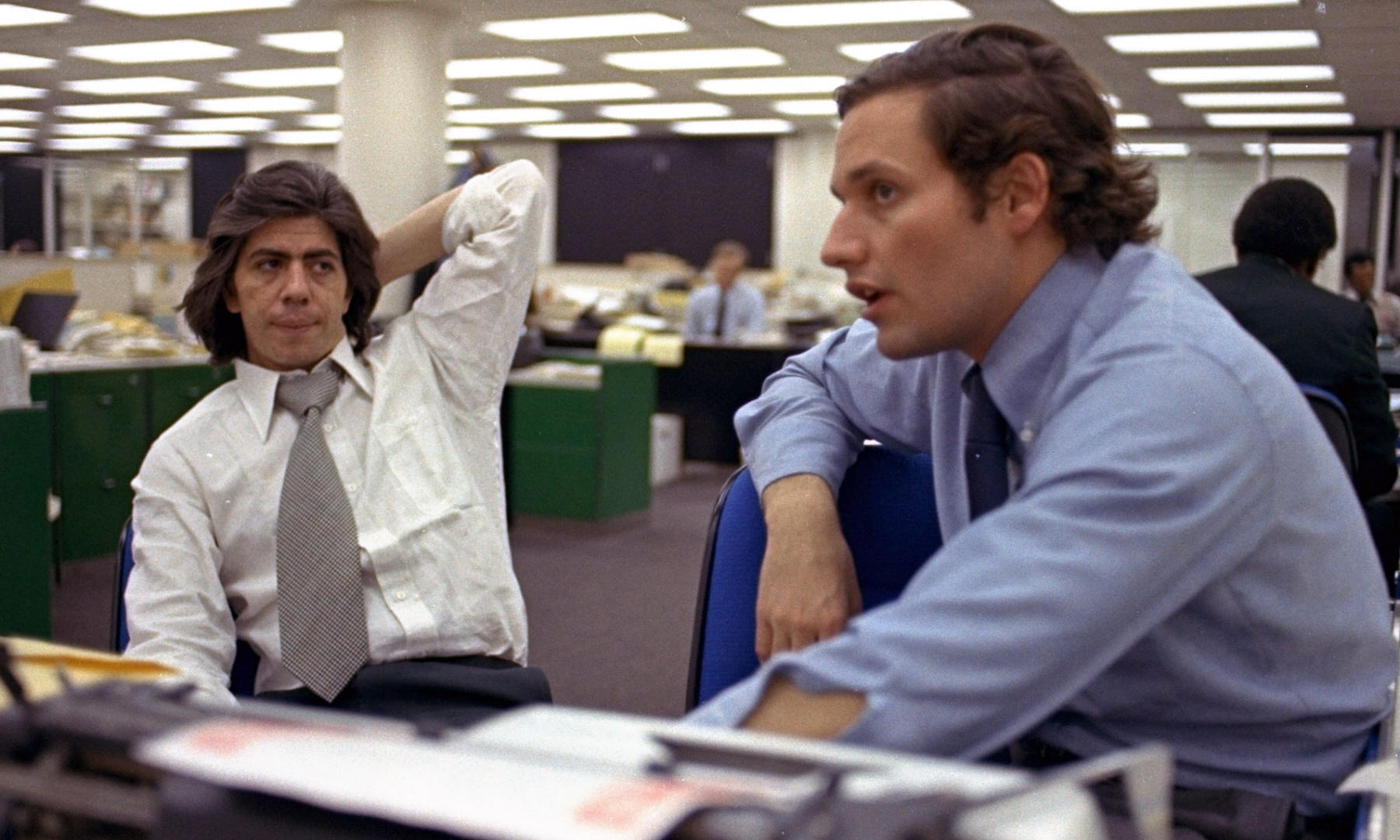

Bob Woodward, right,

and

Carl

Bernstein,

whose reporting of the Watergate case won

them a Pulitzer Prize,

in the

Washington Post newsroom in

1973.

Photograph: AP

Woodward and Bernstein:

Watergate echoes loud in Donald Trump era

Veteran journalists may have thought their

biggest story was behind them,

then Trump came along.

‘This is worse than Watergate’, says

Bernstein

G

Sun 12 Aug 2018 15.29 BST

Last modified on Sun 12 Aug 2018 15.40 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/aug/12/

woodward-bernstein-watergate-donald-trump-era

John Dean III

https://www.npr.org/2019/06/10/

731119019/key-nixon-accuser-returns-to-capitol-

with-sights-set-on-another-president

George Gordon Battle Liddy

1930-2021

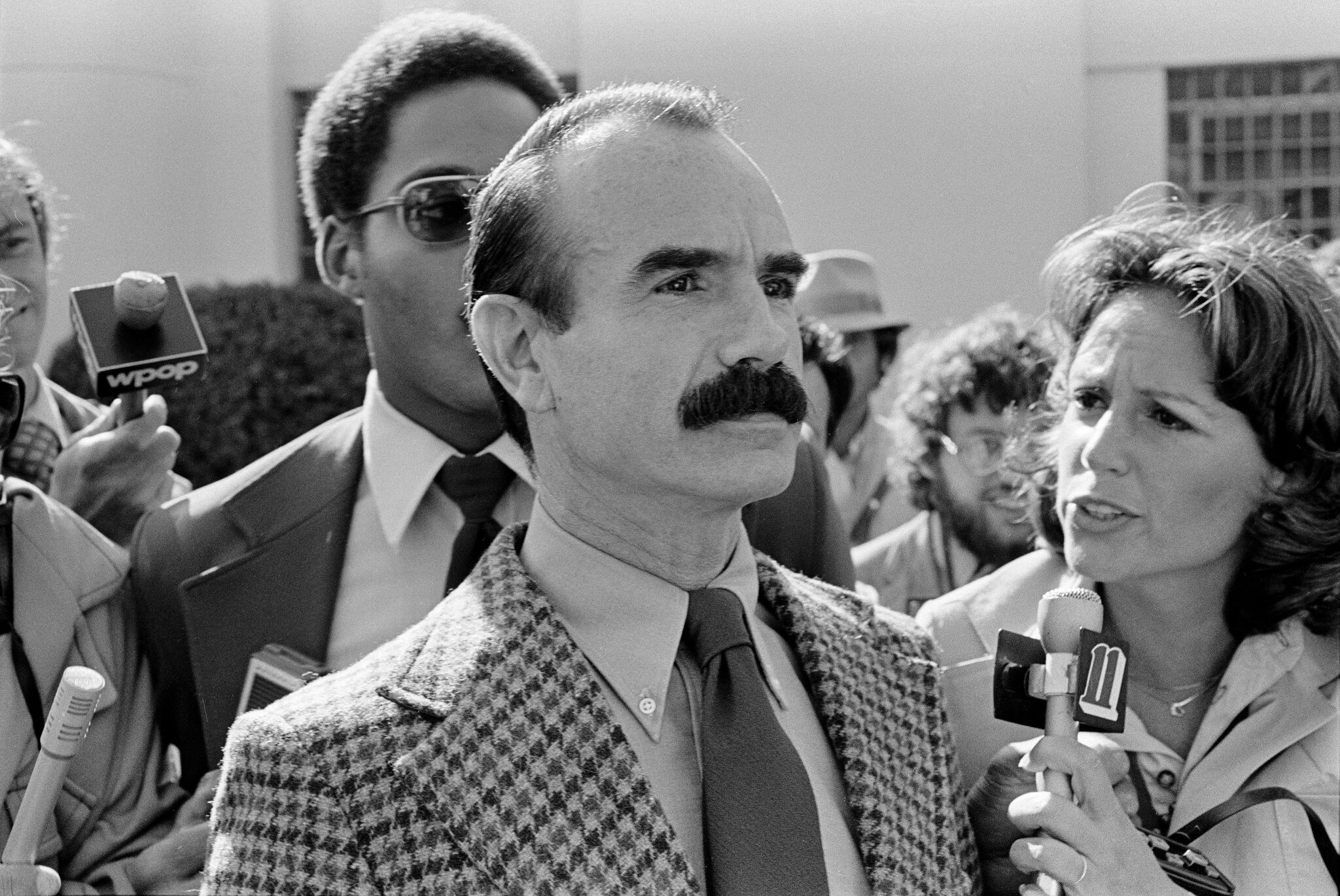

G. Gordon Liddy after his release from

prison

in Danbury, Conn., on Sept. 7, 1977.

Photograph:

Fred R. Conrad

The New York Times

G. Gordon Liddy, Mastermind Behind Watergate

Burglary, Dies at 90

Unlike other defendants in the scandal that

brought down Richard Nixon,

Mr. Liddy refused to testify and drew the

longest prison term.

