|

History > 2007 > USA > Constitution, laws

Supreme Court (II)

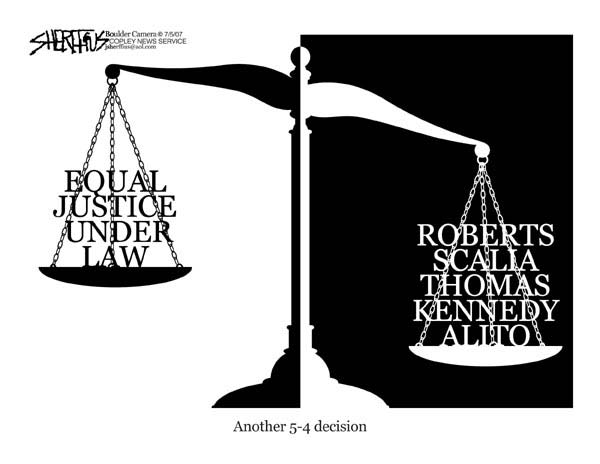

John Sherffius

Boulder

Daily Camera 5.7.2007

Op-Ed Contributor

Stacking the Court

July 26, 2007

The New York Times

By JEAN EDWARD SMITH

Huntington, W.Va.

WHEN a majority of Supreme Court justices adopt a manifestly ideological

agenda, it plunges the court into the vortex of American politics. If the

Roberts court has entered voluntarily what Justice Felix Frankfurter once called

the “political thicket,” it may require a political solution to set it straight.

The framers of the Constitution did not envisage the Supreme Court as arbiter of

all national issues. As Chief Justice John Marshall made clear in Marbury v.

Madison, the court’s authority extends only to legal issues.

When the court overreaches, the Constitution provides checks and balances. In

1805, after persistent political activity by Justice Samuel Chase, Congress

responded with its power of impeachment. Chase was acquitted, but never again

did he step across the line to mingle law and politics. After the Civil War,

when a Republican Congress feared the court might tamper with Reconstruction in

the South, it removed those questions from the court’s appellate jurisdiction.

But the method most frequently employed to bring the court to heel has been

increasing or decreasing its membership. The size of the Supreme Court is not

fixed by the Constitution. It is determined by Congress.

The original Judiciary Act of 1789 set the number of justices at six. When the

Federalists were defeated in 1800, the lame-duck Congress reduced the size of

the court to five — hoping to deprive President Jefferson of an appointment. The

incoming Democratic Congress repealed the Federalist measure (leaving the number

at six), and then in 1807 increased the size of the court to seven, giving

Jefferson an additional appointment.

In 1837, the number was increased to nine, affording the Democrat Andrew Jackson

two additional appointments. During the Civil War, to insure an anti-slavery,

pro-Union majority on the bench, the court was increased to 10. When a Democrat,

Andrew Johnson, became president upon Lincoln’s death, a Republican Congress

voted to reduce the size to seven (achieved by attrition) to guarantee Johnson

would have no appointments.

After Ulysses S. Grant was elected in 1868, Congress restored the court to nine.

That gave Grant two new appointments. The court had just declared

unconstitutional the government’s authority to issue paper currency

(greenbacks). Grant took the opportunity to appoint two justices sympathetic to

the administration. When the reconstituted court convened, it reheard the legal

tender cases and reversed its decision (5-4).

The most recent attempt to alter the size of the court was by Franklin Roosevelt

in 1937. But instead of simply requesting that Congress add an additional

justice or two, Roosevelt’s convoluted scheme fooled no one and ultimately sank

under its own weight.

Roosevelt claimed the justices were too old to keep up with the workload, and

urged that for every justice who reached the age of 70 and did not retire within

six months, the president should be able to appoint a younger justice to help

out. Six of the Supreme Court justices in 1937 were older than 70. But the court

was not behind in its docket, and Roosevelt’s subterfuge was exposed. In the

Senate, the president could muster only 20 supporters.

Still, there is nothing sacrosanct about having nine justices on the Supreme

Court. Roosevelt’s 1937 chicanery has given court-packing a bad name, but it is

a hallowed American political tradition participated in by Republicans and

Democrats alike.

If the current five-man majority persists in thumbing its nose at popular

values, the election of a Democratic president and Congress could provide a

corrective. It requires only a majority vote in both houses to add a justice or

two. Chief Justice John Roberts and his conservative colleagues might do well to

bear in mind that the roll call of presidents who have used this option includes

not just Roosevelt but also Adams, Jefferson, Jackson, Lincoln and Grant.

Jean Edward Smith is the author, most recently, of “F.D.R.”

Stacking the Court, NYT,

26.7.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/26/opinion/26smith.html

Editorial

Justice

Denied

July 5,

2007

The New York Times

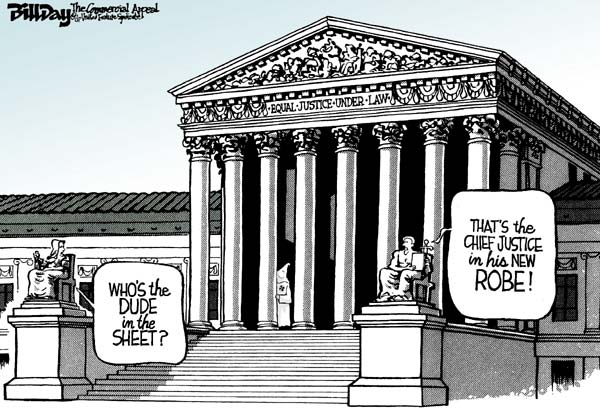

In the

1960s, Chief Justice Earl Warren presided over a Supreme Court that interpreted

the Constitution in ways that protected the powerless — racial and religious

minorities, consumers, students and criminal defendants. At the end of its first

full term, Chief Justice John Roberts’s court is emerging as the Warren court’s

mirror image. Time and again the court has ruled, almost always 5-4, in favor of

corporations and powerful interests while slamming the courthouse door on

individuals and ideals that truly need the court’s shelter.

President Bush created this radical new court with two appointments in quick

succession: Mr. Roberts to replace Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Samuel

Alito to replace the far less conservative Sandra Day O’Connor.

The Roberts court’s resulting sharp shift to the right began to be strongly felt

in this term. It was on display, most prominently, in the school desegregation

ruling last week. The Warren court, and even the Rehnquist court of two years

ago, would have upheld the integration plans that Seattle and Louisville, Ky.,

voluntarily adopted. But the Roberts court, on a 5-4 vote, struck them down,

choosing to see the 14th Amendment’s equal-protection clause — which was adopted

for the express purpose of integrating blacks more fully into society — as a

tool for protecting white students from integration.

On campaign finance, the court handed a major victory to corporations and

wealthy individuals — again by a 5-4 vote — striking down portions of the law

that reined in the use of phony issue ads. The ruling will make it easier for

corporations and lobbyists to buy the policies they want from Congress.

Corporations also won repeatedly over consumers and small stockholders. The

court overturned a jury’s award of $79.5 million in punitive damages against

Philip Morris. The Oregon Supreme Court had upheld the award, calling Philip

Morris’s 40 years of denying the connection between smoking and cancer

“extraordinarily reprehensible.”

In a ruling that will enrich companies at the expense of consumers, the court

overturned — again by a 5-4 vote — a 96-year-old rule that manufacturers cannot

impose minimum prices on retailers.

The flip side of the court’s boundless solicitude for the powerful was its often

contemptuous attitude toward common folks looking for justice. It ruled that an

inmate who filed his appeal within the deadline set by a federal judge was out

of luck, because the judge had given the wrong date — a shockingly unjust

decision that overturned two court precedents on missed deadlines.

