|

History > 2007 > USA > Police (I)

1 - A view from a

Children’s Aid Society surveillance video

released by the New York Police

Department

shows part of a gunfight in Greenwich Village Wednesday night

that left four

people dead.

Above, the gunman runs up the sidewalk,

to the right, behind the dark volvo.

2 - The gunman

(light-colored shirt)

runs across the street toward an auxiliary police officer

who is trying to duck behind a car.

3 - The gunman closes in

on the officer.

4 -

The gunman shoots the

officer.

5 -

The gunman runs from the scene.

6 -

The gunman crosses back over the street

and is shot at by another officer

approaching the scene.

7 -

Police officers rush to the fallen auxiliary officer.

8 -

Officers carry

the fatally wounded officer to their car

to rush him to the hospital.

NYPD

Lives Intersect Violently

on a Busy City Street NYT

16.3.2007

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/16/nyregion/16cops.html?hp

Cops: 'Gin and tonic bandit'

skipped out on same meal

5 weeks

straight

30.3.2007

AP

USA Today

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. (AP) — A scofflaw who came to be known as the gin and tonic

bandit went to the same restaurant each Wednesday, ordered two drinks and a

rib-eye steak, then skipped out on his $25.96 bill.

His dining, drinking and dashing days may be over.

Police arrested the man on preliminary charges of theft and resisting law

enforcement. He was being held early Friday at the Monroe County Jail on $2,000

bond, authorities said.

Each Wednesday night for four weeks running, the same man came into the same

O'Charley's restaurant and ordered the two drinks and the steak, restaurant

manager Teresa Tolbert told police.

At the end of each meal, the wait staff would present him with his bill for

$25.96, and he would excuse himself to use the restroom, then skip out without

paying.

The man appeared a fifth time Wednesday night, but the restaurant was ready for

him, police said.

When his server presented the bill, he again claimed he needed to use the

bathroom. But when he walked out of the restaurant, four employees were waiting

for him. They confronted him about the unpaid bill, which he offered to pay with

a check, police said.

After Tolbert told him the restaurant didn't accept checks, the man "got nervous

and ran," according to the police report.

Officer Randy Gehlhausen caught up with the man as he was trying to open his car

door. The diner struggled with Gehlhausen, who wrestled him to the ground and

handcuffed him.

Cops: 'Gin and tonic

bandit' skipped out on same meal 5 weeks straight, UT, 30.3.2007,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/offbeat/2007-03-30-gin-tonic-bandit_N.htm

4 Police Officers Charged in Assault

March 27, 2007

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Filed at 2:27 p.m. ET

The New York Times

RIVERHEAD, N.Y. (AP) -- The acting police chief and three officers in a small

resort town on Fire Island were indicted Tuesday in the beating of a vacationer

who had been picked up for littering.

The victim was beaten so severely he suffered severe internal injuries,

including a ruptured bladder that required 10 days in a hospital, Assistant

District Attorney Bob Biancavilla said.

Acting Chief George Hesse pleaded not guilty Tuesday to first-degree assault,

gang assault and unlawful imprisonment in the August 2005 beating of tourist

Samuel Gilberd, a software executive from New York City.

''It was a police department gone wild,'' Suffolk County District Attorney

Thomas Spota told a news conference afterward. ''There was no control at all.''

They ''acted as thugs in police uniforms,'' he said.

Hesse attorney William Keahon said the indictment ''means nothing.''

''The presumption is my client is innocent,'' he said.

Hesse posted $100,000 bail.

The three other defendants were charged with unlawful imprisonment, reckless

endangerment and hindering prosecution. Officers Paul Carollo, Arnold Hardman,

and William Emburey are accused of filing a false report about the incident and

failing to get prompt medical attention for the victim. Each posted $10,000

bail.

All four defendants, who displayed no visible emotion, were ordered to return to

court April 20.

Emburey's lawyer, John Ray, said the incident occurred on his client's first

night on the job. He said Emburey had nothing to do with the allegations and was

charged only because the it occurred on his shift.

A week after the alleged beating, Gilberd was charged with disorderly conduct

and resisting arrest, allegations the district attorney subsequently dismissed.

Gilberd has filed a $22 million federal lawsuit against the village and its

police.

Ocean Beach is a popular tourist destination whose population swells from 138

year-round residents to more than 6,000 summer renters and day-trippers. The

village is nicknamed the ''Land of No'' because of odd ordinances such as a ban

on eating cookies on public walkways.

Ocean Beach Mayor Joseph Loeffler declined to comment.

The Ocean Beach police department, which has 2 full-time members and 24

part-time members, had been the subject of a county grand jury probe since

December.

Last week, five former police officers claimed they were wrongfully fired by

Hesse, who they said associated with a drug dealer, had sex in department

headquarters and covered up cases of brutality. In an interview with Newsday,

Hesse would not say why he fired the five officers.

Doug Wigdor, a former prosecutor who is representing the five officers in a

wrongful-termination lawsuit, claimed Hesse was ''running the police department

like a fraternity house.''

Village and police officials have declined to comment on the lawsuit. The

lawsuit filed in U.S. District Court seeks millions in damages -- an exact

amount will be determined at trial -- and the restoration of their jobs.

At the time, the officers said they were targeted by the acting chief over fears

they were cooperating with the Suffolk County inquiry into corruption in the

department. Their lawyer said they were cooperating now that they had been

fired.

4 Police Officers

Charged in Assault, NYT, 27.3.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/us/AP-Ocean-Beach-Police.html

Auxiliary Officers

to Get Bullet-Resistant Vests

March 27, 2007

The New York Times

By SEWELL CHAN

New York City will begin providing bullet-resistant vests to its 4,800

auxiliary police officers, Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg announced today at a news

conference in Greenwich Village, where two auxiliary officers were fatally shot

by a gunman on the night of March 14.

The decision to buy the vests for the auxiliary officers — unpaid volunteers who

are unarmed but wear uniforms identical to those of regular officers — comes

less than two weeks after two auxiliary officers, Nicholas T. Pekearo, 28, and

Yevgeniy Marshalik, 19, were shot to death.

They had followed and confronted a gunman, David R. Garvin, who moments earlier

had fatally shot a pizzeria worker. Mr. Garvin dropped a bag containing a loaded

firearm and ammunition, but minutes later, he came back toward Officers Pekearo

and Marshalik and shot them both. Only a half-dozen auxiliary officers have been

slain in the line of duty in the half-century that the all-volunteer force has

existed.

The city will spend $3.3 million on the vests, and will take nine months to

outfit the entire force. The vests will be Level 3A — meaning they are supposed

to resist a 9-millimeter of 44 Magnum bullets. The vests are the same as those

provided to regular police officers; they were recently redesigned after the

slaying of an officer, Dillon H. Stewart, who was fatally shot last November

while pursuing a driver who ran a red light in Brooklyn. On patrol, he drew up

alongside the suspect’s car and the gunman fired five shots, striking Officer

Stewart in the heart. Though mortally wounded, he kept driving for blocks in

pursuit of the gunman, before collapsing.

Mayor Bloomberg made the announcement around noon today at the Sixth Precinct,

where Officer Pekearo, an aspiring writer, and Officer Marshalik, a sophomore at

New York University, were both based.

Numerous elected officials — including several members of Congress and members

of the City Council — had called for the city to furnish bullet-resistant vests

to auxiliary officers. As recently as last week, Police Commissioner Raymond W.

Kelly was noncommittal when asked about the idea, saying he was concerned about

cost and logistical issues. The mayor has set up a committee to examine a range

of issues involving auxiliary officers and how they can be better protected.

Auxiliary Officers to

Get Bullet-Resistant Vests, NYT, 27.3.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/27/nyregion/27cnd-mayor.html

City Police Spied Broadly

Before G.O.P. Convention

March 25, 2007

The New York Times

By JIM DWYER

For at least a year before the 2004 Republican National Convention, teams of

undercover New York City police officers traveled to cities across the country,

Canada and Europe to conduct covert observations of people who planned to

protest at the convention, according to police records and interviews.

From Albuquerque to Montreal, San Francisco to Miami, undercover New York police

officers attended meetings of political groups, posing as sympathizers or fellow

activists, the records show.

They made friends, shared meals, swapped e-mail messages and then filed daily

reports with the department’s Intelligence Division. Other investigators mined

Internet sites and chat rooms.

