|

History > 2007 > USA > States > Justice (II)

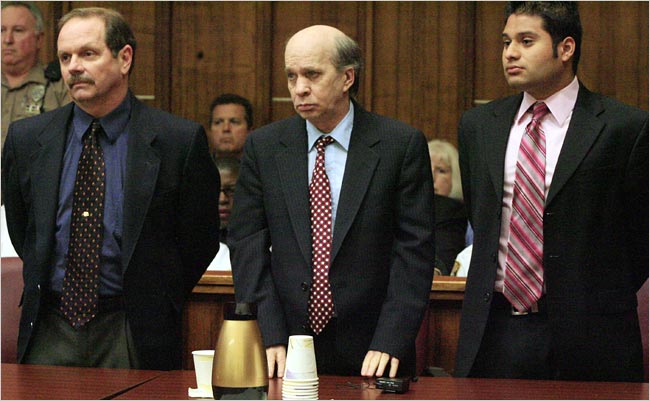

John E. Couey, center,

and his lawyers, Alan Fanter, left,

and

Morris Carranza, listened to the verdict.

Pool photo by Al Diaz

Sex Offender Guilty of Rape and Murder of Florida Girl

NYT 8.3.2007

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/08/us/08verdict.html

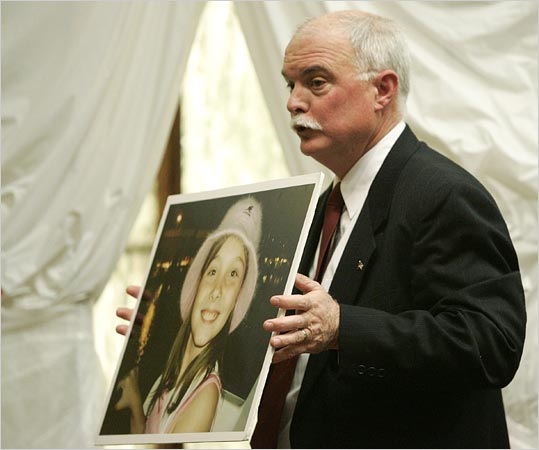

The lead prosecutor, Pete Magrino,

showed a picture of Jessica Lunsford

in his closing statements to the jury in

the Couey trial in

Miami Wednesday.

Pool photo by Al Diaz

Sex Offender Guilty of Rape and Murder of Florida Girl

NYT 8.3.2007

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/08/us/08verdict.html

Located in Hospital,

DNA Clears Buffalo Man

Convicted in ’80s

Rapes

March 29, 2007

The New York Times

By DAVID STABA

BUFFALO, March 28 — The evidence, genetic material from two rapes stored on

microscopic slides, had languished in a hospital drawer for more than 20 years,

as the man convicted of the crimes languished behind bars. Numerous times,

including four in the last two months, the authorities issued subpoenas for the

material, only to be told that it was not in the hospital.

But on Wednesday, the district attorney announced that the slides had finally

been found last week, and that DNA tests on them matched Altemio Sanchez, not

the man convicted of the crimes, Anthony Capozzi.

Mr. Capozzi, 50, who has been incarcerated since his 1985 arrest, could be freed

within a week, the authorities said.

“We’ve been carrying this load around for more than 20 years,” Mr. Capozzi’s

mother, Mary, said in the family’s home on Buffalo’s West Side. “Now the load is

lifted off of us.”

His father, Albert, added, “We have grief for what has happened to us, but we

have joy, because he’s been exonerated.”

It was the latest development resulting from the January arrest of Mr. Sanchez

in connection with a series of rapes and murders dating at least to 1981. Mr.

Sanchez has pleaded not guilty to the murder charges; the statute of limitations

has elapsed on the rape cases.

Several criminal defense lawyers have since raised questions about their own

clients’ convictions, and the police said they were reviewing scores of cases,

including unsolved rapes and those where there had been convictions, that fit

the same pattern.

Several of the rapes Mr. Sanchez is believed responsible for occurred in

Delaware Park, Buffalo’s largest, as did the two for which Mr. Capozzi was

imprisoned.

Frank J. Clark, the Erie County district attorney, said officials at Erie County

Medical Center answered repeated subpoenas by saying they did not have the

evidence. Mr. Capozzi’s lawyer, Thomas D’Agostino, said the hospital had said as

early as 1992 that it did not have the evidence.

But Mr. Clark said that within a day after the most recent request, a

pathologist at the hospital found microscope slides last week containing genetic

material from hundreds of rapes between 1973 and 2002, including those

attributed to Mr. Capozzi. Hospital administrators did not respond to three

telephone messages seeking comment.

“It’s more than frustrating, it’s maddening,” Mr. Clark said of learning the

evidence had been at the hospital all along. “I mean, come on — these are

important issues we deal with. When you make a request like this, with the

impact that it has, and somebody comes back to you and says, ‘Gee, we’re sorry,

this evidence doesn’t exist,’ you just make the human assumption that they

consider it as important as you do and have done what they should do. I have no

reason not to take them at their word.”

Nevertheless, Mr. Clark said the authorities never quite believed the hospital,

hence the repeated subpoenas.

“There were enough whisperings out there for us to believe that maybe their

assertions that the evidence wasn’t there weren’t exactly true,” Mr. Clark said.

“I don’t know why they weren’t on top of it. I don’t know why they didn’t feel

the same urgency that we all felt. I don’t know why they didn’t feel this was

important enough to get to the bottom of.”

Mr. Capozzi, who has schizophrenia, was originally suspected in six attacks that

took place in or near Delaware Park in 1983 and 1984. He was tried in three

rapes and convicted of two.

His family consistently maintained that he was innocent. They argued that his

mental illness left him incapable of planning the attacks, in which the victims

were threatened with a gun, taken to a secluded area and ordered to remain on

the ground for 10 or 20 minutes after the rape.

At the time of his trial, Mr. Capozzi had a prominent three-inch vertical scar

above his left eye. The victims who testified did not mention the scar and

estimated the weight of their attacker at 150 pounds, at least 50 pounds less

than what Mr. Capozzi weighed at the time, Mr. D’Agostino said, adding that

there was no physical evidence linking Mr. Capozzi to the rapes.

“Eyewitness testimony is devastating, but you’ve got to be very skeptical,” Mr.

D’Agostino said. “In Anthony’s case, the problem was that you had three victims

who came in and each one said it was him. You get to a point where jurors say,

‘Maybe the first one was wrong, but all three of them can’t be wrong — they’re

all saying it was the same guy.’ ”

Mr. Capozzi was sentenced in 1987 to 11 2/3 to 35 years in prison. The State

Parole Board has rejected his application for release several times, in part

because he did not admit to the crimes, his lawyer said.

“Anthony has never, ever wavered,” Mr. D’Agostino said. “He has known what it

would mean to say, ‘I did it.’ If he said that, he would have gotten out. And he

wouldn’t do it.”

Housed at Attica Correctional Facility at the time of Mr. Sanchez’s arrest, Mr.

Capozzi has been returned to the state prison hospital in Marcy, N.Y. His father

gave him the news over the telephone.

“We told him he’s coming home,” said his oldest sister, Sharon Miller. “He said,

‘Really? Who is going to pick me up and take me there?’ I don’t think he’s

really digested it yet, but I think he has some idea.”

While detectives working on the case expressed doubts about Mr. Capozzi’s guilt

after Mr. Sanchez’s arrest, Mr. Clark said there was no legal reason to reverse

the conviction until last week’s discovery.

“I’ve always said, don’t give me opinion,” the district attorney said. “I don’t

care what you think, nor does the law care what you think. We deal in facts. And

now we have a fact, probably the strongest single fact that modern technology

provides us with and something that I feel very comfortable relying on.”

