|

History > 2006 > USA > Demographics (I)

Ideas & Trends

The Bell Tolls

for the Future Merry Widow

April 30, 2006

The New York Times

By KATE ZERNIKE

MEN are catching up to women in the life

expectancy game; the National Center for Health Statistics reports this month

that the gap between them has shrunk to five years, the narrowest since 1946. If

current trends continue, in 50 years men and women will live the same length of

time.

This is better news for men than for women, if you believe some economists and

therapists. It's not just the extra years; it's all those extra meals to

prepare.

By necessity, women have gotten used to a life lived for long periods without

men. They have had the advantage in life expectancy since the late 19th century,

when overall longevity started to climb. More than men, women have developed

strong friendships to support them in their frailest hours. They have forced

doctors to pay attention to their health concerns. They no longer have to cater

to men. Travel companies now cater to their interests.

"Women don't need men as much as men need women," said John Gray, the therapist

and author of, most famously, "Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus."

But for all that, consider how women would be better off.

Men living longer means women are less likely to suffer the fate that Miranda

from "Sex and the City" so feared: dying alone with only the cat to rake over

her rotting bones. With the existing gap, women are more likely than men to be

widowed 71 percent of people over the age of 85 are women, and the majority of

them will have been married. And being alone increases their risk of dying or

getting sick. No one is there to help when they fall; they eat less, and poorly.

"Even given the limited capacity of men, having a surviving spouse is going to

mean that women do not go as early to nursing homes when they have chronic

illnesses," said Ronald D. Lee, an economist and the director of the Center on

the Economics and Demography of Aging at the University of California, Berkeley.

And a shorter widowhood means women will be better off financially, largely

because, as Heidi Hartmann, a labor economist and the president of the Institute

for Women's Policy Research, said, "Money attaches to the men."

Men, typically the higher wage earners, get bigger Social Security checks. And

if the couple is living on his checks alone, she gets less when he dies. The

surviving spouse's cost of living is about 80 percent what the couple's was,

economists estimate, but the Social Security payments decline to about 65

percent.

Men are much more likely to have pensions, too, leaving women dependent on them,

and one-third of men, Ms. Hartmann said, do not leave theirs to their wives.

(That number used to be higher, she said, until wives were required to sign off

on the deal.)

But men and women growing old together is not always easy.

"Men have this expectation that women should take care of them," Dr. Gray said.

"And she has her own expectations, that she should be there for him."

Particularly after retirement, she is not used to having him around quite so

much. "It's different taking care of him for dinner, as opposed to him being

home all the time, and expecting her to make every meal," Dr. Gray said.

Though some may object to the assumption that sex roles will be this traditional

by 2040, recent studies have shown that among husbands and wives who both work,

the woman still does the much larger share of the housework. As one Connecticut

woman in her 70's was heard to retort recently when her husband asked if they

were ready to move to an assisted-living facility, "You've had assisted living

for 40 years."

This dynamic is reflected in the statistics: men are four times as likely as

women to remarry after the death of a spouse, experts on aging say. (Men who

divorce also remarry faster; within three years, compared with nine for women.)

They're looking for love, Dr. Gray said, but they're also looking for lunch.

Marriage lowers everyone's risk of death, Professor Lee said, but the benefits

go mostly to men; women lower their risk only slightly by marrying. Similarly, a

man's risk of death increases sharply after the death of a spouse; a wife's does

only negligibly.

"Women are very helpful for men," he said. "Men are not very helpful for women

as spouses."

Women not only do fine despite a spouse's death, they may even do better.

"In married couples, women tend to be the ones who manage the social sphere,"

said Laura L. Carstensen, a professor of psychology at Stanford University and

director of the Life-span Development Laboratory there. "They're the ones who

make dinner plans and invite friends over for weekends. So a man loses a social

network, whereas a woman continues to make plans and see people."

People have traditionally felt sorry for older widows, thinking they had so few

prospects for remarrying, she said. The truth is, they may not want to remarry.

"They're the ones taking care of everyone; they've often taken care of a frail

husband, and doing it again isn't necessarily appealing."

Then there are the disputes over sex. Dr. Gray said a woman's sex drive

increases as she ages, while a man's declines. But then, is Viagra upsetting

that balance, putting men in retirement homes permanently on the prowl?

On that count, at least, things may even out. And that may be true over all.

"There is a lot of poverty among older single women, so if men live longer,

that's good economically, for women and men," Ms. Hartmann said. "Men are

generally happier when they're married. The women may not be happier, but at

least they've got more money."

The

Bell Tolls for the Future Merry Widow, NYT, 30.4.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/30/weekinreview/30zernike.html

New York Population Loss

Is Linked to Cost

of Housing

April 20, 2006

The New York Times

By SAM ROBERTS

The 1990's exodus to other states from

California and from the Northeast appears to have eased since 2000, but not in

metropolitan New York, a Census Bureau analysis says.

The Midwest is still losing residents, and the West is gaining. The South

remains a magnet for migrants, but the influx of new residents has declined

steeply outside the South Atlantic region.

The analysis, which is being released today, looked only at people moving from

one place to another in the United States and did not take into account people

arriving from other countries.

Maine, Rhode Island, Maryland and Wyoming, which lost population to other states

in the 1990's, have gained residents from elsewhere in the country since 2000.

In five other states Indiana, Minnesota, Utah, Mississippi and Oklahoma the

pattern was reversed: more people moved out than in from other states.

William Frey, a demographer with the Brookings Institution in Washington,

attributed much of the pattern to soaring housing costs.

"In effect, the housing affordability crunch in metro New York is a windfall for

nearby areas like Allentown and Poughkeepsie and Southern hot spots like Tampa

and Orlando," he said. "And on the West Coast, it's interior California and the

rest of the West that is gaining."

In California, on average, 221,000 more people moved out every year than moved

in from other states in the 1990's. From 2000 to 2004, the annual average net

loss declined to 99,000 as more Californians moved inland from cities on the

coast instead of moving to other states. San Bernardino has gained more migrants

annually since 2000 than any other metropolitan area.

"It's the next frontier," said Marc J. Perry, who wrote the Census Bureau

analysis.

About 183,000 more people left New York State annually than moved in from other

states from 2000 to 2004, fewer than in the 1990's but nearly as many as the

191,000 residents Florida gained annually.

Florida ranked third in the highest rate of domestic migration, relative to its

population, after Nevada and Arizona.

In the bureau's broadly defined New York metropolitan area, which ranges into

northeastern Pennsylvania, but does not include Connecticut, the average annual

loss to domestic migration has risen from 191,000 in the 1990's to 211,000 since

2000.

Mr. Perry cited another contributing factor in New York: the mobility of

immigrants who arrive from abroad and later move elsewhere.

"In the New York area, the pool of new immigrants at risk of moving somewhere

else is much bigger than it was," he said.

Some of those foreign-born migrants might also have been motivated by housing

costs.

"There's much more of a consciousness now that 'if I move to such and such a

place, I can get a house or a much bigger house,' " he said. "Those who leave a

high-cost area are those who are cashing out and those who never cashed in."

Recent census estimates suggest that immigration the engine driving New York

City's population growth appears to have slowed slightly, contributing to a

small decline in the city's population in the year ended July 1, 2005. But the

city's demographers, who successfully challenged earlier census undercounts, say

their figures show that the city's population as of last July was about 8.2

million, the highest on record.

The average annual rate at which the New York metropolitan area lost migrants

since 2000 was surpassed by metropolitan San Francisco and was nearly equaled by

the rates in the Boston and Los Angeles metropolitan areas, where housing is

also expensive.

The gains in Rhode Island and Maine were attributed, in part, to the expanding

borders of the Boston suburbs.

Another reason for moving is the availability of jobs. The flight from

California to other states in the 1990's was accelerated by reversals in the

aerospace and military industries.