From these operations, run by the department’s “R.N.C. Intelligence Squad,” the

police identified a handful of groups and individuals who expressed interest in

creating havoc during the convention, as well as some who used Web sites to urge

or predict violence.

But potential troublemakers were hardly the only ones to end up in the files. In

hundreds of reports stamped “N.Y.P.D. Secret,” the Intelligence Division

chronicled the views and plans of people who had no apparent intention of

breaking the law, the records show.

These included members of street theater companies, church groups and antiwar

organizations, as well as environmentalists and people opposed to the death

penalty, globalization and other government policies. Three New York City

elected officials were cited in the reports.

In at least some cases, intelligence on what appeared to be lawful activity was

shared with police departments in other cities. A police report on an

organization of artists called Bands Against Bush noted that the group was

planning concerts on Oct. 11, 2003, in New York, Washington, Seattle, San

Francisco and Boston. Between musical sets, the report said, there would be

political speeches and videos.

“Activists are showing a well-organized network made up of anti-Bush sentiment;

the mixing of music and political rhetoric indicates sophisticated organizing

skills with a specific agenda,” said the report, dated Oct. 9, 2003. “Police

departments in above listed areas have been contacted regarding this event.”

Police records indicate that in addition to sharing information with other

police departments, New York undercover officers were active themselves in at

least 15 places outside New York — including California, Connecticut, Florida,

Georgia, Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan, Montreal, New Hampshire, New Mexico,

Oregon, Tennessee, Texas and Washington, D.C. — and in Europe.

The operation was mounted in 2003 after the Police Department, invoking the

fresh horrors of the World Trade Center attack and the prospect of future

terrorism, won greater authority from a federal judge to investigate political

organizations for criminal activity.

To date, as the boundaries of the department’s expanded powers continue to be

debated, police officials have provided only glimpses of its

intelligence-gathering.

Now, the broad outlines of the pre-convention operations are emerging from

records in federal lawsuits that were brought over mass arrests made during the

convention, and in greater detail from still-secret reports reviewed by The New

York Times. These include a sample of raw intelligence documents and of summary

digests of observations from both the field and the department’s

cyberintelligence unit.

Paul J. Browne, the chief spokesman for the Police Department, confirmed that

the operation had been wide-ranging, and said it had been an essential part of

the preparations for the huge crowds that came to the city during the

convention.

“Detectives collected information both in-state and out-of-state to learn in

advance what was coming our way,” Mr. Browne said. When the detectives went out

of town, he said, the department usually alerted the local authorities by

telephone or in person.

Under a United States Supreme Court ruling, undercover surveillance of political

groups is generally legal, but the police in New York — like those in many other

big cities — have operated under special limits as a result of class-action

lawsuits filed over police monitoring of civil rights and antiwar groups during

the 1960s. The limits in New York are known as the Handschu guidelines, after

the lead plaintiff, Barbara Handschu.

“All our activities were legal and were subject in advance to Handschu review,”

Mr. Browne said.

Before monitoring political activity, the police must have “some indication of

unlawful activity on the part of the individual or organization to be

investigated,” United States District Court Judge Charles S. Haight Jr. said in

a ruling last month.

Christopher Dunn, the associate legal director of the New York Civil Liberties

Union, which represents seven of the 1,806 people arrested during the

convention, said the Police Department stepped beyond the law in its covert

surveillance program.

“The police have no authority to spy on lawful political activity, and this

wide-ranging N.Y.P.D. program was wrong and illegal,” Mr. Dunn said. “In the

coming weeks, the city will be required to disclose to us many more details

about its preconvention surveillance of groups and activists, and many will be

shocked by the breadth of the Police Department’s political surveillance

operation.”

The Police Department said those complaints were overblown.

On Wednesday, lawyers for the plaintiffs in the convention lawsuits are

scheduled to begin depositions of David Cohen, the deputy police commissioner

for intelligence. Mr. Cohen, a former senior official at the Central

Intelligence Agency, was “central to the N.Y.P.D.’s efforts to collect

intelligence information prior to the R.N.C.,” Gerald C. Smith, an assistant

corporation counsel with the city Law Department, said in a federal court

filing.

Balancing Safety and Surveillance

For nearly four decades, the city, civil liberties lawyers and the Police

Department have fought in federal court over how to balance public safety, free

speech and the penetrating but potentially disruptive force of police

surveillance.

After the Sept. 11 attacks, Raymond W. Kelly, who became police commissioner in

January 2002, “took the position that the N.Y.P.D. could no longer rely on the

federal government alone, and that the department had to build an intelligence

capacity worthy of the name,” Mr. Browne said.

Mr. Cohen contended that surveillance of domestic political activities was

essential to fighting terrorism. “Given the range of activities that may be

engaged in by the members of a sleeper cell in the long period of preparation

for an act of terror, the entire resources of the N.Y.P.D. must be available to

conduct investigations into political activity and intelligence-related issues,”

Mr. Cohen wrote in an affidavit dated Sept. 12, 2002.

In February 2003, the Police Department, with Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg’s

support, was given broad new authority by Judge Haight to conduct such

monitoring. However, a senior police official must still determine that there is

some indication of illegal activity before an inquiry is begun.

An investigation by the Intelligence Division led to the arrest —

coincidentally, three days before the convention — of a man who spoke about

bombing the Herald Square subway station. In another initiative, detectives were

stationed in Europe and the Middle East to quickly funnel information back to

New York.

When the city was designated in February 2003 as the site of the 2004 Republican

National Convention, the department had security worries — in particular about

the possibility of a truck bomb attack near Madison Square Garden, where events

would be held — and logistical concerns about managing huge crowds, Mr. Browne

said.

“We also prepared to contend with a relatively small group of self-described

anarchists who vowed to prevent delegates from participating in the convention

or otherwise disrupt the convention by various means, including vandalism,” Mr.

Browne said. “Our goal was to safeguard delegates, demonstrators and the general

public alike.”

In its preparations, the department applied the intelligence resources that had

just been strengthened for fighting terrorism to an entirely different task:

collecting information on people participating in political protests.

In the records reviewed by The Times, some of the police intelligence concerned

people and groups bent on causing trouble, but the bulk of the reports covered

the plans and views of people with no obvious intention of breaking the law.

By searching the Internet, investigators identified groups that were making

plans for demonstrations. Files were created on their political causes, the

criminal records, if any, of the people involved and any plans for civil

disobedience or disruptive tactics.

From the field, undercover officers filed daily accounts of their observations

on forms known as DD5s that called for descriptions of the gatherings, the

leaders and participants, and the groups’ plans.

Inside the police Intelligence Division, daily reports from both the field and

the Web were summarized in bullet format. These digests — marked “Secret” — were

circulated weekly under the heading “Key Findings.”

Perceived Threats

On Jan. 6, 2004, the intelligence digest noted that an antigentrification group

in Montreal claimed responsibility for hoax bombs that had been planted at

construction sites of luxury condominiums, stating that the purpose was to draw

attention to the homeless. The group was linked to a band of

anarchist-communists whose leader had visited New York, according to the report.

Other digests noted a planned campaign of “electronic civil disobedience” to jam

fax machines and hack into Web sites. Participants at a conference were said to

have discussed getting inside delegates’ hotels by making hair salon

appointments or dinner reservations. At the same conference, people were

reported to have discussed disabling charter buses and trying to confuse

delegates by switching subway directional signs, or by sealing off stations with

crime-scene tape.

A Syracuse peace group intended to block intersections, a report stated. Other

reports mentioned past demonstrations where various groups used nails and ball

bearings as weapons and threw balloons filled with urine or other foul liquids.

The police also kept track of Richard Picariello, a man who had been convicted

in 1978 of politically motivated bombings in Massachusetts, Mr. Browne said.

At the other end of the threat spectrum was Joshua Kinberg, a graduate student

at Parsons School of Design and the subject of four pages of intelligence

reports, including two pictures. For his master’s thesis project, Mr. Kinberg

devised a “wireless bicycle” equipped with cellphone, laptop and spray tubes

that could squirt messages received over the Internet onto the sidewalk or

street.

The messages were printed in water-soluble chalk, a tactic meant to avoid a

criminal mischief charge for using paint, an intelligence report noted. Mr.

