|

History > 19th, 20th, early 21st century

>

South Africa

Timeline

in articles, pictures and podcasts

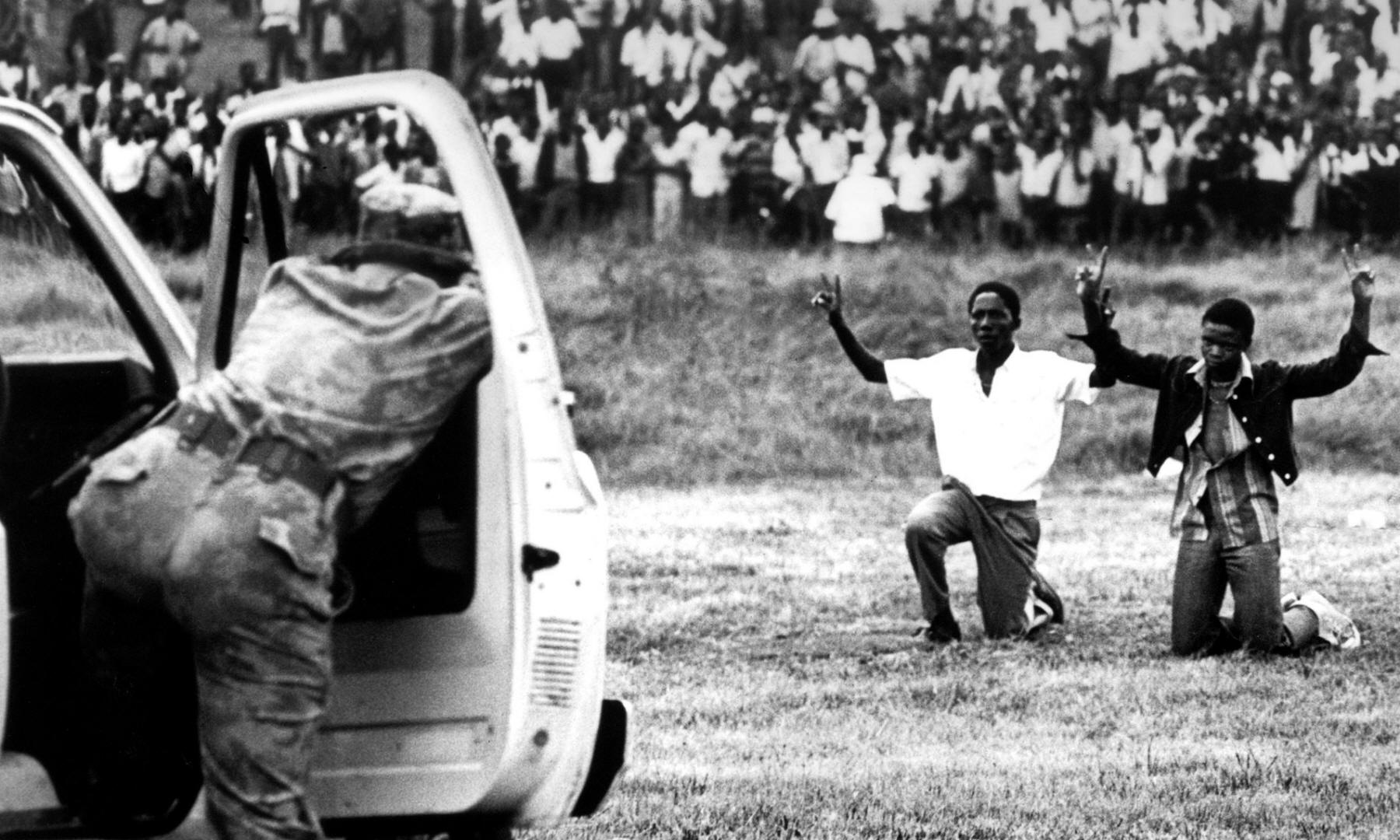

Soweto youths kneeling in front

of the police.

Photograph: Foto24/Getty Images

'My activism started then':

the

Soweto uprising remembered

G

Thursday 16 June 2016 07.00 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jun/16/