On average, Los Angeles and Cook County, Ill., which includes Chicago, each lost

more than 94,000 domestic migrants annually since 2000, the most of any

counties.

In New York City, the counties that make up the five boroughs, except for Staten

Island, were also among the top 25 counties with large annual population losses.

But only Brooklyn and Queens, each of which lost 55,000 annually to other

states, also made the list with the highest rates of population loss.

Geary County, Kan., and Chattahoochee County, Ga., topped counties with the

average annual rate of population loss to migration, with more than 40 per

1,000.

In the Northeast, the net loss from migration has dipped from an average 314,000

in the 1990's to 247,000 since 2000. In the Midwest, the annual number more than

doubled, from 75,000 to 161,000.

The West has gained 55,000 migrants a year since 2000, compared with 7,000 in

the 1990's. In the South, the influx of residents has declined modestly, from

380,000 in the 1990's to 353,000 a year since 2000.

New

York Population Loss Is Linked to Cost of Housing, NYT, 20.4.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/20/us/20census.html

USA records largest drop

in annual deaths

in at least 60 years

Updated 4/19/2006 9:54 PM ET

USA TODAY

By Rita Rubin

The U.S. population may be aging, but the

number of Americans who died in 2004 represents the biggest one-year decline

since World War II, according to preliminary government data released Wednesday.

Nearly 50,000 fewer Americans died in 2004

than in 2003, according to data based on about 90% of U.S. death certificates.

The preliminary number of U.S. deaths in 2004 was 2,398,343, compared with

2,448,288 in 2003.

The last decline this large occurred in 1944, when there were about 48,000 fewer

deaths than in 1943, says Arialdi Minlead author of the report.

"We were surprised. We were scratching our heads," says Minino, a statistician

at the National Center for Health Statistics. "Something of this magnitude is

really out of the ordinary." U.S. deaths usually rise each year, he says, adding

that the last decline occurred in 1997, when 445 fewer Americans died than in

1996.

The drop in deaths was accompanied by a slight rise in life expectancy at birth,

and the 2004 preliminary estimate reached a record high of 77.9 years, about 5

months higher than in 2003, Minino says.

It's not clear why there was such a big drop in 2004, he says. Minino says he

and his colleagues suspect a mild flu season might be one of many converging

factors. Better treatments and improved access to health care are among the

possible contributors to the decline, he says.

The age-adjusted death rate declined greatly for 10 of the 15 leading causes of

deaths, according to the preliminary data. One of the biggest drops, 6.4%, was

in the death rate for heart disease, the No. 1 killer.

Wayne Rosamond, chair of the American Heart Association's Statistics Committee,

says the U.S. death rate from heart disease has been declining each year since

1968.

Over the past 20 years, the decline has averaged 2% or 3% a year, says Rosamond,

an epidemiologist at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. The decline

is a result of a combination of better prevention and improved treatment, he

says.

The decline in the death rate from heart disease "is good news," he said. "We

hope it continues."

The life expectancy for whites 78.3 was up only slightly from the previous

year. The increase for blacks was larger, with a rise from 72.7 to 73.3.

Contributing: The Associated Press

USA

records largest drop in annual deaths in at least 60 years, UT, 19.4.2006,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/2006-04-19-death_x.htm

Not Far From Forsaken

April 9, 2006

The New York Times

By RICHARD RUBIN

It is as you imagine it: Vast. Open. Windy.

Stark. Mostly flat. All but treeless. Above all, profoundly underpopulated, so

much so that you might, at times, suspect it is actually unpopulated. It is not.

But it is heading there.

In our national consciousness, America is a land of perpetual growth. But for

the past half-century or more, much of the middle of the country has been

slowly, quietly emptying out. A few people left, then more and more, until it

started to resemble an organized exodus. For a while, it looked as if the area

might indeed one day resemble the Great American Desert it was mistakenly

labeled on early maps.

That didn't happen. At some point, throughout middle America, the population

hemorrhage stopped, bottomed out.

But not here, in North Dakota. North Dakota has continued to lose people. And it

didn't have that many to begin with. In 1930, its population peaked at 680,845.

In 2000, it was down to 642,200, and by 2004, the last year for which statistics

are available, it had dropped to 634,366. (By comparison, the national

population more than doubled, to 294 million from 123 million, during the same

period.) Of the 25 counties nationwide that lost the largest portions of their

populations in the 1990's, 12 were in North Dakota.

Statistics are ethereal. For tangibles, all you have to do is drive the long,

straight roads in the northwestern part of the state, the ones that run roughly

parallel to the old railroad tracks and the Canadian border: Highway 5, Highway

50, U.S. 2. You won't pass many cars; depending upon where you're driving, and

when, you may not pass any at all for a half-hour or more. What you will pass,

in no small numbers, are the things left behind in the exodus: Abandoned houses.

Empty stores. Churches without congregations. Community buildings gone dark.

Closed schools, never to reopen.

Wry North Dakotans have suggested that such sights are now so common that they

should perhaps be represented in the state seal. All of them, that is, except

for the schools. No one jokes about those. Empty houses and stores and community

halls and even churches are signs of a fading past; empty schools are signs of a

fading future.

But even as the American small town continues what often seems like an

irresistible decline, some in northwest North Dakota are mounting a resistance,

an organized effort to draw people new people, young people, families to

their small towns. And a few have taken things even further by reviving, in a

fashion, the very institution that generated them in the first place:

homesteading.

In 1862, Abraham Lincoln signed into law the Homestead Act, which ultimately

gave away 270 million acres of American land, one 160-acre parcel, or "quarter

section," at a time, to virtually anyone who agreed to build a permanent

dwelling on it and spend at least five years living there and otherwise

"improving" it. The act took effect at midnight on Jan. 1, 1863; the first claim

was filed a few minutes later. But it would be another 40 years before people

started homesteading in earnest in northwest North Dakota. When they did, the

greatest number of them came from Norway, where, folks like to say, the soil was

also frozen and the neighbors were also distant. This is true, but that didn't

make homesteading any easier, not here. People, a lot of them, froze to death or

starved or died of some ailment en route to the nearest doctor, who was often a

day's ride away or more. A lot more perceived at some point that their choices

came down to leaving or dying. They chose to live and left. The majority of

those who filed claims did not last long enough to "prove up" those claims.

But some did. They stayed, they farmed, they married and started families and

subsisted, and some of them even thrived. Towns sprang up, their locations

usually chosen by the railroads, which sometimes chose their names too. People

opened shops. They built churches and schools and, often, good

community-oriented Scandinavians that they were, music halls and dance halls and

fellowship halls and opera houses.

In 1862, when the Homestead Act was passed, a quarter section was considered to

be about as much land as a farmer could be reasonably expected to work alone,

given the state of technology. It wasn't easy, but people managed to live off

that quarter section. Farmers grew wheat as a cash crop and raised chickens and

cows and hogs to feed themselves. Loyd Olin, a farmer who is now 90 and lives in

Crosby, N.D., can recall a time when "there was someone here on every quarter"

that is, when every quarter section in the area had a different family living on

it and off it. He was one of them, raised on land homesteaded by his parents.

The years of his youth, the 1920's, are seen today as North Dakota's golden era,

a time when towns grew and prospered, when the opera houses actually had operas

and the dance halls were packed on Saturday nights, when the schools were full

of children and every town had an amateur baseball league and when a lot of them

had movie houses and newspapers and doctors and dentists and when the bigger

ones like Crosby, the seat of Divide County, had several groceries and

mercantile stores, several car dealerships and farm-implement dealerships and

banks and several competing grain elevators.