Kinberg’s bicycle was “capable of transferring activist-based messages on

streets and sidewalks,” according to a report on July 22, 2004.

“This bicycle, having been built for the sole purpose of protesting during the

R.N.C., is capable of spraying anti-R.N.C.-type messages on surrounding streets

and sidewalks, also supplying the rider with a quick vehicle of escape,” the

report said. Mr. Kinberg, then 25, was arrested during a television interview

with Ron Reagan for MSNBC’s “Hardball” program during the convention. He was

released a day later, but his equipment was held for more than a year.

Mr. Kinberg said Friday that after his arrest, detectives with the terrorism

task force asked if he knew of any plans for violence. “I’m an artist,” he said.

“I know other artists, who make T-shirts and signs.”

He added: “There’s no reason I should have been placed on any kind of

surveillance status. It affected me, my ability to exercise free speech, and the

ability of thousands of people who were sending in messages for the bike, to

exercise their free speech.”

New Faces in Their Midst

A vast majority of several hundred reports reviewed by The Times, including

field reports and the digests, described groups that gave no obvious sign of

wrongdoing. The intelligence noted that one group, the “Man- and Woman-in-Black

Bloc,” planned to protest outside a party at Sotheby’s for Tennessee’s

Republican delegates with Johnny Cash’s career as its theme.

The satirical performance troupe Billionaires for Bush, which specializes in

lampooning the Bush administration by dressing in tuxedos and flapper gowns, was

described in an intelligence digest on Jan. 23, 2004.

“Billionaires for Bush is an activist group forged as a mockery of the current

president and political policies,” the report said. “Preliminary intelligence

indicates that this group is raising funds for expansion and support of

anti-R.N.C. activist organizations.”

Marco Ceglie, who performs as Monet Oliver dePlace in Billionaires for Bush,

said he had suspected that the group was under surveillance by federal agents —

not necessarily police officers — during weekly meetings in a downtown loft and

at events around the country in the summer of 2004.

“It was a running joke that some of the new faces were 25- to 32-year-old males

asking, ‘First name, last name?’ ” Mr. Ceglie said. “Some people didn’t care; it

bothered me and a couple of other leaders, but we didn’t want to make a big

stink because we didn’t want to look paranoid. We applied to the F.B.I. under

the Freedom of Information Act to see if there’s a file, but the answer came

back that ‘we cannot confirm or deny.’ ”

The Billionaires try to avoid provoking arrests, Mr. Ceglie said.

Others — who openly planned civil disobedience, with the expectation of being

arrested — said they assumed they were under surveillance, but had nothing to

hide. “Some of the groups were very concerned about infiltration,” said Ed

Hedemann of the War Resisters League, a pacifist organization founded in 1923.

“We weren’t. We had open meetings.”

The war resisters publicly announced plans for a “die-in” at Madison Square

Garden. They were arrested two minutes after they began a silent march from the

World Trade Center site. The charges were dismissed.

The sponsors of an event planned for Jan. 15, 2004, in honor of the Rev. Dr.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday were listed in one of the reports, which noted

that it was a protest against “the R.N.C., the war in Iraq and the Bush

administration.” It mentioned that three members of the City Council at the

time, Charles Barron, Bill Perkins and Larry B. Seabrook, “have endorsed this

event.”

Others supporting it, the report said, were the New York City AIDS Housing

Network, the Arab Muslim American Foundation, Activists for the Liberation of

Palestine, Queers for Peace and Justice and the 1199 Bread and Roses Cultural

Project.

Many of the 1,806 people arrested during the convention were held for up to two

days on minor offenses normally handled with a summons; the city Law Department

said the preconvention intelligence justified detaining them all for

fingerprinting.

Mr. Browne said that 18 months of preparation by the police had allowed hundreds

of thousands of people to demonstrate while also ensuring that the Republican

delegates were able to hold their convention with relatively few disruptions.

“We attributed the successful policing of the convention to a host of N.Y.P.D.

activities leading up to the R.N.C., including 18 months of intensive planning,”

he said. “It was a great success, and despite provocations, such as

demonstrators throwing faux feces in the faces of police officers, the N.Y.P.D.

showed professionalism and restraint.”

City Police Spied

Broadly Before G.O.P. Convention, NYT, 25.3.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/25/nyregion/25infiltrate.html

On Patrol, and Now on Edge

March 25, 2007

The New York Times

By MICHAEL POWELL

The news has been dreadful for two weeks now, a steady rain of shootings and

beatings and knifings and indictments for members of the nation’s largest police

department. Even officers stoic by nature confess to being rattled.

Police Officer Nelida Flores gives a tour of her beat in Greenwich Village: This

is where a drunk knocked her out cold, this is where she tackled a beefy guy

twice her (diminutive) size, this is where some guy called her a sellout for

wearing police blues.

Her nickname is “the pit bull”; she loves her job and shrugs off insults.

Now this voluble woman falls silent. She stands at the corner of Sullivan and

Bleecker Streets, a few steps from where, 11 days ago, a gunman killed Auxiliary

Officers Yevgeniy Marshalik, whom everyone called Eugene, and Nicholas T.

Pekearo. They both reported to Officer Flores.

“My body is shaking — I’m in a fog really.” She shakes her head, a thick

ponytail flowing from beneath her hat. “I loved Nick and Eugene. I promised

their parents I’d take care of them. It’s a nightmare I can’t wake up from.”

The 36,500-strong New York City Police Department is a vast and balkanized

kingdom, bisected by units and divisions. After being celebrated for the crime

drop in the mid-1990s, when relatively few citizens and reporters questioned

their tactics, officers now say they’re underappreciated and underpaid, their

uniforms rendering them walking targets.

Such sentiments are not new, but the storm of the past few weeks, with the

attacks and the legal charges, feeds a palpable sense of worry and grievance

and, sometimes, anger.

An officer with six years on the beat stood outside a high school near Union

Square in Manhattan last week. He ticked off the mayhem of the past two weeks: A

plainclothes officer shot in Harlem, a transit officer stabbed on a subway

platform in Brooklyn, the two auxiliaries gunned down, and three detectives

indicted in Queens. (In the latest attack, a gunman fired at officers responding

to a shooting outside a Bronx deli on Friday night, though none were hit.)

The officer said he felt “very scared, very panicked.”

“We never know when we go outside what is going to happen to us,” he said. “We

are an easy target.”

Another officer in the Bronx said he used to wear “N.Y.P.D.” T-shirts when he

was off duty. Not anymore. He plans to buy a shirt with a removable chest plate

that he can use off duty, at a cost of about $1,000.

“It feels like open season on cops,” he said. “It really feels like you got a

target on your back.”

These two officers were among a dozen interviewed last week, most of whom spoke

on the condition of anonymity because it is against department policy to do so

without approval. The Police Department asked Officer Flores — and two of her

precinct’s commanding officers — to speak on the record.

A sergeant in Brooklyn with a decade in uniform waved off talk of fear: He is

annoyed. For a grand jury to indict the three detectives in the shooting of Sean

Bell just two days after two auxiliary officers were killed? That is a bitter

draught to swallow.

The sergeant took a poke at a minister and a councilman who led the call for

indictments, whose names evoke snorts of disgust from some officers: “I’d like

to see the Rev. Al Sharpton or Charles Barron chase down an armed gunman when

they’ve got nothing but a stick.”

If the pendulum of public opinion is swinging back a touch, some of the reasons

are grounded in recent history. Police tactics accompanying the city’s

14-year-drop in crime often drew complaints. The street crimes unit gained a

reputation for frisking far more African-Americans than it arrested; the

department eventually disbanded the unit in the face of protests and lawsuits.

But if many black residents are unwilling to credit such explanations, their

views could reflect the past decade’s alienation.

“Look, we understand that some of these tactics are intrusive and that a lot of

people don’t like them,” said Police Commissioner Raymond W. Kelly. “We need to

do a better job of saying: ‘Hey, we got the wrong person. We apologize.’ ”

Police officers stopped 508,540 people last year, an average of 1,393 per day.

That was up from 97,296 stops in 2002; the police said the rise was due in part

to more faithful reporting.

New York City remains much safer not just for civilians but also for police

officers. In 1971, 14 officers died in the line of duty. Eleven died violently

in 1974. Last year, two officers died, which is in keeping with the recent

trend.