my-activism-started-then-the-soweto-uprising-remembered

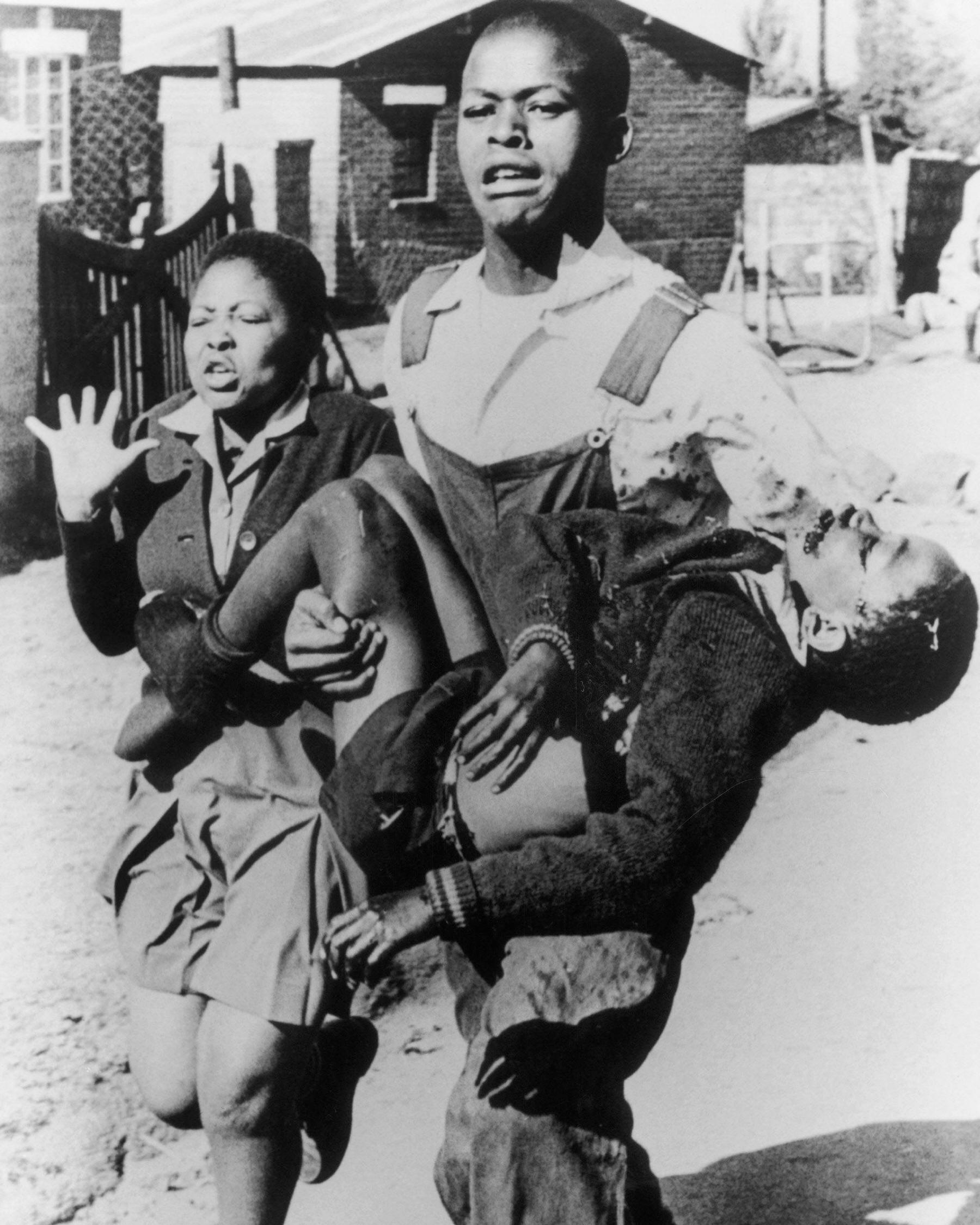

A full frame of the famous

photograph.

Photograph:

Sam Nzima

KEYSTONE-FRANCE/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

Searching for Soweto:

mystery of

a man whose image defined apartheid brutality

G

Thursday 16 June 2016 09.30 BST

Last modified on Thursday 16 June 2016 10.34 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jun/16/

soweto-uprising-40-year-anniversary-photo-south-africa-apartheid

Related

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/may/13/

sam-nzima-south-african-photographer-dies-aged-83-soweto

Jacob

Gedleyihlekisa Zuma

South African

politician who served

as the fourth

president of South Africa

from 2009 to

2018.

He is also

referred to by his initials JZ

and clan names

Nxamalala and Msholozi.

Zuma was a

former anti-apartheid activist,

member of

uMkhonto weSizwe,

and president of

the African National Congress (ANC)

from 2007 to

2017.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Jacob_Zuma

https://www.theguardian.com/world/

zuma

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Jacob_Zuma

https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/international/311224/

jacob-zuma-

le-president-accuse-d-avoir-fait-main-basse-sur-l-afrique-du-sud

Breyten

Breytenbach 1939-2024

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Breyten_Breytenbach

https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/fil-dactualites/241124/

mort-de-l-ecrivain-sud-africain-et-militant-anti-apartheid-breyten-breytenbach

https://www.nytimes.com/1983/05/01/

books/a-south-african-poet-on-his-imprisonment.html

https://www.nytimes.com/1982/12/06/

world/south-african-poet-freed-after-7-years.html

Desmond Mpilo

Tutu 1931-2021

Then-Bishop Tutu and his wife,

Nomalizo Leah Tutu,

at the General Theological

Seminary in New York in 1984.

Photograph:

Don Hogan Charles

The New York

Times

Desmond Tutu, Whose Voice Helped

Slay Apartheid, Dies at 90

The archbishop,

a powerful force for nonviolence

in South Africa’s anti-apartheid movement,

was awarded the Nobel Peace

Prize in 1984.

NYT

Dec. 26, 2021

Updated 4:30 a.m. ET

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/26/

obituaries/desmond-tutu-dead.html

Desmond Mpilo

Tutu 1931-2021

cleric who used his pulpit and

spirited oratory

to help bring

down apartheid in

South Africa

and then became the leading advocate

of peaceful

reconciliation

under Black

majority rule

(...)

Archbishop Tutu had fought

an on-and-off

battle with prostate cancer

since 1997.

As leader

of the South

African Council of Churches

and later as Anglican

archbishop of Cape Town,

Archbishop Tutu

led the church

to the forefront

of Black South Africans’

decades-long

struggle for freedom.

His voice was a

powerful force for nonviolence

in the

anti-apartheid movement,

earning him a

Nobel Peace Prize in 1984.

When that

movement triumphed in the

early 1990s,

he prodded the

country toward a new

relationship

between its

white and Black citizens, and,

as chairman of the Truth and

Reconciliation Commission,

he gathered

testimony

documenting the viciousness

of apartheid.

“You are

overwhelmed by the extent of

evil,”

he said.

But, he

added, it was necessary

to open the

wound to cleanse it.