Then came what Olin calls the "dry years," the decade commonly known here as the

Dirty 30's. The drought that produced the Dust Bowl farther south hit North

Dakota too, and many farmers who survived the first hard years of homesteading

could no longer hang on. "That's when so many people left here," Olin says. "You

could buy a quarter of land for six, seven hundred dollars. But there was no

banks to borrow money from."

Those who could somehow get the money bought the quarters their neighbors gave

up on, consolidating them into much larger farms that, with more modern

technology, could be worked in the same time, at the same cost, as a much

smaller farm. Producing a larger crop at a lower cost, they were able to sell it

for less and thus drive down prices for everyone else. Eventually, it became

impossible for a farmer to survive on a quarter section. Those who couldn't

expand left; those who stayed bought up the abandoned acres and enlarged their

own farms further, forcing prices even lower. As the cycle continued, the

population plummeted. In 1930, the population of Divide County was 9,636. By

2004, it had fallen to 2,208, a decline of 77 percent.

That was when David Olson, Divide County's director of economic development, hit

upon an idea that he hoped might reverse that trend before it was too late.

Olson discovered that the town had assumed ownership of five housing lots for

back taxes; what if, he thought, instead of selling them at auction, the town of

Crosby gave the lots away to people who would move there, build houses on them

and stay a while, maybe longer? Not as a bribe, really, or even much of a

financial incentive, since the lots were not worth much, but rather, as Olson

explains, "more of a nice gesture, to welcome people." Yet something else was

already going on in the area, and it soon infused those five little nice

gestures with a mission: to entice young people from other parts of the country

to pick up and move to northwest North Dakota, settle down, start families and

fill those empty schools again.

In 2002, a few businessmen and civic boosters got together and founded the

Northwest North Dakota Marketing Alliance. It was formed in the belief that the

region with the exceptions of Minot, the state's fourth-largest city and home

to a major Air Force base, and Williston, a town of about 12,000 was in danger

of someday emptying out entirely and that the best way to prevent that would be

to attract young men and women from other parts of the country, young men and

women who would fall in love with the land and the people and the lifestyle and

put down roots here and create a new generation, and future generations, of

northwest North Dakotans.

For the first year or so, that idea was about all they had. Then in 2003 Steve

Slocum joined the effort. Slocum, who is 52, was born in Montana but grew up in

Williston and is as fervent and tireless an ambassador for North Dakota as you

are likely to meet. Marketing is Slocum's game he works as a marketing

director for a local bank in Williston and he felt he had a great product to

sell. People who see northwest North Dakota for the first time, he says, "are

blown away by the average-guy-on-the-street hospitality." The product, he says,

"is the people it's the sense of community."

Bernie Arcand, who is 58 and works for a telecom company in Ray, N.D., a town of

about 500 some 35 miles northeast of Williston, agrees. North Dakotans, he says,

are "superfriendly, to where you say they're borderline nosy. A real tight sense

of community." And even though he says so in his capacity as secretary of the

Marketing Alliance an unpaid position, like every other one in the

organization you need only spend a day or two in the area to see that he may,

in fact, be understating the case. While there is no scientific apparatus for

measuring such a thing, northwest North Dakotans might just be the friendliest

people in America. It is rare, very rare, to pass someone on the road without

receiving at least a finger wave, regardless of whether or not they have ever

seen you or your car before. A stranger walking down the street of a small town

will not only be smiled at but also approached and actually engaged in genuine

conversation. And a stranger stopping into a small-town bar will be hailed

instantly as an honored guest, even after he explains that he only came in to

use the restroom.

So why would anyone ever leave? "It's a great place to raise your kids," Arcand

says. "But once the kids are graduated from college, there are no dang jobs for

them." And the prospects of attracting large companies, the kind that might

create a few hundred jobs and help lure those kids back home, are, he says,

pretty poor, for a reason that should otherwise be a point of great pride. "Our

unemployment rate is so low" 3.4 percent statewide, among the lowest in the

nation "if I were a businessman, I'd be reluctant to invest millions in a

company here, knowing that there's no one to hire here."

This, then, is the problem: you have a great place with a lot to offer clean

air, good neighbors, low cost of living, very little crime, great pheasant

hunting, etc. but no jobs. How, then, do you get someone to move there? And

not just any someone not, for instance, only retirees, some of whom, drawn by

those same selling points, have already come. How do you attract the folks you

really want, young people who will start families?

If you view it that way that is, as a problem of long-distance,

special-circumstance matchmaking the most logical place to turn is the

Internet. And so in 2003 Slocum helped create PrairieOpportunity.com, a new kind

of online personal State Seeks Residents.

"Do you have what it takes to be a 21st-century pioneer?" the home page asks.

"Odds are," it continues, "you are not a candidate for NW North Dakota. You have

succumbed to the cities. All of your pleasure must be provided, and you gladly

stand in long lines to receive them. But if you are one of those who is

wondering what they are doing in that line, continue on." That page links to

another, titled "What It Takes," which is really just a list of selling points

like "We have front doors that are usually locked only at night or while on

vacation" and "We have businesses that know your first name and use it" and "We

have milk cartons without pictures of children." But, as another page warns:

"This is a very tough and unforgiving country to be waltzin' in because you are

fed up with traffic. . .you need to make sure you can pay your bills without

relying on NW North Dakota to provide you with an income. We have very low

unemployment, and the folks up here expect everybody to pull their own weight.

To support this philosophy, our convenience stores have the little penny bowls

by their tills with a small sign by them reading: 'If you need a penny, help

yourself. If you need two pennies, get a job."'

The Web site lists 86 eligible towns and communities in northwest North Dakota,

though by its own accounting nearly half of them are either unincorporated or

ghost towns. Visitors to the site are invited to fill out and submit a

questionnaire. Slocum says the site typically attracts about 20 "good" e-mail

inquiries a week.

It is tough to say, exactly, how many families have actually picked up and moved

to northwest North Dakota since all this began. There are no statistics, only

anecdotes, and very few of those. Steve Slocum can list a few families, but even

he gets a little fuzzy on whether all of them have actually moved to the area or

merely intend to at some point. One thing he can tell you, though, with

certainty and pride: a family from out West has moved to and is starting a

business up in Crosby, the town where they're giving away the free land. What's

more, that family, the Oehlkes, didn't even take advantage of that offer. That,

they will tell you, is not why they came.

Shawn Oehlke is 44 and grew up outside Chicago; his wife, Esther, is 46 and

hails from Long Island. After a stint working for Boeing in Albuquerque, Shawn,

an Air Force veteran with a technical background, decided to strike out on his

own someplace where the costs of living and doing business would be much lower,

the lifestyle much less frenetic. Esther stumbled upon PrairieOpportunity.com,

and after a few phone calls, the Oehlkes decided to visit. They had planned to

look at four small towns; Crosby, with about 1,050 residents, was by far the

largest. They went there first and liked it so much they never bothered with the

other three.

The Oehlkes shared their plans with Olson and Divide County's Economic

Development Council: they were going to start a company, SEO Precision, that

would design and build electro-optic mechanisms, primarily for military

applications. The E.D.C. was thrilled, acquired a 16,000-square-foot building in

the middle of town an old J.C. Penney, built in 1917 so they could to lease

it to the Oehlkes and, as Esther recalls, said all the right things. "We were

told, point-blank, by one of the town leaders, 'We have three banks and all the

money you need."' They were, she says, "very persuasive."

And so in August 2004 the Oehlkes packed up and moved, with their two school-age

sons, from New Mexico to North Dakota. They turned the old department store's

massive basement into Shawn's lab and workshop and assumed management of the

rest of the building. The ground floor now has a community room with a

television, a kitchen and wi-fi, a tech center where locals can take computer

classes and commercial space that houses a clothing boutique, a tanning salon

and a coffee bar. The second floor has eight apartments, only two of which were

already rented out one of them by David Olson, who is 30 and a bachelor when

the Oehlkes arrived; they rented out the others within a month and lived in one

themselves until they bought a house on the edge of town. None of this may sound

particularly revolutionary, but the Oehlkes are pioneers no less than the old

homesteaders, and they know it. "What we're realizing," Esther says, "is we're

probably the only ones from out of state who've come here to try and prove the

experiment."

