|

History

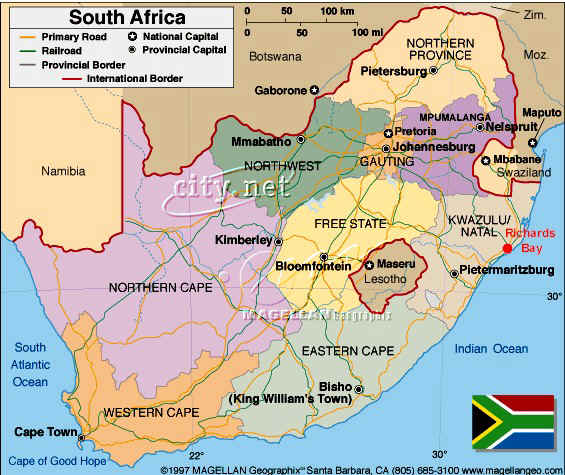

> 2004-2005 > South Africa

http://www.dolphins.org.za/rsa.jpg

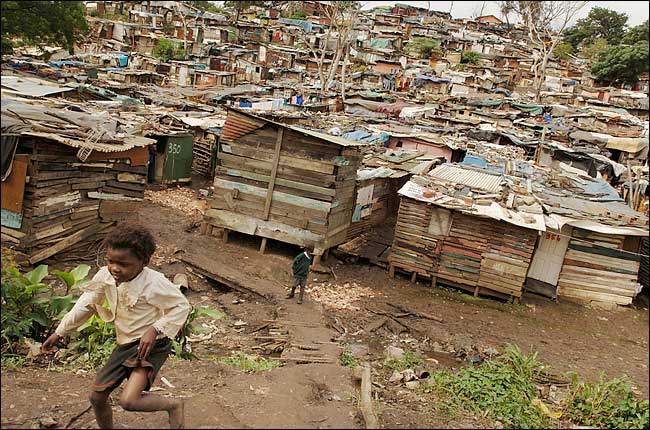

Children roamed the blighted landscape of Foreman Road,

a teeming hillside

slum of 1,000 tiny hovels

typical of South Africa's shantytowns.

Vanessa Vick for The New York Times

December 25, 2005

Shantytown Dwellers in South Africa Protest Sluggish Pace of

Change

NYT

25.12.2005

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/25/international/africa/25durban.html

Shantytown Dwellers in South Africa

Protest Sluggish Pace

of Change

December 25, 2005

The New York Times

By MICHAEL WINES

JOHANNESBURG, Dec. 24 - Sending what some call an ominous

signal to this nation's leaders, South Africa's sprawling shantytowns have begun

to erupt, sometimes violently, in protest over the government's inability to

deliver the better life that the end of apartheid seemed to herald a dozen years

ago.

At a hillside shantytown in Durban called Foreman Road, riot police officers

fired rubber bullets in mid-November to disperse 2,000 residents marching to the

municipal mayor's office downtown. Two protesters were injured; 45 were

arrested. The rest burned an effigy of the city's mayor, Obed Mlaba.

Their grievance was unadorned: since Foreman Road's 1,000 shacks sprang up

nearly two decades ago, the only measurable improvements to the residents' lives

amounted to a single water standpipe and four scrap-wood privies. Electricity

and real toilets were a pipe dream. Promises of new homes, they said, were

ephemeral.

"This is the worst area in the country," said one resident, a middle-aged man

who identified himself only as Senior. "We don't so much need water or

electricity. We need land and housing. They need to find us land and build us

new homes."

In Pretoria that week, 500 shantytown residents looted and burned a city council

member's home and car to protest limited access to government housing. Two weeks

earlier, protesters burned municipal offices in Promosa after being evicted from

their illegal shanties. In late September, Botleng Township residents rioted

after a sewage-fouled water supply caused 600 cases of typhoid and perhaps 20

deaths.

And just Thursday, Cape Town officials warned residents of a vast shantytown

near the city airport that they faced arrest if they tried to squat in an

unfinished housing project nearby.

South Africa's safety and security minister said in October that 881 protests

rocked slums in the preceding year; unofficial tallies say that at least 50 were

violent. Statistics for previous years were not kept, but one analyst, David

Hemson of the Human Sciences Research Council in Pretoria, estimated that the

minister's tally was at least five times the number of any comparable previous

period.

"I think it's one of the most important developments in the postliberation

period," said Mr. Hemson, who leads a project on urban and rural development for

the council. "It shows that ordinary people are now feeling that they can only

get ahead by coming out on the streets and mobilizing - and those are the

poorest people in society. That's a sea change from the position in, say, 1994,

when everyone was expecting great changes from above."

In fact, the government has made great changes. Since 1994, South Africa's

government has built and largely given away 1.8 million basic houses, usually 16

feet by 20 feet, often to former shantytown dwellers. More than 10 million have

gained access to clean water, and countless others have been connected to

electrical lines or basic sanitation facilities.

Yet at the same time, researchers say, rising poverty has caused 2 million to

lose their homes and 10 million more to have their water or power cut off

because of unpaid bills. And the number of shanty dwellers has grown by as much

as 50 percent, to 12.5 million people - more than one in four South Africans,

many living in a level of squalor that would render most observers from the

developed world speechless.

For South African blacks, the current plight is uncomfortably close to the one

they endured under apartheid. Black shantytowns first rose under white rule, the

result of policies intended to keep nonwhites impoverished and powerless. During

apartheid, from the 1940's to the 1980's, officials uprooted and moved millions

of blacks, consigning many to transit camps that became permanent shantytowns,

sending others to black townships that quickly attracted masses of squatters.

Privation led millions more blacks to migrate to the cities, setting up vast

squatter camps on the outskirts of Cape Town, Johannesburg, Durban and other

cities.

From its first days, South Africa's black government pledged to address the

misery of shanty life. That the problem has instead worsened, social scientists,

urban planners and many politicians say, is partly the result of fiscal policies

that have focused on nurturing the first-world economy which, under apartheid,

made this Africa's wealthiest and most advanced nation.

The government's low-deficit, low-inflation strategy was built on the premise

that a stable economy would attract investment, and that the wealth would spread

to the poor. But while the first-world economy has boomed, it has failed to lift

the vast underclass out of its misery.

