|

History

> 20th, early 21st century > USA

Politics > Presidential election

President Bush's

State of the Union Address

February 2, 2005

The New York Times

The following is the transcript

of the State of the Union

Address

as recorded by Federal News Service.

PRESIDENT BUSH: Mr. Speaker, Vice President Cheney, members of

Congress, fellow citizens, as a new Congress gathers, all of us in the elected

branches of government share a great privilege. We've been placed in office by

the votes of the people we serve. And tonight, that is a privilege we share with

newly elected leaders of Afghanistan, the Palestinian territories, Ukraine, and

a free and sovereign Iraq. (Cheers, applause.)

Two weeks ago I stood on the steps of this Capitol and renewed the commitment of

our nation to the guiding ideal of liberty for all. This evening I will set

forth policies to advance that ideal at home and around the world. Tonight, with

a healthy, growing economy, with more Americans going back to work, with our

nation an active force for good in the world, the state of our union is

confident and strong. (Applause.)

Our generation has been blessed by the expansion of opportunity, by advances in

medicine, by the security purchased by our parents' sacrifice. Now, as we see a

little gray in the mirror -- or a lot of gray -- (laughter) -- and we watch our

children moving into adulthood, we ask the question, what will be the state of

their union? Members of Congress, the choices we make together will answer that

question. Over the next several months, on issue after issue, let us do what

Americans have always done and build a better world for our children and our

grandchildren. (Applause.)

First, we must be good stewards of this economy and renew the great institutions

on which millions of our fellow citizens rely. America's economy is the fastest

growing of any major industrialized nation. In the past four years we've

provided tax relief to every person who pays income taxes, overcome a recession,

opened up new markets abroad, prosecuted corporate criminals, raised

homeownership to its highest level in history, and in the last year alone the

United States has added 2.3 million new jobs. (Cheers, applause.)

When action was needed, the Congress delivered, and the nation is grateful. Now

we must add to these achievements. By making our economy more flexible, more

innovative, and more competitive, we will keep America the economic leader of

the world. (Applause.)

America's prosperity requires restraining the spending appetite of the federal

government. I welcome the bipartisan enthusiasm for spending discipline. I will

send you a budget that holds the growth of discretionary spending below

inflation, makes tax relief permanent, and stays on track to cut the deficit in

half by 2009. (Applause.)

My budget substantially reduces or eliminates more than 150 government programs

that are not getting results or duplicate current efforts or do not fulfill

essential priorities.

The principle here is clear: Taxpayer dollars must be spent wisely or not at

all. (Applause.)

To make our economy stronger and more dynamic, we must prepare a rising

generation to fill the jobs of the 21st century. Under the No Child Left Behind

Act, standards are higher, test scores are on the rise, and we're closing the

achievement gap for minority students. Now we must demand better results from

our high schools so every high school diploma is a ticket to success.

We will help an additional 200,000 workers to get training for a better career

by reforming our job training system and strengthening America's community

colleges. And we will make it easier for Americans to afford a college education

by increasing the size of Pell grants. (Applause.)

To make our economy stronger and more competitive, America must reward, not

punish, the efforts and dreams of entrepreneurs. Small business is the path of

advancement, especially for women and minorities. So we must free small

businesses from needless regulation and protection honest job creators from junk

lawsuits. (Applause.)

Justice is distorted and our economy is held back by irresponsible class actions

and frivolous asbestos claims, and I urge Congress to pass legal reforms this

year. (Applause.)

To make our economy stronger and more productive, we must make health care more

affordable and give families greater access to good coverage -- (applause) --

and more control over their health decisions. (Applause.)

I -- I ask Congress to move forward on a comprehensive health care agenda with

tax credits to help low-income workers buy insurance, a community health center

in every poor country, improved information technology to prevent medical error

and needless costs, association health plans for small business and their

employees -- (cheers, applause) -- expanded health savings accounts -- (cheers,

applause) -- and medical liability reform that will reduce health care costs and

make sure patients have the doctors and care they need. (Cheers, applause.)

To keep our economy growing, we also need reliable supplies of affordable,

environmentally responsible energy. (Cheers, applause.)

Nearly four years ago, I submitted a comprehensive energy strategy that

encourages conservation, alternative sources, a modernized electricity grid, and

more production here at home, including safe, clean nuclear energy. (Applause.)

My Clear Skies legislation will cut power plant pollution and improve the health

of our citizens. (Applause.) And my budget provides strong funding for

leading-edge technology, from hydrogen- fueled cars to clean coal to renewable

sources such as ethanol. (Applause.) Four years of debate is enough! (Cheers.) I

urge Congress to pass legislation that makes America more secure and less

dependent on foreign energy. (Cheers, applause.)

All these proposals are essential to expand this economy and add new jobs, but

they are just the beginning of our duty. To build the prosperity of future

generations, we must update institutions that were created to meet the needs of

an earlier time.

Year after year, Americans are burdened by an archaic, incoherent federal tax

code. I've appointed a bipartisan panel to examine the tax code from top to

bottom. And when the recommendations are delivered, you and I will work together

to give this nation a tax code that is pro-growth, easy to understand and fair

to all. (Applause.)

America's immigration system is also outdated, unsuited to the needs of our

economy and to the values of our country. We should not be content with laws

that punish hardworking people who want only to provide for their families --

(scattered applause) -- and deny businesses willing workers and invite chaos at

our border. It is time for an immigration policy that permits temporary guest

workers to fill jobs Americans will not take, that rejects amnesty, that tells

us who is entering and leaving our country, and that closes the border to drug

dealers and terrorists. (Applause.)

One of America's most important institutions, a symbol of the trust between

generations, is also in need of wise and effective reform. Social Security was a

great moral success of the 20th century, and we must honor its great purposes in

this new century. (Applause.)

The system, however, on its current path, is headed toward bankruptcy, and so we

must join together to strengthen and save Social Security. (Cheers, applause.)

Today, more than 45 million Americans receive Social Security benefits, and

millions more are nearing retirement. And for them, the system is strong and

fiscally sound. I have a message for every American who is 55 or older: Do not

let anyone mislead you. For you, the Social Security system will not change in

any way. (Applause.)

For younger workers, the Social Security system has serious problems that will

grow worse with time.

Social Security was created decades ago, for a very different era. In those days

people didn't live as long, benefits were much lower than they are today, and a

half century ago, about 16 workers paid into the system for each person drawing

benefits. Our society has changed in ways the founders of Social Security could

not have foreseen. In today's world, people are living longer, and therefore

drawing benefits longer -- and those benefits are scheduled to rise dramatically

over the next few decades. (Scattered applause.) And instead of 16 workers

paying in for every beneficiary, right now it's only about three workers. And

over the next few decades, that number will fall to just two workers per

beneficiary. With each passing year, fewer workers are paying ever-higher

benefits to an ever-larger number of retirees.

So here is the result. Thirteen years from now, in 2018, Social Security will be

paying out more than it takes in. And every year afterward will bring a new

shortfall, bigger than the year before. For example, in the year 2027, the

government will somehow have to come up with an extra $200 billion to keep the

system afloat.

And by 2033, the annual shortfall would be more than $300 billion. By the year

2042, the entire system would be exhausted and bankrupt. (Noes are heard.) If

steps are not taken to avert that outcome, the only solutions would be

dramatically higher taxes, massive new borrowing, or sudden and severe cuts in

Social Security benefits or other government programs. (Noes are heard.)

I recognize that 2018 and 2042 may seem a long way off, but those dates aren't

so distant, as any parent will tell you. If you have a five-year-old, you're

already concerned about how you'll pay for college tuition 13 years down the

road. If you've got children in their 20s, as some of us do, the idea of Social

Security collapsing before they retire does not seem like a small matter. And it

should not be a small matter to the United States Congress. (Cheers, applause.)

You and I share a responsibility. We must pass reforms that solve the financial

problems of Social Security once and for all.

Fixing Social Security permanently will require an open, candid review of the

options. Some have suggested limiting benefits for wealthy retirees. Former

Congressman Tim Penny has raised the possibility of indexing benefits to prices

rather than wages. During the 1990s, my predecessor, President Clinton, spoke of

increasing the retirement age. Former Senator John Breaux suggested discouraging

early collection of Social Security benefits. The late Senator Daniel Patrick

Moynihan recommended changing the way benefits are calculated.

