|

History > 2006 > USA > Weather >

Hurricane Katrina

Evacuees

(I)

Lawsuit Is Filed to Force FEMA

to Continue

Housing Vouchers

May 20, 2006

The New York Times

By SHAILA DEWAN

Lawyers for New Orleans evacuees filed suit in

Houston yesterday, asking a federal court to stop the Federal Emergency

Management Agency from ending housing benefits for tens of thousands of people

who fled the flooding of Hurricane Katrina. The evacuees had been issued

12-month housing vouchers by local governments but are now being told by FEMA

that they must pay rent or leave.

The class-action suit, filed in United States District Court for the Southern

District of Texas, says the agency has made "arbitrary, inconsistent and

inequitable housing decisions without using any ascertainable standards" and

describes the situation of several plaintiffs who, it contends, received vague

or contradictory letters from FEMA or were denied further housing assistance for

false reasons.

The suit was filed by Caddell & Chapman, a Houston firm, joined by a consortium

of public interest legal groups.

The vouchers provided, in most cases, one year of housing and utilities to about

55,000 families, and were issued by Houston and other cities with the

understanding that FEMA would reimburse them. Last month, agency officials said

that nearly a third of the families some 8,000 in Houston alone were

ineligible for such assistance.

But the mayor of Houston, Bill White, said many of the ineligibility rulings

from FEMA were wrong. Some evacuees were told that their homes in New Orleans

had not been damaged badly enough to qualify for assistance: that someone else

in their household had already qualified for assistance elsewhere; that they

failed to appear in person for an inspection of their home; or that their

housing assistance had been withdrawn because a signature was missing from their

paperwork.

Some were even told that they were not eligible for housing assistance because

they had received a voucher, though the vouchers were being discontinued.

A FEMA official declined to discuss the lawsuit. "We're aware of the situation,"

said the official, Aaron Walker, a spokesman for the agency in Washington.

"According to FEMA policy, we cannot comment on any pending litigation."

Agency officials have defended the decision to end the program, saying the

vouchers were issued under the emergency housing program, which is available to

virtually anyone from a disaster area but is not intended to be used for

extended periods. That program ended in March. Hurricane Katrina families are

being converted to the agency's long-term individual assistance program, which

has stricter eligibility requirements.

FEMA officials have also said that the voucher program was unfair because not

all evacuees received them some entered the individual assistance program

right away and received money to pay their own rent, which counts against the

agency's per-family limit of $26,200.

The lawsuit says that in at least one previous disaster the agency has provided

emergency housing for longer than a year. Federal law does not specify a time

limit for emergency housing.

The lawsuit also addresses what it says are onerous requirements even for the

eligible, who must now sign a new lease with their landlords, pay for their own

utilities and requalify every three months. FEMA has failed to adjust its

estimation of fair-market rents or provide clear criteria for requalification,

the suit says.

Lawsuit Is Filed to Force FEMA to Continue Housing Vouchers, NYT, 20.5.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/05/20/us/20vouchers.html

Frustration high ahead of New Orleans poll

Fri May 12, 2006 8:51 PM ET

Reuters

By Jeffrey Jones

NEW ORLEANS (Reuters) - Kemberly Samuels is

frustrated, and not just because she is still unable to return to her home in

New Orleans.

One of thousands exiled in Houston after Hurricane Katrina, Samuels said the two

candidates for New Orleans mayor have appeared to lose interest in reaching out

to displaced voters for the May 20 runoff election between the two Democrats.

The 53-year-old teacher helped marshal about 50 fellow evacuees from the Texas

city this week for a five-hour bus trip home to attend a debate between Mayor

Ray Nagin and his challenger, Louisiana Lt. Gov. Mitch Landrieu.

"It was a slap in our face, because we feel they need our votes," said Samuels,

whose efforts were led by activist group Association of Community Organizations

for Reform Now. "To have us have to come out here instead of them coming to us

kind of downplayed us as not being important at all."

Campaign workers deny candidates are avoiding evacuees, but admit to far less

out-of-town travel than before the April primary. The candidates haven't gone to

Houston to campaign or debate for the runoff, although they have made a few

trips to see displaced voters within Louisiana.

But Samuels expressed some of the growing frustrations among voters here and

scattered across the country as the long race to lead the massive recovery heads

into its final week with no clear front-runner emerging.

Nagin and Landrieu face the tough task of distinguishing themselves while

touting similar policies.

AHEAD OF STORM SEASON

Nagin said he is the man of experience dealing with state and federal

authorities and the business community, and warns against a change just before

the storm season starts June 1.

Landrieu, brother of Democratic U.S. Sen. Mary Landrieu and son of the city's

last white mayor, stresses his talent lies in building coalitions, a skill he

said Nagin lacks and one required to speed up the plodding recovery process.

The agenda is all but set for the struggling city, where more than half the

pre-Katrina population has yet to return, said Brian Brox, a political scientist

at Tulane University.

Voters want confidence the economy will pick up, ravaged neighborhoods will

rejuvenate, evacuees can return and the levees will hold when the next storm

hits, he said.

"As candidates, they have slight differences in their plans, but right now

they're trying to differentiate themselves on their ability to enact them and

enact them quickly," Brox said. "It's connections, it's leadership, it's who is

going to be the more vigorous advocate for New Orleans."

The list of problems is long. Large parts of the city, such as New Orleans East

and the Lower Ninth Ward, appear stuck in suspended animation. Streets are lined

with debris and empty houses, the only visible change over eight months being

the recent growth of weeds in yards. Crime is making a comeback.

Fears also abound that New Orleans faces bankruptcy, although Nagin said the

city has enough money to last through the summer and he is working to finalize a

$150 million line of credit with a consortium of 20 banks.

Many pundits had written Nagin off after he was criticized for a shaky initial

response to the disaster and some racially charged remarks. But the former cable

executive vaulted to the lead in the April primary with 38 percent of the vote,

gaining large support from the black community.

After that campaign, analysts again said the mayor was in trouble, pointing out

that 21 of his rivals took a combined 62 percent of the vote. That may have also

been premature.

Landrieu won 29 percent in April, but had the more even split between black and

white voters, according to state figures.

"I haven't done a poll, but personally I think the election's very close," said

Ed Renwick, a Loyola University political science professor. He says he now

believes many of the white voters are still undecided.

Frustration high ahead of New Orleans poll, R, 1222.5.006,

http://today.reuters.com/news/newsArticle.aspx?type=politicsNews&storyID=2006-05-13T005127Z_01_N124935_RTRUKOC_0_US-HURRICANES-ELECTION.xml

Evacuees Find Housing Grants Will End Soon

April 27, 2006

The New York Times

By SHAILA DEWAN

HOUSTON, April 21 Thousands of hurricane

evacuees who counted on a year of free housing and utilities are being told by

the Federal Emergency Management Agency that they are no longer eligible for

such help and must either pay the rent themselves or leave.

Of about 55,000 families who were given long-term housing vouchers, nearly a

third are receiving notices that they no longer qualify, FEMA officials said.

For the rest, benefits are also being cut: they will have to sign new leases,

pay their own gas and electric bills and requalify for rental assistance every

three months.

The process has been marked by sharp disagreements between the agency and local

officials, and conflicting information given to evacuees about their futures.

Although agency officials say they never promised a full year of free housing,

many local officials around the country say yearlong vouchers were exactly what

FEMA agreed to provide.

[The agency was sharply criticized in draft bipartisan recommendations to be

released Thursday by a Senate committee, which said the agency functioned so

poorly during Hurricane Katrina that Congress should abolish it and rebuild a

more powerful agency.]

In the desperate weeks after Hurricane Katrina, the vouchers helped stabilize

the lives of evacuees who had bounced from place to place while trying to find

missing family members and deal with mysterious skin rashes, shellshocked

children and reams of red tape. At least, the vouchers promised, they would not

have to worry about shelter.

Now, eight months later, the notices have panicked evacuees and raised the ire

of local officials and landlords, who say FEMA is reneging on a promise and

dismantling a program that is helping more people and is far less expensive than

other housing solutions like trailers.

