|

History > 2005 > USA > Health

Being a Patient

Doctors' Delicate Balance

in Keeping Hope

Alive

December 24, 2005

By JAN HOFFMAN

Dr. Joseph Sacco's young patient lay gasping

for breath; she had advanced AIDS and now she was failing.

Assessing her, Dr. Sacco knew her medical options amounted to a question of the

lesser of two evils: either the more aggressive ventilator, on which she would

probably die, or the more passive morphine, from which she would probably slip

into death. But there was also a slender chance that either treatment might help

her rally.

He also knew that how he presented her options would affect her decision, the

feather that would tip the balance of her hope scale.

As Dr. Sacco, a palliative care specialist at Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center,

spoke to the woman on that chilly morning earlier this month, her eyes widened

with terror: no intubation. He ordered morphine.

He agonized about his approach. "She's only 23," he said later that day. "Maybe

I was too grim. Maybe I was conveying false hopelessness to her. Maybe I just

should have said, 'Let's put you on the ventilator.' I may have spun it wrong."

The language of hope - whether, when and how to invoke it - has become an

excruciatingly difficult issue in the modern relationship between doctor and

patient.

For centuries, doctors followed Hippocrates' injunction to hold out hope to

patients, even when it meant withholding the truth. But that canon has been

blasted apart by modern patients' demands for honesty and more involvement in

their care. Now, patients may be told more than they need or want to know. Yet

they still also need and want hope.

In response, some doctors are beginning to think about hope in new ways. In

certain cases, that means tempering a too-bleak prognosis. In others, it means

resisting the allure of cutting-edge treatments with questionable benefits.

Already vulnerable when they learn they have a life-threatening disease or

chronic illness, patients can feel bewildered, trapped between reality and

possibility. They, as well as doctors, are discovering that in the modern

medical world, hope itself cannot be monolithic. It can be defined in many ways,

depending on the patient's medical condition and station in life. A dying woman

can find hope by selecting wedding gifts for her toddlers. An infertile couple

moves on toward adoption.

The power of a doctor's pronouncements is profound. When a doctor takes a

blunt-is-best approach, enumerating side effects and dim statistics, in essence

offering a hopeless prognosis, patients experience despair.

A radiation oncologist told Minna Immerman's husband, who had brain cancer, that

he had less than two years to live. "That information was paralyzing," Mrs.

Immerman said. "It wasn't helpful."

But when a doctor suggests that an exhausted patient try yet another therapy, in

the hope that it may extend survival by weeks, the cost is also considerable -

financially, physically and emotionally.

"We have to find a less toxic way to manage their hope," said Dr. Nicholas A.

Christakis, an internist and Harvard professor who is writing a textbook about

prognosis.

Efforts are being made across the medical community to grapple with the language

and ethics of hope. Some medical schools pair students with end-stage disease

patients so students can learn about anguish and compassion.

Numerous studies have examined what doctors say versus what patients hear and

the role of optimism in the care of the critically ill. Patient advocates have

been teaching doctors how patients can be devastated or braced by a turn of

phrase.

A consensus is emerging that all patients need hope, and that doctors are

obligated to offer it, in some form.

To Dr. Sacco's boundless relief, his patient rallied. He began counseling her to

take her AIDS medications, to find an apartment, a job.

He wrote in an e-mail message: "We prognosticate because people ask us to and

trust our judgment. They do not know the depth of our uncertainty or that no

matter how good or experienced we are, we are often wrong. That is why choosing

where to put the feather is so damn hard."

False Hopelessness

Robert Immerman, a 56-year-old Manhattan architect, knew that his brain cancer -

a glioblastoma, Grade 4 - meant terrible news. After the tumor was removed, he

asked the radiation oncologist his prognosis.

"The doctor was pleasant," Minna Immerman recalled, "as if he was telling you

that hamburger was $2.99 a pound. He just said the likely survival rate with

this tumor was, on the outside, 18 months.

"Bob purposely forgot it," she said. "I couldn't."

After radiation, Mr. Immerman began chemotherapy. But after one treatment, his

white blood cell count dropped so precipitously that it was no longer an option.

"The medical oncologist said, 'The chances of survival with or without chemo are

very, very slight,' " said Mrs. Immerman, a special-education teacher. "I think

she was trying to make us feel better. What I heard was: 'With or without chemo,

this won't end well, so don't feel so bad.' "

Mr. Immerman got scans every two months. Mrs. Immerman watched the calendar

obsessively. Twelve months left. Six months. "As time passed, instead of feeling

better, I felt like it was a death sentence and it was winding down," she said.

She sweated the small stuff: should they renew their opera subscription?

Mr. Immerman turned out to be one of those rare people who reside at the lucky

tail end of a statistical curve. In February, it will be 10 years since he

learned his prognosis. He is well. For years, Mrs. Immerman was shadowed by fear

and depression about his illness, before she finally allowed herself to breathe

out with gratitude.

Candid exchanges about diagnosis and prognosis, especially when the answers are

grim, are a relatively recent phenomenon. Hippocrates taught that physicians

should "comfort with solicitude and attention, revealing nothing of the

patient's present or future condition." A dose of reality, doctors believed,

could poison a patient's hope, the will to live.

Until the 1960's, that approach was largely embraced by physicians. Dr. Eric

Cassell, who lectured about hope in November to doctors in the Boston area,

recalled the days when a woman would wake from surgery, asking if she had

cancer:

" 'No,' we'd say, 'you had suspicious cells so we took the breast, so you

wouldn't get cancer.' We were all liars." Treatments were very limited. "Now

when we're truthful," Dr. Cassell added, "it's in an era in which we believe we

can do something."

Doctors in many third world countries and modernized nations, including Italy

and Japan, still believe in withholding a bad prognosis. But the United States,

Britain and other countries were revolutionized in the late 60's by the

patients' rights movement, which established that patients had a legal right to

be fully informed about their medical condition and treatment options.

Now, whether a patient comes in complaining of a backache, a rash or a lump in

the armpit, many doctors interpret informed consent as the obligation to rattle

off all possibilities, from best-case to worst-case situations. Honesty is

imperative. But what benefit is served by Dr. Dour?

"There are doctors who paint a bleaker picture than necessary so they can turn

out to be heroes if things turn out well," said Dr. David Spiegel, a

psychiatrist at Stanford medical school, "and it also relieves doctors of

responsibility if bad things happen."