All these ideas are on the table. I know that none of these reforms would be

easy. But we have to move ahead with courage and honesty, because our children's

retirement security is more important than partisan politics. (Applause.)

I will work with members of Congress to find the most effective combination of

reforms. I will listen to anyone who has a good idea to offer. (Cheers,

applause.) We must, however, be guided by some basic principles. We must make

Social Security permanently sound, not leave that task for another day. We must

not jeopardize our economic strength by increasing payroll taxes. We must ensure

that lower- income Americans get the help they need to have dignity and peace of

mind in their retirement. We must guarantee that there is no change for those

now retired or nearing retirement. And we must take care that any changes in the

system are gradual, so younger workers have years to prepare and plan for their

future.

As we fix Social Security, we also have the responsibility to make the system a

better deal for younger workers, and the best way to reach that goal is through

voluntary personal retirement accounts. (Applause.)

Here's how the idea works. Right now, a set portion of the money you earn is

taken out of your paycheck to pay for the Social Security benefits of today's

retirees. If you are a younger worker, I believe you should be able to set aside

part of that money in your own retirement account, so you can build a nest egg

for your own future.

Here is why personal accounts are a better deal. Your money will grow, over

time, at a greater rate than anything the current system can deliver, and your

account will provide money for retirement over and above the check you will

receive from Social Security. In addition, you'll be able to pass along the

money that accumulates in your personal account, if you wish, to your children

and -- or grandchildren. And best of all, the money in the account is yours, and

the government can never take it away. (Cheers, applause.)

The goal here is greater security in retirement, so we will set careful

guidelines for personal accounts. We will make sure the money can only go into a

conservative mix of bonds and stock funds. We will make sure that your earnings

are not eaten up by hidden Wall Street fees. We will make sure there are good

options to protect your investments from sudden market swings on the eve of your

retirement.

We'll make sure a personal account cannot be emptied out all at once, but rather

paid out over time, as an addition to traditional Social Security benefits. And

we will make sure this plan is fiscally responsible, by starting personal

retirement accounts gradually, and raising the yearly limits on contributions

over time, eventually permitting all workers to set aside 4 percentage points of

their payroll taxes in their accounts.

Personal retirement accounts should be familiar to federal employees because you

already have something similar called the Thrift Savings Plan, which lets

workers deposit a portion of their paychecks into any of five different broadly

based investment funds. It's time to extend the same security, and choice, and

ownership to young Americans. (Cheers, applause.)

Our second great responsibility to our children and grandchildren is to honor

and to pass along the values that sustain a free society. So many of my

generation, after a long journey, have come home to family and faith and are

determined to bring up responsible, moral children. Government is not the source

of these values, but government should never undermine them.

Because marriage is a sacred institution and the foundation of society, it

should not be redefined by activist judges. For the good of families, children

and society, I support a constitutional amendment to protect the institution of

marriage. (Cheers, applause.)

Because a society is measured by how it treats the weak and vulnerable, we must

strive to build a culture of life.

Medical research can help us reach that goal by developing treatments and cures

that save lives and help people overcome disabilities, and I thank Congress for

doubling the funding of the National Institutes of Health. (Applause.)

To build a culture of life, we must also ensure that scientific advances always

serve human dignity, not take advantage of some lives for the benefit of others.

(Applause.) We should all be able to agree -- (applause) -- we should all be

able to agree on some clear standards. I will work with Congress to ensure that

human embryos are not created for experimentation or grown for body parts, and

that human life is never bought or sold as a commodity. (Applause.)

America will continue to lead the world in medical research that is ambitious,

aggressive and always ethical.

Because courts must always deliver impartial justice, judges have a duty to

faithfully interpret the law, not legislate from the bench. (Applause.) As

president, I have a constitutional responsibility to nominate men and women who

understand the role of courts in our democracy and are well qualified to serve

on the bench, and I have done so. (Applause.)

The Constitution also gives the Senate a responsibility: Every judicial nominee

deserves an up-or-down vote. (Cheers, applause.)

Because one of the deepest values of our country is compassion, we must never

turn away from any citizen who feels isolated from the opportunities of America.

Our government will continue to support faith-based and community groups that

bring hope to harsh places.

Now we need to focus on giving young people, especially young men in our cities,

better options than apathy, or gangs, or jail. Tonight I propose a three-year

initiative to help organizations keep young people out of gangs, and show young

men an ideal of manhood that respects women and rejects violence. (Applause.)

Taking on gang life will be one part of a broader outreach to at- risk youth

which involves parents and pastors, coaches and community leaders, in programs

ranging from literacy to sports. And I am proud that the leader of this

nationwide effort will be our First Lady, Laura Bush. (Cheers, applause.)

Because HIV/AIDS brings suffering and fear into so many lives, I ask you to

reauthorize the Ryan White Act to encourage prevention, and provide care and

treatment to the victims of that disease. (Applause.)

And as we update this important law, we must focus our efforts on fellow

citizens with the highest rates of new cases, African-American men and women.

(Applause.) Because one of the main sources of our national unity is our belief

in equal justice, we need to make sure Americans of all races and backgrounds

have confidence in the system that provides justice.

In America, we must make doubly sure no person is held to account for a crime he

or she did not commit, so we are dramatically expanding the use of DNA evidence

to prevent wrongful conviction. (Applause.) Soon I will send to Congress a

proposal to fund special training for defense counsel in capital cases because

people on trial for their lives must have competent lawyers by their side.

(Applause.)

Our third responsibility to future generations is to leave them an America that

is safe from danger and protected by peace. We will pass along to our children

all the freedoms we enjoy; and chief among them is freedom from fear.

In the three and a half years since September 11th, 2001, we've taken

unprecedented actions to protect Americans. We've created a new department of

government to defend our homeland, focused the FBI on preventing terrorism,

begun to reform our intelligence agencies, broken up terror cells across the

country, expanded research on defenses against biological and chemical attack,

improved border security, and trained more than a half million first responders.

Police and firefighters, air marshals, researchers and so many others are

working every day to make our homeland safer, and we thank them all. (Extended

applause.)

Our nation, working with allies and friends, has also confronted the enemy

abroad, with measures that are determined, successful and continuing. The al

Qaeda terror network that attacked our country still has leaders, but many of

its top commanders have been removed. There are still governments that sponsor

and harbor terrorists, but their number has declined. There are still regimes

seeking weapons of mass destruction, but no longer without attention and without

consequence. Our country is still the target of terrorists who want to kill many

and intimidate us all, and we will stay on the offensive against them until the

fight is won. (Cheers, applause.)

Pursuing our enemies is a vital commitment of the war on terror, and I thank the

Congress for providing our servicemen and -women with the resources they have

needed.

During this time of war, we must continue to support our military and give them

the tools for victory. (Applause.)

Other nations around the globe have stood with us. In Afghanistan, an

international force is helping provide security. In Iraq, 28 countries have

troops on the ground, the United Nations and the European Union provided

technical assistance for the elections, and NATO is leading a mission to help

train Iraqi officers.

We're cooperating with 60 governments in the Proliferation Security Initiative

to detect and stop the transit of dangerous materials. We're working closely

with governments in Asia to convince North Korea to abandon its nuclear

ambitions.

Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and nine other countries have captured or detained

al-Qaeda terrorists.

In the next four years, my administration will continue to build the coalitions

that will defeat the dangers of our time. (Applause.)

In the long term, the peace we seek will only be achieved by eliminating the

conditions that feed radicalism and ideologies of murder. If whole regions of

the world remain in despair and grow in hatred, they will be the recruiting

grounds for terror, and that terror will stalk America and other free nations

for decades. The only force powerful enough to stop the rise of tyranny and

terror, and replace hatred with hope, is the force of human freedom. (Cheers,

applause.)

Our enemies know this, and that is why the terrorist Zarqawi recently declared

war on what he called the "evil principle" of democracy. And we've declared our

own intention: America will stand with the allies of freedom to support

democratic movements in the Middle East and beyond, with the ultimate goal of

ending tyranny in our world. (Applause.)

The United States has no right, no desire and no intention to impose our form of

government on anyone else. That is one -- (applause) -- that is one of the main

differences between us and our enemies. They seek to impose and expand an empire

of oppression, in which a tiny group of brutal, self-appointed rulers control

every aspect of every life. Our aim is to build and preserve a community of free

and independent nations, with governments that answer to their citizens and

reflect their own cultures.

And because democracies respect their own people and their neighbors, the

advance of freedom will lead to peace. (Applause.)