NYT

March 30, 2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/30/

us/g-gordon-liddy-dead.html

mastermind behind Watergate

burglary

Unlike other defendants in the scandal

that brought

down Richard Nixon,

Mr. Liddy refused to testify

and drew the longest prison

term.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/30/

us/g-gordon-liddy-dead.html

https://www.npr.org/2021/03/31/

982920228/g-gordon-liddy-chief-operative-behind-watergate-scandal-

dies-at-90

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/30/

us/g-gordon-liddy-dead.html

Earl Judah Silbert

1936-2022

lead prosecutor of Watergate

break-In

He worked to secure several

convictions,

making early inroads

in the

investigation of a scandal

that would

bring down a president.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/15/

us/politics/earl-j-silbert-dead.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/15/

us/politics/earl-j-silbert-dead.html

Cornelius Mahoney Sheehan

1936-2021

Times reporter

obtained the

Pentagon Papers

His exhaustive coverage of the

Vietnam War

also led to the book “A Bright

Shining Lie,”

which won a National Book Award

and a Pulitzer Prize.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/07/

business/media/neil-sheehan-dead.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/07/

business/media/neil-sheehan-dead.html

Thomas Fisher Railsback 1932-2020

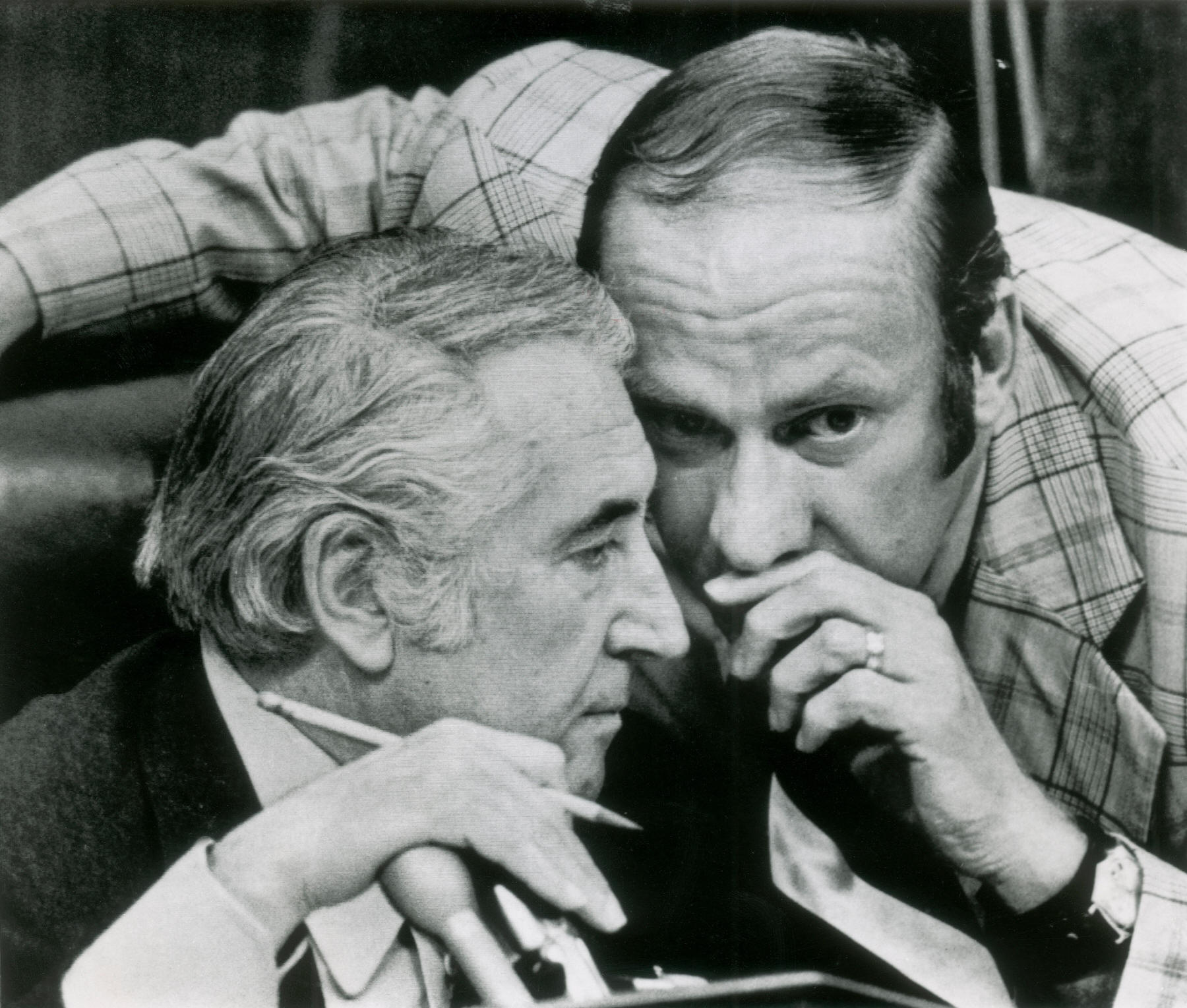

Representative Tom Railsback, right,

Republican of Illinois,

conferred with Peter Rodino,

the chairman of the House Judiciary

Committee,

during a debate on the articles of

impeachment

against President Richard M. Nixon in July

1974.

Photograph: Associated Press

Tom Railsback, Who Reconciled G.O.P. to Oust

Nixon, Dies at 87

A moderate Republican congressman from

Illinois,

he forged a compromise on two articles of

impeachment

that passed the House Judiciary Committee in

1974.

NYT

Jan. 22, 2020

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/22/

us/politics/tom-railsback-dead.html

Tom Railsback,

(was) an eight-term Illinois congressman

who forged what he called

a “fragile bipartisan

coalition”

between his fellow

Republicans

and the Democratic majority

on the House Judiciary Committee in 1974

to draft articles of

impeachment

against President Richard M.

Nixon

(...)

On July 27, 1974,

the judiciary committee voted 27 to 11,

with 6 of the panel’s 17 Republicans

joining all 21 Democrats,

to send to the full House

an article of impeachment.

The article accused the president

of unlawful tactics that constituted

a “course of conduct or

plan”

to obstruct the investigation

of the break-in at the offices

of the Democratic opposition

in the Watergate complex

in Washington by a White House

team of burglars.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/22/

us/politics/tom-railsback-dead.html

https://www.npr.org/2020/01/25/

799428031/remembering-a-congressman-

who-bucked-his-party-on-an-impeachment

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/22/

us/politics/tom-railsback-dead.html

Egil Krogh Jr. 1939-2020

Mr. Krogh

and his wife at the time, Suzanne

Krogh,

arrived at the United States marshal’s

office

in Washington in January 1974

to begin his prison sentence for his role

in

the burglary of a psychiatrist’s office.

He resigned from that post later that year

as a criminal case against him was building.

Photograph: Associated Press

Egil Krogh, Who Authorized an Infamous

Break-In, Dies at 80

He regretted his role in the burglar

of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s

office

and said he thought it had set the stage for

Watergate.

NYT

Jan. 21, 2020

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/21/

us/politics/egil-krogh-dead.html

Egil Krogh appeared before the Senate

Commerce Committee

after being nominated for under secretary of

transportation

in January 1973.

He resigned from that post later that year

as a criminal case against him was building.

Photograph: Associated Press

Egil Krogh, Who Authorized an Infamous

Break-In, Dies at 80

He regretted his role in the burglar

of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s

office

and said he thought it had set the stage for

Watergate.

NYT

Jan. 21, 2020

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/21/

us/politics/egil-krogh-dead.html

Egil Krogh,

(...)

as part of President Richard M. Nixon’s staff

was one of the leaders of the secret “Plumbers”

unit

that broke into the office

of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist,

a prelude to the Watergate

burglary

that brought down the Nixon presidency

(...)

In November 1973,

Mr. Krogh, known as Bud, pleaded guilty

to “conspiracy against rights of citizens”

for his role in the September 1971

break-in at the office of Dr. Lewis Fielding

in Beverly Hills, Calif.

The Plumbers, a group of White House

operatives,

were tasked with plugging

leaks

of confidential material,

which had bedeviled the Nixon administration.

Mr. Ellsberg, a military analyst,

had been responsible for the biggest leak of all:

passing the Pentagon Papers,

the top-secret government

history of the Vietnam War,

to The New York Times earlier that year.

The Plumbers were hoping to get information

about Mr. Ellsberg’s mental

state

that would discredit him,

but they found nothing of importance

related to him.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/21/

us/politics/egil-krogh-dead.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/21/

us/politics/egil-krogh-dead.html

James Walter McCord Jr. 1924-2019

James W. McCord Jr.,

who led the burglars in the Watergate

scandal,

testifying in 1973 at Senate hearings

about the break-in at Democratic National Committee

headquarters.

Photograph:

Mike Lien

The New York Times

James W. McCord Jr., Who Led the Watergate

Break-In, Is Dead at 93

NYT

April 18, 2019

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/18/

obituaries/james-mccord-watergate-dead.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/18/

obituaries/james-mccord-watergate-dead.html

Richard Nixon waves goodbye from the steps of his helicopter

outside the White House,

after he gave a farewell address to members of the White House staff,

in August 1974.

Photograph: Chick Harrity

AP

Why won't Nixon loyalists talk about Trump's

impeachment inquiry?