The fear of malpractice litigation after a bad outcome, he said, also drives

doctors to be stunningly explicit from the outset.

The medical community has nicknames for this bluntness: truth-dumping, terminal

candor, hanging crepe. But some social workers call it false hopelessness.

Given a time-tied prognosis, many patients become withdrawn and depressed, said

Roz Kleban, a supervising social worker with Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer

Center. "Telling someone they have two years to live isn't useful knowledge,"

she said. "It's noise. Whether or not that prediction is true, they lose their

ability to live well in the present."

Health care providers debate the wisdom of giving patients a precise prognosis:

"There's an ethical obligation to tell people their prognosis," said Dr. Barron

Lerner, an internist and bioethicist at Columbia University medical school, "but

no reason to pound it into their heads."

Others say that doctors should make sure they can explain the numbers in

context, with the pluses and minuses of treatment options, including the

implications of choosing not to have treatment.

Though many patients ask how long they have to live, thinking that amid the

chaos of bad news, a number offers something concrete, studies show that they do

not understand statistical nuances and tend to misconstrue them. Moreover,

though statistics may be indicative, they are inherently imperfect.

Many doctors prefer not to give a prognosis. And, studies show, their prognoses

are often wrong, one way or the other.

Where does this leave the frightened patient?

Meg Gaines, director of the Center for Patient Partnerships, a patient advocacy

program at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, thinks false hopelessness is

more debilitating than false hope.

"I tell people to ask the doctor, 'Have you ever known anyone with this disease

who has gotten better?' If the answer is yes, just say, 'So let's quit talking

about death and talk about what we can try!' "

Some patients do triumph against grotesque statistical odds; others succumb even

when the odds are piled in their favor.

But willful ignorance, she cautioned, can be dangerous.

"People should know about prognosis to the extent that it's necessary to make

good decisions about monitoring your health care," she said. "You can't be an

ostrich in the sand. When the stampeding rhinoceri are coming, you have to be

able to get out of the way."

False Hope

Perhaps just as harmful as false hopelessness, many experts believe, is false

hope. "If one patient in a thousand will live with pancreatic cancer for 10

years," said Dr. Christakis of Harvard, and doctors hold out that patient as a

realistic example, "we have harmed 999 patients." False hopelessness, in the

name of reality, dwells on the dark view of a patient's condition, prematurely

foreclosing possibility and a spirited fight. False hope sidesteps reality,

leaving patients and family members unprepared for tragedy.

When Anna Kyle was in labor, the umbilical cord dropped ahead of the baby, who

was deprived of oxygen for critical moments. Mrs. Kyle had an emergency

Caesarean section. The baby had to be resuscitated.

The nurses in the neonatal intensive care unit told Mrs. Kyle, of Lonoke, Ark.,

that her son was a "good baby," because he didn't cry or fuss. Later, when he

had developmental delays, her hopes were at war with her nagging fears. But

doctors kept saying the child might outgrow them.

Her son, now 5, received a formal diagnosis last year. "Nobody wanted to say,

'Your kid has autism, your kid is mentally retarded, your kid will be in diapers

most of his life,' " said Mrs. Kyle, whose husband earns $10 an hour as a truck

driver. "It hurts, it's nasty, ugly stuff, but it has to be said, so kids can

get the therapy they need as early as possible."

Because patients hunger for good news, experts say that doctors should choose

their words carefully: "If you get into the language of hope, you run the risk

of over-promising things," said Dr. Lerner of Columbia.

The more useful discussion for patients, he added, is, "what hopeful things can

I do?"

In his November lecture on hope, Dr. Cassell said that patients do not need

"false hope that is personified in useless therapy with nontherapeutic effect."

False hope is both a hangover from the centuries-old belief that doctors should

withhold bad news, and a practice newly infused by the explosion of so many

medical treatments and the tenuous promise held out by clinical trials.

Consider the cost of false hope, experts note: not only the physical and

emotional agony of dying patients who try last-ditch, occasionally unproven

treatments, but also the depletion, financially and psychologically, of the

patients' survivors.

"The battle cry of our culture is, 'Don't just stand there - do something!' "

said Dr. Richard Deyo, a Seattle internist and professor at the University of

Washington who writes about the high cost of false hope.

He added, "Physicians have a natural bias for action, whereas it may be more

honest to say, 'Whether I do something or not, the result is likely to be the

same.' "

A 1994 study showed that Americans have greater faith in medical advances than

people in many other countries. Thirty-four percent of Americans believed that

modern medicine "can cure almost any illness for people who have access to the

most advanced technology and treatment." By contrast, only 11 percent of Germans

held the same belief.

Accompanying the medical advances, however, are an increasing number of

physician subspecialties. One downside is that patients hear from a variety of

voices, and they can become inadvertently misled.

Pat Murphy, a nurse and grief counselor who heads the family support team at

University Hospital in Newark, said that, for example, when a patient has a

critical stroke, a cardiologist, among others, will be called in for an

evaluation: "The doctor might say, 'This is a strong heart' and then he leaves,"

she said. "The patient will probably never regain consciousness. But the 'parts

people' talk to the family out of context, and the family thinks they're hearing

good news."

Another result of this medical renaissance is thousands of clinical trials.

Phase 1 trials often try out doses of an unapproved drug; perhaps only 5 percent

of volunteers may derive any benefit. "Most people think they don't want to be

an experiment," said George J. Annas, author of "The Rights of Patients." But,

he said, when desperately ill patients learn about a trial, "all of a sudden

there's no difference in their minds between research and treatment."

A 2003 study of advanced-stage cancer patients who volunteered for Phase I

trials showed that at least three-quarters of them were convinced they had a 50

percent chance or greater of being helped by the drug.

Because patients listen selectively, it can be difficult to tease out who owns

responsibility for false hope:

Patricia Mendell, a New York psychotherapist who works with fertility patients,

noted: "A doctor can tell a patient she has a 95 percent chance of an I.V.F.

cycle not working. But the patient will feel it's her right to try for that 5

percent. "

Indeed, false hope can represent a complex entwining between terrified patient

and well-intended doctor: both want the best outcome, sometimes so intensely

that what emerges is a collective denial about the patient's condition.

Hope

Elissa J. Levy was a winter sports jock, with a buoyant social circle and a

power job on Wall Street. But in January 2002, she received a diagnosis of

secondary progressive multiple sclerosis, a less common version of the disease,

for which there are few treatments and no known cures.