Unemployment, estimated at 26 percent in 1994, has soared to roughly 40 percent

many analysts say; the government, which does not count those who have stopped

looking for work, says joblessness is lower. Big industries like mining and

textiles have laid off manual laborers, and expanding businesses like banking

and retailing have failed to pick up the slack. Many of the jobless have moved

to the slums.

So far, the shantytown protests have focused exclusively on local officials who

bear the brunt of slum dwellers' rage. But while almost all those officials

belong to the governing African National Congress, and execute the party's

social and economic policies, "the poor haven't made the connection as yet,"

said Adam Habib, another scholar at the Human Sciences Research Institute who

recently completed a study of South Africa's social movements.

On the contrary, national support for President Thabo Mbeki's governing

coalition appears greater than ever before. Still, Mr. Mbeki has been visiting

shantytowns and townships, promising to increase social spending and demanding

that his ministers improve services to the poor.

For now, nearly half the 284 municipal districts, charged with providing local

services, cannot, the national ministry for local government says. Their

problems vary from shrunken tax bases to inconsistent allotments of national

money to AIDS, which has depleted the ranks of skilled local managers.

Incompetence and greed are rife. In Ehlanzeni, a district of nearly a million

people in Mpumalanga Province, 3 out of 4 residents have no trash collection, 6

out of 10 have no sanitation and 1 in 3 lack water - and the city manager makes

more than Mr. Mbeki's $180,000 annual salary.

The frustrations of slum dwellers began to boil over in mid-2004, when residents

in a shantytown near Harrismith, about 160 miles southeast of Johannesburg,

rioted and blocked a major freeway to protest their living conditions. The

police fatally shot a 17-year-old protester. Since then, demonstrations have

spread to virtually every corner of the nation.

In Durban, the city is erecting some 16,000 starter houses a year, but the

shanty population, now about 750,000, continues to grow by more than 10 percent

annually.

The city's 180,000 shanties, crammed into every conceivable open space, are a

remarkable sight. Both free-standing and sharing common walls, they spill down

hillsides between middle-class subdivisions, perch beside freeway exits and

crowd next to foul landfills. They are built of scrap wood and metal and

corrugated panels and plastic tarpaulin roofs weighed down with concrete chunks.

Their insides are often coated with sheets of uncut milk and juice cartons, sold

as wallpaper at curbside markets, to keep both the wind and prying eyes from

exploiting the chinks in their shoddily built walls.

The 1,000 or so hillside shanties at Foreman Road are typical. A standpipe at

the top provides water, carried by bucket to each shack for bathing and

dishwashing. At the bottom, perhaps 400 feet down a ravine, are four hand-dug,

scrap-wood privies - each one, on this day, inexplicably padlocked shut.

Residents say they seldom trek down to the privies, relieving themselves instead

in plastic bags and buckets that can be periodically emptied or thrown away.

The one-room shacks provide the rudest sort of shelter. A bed typically takes up

half the space; a table holds cookware; clothes go in a small chest. There is no

electricity, and so no television; entertainment comes from battery-powered

radios. Residents use kerosene stoves and candles for cooking and heat, with

predictable results. A year ago, a wind-whipped fire destroyed 288 shacks here.

A fire at a Cape Town shantytown early this month left 4,000 people homeless.

A few shacks are painted in riotous colors or decorated with placards hawking

milk or tobacco, or shingled with signs ripped from light poles, once posted to

warn that electricity thieves had left live power lines dangling in the street.

The residents say Mayor Mlaba promised during his last election campaign to

erect new homes on the slum site and on vacant land opposite their hillside.

Instead, however, the city proposed to move the slum residents to rural land far

off Durban's outskirts - and far from the gardening, housecleaning and other

menial jobs they have found during Foreman Road's 16-odd years of existence.

Lacking cars, taxi fare or even bicycles to commute to work, the residents

marched in protest on Nov. 14, defying the city's refusal to issue a permit. The

demonstration quickly turned violent.

Afterward, in an interview that he cut short, a clearly nettled Mayor Mlaba

argued that the protest had been the work of agitators bent on embarrassing him

before local elections next year.

"Of course it's political," he said. "All of a sudden, they've got leaders.

There weren't any leaders yesterday. Are they going to be there in 2006 or 2007,

after the elections?"

Also suspecting agitators, South Africa's government reacted initially to the

shantytown protests by ordering its intelligence service to determine whether

outsiders - a "third force" in the parlance of this nation's liberation

struggles - sought to undermine the government.

Residents here scoff at that. "The third force," said the man called Senior, "is

the conditions we are living in."

In a shack roughly 7 feet by 8 feet, a third of the way down Foreman Road's

ravine, Zamile Msane, 32, lives with her 58-year-old mother and three children,

ages 12, 15 and 17. Ms. Msane has no job. A sister gives her family secondhand

clothes, and neighbors donate cornmeal for food. In seven years, she has fled

three wildfires, in 1998, 2000 and 2004, losing everything each time.

Yet Ms. Msane, who came here from the Eastern Cape eight years ago, said she

would not return to the farm where she once lived, because there was nothing to

eat.

Ms. Msane said she joined the Nov. 14 march for one reason.

"Better conditions," she said. "It's not good here, because these are not proper

houses. There's mud outside. We're always living in fear of fires. Winter is too

cold; summer is too warm. Life is so difficult."

Shantytown Dwellers

in South Africa Protest Sluggish Pace of Change, NYT, 25.12.2005,

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/25/international/africa/25durban.html

A Freedom Park,

misère et séropositivité

règnent toujours sur le bidonville des mineurs

01.12.2005 | 16h16 • Mis à jour le 01.12.2005 | 16h16

Article paru dans l'édition du 02.12.2005

Le Monde

JOHANNESBURG

CORRESPONDANTE

Fabienne Pompey

Personne, à Freedom Park, ne prononce jamais le mot

"prostitution". Pourtant, dans cet immense bidonville, ce "camp de squatteurs"

selon la terminologie locale, des centaines de femmes se vendent pour trois fois

rien. Les clients, pudiquement appelés "boyfriends", petits amis d'une heure,

d'une nuit ou d'un mois, sont des mineurs d'Impala Platinium, l'un des plus

grandes mines de platine du pays. La mine, situé dans la Northern Province, à

quelque 200 km au nord de Johannesburg, a attiré des milliers de ruraux, venant

de toute l'Afrique du Sud et des pays voisins. Aujourd'hui, à Freedom Park, il y

a environ 5 000 " shacks", des baraques de tôles alignées à perte de vue,

peintes en rouge vif, jaune ou bleu, des couleurs pour cacher la misère.