The Guardian

Thu 10 Oct 2019 06.00 BST

Last modified on Thu 10 Oct 2019

15.17 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/oct/10/

richard-nixon-impeachment-donald-trump-republican-president

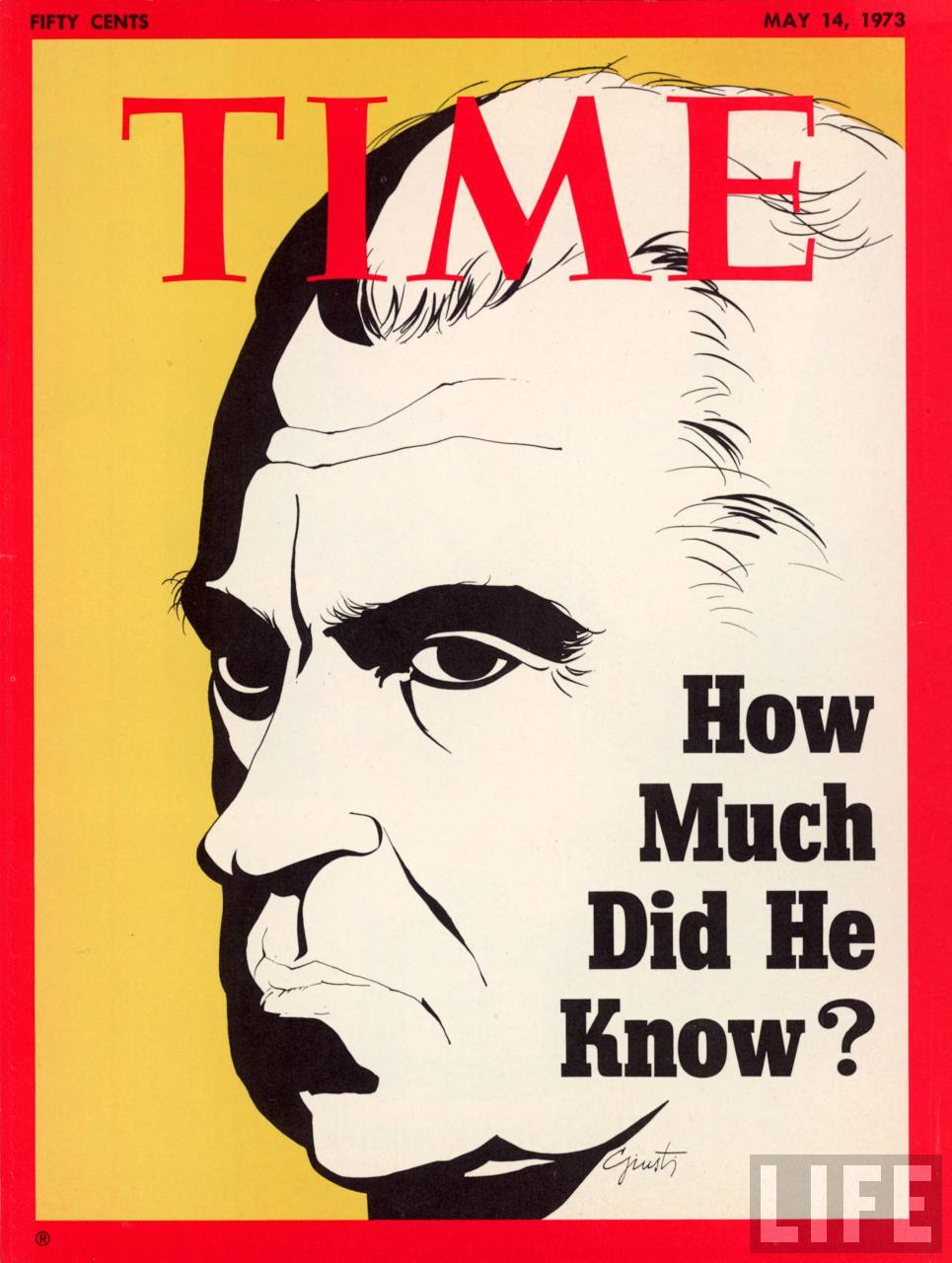

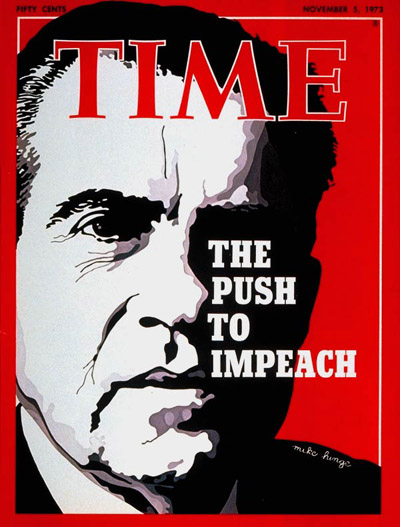

Time Covers - The 70S

TIME cover 05-14-1973 ill. of Richard Nixon

[1913-1994].

Date taken: May 14, 1973

Illustration: George Giusti

Life

Related

https://www.nytimes.com/topic/person/richard-milhous-nixon

Nov. 5, 1973

http://www.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,1101731105,00.html- broken link

Herbert Warren Kalmbach 1921-2017

Richard M. Nixon’s personal lawyer

and a conduit for hush money

from the 1972 presidential campaign

to the Watergate burglars

(...)

Mr. Kalmbach was briefly imprisoned

and temporarily lost his law license

for illegally raising vast bundles of cash,

much of it furtively exacted

from corporations and individuals.

He oversaw a secret $500,000 stash

to finance sabotage and spy operations

against the Democrats run

by the Nixon political operative

Donald H.

Segretti.

He funneled $220,000

to pay off the seven defendants

who had bungled the break-in

of the Democratic National

Committee

headquarters

at the Watergate complex.

And he steered $100,000

to an unsuccessful campaign to defeat

George C. Wallace’s comeback

as governor of Alabama in 1970.

Mr. Kalmbach also conveyed

to the Nixon re-election war chest

$2 million from the milk industry,

which was promised federal subsidies.

The money,

from a dairy cooperative organization,

came disguised illegally

as small

contributions.

In another episode,

after withdrawing $100,000 earmarked

for the anti-Wallace effort

from a safe

deposit box,

he hand-delivered the cash

to a stranger in the lobby

of the Sherry-Netherland Hotel

in

New York, identifying himself

as “Mr. Jensen of

Detroit.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/29/

obituaries/herbert-kalmbach-who-figured-in-watergate-payoffs-dies-at-95.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/29/

obituaries/herbert-kalmbach-who-figured-in-watergate-payoffs-dies-at-95.html

Charles Norman Shaffer Jr. 1932-2015

fastidious litigator

whose painstaking defense of

John W. Dean III,

the White House counsel,

helped cost Richard M. Nixon

the presidency

during the Watergate scandal

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/20/us/

charles-n-shaffer-jr-lawyer-who-bolstered-case-against-nixon-dies-at-82.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/20/us/

charles-n-shaffer-jr-lawyer-who-bolstered-case-against-nixon-dies-at-82.html

Robert Erwin Herzstein 1931-2015

Robert E. Herzstein

(...)

successfully sued

on behalf of

historians and journalists

to

prevent former

President Richard M. Nixon

from removing

and even destroying

his White House

papers and tapes

after his resignation

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/18/us/

politics/robert-e-herzstein-who-foiled-nixon-dies-at-83.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/18/us/

politics/robert-e-herzstein-who-foiled-nixon-dies-at-83.html

Benjamin Crowninshield Bradlee 1921-2014

Ben Bradlee

(...)

presided

over The Washington Post’s

Watergate reporting

that led to the fall

of President Richard M. Nixon

and that stamped him

in American culture

as

the quintessential newspaper editor of his era

—

gruff, charming and tenacious —

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/22/

business/media/ben-bradlee-editor-who-directed-watergate-coverage-dies-at-93.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/22/

business/media/ben-bradlee-editor-who-directed-watergate-coverage-dies-at-93.html

Eugene Corbett Patterson 1923-2013

Pulitzer Prize-winning

editor

of The Atlanta Constitution

during the civil rights conflicts of the 1960s

and later the managing

editor

of The Washington Post

and editor

of The St.

Petersburg Times in Florida

(...)

Mr. Patterson joined

The

Washington Post in 1968

as managing editor,

succeeding Benjamin C.

Bradlee,

who became executive editor.

The two led the newsroom in

June 1971

when The Post followed The

New York Times

in publishing the Pentagon Papers,

the secret study of American

duplicity in Indochina.

Nixon administration challenges

to both publications were struck down

in a

historic Supreme Court ruling.

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/14/us/eugene-c-patterson-editor-and-civil-rights-crusader-dies-at-89.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/14/us/

eugene-c-patterson-editor-and-civil-rights-crusader-dies-at-89.html

https://www.nytimes.com/books/97/04/13/

reviews/papers-final.html

Mark Felt

1913–2008

pseudonym "Deep Throat"

former FBI official

who will be remembered by

history

as the anonymous source Deep

Throat

(...)

Felt gave crucial tips

to Washington Post reporters

Bob Woodward and Carl

Bernstein

during the Watergate

scandal,

which helped topple

President Richard Nixon.

After denying he was Deep

Throat for 33 years,

Felt came clean in 2005.

https://www.npr.org/2008/12/19/

98529519/woodward-deep-throat-a-man-of-courage

https://www.npr.org/series/4675817/

clearing-up-the-deep-throat-mystery

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Deep_Throat_(Watergate)

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/11/29/

us/politics/j-stanley-pottinger-dead.html

https://www.npr.org/sections/publiceditor/2008/12/19/

98529841/deep-throats-legacy-to-journalism

https://www.npr.org/2008/12/19/

98529519/woodward-deep-throat-a-man-of-courage

https://www.nytimes.com/2005/06/01/

politics/deep-throat-unmasks-himself-as-exno-2-official-at-fbi.html

Watergate

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/11/29/

us/politics/j-stanley-pottinger-dead.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/15/

us/politics/earl-j-silbert-dead.html

https://www.npr.org/2022/06/16/

1105158079/in-new-edition-of-classic-watergate-expose-woodward-and-bernstein-link-nixon-tru

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/15/

books/review/watergate-garrett-m-graff.html

Corpus of news

articles

What to

Remember About Watergate

MAY 20, 2017

By SCOTT

ARMSTRONG

SundayReview

Op-Ed

Contributor

Echoes of

Watergate are everywhere these days.

President Trump’s firing of the F.B.I. director, James Comey, drew immediate

comparisons to Richard Nixon’s order to dismiss the special Watergate

prosecutor, Archibald Cox, in October 1973. Mr. Trump’s insinuation that he had

taped meetings with Mr. Comey recalled the secret White House recordings that

ultimately brought a president down. And the demands today for aggressive

congressional investigations into possible collusion between the Trump campaign

and Russia during the 2016 election remind me of the pressures on House and

Senate investigations into the 1972 Nixon presidential campaign.

As a 27-year-old investigator for the Senate’s Watergate committee, I saw up

close how that inquiry unfolded. Our committee helped unearth the most damning

evidence against the president. But the special prosecutor’s office played a

crucial role in making that evidence public. The two entities overcame partisan

and jurisdictional conflicts to bring about the president’s resignation — and

their work offers a valuable lesson for today, when hyper-partisanship

dominates.

The Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities was created in February

1973 after John Sirica, the Republican federal judge presiding over the trial of

men charged with breaking into Democratic Party offices at the Watergate, raised

doubts about whether they had acted alone, skepticism spurred by articles in The

Washington Post. Judge Sirica’s harsh sentences broke the burglars’ silence.

Led by its Democratic chairman, Sam J. Ervin Jr. of North Carolina, and its

Republican vice chairman, Howard H. Baker Jr. of Tennessee, the committee tried

to present a bipartisan image. Behind closed doors it was anything but. Our star

witness, John Dean, the former White House counsel, warned the Democratic staff

privately that while he oversaw the White House cover-up for Mr. Nixon, Mr.

