|

History > 2006 > USA > Immigration (III)

Senate Passes

Bill on Building Border Fence

September 30, 2006

The New York Times

By CARL HULSE

and RACHEL L. SWARNS

WASHINGTON, Sept. 29 — The Senate on Friday

approved the building of 700 miles of fence along the nation’s southwestern

border, fulfilling a demand by conservative Republicans to take steps to slow

the flow of illegal immigrants before exploring broader changes to immigration

law.

The Senate vote, 80 to 19, came as lawmakers finished a batch of legislation

before heading home to campaign. It sent the fence measure to President Bush,

who has promised to sign it despite his earlier push for a more comprehensive

approach that could lead to citizenship for some who are in the country

illegally.

House Republicans, fearing a voter backlash, had opposed any approach that

smacked of amnesty and chose instead to focus on border security in advance of

the elections, passing the fence bill earlier this month. With time running out,

the Senate acquiesced despite its bipartisan passage of a broader bill in May.

Congress also passed a separate $34.8 billion homeland security spending bill

that contained an estimated $21.3 billion for border security, including $1.2

billion for the fence and associated barriers and surveillance systems.

“This is something the American people have been wanting us to do for a long

time,” said Senator Jon Kyl, Republican of Arizona, whose state would be the

site of substantial fence construction.

Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff praised the money for border

security. He said it would “enable the department to make substantial progress

toward preventing terrorists and others from exploiting our borders and provides

flexibility for smart deployment of physical infrastructure that needs to be

built along the southwest border.”

Some Democrats ridiculed the fence idea and said a broader approach was the only

way to halt the influx. “You don’t have to be a law enforcement or engineering

expert to know that a 700-mile fence on a 2,000-mile border makes no sense,”

said Senator Richard J. Durbin of Illinois, the second-ranking Democrat in the

Senate. Nevertheless, more than 20 Democrats moved behind the measure.

The fence bill and homeland spending were among security-related measures the

Republican leadership was pushing through in the closing hours to bolster their

security credentials.

On a 100-to-0 vote, the Senate earlier sent a $447.6 billion bill for the

Defense Department to the president. It included $70 billion for operations in

Iraq and Afghanistan, a sum that will bring the total spent on those wars and

other military antiterrorism operations to more than $500 billion.

Lawmakers also sped through a port security bill that would institute new

safeguards at the nation’s 361 seaports, while a Pentagon policy measure stalled

in a Senate dispute.

“Passage of this port security bill is a major leap ahead in our efforts to

strengthen our national security,” said Senator Susan Collins, Republican of

Maine and chairwoman of the Senate homeland security panel.

At the urging of conservative groups and the National Football League, among

other interests, the port security measure carried legislation cracking down on

Internet gambling by prohibiting credit card companies and other financial

institutions from processing the exchange of money between bettors and Web

sites. The prohibition, which exempts some horse-racing operations, has

previously passed the House and Senate at different times but has never cleared

Congress.

“Although we can’t monitor every online gambler or regulate offshore gambling,

we can police the financial institutions that disregard our laws,” said Senator

Bill Frist of Tennessee, the majority leader, who lobbied to add the crackdown

to the port bill.

Because Congress failed to finish nine other required spending bills before the

Sept. 30 deadline, the Pentagon measure also contained a provision to maintain

spending for other federal agencies through Nov. 17 to give lawmakers time to

finish the bills in a post-election session.

In an end-of-session appeal to conservatives, Senate Republicans also brought up

a measure that could lead to criminal charges against people who take under-age

girls across state lines for abortions, but they were unable to get enough votes

to overcome procedural obstacles, and the bill stalled.

The atmosphere in the Capitol was somewhat tense as lawmakers were set to head

back to their districts for what is looming as a difficult election. And the

sudden resignation of Representative Mark Foley, Republican of Florida, after

the disclosure of sexually suggestive e-mail messages he reportedly sent to

teenage pages, added to the turmoil.

The fence legislation was one of the chief elements to survive the broader

comprehensive bill that President Bush and a Senate coalition had hoped would

tighten border security, grant legal status to most illegal immigrants and

create a vast guest worker program to supply the nation’s industries.

Senator Saxby Chambliss, Republican of Georgia, said the vote would build

credibility with conservative voters who have been skeptical of the government’s

commitment to border security.

“They have been under the impression that Congress has been a lot about

conversations about securing the border and not about action,” said Mr.

Chambliss, who opposes the legalization of illegal immigrants and voted against

the Senate immigration bill. “This is real action.”

But Republicans and Democrats alike acknowledged they were leaving the country’s

immigration problems largely unresolved. The border security measures passed do

not address the 11 million people living here illegally, the call for a guest

worker program by businesses or the need for a verification program that would

ensure that companies do not hire illegal workers.

And while Congress wants 700 miles of fencing, it was appropriating only enough

money to complete about 370 miles of it, Congressional aides acknowledged,

leaving it unclear as to whether the entire structure will be built. Dana

Perino, deputy White House press secretary, said Friday that Mr. Bush intended

to keep pressing Congress for a broader fix. She said the White House was

hopeful that Congress would return to the issue after the elections.

Senate Passes Bill on Building Border Fence, NYT, 30.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/30/washington/30cong.html

U.S. Project to Secure Borders

Will Begin

in Arizona Desert

September 22, 2006

The New York Times

By ERIC LIPTON

WASHINGTON, Sept. 21 — A rugged, largely

unpopulated 28-mile stretch of desert southwest of Tucson will be the testing

ground for the latest high-tech campaign by the United States government to

wrestle control of the border, this time in a partnership with Boeing, the

military and aerospace company.

Yet as top Department of Homeland Security officials and Boeing executives

gathered here on Thursday to hail the start of the project — which will cost an

estimated $2 billion over six years and eventually cover the entire 6,000 miles

of the Mexican and Canadian borders — they acknowledged that the first challenge

was disproving skeptics.

“The common complaint about the government is there is a lot of lofty rhetoric,

but the achievement always falls short,” Homeland Security Secretary Michael

Chertoff said. “We are very mindful of that. This is a very tall order. This is

about a solution we believe is going to do the job.”

Boeing, Mr. Chertoff formally announced, beat out other military contractors

that had bid to be the engineer of sorts for the program, the Secure Border

Initiative.

In that role, Boeing will be charged with lining up radar systems, cameras,

ground sensors, aerial vehicles, wireless communications equipment and vehicle

barriers, as well as traditional fences. It will also coordinate their use by a

Border Patrol force that is supposed to be made up of 18,000 officers by 2008.

That is the year by which the Department of Homeland Security intends to achieve

“operational control” of the border.

“There have never been before all of these tools collected in one plan,” said

the department’s deputy secretary, Michael Jackson. “It is a radical change in

business as usual at the border.”

The department is well aware of the decades of failed or incomplete

border-security efforts, including most recently a program known as the

Integrated Surveillance Intelligence System that turned out to be a $429 million

flop.

In that effort, begun in 1997, the cameras often broke down, fogged up in the

cold and rain, or were never installed as promised. Even when cameras or sensors

set off alerts, they most often were false alarms or, if they were not, the

Border Patrol often did not investigate them, a report by the department’s

inspector general said last year.

Given this track record, the department is starting small with a tiny section of

the Arizona border, so it can quickly adjust if the strategy does not work. That

means for now, the Boeing contract is worth $70 million, enough to cover setting

up the management for the entire project and to pay for installing the equipment

near the border post at Sasabe, Ariz., one of the busiest spots for illegal

crossings.

“We recognize we are in a fish bowl here, and everybody will be watching, and we

have to perform,” said J. Wayne Esser, the Boeing executive who supervised the

company’s pitch for the contract. “Failure is not an option.”

