|

History > 2006 > USA > Environnement > Water

The Delta-Mendota Canal in California

supplies water to farmers in the San Joaquin Valley.

Some may be able to make

money reselling it.

Jim Wilson/The New York Times

March 2, 2006

For Thirsty Farmers, Old Friends at Interior

Dept. NYT

3.3.2006

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/03/national/03water.html

As Aquifer Runs Dry,

L.I. Water Debate

Ensues

December 2, 2006

The New York Times

By BRUCE LAMBERT

Thousands of years ago, rain fell on Long

Island and seeped hundreds of feet through the sandy soil, coming to rest on

bedrock. It formed what geologists call the Lloyd aquifer, the island’s oldest,

deepest, purest — and scarcest — groundwater.

Now, after 60 years of virtually unchecked suburban growth and consumption of

the island’s most precious resource, public officials and civic groups are

fighting over control of the remaining water supply. It is as if these were the

island’s last drops to drink, which is precisely what environmentalists insist

the aquifer should be reserved for.

The battle over the aquifer underscores the broader debate over Long Island’s

entire water supply for its nearly three million residents and future

development. Preservationists warn that if the island continues on its present

path, it will run out of clean water, while other experts are equally insistent

that there is enough to last for generations.

“We’re using up the last, best water, and we’re not making any new pure water,”

said Sarah J. Meyland, who teaches hydrology at the New York Institute of

Technology.

While the notion of an island lacking water may seem incongruous, the problem is

that the surrounding ocean keeps out most conventional sources of fresh water.

Unlike New York City, Long Island has no reservoirs, dams, great lakes or mighty

rivers to tap.

“A lot of people on Long Island have no idea where they get their water, but

everyone there drinks from the ground,” unless they use bottled water, said

Walter T. Hang, president of Toxics Targeting, a company that compiles data and

maps on contamination sites across the state.

On an average day, wells pump 450 million gallons of water to slake the island’s

thirst. Consumption often doubles or triples in the summer, when sprinklers are

working overtime to keep lawns green in America’s first modern swath of

suburbia. Residents use a daily average of 150 gallons per person, many

luxuriating with massaging shower heads, hot tubs, backyard pools and even water

parks.

The biggest local supplier — it claims to be the nation’s top provider of

underground water — is the Suffolk County Water Authority, serving 1.1 million

people.

That agency’s current campaign to dig a well at Northport into the Lloyd — which

is protected by a 1986 moratorium on drilling — has provoked opposition and

highlighted the fundamental issue of the island’s endangered water supply, which

is drawn from a network of 1,300 major wells and thousands of smaller private

ones.

The planned well is opposed by groups like the Sierra Club and the League of

Women Voters, as well as communities dozens of miles away in neighboring Nassau

County that rely on the aquifer. These opponents say the Suffolk authority has

other options, like removing contaminants from existing wells in Northport or

even piping in water, but the authority says the cost of those solutions would

present a “hardship.”

Ultimately, the commissioner of the State Department of Environmental

Conservation will decide whether to allow the digging.

To environmentalists, the issue is clear: the supply will be exhausted unless

changes are made. They warn that as contamination moves below the surface, water

suppliers have to remove more pollutants or drill farther to reach clean

sources. And they contend that pumping depletes that reserve, speeds the spread

of tainted pockets, sucks in saltwater along the coast and lowers the water

table.

“Across the island we are depleting our best water very rapidly,” said Ms.

Meyland, a leader in the coalition against the Northport well. “The solution is

not to simply drill deeper. That’s a losing proposition.”

Mr. Hang said: “There are thousands of known contamination sites on Long Island

and many more potential ones. The brew includes cesspool and sewage treatment

effluent, fuel tank leaks, fertilizers, pesticides, dry cleaning solvent, motor

oil, industrial waste, road runoff and leaching from garbage dumps. The latest

testing even finds traces of caffeine and Prozac.”

But other experts insist the island’s water is safe and ample.

Paddy South, a spokesman for the Suffolk water authority, said that rain

replenished far more than his agency pumped, leaving a reserve of up to 120

trillion gallons. “Basically,” he said, “we could last for 70 years using the

water we have now, even if it never rained again.”

In addition, the authority says it has the biggest laboratory in the nation for

testing groundwater, examining as many as 100,000 samples a year for about 300

compounds.

When contamination is detected, the water is filtered or blended with cleaner

water, or the well is closed. Defenders of the system say water quality is

improving with expanded sewage treatment, cleanup of toxic sites, filtering and

preserved open space like the Long Island Pine Barrens for collecting fresh

rain.

“Water quality on Long Island is among the best in the United States,” said Lee

E. Koppelman, director of the Center for Regional Policy Studies at Stony Brook

University.

Stephen M. Jones, the water authority’s chief executive, said, “Arguments are

being made on a political and emotional level that really don’t have anything to

do with the science.”

Environmentalists concerned about an end of the clean water supply do not

specify when this will happen.

“It will happen at different times in different places,” Ms. Meyland said, “and

in fact it has already happened in some places.”

On the western end of Long Island, the urbanization of Brooklyn and Queens left

the aquifers contaminated and depleted by the late 1940s, forcing the two

boroughs to turn to the Catskills and the Hudson River for water. Pollution and

saltwater have also closed wells in Nassau and Suffolk Counties, Ms. Meyland

said, noting that the number of wells in Nassau with detectible contamination

grew to 50 percent in 2000 from 15 percent in 1980.

In June, about 33,000 residents in the West Hempstead area were warned not to

drink the water because of contamination from a potentially carcinogenic

gasoline additive. The affected pumps were closed and service resumed, but Mr.

Hang, whose company compiles data on contamination sites, said, “West Hempstead

focused attention in a dramatic way.”

As intensive development has worked its way through Nassau and marched into

Suffolk, water pumping, contamination and salt intrusion have followed. The

Lloyd aquifer supplies only 9 percent of the island’s water, with bigger

reserves in higher layers in the east, far from the population centers.

Much of the stream for which Valley Stream was named has disappeared because

sewering — which stops contamination from septic tanks — has gradually lowered

the water table on the South Shore of Nassau.

Nowhere is the situation more sharply drawn than in Great Neck and Port

Washington on Nassau’s North Shore, where closing some wells forced communities

to pump water in from neighboring areas.

“It’s very analogous to the whole island, a predictive model,” said Assemblyman

Steven C. Englebright, a Democrat from Suffolk and the only geologist in the

State Legislature.

But experts all agree that Long Island has nowhere else to turn for water.

Hooking into the city system is not an option; a pipeline to the Hudson would be

prohibitively expensive; and the cost of distillation plants would be far

higher.

Of course, conservation would reduce demand. “We could do a heck of a lot more,”

Dr. Koppelman said

Some traditional uses of water are irrational, experts concede. They point to

toilets, which flush away 28 percent of household water, as the prime culprit,

using potable water to transport sewage.

Higher prices would discourage waste but would be politically unpopular. The

Suffolk water authority boasts about its bargain rates, about a penny for seven

gallons, or $280 annually for a typical homeowner, on the low end of the water

prices on Long Island.

In the 1970s, Long Island was among the nation’s first places designated by the

federal Environmental Protection Agency as depending on a “sole source aquifer”

requiring special protection. Yet responsibility for the water is fragmented

among various federal, state and local agencies, and more than 50 water

companies.

Still, Henry J. Bokuniewicz, director of Stony Brook’s Groundwater Research

Institute, said that “by and large, it operates in the right manner.”

Not surprisingly, some disagree. Assemblyman Englebright called the state’s

oversight a failure and denounced the Suffolk water authority as reckless.

Ms. Meyland said that the wells in Nassau have violated state pumping limits for

years with impunity, and proposed a new agency modeled on multistate river basin

commissions to monitor and allocate the water.

As a geologist concerned about the Lloyd, Assemblyman Englebright supports that

notion. “This is an extraordinary natural gift,” he said. “It comes pure from

the ground. You don’t have to filter or chlorinate it. It’s priceless. It’s ours

to use wisely or to squander.”