Mr. Clark said authorities would analyze the newly discovered evidence to see if

other attacks can be tied to Mr. Sanchez.

“It’s a bittersweet feeling,” Mr. Clark said. “Sweet in that an innocent man has

been vindicated and bitter in the fact that it took us 20 years to do it.”

Mrs. Miller said her brother would most likely move into an assisted-living

facility when he was released. While the date for that remained uncertain

Wednesday, his family — including several nieces born since his arrest who call

him “Uncle Toto” — was planning his welcome-home dinner.

“He’s not a drinker, but I think he’s going to want to have a beer,” his father

said.

Located in Hospital, DNA

Clears Buffalo Man Convicted in ’80s Rapes, NYT, 29.3.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/29/nyregion/29bike.html

'Antifreeze killer' spared death penalty

AP

USA Today

DALTON, Ga. (AP) — Jurors Tuesday spared the life of a former 911

dispatcher convicted of poisoning her boyfriend with antifreeze — the same way

she had killed her husband six years earlier.

Lynn Turner could have faced the death penalty for the 2001 murder of Randy

Thompson, a Forsyth County firefighter and father of Turner's two children.

Instead, the jury sentenced her to life in prison without parole.

She was already serving a life term following her 2004 conviction in the

antifreeze death of her police officer husband Glenn Turner in 1995.

Lynn Turner had maintained her innocence in both cases and did not testify at

trial or during her sentencing hearing Monday.

Prosecutors said she was motivated by greed for the victims' life insurance

money.

Tests on the victims' bodies showed they were poisoned with ethylene glycol, a

sweet, odorless chemical in antifreeze. During the 2004 trial, prosecutors

suggested it could have been placed in foods such as Jell-O.

The jury deliberated for about five hours before reaching a sentencing decision

Tuesday, about the same amount of time it took them to find Turner guilty on

Saturday of malice murder in Thompson's death. The jury's sentence is final; in

cases where the state seeks the death penalty in Georgia, the jury issues the

sentence.

Thompson's family said afterward they believed justice had been done.

Perry Thompson, Randy's father, said he found closure on Saturday when Turner

was found guilty.

"That proved that he hadn't taken his own life," he said. "We knew that all

along anyway, but we wanted everybody else to know."

"Nothing can bring him back," said Thompson's mother, Nita.

Defense attorney Vic Reynolds said Turner was grateful that the jury didn't

sentence her to death.

"The realization will now sink in that she's spending the rest of her life in

prison in this state," Reynolds said. "She's trying to come to grips with that,

but she's very thankful that the jury chose the life option over the death

option."

'Antifreeze killer'

spared death penalty, UT, 27.3.2007,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2007-03-27-antifreeze-deaths_N.htm

Judge: Man must display victim's picture

25.3.2007

USA Today

AP

BARTOW, Fla. (AP) — A judge has ordered a man who pleaded guilty to vehicular

homicide to display a large picture of the victim in his home after serving two

years in prison.

Circuit Judge Robert Doyel said Friday that the picture must be at least 2 feet

wide and displayed prominently. It also must include lettering that says: 'I'm

sorry I killed you.'

Arthur Pierce, 31, was racing with his cousin on a busy street when they caused

an accident that killed 17-year-old Chelsi Gregory, authorities said. Witnesses

told police Pierce was swerving in traffic at about 120 mph when his Cadillac

collided with a pickup in which Gregory was a passenger.

A prosecutor also said alcohol was a factor in the crash. Pierce's cousin,

Christopher Pierce, is set to be sentenced April 5.

An advocate for Mothers Against Drunk Driving requested the photograph be part

of Pierce's sentence, according to The Ledger of Lakeland newspaper.

The judge said that Pierce's probation officer will be allowed to search his

home at any time, and if the photograph is not displayed, it will be considered

a probation violation.

Judge: Man must display

victim's picture, UT, 25.3.2007,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2007-03-25-picture-sentence_N.htm

Ga. Woman Guilty of Murdering Boyfriend

March 24, 2007

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Filed at 2:21 p.m. ET

The New York Times

DALTON, Ga. (AP) -- A former 911 operator was convicted Saturday of murdering

her boyfriend by poisoning him with antifreeze.

Lynn Turner could face a death sentence in the 2001 killing of Randy Thompson, a

Forsyth County firefighter and the father of her two children. The same jury

that convicted her must decide whether to impose that sentence.

She is already serving a life sentence for the 1995 death of her husband, Glenn

Turner, a Cobb County police officer. The murder charge in Thompson's death was

filed after that 2004 conviction.

The trial went to the jury Saturday morning following closing arguments on

Friday.

Turner, who had maintained her innocence in both cases, did not testify in

either trial.

In closing arguments Friday, District Attorney Penny Penn said the motive in

both cases was Turner's greed for the victims' life insurance money.

Lawyers for Turner, 38, rested their case earlier Friday after a defense

toxicologist testified that while one of the victims showed signs of antifreeze

poisoning the other did not, casting doubt on the prosecution theory that the

deaths were similar.

Defense lawyers have argued there's no direct evidence proving murder.

Police didn't launch a criminal investigation of the deaths until a few months

after Thompson died.

Prosecutors said tests on their bodies showed they were poisoned with ethylene

glycol, a sweet but odorless chemical in antifreeze. During Turner's 2004 trial

they suggested it could have been placed in foods such as Jell-O.

Penn said during her closing argument Friday that even though no one saw her do

it, Turner was the last person with both men before they became ill and was the

last person to give them anything to eat or drink.

Defense lawyer Vic Reynolds said the prosecution's evidence adds up to character

assassination, not murder. ''They can predict. They can assume, but that isn't

the law,'' Reynolds said.

Ga. Woman Guilty of

Murdering Boyfriend, NYT, 24.3.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/us/AP-Antifreeze-Deaths.html

Georgia Murder Case’s Cost Saps Public Defense System

March 22, 2007

The New York Times

By BRENDA GOODMAN

ATLANTA, March 21 — A high-profile multiple-murder case has drained the

budget of Georgia’s public defender system and brought all but a handful of its

72 capital cases to a standstill.

The case involves a rape suspect, Brian Nichols, who is accused of escaping from

a courthouse here in 2005 after overpowering a guard, taking her gun and then

killing a judge, a court reporter and two other people before he was recaptured.

Prosecutors say the evidence against Mr. Nichols, including a videotaped

confession, is overwhelming. But the case has cost the public defender system

$1.4 million, and, on Wednesday, the judge in the case postponed jury selection

until Sept. 10.

The judge, Hilton Fuller, said the “issue of funding” and the “complexities of

this case have prevented an orderly and uninterrupted” method of proceeding.

The Georgia Public Defender Standards Council, which manages the public defender

system, has run out of money. That means it can no longer pay the three private

lawyers on Mr. Nichols’s defense team. Judge Fuller said the council had

apparently done all it could to pay expenses in the case, but he added, “We

cannot expect it to provide funds that don’t exist.”

The situation has become a political issue as the legislature weighs a request

for $9.5 million to keep the public defender system solvent through the fiscal

year, which ends in June.

The case “is testing the will of the state of Georgia with regard to whether or

not the death penalty is worth the amount it costs,” said Mike Mears, director

of the standards council.

Georgia is not the only state pondering the cost of defending suspects in

death-penalty cases.

This year, the Colorado House Judiciary Committee voted to abolish the death

penalty, replacing it with a sentence of life without parole, and to use the

money currently spent on capital punishment to help solve some 1,200 cold-case

homicides. The bill’s sponsor, Representative Paul Weissmann, a Democrat, said

it had cost the state $40 million in three decades to execute one inmate and put

two others on death row. The bill now goes to the House Appropriations

Committee.