To make matters worse, advocates and local officials say, many evacuees either

do not know why they have been found ineligible or have been given spurious

reasons. Many notices do not even give a deadline, saying only, "You will not be

asked to leave before April 30."

"We believe that many of the people who received notice that they're ineligible

are eligible," said Mayor Bill White of Houston, where more than 9,000 of the

35,000 families on vouchers have been determined to be unqualified, raising

fears of mass homelessness.

In an effort to persuade FEMA to reconsider, Mr. White has gone so far as to

send teams of building inspectors to New Orleans to photograph evacuees'

destroyed homes.

David Garrett, FEMA's acting director of recovery, said the agency had promised

only to reimburse for "up to" 12 months of housing. But the cities that actually

issued the vouchers, including Houston, Memphis and Little Rock, Ark., said the

agency had agreed in negotiations to pay for the full term.

Although the paperwork accompanying the vouchers in Houston did say they were

good for "up to" 12 months, local officials in all three cities said evacuees

had been told, without contradiction from FEMA, that they would last a year.

"They knew exactly what we were doing," said Buddy Grantham, the chief operating

officer of the Joint Hurricane Housing Task Force for Houston, which issued the

12-month vouchers in anticipation of being reimbursed by FEMA. "We were totally

transparent."

Agency officials say fairness and the law prevent them from leaving the voucher

system in place. The programs were hurriedly set up by state and local

governments under FEMA guidelines for emergency housing, which is available to

virtually anyone from a disaster-stricken area but is not intended to be used

for extended periods.

Now, the agency is converting the families to its more traditional, and

stricter, long-term housing program, the individual assistance program. Many

people who qualified for emergency housing do not meet the requirements for

long-term assistance, and the agency says it cannot ask taxpayers to continue to

bankroll those families, although an agency spokesman, Aaron Walker, was unable

to provide an estimate of how much money would be saved.

Mr. Garrett said the program was not fair to families who did not get vouchers,

but instead went directly from shelters or hotels into the stricter program,

under which they receive rent money every three months. The payments count

against the total each family can legally receive from FEMA, $26,200, while rent

and utilities under the voucher program do not. (FEMA trailers do not count

either, agency officials said, because they are not as comfortable as

apartments.)

The emergency housing program covers utilities, but the individual assistance

program will not, unless Congress approves a request from President Bush to

change the regulations.

The movement away from long-term vouchers has created widespread confusion among

evacuees. A disabled evacuee in Little Rock said that when she called FEMA to

ask why her rent was no longer being paid she was informed, erroneously, that

she had never had a voucher. In Memphis, where there are 1,500 families on

vouchers, FEMA initially asked those running the program to reclaim the

furniture and basic kitchen items issued to evacuees, backing down after

strenuous objections, said Susan Adams, the executive director of the Memphis

and Shelby County Community Services Agency.

"It feels like a total lack of compassion," Ms. Adams said. "A total lack of

humanity."

FEMA has no record of the furniture request, a spokesman for the agency said.

In interviews with more a dozen evacuees, some said they had been told they were

ineligible because their home in New Orleans had not suffered enough damage, or

they had insurance covering living expenses, or their paperwork lacked a

signature, or they had not appeared in person for an inspection of their damaged

home. FEMA recently agreed to review its findings for mistakes.

Mr. Garrett emphasized that evacuees could appeal any decision. But according to

written guidelines, the agency will not continue to pay rent while a case is on

appeal.

FEMA itself has difficulty explaining the ineligibility findings. The agency

told Houston officials that about 1,200 of 8,500 families had insufficient

damage to their homes and that 1,600 were in a category called "ineligible

other." Some 1,050 were denied on appeal, but the original reason for the denial

was not given. More than 2,300 were described as being eligible only for an

initial $2,000, with no further explanation.

Some evacuees said they had planned their lives around the security of the

12-month voucher. Erica Stevens, 26, said the promise of housing had drawn her

and her three children to Houston after Hurricane Rita destroyed her home in

Beaumont, Tex. She did not receive much other assistance, she said, because her

landlord filed a FEMA claim on the house before she did, making her ineligible.

Karen Douglas, an evacuee living with two sons in a pleasant house in a Houston

suburb, said that amid enrolling the elder son in school, battling insurance

adjusters and looking for a job, she had managed to put the insurance proceeds

from her destroyed house into investments that would mature in November, when

her voucher was to expire. "It's stressful, but I thought I had it together,"

she said.

Then, on April 15, Ms. Douglas too got a letter. She would like to appeal but

does not know why she was found ineligible. The letter says only that she had

been previously notified of the reason. "I was expecting FEMA to honor the

agreement," she said. "I wasn't expecting them to go midstream and pull the rug

out from underneath us."

Trailer Plan Is Revived

NEW ORLEANS, April 26 (AP) Mayor C. Ray Nagin and federal officials on

Wednesday revived the effort to place thousands of trailers throughout the city

as stopgap housing for people who lost their homes .

Three weeks ago Mr. Nagin halted work on new trailer sites, saying FEMA had used

"bullying" tactics and built a site outside a gated community without the proper

permits. But Mr. Nagin and FEMA officials now say they have bridged their

differences. Officials hope to install about 8,000 trailers by the end of June.

Before the impasse, FEMA had placed about 1,500 travel trailers at enclosed

sites around the city.

Evacuees Find Housing

Grants Will End Soon, NYT, 27.4.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/27/us/27vouchers.html

Katrina's Tide Carries Many to Hopeful

Shores NYT

23.4.2006

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/23/us/23diaspora.html

Jeralyn and Whitney Marcell, with Rashad,

10,

in their hurricane-ravaged home in the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans.

The Marcells, who have since resettled in suburban Atlanta,

had just bought the

house when Hurricane Katrina struck.

Erik S. Lesser for The New York Times

Katrina's Tide Carries Many to Hopeful

Shores NYT

23.4.2006

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/23/us/23diaspora.html

Rashad Ballard, 10,

a former resident of New

Orleans, on his way to school in suburban Atlanta.

Erik S. Lesser for The New York Times

Katrina's Tide Carries Many to Hopeful

Shores NYT

23.4.2006

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/23/us/23diaspora.html

Mr. Marcell tending to his daughter, Whitney,

who was born in February and

named after her father.

Erik S. Lesser for The New York Times

Katrina's Tide Carries Many to Hopeful

Shores NYT

23.4.2006

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/23/us/23diaspora.html

Katrina's Tide Carries Many to Hopeful

Shores

April 23, 2006

The New york Times

By JASON DePARLE

LITHONIA, Ga. One afternoon last August, a

young bus driver headed to an office in a suburb of New Orleans, humming the

song to an old television show. He arrived just before his wife, who was

pregnant with their first child and escorting four troubled teenagers from the

alternative school where she worked.

At 24, the driver, Whitney Marcell, weighed 300 pounds, and answered to the name

Big Man. His wife, Jeralyn, who goes by Fu, had just turned 28. She brought

along the hard-faced adolescents because her own hard life had presented her

with a gloriously teachable moment: Big Man and Fu, up-from-nothing products of

New Orleans's roughest projects, were about to buy their first home.

"Are you sure you can afford it?" friends had sniped, but Mr. Marcell's only

worry about the $86,500 loan was whether the terms would let him pay it off

early. The couple signed a pile of legal papers and left the office owning a

house in New Orleans' Lower Ninth Ward.

As he packed that night, Mr. Marcell returned to the song from "The Jeffersons,"

a sitcom about a dry cleaner and his wife who had risen to the black

bourgeoisie. Like his television heroes, George and Louise, Mr. Marcell crooned

about "moving on up," then startled himself by crying.

Two days later, Hurricane Katrina struck with biblical force, destroying the

Marcells' new home, and chasing them to the outskirts of Atlanta, where they

became part of the largest American diaspora since Dust Bowl days. But despite

the loss of nearly everything they owned, the Marcells say they have moved up

again.