As

Aquifer Runs Dry, L.I. Water Debate Ensues, NYT, 2.12.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/02/nyregion/02water.html

Vegas reaching for rural water

Posted 10/18/2006 11:11 PM ET

USA Today

By John Ritter

BAKER, Nev. — Rancher Dean Baker picks his way

through greasewood and sedge to a shallow dirt depression that was once a small

pond fed by a natural spring. Both have been dry for years, casualties, he says,

of pumping that draws underground water to the surface to irrigate fields and

water livestock.

Over a half-century, agriculture's needs have

lowered the water table, Baker says, but it's nothing compared to what may be in

store for this arid, sparsely populated, mile-high desert near the Utah border.

The Southern Nevada Water Authority wants to pump vast quantities of groundwater

from rural eastern Nevada valleys and pipe it 250 miles south to Las Vegas, the

nation's fastest-growing major metro area, a tourist mecca with a limited water

supply strained by population and prolonged drought.

After hearings last month, a decision rests with State Engineer Tracy Taylor.

More hearings on plans in other valleys are pending. The water authority aims to

build a pipeline by 2015 and pump nearly 30 million gallons a year from 19 wells

in Spring Valley alone.

At stake, ranchers say, are livelihoods and a delicate ecological balance on a

landscape cursed with at most 8 inches of rain and snow a year.

"If they pull the water table down enough, this will be a dust bowl," says

Baker, 66, whose family has raised cattle in Spring Valley since the 1950s. "It

will completely change the economics of agriculture. It will also change the

life of the 40 head of antelope that stay in that alfalfa field."

Those concerns are unfounded, water authority officials say. Nevada law

prohibits impinging on existing water rights, says general manager Pat Mulroy.

"It's emotion," she says. "It's regionalism. It's rural vs. urban. It's

fear-based. Protecting that environment will always be of tantamount importance

to us.

Scarce resource

Since early settlers, water has been the West's scarcest and most valuable

resource. Towns pumped water, just as ranchers did. Rivers, lakes and streams

have been dammed, drained and diverted for decades and now offer little extra

supply for expanding urban centers such as Salt Lake City, El Paso, Albuquerque,

Phoenix and Tucson.

Now groundwater is the target, even if, as in Las Vegas' case, it'll cost $3

billion or more to get it and benefit one region at the expense of another.

"This is symptomatic of issues going on all over, particularly the Southwest,"

says Jeff Mount, director of the Center for Watershed Sciences at the University

of California, Davis. "When you look at it on a bigger, multigenerational scale,

we're basically mining these groundwater basins at rates that can't be

sustained. When the water's gone, it's gone."

Farms and ranches consume 80% of Western water supplies yet generate less than

1% of states' gross domestic product, says Hal Rothman, a history professor at

the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

"The real question isn't whether water will be transferred from rural to urban

use," he says. "The debate is over the terms of the transfer, how rural

communities that cede water will derive fair and valuable benefits from it."

Opponents of the water authority plan say it's one more instance of water

flowing uphill toward money, like Los Angeles' notorious "water grab" from the

Owens Valley in the early 1900s. That diversion — basis of the 1974 movie

Chinatown— allowed L.A. to grow but dried up a productive farm region.

"The parallels are stark," says Greg James, former director of the Inyo County,

Calif., water department in the Owens Valley. "They're looking to build a

pipeline, pump groundwater, and they're already acquiring ranchland."

State water laws and federal environmental regulations wouldn't permit a repeat

of Owens Valley, but ranchers want a guarantee that if the land suffers, the

pumps would be shut down. Otherwise, "by the time we see the effects of pumping,

it will be too late," says Gary Perea, a Democratic commissioner in White Pine

County.

The Mormon Church, based in Salt Lake City, owns water rights in Spring Valley

and has asked the engineer to withhold approval until a U.S. Geological Survey

study is finished next year.

The authority built a computer model to predict effects on the water table but

didn't run it. When it was run by a National Park Service hydrologist, it showed

a 150-foot drop over 75 years. Mulroy calls those results "hypothetical." John

Bredehoeft, a hydrogeologist who testified for opponents, says "it would have

been detrimental" to the authority's case.

Time is short, Mulroy says. The Las Vegas metro area — population 1.7 million,

20,000 new homes a year — relies on a share of Colorado River water stored in

Lake Mead for 90% of its supply. Seven years of drought have lowered the lake to

half its capacity. A year like 2002, when the river ran about a quarter of

normal, "would invoke a crisis," Mulroy says.

Reducing demand

The water authority is spending millions of dollars to entice homeowners to

replace irrigated lawns with drought-tolerant plants — 70% of water consumption

goes outdoors. A system captures, treats and returns water from indoor plumbing

to Lake Mead.

Opponents say tougher conservation measures, including raising water rates as

cities such as Tucson have done, could save as much as the authority plans to

take from Spring Valley.

"That penalizes people who can't afford it," Mulroy says.

Ranchers may think Las Vegas should slow its growth, but that's a political

non-starter in go-go southern Nevada. At the area's current growth rate, rural

groundwater is a stopgap measure at best, says Matt Kenna, a lawyer with the

Western Environmental Law Center representing opponents.

Many people believe that if the engineer rejects a water transfer or awards an

amount too small to make the pipeline economical, the authority will ask

Congress for a bigger share from the Colorado River.

When the river's flow was divided among seven states in 1922, Las Vegas was

little more than a crossroads. Nearly a century later, 400 farmers in

California's Imperial Valley still get 10 times more Colorado River water than

Las Vegas does.

Vegas

reaching for rural water, UT, 18.10.2006,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2006-10-18-vegas_x.htm

After a Seven-Year Ban, Salmon Fishing

Returns to Maine

September 28, 2006

The New York Times

By PAM BELLUCK

EDDINGTON, Me. — Forget your trout, your

striped bass. Wild Atlantic salmon are a fisherman’s Holy Grail.

They are fickle, finicky and feisty, and, in recent years in this country, few

and far between.

So scarce that in 1999, Maine, the last American bastion of wild Atlantic

salmon, closed its rivers to salmon fishing to save the salmon, whose numbers

had shrunk from pollution, dams and other forces. But it dealt a blow to

fishermen around the country, especially those who recall the heyday, when the

first silvery salmon caught in Maine each year went to none other than the

president of the United States.

Now, with salmon slowly returning, Maine has opened its first wild salmon season

in seven years — a month of restricted fishing on the state’s storied Penobscot

River.

It is drawing people from as far as Washington State and South Carolina, in

hip-waders and in boats.

[But it took until Wednesday, nearly two weeks after opening day, for the first

salmon to be caught.

[It was landed by Beau Peavey, a 22-year-old junior in college (“I took two

years off to fish,” he said), who is such a devotee he has been on the river

before sunrise every morning and again every evening since the season’s first

day. The salmon — a frisky 32-inch 12-pounder that fought back with “four jumps

and a couple of good long runs” — was caught after Mr. Peavey abandoned his own

flies and used a pink fly created years ago by a now-deceased member of his

salmon club.

[“From the time I was 9, I spent every waking minute up there fishing,” he said.

“The river closed when I was 15, and I caught one of the last legal fish in

1999. I fish religiously — that’s my life.” Mr. Peavey is a spring chicken in

the salmon game here.]

Before dawn on opening day, Bill Claus, 79, waded into the shimmering river,

having thought he would not live long enough to fish for salmon here again. Also

there was Ivan Mallett, 87, who caught a “presidential fish” 25 years ago and

hand-carried it to the White House and into the arms of Vice President George H.

W. Bush (who was on salmon duty because President Ronald Reagan had been shot

and was in the hospital.)

Although most fishermen have been outfoxed by the fish so far, few seem to mind.

“A salmon is called a fish of a thousand casts,” said Dick Ruhlin, president of

the Eddington Salmon Club. “For most people, to catch one is the catch of a

lifetime.”

The Eddington club and others were once so overflowing with anglers that a club

member had to die for someone to get off the waiting list. Since the salmon ban,

membership has dwindled, clubs have mostly been fishing for cribbage cards, and

“we’re begging for people to come in,” said Bob Wengrzynek, president of the

Maine Council of the Atlantic Salmon Federation.

“A lot of the clubs have people who don’t fish anymore because they can’t, but

20 years ago they caught a salmon,” Mr. Wengrzynek said. “It’s not about

fishing, it’s about the social structure. A lot of people will fish vicariously.