In return for an honest

accounting

of past crimes,

the committee

offered amnesty,

establishing what Archbishop

Tutu called

the principle of

restorative

— rather than

retributive — justice.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/26/

obituaries/desmond-tutu-dead.html

https://www.theguardian.com/world/

desmond-tutu

https://www.npr.org/2021/12/26/

494373491/desmond-tutu-dies

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/26/

obituaries/desmond-tutu-dead.html

https://www.npr.org/2021/12/26/

1047748076/desmond-tutu-dead-remembrance

https://www.theguardian.com/world/gallery/2021/dec/26/

archbishop-desmond-tutu-a-life-in-pictures

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/dec/26/

a-patriot-without-equal-world-mourns-after-death-of-desmond-tutu

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/dec/26/

archbishop-desmond-tutu-giant-in-fight-against-apartheid-south-africa-

dies-at-90

https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2015/04/23/

401013918/feeling-blue-share-a-laugh-with-archbishop-desmond-tutu

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/dec/13/

anc-petty-excluding-desmond-tutu-mandela-funeral

https://www.npr.org/templates/story/

story.php?storyId=124539592 - March 11, 20210

https://www.nytimes.com/1982/03/14/

magazine/south-africa-s-bishop-tutu.html

Post Apartheid

South Africa

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/21/

documenting-violence-against-migrants-in-south-africa-a-photo-essay

https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/04/21/

837437715/photos-lockdown-in-the-worlds-most-unequal-country

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/gallery/2020/apr/15/

deep-inequalities-of-social-distancing-in-south-africa-in-pictures-coronavirus

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/oct/21/

tell-us-south-african-cities-after-apartheid

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/20/

world/africa/xenophobia-nigerians-south-africa.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/01/

lens/examining-identity-race-and-responsibility-

among-white-south-africans.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/26/

lens/kibera-stories-photography-africa.html

2016

Divided cities:

South Africa's

apartheid legacy photographed by drone

Vusimuzi/Mooifontein Cemetery,

Johannesburg

Photograph:

Johnny

Miller/Millefoto/Rex/Shutterstock

Divided cities:

South Africa's

apartheid legacy photographed by drone

G

Thursday 23 June 2016 11.30 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/gallery/2016/jun/23/south-africa-

divided-cities-apartheid-photographed-drone

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/gallery/2016/jun/23/

south-africa-divided-cities-apartheid-photographed-drone

Roelof Frederick

Botha 1932-2018

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/12/

obituaries/pik-botha-dead.html

"Winnie" Madikizela-Mandela 1936-2018

Under Apartheid,

black South

Africans weren’t allowed

to live in the cities;

townships were

created for them

on the outskirts.

All of the jobs,

blue-collar or domestic, were in the cities,

and the

train-and-bus commute from the townships

could take two

hours.

https://archive.nytimes.com/lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2016/07/13/

real-life-south-african-liberation-stories-santu-mofokeng/

https://archive.nytimes.com/lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2016/07/13/

real-life-south-african-liberation-stories-santu-mofokeng/

Steve Biko /

Stephen Bantu Biko 1946-1977

A man holds a picture

of South

African students leader Steve Biko,

at his funeral in King William’s

Town, 1977.

Photograph: AFP

Getty Images

Peter Gabriel – 10 of the best

G

Wednesday 2 November 2016 09.48 GMT

Last modified on Wednesday 2 November 2016 09.49 GMT

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/nov/02/

peter-gabriel-10-of-the-best

anti-apartheid

activist in South Africa

in the 1960s and

1970s

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Steve_Biko

https://www.npr.org/2025/09/12/

nx-s1-5539024/south-africa-reopens-inquest-death-steve-biko

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/nov/02/

peter-gabriel-10-of-the-best

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/feb/18/

steve-biko-south-africa-struggle

http://www.nytimes.com/1997/02/04/

opinion/the-truth-about-steve-biko.html

http://www.nytimes.com/1987/12/26/

movies/re-creating-steve-biko-s-life.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biko_(song)

- Released 1980 Recorded 1979

Rioting in

Guguletu, near Cape Town 1976

A South African policeman

collars a black student

during rioting in Guguletu, near

Cape Town, 1976.

Photograph: AP

The brutal reality of apartheid

in South Africa

7 December 1976: This edited

eye-witness account

of the action by South African

police

in a black township near Cape Town

was written by a ‘coloured’

