|

History > 2006 > UK > Prison (III)

no credit.

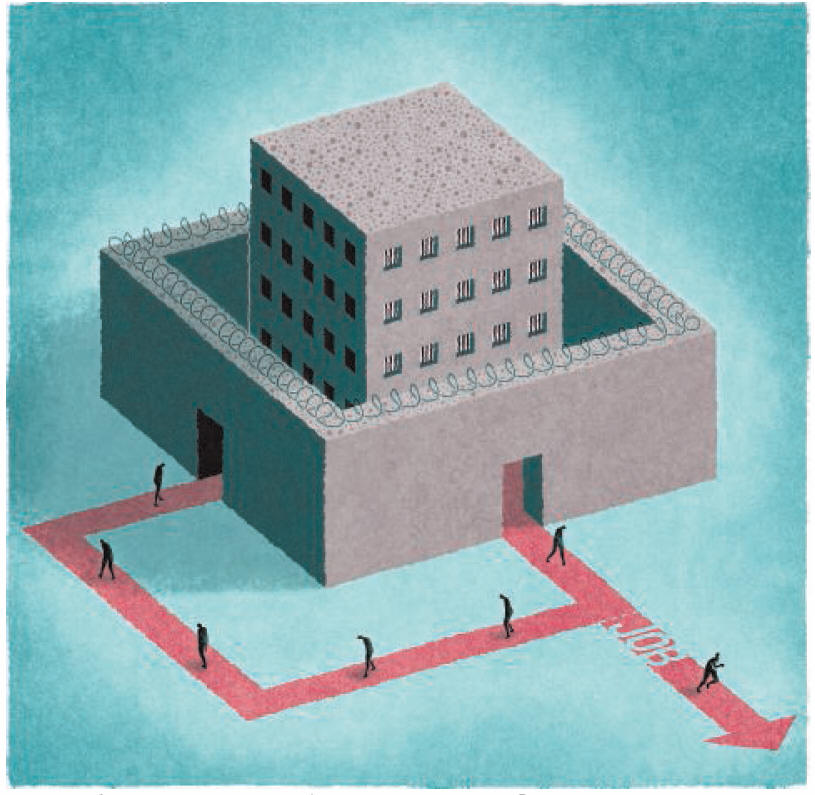

An honest day's graft

The prison service's 'can't do' culture is putting at risk attempts

to teach

work skills to inmates and cut reoffending rates

G Society

p. 6 6.9.2006

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2006/sep/06/

crime.penal

12.15pm

Prison watchdog

damns Scottish jail

practices

Thursday September 28, 2006

Press Association

SocietyGuardian.co.uk

The Guardian

A prison which houses 300 sex offenders has

the worst conditions of any Scottish jail, according to a report published

today.

The practice of "slopping out" at Peterhead

prison in Aberdeenshire was branded a "disgrace", with some prisoners being

locked in cells with their waste for up to 14 hours. In his annual report,

Scotland's chief inspector of prisons, Dr Andrew McLellan, also attacked

continuing uncertainty over the jail's future, stressing that a decision must be

made.

The prison was commended for introducing single cells for all prisoners and

fitting electrical power in each cell but Dr McLellan said: "Whilst these

changes are important, it does not hide the fact that prisoners in Peterhead are

living in the worst conditions in any prison in Scotland.

"The ending of slopping out in several prisons in the last two years has been

welcomed in reports. Its continuation in Peterhead remains a disgrace. It is the

worst single feature of prisons in Scotland."

The inspector noted a number of cells were very small and there was no access to

sanitation in five of the seven units, just a chemical toilet which was emptied

twice a week. The food and visiting arrangements at the prison were praised in

the report as was the limited drug use at the jail and the good relationship

between staff and inmates.

But Dr McLellan said he was concerned about the limited number of prisoners

taking part in the jail's Stop rehabilitation programme and the limited number

of opportunities for inmates to be prepared for release in the community.

In one of the report's nine recommendations, the inspector calls for a decision

to be made over the jail's future. The move follows speculation Peterhead could

be merged with Aberdeen's Craiginches to create a "super-prison".

Dr McLellan said the issue had been raised in last year's inspection and added

that the "demoralising effect of uncertainty" had now been given another year to

work. The inspector's recommendations also include the development of a suitable

pre-release programme, further rehabilitation programmes to address the current

waiting list and an allocated supervising social worker for every prisoner.

Responding to the report, the Scottish Prison Service (SPS) said getting rid of

slopping out was "not a realistic cost-effective option", given the age and

architectural structure of the prison, but that prisoners were able to access

out-of-cell facilities as far as possible.