When there’s one person fishing, there’s 20 people watching, and, by extension,

that’s 21 people fishing.”

So it was not surprising that Charlie Colburn, 84, showed up, even though

arthritis keeps him from casting a line. “Holy mackerel,” he said, cane-hobbling

along the riverbank. “I think it’s just great. So these people do get a chance

to fish for that fish, to have the honor of hooking one of those fish, the king

of all fish. There’s no fish that can touch her.”

But the king of all fish has proven vulnerable to manmade meddling. Pollution

from paper mills, blasting by logging companies, and dams that impede salmon

migration helped slice the Penobscot salmon population to 530 in 2000, from

nearly 5,000 20 years ago, said Patrick Keliher, executive director of the Maine

Atlantic Salmon Commission.

Other efforts to restore salmon included restocking fish and tracking them with

transponders. An environmental coalition is raising $25 million to buy three

dams from a power company, tear down two of them and build a fish bypass around

the third.

But while the dam project is expected to restore thousands of salmon, it will

take years. And with just over 1,000 salmon currently in the Penobscot, Maine’s

largest river, Mr. Keliher said, state biologists felt they could allow limited

fishing, with the hope of ultimately resurrecting a sport that once drew

millions of tourism dollars into Maine’s economy.

“This is a big balancing act for us,” Mr. Keliher said. “Can we continue to have

positive restoration efforts at the same time we’re conducting recreational

angling? We’re going to eat the elephant one bite at a time.”

Maine is starting with baby steps: fall fishing, when salmon are smaller;

catch-and-release only; no barbs on fishhooks; and no fishing when the water

temperature hits 70 degrees because hooked fish recover better in cooler water.

Mr. Keliher said each salmon reaching the Veazie Dam, where they are temporarily

trapped, will be checked to see if it was hooked and what condition it is in. If

the fish seem to withstand the fall season, Maine may allow the more-popular

spring fishing.

The restrictions satisfied most environmentalists, said Andrew Goode, board

president of the Penobscot River Restoration Project, the coalition buying the

dams.

“We’re about restoring the fish, but we’re also trying to get the communities to

turn their attention to the river,” said Mr. Goode, who is also vice president

for American programs at the Atlantic Salmon Federation, a conservation group.

“We’re trying to raise so much money for this project. It’s nice for politicians

to see public interest in the river.”

More than 200 fishing licenses have been sold. At the Eddington salmon pool,

where a path to the water was freshly graveled to ease the strains on arthritic

knees and replacement hips, many anglers arrived in predawn blackness.

Some sailed small boats called peapods, while those on the shore followed the

age-old salmon-fishing formula: placing their poles in a wooden rack, waiting

their turn on a tarp-shrouded bench and performing a kind of angler’s ballet,

one after another.

“Take a cast, take a step and work your way up river,” said Mr. Ruhlin, 70, of

the salmon club. “We’re here because we love the sport, we love the river, and

we’re taking turns.”

There was sedate enthusiasm when David Horn, 65, a salmon veteran who has

snagged them as far away as Russia, hooked one from his drift boat but lost it

after 15 seconds. Mr. Claus saw one roll out of the water, but nowhere near his

hot orange harr wing wet fly.

Mr. Mallett watched at first, his wife, Gloria, explaining that nowadays “he

does most of his fishing from the couch.”

And Joel Bader, 45, who heads the bass-fishing club in Bangor, was hoping the

salmon would start biting, planning to yank his 10-year-old son out of school if

they did.

“I was last here when fishing ended, and I’m here today,” Mr. Bader said. “It’s

amazing, really part of history. It’s what every fisherman strives to achieve —

catching Atlantic salmon. It’s what I want to achieve, especially on the

Penobscot River.”

After

a Seven-Year Ban, Salmon Fishing Returns to Maine, NYT, 28.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/28/us/28salmon.html?hp&ex=1159502400&en=1c8ef4c54ce70263&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Accord Reached on Diverting Water From

Farms to Restore San Joaquin River

September 14, 2006

The New York Times

By JESSE McKINLEY

SAN FRANCISCO, Sept. 13 — For most of the last

60 years, much of the San Joaquin River has not really been a river. Dammed and

drained for agricultural purposes in the arid Central Valley, the San Joaquin is

dry for mile after mile, a symbol of the cost of progress and the miracles of

modern irrigation.

It has also been the subject of extensive litigation.

On Wednesday, a coalition of environmental and fishing groups announced the

settlement of an 18-year-old suit against the Interior Department and a group of

California water users, ending one of the longest-running environmental

skirmishes.

The proposal, which Congress will vote on, would create a multimillion-dollar

project to restore more than 150 miles of the San Joaquin to the lush riverbed

it once was.

“This is one of the most important and historic restoration efforts in the

West,” said Hal Candee, a senior lawyer for the Natural Resources Defense

Council, which filed the suit in the Reagan administration. “This is really

bringing a dead river back to life.”

Under the plan, announced in Sacramento, billions of gallons of water would

eventually be released from Friant Dam, just north of Fresno, spilling into the

historic river channels. The new flow, environmentalists and fishermen hope,

will create a healthy environment for Chinook salmon, which once spawned — and

thrived — in the San Joaquin.

In exchange for losing 15 percent to 20 percent of their yearly water, depending

on rainfall, farmers and other long-term water users would be assured of a

supply.

“For the next 20 years, we know what the water commitment is going to be, and

that was important to us,” said Ron Jacobsma, consulting general manager of the

Friant Water Users Authority, which represents 22 water districts that span five

counties.

Fed by downstream tributaries, the San Joaquin, the second-longest river in

California, flows as it meets the Sacramento River east of San Francisco,

forming an enormous delta that provides water to 22 million Californians. Since

the 1940’s, the upper reaches of the river, from Friant Dam to its convergence

with the Merced River, have been siphoned off to water a million acres of crops

through a vast irrigation project that has helped turn the Central Valley into

one of the most prosperous agricultural regions.

The proposed restoration would carry a hefty price, with estimates from $250

million to $800 million, a cost that the federal government and state would

probably share.

Some support seems to have been mustered. Mike Chrisman, secretary for state

resources, signed off on the accord on Wednesday, as did Senator Dianne

Feinstein, a Democrat, and Representative George P. Radanovich, a Republican.

Mr. Radanovich, who represents the Fresno region, said he would hold a hearing

on the plan on Sept. 21.

After years of machinations and stalled negotiations, legal pressure on the

government intensified in 2004, when a federal district judge in Sacramento,

Lawrence K. Karlton, ruled in the environmentalists’ favor, saying the

California Fish and Game Code, which guarantees water to fisheries, could be

applied to the federally owned Friant Dam.

Judge Karlton had set a trial date for earlier this year to consider remedies.

But as that date approached, the two sides returned to the table to find a more

nuanced middle ground.

“The judge had made statements along the lines of all he had was a meat

cleaver,” Mr. Jacobsma of the water users’ authority said. “And what we needed

was a scalpel.”

Kirk Rodgers, a regional director for the Federal Bureau of Reclamation, said

the project would “probably be unprecedented in terms of its magnitude and

challenges.”

“In some cases,’’ Mr. Rodgers said, “you’re going to have to define a channel

through mechanical means. In some cases, you’re going to have to build

structures to put the water that’s being diverted back in the channel. It’s a

very complicated and very ambitious project.” Some water spilled into the

riverbed would also be recirculated to farmers, he said.

A tentative timetable calls for water to be diverted to the river by 2009 or

2010. Fish would be introduced two or three years later, with most construction

and physical restoration finished by 2016. The project, if approved, would run

through 2026.

Accord Reached on Diverting Water From Farms to Restore San Joaquin River, NYT,

14.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/14/us/14river.html

In the West, a Water Fight Over Quality,

Not Quantity

September 10, 2006

The New York Times

By JIM ROBBINS

MILES CITY, Mont. — It is a strange fight,

Montana ranchers say. Raising cattle here in the parched American outback of

eastern Montana and Wyoming has always been a battle to find enough water.

Now there is more than enough water, but the wrong kind, they say, and they are

fighting to keep it out of the river.