The median household income in their new neighborhood is nearly twice that in

the Lower Ninth Ward, and more than four times that in the projects where they

had lived. Though they had recently worked their way out of poverty in New

Orleans, the Marcells say this mostly black suburb offers much safer streets,

better schools and a stronger economy.

The Marcells' journey illustrates one surprising benefit from an otherwise

terrible storm: the exodus took low-income families to areas richer in

opportunity.

The New York Times analyzed relocation patterns in 17 counties in and around

Atlanta and Houston, two leading destinations for Katrina evacuees. Like the

Marcells, the average evacuee has landed in a neighborhood with nearly twice the

income as the one left behind, less than half as much poverty, and significantly

higher levels of education, employment and home ownership.

Still, it is unclear whether a better environment will bring success, for the

Marcells or for others like them.

The Marcells say Atlanta has plenty of jobs, but seven months after the storm

they are still jobless. They praise the school their 10-year-old attends but put

much of their energy into his nascent rap career, as his reading scores lag. By

the time George Jefferson was "Moving on Up," he had seven dry-cleaning stores

and a "de-luxe apartment in the sky" not, as the Marcells do, unemployment

checks and subsidized housing.

Some Katrina families may be too traumatized to benefit from the moves. Others

may drift back to poor areas when government aid decreases. Even if they stay,

the new neighborhoods may make little difference. Other forces like family

structure, cultural heritage and personal motivation may do more to shape

success.

Nonetheless, the relocation of tens of thousands of low-income families creates

a grand experiment in class mixing. While the full effects will not be known for

years, Ms. Marcell is among those who think it will succeed. She was furious

with Barbara Bush last fall when the former first lady, seeming to ignore the

pain the storm had caused, said the evacuation was "working very well" because

most displaced families "were underprivileged anyway." Yet in calling Atlanta a

"land of opportunity," Ms. Marcell, from the other end of the class spectrum, is

making a parallel point.

Like many black New Orleanians, she has spent years listening to boosterish

accounts from friends and family in greater Atlanta. She insists there is no

going back. "Everybody we know who came up here got a nice-paying job and a

house," Ms. Marcell said. "We going to have our time to shine."

A Thriving Black Middle Class

DeKalb County, where the Marcells have settled, shines especially bright for

African-Americans. With a population that is 56 percent black, and an average

household income close to $50,000, it forms one of the nation's great showcases

for the black middle class.

Incorporating part of the city of Atlanta, the county spreads out 20 miles north

and east to subdivisions carved from dairy farms. A drug and crime zone runs

across a southwestern flank. The Marcells' apartment, in Lithonia, is on the

booming eastern edge.

It is a place that encourages African-Americans to think big. Among the local

growth industries is the New Birth Missionary Baptist Church, which claims

25,000 members, including the Marcells. In pushing a gospel of prosperity, New

Birth's pastor, Bishop Eddie L. Long, has practiced what he has preached. As

reported by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, his compensation from a charity

affiliated with the church topped $3 million over four years.

Three years ago, New Birth started a center for aspiring entrepreneurs. Darold

P. Honore Jr., one parishioner Bishop Long nurtured in business, arrived from

New Orleans two decades ago and is now Lithonia's part-time mayor. "It's

different from the Big Easy, where everyone's pretty much contented," Mr. Honore

said. "Here it's more or less moving and shaking."

To make his point, he offered a tour of subdivisions bulging with

10,000-square-foot homes, many occupied by Lithonia's black elite. A mile away,

all but spilling into the Marcells' apartment, is the four-year-old Stonecrest

Mall, which covers former pastureland with 1.3 million square feet of hotels,

restaurants and stores.

Growth is the region's secular religion. A half-century ago, Atlanta was a

second-string province the size of Birmingham, Ala. Now it is home to four

million people and the world's busiest airport, with a prosperity that crosses

color lines. Compared with blacks nationwide, the black population of greater

Atlanta is much better paid, much better educated and much more likely to be

raising children with two parents at home.

William Frey, a demographer at the Brookings Institution, found that since the

mid-1980's, more black New Orleanians have left for greater Atlanta than for any

other place. Among them was Mr. Marcell's mother, who was 17 when he was born.

She left him with his father's mother and joined the crowds in the out-bound

lane.

Up From the Mean Streets

Once the economic leader of the South, New Orleans has been in decline for at

least 100 years. The Marcells came of age there in an especially mean place and

time: public housing in the age of crack.

Over the last 25 years, the city had lost nearly one in five residents and one

in seven jobs. Seven superintendents had passed through the school system in 10

years. By the mid-1990's, no American city had a higher homicide rate. Raised in

the mayhem, the Marcells each clung to a fortifying thought: "I'm better than

this."

Home for Mr. Marcell was the St. Thomas project, a low-rise slum along the

Mississippi River near the mansions of the Garden District. When he talks of the

grandmother who raised him there, Mercedes Jackson, he dwells on two points: she

worked a lot as a hospital aide and prayed even more. "I cannot say I ever

saw a day when she did not get on her knees," he said.

His father, who had a job in a printing plant, lived nearby with a younger set

of children, and visited often. With a third of the St. Thomas apartments

vacant, trouble could hide anywhere. Mr. Marcell took to hiding, too, behind a

genial front that gave little away. "You can't show your teeth to every guy you

meet," he said. "Cause everybody not ready to be cool."

Ms. Marcell grew up in like fashion in a working poor family stuck in the

projects but steadied by faith. Her mother, Sherry Williams, raised six children

in the B. W. Cooper Homes as a nursing aide. Ms. Marcell's father, a roofer,

lived with the family into her teens, when her parents divorced.

Pregnant in the 10th grade, Ms. Marcell left school, but quickly earned a high

school equivalency degree and put her jauntiness to work as a waitress. To

improve her vocabulary, she had a younger sister, Keisha a future high school

valedictorian drill her on word lists. "I always was talking I won't say

like a thug but like a street person," Ms. Marcell said. "I knew I could talk

better."

Crack arrived midway through the Marcells' youths, turning the projects into

killing zones. A 9-year-old boy in Ms. Marcell's neighborhood lost his life to

an errant bullet just weeks after writing to President Bill Clinton "to stop the

killings." Among the items Keisha salvaged from the Katrina flood was her 2004

valedictory speech at John McDonogh High School, lamenting "evil and its wicked

ways," a reference to the day in her junior year when three teenagers with an

AK-47 executed a rival during gym class.

After finishing high school in 1999, Mr. Marcell joined his mother in DeKalb

County, where she had prospered as a medical billing specialist and married a

sheriff's deputy. But Mr. Marcell returned to New Orleans after a year and met

his future wife in a club.

Ms. Marcell recalls hearing God tell her she was looking into her husband's

face. "I asked him, did he have Christ in his life," she said. He asked her the

same. They married seven months later and started family life in the Cooper

project with Ms. Marcell's 6-year-old son, Rashad Ballard.

Though they worked a set of menial jobs, like parking cars and waiting tables,

they also started a series of entrepreneurial ventures: a house-cleaning

business, car detailing and a Friday night takeout service called "Big Man and

Fu's Suppers."

In 2004, the Marcells moved up him to a job as a city bus driver, her to a

counselor's post at a school for juvenile delinquents. Rashad, a shy schoolboy

off the stage but a dervish on it, started a rap career. After a few small-time

gigs, he appeared on the BET network last spring for a few seconds of background

dancing in a video by the rapper Chopper.

"We saw a massive change in our life just ahead," Ms. Marcell said. "Cause we

knew that Rashad's career was going to hit off."

With a combined income of more than $40,000, the Marcells discovered they could

get a mortgage, and they found a four-bedroom home last summer in the Lower

Ninth Ward. As they moved their belongings the day after the house settlement,

Hurricane Katrina rushed toward New Orleans. With Ms. Marcell four months

pregnant, they were in no mood to test the storm.

They left for Georgia that night, planning a short stay with Mr. Marcell's

mother. In time, most of their scattered family would join them outside Atlanta

25 people in seven apartments, one exit from Stonecrest Mall.