Some police discontent may owe little to the two bloody weeks. Eugene O’Donnell,

a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and a former beat officer in

the city, said the department focused on driving down crime numbers to the

exclusion of more subtle measures. Just as teachers balk at being measured by

test scores, police officers bridle at constantly being told to bring in better

numbers.

“We’re driving enforcement in a bad way, and it’s demoralizing for cops,” Mr.

O’Donnell said. “The job is not seen as having the luster it once did.”

No officer expects riches, but the pay is not great by New York City standards.

Officer Flores, 38, makes around the median household income in the city, which

is just under $60,000. “I live paycheck to paycheck,” she said. “I told my

daughter, ‘Keep your grades up, because you need the scholarship.’ ”

Lt. Michael Casey, 40, who works alongside Officer Flores in the Sixth Precinct,

agreed that the salary was not so hot. But he shrugged off suggestions that the

events of the past two weeks, not least the indictments in Queens, might inhibit

officers.

“When you’re chasing after a guy with a gun, I guarantee you’re not thinking of

a legal case in Queens,” Lieutenant Casey said. “You’re not thinking of anything

until it’s over and you exhale.”

Other officers said they read of the indictments with a nagging thought: But for

the grace of different assignments, they might be facing similar charges. “I

don’t know what was going through their heads,” a five-year veteran in the Bronx

said of the indicted detectives. “They might have made a mistake, but I don’t

think they deserve to be facing criminal charges.”

He said self-doubt roiled him. “Every car I pull over, I think, ‘Am I going to

get indicted for this?’ ” he said.

Police Department statistics suggest that officers overcome such worries.

Arrests as a result of stops more than doubled last year from 2002, and

summonses more than quintupled.

Officers said the recent violence served to remind them that armor and armaments

provide just so much protection. Once a suspect pulls a gun or a knife and an

officer responds, anything can happen.

“When you engage in an argument with a perp or whatever, you have to be in the

officer’s shoes,” explained a young officer with three months on the beat in

East Harlem. “When you’re shooting, you don’t realize how many times you shoot.

It goes so fast, you don’t realize.”

Mr. Kelly, who fired his gun three times as a young beat officer, said he gained

an acute awareness that bullets fly in unintended directions. “You’re running

around and the adrenalin is surging, and, quite frankly, sometimes that’s the

attraction of it,” Mr. Kelly said. “But you also have to exhale and think.”

Age and experience might figure in. Younger officers often spoke of feeling

embattled, while veterans seemed inclined to distinguish between the potential

for violence and the reality, which is that it is rare.

Back in the Sixth Precinct, where the two young auxiliary officers died, the

randomness confounds. One square mile, the Sixth Precinct runs from the Hudson

River to the prosperous center of Greenwich Village.

A shopkeeper on Bleecker Street spotted Officer Flores, walked over and gave her

a long embrace. A woman with a worn face and a gray ponytail waved: “Hi,

officer.”

Officer Flores waved back, then explained that she had arrested the woman “like

six times for drug possession.”

The most common crime here is grand larceny, which the precinct commander,

Deputy Inspector Theresa J. Shortell, defined thusly: “It means some lady went

to the bathroom at a restaurant and left her purse in her chair.” Inspector

Shortell rolled her eyes. “I mean, you know, hello?”

Yet last week Inspector Shortell found herself handing the departmental colors

to a bereaved mother.

Officer Flores resisted the notion, put forward by a number of the officers

interviewed, that officers feel like passengers on the Titanic. She has been

knocked dizzy, the bureaucracy sometimes gets to her, the salary could be better

— but still.

“I’m nosy, I like to be in people’s business, I can take a drunk out at the

knees,” she said, smiling. “Most days I enjoy coming to work.”

She walked down a darkened Sullivan Street, to where Officer Marshalik, 19, died

and then to where Officer Pekearo, 28, died. She examined the handwritten notes

and the tulips, roses and carnations taped to a lamppost. “They were trying to

do what I taught them, they were trailing behind until he turned around,” she

said. “Their parents used to worry, and I would say: ‘You tell them that I’ll be

your mother away from home.’ ”

There was silence. Rain misted on her visor.

“I think every cop wants to get out, retire, without shooting a gun,” she said.

“But danger is always there. You know that, and still your heart breaks.”

Cassi Feldman, Manny Fernandez and Michael Wilson contributed reporting.

On Patrol, and Now on

Edge, NYT, 25.3.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/25/nyregion/25voices.html

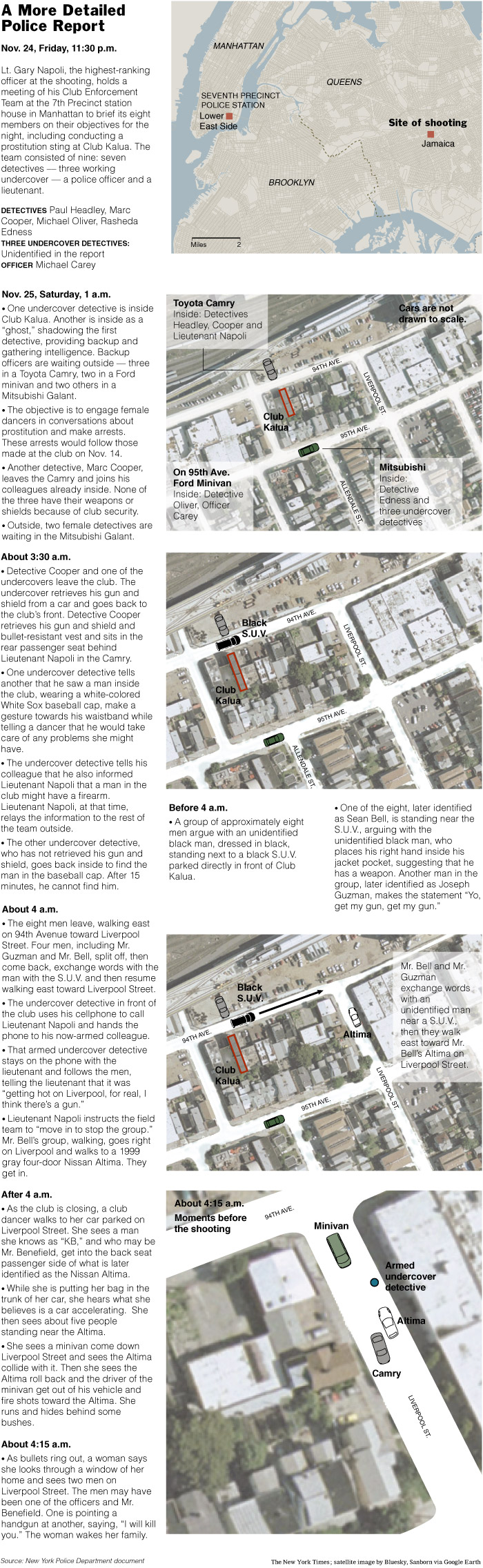

Three Detectives Plead Not Guilty in

50-Shot Killing NYT

March 20, 2007

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/20/nyregion/20cops.html

Three Detectives

Plead Not Guilty

in 50-Shot Killing

March 20, 2007

The New York Times

By ELLEN BARRY and COLIN MOYNIHAN

The three detectives left their homes in the predawn darkness yesterday. They

walked in the back entrance of the courthouse in Queens to Central Booking,

where they went through a routine that must have seemed familiar: fingerprints,

waiting, mug shots, more waiting, paperwork, more waiting.

The three men had logged hundreds of arrests. But this time, they were turning

themselves in.

All three pleaded not guilty to numerous charges — including, for two of them,

first- and second-degree manslaughter — in the death of Sean Bell, a 23-year-old

black man who fell in a volley of police gunfire as he was leaving a Queens

nightclub early on Nov. 25, the morning of his scheduled wedding. Mr. Bell and

his two friends were unarmed, though the officers apparently believed there was

a gun.

The case has reopened wounds in a city where both crime and racial strife seemed

to have abated.

Yesterday’s proceedings, with the unsealing of an eight-count indictment,

brought the case into a very public phase.

In court, the three detectives stood with their shoulders squared, facing the

judge. In a wheelchair behind them, staring at their backs, was Joseph Guzman,

who was shot multiple times in the barrage. “R.I.P. Sean Bell,” read his hooded

sweatshirt.