Mark Fix is a family rancher whose cattle operation depends on water from the

Tongue River. Mr. Fix diverts about 2,000 gallons per minute of clear water in

the summer to transform a dry river bottom into several emerald green fields of

alfalfa, an oasis on dry rangeland. Three crops of hay each year enable him to

cut it, bale it and feed it to his cattle during the long winter.

“Water means a guaranteed hay crop,” Mr. Fix said.

But the search for a type of natural gas called coal bed methane has come to

this part of the world in a big way. The gas is found in subterranean coal, and

companies are pumping water out of the coal and stripping the gas mixed with it.

Once the gas is out, the huge volumes of water become waste in a region that

gets less than 12 inches of rain a year.

In some cases, the water has benefited ranchers, who use it to water their

livestock. But there is far more than cows can drink, and it needs to be dumped.

The companies have been pumping the wastewater into drainages that flow into the

Tongue River, as well as two other small rivers that flow north into Montana,

the Powder and Little Powder Rivers. Ranchers say the water contains high levels

of sodium and if it is spread on a field, it can destroy the ability to grow

anything.

“It makes the soil impervious,” said Gov. Brian Schweitzer, who is a soil

scientist. “It changes it from a living, breathing thing into concrete.”

Ranchers like Mr. Fix say sodium in the water could render their hayfields

unusable and drive them out of business.

The companies say that sodium is not the problem ranchers have made it out to be

and that the Montana environmental standards cannot be met without great

difficulty. They have filed suit in federal and Montana court to overturn the

regulations.

The fight pits Montana against Wyoming. Wyoming has thrown the door open to coal

bed methane producers, with 20,000 wells in the basin. Wyoming says its water

quality standards, while different from those in Montana, are more reasonable

and still protect water quality.

“Montana doesn’t need to be concerned,” said John Wagner, administrator of the

Wyoming Water Quality Division. “We have real tough limits put on these

discharges.”

The energy companies agree with Wyoming.

“There has been no documented impact to these drainages,” said David Searle,

manager of governmental affairs for Marathon Oil, one of the companies that has

methane wells in the region and is a party to the lawsuit. Montana’s regulations

“are an overreaction and they are unnecessary,” Mr. Searle said. In some cases,

he said, the standards are lower than background, or natural levels.

But Jill Morrison, a community organizer for the Powder River Basin Resource

Council, a coalition of ranchers and environmentalists that has battled coal bed

methane in Wyoming and has entered the lawsuit on Montana’s side, said ranchers

should be worried.

“Wyoming wants to think it is doing a good job, but that’s laughable,” Ms.

Morrison said. “You can see the changes in the vegetation and the salt deposits

in the soil,” when ranchers try to use wastewater.

She also said that the huge volume of water alone could be a problem. Some

riparian areas have adapted to natural ephemeral flows. But coal bed methane

discharges flood the normally dry streambeds year round, and have eliminated

native grasses. Too much water, she said, has killed 100-year-old cottonwood and

box elder trees.

The problem has led to tension between two Democratic governors who are usually

on friendlier terms. Last spring Gov. Dave Freudenthal of Wyoming asked the

federal environmental protection administrator to appoint a mediator to settle

the dispute. Governor Schweitzer chastised him, saying “nobody likes a

tattletale to the teacher.”

But producers in Wyoming are clearly worried new wells will stymie a growth

industry.

“It will have an impact on some projects, there’s no doubt,” Mr. Searle said.

Governor Freudenthal said the impact on development in his state could be

serious.

The problem, Governor Schweitzer said, is aggravated by Wyoming’s refusal to

release water into Montana to water rights holders that are senior to some in

Wyoming, because that state interprets a 1950 water compact differently.

Governor Schweitzer vowed to defend vigorously the state’s right to set

environmental standards. Coal bed methane water needs to be treated before it is

released, or reinjected into the ground in Wyoming, he said, something producers

say is too expensive. He is not persuaded.

“The country needs coal bed methane,” he said. “But they can’t come in and

destroy an industry, the cattle industry, that’s been in the family for 100

years. These people aren’t getting rich, they’re just making a living.”

In

the West, a Water Fight Over Quality, Not Quantity, NYT, 10.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/10/us/10river.html

NYT

August 28, 2006

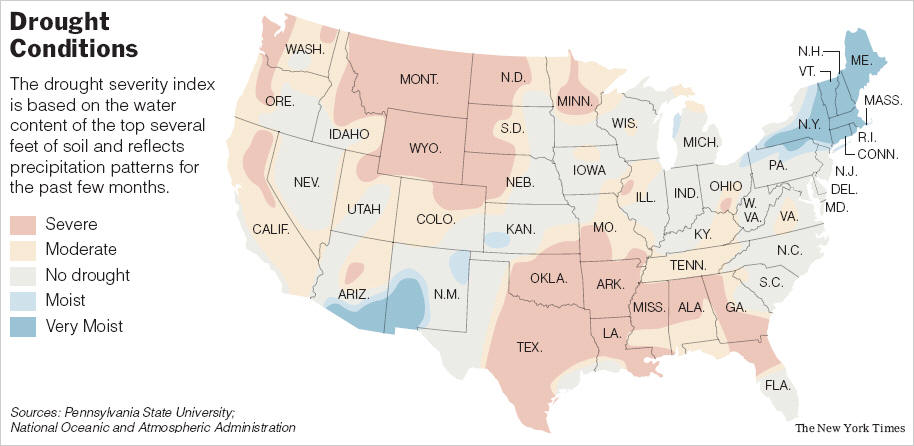

Blistering Drought Ravages Farmland on Plains

NYT

29.8.2006

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/08/29/us/29drought.html

Blistering Drought

Ravages Farmland on Plains

August 29, 2006

The New York Times

By MONICA DAVEY

MITCHELL, S.D. — With parts of South Dakota at

its epicenter, a severe drought has slowly sizzled a large swath of the Plains

States, leaving farmers and ranchers with conditions that they compare to those

of the Dust Bowl of the 1930’s.

The drought has led to rare and desperate measures. Shrunken sunflower plants,

normally valuable for seeds and oil, are being used as a makeshift feed for

livestock. Despite soaring fuel costs, some cattle owners are hauling herds

hundreds of miles to healthier feedlots. And many ranchers are pouring water

into “dugouts” — natural watering holes — because so many of them (up to 90

percent in South Dakota, by one reliable estimate) have gone dry.

Gov. Michael Rounds of South Dakota, who has requested that 51 of the state’s 66

counties be designated a federal agricultural disaster area, recently sought

unusual help from his constituents: he issued a proclamation declaring a week to

pray for rain.

“It’s a grim situation,” said Herman Schumacher, the owner of a livestock market

in Herreid, S.D., a small town near the North Dakota line where 37,000 head of

cattle were sold from May through July, compared with 7,000 in the corresponding

three months last year. “There’s absolutely no grass in the pastures, and the

water holes are all dried up. So a lot of people have no choice but to sell off

their herds and get out of the business.”

Drought experts say parts of the states most severely affected — Nebraska, the

Dakotas, Montana and Wyoming — have been left in far worse shape because of

recent history: several years of dry conditions, a winter with little snow and

then, with moisture reserves in the soil long gone, a wave of record heat this

summer.

By late August, rain had fallen several times in some areas, but Bob Hall, an

extension crops specialist at South Dakota State University, said it amounted to

“a drip in a bucket.”

“The bottom line is that even if we got relief starting today, at this minute,”

Dr. Hall said, “it would take a few years economically to recover.”

As if earless, shriveled cornstalks were not enough, farmers and ranchers say

they carry a sense that their counterparts elsewhere seem to be doing just fine,

leaving them with what feels like an invisible disaster, unnoticed by the

outside world. Some farmers in Midwestern states like Illinois, Indiana and

Ohio, as well as some in the eastern sections of South Dakota and Nebraska, tell

of a respectable growing season.

Even here in Mitchell, about 70 miles west of Sioux Falls, some residents did

not grasp the scope of the drought until the Corn Palace, this city’s

tourist-luring castlelike civic center wrapped in hundreds of thousands of ears

of corn, announced that because there was not enough of the crop, it would not

redecorate this year for the 2007 season.

“We don’t have any record of anything like this happening before,” said Mark

Schilling, the director of the Corn Palace, a campy, 114-year-old landmark

promoted on highway billboards with endless corn puns.