Soon, Ms. Levy needed a cane, and could scarcely walk a block. Pain and fatigue

dogged her. Her quick brain grew foggy, her right hand floppy. She cut back her

new job as a deputy director of a Bronx charter school to three days a week. In

the mornings, her mother had to help dress her.

But though her body sagged, her neurologist helped prop up her spirits. "Often I

would come in crying," Ms. Levy said, "and he would hold my hand and say, 'We'll

figure this out together.' Or 'We can hope that this treatment works.' "

Given the gravity of her disease, was it appropriate for the doctor to stoke her

hope?

"Hope," wrote Emily Dickinson, "is the thing with feathers/That perches in the

soul."

Imprecise and evanescent, hope is almost universally considered essential to the

business of being human.

Few can define hope: Self-delusion? Optimism? Expectation? Faith?

And that, say experts from across a wide spectrum, is the point: hope means

different things to different people. When someone's medical condition changes,

that person's definition of hope changes. A hope for a cure can morph into a

hope that a relationship can be mended. Or that one's organs will be eligible

for donation.

For so many, hope and faith are inextricably linked. "Truly spiritual people are

amazing, " said Ms. Murphy of University Hospital. "Until the moment of death,

families pray for a miracle and then at the moment of the death, they say, 'This

is God's will' and 'God will get us through this.' "

As health care providers struggle with whether, how and when doctors should

speak of hope, a consensus is building on at least two fronts: that what

fundamentally matters is that a doctor tells the truth with kindness, and that a

doctor should never just say, "I have nothing more to offer you."

More doctors are embracing palliative care specialists as partners who work with

critically ill patients and their families to help them redefine their hopes,

from the improbable to the possible. Many doctors, whose specialties range from

neurosurgery to infertility, retain therapists to counsel patients.

"Hope lives inside a patient and the physician's behavior can either bring it

out or suppress it," said Dr. Susan D. Block, a palliative care leader at

Harvard. "When a patient has goals, it's impossible to be hopeless. And when a

physician can help a patient define them, you feel like a healer, even when the

patient is dying."

Dr. Spiegel, the Stanford psychiatrist, recalled a woman who knew her death from

cancer was imminent: "She had 15-minute appointments scheduled all day with

relatives, to set them straight on how to live their lives. Then she was going

to die. This was a hopeful woman."

Harvard's medical school matches first-year students with critically ill

patients - in essence, the patients become the teachers. One patient, Dr. Block

recalled, was a high school teacher dying from lymphoma, who agreed with

alacrity to participate. When her husband came into her room, the patient said,

with tears in her eyes, "Honey, I have one last teaching gig."

Last April, Ms. Levy's doctor started her on a drug that is still in clinical

trials, but has long been available in Europe. Shortly after she began taking

the daily pill, she went for a checkup and lay down on his examining table.

He asked her to lift her leg.

Normally, Ms. Levy struggled to budge her leg. But having taken the drug, she

flung her leg into a 90-degree angle. She gasped.

Usually, when her doctor pressed one finger against her leg, it collapsed. Now

he pushed with his open hand. She held steady. Both she and her doctor grew

teary-eyed.

Finally, she walked down the hall without her cane. Both patient and doctor wept

openly.

The drug does not cure her disease; it treats symptoms. But Ms. Levy, 37, now

walks 20 blocks at a clip, works four days a week, goes to the gym. She is

dating. A recent test showed that her disease has not progressed.

In a sense, Ms. Levy's relationship with her doctor combined the best of the old

and new worlds. He was hopeful but also candid. And he could offer her promising

treatments, including one that, at least temporarily, seems to help.

"And if I start feeling bad again?" Ms. Levy said. "I have hope that I'll feel

good again."

Doctors' Delicate Balance in Keeping Hope Alive, NYT, 24.12.2005,

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/24/health/24patient.html

Health

Care for All, Just a (Big) Step Away

NYT

18.12.2005

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/18/business/yourmoney/18view.html

Economic View

Health Care for All,

Just a (Big) Step Away

December 18, 2005

The New York Times

By EDUARDO PORTER

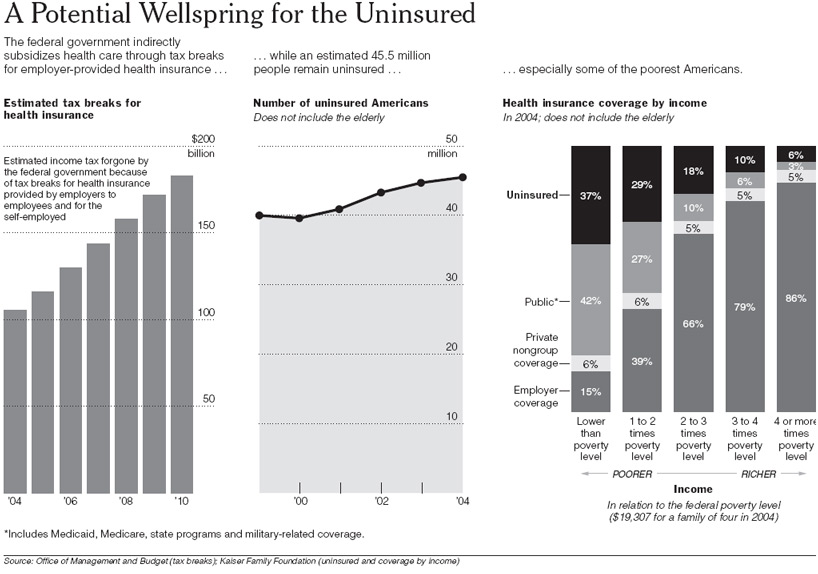

YOU may find it shameful that some 45 million Americans

lack health insurance. Well, by reallocating money already devoted to health

insurance, the government could go along way toward solving the problem. But you

may not like the solution.

Next year, the federal government expects to provide about $130 billion for

Americans to buy health insurance. The amount is substantial: it is equivalent

to about 11 percent of all federal income tax revenue and more than a fifth of

federal spending on Medicare and Medicaid. And it is growing fast: the bill is

expected to surpass $180 billion in 2010.

Nonetheless, this financing remains under the political radar because it is

provided indirectly - not as direct spending but as a tax break that allows

workers to receive health insurance coverage from their employers without having

to pay income taxes on whatever it costs.

