|

History > 2006 > USA > Louisiana > Mississippi

Rebuilding (II)

A woman read a list of the deceased at a

ceremony today.

Mario Tama/Getty Images

Bush Repeats Vow to Help New Orleans

NYT

30.8.2006

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/08/30/us/nationalspecial/30katrina.html

Bush Repeats Vow

to Help New

Orleans

August 30, 2006

The New York Times

By ANNE KORNBLUT

and ADAM NOSSITER

NEW ORLEANS, Aug. 29 — Still at pains a year

after Hurricane Katrina to demonstrate his concern over the devastation it

caused, President Bush said Tuesday that he took “full responsibility” for the

slow federal response to the disaster as he made a carefully choreographed

pilgrimage to the city that suffered most.

As bells rang out through the streets, citizens gathered for prayer services and

residents hung banners in front of their tattered homes to commemorate the

anniversary of the storm, Mr. Bush sought to do what he had not accomplished a

year earlier: Demonstrate the depth of his understanding of the emotional and

physical toll the hurricane took on New Orleans.

“I’ve come back to New Orleans to tell you the words that I spoke on Jackson

Square are just as true today as they were then,” he told a largely friendly

audience at Warren Easton Senior High School, referring to his major nighttime

address on the storm last September.

That speech, itself a carefully planned event that came after most of the

victims had died, was seen as a turning point by White House advisers who

recognized the political damage done by the flawed government reaction.

“I have returned to make it clear to people that I understand we’re marking the

first anniversary of the storm,’’ he said, “but this anniversary is not an end.

And so I come back to say that we will stand with the people of southern

Louisiana and southern Mississippi until the job is done.”

Speaking at a former public school that was rebuilt as a charter school after

the storm, Mr. Bush restated his acceptance that ultimately he was responsible

for the federal response to the hurricane, which killed more than 1,700 people

in the gulf area and left hundreds of thousands of others displaced.

“I take full responsibility for the federal government’s response, and a year

ago I made a pledge that we will learn the lessons of Katrina and that we will

do what it takes to help you recover,” Mr. Bush said, drawing applause from the

crowd.

He also said he would try to get Louisiana a greater share of offshore oil

revenues and urged businesses to return to the region.

In repeated nods to the city’s extraordinary cultural past, Mr. Bush visited the

home of the music legend Fats Domino in the Lower Ninth Ward and listened to a

brass band. He talked about restoring the “soul” of New Orleans, even as he

acknowledged that much of the damage had not yet been repaired.

The city, he said, was calling its children home.

“I know you love New Orleans, and New Orleans needs you,” Mr. Bush said. “She

needs people coming home. She needs people — she needs those saints to come

marching back, is what she needs.”

He did not stray far from his script nor venture out of his motorcade as it sped

past some of the worst destruction in the Lower Ninth Ward, where rows of gutted

homes stood along deserted streets.

Instead, in a series of upbeat events designed to underscore progress, Mr. Bush

struck an optimistic — and at times almost defiant — tone. He portrayed the

anniversary as a starting point, deflecting questions about slow results. And

although he faced several challenges throughout the day, including a large

banner that read “Bush Failure” as his motorcade passed, Mr. Bush kept his focus

on future improvements. He met privately with several residents, but the White

House did not disclose their conversations.

Away from the presidential tour, there was private weeping at some of the ruins

of the Lower Ninth Ward, and at City Hall bereaved family members signed a giant

banner with hundreds of fleurs-de-lis, the city’s symbol, one for each victim.

At 9:38 a.m., Mayor C. Ray Nagin sounded a large silver bell on the City Hall

steps to mark a catastrophic early levee breach.

Huddling with loved ones at home, attending a ceremony in the heat or simply

working on their houses, the city’s citizens, it seemed, were reflecting Tuesday

on the disaster one year ago that altered a way of life here for a long while,

if not forever.

In its warm and breezy quiet, the day was very unlike the one filled with

violent winds and somber hints of catastrophe of a year ago. Out in the

neighborhoods, work went on, painfully and defiantly, in the 100 degree-plus

heat. Plunging on ahead with rebuilding, as more than one demonstrated they were

doing Tuesday, was a way of remembering too — of not being conquered by the

long-tentacled disaster and its aftermath. Several people said there were far

more important things to be done this day than attending one of the downtown

events.

“All this stuff on TV and all, nobody in this city has time to fool with that,”

said John Parker, a musician, outside his house, which took in over four feet of

water, on a ruined block of Upperline Street. “I figured it’s a good day to get

the ball rolling on fixing the house. So I got up and made an appointment with

our electrician.”

Mr. Parker and his wife gutted their home months ago, but are still months away

from moving back.

The memorial parade was just gearing up downtown, but Robert P. Davis, an

electrical inspector, was having no part of it.

“I’m working on my home, that’s what I’m doing,” Mr. Davis said brusquely, on a

block of Marengo Street where few of the neighbors have returned.

“What happened has happened,” he said, proudly showing off his “totally gutted,

reframed” house.

Mr. Davis is living, for now, in a FEMA trailer in the backyard. “We’ve got to

move on,” he said.

Others were not so sure that was possible just yet.

“It’s been a big day for everybody,” said Kirk Reasonover, a lawyer, hurrying

across Camp Street downtown.

Exiled from the city and his home for nearly four months, Mr. Reasonover said he

was determined to “spend time with my family” on this day. “Everybody who was

here on Aug. 27 and Aug. 28, 2005, is thinking about it,” he said. “It was one

of those moments you will never forget.”

The city does not need reminders of the storm; they are everywhere. But the date

itself, so often referred to since the storm, is its own particular sharp jog to

memory. Tuesday was special in that regard, and many here, including Mayor

Nagin, were feeling it.

This was a rough patch for the city, the mayor said. “I am personally having a

very difficult time with it,” he told several hundred assembled on the steps of

City Hall.

Mr. Bush’s day — a whirlwind more of sights and sounds than of substance — began

with a memorial Mass at the Cathedral-Basilica of St. Louis on Jackson Square

and concluded with Mr. Bush returning to his ranch outside Crawford, Tex.

After giving Mr. Domino — who was feared dead for a time in the early days of

the hurricane — a replica of a National Medal of Arts award that had been lost

in the storm, he drove past gutted homes to arrive at a group of freshly

constructed houses put together by Habitat for Humanity volunteers in recent

months.

After spending the night at his ranch, Mr. Bush will spend the rest of this week

shifting his focus away from Hurricane Katrina and back toward another landmark

of his presidency, the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. He is scheduled to make

campaign stops in Arkansas and Tennessee on Wednesday before delivering what is

expected to be a major address on terrorism in Salt Lake City on Thursday.

Mr. Bush had at least one exchange with a local resident that made reference to

the flawed response last year, and his role in it.

As Mr. Bush squeezed through tables at a pancake house where he ate breakfast, ,

a waitress asked, “Mr. President, are you going to turn your back on me?”

“No, ma’am,” he replied, with a laugh and a pause. “Not again.”

Bush

Repeats Vow to Help New Orleans, NYT, 30.8.2006, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/08/30/us/nationalspecial/30katrina.html

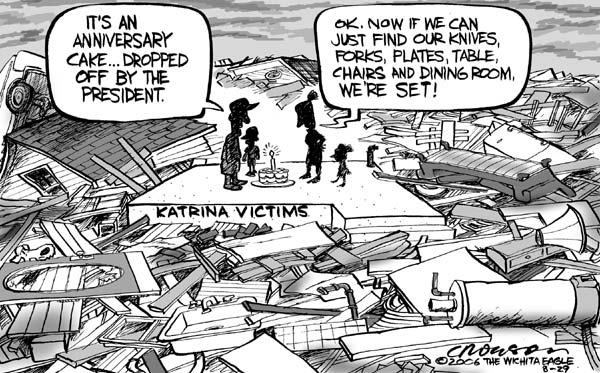

Richard Crowson

The Witchita Eagle, Kansas Cagle

30.8.2006

http://cagle.msnbc.com/politicalcartoons/PCcartoons/crowson.asp

A year later,

hearts still heavy in New

Orleans

Posted 8/29/2006 12:47 AM ET

USA Today

By Anne Rochell Konigsmark

NEW ORLEANS — The Big Easy isn't easy anymore.