teache

in a letter to a friend in Britain

G

Mon 7 Dec 2015 05.00 GMT

Last modified on Mon 7 Dec 2015 05.06 GMT

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/dec/07/

apartheid-south-africa-cape-town-police-protests

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/dec/07/

apartheid-south-africa-cape-town-police-protests

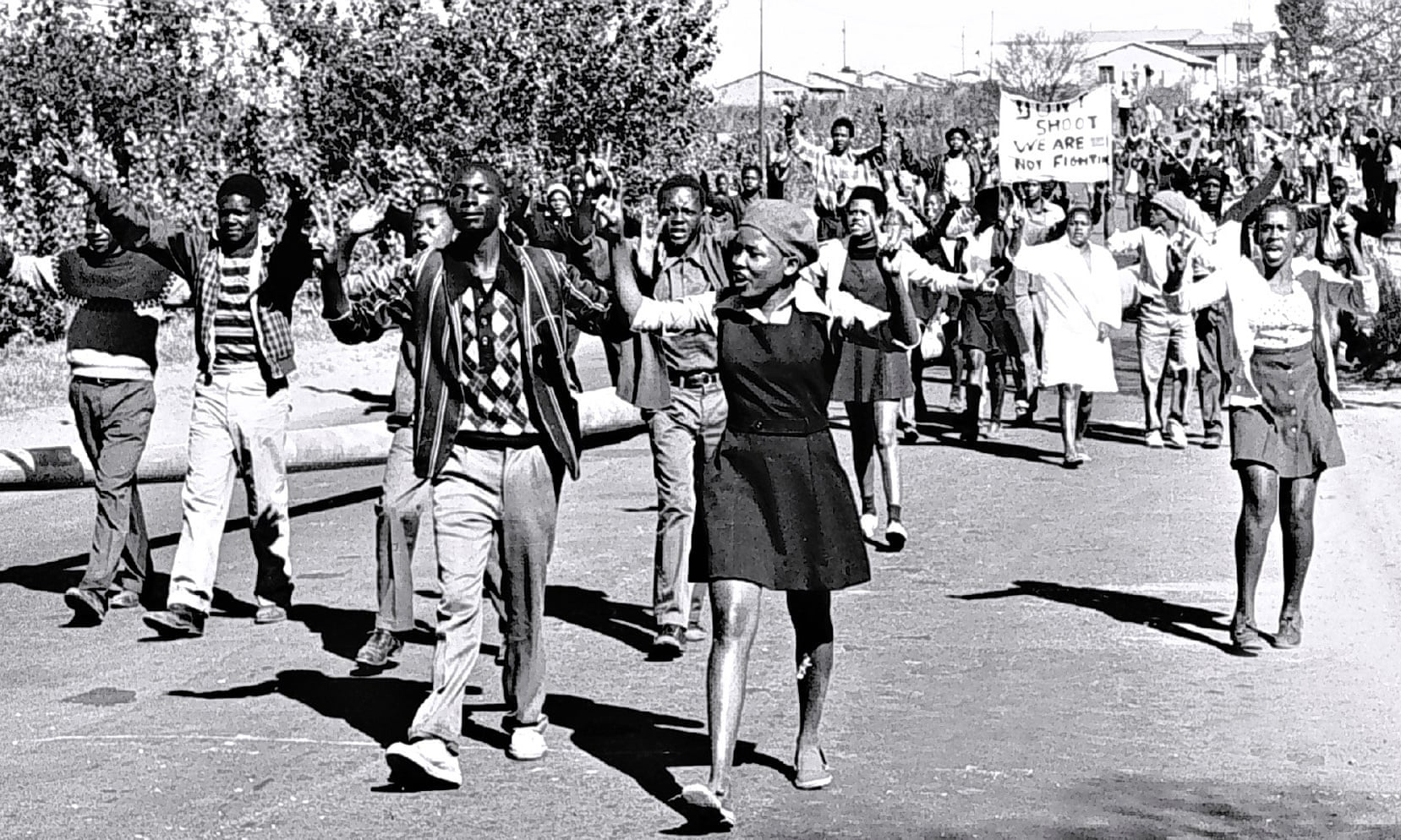

Soweto uprising

June 1976

High-school students in Soweto,

South Africa,

protest for better education.

Police fired teargas and live

bullets

into the marching crowd killing innocent people

and

ignited what is known as The Soweto Uprising,

June

1976.

Photograph: City Press

Getty

Images

S African riot evokes shades of

Sharpeville

June 16 1976:

On this day

clashes between school students

and police

in the Soweto township

ended with at least eight dead.

This is how the Guardian

reported the events.

G

Thu 17 Jun 1976 11.35 BST

First published on Thu 17 Jun

1976 11.35 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/world/1976/jun/17/

southafrica.fromthearchive

Thousands of

black children

and teenagers

had taken to the

streets of Soweto

in June 1976

to protest being

forced to study in Afrikaans.

Police responded

to the peaceful

protest with force,

spraying bullets at the schoolchildren.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jun/16/