When Chief Justice Roberts was nominated, his supporters insisted that he

believed in “judicial modesty,” and that he could not be put into a simple

ideological box. But Justice Alito and he, who voted together in a remarkable 92

percent of nonunanimous decisions, have charted a thoroughly predictable

archconservative approach to the law. Chief Justice Roberts said that he wanted

to promote greater consensus, but he is presiding over a court that is deeply

riven.

In the term’s major abortion case, the court upheld — again by a 5-4 vote — the

federal Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act, even though the court struck down a

nearly identical law in 2000. In the term’s major church-state case, the court

ruled 5-4 that taxpayers challenging the Bush administration’s faith-based

initiatives lacked standing to sue, again reversing well-established precedents.

In a few cases, notably ones challenging the Bush administration’s hands-off

approach to global warming and executions of the mentally ill, Justice Anthony

Kennedy broke with the conservative bloc. But that did not happen often enough.

It has been decades since the most privileged members of society — corporations,

the wealthy, white people who want to attend school with other whites — have had

such a successful Supreme Court term. Society’s have-nots were not the only

losers. The basic ideals of American justice lost as well.

Justice Denied, NYT, 5.7.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/05/opinion/05thu1.html

In Shift, Justices Agree to Review Detainees’ Case

June 30, 2007

The New York Times

By WILLIAM GLABERSON

The United States Supreme Court reversed course yesterday and agreed to hear

claims of Guantánamo detainees that they had a right to challenge their

detention in American courts.

The decision, announced in a brief order released yesterday morning, set the

stage for a legal battle that could shape debates in the Bush administration

about how to close the detention center, which has become a lightning rod for

international criticism.

The order, which required votes from five of the nine justices, rescinded an

April order in which the justices declined to review a federal appeals court

decision that ruled against the detainees.

The court offered no explanation. But the order meant that the justices will

hear the full appeal in their next term, perhaps by December.

The court rarely grants such motions for reconsideration. Some experts on

Supreme Court procedure said they knew of no similar reversal by the court in

decades.

After two Supreme Court decisions since 2004 that have been sweeping setbacks

for the administration’s detention policies, the order yesterday signaled that

the justices had determined to review the issues again.

“Finally, after nearly six years, the Supreme Court is going to rule on the

ultimate question: does the Constitution protect the people detained at

Guantánamo Bay?” said Neal K. Katyal, a Georgetown University law professor who

argued the last Supreme Court case dealing with the Guantánamo detainees. In

that case, decided last June, the justices struck down the administration’s

planned system for war crimes trials of detainees.

The new case sets up a test of one of the central principles of the

administration’s detention policies: that it can hold “enemy combatants” without

allowing them habeas corpus proceedings, which have been used in English and

American law for centuries to challenge the legality of detentions.

The Justice Department declined to comment in any detail on yesterday’s order,

which it had strenuously opposed. “We are disappointed with the decision, but

are confident in our legal arguments and look forward to presenting them before

the court,” said Erik Ablin, a department spokesman.

The administration has argued that permitting habeas corpus suits by foreigners

who are held as enemy combatants outside the United States would paralyze the

military during wartime by giving courts the power to review commanders’

decisions. In response, Congress passed a law last year stripping the federal

courts of the power to hear such habeas corpus cases filed by Guantánamo

detainees.

One issue in the case is whether Congress had the power to enact that law, as a

constitutional provision bars the government from suspending habeas corpus

except in “cases of rebellion or invasion.”

Lawyers for many of the 375 men now held at the naval station in Cuba greeted

the court’s unexpected action with euphoria. “The Supreme Court has taken a

giant step toward ensuring the detainees a day in court,” said David H. Remes, a

Washington lawyer who represents Yemeni detainees at Guantánamo.

Lawyers for detainees had filed some 300 habeas cases, which were working their

way through the courts when Congress passed the law last year. Democrats in

Congress have been pressing to explicitly grant the detainees habeas rights.

Some supporters said yesterday’s decision would increase political pressure for

such a measure, although administration officials have said the president would

probably veto it.

Even so, the court’s decision yesterday could increase momentum within the

administration to find a way to close the Guantánamo detention center. President

Bush and other administration officials have said that they would like to close

it, but the question of where else to hold detainees who are considered too

dangerous to release is a complex one.

Yesterday’s reversal by the Supreme Court suggested that Justice Anthony M.

Kennedy, who opposed hearing the case in April, had changed his position.

Although the vote tally for yesterday’s decision was not released, there have

been indications that Justice Kennedy’s position on this case has been pivotal.

But lawyers said it was not possible to predict how he might eventually vote in

what could be a divisive issue on the court.

Lawyers on both sides of the issue also said the Supreme Court’s review was

likely to focus on the fairness of the military hearings that the administration

has established to determine whether detainees are enemy combatants and should

be detained. In the closed hearings, conducted by what are known as combatant

status review tribunals, detainees are not permitted lawyers and cannot see much

of the evidence against them.

The detainees’ lawyers have said the hearings are sham proceedings that cannot

substitute for reviews by federal judges. On June 22, while the Supreme Court

was considering whether to reconsider its April decision, detainees’ lawyers

filed an affidavit by the first military participant in the hearing process to

criticize secret hearing procedures.

In the affidavit, Stephen E. Abraham, a Reserve military intelligence officer,

described the process of gathering evidence as haphazard and said commanding

officers exerted pressure to have the panels find that detainees were properly

held as enemy combatants.

Although military officials said they disagreed with Mr. Abraham’s

characterizations, lawyers involved in the case said yesterday that the

affidavit might have helped convince some justices that they should more closely

examine the legal procedures at Guantánamo. In the case now before the Supreme

Court, the federal appeals court in Washington in February upheld the law that

stripped federal judges of authority to review foreign prisoners’ challenges to

their detention at Guantánamo Bay.

In the case, Boumediene v. Bush, a divided three-judge panel of the United

States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit found that the 2006

law did not violate the constitutional provision that bars the government from

suspending habeas corpus.

Two of the three appeals court judges said the right of habeas corpus did not

extend to foreign citizens detained outside the United States. In fighting the

effort to get the Supreme Court to review that decision, the administration

argued that habeas corpus rights “would not extend to aliens detained at

Guantánamo Bay as enemy combatants.”

The Supreme Court twice before had faced similar questions, and had ruled in

2004 that federal courts did have jurisdiction to hear Guantánamo detainees’

cases.

Last June, the court said the administration’s plan to try some of the

Guantánamo detainees in military commissions was invalid and struck it down.

Language in the justices’ statements accompanying the April order had suggested

maneuvering among them on whether or when they should again get involved in the

tangled legal questions presented by Guantánamo.

A statement “respecting the denial” of the detainees’ requests in April was

signed jointly by Justices Kennedy and John Paul Stevens. It said the detainees

had to contest findings of the military hearings in the federal appeals court in

Washington, as provided by Congress, before going to the Supreme Court.

But the April statement also said the Supreme Court would be open to a renewed

appeal if it turned out that “the government has unreasonably delayed

proceedings” or subjected the detainees to “some other and ongoing injury.”

In Shift, Justices Agree

to Review Detainees’ Case, NYT, 30.6.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/30/washington/30scotus.html?hp

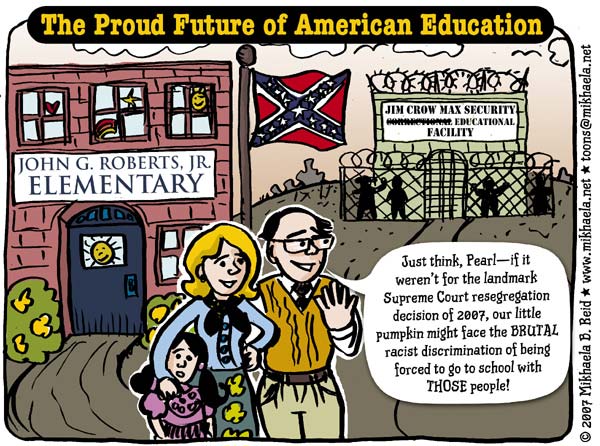

Mikhaela Reid Cagle

28.6.2007

Editorial

Resegregation Now

June 29,

2007

The New York Times

The Supreme

Court ruled 53 years ago in Brown v. Board of Education that segregated

education is inherently unequal, and it ordered the nation’s schools to

integrate. Yesterday, the court switched sides and told two cities that they

cannot take modest steps to bring public school students of different races

together. It was a sad day for the court and for the ideal of racial equality.