In Arizona, Maricopa County, which has been overwhelmed by a surge in capital

cases, may not seek the death penalty in some cases to save money, officials

there said.

“It’s a very different argument against the death penalty than ‘taking a life is

wrong,’ ” said Richard Dieter, the executive director of the Death Penalty

Information Center in Washington, who testified in support of the Colorado bill.

“For those who believe in the death penalty but after 30 years don’t feel it’s

done a lot of good for their state, cost is a decisive issue.”

In Georgia, State Senator Preston W. Smith, a Republican and the chairman of the

Senate Judiciary Committee, said he thought the high price of Mr. Nichols’s

defense was by design rather than necessity.

“You’re building in an incentive to destroy the death penalty by building in a

financial nuclear weapon,” Mr. Smith said. “There’s one cynical view that says

this isn’t at all by accident.”

This year, Mr. Smith asked to review a breakdown of the billing for Mr.

Nichols’s defense but was rebuffed by Judge Fuller, who said that might reveal

the defense team’s strategy and compromise the fairness of the trial.

Judge Fuller, a Superior Court judge in neighboring DeKalb County who was

brought out of retirement for the Nichols trial, has been put in the unusual

position of approving all spending for Mr. Nichols’s defense, a responsibility

that would ordinarily fall to the Public Defender Standards Council, which

oversees the Office of the Georgia Capital Defender.

But in 2005, the Office of the Capital Defender was disqualified from managing

Mr. Nichols’s defense after Judge Fuller learned that one of the first four

public defenders assigned to represent him was not qualified to practice law in

Georgia.

Judge Fuller then appointed four new lawyers to defend Mr. Nichols, and the

judge agreed to pay Henderson Hill, a noted defense lawyer from North Carolina,

$175 an hour, about half what Mr. Hill customarily bills his private clients.

Two of Mr. Nichols’s other lawyers are being paid $125 and $95 per hour, and the

fourth is a state employee.

Judge Fuller justified the expenditures in a March 5 order, pointing out that

the prosecutor has assigned five lawyers to the case and has charged Mr. Nichols

with 54 felony counts.

By comparison, the next most expensive capital case in which a private lawyer is

serving as a public defender has cost the state $73,171 in legal fees over 18

months. But the defendant in that case is facing fewer than 10 charges, said Mr.

Mears of the standards council.

The public defender system in Georgia was overhauled in 2003 in an effort to end

wide disparities in the quality of legal services from county to county. The

overhaul, which created the Office of the Capital Defender, was praised by some

critics of the system, but a recent study by the American Bar Association

faulted Georgia for failing to finance the office adequately.

Judge Fuller’s supporters note that Mr. Nichols has offered to plead guilty to

all charges in exchange for a sentence of life without parole, but Paul Howard,

the Fulton County district attorney, has refused to take the death penalty off

the table.

“The Nichols case could have been ended millions of dollars ago if the D.A. had

been prepared to accept life without parole,” said Emmet J. Bondurant, the

departing chairman of the Public Defender Standards Council. “You can’t fault

the defense for trying as hard as they can to save a man’s life.”

Mr. Bondurant pointed out that the council has refused to pay some expenses that

were deemed necessary by Judge Fuller, and “they may result in an appellate

ruling, but we are not in the position of willy-nilly approving any expense

anybody can dream up.”

Nonetheless, Senator Smith has accused the Office of the Capital Defender of

spending money like “drunken sailors on shore leave” to provide an “O. J.

Simpson-style defense, all on the taxpayer’s dime.” He has supported a

resolution that would re-evaluate the way the public defender system operates.

“We’ve created a system that has no fiscal accountability,” Mr. Smith said.

“There’s only an incentive to spend as much as you can in a capital case. It’s

almost unethical not to.”

Georgia Murder Case’s

Cost Saps Public Defense System, NYT, 22.3.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/22/us/22atlanta.html

Defense in Wis. Murder Cites Past Error

March 15, 2007

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Filed at 1:52 p.m. ET

The New York Times

CHILTON, Wis. (AP) -- The attorney for a man who spent 18 years in prison for

a rape he didn't commit asked jurors Thursday to help set things right by

acquitting him of murder in another case.

''You will set a lot of things right if you get it right here,'' defense

attorney Dean Strang said. ''The 1985 case won't matter so much anymore if

justice is done this time.''

In rebuttal, special prosecutor Ken Kratz said it was ''absolutely improper''

for the defense to ask jurors to take the old case into account. He argued that

DNA evidence clearly shows Steven Avery is responsible for the case before

jurors, the killing of 25-year-old photographer Teresa Halbach.

Avery, 44, is accused of luring Halbach to his family's auto salvage yard,

shooting her in the head and burning her body and belongings in the back yard on

Halloween 2005.

Jurors were expected to begin deliberating later Thursday on charges of

first-degree intentional homicide, mutilating a corpse and being a felon in

possession of a firearm.

The killing came two years after Avery was released from prison on the rape

charge, which DNA analysis later showed he did not commit.

A not-guilty verdict now won't change that, Strang told jurors Thursday. ''But

it just won't matter so much anymore -- the injustice done to Steven then --

because there is something redemptive to human beings going back and trying

again to get it right eventually,'' he said.

Avery settled a wrongful-conviction lawsuit against Manitowoc County last year,

but his defense in this case long ago exhausted his $240,000 in proceeds, his

lawyer said.

Strang also urged jurors to look skeptically at witnesses' testimony.

A day earlier, Kratz cited expert witnesses who said Halbach's DNA was found on

a bullet found in Avery's garage, Avery's blood was found in her sport utility

vehicle and her bones were found in a pit behind Avery's trailer.

Kratz said the DNA lets Halbach tell her own story.

''She's telling you, this is how I was killed. She telling you, this is how this

person tried to hide me and where they tried to hide me. And it's the kind of

evidence, it's the kind of powerful evidence that you can't ignore,'' Kratz

said.

Defense attorney Jerome Buting said state crime lab DNA analyst Sherry Culhane,

who found Halbach's DNA on what Buting called the ''magic'' bullet, was under

pressure to find evidence that put Halbach in Avery's garage, and she deviated

from protocol when she contaminated a control test. Culhane testified that it

didn't change the results.

Buting also noted that Halbach's DNA was never found in Avery's trailer, only on

the bullet found four months after Avery was arrested.

Defense in Wis. Murder

Cites Past Error, NYT, 15.3.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/us/AP-Missing-Woman.html

Jury: Death penalty for child killer Couey

15.3.2007

AP

USA Today

MIAMI (AP) — A jury decided Wednesday that a convicted sex

offender should get the death penalty for the kidnapping, rape and murder of

9-year-old Jessica Lunsford, who was buried alive in trash bags just yards from

her home.

The jury, on a 10-2 vote, brushed aside pleas for mercy and a

life sentence from defense lawyers based on claims that John Evander Couey, 48,

is mentally retarded and suffers from chronic mental illness. Jurors deliberated

for about one hour.

The final decision on Couey's fate will be made in several weeks by Circuit

Judge Richard Howard, who is not bound by the jury's recommendation but is

required to give it "great weight."

Couey, 48, was convicted last week of taking Jessica in February 2005 from her

bedroom to his trailer about 150 yards away, where he raped and killed her.

Despite an intensive search, the third-grader's body was found in a grave

outside Couey's home, about three weeks after she disappeared.

Jury: Death penalty for

child killer Couey, UT, 15.3.2007,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2007-03-14-couey-sentence_N.htm

California man convicted in Montessori murder case

Tue Mar 13, 2007 8:30PM EDT

Reuters

By Dan Whitcomb

LOS ANGELES (Reuters) - A California car salesman was convicted on Tuesday of

murdering the 15-year-old great-great granddaughter of the Montessori schools

founder, more than three years after the teenager ran away and became a

prostitute.