One year after Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans

is frustrating, tiring, expensive and frightening. Hearts are heavy from living

amid so much destruction. Nerves are jangled as the 2006 hurricane season heats

up. And spirits are dampened every time another friend gives up and moves away.

"I survived Katrina but the anniversary killed me," jokes Mary Lee Murphy, 35,

who moved back to her unflooded Uptown apartment in November.

For some, the city has proved unbearable. The suicide rate has tripled,

according to the coroner's office. Others here search for ways to feel normal

again. Freshly planted flowers are blooming in front of gutted, uninhabitable

homes in the Broadmoor section of town. The local news ran a 10-minute feature

on the highly anticipated reopening of Commander's Palace, one of the city's

most famous restaurants, closed since the storm.

In the days before Aug. 29, 2005, as the approach of Katrina triggered the

annoying annual evacuation odyssey, New Orleanians had no idea their dreamy,

professionally lethargic, down-but-not-out lifestyle was about to be taken from

them. For weeks last September, virtually all 460,000 residents were stuck on

someone's sofa, in a hotel or on a cot in an arena somewhere. The shattered

pieces of a city, a culture, were strewn across the country. It has taken a year

just to get 200,000 people back.

That changes people, and it changes a place. The Rev. Aldon Cotton, pastor of

Jerusalem Baptist Church, counsels his weary flock with these words to encourage

endurance: "Whatever you had before Katrina, it didn't take two weeks to get it.

It took years."

Like thousands of New Orleanians, Cotton's congregants work at jobs by day and

on their broken personal lives by night. They come to him with their exhaustion,

their anger and their fears, he says. Cotton, who lost not only his church in

Central City to Katrina's floodwaters but also his home in eastern New Orleans,

tells them to focus on something simple.

"I tell people to pace themselves and look at what you did accomplish today,"

says Cotton, who commutes to New Orleans daily from a rented apartment 30

minutes away in Luling. "I was able to move a box today. I found a friend

today."

Heartaches and headaches

New Orleans, which always prided itself on being carefree, is now full of

headaches and heartaches. While people spent the first part of the year worrying

about big things — the levees, the amount of federal aid New Orleans would get,

the city's very survival — these days people are focused on little things.

The cost of home repairs has skyrocketed, and hiring a contractor can take

months. Meanwhile, rents are up 40% and insurance rates have doubled for many

homeowners. Exasperated residents have taken to creating their own street signs

to replace those still missing. Looting continues, especially at homes under

construction.

And everywhere, depressing piles of garbage and storm debris make it feel like

Katrina happened days ago, not a year ago.

"I just want the trash picked up," says Bill Hines, an attorney. Every other

week, he says, the trash haulers don't show up on his Uptown street near Tulane

and Loyola universities. "That's a sign the wheels have fallen off. It's like

the Third World. I just want the place to look normal. I am tired of explaining

it away."

New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin says red tape is holding up the city's ability to

access federal recovery money for things like cleanup. "The dollars have flowed

extremely, painfully slow," he said recently.

In neighborhoods all over the city, 80% of which flooded when the levees broke

following Katrina, houses sit empty, waiting for homeowners to make tough

decisions.

Cotton recently got an estimate for repairs to his home, which sat in 8 feet of

water after the storm. "It was more than the house cost," he says. He can't get

started until he receives money from the Louisiana Recovery Authority, which

will hand out as much as $7 billion in federal dollars to more than 100,000

homeowners this fall. Meanwhile, he's paying both his monthly mortgage and his

rent.

Cotton's church was so badly damaged it must be demolished. He plans to rebuild

across the street. Asked where he'll get the money for a new church, Cotton

says, "Well, that's a walk of faith." He has applied for a loan from the Small

Business Administration and for a donation from the Bush-Clinton Katrina Fund

set up by the former presidents.

"There's just a lot to be done," says Cotton, who lost both his legs in a train

accident when he was a boy. It wouldn't occur to Cotton to leave New Orleans.

The same is true for Susan Spicer, chef-owner of several New Orleans

restaurants. Even though her Lakeview home flooded, even though business at her

most famous restaurant, Bayona, in the French Quarter, is down almost 40%, she's

here for the long haul.

"It feels pretty good to be here, but it's a little scary," she says. Tourists,

who make up a large portion of her clientele, are noticeably absent these days.

And running a restaurant is more expensive, Spicer and others say. Wages are up

because of a severe worker shortage. Electric bills are at least 20% higher.

At the one-year mark, Spicer and her husband are still talking about what to do

with their house. "We're thinking we'll rebuild," she says. "But there was no

point in rushing back to a neighborhood that isn't really viable yet. Are we

going to spend all this money to redo a house when next door to us is a house

that hasn't been touched? It looks like a jungle."

Spicer worries that another hurricane could throw things further off track. "We

need one hurricane season with no problems under our belts," she says. "Then

people will breathe easier."

Even those who didn't lose homes or loved ones are suffering emotionally, says

Alvin Rouchell, chairman of psychiatry at Oschner Hospital, one of a handful of

open hospitals in metro New Orleans. He and other mental health professionals

say they have seen a rise in alcohol and drug abuse.

In a recent survey by the Council on Alcohol & Drug Abuse For Greater New

Orleans, 13% of respondents said they were drinking more since the storm. Bacco,

a French Quarter restaurant, has a post-Katrina special: Three glasses of wine

and one appetizer for $25.

"Most of us have been grieving the loss of the city we knew," Rouchell says.

"Every day you see destruction, abandoned houses. The recovery is taking longer

than anyone anticipated. People are tired, people are frustrated."

Obsessed with the storm

Mary Lee Murphy says she remains obsessed with the storm. "Last night, my

roommate and I had people for dinner and, dang it, if we didn't talk about where

we went when we evacuated. And we all know where we went."

Murphy says she dreams about Katrina almost nightly. "I've spent the last year

trying to understand what happened," she says. "What happened with the levees?

Why did all these people end up at the convention center and no one knew about

it? I drive out to Lakeview, drive out to the 9th Ward."

Every newspaper article, every newscast, every dinner conversation and encounter

at the bank eventually ends up being about Katrina. Everywhere are grim

reminders: The dirty water lines on the sides of houses. The cryptic markings

left on doors by rescue workers, indicating whether bodies were found inside.

The holes in roofs, hacked by residents climbing to escape the flood.

Murphy is hoping the anniversary will bring some relief. "Maybe the emphasis can

change from 'where were you, what happened to you?' to talking about rebuilding,

imagining where our city can be," she says.

Darren Smith would like to rebuild. At every turn, he says, something bars his

way. "Going back to New Orleans, it's not as easy as it sounds," says Smith, 40.

A year ago, Smith, his wife and his three daughters huddled in their attic as

floodwaters swept through their Lower 9th Ward home. They retreated to the roof,

were rescued by a boat, spent three nights at the Superdome and eventually wound

up in Houston. Smith, a longshoreman, lost his job when his company asked him to

return to New Orleans without his family and live on one of the cruise ships

reserved for first responders and Port of New Orleans workers.

"My kids were in shock" then, he says. "We saw the bodies in the water. I

couldn't leave them."

Smith says he tried unsuccessfully to get a job in Houston. Recently, he came

back to New Orleans and lived in a relative's trailer while he tried to gut his

home himself. He did not have flood insurance.

"I can't get any of the volunteer agencies to gut it, because they're all

overcrowded," he says. He can't get his own trailer, because the Lower 9th Ward

still lacks power and drinkable water — and FEMA won't set up trailers there

until utilities are reconnected.

"Home for me is not the French Quarter or the Garden District," he says,

referring to unflooded neighborhoods that today look exactly as they did before

the storm. "It's going to be at least three to five years before my area of the

city is ready. We all miss New Orleans, and we want to come home, but home is

not ready for us."