At Sasabe, Boeing intends to install nine tower-mounted camera and radar

systems, to track movement, day or night, in any weather. Sensors will be buried

in the ground to cover areas outside the radar’s reach, Mr. Esser said. When the

radar or camera notices activity, the cameras would be used to figure out how

many people are involved, if they are on foot or in a vehicle or if the motion

is an animal instead.

Border Patrol officers will be able to monitor the camera images from the field

through wireless laptop connections. The officers will also probably have tiny

unmanned aerial vehicles that can be launched from a truck to keep track of

illegal immigrants until they can be caught.

Boeing will rely on subcontractors for most of the equipment. Its primary job,

similar to the role it plays in building airplanes, will be to integrate all the

parts into a working system, officials said. It will be given work orders in

small increments, so Department of Homeland Security officials can monitor its

performance.

“Build a little, prove it, build more,” Mr. Jackson said.

The key, he said, will be figuring out how to use the Border Patrol staff most

effectively to pick up the illegal immigrants and return them to Mexico or other

countries of origin quickly enough so that the system is not overwhelmed.

Tamar Jacoby, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, a conservative

research group, said the technology sounded impressive, but he wondered if it

was enough.

“As long as you have half a million new jobs here going empty each year but for

these workers, they are going to find a way to get around whatever obstacles we

put in their way,” Ms. Jacoby said.

About $700 million has been budgeted for the project this year and next. While

officials had given an overall estimate of $2 billion, Mr. Chertoff refused to

put a price on the project. “As inexpensive as possible” was all he said.

U.S.

Project to Secure Borders Will Begin in Arizona Desert, NYT, 22.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/22/us/22border.html

Border Fence Must Skirt Objections

From

Arizona Tribe

September 20, 2006

The New York Times

By RANDAL C. ARCHIBOLD

TOHONO O’ODHAM NATION, Ariz., Sept. 14 — The

Senate is expected to vote Wednesday on legislation to build a double-layered

700-mile-long fence on the Mexican border, a proposal already approved by the

House.

If the fence is built, however, it could have a long gap — about 75 miles — at

one of the border’s most vulnerable points because of opposition from the Indian

tribe here.

More illegal immigrants are caught — and die trying to cross into the United

States — in and around the Tohono O’odham Indian territory, which straddles the

Arizona border, than any other spot in the state.

Tribal leaders have cooperated with Border Patrol enforcement, but they promised

to fight the building of a fence out of environmental and cultural concerns.

For the Tohono O’odham, which means “desert people,” the reason is fairly

simple. For generations, their people and the wildlife they revere have freely

crossed the border. For years, an existing four-foot-high cattle fence has had

several openings — essentially cattle gates — that tribal members use to visit

relatives and friends, take children to school and perform rites on the other

side.

“I am O’odham first, and American or Mexican second or third,” said Ramon

Valenzuela, as he walked his two children to school through one gate two miles

from his O’odham village in Mexico.

But the pushed-up bottom strands of the cattle fence and the surrounding desert

littered with clothing, water jugs and discarded backpacks testify to the growth

in illegal immigrant traffic, which surged here after a Border Patrol

enforcement squeeze in California and Texas in the mid-1990’s.

Crossers take advantage of a remote network of washes and trails — and sometimes

Indian guides — to reach nearby highways bound for cities across the country.

Tribal members, who once gave water and food to the occasional passing migrant,

say they have become fed up with groups of illegal immigrants breaking into

homes and stealing food, water and clothing, and even using indoor and outdoor

electrical outlets to charge cellphones.

With tribal police, health and other services overwhelmed by illegal

immigration, the Indians welcomed National Guard members this summer to assist

the Border Patrol here. The tribe, after negotiations with the Department of

Homeland Security, also agreed to a plan for concrete vehicle barriers at the

fence and the grading of the dirt road parallel to it for speedier Border Patrol

and tribal police access. The Indians also donated a parcel this year for a

small Border Patrol substation and holding pen.

Tribal members, however, fearing the symbolism of a solid wall and concern about

the free range of deer, wild horses, coyotes, jackrabbits and other animals they

regard as kin, said they would fight the kind of steel-plated fencing that

Congress had in mind and that has slackened the crossing flow in previous hot

spots like San Diego.

“Animals and our people need to cross freely,” said Verlon Jose, a member of the

tribal council representing border villages. “In our tradition we are taught to

be concerned about every living thing as if they were people. We don’t want that

wall.”

The federal government, the trustee of all Indian lands, could build the fence

here without tribal permission, but that option is not being pressed because

officials said it might jeopardize the tribe’s cooperation on smuggling and

other border crimes.

“We rely on them for cooperation and intelligence and phone calls about illegal

activity as much as they depend on us to respond to calls,” said Chuy Rodriguez,

a spokesman for the Border Patrol in Tucson, who described overall relations as

“getting better and better.”

The Tohono number more than 30,000, including 14,000 on the Arizona tribal

territory and 1,400 in Mexico. Building a fence would impose many challenges,

apart from the political difficulties.

When steel fencing and other resources went up in California and Texas, migrant

traffic shifted to the rugged terrain here, and critics say more fencing will

simply force crossers to other areas without the fence. Or under it, as

evidenced by the growth in the number of tunnels discovered near San Diego.

The shift in traffic to more remote, treacherous terrain has also led to

hundreds of deaths of crossers, including scores on tribal land here.

The effort to curtail illegal immigration has proved especially difficult on the

Tohono O’odham Nation, whose 2.8 million acres, about the size of Connecticut,

make it the second largest in area.

Faced with poverty and unemployment, an increasing number of tribal members are

turning to the smuggling of migrants and drugs, tribal officials say.

Just this year, the tribal council adopted a law barring the harboring of

illegal immigrants in homes, a gesture to show it is taking a “zero tolerance”

stand, said the tribal chairwoman, Vivian Juan-Saunders.

Two members of Ms. Juan-Saunders’s family have been convicted of drug smuggling

in the past several years, and she said virtually every family had been touched

by drug abuse, smuggling or both.

Sgt. Ed Perez of the tribal police said members had been offered $400 per person

to transport illegal immigrants from the tribal territory to Tucson, a 90-minute

drive, and much more to carry drugs.

The Border Patrol and tribal authorities say the increase in manpower and

technology is yielding results. Deaths are down slightly, 55 this year compared

with 62 last year, and arrests of illegal immigrants in the Border Patrol

sectors covering the tribal land are up about 10 percent.

But the influx of agents, many of whom are unfamiliar with the territory or

Tohono ways, has brought complaints that the agents have interfered with tribal

ceremonies, entered property uninvited and tried to block members crossing back

and forth.

Ms. Juan-Saunders said helicopters swooped low and agents descended on a recent

ceremony, apparently suspicious of a large gathering near the border, and she

has complained to supervisors about agents speeding and damaging plants used for

medicine and food.

Some traditional and activist tribal members later this month are organizing a

conference among eight Indian nations on or near the border to address concerns

here and elsewhere.

“We are in a police state,” said Michael Flores, a tribal member helping to

organize the conference. “It is not a tranquil place anymore.”

Mr. Rodriguez acknowledged the concerns but said agents operated in a murky

world where a rush of pickups from a border village just might be tribal members

attending an all-night wake, or something else.

“Agents make stops based on what they see,” he said. “Sometimes an agent sees

something different from what tribal members or others see.”

Agents, he added, are receiving more cultural training, including a new cultural

awareness video just shot with the help of tribal members.

“Our relations have come a long way” in the past decade, he said.

Mr. Valenzuela said several agents knew him and waved as he traveled across the

border, but others have stopped him, demanding identification. Once, he said, he

left at home a card that identifies him as a tribal member and an agent demanded

that he go back into Mexico and cross at the official port of entry in Sasabe,

20 miles away.

“I told him this is my land, not his,” said Mr. Valenzuela, who was finally

allowed to proceed after the agent radioed supervisors.

Mr. Valenzuela said he would not be surprised if a big fence eventually went up,

but Ms. Juan-Saunders said she would affirm the tribe’s concerns to Congress and

the Homeland Security department. She said she would await final word on the

fence and its design before taking action.