Jonathan Phong Khanh Tran, 22, was found guilty of murdering Hanna Montessori as

well as raping two teenage girls and sexually assaulting a third. All the girls

were working as prostitutes a few miles from Disneyland.

Tran faces 55 years to life in prison when he is sentenced later this year.

Montessori's mother, Cheryl Ramirez, broke down into sobs as the verdicts were

read in a Santa Ana courtroom.

The murder of Montessori made worldwide headlines, in part because she was not

identified for four months after she was found on January 19, 2004, dying of

massive head wounds in a quiet Southern California neighborhood.

The 15-year-old great-great granddaughter of education pioneer Maria Montessori,

a Nobel Peace Prize nominee, ran away from a Georgia group home in September

2003.

She was cited in Los Angeles three months earlier for loitering, a charge police

often used against suspected prostitutes, but gave officers a false name and was

released.

Family members have said Montessori turned rebellious after her parents divorced

and she moved from Maine to Georgia. She was placed in the group home after

reporting that she had been sexually abused. Neither of her parents were accused

of the abuse.

Prosecutors say Tran, a car salesman, picked up Montessori in his truck under

the pretext of paying her for sex but drove away instead, intending to kidnap

and rape her. She is believed to have jumped from the car, striking her head.

Prosecutors say Tran sexually attacked the other three girls, whose names were

not made public, after picking them up in the same neighborhood.

California man convicted in Montessori murder

case, R, 13.3.2007,

http://www.reuters.com/article/domesticNews/idUSN1319491720070314

Sex Offender

Guilty of Rape and Murder of Florida Girl

March 8, 2007

The New York Times

By TERRY AGUAYO

MIAMI, March 7 — A registered sex offender was convicted here Wednesday in

the kidnapping, rape and murder of a 9-year-old girl who had been buried alive

in plastic bags near the mobile home where he lived.

The case against the defendant, John E. Couey, led to a nationwide crackdown on

sex criminals, and Mr. Couey could face the death penalty.

A 12-member jury deliberated about four hours before finding Mr. Couey guilty of

first-degree murder, burglary, kidnapping and sexual battery in the 2005 attack

on the girl, Jessica Lunsford. Mr. Couey, 48, showed no reaction as the verdict

was read, and Jessica’s father, Mark Lunsford, and her mother, Angela Bryant,

wiped away tears.

In the penalty phase of the trial, which is to begin on Tuesday, the jury will

determine whether Mr. Couey should be executed, as prosecutors are seeking, or

sentenced to life in prison without possibility of parole. The final decision

rests with Judge Richard A. Howard of Circuit Court in Citrus County, but the

jury’s recommendation is heavily considered.

“We’re almost there,” Mr. Lunsford said outside the courthouse after the

verdict. “This is only the first part. We’ve still got the second part.”

Jessica, a third grader, was last seen in February 2005 when she went to bed in

Homosassa, 55 miles north of Tampa, in the house where she lived with her father

and grandparents. She was declared missing the next morning. Her body was found

three weeks later buried in two plastic bags outside the mobile home where Mr.

Couey had lived, just days after he confessed to the crime and directed

investigators to the body.

Because Mr. Couey was not granted a lawyer when he confessed, Judge Howard did

not allow his confession to be used in the trial. But the jury was allowed to

hear from guards at the Citrus County Jail, who testified that Mr. Couey made

incriminating statements to them while at the jail.

The trial was moved 200 miles to Miami to avoid juror exposure to the publicity

surrounding the case. “We had the facts on our side,” a prosecutor, Brad King,

said. “I felt confident that we had an overwhelming amount of facts that we

could present to the jury.”

In the trial, prosecutors showed the jury crucial evidence against Mr. Couey,

including the blood-stained mattress where they said he raped Jessica, the bags

she was buried in and a stuffed dolphin that was in her arms when her body was

found. While on the witness stand, forensic experts discussed evidence collected

from Mr. Couey’s bedroom, including his semen and Jessica’s DNA on the mattress.

The medical examiner who performed Jessica’s autopsy testified that she died of

suffocation, and had poked her fingers through the bags, as if trying to push

through.

The defense presented one witness, a mental health expert who testified that Mr.

Couey, who spent much of his time drawing on a sketch pad during the trial, is

mentally retarded. Defense lawyers maintained that there was no proof that Mr.

Couey had committed the crime and argued that the crime scene had not been

properly secured, causing evidence to be lost.

“It’s up to you to decide what the evidence shows,” Daniel Lewan, Mr. Couey’s

lawyer, told jurors during closing arguments. “Don’t be afraid to disregard what

you don’t trust.”

Mr. Couey had been registered as a sex offender after a 1991 conviction for

exposing and fondling himself in front of a 5-year-old girl, but skipped

counseling sessions and moved without informing parole officers of his

whereabouts. Because of this, many states passed laws in Jessica’s name,

increasing minimum sentences for sexual offenses against children and requiring

offenders to be closely tracked upon release.

Also on Wednesday, the Florida Senate passed Gov. Charlie Crist’s Anti-Murder

Act. It would require probation violators who have committed violent acts to be

held in county jails until a hearing is held to determine whether the violator

is a danger to the community.

“We saw our justice system at work today as John Couey was convicted for his

heinous crimes against one of Florida’s children,” Mr. Crist said in a

statement.

Sex Offender Guilty of

Rape and Murder of Florida Girl, NYT, 8.3.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/08/us/08verdict.html

Doubts Rise as States Hold Sex Offenders After Prison Terms

March 4, 2007

The New York Times

By MONICA DAVEY and ABBY GOODNOUGH

The decision by New York to confine sex offenders beyond their prison terms

places the state at the forefront of a growing national movement that is popular

with politicians and voters. But such programs have almost never met a stated

purpose of treating the worst criminals until they no longer pose a threat.

About 2,700 pedophiles, rapists and other sexual offenders are already being

held indefinitely, mostly in special treatment centers, under so-called civil

commitment programs in 19 states, which on average cost taxpayers four times

more than keeping the offenders in prison.

In announcing a deal with legislative leaders on Thursday, Gov. Eliot Spitzer, a

Democrat, suggested that New York’s proposed civil commitment law would “become

a national model” and go well beyond confining the most violent predators to

also include mental health treatment and intensive supervised release for

offenders.

“No one has a bill like this, nobody,” said State Senator Dale M. Volker, a

Republican from western New York and a leading proponent in the Legislature of

civil confinement.

But in state after state, such expectations have fallen short. The United States

Supreme Court has upheld the constitutionality of the laws in part because their

aim is to furnish treatment if possible, not punish someone twice for the same

crime. Yet only a small fraction of committed offenders have ever completed

treatment to the point where they could be released free and clear.

Leroy Hendricks, a convicted child molester in Kansas, finished his prison term

13 years ago, but he remains locked up at a cost to taxpayers in that state of

$185,000 a year — more than eight times the cost of keeping someone in prison

there.

Mr. Hendricks, who is 72 and unsuccessfully challenged his confinement in the

Supreme Court, spends most days in a wheelchair or leaning on a cane, because of

diabetes, circulation ailments and the effects of a stroke. He may not live long

enough to “graduate” from treatment.

Few ever make such progress: Nationwide, of the 250 offenders released

unconditionally since the first law was passed in 1990, about half of them were

let go on legal or technical grounds unrelated to treatment.

Still, political leaders, like those in New York, are vastly expanding such

programs to keep large numbers of rapists and pedophiles off the streets after

their prison terms in a response to public fury over grisly sex crimes.