Smith was in Mobile, Ala., on Monday, interviewing for a job. "My neighbors are

dead, all my stuff is destroyed. It is really getting to me. I don't think I

want to deal with Louisiana anymore."

About 200,000 people have decided they have the means, and the will, to tough it

out. Van Gallinghouse, 43, owner of an Internet marketing company, says he and

his wife thought briefly about staying in Atlanta, where they evacuated last

August. Their New Orleans home flooded, and they have since sold it.

"Atlanta seemed to have all the luxuries we would want and all the

opportunities," says Gallinghouse, a New Orleans native who has three small

children. "But there's something about New Orleans. It's the culture and the

people and the soul."

Like many who have decided to stay, Gallinghouse and his friends have become

more civically active. They formed the organization Bravehearts to raise money

to encourage economic development, improve education and clean up trash.

"We know it's going to work out," he says. "It has to work out. Among my peers,

there's a great deal of resolve and hope."

And more gravity. "People are more serious now," Gallinghouse says. "This is top

of mind, and we're all concerned."

Today, Cotton says he will tell his parishioners this: "You have survived —

you're still alive." He'll remind them that at least 1,740 died in the storm,

and about 140 are still missing. "Just take a deep breath and let it out slow

and get ready to get back to work."

A

year later, hearts still heavy in New Orleans, UT, 29.8.2006,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2006-08-28-katrina-anniversary_x.htm

New Orleans Marks 1 Year After Katrina

August 29, 2006

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Filed at 3:14 a.m. ET

The New York Times

NEW ORLEANS (AP) -- A year after one of the

worst natural disasters in U.S. history, this shattered city turned its

attention to rituals of mourning and celebrations of life.

In pockmarked neighborhoods choked with weeds, in church pews and at City Hall,

residents were to gather Tuesday for vigils marking the anniversary of Hurricane

Katrina.

They plan to remember the dead, ringing bells to mark the moment one of the

city's flood walls breached and water engulfed the northern edges of the city.

Wreathes will be laid on the site of each successive levee break, dotting the

city with bouquets in a commemoration of the flood.

In one of the Crescent City's age-old traditions, a jazz funeral was to wind

through downtown streets, beginning with a somber dirge and ending with a song

of joy.

At the city's convention center, where for days haggard refugees waited in vain

for food, medical assistance and buses, President Bush was expected to join an

ecumenical prayer service. Others planned to mark the occasion privately at home

with their own prayers -- including personal calls for protection.

''I'm going to pray to the good Lord that he put his arms around the levees. I'm

praying that he hug the levees tight so they don't break again, that he keep us

safe,'' said 58-year-old Doretha Kitchens, whose home in the Lower Ninth Ward

was submerged under a 10-foot wave.

Katrina grazed Florida before making landfall at 6:10 a.m. on Aug. 29, 2005, in

Buras, a tiny fishing town 65 miles south of New Orleans on one of the fingers

of land jutting out into the Gulf of Mexico. Entire blocks of houses, bars and

shops vanished, whipped into the Gulf by a wall of water 21 feet high.

In New Orleans, the sun came out after the violent winds subsided, but the worst

was yet to come: The industrial canal began to leak, and when two sections of

the wall fell, a muddy torrent was released that yanked homes off their

foundations.

Throughout the city, other parts of the levee system began to fail. With each

breach came a cascade of water, until 80 percent of the city was submerged.

Nearly 1,600 people died in Louisiana, and the rest of the nation watched in

horror as survivors begged to be rescued from rooftops or freeway overpasses.

Forty-nine bodies remain unidentified in the city's morgue.

Throughout the city, white trailers still line driveways in neighborhoods where

debris is stacked up in piles and unchecked weeds have overtaken abandoned

houses. Only half the population has returned. Emergency medical care is doled

out in an abandoned department store, while six of New Orleans' nine hospitals

remain closed. Only 54 of 128 public schools are expected to open this fall.

The one-year mark is a reminder of how much needs to be done -- and of how far

each survivor has come.

''Only when it's dark can you see the stars,'' said the Rev. Alex Bellow, at a

gathering outside a school in the Lower Ninth Ward. ''So when they tell you,

'You're not going to make it,' you keep looking up.''

New

Orleans Marks 1 Year After Katrina, NYT, 29.8.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/us/AP-Katrina-One-Year-Anniversary.html?_r=1&oref=slogin

Katrina rebuilding "long way off"

Tue Aug 29, 2006 3:02 AM ET

Reuters

By Caren Bohan

GULFPORT, Mississippi (Reuters) - One year

after Hurricane Katrina battered the U.S. Gulf Coast and his political standing,

President George W. Bush acknowledged on Monday that a complete recovery was

still a long way off.

"There is hope down here, there is still a lot of work to be done," Bush said.

"This is an anniversary but it doesn't mean it's an end. Frankly it's just the

beginning of what is going to be a long recovery."

The August 29 anniversary of Katrina, which killed about 1,500 people and

devastated New Orleans, holds perils for Bush as it rekindles memories of

government missteps in the initial response to one of the worst U.S. natural

disasters.

As the midterm election approaches in November, Bush's approval ratings are near

40 percent, never having fully recovered from the damage they suffered in

Katrina's aftermath.

Listing progress on the Gulf Coast, Bush said Mississippi beaches, once littered

with debris, were now "pristine" and school districts across the area had

reopened, though many had to hold classes in trailers.

Stopping at a shipbuilding company where employees wiped gray boats with cloths,

Bush told reporters that the company, United States Marine Inc., was hiring and

noted there was a worker shortage, but housing also was scarce.

Pressed for a time frame for the rebuilding, Bush said: "Well it's hard for me

to say. I would say years, not months."

Bush flew later to New Orleans, where his motorcade passed neighborhoods with

some newly built homes and others with tattered roofs. He rode past the

Convention Center, where many flood victims fled only to become stranded in

stifling heat.

A sign on the Superdome said, "Reopening 9-25-2006, Go Saints," and a sign on a

pole said, "We tear down houses," with a phone number on it.

RACIAL AND ECONOMIC DIVISIONS

Bush was to dine with New Orleans officials, including Mayor Ray Nagin, who said

he wanted to see a faster flow of resources to the local level.

The horrors experienced at the Superdome and elsewhere in New Orleans stoked

concern about racial and economic divisions because blacks and the poor bore the

brunt of the suffering.

Asked if he believed race was a factor in the slow federal response to Katrina,

Nagin said: "If it would have been a bunch of rich people in New Orleans, I

think there would have been a different response. I really do."

Bush rejected the idea that race influenced the response.

"Whoever says that is trying to politicize a very difficult situation," Bush

told American Urban Radio Network in an interview. But he acknowledged the

hurricane had exposed a racial divide in the United States and said he hoped the

rebuilding could heal it.

Democrats, vying to win control of at least one chamber of Congress in the

November midterm election, are intent on reminding voters of flaws in the Bush

administration's relief effort and of dissatisfaction that continues in the

region.

House of Representatives Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi of California said the

storm exposed a "tragedy" of mismanagement and that the government was not

fulfilling its pledges.

"Hundreds of thousands of our fellow citizens still await the help in rebuilding

their hospitals, schools, businesses, and homes that was promised last fall,"

Pelosi said.

In Mississippi, Bush said that a "large check" in the form of $110 billion in

federal funds dedicated to the Gulf Coast was proof of the government's

commitment.

Mississippi Sen. Trent Lott said there was progress in the rebuilding but

frustrations remained with the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the flood

insurance program.

"But we're going to be working on this recovery for years, literally," Lott

said. "I view this not as an anniversary, not as a celebration, but as a

memorial, a moment to remember what we have been through -- the good, the bad

and the ugly -- and to recommit ourselves to going forward."