soweto-uprising-40-year-anniversary-photo-south-africa-apartheid

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Soweto_uprising

https://www.theguardian.com/world/1976/jun/17/

southafrica.fromthearchive

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/gallery/2023/may/26/

kissinger-at-100-statesman-or-war-criminal-his-troubled-legacy-

in-pictures

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/gallery/2024/jan/12/

to-fight-with-my-camera-to-kill-apartheid-

peter-magubane-south-african-photographer

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/may/25/

henry-kissinger-100-strategic-genius-or-damaging-diplomacy-held-back-africa

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/gallery/2023/may/26/

kissinger-at-100-statesman-or-war-criminal-his-troubled-legacy-

in-pictures - Guardian picture gallery

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jun/16/

soweto-uprising-40-year-anniversary-photo-south-africa-apartheid

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jun/16/

my-activism-started-then-the-soweto-uprising-remembered

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jun/16/

soweto-uprising-40-years-on-hector-pieterson-image-shocked-the-world

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/jun/14/

southafrica.gideonmendel

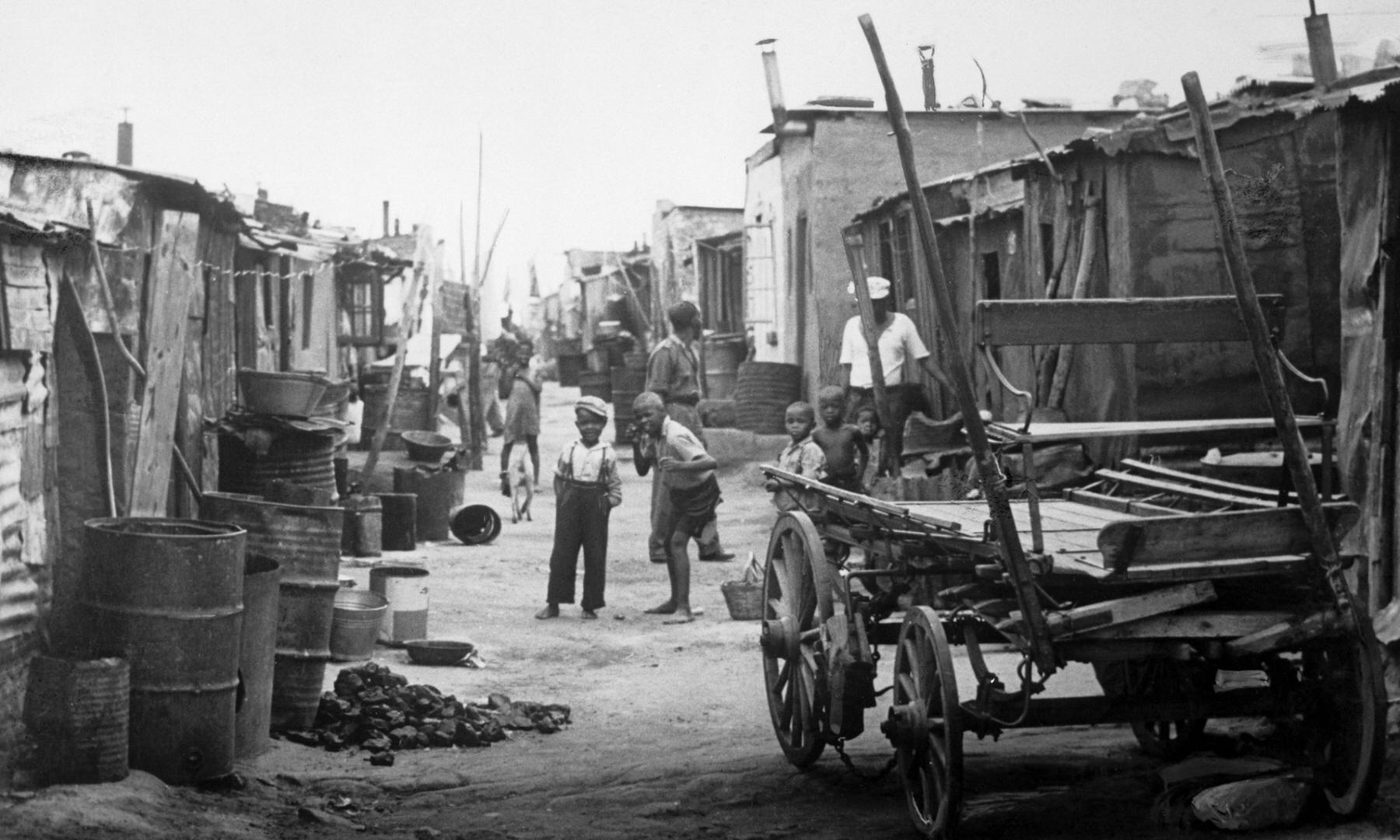

Sophiatown in 1955,

when black South Africans

were

being forced out to southern townships.

Photograph: Bettmann

Corbis

Story of cities #19:

Johannesburg's apartheid purge of vibrant Sophiatown

G

Monday 11 April 2016 08.20 BST

Last modified on Wednesday 20 April 2016 12.17 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/apr/11/

story-cities-19-johannesburg-south-africa-apartheid-purge-sophiatown

9 February, 1955

Sophiatown

The bulldozers arrived in Sophiatown

at five o’clock on

the morning

of 9 February, 1955.

Behind them in the

darkness,

police commanderslined up

with piles of paper

– lists of names and

addresses,

eviction notices, and assignments

to

new plots in the Meadowlands suburb,

15 kilometres away

on

the northern edge of Soweto.

Behind the

commanders,

an army of 2,000

police carried rifles and batons,

ready to enforce the

eviction

and clear Sophiatown of its black residents.

“Maak julle oop!”

they shouted in

Afrikaans.

“Open up!”

By sunrise,

110

families had been forced to remove

all

belongings from their homes,

pile into police

trucks

and move out to the Meadowlands,

where hundreds of

matchbox homes

awaited them.

Sophiatown was one of

the last remaining areas

of black

home-ownership in Johannesburg.

Five years earlier,

the South African parliament

had passed the Group

Areas Act,

which sought to purge black South Africans

from developed neighbourhoods

and establish “urban

apartheid”.

In Johannesburg,

the act gave license to the city’s government

to push middle-class black residents

out of northern areas including Sophiatown

into southern townships such as Soweto,

where

the majority of poor black residents

already lived.

http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/apr/11/

story-cities-19-johannesburg-south-africa-apartheid-purge-sophiatown

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/apr/11/

story-cities-19-johannesburg-south-africa-apartheid-purge-sophiatown

1946

Asiatic Land Tenure

and Indian

Representation Act

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Asiatic_Land_Tenure_and_Indian_Representation_Act,_1946

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/29/

ahmed-kathrada-obituary

1927

The Immorality Act, 1927 (Act No. 5 of 1927)

was an act of the Parliament of South

Africa

that prohibited extramarital

sex

between white people and people of other races.

In its original form it only prohibited sex

between a white person and a black person,

but in 1950 it was amended

to apply

to sex between a white

person

and any non-white person.

- Wikipedia,

December 18, 2022

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immorality_Act,_1927

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Immorality_Act,_1927

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/16/

books/review/scatterlings-resoketswe-manenzhe.html

Nelson Mandela:

How

Africa has changed

in his lifetime

Nelson

Mandela's life

spanned the continent's transition

from colonialism to independence

as the white powers that ruled it

were forced to give up their grip

Sunday 8

December 2013

The Observer

Chris McGreal

This article appeared on p10 of the Special supplement section of the Observer

on Sunday 8 December 2013.