Neighborhoods of Hope

Like pellets from a shotgun blast, New Orleanians spread everywhere, filing

change-of-address cards from cities as distant as Anchorage and San Juan, P.R.

About 365,000 city residents fled; only about a quarter have returned.

Given the physics of race and class, there was reason to worry about where they

would land. Three-quarters of flood-zone residents were black, and nearly 6 in

10 were living on less than $30,000 a year. Nationally, such families tend to be

crowded together in areas long on crime, short on jobs and plagued by inferior

schools.

That is not the story of Katrina evacuees. In both Atlanta and Houston, their

neighborhoods look much like the region as a whole. Measured against where they

had lived in New Orleans, most find that a big step up.

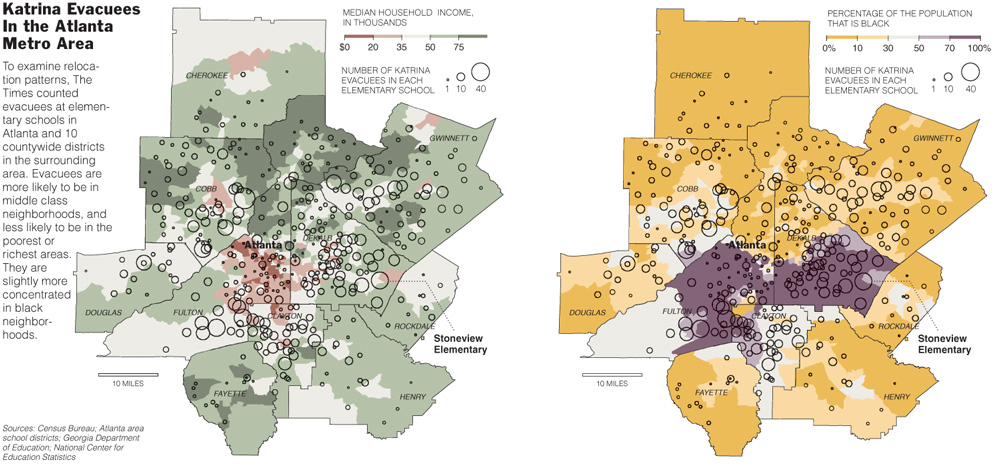

To examine relocation patterns, The Times counted evacuees at elementary schools

in metropolitan Atlanta and Houston: 13,000 students at 1,100 schools. Using the

schools as proxies for neighborhoods, The Times then analyzed the surrounding

Census Bureau tracts.

In both cities, the average evacuee lives in a place extraordinary only for its

ordinariness. Neighborhoods where evacuees settled have virtually identical

levels of education, employment and homeownership as the surrounding metropolis.

Those areas do have somewhat greater concentrations of minority residents and

single mothers, and slightly lower incomes. But they are no more prone to

outright poverty.

"It looks a lot better than I would have guessed," said Myron Orfield, a law

professor at the University of Minnesota who studies regional inequality. "I

would have guessed that Katrina families would have been relocated in tracts

much more disadvantaged and more segregated than the region as a whole."

Jesse Rothstein, a Princeton economist, agreed. "These are better neighborhoods

than I would have expected," Mr. Rothstein said.

The real contrast for evacuees is with the neighborhoods they have left behind.

In the flooded neighborhoods of New Orleans, annual household income was

$27,000. In the average evacuee's tract in Atlanta, it is $52,000.

In New Orleans, 42 percent of the neighborhood children were poor. In evacuee

tracts in Atlanta, the rate is 12 percent.

In New Orleans, about half the child-rearing families in the flood zones had

fathers in their homes. In evacuee tracts in Atlanta, nearly three-quarters do.

"I love New Orleans, don't get me wrong," Ms. Marcell said. "But I thank God we

are in Atlanta."

The pattern of resettlement may have been shaped in part by the success of

previous migrations. Some evacuees turned first to family or friends prosperous

enough to take them in, then settled nearby a subtle form of upward steering.

The Marcells are a good example. They started at Mr. Marcell's mother's house,

three exits away on Interstate 20 from where they live now. Since the Marcells

were still on the public housing rolls they had not officially left the

projects they received a voucher from the federal government for 18 months'

rent at a private apartment. They wanted one near a good school, and a friend

suggested Stoneview Elementary.

On a recent morning, Rashad left home just past 8 looking like a cover of Vibe

magazine, with a Pepe Jeans jacket and Size 4 Timberland boots. His back bent

from a bulging pack, he walked three blocks to school and entered a classroom

trailer, where his teacher, David Smith, fussed at his fourth-grade charges.

"Remember: a person who will not read ... " Mr. Smith began.

A chorus roared back: "... is no better than a person who cannot read!"

Demographically, Stoneview fits the stereotype of a troubled urban school. More

than 90 percent of its students are black, and 85 percent receive a subsidized

lunch. Only 23 percent of fifth graders exceed state standards on reading tests,

about half the metro average.

Still, a tone of crisp purpose is set by its principal, Farrell Young. Parents

from New Orleans marvel at the automated phone calls they get whenever a student

fails to check in. While few Stoneview students ace the reading test, 81 percent

pass it, not far off the metropolitan Atlanta average of 89 percent.

Among evacuees, it is an article of faith that the local schools far surpass

those back home. For Ms. Marcell, Exhibit A is Mr. Smith, who has been quick to

call her whenever Rashad seems down. "Mr. Smith really cares," Ms. Marcell said.

By the time the bell rang, Rashad had crowded onto the floor beside classmates

to imagine a slave ship's hold; written a paragraph about ice cream; divided

4,133 by 5; and learned a mnemonic to track the inner planets of Mercury, Venus,

Earth and Mars: "M-Vem."

"What's the name of that big college in Massachusetts I want y'all to go to?"

Mr. Smith asked. "When y'all go off to Haah-vaaad, remember 'M-Vem.' "

Two Sides of Resettlement

Can better neighborhoods rescue the poor? Or will bad luck and habits follow

wherever they land?

Optimists may note that the United States was built on the promise of fresh

starts, from the Pilgrims of Plymouth Rock to Pakistani cab drivers in Queens. A

change of address has turned prairie nobodies into California gold-strike kings,

and a Mississippi migrant named Oprah Winfrey into a Chicago billionaire.

Yet migrant lore also includes its special brand of the blues, the lament of

those who discover the streets are not paved with gold.

Don Wilson is one Stoneview parent who thinks Atlanta sparkles. Since arriving

seven months ago, he has landed a job and then a promotion, to sales manager for

Global HealthCare Systems, a company that sells discount cards for medical

services. He said he was earning 25 percent more than he did in New Orleans as a

recruiter for a technical school. "I get to make someone's life better, and at

the same time be prosperous," Mr. Wilson said.

A New Orleans native, Mr. Wilson moved away, returning five years ago at the age

of 40 to find a stagnant city with few prospects for blacks. In Atlanta, he sees

black achievers everywhere.

"It's nothing to see people driving around in Mercedes, and they look like you,"

he said. "They're black. That tells you that you could do it."

"I love the environment," Mr. Wilson said. "I'm really happy."

Sheba Akmin's reaction could not have been more different. Landing in Lithonia,

Ms. Akmin, a 30-year-old hairdresser, dropped five dress sizes and developed

stomach ulcers. She missed home so much she drove to New Orleans just to buy

groceries, returning from the 12-hour round trip with king cakes, Bunny Bread,

smoked sausages and a stash of filι powder.

"I wasn't familiar with the food in Atlanta," she said.

The bustle that excites Mr. Wilson left Ms. Akmin drained. She was appalled that

her neighbors did not know one another's names, and wounded by the rejection she

got when applying for jobs. "People in Atlanta is bougie they stuck up," she

said. "Everybody is for themselves. It's zoom, zoom, zoom."

In March, her boyfriend, a cook, reclaimed his job at a New Orleans restaurant,

and she raced back home with him. "I know there was opportunity for me" in

Atlanta, she said. "But all I did is cry."