(Additional reporting by Tabassum Zakaria)

Katrina rebuilding "long way off", R, 29.8.2006,

http://today.reuters.com/news/articlenews.aspx?type=newsOne&storyID=2006-08-29T060707Z_01_N28316893_RTRUKOC_0_US-BUSH.xml&WTmodLoc=Home-C1-TopStories-newsOne-2

Bush Visits Gulf Coast, Stressing Progress

August 29, 2006

The New York Times

By ANNE E. KORNBLUT

NEW ORLEANS, Aug. 28 — On the eve of the first

anniversary of Hurricane Katrina’s strike here, President Bush returned to the

devastated region on Monday promising to continue federal assistance and, with

his presidency still under the shadow of the slow response to the storm, eagerly

pointed out signs of progress in reconstructing the Gulf Coast.

But as another storm rolled toward Florida, with thousands of victims from

Hurricane Katrina still uprooted, Mr. Bush admitted there were “a lot of

problems left.”

Winding his way through tattered towns in Mississippi on his way here, Mr. Bush

spent the day demonstrating empathy and optimism, touring rebuilt areas and

meeting with local officials and residents in his 13th trip to the area since

the storm.

The journey was part of a continuing effort to recast his image from last year,

when Mr. Bush stayed on the West Coast before cutting short his vacation to deal

with one of the most significant crises of his administration. His popularity

was severely damaged after the storm, which killed about 1,500 people and

flooded most of New Orleans, and it has never fully recovered.

In sweltering midday heat, his shirt soaked with sweat, Mr. Bush told a group of

Biloxi, Miss., residents that he knew the rebuilding was so slow that to some it

felt as if nothing was happening.

Still, Mr. Bush said, “For a fellow who was here and now a year later comes

back, things are changing.”

“I feel the quiet sense of determination that’s going to shape the future of

Mississippi,” he said.

In an event with echoes of his prime-time speech in Jackson Square here last

September, Mr. Bush spoke in a working-class neighborhood in Biloxi against a

backdrop of neatly reconstructed homes. But just a few feet away, outside the

scene captured by the camera, stood gutted houses with wires dangling from

ceilings. A tattered piece of crime-scene tape hung from a tree in the field

where Mr. Bush spoke. A toilet sat on its side in the grass.

After a dinner Monday night with New Orleans officials, including Mayor C. Ray

Nagin, Mr. Bush is scheduled to tour city neighborhoods on Tuesday and deliver

another speech. He is also planning to return to Jackson Square for a memorial

service at St. Louis Cathedral.

As the president spoke in Biloxi, he was flanked by Mississippi’s two senators,

Trent Lott and Thad Cochran and Gov. Haley Barbour, all three of them

Republicans, and Don Powell, the Gulf Coast reconstruction coordinator. Watching

from the sidelines was Mr. Bush’s chief of staff, Joshua B. Bolten, whose

presence was a reminder of the reshuffling at the White House after the former

chief of staff, Andrew H. Card Jr., failed to manage the storm crisis.

Nearby, along the ocean, ravaged antebellum homes and churches dotted the

waterfront. The beach from Gulfport, Miss., to Biloxi, was deserted. Debris hung

from trees and motels stood shuttered. Blue tarpaulins still patched the roofs

of most dwellings. Written in green spray paint on a fence around a home in

Biloxi was “You loot, I shoot.”

In Washington and around the country Monday, Hurricane Katrina continued to

occupy a prominent place in the political arena. Both the White House and

Democratic leaders on Capitol Hill issued “fact sheets” with competing

assertions about the rate of progress and the nation’s ability to cope with

another disaster.

“One year later, neither the tragedy Katrina caused — the flooding of New

Orleans and the devastation of the Gulf Coast — nor the tragedy that it exposed

— the extent of the federal government’s failure to provide a life of security

and dignity to all of our citizens — have been adequately addressed,”

Representative Nancy Pelosi of California, the House Democratic leader, said in

a statement.

In late August of 2005, as the hurricane approached and scientists warned of a

potential disaster, Mr. Bush was on vacation at his ranch outside Crawford,

Tex., where the most pressing problem was an antiwar protest.

When the storm actually hit and his advisers began to realize the scope of the

catastrophe, Mr. Bush was in Southern California on a campaign-style travel

swing. Images of a remote president playing guitar on a military base, then

later posing for a picture as he peered out the window of Air Force One as it

flew over the devastation helped fuel the perception that Mr. Bush failed to

respond adequately to the storm.

This year, Mr. Bush is also returning to Crawford — his final stop on Tuesday —

before heading out to campaign in Arkansas, Tennessee and Utah this week. The

overnight stay comes after an abbreviated vacation, in Crawford earlier this

month and at his parents’ home in Kennebunkport, Me., last weekend, and two days

of commemorating the hurricane anniversary.

Speaking to reporters Monday after visiting United States Marine Inc., a company

in Gulfport that builds military boats, Mr. Bush predicted that the rebuilding

effort would take “years, not months.”

“There will be a momentum, momentum will be gathered,” the president said.

“Houses will begat jobs, jobs will begat houses.”

But, he continued: “It’s hard to describe the devastation down here. It was

massive in its destruction, and it spared nobody. United States Senator Trent

Lott had a fantastic house overlooking the bay. I know because I sat in it with

he and his wife. And now it’s completely obliterated. There’s nothing.”

Bush

Visits Gulf Coast, Stressing Progress, NYT, 29.8.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/08/29/us/nationalspecial/29bush.html?hp&ex=1156910400&en=b47f879f3d3b3864&ei=5094&partner=homepage

'Sense of renewal' in Mississippi impresses

Bush

Updated 8/28/2006 11:07 PM ET

USA Today

By David Jackson

BILOXI, Miss. — A year ago, President Bush

visited this area ravaged by Hurricane Katrina and saw piles of rubble strewn

over beaches and neighborhoods. He met with people who lost everything.

On a return visit Monday, he said 98% of the

debris is gone, the beaches are pristine, and the Biloxi-Gulfport area is slowly

rebuilding. He praised the region's rebirth and the resolve of its residents to

restore their lives.

"It's a sense of renewal here. It may be hard for those of you who have endured

the last year to really have that sense of change, but for a fellow who was here

and now a year later comes back, things are changing," Bush said in the first

part of a two-day swing to mark today's anniversary of Katrina.

"There's still challenges. There's still more to be done," Bush said, noting

that it will take "years, not months" for a full recovery.

Bush, who spends today in New Orleans, said he understands the frustration of

some local residents who need housing grants. He said state housing plans are in

effect, and "checks have begun to roll." He pledged the federal government's

help, but only with state and local officials as partners.

As a hot sun beat down, Bush took a brief walking tour of a neighborhood where

temporary trailers abut houses under reconstruction. It was one of the first

areas he visited last year shortly after the hurricane reached land.

Bush's visit came as he and members of his administration were briefed on

Tropical Storm Ernesto, which was on track to hit Florida.

Neighborhood residents gave Bush a warm reception in this reddest of red states

that he easily carried in two elections.

"I think he's an all-right guy," said James Konz, 38, who does painting and

drywall work in Saucier, Miss. Konz, wearing a tank top that read, "I Survived

Hurricane Katrina," said Bush and his administration "did the best they could"

given the ferocity of the storm.

Others were less impressed. "He could have done better than he did," said Mary

Millender, 63, a retiree from Moss Point, Miss. "I'm not going to pay him any

attention."

The Mississippi coast still bears some scars of Katrina. Many buildings have

holes in them or are hollowed out completely, from old wooden churches to Las

Vegas-style casinos, modern condos to the antebellum mansion that once belonged

to Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Among the flattened palm trees and bent restaurant signs are signs of change.

One homemade sign says, "On The Road To Recovery." Another: "We Are Home — Will

Shoot — No Looting."

"I'm seeing a lot of progress, a lot of things coming back," said Donald Griggs,

a general contractor from Biloxi who has been keeping busy, after he listened to

and applauded Bush's remarks. "This tragedy that hit New Orleans and us was

bigger than anyone imagined."

In listing his post-Katrina efforts, Bush cited new plans for government

responses to disasters. He also promoted $110 billion in federal aid, including

programs for tax incentives, small-business loans and education assistance.