Prison watchdog damns Scottish jail practices, G, 28.9.2006,

http://www.guardian.co.uk/prisons/story/0,,1883091,00.html

10.15am

Cockroaches and no toothbrushes:

the

Pentonville report

Thursday September 28, 2006

Guardian Unlimited

Peter Walker

Inspectors found a long and troubling list of

problems with Pentonville prison in north London when they carried out an

unannounced inspection between June 7 and 16 this year.

The building was infested with cockroaches and

other vermin; half the prisoners spent the bulk of the day inside their cells;

and many complained of a lack of respect from prison officers.

Overall, the team of inspectors, working for the chief inspector of prisons, Ann

Owers, noted "a failure to operate basic systems: a failure that was so endemic

that prisoners at induction were told not to expect to have a pillow or to have

their applications dealt with".

The 108-page inspection report, published today, acknowledged that the Victorian

jail had a number of inherent problems, many due to its age. "Although much

refurbishment has taken place, the original four cellblocks are as they were

when the prison opened in 1842," the report said.

The failures cited by the report included:

· "Throughout our prisoner survey, responses to most questions were

significantly worse than the comparator for other local prisons. Most

worryingly, prisoners reported much poorer relationships with staff than at the

last inspection, and there was an unusually high number of allegations of

assault and victimisation."

· "Prisoners in our survey and in groups reported significantly worse

relationships with staff than at the time of the last inspection. Only 43%,

compared with an earlier figure of 64%, believed that most staff treated them

with respect."

· "Unemployed prisoners, who represented half of the population, had only an

average of 2.5 hours out of cell while employed prisoners were out for about

seven. The average across the prison was about five hours, far less than the

over eight hours the prison was reporting."

· "External areas of the prison were better cared for than at the last

inspection. But many internal areas remained dirty and vermin-infested, and too

many prisoners lacked basic requirements, such as pillows, toothbrushes - and,

on one occasion, there was not even enough food to go round at the one cooked

meal of the day."

· "Prisoners were very dissatisfied with the quality and quantity of food ...

There was no pre-select choice, so religious and other special dietary

requirements were not always met."

· "We were told that efforts were being made to eradicate pests but the prison

was overrun with cockroaches and vermin. On our night visit, we found leftover

meals and opened flour sacks in the kitchen attracting these pests."

· "Forty-two per cent of prisoners said it was easy to get illegal drugs in the

prison, which was significantly more than in 2005."

· "First-night cells were better prepared. but there was no supportive

first-night strategy and night staff did not know the location of new arrivals.

In our survey, only 48% - against a comparator of 72% - said they had felt safe

on their first night."

Cockroaches and no toothbrushes: the Pentonville report, G, 28.9.2006,

http://www.guardian.co.uk/prisons/story/0,,1882790,00.html

Inspector lists basic failures at prison

in

corruption inquiry

Thursday September 28, 2006

Guardian

Alan Travis, home affairs editor

One of the UK's biggest Victorian jails is a

dirty, vermin-infested institution where 40% of inmates have been assaulted or

insulted by staff, according to an official inspection report published today.

Pentonville prison, where 14 staff were last

month suspended on corruption allegations, is so poorly run that new prisoners

were told on arrival not to expect to be given a pillow or a toothbrush, says

the chief inspector of prisons, Anne Owers.

One evening during the inspection there was not enough food to go round at the

only cooked meal of the day. She says the basic operations at the prison are at

best patchy, at worst non-existent.

Her follow-up inspection carried out in July found that while external areas of

the north London prison were better cared for, many internal areas remained

dirty and vermin-infested, and overcrowding was so acute that it held 1,125

prisoners when it was only built for 897.

Staff-prisoner relations have worsened since her 2005 inspection and with five

out of six recent suicides taking place within days of arrival, more prisoners

said they felt unsafe on their first night. Only 43% said they were treated with

respect by staff, compared with 64% a year ago.

"Fewer prisoners than in 2005 said they felt at risk from other prisoners, but

many more felt at risk from staff. Forty per cent, compared with 29% last time,

said they had been insulted or assaulted by staff," says Ms Owers, noting these

figures are far higher than for many other local jails.

The chief inspector says that easy availability of illegal drugs inside

Pentonville lies behind much of this fear of violence, but adds that some

prisoners feared reprisals if they complained about ill treatment by staff.

Ms Owers confirms that "use of force" by staff was high and the recording of how

and why it was used was inadequate.