La plupart des 20 000 habitants du bidonville sont sans

emploi. Ici, il y a quelques hommes, en attente d'un job à la mine, et des

femmes vivant de la "générosité" des mineurs. Les liaisons ne sont jamais

qu'éphémères. Le mineur cherche une femme pour une heure, une soirée, parfois

pour plus longtemps, mais un jour il repart dans son village, laissant derrière

lui ses amours illégitimes. Environ 40 % des femmes de Freedom park sont

séropositives.

Boniwe avait un "boyfriend", qui veillait sur elle depuis plusieurs années.

Quand il est mort, sa femme est venue vider la maison. Dans son shack, il n'y a

plus rien qu'un lit, une petite table et quelques écuelles. Elle vit là avec ses

quatre enfants, parmi lesquels des jumeaux de 11 mois. L'un des deux est

séropositif. Comme plus de 500 personnes, essentiellement des femmes, Boniwe a

pu avoir accès à un traitement gratuit dans la clinique du bidonville. Mais ce

matin, elle n'a pas pris ses médicaments. "Je n'avais rien à manger. Et on peut

pas les prendre le ventre vide", explique-t-elle.

La clinique, qui existe grâce à des dons privés et à un fonds américain, a été

créée par l'association Tapologo de Mgr Kevin Dowlings, archevêque de

Rustenburg, la grande ville voisine. Il est le seul évêque catholique du pays à

avoir préconisé publiquement l'usage du préservatif.

PAS D'EAU COURANTE

Selina a été l'une des premières à bénéficier de la

distribution d'antirétroviraux. "Avant, c'était facile de trouver un boyfriend

capable de payer jusqu'à 1000 rands (125 euros) pour une passe. Les types qui

étaient virés avec une prime, ou les retraités, ils dépensaient beaucoup

d'argent avant de retourner chez eux. Maintenant, tu peux difficilement avoir

plus de 100 rands (12,5 euros)", explique-t-elle. "Et si tu demandes qu'ils

portent un préservatif, c'est moins encore", poursuit-elle. En réalité, la passe

se négocie souvent à 20 rands, à peine 2,50 euros.

Il n'y a rien ici, pas d'eau courante, pas de robinet public. Des camions

passent chaque jour pour vendre de l'eau. Pourtant, il y a des citernes un peu

partout. "Ils viennent les remplir avant les élections : après, c'est fini",

raconte Batsesana, qui dirige l'équipe de bénévoles.

Tout, ici, est provisoire. Même la clinique, faite de quelques containers, est

prête à être déplacée. Les Sud-Africains peuvent prétendre à l'une des petites

maisons que l'Etat bâtit non loin de là. Les étrangers, eux, n'ont droit à rien.

A terme, l'objectif de la municipalité est de raser Freedom Park, d'effacer à

coups de bulldozer la misère et ses prostituées.

A Freedom Park,

misère et séropositivité règnent toujours sur le bidonville des mineurs, LE

MONDE | 01.12.2005 | 16h16 • Mis à jour le 01.12.2005 | 16h16, article paru dans

l'édition du 02.12.2005,

http://www.lemonde.fr/web/article/0,1-0@2-3212,36-716348@51-689430,0.html

South Africa Court

Removes Barriers to Same-Sex Marriages

December 1, 2005

By REUTERS

Filed at 10:59 a.m. ET

The New York Times

JOHANNESBURG (Reuters) - South Africa's top court said on

Thursday it was unconstitutional to deny gay people the right to marry, putting

it on track to become the first African country to legalize same-sex marriage.

The Constitutional Court told parliament to amend marriage laws to include

same-sex partners within the year -- a step that runs counter to widespread

African taboos against homosexuality.

``The exclusion of same-sex couples from the benefits and responsibilities of

marriage ... signifies that their capacity for love, commitment and accepting

responsibility is by definition less worthy of regard than that of heterosexual

couples,'' Justice Albie Sachs said in the ruling.

The court said if parliament did not act, the legal definition of marriage would

be automatically changed to include same-sex unions. That would put South Africa

alongside Belgium, the Netherlands, Spain and Canada in allowing gay marriages.

Elated gay and lesbian couples and supporters hugged each after the judgment,

although some said they were disappointed they had to wait longer to get

married.

``We would've liked to get married as soon as we could,'' said Fikile Vilakazi,

wearing a yellow T-shirt with the words ''Marriage -- anything less is not

equal.''

``I'm very happy though that finally our courts have discovered that the common

law definition of marriage is unconstitutional.''

Post-apartheid South Africa has one of the most progressive constitutions in the

world and the only one to enshrine equal rights for gays and lesbians.

Many African countries, by contrast, outlaw homosexuality and turn a blind eye

to persecution of gays and lesbians.

South African gay activists have won a string of legal victories in recent

years, including the right to adopt children and inherit from partners' wills,

but so far the right to marry has eluded them.

THE SECULAR AND THE SACRED

South Africa's ruling African National Congress, which under Nelson Mandela led

the country from apartheid to democracy, said the ruling affirmed the state

should not discriminate against its citizens.

``Today's ruling, like other before it, is an important step forward in aligning

the laws of the country with the rights and freedoms contained in the South

African Constitution,'' the ANC, which dominates South Africa's parliament, said

in a statement.

The case stemmed from an application won a year ago by a lesbian couple to have

their marriage recognized in a lower court. Government lawyers appealed, arguing

only parliament should have the right to change the country's laws.

The couple was backed by the country's leading gay rights group, the Lesbian and

Gay Equality Project.

Only one of the court's 11 judges dissented from the ruling, arguing it should

have legalized gay marriage immediately instead of allowing 12 months for

parliament to act.

Sachs dismissed religious objections to gay marriage, saying the country's

constitution gave no reason why gays and religious groups could not co-exist.