“Today we got an indictment — Round 1,” said Mr. Guzman, who rose from his

wheelchair to speak with reporters after the arraignment. “We got a hard road to

go. We lost somebody dear. We’re going to fight all the way until we get

justice.”

Five police officers had fired into the car carrying Mr. Bell, Mr. Guzman and a

third man, Trent Benefield, during a chaotic confrontation outside Club Kalua on

Liverpool Street in Jamaica.

The most serious charges are against Detective Michael Oliver, who fired 31

shots, and Detective Gescard F. Isnora, who fired 11 times. Both face counts of

first- and second-degree manslaughter and second-degree reckless endangerment.

Detective Oliver, 35, also faces charges of first-degree assault and

second-degree endangerment; Detective Isnora, 28, faces a charge of

second-degree assault. Those charges could bring a maximum sentence of 25 years.

Detective Marc Cooper, 39, who fired four times, faces two charges of reckless

endangerment, misdemeanors that carry a maximum sentence of one year. The two

other officers were not indicted. Detectives Isnora and Cooper are black;

Detective Oliver is white.

Yesterday, Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg urged New Yorkers to “respect the result

of our justice system.”

Mr. Bloomberg added: “It also needs to be said that being a police officer, as

we were reminded several times last week, is a very dangerous job. And although

a trial will decide whether crimes were committed in this case, day in and day

out the N.Y.P.D. does an incredible job under very difficult circumstances.”

The three detectives arrived at the courthouse in Kew Gardens at 7 a.m., then

spent much of the next six hours in a stuffy room in Central Booking, where they

sat for mug shots and fingerprints. James Culleton, a lawyer for Detective

Oliver, called it “a slow day, a slow process, but it’s usually what happens

when you surrender a client.”

Mr. Culleton said Detective Oliver was “very nervous.”

“He was very upset; these are very serious charges,” Mr. Culleton said.

The wait was a somber one, said Philip E. Karasyk, who represents Detective

Isnora. “There is nothing more heart-wrenching than to a see a police officer

put through the system, especially one who didn’t do anything wrong,” Mr.

Karasyk said.

By the time the three detectives entered the courtroom about 2:30 p.m., every

seat was taken. On the left side of the courtroom were supporters of the

officers: their families, union officials and rows of men wearing detective

badges pinned to dark business suits. On the right were relatives of Mr. Bell,

several holding children, wearing buttons with his photograph. One of them,

George Taggart, had fixed his gaze across the courtroom, toward the door where

the officers would enter.

“We’ll get a chance to see them up close and personal,” he said.

Last to file in was a caravan of a dozen people led by the Rev. Al Sharpton.

Behind him was Nicole Paultre Bell, Mr. Bell’s fiancée, wearing a black suit,

her hair sleek and bobbed. Mr. Benefield was behind her, walking with a crutch.

Mr. Guzman’s wheelchair was on the aisle.

Finally, Justice Randall T. Eng entered the courtroom, and asked that the

defendants be brought forward.

Lawyers for all three police officers entered their not guilty pleas to each

count. As they spoke, Valerie Bell, Mr. Bell’s mother, covered her face with her

hands. Justice Eng set bail at $250,000 bond, or $100,000 cash, for Detectives

Isnora and Oliver; their lawyers said they would post it. Detective Cooper’s

lawyer, Paul P. Martin, asked that his client be released on his own

recognizance.

“He is the father of three, and his wife and children are in the audience,” he

said. Justice Eng agreed, and adjourned the case until April 11.

All three officers filed out through a side door, 23 minutes after they had

entered. About a half-hour later, they climbed into a line of vehicles and were

whisked away.

Outside, the weather had turned colder, and Mrs. Bell held her handbag tightly.

She read to reporters from a piece of notebook paper covered with handwriting.

“I miss him desperately,” she said of her son. “Countless times I tried to bring

forth my own understanding only to be humbled by the weight of my own thoughts.”

She added, “This is truly one of the most devastating and challenging times of

our lives.”

Ms. Paultre Bell emerged, too, and spoke two quiet sentences. “Today was just a

baby step in this long road we have ahead of us,” she said. “We are here to

fight, and we’re going to continue to pray for justice.”

The Police Department will now undertake its own investigation of the officers

who were not indicted, including formal interviews with the officers and a

Firearms Discharge Review Board, Police Commissioner Raymond W. Kelly said

yesterday. He said the police could not investigate until the prosecutor had

decided whether criminal charges were warranted.

Mr. Kelly said that Detectives Isnora, Cooper and Oliver had been suspended

without pay, and the two officers who were not indicted — Officer Michael Carey

and Detective Paul Headley — had been placed on modified assignment, as was Lt.

Gary Napoli, who was leading the team on Nov. 25.

Richard A. Brown, the Queens district attorney, said at a news conference early

in the day that the grand jury proceedings were “as thorough and complete as

I’ve ever participated in.”

His office’s investigation, he said, drew in 100 witnesses and 500 separate

exhibits. He said the grand jury “acted in the most responsible and

conscientious fashion,” and noted that he could not recall a grand jury that

deliberated for three days on a case, as this one did.

“This was a case that was, I’m sure, not easy for them to resolve,” he said.

Mr. Sharpton, who met with Mr. Brown for an hour after the arraignment, told

reporters afterward that he hoped to see “an aggressive prosecution, with no

plea-bargaining or harassment of witnesses.” He said the two surviving victims,

Mr. Benefield and Mr. Guzman, would not cooperate with the authorities if the

trial was moved to another venue.

“There is no victory here,” Mr. Sharpton said of the arraignment. “But we hope

we can get justice. Now it’s time for at least these three to pay for what they

did on Nov. 25, 2006.”

Michael Palladino, the president of the Detectives Endowment Association, said

defense lawyers might move for a change of venue, but had not made a decision.

“Once we put a full legal team together we’ll definitely research that issue,”

he said.

At a news conference after the proceedings, he said the manslaughter charges

implied that the officers intended to kill Mr. Bell, which he called “a chilling

message to all of law enforcement.”

“It’s a dark day for our detectives and the N.Y.P.D.,” he said. “However, I

think it is a good day in that we can finally get involved in the process. Our

defense begins today.”

At 4 p.m., the detectives were gone and the courthouse had mostly emptied. Mr.

Bell’s family marched west, in a group of about two dozen, down Queens

Boulevard. The police removed the barricades in front of the courthouse, and the

last demonstrators packed up and went home.

Behind them, a handmade sign fluttered on a tree.

“Detective Cooper,” it read. “You took a father and a husband.”

Reporting was contributed by Ann Farmer, Daryl Khan, Sean McManus and William K.

Rashbaum.

Three Detectives Plead

Not Guilty in 50-Shot Killing, NYT, 20.3.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/20/nyregion/20cops.html

A Slain Officer’s Mother

Tells of Her Sad Intuition

March 17, 2007

The New York Times

By ANDY NEWMAN

Nicholas T. Pekearo’s mother knew.

She was waiting up for him Wednesday night. He always stayed at her apartment in

the West Village after he worked a shift as an auxiliary police officer. “I

wanted to hear him coming up those stairs,” she said, even if it was 1 or 2 in

the morning.

“The minute I heard those sirens coming down Morton Street, I knew it,” said

Iola Latman, the officer’s mother. “I was on the phone with my daughter. I said,

‘I hope Nick’s O.K.’ I put the phone by the living room window so she could

hear. It was just so unreal.”

It was unreal, but it was all too real. She knew it when she called her son and

told his voicemail, “It’s 10 o’clock, please call me right back.”

And she knew it for sure a few minutes later when a man in a blue uniform rang

the doorbell.

Things had not gotten much less unreal by yesterday afternoon. Ms. Latman found

herself sitting before a display of the latest models of funeral urns in an

upstairs conference room at a funeral home on West 14th Street.

Downstairs, the place was filling up with people she had never met. Most of them

wore blue uniforms, too. Auxiliary officers, street officers, emergency services

officers — it made no difference.

They had all come to pay tribute to her son, 28, a wisecracking bookseller and

aspiring noir novelist by day, auxiliary officer by night, who was killed with

his partner in the line of duty by an aspiring and apparently delusional

horror-film director who had just murdered a bartender at an Italian restaurant.