Since 1954, the Supreme Court has been the nation’s driving force for

integration. Its orders required segregated buses and public buildings, parks

and playgrounds to open up to all Americans. It wasn’t always easy: governors,

senators and angry mobs talked of massive resistance. But the court never

wavered, and in many of the most important cases it spoke unanimously.

Yesterday, the court’s radical new majority turned its back on that proud

tradition in a 5-4 ruling, written by Chief Justice John Roberts. It has been

some time since the court, which has grown more conservative by the year, did

much to compel local governments to promote racial integration. But now it is

moving in reverse, broadly ordering the public schools to become more

segregated.

Justice Anthony Kennedy, who provided the majority’s fifth vote, reined in the

ruling somewhat by signing only part of the majority opinion and writing

separately to underscore that some limited programs that take race into account

are still acceptable. But it is unclear how much room his analysis will leave,

in practice, for school districts to promote integration. His unwillingness to

uphold Seattle’s and Louisville’s relatively modest plans is certainly a

discouraging sign.

In an eloquent dissent, Justice Stephen Breyer explained just how sharp a break

the decision is with history. The Supreme Court has often ordered schools to use

race-conscious remedies, and it has unanimously held that deciding to make

assignments based on race “to prepare students to live in a pluralistic society”

is “within the broad discretionary powers of school authorities.”

Chief Justice Roberts, who assured the Senate at his confirmation hearings that

he respected precedent, and Brown in particular, eagerly set these precedents

aside. The right wing of the court also tossed aside two other principles they

claim to hold dear. Their campaign for “federalism,” or scaling back federal

power so states and localities have more authority, argued for upholding the

Seattle and Louisville, Ky., programs. So did their supposed opposition to

“judicial activism.” This decision is the height of activism: federal judges

relying on the Constitution to tell elected local officials what to do.

The nation is getting more diverse, but by many measures public schools are

becoming more segregated. More than one in six black children now attend schools

that are 99 to 100 percent minority. This resegregation is likely to get

appreciably worse as a result of the court’s ruling.

There should be no mistaking just how radical this decision is. In dissent,

Justice John Paul Stevens said it was his “firm conviction that no Member of the

Court that I joined in 1975 would have agreed with today’s decision.” He also

noted the “cruel irony” of the court relying on Brown v. Board of Education

while robbing that landmark ruling of much of its force and spirit. The citizens

of Louisville and Seattle, and the rest of the nation, can ponder the majority’s

kind words about Brown as they get to work today making their schools, and their

cities, more segregated.

Resegregation Now, NYT, 29.6.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/29/opinion/29fri1.html

Bill Day The Commercial

Appeal Memphis, Tennessee

2.7.2007

Op-Ed

Contributor

Don’t

Mourn Brown v. Board of Education

June 29,

2007

The New York Times

By JUAN WILLIAMS

Washington

LET us now praise the Brown decision. Let us now bury the Brown decision.

With yesterday’s Supreme Court ruling ending the use of voluntary schemes to

create racial balance among students, it is time to acknowledge that Brown’s

time has passed. It is worthy of a send-off with fanfare for setting off the

civil rights movement and inspiring social progress for women, gays and the

poor. But the decision in Brown v. Board of Education that focused on outlawing

segregated schools as unconstitutional is now out of step with American

political and social realities.

Desegregation does not speak to dropout rates that hover near 50 percent for

black and Hispanic high school students. It does not equip society to address

the so-called achievement gap between black and white students that mocks

Brown’s promise of equal educational opportunity.

And the fact is, during the last 20 years, with Brown in full force, America’s

public schools have been growing more segregated — even as the nation has become

more racially diverse. In 2001, the National Center for Education Statistics

reported that the average white student attends a school that is 80 percent

white, while 70 percent of black students attend schools where nearly two-thirds

of students are black and Hispanic.

By the early ’90s, support in the federal courts for the central work of Brown —

racial integration of public schools — began to rapidly expire. In a series of

cases in Atlanta, Oklahoma City and Kansas City, Mo., frustrated parents, black

and white, appealed to federal judges to stop shifting children from school to

school like pieces on a game board. The parents wanted better neighborhood

schools and a better education for their children, no matter the racial make-up

of the school. In their rulings ending court mandates for school integration,

the judges, too, spoke of the futility of using schoolchildren to address social

ills caused by adults holding fast to patterns of residential segregation by

both class and race.

The focus of efforts to improve elementary and secondary schools shifted to

magnet schools, to allowing parents the choice to move their children out of

failing schools and, most recently, to vouchers and charter schools. The federal

No Child Left Behind plan has many critics, but there’s no denying that it is an

effective tool for forcing teachers’ unions and school administrators to take

responsibility for educating poor and minority students.

It was an idealistic Supreme Court that in 1954 approved of Brown as a

race-conscious policy needed to repair the damage of school segregation and

protect every child’s 14th-Amendment right to equal treatment under law. In

1971, Chief Justice Warren Burger, writing for a unanimous court still embracing

Brown, said local school officials could make racial integration a priority even

if it did not improve educational outcomes because it helped “to prepare

students to live in a pluralistic society.”

But today a high court with a conservative majority concludes that any policy

based on race — no matter how well intentioned — is a violation of every child’s

14th-Amendment right to be treated as an individual without regard to race.

We’ve come full circle.

In 1990, after months of interviews with Justice Thurgood Marshall, who had been

the lead lawyer for the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense Fund on the Brown case, I sat

in his Supreme Court chambers with a final question. Almost 40 years later, was

he satisfied with the outcome of the decision? Outside the courthouse, the

failing Washington school system was hypersegregated, with more than 90 percent

of its students black and Latino. Schools in the surrounding suburbs, meanwhile,

were mostly white and producing some of the top students in the nation.

Had Mr. Marshall, the lawyer, made a mistake by insisting on racial integration

instead of improvement in the quality of schools for black children?

His response was that seating black children next to white children in school

had never been the point. It had been necessary only because all-white school

boards were generously financing schools for white children while leaving black

students in overcrowded, decrepit buildings with hand-me-down books and

underpaid teachers. He had wanted black children to have the right to attend

white schools as a point of leverage over the biased spending patterns of the

segregationists who ran schools — both in the 17 states where racially separate

schools were required by law and in other states where they were a matter of

culture.

If black children had the right to be in schools with white children, Justice

Marshall reasoned, then school board officials would have no choice but to

equalize spending to protect the interests of their white children.

Racial malice is no longer the primary motive in shaping inferior schools for

minority children. Many failing big city schools today are operated by black

superintendents and mostly black school boards.

And today the argument that school reform should provide equal opportunity for

children, or prepare them to live in a pluralistic society, is spent. The

winning argument is that better schools are needed for all children — black,

white, brown and every other hue — in order to foster a competitive workforce in

a global economy.

Dealing with racism and the bitter fruit of slavery and “separate but equal”

legal segregation was at the heart of the court’s brave decision 53 years ago.

With Brown officially relegated to the past, the challenge for brave leaders now

is to deliver on the promise of a good education for every child.

Juan Williams, a senior correspondent for NPR and a political analyst for Fox

News Channel, is the author of “Enough: The Phony Leaders, Dead-End Movements

and Culture of Failure That Are Undermining Black America.”