``In the open and democratic society contemplated by the Constitution there must

be mutually respectful co-existence between the secular and the sacred,'' he

said.

South Africa's biggest Christian party, which has taken a strong anti-gay stance

in the past, held to its objection.

``Studies of previous civilizations reveal that when a society strays from the

sexual ethic of marriage, it deteriorates and eventually disintegrates,'' the

African Christian Democratic Party said.

Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town Njonggonkulu Ndungane, whose church has been

riven by a dispute between African and western congregations over the issue of

homosexuality, said the church ``valued diversity'' as expressed in the court

ruling but would not change its stance against gay marriage.

``We have repeatedly affirmed that we do not regard partnership between two

persons of the same sex as a marriage in the eyes of God,'' Ndungane said in a

statement.

South Africa Court

Removes Barriers to Same-Sex Marriages, NYT, 1.12.2005,

http://www.nytimes.com/reuters/international/international-safrica-gay.html

Man who fed farmhand to lions jailed for life

September 30, 2005

The Times

By Jenny Booth and agencies

A white farmer convicted of feeding one of his black workers

to lions was jailed for life by a South African judge today.

Mark Scott-Crossley, 37, a white building contractor, and farm labourer Simon

Mathebula, 43, were found guilty in April of murdering Nelson Chisale, whose

bloodied remains were found last year in an enclosure for rare white lions near

the Kruger National Park. Little more than his skull, shards of bone and a

finger were recovered.

The incident was apparently sparked by a dispute between the deceased and his

then employer Scott-Crossley.

The grisly killing of 41-year-old Mr Chisale provoked an outcry in South Africa

where, more than a decade after the end of apartheid rule, some white farmers

are still accused of abusing and exploiting black workers. Protesters demanding

life sentences for Scott-Crossley and his co-accused have picketed some sittings

of the court.

The state also called for life imprisonment for both men, citing the

exceptionally gruesome nature of the crime that took place on January 31, 2004

near Hoedspruit, in north-east South Africa. But although Judge George Maluleke

of the Phalaborwa circuit court sentenced Scott-Crossley to life imprisonment,

he gave Mathebula 15 years, of which three years were suspended.

Scott-Crossley, who minutes earlier married one of his prison visitors at a

nearby courthouse, showed no emotion as the sentence was read out at the

hearing.

"We did expect a heavy sentence," he told journalists following the sentencing.

"We are sorry that the family didn’t accept our offer of financial compensation.

It was not an effort to try and bribe them, but we really feel sorry for them,

and we are going to fight the sentence."

About 100 people packed in the courtroom cheered and ululated after the sentence

was read, while Chisale’s niece Fetsang Jafta declared "I’m satisfied with the

outcome."

During the trial that opened in Phalaborwa in January, a year after the murder,

a judge heard that Chisale was savagely beaten with pangas at Engedi farm where

he had returned to collect his belongings, two months after being fired for

apparently running a personal errand during work hours.

Chisale was tied to a tree and later loaded onto a pick-up truck and driven to

the Mokwale White Lion Project where he was thrown over a fence into a lion

camp.

Farm worker Robert Mnisi, who was accused along with Scott-Crossley and

Mathebula but later turned state witness, testified that he heard Chisale scream

as the lions devoured his body.

A third accused, Richard Mathebula, who is apparently suffering from

tuberculosis, will face trial separately due to ill health.

The start of the sentencing hearing was delayed for 30 minutes as Scott-Crossley

tied the knot with Sim Strydom, whom he met just a few weeks ago when she

visited him in prison, adding an unexpected twist to the saga.

Before handing down the sentence, judge Maluleke said his ruling was based on

the severity of the crime and not on the presumption that it was a racist

killing.

"The racial undertones in this case did not play a role in the conviction,"

Maluleke said. "It will also not play a role in the sentencing."

Membathisi Mdladlana, the Labour Minister, had expressed his "shock" and"anger"

over the murder while the main labour federation said that the killing showed

that many farmers treat black workers today as badly as they did during

apartheid.

In one particularly brutal incident, a white farmer in eastern South Africa was

sentenced to 25 years in 2001 for killing a black employee by tying a rope

around his neck and dragging him along a gravel road behind a pick-up truck.

Man who fed farmhand

to lions jailed for life, Ts, 30.9.2005,

http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,3-1805372,00.html

A Bleak Symbol of Apartheid,

Soweto Sees Signs of

Prosperity

September 9, 2005

The New York Times

By MICHAEL WINES

SOWETO, South Africa, Sept. 6 - They held a wine-tasting

festival here this past weekend, the social event of the month in this sprawling

township of a million-plus people just west of downtown Johannesburg. Among the

1,500 who showed up, Maureen Makhathini of Diepkloof needed a lift to get there.

"My car's in the shop," she explained. "The BMW, I mean."

If something seems wrong with that picture, well, something is. Soweto, after

all, is famous as the hotbed of rebellion in apartheid's dying days - a place of

endless poverty, seething anger and, too often, mindless violence by oppressors

and oppressed alike. Say "Soweto," and educated palates and Bavarian roadsters

do not jump quickly to mind.

That, Mrs. Makhathini says, is what is wrong. "It used to be very, very, very

rough," she said. "Now you can see that it's exactly the opposite."

It is possible to gloss over Soweto's - and South Africa's - many problems. The

rich-poor divide in this nation remains among the widest on earth, and Soweto,

the oldest and biggest township, remains deeply rooted on the poor side of that

gap. The racial divide persists, too, and ordinary Sowetans may not have so much

made peace with their old white oppressors, as they have rendered them

irrelevant to daily life.

But something else is going on here as well. From the ashes of apartheid, Soweto

is emerging as a springboard into the black middle and upper classes, an

economic hub in its own right and, its proponents say, an example to which other

townships can aspire.

"Ten years ago, there was no excitement like there is now," said Mnikelo

Mangciphu, a grocery and dry-goods distributor who has sprung into Soweto's

burgeoning wine market. "There is a drive by the government and by the people to

invest in Soweto. Roads are being tarred, all the infrastructure is being

upgraded, and that on its own encourages more investment."

