|

History > 2007 > USA > Federal Justice (IV)

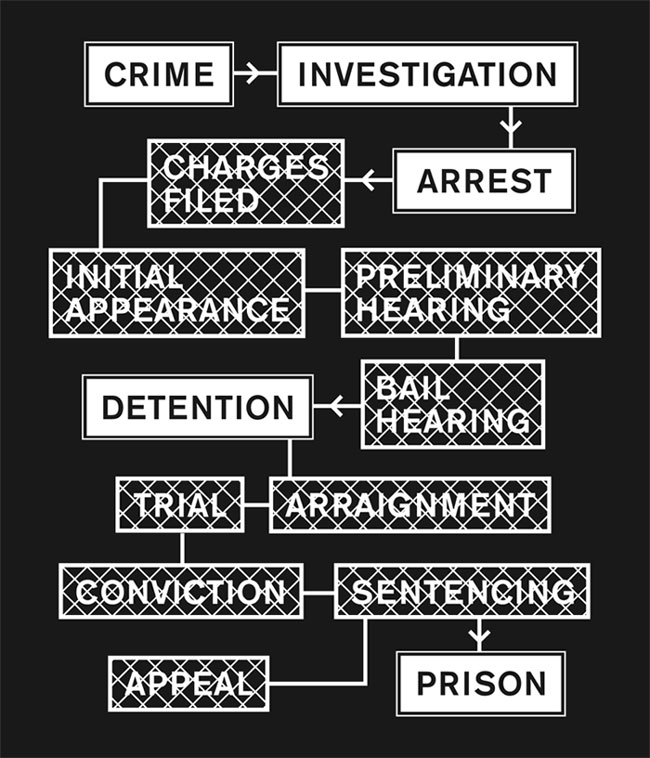

Illustration: Gary Fogelson

How to Try a Terrorist NYT

1.11.2007

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/01/opinion/01coughenour.html

Justice Dept. Seeks Delay on C.I.A. Inquiry

December 15, 2007

The New York Times

By DAVID JOHNSTON and MARK MAZZETTI

WASHINGTON — The Justice Department asked the House

Intelligence Committee on Friday to postpone its investigation into the

destruction of videotapes by the Central Intelligence Agency in 2005, saying the

Congressional inquiry presented “significant risks” to its own preliminary

investigation into the matter.

The department is taking an even harder line with other Congressional committees

looking into the matter, and is refusing to provide information about any role

it might have played in the destruction of the videotapes. The recordings

covered hundreds of hours of interrogations of two operatives of Al Qaeda.

The Justice Department and the C.I.A.’s inspector general have begun a

preliminary inquiry into the destruction of the tapes, and Attorney General

Michael B. Mukasey said the department would not comply with Congressional

requests for information now because of “our interest in avoiding any perception

that our law enforcement decisions are subject to political influence.”

Over all, the position taken by Mr. Mukasey, who took office last month,

represented what Justice Department officials described as an effort to caution

Congress against meddling in the tapes case and other politically explosive

criminal cases.

The Justice Department request was met with anger from both Republican and

Democratic members of the House Intelligence Committee, who said the department

was trying to interfere with their investigation. The committee had summoned two

C.I.A. officials to testify at a hearing next week, a session that will now

almost certainly be postponed.

The inquiry by the House committee had been shaping up as the most aggressive

investigation into the destruction of the tapes, and in a written statement on

Friday, the two senior members of the panel said they were “stunned” by the

Justice Department’s request.

The lawmakers, Representative Silvestre Reyes, Democrat of Texas, and

Representative Peter Hoekstra, Republican of Michigan, threatened to issue

subpoenas to get testimony and other information from the C.I.A. “There is no

basis upon which the attorney general can stand in the way of our work,” they

said.

The committee had demanded that the C.I.A. produce all cables, memorandums and

e-mail messages related to the videotapes, as well as the legal advice given to

agency officials before the tapes were destroyed. Friday’s deadline passed

without the arrival of any of those C.I.A. records on Capitol Hill.

The inquiries by the Justice Department and Congress began after the disclosure

last week that the C.I.A. had videotaped the 2002 interrogations of two Qaeda

operatives, Abu Zubaydah and Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri.

The tapes were destroyed in November 2005 in a decision that the current C.I.A.

director, Gen. Michael V. Hayden, who was not in charge of the agency at the

time, has said was made “in line with the law” to protect the security of C.I.A.

officers who took part in the questioning.

The preliminary joint inquiry by the Justice Department and the C.I.A. is aimed

at determining how the tapes were destroyed, who authorized their destruction,

and whether the action violated the law. The C.I.A. did not provide the tapes to

the commission that investigated the 9/11 attacks or to authorities that have

sought to prosecute terrorism suspects in the courts.