Members of Congress she has met, she said, “recognize we pose some unique issues

to them, and that was really what we are attempting to do, to educate them to

our unique situation.”

The House last week approved a Republican-backed bill 238 to 138 calling for

double-layer fencing along a third of the 2,000-mile-long border, roughly from

Calexico, Calif., to Douglas, Ariz.

There is considerable support for the idea in the Senate, although President

Bush’s position on the proposal remains uncertain. The Homeland Security

secretary, Michael Chertoff, has expressed doubts about sealing the border with

fences.

Border Fence Must Skirt Objections From Arizona Tribe, NYT, 20.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/20/washington/20fence.html

More Muslims Arrive in U.S., After 9/11 Dip

NYT 10.9.2006

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/10/nyregion/10muslims.html?hp&ex=

1157860800&en=a1703d031d2a4f73&ei=5094&partner=homepage

House Republicans Will Push

for 700 Miles

of Fencing

on Mexico Border

September 14, 2006

The New York Times

By RACHEL L. SWARNS

WASHINGTON, Sept. 13 — House Republicans

announced Wednesday that they would move swiftly to pass legislation requiring

the Bush administration to build 700 miles of fencing along the Mexican border

to help stem the flow of illegal immigrants and drugs into the United States.

The legislation, which is expected to go to the House floor for a vote on

Thursday, would require construction of two layers of reinforced fencing along

stretches of California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas that are considered among

the most porous parts of the border.

It would also require officials of the Department of Homeland Security to

establish “operational control” over all American land and sea borders by using

Border Patrol agents, fencing, satellites, cameras and unmanned aerial vehicles.

The bill is the first in a series of border security measures House Republicans

have promised to pass before the midterm elections in November.

The House majority leader, Representative John A. Boehner, Republican of Ohio,

hailed the legislation as “a critical step towards shutting down the flow of

illegal immigration into the United States.”

Democrats promptly criticized the plan as political grandstanding intended to

energize conservative voters before the elections.

The House passed a nearly identical fencing provision as part of a border

security bill in December. Michael Chertoff, the homeland security secretary,

has publicly raised doubt about the effectiveness of border fencing,

particularly in remote desert areas.

While the Senate easily approved 370 miles of border fencing in its own

immigration bill in May, it is unclear whether the two chambers will be able to

reach agreement on the issue before Congress recesses this month. House leaders

have said they will not support the Senate bill, which would create a guest

worker plan and put millions of illegal immigrants on a path to citizenship in

addition to toughening border security.

Jennifer Crider, a spokeswoman for the House Democratic leader, Representative

Nancy Pelosi of California, dismissed the fence bill as partisan politicking.

“Republicans have a record of failure on border security,’’ Ms. Pelosi said,

“and this is their attempt to cover up that record.’’

House Republicans countered that immigration hearings held across the nation in

August showed that Americans expected Congress to toughen border security,

particularly while the country remained under threat of terrorist attacks.

Congressional staff members predicted that some House Democrats, especially

those from border states, would support the fencing bill.

The barriers, which are to be accompanied by additional lighting, cameras and

ground sensors, would be built near Tecate and Calexico on the California

border; Columbus, N.M.; and El Paso, Del Rio, Eagle Pass, Laredo and Brownsville

in Texas.

House Republicans have also proposed counterfeit-proof Social Security cards for

citizens and immigrants searching for work, measures that would require the

deportation of immigrants linked to Central American gangs and an increase in

the number of Border Patrol agents as part of their border security agenda.

“The first priority of the American people is secure borders,’’ said

Representative Peter T. King, Republican of New York, who is the chairman of the

House Homeland Security Committee.

House Republicans said they were encouraged by what they called the success of a

14-mile fence at San Diego that was mandated by Congress in 1996. Crime rates

have dropped by 47 percent since the fence was constructed, they said, and the

number of illegal immigrants captured dropped to about 9,000 in 2005 from about

200,000 in 1992.

Amy Call, a spokeswoman for the Senate majority leader, Bill Frist of Tennessee,

said Senate Republicans would consider the legislation.

“The leader believes very strongly that we need to secure the border,’’ Ms. Call

said. “We’ll look at all options to do that.’’

Senator Jeff Sessions, the Alabama Republican who championed the fencing

provision in the Senate, praised House Republicans for pushing ahead with the

legislation. Mr. Sessions said he was concerned that the Senate proposal, which

had been attached to the military appropriations bill, might not receive

adequate financing.

“They’ve put forth a strong barrier bill,’’ Mr. Sessions said of House

Republicans. “It’s time for us to complete the job.’’

House

Republicans Will Push for 700 Miles of Fencing on Mexico Border, NYT, 14.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/14/washington/14immig.html

More Muslims Arrive in

U.S., After 9/11 Dip

September 10, 2006

The New York Times

By ANDREA ELLIOTT

America’s newest Muslims arrive in the

afternoon crunch at John F. Kennedy International Airport. Their planes land

from Dubai, Casablanca and Karachi. They stand in line, clasping documents. They

emerge, sometimes hours later, steering their carts toward a flock of relatives,

a stream of cabs, a new life.

This was the path for Nur Fatima, a Pakistani woman who moved to Brooklyn six

months ago and promptly shed her hijab. Through the same doors walked Nora

Elhainy, a Moroccan who sells electronics in Queens, and Ahmed Youssef, an

Egyptian who settled in Jersey City, where he gives the call to prayer at a

palatial mosque.

“I got freedom in this country,” said Ms. Fatima, 25. “Freedom of everything.

Freedom of thought.”

The events of Sept. 11 transformed life for Muslims in the United States, and

the flow of immigrants from countries like Egypt, Pakistan and Morocco thinned

dramatically.

But five years later, as the United States wrestles with questions of terrorism,

civil liberties and immigration control, Muslims appear to be moving here again

in surprising numbers, according to statistics compiled by the Department of

Homeland Security and the Census Bureau.

Immigrants from predominantly Muslim countries in the Middle East, North Africa

and Asia are planting new roots in states from Virginia to Texas to California.

In 2005, more people from Muslim countries became legal permanent United States

residents — nearly 96,000 — than in any year in the previous two decades. More

than 40,000 of them were admitted last year, the highest annual number since the

terrorist attacks, according to data on 22 countries provided by the Department

of Homeland Security.

Many have made the journey unbowed by tales of immigrant hardship, and despite

their own opposition to American policy in the Middle East. They come seeking

the same promise that has drawn foreigners to the United States for many

decades, according to a range of experts and immigrants: economic opportunity

and political freedom.

Those lures, both powerful and familiar, have been enough to conquer fears that

America is an inhospitable place for Muslims.

“America has always been the promised land for Muslims and non-Muslims,” said

Behzad Yaghmaian, an Iranian exile and author of “Embracing the Infidel: Stories

of Muslim Migrants on the Journey West.” “Despite Muslims’ opposition to

America’s foreign policy, they still come here because the United States offers

what they’re missing at home.”

For Ms. Fatima, it was the freedom to dress as she chose and work as a security

guard. For Mr. Youssef, it was the chance to earn a master’s degree.

He came in spite of the deep misgivings that he and many other Egyptians have

about the war in Iraq and the Bush administration. In America, he said, one

needs to distinguish between the government and the people.

“Who am I dealing with, Bush or the American public?” he said. “Am I dealing

with my future in Egypt or my future here?”

Muslims have been settling in the United States in significant numbers since the

mid-1960’s, after immigration quotas that favored Eastern Europeans were lifted.

Spacious mosques opened in Chicago, Los Angeles and New York as a new, highly

educated Muslim population took hold.

Over the next three decades, the story of Muslim migration to the United States

was marked by growth and prosperity. A larger percentage of immigrants from

Muslim countries have graduate degrees than other American residents, and their

average salary is about 20 percent higher, according to Census Bureau data.