In Coalinga, Calif., a $388 million facility will allow the state to greatly

expand the offenders it holds to 1,500. Florida, Minnesota, Nebraska, Virginia

and Wisconsin are also adding beds.

At the federal level, President Bush has signed a law offering money to states

that commit sex offenders beyond their prison terms, and the Justice Department

is creating a civil commitment program for federal prisoners.

Even with the enthusiasm among politicians, an examination by The New York Times

of the existing programs found they have failed in a number of areas:

¶Sex offenders selected for commitment are not always the most violent; some

exhibitionists are chosen, for example, while rapists are passed over. And some

are past the age at which some scientists consider them most dangerous. In

Wisconsin, a 102-year-old who wears a sport coat to dinner cannot participate in

treatment because of memory lapses and poor hearing.

¶The treatment regimens are expensive and largely unproven, and there is no way

to compel patients to participate. Many simply do not show up for sessions on

their lawyers’ advice — treatment often requires them to recount crimes, even

those not known to law enforcement — and spend their time instead gardening,

watching television or playing video games.

¶The cost of the programs is virtually unchecked and growing, with states

spending nearly $450 million on them this year. The annual price of housing a

committed sex offender averages more than $100,000, compared with about $26,000

a year for keeping someone in prison, because of the higher costs for programs,

treatment and supervised freedoms.

¶Unlike prisons and other institutions, civil commitment centers receive little

standard, independent oversight or monitoring; sex among offenders is sometimes

rampant, and, in at least one facility, sex has been reported between offenders

and staff members.

¶Successful treatment is often not a factor in determining the relatively few

offenders who are released; in Iowa, of the nine men let go unconditionally,

none had completed treatment or earned the center’s recommendation for release.

¶Few states have figured out what to do when they do have graduates ready for

supervised release. In California, the state made 269 attempts to find a home

for one released pedophile. In Milwaukee, the authorities started searching in

2003 for a neighborhood for a 77-year-old offender, but have yet to find one.

Supporters of the laws offer no apologies for their shortcomings, insisting that

the money is well spent. Born out of the anguish that followed a handful of

high-profile sex crimes in the 1980s, the laws are proven and potent

vote-getters that have withstood constitutional challenges.

“There has to be a process in place that prevents someone from rejoining society

if they’re still dangerous,” said Jeffrey Klein, a Democratic member of the New

York State Senate who has pushed for civil confinement there.

Martin Andrews, 47, of Woodbridge, Va., who was abducted, buried in a box and

repeatedly sexually assaulted for a week when he was 13, also supports the laws.

“If they can’t control themselves,” Mr. Andrews said, “we need to do it for

them.”

But the myriad problems have concerned some advocates for victims of sexual

abuse, who suggest the money is being wasted and that other options for dealing

with dangerous sex offenders — such as giving them longer prison terms,

preventing sentencing deals with prosecutors and mandating treatment during

incarceration — would be more effective.

“Civil commitment is a huge, huge assignment of resources,“ said Anne Liske, the

former executive director of the New York State Coalition Against Sexual

Assault, a victims’ advocacy group. “This wholesale warehousing — without using

the proper assessment tools and with throwing treatment in when they are not

people who can be treated — has already proven not to be working, so why would

we do it more?”

A Series of Convictions

Leroy Hendricks was a likely candidate for commitment as he prepared to leave a

Kansas prison in 1994.

Mr. Hendricks’s most recent crime, for which he had been convicted a decade

earlier, had been “indecent liberties” with two 13-year-old boys in an

electronics shop where he worked. All told, his convictions left a painful trail

reaching back to 1955: exposing himself to young girls; molesting 7- and

8-year-old boys at a carnival where he was the ride foreman; molesting a

7-year-old girl; playing strip poker with a 14-year-old girl; preying on his own

family members, including a boy with cerebral palsy.

Like Mr. Hendricks was, thousands of soon-to-be-released prisoners are screened

for commitment each year by state corrections departments, prosecutors and

panels. The process varies widely from state to state, as do standards for the

evaluators, but in most states, those recommended for commitment have trials

before judges or juries.

Mr. Hendricks may have sealed his own fate when he testified in 1994 that he

could not “control the urge” to molest when he got “stressed out.” He said his

mother, Violet, had wanted a girl when he was born and had dressed him as one

when he was growing up.

“I sure don’t want to hurt anybody again,” he told the court, but then conceded

that he could not ensure the safety of children in his presence. “The only way

to guarantee that is to die,” he said.

More often, these cases come down to contentious duels between psychologists

over how best to analyze an offender’s history and likelihood of repeating

crimes. In most states, commitment is for an indefinite period, but offenders

are allowed to have their cases reviewed by a court periodically.

The results of the screening process are inconsistent. Some offenders are passed

up for civil confinement, only to commit vicious crimes again; others’ physical

ailments alone make them unlikely repeat predators.

Even though Minnesota prison officials had classified Alfonso Rodriguez Jr., a

convicted rapist, in a category of sex offenders most at risk to commit more

crimes, Mr. Rodriguez went home when his term ended in May 2003. That November,

he kidnapped and killed Dru Sjodin, a North Dakota college student who was

beaten and raped.

Likewise, Jerry Buck Inman was charged with raping and strangling a college

student in South Carolina last June, nine months after his release from a

Florida prison after serving 17 years for rape and other crimes. The authorities

in Florida looked at his records but decided not to seek commitment.

Meanwhile, some prosecutors seek commitment for others convicted of noncontact

crimes like public exposure. In Florida, prosecutors tried unsuccessfully to

civilly commit a man who was imprisoned for driving drunk even though his last

sex arrest was decades earlier.

“The population that is being detained is a very, very mixed group,” said

Richard Wollert, a psychologist in Portland, Ore., who evaluates civilly

committed offenders. “There are cases that are appalling in terms of being kept

in custody at the taxpayers’ expense when there are probably alternative

placements for them.”

Predicting who is likely to commit future sex crimes has become more of a

science over the last decade, but many still find the methods questionable.

Actuarial formulas — akin to the tables used for life insurance — play a central

role in deciding who is dangerous enough to be committed. They calculate

someone’s risk of offending again by looking at factors such as the number of

prior sex offenses and the sex of the victims. Men with male victims are graded

as higher risk, for example, because statistics show they are more often repeat

offenders.

“The danger is that these numbers will blind people,” said Eric Janus, a

professor at William Mitchell College of Law in St. Paul who has challenged

Minnesota’s civil commitment law in court.

Politics and emotion also factor heavily into who gets committed, with decisions

made by elected judges or juries who may be more affected by the raw facts of

someone’s offense history or the public spectacle over their crimes than the dry

science of risk prediction.

“It’s so emotional for them,” said Stephen Watson, an assistant public defender

who represented an offender in Florida. “They don’t even want to hear the

research.”

New Laws Follow Publicized Cases

Earlier in the 20th century, many states had sexual psychopath laws that allowed

them to hospitalize offenders deemed too sick for prison. But by the 1980s most

such laws had been repealed or fallen into disuse.

But a handful of horrific and highly publicized cases in the 1980s and ’90s

spurred lawmakers to act again. Washington State adopted the first civil

commitment law in 1990 after men with predatory histories killed a young woman

in Seattle and sexually mutilated a boy in Tacoma.

After state courts upheld Washington’s law, Kansas, Minnesota and Wisconsin

passed versions in 1994, followed by California in 1996.

Then, in a 5-to-4 decision in 1997, the United States Supreme Court found civil

commitment to be constitutional in Kansas v. Hendricks, the same Mr. Hendricks

still confined in Kansas.