That advance has great momentum in our time, shown by women voting in

Afghanistan and Palestinians choosing a new direction, and the people of Ukraine

asserting their democratic rights and electing a president. We are witnessing

landmark events in the history of liberty, and in the coming years, we will add

to that story. (Cheers, applause.)

The beginnings of reform and democracy in the Palestinian territories are now

showing the power of freedom to break old patterns of violence and failure.

Tomorrow morning, Secretary of State Rice departs on a trip that will take her

to Israel and the West Bank for meetings with Prime Minister Sharon and

President Abbas. She will discuss with them how we and our friends can help the

Palestinian people end terror and build the institutions of a peaceful,

independent democratic state.

To promote this democracy, I will ask Congress for $350 million to support

Palestinian political, economic, and security reforms. The goal of two

democratic states, Israel and Palestine, living side by side in peace is within

reach -- and America will help them achieve that goal. (Applause.)

To promote peace and stability in the broader Middle East, the United States

will work with our friends in the region to fight the common threat of terror,

while we encourage a higher standard of freedom. Hopeful reform is already

taking hold in an arc from Morocco to Jordan to Bahrain. The government of Saudi

Arabia can demonstrate its leadership in the region by expanding the role of its

people in determining their future. And the great and proud nation of Egypt,

which showed the way toward peace in the Middle East, can now show the way

toward democracy in the Middle East. (Applause.)

To promote peace in the broader Middle East, we must confront regimes that

continue to harbor terrorists and pursue weapons of mass murder. Syria still

allows its territory, and parts of Lebanon, to be used by terrorists who seek to

destroy every chance of peace in the region.

You have passed, and we are applying, the Syrian Accountability Act, and we

expect the Syrian government to end all support for terror and open the door to

freedom. (Applause.)

Today, Iran remains the world's primary state sponsor of terror, pursuing

nuclear weapons while depriving its people of the freedom they seek and deserve.

We are working with European allies to make clear to the Iranian regime that it

must give up its uranium enrichment program and any plutonium reprocessing and

end its support for terror. And to the Iranian people, I say tonight: As you

stand for your own liberty, America stands with you. (Cheers, applause.)

Our generational commitment to the advance of freedom, especially in the Middle

East, is now being tested and honored in Iraq. That country is a vital front in

the war on terror, which is why the terrorists have chosen to make a stand

there. Our men and women in uniform are fighting terrorists in Iraq so we do not

have to face them here at home. (Applause.)

The victory of freedom in Iraq will strengthen a new ally in the war on terror,

inspire democratic reformers from Damascus to Tehran, bring more hope and

progress to a troubled region, and thereby lift a terrible threat from the lives

of our children and grandchildren.

We will succeed because the Iraqi people value their own liberty -- as they

showed the world last Sunday. (Cheers, applause.) Across Iraq, often at great

risk, millions of citizens went to the polls and elected 275 men and women to

represent them in a new Transitional National Assembly. A young woman in Baghdad

told of waking to the sound of mortar fire on election day and wondering if it

might be too dangerous to vote.

She said, "Hearing those explosions, it occurred to me: the insurgents are weak,

they are afraid of democracy, they are losing. So I got my husband and I got my

parents, and we all came out and voted together."

Americans recognize that spirit of liberty, because we share it. In any nation,

casting your vote is an act of civic responsibility. For millions of Iraqis, it

was also an act of personal courage, and they have earned the respect of us all.

(Applause.)

One of Iraq's leading democracy and human rights advocates is Safia Taleb

al-Suhail. She says of her country, "We were occupied for 35 years by Saddam

Hussein. That was the real occupation. Thank you to the American people who paid

the cost, but most of all to the soldiers."

Eleven years ago, Safia's father was assassinated by Saddam's intelligence

service. Three days ago in Baghdad, Safia was finally able to vote for the

leaders of her country. And we are honored that she is with us tonight.

(Extended cheers and applause.)

The terrorists and insurgents are violently opposed to democracy, and will

continue to attack it. Yet the terrorists' most powerful myth is being

destroyed. The whole world is seeing that the car bombers and assassins are not

only fighting coalition forces, they are trying to destroy the hopes of Iraqis,

expressed in free elections. And the whole world now knows that a small group of

extremists will not overturn the will of the Iraqi people. (Cheers, applause.)

We will succeed in Iraq because Iraqis are determined to fight for their own

freedom and to write their own history. As Prime Minister Allawi said in his

speech to Congress last September, "Ordinary Iraqis are anxious" to "shoulder

all the security burdens of our country as quickly as possible." This is the

natural desire of an independent nation, and it also is the stated mission of

our coalition in Iraq.

The new political situation in Iraq opens a new phase of our work in that

country. At the recommendation of our commanders on the ground, and in

consultation with the Iraqi government, we will increasingly focus our efforts

on helping prepare more capable Iraqi security forces, forces with skilled

officers and an effective command structure.

As those forces become more self-reliant and take on greater security

responsibilities, America and its coalition partners will increasingly be in a

supporting role. In the end, Iraqis must be able to defend their own country --

and we will help that proud, new nation secure its liberty.

Recently, an Iraqi interpreter said to a reporter, "Tell America not to abandon

us." He and all Iraqis can be certain: While our military strategy is adapting

to circumstances, our commitment remains firm and unchanging. We are standing

for the freedom of our Iraqi friends, and freedom in Iraq will make America

safer for generations to come. (Cheers, applause.)

We will not set an artificial timetable for leaving Iraq because that would

embolden the terrorists and make them believe they can wait us out. We are in

Iraq to achieve a result: a country that is democratic, representative of all

its people, at peace with its neighbors, and able to defend itself.

And when that result is achieved, our men and women serving in Iraq will return

home with the honor they have earned. (Applause.)

Right now, Americans in uniform are serving at posts across the world, often

taking great risks, on my orders. We have given them training and equipment, and

they have given us an example of idealism and character that makes every

American proud. (Applause.) The volunteers of our military are unrelenting in

battle, unwavering in loyalty, unmatched in honor and decency, and every day

they are making our nation more secure.

Some of our servicemen and women have survived terrible injuries, and this

grateful nation will do everything we can to help them recover. (Applause.)

And we have said farewell to some very good men and women, who died for our

freedom and whose memory this nation will honor forever. One name we honor is

Marine Corps Sergeant Byron Norwood of Pflugerville, Texas, who was killed

during the assault on Fallujah. His mom, Janet, sent me a letter and told me how

much Byron loved being a Marine and how proud he was to be on the front line

against terror. She wrote, "When Byron was home the last time, I said that I

wanted to protect him, like I had since he was born. He just hugged me and said,

`You've done your job, Mom. Now it is my turn to protect you.'"

Ladies and gentlemen, with grateful hearts, we honor freedom's defenders and our

military families, represented here this evening by Sergeant Norwood's mom and

dad, Janet and Bill Norwood. (Extended applause and cheers.)

In these four years, Americans have seen the unfolding of large events. We have

known times of sorrow and hours of uncertainty and days of victory. In all this

history, even when we have disagreed, we have seen threads of purpose that unite

us. The attack on freedom in our world has reaffirmed our confidence in

freedom's power to change the world. We are all part of a great venture: to

extend the promise of freedom in our country, to renew the values that sustain

our liberty, and to spread the peace that freedom brings.

As Franklin Roosevelt once reminded Americans, "each age is a dream that is

dying, or one that is coming to birth." And we live in the country where the

biggest dreams are born. The abolition of slavery was only a dream, until it was

fulfilled.

The liberation of Europe from fascism was only a dream -- until it was achieved.

The fall of imperial communism was only a dream -- until one day it was

accomplished.

Our generation has dreams of its own, and we also go forward with confidence.

The road of Providence is uneven and unpredictable -- yet we know where it

leads: It leads to freedom.

Thank you, and may God bless America. (Cheers, applause.)

END.