But Sept. 11 altered the course of Muslim life in America. Mosques were

vandalized. Hate crimes rose. Deportation proceedings were begun against

thousands of men, and others were arrested in an array of terrorism cases.

Some Muslims changed their names to avoid job discrimination, making Mohammed

“Moe,” and Osama “Sam.” Scores of families left for Canada or returned to their

native countries.

Yet this period also produced something strikingly positive, in the eyes of many

Muslims: they began to mobilize politically and socially. Across the country,

grass-roots organizations expanded to educate Muslims on civil rights, register

them to vote and lobby against new federal policies such as the Patriot Act.

“There was the option of becoming introverted or extroverted,” said Agha Saeed,

national chairman of the American Muslim Task Force on Civil Rights and

Elections, an umbrella organization in Newark, Calif., created in 2003. “We

became extroverted.”

In some ways, new Muslim immigrants may be better off in the post-9/11 America

they encounter today, say Muslim leaders and academics: Islamic centers are more

organized, and resources like English instruction and free legal assistance are

more accessible.

But outside these newly organized mosques, life remains strained for many

Muslims.

To avoid taunts, women are often warned not to wear head scarves in public, as

was Rubab Razvi, 21, a Pakistani who arrived in Brooklyn nine months ago. (She

ignored the advice, even though people stare at her on the bus, she said.)

Muslims continue to endure long waits at airports, where they are often tagged

for questioning because of their names or dress.

To some longtime immigrants, the life embraced by newcomers will never compare

to the peaceful era that came before.

“They haven’t seen the America pre-9/11,” said Khwaja Mizan Hassan, 42, who left

Bangladesh 30 years ago. He rose to become the president of Jamaica Muslim

Center, a mosque in Queens, and has a comfortable job with the New York City

Department of Probation.

But after Sept. 11, he was stopped at Kennedy Airport because his name matched

another on a watch list.

A Drop, Then a Surge

Up to six million Muslims live in the United States, by some estimates. While

the Census Bureau and the Department of Homeland Security do not track religion,

both provide statistics on immigrants from predominantly Muslim countries. It is

presumed that many of these immigrants are Muslim, but people of other faiths,

such as Iraqi Chaldeans and Egyptian Copts, have also come in appreciable

numbers.

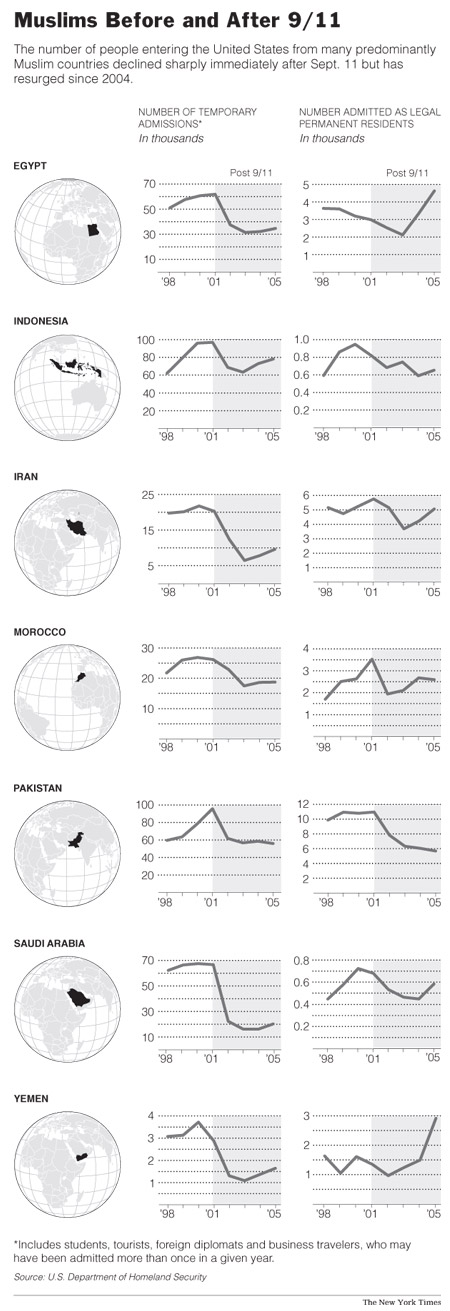

Immigration from these regions slowed considerably after Sept. 11. Fewer people

were issued green cards and nonimmigrant visas. By 2003, the number of

immigrants arriving from 22 Muslim countries had declined by more than a third.

For students, tourists and others from these countries who were designated as

nonimmigrants, the drop was even more dramatic, with total visits down by nearly

half.

The falloff affected immigrants from across the post-9/11 world as America

tightened its borders, but it was most pronounced among those moving here from

Pakistan, Morocco, Iran and other Muslim nations.

Several factors might explain the drop: more visa applications were rejected due

to heightened security procedures, said officials at the State Department and

Department of Homeland Security; and fewer people applied for visas.

But starting in 2004, the numbers rebounded. The tally of people coming to live

in the United States from Bangladesh, Turkey, Algeria and other Muslim countries

rose by 20 percent, according to an analysis of Census Bureau data.

The uptick was also notable among foreigners with nonimmigrant visas. More than

55,000 Indonesians, for instance, were issued those visas last year, compared

with roughly 36,000 in 2002.

The rise does not reflect relaxed security measures, but a higher number of visa

applications and greater efficiency in processing them, said Chris Bentley, a

spokesman for United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, part of

Homeland Security.

Like other immigrants, Muslims find their way to the United States in myriad

ways: they come as refugees, or as students and tourists who sometimes overstay

their welcome. Others arrive with immigrant visas secured by relatives here. A

lucky few win the green-card lottery.

Ahmed Youssef, 29, never thought he would be among the winners. But in 2003, Mr.

Youssef, who taught Arabic in Egypt, was one of 50,000 people randomly chosen

from 9.5 million applicants around the world.

As he prepared to leave Benha, a city north of Cairo, some friends asked him how

he could move to a country that is “killing people in Iraq and Afghanistan,” he

recalled. But others who had been to the United States encouraged him to go.

It was the same for Nora Elhainy, another lottery winner, who left Casablanca in

2004 to join her husband in Queens. “They think I am lucky because I am here,”

she said of her Moroccan friends.

When Mr. Youssef arrived in May 2005, he found work in Manhattan loading hot dog

carts from sunrise to sundown. He shared an apartment in Washington Heights with

other Egyptians, but for the first month, he never saw his neighborhood in

daylight.

“I joked to my roommates, ‘When am I going to see America?’ ” said Mr. Youssef,

a slight man with thinning black hair and an easy smile.

Only three months later, when he began selling hot dogs on Seventh Avenue, did

Mr. Youssef discover his new country.

He missed hearing the call to prayer, and thought nothing of unrolling his

prayer rug beside his cart until other vendors warned him against it. He could

be mistaken for an extremist, they told him.

Eventually, Mr. Youssef found a job as the secretary of the Islamic Center of

Jersey City. He plans to apply to a master’s program at Columbia University,

specializing in Arabic.

For now, he lives in a spare room above the mosque. Near his bed, he keeps a

daily log of his prayers. If he makes them on time, he writes “Correct” in

Arabic.

“I am much better off here than selling hot dogs,” he said.

Awash in American Flags

Nur Fatima landed in Midwood, Brooklyn, at a propitious time. Had she come three

years earlier, she would have seen a neighborhood in crisis.

Hundreds of Pakistani immigrants disappeared after being asked to register with

the government. Thirty shops closed along a stretch of Coney Island Avenue known

as Little Pakistan. The number of new Urdu-speaking students at the local

elementary school, Public School 217, dropped by half in the 2002-3 school year,

according to the New York City Department of Education.