This provides a powerful incentive to businesses all over the country. The

subsidy - supplemented by an additional $11 billion in deductions for medical

expenses and billions more in similar tax breaks for health insurance from

states and municipalities - helps to explain why 64 percent of Americans under

65 get health insurance through their employers.

Although subsidizing health insurance may seem a worthy effort, a positive

contribution to the goal of universal coverage, it is among the most inefficient

spending in the nation's fiscal arsenal.

"If you had $150 billion to play with, you could come very close to universal

coverage," said David Cutler, an economics professor at Harvard. One reason that

we are 45 million people short of that goal is that the money isn't being spent

on them.

According to President Bush's advisory panel on tax reform, about half of the

tax break for health insurance accrues to families making more than $75,000 a

year. More than a quarter goes to families making over $100,000.

These families would surely hate to lose the subsidy. For a family making

$100,000 a year in, say, Los Angeles, the tax break cuts the cost of

employer-provided health insurance by about 35 percent in federal and state

income taxes. On a typical family policy costing $11,500 a year, that is

equivalent to some $4,000.

Still, the fiscal incentive isn't helping many of the people who need it most. A

report by the Kaiser Family Foundation says two-thirds of the 45.5 million

Americans who lacked health insurance in 2004 earned less than twice what the

federal government defines as poverty. (For a family of four, the poverty line

is about $19,300.) In four of every five cases, the uninsured made less than

three times the poverty level.

In addition to going to the wrong people, the subsidy as designed promotes

wasteful medical spending, encouraging the wealthy to buy more insurance and to

use more health services than they need, according to the president's tax panel.

And it may bolster premiums across the board.

Altogether, the health insurance tax break exacerbates America's medical

dystopia: while the nation has the highest per-capita spending on health in the

world - about $5,400 in 2002 - 18 percent of the population under 65 remains

uninsured.

As part of a series of proposals to rejigger the tax code, the president's tax

panel issued a report earlier this year that suggested capping the total that

can be paid in pretax dollars at an amount equal to the average health insurance

premium in the country: some $11,500 for a family.

But if the objective is to expand health care coverage, a bolder option is

available: focusing the bulk of the money on the bottom end of the income

distribution.

Added to what is already spent on Medicaid, this financing would be roughly

enough to make health insurance free for people earning up to three times the

poverty level, and perhaps somewhat more, said Jonathan Gruber, an economics

professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who has studied the

efficiency of alternative methods for financing health insurance.

To make insurance universal, two other things would be needed, Mr. Gruber said.

As soon as the tax break was eliminated, company-provided health insurance would

be likely to disappear, too. So some mechanism would be needed to pool groups of

people and to avoid leaving higher-risk people to face enormous insurance costs.

Such a mechanism would probably make health insurance affordable for all. And to

make it universal, a mandate would be needed to make people buy it.

This isn't communism. The changes could happen under a public health care system

or one that is privately run.

The new universal insurance could be provided by government. One simple way

would be to extend Medicaid coverage up to the desired income level and to

require people above that point to buy into the system according to a price

scale that rose proportionately to income.

Because Medicaid has lower administrative costs than private insurance, this

would be efficient. But the new regime could be run privately as well, to take

advantage of the private sector's superior track record on innovation.

The government could give tightly focused tax credits so that lower-income

people could buy health insurance on the market. And it could organize pools by,

say, requiring insurers to charge the same for similar policies sold to people

of the same age group who live in the same area.

Regina E. Herzlinger, a professor of business administration at Harvard Business

School, notes that the Swiss have such a system: privately provided health

insurance priced by age and residence and subsidized at low incomes. This, she

said, gives the Swiss top-notch health services, universal health insurance and

a medical bill that tops out at 10 percent of the nation's output, compared with

15 percent in the United States.

SOME of these ideas are beginning to gain traction in America, too.

Massachusetts is considering a law that would make health insurance mandatory.

It would expand Medicaid to cover families in the state that make less than

twice the poverty level and offer tax credits on a sliding scale up to four

times the poverty line. It would also provide for creation of insurance pools

for people who don't get coverage through employers.

This health care revolution, however, is unlikely to catch on nationally anytime

soon. For starters, losing the tax break on employer-provided health insurance

would be tremendously disruptive for the millions of Americans who get their

insurance through their jobs. Perhaps most important, it would force

higher-income families to buy health care without the tax break; that idea is

probably as politically suicidal as abolishing the mortgage tax deduction.

"I don't think anybody would dispute the economics," Mr. Gruber said. "I think

the dispute would be over the politics."

Health Care for

All, Just a (Big) Step Away, NYT, 18.12.2005,

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/18/business/yourmoney/18view.html

Being a Patient

Sick and Vulnerable,

Workers Fear for Health

and Their

Jobs

December 17, 2005

The New York Times

By LISA BELKIN

When Marty Domitrovich was first told that he had cancer,

he was a 51-year-old sales executive, so successful that he had two goals: to

reach $1 million in commissions and bonuses and to become chief executive of his

company, where he had worked since his summers in college.

Before long, however, he could no longer travel, and on the bad days he did his

work at home, lying on the couch and talking on the telephone.

When Shannon Abert was first told she had scleroderma, she was 35, and loved her

job teaching high school algebra. Until her illness was diagnosed, she was

healthy and active, never taking a sick day from work, not even bothering to

find a doctor who accepted her school district's insurance plan. Her disease

progressed quickly, though, and soon she could not write on the blackboard, pull

students' files or turn the classroom doorknob.

Work takes on many meanings when illness strikes: a cause of added stress; a

place to escape from that stress; a source of income, insurance, identity and

normalcy; and a fear of losing all those and more.

Both Mr. Domitrovich, now 58, and Ms. Abert, now 38, wanted to keep working

after their conditions were diagnosed, and both asked their employers for help.

One was told, "We'll give you whatever you need." The other recalls facing much

more ambivalence, with one administrator telling her, "We all have problems,

just do the job."

In this way, their stories reflect the realities of being ill in today's

workplace, at a time when sick workers have more legal safeguards than ever

before, and yet also face gaps, inconsistencies and question marks in those

laws. Yes, how an employee is treated after crossing the stark line from worker

to patient is broadly defined by legislation. But it is more specifically

determined by things like the culture of a workplace and the sensitivity of a

boss.

"We've come a million miles from the bad old days," said Robin Bond, who runs an

employment law firm in Wayne, Pa., and represents individuals with claims

against employers. "But no law changes the basic fact that employers want to do

what's good for business. Their job is not necessarily to do what is good for

you."