In fact, Soweto no longer looks like an archetypal township, with its ragtag

collection of concrete block huts and waterless, powerless shacks, but instead

resembles a typical if modest suburb. So-called informal settlements of shanties

account for fewer than one in 10 dwellings; most homes now are made of brick,

and utilities are a given.

Some neighborhoods, Diepkloof and Pimville among them, are now comparatively

high-income areas, with homes and real-estate markets to match. A recent market

study pegged the average household's income at about $4,900 a year - above the

average for black South Africans, and high by African standards in general,

though such statistics can be unreliable.

And while the nation's latest census, from 2001, concluded that the great

majority of Sowetans made less than $12,000 a year, it also found that nearly

20,000 of the 300,000 households made more - some of them hundreds of thousands

of dollars a year, in fact.

Since then the region has embarked on what looks very much like a development

boom.

A $16 million complex that includes offices, shops and a tourist center

commemorating South Africa's Freedom Charter opened in June in Kliptown,

Soweto's historic heart. Richard Maponya, a self-made millionaire in retailing,

broke ground in July on a 650,000-square-foot shopping mall in central Soweto

that he says will be aimed squarely at up-market consumers.

Another consortium announced plans last month for an 18-hole golf course near

Pimville that is being designed by Gary Player, the legendary South African pro,

and will be surrounded by housing. Coincidentally, the announcement follows a

warning by President Thabo Mbeki that such golf estates are gobbling up prime

land, marginalizing the poor and worsening racial divisions.

Caxton Newspapers, a big South African chain, is rolling out 11

free-distribution weeklies in Soweto neighborhoods, written and published by

local residents, to complement the 90 it hands out in white communities.

"They've opened a very large shopping mall in Protea, there's a large mall in

Dobsonville, and one opening in the future in Pimville," Kevin Keogh, the chief

executive of Caxton's urban newspapers division, said, ticking off Soweto

neighborhoods. "That all adds up to advertising dollars."

Local merchants claim to see the changes as well. The Backroom Restaurant in

Pimville, open just four months, does a brisk business serving food, blues and

jazz to upscale patrons, not just from Soweto, where surveys say 4 in 10 workers

are white-collar employees or professionals, but from blacks who have moved out

of Soweto to wealthier suburbs north of the city.

"Our target market is middle class to top end," said the owner, Patrick Mrasi

(pronounced m-GHA-si). "I wanted to create a networking place, one where guys

can come and have their business meetings. A lot of these guys are successful

and live in the suburbs, but they still have families in the township, and even

in the week, after work, they come here. Soweto's where they spend most of their

time."

As a draw, the Backroom has begun offering an extensive list of South African

wines, served by stewards trained by the Cape Wine Academy. "Since I opened,

there's been a nice, steady growth," Mr. Mrasi said. "Nobody would have thought

I could reach these levels."

Some did, actually. Last weekend's wine festival, which showcased the wines of

10 black-owned wineries among the 86 exhibitors, was conceived by Mr. Mangciphu,

the distributor, and the Cape Wine Academy's local manager, Lyn Woodward, over a

cookout at Mr. Mangciphu's Pretoria home. "I was drinking beer out of a glass

from the Soweto Beer Festival" last November, he said, "and so she said, 'Guys,

why don't we have a wine festival?' "

Ten months later, the festival was successful enough that some late arrivals on

Sunday were turned away and the promoters have decided to make it an annual

event. Mr. Mangciphu and Ms. Woodward, with two others, have formed a company to

market and distribute fine wine in Soweto and, later, other townships.

Their target is people like Mrs. Makhathini, a 52-year-old entrepreneur who

seems to have the fingers of each hand in different pies. A dental nurse at a

local hospital, she also runs a dressmaking business from a backyard office,

rents still more space to a hair salon and - in her spare time - run a small

charity for 100 local orphans.

Her latest plan is to add a second story to a house she owns in Pimville, using

the proceeds from rentals to reopen a computer school and begin a

videoconferencing center for Sowetans who want to communicate with friends and

business contacts abroad.

As for wine, Mrs. Makhathini does not often partake. But the festival may change

her mind. "I really had a good time," she said. "Unexpectedly."

A Bleak Symbol of

Apartheid, Soweto Sees Signs of Prosperity, NYT, 9.9.2005,

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/09/09/international/africa/09soweto.html

Des hausses de salaires

ont mis fin à la grève

des mineurs

d'or sud-africains

12.8.2005

Le Monde

CARLTONVILLE (province du Gauteng) de notre envoyée spéciale

Les mineurs n'ont pas le droit de parler aux journalistes !

Dégagez immédiatement ! Vous avez trois minutes pour quitter la propriété !"

Flanqué de deux "gros bras", le responsable de la sécurité de la mine d'or de

Driefontein ne plaisante pas avec les consignes. Sans autorisation de la

direction de Goldfields, aucun étranger n'est admis autour de cette mine, l'une

des plus grandes du pays, située à une cinquantaine de kilomètres au sud de

Johannesburg.

L'accueil est à peine moins froid dans la mine voisine, propriété de l'autre

géant sud-africain, Harmony. Cette fois, ce sont les syndicalistes qui

rechignent à parler. Eux aussi veulent un feu vert de la direction. "Les choses

ont un tout petit peu changé depuis 1994, depuis la démocratie. On est libre, on

a le droit de s'exprimer", tient à souligner Bhongo Mvimvi, membre de la

direction locale de l'Union nationale des mineurs (NUM), qui a organisé du 8 au

11 août la plus grande grève depuis 1987. Pour parler, il faudra tout de même

s'éloigner de quelques kilomètres.

Les mines se ressemblent. Plantées dans les champs, ce sont de véritables

petites villes avec, autour du puits, les terrils, les petites villas des

cadres, les immeubles des mineurs, les terrains de sport et les débits de

boissons. "Dans notre vie quotidienne, franchement, rien n'a changé. On vit

toujours dans les "hostels". C'est ça le plus dur", explique Vincent Skondo, qui

"travaille au fond" depuis vingt-cinq ans. Les "hostels" sont des vestiges du

régime d'apartheid : dans ces baraquements, s'entassaient des mineurs vivant

alors à 15 ou 20 dans une chambre. Il y a dix ans, il y avait encore 530 000

travailleurs dans les mines d'or sud-africaines, aujourd'hui ils ne sont plus

que 110 000.