"Some of the hardest work is still ahead. We'll ensure federal money reaches the

individuals who need it to build their homes. And we'll stand by you as long as

it takes to get the job done," he said.

'Sense of renewal' in Mississippi impresses Bush, UT, 28.8.2006,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/washington/2006-08-28-bush-gulf-coast_x.htm

Emotional devastation surfaces from Katrina

Posted 8/28/2006 8:19 PM ET

USA Today

By Steve Sternberg

A year after Hurricane Katrina scoured the

Gulf Coast, the storm still rages in the minds of survivors, who now suffer

twice as much severe mental illness as existed in the region before landfall,

researchers reported Monday.

Katrina forced 500,000 people to evacuate and

carved its initials in a swath of Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama.

The first major attempt to probe survivors' mental status found that about 15%

of residents of the counties and parishes struck by the storm, or 200,000

people, have depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and other forms

of mental illness, twice as many as before.

About 11% now have severe mental illness, compared with 6% before the hurricane.

Nearly 20% said they had mild to moderate mental illness, compared with under

10% before.

Yet fewer people reported they were considering suicide than before the storm.

The finding didn't entirely surprise researchers, who say people can be

remarkably resilient when they have to be.

"Suicide rates always go down in times of war. ... People pull together," says

Ronald Kessler of Harvard Medical School, who led the study published online by

the Bulletin of the World Health Organization.

The finding seems to conflict with reports that New Orleans' suicide rate

tripled. But in an event such as Katrina, the vast majority of those who may

have contemplated suicide may be less likely to act on it because they realize

they are part of something bigger. Conversely, those with suicidal thoughts who

don't have others with whom to share the disaster experience may be more

inclined to kill themselves. So the findings are not inherently inconsistent,

Kessler says.

Kessler says the absence of suicidal thinking reflects a newfound faith in the

ability to start over. But he added that "optimism only goes on for so long"

after a devastating event.

Psychiatrist Eugenio Rothe of the University of Miami's Jackson Memorial

Hospital, who wasn't involved in the study, says there's reason to worry. "We

did a study in Miami after Hurricane Andrew," he says. "The first year, people

were busy getting through the day, rebuilding, getting their lives back in

order.

"Then it hits them how much they've lost. They start mourning their losses."

The new study, sponsored by the federal government, took advantage of a survey

carried out every 10 years to assess the nation's mental health. More than 820

participants in that survey lived in the region hit hardest by Katrina.

The responses, recorded from 2001 to 2003, were compared with a new survey of

1,043 Katrina survivors.

Among other findings:

•Almost half of people who didn't evacuate said they wanted to leave but

couldn't get away.

•Seven percent had to be rescued, had a brush with death or were assaulted.

•Almost 90% said their experiences helped them develop a deeper sense of meaning

in life. More than 75% said they had become more spiritual or religious.

Emotional devastation surfaces from Katrina, UT, 28.8.2006,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2006-08-28-katrina-emotions_x.htm

New Orleans visitors find a tale of two

cities

Mon Aug 28, 2006 5:15 PM ET

Reuters

By Peter Henderson

NEW ORLEANS (Reuters) - Alabama native Sarah

Jane Keith, 30, stopped on a desolate street of the New Orleans Lower Ninth Ward

where porches had teemed with neighbors a year ago, before Hurricane Katrina.

"I stood in the middle of the street and screamed. I cried. Nobody heard me,"

she described from another corner, across from a house reduced to splinters.

But the night before she had cruised down Bourbon Street, beneath neon daiquiri

signs and past barkers for strip shows, jazz and rock bands. "Things almost

looked normal," she said.

A year since Katrina devastated the Gulf Coast, visitors to New Orleans are

surprised to find two cities in one. The historic heart of town, such as the

French Quarter and the mansions of the Garden District, is pumping with life,

but around it vast neighborhoods are only starting to recover.

Katrina hit land on August 29, 2005, and killed about 1,500 across four states

according to the National Hurricane Center, but the brunt of the hurricane

missed New Orleans, as is clear from the nearby Mississippi coast, which was

flattened and largely still is.

The jazz city was laid low from floods when its levees burst.

Fetid water inundated 80 percent of the city and sat for weeks, but the

historical areas built on the highest ground were relatively unscathed,

requiring repairs and paint, but rarely rebuilding.

'BETTER THAN BEFORE'

"In many areas we go, 'God, that looks better than it did before.' There is some

cleanup they procrastinated about for years," said Ernie Hinz, of Hot Springs,

Arkansas, strolling through the French Quarter in the week before the first

anniversary of Katrina.

He visits the city once a year in late summer with his wife, Vicki, and they

felt safe among the brick and wrought iron of the Quarter. The familiar smell of

old beer and fish that wafted through Bourbon Street evoked memories, not fear.

"It is hard to say if the stench is worse than it ever has been because it

(always) is terrible," Vicki said.

Shriner conventioneer Lasala Stancil, who was in New Orleans for the first time

in his life, said the Quarter looked fine, although he had not seen it before

the storm.

"We're having a ball," he said.

French Quarter merchants, in fact, say they are suffering because not enough

potential visitors realize the heart of the city is fine. Many in storm-damaged

areas, by comparison, say Americans think the city is recovering well and have

quit paying attention.

Only about 230,000 residents are back in the city of New Orleans, about half the

pre-storm population, although some demographers say as much as 80 percent of

the residents of the metropolitan area have returned, squeezing into unflooded

housing outside the city proper.

STRUCK BY ENORMITY

Schools are opening for those back, and residents can measure painfully slow

progress in terms of each new house gutted of rotting furniture, each boat

pulled off a median, each new sandwich shop opening in a desolate area.

That was not clear to Fred and Pat Smith, two retired Californians looking

around the Lower Ninth. Their visit to their daughter in the Uptown area near

the Garden District had not prepared them for the storm damage still evident a

few blocks from where the Industrial Canal opened up.

Many square blocks have been cleared and lie vacant, but beyond that street

after street has houses pulled off foundations, twisted by the elements, full of

refuse and showing the dirty line where the flood waters sat.

"I'm absolutely overwhelmed at the destruction. It is unimaginable. Oh my

goodness, what is that over there?" asked Fred, pointing to a roof sitting in

the branches of a tree.

"You look at it on television or in the newspaper, and it doesn't even begin to

capture the magnitude of it. Not close," he said.

"That's right," agreed Pat, struck by the enormity of it a year after the storm

hit. "I can't think of enough adjectives to tell you."

(For more stories related to the anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, please go to

http://today.reuters.com/news/GlobalCoverage.aspx?type=katrina&src=GLOBALCOVERAGE_wire

)

New

Orleans visitors find a tale of two cities, R, 28.8.2006,

http://today.reuters.com/news/articlenews.aspx?type=inDepthNews&storyID=2006-08-28T211444Z_01_N22233792_RTRUKOC_0_US-WEATHER-HURRICANE-VISITORS.xml&WTmodLoc=Home-C5-inDepthNews-2

Anniversary Brings Out the Politics of

Commemoration

August 28, 2006

The New York Times

By ADAM NOSSITER

NEW ORLEANS, Aug. 27 — On the eve of Hurricane

Katrina’s first anniversary Tuesday, this city has become a giant political

talking point.

Finger-wagging Democratic congressmen are pouring down here, hoping to score

points a year into the stuttering recovery, and President Bush’s cabinet

secretaries have been staking out hopeful counterpositions among the ruins. The

president himself will spend two days in the region this week.

Weary citizens, meanwhile, await with apprehension the day and its revival of

painful memories. In New Orleans the anniversary will be marked with a solemn

bell-ringing ceremony on the steps of City Hall to commemorate the levee

breaches, and with a host of prayer services, wreath layings, colloquia and

discussion panels.

Democrats are seizing this moment of reckoning with something approaching glee,

while Republicans are handling it gingerly. For Democrats there are the

persistent scenes of destruction and the ongoing misery of lives upended, handy

backdrops for criticism of the Bush administration.