President Bush's

State of the Union Address,

NYT,

February 2, 2005,

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/02/02/politics/02text-bush.html

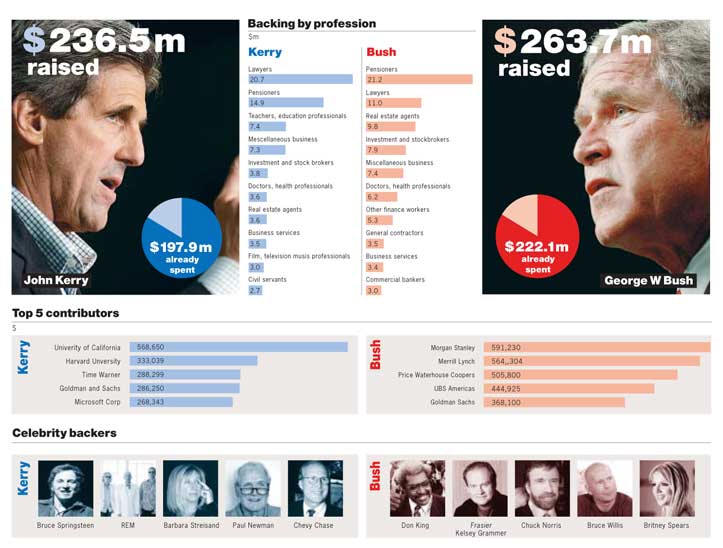

The Guardian p. 17

14.10.2004

http://www.guardian.co.uk/uselections2004/story/0,13918,1326870,00.html

All the president's men

Who's backing who in White House race

Bush backers

Bill Gates chairman, Microsoft

Steve Ballmer chief executive, Microsoft

Lee Scott chief executive Wal-Mart

Meg Whitman chief executive, eBay

Carly Fiorina chief executive Hewlett-Packard

Rupert Murdoch chairman and chief executive, News Corporation

Sumner Redstone chairman and chief executive, Viacom

Henry Kravis founding partner, Kohlberg, Kravis and Roberts

Stan O'Neal chairman and chief executive,

Merrill Lynch Sam Palmisano chairman

and chief executive, IBM

Michael Dell chairman, Dell

Craig Barrett chief executive, Intel

Terry Semel chairman and chief executive, Yahoo!

Philip Purcell chief executive, Morgan Stanley

Brian Roberts chairman and chief executive, Comcast

James Quigley chief executive, Deloitte and Touche

Charles Cawley chairman and chief executive MBNA

James Cayne chairman and chief executive, Bear Stearns

Hank Greenberg chairman and chief executive, American International Group

Thomas Hicks chairman and chief executive, Hicks Muse Tate & Furst

Kerry's heroes

Harvey Weinstein co-chairman Miramax

Edgar Bronfman Jr chairman, chief executive Warner Music

Donna Karan founder Donna Karan

Barry Diller chairman and chief executive, InterAtiveCorp

Peter Chernin chief operating officer, News Corporation

Robert Fisher chairman, Gap

Steve Jobs chairman, Apple

Warren Buffett chairman Berkshire Hathaway

George Soros chairman, Soros Fund Management

Eric Schmidt chief executive, Google

Charles Gifford chairman, Bank of America

Jim Clark Netscape founder

Jann Wenner chairman Wenner Media

August Busch IV president, Anheuser-Busch

Owsley Brown II chief executive, Brown Forman

Robert Hormats vice-chairman, Goldman Sachs

Thomas Lee president, Thomas Lee Company

Arthur Levitt former chairman of the securities and exchange commission

Jeffrey Katzenberg co-founder Dreamworks

Source : G,

27.10.2004,

http://digital.guardian.co.uk/guardian/2004/10/27/pages/brd21.shtml

The Guardian p. 12

27.10.2004

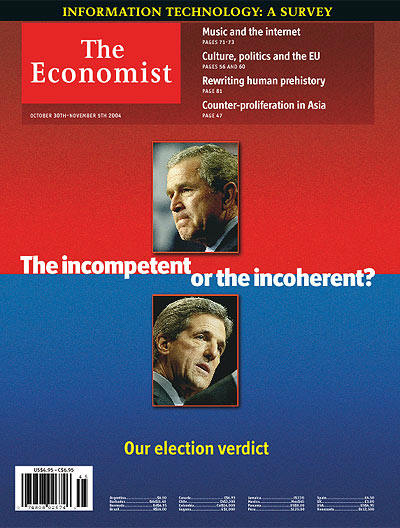

The triumph of the religious right

Nov 11th 2004 | WASHINGTON,DC

From The Economist print edition

Alamy The Economist

11.11.2004

It may look like that, but liberals should think again before despairing

IN A novel, set in the 1960s, by John Kennedy Toole, “A

Confederacy of Dunces”, the hero, Ignatius Reilly, goes to a gay party to drum

up political support.

In the centre of another knot [of guests] stood a lout in a

black leather jacket who was teaching judo holds, to the great delight of his

epicene students. “Oh, do teach me that,” someone near the wrestler screamed

after an elegant guest had been twisted into an obscene position and then thrown

to the floor to land with a crash of cuff-links and other, assorted jewelry.

“Good gracious,” Ignatius spluttered. “I can see that we're going to have a

great deal of trouble capturing the conservative rural red-neck Calvinist vote.”

Now, it seems, the conservative rural red-neck Calvinist vote

has captured America. A plurality of voters, emerging from poll booths, said

that the most important issue in the campaign had been “moral values”. It was

not, it seemed, Iraq or the economy. And eight out of ten of these moralists

voted for George Bush.

The thought that the anti-gay, anti-abortion Christian right had decided the

election dismayed left-wing Americans. Garry Wills in the New York Times

suggested that a fundamentalist Christian revival was in revolt against the

traditions of the Enlightenment, on which the country is based. “I hope we all

realise that, as of November 2nd, gay rights are officially dead. And that from

here on we are going to be led even closer to the guillotine,” said Larry

Kramer, a playwright and AIDS activist.

Secular Europeans wondered whether they and the Americans were now on different

planets. The week before the election, Rocco Buttiglione had been forced to

withdraw his nomination as a European Union commissioner because he had said

that homosexuality was a sin, and that marriage exists for children and the

protection of women. In America, he would probably have won Ohio.

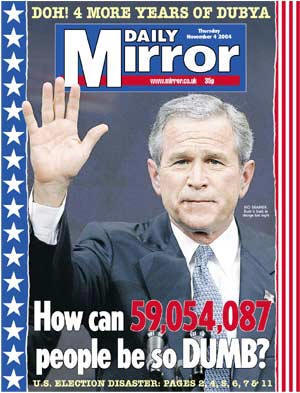

Der Spiegel, Germany's most popular newsweekly, put the statue of liberty on its

cover, blindfolded by an American flag. Britain's Daily Mirror asked, “How can

59,054,087 people be so DUMB?” And a contributor to Pravda, that bastion of

religious expertise, claimed that “the Christian fundamentalists of America are

the mirror image of the Taliban, both of which insult and deny their Gods.”

Hang on a moment. It is perfectly true that one of America's most overtly

religious presidents of recent times has been re-elected with an increased

majority. It is also true that 13 states this year passed state referendums

banning gay marriage—in most cases by larger majorities than Mr Bush managed—and

that a plurality of American voters put “moral values” at the top of their list

of concerns.

A moral majority? Not really

But they hardly formed a moral majority. Look at the figures:

the moralists' share of the electorate was only 22%, just two points more than

the share of those who cited the economy, and three points more than those who

nominated terrorism as the top priority. A few points difference (and the exit

polls are, after all, not entirely reliable) and everyone would have been saying

the election was about jobs or Iraq.

Moreover, that 22% share is much lower than it was in the two previous

presidential elections, in 2000 and 1996. Then, 35% and 40%, respectively, put

moral or ethical issues top, and a further 14% and 9% put abortion first, an

option that was not given in 2004. Thus, in those two elections, about half the

electorate said they voted on moral matters; this time, only a fifth did.

Of course, in those previous elections there was no war on terrorism, nor had

there just been a recession. So one could argue that it was remarkable that even

a fifth of voters were still concerned about moral matters when so many other

big issues were at stake. Maybe, but all that this means is that the war on

terrorism has not fundamentally altered, or made irrelevant, the cultural, moral

and religious divisions that have polarised America for so long.

A church-going land

It is also important to judge the religious-moral vote against

the background of American religiosity in general. America is traditionally much

more religious than any European country, with 80% of Americans saying they

believe in God and 60% agreeing that “religion plays an important part in my

life”.

What may be changing is that the country is getting a little more intense in its

religious beliefs. Also, and this could be more important, it is becoming more

willing to tolerate religious involvement in the public sphere. A study by the

Pew Research Centre reported that the number of those who “agree strongly” with

core items of Christian dogma rose substantially between 1965 and 2003. So did

the number of those who believe that there are clear guidelines about good and

evil, and that these guidelines apply regardless of circumstances. Gallup polls

in the 1960s found that over half of all Americans thought that churches should

not be involved in politics. Now, over half think that they can be.