At her previous inspection, the chief inspector found that prisoners were

routinely locked in their cells for most of the day. She says it is commendable

that they are now out of cells for more time, but the 140 unemployed prisoners

are still locked up for 22 hours a day.

Michael Spurr, director of operations for the Prison Service, said Pentonville's

senior management team had been strengthened and the governor was dealing firmly

with allegations against staff. The operational capacity of the prison was

temporarily reduced by 116 places after the 14 staff were suspended in the

corruption inquiry.

Inspector lists basic failures at prison in corruption inquiry, G, 28.9.2006,

http://society.guardian.co.uk/crimeandpunishment/story/0,,1882609,00.html

Police cells ready as jail crisis looms

As the prison population approaches 80,000,

governors warn of chaos

Sunday September 24, 2006

The Observer

Jamie Doward, home affairs editor

Emergency plans to house convicted prisoners

in police cells are being drawn up by the government as jails in England and

Wales come close to overflowing.

The last time cells were used was in 2002 when

23 police forces were ordered to provide space for up to 600 inmates at a cost

to the Prison Service of £10.4m.

A Home Office spokesman yesterday confirmed a plan had been drawn up to

reactivate this scheme, Operation Safeguard, but stressed that 'the National

Offender Management Service is doing everything it reasonably can to avoid'

this. But while Home Office insiders stress the scheme is a last resort, they

admit it now looks increasingly likely. On Friday the prison population touched

79,285 - just 1,015 places below full capacity.

Last week the director-general of the service, Phil Wheatley, told the prison

governors' conference that the jails could only find room for another few

hundred prisoners. This raises the troubling prospect that the prisons will be

full in weeks leaving the Home Office with no room for manoeuvre. 'When we are

full we are full,' Wheatley told the conference.

Last night the Prison Reform Trust issued figures showing that 88 out of the 142

prisons are operating above levels that the service accepts as allowing a decent

standard of accommodation. Of these 18 are breaching their operating capacity,

raising fears that security is being jeopardised, the trust said.

Juliet Lyon, its director, said the mounting crisis was caused by the

government's enthusiasm for locking people up: 'The prison population is

mushrooming out of control, the tabloids have the whip hand and the government

is still trying hopelessly to build its way out of a crisis of its own making.'

Lucie Russell, the director of SmartJustice, a charity campaigning for

community-based punishments rather than jail, said too many people were in

prison for relatively minor crimes.

'We need prisons to keep us safe from dangerous and violent offenders but three

out of five prisoners are serving time for non-violent crimes such as

shoplifting,' she said. 'Many of these offenders are mentally ill and have major

drug and alcohol problems.'

A Home Office spokesman disputed the trust's claims, saying there was often more

prison space than the raw figures suggested because some inmates were out on

home leave or for hospital appointments.

But with courts now sitting again after the summer, the total is expected to

start rising in the coming weeks, triggering a crisis. 'The next month is going

to be critical,' said Charles Bushell, leader of the Prison Governors

Association. Plans to add up to 1,000 places - including the conversion of an

army barracks near Dover into a jail - would have no impact until next year. 'By

which time we'll have been in a bit of a mess,' he said.

The government also wants to release more prisoners on tagging orders to offset

the crisis. But new figures obtained by the National Association of Probation

Officers (Napo) show that the companies operating the scheme have been plagued

by technical problems and communications breakdowns which mean violators are

often not returned to court for breaching their orders.

In the 10 months leading up to last January, Group Four Securicor failed to meet

its service levels 19 times, and its rival Serco did so 21 times. The failures

brought the two operators large fines.

'By 2009, over £250m worth of probation business could be contracted out,' said

Harry Fletcher, assistant general secretary of Napo. Yet the tagging scheme -

'the existing major private sector initiative - is expensive, fails to meet

service level agreements and the orders are regularly breached'.

Police cells ready as jail crisis looms, O, 24.9.2006,

http://observer.guardian.co.uk/uk_news/story/0,,1879735,00.html

Many serious offenders

still not screened before release

· Inquiry finds police not always kept informed

· Management of freed high risk offenders 'patchy'

Friday September 8, 2006

Guardian

Alan Travis, home affairs editor

Nearly four out of 10 serious sexual and violent offenders

released from prison on licence are being freed without being screened for their

risk to the public, according to a report published today by official criminal

justice watchdogs.

The investigation was ordered after a catalogue of

disastrous failures in the supervision by probation and police officers of

released serious offenders, culminating in the murder of the financier John

Monckton at his London family home by Damien Hanson soon after he had been

released early from a 12-year sentence for attempted murder.