“We know the storm was a tragedy, but a bigger tragedy is how the federal

government responded,” Senator Harry Reid, the minority leader, said Thursday to

television cameras and a handful of onlookers in the parking lot of St. Bernard

Parish’s only functioning grocery store.

For Republicans there are more arcane indicators like the percentage of debris

removed or the number of Small Business Administration loans approved. A lengthy

report released last week by President Bush’s Gulf Coast recovery chief detailed

these and other initiatives, down to the number of passports being issued per

week by the reopened New Orleans passport agency (25,000) and the number of air

mattresses provided by the federal government (20,000).

Mr. Bush is set for visits to Mississippi on Monday and to New Orleans on

Tuesday that are expected to include speeches, neighborhood stops and attendance

at an ecumenical prayer service. He has designated Tuesday a National Day of

Remembrance. Last week, he pre-emptively played down the importance of the

event, cautioning that “a one-year anniversary is just that” and saying that

“it’s going to take a while to recover.”

The White House, aware of the widespread skepticism about its commitment to

rebuilding, will use this week’s visit to reinforce the message that the

president cares about the region and is intent on helping it recover. Instead of

heralding the money that has been allocated and spent, said Dan Bartlett,

counselor to the president, Mr. Bush will sound uplifting themes “to shine a

light on the true grit and character of the citizens who are rebuilding.”

Mr. Bartlett said Mr. Bush wanted to “send a message on behalf of all Americans”

that the storm’s victims would not be forgotten. “The president,” he said, “as

most Americans, will focus on the anniversary to reflect and remember and to

recommit ourselves to seeing the job through.”

Nonetheless, the White House sent five cabinet secretaries — from the

Departments of Commerce, Education, Justice, Health and Human Services, and

Housing and Urban Development — as well as the Gulf Coast reconstruction czar,

Donald Powell, to announce mini-initiatives and emphasize that progress was

occurring, despite visual evidence suggesting otherwise.

A housing project overhaul, more prosecutors for the local United States

attorney, $235 million for displaced students, millions more to rebuild oyster

beds: Mr. Bush’s deputies have been working to counter persistent

dissatisfaction from outside Louisiana with the quality of the federal response.

In New Orleans, resentment remains deep, particularly among blacks. At the

premiere of Spike Lee’s HBO hurricane documentary on Aug. 16 at the New Orleans

Arena, the crowd hooted vociferously when Mr. Bush appeared on the screen. Its

most enthusiastic applause came when local residents interviewed for the film

gave voice to the conspiracy theorists’ hobbyhorse: that the levees had been

blown up deliberately.

Elsewhere in Louisiana, Mr. Bush is not blamed and remains highly popular among

whites, a leading Republican pollster said. “They’re not going to hold Bush

responsible for New Orleans because they didn’t like it to start with,” said the

pollster, Bernie Pinsonat of Baton Rouge, adding, “How would we expect them to

recover when they haven’t been able to take care of themselves?”

Underscoring the point, Mr. Bush got a locally well-publicized lift last week

from a St. Bernard Parish citizen who had traveled to Washington in a replica

Federal Emergency Management Agency trailer to meet him, and who turned out to

be an ardent supporter of the president.

Going up against the Bush officials are about 20 Democratic members of Congress,

including Representative Nancy Pelosi, the House minority leader, as well as Mr.

Reid. The representatives will go on the now-obligatory bus tour of New Orleans

and participate in the ecumenical prayer service on Tuesday at the New Orleans

Convention Center.

There is the politics of commemorating the storm’s wreckage, and then there is

the wreckage itself. By week’s end the Washington visitors will have cleared

out, and the ruined neighborhoods will remain. Fears here that the region’s

lingering woes will be forgotten, never far from the surface, will be as sharp

as ever.

On Thursday, Mr. Reid’s motorcade breezed through the ruins of Chalmette, a

suburb just east of the Lower Ninth Ward that was completely inundated by

Hurricane Katrina. Much of it looks as if the storm hit last week, with blocks

of ghostly, vacant houses and empty shopping strips; less than a third of the

surrounding parish’s prestorm population of 75,000 has returned.

With brisk efficiency Mr. Reid, accompanied by Senator Mary L. Landrieu,

Democrat of Louisiana, strode through Andrew Jackson Elementary School, one of

only two schools open in the parish. Virtually all the students had lost their

homes and spent the preceding school year somewhere else. The parking lot is

crammed with narrow trailers that serve as living quarters for the teachers.

That unmistakable evidence notwithstanding, Mr. Reid called out to Christine

Elliers’s fifth-grade class, “Does anyone live in these little trailers?” The

response was immediate and unanimous. “We all do!” the class shouted back.

A further initiation into the realities of present-day South Louisiana awaited.

“Do we like them?” the teacher called out. “No!” the students shouted back. “Do

we have to put up with them?” Ms. Elliers asked. “Yeah!” the students shouted.

Local officials were thin on the ground in this conservative parish to hear Mr.

Reid say later, outside the grocery store: “What is needed in New Orleans is

public works projects. For as much money as we spend in one week in Iraq, we

could create 150,000 jobs.”

Lynn Dean, the chairman of the St. Bernard Parish Council, a veteran local

Republican, listened skeptically. “Typical partisan talk,” Mr. Dean said. “The

federal government has put billions of dollars down here already. A lot of the

money has been wasted.”

Sheryl Gay Stolberg contributed reporting from Washington for this article.

Anniversary Brings Out the Politics of Commemoration, NYT, 28.8.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/08/28/us/nationalspecial/28anniversary.html

ON THEIR OWN

In the absence of clear direction, New

Orleanians are rebuilding a patchwork city.

Sunday, August 27, 2006

The Times Picayune

By Gordon Russell

Staff writer

From the concrete porch of her 7th Ward

shotgun -- cracked now, thanks to Katrina's filthy floodwaters -- Alice Soublet

has an unobstructed view of New Orleans' future.

Or, more accurately, its possible futures.

"That one's been fixed up, this one . . . the one down there," Soublet said,

ticking them off as she looked down Republic Street at the properties being

actively revived.

Most of the doubles across the street are gutted and tidy. The debris has been

cleared, and at least three homes on Soublet's block, between Abundance and

Treasure streets near Interstate 610, are renovated and occupied. Five trailers,

three of them next to her house -- which has been cleaned but not fully

repaired, because of a dispute between Soublet and her insurer -- offer further

evidence of Republic Street's resurgence.

But the house two doors down from Soublet's could portend a grimmer future. With

a fallen tree atop the carport, a moldering van beneath it, and a jungle of

weeds in the front yard, the property could serve as a monument to Katrina's

devastation. Save for towering weeds, it looks much the way it did when the

floodwaters subsided 11 months ago. There's a similar eyesore catty-corner to

Soublet's place, although the weeds were trimmed last week, much to her relief.

This corner of the 7th Ward neatly captures the state of the city's recovery a

year after floodwaters laid waste to it: It's a patchwork quilt. Whether the

rehabilitation gains steam, or blight and abandonment spread and conspire to

threaten the neighborhood's future stability, remains an open question.

Count Soublet among the hopeful: "My street, it's looking pretty good,

considering the rest of the city," she said. "I think it's going to come back."

Her optimism is tempered by realism, though. She added, "It's going to take a

long time -- seven or eight years -- 'til it's complete."

Wait and see

Across the city, the buzz of saws and the whine of sanders can be heard almost

everywhere, from upper middle class Lakeview to the ravaged Lower 9th Ward.

By June 29, more than 56,000 property owners had taken out some sort of permit

from City Hall, more than one permit for every three structures in the city.

(Overall, more than 80,000 permits have been granted.) Given that the West Bank

and a sizable slice of the east bank did not flood, the activity suggests that

about half the owners of flooded properties have signaled an intent to do

something with them.

Having a permit, of course, is not the same as acting on it. Untold thousands of

homeowners snared permits before they were ready to start work for any number of

reasons -- because they didn't know how long City Hall would give them out for

free, because they wanted to be grandfathered in before new elevation standards

were adopted to reduce the threat of flood damage, because they were afraid

inaction would be used as an excuse for officials to seize their homes.