"Avec les licenciements de ces dernières années, c'est moins peuplé. Il y a huit

personnes par chambre, mais c'est toujours trop. Il n'y a aucune intimité",

ajoute Bhongo Mvimvi. La direction d'Harmony assure que la moyenne est de 4,2

personnes par chambre.

Les salaires des mineurs, qui débutent à 2 200 rands par mois (277 euros), ne

leur permettent pas d'avoir un logement en dehors de la mine. La prime de

logement, l'un des enjeux de cette grève qui a paralysé tout le secteur des

mines d'or pendant quatre jours, vient d'être portée à 1 000 rands par mois,

encore loin des 1 500 rands réclamés par les syndicats.

"On n'a toujours pas le droit de faire venir nos femmes. Alors il y a plein de

prostituées. Comment voulez-vous qu'on lutte contre le sida ?" commente Vincent

Skondo. Il vient de la région du Cap-Oriental, située à des milliers de

kilomètres, et ne rentre voir sa femme et ses sept enfants qu'une fois par an.

Un mineur gagne deux à trois fois plus qu'un travailleur agricole. Mieux

organisés, les syndicats ont déjà obtenu de notables avancées sociales.

Soucieuses de leur image, désastreuse sous l'apartheid, les entreprises minières

ont, de leur côté, consenti quelques efforts. Les mineurs ont désormais une

couverture sociale, des assurances "funérailles", des allocations logement que

d'autres travailleurs leur envient.

A l'issue d'une épreuve de force qui aura duré quatre jours et mobilisé 75 % des

effectifs, les mineurs ont obtenu des augmentations de salaires de 6 % à 7 %.

Les quatre grandes compagnies minières qui se partagent l'essentiel de la

production annoncent des pertes de 16 millions d'euros par jour mais devraient,

selon les experts, s'en remettre. La Bourse de Johannesburg n'a pas bougé, le

rand reste fort face à l'euro et au dollar et les cours mondiaux de l'or n'ont

pas réagi.

Des hausses de

salaires ont mis fin à la grève des mineurs d'or sud-africains, Le Monde,

Fabienne Pompey, Article paru dans l'édition du 13.08.05,

http://www.lemonde.fr/web/article/0,1-0@2-3212,36-679601@51-644650,0.html

South Africa sticks to its guns

January 23, 2005

The Sunday Times

RW Johnson, George

SOUTH AFRICA’S draconian Firearms Control Act, a decisive

attempt to limit gun ownership in a society awash with weapons, has confronted a

gun culture that is every bit as deep as America’s.

It is hard to imagine better representatives of this culture than Piet and

Rossouw Botha, the two sons of former President PW Botha. The first member of

their family to settle in South Africa in 1679 was a gunsmith and many of his

descendants have been involved in the gun trade. Faced by the new law, both men

are talking of emigration.

Piet Botha and his wife carry .40 Smith & Wessons constantly. “She has to drive

past three squatter camps on her way to work,” he says. Both of them are good

shots and spend hours on the shooting range every month.

Piet points out that one of his best friends was shot dead in the garden, that

there have been five attempted burglaries of his Pretoria home, that he has

twice been attacked by muggers in the past few years (he saw them off by pulling

a knife — he carries three knives), that his son was badly beaten by other

muggers and that his son-in-law was nearly killed in another incident.

His son responded to his ordeal by becoming a fully trained gun and knife

instructor and learning martial arts. His daughter, who works in Britain, arms

herself with guns and knives whenever she returns. “In our family it’s always

been the tradition that children learn to handle guns from the age of five or

six and we all belong to shooting clubs,” he says.

Although Piet is a sports shooter too, he says the most important thing is the

defence of his family: “I can’t compromise about that. If I’m forced to give up

my guns here, I’ll emigrate to the UK”.

Reminded that British gun laws are equally tough, he replies: “No problem. There

you have law and order and the police are magnificent. My family will be safe

there without guns.”

Rossouw Botha, who runs the gun shop Redneck Tactical Supplies in the Western

Cape town of George, is only too aware that many gun shops are closing down

because of the new law, which requires weapons in private hands to be

re-registered every five years and, in some cases, every two years.

The regulations are bewilderingly complex and the licensing department is so

slow that at its present rate it will take 65 years to re-register all South

Africa’s 4.5m legally held private guns.

If Rossouw wants to continue to ply his trade, he may have to do it in the

United States. “The guys I really feel sorry for are the poor, mainly blacks,”

he says. “Well-off whites can retreat inside high-walled houses with expensive

alarm systems and security companies offering instant armed response. But 95% of

my customers are black and they can’t afford that.

“They buy my guns but have to leave them in my safe because they can’t get

licences for them. They are all going to be driven into becoming illegal gun

owners.”

Both men are determinedly modern and progressive Afrikaners who insist that they

never supported apartheid in the days before the African National Congress came

to power.

“The ANC is the democratically elected government of this country and that means

its laws have to be respected,” says Piet. “This new gun law is completely

wrong, but I absolutely will not break the law.”

The other side of the argument, put by the Gun Control Alliance, is that South

Africa has the world’s highest murder rate — 11 times higher than America’s.

Between 1994 and 2004 215,000 people were murdered in South Africa — more than

58 a day — and the proportion caused by guns has risen from 41% to half.

For gun control groups, such figures show the absolute necessity of reducing the

number of weapons in circulation and regulating their ownership. The gun lobby

reads them the other way round, pointing out that 51,004 armed robberies were

reported in 1996 and 88,178 by 2000, with huge numbers going unreported.

“The situation is running out of control,” says Abios Khoele, chairman of the

Black Gun Owners’ Association. “The criminals are extremely well armed.

“The ANC smuggled huge numbers of guns into the country and after liberation

made no effort to collect them back. Those same weapons are now often used in

hold-ups.

“We blacks only want arms for self-defence — after all, crime is worst of all in

the townships. The trouble is that the government is clearly targeting white gun

owners and they really aren’t the problem any more. The extremist white right is

dead and buried. It’s criminals — murderers and rapists — who we have to defend

our families against.