How that experiment is turning out is a matter of some dispute. Throughout

northwest North Dakota, folks with ties to the marketing alliance cite the

Oehlkes as a great success story, even though most have never met them. The

Oehlkes, however, have their doubts. Sometimes, in fact, they feel downright

frustrated. The banks, they say, have not come through with all the loans they

promised and are, the Oehlkes perceive, holding them to much more rigorous

standards than they apply to natives; town and county committees that were

supposed to approve tax credits and variances have dithered or, worse, failed to

meet at all. By last November, Esther was so discouraged that she wrote an open

letter to the town that was published in The Journal, Crosby's weekly newspaper.

"Is Crosby's existence important?" she asked. "Are you interested in seeing it

survive and grow? We heard that North Dakota wanted small businesses, and to

attract their young people back to the local towns.. . .So we believed you." She

lamented: "We're happy to be here, but some of you, even those of you in

decision-making positions that affect the future of the town, aren't happy we're

here.. . .Meetings put off, lack of vision in planning ahead, burdensome

regulations that are used arbitrarily, counting cost instead of counting value

these are why businesses and people leave this town."

Steve Andrist, the publisher of The Journal, finds himself caught in the middle

of the debate. "I'm acutely aware that there are people who are an impediment to

progress," he says. "I think they're in a minority. If I thought they were a

majority, I'd leave myself."

Andrist, who is the third generation of his family to run the paper his father

represents the area in the State Senate actually did leave Crosby for nearly

20 years. He graduated from Divide County High School in 1972, left for college,

then spent a decade and a half working as a reporter and editor outside the

state, mostly in Minnesota, which seems to draw a lot of people from North

Dakota. He returned in 1991 with a different perspective and a wife who grew up

elsewhere in the Midwest. This last fact is perhaps what enables him to

understand why so many non-Crosbyites see the place as isolated (it's 6 miles

from the Canadian border, 70 from the nearest American McDonald's or Wal-Mart,

120 from the nearest shopping mall), insular and clannish. Asked if his wife is

now regarded by natives as a Crosbyite, he replies, candidly: "I think she is to

the people who are important to her. And I think she'd have a hard time fitting

in with other people."

As for the Oehlkes, Esther says that the response to her open letter has been

mostly positive, although she also received critical letters that she

characterizes as "Survival, yes. Crosby wants survival. But no growth." Their

feelings for the town, however, are far from ambivalent. Asked if they'll stay,

both respond, without hesitation, "Oh, yes." Esther adds, "I'd do it again." She

and Shawn say again and again how much they love Crosby and its people. They

have found what they sought here: Small Town America.

And yet, in doing so, they have exposed the paradox at the heart of this

transaction. On the one hand, what towns like Crosby are actually selling

really, all they have to sell is atmosphere, an idyllic image of a place and a

way of life most Americans believe is already gone. On the other hand, if these

places are truly successful in attracting new people, that atmosphere will,

necessarily, change.

Despite the unease that paradox engenders here, Crosby's real choice is not

between growth or stasis; it is between growth or decline and, ultimately,

death. For his part, Loyd Olin says: "I think it'll get smaller. Of course, you

don't like to see it, but then what are you going to do?"

Those in Crosby who want a glimpse of what their future may hold should they

choose to do nothing need only drive 12 miles west on Highway 5 to the town of

Ambrose. Founded in 1906, Ambrose was the first county seat and once bore the

nickname the Queen City of Divide County. The "W.P.A. Guide to North Dakota,"

first published in 1938, recounts that Ambrose "in its early history was one of

the greatest primary grain markets in the Northwest. With 5 elevators, and many

hawkers buying on the track, as many as 300 grain wagons often crowded the

streets." In 1920, Ambrose's population was 389. As of 2004, it was 23.

Forty-two miles south and west of Ambrose, you'll find Hanks, N.D. Once upon a

time, according to the W.P.A. guide, as many as 30,000 cattle used to pass

through Hanks in a single season on their way to Chicago. Hanks was founded in

1916; in 1926, the town claimed a population of 300. And in 1991, that number

was down to 11, and Hanks voted itself out of existence.

To be more precise, the citizens of Hanks voted 7-2 to unincorporate (two

residents abstained). The vote, like many previous elections, was held in Lloyd

and Avis Kohlman's kitchen and merely confirmed what everyone in town had known

for years: Hanks was finished. It is a story that had been playing out quietly

for years in scores of towns across the state, but Hanks garnered a little bit

of attention by making it official. To the residents, it only made sense:

incorporated towns have certain obligations and responsibilities they need

mayors and city councilmen and city auditors and election judges and election

clerks that are difficult to fulfill when the whole town doesn't have a dozen

people in it. Still, the dissolution caught a lot of people by surprise. "North

Dakota made it very easy to incorporate a town, but very difficult to dissolve

one," explains Richard Stenberg, a history professor at Williston State College.

By 1991, Lloyd Kohlman had served on Hanks's town board for decades; Avis had

been city auditor since 1953. They raised two sons there, both of whom ended up

in Williston Roger as a pharmacist, Dennis as a high-school teacher. At a

certain point, Dennis says, all the young people left Hanks. "If you weren't

involved in farming, there was nothing else," he explains.

Dennis is 65 now. When he was a child, he recalls, Hanks still had about 150

people. "It's just been a gradual decline all along," he says. "Mostly, it's

just been that people have gotten old and passed away." That would include his

parents, who stayed on in Hanks until they died, two days apart, in June 2004.

Their deaths reduced the local population to 1.

Hanks sits on Highway 50 in northern Williams County. It is six miles west of

the community of Zahl, where the population, according to an informal census, is

8; back in the 1920's, 250 people lived there. Seven miles west of Hanks is the

town of Grenora its name is a contraction of Great Northern Railroad, a branch

line of which terminated there with a population of 195, down from a peak of

525. Grenora still has a functioning school and a few stores and shops and a

grocery and a cafe and a bar and even a credit union, but despite that, and the

fact that it's the biggest town for more than 40 miles, it just doesn't look

like the kind of place that will be around that much longer.

Hanks, on the other hand, doesn't really look like a ghost town, at least not

from a distance. Many of its houses appear well kept, as does its old school,

which now houses a museum, albeit one that's open only in the summer and then

only by appointment. "It'll be closed here not too long," Dennis Kohlman says,

"like everything else." It is painful to compare this Hanks with the town

Dennis's father first saw as a child. "When we came here in 1921," Lloyd Kohlman

told The Williston Daily Herald 70 years later, "there wasn't room for another

business on Main Street." Today, Main Street is overgrown; you wouldn't be able

to find it at all unless someone who knew showed you where it used to be. The

stores have all been torn down or carted off, used for storage or lumber. Only

the old State Bank of Hanks building, weather-beaten and crumbling, still stands

and next to it, an old red gasoline pump.

The only person left in Hanks is Debra Quarne. She lived there as a child, moved

to Montana when she was 10 and then returned in 1981 and moved into her

grandmother's old house; it was built in 1914 by a man named Alfred Karlson, who

dug out the basement by hand. There were no usable springs in Hanks the

groundwater was too high in salt and nitrates so people hauled in their water

from other towns and kept it in basement cisterns. "You can imagine what it was

like hauling that water when it was 18, 20 degrees below zero," Quarne says. In

1991, shortly before the town unincorporated, the other residents asked her if

she wanted to be mayor. She declined.