Baker and the minority counsel, Fred Thompson, were trying to thwart the

congressional investigation.

Before the hearings began, the Democratic staff decided not to share details

about Mr. Dean’s damaging evidence with Republican colleagues. At a contentious

executive session, Mr. Baker opposed plans by the committee’s chief counsel,

Samuel Dash, to use the hearings to explain political and criminal events

preceding the break-in. On Mr. Dash’s orders, I followed Mr. Baker’s top aide

and discovered he was meeting secretly with the White House counsel, J. Fred

Buzhardt. We confronted Mr. Baker, and the aide resigned.

When the televised hearings opened in May 1973, Mr. Baker and Mr. Thompson

continued to work behind the scenes to prevent the inquiry from focusing on Mr.

Nixon. In July, a committee stenographer slipped me a copy of notes from secret

conversations in which Mr. Buzhardt provided Mr. Thompson lengthy quotations

from Mr. Nixon’s one-on-one meetings with Mr. Dean. Mr. Baker and Mr. Thompson

tried to use that information to suggest during cross-examination that Mr. Dean

was the sole author of the cover-up.

On July 13, we questioned a Nixon aide, Alexander Butterfield, about Mr.

Thompson’s notes. Pressed to explain how he had obtained such precise quotations

from the Nixon-Dean meetings, Mr. Butterfield revealed that the president had a

taping system in his offices.

Once Mr. Baker’s collusion with the White House was revealed in Mr. Thompson’s

memo, I could see his opposition to obtaining the tapes melt, and the committee

voted unanimously to subpoena them. But the White House refused to turn them

over, and the courts decided not to intervene in a confrontation between two

branches of government.

Partisan politics continued in private. Mr. Baker and Mr. Thompson promoted a

bogus explanation for the break-in, alleging that the C.I.A. had initially

assisted and then undermined the Watergate burglars in order to damage the

president.

Meanwhile, the Democratic staff unearthed the actual motive for the break-in:

Mr. Nixon and his campaign manager, John Mitchell, were worried that Charles

Rebozo, known as Bebe, would be identified as the man who had accepted $100,000

in cash for Mr. Nixon from the billionaire Howard Hughes. Mr. Mitchell had

authorized breaking into the Watergate office of Larry O’Brien, chairman of the

Democratic National Committee — who had been a paid consultant to Mr. Hughes —

to see what Mr. O’Brien knew about the Rebozo transaction.

We also discovered a $100,000 payment from Mr. Hughes to Hubert Humphrey, the

Democratic presidential candidate. Mr. Ervin shut down the hearings. “I was just

preserving the two-party system,” he said jokingly to me afterward.

Yet for all its infighting, the committee played a crucial role in unearthing

information that led to Mr. Nixon’s downfall. After our subpoena for the White

House tapes was blocked in federal court, the special prosecutor issued his own.

Mr. Nixon responded by having Mr. Cox fired, which led to the resignation of

Attorney General Elliot L. Richardson and the deputy attorney general, William

D. Ruckelshaus. Mr. Cox had opposed a deal under which a conservative Democratic

senator, John Stennis, would review and verify summaries of the tapes. Under

that deal, prosecutors, courts and the public would not have gained access to

them.

The move backfired spectacularly. Public outrage over the Saturday Night

Massacre, as it became known, encouraged lawyers in the special prosecutor’s

office to aggressively pursue the tapes. Their arguments convinced the Supreme

Court that in a criminal case, every citizen — even a president — must comply

with a subpoena, and the tapes were released. Attention soon turned to a

smoking-gun recording implicating Mr. Nixon in the cover-up. On Aug. 8, 1974, he

resigned.

Two lessons emerge. First: Congressional committees are powerful tools for

investigating the full range of abuse of power by a president and for passing

reforms to avoid repetitions of those abuses. (Unfortunately, reforms enacted

after Watergate were eroded over subsequent decades.) But committees have

limited power to compel presidential compliance with demands for evidence.

Second, prosecutors can often obtain the critical evidence that committees

can’t. But their job is to prosecute crimes. They are less likely to get to the

bottom of executive abuses or to prevent their repetition. Most tellingly,

special prosecutors, as part of the executive branch, can be dismissed by the

president, while congressional committees are protected by the constitutional

separation of powers.

That’s why the work of both is so important. Robert S. Mueller III has been

appointed special counsel to look into possible Russian meddling in the 2016

campaign, an investigation that might cover both criminal and

counterintelligence matters. Some senators say this will conflict with and

perhaps necessarily limit congressional inquiries.

But that needn’t be the case. While prosecutors prefer not having congressional

competition, a mature special prosecutor and a well-led congressional inquiry

can coordinate over issues like witness immunity. Congress can creatively expand

its witness list beyond prosecution targets and fill in critical details from

“satellite” witnesses, as the Watergate committee did with Mr. Butterfield.

Bipartisanship will be crucial. Working with the evidence secured by

prosecutors, congressional committees can provide a declassified narrative of

Russian actions and whether Trump aides colluded. If the committee is

aggressive, and its work is truly bipartisan, it can not only educate and

reassure the public, but also legislate solutions to prevent future abuses.

A reclusive Mr. Nixon worked behind the scenes to impede investigators and

prosecutors. He believed that his secret tapes would bring down John Dean;

instead they fertilized the bipartisan outrage that brought about his own

demise. But that bipartisanship didn’t exist when the Watergate committee began

its work. In today’s hyperpartisan atmosphere, that is worth remembering.

Scott

Armstrong, a former Washington Post reporter, is the president of Searchlight

New Mexico, an investigative news organization.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook and Twitter (@NYTopinion),

and sign up for the Opinion Today newsletter.

What to

Remember About Watergate,

NYT,

May 20, 2017,

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/20/

opinion/sunday/trump-nixon-watergate-congress.html

Peter M. Flanigan,

Banker

and Nixon Aide,

Dies at

90

July 31,

2013

The New York Times

By DOUGLAS MARTIN

Peter M.

Flanigan, a Wall Street investment banker who became one of President Richard M.

Nixon’s most trusted, influential and well-connected aides on business and

economic matters, died on Monday in Salzburg, Austria. He was 90.

His family announced the death.

Mr. Flanigan, an executive at the venerable investment house Dillon, Read &

Company, was an early and strong supporter of Nixon before being appointed

principal presidential assistant for financial matters. His facility in

advancing business interests in regulatory agencies led Time magazine to label

him “Mr. Fixit.”

His wide-ranging assignments included securities regulation, antitrust matters,

and agricultural and environmental policies. Administration officials compared

his influence on business issues to Henry A. Kissinger’s on foreign affairs.

“He’s the guy who people in our industry turn to,” a steel executive told The

New York Times in 1972. “And we wouldn’t turn to him unless he came through.”

Mr. Nixon applauded his contributions to international economic policy and to

the country’s moving to an all-volunteer Army. But some saw him as the face of

an administration that had cozied up to business interests. Ralph Nader, the

consumer advocate, acknowledged Mr. Flanigan’s influence by calling him a

“mini-president.” He also called him the “most evil” man in Washington.

Mr. Flanigan was sharply criticized in Congress for his role in the Justice

Department’s decision not to pursue an antitrust case against the International

Telephone and Telegraph Corporation as an illegal conglomerate. He had arranged

for a colleague at Dillon, Read to draft a financial analysis that helped

persuade the administration to drop antitrust charges.

At a hearing in 1972, Senator Thomas F. Eagleton, a Missouri Democrat,

characterized Mr. Flanigan’s interventions on behalf of business as “the

Flanigan factor.” The senator accused him of holding back enforcement actions by

the Environmental Protection Agency against the Anaconda Corporation and the

Armco Steel Corporation.

Mr. Eagleton called Mr. Flanigan “the mastermind, the possessor of the scuttling

feet that are heard faintly, retreating into the distance in the wake of a White

House ordered cave-in to some giant corporation.”

The White House press secretary, Ronald L. Ziegler, responded that the president

wholly supported Mr. Flanigan. He demanded “concrete evidence that Mr. Flanigan

has gained personally in any way.” Senator Norris Cotton, a New Hampshire

Republican, called Mr. Eagleton’s charges “flimsy.”

Mr. Flanigan was unruffled. “I’ve gotten, as my wife says, a little leathery,”

he told The Washington Post. “It’s an election year, and I note who’s making

these charges.”

He left the administration in June 1974, just weeks before the Watergate scandal

forced Nixon to resign. Mr. Flanigan himself was not linked to the scandal.

President Gerald R. Ford, Nixon’s successor, nominated him to be ambassador to

Spain, but the Senate did not vote on his appointment before a scheduled recess.

Some senators said that Mr. Flanigan had arranged for prestigious

ambassadorships to go to big Nixon contributors. Mr. Flanigan asked that his

nomination not be resubmitted.

Peter Magnus Flanigan was born on June 21, 1923, in Manhattan and raised there.

His father, Horace Flanigan, who was known as Hap, was chairman of the

Manufacturers Trust Company, later Manufacturers Hanover. His mother, the former

Aimee Magnus, was a granddaughter of Adolphus Busch, co-founder of

Anheuser-Busch.

Mr. Flanigan was a Navy carrier pilot in World War II, then graduated summa cum

laude from Princeton. He joined Dillon as a statistical analyst. He took a break

in 1949-50 to work in London for the Marshall Plan, the initiative to rebuild

war-ravaged Europe, then returned to Dillon. He became a vice president in 1954.

Mr. Flanigan became active in New York Republican politics in the mid-1950s and

was named chairman of New Yorkers for Nixon in 1959 as Nixon, then vice

president, was seeking the 1960 presidential nomination. Mr. Flanigan became

national director of Nixon volunteers in 1960.

Nixon wrote in his memoirs in 1978 that Mr. Flanigan was one of a small group of

Republicans who had raised money for him to campaign for Republican candidates

in the 1966 midterm elections as an early step toward Nixon’s seeking the 1968

nomination.

In 1968, he was Nixon’s deputy campaign manager. After Nixon’s victory, Mr.