But then Little Pakistan got organized. A local businessman, Moe Razvi,

converted a former antique store into a community center offering legal advice,

computer classes and English instruction. Local Muslim leaders began meeting

with federal agents to soothe relations.

The annual Pakistan Independence Day parade is now awash in American flags.

It is a transformation seen in Muslim immigrant communities around the nation.

“They have to prove that they are living here as Muslim Americans rather than

living as Pakistanis and Egyptians and other nationalities,” said Zahid H.

Bukhari, the director of the American Muslim Studies Program at Georgetown

University.

Ms. Fatima arrived in Brooklyn from Pakistan in March after her father, who has

lived here for six years, successfully petitioned for a green card on her

behalf. Her goal was to become an interpreter and eventually practice law. She

began by taking English classes at Mr. Razvi’s center, the Council of Peoples

Organization.

She has heard stories of the neighborhood’s former plight but sees a different

picture.

“This is a land of opportunity,” Ms. Fatima said. “There is equality for

everyone.”

Five days after she came to Brooklyn, Ms. Fatima removed her head scarf, which

she had been wearing since she was 10.

She began to change her thinking, she said: She liked living in a country where

people respected the privacy of others and did not interfere with their

religious or social choices.

“I came to the United States because I want to improve myself,” she said. “This

is a second birth for me.”

More

Muslims Arrive in U.S., After 9/11 Dip, NYT, 10.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/10/nyregion/10muslims.html?hp&ex=1157860800&en=a1703d031d2a4f73&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Boston Tests System Connecting Fingerprints

to Records of Immigration Violations

September 9, 2006

The New York Times

By ERIC LIPTON

WASHINGTON, Sept. 8 — Immigration officials

will automatically be notified anytime the local or state police do a federal

fingerprint check on a suspect who also happens to be wanted for serious

immigration violations, under a new system being tested in Boston.

The automated notification is part of a Department of Homeland Security program

that could expand the role that the local and state police nationwide play in

the immigration enforcement effort.

To federal officials, it is a natural next step as police forces have hundreds

of thousands of officers who routinely come into contact with illegal

immigrants, while Immigration and Customs Enforcement has a squad of only about

6,000 criminal investigators.

“We are giving more information to more people who can act on the information,”

said Robert A. Mocny, acting director of US-Visit, the Department of Homeland

Security program coordinating the effort. “It only makes sense.”

But some immigration and civil liberties advocates objected.

“Once the police become viewed as immigration agents, as opposed to simply

safety and law enforcement patrols, they will lose the cooperation and trust of

a significant portion of the communities they serve,” said Marshall Fitz,

director of advocacy at the American Immigration Lawyers Association. “That

ultimately undermines all of our security interest.”

Barry Steinhardt, director of the technology and liberty program at the American

Civil Liberties Union, said he was also concerned. The Homeland Security

Department’s records rely upon just two fingerprints, instead of 10, and are

therefore more subject to error, Mr. Steinhardt said, which could result in

someone’s being wrongly detained on immigration charges.

“It is an unreliable system being run by a barely competent agency,” Mr.

Steinhardt said.

The new program has started off in a relatively modest way. When the Boston

Police Department does a fingerprint check of federal criminal records for crime

suspects, it will also check a Homeland Security Department database of 420,000

people who have violated immigration laws. The federal list includes people who

have been previously deported from the United States or tried to enter but were

denied a visa.

If the police happen to stop one of those people, both the Boston Police

Department and Immigration and Customs Enforcement, a division of the Homeland

Security Department, will be notified. The department may then ask the Boston

police to hold the person for up to 48 hours, until the federal authorities can

take him into custody or otherwise begin deportation proceedings, an Immigration

and Customs Enforcement spokesman said.

Eventually, as more cities and states participate, the Homeland Security

Department intends to add nine million sets of fingerprints to the database to

include people with less serious immigration records, like someone caught trying

to cross the border from Mexico who then voluntarily returned home, Mr. Mocny

said.

The local and state police in many cities, including Boston, already routinely

contact Immigration and Customs Enforcement to see if suspects they have

detained might also be wanted on federal immigration violations. Federal

criminal databases already include some people wanted on felony immigration

violations.

But the immigration-related inquiries have previously been based on a names and

dates of birth, which may be forged. And the checks are not frequently done on

every arrest and fingerprint check, as is now the case in Boston.“You can’t hide

from the fingerprint,” Mr. Mocny said.

Mr. Fitz, of the immigration lawyers group, said he had no objection if the

fingerprints were checked for immigration violations only after an individual

had been charged with another crime.

His concern, he said, is that the local police might begin to submit these kinds

of requests routinely during traffic stops or patrols simply to determine if

someone was in the United States legally.

William M. Casey, deputy superintendent of the Boston police, said Boston did

not plan to take such a step.

“We are doing nothing differently than we were doing before last Sunday,” Mr.

Casey said. “We are enforcing the laws the Boston police always enforce.”

Mr. Mocny said the Homeland Security Department was already moving to a

10-fingerprint system to address the potential for fingerprint mismatches. He

added that he understood that this new program might provoke debate.

It is also unclear how much demand it will place on the federal immigration

enforcement authorities in detaining illegal immigrants and conducting

deportation proceedings.

That is why the project is being tested in Boston before being expanded

nationally over the next two years.

“Eventually,’’ Mr. Mocny said, “it will be all violators of all immigration

laws. But we are going to give this 22 months to cook to make sure that we are

getting it right.”

Boston Tests System Connecting Fingerprints to Records of Immigration

Violations, NYT, 9.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/09/us/09immig.html

In Bellwether District, G.O.P. Runs on Immigration

September 6, 2006

The New York Times

By CARL HULSE

AURORA, Colo. — It was not by chance that Republicans

brought their summer tour of hearings on illegal immigration to this growing

community just outside Denver.

Not only is Aurora bearing the costs of schooling and providing other services

for a significant population of illegal immigrants, it is in the heart of a

swing district and so is central to the intense battle for control of the House

of Representatives.

And while Congress is unlikely to enact major immigration legislation before

November, inaction does not make the issue any less potent in campaigning. In

fact, many Republicans, on the defensive here and around the country over the

war in Iraq, say they are finding that a hard-line immigration stance resonates

not just with conservatives, who have been disheartened on other fronts this

year, but also with a wide swath of voters in districts where control of the

House could be decided.

“Immigration is an issue that is really popping, “ said Dan Allen, a Republican

strategist. “It is an issue that independents are paying attention to as well.

It gets us talking about security and law and order.”

Leading Republicans, leery of a compromise on immigration, are encouraging their

candidates to keep the focus on border control, as in legislation passed by the

House, rather than accept a broader bill that would also clear a path for many

illegal immigrants to gain legal status. The latter approach, approved by the

Senate with overwhelming Democratic support and backed by the White House, makes

illegal immigration one of the issues on which Republicans face a tough choice

of standing by President Bush or taking their own path.

“The American people want a good illegal-immigration-reform bill,” said

Representative John A. Boehner of Ohio, the House majority leader, “not a

watered-down, pro-amnesty bill.”

Here in the Seventh District, the Republican push brought a Senate subcommittee

hearing the other day to explore the costs of illegal immigration. The

taxpayer-financed, ostensibly nonpartisan meeting took on the air of political

theater.

“They are here in this district with this topic attempting to drum up support in

a closely contested Congressional race,” fumed Lisa Duran, director of an

immigrant rights group.

If that was the tactic, it may have worked. The angry confrontation thrust the

session into the headlines, reminding residents that the issue remained a

leading one in the House race between Rick O’Donnell, the Republican nominee,

and Ed Perlmutter, the Democrat, who are running to fill a seat being vacated by

Representative Bob Beauprez, a Republican seeking the governorship.

The issue remains on voters’ minds “because people are trying to keep it on

their minds,” said Mr. Perlmutter, who accused Republicans of staging the

hearing for political gain.