At the same time, alongside all these signs of more intense religiosity, there

are indications of mellowing and tolerance. Support for interracial dating has

virtually doubled since 1987; discrimination against people with HIV/AIDS has

become socially unacceptable; tolerance for gays in public life has risen by

half—though gay marriage is still seen as a totally different matter. Americans

may be holding tenaciously to a strict view of personal morality, but they say

that they do not want to impose their views on others (abortion seems to be the

big exception).

The fact that there was a substantial religious-moral vote is not by itself

evidence of a political breakthrough by religious conservatives. Nor is it

necessarily a sign of growing intolerance. The real question is whether there

was anything new about what happened last week that might pave the way for such

things to happen in the future. The answer is yes, though not quite in the way

you might expect.

In 2000, 15m evangelical Protestants voted. They accounted for 23% of the

electorate, and 71% of them voted for Mr Bush. This time, estimates Luis Lugo,

the director of the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, they again accounted

for about 23% of the electorate—which means that evangelicals did not increase

their share of the vote. But overall turnout was much higher, and 78% of the

evangelicals who voted, voted for Mr Bush. That works out at roughly 3.5m extra

votes for him. Mr Bush's total vote rose by 9m (from 50.5m in 2000 to 59.5m), so

evangelical Protestants alone accounted for more than a third of his increased

vote.

In close association

Thus, the election revealed that though the evangelical share

of the electorate has not increased, evangelicals have become much more

important to the Republican Party. According to a study for the Pew Forum by

John Green of the University of Akron, Ohio, the proportion of evangelicals

calling themselves Republicans has risen from 48% to 56% over the past 12 years,

making them among the most solid segments of the party's base.

This close association between party and evangelicals took a lock-step forward

during the campaign. Mr Bush's chief policy adviser and campaign chairman held

weekly telephone conversations with prominent evangelical Christians, such as

Jim Dobson, the head of Focus on the Family, and the Rev Richard Land of the

Southern Baptist Convention. Ralph Reed, formerly the executive director of the

Christian Coalition, became the campaign's regional co-ordinator for the

south-east—a move that encapsulates the integration of evangelical voters into

the party.

Hitherto, evangelical Protestants have been the objects of Republican outreach.

This time, they took the initiative themselves, asking for and distributing

voter registration cards and collecting the signatures required to put

anti-gay-marriage initiatives on the ballot. As the church organisers tell it,

the Republican Party was left playing catch-up.

A leaderless lot

The campaign also revealed how decentralised the evangelical

movement is. There are respected figures, of course, such as Mr Dobson, and

there are self-appointed prophets, such as Pat Robertson. But these people have

no official institutional standing, and only limited moral authority. The

evangelical involvement in politics was largely the product of grass-roots

organising and bottom-up effort. As we will see, this could have implications

for how much of their agenda is adopted in practice.

Remember, too, that the religious right and religious America are far from being

the same things; Mr Bush's moral majority depended on the votes of other

religious groups as well. Catholics, with 27% of voters, are more numerous than

evangelicals, and, unusually this year, the Republican candidate won a majority

of the Catholic vote (52% against 47%).

Though Mr Bush did especially well among white Catholics and those who attended

Mass regularly, he also increased his share of the Hispanic Catholic vote from

31% in 2000 to 42%. This alone accounts for the inroads he made into the

Hispanic vote, which has traditionally gone to Democrats by two to one. In all,

calculates Mr Lugo, 3.5m more Catholics voted for Mr Bush in 2004 than in 2000.

Thus, they were as important to his increased majority as evangelical

Protestants were.

The Economist

11.11.2004

This points to another new development. The election seems to

have consolidated the tendency of the most observant members of any church,

regardless of denomination, to vote Republican. During the campaign, a debate

erupted among Catholics over John Kerry's support for abortion rights. Orthodox

Catholics condemned his stance and one bishop even said he would deny the

candidate communion (as a Catholic himself, Mr Kerry opposed abortion, but did

not back anti-abortion laws). “Progressive” Catholics defended him, but the

election returns suggest that the orthodox position won out. That seems

characteristic of all denominations.

Mr Green subdivides each church into three groups (see table): traditionalists,

centrists and modernists, according to the intensity of belief. Traditionalists

believe in church doctrine and go to church once a week or more; modernists are

more relaxed. The three most Republican groups are traditionalist evangelicals,

traditionalist mainline Protestants and traditionalist Catholics. Modernists

lean towards the Democrats.

The election returns are consistent with this: people who go to church once a

week or more voted for Mr Bush by nearly two to one. This seems to supersede the

historical pattern, whereby evangelicals have tended to vote Republican,

Catholics Democratic and mainline Protestants (Lutherans, Methodists) have split

their vote.

The implication of these findings is that Mr Bush's moral majority is not, as is

often thought, just a bunch of right-wing evangelical Christians. Rather, it

consists of traditionalist and observant church-goers of every kind: Catholic

and mainline Protestant, as well as evangelicals, Mormons, Sign Followers, you

name it. Meanwhile, modernist evangelicals (yes, there are a few) tend to be

Democratic.

What happens next?

The big question for the next four years is what the

traditionalist constituency will demand of Mr Bush, and whether he will give it

what it wants.

Already, self-appointed church leaders are queuing up to claim credit for the

election victory and to insist on a bigger role in government. Mr Dobson told

ABC's “This Week” programme that “this president has two years, or more broadly

the Republican Party has two years, to implement those policies, or certainly

four, or I believe they'll pay a price in the next election.”

There is no shortage of politicians, holding some of the more extreme views of

the Christian right, who can be counted on to back the church leaders to the

hilt. Tom Coburn, the new senator from Oklahoma, has called not just for

outlawing abortion but for the death penalty for doctors who break such a law.

Another new senator, John Thune of South Dakota, is a creationist. A third, Jim

DeMint of South Carolina, has said single mothers should not teach in schools.

Evangelicals are already bringing test cases to ensure that school textbooks

include creationism and censor gay marriage.

Such local efforts have been common for years. What now matter

are the country-wide political views of Mr Bush's traditionalist constituency.

On the face of it, these Bush-leaning traditionalists come from central casting:

conservative politically, rigid religiously, willing to mix up church and state.

According to Mr Green's survey, nine out of ten of them say that the president

should have strong religious beliefs, and two-thirds of them also believe that

religious groups should involve themselves in politics.

Yet the picture is more complicated than this makes it sound. For instance, in

all the religious groups substantial majorities agree that the disadvantaged

need government help “to obtain their rightful place in America”.

All favour increasing anti-poverty programmes, even if it means higher taxes.

All support stricter environmental regulation. Large majorities say that America

should give a high priority to fighting HIV/AIDS abroad. Religious conservatives

have been among the strongest backers of intervening in Sudan and increasing

AIDS spending in poor countries. If the Bush administration wanted to, it could

find plenty of religious support for increased welfare programmes, tougher

environmental standards and more foreign aid.

The differences between the religious groups are equally striking. The

Protestant traditionalists favour less government spending. But all the

Catholics—traditionalist, mainline and modernist alike—favour more.

Traditionalist evangelicals are usually the odd men out. Fully 81% of them say

that religion is important to their political thinking—far more than any other

group. They are the only ones to rate cultural issues as more important than

economic or foreign-policy ones. They are the most opposed to abortion (though

52% say it should be legal in some circumstances) and the most opposed to gay

marriage (though 36% say they support gay rights). They also hold highly

distinctive foreign-policy views: seven in ten say America has a special role in

the world and two-thirds think America should support Israel in its conflict

with the Palestinians.

He need not be trapped

Will the new importance of the traditionalist evangelical vote

succeed in driving the president in the direction that many of these voters

want? Not necessarily. The variety of conservative religious opinion means that

Mr Bush need not be trapped by one important wing of his religious base, even if

he will certainly not want to neglect it.

For example, the evangelicals' Zionist views are offset by the more even-handed

positions of Catholics and mainline Protestants, implying that the president

could try to restart the Middle East peace process without risking the wrath of

his whole religious constituency. And because the evangelical churches are

decentralised, and somewhat leaderless at the national level, it will be hard

for any populist to mobilise them against a president they like and respect.