Flanigan was a talent scout for the transition team. He served as a presidential

assistant until 1972, when he was named director of the Council of International

Economic Policy.

Mr. Flanigan’s first wife, the former Brigid Snow, died in 2006.

Mr. Flanigan is survived by his second wife, Dorothea von Oswald, whom he

married five years ago and with whom he lived in Wildenhag, Austria, and

Purchase, N.Y. He is also survived by his daughters Sister Louise Marie, Brigid

and Megan; his sons Tim and Bob; and 16 grandchildren.

After his White House service, Mr. Flanigan returned to Dillon, where he was

managing director until 1992. The passion of his latter years was education,

notably starting a program to help inner-city Roman Catholic schools. He was

chairman of the Alliance for School Choice. His great love was St. Ann’s Roman

Catholic School in East Harlem, to which he gave more than $250,000.

His visits there were appreciated. “I want to make something of myself,”

Lawrence King, a seventh grader, told The Times in 1992. “It’s important to have

someone to look up to.”

Peter M. Flanigan, Banker and Nixon Aide, Dies at 90, NYT, 31.7.2013,

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/01/us/

peter-m-flanigan-banker-and-nixon-aide-dies-at-90.html

Charles W. Colson,

Watergate Felon

Who Became Evangelical Leader,

Dies at

80

April 21,

2012

The New York Times

By TIM WEINER

Charles W.

Colson, who as a political saboteur for President Richard M. Nixon masterminded

some of the dirty tricks that led to the president’s downfall, then emerged from

prison to become an important evangelical leader, saying he had been “born

again,” died on Saturday. He was 80.

The cause was complications of a brain hemorrhage, according to Prison

Fellowship Ministries, which Mr. Colson founded in Lansdowne, Va. He died at

Inova Fairfax Hospital in Falls Church, Va., and lived in Naples, Fla., and

Leesburg, Va.

Mr. Colson had brain surgery to remove a clot after becoming ill on March 30

while speaking at a conference, according to Jim Liske, the group’s chief

executive.

Mr. Colson was sent to prison after pleading guilty to obstructing justice in

one of the criminal plots that undid the Nixon administration. After having what

he called his religious awakening behind bars, he spent much of the rest of his

life ministering to prisoners, preaching the Gospels and forging a coalition of

Republican politicians, evangelical church leaders and Roman Catholic

conservatives that has had a pronounced influence on American politics.

It was a remarkable reversal.

Mr. Colson was a 38-year-old Washington lawyer when he joined the Nixon White

House as a special counsel in November 1969. He quickly caught the president’s

eye. His “instinct for the political jugular and his ability to get things done

made him a lightning rod for my own frustrations,” Nixon wrote in his memoir,

“RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon.” In 1970, the president made him his

“political point man” for “imaginative dirty tricks.”

“When I complained to Colson, I felt confident that something would be done,”

Nixon wrote. “I was rarely disappointed.”

Mr. Colson and his colleagues “started vying for favor on Nixon’s dark side,”

Bryce Harlow, a former counselor to the president, said in an oral history.

“Colson started talking about trampling his grandmother’s grave for Nixon and

showing he was as mean as they come.”

As the president’s re-election campaign geared up in 1971, “everybody went

macho,” Mr. Harlow said. “It was the ‘in’ thing to swagger and threaten.”

Few played political hardball more fiercely than Mr. Colson. When a deluded

janitor from Milwaukee shot Gov. George C. Wallace of Alabama on the

presidential campaign trail in Maryland in May 1972, Nixon asked about the

suspect’s politics. Mr. Colson replied, “Well, he’s going to be a left-winger by

the time we get through.” He proposed a political frame-up: planting leftist

pamphlets in the would-be killer’s apartment. “Good,” the president said, as

recorded on a White House tape. “Keep at that.”

Mr. Colson hired E. Howard Hunt, a veteran covert operator for the Central

Intelligence Agency, to spy on the president’s opponents. Their plots became

part of the cascade of high crimes and misdemeanors known as the Watergate

affair.

The subterfuge began to unravel after Mr. Hunt and five other C.I.A. and F.B.I.

veterans were arrested in June 1972 after a botched burglary and wiretapping

operation at Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate office

complex in Washington. To this day, no one knows whether Nixon authorized the

break-in or precisely what the burglars wanted.

“When I write my memoirs,” Mr. Colson told Mr. Hunt in a November 1972 telephone

conversation, “I’m going to say that the Watergate was brilliantly conceived as

an escapade that would divert the Democrats’ attention from the real issues, and

therefore permit us to win a landslide that we probably wouldn’t have won

otherwise.” The two men laughed.

That month, Nixon won that landslide. On election night, the president watched

the returns with Mr. Colson and the White House chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman.

“I couldn’t feel any sense of jubilation,” Mr. Colson said in a 1992 television

interview. “Here we were, supposedly winning, and it was more like we’d lost.”

“The attitude was, ‘Well, we showed them, we got even with our enemies and we

beat them,’ instead of ‘We’ve been given a wonderful mandate to rule over the

next four years,’ ” he said. “We were reduced to our petty worst on the night of

what should have been our greatest triumph.”

The Watergate operation and the dirty tricks campaign surrounding it led to the

criminal indictments and convictions of most of Nixon’s closest aides. On June

21, 1974, Mr. Colson was sentenced to prison and fined $5,000. Nixon resigned

seven weeks later after one of his secretly recorded White House tapes made

clear that he had tried to use the C.I.A. to obstruct the federal investigation

of the break-in.

Mr. Colson served seven months after pleading guilty to obstructing justice in

the case of Daniel Ellsberg, a former National Security Council consultant who

leaked the Pentagon Papers, a secret history of the Vietnam War, to The New York

Times. In July 1971, a few weeks after the papers were published, Mr. Colson

approved Mr. Hunt’s proposal to steal files from the office of Mr. Ellsberg’s

psychiatrist. The aim was “to destroy his public image and credibility,” Mr.

Hunt wrote.

“I went to prison, voluntarily,” Mr. Colson said in 2005. “I deserved it.”

He announced upon emerging that he would devote the rest of his life to

religious work. In 1976, he founded Prison Fellowship Ministries, which delivers

a Christian message of redemption to thousands of prison inmates and their

families. In 1983, he established Justice Fellowship, which calls itself the

nation’s largest religion-based criminal justice reform group. In 1993, he won

the $1 million Templeton Prize for Progress in Religion, and donated it to his

ministries.

By the end of the 1990s, Mr. Colson had become a leading voice in the

evangelical political movement, with books and a syndicated radio broadcast. He

helped form a conservative coalition of leaders from the Republican Party, the

Protestant evangelical community and the Catholic Church. The Catholics and the

evangelicals, once combatants over issues of religious doctrine, now joined

forces in fights over abortion rights and religious freedom, among other issues.

Mr. Colson also reached out to the Rev. Richard John Neuhaus, a Catholic

theologian who edited the journal First Things and who had warned of a coming

tide of secularism in his book “The Naked Public Square.” They inaugurated a

theological dialogue that resulted in the publication of the document

“Evangelicals and Catholics Together” in 1994.

Mr. Colson said that he had initially gotten hate mail from evangelicals because

of that initiative, and that the Prison Fellowship had lost a million dollars in

donations. But the manifesto, pushing for religion-based policies in government,

cleared the path for a political and cultural alliance that has reshaped the

political debate in America, adding fuel to a rightward turn in the Republican

Party and a rising conservative grass-roots movement.

In 2000, Mr. Colson was a resident of Florida when Gov. Jeb Bush restored his

rights to practice law, vote and serve on a jury — all of them having been lost

with his federal felony conviction. “I think it’s time to move on,” Mr. Bush

said at the time. “I know him. He’s a great guy.”

With that, Mr. Colson re-entered the political arena. In January 2001, six days

after President George W. Bush’s inauguration, a Wall Street Journal editorial

praised Mr. Colson’s prison work as “a model for Bush’s ideas about faith-based

funding.”

When he went to the White House to state his case for religious faith as a basis

for foreign and domestic policies, he found himself pushing on an open door.

“You don’t have to tell me,” Mr. Colson said the president told him. “I’d still

be drinking if it weren’t for what Christ did in my life. I know faith-based

works.”

In 2006, a federal judge ruled that a religion-based program operated by a

Prison Fellowship affiliate in Iowa had violated the constitutional separation

of church and state. By using tax money for a religious program that gave

special privileges to inmates who embraced evangelical Christianity, the state

had established a congregation and given its leaders “authority to control the

spiritual, emotional, and physical lives of hundreds of Iowa inmates,” the judge

said.

Mr. Colson blasted the ruling, and Prison Fellowship appealed it. But in October

2006, after turning 75, he stepped down as the chairman of the group to devote

himself to writing and speaking for his causes. In 2008, President Bush awarded

him the Presidential Citizens Medal.

Charles Wendell Colson — friends called him Chuck — was born on Oct. 16, 1931,

in Boston, the only child of Wendell B. and Inez Ducrow Colson, His father was a

struggling lawyer; his mother, nicknamed Dizzy, was an exuberant spendthrift.

He grew up at 15 different addresses in and around the city and attended eight

schools. He got his first taste of politics as a teenage volunteer in Robert F.

Bradford’s re-election campaign for governor of Massachusetts. He remembered

that he learned “all the tricks,” including “planting misleading stories in the

press, voting tombstones, and spying on the opposition in every possible way.”

He graduated from Browne & Nichols, a private school in Cambridge, in 1949, and

went to Brown University with a scholarship from the Navy Reserve Officer

Training Program. After graduating in 1953, he married his college sweetheart,

Nancy Billings, and joined the Marines.

In 1956, Mr. Colson went to Washington as an administrative assistant to Senator

Leverett Saltonstall, a Massachusetts Republican. He met Nixon, who was then

vice president, and became, in his words, a lifelong “Nixon fanatic.” The two

men “understood each other,” Mr. Colson wrote in “Born Again,” his memoir. They

were “prideful men seeking that most elusive goal of all — acceptance and the

respect of those who had spurned us.”