Don’t Mourn Brown v. Board of Education, NYT, 29.6.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/29/opinion/29williams.html

Justices

Limit the Use of Race

in Integration Programs

June 29,

2007

The New York Times

By LINDA GREENHOUSE

WASHINGTON,

June 28 — With competing blocs of justices claiming the mantle of Brown v. Board

of Education, a bitterly divided Supreme Court declared Thursday that public

school systems cannot seek to achieve or maintain integration through measures

that take explicit account of a student’s race.

Voting 5 to 4, the court, in an opinion by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr.,

invalidated programs in Seattle and metropolitan Louisville, Ky., that sought to

maintain school-by-school diversity by limiting transfers on the basis of race

or using race as a “tiebreaker” for admission to particular schools.

Both programs had been upheld by lower federal courts and were similar to plans

in place in hundreds of school districts around the country. Chief Justice

Roberts said such programs were “directed only to racial balance, pure and

simple,” a goal he said was forbidden by the Constitution’s guarantee of equal

protection.

“The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating

on the basis of race,” he said. His side of the debate, the chief justice said,

was “more faithful to the heritage of Brown,” the landmark 1954 decision that

declared school segregation unconstitutional. “When it comes to using race to

assign children to schools, history will be heard,” he said. [News analysis,

Page A24; excerpts, Page A25.]

The decision came on the final day of the court’s 2006-7 term, which showed an

energized conservative majority in control across many areas of the court’s

jurisprudence.

Chief Justice Roberts’s control was not quite complete, however. While Justices

Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas and Samuel A. Alito Jr. joined his opinion on

the schools case in full, the fifth member of the majority, Justice Anthony M.

Kennedy, did not. Justice Kennedy agreed that the two programs were

unconstitutional. But he was highly critical of what he described as the chief

justice’s “all-too-unyielding insistence that race cannot be a factor in

instances when, in my view, it may be taken into account.”

In a separate opinion that could shape the practical implications of the

decision and provide school districts with guidelines for how to create systems

that can pass muster with the court, Justice Kennedy said achieving racial

diversity, “avoiding racial isolation” and addressing “the problem of de facto

resegregation in schooling” were “compelling interests” that a school district

could constitutionally pursue as long as it did so through programs that were

sufficiently “narrowly tailored.”

The four justices were “too dismissive” of the validity of these goals, Justice

Kennedy said, adding that it was “profoundly mistaken” to read the Constitution

as requiring “that state and local school authorities must accept the status quo

of racial isolation in schools.”

As a matter of constitutional doctrine and practical impact, Justice Kennedy’s

opinion thus placed a significant limitation on the full reach of the other four

justices’ embrace of a “colorblind Constitution” under which all racially

conscious government action, no matter how benign or invidious its goal, is

equally suspect.

How important a limitation Justice Kennedy’s opinion proves to be may become

clear only with time, as school districts devise and defend plans that appear to

meet his test.

Among the measures that Justice Kennedy said would be acceptable were the

drawing of school attendance zones, “strategic site selection of new schools,”

and directing resources to special programs. These would be permissible even if

adopted with a consciousness of racial demographics, Justice Kennedy said,

because in avoiding the labeling and sorting of individual children by race they

would satisfy the “narrow tailoring” required to meet the equal protection

demands of the 14th Amendment.

Justice Stephen G. Breyer, who wrote the principal dissenting opinion, was

dismissive of Justice Kennedy’s proposed alternatives and asserted that the

court was taking a sharp and seriously mistaken turn.

Speaking from the bench for more than 20 minutes, Justice Breyer made his points

to a courtroom audience that had never seen the coolly analytical justice

express himself with such emotion. His most pointed words, in fact, appeared

nowhere in his 77-page opinion.

“It is not often in the law that so few have so quickly changed so much,”

Justice Breyer said.

In his written opinion, Justice Breyer said the decision was a “radical” step

away from settled law and would strip local communities of the tools they need,

and have used for many years, to prevent resegregation of their public schools.

Predicting that the ruling would “substitute for present calm a disruptive round

of race-related litigation,” he said, “This is a decision that the court and the

nation will come to regret.”

Justices John Paul Stevens, David H. Souter and Ruth Bader Ginsburg signed

Justice Breyer’s opinion. Justice Stevens wrote a dissenting opinion of his own,

as pointed as it was brief.

He said the chief justice’s invocation of Brown v. Board of Education was “a

cruel irony” when the opinion in fact “rewrites the history of one of this

court’s most important decisions” by ignoring the context in which it was issued

and the Supreme Court’s subsequent understanding of it to permit voluntary

programs of the sort that were now invalidated.

“It is my firm conviction that no member of the court that I joined in 1975

would have agreed with today’s decision,” Justice Stevens said. He did not

mention, nor did he need to, that one of the justices then was William H.

Rehnquist, later the chief justice, for whom Chief Justice Roberts once worked

as a law clerk.

Justice Clarence Thomas was equally pointed and equally personal in an opinion

concurring with the majority.

“If our history has taught us anything,” Justice Thomas said, “it has taught us

to beware of elites bearing racial theories.” He added in a footnote, “Justice

Breyer’s good intentions, which I do not doubt, have the shelf life of Justice

Breyer’s tenure.”

The justices had been wrestling for over a year with the two cases. It was in

January 2006 that parents who objected to the Louisville and Seattle programs

filed their Supreme Court appeals from the lower court decisions that had upheld

the programs.

The Louisville case was Meredith v. Jefferson County Board of Education, No.

05-915, filed by the mother of a student who was denied a transfer to his chosen

kindergarten class because the school he wanted to leave needed to keep its

white students to stay within the program’s racial guidelines.

The Seattle case, Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School

District No. 1, No. 05-908, was filed by a group of parents who had formed a

nonprofit corporation to fight the city’s high school assignment plan.

Because a single Supreme Court opinion resolved both cases, the decision carries

only the name of the Seattle case, which had the lower docket number.

The appeals provoked a long internal struggle over how the court should respond.

Months earlier, when Justice Sandra Day O’Connor was still on the court, the

justices had denied review in an appeal challenging a similar program in

Massachusetts. With no disagreement among the federal appellate circuits on the

validity of such programs, the new appeals did not meet the criterion the court

ordinarily uses to decide which cases to hear. It was June of last year before

the court, reconfigured by the additions of Chief Justice Roberts and Justice

Alito, announced, over the unrecorded but vigorous objection of the liberal

justices, that it would hear both appeals.

By the time the court ruled on Thursday, there was little suspense over what the

outcome would be. Not only the act of accepting the appeals, but also the tenor

of the argument on Dec. 4, gave clear indications that the justices were on

course to strike down both plans.

The cases were by far the oldest on the docket by the time they were decided;

the other decisions the court announced on Thursday were in cases that were

argued in March and April. What consumed the court during the seven months the

cases were under consideration, it appears likely, was an effort by each side to

edge Justice Kennedy closer to its point of view.

While it is hardly uncommon to find Justice Kennedy in the middle of the court,

his position there this time carried a special resonance. He holds the seat once

occupied by Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. who, 29 years ago to the day, announced

his separate opinion in the Bakke case. That solitary opinion, rejecting quotas

but accepting diversity as a rationale for affirmative action in university

admissions, defined the law for the next 25 years, until the decision was

refined and to some degree strengthened in the University of Michigan Law School

decision.

Justice Kennedy was a dissenter from that 2003 decision. But, surprisingly, he

cited it on Thursday, invoking it to rebut the argument that the Constitution

must be always be, regardless of context or circumstance, colorblind.

Justices Limit the Use of Race in Integration Programs,

NYT, 29.6.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/29/washington/29scotus.html?hp

News

Analysis

The Same

Words, but Differing Views

June 29,

2007

The New York Times

By ADAM LIPTAK

The five

opinions that made up yesterday’s decision limiting the use of race in assigning

students to public schools referred to Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark

1954 school desegregation case, some 90 times. The justices went so far as to

quote from the original briefs in the case and from the oral argument in 1952.