The Congressional inquiries, by the House and Senate intelligence committees and

other panels, are largely moving on a parallel track, but are also trying to

determine whether anyone in the executive branch had sought to have the tapes

destroyed to eliminate possible evidence that C.I.A. officers had used outlawed

interrogation techniques.

The Justice Department request to the House committee was made in a letter

signed by Assistant Attorney General Kenneth L. Wainstein and John L. Helgerson,

the C.I.A.’s inspector general, who are leading the preliminary criminal

investigation. “Our ability to obtain the most reliable and complete information

would likely be jeopardized if the C.I.A. undertakes the steps necessary to

respond to your requests in a comprehensive fashion at this time,” the letter

said.

Mr. Wainstein and Mr. Helgerson asked the committee’s “indulgence,” and promised

to advise the panel on when it might resume its inquiry without jeopardizing

their own investigation. But they said they could not say when the Justice

Department inquiry might be completed and asked to pursue their investigation at

the appropriate pace.

The House Intelligence Committee has been hoping to hear testimony next week

from two C.I.A. witnesses: Jose A. Rodriguez Jr., the former leader of the

agency’s clandestine branch, who is said to have ordered the destruction of the

tapes, and John A. Rizzo, the C.I.A.’s top lawyer.

Mark Mansfield, a C.I.A. spokesman, declined to comment directly on the Justice

Department’s letter. “Director Hayden has said the agency would cooperate fully

with both the preliminary inquiry conducted by D.O.J. and the C.I.A’s inspector

general and with the Congress,” he said. “That has been and certainly is the

case.”

The exchanges came as Republicans in the Senate moved on Friday to strip

language from a bill that would have prohibited the C.I.A. from using what the

White House has called “enhanced interrogation techniques,” which allow the use

of methods more aggressive than those permitted by other agencies. The House has

approved a measure containing the prohibition, but the Senate action, together

with a veto threat from President Bush, made it unlikely that it would become

law.

Mr. Mukasey was rebuffing requests from the Congressional committees that

oversee the Justice Department. The committees sent him letters this week

demanding information about the department’s role in the destruction of the

tapes and in other issues related to the possible recording of interrogations.

“At my confirmation hearing, I testified that I would act independently, resist

political pressure and ensure that politics plays no role in cases brought by

the Department of Justice,” Mr. Mukasey wrote in one letter. Accordingly, he

went on, “I will not at this time provide further information in response to

your letter.”

That letter was sent on Friday to Senators Patrick J. Leahy, Democrat of

Vermont, the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, and Arlen Specter of

Pennsylvania, the panel’s ranking Republican.

Mr. Leahy said Friday that he was disappointed that “the Department of Justice

declined to provide us, either publicly or in a classified setting, with any of

the information Senator Specter and I have requested.”

“This committee needs to fully understand whether the government used cruel

interrogation techniques and torture, contrary to our basic values,” Mr. Leahy

added.

David Johnston reported from Washington, and Mark Mazzetti from New York.

Justice Dept. Seeks

Delay on C.I.A. Inquiry, NYT, 15.12.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/15/washington/15intel.html?hp

Jury Eyeing Blackwater in Shooting of 17

November 20, 2007

Filed at 9:25 a.m. ET

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

The New York Times

WASHINGTON (AP) -- A federal grand jury is said to be

investigating the role of Blackwater Worldwide security guards in the shooting

deaths of 17 Iraqi civilians in Baghdad.

The Blackwater guards involved in the Sept. 16 shooting at Nisoor Square in west

Baghdad initially were given limited immunity from prosecution by State

Department investigators in exchange for their statements about what happened.

One senior FBI official close to the investigation told The Associated Press

last week that he was aware of evidence that could indicate 14 of the shootings

were unjustified.

Blackwater contends that its convoy was attacked before its guards opened fire,

but the Iraqi government's investigation concluded that the shootings were

unprovoked.

Dean Boyd, a Justice Department spokesman, refused to comment Tuesday on whether

a grand jury was convened, saying it's the department's long-standing policy not

to comment on grand jury matters.

ABC News reported Monday that a number of Blackwater security guards have been

subpoenaed to appear before the panel here next week.

A Blackwater spokeswoman, Anne Tyrrell, declined to comment Monday on whether

the company had received subpoenas or whether its employees had been asked to

testify.

''We have always supported stringent accountability for the industry, we still

do, and if somebody was complicit in wrongdoing we would want that person to be

held accountable,'' Tyrrell told The Washington Post. ''We will cooperate with

any inquiry or investigation and will withhold further comment until the results

are complete and made available.''