After obtaining a law degree from George Washington University in 1959, Mr.

Colson became partner in a Washington law firm, always practicing politics on

the side, with an eye to a Nixon presidency. He was crushed when his candidate

lost the 1960 election by a whisker to Senator John F. Kennedy.

A sympathetic biography, “Charles W. Colson: A Life Redeemed” (2005), by

Jonathan Aitken, depicts him in these years as a hard-drinking, chain-smoking,

amoral man with three young children — Wendell Ball II, Christian and Emily Ann

— and a failing marriage. He divorced his first wife and married Patricia Ann

Hughes in 1964.

She, the three children, and five grandchildren are among Mr. Colson’s

survivors.

In 1973, while looking for work after leaving the White House and fearing that

he was going to wind up in jail, Mr. Colson got into his car and found himself

in the grip of the spiritual crisis that led to his conversion. “This so-called

White House hatchet man, ex-Marine captain, was crying too hard to get the keys

into the ignition,” he remembered. “I sat there for a long time that night

deeply convicted of my own sin.”

Laurie

Goodstein contributed reporting.

Charles W. Colson, Watergate Felon Who Became Evangelical Leader, Dies at 80,

NYT, 21.4.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/22/us/politics/

charles-w-colson-watergate-felon-who-became-

evangelical-leader-dies-at-80.html

Frank H. Strickler,

Watergate Defense Lawyer,

Dies at

92

April 9,

2012

The New York Times

By DOUGLAS MARTIN

Frank H.

Strickler, a Washington lawyer who represented two of President Richard M.

Nixon’s top aides, H. R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, in the tangled legal

aftermath of the 1972 Watergate break-in and its cover-up, died March 29 at his

home in Chevy Chase, Md. He was 92.

His family announced the death.

Mr. Strickler participated in several dramatic moments in the aftermath of the

burglary at the offices of the Democratic National Committee in the Watergate

complex in Washington on June 17, 1972. But he did not leap into the case at the

first opportunity.

The day of the break-in, he grumpily answered the phone at his vacation home in

Bethany Beach, Del., after being awakened at 4:30 a.m. The caller was E. Howard

Hunt, a former C.I.A. agent who was later convicted for helping organize the

Watergate operation, according to the book “Nightmare: The Underside of the

Nixon Years” (1973), by J. Anthony Lukas.

“You think I’m going to interrupt my vacation and represent anybody like that?”

Mr. Strickler said. “You’re crazy!”

But as the case evolved into an investigation of the cover-up by Nixon and his

aides, Mr. Strickler and one of his law partners, John J. Wilson, agreed to

represent Mr. Haldeman, Nixon’s chief of staff, and Mr. Ehrlichman, his counsel

and domestic policy adviser. Mr. Ehrlichman later retained his own lawyer, a

decision Mr. Strickler said made strategic sense.

In one of Watergate’s tensest moments, Mr. Strickler and Mr. Wilson met for an

hour and six minutes with President Nixon on April 19, 1973, in an effort to

persuade him not to request the resignation of their clients.

John Dean, the White House counsel, had begun cooperating with prosecutors in

the hope of lenient treatment for himself. Both Mr. Haldeman and Mr. Ehrlichman

had reason to worry about the testimony of Mr. Dean, who was estranged from

them. In the White House, the pair were called “the Berlin Wall,” as much for

their power as for their Germanic names.

According to Mr. Lukas, Mr. Strickler told the president that removal of his

clients would strike the public as “an admission of guilt.” Nixon replied that

the two were “great, fine Americans” and that he would try to save them. He

fired Mr. Dean and accepted the resignations of Mr. Haldeman and Mr. Ehrlichman

on April 30.

On the eve of Nixon’s own resignation on Aug. 9, 1974, Mr. Haldeman wanted to

make made a last-ditch bid for a presidential pardon. Mr. Strickler again was at

the center of the action.

He told his client to write a personal memo to Nixon. He and Mr. Wilson supplied

legal backup. They suggested pardoning all those accused or convicted of crimes

related to Watergate, as well as all Vietnam-era draft evaders. Nixon elected to

do neither.

In February 1974, investigators offered Mr. Ehrlichman a chance to plead guilty

to a single charge in return for his help in building a case against others. He

said no. “His feeling was that he could not plead guilty to something that he

did not believe he was guilty of doing,” Mr. Strickler said in an interview with

The New York Times. In “Stonewall: The Real Story of the Watergate Prosecution”

(1977), the Watergate prosecutors Richard Ben-Veniste and George Frampton Jr.

wrote that Mr. Haldeman was offered, and turned down, a similar deal.

Both men were eventually convicted and sentenced to two and a half to eight

years in prison. The sentences were commuted to one to four years. Each served a

total of 18 months.

Before the trial of Mr. Haldeman, Mr. Ehrlichman and three other Nixon aides

began in November 1974, Mr. Strickler unsuccessfully argued that the case

against Mr. Haldeman be dismissed because of the leaking of potentially damaging

grand jury testimony. During the trial, Mr. Strickler contended that Mr.

Haldeman’s intercession in the F.B.I.’s initial Watergate investigation resulted

from his desire to protect a sensitive C.I.A. operation in Mexico.

He also argued that Mr. Haldeman was busy with matters far more important to the

nation than Watergate. He called the matter “no more than a pimple on the mound

of his other duties.”

Frank Hunter Strickler was born on Jan. 20, 1920, in Washington, and earned

undergraduate and law degrees from George Washington University. He helped pay

for his education by working as a fingerprint examiner for the F.B.I. He served

in the merchant marine during World War II as a seaman and cook. He was a

federal prosecutor in Washington in the early 1950s, and then in private

practice.

Mr. Strickler is survived by his wife of 57 years, Ellis Barnard Strickler; his

daughters, Nancy Strickler Borah and Elizabeth Ann Strickler; his sons, Frank

and Charles; and three grandchildren.

Frank H. Strickler, Watergate Defense Lawyer, Dies at 92, NYT, 9.4.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/10/us/politics/frank-h-strickler-a-watergate-defense-lawyer-is-dead-at-92.html

Henry S. Ruth,

Who

Helped Lead

Watergate Prosecution,

Dies at

80

March 27,

2012

The New York Times

By DOUGLAS MARTIN

Henry S.

Ruth Jr., who helped lead the criminal prosecution of Nixon administration

officials involved in covering up the Watergate break-in and kept it on track

when President Richard M. Nixon fired the special prosecutor Archibald Cox, died

on March 16 in Tucson. He was 80.

The cause was a stroke, his wife, Deborah Mathieu, said.

Mr. Ruth had broad experience in criminal law when he became Mr. Cox’s chief

deputy shortly after Mr. Cox’s appointment as special prosecutor in May 1973.

Five months later, on Oct. 20, President Nixon ordered Mr. Cox’s dismissal after

he refused to drop his plan to subpoena tapes of the president’s conversations

in the Oval Office. The firing prompted the two top Justice Department

officials, Attorney General Elliot Richardson and his deputy, William

Ruckelshaus, to quit in what became known as the Saturday Night Massacre.

The case concerned the possible involvement of Nixon and his aides in covering

up the June 1972 break-in at the Democratic national headquarters in the

Watergate apartment complex by burglars who turned out to have ties to Nixon’s

re-election campaign. A Nixon aide, Alexander P. Butterfield, had revealed the

existence of the secret tapes to a Senate investigative committee in July 1973.

In the upheaval that followed Mr. Cox’s dismissal — when it was not known

whether the special prosecutor’s office would continue and, if it did, what

powers it might have — Mr. Ruth was credited with holding the office together.

He gathered the distraught staff around him and persuaded them to stay on and

preserve the evidence, The New York Times reported.

On Nov. 1, Leon Jaworski, a prominent lawyer from Texas, became special

prosecutor. Asking Mr. Ruth to remain as his deputy was his first piece of

business, Mr. Jaworski wrote in “The Right and the Power: The Prosecution of

Watergate” (1976). “He is a slender, mild-mannered man, so unassuming that some

people, on first meeting, were inclined to misjudge his talents,” Mr. Jaworski

wrote of Mr. Ruth.

In “The Final Days” (1976), Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein wrote that Mr. Ruth

had met privately with Leonard Garment, Nixon’s special counsel, to ask if Mr.

Garment could persuade the president to resign. Mr. Garment said he had already

tried and failed.

Under Mr. Jaworski, the prosecutors persuaded the Supreme Court to order that

the tapes be turned over to prosecutors, and the top Nixon aides H. R. Haldeman,

John Ehrlichman, Charles Colson and John N. Mitchell, the former attorney

general, were either convicted or pleaded guilty.

As evidence mounted and the House of Representatives prepared articles of

impeachment against the president, Nixon resigned on Aug. 8, 1974. President

Gerald R. Ford issued a blanket pardon of Nixon the next month.

When Mr. Jaworski stepped down two months later, he urged that Mr. Ruth replace

him. Mr. Ruth’s first act was to challenge part of the pardon deal that

restricted his access to tapes. He won: the special prosecutor was given full

access.

Mr. Ruth was special prosecutor until October 1975, when he issued a 277-page

report on the Watergate investigation. It said prosecutors had thus far

convicted or obtained guilty pleas from 55 individuals and 20 corporations. They

had been unable to determine who was responsible for erasing 18 1/2 minutes of a

Nixon tape that many thought might have been incriminating, the report said,

even though “a very small number of people could have been responsible.”

The report disclosed that prosecutors had explored whether Ford’s pardon

amounted to illegal interference with the mandate of the special prosecutor. But

both Mr. Jaworski and Mr. Ruth concluded that the president’s power to pardon

was stronger than the mandate.

Charles F. Ruff succeeded Mr. Ruth as the fourth and last special Watergate

prosecutor.

Henry Swartley Ruth Jr. was born in Philadelphia on April 16, 1931; graduated

from Yale and the University of Pennsylvania Law School; served two years in the

Army; and worked as a private lawyer. He was a special attorney under Attorney

General Robert F. Kennedy. After teaching law at Penn for two years, he returned

to the Justice Department in its research arm, the National Institute of Law

Enforcement and Criminal Justice. A year later, he became criminal justice

coordinator for New York City under Mayor John V. Lindsay.