“But if there’s not a crop, there’s not a crop,” Mr. Schilling said quietly.

After weeks and weeks with little rain and high temperatures, one farmer, Terry

Goehring, watched the mercury spike to 118 degrees in his Mound City, S.D.,

field one day in July. That was it. Mr. Goehring, who has farmed since 1978,

sold half his 250 head of Angus cattle.

“There was no corn,” he said. “There was no hay. We had nothing. And in that

moment, I knew there was no choice.”

Climatologists with the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of

Nebraska-Lincoln said scientists deemed the weather conditions and its effects

in the areas of the worst drought a once-in-50-years experience.

In some cases, it has been worse than that. On July 15, a weather station in

Perkins County, S.D., near North Dakota, recorded a temperature of 120 degrees.

That matched the highest ever reported in the state since the start of such

record-keeping in July 1936, said Brian Fuchs, a climatologist at the Nebraska

center.

Given such conditions, it is hardly a surprise that crop estimates are so

gloomy. Steve Noyes, deputy director at the South Dakota field office of the

government’s National Agricultural Statistics Service, said the winter wheat

crop here had shrunk by 43 percent from last year’s; alfalfa hay is expected to

be down by 35 percent; and 22 percent of pasture land is deemed “very short,”

with 35 percent “short,” figures significantly worse than those of a year ago.

For the most part, commodity prices have not been affected, said Greg Lardy, a

beef cattle specialist at North Dakota State University. While the region

affected is hard hit, Dr. Lardy said, it has not been large enough to leave a

mark on prices, particularly since some other regions have experienced strong

seasons.

A walk through the fields of David Gillen, whose family has farmed in White

Lake, 35 miles west of Mitchell, since 1897, is a tour of a drought. While some

fields have survived, others are not worth harvesting. There, corn that should

have been lanky by now is short and yellow, and many stalks carry no ears: the

pollination, which should have occurred at the end July, never happened at all,

given the extreme heat.

“This is my favorite time to be out here looking at the fields,” Mr. Gillen

said. “But there’s nothing to see.”

While the soybean fields may improve with the recent rains, it is too late for

this year’s corn, a circumstance that surely would have made the creators of the

Corn Palace cringe.

In 1892, the Corn Belt Real Estate Association decided it made sense to nail

ears of corn to the side of the palace as a salute to the bounty that the

region’s soil could produce, and as a retort to those (including Lewis and

Clark) who seemed to doubt that these seemingly wild lands could be farmed.

So for years (and through three different palaces in Mitchell), annual themes

(like the “Space Age” in 1969 and a “Salute to Rodeo” this year) have been

captured in images made all of corn here, at a cost, in today’s prices, of about

$140,000 a year. But as this summer proceeded and the sun blazed on, the palace

board nervously monitored the fields whose dramatically colored corn goes to the

palace, waited for rain and consulted with an agronomist.

With fields of certain colors struggling, the board decided the murals it had

planned for the 2007 theme, “Everyday Heroes,” could not be created, said Mr.

Schilling, the palace’s director. Wade Strand, the farmer who grows all of the

palace’s colored corn, took the news “pretty hard,” Mr. Schilling said.

Looking back, Mr. Strand said he had believed that he had grown enough corn. He

said he had hoped the designs could be made without orange tone and shades of

black and light red. “But they felt that the colors I was missing were strategic

to the theme,” Mr. Strand said.

Mr. Schilling said he believed that the current murals would remain intact

through a second year, though he acknowledged that they might fade a bit. The

vulnerabilities now, he said, are the risks inherent in art, or anything, made

of corn: the effects of birds and wind, sun and heat.

Blistering Drought Ravages Farmland on Plains, NYT, 29.8.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/08/29/us/29drought.html?hp&ex=1156910400&en=a4f95604e6dbe65a&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Tunnelers Hit Something Big: A Milestone

August 10, 2006

The New York Times

By SEWELL CHAN

It is the biggest public works project in New

York City’s history: a $6 billion water tunnel that has claimed 24 lives,

endured under six mayors and survived three city fiscal crises, along with the

falling and rising fortunes of the metropolis above it.

Yesterday, the city’s Water Tunnel No. 3 reached a major milestone, as workers

completed the excavation of an 8.5-mile section that connects Midtown and Lower

Manhattan to an earlier section under Central Park. The tunnel is a multi-decade

effort spanning four stages; yesterday’s announcement signifies the end of

excavation for the second of those stages.

It was a major step forward for the tunnel, which was authorized in 1954, begun

in 1970 and then halted several times for lack of money. The completion of the

second stage will nearly double the capacity of the city’s water supply,

currently 1.2 billion gallons a day, and provide a backup to two other aging

water tunnels, allowing them to be closed, inspected and repaired for the first

time since they opened, in 1917 and 1936.

“Future generations of New Yorkers will have the clean and reliable supply of

drinking water essential for our growing city,” Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg said,

before he descended 550 feet into the city’s lower bedrock and sat at the

controls of a 70-foot-long tunnel-boring machine, as it excavated the last eight

inches of quartz, granite and silica.

Since 2003, the giant excavating machine’s 27 rotating steel cutters, each

weighing 350 pounds, have chipped through the bedrock at a rate of 55 to 100

feet a day, more than double the 25 to 40 feet that could be excavated each day

under the old drill-and-blast method.

The Third Water Tunnel originates at the Hillview Reservoir in Yonkers, just

across the border between the Bronx and Westchester County. The reservoir is fed

by aqueducts that carry water from the Catskill and Delaware water systems,

which usually provide 90 percent of the city’s water supply.

From the reservoir, the first stage of the tunnel reached south into the center

of the Bronx, then west across the Harlem River into Upper Manhattan and then

down the west side of Manhattan and east into Central Park, crossing under the

East River and into Astoria, Queens. That 13-mile first stage cost about $1

billion. It was begun in 1970, completed in 1993 and opened in 1998.

The second stage, which extends the first stage south into Midtown and Lower

Manhattan and east and south into Queens and Brooklyn, is complicated.

The Brooklyn-Queens section — actually two separate tunnels, linking Red Hook,

Brooklyn, via Maspeth, Queens, to Astoria — was completed by 1999 and will open

by 2009.

The new 8.5-mile Manhattan section, begun in October 2003, resembles three

spokes radiating from a central point roughly below the intersection of West

30th Street and 11th Avenue. One spoke traveled north to Central Park, the

second went to Lower Manhattan, and the third spoke, 2.5 miles long, traveled

east to Second Avenue and then north to East 59th Street and First Avenue. That

third section was the last to be fully excavated, a step completed yesterday.

The new section must be lined with concrete, tested, fitted with instruments and

sterilized before water can gush through it in 2012. The city is also installing

at least 10 shafts that will link the tunnel with the water-distribution grid.

Even after 2012, two more stages of the project will remain. Stage 3, a 16-mile

segment called the Kensico-City Tunnel, will join the Kensico Reservoir in

Westchester County with the Van Cortlandt valve chamber in the Bronx. It is in

the final planning stages. A proposed Stage 4, extending south from the Hillview

Reservoir, through the Bronx and under the East River into Queens, is still

under review.

Although Mr. Bloomberg usually avoids direct comparisons with his predecessors,

he boasted yesterday about his commitment to the Third Water Tunnel.

“Part of the reason that work on it has stretched through six administrations is

that the city’s funding for this project has sometimes dropped off during tough

financial times,” he said. “But not on our watch. Even in the first years of our

administration, when we faced record multibillion-dollar, back-to-back budget

shortfalls, we refused to shortchange this essential project.”

He said his administration had committed nearly $4 billion to the project, or

“doubled what’s been invested by the last five administrations combined.”

Around 10:40 a.m., after a news conference at the main construction site in

western Midtown, Mr. Bloomberg went down a shaft in a narrow cage-like elevator

that fits up to 26 people. He was joined by Emily Lloyd, commissioner of the

city’s Department of Environmental Protection; a coterie of aides and police

officers; and officials from the contractor in charge of the Manhattan section,

a joint venture of the Schiavone Construction Company, J. F. Shea Construction

and Frontier-Kemper Constructors.

At the base of the elevator was an enormous tunnel — dark, cool and humid — with

wet ground coated in a murky gray mixture of mud and sand. The group boarded a

narrow railcar for the journey east and north through the tunnel.