All of the justices on both sides of yesterday’s 5-to-4 decision claimed to be,

in Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr.’s phrase, “faithful to the heritage of

Brown.”

But lawyers who represented the black schoolchildren in the Brown case said

yesterday that several justices in the majority had misinterpreted the positions

they had taken in the litigation and had misunderstood the true meaning of

Brown.

And as those reactions make clear, yesterday’s decision has reignited a societal

debate about the role of race in education that will almost certainly prompt

divisive lawsuits around the country. Indeed, the decision has invited a

fundamental reassessment of Brown itself, perhaps the most important Supreme

Court decision of the 20th century.

“There is a historic clash between two dramatically different visions not only

of Brown,” said Laurence H. Tribe, a law professor at Harvard, “but also the

meaning of the Constitution.”

The four conservatives on the court said Brown and the 14th Amendment’s equal

protection clause required the government to be colorblind in making decisions

about placing students in public schools in all circumstances. The four liberals

said Brown meant to allow school districts to take account of race to achieve

integration.

In the middle was Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, whose concurring opinion, at once

idiosyncratic, enigmatic and decisive, was perhaps the least engaged with Brown,

saying little more than that the case “should teach us that the problem before

us defies” an “easy solution.” Justice Kennedy’s concurrence, which split the

court 4-1-4 on a crucial point, sharply limited the role race could play in

school assignments but did not forbid school districts from taking account of

race entirely.

Charles J. Ogletree Jr., a law professor at Harvard and an authority on Brown

and its aftermath, applauded that concurrence. “The hidden story in the decision

today is that Justice Kennedy refused to follow the lead of the other four

justices in eviscerating the legacy of Brown,” Professor Ogletree said.

Writing for the other four justices in the majority, Chief Justice Roberts took

a harder line. In an unusual effort to cement his interpretation of Brown, he

quoted from the transcript of the 1952 argument in the case.

“We have one fundamental contention,” a lawyer for the schoolchildren, Robert L.

Carter, had told the court more than a half-century ago. “No state has any

authority under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to use

race as a factor in affording educational opportunities among its citizens.”

Chief Justice Roberts added yesterday, “There is no ambiguity in that

statement.”

But the man who made that statement, now a 90-year-old senior federal judge in

Manhattan, disputed the chief justice’s characterization in an interview

yesterday.

“All that race was used for at that point in time was to deny equal opportunity

to black people,” Judge Carter said of the 1950s. “It’s to stand that argument

on its head to use race the way they use is now.”

Jack Greenberg, who worked on the Brown case for the plaintiffs and is now a law

professor at Columbia, called the chief justice’s interpretation “preposterous.”

“The plaintiffs in Brown were concerned with the marginalization and subjugation

of black people,” Professor Greenberg said. “They said you can’t consider race,

but that’s how race was being used.”

William T. Coleman Jr., another lawyer who worked on Brown, said, “The majority

opinion is 100 percent wrong.”

“It’s dirty pool,” said Mr. Coleman, a Washington lawyer who served as secretary

of transportation in the Ford administration, “to say that the people Brown was

supposed to protect are the people it’s now not going to protect.”

But Roger Clegg, the president and general counsel of the Center for Equal

Opportunity, a research group in the Washington area that supports colorblind

government policies, disagreed, saying the majority honored history in

yesterday’s decision.

“There is no question but that the principle of Brown is that a child’s skin

color should not determine what school he or she should be assigned to,” Mr.

Clegg said.

Chief Justice Roberts wrote that Brown not only supported but also required

yesterday’s decision striking down student assignment plans in Seattle and

Louisville, Ky., meant to ensure racially balanced schools.

Justice John Paul Stevens, in dissent, said Chief Justice Roberts’s discussion

of Brown “rewrites the history of one of this court’s most important decisions.”

Justice Stephen G. Breyer, also dissenting, said the opinion “undermines Brown’s

promise of integrated primary and secondary education” and “threatens to

substitute for present calm a disruptive round of race-related litigation.”

Professor Greenberg said he was also wary of the reaction to yesterday’s

decision. “Following Brown, there was massive resistance” that lasted some 15

years, he said. “This is essentially the rebirth of massive resistance in more

acceptable form.”

Mr. Clegg, by contrast, said the decision’s practical consequences should be

minimal. “Kennedy does leave the door open to some degree of consideration of

race,” he said, “but it’s not very clear what that would be.”

As a consequence, Mr. Clegg said, most prudent school districts would shy from

any use of race in assigning students for fear of costly and disruptive

litigation.

Professor Greenberg suggested that more than law was at play in yesterday’s

decision.

“You can’t really say that five justices are so smart that they can read the law

and precedents and four others can’t,” he said. “Something else is going on.”

Steven Greenhouse contributed reporting.

The Same Words, but Differing Views, NYT, 29.6.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/29/us/29assess.html

Century-Old Ban

Lifted on Minimum Retail Pricing

June 29,

2007

The New York Times

By STEPHEN LABATON

WASHINGTON,

June 28 — Striking down an antitrust rule nearly a century old, the Supreme

Court ruled on Thursday that it was not automatically unlawful for manufacturers

and distributors to agree on minimum retail prices.

The decision will give producers significantly more, though not unlimited, power

to dictate retail prices and to restrict the flexibility of discounters.

Five justices, agreeing with the nation’s major manufacturers, said the new rule

could in some instances lead to more competition and better service. But four

dissenting justices agreed with 37 states and some consumer groups that

abandoning the old rule could result in significantly higher prices and less

competition for consumer and other goods.

The court struck down the 96-year-old rule that resale price maintenance

agreements were an automatic, or per se, violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act.

In its place, the court instructed judges considering such agreements for

possible antitrust violations to apply a case-by-case approach, known as a “rule

of reason,” to assess their impact on competition. The new rule is considerably

more favorable to defendants.

The decision was handed down on the last day of the court’s term, which has been

notable for overturning precedents and for victories for big businesses and

antitrust defendants. It was also the latest of a series of antitrust decisions

in recent years rejecting per se rules that had prohibited various marketing

agreements between companies.

The Bush administration, along with economists of the Chicago school, had argued

that the blanket prohibition against resale price maintenance agreements was

archaic and counterproductive because, they said, some resale price agreements

actually promote competition.

For example, they said, such agreements can make it easier for a new producer by

assuring retailers that they will be able to recoup their investments in helping

to market the product. And some distributors would be unfairly harmed by others,

like Internet-based retailers, which could offer discounts because they would

not have the expense of product demonstrations or other specialized consumer

services.

A majority of the court agreed that the flat ban on price agreements discouraged

these services and other marketing practices that could promote competition.

“In sum, it is a flawed antitrust doctrine that serves the interests of lawyers

— by creating legal distinctions that operate as traps for the unaware — more

than the interests of consumers — by requiring manufacturers to choose

second-best options to achieve sound business objectives,” the court said in an

opinion written by Justice Anthony M. Kennedy and signed by Chief Justice John

G. Roberts Jr. and Justices Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas and Samuel A. Alito

Jr.

But in his dissent, portions of which he read from the bench, Justice Stephen G.

Breyer said that there was no compelling reason to overturn a century’s worth of

Supreme Court decisions that had affirmed the prohibition on resale maintenance

agreements.

“The only safe predictions to make about today’s decision are that it will

likely raise the price of goods at retail and that it will create considerable

legal turbulence as lower courts seek to develop workable principles,” he wrote.

“I do not believe that the majority has shown new or changed conditions

sufficient to warrant overruling a decision of such long standing.”

During a 38-year period from 1937 to 1975 that Congress permitted the states to

adopt laws allowing retail price fixing, economists estimated that such

agreements covered about 10 percent of consumer good purchases. In today’s

dollars, Justice Breyer estimated that the agreements translated to a higher

annual average bill for a family of four of about $750 to $1,000.