At a time when a worker is most physically and emotionally vulnerable, the

person must also adroitly navigate to protect himself or herself.

"I didn't want to worry about work, but work was all I worried about," Ms. Abert

said of the months after her illness was diagnosed in 2003. "I had to keep my

insurance. I had to pay my rent.

"When you're sick," she said, "trying to get out of bed every day, that's the

worst time to have to worry about your job, but you have no choice."

Double Jeopardy: Health and Job

Whether an employee enters a job with a diagnosed disability or becomes impaired

after being hired, the worker faces the decision of whether and when to tell the

employer. It is a choice loaded with emotion, and also with ramifications under

the law.

"The diagnosis is a crisis in itself," said Carolyn Messner, an oncology social

worker and director of education and training for cancer care in Manhattan. "The

next crisis is telling people."

Mr. Domitrovich announced his devastating news almost immediately after he

received it on Jan. 1, 2000. As vice president of sales and a regional manager

for Cutco/Vector, which sells and manufactures cutlery, he was based in Chicago

but traveled constantly.

When he began experiencing gastrointestinal symptoms in 1999, it was impossible

to keep his team from noticing that something was wrong. He said he did try not

to let word spread beyond that small group, however, because "as a leader you

don't want to show too many of your weaknesses."

Soon the symptoms became more severe, and tests found an neuroendocrine islet

cell tumor in the pancreas. The cancer had already spread to his liver.

Mr. Domitrovich told his wife and grown children first; then, within days, he

informed the chief executive of the company and his close staff. The company's

yearly banquet for the regional sales team was held two weeks later, and he

shared the news in a brief speech to the 700 people who attended.

Ms. Abert, in contrast, kept her misery to herself. Her first symptoms appeared

in the fall of 2002, when her fingers began turning purple, as if she had

frostbite, but she knew that was unlikely in Clear Lake, Tex., near Houston.

An internist theorized that she had developed carpal tunnel syndrome from

writing math equations on the board, and gave her wrist splints, which only made

the problem worse. The pain spread to her legs and toes, but she did not tell

her principal because she did not want to be seen as a weak link. It was stress,

she reassured herself. It would go away.

It did not, and eventually, in January 2003, at the end of her school's winter

vacation, a rheumatologist confirmed that Ms. Abert had scleroderma, a chronic

connective tissue disease in which the body attacks itself, leading most

noticeably to hardening of the skin. Now it was not pride, but fear and a need

for privacy, that kept her quiet.

On the one hand, she was still absorbing all that was happening to her and she

was not ready to share that exquisitely personal process with the world. At the

same time, she did not know whether her job was in jeopardy and she was too

afraid of the answer to ask the question. Besides, if her supervisors and

colleagues knew, she was certain her students would find out as well, meaning

she would lose the authority a teacher must have to command a classroom.

"I can't look at them and say, 'Y'all, I'm not feeling well,' " Ms. Abert said.

"They will wreak havoc."

This instinct for privacy is common, said dozens of employees, employers,

lawyers, health care providers and patient advocates interviewed for this

article.

"I don't want to be labeled as the sick person, where all people see is the

disease," says Tecela Harris, 38, who told only a version of the truth at a job

interview for State Farm Insurance more than a decade ago, not mentioning that

she had rheumatoid arthritis, which made her joints swell horribly and caused

constant pain.

"They told me the job was for claims adjuster and it included climbing up on

roofs," Ms. Harris recalled. "When they asked, 'Are you going to be able to do

that?' I said I could do it."

The result was years of agony until, needing to take 70 days off to recuperate

from foot surgery to correct damage from the disease, she finally revealed her

illness to her boss in 2000.

"I was almost in tears," during that conversation, said Ms. Harris, who is now

on a recently approved medication that leaves her free of pain. "My illness was

not something I was proud of, so I didn't really want to share that."

And yet, while patients might prefer to keep silent, the law favors disclosure.

Two pillars of legislation have come to define the rights of ill workers in

recent years: the Americans With Disabilities Act, passed in 1990, requiring

employers to make "reasonable" accommodations for disabled or seriously ill

workers, as long as they can perform the "essential" functions of the job; and

the Family and Medical Leave Act, passed in 1993, allowing workers to take up to

three months off from work without losing their health insurance or job.

Under each, employers are only obligated to help employees whose conditions are

known to them. A worker who regularly misses work for chemotherapy treatments,

but does not explain why, can be dismissed for absenteeism and cannot then

appeal on grounds of disability.

That creates a dilemma that is equal parts emotional and tactical.

"I advise workers not to tell their employer, unless they want to ask for

accommodation because of a disability," said Sharona Hoffman, a professor at

Case Western Reserve University School of Law and an expert on the legislation.

"If you want to invoke the protection of the law, then you have to tell."

A Plan to Stay Alive

Mr. Domitrovich armed himself for his early conversations with a business plan.

He would never tackle a new business challenge without a plan, he said, and this

was a new business challenge. Among his goals were to "stay alive long enough to

find a cure" and to "see granddaughter go to grade school."

He told his bosses that he was certain he could keep working through his

treatment, meeting sales projections. "I believe my team can produce, even

though I'm not there every day," he remembers saying.

Sales positions at Cutco/Vector are paid solely on the basis of commissions and

incentive bonuses, so his own income along with that of his staff was on the

line.

For six months, Mr. Domitrovich was able to work with little trouble. The

medication he was taking had few side effects and succeeded in restricting the

growth of his tumor.

But eventually the mass began to press on his biliary duct, requiring surgery to

insert a stent to relieve the pressure. Then the cancer began growing faster. He

entered a clinical trial, which slowed the growth, but by then years of toxic

medication had damaged his gallbladder, which had to be removed.

Through all this, he did meet his sales goals. His team's revenues increased 25

percent in 2001 and another 38 percent in 2002, which is the year he reached his

$1 million income goal. (He also saw his granddaughter start kindergarten last

year.)

But the toll of work and treatment was heavy, and he decided that he could not

keep up the pace.

Before Mr. Domitrovich could tell his bosses of that decision, though, they made

one of their own. They announced a restructuring, increasing four sales regions

to six, and effectively eliminating his job. They suggested another role that he

might play: running the Fair and Show program, which coordinated cutlery sales

at places like local fairs and conventions. It was an important part of the

business, but it would require travel, which he knew he could not do.