The doors of the chapel at Redden’s Funeral Home opened. The long line of blue

snaked in. Inside, the real jostled with the unreal. Wreaths of flowers lined

the side walls. In the front, in an open coffin, rested Officer Pekearo, his hat

by his side. He looked peaceful.

At the back of the chapel, grim, abrasive music seeped quietly from a portable

stereo. It was Nick Cave, chronicler of the unsaved and unsavable and one of

Officer Pekearo’s favorites. The CD was called “Abbatoir Blues.”

“Well most of all nothing much ever really happens,” Mr. Cave crooned sickly,

“and God rides high up in the ordinary sky/Until we find ourselves at our most

distracted/And the miracle that was promised creeps quietly by.”

Auxiliary police officers do not tend to get killed out on patrol. They are the

unarmed, all-volunteer eyes and ears of the paid police force.

But sometimes the impossible, the unreal, happens. Auxiliary Police Officer

Christian Luckett, recalled attending the funeral of the last auxiliary officer

killed in the line of duty, in 1993. Officer Luckett was 10 at the time. His

father, a career police officer, brought him along.

“I hope that we can push to get more,” Officer Luckett said. “More recognition.

More status.”

Officer Pekearo and his partner, Auxiliary Officer Yevgeniy Marshalik, at any

rate, are being recognized. Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg said yesterday that he

was granting special awards for heroic acts to the officers’ families.

The awards come with $66,000 each — money that the families would not otherwise

have received since the officers were not eligible for line-of-duty benefits

granted to paid officers. The mayor said the city would help the families apply

for other government benefits that would add up to $411,000 per family.

Officer Pekearo’s funeral will be today, as will the wake for Officer Marshalik,

whose funeral is scheduled for tomorrow. The funeral for the restaurant worker,

Alfredo Romero, will be Monday.

At the wake, the slain officers’ colleagues vowed to carry on in their memory.

“I don’t know how to recover from this,” said Auxiliary Lt. Vera T. Reale, the

senior auxiliary officer at the Sixth Precinct, where the officers worked. “But

I’m not going to let it stop me from doing my job. I’ve been doing this for 20

years and I’m not going to stop now.”

Police Officer Gregory Abbott of the Sixth Precinct, a 14-year veteran, praised

Officers Pekearo and Marshalik. “They had to be brave to do what they did

unarmed,” he said.

On the receiving line of grief stood Officer Pekearo’s companion, Christina

Honeycutt, chewing gum and wearing a smile that seemed composed of equal parts

exhaustion and shock.

“Thank you so much” she said to an auxiliary officer who had not approached her

yet. The officer froze, then shook her hand for a few seconds, unsure of what to

say. “We all feel he was doing the right thing," he finally managed. “Thank you

so much,” Ms. Honeycutt said again, and turned to the next mourner.

Rebecca Cathcart and Ray Rivera contributed reporting.

A Slain Officer’s Mother

Tells of Her Sad Intuition, NYT, 17.3.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/17/nyregion/17wake.html

50-Shot Barrage

Leads to Charges for 3 Detectives

March 17, 2007

The New York Times

By AL BAKER

A grand jury voted yesterday to indict three city police detectives — two

black men and a white man — in the killing of an unarmed 23-year-old black man

who died in a burst of 50 police bullets outside a Queens strip club hours

before he was to be wed last year, defense lawyers and police union leaders said

last night.

The jury charged two of the detectives — Gescard F. Isnora, an undercover

officer who fired the first shot, and Michael Oliver, who fired 31 shots — with

manslaughter, two people with direct knowledge of the case said. The third

detective, Marc Cooper, who fired four shots, faces a lesser charge of reckless

endangerment, those two people said.

Detectives Isnora and Cooper are black; Detective Oliver is white. They were

among five police officers who fired into a gray Nissan Altima carrying the

bridegroom, Sean Bell, and two friends during a chaotic confrontation in Jamaica

early on the morning of Nov. 25. Neither Mr. Bell nor his friends, both of whom

were wounded, were armed, although the police officers apparently believed that

they were.

The grand jury reached its decision after three days of deliberations and nearly

two months of hearing evidence in an emotionally charged case whose stark

outlines — five officers firing 50 bullets at three unarmed men who had been out

celebrating — prompted an outpouring of anger in some minority communities, and

widespread comparisons to the death of Amadou Diallo, an unarmed African street

peddler who was felled by 19 of 41 police officers’ bullets fired at him in

1999.

The grand jurors, who dispersed into the wintry afternoon yesterday, indicted

the three officers on less-serious charges than the second-degree murder charges

filed against the four police officers who shot Mr. Diallo. All four were

acquitted.

It was unclear whether Richard A. Brown, the Queens district attorney, sought

the indictment of the other two officers who fired at Mr. Bell, Detective Paul

Headley, 35, who fired one shot, and Officer Michael Carey, 26, who fired three

shots. All five of the officers testified voluntarily before the grand jury

without immunity from prosecution.

Mr. Brown scheduled a news conference on Monday morning. Lawyers for the

indicted detectives said they had been told to have the men surrender on Monday

— the next day that State Supreme Court in Queens is in session. Mr. Brown’s

office, which would not confirm the indictments, said the grand jury’s decision

had to remain sealed until at least one officer was formally charged in court.

The person with direct knowledge of the case who said Detectives Isnora and

Oliver faced manslaughter charges did not know if they were first- or

second-degree counts. Second-degree manslaughter is defined as recklessly

causing the death of another person. First-degree manslaughter is defined as

causing the death of a person while intending to cause serious physical injury

to that person or causing the death of a third person under those circumstances.

The three officers may also face additional lesser charges.

Some leaders in the black community expressed muted optimism as news of the

indictments spread late yesterday, while others felt the indictments did not go

far enough. In Jamaica, some detected a sense of relief that at least some of

the officers would face charges.

“As long as I know that somebody got something, I can live with that,” said

Bishop Lester Williams, who was to officiate at Mr. Bell’s wedding on the day he

died. “I have some degree of relief.”

If there had been no indictments, he said, “you have groups out there that would

not have been calm. The youth of this city would have responded.”

Lawyers for the indicted officers criticized the grand jury’s action.

Philip E. Karasyk, who represents Detective Isnora, said, “Obviously, my client

is upset, and he’s looking forward to having his day in court, and we’re all

confident he will be vindicated.”

Paul P. Martin, a lawyer for Detective Cooper, 39, said: “I am disappointed with

the grand jury’s decision, but this is just the first stage of a long process,

and I am confident that once all the facts are considered by a jury of Detective

Cooper’s peers that he will be exonerated of all charges.”

James J. Culleton, the lawyer for Detective Oliver, said the indictment “was not

unexpected — a grand jury presentation is one-sided,”

"I firmly believe that he will be found not guilty," he said of Detective

Oliver, 35, who, with Detective Isnora, 28, were considered the most vulnerable

to criminal charges. Detective Oliver fired far and away the most bullets,

emptying one magazine, reloading and emptying a second, and Detective Isnora

opened fire first, touching off the 50-shot barrage. Detective Isnora fired 11

shots, emptying his gun.

Michael J. Palladino, the president of the Detectives Endowment Association,

confirmed the indictments but said he did not know the charges and would not

know them until Monday, when they were unsealed.

“I know the grand jury worked very long and very hard on this particular case,”

Mr. Palladino said at a late-afternoon press conference, surrounded by officials

of his association. “I respect their decision. However I firmly disagree with

the decision to indict these officers.”

Mr. Palladino predicted that the jury’s vote would have a chilling effect on

police officers in the city and nationwide.

“The message that’s being sent now is that even though you’re acting in good

faith, in pursuit of your lawful duties, there is no room, no margin for error,”

he said.

Stephen C. Worth, a lawyer for Officer Michael Carey, described the moment he

learned his client had not been indicted:

Mr. Worth said he got a call from Charles Testagrossa, the prosecutor who

presented evidence to the grand jury, who “told me there was no true bill as to

my guy.”

“Obviously,” he said, ”we are gratified by the grand jury’s decision as to Mike,

and I have always believed that he acted professionally on the night of this

incident.”

Police Department procedures call for the suspension of officers who are charged

with a crime, and the three detectives will be ordered to surrender their

shields; all five officers are already on paid leave without their weapons.

Those who are suspended will be unpaid.

If indictments of police officers are unusual, convictions are even more so.