The joint inquiry, carried out by the chief inspectors of probation, Andrew

Bridges, the police, Sir Ronnie Flanagan, and prisons, Anne Owers, says that

there is a "very patchy picture" in the way the criminal justice system manages

high-risk offenders after their release.

They also found that more attention needed to be given to preparing offenders

for release.

"In general, our findings reveal many encouraging examples of effective work,

but there was a clear need for improvement in about one-third of the casework we

looked at last year. While we found that much had been achieved, there were also

many areas for improvement," the inquiry concluded.

Among the shortcomings identified by the inspectors is the finding that in 39%

of cases a "risk of harm" screening had not been completed by the time a

prisoner was released on licence, and occasionally there were very lengthy

delays in their completion.

Even more worryingly, the inspectors found that "in only half of the relevant

probation cases had a comprehensive management plan been completed on high and

very high risk of harm offenders within five working days of their release from

prison".

The failure to include any assessment of the risk that Hanson might reoffend in

the report to the parole board that decided to release him was a key factor in

the Monckton murder case. This was despite an earlier assessment that there was

a 91% likelihood that Hanson would strike again.

The failure to undertake a rigorous risk assessment was also a feature of other

recent high-profile cases.

The inspectors' inquiry also found that the police were not always advised of

releases of prisoners on temporary licence and that there was little evidence in

some cases of preparation for release.

"In a fifth of cases of prisoners just starting their sentences and just over a

third of those prisoners about to be released, we found little evidence of

positive, proactive and timely work between prisons, probation and police," the

report says.

The inspectors acknowledged that the report was being published at a time of

heightened public concern and rising expectations about public protection

generally.

"Independent reviews of a small number of recent cases have clearly underscored

the importance of effective offender management," they say.

"While it will never be possible to eliminate risk when an offender is being

managed in the community, it is right to expect the work to be done to a

consistently high standard," the inspectors conclude.

A Home Office spokeswoman said that since the report was completed a year ago

the completion of risk assessments on the more serious offenders coming up for

release had significantly increased and now exceeded official targets.

"Offenders in custody and the community are managed accordingly through risk of

harm procedures, with resources concentrated on those who present the highest

risk," she said.

High-profile cases

Financier John Monckton was murdered in November 2004 during a robbery at his

Chelsea home by Damien Hanson, and accomplice Elliott White, while on probation.

Hanson had been released on parole three months earlier after serving 12 years

for attempted murder.

Naomi Bryant, 40, was murdered last August in Winchester by convicted sex

attacker Anthony Rice, nine months after he was released on parole after serving

16 years of a life sentence.

Marian Bates, 64, a Nottingham jeweller, was murdered by robber Peter Williams

in 2003, when he was electronically tagged by a private security firm and had

already missed seven probation and police appointments.

PC Ged Walker, 42, was murdered by drug addict David Parfitt in 2003 while he

was under the supervision of Nottinghamshire probation service after being freed

on early release.

Many serious

offenders still not screened before release, G, 8.9.2006,

http://society.guardian.co.uk/crimeandpunishment/story/0,,1867598,00.html

An honest day's graft

The prison service's 'can't do' culture

is putting at risk

attempts to teach work skills

to inmates and cut reoffending rates

Wednesday September 6, 2006

Guardian

David Wilson

The government seems certain it has found the answer to

help prevent offenders committing further crimes after leaving prison: find them

jobs. It has been at the forefront of attempts to introduce "real work" projects

into prisons. At the heart of such initiatives are the Reducing Reoffending

Employer Alliance; the Business in Prisons Initiative, which aims to help

offenders and ex-offenders to develop the skills required to start up their own

businesses on release; the Custody to Work scheme; and local projects such as

HMP Wandsworth's Learn2Earn project.

Some 1,500 prisoners are released on temporary licence

every day to undertake paid work in the community, and about 500 companies

already provide paid work for prisoners. Among them is National Grid; part of

the Offender Training and Employment Programme, it has trained and employed more

than 200 prisoners to date and aims to train and employ up to 1,000 offenders by

the end of 2007.

Opportunities

The government formalised much of its thinking in a green paper last December,

called Reducing Reoffending Through Skills and Employment. This states that

government strategy in relation to reducing reoffending is to "focus strongly on

jobs", and that "sustained employment is a key to leading a crime-free life".