In the ruling, the justices found that a “mental abnormality” like pedophilia

was enough to meet a standard to qualify someone for commitment, not the

different standard of “mental illness” that had been traditionally used. The

court also rejected the notion that civil commitment amounted to double jeopardy

(a second criminal punishment for a single crime) or an ex post facto law (a new

punishment for a past crime), noting that Kansas’s statute was not meant to

punish committed men but, like other acceptable civil commitment statutes,

intended “both to incapacitate and to treat” them therapeutically.

“We have never held that the Constitution prevents a state from civilly

detaining those for whom no treatment is available, but who nevertheless pose a

danger to others,” Justice Clarence Thomas wrote for the majority, later adding,

“By furnishing such treatment, the Kansas Legislature has indicated that

treatment, if possible, is at least an ancillary goal of the act, which easily

satisfies any test for determining that the act is not punitive.”

Since then, state officials, civil liberties advocates and lawyers have wrestled

with exactly what that treatment requirement means.

“There’s no question about it,” Professor Janus of William Mitchell College

said, “it’s a very murky area of the law.”

Since the Hendricks ruling, the courts have indicated that states have “wide

latitude” when it comes to treatment for the civilly confined, meaning that

unsuccessful treatment alone or an untreatable patient would not be enough to

undo the laws.

In 2001, the Supreme Court, in Seling v. Young, decided the case of Andre

Brigham Young, a committed man in Washington State who argued that the

conditions he was being held under were so punitive and the treatment so

inadequate as to amount to a second criminal sentence. The court ruled against

Mr. Young.

A year later, in 2002, the Supreme Court made clear the limits of who may be

committed by states, saying the authorities must prove not just that an offender

is still dangerous and likely to commit more crimes but also that he or she has

a “serious difficulty in controlling behavior.”

Some civil libertarians and prisoner advocates, who still object to the laws,

have not given up on finding a challenge that the Supreme Court might view

favorably. Despite the court rulings, these groups insist civil commitment

amounts to a second sentence for a crime.

Even the look of commitment centers reflects the dichotomy at the core of their

stated reason for being — to lock away dangerous men (only three women are

civilly committed) but also to treat them.

Most of the centers tend to look and feel like prisons, with clanking double

doors, guard stations, fluorescent lighting, cinder-block walls, overcrowded

conditions and tall fences with razor wire around the perimeters.

Bedroom doors are often locked at night, and mail is searched by the staff for

pornography or retail catalogs with pictures of women or children. Most states

put their centers in isolated areas. Washington State’s is on an island three

miles offshore in Puget Sound.

Yet soothing artwork hangs at some centers, and cheerful fliers announce movie

nights and other activities. The residents can wander the grounds and often

spend their time as they please in an effort to encourage their cooperation,

including sunbathing in courtyards and sometimes even ordering pizza for

delivery. The new center in California will have a 20,000-book library,

badminton courts and room for music and art therapy.

Diseases like hepatitis and diabetes are common among the committed, and severe

mental illness — beyond the mental “abnormalities“ described by the Supreme

Court — a scourge. A survey in 2002 found that 12 percent of committed sex

offenders suffered from serious psychiatric problems like schizophrenia and

bipolar disorder.

Most severely mentally ill men cannot participate in sex offender treatment and

receive few services besides medication. Verwayne Alexander, a self-described

paranoid schizophrenic who has been detained at the Florida Civil Commitment

Center since 2003, has sliced himself so many times with razor blades that a

guard often watches him around the clock, lawyers said. Mr. Alexander has sought

unsuccessfully to be moved to a psychiatric hospital.

Those who choose to participate in sex offender treatment spend an average of

less than 10 hours a week doing so, but the hours differ vastly from state to

state. The structure of therapy, too, varies widely, a reflection, perhaps, of

the central question still looming in the field: Can treatment ever really work

for these offenders?

Admitting to previous crimes is a crucial piece of a broad band of treatment,

known as relapse prevention, that is used in at least 15 states and has been the

most widely accepted model for about 20 years.

Some of the institutions, too, devote time to other therapies and activities

that seem to have little bearing on sexual offending. In Pennsylvania, young

residents take classes to improve their health and social habits called

“Athlete’s Foot,” “Lactose Intolerance,” “Male Pattern Baldness,” “Flatulence”

and “Proper Table Manners.”

In California, they can join a Brazilian drum ensemble or classes like “Anger

Management Through Art Therapy” and “Interpersonal Skills Through Mural Making.”

But many of those committed get no treatment at all for sex offending, mainly by

their own choice. In California, three-quarters of civilly committed sex

offenders do not attend therapy. Many say their lawyers tell them to avoid it

because admission of past misdeeds during therapy could make getting out

impossible, or worse, lead to new criminal charges.

For those who decline treatment — sometimes including hundreds of “detainees”

awaiting commitment trials — boredom, resentment and hostility to those in

treatment lead to trouble. Some sneak in drugs, alcohol and cellphones,

sometimes with the help of staff members, or beat up other residents, sometimes

coercing them into having sex.

“There’s rampant sexuality going on in there,” said Natalie Novick Brown, a

psychologist who has evaluated 250 men at Florida’s center.

The people who run civil commitment centers say that a constant, nagging

question hangs over them: How to keep order while not treating argumentative,

sometimes violent offenders like prisoners? The low-level staff members are not

prison guards and tend to be poorly educated, trained and paid. Their job titles

— in Illinois, security therapy aide — reflect the awkward balance they must

achieve between security and therapy.

Because civil commitment centers are neither prisons nor traditional mental

health programs, no specialized oversight body exists. None has been created, in

part because its base of financial support, the 19 civil commitment programs

around the country, would be too small, several experts who study the programs

said. But the need, they said, is urgent.

“They ought to be reviewed by an independent entity with the highest possible

standards,” said Dr. Fred Berlin, founder of the Johns Hopkins Sexual Disorders

Clinic in Baltimore.

Few Signs of Progress

Around the country, relatively few committed sex offenders finish treatment and

are released.

“Every year I go to his hearing, and every year there’s no progress in his

case,” said Armand R. Cingolani III, a lawyer with a client in Pennsylvania who

was committed in 2004 after being adjudicated as a juvenile for sexual assault

on two different minors. “It doesn’t seem that anyone gets better.”

Nearly 3,000 sex offenders have been committed since the first law passed in

1990. In 18 of the 19 states, about 50 have been released completely from

commitment because clinicians or state-appointed evaluators deemed them ready.

Some 115 other people have been sent home because of legal technicalities, court

rulings, terminal illness or old age.

In discharging offenders, Arizona, the remaining state, has been the exception.

That state has fully discharged 81 people; there, the facility’s director said

records were not available to indicate the reason for those discharges.

An additional 189 people have been released with supervision or conditions

(excluding Texas, where there is no commitment center and those committed are

treated only as outpatients). And an additional 68 (including 58 in Arizona) are

in a higher, “transitional” phase of the program, but still technically

committed and often living on state land.

The backlogs have led to an aging population. Inside many facilities,

wheelchairs, walkers, high blood pressure and senility are increasingly

expensive concerns. Florida’s center filled 229 prescriptions for arthritis

medication one recent month, and 300 for blood pressure and other heart

problems.

More than 400 of the men in civil commitment are 60 or older, and a number of

studies indicate a significant drop in the recidivism rate for this group, many

of whom have health problems after years in prison. David Thornton, treatment

director of Wisconsin’s center and an expert on recidivism rates, said the

decline was increasingly well-documented.

The growth of the committed population has become a political quagmire. No

legislator wants to insist on the release of sex offenders, but few are able to

swallow the mounting costs of civil commitment. The costs of aging and sick

offenders, such as Mr. Hendricks in Kansas, are especially high in part because

of their special needs and physical ailments.