Mr. Perlmutter, a former state legislator, is trying to navigate tough political

terrain by coming down hard for border enforcement while leaving the door open

for illegal immigrants to seek citizenship eventually. His opponent, a former

state higher education official, says such a position will not sell in Denver

suburbs characterized by unease that the nation has inadequately policed its

borders.

“I know the voters in my district are adamantly opposed to anything that smacks

of amnesty,” Mr. O’Donnell said.

Republicans went into this year determined to keep the midterm elections from

becoming a referendum on national issues and Mr. Bush, insisting that they would

run on local concerns instead. But in this district, as in most others with

tightly contested races around the country, the campaign is turning on the

overarching national issues.

On immigration, many Republicans, like Mr. O’Donnell, have put distance between

themselves and the Bush administration, emphasizing stronger border security and

ignoring or rejecting the president’s support for the broader legislation.

Similarly, on Iraq, Mr. O’Donnell is trying to find a middle ground that, though

basically supportive of Mr. Bush, allows the candidate to be critical of the

war’s management. Like the president, Mr. O’Donnell says that American troops

should not be withdrawn until Iraq is stabilized and that setting a deadline for

a pullout could lead to disaster. Yet he is trying to separate himself from the

administration’s handling of the war, saying that “we may need new leadership at

the Pentagon.”

Mr. Perlmutter has tried to put his Republican opponent on the defensive over a

third issue, embryonic stem cell research. He made it the subject of his first

television commercial, pointing to the potential benefits for a daughter of his

who has epilepsy. “It is personal to me,” he said.

Until recently, Mr. O’Donnell sided with Mr. Bush in opposing expanded federal

financing of such research. Now he says the effort should move forward, given a

scientific advance, reported last month, that may allow stem cells to be

obtained from embryos without destroying them. He rejects Mr. Perlmutter’s

assertion of a flip-flop on the research, which both men say is popular with

voters. “I didn’t move,” he said, “the research did.”

But here as elsewhere, Democrats too are still trying to calibrate their

positions on the big issues, a reflection of what the two parties agree is a

fluid political situation. Even as they try to tap into the antiwar sentiment in

their liberal base, many Democrats in swing districts, like Mr. Perlmutter, are

articulating positions on Iraq that they hope will insulate them from the “cut

and run“ charges being leveled by Republicans. So Mr. Perlmutter paints his

opponent as an adherent of what he portrays as Mr. Bush’s policy: “stay the

course until we run aground.”

Yet he does not endorse a quick exit, calling instead for the beginning of a

phaseout of the troops, tied to a multinational reconstruction effort, with

American forces out completely by the spring of 2008.

“We will have been in Iraq for five years by that time,” he said.

Certainly the topics dominating the campaign landscape have proved challenging.

“The war and the issue of immigration are sufficiently complicated that both

parties are having a hard time getting a real clear, laserlike fix on the whole

thing,” said John Straayer, a political science professor at Colorado State

University.

Just a few weeks ago politicians and analysts suspected that immigration had

lost its political punch in Colorado, after the legislature enacted a tough

immigration overhaul including tighter identification rules for those seeking

state government services.

But the issue refuses to die. Mr. O’Donnell said it was the subject most

frequently raised with him by residents. At the hearing here the other day,

presided over by Senator Wayne Allard, a Colorado Republican, more than 200

people showed up even though it had promised to be a fairly dry look at the

fiscal effects of illegal immigration.

On the street outside, the emotions surrounding the debate were on vivid

display. Advocates on both sides chanted slogans, sought to outshout each other

and displayed signs like “No Human Being Is Illegal” and “Stop the Invasion.”

Gov. Bill Owens, a Republican elected eight years ago, testified on illegal

immigration’s costs to the state, saying the influx was not a driving issue when

he first took office but had since risen to the top of Colorado’s concerns. “The

state did take some important steps,” Mr. Owens said of the recently enacted

immigration measure, “because of weaknesses in federal law. But there is a lot

more that needs to be done.”

In an interview, Mr. O’Donnell accused his party’s leader, Mr. Bush, of being

soft on illegal immigration. “I don’t know why the administration hasn’t

enforced the laws,” he said, adding that his objective was border security.

Mr. Perlmutter said he shared that goal. But he said the government also had to

deal with the millions of illegal residents already in the United States,

enabling some to “earn your citizenship if you are learning English, paying

taxes, haven’t committed a crime and have a job,” as the Senate bill provides.

He blames Republicans for allowing the problem to fester.

Hoping to throw Mr. O’Donnell off stride, the Perlmutter campaign also

resurrected an opinion article he wrote in 2004 suggesting that male high school

seniors be required to perform six months of community service, with the option

of assisting in border security. Mr. Perlmutter equated that plan to a draft;

Mr. O’Donnell said he had simply been endorsing a call for community service

that many civic leaders have backed.

As they fine-tune their messages, the two men agree on at least one thing: this

evenly split district will be a bellwether in November.

“The issues that end up driving this campaign,” Mr. O’Donnell told a Rotary Club

luncheon in nearby Commerce City, “are going to set the tone for this country.”

In Bellwether

District, G.O.P. Runs on Immigration, NYT, 6.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/06/washington/06colorado.html?hp&ex=1157601600&en=12d6490dbd8cec9b&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Rallies Sound the Drumbeat on Immigration

September 5, 2006

The New York Times

By SHIA KAPOS and PAUL GIBLIN

BATAVIA, Ill., Sept. 4 — Spirited groups of

immigrant rights supporters rallied in Illinois and Arizona on Monday in marches

intended to keep the drumbeat going for changes in immigration law.

In both places, counterdemonstrators heckled from the sidelines and called on

the federal government to enforce its border laws.

Organizers of a rally in Phoenix, outside Arizona’s copper-domed Capitol,

estimated their numbers at 4,000, though the police said the event drew about

1,000 people.

In Batavia, a flag-waving crowd, estimated by the police at about 2,500, chanted

“Sí, se puede” — “Yes, we can” — and converged on the district office of Speaker

J. Dennis Hastert. In a counterrally sponsored by the Chicago Minuteman Project,

some 200 men, women and a few children jeered the larger crowd.

Neither Mr. Hastert nor his staff was on hand, and he could not be reached for

comment.

Organizers hoped to pressure Mr. Hastert to push legislation favorable to

immigrants through Congress.

“We’re here because we need to keep this issue alive,” said Jorge Mujica, 50, a

Mexican immigrant who helped organize the rally and who lives in Berwyn, Ill.

“We want to show that we didn’t disappear after May 1,” Mr. Mujica said,

referring to the hundreds of thousands who demonstrated nationwide that day on

the issue. “We’re still marching. We’re not going away.”

Alfredo Gutierrez, at the rally in Phoenix, said that he was disappointed it had

not attracted more marchers but that he thought the debate had changed in recent

months. Immigrant rights activists who were initially so optimistic have begun

to lose hope, he said.

“That feeling that something would be accomplished has diminished almost daily

with every report of every negative thing that goes on with Congress,” Mr.

Gutierrez said.

The Arizona chapter of the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now

set up three tents, at which volunteers registered people to vote and

distributed postcards urging members of Arizona’s Congressional delegation to

support a path for citizenship for illegal immigrants. Counterprotesters

gathered behind the main stage and shouted at the crowd, but security personnel

and the police generally kept the sides apart.

Fran Garrett, a volunteer with the anti-immigration group United for a Sovereign

America, based in Phoenix, said she was fed up with the authorities who refused

to arrest and deport illegal immigrants.

“They try to get the message out that they’re here to do jobs and all that,” Ms.

Garrett said. “That’s not true. They are here to take over eight states of the

United States, and they are going to do it by sheer numbers alone, when they get

enough people where they are the majority in a state.”

In Batavia, 30 Chinese-Americans joined the mostly Latino crowd. One of them,

Man Li Wu, said through an interpreter that she had a daughter in China who had

tried for eight years to enter the United States.