The dissent was signed by Justices John Paul Stevens, David H. Souter and Ruth

Bader Ginsburg.

The case involved an appeal of a judgment of $1.2 million against Leegin

Creative Leather Products after it cut off Kay’s Kloset, a suburban Dallas shop,

for refusing to honor Leegin’s no-discount policy. The judgment was

automatically tripled under antitrust law.

Leegin’s marketing strategy for finding a niche in the highly competitive world

of small leather goods was to sell its “Brighton” line of fashion accessories

through small boutiques that could offer personalized service. Retailers were

required to accept a no-discounting policy.

After the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, in New Orleans,

upheld the judgment and said it was bound by Supreme Court precedent, Leegin

took the case to the Supreme Court. Unless it is settled, the case, Leegin

Creative Leather Products v. PSK Inc., will now be sent down to a lower court to

apply the new standard.

The Supreme Court adopted the flat ban on resale price agreements between

manufacturers and retailers in 1911, when it found that the Dr. Miles Medical

Company had violated the Sherman act. The company had sought to sell medicine

only to distributors who agreed to resell them at set prices. The court said

such agreements benefit only the distributors, not consumers, and set a per se

rule making such agreements unlawful.

Justice Kennedy said Thursday that the court was not bound by the 1911 precedent

because of the “widespread agreement” among economists that resale price

maintenance agreements can promote competition.

“Vertical agreements establishing minimum resale prices can have either

pro-competitive or anticompetitive effects, depending upon the circumstances in

which they are formed,” he wrote.

But Justice Breyer said in his dissent that the court had failed to justify the

overturning of the rule, or that there was significant evidence to show that

price agreements would often benefit consumers. He said courts would have a

difficult time sorting out the price agreements that help consumers from those

that harm them.

“The upshot is, as many economists suggest, sometimes resale price maintenance

can prove harmful, sometimes it can bring benefits,” he wrote. “But before

concluding that courts should consequently apply a rule of reason, I would ask

such questions as, how often are harms or benefits likely to occur? How easy is

it to separate the beneficial sheep from the antitrust goats?”

“My own answer,” he concluded, “is not very easily.”

Century-Old Ban Lifted on Minimum Retail Pricing, NYT,

29.6.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/29/washington/29bizcourt.html?hp

Justices

Block Execution of Delusional Killer

June 29,

2007

The New York Times

By RALPH BLUMENTHAL

HOUSTON,

June 28 — Amplifying its ban against execution of the insane, a closely divided

United States Supreme Court on Thursday overturned the death sentence of a

delusional Texas murderer who insisted that he was being punished for preaching

the Gospel.

In a rebuke to lower courts, the justices ruled 5 to 4 that the defendant, Scott

Louis Panetti, had not been shown to have sufficient understanding of why he was

to be put to death for gunning down his wife’s parents in 1992.

The court, acting on the last day of the 2006-7 term, declined to lay out a new

standard for competency in capital cases. But it found that existing protections

had not been afforded.

Justice Anthony M. Kennedy provided the swing vote, joined by the court’s

liberal wing: Justices John Paul Stevens, David H. Souter, Ruth Bader Ginsburg

and Stephen G. Breyer.

The justices referred the case back to a federal district court to re-evaluate

Mr. Panetti’s claims of insanity. They said the district court, Texas courts and

the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, in New Orleans, had

all failed to assess those claims properly.

In a stinging dissent, Justice Clarence Thomas called the ruling “a half-baked

holding that leaves the details of the insanity standard for the district court

to work out.” He was joined in the minority by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr.

and Justices Antonin Scalia and Samuel A. Alito Jr.

Gregory W. Wiercioch, a staff lawyer for the Texas Defender Service who argued

Mr. Panetti’s appeal before the justices in April, hailed the decision as

“reaffirming and strengthening the grounds for proving incompetence” and said it

“put the bite back into a standard that the Fifth Circuit had rendered

essentially meaningless.”

Larry Cox, executive director of Amnesty International USA, said, “The Supreme

Court has taken a much-needed step toward a more humane America.”

But the solicitor general of Texas, Ted Cruz, who had defended the sentence

before the court, said the state would continue to seek Mr. Panetti’s execution.

“Unfortunately, today’s 5-to-4 decision will invite abuse from capital

murderers, subject the courts to numerous false claims of incompetency and even

further delay justice for the victims’ families,” Mr. Cruz said.

“Texas,” he added, “will now return for further proceedings” in the lower

courts, “where we will continue working to carry out the jury’s unanimous

capital sentence for Scott Louis Panetti’s premeditated double homicide.”

Mr. Panetti, 49, is on death row in the East Texas town of Livingston. He has

won periodic delays of execution — he came within a day of being put to death by

lethal injection in 2004 — but court decisions against his appeals have added to

protests against capital punishment in Texas, where 397 people, more than in any

other state, have been executed since the Supreme Court allowed resumption of

the death penalty in 1976.

A schizophrenic who served as his own lawyer in court and mounted an often

incoherent defense, Mr. Panetti claimed that his body had been taken over by an

alter ego he called Sarge Ironhorse and that demons were bent on killing him for

his Christian beliefs.

In a prison interview last November, Mr. Panetti, clutching verses from

Scripture, declared, “The Devil has been trying to rub me out to keep me from

preaching.” He tried to strip off his prison uniform to show scars from burns

that he said John F. Kennedy healed with coconut milk after the sinking of

Kennedy’s torpedo boat in the Pacific in World War II.

In April, the Supreme Court narrowly reversed three other Texas death sentences

as contrary to its evolving jurisprudence on capital punishment. As in those

cases, Thursday’s ruling found reversible error by Texas courts and the Fifth

Circuit.

In 1986, the Supreme Court ruled in Ford v. Wainwright that the Constitution

barred the execution of the mentally ill. But the standard for determining

competency was not laid out beyond Justice Lewis F. Powell’s concurring opinion

that the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment required that a

defendant who is to be executed be able to recognize the relationship between

his crime and his sentence.

The Fifth Circuit found that Mr. Panetti had a minimal understanding of the

connection. But the justices said that he was so delusional that a minimal

understanding was not sufficient, and that he had been denied opportunities for

fully presenting his case for insanity.

The trial court that sentenced him “failed to provide the procedures to which

petitioner was entitled under the Constitution,” the majority said, calling the

procedures that the court did provide “so deficient that they cannot be

reconciled with any reasonable interpretation of the ‘Ford rule.’ ”

The Panetti case has a long and tangled history dating from the day 15 years ago

when Mr. Panetti shaved his head, donned combat fatigues and, in front of his

estranged wife and their 3-year-old daughter, shot to death the wife’s parents,

Joe and Amanda Alvarado, in the Hill Country town of Fredericksburg.

During the previous decade, medical records showed, Mr. Panetti had been

hospitalized 14 times for schizophrenia, manic depression, hallucinations and

delusions of persecution. Claiming to have seen visions of the Devil, he nailed

shut the curtains of his house, buried his furniture and threatened to kill his

family.

One Texas jury deadlocked on his competence to stand trial, but a second jury

found him sane enough. Proclaiming himself healed by God as “a born-again April

fool,” he refused further antipsychotic medication, dismissed his lawyers and

won approval from the trial judge, Stephen B. Ables, to represent himself in

court in 1995.

He appeared with a Tom Mix cowboy hat slung over his back, wearing purple

western shirts and cowboy boots. He tried to subpoena Jesus and repeatedly

ignored Judge Ables’s orders. But it was his often brutal cross-examination of

his estranged wife, Sonja, forcing her to relive the murders in graphic detail,

that clearly terrified the jurors, who convicted him in 90 minutes and sentenced

him to death.