Still, she stayed after everyone else left or died. Asked what it's like to be

the only person left in Hanks, Quarne, who raises horses, says: "Quiet. You got

to stock up on groceries. You get snowed in, it could be four days before

someone gets you out." She says she likes the seclusion but admits: "It's sad.

It is, you know."

In 1991 Avis Kohlman told The Herald: "We don't have anything anymore. We don't

have a church. Everything is gone.. . .We aren't on the map because we don't

have a post office. So you kind of lose your identity." After she and Lloyd

died, her son sold their house. "I had a hard time with that," he confesses.

"But I didn't want it to end up like that place," he adds, gesturing at the old

bank. He is not sure what the buyer, a man in Williston, plans to do with it;

the house next door, once the home of a family named Rodvold, is now being used

by others from Williston as a hunting lodge.

The railroad branch line that gave birth to Hanks and Zahl and Grenora and

nearly a dozen other towns shut down in 1998; the company even pulled up its

tracks. Hanks, everyone agrees, will never come back. "It'll never be anything

more than it is now," Kohlman says.

"And the same thing'll happen to Grenora," Quarne adds.

"It'll just take a little longer," Kohlman concludes. And that, he says, is just

the surface view of things. "Our perception of what a small town is has

changed," he says. "Today, Williston is a small town. Just like our perception

of small farms has changed. It used to be one quarter. Today, 10 quarters is a

small farm."

Professor Stenberg agrees. And when it comes to predictions, he says the area

will either redefine itself and rebound or it will be "last one out, shut the

lights off." Like many other people in the area, he's doggedly optimistic. Or at

least he wants to be. But pressed to say what he thinks northwest North Dakota's

small towns are going to look like in 20 or 50 years, he sighs and answers: "I

don't think they're going to be there. There may be a historic marker there, but

that's it."

Tourism, which has been a savior of sorts for so much of rural America in

decline, has never been as big in North Dakota as it has been elsewhere; the

least-visited state in the nation, North Dakota's biggest draws are sites that

Lewis and Clark passed through 200 years ago. But folks who are nostalgic for

Small Town America might want to consider taking their next vacation in

northwest North Dakota, where, if they visit soon, they can see such places

before they disappear forever, where they can walk the streets and chat with the

few folks who remain and drop in on quaint little establishments like the

Centennial Bar in Grenora, where they happen to serve excellent hamburgers. Get

one while you still can.

Richard Rubin is the author of "Confederacy of Silence: A True Tale of the New

Old South." He last wrote for the magazine about the Emmett Till case.

Not

Far From Forsaken, NYT, 89.4.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/09/magazine/09dakota.html

NYT

April 2, 2006

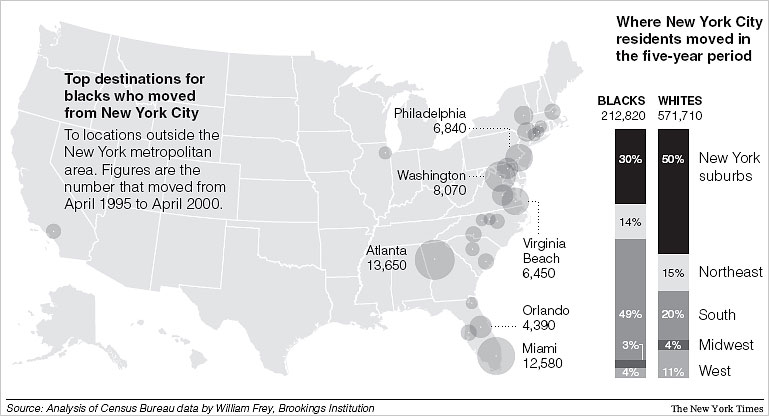

New York City Losing Blacks, Many to South

NYT 3.4.2006

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/03/nyregion/03blacks.html

New York City Losing Blacks,

Many to South

April 3, 2006

The New York Times

By SAM ROBERTS

An accelerating exodus of American-born blacks, coupled

with slight declines in birthrates and a slowing influx of Caribbean and African

immigrants, have produced a decline in New York City's black population for the

first time since the draft riots during the Civil War, according to preliminary

census estimates.

An analysis of the latest figures, which show the city with 30,000 fewer black

residents in 2004 than in 2000, also revealed stark contrasts in the migration

patterns of blacks and whites.

While white New Yorkers are still more likely than blacks to leave the city,

they are also more likely to relocate to the nearby suburbs (which is where half

the whites move) or elsewhere in the Northeast, or to scatter to other cities

and retirement communities across the country. Moreover, New York remains a

magnet for whites from most other states.

In contrast, 7 in 10 black people who are moving leave the region altogether.

And, unlike black migrants from Chicago, Philadelphia and Detroit, most of them

go to the South, especially to Florida, the Carolinas and Georgia. The rest move

to states like California, Ohio, Illinois and Michigan with large black

populations.

Also, New York has a net loss of blacks to all but five states, and those net

gains are minuscule.

"This suggests that the black movement out of New York City is much more of an

evacuation than the movement for whites," said William Frey, a demographer for

the Brookings Institution, who analyzed migration patterns for The New York

Times.

The implications for a city of 8.2 million people could be profound. If the

trend continues, not only will the black share of New York's population, which

dipped below 25 percent in 2000, continue to decline, particularly if the

overall population grows, but a higher proportion of black New Yorkers will be

foreign-born or the children of immigrants.

Many blacks are leaving for economic reasons. Jacqueline Dowdell moved to North

Carolina last year from Hamilton Heights in Upper Manhattan in search of a lower

cost of living. Once an editor at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black

Culture in Harlem, she now works as a communications coordinator for a health

care company in Chapel Hill.

"It was a difficult decision, but it was a financial decision," said Ms.

Dowdell, 39, adding that the move also gave her time to research her family's

roots in Virginia.

"I just continued to spend so much money trying to live without thinking about

the future," she said. "I was focused on surviving, and I wanted to make a

commitment to more quality of life."

The analysis of migration from 1995 to 2000 also suggests that many blacks,

already struggling with high housing costs in New York City, are being priced

out of nearby suburbs, too. Among black married couples with children, only

about one in three who left the city moved to nearby suburbs, compared with two

in three white married couples with children. More black married couples with

children moved to the South than to the suburbs. Over all, more black residents

who left New York City moved to Florida than to New Jersey.

But black residents who left the city were more likely to remain in the region

if they had higher incomes and were college educated. And while black migrants

to the South include some aspiring professionals, a larger share were lower

income, less educated and elderly.

"All this suggests that New York City out-migration of blacks is unique in its

scope net losses to most states and pattern especially destined to the

South," Dr. Frey said.

Reversing a tide from the South who altered the complexion of the city earlier

in the 20th century, the number of American-born blacks leaving the city has

exceeded the number arriving since at least the late 1970's.

"You have older people who leave the North just to go back to a place that is

kind of slower, or where they grew up or went on vacation when they were younger

and when you retire, your money doesn't go very far in New York," said

Sylviane A. Diouf, a historian and researcher at the Schomburg Center and

co-author of a study of black migration. "You also have young college-educated

people who find that the South has lots of economic potential and a lower cost

of living."

The slower pace appealed to Gladys Favours, who worked for a city councilwoman

from Brooklyn and moved from East New York seven years ago to a town of fewer

than 1,000 people near Charlotte, N.C, after she was unable to find another job.

"I lived in New York for almost 50 years and loved what it offered in schools,

entertainment and convenience, but I lost my job and finding one at my age would

pay half of what I was making," she said. "I was divorced and moved here with my

11-year-old I was afraid of the crime, and black boys don't fare too well in

New York."

Her son is now in college and she is working for the county emergency services

department.

"I'm 60 now," she said. "I think I was ready for the quietness."