Attempts to ram conservative social policies into law look inevitable. They

include the federal amendment banning gay marriage, though this is an uphill

struggle that failed by 19 votes in the Senate last time round. Moreover, on the

eve of the election, Mr Bush came out in favour of civil unions, which more than

half the population, including many religious conservatives, favour. They also

include extending a ban on “partial-birth abortion” to cover all third-trimester

abortions, and, most important, appointing conservative judges to any Supreme

Court vacancies.

This week there was a sign of what may be to come when Republicans threatened to

strip Senator Arlen Specter of the chairmanship of the committee that oversees

Supreme Court nominations after he said that staunch opponents of abortion were

unlikely to be confirmed.

For opponents of Mr Bush, and also for many socially liberal Republicans, the

election results and the trumpeted evangelical ambitions point to a big

reversal: the victory of aggressive social conservatism over the

small-government tradition in which morality is not legislated. It could,

indeed, turn out to be something like this, but it need not. The wide variety of

different opinions held by Mr Bush's religious supporters give the president,

and his new administration, a lot of leeway, if they choose to look for it.

Source : The

Economist, 11.11.2004,

© 2004 The Economist Newspaper and The Economist Group,

http://www.economist.com/world/na/PrinterFriendly.cfm?Story_ID=3375543

Voting under the Cross - E AP - 11.11.2004

http://www.economist.com/world/na/

PrinterFriendly.cfm?Story_ID=3375543

Elections américaines :

Patrick Kenney,

professeur de sciences politiques à l'université d'Arizona:

«Le Parti républicain a poussé les chrétiens évangéliques à voter»

Vendredi 5 novembre 2004.

Libération

Par Pascal RICHE.

Patrick Kenney, professeur de sciences politiques à

l'université d'Arizona, à Tempe, explique pourquoi la politique de la seconde

administration Bush va accentuer et radicaliser la «révolution conservatrice»

qui l'a porté au pouvoir.

La présidence Bush va-t-elle changer ce pays en profondeur

?

Il va pousser son programme le plus loin possible. Il ne va pas se rapprocher du

centre. L'argent qui l'a financé, les électeurs qui l'ont soutenu, les gens qui

l'entourent, tous soutiennent un programme bien spécifique. Et il a désormais

derrière lui une majorité plus confortable à la Chambre et au Sénat. Les

conditions pour qu'on assiste à un changement de ce pays n'ont donc jamais été

aussi fortes depuis la présidence de Ronald Reagan au début des années 1980. Je

ne pense pas qu'il va réussir à révolutionner les retraites, ni faire passer son

amendement interdisant le mariage gay. Ni envahir un autre pays. Mais il va

continuer sur le registre qui est au coeur du projet républicain : baisse des

impôts, réduction du rôle du gouvernement, déréglementation. S'il en a

l'occasion, il nommera un juge à la Cour suprême, et il choisira sans doute un

idéologue.

Bush a-t-il été réélu parce que les Américains se sentent

en guerre, ou sa victoire marque- t-elle la dérive à droite de ce pays, engagée

par Ronald Reagan ?

C'est une question encore difficile à trancher. Il est clair que les Américains

n'ont pas voulu changer de Président dans un contexte de guerre. Des sondages

sortis des urnes montrent aussi qu'une personne sur cinq a motivé son vote par

l'attachement à des «valeurs morales». Mais qu'entendent-ils par valeurs

morales, on ne le sait pas bien. Sont-ce des valeurs traditionnelles qui

tournent autour des thèmes de campagne comme la recherche sur les cellules

souches, le mariage homosexuel, ou la définition que donnent les électeurs

est-elle plus large ? En fait, on ne sait pas.

L'Amérique ne vous semble-elle pas solidement ancrée à

droite ?

La principale leçon de ce scrutin, c'est que le Parti démocrate dans ce pays est

un parti minoritaire. Il n'a jamais remporté la majorité des voix depuis Jimmy

Carter en 1984 (et Clinton a été élu en 1992 par une minorité, grâce à la

candidature du «troisième candidat» Ross Perot, ndlr). Les démocrates ne

représentent qu'entre 45 et 49 % de l'électorat. Pourquoi ne parviennent-ils pas

à étendre leur base, c'est une question très difficile. Est-ce un problème de

rapport culturel ? C'est une hypothèse. Regardez la carte. Les Etats de la

plaine sont traditionnellement républicains : petites villes, populations

rurales. Ils sont plus conservateurs que la moyenne sur toute une série de

sujets : la culture, la morale, la religion. Le Sud est similaire, mais il faut

y ajouter la composante raciale. Si vous mettez bout à bout tous ces Etats de la

plaine et du Sud, ils tiennent une énorme place sur la carte. Le Parti démocrate

part avec un très gros handicap. Ajoutez à cela le contexte de guerre, une

économie qui n'est pas si mauvaise (l'inflation et les taux d'intérêt sont bas,

le PIB croît...), et vous mesurez combien il était difficile de faire tomber ce

Président.

La religion est-elle l'explication principale du fossé entre les deux

Amériques ? Les pratiquants votent Bush, les autres votent Kerry...

On constate cela depuis environ vingt-cinq ans. Ce qui est clair, c'est que Bush

s'en sert plus ouvertement, et a renforcé l'idée que le Parti républicain est

plus conservateur sur toute une série de problèmes, renforçant l'adhésion à ce

parti des pratiquants réguliers.

Mais l'Amérique n'est pas de plus en plus religieuse. Ce qui a changé, entre

2000 et 2004, c'est l'effort du Parti républicain pour pousser les chrétiens

évangéliques à aller voter. Il semble que cette stratégie, conçue par Karl Rove

(le stratège de Bush, ndlr), ait très bien fonctionné. La plupart de ces voix

ont été exprimées dans des Etats qui de toute façon auraient voté républicain.

Cela n'a donc pas énormément aidé Bush à gagner des grands électeurs et la

Maison Blanche, mais cela lui a permis d'afficher une confortable majorité du

vote national et de gagner avec 3,5 millions de voix d'avance.

Source : Libération, 5.11.2004,

http://www.liberation.com/page.php?Article=251610

November 15, 2004 Vol. 164 No. 20 Election Special

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/0,9263,1101041115,00.html

President Bush

Thanks Americans in Wednesday Acceptance Speech

Remarks by the President in Acceptance Speech

The Ronald Reagan Building

Washington, D.C.

3:08 P.M. EST

THE PRESIDENT: Thank you all. Thank you all for coming. We had

a long night -- and a great night. (Applause.) The voters turned out in record

numbers and delivered an historic victory. (Applause.)

Earlier today, Senator Kerry called with his congratulations. We had a really

good phone call, he was very gracious. Senator Kerry waged a spirited campaign,

and he and his supporters can be proud of their efforts. (Applause.) Laura and I

wish Senator Kerry and Teresa and their whole family all our best wishes.

America has spoken, and I'm humbled by the trust and the confidence of my fellow

citizens. With that trust comes a duty to serve all Americans, and I will do my

best to fulfill that duty every day as your President. (Applause.)

There are many people to thank, and my family comes first. (Applause.) Laura is

the love of my life. (Applause.) I'm glad you love her, too. (Laughter.) I want

to thank our daughters, who joined their dad for his last campaign. (Applause.)

I appreciate the hard work of my sister and my brothers. I especially want to

thank my parents for their loving support. (Applause.)

I'm grateful to the Vice President and Lynne and their daughters, who have

worked so hard and been such a vital part of our team. (Applause.) The Vice

President serves America with wisdom and honor, and I'm proud to serve beside

him. (Applause.)

I want to thank my superb campaign team. I want to thank you all for your hard

work. (Applause.) I was impressed every day by how hard and how skillful our

team was. I want to thank Marc -- Chairman Marc Racicot and -- (applause) -- the

Campaign Manager, Ken Mehlman. (Applause.) And the architect, Karl Rove.

(Applause.) I want to thank Ed Gillespie for leading our Party so well.

(Applause.)

I want to thank the thousands of our supporters across our country. I want to

thank you for your hugs on the rope lines; I want to thank you for your prayers

on the rope lines; I want to thank you for your kind words on the rope lines. I

want to thank you for everything you did to make the calls and to put up the

signs, to talk to your neighbors and to get out the vote. (Applause.) And

because you did the incredible work, we are celebrating today. (Applause.)

There's an old saying, "Do not pray for tasks equal to your powers; pray for

powers equal to your tasks." In four historic years, America has been given

great tasks, and faced them with strength and courage. Our people have restored

the vigor of this economy, and shown resolve and patience in a new kind of war.