Many saw a jury’s decision to acquit the officers who opened fire on Mr. Diallo

after a two-month trial as a firm rejection of the powerful charges against

them. In recent years in New York City, Bryan Conroy, a police officer who shot

a peddler in a Chelsea warehouse had faced second-degree manslaughter charges,

but was convicted of the lesser charge of criminally negligent homicide by a

judge, who sentenced him to probation.

The detectives indicted in the Bell case were in a larger group seeking

prostitution arrests outside the Club Kalua, a topless bar in Jamaica that had

been plagued by narcotics and prostitution activity, under-age drinking and

guns.

Detective Isnora had trailed Mr. Bell’s party, which was broken into two groups

of four men, believing that Joseph Guzman, one of Mr. Bell’s companions, had a

gun and was about to use it, according to a person familiar with the detective’s

account.

The detective approached Mr. Bell’s car. But Mr. Bell drove forward, clipping

him, and then hit a police minivan, backed up, nearly hitting the detective

again and slammed into the minivan a second time, the police have said.

Detective Isnora, with his shield around his neck, said he opened fire,

according to the person familiar with his account. This led to the fusillade of

shots, with some of the officers apparently believing that their colleagues’

muzzle flashes were those of assailants.

Mr. Bell was killed as he sat in the driver’s seat. Trent Benefield, 23, who was

in the passenger seat, was struck three times, in the leg and buttock, and Mr.

Guzman, 31, who was in a back seat, had at least 11 bullet wounds along his

right side, from his neck to his feet.

Like the officers, the wounded men told their stories before the grand jury.

Protests that followed the shooting were mostly peaceful. Mayor Michael R.

Bloomberg convened a meeting of black religious leaders and elected officials at

City Hall. He emerged from it calling the circumstances “inexplicable” and

“unacceptable,” and said, “It sounds to me like excessive force was used.”

Mr. Bloomberg’s quick reaction was viewed as a salve to the situation and a

turnabout from the approach of his predecessor, Rudolph W. Giuliani, who did not

reach out to black leaders in the immediate aftermath of the fatal shooting of

Mr. Diallo.

The panel of grand jurors began its work on Jan. 22 and met as often as three

times a week in an auditorium-style room in an office building in Kew Gardens.

The officers testified in the reverse order of the number of rounds they fired:

Detective Headley and Officer Carey testified on March 5; Detectives Cooper and

Isnora, testified on March 7; and Friday last week, Detective Oliver testified

in the zenith of the process.

Deliberations seemed to move slowly and in fits and starts. After Mr.

Testagrossa read the charge — the instructions on the law that the panel had to

consider as it weighed the evidence — the panelists were left alone to

deliberate.

Reporting was contributed by Cara Buckley, Diane Cardwell, Jim Dwyer, Manny

Fernandez, Colin Moynihan and William K. Rashbaum.

50-Shot Barrage Leads to

Charges for 3 Detectives, NYT, 17.3.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/17/nyregion/17grand.html?hp

Police Nab Dad

Accused of Stabbing Baby

March 16, 2007

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Filed at 2:59 p.m. ET

The New York Times

INDIANAPOLIS (AP) -- A man accused of stabbing his 11-month-old son with a

kitchen knife and throwing him out a car window was arrested Friday, two days

after fleeing the scene, police said.

Kevin Chandler, 30, was arrested without incident in a home in suburban

Lawrence, according to police in suburban Speedway, where the boy was injured

Wednesday.

Police say Chandler stabbed Devon Chandler and then dumped him out the parked

car and onto the pavement with the knife stuck in the toddler's back.

The baby was in good condition Friday after surgery, police said.

Police believe the incident occurred as Chandler and the boy's mother, Angela

Limbrock, were in a car preparing to leave Limbrock's apartment to visit a

friend.

Limbrock realized the child's car seat was inside. She handed the baby to

Chandler, who was in the back seat. As she got out, she heard Chandler swear at

the child and turned around to see him throw Devon out, according to a police

report.

Chandler fled, sparking a search. His arrest came after an anonymous tip from a

woman.

Police Nab Dad Accused

of Stabbing Baby, NYT, 16.3.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/us/AP-Toddler-Stabbed.html

Lives Intersect Violently on a Busy City Street

March 16,

2007

The New York Times

By MICHAEL WILSON

They

weren’t cops’ cops. They weren’t sons of police officers, born with blue in

their blood, like many in the New York City Police Department. They didn’t even

tell some people about their jobs. Bookish, even naïve young men, each brought

an eccentric back story to his role as an auxiliary police officer, and to their

partnership on the street.

The younger officer, Yevgeniy Marshalik, 19, whose Russian family fled the war

in Chechnya when he was a young boy, was a star member of his high school

debating team who would go back to his New York University dorm to tell his

classmates tales of the streets.

The other man, Nicholas T. Pekearo, was nine years older, but in a way, more the

boy — a crime and comic-book buff, blessed with a vivid imagination and a morbid

curiosity, who longed to write his own noir novels, his friends said.

His death could have been a dark ending to one of his own stories. Mr. Pekearo,

a salesman at a small bookstore on the Upper East Side, had saved up to buy his

own bulletproof vest — the department does not provide them to auxiliary

officers .He was wearing it Wednesday night when a gunman killed him with six

shots in the torso and shoulder at point-blank range on Sullivan Street in

Greenwich Village.

The gunman killed his partner, Mr. Marshalik, seconds later with a single shot

to the back of his head.

The deaths were captured on a startling surveillance videotape that the police

showed on television yesterday.

Police officers chased the gunman, David R. Garvin, who had killed a bartender

moments earlier, and fatally shot him on Bleecker Street.

The deaths of the two other men, who had chased an armed suspect — something

auxiliary officers are instructed not to do — shocked the city in large measure

because they were unarmed volunteers, not full-fledged police officers.

No one felt it more powerfully than the real police officer, Nelida Flores, who

trained them. Last night she told a group of auxiliary officers, “They were my

kids.”

Friends and family of the two officers, asked what drew them to the role, spoke

of their earnestness and altruism, of a simple wish to do good.

“The moment they met, they clicked,” Officer Flores said.

The Marshalik family emigrated from southwest Russia 13 years ago, and Mr.

Marshalik’s father, Boris, settled them in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, where he

opened a practice as a pediatrician. Yevgeniy, who was known to his friends as

Eugene, quickly threw himself into school, a driven, curious child who loved the

Discovery Channel.

In fourth grade, Yevgeniy won an essay competition about the United States

Constitution. “They gave him a medal,” said his mother, Maya Marshalik. “I was

so proud, this boy who came here only some years ago. He could become anyone.”

“This city, Manhattan, was his city,” she said. “He couldn’t imagine living

anywhere else.”

At the city’s elite Stuyvesant High School, he was a standout member of the

debating team. “The only thing he seemed to enjoy more than debating was helping

other kids to learn to debate,” said a former teammate, Zach Frankel, 17. “The

fact that he could get up and give an eight-minute speech, impromptu, about

issues ranging from the philosophy of Nietzsche to policy in the Western Sahara,

in such an eloquent manner, is just a testament to how hard he worked and how

smart he was.”

He joined the city’s auxiliary police program early last year, not telling even

his mother at first, because he knew she would worry. He tried to calm her

concerns, she said, telling her over and over: “Don’t worry, don’t worry. The

last time they shot an auxiliary, it was a long time ago.”

“We never pressed him,” she said. “This is what he chose.”

Mr. Frankel, his former debating teammate, was startled to see him in uniform

months later: “I see him and he has a cop uniform, handcuffs and a nightstick,”

he said. “I remember thinking, is Eugene joking around? He explained it.

“It makes sense to me. He had a real impulse to help people out, and I think he

liked the idea of fulfilling what he viewed as a civic duty.”

A fellow auxiliary officer, Glenn E. Sabas, said they were fast friends. They

talked about girls, about Mr. Marshalik’s unrequited crush on a woman he had

known since he was 11. They talked about the job.

He completed his annual quota of hours on patrol in a matter of few months, Mr.

Sabas said. “He loved it,” he said. “He loved going out.”

Mr. Marshalik hoped to become a prosecutor in the district attorney’s office,

and Mr. Sabas said he held a part-time job at the Olympic Tower on Fifth Avenue

in Midtown, where he worked as an elevator operator and a doorman. Friends said

he was generous with his time, driving once to Binghamton to visit a homesick

friend at college there.