While residential segregation persists, racial and ethnic minorities, including

immigrants, have become more mobile, with lower-skilled workers lured to growing

cities in the South and West for construction, retail and service jobs and

professionals applying for the same opportunities that had been previously open

mainly to whites.

"Some foreign-born blacks are moving out, too to the suburbs as well as to

other parts of the country, particularly South Florida," said Nancy Foner, a

distinguished professor of sociology at Hunter College.

Andrew Hacker, a political scientist at Queens College, cited other factors.

"After 15 or 20 years with, say the Postal Service or U.P.S., employees can put

in for transfers to other parts of the country," he said. "As a result, more

than a few middle-class black New Yorkers have been moving back to states like

North Carolina and Georgia, where they have family ties, living costs are lower,

neighborhoods are safer, schools are often better and life is less hectic."

In 1997, Christine Wiggins retired as an assistant bank manager after 25 years.

She left Queens Village and followed her brother, who worked for the New York

City Transit, to the Poconos in Pennsylvania.

"It was hard for him, he had to commute," she said. "But we wanted to get away

from the city."

The East Stroudsburg, Pa., area, where radio advertisements lured first-time

homebuyers, was among the 15 top destinations for black residents leaving New

York City. More black New Yorkers moved to Monroe County in the Poconos than to

either the Rockland or Orange County suburbs of New York.

Over all, the city's black population grew by 115,000 in the 1990's, a 6.2

percent increase. (New Yorkers in the armed forces or who are institutionalized

are not counted as residents.) Those early estimates of the 30,000 drop in black

population since 2000, a 1.5 percent decline, suggest that among blacks, the

arrival of newcomers from abroad and higher birthrates among immigrants were not

keeping pace with the outflow.

Last year, a study by the Pew Hispanic Center, a nonpartisan research group,

found that while the gush of immigrants continued into the 21st century, it

appeared to have slowed somewhat.

A net loss of black residents, even between censuses, would apparently be the

first since the Civil War. In 1863, after mobs attacked blacks during the draft

riots, many fled New York City. "By 1865," Leslie M. Harris wrote in "In the

Shadow of Slavery," the city's "black population had plummeted to just under

10,000, its lowest since 1820."

New York City

Losing Blacks, Many to South, NYT, 3.4.2006

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/03/nyregion/03blacks.html

Adopted in China,

Seeking Identity in America

March 23, 2006

The New York Times

By LYNETTE CLEMETSON

Molly Feazel desperately wants to quit the Chinese dance

group that her mother enrolled her in at age 5, because it sets her apart from

friends in her Virginia suburb. Her mother, though, insists that Molly, now 15,

will one day appreciate the connection to her culture.

Qiu Meng Fogarty, 13, prefers her Chinese name (pronounced cho mung) to Cecilia,

her English name. She volunteers in workshops for children in New York adopted

from China "so that they know it can all work out fine," she said.

Since 1991, when China loosened its adoption laws to address a growing number of

children abandoned because of a national one-child policy, American families

have adopted more than 55,000 Chinese children, almost all girls. Most of the

children are younger than 10, and an organized subculture has developed around

them, complete with play groups, tours of China and online support groups.

Molly and Qiu Meng represent the leading edge of this coming-of-age population,

adopted just after the laws changed and long before such placements became

popular, even fashionable.

Molly was among 61 Chinese children adopted by Americans in 1991, and Qiu Meng

was one of 206 adopted the next year, when the law was fully put into effect.

Last year, more than 7,900 children were adopted from China.

As the oldest of the adopted children move through their teenage years, they are

beginning independently and with a mix of enthusiasm and trepidation to

explore their identities. Their experiences offer hints at journeys yet to come

for thousands of Chinese children who are now becoming part of American families

each year.

Those experiences are influenced by factors like the level of diversity in their

neighborhoods and schools, and how their parents expose them to their heritage.

"We're unique," Qiu Meng said.

A view that Molly does not share. "I don't see myself as different at all," said

Molly, whose friends, her mother said, all seem to be "tall, thin and blond."

The different outlooks are normal say experts on transracial adoption.

Most Americans who bring Chinese children to the United States are white and in

the upper middle class.

Jane Brown, a social worker and adoptive parent who conducts workshops for

adopted children and their families, says the families should directly confront

issues of loss and rejection, which the children often face when they begin to

understand the social and gender politics that caused their families in China to

abandon them.

Ms. Brown also recommends that transracial adoptive families address American

attitudes on race early, consistently and head on.

"Sometimes parents want to celebrate, even exoticize, their child's culture,

without really dealing with race," said Ms. Brown, 52, who is white and who has

adopted children from Korea and China.

"It is one thing to dress children up in cute Chinese dresses, but the children

need real contact with Asian-Americans, not just waiters in restaurants on

Chinese New Year. And they need real validation about the racial issues they

experience."

The growing population is drawing the attention of researchers. The Evan B.

Donaldson Adoption Institute, a research group based in New York, is surveying

adopted children from Asia who are now adults to try to find ways to help the

younger children form healthy identities.

Nancy Kim Parsons, a filmmaker who was adopted from Korea, is making a

documentary comparing the experiences of adults who had been adopted a

generation ago from Korea with the young children adopted from China.

South Korea was the first country from which Americans adopted in significant

numbers, and it is still among the leaders in international adoptions, along

with Russia, Guatemala, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, India and Ethiopia. The experiences

of those adopted from Korea have provided useful lessons for families adopting

from China.

Hollee McGinnis, 34, the policy director at the Donaldson institute, was adopted

from South Korea by white parents and was raised in Westchester County. Ten

years ago, she started an adult support group, called Also Known As, which now

also mentors children adopted from China.

"College was when I really began trying to understand what other people saw in

my face," she said. "Before then I didn't really understand what it meant to be

Asian."

It is a process McKenzie Forbes, 17, who was adopted from China and raised in

towns in Virginia and West Virginia where there are few other Asians, is just

starting to absorb. For her, college holds the promise of something new.

"I am feeling ready to break out a little bit," McKenzie said. "When I am around

other Asians, I feel a connection that I don't feel around other people. I can't

explain it exactly. But I think it will be fun to meet other people and hear

their stories."

McKenzie, who was accepted by Dickinson College in Pennsylvania, applied only to

universities with Asian student groups. Confident and pensive, she likes

classical music and punk rock. She is wild about Japanese anime, a hobby she

hopes to turn into a career, and to travel to Japan. Exploring China, she said,

"is what everyone would expect."

Adopted at 2, McKenzie is among the oldest of the current wave of children

adopted from China. Like many Americans adopting from overseas at the time,

McKenzie's family turned to China because of a movement started in 1972 by the

National Association of Black Social Workers discouraging the placement of

African-American children with white adoptive families.

"With an African-American child we had no guarantee that the mother or a social

worker wouldn't come and take the child away," McKenzie's mother, Maree Forbes,

said. "With the children from China, we felt safe that there wouldn't be anyone

to come back to get them."

McKenzie has a younger sister, Meredyth, 15, also adopted from China, and

brothers Robert and John, 11-year-old twins, adopted from Vietnam. The family

left Culpepper, Va., when McKenzie was 5, after children at school ostracized

her because she is Chinese.

More frequent than outright racism though, McKenzie and Meredyth said, are

offenses of ignorance. They were called out of class at their current school,

for example, because a counselor wanted them to take an English language test

for immigrant students. "We probably spoke better English than the instructor,"

Meredyth said.

The experience has been different for Qiu Meng Fogarty. As she recovered from a

fit of giggles about something having to do with a boy, Qiu Meng looked at her

friends Celena Kopinski and Hope Goodrich, who were also adopted from China, and

breathed a cheery sigh.

"It's like we're related," she said, sitting on her bed in her home on

Manhattan's Upper West side. "It's nice because we're all on the same page. We

don't have to be like, 'Oh, you're adopted?' or 'Oh, yeah, I'm Chinese,' It's

just easy."