“I’m 70 and I don’t know how long I’ll be able to wait,” she said. “I want to

see my grandchildren.” Members of the Chicago Minutemen say that living in the

United States is a privilege and should not be an easy process.

“Immigration laws aren’t broken,” said Evert Evertsen, 61, from Harvard, Ill.

“The problem is they’re just not being enforced.”

Rallies Sound the Drumbeat on Immigration, NYT, 5.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/05/washington/05rally.html?_r=1&oref=slogin

Stolen Lives

Some ID Theft Is Not for Profit, but to Get

a Job

September 4, 2006

The New York Times

By JOHN LELAND

Camber Lybbert thought it was a mistake when

her bank told her that her daughter’s Social Security number was on its files

for two credit cards and two auto loans, with an outstanding balance of more

than $25,000. Her daughter is 3 years old.

For Ms. Lybbert and her husband, Tyson, the call was the beginning of a

five-month scramble trying to clear up their daughter’s credit history. As it

turned out, an illegal immigrant named Jose Tinoco was using their daughter’s

stolen Social Security number, not in pursuit of a financial crime, but to get a

job.

“From what I’ve picked up, he wasn’t using it maliciously,” said Ms. Lybbert,

who lives in Draper, Utah. “He was using it to have a job, to get a car, provide

for his family. My husband’s like, ‘Don’t you feel bad, you’ve ruined this guy’s

life?’ But at the same time, he’s ruined the innocence of her Social Security

number because when she goes to apply for loans, she’s going to have this

history.”

Though most people think of identity theft as a financial crime, one of the most

common forms involves illegal immigrants using fraudulent Social Security

numbers to conduct their daily lives. With tacit acceptance from some employers

and poor coordination among government agencies, this practice provides the

backbone of some low-wage businesses and a boon to the Social Security trust

fund. In the 1990’s, such mismatches accounted for around $20 billion in Social

Security taxes paid.

“It’s clear that it is a different intent or purpose than trying to get

someone’s MasterCard and charge it up, knowing they’re going to get the bill,”

said Richard Hamp, an assistant attorney general in Utah. “But it has some

similarities. It goes on the other person’s credit record. Illegals are filing

for bankruptcy, using someone else’s number. I had one 78-year-old with three

defaults on houses she never owned.”

The Federal Trade Commission, which estimates that 10 million Americans have

their identities stolen each year, does not distinguish between people who steal

Social Security numbers so they can work and those who are out to steal money.

Illegal immigrants make up nearly one of every 20 workers in America, according

to estimates by the Pew Hispanic Center, and most are working under fraudulent

Social Security numbers, which can be bought in any immigrant community or in

Mexico.

In Caldwell, Idaho, a woman named Maria is just such a worker.

Maria, 51, came from Mexico City illegally six years ago and bought a

counterfeit green card and Social Security card through a friend for $180. She

earns $6.50 an hour, and like most of the seven million working illegal

immigrants in the United States, she pays income tax and Social Security tax.

She agreed to be interviewed on the condition that her last name not be used.

“We know we’ll never get it back,” Maria said of the Social Security payments.

“It’s unfortunate, but it’s a given.”

Like most victims of identity theft, the Lybberts did not lose any money in the

long run, but Ms. Lybbert estimates that for four or five months she spent 30

hours or more a week making telephone calls, feeling passed from one agency or

voice-mail system to another: the Social Security Administration, the state

attorney general, the three bureaus that issue credit ratings and police

departments in two cities.

“Everyone I talked to handed me off to someone else, saying that’s not our

department, call this number,” she said. “I was being led in a circle.”

The Social Security Administration each year receives eight million to nine

million earnings reports from the Internal Revenue Service filed under names

that do not match the Social Security numbers. Some are from workers whose

employers botched their personnel forms or from women who recently changed their

names after marriage. Others are from people using a Social Security number that

is not their own.

“It’s basically a subsidy from migrant workers to the aggregate of American

taxpayers,” said Douglas S. Massey, a professor of sociology at Princeton who

studies Mexican migration.

While no one knows how many of these mismatches are illegal immigrants, a

Government Accountability Office study found that employers with the most

mismatches were concentrated in industries that hire a lot of illegal

immigrants, including agriculture, construction and food services.

“Right now, employers are not motivated to care if their workers give them false

Social Security numbers,” said Barbara D. Bovbjerg, the office’s director of

education, work force and income security issues. “The I.R.S. has made exactly

zero penalties for reporting mismatches.”

The Social Security Administration is legally banned from sharing information

with immigration or law enforcement agencies, or from telling the rightful

owners of Social Security numbers that someone else is working under their

number, said Mark Hinkle, an agency spokesman.

The rightful owner of a stolen number does not get the benefits accrued under

its false use.

Ms. Bovbjerg’s office and others have called for better cooperation among the

Social Security Administration, the Internal Revenue Service and the Department

of Homeland Security to prosecute workers who use false Social Security numbers

and the companies that hire them.

“We’ve had this ridiculous situation where, theoretically, this information

could be shared and we could identify these people and repair the situation,”

said Marti Dinerstein, a fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies, a

nonprofit organization that supports tighter restrictions on immigration.

“Falsely using a Social Security number is a felony. Our own federal agencies

are working against those laws. The I.R.S. says privacy laws prevent them from

sharing information. So we know who the guilty employers are. The I.R.S. knows

who the guilty employees are. And nothing’s being done about it.”

In 2000, using data from the Social Security Administration, the Utah attorney

general’s office found that the Social Security numbers of 132,000 people in the

state were being used by other people, far more than the state could prosecute.

This use caused problems even when the person using the number led a financially

responsible life, said Mr. Hamp, the assistant attorney general. “I’ve had

families denied public assistance for their children or disability payments,” he

said, “because records show somebody is working in their Social Security

number.”

Scott Smith of Ogden, Utah, discovered that someone was using his daughter

Bailey’s Social Security number when he applied for public health insurance for

her. Mr. Smith, who owns four shredders, is by his own description “real

paranoid” about identity theft. “We even take the shreddings and put them in

different garbage cans,” he said.

Like Ms. Lybbert, he has mixed feelings about what happened next.

“All that was happening was that the illegal alien who had gotten the card had

gotten a job at a Sizzler steakhouse in Provo and was paying her bills and doing

a good job,” he said. “My opinion was, Hey, we’ve got someone hard-working who’s

come from Mexico, who just wants to get a leg up — give her Bailey’s Social

Security number and issue us a new one. Let her stay in the country. But they

arrested her. I actually feel bad about her being deported.”

In immigrant communities, most counterfeiters invent Social Security numbers at

random, choosing only the first three digits to signal the card’s state of

origin, prosecutors and investigators say.

When the numbers belong to children, the problems can start when they turn 18,

said Jay Foley, a founder and director of the Identity Theft Resource Center in

San Diego, a nonprofit organization that helps victims and proposes legislation.

“Now the child goes for student loans or jobs, and the companies say, ‘You’ve

got a problem of bad credit. We aren’t going to touch you.’ ”

Most affected, Mr. Foley said, are foster children who are suddenly independent

at 18.

His organization has advocated that the Social Security Administration maintain

a data file of children’s Social Security numbers and birth dates that credit

bureaus can check before issuing credit. “They can check the list and say, ‘Mr.

Businessman, why are you starting a credit line for a 3-year-old?’ ”

Marco, 25, a restaurant worker in New York City, bought his Social Security card

for $40 on Roosevelt Avenue in Queens. Now he helps other new arrivals find

false identification and restaurant work. He says his employers usually know

that his card is fake and use that to their advantage. “It’s easier for them to

fire you when business is slow,” said Marco, who did not want his last name

revealed.

As Marco pays income and Social Security taxes, he hopes to gain amnesty someday

and get credit for his contributions to the retirement fund, which is possible

but difficult under current law. But most in his situation do not think about

getting the money back, said Wayne Cornelius, director of the Center for

Comparative Immigration Studies at the University of California, San Diego. Most

retire to their home countries, where the cost of living is lower and many own

property, he said.