ABC said it had obtained statements given to State Department diplomatic

security agents. According to the statements, only five guards acknowledged

firing their weapons in the incident. Twelve other guards witnessed the events

but did not fire, according to the statements.

Officials cautioned that the decision to begin a grand jury inquiry did not mean

that prosecutors had decided to charge anyone with a crime in what they said was

a legally complex case, The New York Times reported. Some government lawyers

have expressed misgivings about whether a federal law exists that would apply to

the actions Blackwater employees are accused of committing, the Times reported.

Iraq, meanwhile, is demanding the right to prosecute the Blackwater bodyguards.

The Iraqi government finding that Blackwater's men were unprovoked echoed an

initial incident report by U.S. Central Command that indicated ''no enemy

activity involved'' in the incident. The U.S. Central Command oversees military

operations in Iraq.

Jury Eyeing

Blackwater in Shooting of 17, NYT, 20.11.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/us/AP-Blackwater-Probe.html

Mukasey Sworn in as Attorney General

November 14, 2007

Filed at 11:31 a.m. ET

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

The New York Times

WASHINGTON (AP) -- President Bush welcomed Michael Mukasey

back into government Wednesday and promised to help the new attorney general

rebuild the top leadership of the beleaguered Justice Department.

Speaking at Mukasey's ceremonial oath-taking, Bush said the retired federal

judge ''will bring clear purpose and resolve'' to the agency.

''As he embarks on his new responsibilities, Michael Mukasey has my complete

trust and confidence,'' Bush told a packed ceremony at the Justice Department's

Great Hall. Agency employees filled the hall and lined the balcony to watch

their new boss take the ceremonial oath from Supreme Court Chief Justice John

Roberts.

With a pointed smile at the applauding crowd, Bush added: ''And he's going to

have the trust and confidence of the men and women of the Department of

Justice.''

Bush also promised to announce on Thursday nominees to fill some of the dozen

vacant senior leadership jobs in the department, which has been in a state of

upheaval since a series of controversies -- including the dismissals of federal

prosecutors -- led to the resignation of Attorney General Alberto Gonzales.

When Bush praised Gonzales as a man of integrity and decency, Justice Department

employees responded with sustained applause. It got even louder moments later

after Mukasey took the oath, formally ending the Gonzales chapter in the

agency's history.

Mukasey, who also worked in the Justice Department early in his career as a

trial prosecutor in New York, said ''it's great to be back.''

He promised to make sure the Justice Department follows an ''unswerving

allegiance'' to the law and the Constitution.

Though he was officially sworn in last week to begin work, Mukasey said he did

not feel he had become the attorney general until taking the oath in front of

his employees.

''My job involves not only an oath, but also a pledge, which I now give you,''

Mukasey told the 110,000 Justice employees nationwide, some of whom watched on

the department's internal TV system.

''And that is to use all of the strength of mind and body that I have to help

you to continue to protect the freedom and the security of the people of this

country, and their civil rights and liberties, through the neutral and

evenhanded application of the Constitution and the laws enacted under it.''

He said he would ''ask myself in every decision I make whether it helps you to

do that, to take the counsel not only of my own insights but also of yours, and

to pray that I can help give you the leadership you deserve.''

Mukasey, 66, inherits a Justice Department struggling to restore its independent

image with more than a dozen vacant leadership jobs and little time to make many

changes before another president takes office. He now has 14 months to turn it

around after almost a year of scandal that forced Gonzales to quit and cast

doubt on the government's ability to prosecute cases fairly.

An internal Justice inquiry is investigating charges that, under Gonzales,

politics were allowed to influence decisions about prosecuting cases or hiring

career attorneys. The allegations stemmed from an ongoing congressional inquiry

of last year's firings of nine U.S. attorneys, and prompted questions about

Gonzales' honesty.

Gonzales did not attend the ceremony, which lasted only about 14 minutes and was

kicked off by a reading of the Pledge of Allegiance by Mukasey's two young

grandsons. Former attorneys general John Ashcroft and Richard Thornburgh were

among those in the crowd, which also included GOP Senate Judiciary Committee

members Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania, Lindsey Graham of South Carolina and Sam

Brownback of Kansas.

The Senate confirmed Mukasey last week by a 53-40 vote, which critics noted

marked the narrowest margin for an attorney general in 50 years. His

confirmation snagged briefly after Mukasey refused to say whether he believes an

interrogation tactic known as waterboarding is a form of torture.

Lasting only four minutes, Mukasey's comments aimed to calm the bruised

department. He allowed himself a small smile as he stood before his staff after

he was sworn in, then briskly launched into his speech.