After a smooth ride of 15 minutes, the officials left and walked alongside much

of the 700 feet of equipment that trails the tunnel-boring machine. About 200

feet from the front of the machine, they entered an operating cab, where Mr.

Bloomberg and Ms. Lloyd sat. Vinny Crimeni, the main operator, showed them the

guidance system that keeps the machine on course and keeps the tunnel straight

and smooth.

“I pushed a bunch of buttons, but the real professional was sitting next to me,”

the mayor said afterward.

Around 11:20 a.m., Mr. Bloomberg and Ms. Lloyd left the cab. Using big black

felt-tip markers, they signed their names on the tunnel wall, then posed for

pictures with the sandhogs, as the tunnel diggers are called.

One sandhog, Jim O’Donnell, a brakeman on the small train, said the event filled

him with pride. Many of the workers are of Irish or West Indian descent and many

are carrying on a family tradition of working underground.

“At least half the guys who work down here, I’ve worked with their fathers,”

said Mr. O’Donnell, 44, whose older brother, 47, also works on the tunnel.

Tunnelers Hit Something Big: A Milestone, NYT, 10.8.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/08/10/nyregion/10tunnel.html

More than 60% of U.S. in drought

Updated 7/29/2006 9:36 PM ET

AP

USA Today

STEELE, N.D. (AP) — More than 60% of the

United States now has abnormally dry or drought conditions, stretching from

Georgia to Arizona and across the north through the Dakotas, Minnesota, Montana

and Wisconsin, said Mark Svoboda, a climatologist for the National Drought

Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln.

An area stretching from south central North

Dakota to central South Dakota is the most drought-stricken region in the

nation, Svoboda said.

"It's the epicenter," he said. "It's just like a wasteland in north central

South Dakota."

Conditions aren't much better a little farther north. Paul Smokov and his wife,

Betty, raise several hundred cattle on their 1,750-acre ranch north of Steele, a

town of about 760 people.

Fields of wheat, durum and barley in the Dakotas this dry summer will never end

up as pasta, bread or beer. What is left of the stifled crops has been salvaged

to feed livestock struggling on pastures where hot winds blow clouds of dirt

from dried-out ponds.

Some ranchers have been forced to sell their entire herds, and others are either

moving their cattle to greener pastures or buying more already-costly feed.

Hundreds of acres of grasslands have been blackened by fires sparked by

lightning or farm equipment.

"These 100-degree days for weeks steady have been burning everything up," said

Steele Mayor Walter Johnson, who added that he'd prefer 2 feet of snow over this

weather.

Farm ponds and other small bodies of water have dried out from the heat, leaving

the residual alkali dust to be whipped up by the wind. The blowing,

dirt-and-salt mixture is a phenomenon that hasn't been seen in south central

North Dakota since the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, Johnson said.

North Dakota's all-time high temperature was set here in July 1936, at 121.

Smokov, now 81, remembers that time and believes conditions this summer probably

are worse.

"I could see this coming in May," Smokov said of the parched pastures and wilted

crops. "That's the time the good Lord gives us our general rains. But we never

got them this year."

Brad Rippey, a federal Agriculture Department meteorologist in Washington, said

this year's drought is continuing one that started in the late 1990s. "The 1999

to 2006 drought ranks only behind the 1930s and the 1950s. It's the third-worst

drought on record — period," Rippey said.

Svoboda was reluctant to say how bad the current drought might eventually be.

"We'll have to wait to see how it plays out — but it's definitely bad," he said.

"And the drought seems to not be going anywhere soon."

Herman Schumacher, who owns Herreid Livestock Auction in north central South

Dakota, said his company is handling more sales than ever because of the

drought.

In May, June and July last year, his company sold 3,800 cattle. During the same

months this year, more than 27,000 cattle have been sold, he said.

"I've been in the barn here for 25 years and I can't even compare this year to

any other year," Schumacher said.

He said about 50 ranchers have run cows through his auction this year.

"Some of them just trimmed off their herds, but about a third of them were

complete dispersions — they'll never be back," he said.

"This county is looking rough — these 100-degree days are just killing us," said

Gwen Payne, a North Dakota State University extension agent in Kidder County,

where Steele is located.

The Agriculture Department says North Dakota last year led the nation in

production of 15 different commodity classes, including spring wheat, durum

wheat, barley, oats, canola, pinto beans, dry edible peas, lentils, flaxseed,

sunflower and honey.

North Dakota State University professor and researcher Larry Leistritz said it's

too early to tell what effect this year's drought will have on commodity prices.

Flour prices already have gone up and may rise more because of the effect of

drought on wheat.

"There will be somewhat higher grain prices, no doubt about it," Leistritz said.

"With livestock, the short-term effect may mean depressed meat prices, with a

larger number of animals being sent to slaughter. But in the longer run it may

prolong the period of relatively high meat prices."

Eventually, more than farmers could suffer.

"Agriculture is not only the biggest industry in the state, it's just about the

only industry," Leistritz said. "Communities live or die with the fortunes of

agriculture."

Susie White, who runs the Lone Steer motel and restaurant in Steele, along

Interstate 94, said even out-of-state travelers notice the drought.

"Even I never paid attention to the crops around here. But I notice them now

because they're not there," she said.

"We're all wondering how we're going to stay alive this winter if the farmers

don't make any money this summer," she said.

More

than 60% of U.S. in drought, UT, 29.7.2006,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2006-07-29-us-drought_x.htm

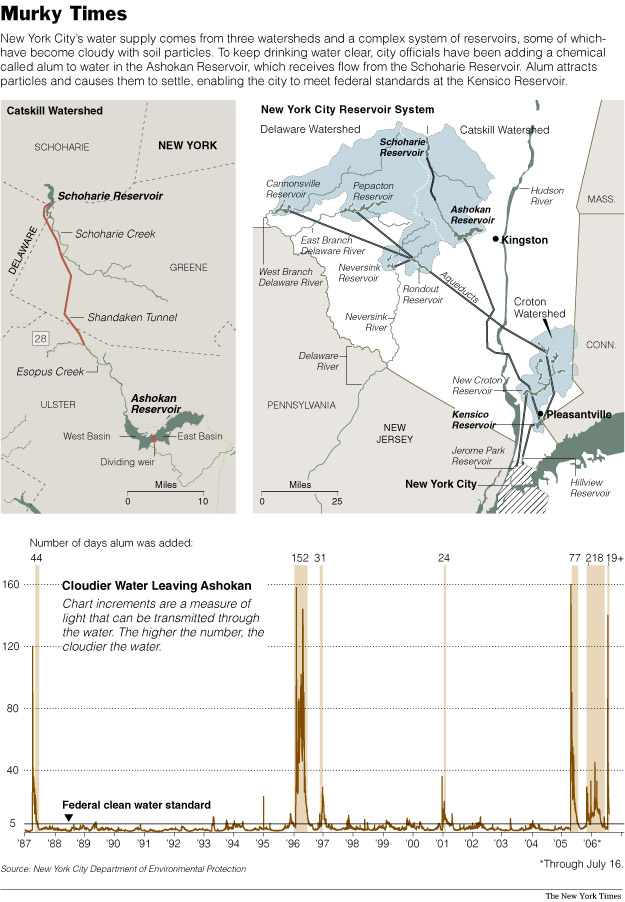

New York’s Water Supply May Need Filtering

NYT 20.7.2006

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/20/nyregion/20water.html

New York’s Water Supply

May Need Filtering

July 20, 2006

The New York Times

By ANTHONY DePALMA

New Yorkers are endowed with certain

inalienable rights, among them bragging about the city’s water — so pure it

doesn’t need to be filtered, so delicious it is better than bottled.

So it may surprise, perhaps even insult, proud residents to hear that federal

officials are worried that the fabled water — coming from the largest unfiltered

system in the country — is getting muddier and may have to be completely

filtered, at a cost of billions of dollars, if it cannot be kept clean.

For much of the last year, the century-old water system that delivers 1.3

billion gallons a day to the city has been clouded by particles of clay, washed

into upstate reservoirs by violent storms in quantities that make the water look

like chocolate Yoo-hoo.