From 2001 to 2005, the price of civil commitment in Kansas leapt to nearly $6.9

million from $1.2 million, a state audit there found. “Unless Kansas is willing

to accept a higher level of risk and release more sexual predators from the

program,” the audit said, “few options exist to curb the growth of the program.”

But as more states consider granting some offenders supervised release, the cost

is turning out to be nearly as prohibitive.

For $1.7 million, Washington converted a warehouse in Seattle into a home for

men on conditional release. It has 26 cameras monitoring residents, a dozen

workers, a surveillance booth overseeing the living area and a 1,700-pound

magnetic door.

Two men live there so far.

With the logjams and frustrations mounting, many states have lengthened prison

sentences for sex offenders. Virginia last year increased the minimum sentence

for certain sexual acts against children to 25 years, from 10, though it also

sharply expanded the number of crimes that qualify an offender for civil

commitment.

Ida Ballasiotes, whose daughter’s rape and murder in 1988 helped spur the first

civil commitment law, in Washington State, said that no sexual predator should

walk free and that longer prison sentences should “absolutely” be considered.

“I don’t believe they can be treated, period,” Ms. Ballasiotes said.

After Release, Objections

Even for those sex offenders considered safe enough to be released, going home

is no simple process. Kansas authorities decided two years ago that Mr.

Hendricks, who was the first person that state committed under its law and who

after a decade had progressed to one of the highest phases of treatment, should

be moved from Larned State Hospital to a group home in a community where he

would be watched around the clock.

Mr. Hendricks would not be allowed onto the home’s porch or patio without an

escort, according to court documents. Besides, his medical problems, including

poor hearing and eyesight, meant he could not walk down the 40-yard gravel

driveway outside the house without falling, the documents said.

But as with many men with his history, the community balked. In California, so

many towns object to men leaving civil commitment that some of those released

have to live in trailers outside prisons.

“You can’t just sneak them in,” said John Rodriguez, a recently retired deputy

director in the California Department of Mental Health. “You’ve got hearings,

the court announces it, it’s all over the press.”

In Mr. Hendricks’s case, residents of Lawrence, where he was initially to be

moved, collected petitions. “You can tell me that he’s old, but as long as he

can move his hands and his arms, he can hurt another child,” said Missi Pfeifer,

37, a mother of three who led the petition drive with her two sisters and

mother.

Then officials in Leavenworth County, picked as an alternative, said the choice

violated county zoning laws. Mr. Hendricks lasted two days there, in a house off

a road not far from a pasture of horses, before a judge ordered him removed.

State officials said they had no choice but to move Mr. Hendricks back to a

facility on the grounds of a different state hospital, where he still is.

Through a spokeswoman for the state Department of Social and Rehabilitation

Services, Mr. Hendricks declined to speak to The New York Times.

Two years ago, he told The Lawrence Journal-World that he would be living in a

group home “if somebody hadn’t opened their damn mouth,” adding, “I’m stuck here

till something happens, and I don’t know when that will be.”

Next: Inside the troubled center for sex offenders in Florida.

Doubts Rise as States

Hold Sex Offenders After Prison Terms, NYT, 4.3.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/04/us/04civil.html?_r=1&hp&oref=slogin

By Redd Huber, pool via AFP/Getty Images

Lisa Nowak is escorted to her court appearance in Orlando in this file photo

from February 6.

Nowak is charged with attempted kidnapping after allegedly confronting an Air

Force captain

who she believed to be dating a fellow astronaut.

Astronaut charged with kidnap attempt

UT 2.3.2007

http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2007-03-02-astronaut-charges_x.htm

Astronaut

charged with kidnap attempt

Updated

3/2/2007 1:04 PM ET

AP

USA Today

ORLANDO

(AP) — Florida prosecutors charged an astronaut Friday with trying to kidnap a

romantic rival, but they declined to file an attempted murder charge recommended

by police.

Lisa Nowak, 43, was formally charged almost a month after she was arrested at an

Orlando airport parking lot.

Police have said the Houston mother of three had raced 900 miles in her car from

Texas to Orlando on Feb. 5 to confront a woman she saw as a rival for another

astronaut's affections. She donned a wig and trench coat, then sprayed a

chemical into the woman's car when she wouldn't let Nowak in, police said.

In addition to attempted kidnapping with intent to inflict bodily harm, state

prosecutors charged Nowak on Friday with burglary with a weapon and battery.

A spokesman for Nowak's attorney declined to comment because he hadn't seen the

charges. Nowak is free on bond with an ankle tracking device.

Nowak believed Colleen Shipman was romantically involved with Navy Cmdr. William

Oefelein, a pilot during space shuttle Discovery's trip to the space station

last December, according to police. After the confrontation, Shipman drove to a

parking lot booth for help.

Nowak had been a top astronaut who flew on Discovery last summer and won praise

for operating the shuttle's robotic arm. NASA relieved her of all mission duties

after her arrest.

Astronaut charged with kidnap attempt, UT, 2.3.2007,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2007-03-02-astronaut-charges_x.htm

Scared

Silent

With

Witnesses at Risk, Murder Suspects Go Free

March 1,

2007

The New York Times

By DAVID KOCIENIEWSKI

NEWARK,

Feb. 27 — When Yusef Johnson, a 15-year-old honors student, was killed outside

an apartment complex here so gang-infested it is known as Crazyville, a witness

came forward within days and told the police she knew the man she had seen fire

the fatal shots.

In another case three months later, in November 2005, officers found two people

who identified a street gang leader as the man they saw kill a marijuana dealer

named Valterez Coley during a dispute over a woman.

And when Isaiah Stewart, a 17-year-old wearing an electronic monitoring bracelet

from a recent brush with the law, was gunned down that December, another Newark

teenager sketched a diagram of the crime scene, correctly identified the murder

weapon and named a former classmate as the person he had watched commit the

crime.

They seem like slam-dunk cases, but none of the three suspects have been

arrested. It is not that detectives are unsure of their identity or cannot find

them. Rather, it is because so many recent cases here have been scuttled when

witnesses were scared silent that the Essex County prosecutor has established an

unwritten rule discouraging pursuit of cases that rely on a single witness, and

those in which witness statements are not extensively corroborated by forensic

evidence.

The 3 are among at least 14 recent murders in Newark in which witnesses have

clearly identified the killers but no charges have been filed, infuriating local

police commanders and victims’ relatives.

In 8 of the 14 cases, according to court documents and police reports, there was

more than one witness; in two of them, off-duty police officers were among those

identifying the suspects. But in a DNA era, these are cases with little or no

physical evidence, and they often involve witnesses whose credibility could be

compromised by criminal history or drug problems, or both.

“No one wants to solve these cases and lock up the killers in these cases more

than we do,” the county prosecutor, Paula T. Dow, said in a recent interview.

“But we have to weigh the evidence and move forward only if we believe that the

witnesses are credible and that they’ll be there to testify at trial.”

The tension between the police and prosecutors here over the evolving standards

of evidence required to authorize arrest warrants is a stark example of the

profound effect witness intimidation is having on the criminal justice system in

New Jersey and across the country.

Surveys conducted by the National Youth Gang Center, which is financed by the

federal Department of Justice, have found that 88 percent of urban prosecutors

describe witness intimidation as a serious problem.

In both Baltimore and Boston, where “stop snitching” campaigns by rap artists

and gang leaders have urged city residents not to cooperate with the

authorities, prosecutors estimate that witnesses face some sort of intimidation

in 80 percent of all homicide cases.

In Essex County, prosecutors report that witnesses in two-thirds of their

homicides receive overt threats not to testify, with defendants and their

supporters sometimes canvassing witnesses’ neighborhoods wearing T-shirts

printed with the witnesses’ photographs or distributing copies of their

statements to the police.