Mr. Ruth’s first marriage, to Christine Polk, ended in divorce. In addition to

his wife, Ms. Mathieu, he is survived by his daughters, Deborah, Diana and

Tenley Ruth, and three grandsons.

After his Watergate work, Mr. Ruth worked mainly in private practice. John Dean,

a Nixon aide, wrote in his book “Blind Ambition: The White House Years” (1976)

that he once asked Mr. Ruth what he planned to do in the future.

Mr. Ruth replied that he might do American Express commercials, of the sort that

made fun of forgotten celebrities who had fallen from the limelight. “You may

not remember me, but I’m the Watergate special prosecutor,” he said, holding up

a credit card, as if he were in a commercial. “I used American Express all

through Watergate, because nobody knew who I was,” he continued. “And they still

don’t know who I am.”

Henry S. Ruth, Who Helped Lead Watergate Prosecution, Dies at 80,

NYT,

27.3.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/27/us/henry-s-ruth-who-helped-lead-watergate-prosecution-dies-at-80.html

Newly

Released Transcripts

Show a

Bitter and Cynical Nixon

in ’75

November

10, 2011

The New York Times

By ADAM NAGOURNEY

and SCOTT SHANE

For 11

hours of secret grand jury testimony 36 years ago, Richard M. Nixon, a disgraced

former president, fenced with prosecutors over his role in the Watergate

scandals, bemoaned politics as a dirty business played by both sides and testily

— as he described his own demeanor — suggested he was the victim of a special

prosecutor’s office loaded with Democrats.

The testimony, which Nixon presumably thought would always remain secret, was

released by the Nixon Presidential Library and Museum in Yorba Linda, Calif., on

Thursday in response to an order by a judge. The transcripts offered a

remarkable portrait of Nixon after he left office: bitter at his disgrace and

cynical about politics. He presented himself as a victim of governmental abuses

by his enemies during his long career in politics, and said that prosecutors,

with an eye to ingratiating themselves with the Washington media “and the

Georgetown set,” were out to destroy him.

“In politics, some pretty rough tactics are used,” he said. “We deplore them

all.”

At one point, as he denied that his White House had engaged in anything out of

the ordinary, he spoke with grudging admiration of what he said were the

hardball tactics used against him by the Kennedy White House, asserting that it

had directed the I.R.S. and other government agencies to discredit him as he ran

for governor of California.

“They were pretty smart, I guess,” he said. “Rather than using a group of

amateur Watergate bugglers, burglars — well they were bunglers — they used the

F.B.I., used the I.R.S. and used it directly by their own orders against, in one

instance, a man who had been vice president of the United States, running for

governor.”

By the time Nixon appeared at the grand jury, on June 23 and 24 of 1975, he had,

by virtue of his pardon by Gerald R. Ford, immunity from any crimes he had

committed, though he was still subject to perjury charges based on what he said

to this grand jury. Nixon, a lawyer, repeatedly answered questions in a hedged

and clipped manner, often saying he did not recall conversations, some of them

just two years old.

“I never recall any income tax return; I never recall seeing any result of any

of this done,” he said.

Nixon repeatedly reminded his questioners that he had been preoccupied with

grave matters of state, including the war in Vietnam. He seemed aware of how

much he was claiming a failure of memory. “I want the grand jurors to understand

that when I say I don’t recognize something, it isn’t because I am trying want

to duck a question,” he said.

Stanley J. Kutler, a historian whose years of litigation helped lead to the

release of the material, said he expected no shocking revelations from Nixon’s

testimony. But the hours of Nixon talking and sparring are a window on the

personality of the 37th president.

“If you know the voice of Richard Nixon, it’s a virtuoso performance, from the

awkward attempts at humor to the moments of self-pity,” said Mr. Kutler,

emeritus professor of history at the University of Wisconsin. “It’s just

terrific stuff.”

In the course of his testimony, Nixon appeared to flatly deny accusations that

the White House had used the I.R.S. to try to discredit a sitting chairman of

the Democratic National Committee, Lawrence O’Brien, and that he had an enemies

list. Tim Naftali, the director of Mr. Nixon’s library, noted that in the

Watergate exhibit on display there, there are tapes in which Nixon is heard

ordering the use of tax audits against opponents and assembling an enemies list.

“The grand jury testimony sheds more light on President Nixon’s personality and

character than it does on the remaining puzzles of Watergate,” Mr. Naftali said.

“Even under the protections of grand jury secrecy, which was inviolate at that

point, the president, it appears, was unwilling to be more forthright about his

role in what the House Judiciary Committee determined were abuses of government

power.”

Mr. Naftali noted that even with the protections of the grand jury testimony,

Nixon did not answer what has been one of the biggest outstanding questions from

the Watergate scandal: The reason for the 18 ½-minute gap in a tape recorded in

the Oval Office.”

The distinctive Nixonian blend of pugnaciousness and self-pity comes through

clearly in the 297 pages. Prosecutors’ tape experts were “these clowns.” He

refers to G. Gordon Liddy, who headed the White House plumbers, as “a very

bright young man in one way, very stupid in others.”

At another point, Nixon asserted that “as a result of my orders, and I gave them

directly, that never to my knowledge was anybody in my responsibility for

heckling” George McGovern, Nixon’s Democratic opponent in 1972.

“Now, actually my decision was not all that altruistic, to be quite honest,”

Nixon said. “My decision was based on the fact that I didn’t think it would do

any good. Why martyr the poor fellow? He was having enough trouble.”

Nixon even directed some humor at himself, as he recalled telling Alexander M.

Haig Jr., to look into the 18 ½-minute gap on the White House tapes. “I said to

him, ‘Let’s find out how this damn thing happened,’ ” Nixon said. “I am sorry, I

wasn’t supposed to use profanity. You have enough on the tapes.”

Nixon returns again and again to the notion that he was singled out for conduct

that was common in politics and public life.

He said he was the target of eavesdropping not just by Democrats but by the

F.B.I.

“The F.B.I. was at one point directed to bug my plane,” he said, and J. Edgar

Hoover, the F.B.I. director, “once told me that they did.”

Despite the decades that have passed, some passages were redacted because they

contained still-classified information. Nixon told prosecutors that “only if

there is an absolute guarantee that there will not be disclosure of what I say,

I will reveal for the first time information with regard to why wiretaps were

proposed, information which, if it is made public, will be terribly damaging to

the United States.” But his disclosure appears to have been cut from the

transcript.

In a ruling last July in historians’ litigation over the Nixon archives, Judge

Royce C. Lamberth of the District Court in Washington said he believed that the

historical importance of Nixon’s testimony justified a rare exception to the

standard secrecy of grand jury records.

Nixon often flashed his disdain for the prosecutors, whether he was belittling

the way they asked their questions or accusing them of being partisan. “You can

play that trick all, all day,” Nixon admonished the prosecutor. “We can take all

day on that. Ask the question properly.”

“I am not unaware that the vast majority of people working in the special

prosecutor’s office did not support me for president,” he said.

Ian Lovett and

John Schwartz contributed reporting.

Newly Released Transcripts Show a Bitter and Cynical Nixon

in ’75, NYT, 10.11.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/11/us/newly-released-transcripts-show-a-combative-richard-nixon.html

Nixon Resigns

By Carroll Kilpatrick

Washington Post Staff Writer

Friday, August 9, 1974

Page A01

Richard Milhous Nixon announced last night that he will resign as the 37th

President of the United States at noon today.

Vice President Gerald R. Ford of Michigan will take the oath as the new

President at noon to complete the remaining 2 1/2 years of Mr. Nixon's term.

After two years of bitter public debate over the Watergate scandals, President

Nixon bowed to pressures from the public and leaders of his party to become the

first President in American history to resign.

"By taking this action," he said in a subdued yet dramatic television address

from the Oval Office, "I hope that I will have hastened the start of the process

of healing which is so desperately needed in America."

Vice President Ford, who spoke a short time later in front of his Alexandria

home, announced that Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger will remain in his

Cabinet.

The President-to-be praised Mr. Nixon's sacrifice for the country and called it

"one of the vary saddest incidents that I've every witnessed."

Mr. Nixon said he decided he must resign when he concluded that he no longer had

"a strong enough political base in the Congress" to make it possible for him to

complete his term of office.

Declaring that he has never been a quitter, Mr. Nixon said that to leave office

before the end of his term " is abhorrent to every instinct in my body."

But "as President, I must put the interests of America first," he said.

While the President acknowledged that some of his judgments "were wrong," he

made no confession of the "high crimes and misdemeanors" with which the House

Judiciary Committee charged him in its bill of impeachment.

Specifically, he did not refer to Judiciary Committee charges that in the

cover-up of Watergate crimes he misused government agencies such as the FBI, the

Central Intelligence Agency and the Internal Revenue Service.

After the President's address, Special Prosecutor Leon Jaworski issued a

statement declaring that "there has been no agreement or understanding of any

sort between the President or his representatives and the special prosecutor

relating in any way to the President's resignation."

Jaworski said that his office "was not asked for any such agreement or

understanding and offered none."

His office was informed yesterday afternoon of the President's decision,

Jaworski said, but "my office did not participate in any way in the President's

decision to resign."

Mr. Nixon's brief speech was delivered in firm tones and he appeared to be

complete control of his emotions. The absence of rancor contrasted sharply with

the "farewell" he delivered in 1962 after being defeated for the governorship of

California.

An hour before the speech, however, the President broke down during a meeting

with old congressional friends and had to leave the room.

He had invited 20 senators and 26 representatives for a farewell meeting in the

Cabinet room. Later, Sen. Barry M. Goldwater (R-Ariz.), one of those present,

said Mr. Nixon said to them very much what he said in his speech.

"He just told us that the country couldn't operate with a half-time President,"

Goldwater reported. "Then he broke down and cried and he had to leave the room.

Then the rest of us broke down and cried."