To keep the tap water running clear, the city has been dumping 16 tons of

chemicals a day, on average, into the water supply as an emergency measure to

meet federal water quality standards. The treatment does not change the taste of

the water, but the city cannot rely on this stopgap approach forever.

Turbidity — the condition that makes water cloudy and interferes with

chlorination to eliminate contaminants — appears to be getting worse because of

changing weather patterns and increasing runoff from land development upstate.

If the city cannot find a permanent solution to the silt, it may not be able to

avoid building a huge filtration plant that could cost about $8 billion.

Because its water has historically been so pure, New York has largely been

exempt from federal rules created in the late 1980’s that require all water

systems to be filtered. (A small part of the system, in Westchester, will be

filtered in a few years.)

But as federal officials review the city’s five-year exemption, which expires at

the end of this year, they have openly expressed concern about the water

quality.

“The single most important item we’re looking at, and the one that could be a

problem for the city, is turbidity,” Walter Mugdan, a local director of the

Environmental Protection Agency, testified at a City Council hearing this

spring. His office, the Division of Environmental Protection and Planning, will

decide early next year whether the city’s water is clean and clear enough to

avoid filtration for another five years. (Only four other major cities — Boston,

San Francisco, Seattle and Portland, Ore. — are also exempt.)

The city is confident that it will win renewal. Emily Lloyd, commissioner of the

city’s Department of Environmental Protection, which runs the water system, said

that the department was working on plans to reduce turbidity without chemicals,

particularly in two big reservoirs in the Catskill Mountains.

Steven C. Schindler, director of the department’s division of drinking water

quality control, said, “I don’t consider turbidity a serious problem as long as

we are able to operate the system the way it was designed.”

The city’s early engineers designed a system that only on rare occasions would

have to rely on a chemical, aluminum sulfate, to reduce turbidity. Alum, as it

is called, is used in most public drinking water systems in the United States to

keep water clear because it draws together small particles, causing them to

clump up and settle before the water enters the distribution system.

But some people see the prolonged use of alum as a sign that turbidity has

become more severe. James M. Tierney, an assistant state attorney general who

has special responsibility over the city’s 2,000-square-mile upstate watershed,

has criticized the city for waiting too long to correct the problem.

In a letter to state environmental officials in April, Mr. Tierney said the

continued use of alum “would appear to indicate seriously deficient conditions

in the Catskill portion of the New York City Watershed.”

Mr. Tierney also said in the letter that the city’s alum use violated state

water quality standards and effectively turned one of its reservoirs, where the

alum clumps accumulate, into “a chemical sludge settling pond” that smothered

aquatic life and would at some point need to be dredged at considerable expense.

Ms. Lloyd said the city had used alum from time to time over the last century

without any impact on water quality. Mr. Tierney has called on the city to limit

alum use and to hasten its efforts to reduce murkiness in the upstate

reservoirs.

The city’s complex system — with 19 reservoirs bringing mountain water to New

York from as far as 125 miles away through a gravity-fed web of aqueducts — is

divided into three separate segments. In the 1990’s, the city agreed to filter

the water coming from the Croton segment, the oldest and smallest section, which

sits in Westchester and Putnam Counties, because it would be impossible to meet

clean-water standards there. A $1.2 billion filtration plant is under

construction in the Bronx.

The second oldest is the Catskill segment. In the early years of the 20th

century, the city — with the help of special state laws — condemned thousands of

acres in the eastern Catskills to build two reservoirs that more than doubled

the city’s capacity.

In the 1950’s and 1960’s, the city expanded again, tapping the east and west

branches of the Delaware River and other tributaries to create the newest and

largest of its three segments.

The turbidity problem stems largely from conditions that have been present in

the Catskill system from the beginning. Engineering studies in 1903 recognized

that the clay of the steeply sloped Eastern Catskills turned the sweet waters of

the Schoharie and Esopus Creeks into mudholes after storms.

Engineers decided to go ahead anyway, devising a two-reservoir system with

built-in turbidity controls. Water from the farthest of the 19 reservoirs, the

Schoharie, flows 18 miles through a tunnel under a mountain into the Esopus

Creek, which then winds its way into the west end of the gigantic Ashokan

Reservoir, 12 miles long and up to a mile wide.

The Ashokan is actually two reservoirs, separated by a dam, or weir. The turbid

water from the Schoharie enters the west basin and is kept there until, in

theory, the sediments drop. Then a gate in the dividing weir is lowered,

allowing the cleanest surface water to flow into the east basin, where it is

kept for several weeks longer to settle before making the long trip to New York

City.

The system worked well for decades, with alum being used only rarely. But over

the century, development in the Catskills, the building of roads, clearing of

land and paving over of ground, all increased soil erosion, contributing to more

runoff, federal officials said.

Water quality standards also got tougher; scientists have found that the clay

particles hampered purification by providing nutrients for microbial pathogens

and shielding them from decontaminants. Weather patterns over the last decade

have brought more frequent and heavier rain. And the city has been draining

murky water from the Schoharie Reservoir in order to repair its dam.

In 1998, water from the Schoharie Reservoir had become so muddy that

environmental and fishing groups sued the city, claiming the sediment violated

the Clean Water Act and impaired trout fishing along Esopus Creek, which is

famous for it. A federal court ruled against the city in 2003, and in June an

appeals court upheld the decision and the $5 million fine.

Federal officials raised concerns about turbidity in granting the filtration

avoidance permit in 2002.

Since then, the city has studied several engineering and operational options for

restoring the city’s water supply to its former glory.

Among the most likely fixes is the construction of a multilevel intake at the

Schoharie Reservoir. Like a huge straw with openings at different levels, the

new intake, which would cost more than $100 million according to city officials,

would allow operators to draw off the clearer surface water, while giving the

turbid waters at lower depths more time to clear. Right now, the Schoharie is

equipped with a single valve on the bottom of the reservoir, which acts like a

bathtub drain, allowing the lowest-quality water to exit first.

Other options include raising the weir at the Ashokan dam by five feet. This

would increase its capacity by five billion gallons, and give turbid water

flowing into the west basin more time to decant.

Another option is to build a baffle around the intake in the east basin to slow

down the water before it enters the aqueduct to New York. Ms. Lloyd said cost

estimates for these projects had not yet been prepared.

To avoid being forced to build a filtration plant for the Catskill and Delaware

systems — which supply up to 90 percent of the city’s water — New York will also

have to undertake other projects.

As part of its latest filtration avoidance permit, it agreed to build a new

plant in Westchester County that will use ultraviolet light to purify water.

The project, under construction in Mount Pleasant and Greenburgh, will be the

largest in the world when completed in 2010.

However, turbidity in the water would reduce its effectiveness because sediment

deflects ultraviolet rays.

The city will also have to continue protecting stream banks and controlling

development, and buy additional land in the watershed.

Over the last decade, the city has bought 70,000 acres at a cost of $168

million, and it expects to match that over the next decade. The property tax

bill for upstate land costs the city over $100 million a year.

Which raises the question of whether building a filtration plant is inevitable

in the long run, and if so, wouldn’t it make more sense to simply go ahead and

build it now?

City, state and federal officials don’t think so. Mr. Mugdan, the federal

official, calculates that the city has spent about $1 billion over the last

decade to protect the water supply, compared with $6 billion to $8 billion to

build a plant, along with hundreds of millions of dollars in operating costs.

“Even if, 75 years from now, some accountant asks how much has it cost the city

to avoid filtration versus how much we would have spent to build it,” Mr. Mugdan

said, “we’ll still be ahead.”

New

York’s Water Supply May Need Filtering, NYT, 20.7.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/20/nyregion/20water.html?hp&ex=1153454400&en=2be183debc88eae7&ei=5094&partner=homepage

The debate over replacing a part of the

All-American Canal with a concrete-lined trough

has strained the longstanding ties between Calexico, Calif., and Mexicali,

Mexico, top.

Sandy Huffaker for The New York Times

Border Fight Focuses on Water, Not

Immigration NYT

7.7.2006

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/07/us/07border.html

Border Fight Focuses

on Water, Not Immigration

July 7, 2006

The New York Times

By RANDAL C. ARCHIBOLD

CALEXICO, Calif. — For more than 100 years, as

their names imply, Calexico and its much larger sister city, Mexicali, south of

the border, have embraced each other with a bonhomie born of mutual need and

satisfaction in the infernal desert.