When his disease was first diagnosed, Mr. Domitrovich joined a support group of

cancer patients, and over the months, he said, he heard "the horror stories."

The man with cancer of the jaw who had to take out a second and third mortgage

on his home when he lost his job after his family medical leave time ran out.

The man with stomach cancer who was told that his company would "stand behind

you 100 percent," then let him go within six months.

So Mr. Domitrovich did not turn down the new job right away. Instead he asked

for some time to think about what work he would like to do next.

'I Am So Sick, I Can't Make It'

Scleroderma patients have a particularly hard time getting out of bed in the

morning, possibly because muscles stiffen and weaken overnight. Ms. Abert lived

alone in the months after she became ill, and she had no one to help her with

morning buttons and zippers. Each night she would take a sedative so she could

sleep in spite of the pain, and even though she went to bed at 8 p.m., she was

often late for the start of class at 7:30 a.m.

Her students noticed, she said, just as they noticed the ulcers on her fingers

and the steady weakening of her hands. She could not get the caps off the

markers for the dry erase board. Even screwing the top off a bottle of water

meant asking a student for help.

But still Ms. Abert maintained the facade of health, until the fall of 2003,

when the weather turned colder and she finally hit bottom.

It was the time of year when the forms arrived for her to choose her benefit

options for the next 12 months. She read carefully, but when she found nothing

about long-term disability, she assumed she did not have that option.

A search of the Internet found information about the Family Medical Leave Act,

including the fact that the three months of leave were unpaid, and then neither

her job nor her health insurance were protected.

She could not imagine how she would cope under those circumstances. Still, she

thought, maybe a few months off would help her regain some energy. So she

dragged herself to the human resources department, where she recalls telling a

counselor, "I don't think I can do this anymore. I am so sick, I can't make it

day to day."

His initial answer, she says, was: "You don't look sick. We're all tired. Hang

in there."

"He kept saying 'It has to be measurable, you need documentation, it has to be

something that can be measured,' " Ms. Abert said of Steven Austin, the director

of employment benefits and risk management for the school district.

While Mr. Austin agreed that he probably did explain the need for documentation

("You have to provide certification for medical leave," he said in an

interview), he said he did not believe that he said anything harsher than that.

He concedes, however, that others in the district may well have said such things

to Ms. Abert.

"There wasn't a lot of support for her" from her superiors, Mr. Austin said,

adding that he wondered whether her memory had put someone else's words in his

mouth.

Most in Need, Most at Risk

The Catch-22 of the American health care system is that while many people work

"for the insurance," when they become too sick to work and are most in need of

that insurance, they are most at risk of losing it.

This is particularly true of workers at small companies, which are not covered

by existing law. (The Family and Medical Leave Act, for instance, only applies

to workplaces with 50 or more employees.)

One employee at such a company, who asked that her name not be used because she

feared retribution from her former boss, learned the significance of this

distinction the hard way when she had a brain tumor removed five years ago. Her

employer, she said, "told me that my tumor came at a really bad time for the

company."

The woman had recently received a significant raise, $20,000. Her workplace was

small - about a half-dozen employees - and a few months after her illness was

diagnosed, the group's insurance premiums jumped. "My raise was rescinded, to

cover the increase," she said.

Experts fear that as insurance rates increase, even companies large enough to be

constrained by law will make personnel decisions based on the cost of health

care. Those costs, which were stable during most of the 1990's, have increased

at double-digit rates for the past three years, said Glenn Melnick, a professor

of health economics at the University of Southern California.

Dr. Melnick thinks it is not coincidence that this environment led Wal-Mart,

whose health costs increased 15 percent last year, to suggest what a

confidential internal memorandum to the board of directors called "bold steps."

If the company took action to "dissuade unhealthy people from coming to work at

Wal-Mart," the widely leaked memorandum said, the potential savings would be

$220 million to $670 million by 2011.

The proposed method of dissuasion, as explained in the memorandum, was to define

every job so that it included some form of physical activity ("e.g., all

cashiers do some cart gathering"). Unfit people would be less likely to apply

and if they did apply, the company could legally refuse them because they could

not do the job as described.

There is similar "wiggle room" in laws requiring employers to provide

"reasonable accommodations" for employees, and here, too, experts are concerned.

"The key word when talking about accommodations is 'reasonable,' " said Ms.

Bond, the employment lawyer. "And the employer gets to define that word."

If employers remain overwhelmed by health care costs, they may see this as an

incentive to play hard ball, Ms. Bond and others fear, hoping that employees

with health problems will just give up and go away, taking their expensive

illnesses with them.

Navigating the Obstacle Course

Mr. Domitrovich suggested to his bosses that it was time that he left sales,

stopped traveling and became a mentor. The result was "Cutco/Vector University,"

a management training program run by Mr. Domitrovich. His salary is only a

fraction of his former commissions, but he maintains his insurance.

"We wanted to do whatever we could for Marty," said Bruce Goodman, chief

executive for Vector sales and president of Vector West. "Marty is the

conscience of our company."

Cutco/Vector might not be able to make similar arrangements for every ill

employee, Mr. Goodman said, "but in Marty's case there truly was never any

consideration of should we fire him, should we put him out to pasture."

Ms. Abert, in turn, tried to stay at work. She became vocal about her condition

after her meeting with human resources, and she asked the maintenance staff to

change the doorknobs on the teachers lounge and on her classroom so that she

could open them more easily.

In the spring of last year, Ms. Abert's hands became seriously infected and she

was hospitalized for much of the spring. Since then, she has been on long-term

disability, which is a benefit available to every district employee, even though

it was not in her packet of paperwork.

She will receive 80 percent of her income until she is 65, but she will not

receive insurance indefinitely. Her district policy has already lapsed, and she

will pay $498 a month under COBRA until that too expires, next September.

Her unexpected ally in navigating the system was the same human resources

counselor who seemed so brusque at their first meeting. "Once he saw I was

really sick, he did everything he could to help," she said of Mr. Austin, to

whom she now turns for advice.

Most recently, he told her not to return to teaching part time. If she did, the

pay would be less than what she now receives on disability, though it would

include insurance, making the equation temporarily worth it. But, he said, were

she to require disability again, she would only be eligible for 80 percent of

her part-time pay.

Ms. Abert has considered trying to return full time, but she cannot figure out a

way to fit her regimen of doctor's appointments into a teaching schedule.