It was published on the Guardian website

at 19.00 GMT on Sunday 8 December 2013.

July

1918: Africa at the time of Mandela's birth

Nelson Mandela was born into a continent colonised and in servitude to European

powers. Only Ethiopia and Liberia were independent. But Germany's defeat in the

first world war brought about a reworking of the colonial order with its

possessions in what are now Tanzania, Cameroon, Togo, Burundi and Rwanda

distributed among the war's victors – Britain, France and Belgium. German South

West Africa, now Namibia, fell under South African control.

Mandela was a citizen of a new country: South Africa had been born eight years

earlier with the unification of four British colonies, including the two former

Afrikaner republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, taken over after

the Boer war. Ironically, the Boer struggle was widely seen as the first

anti-colonial fight of the 20th century against the British empire.

South Africa, because of its large white population, was a politically

autonomous dominion under the British crown, unlike the UK's other African

colonies. In 1918, some territories were still regarded as the private property

of commercial companies. Southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, was owned by the

British South Africa Company and would not be recognised as a colony until 1923.

Whatever the status of territory, the plunder of Africa's wealth – its gold,

rubber, tobacco, diamonds, ivory and copper – was unrelenting. But the seeds of

the independence movements were sown with the hundreds of thousands of Africans

who served in the first world war helping to raise political awareness and

challenge white claims of racial superiority.

1936-1945: Invasion and the second world war

Ethiopia was one of only two independent countries in Africa when the Italian

fascist dictator, Benito Mussolini, decided to expand his small "African

empire". Italy invaded in 1936, overthrowing Emperor Haile Selassie and

confirming the League of Nations as toothless in the face of fascist aggression.

Ethiopia was integrated into Italian East Africa with Eritrea and Italian

Somaliland.

From 1940, the desert war ranged across north Africa for three years, swinging

from French Tunisia through Italian Libya to within striking distance of Cairo.

That conflict once again remade the colonial map, with Italy forced to

relinquish its rule of Libya and Somalia, and Ethiopia liberated in 1941. It was

also deciding the future of imperial rule in less immediately evident ways.

After the war, France recovered possession of Tunisia, where a sizeable

expatriate population lived, but its authority was fatally undermined and it was

independent within a few years, along with Morocco.

Newly demobilised African soldiers who served the allied cause in north and east

Africa, Europe and Asia arrived home questioning the disconnect between the

Allies' trumpeting of freedom with the continued subjugation of their own

continent.

A smattering of well-educated anti-colonial leaders provided the arguments and

the direction to draw increasingly restless Africans into the struggle for their

freedom.

1948:

Apartheid

The National party won power in South Africa with an unexpected and narrow

victory on a platform of more rigid race segregation. Afrikaner leaders

portrayed apartheid as a form of social upliftment for poorer whites, in part by

protecting their jobs from cheaper black labour. The vote for the National party

was also in part a backlash against British influence by Afrikaners still bitter

about the Boer war and loss of self-determination. At the time, Britain and its

western allies sought to placate the new government in Pretoria which did not

immediately look so out of step with the colonial regimes and their systems of

race-based privilege, power and segregation.

But as the British prime minister, Harold Macmillan, reminded the South African

parliament in his "wind of change" speech in Cape Town in 1960, the apartheid

government was on the wrong side of history. South Africa left the British

Commonwealth the following year.

The rapid decolonisation of most of Africa helped drive the white regime's

increasingly repressive response to resistance to apartheid legislation,

including the arrest and trial of Mandela and other ANC leaders.

1956 on:

Decolonisation

The tumble of decolonisation across sub-Saharan Africa began with the Gold

Coast, reborn as Ghana in 1957.

Ghana's first president, Kwame Nkrumah, espoused a pan-African philosophy that

inspired other subjugated nations and alarmed complacent imperialists who

initially imagined they could drag out the independence process in other parts

of Africa, especially in countries where there were large numbers of white

settlers.

But Britain had learned the hard way with the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya that if

it was not prepared to negotiate an end to its rule then Africans would fight

for it. Within a few years, most of Britain's colonies in Africa had gained

independence or were on the brink of it.

France gave up control of two of its north African Arab colonies, Tunisia and

Morocco, in 1956 in the hope of clinging to a third – Algeria, then home to

close to one million white settlers, which Paris regarded as a department of

France.

The ensuing struggle brought down the French Fourth Republic and stripped Paris

of its colonial delusions. Paris's brutal "pacification" of the independence

struggle pushed Algeria to civil war. The French claimed military victory but

the political shock at home was so great that Algerian independence could no

longer be resisted.

The Algerian war helped dispel any lingering hopes of France holding on to its

sub-Saharan colonies and most were freed in a burst of independence celebrations

in 1960. Belgium pulled out of the Democratic Republic of the Congo the same

year, and Rwanda and Burundi two years later.

But Paris made sure to hold its former colonies close through economic,

political and military ties, including underpinning regional currencies.

1960-1980: White resistance to decolonisation

As the imperial powers withdrew, the determination of the remaining settler

administrations to hold on to power hardened. Ian Smith's white government of

Rhodesia made a unilateral declaration of independence on 11 November 1965 in

resistance to the UK's plans to make the colony independent. Britain declared

the move an "act of treason". Rhodesia found backing from apartheid South

Africa, including crucial economic assistance, and Portugal, which gave access

to ports in Mozambique. But Rhodesia was besieged by sanctions and then an

escalating insurgency in the 1970s which strengthened after Mozambique gained

independence and provided a base for Robert Mugabe's Zanu guerrillas.