“For most of the apartheid period blacks weren’t allowed to own guns and now a

black government is taking away our right to self-defence. Already illegal guns

outnumber licensed weapons by 10 to one in townships, but now the number will

rocket.”

Not only is it easy to smuggle guns into South Africa, but there is a huge

leakage of weapons from the army and police who often sell them at a profit.

Another source is home-made guns, turned out in township backyards.

Although the government says it merely wants to regulate private gun ownership,

critics have suggested that it really wants to end it. In one letter to the Gun

Dealers’ Association the minister for safety and security, Charles Nqakula,

stated: “Licences for firearms should not be granted to private individuals.”

Later attempts to snatch that phrase back have merely left gun owners and

dealers resentful and distrustful.

Like Rossouw Botha, other gun dealers talk of emigration.

“You can buy an AK-47 or an R5 army assault rifle in any taxi queue for £30 or

£40,” says one, who did not wish to be named. “The government thinks it is going

to tame the jungle but it’s going to grow a gun jungle like you’ve never seen.”

It will, he suggests, be the arms equivalent of prohibition in the US, an

enormous boost to arms smugglers and the illegal arms trade, with gun-owning

remaining widespread.

“The criminals are heavily armed. People don’t buy guns for fun, but for

self-defence,” he says. “You can’t legislate against the survival instinct.”

South Africa sticks

to its guns, STs, 23.1.2005,

http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,2089-1452178,00.html

We carried panic alarms

and slept in an anti-rape cage

April 28, 2004

The Times

By Michael Dynes

South Africa's reputation for violent crime is unequalled, one in nine is HIV

positive and poverty and unemployment are rampant. But as he prepares to leave

after five tumultuous years as The Times bureau chief there, this correspondent

explains why he will always find the country seductive

I HAVE SURVIVED cerebral malaria, several doses of amoebic

dysentery and two near-fatal car crashes. I live with my wife and children in a

fortified home inside a fortified compound, under permanent threat from

murderous intruders. We can’t walk or take public transport anywhere for fear of

attack; even when I drive, a carjacker could shoot me for less than £1. One in

nine of the locals has HIV, and there are bent cops, massive unemployment and

grinding poverty, with beggars at every traffic light.

It is, in short, a vision of hell. So why is it that, as I prepare to leave

South Africa after five years to return to England, I have such a gut-wrenching

feeling of loss?

This country is not for the faint-hearted, but somehow it gets to you. There are

the obvious things, of course: the all-year sunshine, the sky that seems to go

on for ever, the beaches, the barbecues, the big house with the huge garden and

the swimming pool. And most of all, there are the people. Our children,

Laurence, 5, and Emilia, 2, have grown up here. Laurence loves to get out his

toy mower and help Sam, the gardener, cut the lawn. He won’t be doing that in

London — there isn’t any grass. Emilia will miss being strapped with a towel to

the back of Winnie, our domestic worker, the way African women traditionally

carry their children, and which she adores. Sam and Winnie have become close

family friends, and we could never afford them in London.

Of course, there have been bad times too. I still remember the day when our

first domestic worker announced that she was seven months pregnant, and was

going to give birth at the same time as my wife, Nicol. At first I thought

nothing of it. Then a South African friend told us it would be too dangerous to

keep her on after she gave birth. “It’s illegal to test employees for HIV,” he

said. “But she ’s from a rural area, and no matter how many times you tell her

not to, she will pick up your child and breastfeed it. Are you prepared to take

the risk that she might infect your child? You have no choice. You have to pay

her off.”

South Africa has the highest HIV rate in the world, so we had little option but

to take his advice. On several occasions since we have read stories in the local

press about domestic workers infecting the children of their employers with HIV.

It was a sobering experience. But then, Africa is not the Home Counties.

In the fortified northern suburbs of Johannesburg, we have become accustomed to

living behind an 8ft remote-controlled gate and sleeping in a special section of

the house with steel bars on the windows and a steel gate in the corridor, known

as an anti-rape cage. We all carry panic buttons so that an armed response team

can be summoned in seconds if there is an intruder. Even Laurence understands

this. “That’s for the baddies when they come, isn’t it Daddy?” he said once.

Nothing dominates dinner-party conversation in Johannesburg like tales of

violent crime. Everyone has a story to tell, and they delight in telling it,

terrifying the tourists, demonstrating how macho and fearless South Africans are

and helping to orchestrate a collective hysteria in the process.

Our own experience was limited. Two intruders broke into the master bedroom

while I was away. Nicol was in the adjoining bedroom putting Emilia to sleep.

She heard a noise, and thought little of it. But for weeks friends and

colleagues bombarded us with the possible horrible consequences had she walked

in on the intruders. By the end of it, I was more frightened of them than the

robbers.

Then one day we woke up to the news that an elderly couple near us had been

killed when someone broke into their house and stabbed them in the head with a

pair of shears. Nicol and I exchanged glances, tried not to panic and went about

our day.

The image this extraordinary, if deeply troubled, country has in Britain as one

of the most dangerous places in the world outside a war zone enrages the South

African Government, which sees this as a legacy of colonialism and apartheid.

Violent crime is only an aspect of South African society. It does not define it.

If it did, no one would ever want to live here, black or white.

There is another side to South Africa, which keeps people here who could leave

if they wanted to, and which pulls back many who have already left. The fact is

that, ten years after the fall of apartheid, South Africa is the powerhouse of

the continent. As one white South African who left and then returned told me:

“This is a dynamic society. Everything is in flux. It’s a society trying to find

its feet. There is no more exciting place to be.”

As representatives of more than 100 governments, including 40 presidents and ten

prime ministers, arrive at the Union Buildings in Pretoria to celebrate the

tenth anniversary of freedom and democracy, it is worth bearing in mind how much

the country has changed in ten years.

Armoured vehicles no longer storm the black townships and fire on impoverished

residents who object to being politically and economically marginalised by a

white-minority government who saw them as sub-human because of the colour of

their skin.

The Government no longer pays scientists to carry out research into

race-specific bacterial weapons, schemes to sterilise the majority black

population, or experiments with such notable contributions to warfare as

chocolates laced with botulinum, cigarettes spiked with anthrax and bottles of

beer adulterated with thallium.