Katrina families differ from the classic American migrant in at least one

important way: they did not choose to move. Simply by deciding to strike out

from home, the immigrant of lore has already shown much of the drive needed to

succeed. Evacuees' ambitions, unlike their neighborhoods, cannot be quantified.

Anthony Hall, another Stoneview parent, has enrolled in DeKalb Technical School,

but warned: "A lot of people right now are waiting around. You got to get that

out of your mind; Oprah can only help so many people."

Migrants typically prosper most in places with prosperity to share. That is why

Atlanta and Houston, with more jobs at higher pay, hold a promise that New

Orleans lacked. But migrations are shaped by the migrants, too, their culture,

character and connections.

Social networks are especially important. Newcomers tend to thrive where they

have friends. Mr. Wilson, the medical-card salesman, found his job through his

New Orleans church, which had formed an Atlanta congregation. Ms. Akmin was

isolated. "I didn't know anybody," she said.

Local reaction can also shape migrants' success. Greater Houston has more than

100,000 evacuees, whose presence is a source of growing strain. A series of high

school brawls has pitted evacuees against local rivals, and displaced New

Orleans gangs have been blamed in part for a surge of homicides. Mayor Bill

White led a welcoming effort, but public sentiment is turning against evacuees.

Even in metropolitan Atlanta, which has about a third as many evacuees as

Houston, many complain they are being labeled freeloaders or criminals.

For all the promise of the new neighborhoods, other problems can get in the way.

The troubled New Orleans schools, for one, may have left students too far behind

their new peers.

Texas officials have estimated that Katrina students, on average, lag their new

classmates by at least a full grade. In Lithonia, standardized tests show Rashad

reading two years below his grade level, even though he got A's and B's back

home.

The move up may also prove short-lived if evacuees are forced into worse areas

or if their current neighborhoods decline. Reviewing the Times data, Professor

Orfield, the Minnesota scholar, saw one warning sign: evacuee schools looked

worse than evacuee neighborhoods. They have more low-income students than

schools regionwide, more minorities and lower test scores. That is worrisome, he

said, because "the schools resegregate first and the neighborhoods tend to

follow."

In Atlanta, the tipping appears to have begun, according to the Times analysis.

In the average evacuee's neighborhood, the black and Hispanic population grew to

49 percent in 2000 from 31 percent in 1990. Single motherhood also rose, and the

employment rate declined.

Another possibility is even more fundamental: what if neighborhoods matter less

than commonly thought? As far back as Jacob Riis, the 19th-century crusader

against slums, experts have argued that bad neighborhoods perpetuate poverty,

steeping the poor in bad influences while walling them off from good schools and

jobs.

In making a parallel case, contemporary social scientists have been particularly

influenced by the Gautreaux program in Chicago, which moved black families from

public housing into white suburbs, where more adults found jobs and more

children went on to college. Gautreaux began in 1976 and lasted two decades.

But a successor program, Moving to Opportunity, failed to replicate the results.

Operating in five cities in the 1990's, the program moved public-housing tenants

of all races into neighborhoods with less poverty. An evaluation, published

three years ago, showed that the transplanted adults neither worked more nor

earned more than those who had stayed behind.

"The process of neighborhood influence appears to be more subtle and complex

than most of us thought," said Jeffrey Kling, a Brookings scholar who helped

evaluate the program.

Moving to Opportunity produced one clear benefit: it left the transplanted

families feeling much safer. After years of housing-project violence, the

Marcells revel in a similar sense of safety. "It's a relief to be someplace

where people's not shooting," Mr. Marcell said.

One reason for the otherwise disappointing results may have been the modesty of

the moves. Most Moving to Opportunity participants landed in areas only

marginally better than those they had left; having moved farther up the

neighborhood ladder, Katrina evacuees may reap bigger benefits.

Another explanation is that influences like family dynamics or cultural mores

may matter more than neighborhoods. Among those tacitly making that case was

Rashad's teacher, Mr. Smith, who recently transferred to a nearby school.

When Mr. Smith moved to DeKalb six years ago, he sought a school like the one

where he had taught in Savannah, Ga., filled with the children of Asian

immigrants. "You talk about students who want to learn! I was drooling!" he

said. Asked how Stoneview students compared, he paused, then said, "I don't

think education is stressed, or stressed enough."

'Go-Getters' With a Dream

Ms. Marcell answers talk of potential pitfalls with a forecast of success,

"because we are some go-getters." But with both Marcells still unemployed, the

go-getters have yet to get going.

Mr. Marcell said he initially delayed a job search to stay at home with his

pregnant wife. Then he applied at four stores, a restaurant and several gas

stations, he said, without getting hired. He did reject an offer to drive a bus

three days a week, saying he was put off by the part-time schedule. He added, "I

really don't know about bus driving down here; the streets are kind of narrow."

Now with his unemployment benefits extended, he is postponing his job search to

focus on Rashad's career. "I'm trying to help my son pursue his dreams," he

said.

Ms. Marcell also turned down a job, as a helper at a day care center; she

decided to postpone work until she had the baby. Whitney Mercedes Marcell, a

girl, arrived on Feb. 7, and Ms. Marcell said she planned to find a job when her

daughter turns three months old.

In the meantime, she has revived a previous business plan, pitching kitchen

cabinets to the New Orleans housing authority. Officially still one of its

tenants, she has an edge when bidding on the agency's contracts. Teaming up with

a Mississippi manufacturer, she thought she had her first deal just before the

storm, a renovation of 36 apartments that would have brought her a fee of 7

percent, or about $15,000.

With much of the city's public housing in need of reconstruction, Ms. Marcell is

trying to finalize that deal and land new ones. "I'm not going to let this go,"

she said. "I worked too hard for it."

Though jobless, the Marcells are not destitute and have been able to replace

much of what they lost to the flood. They have a new wide-screen television, a

new computer and a new living-room suite. Last fall, Mr. Marcell's 1992 Chevy

Suburban was stolen. Though it was uninsured against theft, he bought a newer

model, and added a DVD player.

"We are a hard-working family," Mr. Marcell said. "We feel entitled to live

comfortable."

The $400 a week they get in unemployment checks replaces only about half their

former take-home pay. But insurance paid off their mortgage (giving them title

to the land). And with their housing voucher they pay no rent. In net terms, the

rough numbers provided by the Marcells show that their income has fallen by

about $175 a week or by about $5,300 over seven months.

Against that, they have received more than $7,000 in lump-sum payments from the

Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Red Cross and relatives. And the

Marcells said they arrived in Atlanta with about $8,000 in savings. "That's what

we're really cutting into now," Mr. Marcell said.

Others in their family are off to a similarly slow job hunt. "I'm going to wait

until my little unemployment check runs out" before going back to work, said Ms.

Marcell's mother, who collected $10,000 from FEMA for the contents of her

flooded apartment. After two decades in nursing homes, she said, "I was tired of

working like a dog."

After 26 years in a printing plant, Mr. Marcell's father, Widdon Jackson, is

collecting unemployment. Keisha, the valedictorian, was in college back home,

but after months in Atlanta without work or school, she left for Houston.

The career the Marcells seem most focused on now belongs to Rashad, who raps

under the name Lil' Chucky.

"I just hope that people like Oprah Winfrey, people like Puff Daddy, will get a

chance to hear his cry," Mr. Marcell said.

" 'Shad got a good career going," said Mr. Marcell's father. "He going to make

his family rich!"

Their spirits soared a few months ago when Mr. Marcell got Rashad on the stage

at an awards show, just yards from the rap star Ludacris. Not long after that, a

bigger break seemed to appear in the form of an electronic beat, a percussive

track over which original lyrics can be dubbed. The beat, recorded by an

engineer named Vaughn Pacsch'l but known as Afro, borrowed its refrain from

another black sitcom, "Good Times."

"As soon as I heard that beat, I said this is the one," Mr. Marcell said. A good

beat can sell for $1,000 or more; Afro agreed to sell three for $500, including

"Good Times," and tape Rashad's version of the song.