In his televised resignation, after thanking his friends for their support, the

President concluded by saying he was leaving office "with this prayer: may God's

grace be with you in all the days ahead."

As for his sharpest critics, the President said, "I leave with no bitterness

toward those who have opposed me." He called on all Americans to "join together

. . . in helping our new President succeed."

The President said he had thought it was his duty to persevere in office in face

of the Watergate charges and to complete his term.

"In the past days, however, it has become evident to me that I no longer have a

strong enough political base in the Congress to justify continuing that effort,"

Mr. Nixon said.

His family "unanimously urged" him to stay in office and fight the charges

against him, he said. But he came to realize that he would not have the support

needed to carry out the duties of his office in difficult times.

"America needs a full-time President and a full-time Congress," Mr. Nixon said.

The resignation came with "a great sadness that I will not be here in this

office" to complete work on the programs started, he said.

But praising Vice President Ford, Mr. Nixon said that "the leadership of America

will be in good hands."

In his admission of error, the outgoing President said: "I deeply regret any

injuries that may have been done in the course of the events that led to this

decision."

He emphasized that world peace had been the overriding concern of his years in

the White House.

When he first took the oath, he said, he made a "sacred commitment" to

"consecrate my office and wisdom to the cause of peace among nations."

"I have done my very best in all the days since to be true to that pledge," he

said, adding that he is now confident that the world is a safer place for all

peoples.

"This more than anything is what I hoped to achieve when I sought the

presidency," Mr. Nixon said. "This more than anything is what I hope will be my

legacy to you, to our country, as I leave the presidency."

Noting that he had lived through a turbulent period, he recalled a statement of

Theodore Roosevelt about the man "in the arena whose face is marred by dust and

sweat and blood" and who, if he fails "at least fails while daring greatly."

Mr. Nixon placed great emphasis on his successes in foreign affairs. He said his

administration had "unlocked the doors that for a quarter of a century stood

between the United States and the People's Republic of China."

In the mideast, he said, the United States must begin to build on the peace in

that area. And with the Soviet Union, he said, the administration had begun the

process of ending the nuclear arms race. The goal now, he said, is to reduce and

finally destroy those arms "so that the threat of nuclear war will no longer

hang over the world." The two countries, he added, "must live together in

cooperation rather than in confrontation."

Mr. Nixon has served 2,026 days as the 37th President of the United States. He

leaves office with 2 1/2 years of his second term remaining to be carried out by

the man he nominated to be Vice President last year.

Yesterday morning, the President conferred with his successor. He spent much of

the day in his Executive Office Building hideaway working on his speech and

attending to last-minute business.

At 7:30 p.m., Mr. Nixon again left the White House for the short walk to the

Executive Office Building. The crowd outside the gates waved U.S. flags and sang

"America" as he walked slowly up the steps, his head bowed, alone.

At the EOB, Mr. Nixon met for a little over 20 minutes with the leaders of

Congress -- James O. Eastland (D-Miss.), president pro tem to the Senate; Mike

Mansfield (D-Mont.), Senate majority leader; Hugh Scott (R-Pa.), Senate minority

leader; Carl Albert (D-Okla.), speaker of the House; and John Rhodes (R-Ariz.),

House minority leader.

It was exactly six years ago yesterday that the 55-year-old Californian accepted

the Republican nomination for President for the second time and went on to a

narrow victory in November over Democrat Hubert H. Humphrey.

"I was ready. I was willing. And events were such that this seemed to be the

time the party was willing for me to carry the standard," Nixon said after

winning first-ballot nomination in the convention at Miami Beach.

In his acceptance speech on Aug. 8, 1968, the nominee appealed for victory to

"make the American dream come true for millions of Americans."

"To the leaders of the Communist world we say, after an era of confrontation,

the time has come for an era of negotiation," Nixon said.

The theme was repeated in his first inaugural address on Jan. 20, 1969, and

became the basis for the foreign policy of his first administration.

Largely because of his breakthroughs in negotiations with China and the Soviet

Union, and partly because of divisions in the Democratic Party, Mr. Nixon won a

mammoth election victory in 1972, only to be brought down by scandals that grew

out of an excessive zeal to make certain he would win re-election.

Mr. Nixon and his family are expected to fly to their home in San Clemente,

Calif. early today. Press secretary Ronald L. Ziegler and Rose Mary Woods, Mr.

Nixon's devoted personal secretary for more than two decades, will accompany the

Nixons.

Alexander M. Haig Jr., the former Army vice chief of staff who was brought into

the White House as staff chief following the resignation of H.R. (Bob) Haldeman

on April 30, 1973, has been asked by Mr. Ford to remain in his present position.

It is expected that Haig will continue in the position as staff chief to assure

an orderly transfer of responsibilities but not stay indefinitely.

The first firm indication yesterday that the President had reached a decision

came when deputy press secretary Gerald L. Warren announced at 10:55 a.m. that

the President was about to begin a meeting in the Oval Office with the Vice

President.

"The President asked the Vice President to come over this morning for a private

meeting -- and that is all the information I have at this moment," Warren said.

He promised to post "some routine information, bill actions and appointments"

and to return with additional information" in an hour or so."

Warren's manner and the news he had to impart made it clear at last that

resignation was a certainty. Reports already were circulating on Capitol Hill

that the President would hold a reception for friends and staff members late in

the day and a meeting with congressional leaders.

Shortly after noon, Warren announced over the loudspeaker in the press room that

the meeting between the President and the Vice President had lasted for an hour

and 10 minutes.

At 2:20 p.m., press secretary Ziegler walked into the press room and, struggling

to control his emotions, read the following statement:

"I am aware of the intense interest of the American people and of you in this

room concerning developments today and over the last few days. This has, of

course, been a difficult time.

"The President of the United States will meet various members of the bipartisan

leadership of Congress here at the White House early this evening.

"Tonight, at 9 o'clock, Eastern Daylight Time, the President of the United

States will address the nation on radio and television from his Oval Office."

The room was packed with reporters, and Ziegler read the statement with

difficulty. Although his voice shook, it did not break. As soon as he had

finished, he turned on his heel and left the room, without so much as a glance

at the men and women in the room who wanted to question him.

There were tears in the eyes of some of the secretaries in the press office.

Others, who have been through many crises in recent years and have become used

to overwork, plowed ahead with their duties, with telephones ringing

incessantly.

In other offices, loyal Nixon workers reacted with sadness but also with

resignation and defeat. They were not surprised, and some showed a sense of

relief that at last the battle was over.

Some commented bitterly about former aides H.R. (Bob) Haldeman and John D.

Ehrlichman. The President's loyal personal aide and valet Manola Sanchez, a

Spanish-born immigrant from Cuba whose independence and wit are widely admired,

did not hide his feelings.

Speaking bluntly to some of his old friends, he castigated aides he said had

betrayed the President. One long-time official, who heard about the Sanchez

remarks, commented: "They [Haldeman and Ehrlichman] tried three times to fire

him because they couldn't control him. Imagine, trying to fire someone like

Manola."

But why did the President always rely on Ehrlichman and Haldeman? The official

was asked. "Will we ever know?" he replied. "When Mr. Nixon was Vice President,"

he recalled, "he demanded that we never abuse the franking privilege. If there

was any doubt, we were to use stamps. Everything had to be above board.

"Surely his friendship with Ehrlichman and Haldeman was one of the most

expensive in history."

But the President himself, said another long-time aide, must have been two

persons, the one who was motivated by high ideals and another who connived and

schemed with his favorite gut-fighters.

One man who worked through most of the first Nixon term said he saw the

President angry only once. Often he would say, "That will be tough politically,

but we must do the right thing."

When that official left his post after nearly four years of intimate association

with the President, he told his wife: "I've never gotten to know what sort of

man he is."

One official, who has known Mr. Nixon well for many years and remains a White

House aide, commented: "He is obviously a bad judge of character. But a lot was

accomplished. So much more could have been accomplished but for these fun and

games. It was such a stupid thing to happen."

The march of events that brought about the President's downfall turned its last

corner Monday when Mr. Nixon released the partial transcripts of three taped

conversations he held on June 23, 1972 with Haldeman.

It seemed inevitable then that this would be his last week in office, yet he

continued to fight back and to insist that he would not resign. On Tuesday, the

President held a Cabinet meeting and told his official family that he would not

resign.

On Wednesday, however, the end appeared near, for his support on Capitol Hill

was disappearing at dizzying speed. There were demands from some of his

staunchest supporters that he should resign at once.

Late Wednesday, the President met with Senate Minority Leader Hugh Scott

(R-Pa.), House Minority Leader John J. Rhodes (R-Ariz.) and Sen. Barry M.

Goldwater (R-Ariz.).

They said afterward that the President had made no decision, but it was obvious

later that for all intents and purposes the decision had been made despite what

the leaders said. They obviously could not make the announcement for him, but it

must have been apparent to them that the end was at hand.

Later Wednesday, Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger twice conferred with Mr.

Nixon, first in the early evening for half an hour and then from 9:30 p.m. until

midnight.

It was not known whether the two men were alone or accompanied by Haig and

others.

Yesterday, Kissinger met with principal deputies in the State Department to tell

them what to expect and to assign tasks to different people. Messages will be

sent to heads of state to notify them formally of the change.

A White House spokesman said more than 10,000 telephone calls were received in

the past two days expressing "disbelief and the hope that the President would

not resign."

Thursday was a wet, humid August day, but despite intermittent rain the crowds

packed the sidewalks in front of the White House. It was an orderly crowd,

resigned and curious, watching newsmen come and go and being a part of a

dramatic moment in the life of the nation.

Nixon

Resigns, By Carroll Kilpatrick, Washington Post Staff Writer,

Friday, August 9,

1974; Page A01,

http://www.washingtonpost.com/ac2/wp-dyn?pagename=article&contentId=A52946-2002Jun3¬Found=true

Judiciary Committee Approves

Article to

Impeach President Nixon, 27 to 11

6 Republicans Join Democrats

to Pass

Obstruction Charge

By Richard Lyons and William Chapman