"I can't close the classroom door and say 'I will be back in an hour,' " she

said. "It's difficult being sick as a teacher. I guess it's difficult being sick

in any job."

Sick and

Vulnerable, Workers Fear for Health and Their Jobs, NYT, 17.12.2005,

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/17/health/17patient.html

Terri Schiavo's case

doesn't end with her passing

Posted 3/31/2005 10:16 AM

Updated 4/1/2005 7:49 AM

USA TODAY

By Larry Copeland and Laura Parker

PINELLAS PARK, Fla. — Terri Schiavo, the brain-damaged

woman at the center of a bitter legal battle that prompted extraordinary action

from Congress and the White House and focused national attention on end-of-life

issues, died Thursday.

Schiavo suffered severe brain damage in 1990 after her heart stopped because of

a chemical imbalance.

Getty Images

She was 41. Her death came 13 days after a feeding tube that kept her alive for

15 years was removed. Schiavo's final two weeks involved multiple court appeals.

Over the years, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to intervene in the case six

times, most recently Wednesday. Hundreds of protesters camped outside the

hospice here where she was a patient. (Related video: Years in the courts)

By the time she died at 9:05 a.m. ET, the case was an international story. The

van transporting her body to the Pinellas County medical examiner's office was

shown live on TV. An autopsy will be performed.

Even the Vatican got involved. Shortly after her death, Cardinal Jose Saraiva

Martins, head of the Vatican's office for sainthood, called the removal of the

feeding tube "an attack against God." (Related story: Reaction at the Vatican)

President Bush said Thursday, "The essence of civilization is that the strong

have a duty to protect the weak." His brother, Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, who pushed

hard to intervene, said, "Her experience will heighten awareness of the

importance of families dealing with end-of-life issues, and this is an

incredible legacy."

The case spurred public interest in living wills, which allow people to spell

out whether they want to be kept alive by artificial medical means. "No question

that people's awareness across the country, if not the world, has been raised by

this case," said Howard Krooks, a lawyer in White Plains, N.Y.

First lady Laura Bush this week told reporters that she and the president have

living wills, as do their parents. "I think that is important for families to

have opportunities to talk about these issues," she said.

Schiavo had no living will. Her husband and parents fought in court over what

she would have wanted after she suffered brain damage in 1990 when a chemical

imbalance caused her heart to stop. Florida courts ruled she was in a persistent

vegetative state.

The family dispute could continue. Her husband, Michael, has court permission to

have his wife cremated and to inter her ashes in Pennsylvania, where the couple

grew up. Her parents want her buried in Florida.

The feud between the parents, Bob and Mary Schindler, and their son-in-law

continued even after her death: The Schindlers' spiritual advisers said the

couple had been at their daughter's bedside minutes before the end came, but

were not there at the moment of her death because Michael Schiavo did not want

them in the room.

Michael Schiavo was at his wife's bedside, cradling her, when she died a "calm,

peaceful and gentle" death, said his attorney, George Felos. Her parents, Bob

and Mary Schindler, were not at the hospice at the time, he said.

"Mr. Schiavo's overriding concern here was to provide for Terri a peaceful death

with dignity," Felos said. "This death was not for the siblings, and not for the

spouse and not for the parents. This was for Terri." (Related audio: Felos

comments on passing)

In Tallahassee, Florida legislators observed a moment of silence marking

Schiavo's death.

"This is not only a death, with all the sadness that brings, but this is a

killing, and for that we not only grieve that Terri has passed but we grieve

that our nation has allowed such an atrocity as this and we pray that it will

never happen again," said the Rev. Frank Pavone, another spiritual adviser for

the Schindlers. (Related audio: Pavone talks of final moments)

"She's got all of her dignity back. She's now in heaven, she's now with God, and

she's walking with grace," Michael Schiavo's brother, Scott Schiavo, said at his

Levittown, Pa., home.

Terri Schiavo suffered severe brain damage in 1990 after her heart stopped

because of a chemical imbalance that was believed to have been brought on by an

eating disorder. Court-appointed doctors ruled she was in a persistent

vegetative state, with no real consciousness or chance of recovery.

The feeding tube was removed with a judge's approval March 18 after Michael

Schiavo argued that his wife told him long ago she would not want to be kept

alive artificially. His in-laws disputed that, and argued that she could get

better with treatment. They said she laughed, cried, responded to them and tried

to talk.

During the seven-year legal battle, Florida lawmakers,

Congress and President Bush tried to intervene on behalf of her parents, but

state and federal courts at all levels repeatedly ruled in favor of her husband.

The case focused national attention on living wills, since Schiavo left no

written instructions in case she became disabled.

After the tube that supplied a nutrient solution was disconnected, protesters

streamed into Pinellas Park to keep vigil outside her hospice, with many

arrested as they tried to bring her food and water. The Vatican likened the

removal of her feeding tube to capital punishment for an innocent woman. The

Schindlers pleaded for their daughter's life, calling the removal of the tube

"judicial homicide."

Although several right-to-die cases have been fought in the courts across the

nation in recent years, none had been this public, drawn-out and bitter.

But federal courts refused again and again to overturn the central ruling by

Pinellas County Circuit Judge George Greer, who said Michael Schiavo had

convinced him that Terri Schiavo would not have wanted to be kept alive by

artificial means.

Six times, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to intervene.

Schiavo's fate was debated on the floor of Congress and by President Bush, the

governor's brother, who signed an extraordinary bill March 21 that let federal

judges review her case.

House Majority Leader Tom DeLay, R-Texas, appeared to condemn judges who at both

the state and federal level declined to order that Schiavo be kept alive

artificially.

"This loss happened because our legal system did not protect the people who need

protection most, and that will change," the Texas Republican said. "The time

will come for the men responsible for this to answer for their behavior, but not

today. Today we grieve, we pray, and we hope to God this fate never befalls

another."

Described by her family as a shy woman who loved animals, music and basketball,

Terri Schindler grew up in Pennsylvania and battled a weight problem in her

youth.

"And then when she lost all the weight, she really became quite beautiful on the

outside as well. What was inside she allowed to shine out at that point," a

friend, Diane Meyer, said in 2003.

She met Michael Schiavo at Bucks County Community College near Philadelphia in

1982. They wed two years later. After they moved to Florida, she worked in an

insurance agency.

But recurring battles with weight led to the eating disorder that was blamed for

her collapse at age 26. Doctors said she suffered severe brain damage when her

heart stopped beating because of a potassium imbalance. Her brain was deprived

of oxygen for 10 minutes before she was revived, doctors estimated.