For weeks, the Marcells honed their lyrics, mixing nostalgia for home with

criticisms of FEMA's response to the hurricane. "Good Times" became "Good

Tymez."

The night of the taping, everyone was tense. Mr. Marcell idled the Suburban in a

gas station parking lot and ran Rashad through practice takes. Ms. Marcell

returned from the station's cash machine and counted out the money she owed

Afro. Rashad, still awaiting dinner, kept messing up his lines. "Get more

aggressive!" Mr. Marcell said.

Shortly before 8 p.m., the Suburban rumbled into a trim subdivision where Afro

answered the door in tinted glasses and braids. His wife a nurse hoping to

make it as a singer introduced herself as Oracle, then said her real name was

Destiny.

Hat cocked, pants loose, ablaze with cubic zirconium, Rashad arrived with more

bling than zing. He looked pooped. "Go in the corner, get in your zone," Mr.

Marcell said. "You're going to be hitting this mike in a second."

"What's wrong with you?" asked Ms. Marcell. "Loosen up."

Rashad did a 360-degree turn, splayed his legs, and lifted an arm, as though

crowning himself with an exclamation point.

"Let's run it," Afro said.

Rashad flubbed his first line.

"Show some more aggression!" Mr. Marcell said.

Rashad missed the second take. His timing was off on Takes 3 and 4. He garbled

the words on Take 5.

"Come on," said his mother. "Let's nail this!"

Katrina left my city flat

But I'm about to bring it back

And we going to have a good time!

"That's it!" Ms. Marcell said.

Mr. Marcell glowed and growled out a verse.

Man the government is so lazy

But if I woulda lost my wife and my unborn baby

I woulda went crazy.

"You sound really mad at Bush!" Ms. Marcell laughed. "You sound like Tupac!"

"It's 4:09 radio friendly," Afro said.

It was almost 10 p.m., and Rashad had school in the morning.

"I'm a go home, take a bath, and go straight to bed," he said to no one in

particular. Retakes followed, and lots of waiting, as Afro adjusted the mix. By

10:30, Rashad was asleep on the floor, and Mr. Marcell soon fell asleep there,

too, after pledging to get the finished disc to a radio station first thing in

the morning.

He dropped it off a few days later, but it was never broadcast.

Still, the evening left Ms. Marcell jazzed. She sat up past midnight telling

Destiny her dreams, as Afro spun the dials, searching for the elusive formula

for success.

Matthew Ericson and Alain Delaquιriθre contributed research for this

article.

Katrina's Tide Carries Many to Hopeful Shores, NYT, 23.4.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/23/us/23diaspora.html?hp&ex=1145851200&en=1c8633cc9a0b1bdd&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Storm Evacuees Are Straining Texas Hosts

April 20, 2006

The New York Times

By JENNIFER STEINHAUER

HOUSTON, April 15 To the long list of

adjectives used to describe Texans since last summer's hurricanes munificent,

intrepid, scrappy add one more: fed up.

Seven months after two powerful hurricanes blew through the Gulf Coast, elected

officials, law enforcement agencies and many residents say Texas is nearing the

end of its ability to play good neighbor without compensation.

Houston is straining along its municipal seams from the 150,000 new residents

from New Orleans, officials say. Crime was already on the rise there before the

hurricane, but the Houston police say that evacuees were victims or suspects in

two-thirds of the 30 percent increase in murders since September. The schools

are also struggling to educate thousands of new children.

To the east of here, Texans argue that Hurricane Rita, which took an unexpected

turn away from Houston shortly after Hurricane Katrina last fall to wreak havoc

from Jasper to the northeast to Sabine Pass near the Louisiana border, has been

forgotten in the swirl of attention given to the devastation in New Orleans.

In fact, they say, the nation never really took notice of the 77,000 homes made

uninhabitable by Hurricane Rita's force, 40,000 of which were not insured, or

the piles of debris and garbage that still fester along the roads. "Personally I

am sick of hearing about Katrina," said Ronda Authement, standing outside her

trailer in Sabine Pass, where she will live until she can get the money and the

workers to put her three-bedroom house back on its foundation. "I would like to

throw up, frankly, hearing about Katrina."

In its frustration, Texas has thrown its hat in the great Congressional money

game, arguing vociferously for federal money to help pay for new police officers

in Houston, where the force has dwindled in recent years, and to repair homes in

East Texas, where many poor residents lack the means and the insurance to do it

on their own.

Though the state has requested $2 billion in federal aid to pay for law

enforcement, education and housing, state officials say they have received only

$22 million so far.

"We were told we would be taken care of by everybody on the federal level," said

Chris Paulitz, a spokesman for Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison, Republican of

Texas, who recently helped get $380 million in aid added to President Bush's

latest supplemental request for Texas. "But clearly that isn't the case. Texas

opened its doors and hearts, and that is something we will continue to do today.

However, we need to be reimbursed."

Houston's relationship with its added population is subtle and at times

ambivalent. Residents, atomized over a broad swath of land with few

interneighborhood connections, seem at one level to be dedicated to helping

their neighbors, and are quick to cite numerous examples of continued

volunteerism and the improved lives of children who they say are getting a

better education than they received in New Orleans.

But they are also keenly aware of spikes in crime, especially in Southwest

Houston, where the majority of the poorest New Orleanians settled.

"The city of Houston bent over backwards for these people, and I am glad we did

it," said Scott Wilson, 43, who lives in the Montrose section. "But now we are

absorbing some of their problems."

Evacuees have been victims of or accused of committing 39 of the 235 murders in

Houston since last September, said Houston's police chief, Harold Hurtt. In

January alone, there was a 34 percent rise in felonies over the previous year in

the city.

"I can't tell you what percentage of that group is evacuees," Chief Hurtt said.

"But I am sure they are really represented in that group."

Chief Hurtt said that some of the gangs that once operated in New Orleans

housing projects had relocated to Houston, a city plagued with its own gang

problems.

In response, the city moved 100 officers working in city jails to high-crime

areas, and greatly increased overtime, a tall order for a department that has

lost 800 officers to retirement over the last two years.

The city has asked the federal government for $77 million to hire 560 officers

over five years. At Senator Hutchison's request, the Department of Justice

recently sent the Police Department $20 million to help pay for patrolling

high-crime areas.

The Houston public school system, with about 208,000 students, also wants money

to pay for more teachers, additional facilities and tutoring help for its

roughly 30,000 evacuee children. The New Orleans schools, surrounded by far

greater poverty than Houston, are among the nation's most troubled.

Houston's school system has also experienced fighting between local and New

Orleans students in its schools 27 students from the two sides were arrested

in one melee but school crime is down over all.

"It has been a challenge," said Terry Abbott, a spokesman for Houston

Independent School District, "but generally the vast majority of the children

are well behaved and many are grateful to be here."

But results on standardized tests suggest that "the students from Louisiana were

substantially behind the Texas kids," Mr. Abbott said.

"We have asked the state government for resources to get them up to speed," said

Mr. Abbott, with an eye toward regulations of the federal No Child Left Behind

law. "That will be a concern, but these children are ours now, and we don't look

at them in any other way."

In East Texas, state officials are seeking roughly $1 billion in new federal

block-grant money to house people whose homes were destroyed by Hurricane Rita.

Texas officials concede that their coast was not pummeled nearly as badly as

their neighbors in Louisiana, but they argue that their residents did not

evacuate and were now trying to live in squalid, mold-infested conditions.

"I have been to the Ninth Ward," said Mark Viator, chairman of the Recovery

Coalition of Southeast Texas, speaking of the most devastated neighborhood in

New Orleans. "There is debris in the Ninth Ward, but you don't have people. We

say, send the money where the people are."

Henry Bowie, who lives in Port Arthur, a city with high unemployment and many

poor residents, is the sort of person Mr. Viator thinks should get federal

housing money. His house is a patchwork of broken roofing, and light is visible

through the floorboards because the house is off its foundation. Black mold

grows up the sides of the walls, but Mr. Bowie, who undergoes dialysis three

times a week, remains there with his wife and teenage son.