Our military has brought justice to the enemy, and honor to America. (Applause.)

Our nation has defended itself, and served the freedom of all mankind. I'm proud

to lead such an amazing country, and I'm proud to lead it forward. (Applause.)

Because we have done the hard work, we are entering a season of hope. We'll

continue our economic progress. We'll reform our outdated tax code. We'll

strengthen the Social Security for the next generation. We'll make public

schools all they can be. And we will uphold our deepest values of family and

faith.

We will help the emerging democracies of Iraq and Afghanistan -- (applause) --

so they can grow in strength and defend their freedom. And then our servicemen

and women will come home with the honor they have earned. (Applause.) With good

allies at our side, we will fight this war on terror with every resource of our

national power so our children can live in freedom and in peace. (Applause.)

Reaching these goals will require the broad support of Americans. So today I

want to speak to every person who voted for my opponent: To make this nation

stronger and better I will need your support, and I will work to earn it. I will

do all I can do to deserve your trust. A new term is a new opportunity to reach

out to the whole nation. We have one country, one Constitution and one future

that binds us. And when we come together and work together, there is no limit to

the greatness of America. (Applause.)

Let me close with a word to the people of the state of Texas. (Applause.) We

have known each other the longest, and you started me on this journey. On the

open plains of Texas, I first learned the character of our country: sturdy and

honest, and as hopeful as the break of day. I will always be grateful to the

good people of my state. And whatever the road that lies ahead, that road will

take me home.

The campaign has ended, and the United States of America goes forward with

confidence and faith. I see a great day coming for our country and I am eager

for the work ahead. God bless you, and may God bless America. (Applause.)

END 3:18 P.M. EST

Source : White House,

3.11.2004,

http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2004/11/20041103-3.html

The Economist

Infographie de l'article Back to basics, 4.11.2004

http://www.economist.com/agenda/displayStory.cfm?story_id=3360235

R. J. Matson Cagle

4.11.2004

http://www.rjmatson.com/personal.htm

State by state: how Americans cast their votes

The Independent

04 November 2004

ALABAMA

George Bush

62.5%; John Kerry 36.8%

House: Rep

4, Dem 2

Senate: Rep

ALASKA

Bush 61.9%;

Kerry 35%

House: Rep

1

Senate: Rep

ARIZONA

Bush 55.1%;

Kerry 44.3%

House: Rep

6, Dem 2

Senate: Rep

ARKANSAS

Bush 54.6%;

Kerry 44.3%

House: Rep

1, Dem 2

Senate: Dem

CALIFORNIA

Bush 44.3%;

Kerry 54.6%

House: Rep

21, Dem 32

Senate: Dem

COLORADO

Bush 52.8%;

Kerry 46%

House: Rep

4, Dem 3

Senate: Dem

CONNECTICUT

Bush 44%;

Kerry 54.3%

House: Rep

3, Dem 2

Senate: Dem

DELAWARE

Bush 45.8%;

Kerry 53.3%

House: Rep

1

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

Bush 9.3%;

Kerry 89.5%

FLORIDA

Bush 52.2%;

Kerry 47%

House: Rep

13, Dem 2

Senate: Rep

GEORGIA

Bush 58.6%;

Kerry 40.9%

House: Rep

3, Dem 4

Senate: Rep

HAWAII

Bush 45.3%;

Kerry 54%

House: Dem

2

Senate: Dem

IDAHO

Bush 68.5%;

Kerry 30.4%

House: Rep

2

Senate: Rep

ILLINOIS

Bush 44.8%;

Kerry 54.6%

House: Rep

9, Dem 10

Senate: Dem

INDIANA

Bush 60.1%;

Kerry 39.2%

House: Rep

7, Dem 2

Senate: Rep

IOWA

(undecided)

Bush 50.1%;

Kerry 49.2%

House: Rep

4, Dem 1

Senate: Rep

KANSAS

Bush 62.2%;

Kerry 36.5%

House: Rep

3, Dem 1

Senate: Rep

KENTUCKY

Bush 59.6%;

Kerry 39.7%

House: Rep

4, Dem 1

Senate: Rep

LOUISIANA

Bush 56.8%;

Kerry 42.2%

House: Rep

5, Dem 1

Senate: Rep

MAINE

Bush 45%;

Kerry 53%

House: Dem

2

MARYLAND

Bush 43.2%;

Kerry 55.8%

House: Rep

2, Dem 6

Senate: Dem

MASSACHUSETTS

Bush 37%;

Kerry 62.1%

House: Dem

6

MICHIGAN

Bush 47.8%;

Kerry 51.2%

House: Rep

9, Dem 6

MINNESOTA

Bush 47.6%;

Kerry 51.1%

House: Rep

4, Dem 4

MISSISSIPPI

Bush 59.7%;

Kerry 39.5%

House: Rep

2, Dem 2

MISSOURI

Bush 53.4%;

Kerry 46.1%

House: Rep

5, Dem 4

Senate: Rep

MONTANA

Bush 59.1%;

Kerry 38.5%

House: Rep

1

NEBRASKA

Bush 66.6%;

Kerry 32.1%

House: Rep

3

NEVADA

Bush 50.5%;

Kerry 47.9%

House: Rep

2, Dem 1

Senate: Dem

NEW HAMPSHIRE

Bush 49%;

Kerry 50.3%

House: Rep

2

Senate: Rep

NEW JERSEY

Bush 46.5%;

Kerry 52.7%

House: Rep

6, Dem 7

NEW MEXICO

(Still undecided)

Bush 50.3%;

Kerry 48.6%

House: Rep

2, Dem 1

NEW YORK

Bush 40.5%;

Kerry 57.8%

House: Rep

10, Dem 19

Senate: Dem

NORTH CAROLINA

Bush 56.3%;

Kerry 43.3%

House: Rep

6, Dem 6

Senate: Rep

NORTH DAKOTA

Bush 62.9%;

Kerry 35.5%

House: Dem

1

Senate: Dem

OHIO (Still

undecided)

Bush 51%;

Kerry 48.5%

House: Rep

12, Dem 6

Senate: Rep

[ COLUMBUS, Ohio (Reuters) -

President Bush carried Ohio by 118,775 votes in last month's election,

17,708 fewer than reported at the time but not enough to change the outcome in

the crucial state,

officials said on Monday. John Kerry conceded to Bush the day after the Nov. 2

balloting,

saying an analysis showed he could not win Ohio,

which provided Bush the final margin of victory and a second term.

Ohio Secretary of State J. Kenneth Blackwell certified the outcome on Monday,

based on a county-by-county canvass done under state law in the days since the

election.

It showed Bush with 2,858,727 or 50.82 percent

to 2,739,952, or 48.7 percent, for the Democrat Kerry.

Final Ohio Vote Tally Shows

Smaller Margin for Bush, R, Mon Dec 6, 2004 05:06 PM ET

http://www.reuters.com/newsArticle.jhtml;jsessionid=

GU1UX01HEWXP0CRBAEOCFFA?type=domesticNews&storyID=7008777

]

OKLAHOMA

Bush 65.6%;

Kerry 34.4%

House: Rep

3, Dem 1

Senate: Rep

OREGON

Bush 47.1%;

Kerry 51.9%

House: Rep

1, Dem 4

Senate: Dem

PENNSYLVANIA

Bush 48.6%;

Kerry 50.8%

House: Rep

14, Dem 5

Senate: Rep

RHODE ISLAND

Bush 38.9%;

Kerry 59.6%

House: Dem

2

SOUTH CAROLINA

Bush 58%;

Kerry 40.9%

House: Rep

3, Dem 2

Senate: Rep

SOUTH DAKOTA

Bush 59.9%;

Kerry 38.4%

House: Dem

1

Senate: Rep

TENNESSEE

Bush 56.8%;

Kerry 42.5%

House: Rep

3, Dem 5

Senate: Rep

TEXAS

Bush 61.2%;

Kerry 38.3%

House: Rep

20, Dem 12

UTAH

Bush 70.9%;

Kerry 26.5%

House: Rep

2, Dem 1

Senate: Rep

VERMONT

Bush 38.9%;

Kerry 59.1%

House: Ind

1

Senate: Dem

VIRGINIA

Bush 54%;

Kerry 45.4%

House: Rep

7, Dem 4

WASHINGTON

Bush 46.2%;

Kerry 52.4%

House: Rep

3, Dem 6

Senate: Dem

WEST VIRGINIA

Bush 56.1%;

Kerry 43.2%

House: Rep

1, Dem 2

WISCONSIN

Bush 49.4%;

Kerry 49.8%

House: Rep

4, Dem 4

Senate: Dem

WYOMING

Bush 69%;

Kerry 29.1%

House: Rep

1

Source : The Independent, 4.11.2004,

http://news.independent.co.uk/world/americas/story.jsp?story=579247

The Economist

Chart

Back to basics

4.11.2004

http://www.economist.com/agenda/displayStory.cfm?story_id=3360235

La priorité accordée aux "valeurs morales"

a profité à George Bush

En mobilisant sa base tout en gagnant les

indécis, le camp républicain a drainé les suffrages d'une opinion qui a placé

l'avortement ou le mariage gay en tête de ses préoccupations. L'élection indique

que les Etats-Unis sont plus conservateurs que ne le pensaient les observateurs.