Dozens of New Jersey murder cases have been undone over the past five years

after witnesses were killed, disappeared before trial or changed their stories.

In 2004, the Newark police determined that four people found dead in a vacant

lot had been killed to silence a witness to a murder; a witness to that

quadruple homicide was later shot to death as well.

Ms. Dow, who was appointed in 2003 amid criticism of county prosecutors’ ability

to close cases, said she was simply adapting to the evolving code on the

streets, where gang violence and widespread distrust of law enforcement have

deprived prosecutors of one of the legal system’s most crucial components:

dependable witnesses.

The state’s attorney in Baltimore, where witness intimidation is a notorious

problem, has taken an even more rigid stand, refusing to file charges in any

single-witness case without extensive forensic corroboration.

But that approach differs sharply from those of prosecutors in many other urban

areas, like Brooklyn, where the district attorney, Charles J. Hynes, has in

recent years taken to reviewing all single-witness cases personally.

In Newark, where the homicide rate has risen in the past few years, the police,

local politicians and victims’ relatives are all questioning why prosecutors are

holding detectives to a higher standard than the law requires — and letting

dangerous criminals remain on the streets.

“How can they leave him out there?” asked Yusef’s mother, Tosha Braswell,

referring to the man who shot him. “Are they waiting for him to kill someone

else’s son?”

Tension Between Officials

Newark’s mayor, Cory A. Booker, who was elected last year on a promise to reduce

crime in the city, recently met with Ms. Dow to ask her to be more aggressive in

filing charges. In recent years Newark police officials have accused the

prosecutor of being reluctant to take on cases that could be difficult to win

because her office was criticized after losing a succession of high-profile

trials.

The police director, Garry F. McCarthy, worries that the prosecutor’s approach

undermines his crime-fighting strategy of focusing on the small group of

criminals responsible for a disproportionate amount of crime.

“The law states the standard for arrest is probable cause, which is different

than what is required for conviction beyond a reasonable doubt,” Mr. McCarthy

said. “Our goal is to arrest quickly to avoid the potential for additional

crime. An arrest does not prevent an ongoing investigation from proceeding.”

Ms. Dow declined to discuss details of any open cases. But she said that she was

proud of her office’s performance, and that she hoped her rigorous standards for

filing charges would lead investigators to work harder at getting corroboration.

“It’s easy for the police to point fingers when they haven’t done enough

detective work to get a conviction,” she said.

In Essex County, the conviction rate for homicides, which includes plea

agreements, was 79 percent in 2006, up from 74 percent when Ms. Dow took over

three years earlier (but down from 86 percent in 2005 and 83 percent in 2004).

In Baltimore, prosecutors under Patricia C. Jessamy, the state’s attorney,

obtained convictions in 65 percent of homicide cases last year, up from 59

percent in 2005 and 52 percent in 2004.

While prosecutors are often measured by such conviction rates, it is difficult

to tell through statistics whether they are shying from hard-to-win cases.

What most irks the police is the failure to even file charges in cases in which

witnesses have solidly identified a suspect, like the 14 here in Newark over the

past three years in which Ms. Dow has declined to authorize arrest warrants. Six

of these cases rely on a single witness, including the slayings of Yusef Johnson

and Valterez Coley.

Yusef was a football star with a 3.7 grade-point average before he was killed in

August 2005. According to police reports, a woman told detectives she had seen

the shooting from 30 feet away and was well acquainted with the gunman, a member

of the Crips street gang, because he frequently sold cocaine to her.

The case helps illustrate why prosecutors may shy away from single-witness

cases: Given the suspect’s status as both a gang member and the witness’s drug

supplier, even detectives have their doubts about whether the woman would

ultimately testify at trial — or be believed.

On the night Mr. Coley was gunned down near a porch in Newark’s Central Ward,

two men told the police they had seen the gunman, whom they identified as a

leader of the 252 Bloods street gang. The witnesses said the gunman was looking

to settle a score with a young man who had a relationship with his girlfriend,

and mistook Mr. Coley for his rival.

But one of the men soon fled the state, leaving the police with a lone witness —

and thus no charges have been brought.

Danger in Cooperation

Gregory DeMattia, chief of the Essex County prosecutor’s homicide division, said

his investigators saw fallout from witness intimidation every day. When they

arrive at a crime scene, he said, bystanders scatter so neighbors will not think

they are cooperating with the police.

Those who do help often do so surreptitiously — leaving detectives a note in a

trash can or asking to be taken away in handcuffs “so that neighbors will think

they’re in trouble with the police and not cooperating,” Mr. DeMattia said.

Prosecutors in other cities tell similar stories about their witnesses being

pressured, and say they are cautious about pursuing cases based on lone

witnesses because of worries about faulty memory, ulterior motives and, as in

the Yusef Johnson case, credibility.

That is part of why Ms. Jessamy, in Baltimore, has all but refused to file

charges in single-witness situations.

But across Maryland in Prince George’s County, where there is also a serious

gang problem, State’s Attorney Glenn F. Ivey has taken the opposite tack. He

insists on pursuing single-witness cases even though he was criticized publicly

for losing 4 of them in 13 months.

“If you have a single witness and you believe their story, I believe you’ve got

to go forward, even if it’s a case you might lose,” said Mr. Ivey, whose

office’s conviction rate on homicides is more than 80 percent. “I’m not going to

give the gang members, the murderers and the rapists an easy out. And if they

know that all they have to do is get your case down to one witness, I think it

would encourage them to use even more intimidation.” Here in Newark, even in

cases with multiple witnesses — and occasionally even when one of those

witnesses is a police officer — the prosecutor has sometimes been unwilling to

authorize arrests.

Take the case of Lloyd Shears, an Army veteran killed during a robbery in

December. A man told the police he had seen his neighbor fire the fatal shots. A

woman who had been standing next to him told detectives she heard the shots, and

then turned to see the neighbor running from the scene. But the neighbor has not

been charged.

Or consider the killing of Shamid Wallace, an 18-year-old found face down in the

street last August with several gunshot wounds in his torso. Detectives found

two witnesses who identified the man they said they saw kill Mr. Wallace. An

off-duty Newark police officer heard the gunshots, saw a man fleeing with a gun

and later picked the suspect out of a photo array. The suspect has not been

arrested.

Then there is Farad Muhammad, who was stabbed to death last July. One witness

told the police she had seen someone she knew running away from Mr. Muhammad’s

body. An off-duty police officer from neighboring East Orange identified the

same man, saying he had seen the suspect chasing Mr. Muhammad with a knife.

Again, no charges were filed.

Yusef’s parents, who keep a shrine of photographs surrounding his school sports

trophies, still hope that his suspected killer will be arrested soon.

“It’s like they don’t care enough,” said his father, Scottie Edwards, a delivery

truck driver.

Wielding Fear Like a Weapon

But to those who suggest Ms. Dow is overreacting to the problem of witness

intimidation, her supporters point to the death of Steven Edwards, who was shot

and killed in a car on South Eighth Street in January 2006. Within a month,

detectives had three witnesses identifying the gunman.

One of the witnesses, a gang member, quickly announced he would never testify

for fear he would be ostracized for helping the police — or wind up murdered

himself. Six months later, another witness was himself charged in two homicides,

shattering any credibility.

The third witness picked the suspect out of a photo array, but immediately began

to waver when asked about testifying in open court.

“She would not say she was 100 percent sure,” said a police report on the case,

“because she was afraid of retaliation.”

With Witnesses at Risk, Murder Suspects Go Free, NYT,

1.3.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/01/nyregion/01witness.html?hp

|