Clearly, some people are opting for a wait-and-see approach. Sean Reilly, a

member of Gov. Kathleen Blanco's Louisiana Recovery Authority, said local banks

have reported that up to $10 billion in insurance proceeds remains unspent.

Banker Joe Canizaro said he believes the real number may be only half that

large, but it's still a staggering amount.

Still, plenty of homeowners have begun work in earnest. The sights and sounds of

progress are everywhere: piles of construction debris, fleets of contractors'

pickup trucks, lawn signs advertising an electrician or a landscaper or a

homeowner's intention to come home.

It's difficult, however, to say where the action is liveliest. Every block,

every home has its own narrative. And while some neighborhoods have clearly

started to come back more quickly than others -- Broadmoor, Mid-City and

Pontchartrain Park come to mind -- it's very difficult to generalize about broad

swaths of terrain.

A neighborhood's progress depends on how its residents respond to a huge array

of factors. But in the first year, a couple of variables stand out.

As many predicted, recovery has been strongest in areas adjacent to those that

didn't flood, for obvious reasons: Flooding was apt to be less devastating in

such areas, and the proximity to shops and vital services has helped speed

rebuilding.

The other major factor is money. In general, wealthier sections are more apt to

show progress. Again, that's no surprise: Wealthier people are more likely to be

insured, and those who were underinsured have the resources or creditworthiness

to make up the difference.

While plenty of public money has been aimed at the city's recovery, money from

the state's $7.5 billion "Road Home" program has yet to reach the streets. As

that money begins flowing in coming weeks, observers expect another jolt to the

recovery, as those who lacked the means to begin repairs start to catch up with

their neighbors.

In the end, working-class homeowners may be the most likely to rebuild,

demographer Greg Rigamer believes, because their homes may be the only asset of

value they own. The wealthy, Rigamer noted, "can avoid adversity. They have

options."

A smaller footprint

Even with the huge infusion of federal aid on the way, it's unthinkable that all

parts of the city will thrive, most observers agree.

At the neighborhood level, that will have unpleasant consequences.

Shortly after the storm, experts warned strenuously that in the absence of a

carefully planned and controlled revival, New Orleans would succumb to the

"jack-o'-lantern effect" -- a gap-toothed revival in which renovated homes were

interspersed with blighted and abandoned structures that eventually would bring

down the neighborhood.

The nonprofit Urban Land Institute recommended starting the rebuilding process

in the city's more flood-resistant core and spreading out only as the city

regained the population density and economic vitality to make those areas

viable. The land-use panel of the mayor's Bring New Orleans Back Commission

called for a moratorium on building permits while severely flooded neighborhoods

were assessed.

Both ideas -- which came to be known as "shrinking the footprint" -- were

controversial, and Nagin rejected both, trumpeting his belief that property

rights are sacrosanct.

A few months later, the long-anticipated announcement of new elevation

guidelines by FEMA likewise disappointed homeowners and experts who though they

might offer guidance on how and where to rebuild.

The new FEMA rules did not bar development in any district of the city, and left

intact the elevations set in 1984. And even those 22-year-old requirements have

been easy to duck, given the Nagin administration's willingness to revise

household damage assessments to below the 50 percent level, at which compliance

with the revised maps becomes mandatory.

Nagin's laissez-faire approach, so far at least, has resulted in something

resembling the dreaded jack-o'-lantern effect. While two planning processes are

now belatedly under way -- one engineered by the City Council and the second by

the LRA -- many homeowners have jumped the gun and are rebuilding before the

blueprints have been completed, rendering them at least partially moot.

Many observers believe the mayor -- who faced a difficult re-election as he was

being asked to make politically delicate decisions -- shied away from making the

tough calls the situation called for, a critical mistake that could scar the

city for years to come.

John McIlwaine, senior fellow for housing at the ULI, said recently that the

future of some New Orleans neighborhoods can be seen in the empty, blighted

acres of some of America's most depopulated cities.

"I can take you through parts of North Philadelphia or Detroit or Baltimore and

show you what it will look like," he said.

Reed Kroloff, dean of Tulane University's architecture school and one of two

people who were to have overseen the aborted BNOB-backed planning process, says

the city's current status reflects "a complete failure of leadership at almost

every level."

"Some of it was through wanton neglect, some through honest error, some through

distraction . . . you name it, we suffered it. And here we are a year later and

very little has happened in terms of planning."

'A bunch of bull'

Such critiques irk Nagin, who rattles off a laundry list of planning efforts

that are either complete or under way. The idea that a lack of planning has

stymied the recovery is "a bunch of bull," he said.

Nagin's point is that the failure to disburse a dime of the federal housing

money has nothing to do with the fits and starts of the planning effort to date.

But the problem, according to those on the other side of the fence, is not that

a lack of planning has slowed the pace of aid. Rather, it has forced homeowners

to make up their minds about what to do without any clear direction from the

government. And while "planning" has occurred, none of yet has any force of law.

Reilly of the LRA believes the punting by City Hall and FEMA makes the ongoing

planning process that much more critical.

"If the city isn't going to inform decisions through its permitting, and FEMA is

not going to inform decisions through elevation requirements, then the planning

process has to do it," he said. "Those other mechanisms have fallen by the

wayside.

"I'm very fearful of the jack-o'-lantern effect," Reilly said. "My worst fear is

for the homeowner to take his nest egg, invest it back into the home, and two

years from now, look to the right and to the left and see vacant lots."

Nagin's critics would have preferred to see the process work in reverse, with

the government telling people where it planned to invest its resources -- on

parks, schools, roads, utilities and the like -- before they made decisions on

where to rebuild.

Reilly said he, like Nagin, believes in the marketplace.

"But the market needs information," he said. "Otherwise the market won't work."

Kroloff made a similar point.

"The mayor keeps saying he wants the market to determine things," Kroloff said.

"But there's not a single market in this country in which there's no

intervention. It's called taxes. Sometimes it's a tax, sometimes it's a tax

break. But we do not live in a free market.

"I encourage the mayor to stand up and say something other than, 'Let the market

decide.' That's planning not to plan. Let the mayor say, 'Here's some guidance.'

Why let this happen randomly? Why not encourage it to happen intelligently?"

Between the canals

Nagin believes his approach is working exactly as intended.

"The market is reacting properly," he said. "If you get the information out

there, the marketplace is going to make a good decision."

While some might say there's little information out there on which to base a

decision, Nagin said he has offered guidance to renovators -- though it may have

struck some homeowners as frustratingly vague.

On a number of occasions, he has said that public investment will follow

resettlement -- but, of course, would-be resettlers don't yet know how many

people their neighborhoods will attract.

Also, during the campaign season, Nagin offered general warnings to those who

would rebuild in parts of the Lower 9th Ward and low-lying sections of eastern

New Orleans. He didn't specify which areas he meant, but said he thought some

neighborhoods in those areas would struggle to recover.

He has since become somewhat blunter, although not necessarily more specific.

"New Orleans east is showing some signs (of recovery), but it's so vast, it's

going to hit the wall," he said. "There's just such a big footprint. I don't

think they're going to get the clustering they need. So I think you're going to

have little pockets in the east.

"I've been saying this publicly, and people are starting to hear it: low-lying

areas of New Orleans east, stay away from. Lower 9th Ward. I said it in Houston;

people are starting to hear it. That's what I'm telling people (in the Lower 9).

Move closer to the river. That stuff from Claiborne to the lake -- we can't

touch that."

Moreover, Nagin now says that the city's investments will be concentrated in the

area between the 17th Street Canal and the Industrial Canal, which he expects to

make a full recovery.

"We're going to focus most of the resources in here," he said.

There's still time

One advantage to Nagin's approach is that the planning process going on now can

make use of the decisions people have already made, rather than attempting to

anticipate them.

But there are a couple of major downsides. One is that the process is bound to

create a class of losers. Those who pour their money and energy into a

neighborhood that ultimately founders may well feel cheated.