New York de notre correspondant

La mobilisation de l'électorat américain, avec plus de 120 millions de votants

et une participation à son plus haut niveau depuis 1968, laissaient augurer une

victoire démocrate. Il n'en a rien été. Au contraire, les républicains ont

creusé l'écart, à la surprise de la plupart des observateurs. Ils ont réussi

tout à la fois à rameuter leur base et à convaincre de nombreux indécis. Le

scrutin s'est finalement résumé à un référendum sur quatre sujets : les

"valeurs", le terrorisme, l'économie et la guerre en Irak.

Selon les sondages réalisés à la sortie des urnes, le thème cité en premier par

plus de 22 % des personnes interrogées était celui des "valeurs morales", devant

l'économie (20 %), le terrorisme (19 %) et l'Irak (15 %). Les électeurs

préoccupés par "la défense des valeurs" ont déclaré avoir voté à 79 % pour le

président sortant et ceux qui ont fait du terrorisme leur principale

préoccupation ont choisi presque dans la même proportion George Bush.

En revanche, John Kerry a recueilli les suffrages de 80 % des Américains

inquiets de la situation économique et de l'emploi et de 75 % de ceux qui ont

mis l'Irak en tête de leur liste.

Au lendemain de l'élection présidentielle, les Etats-Unis apparaissent comme un

pays bien plus conservateur que les experts politiques et les médias, y compris

américains, l'imaginaient. Ainsi, même dans l'Ohio, un Etat où ont été perdus un

quart des emplois industriels du pays depuis quatre ans et qui aurait,

logiquement, dû revenir à John Kerry, les sondages montrent que près de 25 % des

électeurs se sont déterminés en fonction des "valeurs morales".

UN PAYS EN GUERRE

George Bush a même fait oublier le précepte de Richard Nixon selon lequel, pour

accéder à la Maison Blanche, un républicain doit d'abord séduire l'aile

conservatrice de son parti et ensuite se tourner vers les centristes. "Bush n'a

même pas cherché à convaincre au centre. Il a eu pour seul souci et pour seule

stratégie de satisfaire et de donner de l'énergie à sa base", explique John

Zogby, spécialiste des sondages. Karl Rove, le stratège républicain, a réussi à

faire voter en faveur de George Bush les 4 millions de chrétiens évangélistes

qui lui avaient, selon lui, fait défaut en 2000. Le président n'a cessé de

donner des gages sur les questions éthiques comme l'avortement, le mariage

homosexuel ou la recherche sur les cellules souches embryonnaires.

Mais, dans le même temps, il a aussi réussi à convaincre les indépendants qu'un

changement à la Maison Blanche était trop risqué pour un pays en guerre et

menacé. "La performance du tandem Bush-Cheney prouve qu'il n'y a, en fait, pas

de contradiction entre chercher à satisfaire notre base et convaincre les

électeurs indécis", souligne Ralph Reed, responsable de la campagne républicaine

dans le Sud-Est. "A qui pouvez-vous faire confiance ?", n'a cessé de marteler

George Bush lors de ses meetings. La propagande républicaine a présenté pendant

des mois John Kerry comme "faible" en matière de sécurité et de défense,

incohérent face au terrorisme et incapable de devenir "commandant en chef". Et

jamais, dans l'histoire du pays, un président sortant n'a perdu une élection

pour un second mandat quand le pays était en guerre. Toujours d'après les

sondages réalisés à la sortie des bureaux de vote, George Bush a amélioré ses

positions par rapport à l'élection de 2000 auprès de la quasi-totalité des

catégories d'électeurs. Il a recueilli 47 % du vote des femmes, soit 4 % de plus

qu'il y a quatre ans. Il a perdu à nouveau la majorité du vote latino, mais en a

tout de même obtenu 42 %, pour 55 % à John Kerry, soit 7 % de plus qu'en 2000.

Cela explique sans doute les gains républicains dans des Etats comme la Floride

et le Nouveau-Mexique.

AMPLEUR INATTENDUE

Le président sortant a récolté 43 % du vote urbain, soit 8 % de plus que contre

Al Gore. Les républicains ont gagné également 4 % auprès des catholiques, qui

avaient soutenu - à une faible majorité - Al Gore. Cette fois, les deux

candidats, dont John Kerry, qui est catholique, se partagent à égalité cet

électorat. George Bush a également amélioré son score auprès de la communauté

juive, en gagnant 5 points, à 24 %, contre 76 % pour le candidat démocrate.

Enfin, le président a réalisé une performance exceptionnelle auprès des

électeurs se rendant à l'église au moins une fois par semaine : il a, dans cette

catégorie, devancé son adversaire de 21 points. Cela lui a permis d'être

particulièrement fort dans la région des Appalaches, les Etats de la "Bible

Belt" (Ceinture de la Bible) comme la Virginie-Occidentale, le Kentucky et

l'Arkansas, auparavant acquis au Parti démocrate. Bill Clinton l'avait emporté

dans ces trois Etats en 1992 et 1996. George Bush a gagné le Kentucky avec 20 %

d'avance, la Virginie-Occidentale avec 11 % et l'Arkansas avec 9 %.

Le président remporte ainsi une victoire d'une ampleur inattendue avec,

paradoxalement, une image personnelle auprès des Américains qui n'est pas

exceptionnelle. Une majorité, 57 % contre 38 %, considère qu'il accorde plus

d'attention aux intérêts des grandes entreprises qu'aux citoyens "ordinaires".

Plus étonnant encore, 52 % des personnes interrogées après avoir voté se

déclaraient "en colère" ou "mécontentes" du bilan de George Bush à la Maison

Blanche.

Source : Eric Leser, Le Monde,

5.11.2004,

http://www.lemonde.fr/web/article/0,1-0@2-3222,36-385721,0.html

4.11.2004

55 % des hommes ont voté pour M. Bush

Le vote Bush est dominé par les hommes et les électeurs de race blanche. Selon

le sondage CNN de sortie des urnes, 55 % des hommes ont voté pour le président

sortant et 48 % des femmes. Le vote des Blancs - qui représente 77 % du total -

est de 58 % en faveur de M. Bush, contre 41 % à John Kerry. Dans les autres

groupes, M. Bush a obtenu 11 % du vote afro-américain (11 % du total) ; 44 % du

vote latino-américain (8 % du total) ; 44 % du vote asiatique (2 % du total).

Par revenus, on a voté de plus en plus pour George Bush en fonction de sa

fortune. Ont voté Bush 44 % de ceux qui gagnent moins de 50 000 dollars par an

(et 36 % de ceux qui gagnent moins de 15 000 dollars), mais 56 % de ceux qui

gagnent plus de 50 000 dollars (et 63 % de ceux qui gagnent plus de 200 000

dollars). Cela ne recoupe pas les diplômes : ceux qui n'ont pas de diplôme

d'études supérieures ont voté à 53 % pour M. Bush, les autres à 49 %.

Source : encadré de La

priorité accordée aux "valeurs morales"

a profité à George Bush,

Le Monde, 5.11.2004,

http://www.lemonde.fr/web/article/0,1-0@2-3222,36-385721,0.html

4.11.2004

Protestants évangéliques

et catholiques conservateurs unis dans le vote gagnant

La variable religieuse a eu un effet décisif. Le président

sortant aurait rallié 60 % des voix protestantes et 51 % de l'électorat

catholique.

Dans une Amérique ébranlée par le 11-Septembre, la peur du