At shopping complexes all over the country, blacks, whites, Coloureds and

Indians casually sit next to each other in restaurants and bars, share a meal, a

drink and a conversation — all of which were once criminal offences. It is hard

to believe that only ten years ago South Africa was a totally segregated and

intolerant society. Today, for the most part, South Africa’s people get along

remarkably well.

Black political leaders periodically remind the white community that a little

over a decade ago they actively or passively supported the violent oppression of

the majority of the black population, turned a blind eye to the apartheid-era

death squads and sanctioned the violent destabilisation of neighbouring black

states. But there hasn’t been a hint of the vengeance that so many whites

feared. White people whinge about affirmative action, falling educational

standards and the lack of job and promotion prospects for their children. But

that’s because the country’s resources are being used to benefit all its people,

not just a privileged white elite. A decade after black majority rule, white

people continue to dominate corporate South Africa.

Afrikaners, the descendants of 17th-century Dutch and French settlers who

account for some 60 per cent of South Africa’s four million white people, and

who erected the edifice of apartheid, complain that their culture and heritage

are under siege. Their language, they say, is disappearing from schools, courts

and government offices, and they feel threatened by affirmative action. But few

whites would seriously argue that South Africa is not infinitely better now than

under white minority rule. Most of those who think otherwise have already left.

Racial tolerance and reconciliation are the official government goals. That has

bred a new climate in which words such as “kaffir” and “coolie” are beyond the

pale. Maids are now called “domestic workers,” and non-whites are respectfully

referred to as “the previously disadvantaged”.

South Africa, for all its shortcomings, is no longer the skunk of the

international community. On the contrary, it is held up as an example of how

apparently intractable violence and conflict can be resolved in an increasingly

volatile and hostile world. The hate, fear and paranoia which characterised the

country in the dying years of apartheid have all but gone. South Africa is now a

much happier and relaxed place in which to live and work.

When Chief Justice Arthur Chaskalson swore in Thabo Mbeki yesterday for his

second five-year presidential term, South Africans celebrated the peaceful

transition from apartheid to democracy at a time when the rest of the world was

convinced a bloodbath was inevitable.

But they are also celebrating a decade of stability under black majority rule,

which has been responsible for a dramatic turnaround in the country’s fortunes,

the revival of the bankrupt apartheid-era economy brought to its knees by years

of sanctions and the lowest rates of inflation and public debt for a generation.

In contrast to the South Africa of a decade ago, today it is getting richer, not

poorer, an achievement for which the ruling African National Congress is rarely

given credit. South Africa is now regarded by the international financial

community as one of the most disciplined of all the emerging markets, with low

labour costs and a potential for economic growth that is among the most

attractive in the world.

The fears of white people who stocked up on canned goods before the first

democratic elections in anticipation of Armageddon now seem ridiculous, as do

the predictions from white alarmists that once the ANC took power it would

nationalise everything, from “swimming pools to children”.

Of course, despite many reasons for optimism, the country’s problems are far

from over. The hopes and expectations of millions of impoverished black people

who believed that the end of white minority rule would bring wholesale

improvements in their wretched lives have not been realised. Unemployment is

increasing, and now stands at more than 40 per cent. Fewer than 7 per cent of

school-leavers each year will find a job in the formal economy.

For most people, life has got harder, not easier, under black majority rule. For

the thriving black middle class, estimated to be up to 15 million people, who

have been in a position to benefit from the transition to democracy, the past

ten years have brought considerable gains. But the same cannot be said for the

estimated 20 million of the country’s 45 million people who live outside the

formal economy.

In the squalid squatter camps or “informal settlements” that have sprung up like

festering boils, millions of people live in conditions of abject poverty, with

little or no sanitation, water or power, and no visible means of support. Having

lived in a tin shack in the Diepsloot squatter camp north of Johannesburg for a

few days, I soon realised that the depths of anger over such conditions is the

gravest threat to the country’s stability.

Few white or for that matter affluent black people ever venture out to visit

these hell holes on their doorsteps. These are the people that residents of the

wealthy suburbs, black and white, have fortified their homes against with all

the latest that security technology can offer. Here, amidst the stench of human

urine and faeces, the fury and despair of the poorest of the poor is palpable.

It is here that South Africa’s answer to Robert Mugabe is most likely to emerge

— a firebrand demagogue who could tap into the festering resentments against

rich white people in their fancy houses, and mobilise millions of landless

peasants to march on the shopping malls and golf courses.

This is where most of the crime comes from. Bringing this vast underclass into

the mainstream of society represents the biggest challenge facing Mbeki in his

second term of office. Unlike the black urban elite which has benefited from a

decade of black majority rule, this seething underclass has little in the way of

education or skills. It is unemployed, and largely unemployable.

It is going to be a Herculean task. Many critics think that it is beyond the

ability of the ruling party, that the country’s social and economic problems are

just too big to be solved. Mbeki does not share such views. He is adamant that

the ANC has done more in ten years to improve the lives of the black majority

than all previous white governments put together. Unemployment, he says, can be

defeated, just like apartheid.

South Africa’s black electorate has just delivered Mbeki and the ruling party

their biggest election victory since Nelson Mandela became the country’s first

black President. Despite the ANC’s failure to rescue millions of them from

poverty and despair, they seem prepared to wait a little longer for it to do so.

After five exhilarating years, our time here is up. Living in South Africa was

always only going to be temporary. We are Europeans, not Africans, and must

return home, despite flirting with the idea of becoming South Africans as some

of our friends have done. It would be fascinating to see if the squatter camps

can be removed from the landscape. That might just be the first step in ending

Africa’s image as the “basket case” continent.

Sitting on the Tube or walking through a London drizzle at some point in the

future, I know that images of South Africa and its people — from the Afrikaner

farmers of the Free State to the impoverished residents of the squatter camps —

will always return to haunt me. Perhaps I will return one day. On the other

hand, perhaps I won’t leave at all . . .

We carried panic

alarms and slept in an anti-rape cage, Ts, 28.4.2004,

http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,7-1089893,00.html

SA newspapers

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2002/feb/05/world-news-guide-africa

https://mg.co.za/

https://www.timeslive.co.za/sunday-times/

Related > Anglonautes > Vocapedia

Apartheid

|