The three girls have been friends for as long as they can remember. Their

parents helped form Families With Children From China, a support group started

in 1993 that now has chapters worldwide.

Some teenagers lose interest in the group because many of its activities focus

on younger children. But Qiu Meng, a perky wisp of a girl with an infectious

laugh, is still enthusiastically involved. She sold "Year of the Dog" T-shirts

at a Chinese New Year event in January, and is a mentor at group workshops.

She said she remembers how hard it was to talk about painful things when she was

younger and children at school would stretch their eyes upward and tease her.

"There aren't a lot of children who can talk openly and easily about things like

that," she said. "So it feels good to be able to help them."

Last summer, Qiu Meng, Celena and Hope attended a camp for children adopted from

around the world. When it ended, counselors gathered the campers in a circle and

connected them with a string. The campers all went home with a section of the

string tied to their wrists, as a reminder their shared experience.

When a volleyball coach later told Qiu Meng to cut off the string for a game,

she carefully tucked it away, took it home and hung it on her bedroom wall among

numerous Chinese prints and paintings.

The teenagers all acknowledge that they are just beginning a long process of

self-definition, and even though Molly is still trying to persuade her parents

to allow her to quit the Chinese dance class, she admits privately that she

benefits from the struggle.

"If my parents didn't push, I know I would just drop it all completely," she

said. "And then I wouldn't have anything to fall back on later."

Molly, Qiu Meng and McKenzie said they would not have wanted to grow up any

other way, and they all said they would one day like to adopt from China. "It's

a good thing to do," Qiu Meng said. "And since I'm Asian, they wouldn't look

different."

Adopted in China,

Seeking Identity in America, NYT, 23.3.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/23/national/23adopt.html

Metro area 'fringes' are booming

Updated 3/15/2006 11:37 PM

USA TODAY

By Haya El Nasser and Paul Overberg

Americans continue their march away from congested and

costly areas halfway through the decade, settling in more remote counties even

if it means longer commutes, according to Census population estimates released

Thursday.

Some of the fastest-growing counties in 2005 lie on the

farthest edges of large metropolitan areas, stretching the definition of

"exurbs" to the limit.

"It's not just the decade of the exurbs but the decade of the exurbs of the

exurbs," says William Frey, demographer at the Brookings Institution. "People

are leaving expensive cores and going as far out as they can to get a big house

and a big yard. Suburbia is moving much further out."

Some of the fastest-growing counties from July 1, 2004, to July 1, 2005, include

Caroline and King George counties in Virginia, north of Richmond and south of

Washington, and Grundy County, Ill., about 60 miles southwest of the Chicago

Loop.

Cook County, which includes Chicago and older suburbs such as Schaumburg and

Arlington Heights, lost more people since 2000 than any other county: 73,000 to

5.3 million. "They're flowing out of Cook into the fringes," says Kenneth

Johnson, a demographer at Loyola University in Chicago. "People move out of

Chicago and into suburban Cook County and now they're losing to the outer

suburbs."

Rising gas prices do not seem to have steered Americans away from this outward

push. Skyrocketing housing prices in major markets are a major contributor to

growth in far-flung areas, Frey says.

95 south of the capital and then moved east toward King

George. The county grew 6.7% to 20,637 from 2004 to 2005.

"It's trickling down our way," says Jack Green, community development director

for King George County, a rural county until this decade. About 500 permits were

issued last year for single-family homes, up from 125 in 2000, he says.

Immigration, which has reshaped many parts of the nation, contributed little to

the boom in many remote counties. Much of the growth came from births and people

moving from elsewhere in the USA.

Immigrants, as they were for much of the 1990s, are the main reason many urban

counties and older suburbs are gaining population. More than 180,000 immigrants

settled in Harris County, Texas, home of Houston, from 2000 to 2005, offsetting

the net loss of almost 123,000 people to other counties.

The Census estimates also show that:

Florida has 15 of the fastest-growing counties, including the top grower for

the second year in a row, Flagler County. Located between Daytona Beach and

Jacksonville, Flagler grew 53% since 2000, to 76,410. The growth continued even

after four hurricanes struck the state in 2004, raising fears that more storms

would slow Florida's growth.

New Orleans was losing population even before Hurricane Katrina flooded the

city. Population dropped 6% since 2000, to 455,000. Its post-storm population is

estimated at less than 200,000.

Four counties have topped 1 million since 2000: Contra Costa, Calif., Fairfax,

Va.; Hillsborough and Orange counties, Fla.

Nineteen counties gained more than 100,000 people and grew by more than 10%

since 2000, Frey says. Maricopa County, Ariz., which includes Phoenix, gained

563,000 from 2000 to 2005 more than any other county.

California's expensive coastal regions lost to inland counties such as

Riverside and San Bernardino.

"Suburbs are getting suburbs at this point," Frey says.

Where the growth is

The USA's fastest-growing counties with populations greater

than 10,000 in 2004-05, with their percentage of growth and the driving distance

from the county seat to the nearest major city:

Rank/county Growth Distance

1. Flagler, Fla. 10.7% 25 miles to Daytona Beach

2. Lyon, Nev. 9.6% 80 miles to Reno

3. Kendall, Ill. 9.4% 50 miles to Chicago

4. Rockwall, Texas 7.7% 20 miles to Dallas

5. Washington, Utah 7.7% 120 miles to Las Vegas

6. Nye, Nev. 7.4% 210 miles to Las Vegas

7. Pinal, Ariz. 6.9% 60 miles to Phoenix

8. Loudoun, Va. 6.8% 35 miles to Washington

9. King George, Va. 6.7% 60 miles to Richmond

10. Caroline, Va. 6.5% 40 miles to Richmond

Sources: Census Bureau, USA TODAY research

Metro area

'fringes' are booming, UT, 15.3.2006,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/census/2006-03-15-census-growth_x.htm

Gentrification

Changing Face of New Atlanta

March 11, 2006

The New York Times

By SHAILA DEWAN

ATLANTA, March 8 In-town living. Live-work-play. Mixed

income. The buzzwords of soft-core urbanism are everywhere these days in this

eternally optimistic city, used in real estate advertisements and mayoral boasts

to lure money from the suburbs and to keep young people from leaving.

Loft apartments roll onto the market every week, the public housing authority is

a nationally recognized pioneer in redevelopment and the newest shopping plaza

has one Target and three Starbucks outlets.

But although gentrification has expanded the city's tax base and weeded out

blight, it has had an unintended effect on Atlanta, long a lure to

African-Americans and a symbol of black success. For the first time since the

1920's, the black share of the city's population is declining and the white

percentage is on the rise.

The change has introduced an element of uncertainty into local politics, which

has been dominated by blacks since 1973, when Atlanta became the first major

Southern city to elect a black mayor.

Some, like Mayor Shirley Franklin, who is serving her second and final term,

play down the significance of the change, saying that the city now 54 percent

black will remain progressive and that voters here do not strictly adhere to

racial lines. Others warn of the dilution, if not the demise, of black power.

"It's certainly affecting local politics," said Billy Linville, a political

consultant who has worked for Ms. Franklin. "More white politicians are focusing

on possibly becoming mayor and positioning themselves accordingly, whereas in

the past they would not have. The next mayor of Atlanta, I believe, will be

African-American, but after that it may get very interesting."

The changes do not mean that Atlanta has lost its magnetism for blacks.

Twenty-year projections show the percentage of African-Americans continuing to

inch upward in the 10-county metropolitan area. Blacks already hold the majority

on the Clayton County commission, and they are gaining footholds in counties

like Cobb and Gwinnett.

But the city itself, a small splotch of fewer than half a million residents in a

galaxy of sprawl, is now attracting the affluent, who are mostly white, in part

because they want to avoid gear-grinding commutes that are among the nation's

longest.