Afterward, Dr. F. E. Seale, a psychiatrist who treated Mr. Panetti in 1986,

voiced revulsion.

“I thought to myself, ‘My God, how in the world can our legal system allow an

insane man to defend himself?’ ” Dr. Seale said. “ ‘How can this be just?’ ”

Justices Block Execution of Delusional Killer, NYT,

29.6.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/29/washington/29execution.html?hp

Kevin Siers North

Carolina The Charlotte Observer

28.6.2007

Editorial

Three

Bad Rulings

June 26,

2007

The New York Times

The Supreme

Court hit the trifecta yesterday: Three cases involving the First Amendment.

Three dismaying decisions by Chief Justice John Roberts’s new conservative

majority.

Chief Justice Roberts and the four others in his ascendant bloc used the

next-to-last decision day of this term to reopen the political system to a new

flood of special-interest money, to weaken protection of student expression and

to make it harder for citizens to challenge government violations of the

separation of church and state. In the process, the reconfigured court extended

its noxious habit of casting aside precedents without acknowledging it —

insincere judicial modesty scored by Justice Antonin Scalia in a concurring

opinion.

First, campaign finance. Four years ago, a differently constituted court upheld

sensible provisions of the McCain-Feingold Act designed to prevent corporations

and labor unions from circumventing the ban on their spending in federal

campaigns by bankrolling phony “issue ads.” These ads purport to just educate

voters about a policy issue, but are really aimed at a particular candidate.

The 2003 ruling correctly found that the bogus issue ads were the functional

equivalent of campaign ads and upheld the Congressional restrictions on

corporate and union money. Yet the Roberts court shifted course in response to

sham issue ads run on radio and TV by a group called Wisconsin Right to Life

with major funding from corporations opposed to Senator Russell Feingold, the

Democrat who co-authored the act.

It opened a big new loophole in time to do mischief in the 2008 elections. The

exact extent of the damage is unclear. But the four dissenters were correct in

warning that the court’s hazy new standard for assessing these ads is bound to

invite evasion and fresh public cynicism about big money and politics.

The decision contained a lot of pious language about protecting free speech. But

magnifying the voice of wealthy corporations and unions over the voice of

candidates and private citizens is hardly a free speech victory. Moreover, the

professed devotion to the First Amendment did not extend to allowing taxpayers

to challenge White House aid to faith-based organizations as a violation of

church-state separation. The controlling opinion by Justice Samuel Alito offers

a cockeyed reading of precedent and flimsy distinctions between executive branch

initiatives and Congressionally authorized spending to deny private citizens

standing to sue. That permits the White House to escape accountability when it

improperly spends tax money for religious purposes.

Nor did the court’s concern for free speech extend to actually allowing free

speech in the oddball case of an Alaska student who was suspended from high

school in 2002 after he unfurled a banner reading “Bong Hits 4 Jesus” while the

Olympic torch passed. The ruling by Chief Justice Roberts said public officials

did not violate the student’s rights by punishing him for words that promote a

drug message at an off-campus event. This oblique reference to drugs hardly

justifies such mangling of sound precedent and the First Amendment.

Three Bad Rulings, NYT, 26.6.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/26/opinion/26tue1.html

Supreme

Court to Weigh Limits

on Cases Involving Medical Devices

June 26,

2007

The New York Times

By STEPHEN LABATON

WASHINGTON,

June 25 — Setting the stage for a confrontation between the states and

manufacturers, the Supreme Court said on Monday that it would hear an appeal

raising the issue of whether the makers of medical equipment approved by the

federal government may be sued under state law by patients injured by those

devices.

Although the appeal will most likely turn on the Supreme Court’s interpretation

of the 1976 medical devices amendments to the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, the

case is part of a broader debate in Washington over the extent to which the Bush

administration and Congress may preclude the states from imposing consumer

regulations that are more stringent than the federal government’s.

Federal agencies under the control of Bush administration appointees have sought

to adopt regulations covering matters as diverse as auto safety and medicine

labeling to preclude active state prosecutors and trial lawyers from bringing

lawsuits that would impose higher safety standards.

An array of agencies, including the Food and Drug Administration, the National

Highway Traffic Safety Administration and the Consumer Product Safety

Commission, have proposed or adopted rules that would make it more difficult for

consumers to bring lawsuits under state laws that are more favorable to victims

than are federal regulations.

Critics of the Bush administration say that the approach strips consumers of

valuable state protections. Supporters say the federal effort to pre-empt the

states sets uniform national standards and discourages overzealous state

prosecutors.

In the case before the Supreme Court, both the Bush administration and the

defendant company, Medtronic, had urged the justices to reject the appeal of a

patient who was injured when a balloon catheter it made ruptured during an

angioplasty in 1996.

The patient, Charles R. Riegel, and his wife, Donna, sued Medtronic for a

variety of state tort law violations, including negligent design and breach of

warranty. The company maintained that Mr. Riegel’s surgeon should not have used

the balloon catheter because of Mr. Riegel’s condition and that the surgeon used

the device in a manner inconsistent with its labeling.

Both a Federal District Court and a Federal Appeals Court in New York dismissed

most of the Riegels’ claims. Those courts concluded that because the F.D.A. had

approved the balloon catheter after a rigorous review and before it went to

market, injured patients could not file claims against Medtronic under state

law. The medical devices amendment forbids a state from adopting any requirement

“which is different from, or in addition to, any requirement” in federal law.

Federal courts around the nation have taken different views of whether that

provision bars state law damage claims against medical devices approved by the

F.D.A. The issue has so confounded the courts that three appeals courts

reviewing the same medical device made by the same company have reached two

different conclusions about whether patients could bring a lawsuit.

Lawyers involved in the Medtronic case say they expect the court to hear from

manufacturers and business groups in support of Medtronic, as well as from

states and consumer organizations on behalf of the patient who was injured. The

case, Riegel v. Medtronic, No. 06-179, is expected to be heard by the court in

the fall.

A group of similar cases involving drugs is moving through the courts.

Supreme Court to Weigh Limits on Cases Involving Medical

Devices, NYT, 26.6.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/26/business/26bizcourt.html

Student

loses ruling over "Bong Hits 4 Jesus"

Mon Jun 25,

2007

11:07AM EDT

Reuters

By James Vicini

WASHINGTON

(Reuters) - A high school student who was suspended for unfurling a banner

saying "Bong Hits 4 Jesus" did not have his rights violated, a divided U.S.

Supreme Court ruled on Monday in its first major decision on student free-speech

rights in nearly 20 years.

The high court's conservative majority ruled that a high school principal in

Juneau, Alaska, did not violate the student's constitutional free-speech rights

by confiscating the banner and then suspending him.

Student Joseph Frederick says the banner's language was meant to be nonsensical

and funny, a prank to get on television as the Winter Olympic torch relay passed

by the school in January 2002.

But school officials say the phrase "bong hits" refers to smoking marijuana.

Principal Deborah Morse suspended Frederick for 10 days because she said the

banner advocated or promoted illegal drug use in violation of school policy.

Frederick, 18, had been standing on a public sidewalk across the street from the

school when Morse grabbed his banner and crumpled it. Students had been allowed

out of class to watch the event.

The majority opinion written by Chief Justice John Roberts said the court agreed

with Morse that those who viewed the banner would interpret it as advocating or

promoting illegal drug use, in violation of school policy.

Roberts, who was appointed to the court by President George W. Bush, said a

principal may, consistent with the First Amendment, restrict student speech at a

school event when it is reasonably viewed as promoting illegal drug use.

Liberal Justices John Paul Stevens, David Souter and Ruth Bader Ginsburg

dissented on the constitutional issue. Justice Breyer said he would have decided

the case without reaching the constitutional issue by ruling the principal

cannot be held liable for damages.