The pedestrian gate into Mexico clangs ceaselessly as Mexicans lug back bulging

bags from Wal-Mart and 99 Cent Stores in Calexico. The line into the United

States slogs along, steady but slower, through an air-conditioned foyer as men

and women trudge off to work and, during the school year, children wear the

universal face that greets the coming day.

Now, the ties that bind Calexico and Mexicali are being tested as a 20-year

dispute over the rights to water leaking into Mexico from a canal on the

American side is reaching a peak. Though the raging debate over illegal

immigration in the United States has not upset border relations here, some say

the fight over water could affect the number of Mexicans who try to cross here

illegally.

To slake the ever-growing thirst of San Diego, 100 miles to the west, the United

States has a plan to replace a 23-mile segment of the earthen All-American

Canal, which the federal government owns and the Colorado River feeds, with a

concrete-lined parallel trough.

The $225 million project would send more water to San Diego, by cutting off

billions of leaked gallons — enough for 112,000 households a year — that have

helped irrigate Mexican farms since the 1940's.

But Mexican farmers and their advocates say the lined canal would effectively

turn off the spigot for 25,000 people, including 400 farmers whose wells rely on

the seepage that has helped turn the powdery fields east of Mexicali, an

industrial city, into one of the biggest Mexican producers of onions, alfalfa,

asparagus, squash and other crops.

The farmers and their families ask what will they do if they cannot till the

fields and answer that they will cross the border, illegally if they have to, in

droves.

"They can't build a fence high enough to stop us," said Gerónimo Hernández, a

Mexicali farmer whose family has worked the fields for generations.

Juan Ignácio Guajardo, a lawyer in Mexicali who is helping a civic group there

and two environmental groups in Southern California fight the canal, said, "You

can't have it both ways," adding, "You can't take our water away and then say,

'We don't want immigration, either.' "

The dispute over the project was among the topics President Bush and President

Vicente Fox of Mexico discussed in an April meeting in Mexico.

[A federal judge ruled against environmental groups in the United States and a

Mexicali civic association in a lawsuit against the project, dismissing some

claims on June 26 on technicalities and deciding on July 3 that many of the

predicted effects on Mexico were "highly speculative" and that the federal

environmental law at issue did not apply beyond the border. The groups said they

were preparing an appeal. In addition, a separate lawsuit is pending in state

court.]

On the American side, managers of the Imperial Irrigation District, which

controls the canal and a vast water system that has turned swaths of the

California desert in the Imperial and Coachella Valleys into some of the most

fertile farmland anywhere, defend the plan.

They say the 1944 international treaty on the distribution of water from the

Colorado River, which feeds the canal, does not prohibit the concrete lining.

New agreements among the states and water utilities along the Colorado have

imposed limits on how much water can be tapped from the river, making every drop

count that much more.

"There is more need than water available," said the general manager of the

irrigation district, Charles Hosken. "When you find a point to access water, I

think it is our duty to go after it."

Mr. Hosken acknowledged that the project, which has been mired in legal

challenges and planning since the 1980's, "will have impact" on Mexico, but

said, "The fact is, the water belongs to the United States, and we have never

been compensated for it."

He said he was particularly angry at opponents of the project who invoke the

immigration debate, which while discussed here, has not set off the fiery

passions found elsewhere.

The notion that cutting off the leakage would drive up illegal immigration, he

said, was "quite a stretch" and a "scare tactic" intended to take advantage of

the charged atmosphere surrounding the debate.

But opponents said the project was moving forward without enough consideration

of its potential effects.

The federal lawsuit contended that a study in 1994 of the project's

environmental consequences was outdated and should be revised to take into

account changes of the last 12 years.

The groups argued in the suit that the original study did not fully take into

account a projected increase in air pollution if the fields were returned to

dust or the deterioration of Mexican wetlands if the leaking water were to dry

up and remove the habitat of endangered birds and lizards.

In the state lawsuit, filed in April, another environmental group contends that

the concrete lining and the shape of the new canal would produce swifter

currents that would endanger people and animals. That group says it plans to

seek a temporary restraining order against the project.

California has agreed to pay for 60 percent of the project, with the San Diego

County Water Authority financing the rest. Malissa Hathaway McKeith, president

of Citizens United for Resources and the Environment, a group in the federal

lawsuit, said Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger could halt the project by withholding

the state money until the environmental effects were studied more closely.

A spokeswoman for Mr. Schwarzenegger, Margita Thompson, said such a move was far

from likely because the governor thought that the water recovered from the

lining would lessen the need to tap the Colorado.

"This will help provide long-term stability in water management," Ms. Thompson

said.

The dispute has touched a nerve in Calexico, which, with a population of 33,000,

mostly Spanish speakers of Mexican descent, functions as a virtual suburb of

Mexicali, which has nearly one million residents.

The mayor and Council of Calexico have sided with the Mexicali farmers, taking

pains to make clear that Mexicans are welcome here in part because they fear

that economic distress in the region could damage their economy, which is buoyed

by Mexican wallets.

"If we didn't have Mexico," said Mayor Alex Perrone, who like many other city

residents was born in Mexicali and reared in Calexico, "we could not survive."

So intertwined are the towns that Calexico fire trucks race across the border

for emergencies. Mexicali children fill private schools in Calexico. Special

border-crossing cards known as laser visas make it easy for many Mexicans to go

back and forth, though some sneak in, too, hiding in cars or scaling the

steel-plate fence.

Ire against the new canal has grown in Mexicali, where bumper stickers opposing

it are turning up.

"How can they take away the farmers' water after all these years?" asked Juan

Rodolfo Rodríguez, a Mexicali shopkeeper who was buying a caffè latte at the

Starbucks shop here. "Americans always want more, but we are used to this."

Farmers like the Hernández family fear they would not have the resources to find

alternate water sources, like digging deeper wells to tap an underground

aquifer.

"It would be costly to maintain," said Luis Hernández, Gerónimo Hernández's

brother. "And who knows if it would give us the same amount of water?"

Border Fight Focuses on Water, Not Immigration, NYT, 7.7.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/07/us/07border.html

Graphic shows North

America's five Great Lakes, the world's largest supply of freshwater

and a major shipping route for Canada and the United States.

Water levels declined in 1998 and have remained low,

especially in Lakes Huron and Michigan,

forcing ships to take on lighter loads and sparking concern about shorelines and

wetlands.

REUTERS/Graphic

Low water in North America's Great

Lakes causes worry R

4.7.2006

http://today.reuters.com/news/newsArticle.aspx?type=scienceNews&storyID=

2006-07-04T053442Z_01_N19344774_RTRUKOC_0_US-ENVIRONMENT-GREATLAKES.xml

Low water in

North America's Great Lakes causes worry

Tue Jul 4, 2006 1:36 AM ET

Reuters

By Jonathan Spicer

TORONTO (Reuters) - Several massive vessels

have run aground on Michigan's Saginaw River this shipping season, caught in

shallow waters a few miles from Lake Huron.

The river port is as shallow as 13 feet in a passage that is supposed to be 22

feet deep, a sign of low water levels in North America's five Great Lakes --

Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario.

Water levels declined in 1998 and have remained low, forcing ships to take on

lighter loads and sparking concern about shorelines and wetlands in the Great

Lakes, the world's largest supply of freshwater and a major commercial shipping

route for Canada and the United States. Iron ore and grain are among the biggest

cargoes shipped on the lakes.

"It's a pretty different mindset to come off 30 years of above-average water

levels and to suddenly, since the late 1990s, have below-average levels," said

Scott Thieme, chief of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' Great Lakes Hydraulics

and Hydrology Office in Detroit.

Lakes Huron and Michigan, where water levels have declined the most, are down

about 3 feet (one meter) from 1997 and about 20 inches from their 140-year

average, according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's

Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory.

When homeowners on Lake Huron's Georgian Bay noticed wetlands were drying up,

the Georgian Bay Association funded a $223,000 report that last year concluded

shoreline alterations such as dredging and erosion in the St. Clair River, at

the bottom of the lake, were responsible.

In partial response, U.S. and Canadian governments approved funding for a $14.6

million study of the upper Great Lakes by the International Joint Commission,