Eventually, the white minority regime was overwhelmed by the military and

economic pressures, although Smith later blamed South Africa for Rhodesia's

collapse, saying it had been "stabbed in the back" by Pretoria. Mugabe became

the first – and only prime minister – of an independent Zimbabwe in 1980.

Armed independence movements launched rebellions in the early 60s in Portugal's

remaining territories – Angola, Mozambique and Guinea – and were met with

increasing brutality. The economic and political toll of the conflict helped

prompt a coup in 1974 that overthrew the rightwing regime in Lisbon. Angola,

Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau gained independence the following year.

1960-1980s: Cold war

The early hope of the newly independent African nations was rapidly undermined

by the cold war struggle as Soviet backing for African liberation movements was

countered by American support for military coups and authoritarian leadership.

Under protection of western aid based largely on anti-communist credentials with

little concern about the quality of governance, military dictatorships and

one-party states run by presidents-for-life emerged from Nigeria to Malawi,

Kenya to Zambia, Zaire to Ivory Coast, while the Soviets sponsored governments

such as Ethiopia and Mozambique.

The cold war confrontation was at its bloodiest in Angola where the

Soviet-backed government and Cuban troops fought a long war against Jonas

Savimbi's US-sponsored rebels and South Africa's army. The conflict destroyed

towns and villages across the oil-rich country and cost hundreds of thousands of

lives.

For many years during the 1970s and 1980s, Africa was defined to much of the

rest of the world by its more brutal and extreme leaders, such as Uganda's Idi

Amin, who was regarded as part clown and part monster, and Zaire's Mobutu Sese

Seko, who stole billions of dollars while his country collapsed around him.

1976:

The beginning of the end for apartheid

Neither South Africa's white regime nor Mandela's ANC predicted the Soweto

uprising, which kicked off the escalating popular resistance that played a

central role in bringing down apartheid. On 16 June 1976, thousands of students

took to the streets against the government forcing black schools to teach many

lessons in Afrikaans, not only seen as the language of the oppressor but also as

a further means of keeping black people down.

The South African police responded to the protest with violence, killing 23

people on the first day, including 13-year-old Hector Pieterson, who became a

symbol of the uprising. Hundreds more died in the following months. The protests

marked a new wave of popular protest against apartheid inside South Africa which

put the ANC at the forefront of the liberation struggle inside the country. The

white regime responded with increasing repression that only fed the popular

resistance and gave rise to a broad coalition of opponents of apartheid,

including trade unions, churches and civic groups, under the umbrella of the

United Democratic Front. The white government's increasingly heavy-handed

response fuelled international outrage and led to the tightening of sanctions.

1990:

Freedom

Mandela's release from prison on 11 February 1990 prompted a wave of expectation

among people across Africa weary of maladministration and political leaders

clinging to power. Old leaders were forced out across the continent, including

in Zambia, Malawi and Kenya. A much heralded "new breed" of leader had already

emerged led by Yoweri Museveni in Uganda, although he, too, came to be accused

of authoritarian tendencies after ruling his country for longer than any of his

predecessors.

The press for political change was less successful elsewhere, and in Nigeria it

resulted in another military coup. Newfound political freedom could not release

African nations from their dependence on foreign aid which came with added

strings requiring adherence to western neo-liberal economics. Some African

states had already suffered the imposition of International Monetary Fund and

World Bank economic plans which proved particularly harsh on the poorest by

reversing the benefits they enjoyed such as free schooling. More countries were

forced into privatisation programmes and other measures that caused hardship and

undermined support for newly elected democratic governments.

Mandela was elected South Africa's president in 1994 and set an example by

stepping down five years later. He was replaced by his deputy, Thabo Mbeki,

regarded in the west as a steady pair of hands with a strong intellect but his

credibility was eroded by outlandish views on the Aids epidemic and for siding

with Zimbabwe's Robert Mugabe.

1994:

Genocide

As South Africa celebrated its newfound democracy, Rwanda was descending into

its own particular hell. The post-cold war pressure for democratisation combined

with the legacy of colonial racial theory to prompt Hutu extremists to attempt

to cling on to power by engineering the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of

Tutsis. The genocide set in motion a series of events that saw the toppling of

neighbouring Zaire's long-standing ruler, Mobutu Sese Seko, and years of war in

what became the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Out of the tragedy emerged a

new Rwanda led by one of Africa's most polarising leaders, President Paul

Kagame.

The Rwandan genocide also helped shape international justice, with a United

Nations tribunal to try the organisers of the slaughter that presaged another in

Sierra Leone and the birth of the international criminal court. African leaders

initially welcomed the ICC after it indicted Joseph Kony, leader of the Lords

Resistance Army responsible for recruiting child soldiers and other crimes in

Uganda. But the mood changed as the court came to be seen increasingly as

exercising a double standard in indicting African leaders, including in Sudan

and Kenya, while avoiding investigation of actions of western leaders in

Afghanistan and Iraq.

Future

China is

emerging as the new foreign economic and political force in Africa. Some have

condemned Beijing's rising influence as a new form of neocolonisation. Others

praise China for helping to release African nations from their dependence on

western aid.

China's thirst for minerals and oil, and its hunt for markets for its goods, has

seen it develop close ties to Angola, Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the

Congo. It has bought up copper mines in Zambia and all but killed the textile

industry there by flooding the country with cheap clothes.

Critics of Beijing's expanding influence in Africa say that China is so hungry

for resources it does deals with authoritarian regimes and doles out aid without

consideration of issues such as good governance.