Student loses ruling over "Bong Hits 4 Jesus", R,

25.6.2007,

http://www.reuters.com/article/domesticNews/idUSWBT00720120070625

Supreme

Court

Limits Students’ Speech Rights

June 25,

2007

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Filed at 10:49 a.m. ET

The New York Times

WASHINGTON

(AP) -- The Supreme Court tightened limits on student speech Monday, ruling

against a high school student and his 14-foot-long ''Bong Hits 4 Jesus'' banner.

Schools may prohibit student expression that can be interpreted as advocating

drug use, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the court in a 5-4 ruling.

Joseph Frederick unfurled his homemade sign on a winter morning in 2002, as the

Olympic torch made its way through Juneau, Alaska, en route to the Winter

Olympics in Salt Lake City.

Frederick said the banner was a nonsensical message that he first saw on a

snowboard. He intended the banner to proclaim his right to say anything at all.

His principal, Deborah Morse, said the phrase was a pro-drug message that had no

place at a school-sanctioned event. Frederick denied that he was advocating for

drug use.

''The message on Frederick's banner is cryptic,'' Roberts said. ''But Principal

Morse thought the banner would be interpreted by those viewing it as promoting

illegal drug use, and that interpretation is plainly a reasonable one.''

Morse suspended the student, prompting a federal civil rights lawsuit.

Students in public schools don't have the same rights as adults, but neither do

they leave their constitutional protections at the schoolhouse gate, as the

court said in a landmark speech-rights ruling from Vietnam era.

The court has limited what students can do in subsequent cases, saying they may

not be disruptive or lewd or interfere with a school's basic educational

mission.

This is a breaking news update. Check back soon for further information. AP's

earlier story is below.

WASHINGTON (AP) -- The Supreme Court tightened limits on student speech Monday,

ruling against a high school student and his 14-foot-long ''Bong Hits 4 Jesus''

banner.

Schools may prohibit student expression that can be interpreted as advocating

drug use, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the court.

Joseph Frederick unfurled his homemade sign on a winter morning in 2002, as the

Olympic torch made its way through Juneau, Alaska, en route to the Winter

Olympics in Salt Lake City.

Frederick said the banner was a nonsensical message that he first saw on a

snowboard. He intended the banner to proclaim his right to say anything at all.

His principal, Deborah Morse, said the phrase was a pro-drug message that had no

place at a school-sanctioned event. Frederick denied that he was advocating drug

use.

''The message on Frederick's banner is cryptic,'' Roberts said. ''But Principal

Morse thought the banner would be interpreted by those viewing it as promoting

illegal drug use, and that interpretation is plainly a reasonable one.''

Supreme Court Limits Students’ Speech Rights, NYT,

25.6.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/us/AP-Scotus-Bong-Hits.html

Supreme

Court Bars Suit on Faith Initiative

June 25,

2007

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Filed at 10:45 a.m. ET

The New York Times

WASHINGTON

(AP) -- The Supreme Court ruled Monday that ordinary taxpayers cannot challenge

a White House initiative that helps religious charities get a share of federal

money.

The 5-4 decision blocks a lawsuit by a group of atheists and agnostics against

eight Bush administration officials including the head of the White House Office

of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives.

The taxpayers' group, the Freedom From Religion Foundation Inc., objected to

government conferences in which administration officials encourage religious

charities to apply for federal grants.

Taxpayers in the case ''set out a parade of horribles that they claim could

occur'' unless the court stopped the Bush administration initiative, wrote

Justice Samuel Alito. ''Of course, none of these things has happened.''

The justices' decision revolved around a 1968 Supreme Court ruling that enabled

taxpayers to challenge government programs that promote religion.

The 1968 decision involved the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, which

financed teaching and instructional materials in religious schools in low-income

areas.

''This case falls outside'' the narrow exception allowing such cases to proceed,

Alito wrote.

In dissent, Justice David Souter said that the court should have allowed the

taxpayer challenge to proceed.

The majority ''closes the door on these taxpayers because the executive branch,

and not the legislative branch, caused their injury,'' wrote Souter. ''I see no

basis for this distinction.''

With the White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives, President

Bush says he wants to level the playing field. Religious charities and secular

charities should compete for government money on an equal footing, says the

president.

White House spokeswoman Emily Lawrimore called the ruling ''a substantial

victory for efforts by Americans to more effectively aid our neighbors in need

of help.''

She said the faith-based and community initiative can remain focused on

''strengthening America's armies of compassion.''

Supreme Court Bars Suit on Faith Initiative, NYT,

25.6.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/us/AP-Scotus-Faith-Based.html?hp

Business

Prevails in Environmental Case

June 25,

2007

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Filed at 10:32 a.m. ET

The New York Times

WASHINGTON

(AP) -- The Supreme Court sided with developers and the Bush administration

Monday in a dispute with environmentalists over protecting endangered species.

The court ruled 5-4 for home builders and the Environmental Protection Agency in

a case that involved the intersection of two environmental laws, the Clean Water

Act and the Endangered Species Act.

Justice Samuel Alito, writing for the conservative majority, said the endangered

species law takes a back seat to the clean water law when it comes to the EPA

handing authority to a state to issue water pollution permits. Developers often

need such permits before they can begin building.

A federal appeals court had said that EPA did not do enough to ensure that

endangered species would not be harmed if the state took over the permitting.

Environmental groups, backed by the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeal, said the

administration position would in essence gut a key provision of the endangered

species law. The act prohibits federal agency action that will jeopardize a

species and calls for consultation between federal agencies.

The cases are National Association of Home Builders v. Defenders of Wildlife,

06-340, EPA v. Defenders of Wildlife, 06-549.

Business Prevails in Environmental Case, NYT, 25.6.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/us/AP-Scotus-Endangered-Species.html

Justices

Loosen Restrictions on Election Ads

June 25,

2007

The New York Times

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

WASHINGTON

(AP) -- The Supreme Court loosened restrictions Monday on corporate- and

union-funded television ads that air close to elections, weakening a key

provision of a landmark campaign finance law.

The court, split 5-4, upheld an appeals court ruling that an anti-abortion group

should have been allowed to air ads during the final two months before the 2004

elections.

The case involved advertisements that Wisconsin Right to Life was prevented from

broadcasting. The ads asked voters to contact the state's two senators,

Democrats Russ Feingold and Herb Kohl, and urge them not to filibuster President

Bush's judicial nominees.

Feingold, a co-author of the campaign finance law, was up for re-election in

2004.

The provision in question was aimed at preventing the airing of issue ads that

cast candidates in positive or negative lights while stopping short of

explicitly calling for their election or defeat. Sponsors of such ads have

contended they are exempt from certain limits on contributions in federal

elections.

Chief Justice John Roberts, joined by his conservative allies, wrote a majority

opinion upholding the appeals court ruling.

The majority itself was divided in how far justices were willing to go in

allowing issue ads.

Three justices, Anthony Kennedy, Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas, would have

overruled the court's 2003 decision upholding the constitutionality of the

provision.

Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito said only that the Wisconsin group's ads are

not the equivalent of explicit campaign ads and are not covered by the court's

2003 decision.

Justices Loosen Restrictions on Election Ads, NYT,

25.6.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/us/AP-Scotus-Campaign-Finance.html?hp

8 Cases

Await Rulings by Supreme Court

June 24,

2007

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Filed at 4:52 a.m. ET

The New York Times

WASHINGTON

(AP) -- Nearly seven months have passed since the Supreme Court heard arguments

about public school integration plans. A decision, it seems, is finally at hand.

Whether school districts can use race as a factor in assigning students to

schools is the biggest unresolved issue among the eight remaining cases. But as

the court enters what is expected to be the final week of its term, several

other important topics loom. They include disputes over limits on speech,

separation of church and state and executing the mentally ill.

The court's final days are being watched perhaps even more closely than usual

this year because this is the first full term for Chief Justice John Roberts and

the current lineup of justices.