Because Terri Schiavo did not leave written wishes on her care, Florida law gave

preference to Michael Schiavo over her parents. But the law also recognizes

parents as having crucial opinions in the care of an incapacitated person.

Michael Schiavo and the Schindlers jointly supervised care for Terri after she

collapsed. For the first 16 days and nights that she was hospitalized, Schiavo

never left the hospital. Over the next few years, as she was moved from the

hospital to a skilled nursing facility, to a nursing home, to Schiavo's home and

finally back to a nursing home, Schiavo visited Terri daily.

Schiavo and the Schindlers even sold pretzels and hot dogs on St. Pete Beach to

raise money for Terri's care. But everything seemed to change on Valentine's Day

1993 in a nursing home near here.

In 1992, Schiavo had filed a medical malpractice lawsuit against two doctors who

had been treating his wife before she was stricken. Late that year came a

settlement: Schiavo received $300,000 for loss of consortium — his wife's

companionship. Another $700,000 was ordered for Terri's care.

Mary Schindler later testified that Schiavo had promised money to his in-laws.

They had helped him and Terri move from New Jersey to Pinellas County, let them

live rent-free in their condominium and had given him other financial help.

"We all had financial problems" after Terri's crisis, she testified. "Michael,

Bob. We all did. It was a very stressful time. It was a very financially

difficult time. He used to say, 'Don't worry, Mom. If I ever get any money from

the lawsuit, I'll help you and Dad.' "

By February 1993, Schiavo had the money from the lawsuit.

On Valentine's Day that year, he testified, he was in his wife's nursing home

room studying. He wanted to become a nurse so he could care for his wife

himself. He had taken Terri to California for experimental treatment. A doctor

there had placed a stimulator inside Terri's brain and those of other people in

vegetative states to try to stimulate still-living but dormant cells.

According to Schiavo's testimony, the Schindlers came into Terri's room in the

nursing home, spoke to their daughter, then turned to him.

"The first words out of my father-in-law's mouth was how much money he was going

to get," Schiavo said. "I was, 'What do you mean?' 'Well, you owe me money.' "

Schiavo said he told his in-laws that all the money had gone to his wife — a lie

he said he told Bob Schindler "to shut him up because he was screaming."

Schiavo said his father-in-law called him "a few choice words," then stormed out

of the room. Schiavo said he started to follow him, but his mother-in-law

stepped in front of him, saying, "This is my daughter, our daughter, and we

deserve some of this money."

Mary Schindler's account of that evening is far different. She testified that

she and her husband found Schiavo studying. "We were talking about the money and

about his money," she said. "That with his money and the money Terri got, now we

could take her (for specialized care) or get some testing done. Do all this

stuff. He said he was not going to do it."

She said he threw his book and a table against the wall and told them they would

never see their daughter again.

The accounts of that confrontation came in testimony during a January 2000

hearing on a petition Schiavo filed to discontinue his wife's life support.

Pinellas County Circuit Judge George Greer ruled the next month that the feeding

tube could be removed.

Despite the row over money, Schiavo and the Schindlers agreed on one major point

in the 2000 testimony: the extent of Terri's brain damage, according to

additional court documents cited by The Miami Herald. In the documents, Pamela

Campbell, then the Schindlers' lawyer, told the court that "we do not doubt that

she's in a persistent vegetative state." Campbell could not be reached to

confirm the statement.

At this point, however, the gulf between Schiavo and the Schindlers could not be

bridged.

"On Feb. 14, 1993, this amicable relationship between the parties was severed,"

Greer wrote. "While the testimony differs on what may or may not have been

promised to whom and by whom, it is clear to this court that such severance was

predicated upon money and the fact that Mr. Schiavo was unwilling to equally

divide his loss of consortium award with Mr. and Mrs. Schindler."

Schiavo's feeding tube was briefly removed in 2001. It was reinserted after two

days when a court intervened. In October 2003, the tube was removed again, but

Gov. Jeb Bush rushed "Terri's Law" through the Legislature, allowing the state

to have the feeding tube reinserted after six days. The Florida Supreme Court

later ruled that law was an unconstitutional interference in the judicial

system.

Nearly two weeks ago, the tube was removed for a third and final time.

Contributing: USA TODAY's Richard Willing and Jill Lawrence, USATODAY.com's

Randy Lilleston and The Associated Press.

REACTION TO THE DEATH

"It is with great sadness that it's been reported to us that Terri Schiavo has

passed away." — Paul O'Donnell, a monk who acted as a spokesman for the woman's

parents.

"She can finally be at peace after 15 years." — Sister-in-law Karen Schiavo.

"Today, millions of Americans are saddened by the death of Terri Schiavo. Laura

and I extend our condolences to Terri Schiavo's families. I appreciate the

example of grace and dignity they have displayed at a difficult time. I urge all

those who honor Terri Schiavo to continue to work to build a culture of life." —

President Bush.

"After an extraordinarily difficult and tragic journey, Terri Schiavo is at

rest. I remain convinced, however, that Terri's death is a window through which

we can see the many issues left unresolved in our families and in our society.

For that, we can be thankful for all that the life of Terri Schiavo has taught

us." — Florida Gov. Jeb Bush.

"Their faith in God remains consistent and strong. They are absolutely convinced

that God loves Terri more than they do." — Attorney David Gibbs III, describing

her parents, Bob and Mary Schindler.

"She was starved and dehydrated to death ... Her sickness has triggered a huge

national health debate in our country." — Rev. Jesse Jackson.

"Terri Schiavo is now a martyr. Her death is not in vain." — Florida Rep. Dennis

Baxley, who sponsored the bill in the Florida House that aimed to restore her

feeding tube.

"Congress in a bipartisan fashion took up Terri's cause and met in extraordinary

session to provide Terri with an opportunity for a new, full, and fresh review

in federal court of her right to receive life-sustaining treatment. Regrettably,

this effort did not receive the court review the law requires." — U.S. House

Judiciary Committee Chairman James Sensenbrenner Jr.

"An attack against life is an attack against God, who is the author of life." —

Portuguese Cardinal Jose Saraiva Martins, head of the Vatican's office for

sainthood.

Source: Associated Press

Terri

Schiavo's case doesn't end with her passing + Reaction to the death,

UT,

31.3.2005,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2005-03-31-schiavo_x.htm

|