Not everyone is sympathetic to the needs of Texas, where oil refinery businesses

continue to take in millions of dollars in profits monthly, even though state

officials say they do not have enough workers because of a housing shortage. In

testimony at a recent appropriations hearing, Senator Christopher S. Bond,

Republican of Missouri, said he did not believe Texans needed housing money.

"Texas, in the best role of traditional Judeo-Christian charity, provided

benefits," Mr. Bond said. "I think it's time we get back to being a good

neighbor and not a paid companion."

Senator Hutchison, who spoke next, was not amused.

Mayor Guy N. Goodson of Beaumont, where thousands of homes were damaged, said he

would like to see federal reimbursements for debris removal there rise to 90

percent of costs from 75 percent, equaling what it was in Louisiana. Mayor

Goodson said his area suffered inattention because its residents had done the

right thing: evacuating and rebuilding without complaint after Hurricane Rita

cut its path.

"There is a great disjoinder in people's minds about disaster," he said. "You

see wildfires, you see a tornado, and who can forget the pictures of the Ninth

Ward. A vast majority of our area is wind damage. And unfortunately from a

sensory standpoint, people just don't coordinate these two very similar

disasters."

Storm

Evacuees Are Straining Texas Hosts, NYT, 20.4.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/20/us/nationalspecial/20texas.html?hp&ex=1145592000&en=da2f7e910d4474dc&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Storm Evacuees Found to Suffer Health

Setbacks

April 18, 2006

The New York Times

By SHAILA DEWAN

Families displaced by Hurricane Katrina are

suffering from mental disorders and chronic conditions like asthma and from a

lack of prescription medication and health insurance at rates that are much

higher than average, a new study has found.

The study, conducted by the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia

University and the Children's Health Fund, is the first to examine the health

issues of those living in housing provided by the Federal Emergency Management

Agency. Based on face-to-face interviews with more than 650 families living in

trailers or hotels, it provides a grim portrait of the hurricane's effects on

some of the poorest victims, showing gaps in the tattered safety net pieced

together from government and private efforts.

Among the study's findings: 34 percent of displaced children suffer from

conditions like asthma, anxiety and behavioral problems, compared with 25

percent of children in urban Louisiana before the storm. Fourteen percent of

them went without prescribed medication at some point during the three months

before the survey, which was conducted in February, compared with 2 percent

before the hurricane.

Nearly a quarter of school-age children were either not enrolled in school at

the time of the survey or had missed at least 10 days of school in the previous

month. Their families had moved an average of 3.5 times since the storm.

Their parents and guardians were doing no better. Forty-four percent said they

had no health insurance, many because they lost their jobs after the storm, and

nearly half were managing at least one chronic condition like diabetes, high

blood pressure or cancer. Thirty-seven percent described their health as "fair"

or "poor," compared with 10 percent before the hurricane.

More than half of the mothers and other female caregivers scored "very low" on a

commonly used mental health screening exam, which is consistent with clinical

disorders like depression or anxiety. Those women were more than twice as likely

to report that at least one of their children had developed an emotional or

behavioral problem since the storm.

Instead of being given a chance to recover, the study says, "Children and

families who have been displaced by the hurricanes are being pushed further

toward the edge."

Officials at the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals said the study's

findings were consistent with what they had seen in the field.

"I think it told us in number form what we knew in story form," said Erin

Brewer, the medical director of the Office of Public Health at the department.

"We're talking about a state that had the lowest access to primary care in the

country before the storm. And a population within that context who were really,

really medically underserved and terribly socially vulnerable."

Ms. Brewer said that some of the trailer sites were regularly visited by mobile

health clinics, but acknowledged that such programs were not universally

available. Neither Congress nor the State of Louisiana eased eligibility

requirements for Medicaid after the storm, and because each state sets its own

guidelines, some families who received insurance and food stamps in other states

were no longer eligible when they returned home.

While state officials said $100 million in federal block grants was in the

pipeline for primary care and mental health treatment, the study's authors said

the need was urgent.

"Children do not have the ability to absorb six or nine months of high levels of

stress and undiagnosed or untreated medical problems" without long-term

consequences, said Dr. Irwin Redlener, the director of the National Center for

Disaster Preparedness at Mailman and co-founder of the Children's Health Fund.

The households included in the study were randomly selected from lists provided

by FEMA. They included families living in Louisiana in hotels, trailer parks

managed by the disaster agency and regular trailer parks with some FEMA units. A

random sample of children in the surveyed households was selected for more

in-depth questioning.

For comparison, the study used a 2003 survey of urban Louisiana families

conducted by the National Survey of Children's Health.

David Abramson, the study's principal investigator, said it was designed to

measure the social and environmental factors that help children stay healthy:

consistent access to health care and mental health treatment, engagement in

school, and strong family support.

In the Gulf Coast region, where child health indicators like infant mortality

and poverty rates were already among the highest in the country, Dr. Abramson

said, "all of their safety net systems seem to have either been stretched or

completely dissipated."

The study's authors raise the prospect of irreversible damage if children miss

out now on normal development fostered by stable schools and neighborhoods.

One couple told interviewers their three children had been enrolled in five

schools since the hurricane, in which one child's nebulizer and breathing

machine were lost. The equipment has not been replaced because the family lost

its insurance when the mother lost her job, they said, and the child has since

been hospitalized with asthma.

In another household, a woman caring for seven school-age grandchildren, none of

whom were enrolled in school at the time of the survey, said she was battling

high blood pressure, diabetes and leukemia.

That woman, Elouise Kensey, agreed to be interviewed by a reporter, but at the

appointed hour was on her way to the hospital, where she was later admitted.

"I've been in pain since January, and I'm going to see what's wrong," she said.

"It's become unbearable."

One woman who participated in the survey, Danielle Taylor, said in an interview

that she had not been able to find psychiatric care for herself she is bipolar

or her 6-year-old daughter, who not only went through the hurricane but had

also, two years before, been alone with Ms. Taylor's fiancι when he died.

The public clinic Ms. Taylor used to visit has closed since the storm, she said,

and the last person to prescribe her medication was a psychiatrist who visited

the shelter she was in four months ago. No doctors visit the trailer park in

Slidell, La., where she has been staying, she said.

Ms. Taylor said that her daughter, Ariana Rose, needed a referral to see a

psychiatrist, but that her primary care physician had moved to Puerto Rico. "She

has horrible rages over nothing," Ms. Taylor said. "She needs help, she needs to

talk to somebody."

The survey found that of the children who had primary doctors before the storm,

about half no longer did, the parents reported. Of those who said their children

still had doctors, many said they had not yet tried to contact them.

The study's authors recommended expanding Medicaid to provide universal disaster

relief and emergency mental health services, as well as sending doctors and

counselors from the federal Public Health Service to the region.

The Children's Health Fund, a health care provider and advocacy group, is not

the only organization to raise the alarm about mental health care for

traumatized children after Hurricane Katrina. A report issued earlier this month

by the Children's Defense Fund said youngsters were being "denied the chance to

share their bad memories and clear their psyches battered by loss of family

members, friends, homes, schools and neighborhoods."

Anthony Speier, the director of disaster mental health for Louisiana, said that

while there were 500 crisis counselors in the field, the federal money that paid

for them could not be used for treatment of mental or behavioral disorders like

depression or substance abuse. Instead, he said, much of their effort goes into

short one-on-one sessions and teaching self-help strategies in group settings.

"The struggle for our mental health system is that our resources are designed

for people with serious mental illnesses and behavior disorders," Dr. Speier

said. "But now the vast population needs these forms of assistance."

Dr. Speier continued, "What we really from my vantage point could benefit from

is a source of treatment dollars."

According to the study's authors, the post-storm environment differs

significantly from other crises because of its uncertain resolution.

"This circumstance is being widely misinterpreted as an acute crisis, somehow

implying that it will be over in the near term, which is categorically wrong,"

Dr. Redlener said. "This is an acute crisis on top of a pre-existing condition.