For Mr. Smith and his daughter in Utah, the crime was almost victimless. He

spent a day photocopying documents for the credit bureaus but did not lose any

money or run into threats to his daughter’s credit.

But now that her number is out there, he said, there is no way to tell how many

times it has been sold, or when someone will use it next.

“So before I say I’m not upset about it, I don’t know the full story,” he said.

“Other people could be racking up credit cards. The only recourse we have is to

go to the credit agencies and check every several months. It’s a lot of

paperwork to do to have them say, ‘Nope, no record.’ ”

Some

ID Theft Is Not for Profit, but to Get a Job, NYT, 4.9.2006,

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/04/us/04theft.html?hp&ex=1157428800&en=17a41cfaa66a3db5&ei=5094&partner=homepage

Compensation Heightens Unease of 9/11

Relatives in U.S. Illegally

September 3, 2006

The New York Times

By CARA BUCKLEY

One widow has more than $2 million but walks

or rides the bus everywhere, terrified of drawing attention. Another millionaire

widow stopped going to 9/11 support groups because she feared that families of

police officers and firefighters might betray her. A widower has enough money to

start a business building houses, but cannot buy himself a home.

All three lost a husband or a wife when the World Trade Center collapsed. Like

thousands of others, they were beneficiaries of the federal Sept. 11 Victim

Compensation Fund, which awarded millions of dollars to families whose loved

ones died in the attacks.

But a secret sets these three apart. Like their spouses who died, each is in the

country illegally. Even though the government compensated them richly for their

losses, making them wealthier than they ever dreamed, the money did not change

their immigration status. They fear they could be deported any day.

Five years after the terrorist attacks, these people are living with

extraordinary contradictions.

Long accustomed to stashing dollar bills in coffee cans, they became

millionaires overnight. But because they do not have Social Security numbers or

work visas, they cannot get mortgages or driver’s licenses. They say they have

spent little of the money, afraid of attracting notice.

Their spouses were labeled heroes, their names emblazoned on placards ringing

ground zero. But none of these three, still living in or near New York City,

feel they can publicly identify themselves.

“I can’t dream very high, because I have no papers,” said one widow from

Ecuador, who, like the others, agreed to be interviewed on the condition that

she not be named. “You’re always afraid of exposure. It’s a horrible feeling.

But I don’t want to go back to my country. I know my husband’s spirit is here.”

After Congress created the victims’ fund, promising payouts in return for an

agreement not to sue the airlines or other interests, the officials who drafted

the fund’s rules explicitly stated that foreigners and illegal immigrants would

be eligible. And immigration authorities announced that they would not use

information provided to the fund to track people down.

But the families who received money could still face deportation if their

identities come to light in some other way, their lawyers say.

A spokesman for Immigration and Customs Enforcement in New York, Mark Thorn,

said the agency could not comment on specific cases, but confirmed it was not

focusing on the families. Still, he added, “generally speaking, anyone who is in

this country illegally is vulnerable to removal.”

Legislation before Congress would grant green cards to the illegal immigrants

who received money. But the measure, attached to the Senate’s immigration bill,

is deadlocked with the entire package.

From the start, many immigrants were suspicious of the fund.

“They were these modest, poor, fearful people,” said Kenneth R. Feinberg, the

fund’s special master, who determined the awards. “They were afraid they’d be

punished.”

In the end, 11 awards went to the survivors of illegal immigrants. All those

victims had worked at the restaurant Windows on the World. Although they had

earned modest wages, many were upwardly mobile and supported relatives back

home, factors that increased the payouts. Their awards ranged from $875,000 to

$4.1 million.

But their lawyers still worried: That their clients would become marks for

hustlers. That relatives, sustained by wire transfers and living in unstable

countries, would be kidnapped for ransom.

Details about the 11 families are sketchy. At least three lived abroad at the

time of the attack and remain there. At least three were here in New York on

9/11 and still live here with their children in modest apartments.

They could return to their native lands with their money, but feel tethered

here, unwilling to leave the country where their spouses worked and died, and

determined to give their children a chance to grow up here.

“I have half my life here,” one widow said. “And my husband is here.”

When the widow from Ecuador first heard about the fund, she thought it might be

a trap to catch immigrants like her.

She and her husband moved to Queens in 1992, paying smugglers $11,000 to help

them cross the border. But now her husband, a supply-room manager, was dead and

she was alone with their son, who had joined them later. She could no longer

afford the rent on their cramped basement apartment, where sewage leached

through floors, or her son’s asthma spray.

The union at Windows on the World arranged for families to meet with pro-bono

lawyers. One lawyer, Debra Steinberg, convinced her that Mr. Feinberg, the

fund’s administrator, was sincere.

But the woman was petrified. Mr. Feinberg worked for the government, after all.

When she told him her story at a hearing in April 2003, her voice quavered.

“How could he understand how I was feeling, how I was screaming from the

inside?” she said she wondered. “That we need help, and we’re alone. That we

don’t belong here, but that I don’t want to go back to my country. That I’m

already part of this one, because my husband is here.”

Mr. Feinberg awarded her roughly $1.6 million.

The sum frightened her. She had grown up in a mountain town where dinner often

consisted of rice and half an egg. “I was praying, ‘Please, God, don’t let me

change, let me stay myself,’ ” she said.

The woman, 38, tried to make peace with the windfall by thinking of the money as

her husband’s gift to their son. With help, she put it into conservative

investments that she could tap if forced back to Ecuador. She has lived off the

interest, she says.

And she has continued to live modestly, renting a two-bedroom apartment in East

Elmhurst, Queens, for $1,200 a month. Her splurge was a bedroom set for her son.

But the money did change her life. She is still a warm woman with laughing brown

eyes, but she has grown withdrawn.

She is afraid to tell neighbors she is a 9/11 widow, fearing questions about her

immigration status. She yearns for work to fill her days, but has no visa. She

stopped seeing old friends who made snide remarks about her sudden wealth. Even

9/11 support groups made her feel unsafe, because they were filled with spouses

of dead police officers.

“I’d rather be alone,” she said softly.

Her son, 17, is a senior at a private school in Manhattan, his tuition paid by a

private foundation. A gifted photographer, he dreams of studying design, but the

colleges he is interested in require Social Security numbers.

He says he cannot imagine moving to Ecuador, which he left at age 5.

“I have no idea what I’ll do,” he said, as a trailer for the movie “World Trade

Center” flashed across their television screen. He took a shaky breath and said,

“My history is here.”

For the second widow, school days are the hardest. The Mexican woman with the

soulful eyes and a sweep of dark hair tightens her fingers around her 9-year-old

son’s hand and boards the public bus. Only 4-foot-7, she almost disappears into

the seat. But she feels like a beacon sending off warning signals.

Her son was 4 when his father, a grill cook, died on 9/11. The Windows of Hope

Family Relief Fund, which helps families of the restaurant workers, pays the

boy’s tuition at a private elementary school in Manhattan. But this woman lives

outside Newark and has no car. So she takes her son to and from school, a daily

commute totaling six hours.

She finds the journey harrowing. Security is tighter now at bridges and tunnels.

“I never know if they’re going to get me,” said the woman, 30, who recently had

a baby girl with her new companion.

It is hard to fathom that this woman has about $2.2 million, trusted financial

advisers and a lawyer, Ms. Steinberg. Yet there are things that a fortune cannot

buy. She has the cash to buy a house outright, but fears that if deported, she

could lose any property here. She struggled to find an apartment, because most

landlords demand a Social Security number. She cannot get a driver’s license, so

she carries groceries and laundry for blocks, her baby in tow.

Immigration officials have caught her before. In 2000, she says, she and her

husband were intercepted as they were returning from their wedding in Mexico.