“That was one of his most amazing qualities,” the friend, Irina Kaplan, said in

an e-mail message. “He was fiercely loyal, and he would do anything for the

people he cared about.”

A friend of the Marshalik family, Andrew Zaretsky, 47, said of the teenager: “He

always wished to act like a man, a real man. He wanted to protect our society.”

Mr. Zaretsky said relatives who gathered yesterday at the parents’ home in

Valley Stream, on Long Island, struggled to understand how Mr. Marshalik could

have been caught so defenseless. “They are not blaming the Police Department,”

he said, “only questioning why he was so ill-prepared.”

His partner, Mr. Pekearo, grew up in the neighborhood he served. That was the

whole idea, said his girlfriend, Christina Honeycutt, 34.

“He’d gone through the dark years of New York City as a kid, tripping over

hypodermic needles in the street, and he’d come into this time of relative ease

in the city and he just wanted to give back,” she said. “He wanted to help

anyone, like talking down a guy who wanted to kill himself one night. Nick was

the one who stood with him.”

Mr. Pekearo worked at Crawford Doyle Booksellers on Madison Avenue five days a

week for the last five years. “He was steeped in hard-boiled, noir kinds of

things,” said the shop’s business manager, Ryan Olsen. “He was our go-to guy for

mysteries. He grew up with comics — that was still a love of his.”

He and Ms. Honeycutt met when she started working at the shop in 2004. “He had

the classic New York sense of humor,” she said. “Self-deprecating, ironic,

sarcastic. You’d feel comfortable with him.”

The couple moved in together and were living in Park Slope, Brooklyn, over a

gourmet store. He fed squirrels out on the fire escape. By then, he had been

with the police for more than a year, since 2003. He said of his job, “ ‘I know

it can definitely be dangerous.’ ” she said. “But he had a lot of faith in the

force.”

Besides, she said, Mr. Pekearo rarely encountered serious peril as an auxiliary

police officer. “It was a lot more trying to get drunk people rides home,” she

said. “Every now and again, he’d go into Starbucks and there would be some

riffraff and he’d try to mediate.”

At Hercules Fancy Grocery in the West Village, the owner, Hercules Dimitratos,

sold him Gatorades by day and saw him in uniform at night. “He’d pass by all the

time and he’d say, ‘Be careful, Hercules,’ ” Mr. Dimitratos said. “He was always

giving advice. ‘If you have any trouble, call us.’ ”

He took classes at Empire State College in Manhattan, anticipating graduating

within the year, and found a mentor in his literature and creative writing

instructor, Shirley Ariker, 66. “He was very inventive, very imaginative,” she

said. “He wrote stories about people struggling to do the right thing.”

One novel that several people recalled reading involved a werewolf struggling to

do right in a Vietnam-era time of troubles — “how to create good in the world

from what is so bad about him,” Ms. Ariker said.

“Nick is a very tender person, a very kind person and a very loving person. I

think that’s what he was struggling with. How do you do good in a world where so

much bad happens? He talked about his police work as a chance to help people, to

do good things.

“I think Nick was a romantic and he wanted to make the world right, like

Dashiell Hammett’s characters,” she said. “He wanted to do right.”

The werewolf book had piqued the interest of an editor, and Mr. Pekearo was

working on a revised draft. “He was just super talented,” said the editor, Eric

Raab, of Tor Books. “I see thousands of manuscripts a year. When I saw his, I

thought, man, this guy’s got something I’ve got to nurture.”

His girlfriend said his writing showed a clear-cut moral vision. “A lot of his

ideas were about the struggle between death and life, good and evil, justice and

corruption. He was a guy who grew up on comic books.”

Another friend, a manager of a condominium building next door, Peter Roach, said

he learned only yesterday that Mr. Pekearo was an auxiliary officer.

“If I’d known, I would have tried to talk him out of it,” he said. “He just

wasn’t cut out for that. He was a very mild guy. I would have told him he didn’t

have the personality. He was a bookworm. I just couldn’t see Nick on the street

chasing bad guys. There wasn’t a tough bone in his body, and you got to be tough

to be a street cop in New York.”

The police video released yesterday tells a different story. As the gunman runs

along the east sidewalk of Sullivan, Mr. Pekearo shadows him on the opposite

side.

Both men were well liked at the Sixth Precinct station house where they worked.

They were valuable in fighting quality-of-life and other crimes, like theft,

common in a precinct of bars and clubs. “They are our eyes and ears,” one

lieutenant said.

At the bookshop, a doorman from down the street approached a bookseller and said

only, “Our Nick.”

Both men will receive full police honors at their funerals this weekend. That

news cheered Mr. Roach, who imagined Mr. Pekearo hearing it.

“He’d definitely get a kick out of getting full police honors,” he said.

Lives Intersect Violently on a Busy City Street, NYT, 16.3.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/16/nyregion/16cops.html?hp

Uniformed Eyes and Ears

on the Front Lines

March 15, 2007

The New York Times

By JAMES BARRON

They form a kind of shadow police force, uniformed but unarmed

and unpaid. Part community-minded volunteers and part would-be officers, they go

on neighborhood patrols, help with crowd control at places like Yankee Stadium

and serve as an official-looking eyes and ears.

The city’s 4,800 or so auxiliary police officers are never far from trouble, but

usually, said John W. Hyland, the president of the Auxiliary Police Benevolent

Association, trouble goes the other way when they come around.

“For the most part, you’re on routine patrol,” he said. “For the most part, the

bad guys can’t tell the difference whether it’s an auxiliary cop or a regular

cop. It’s one of the best crime deterrents that there is.”

So is the seven-pointed star that auxiliary officers wear. Few, other than

sharp-eyed criminals, could tell that it is different from the shield that

regular officers wear. And few would know that officially, anyway, auxiliary

officers do not have the power that regular officers have: the power to make

arrests.

“It’s a citizen’s arrest,” Mr. Hyland said. “You’re the eyes and the ears. You

make the call.” Meaning, most of the time, an auxiliary officer reaches for his

or her radio and calls for regular officers.

Until last night, six auxiliary officers had been killed in the line of duty in

the half-century since the auxiliary police force was organized. Before the two

deaths in Greenwich Village, the most recent was Milton Clarke, killed 14 years

ago when he heard shots in the street outside his garage in the Bronx. Carrying

his own licensed .380-caliber semiautomatic pistol, he confronted a suspect who

opened fire and struck him six times. Mr. Clarke’s gun jammed after he pulled

the trigger once.

Facing street crime was not the original mission of the auxiliary force, which

was organized as a civil-defense group in the 1950s. Its mission reflected the

nuclear paranoia of cold-war America: to direct crowds to subway stations and

school basements that doubled as bomb shelters.

Auxiliary officers attend classes on topics like handling their nightsticks and

giving Miranda warnings, even though they rarely make arrests. The Police

Department requires that auxiliary officers be older than 17 and younger than

60, though those over 60 may apply for administrative duties. The department’s

Web site also says that auxiliary officers must be United States citizens or

have a valid visa or alien registration card, must live or work in the city,

must be able to read and write English and must have a clean record.

“A lot of the younger guys are using it as a steppingstone to go into law

enforcement,” Mr. Hyland said. “It gets them in the door. They see, do they

really want to do this?”

Uniformed Eyes and

Ears on the Front Lines, NYT, 15.3.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/15/nyregion/15auxiliary.html

2

Auxiliary Officers Among 4 Killed

in Village Gunfight

March 15,

2007

The New York Times

By ALAN FEUER and AL BAKER

Two unarmed

auxiliary police officers were fatally shot last night during a chase with a

gunman on a busy stretch of bars and restaurants in the heart of Greenwich

Village, the authorities said.

The gunman was shot and killed about 9:30 p.m. by regular police officers who

quickly responded to the scene, the authorities said.

The attack began after the gunman entered a pizzeria on Macdougal and West

Houston Streets and shot a bartender who worked there, the authorities said. The

two auxiliary officers — volunteers who dress in uniforms virtually

indistinguishable from regular police officers — followed the gunman toward

Sullivan Street, where he suddenly turned and shot them, the authorities said.

The identities of the two slain officers and the gunman were unavailable early

this morning. The bartender, whose name was also unavailable, was killed as