It's now a persistent crisis with an uncertain outcome, over an uncertain

timetable."

Storm

Evacuees Found to Suffer Health Setbacks, NYT, 18.4.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/18/us/nationalspecial/18health.html?hp&ex=1145419200&en=edb50eb873106f34&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Craving a Voice, New Orleanians Take to the

Road to Cast Ballots for Mayor

April 11, 2006, 2006

The New York Times

By ADAM NOSSITER

LAKE CHARLES, La., April 10 Monday was the

first day for early voting in the New Orleans mayor's race, and all over

Louisiana and Texas, dislocated residents rose before dawn and drove for hours

to cast their ballots at 10 satellite voting centers.

The unusual arrangement, established after weeks of political wrangling in

Louisiana, is expected to accommodate thousands of New Orleanians separated from

their city by Hurricane Katrina yet eager for a voice in the political process.

On Monday, 1,402 people throughout Louisiana took advantage of early voting,

with more than half casting ballots in New Orleans. After the early voting this

week, regular voting in the city will take place April 22, with a runoff

expected in May.

Here at the state's western edge, buses and vans brought 112 people from Houston

and San Antonio to the Calcasieu Parish courthouse, transformed into a voting

precinct for the battered city 200 miles to the east.

Though bleary-eyed, none said they regretted the early awakening.

"I would have spent the night in the parking lot if I had had to," said Debra

Campbell, who got up at 4:30 a.m. to be on one of the two buses from Houston.

"We just need help. We need help getting our homes together."

Ms. Campbell, a former resident of the city's Seventh Ward, had never lived

outside New Orleans. "Please believe us, we're suffering," she said.

Patiently, the voters all of them black lined up in the courthouse corridor

to fill out their paper ballots, then get back on the buses and vans for the

nearly three-hour ride back to Houston or the six-hour trip to San Antonio. The

bus and van trips were organized by the Association of Community Organizations

for Reform Now, or Acorn, a national advocacy group.

Early voting centers were also set up in Shreveport, Lafayette, Baton Rouge and

smaller cities. New Orleans was the only place besides Lake Charles where

election officials reported a brisk turnout.

Many of Monday's voters, jammed into small apartments far from home with no

house to return to and angry at the slow pace of recovery in New Orleans, said

this vote was the most significant they had ever cast.

"This is the most important ballot of my life," said Gilda Burbank, a former

community outreach worker at a New Orleans church. "I want to come home. I mean,

I want to come home. I mean, every day, I want to come home. This is the first

step. I'm so hopeful."

The election is widely viewed as a potential turning point for New Orleans, with

the changing demographics since the storm raising the possibility that a white

mayor could be elected there for the first time in a generation.

None of the voters talked to here on Monday mentioned this, but several said

they were voting for the leading black candidate, the incumbent C. Ray Nagin,

saying he had been unfairly blamed for problems after the hurricane.

"If he's going to be knocked out of office, you need to remove everybody," said

Verlean Davis, who came from San Antonio and whose home and possessions in

eastern New Orleans had been "totally wiped out."

Mr. Nagin has retooled his political approach for this election, appealing

directly to black voters for the first time. In his first campaign, white voters

gave him his winning margin.

Cara Harrison, a displaced resident of the Ninth Ward, said a defeat for Mr.

Nagin would represent a setback for blacks.

"For the working poor, and the African-American community, he's our best voice,"

said Ms. Harrison, who drove from Houston with her sister and was among the

first to vote.

Others said, however, that they would vote for Lt. Gov. Mitch Landrieu, a white

who has emphasized assembling a biracial coalition.

"Everybody needs this election, to put in somebody who's going to do something

for New Orleans, so people can start rebuilding," said Marie Moss, a Kmart sales

clerk washed out of her home in eastern New Orleans, who said she would vote for

Mr. Landrieu.

With many voters displaced, candidates have had to travel far afield to

Atlanta, Houston and Dallas, principally to make their appeals. Despite

intense interest in the election at home, with heavy turnouts at mayoral forums,

the candidates have mostly kept to a safe script.

The vote is likely to come down to race, analysts say, with the big question

being whether Mr. Landrieu can attract enough black support to put him over the

top in the anticipated runoff.

At a forum in New Orleans on Saturday that was broadcast live to New Orleanians

staying in Texas, Georgia and North Carolina, candidates were asked whether they

would restore services immediately to all the city's neighborhoods. All the

major candidates said it would be unrealistic to do so, given the city's

crippled tax base.

But they all said they would work to bring citizens home, the aspiration of

virtually all those who made the trip here Monday.

"All of our New Orleans people are distributed throughout all the states," said

Linda Lacey, a voter formerly of the Eighth Ward. "I was born and raised there.

We need to go back."

Craving a Voice, New Orleanians Take to the Road to Cast Ballots for Mayor, NYT,

11.4.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/11/us/nationalspecial/11orleans.html

New Orleans candidates court hurricane

evacuees

Sat Mar 25, 2006 6:34 PM ET

Reuters

By Erwin Seba

HOUSTON (Reuters) - New Orleans city election

campaigns are being waged where the voters are -- in cities like Baton Rouge,

Houston, Dallas and Austin, where many residents ended up after being scattered

by Hurricane Katrina.

Mayoral candidates including incumbent Ray Nagin and leading rivals Democratic

Lt. Gov. Mitch Landrieu and Audubon Nature Institute President Ron Forman have

traveled to meet with evacuees still living outside their devastated city, which

exceed the number of people who have returned.

Forman, who has raised the most money of any mayoral candidate, said between

one-quarter and one-third of his $1.6 million war chest would go to reaching

out-of-town voters through travel to as many as seven cities, newspaper

advertising, direct mail and e-mail.

No candidate can afford to ignore voters whether they are in New Orleans or

outside the city, Forman told Reuters on Saturday.

"It's both," he said. "This could be the most important election in the history

of our city."

The campaign revolves around a controversial rebuilding plan supported by Nagin

that foresees a population less than half of the 500,000 who lived in New

Orleans before Katrina struck on August 29.

About 180,000 people were estimated to be living in the city in January,

according to city emergency officials. The Federal Emergency Management Agency

counts 106,000 New Orleans residents living in Baton Rouge and 69,000 in

Houston. More than 100,000 others are scattered around the country.

The hurricane killed about 1,300 people along the Gulf Coast and 2,000 people

are still listed as missing.

In Houston, using FEMA lists, volunteers carrying clipboards are knocking on

doors in large apartment complexes on the southwest side of the city that

Houston Police Chief Harold Hurtt has identified as hotbeds of criminal

activity.

"Some of them are very rough," said volunteer Glenda Harris.

THREE-HOUR BUS RIDE TO VOTE

The volunteers, sponsored by local and national nonpartisan political

organizations, have signed evacuees up for absentee ballots or bus rides to

satellite polling stations Louisiana officials plan to place in Lake Charles,

Louisiana, three hours east of Houston.

But the voter registration and education campaign may determine the outcome of

the April election in which 24 candidates are running for mayor in addition to

about seven candidates for each of seven City Council seats.

"Houston by itself could decide who is mayor in New Orleans," said Barbara

Waiters, who evacuated from the Algiers neighborhood ahead of Katrina and

expects to live in Houston for at least another year.

The rebuilding plan is seen as the key to which ethnic groups will decide the

future of New Orleans.

William Falk, a University of Maryland sociologist who has studied black

population trends, said New Orleans may have a majority white population for

years to come.

The 2000 U.S. Census showed blacks made up two-thirds of the city's population.

"We cannot imagine a majority-black city for a long time to come, barring some

miraculous turnaround," Falk said at a New Orleans sociology conference on

Friday, according the New Orleans Times-Picayune.

New

Orleans candidates court hurricane evacuees, R, 25.3.2006,

http://today.reuters.com/news/newsArticle.aspx?type=domesticNews&storyID=2006-03-25T233356Z_01_N25230036_RTRUKOC_0_US-HURRICANES-VOTERS.xml

Evacuees' Lives Still Upended Seven Months

After Hurricane