In that sense, demographers say, the shift is driven by class rather than race.

In 1990, the per capita income in the city of Atlanta was below that of the

metropolitan area as a whole, but in 2004 it was 28 percent higher, the largest

such shift in the country, according to a University of Virginia urban planning

study.

So rapid is the explosion of wealth that Ms. Franklin recently tried to impose a

moratorium on McMansions, new houses bloated far beyond the size of their older

neighbors.

According to census figures, non-Hispanic blacks went from a high of 66.8

percent of Atlanta's population in 1990 to 61 percent in 2000 and to 54 percent

in 2004. In the same time period, non-Hispanic whites went from 30.3 percent to

35 percent. The 2004 figures are estimates.

Even the Old Fourth Ward, the once elegant black neighborhood where Martin

Luther King Jr. was born, is now less than 75 percent black, down from 94

percent in 1990, as houses have skyrocketed in value and low-rent apartments

have been replaced by new developments.

"There could be a time in the not-too-distant future when the black population

is below half of the city population, if this trend continues," said William

Frey, a demographer at the Brookings Institution, a Washington research group.

Atlanta's upward shift in its white population is atypical, Mr. Frey said.

Although many other cities have embarked on revitalization programs, only

Washington is seeing a similar, if less stark, racial trend as Atlanta. More

often, blacks and whites both are losing ground to a surging Latino population.

Even in Atlanta, the Latino population rose to 26,100 in 2004 from 18,700 in

2000.

Most mayors would see a physical revitalization like Atlanta's as an

accomplishment. The city has led the country, rivaled only by Chicago, in the

race to replace public housing projects with mixed-income developments.

Housing has also mushroomed in places where it had not previously existed. The

most ambitious project, Atlantic Station, a shopping and residential district on

the site of a former steel mill near downtown, will have more than 2,000 units.

Loft prices start at $160,000.

But critics say Mayor Franklin and her predecessor, Bill Campbell, betrayed

their voter base by not doing enough to keep Atlanta affordable for poor blacks

as property taxes increase and landlords sell out to developers.

"It's clear as the nose on your face who it's going to impact the most," said

Joe Beasley, the human resources director at an Atlanta church and a member of

the city's Gentrification Task Force, now defunct, which studied ways to ease

the effects of rising property taxes and housing prices. "Bill Campbell was

cutting his own throat, and Shirley Franklin is continuing to cut her own

throat."

Ms. Franklin counters that many new developments, including Atlantic Station,

have set aside areas for low-income or affordable housing. She says one of her

major accomplishments, financing a badly needed overhaul of the sewage and water

system without a large increase in rates, has kept city living affordable. But

the bottom line, in the mayor's view, is that the city must try to mold

development where it can.

"We're constantly seeking a balance in what we support," Ms. Franklin said last

week in a telephone interview.

David Bositis, a senior political analyst at the Joint Center for Political and

Economic Studies, a Washington group that studies black issues, said he viewed

the change as largely positive. "I don't know that it ever was a good thing when

you had cities that were becoming viewed as black cities," Mr. Bositis said.

He added, "People said, 'This is our city now,' but half the time you looked at

what was there and you said, 'Who cares?' "

Race is not the only factor in the political equation.

"We're talking about an era in which you see a conservative trend among certain

sectors of the black community," said William Boone, a political science

professor at Clark Atlanta University, a predominantly African-American

institution. "That's going to have some impact on who's offered for mayor."

Power in Atlanta has always involved coalitions of blacks and other groups, said

Ms. Franklin, who has received high marks for restoring credibility to city

government and who was re-elected in 2005 with 91 percent of the vote.

"This whole notion that the sky is falling, I don't see it," Ms. Franklin said.

"To me the question is, Will Atlanta be a progressive city, given that it's the

home of the civil rights movement, the home of the historically black colleges?

Will that continue with the demographic shifts? And my answer is yes."

Already, the change has had unpredictable effects. Kwanza Hall is a young black

politician from the rapidly gentrifying Old Fourth Ward, a neighborhood that is

part of a mostly white City Council district that includes affluent areas like

Inman Park. But in the last election, Mr. Hall, who ran his campaign from a

year-old coffee shop next to a soon-to-open men's spa, defeated two whites for

an open seat.

To Joe Stewardson, who owns the coffee shop building and was the first white

president of the ward's community development corporation, the question was not

Mr. Hall's race but his ability to forge relationships outside a neighborhood

whose boundary was, not too long ago, what Mr. Stewardson called "an iron

curtain."

"You would not have seen that," Mr. Stewardson said, "if this neighborhood had

not changed so much."

Brenda Goodman contributed reporting for this article.

Gentrification

Changing Face of New Atlanta, NYT, 11.3.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/11/national/11atlanta.html

Changing U.S. Audience

Poses Test for a Giant of Spanish

TV

March 10, 2006

The New York Times

By MIREYA NAVARRO

LOS ANGELES, March 9 Rosa Guevara, a Mexican-American

dental hygienist, grew up with the Univision network's Spanish-language soap

operas, which she still watches. But Mrs. Guevara, 59, now watches alone.

On any given night, her husband is glued to a western on cable while her

25-year-old daughter who used to watch the soaps with her, may tune in to

"George Lopez" on ABC or syndicated reruns of "Friends."

"She doesn't like telenovelas anymore," said Mrs. Guevara, who lives in Pico

Rivera, an overwhelmingly Latino city in Los Angeles County.

Households like the Guevaras' reflect an evolution in what was once the

unquestioned loyalty of the vast Latino audience in the United States, where

Univision is the giant of Spanish-language television.

Catering to the country's growing Latino population 40 million and counting

Univision now challenges ABC, CBS, NBC and Fox, especially in big coastal cities

like New York, Los Angeles and Miami, occasionally beating them in the ratings

with its sexy, soapy prime-time shows.

But as would-be buyers prepare bids for Univision Communications, a consortium

including Grupo Televisa of Mexico, which supplies many of the network's shows,

emerged Thursday as a potential bidder. [Page C1.]

Any new owner would have to wrestle with the shifting dynamics of the company's

audience. More Latinos are American-born and English-speaking, and their tastes

in television are changing more quickly than Univision's shows.

That poses challenges not only for Univision but for other Spanish- and

English-language networks. For the first time, networks on each side of the

language divide could significantly expand their audiences by pursuing the same

demographic group: second- and third-generation Latinos who are bilingual or

speak mostly English and are as likely to watch "Fear Factor" on NBC as "El

Gordo y la Flaca" ("The Scoop and the Skinny") on Univision, and who are largely

underserved in either language.

"This audience wants to be validated," said Jeff Valdez, founder of SiTV, a

two-year-old English-language cable network that caters to young Latinos and

multicultural urban youth. "They want to see themselves on screen. They want to

hear their stories."

The guidebook on how to appeal to this acculturated yet ethnically proud

audience is still a work in progress.

SiTV strives for hipness with programs like "Urban Jungle," a reality show in

which 12 young suburbanites move to South Central Los Angeles, and "The Rub," a

talk show about sex and relationships. MegaTV, a new Spanish-language television

station that was started in Miami this month by the Spanish Broadcasting System

radio chain, is offering such fare as an interactive debate show and the

television version of a prank-filled morning radio show.

Telemundo, the perennial No. 2 Spanish-language network to Univision that is

owned by NBC Universal, is, meanwhile, getting significant bumps in prime-time

ratings from new telenovelas and other one-hour dramas with contemporary themes,

sometimes set in the United States.

So far, Univision, whose officials declined to be interviewed, has captured

Latino audiences of all ages both by keeping English out of its programs and

commercials and by sticking to a prime-time lineup anchored in telenovelas from

Mexico. There has been little reason to change of the 100 most-watched