"There are people who are going to regret the investments they make, because

there's nothing coming behind them," said Canizaro, the banker who led Nagin's

land-use panel. "I think you can already see it as you ride around."

Nagin said he believes those who decide at some point in the future that they

made the wrong decision will be able to opt for a government buyout.

The other drawback of the laissez-faire approach, Kroloff and Canizaro say, is

that the opportunity for big thinking -- rezoning, major new parks, transit

corridors -- has largely passed, because so much rebuilding has already begun.

But both say there is still time for the planning process to have a positive

effect on the city's future direction.

Already, planning groups are armed with data about what their neighbors are

doing. As tens of thousands of New Orleanians make their way through the LRA's

homeowner-aid program, their intentions will be fed to planners immediately,

Reilly said, helping to round out the picture.

While those developments will certainly help bring neighborhood futures into

focus, there's growing evidence that the city's longer-term future -- and the

future of any given neighborhood -- will rest more on its ability to attract new

residents than on its efforts to bring back the old ones.

The prototypical yardstick used to measure New Orleans' recovery is population,

which various estimates and surveys put at around 225,000, about half its

pre-Katrina size. But a plateau appears to have been reached.

A recent analysis of postal change-of-address forms showed a huge dropoff in the

number of New Orleanians returning home in the second quarter of the year.

Paul Lambert, who has overseen the planning process set in motion by the City

Council, took noted of low turnout at two recent out-of-town planning events --

one in Baton Rouge, one in Atlanta.

Lambert has also been looking over the results of recent polling by Xavier

University sociologist Silas Lee, which showed that a significant number of

those from flooded areas don't plan to come back. Other recent polls have found

similar entrenchment among the displaced.

Taking it all in, Lambert has begun to wonder whether the goals of the planning

process need to be recalibrated.

"I started to think in terms of, 'Have people already made their decisions? Is

this as much about attracting new families as in getting residents to return?' "

Lambert said. "Maybe they've made up their minds that they are in fact going to

sell their homes and have settled somewhere else."

Lambert noted that the focus -- on his part, and on the part of most who have

attended meetings -- is still on bringing back the displaced. But there's a

growing realization that "not everyone is coming back, and therefore we need

strategies to be able to attract new families in."

Shreveport demographer Elliott Stonecipher has been saying the same thing. He

believes one of the reasons New Orleans has historically struggled is because

the city is trapped in its traditions. Few may leave, but fewer still immigrate

into the city.

Katrina changed the former, of course, but Stonecipher believes too much

attention is still paid to the restoration of the pre-storm city. Some people

won't come back, he said. And others who did come back will move on, thanks to

the city's radical makeover.

That's OK, in his view. While some rocky years may lie ahead, Stonecipher thinks

that if the city can make inroads attacking its intractable problems -- crime,

corruption, poor schools, a lack of good jobs -- New Orleans' mystique and its

well-known pleasures will take care of the rest.

Those aren't trifling. For Soublet, the city's charms made her decision an easy

one.

"I know a lot of people don't want to come back," she said. "Myself, I love it

here. I wouldn't even think of living anywhere else. Even if it is messed up."

In

the absence of clear direction, New Orleanians are rebuilding a patchwork city,

The Times Picayune, 27.8.2006,

http://www.nola.com/news/t-p/frontpage/index.ssf?/base/news-6/1156665883265020.xml&coll=1&thispage=1

After Long Stress, Newsman in New Orleans

Unravels

August 10, 2006

The New York Times

By SUSAN SAULNY

NEW ORLEANS, Aug. 9 — On the morning after

Hurricane Katrina, when members of The Times-Picayune’s staff found themselves

marooned in its flooded building here, John McCusker refused to join most of his

colleagues in relocating to a remote newsroom in Baton Rouge.

After the building was evacuated, Mr. McCusker, a photographer for the paper,

swam through muck while managing to keep his equipment dry and, from a kayak,

captured some of the most harrowing images of the storm’s immediate aftermath.

Then, for months, he lived the misery he had been photographing, having lost his

possessions, his family’s home and his entire neighborhood to the hurricane. On

Tuesday, nearly a year after the storm, he seemed to snap.

In an episode that began as a traffic stop for erratic driving, the authorities

say, Mr. McCusker was halted once, pinned a police officer between cars by

backing up, then fled and drove into several cars and construction signs in the

Uptown neighborhood before being stopped again and finally subdued with a Taser

gun. In both stops, the police say, he begged officers to shoot him, telling

them he did not have enough insurance money to rebuild his home in the Gentilly

neighborhood and wanted to die.

“He was demanding it; he kept saying, ‘Just kill me, just kill me,’ ” said James

Arey, commander of the negotiation team of the Police Department’s special

operations division, who responded to the scene.

“He never stopped saying that, and made every attempt to hurt the police

officers with his automobile because that’s the only weapon he had,” Mr. Arey

said. “Our officers are well trained to recognize crises and attempts at

‘suicide by cop,’ and that’s what this was.”

As of Wednesday night, Mr. McCusker, a veteran member of the Times-Picayune

staff and son of an old New Orleans family, was in a jail cell under a doctor’s

care, having been charged with reckless operation of a vehicle and hit-and-run

driving, among other things.

The public unraveling of such a well-known local photographer shined light again

on the troubled state of mental health in New Orleans, where the struggle to

return to normalcy has produced an epidemic of post-traumatic stress and

depression and where psychiatric help is extremely limited.

The state has estimated that the city has lost more than half its psychiatrists,

social workers, psychologists and other mental health workers, many of whom

relocated after the storm. There are only three acute-care hospitals open in the

city now, fewer than 65 beds for adult psychiatric patients, and no psychiatric

crisis intervention unit that might have accepted Mr. McCusker after his arrest.

Mr. Arey, a friend of his, said it was better for him to be in a jail cell

rather than neglected in an overcrowded emergency room where officers could have

taken him.

“We have known patients who’ve sat in emergency rooms for days,” Mr. Arey said.

“I’m not exaggerating, literally days. We didn’t want him to sit for days. We

had grave concerns about his safety, and I thought he might be safer in jail

under suicide protection.”

Terry Baquet, the Page 1 editor of The Times-Picayune, which returned to its

building not long after the storm, tried to get to the scene of the chase to

speak with Mr. McCusker. They are friends, and before the hurricane their

children attended the same Catholic elementary school.

“I saw him in the back of a police car driving off,” Mr. Baquet said. “It was

just sad seeing him like that. I’d like to see him doing well again.”

When asked about sadness at the newspaper, which won two Pulitzer Prizes this

year for its Hurricane Katrina coverage, he added: “I don’t think you can tell,

and it’s fair to say everyone’s affected. We live with Katrina every day.”

In an interview with The American Journalism Review published this month, Mr.

McCusker said he had recently taken a leave of absence from the paper to

concentrate on dealing with the raw emotions left by the storm. He said he went

to therapy three times a week and spent a great deal of time sleeping off

exhaustion.

“You have to understand the depth of the horror that the city was,” he said.

After

Long Stress, Newsman in New Orleans Unravels, NYT, 10.8.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/08/10/us/10orleans.html

Critic’s Notebook

In New Orleans, Each Resident Is Master of

Plan to Rebuild

August 8, 2006

The New York Times

By NICOLAI OUROUSSOFF

NEW ORLEANS, Aug. 3 — Rebuilding a city, it

seems, is too important a task to be left to professional planners. At least

that’s the message behind a decision to place one of the most daunting urban

reconstruction projects in American history in the hands of local residents.

Ever since a botched attempt to develop a comprehensive plan for New Orleans

fell apart last winter, city and state officials have been straining to avoid

the sticky racial and social questions that are central to any effort to rebuild

and recover after Hurricane Katrina.

Their solution, hammered out in July, was to turn the planning process over to a

local charity, the Greater New Orleans Foundation. On Aug. 1 the foundation

opened a series of public meetings in which groups representing more than 70

neighborhoods would begin selecting the planners to help determine everything

from where to place houses to the width of sidewalks.

Mayor C. Ray Nagin has referred to the process as “democracy in action.” And,