Overall, when "looking forward", the green paper wanted to see "Enhanced

opportunities for education and training [which] need to lead to skills and

qualifications that are meaningful for employers and to stronger prospects of

effective re-integration into society through work. Activity to improve

individuals' employability while serving a sentence can be better connected to

real job opportunities, with employers more involved in design and delivery of

training."

A simple analysis of those entering and leaving our penal system suggests why

the government has chosen to focus on work skills. Almost 70% of prisoners were

not in work or training in the four weeks prior to going to prison, and 76% of

prisoners did not have jobs to go to on release. The government calculates that

as much as 18% of all crime can be attributed to former prisoners, at an

estimated cost of £11bn a year. Thus, a strategy based on improving the

employability of prisoners in tackling recidivism makes sense.

But what are "real job" opportunities in prison like? Can they deliver the

results the government hopes for? And, what do prisoners and prison staff think?

For the past 12 months, I have been researching "real" work in prisons. While no

one can doubt the government's sincerity in trying to make work inside more like

work in the community, or deny the importance of its focus on helping prisoners

to develop skills, the reality is that prison work - where it exists - is often

mundane, repetitive and boring, and that employers who might want to go into

partnership with prisons find the culture of jails and some prison staff so

inward-looking that unless they are persistent, they simply give up.

The Howard League for Penal Reform, for example, in the past year has developed

a design workshop, Barbed, in Coldingley prison in Surrey where the six

prisoners employed on the scheme are paid a real wage, and have the same rights

as other Howard League staff. Previously it had spent two years trying to get

the scheme set up at The Mount prison in Hemel Hempstead. Frances Crook,

director of the Howard League, says that "in the end, it was just impossible to

make any progress [at The Mount]".

After a poor report by the chief inspector of prisons, Anne Owers, in 2004, the

then governor at The Mount was moved and Crook "got the impression that they

felt besieged and battened down the hatches. It made them risk averse. We could

have helped them but they didn't want it.

"We got into detailed negotiations about prison regulations and the time that

the prisoners could spend in the workshops - especially if they could work over

lunch. It started to look as though they would only be allowed to work

part-time, and we just couldn't create a commercial business with people working

part-time. It was all done in the name of security. Prisons are very inflexible

because of security, but often that's an excuse."

These "excuses" were not just given by the prison internally but also supported

externally by the security culture at an administrative level within the the

prison service. Indeed, Crook described how "once everything goes to Croydon -

the administrative headquarters of the prison industries - it takes two years to

come out again". Another employer we spoke to described the prison industries as

having a "can't do culture", adding: "They want to prove that things can't be

done."

What was true for the prison industries was also all too apparent to some prison

staff, who clearly resented the opportunities that prisoners on real work

schemes were being offered. The head of learning and skills at one prison

described how she wouldn't consider introducing a real work scheme at the jail

because she didn't want to see prisoners "taunted" by prison staff.

Prisoners told us the various forms that this "taunting" could take. For some,

it was just "sarky comments. One [officer] said to me, 'This technology is

wasted on you lot - you're scum.'" Other prisoners spoke of being deliberately

locked up, or always being unlocked last so that they would be late for work.

One prisoner described how staff "were always trying to dig at us".

Mind expanding

There was no doubt that prisoners employed on real work schemes gained

enormously - and not simply from the real wage that they could earn, which

allowed them to send money to support their families. One prisoner described how

his work was "mind expanding - my brain has become active again". Another said:

"I've learned skills in here that I'll be able to use on the outside - all

prison work should be like this."

An inmate of Springhill prison near Aylesbury who works at the Oxford Citizen's

Advice Bureau (CAB) told us: "The way the system treats you from beginning to

end is what causes reoffending. By the time you get out of prison, you've lost

your confidence. You don't see yourself any more. You look in the mirror and you

say, 'Well - what am I now?' But if you have these work opportunities before you

come out of prison then you have your confidence. You have a chance."

What is true for this prisoner could equally be true for others. If the

government really wants to see progress on work in prisons, it seems that the

prison service - and many of its staff - needs to recognise the value work can

have for prisoners and, by helping them stay crime free on release, for us all.

· The report, Real Work in Prisons: Absences, Obstacles and Opportunities, by

David Wilson and Azrini Wahidin of the Centre for Criminal Justice Policy and

Research at UCE in Birmingham is available at

www.lhds.uce.ac.uk/criminaljustice or by calling Runjit Banger on 0121

331 6616.

An honest day's

graft, G, 6.9.2006,

http://society.guardian.co.uk/crimeandpunishment/story/0,,1865365,00.html

|