But China has also delivered on promised aid after decades in which western

governments cared more about the political alignments of African leaders than

development of their countries. Beijing has built an extensive new network of

roads in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, for instance, after decades in

which the number of paved roads fell sharply despite billions of dollars in

western aid.

Growing Chinese influence alarms Washington. Hillary Clinton, then the US

secretary of state, warned last year that Beijing is out to plunder the

continent and African governments would do well to huddle under the protective

wing of America's supposed commitment to freedom.

Nelson Mandela: How Africa has changed in his lifetime,

G,

8.12.2013,

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/dec/08/

nelson-mandela-how-africa-changed

After Mandela:

South

Africa as Miracle or Mirage?

June 10, 2008

12:35 AM ET

NPR

Charlayne

Hunter-Gault

When Nelson

Mandela took power from the white minority government in South Africa in 1994,

the longtime anti-apartheid activist held out hope that this was the beginning

of the end of his people's poverty and the decades-long oppression that kept

them in it.

His gestures of reconciliation toward his and their erstwhile oppressors are

credited with avoiding bloody conflict in the country, leading the world to hail

South Africa as a "miracle."

Today, South Africa is at a crossroads. The heirs to Mandela's legacy are

battling among themselves, as the hope he inspired is fading under the weight of

unmet needs for the black masses.

This is no excuse, but it makes it more understandable how, once started, recent

attacks on immigrants from other parts of the continent to South Africa spread

like the kerosene fires that destroy entire neighborhoods after poorly

constructed stoves explode while meager dinners are being prepared.

It was pent-up rage that, in the end, was misdirected at immigrants who have

fled their own economic or political impoverishment to enjoy the fruits of South

Africa's "miracle" — a miracle that may, in fact, have been a mirage.

When I first came to South Africa in 1985 on one of many assignments I would

take over more than two decades, an Afrikaner told me the reason for not

permitting "one person, one vote" was that South Africa was both First World and

Third World.

By that, he meant the whites who controlled the economy and reaped its benefits,

including a first-class education, were First World. And the blacks, who labored

in the mines, the fields, the kitchens and other rooms of the privileged, and

who were being deliberately undereducated so that they could remain subservient,

were Third World.

But as I traveled around the country in recent weeks, reporting for the NPR

series "South Africa at the Crossroads," those words came back to me, albeit in

a different context.

Even with a black-led government, the country remains two separate nations: one

white and largely in control of the economy; the other, a majority of blacks

still outside the economic mainstream.

Of course, successful, high-profile black millionaires and even billionaires

exist. But the nation's official unemployment rate is more than 25 percent.

Unofficially, it's as high as 85 percent in the townships and informal

settlements. The legacy of the apartheid system of separate and unequal

education has left most of the unemployed without the skills to compete in an

emerging market economy.

President Thabo Mbeki's government has received plaudits in financial circles at

home and abroad for the sound conservative fiscal policies it has pursued. But

recent global and local shocks to the system, including spiraling gas prices and

massive power outages, have caused economists and other analysts to predict a

slowdown in the nation's growth and increasing trouble absorbing the unemployed

masses.

South Africa also is dealing with one of the highest crime rates in the world.

AIDS continues to put an enormous strain on the nation. And then there's another

lingering legacy of apartheid: racism, still ever-present in a nation that

Mandela hoped would reflect an ethnic rainbow.

South Africa's myriad problems are being exacerbated by the political battles

within the ruling party. Accused of being out of touch with the needs of

ordinary people, Mbeki lost control of the African National Congress to his main

political rival, Jacob Zuma, in December.

So, for the first time in its short history as a ruling party, the ANC has two

centers of power — a president of the party and a president of the country —

leading to concerns that urgent needs of the nation's poor may become hostage to

political gridlock.

In recent weeks, there have been calls for Mbeki to step down, but he has shown

no signs of acting on them. Not long ago, he downplayed the turmoil within the

party, insisting it was all part of the natural evolution of a liberation

movement becoming a governing party.

Jody Kollapen, chairman of the Human Rights Commission, argues that South Africa

may indeed be at a crossroads. But he says that perhaps critics and analysts

(and journalists) should be taking a longer view, recognizing that South Africa

is a new democracy, undergoing growing pains common to new democracies all over

the world — including America's, during its early years of independence.

"Maybe it's time to recognize that South Africa is not a miracle country,"

Kollapen says. "Maybe we should just come down to earth and say, 'We're an

ordinary people perhaps, having done some extraordinary stuff, but maybe the

world should let us be an ordinary country.'"

After Mandela:

South Africa as Miracle or Mirage?,

NPR,

June 10, 2008,

https://www.npr.org/templates/story/

story.php?storyId=91330104

Related > Anglonautes > History

South

Africa > 20th, early 21st century

Related > Anglonautes >

Vocapedia

Apartheid

Related > Anglonautes > Videos >

Documentaries > 2010s

South Africa

Related > Anglonautes > Arts /

Photojournalism >

South-Afrcan photographers

Santu Mofokeng 1956-2020

David Goldblatt 1930-2018

Ernest Cole 1940-1990

Related > Anglonautes > Arts /

Photojournalism >

Photographers >

South Africa

Peter Magubane 1932-2024

Santu Mofokeng 1956-2020

David Goldblatt 1930-2018

Grey Villet 1927-2000

Alfred Eisenstaedt 1898-1995

Ernest Cole 1940-1990

Margaret Bourke-White 1904-1971

Related

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/jun/26/

how-apartheid-killed-johannesburgs-cycling-culture-

|