''What each person here does, on a day to day basis, is law,'' Mukasey said.

''We don't do simply what seems fair and right according to our own tastes and

standards.''

''We do law, but the result is justice,'' he said.

Mukasey Sworn in as

Attorney General, NYT, 14.11.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/us/AP-Attorney-General.html?hp

Grand Jury Indicts Kerik on Corruption Charges

November 9, 2007

The New York Times

By WILLIAM K. RASHBAUM and MARIA NEWMAN

A federal grand jury today indicted Bernard B. Kerik, the

former New York police commissioner appointed by Rudolph W. Giuliani while he

was mayor, on charges that include tax fraud, corruption and conspiracy counts

and lying to the White House.

He turned himself in to an F.B.I. office in suburban White Plains and was to be

fingerprinted and processed, then taken by United States marshals to the Federal

Courthouse, where he is to be arraigned later on the charges that together carry

a maximum penalty of 142 years in prison and $4.7 million in fines. According to

sentencing guidelines, he will most likely face lesser charges.

The United States attorney’s office held a news conference this morning in White

Plains "to announce an indictment of a former public official," officials said.

The indictment looms over Mr. Giuliani’s campaign as he promotes himself as a

tough law-and-order candidate. As Mr. Kerik’s friend, patron and former business

partner, whose mentorship was partly responsible for Mr. Kerik’s sharp ascent

into prominence. Mr. Giuliani, who is seeking the Republican presidential

nomination, addressed the matter Thursday, when he said that he had made “a

mistake in not checking him out more carefully.”

Mr. Kerik, the indictment said, conspired with others to deprive the city and

its citizens of his honest services by accepting $255,000 in renovations to his

apartment from a company seeking to do business with the city.

The indictment also charges him with making a number of false statements to the

White House and other federal officials when he was being considered to head the

federal Department of Homeland Security, a position for which Mr. Giuliani

recommended him.

Prosecutors also charged Mr. Kerik, 52, with failing to report as income about

$255,000 in rent payments that they say was paid on his behalf to use a luxury

Upper East Side apartment from a Manhattan developer with whom he had agreed to

conduct business.

In addition, he is charged with taking steps to convince city regulators that

the contractors were free from mob ties and should be approved to do business

with the city. He took the benefits while he was city corrections commissioner

and his act of concealment occurred while he held that job and the job of police

commissioner.

When Kerik was being vetted for those posts, according to the indictment, he

failed to disclose as required and misrepresented his relationship with the

contractors who paid for the renovations or the payments themselves. He failed

to disclose submitting false financial disclosure reports and he committed a

crime by doing so and failed to disclose that he made false statements on a loan

application and committed crime in doing so. He also failed to disclose as

required a $250,000 loan that he had taken from a Brookyn business man who, in

turn, had obtained the money from an Israeli industrialist who did business with

the United States government. And he falsely stated that he had no household

employees on a regular basis and that he had not failed to withhold appropriate

taxes for any such employee.

Grand Jury Indicts

Kerik on Corruption Charges, NYT, 9.11.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/09/nyregion/09cnd-kerik.html?hp

Mukasey Wins Vote in Senate, Despite Doubts

November 9, 2007

The New York Times

By CARL HULSE

WASHINGTON, Nov. 8 — The Senate confirmed Michael B. Mukasey

as attorney general Thursday night, approving him despite Democratic criticism

that he had failed to take an unequivocal stance against the torture of

terrorism detainees.

The 53-to-40 vote made Mr. Mukasey, a former federal judge, the third person to

head the Justice Department during the tenure of President Bush, placing him in

charge of an agency that members of both parties say suffered under the

leadership of Alberto R. Gonzales.

Six Democrats joined 46 Republicans and one independent in approving the judge,

with his backers praising him as a strong choice to restore morale at the

Justice Department and independently oversee federal prosecutions in the final

months of the Bush administration.

Thirty-nine Democrats and one independent opposed him.

“The Department of Justice needs Judge Mukasey at work tomorrow morning,” said

Senator Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania, the senior Republican on the Judiciary

Committee. “The Department of Justice has been categorized as dysfunctional and

in disarray. It is in urgent need of an attorney general.”

But Democrats said Mr. Mukasey’s refusal to characterize waterboarding, an

interrogation technique that simulates drowning, as illegal torture disqualified

him from taking over as the nation’s top law enforcement official.

“I am not going to aid and abet the confirmation contortions of this

administration,” said Senator Patrick J. Leahy, Democrat of Vermont and chairman

of the Judiciary Committee. “I do not vote to allow torture.”

All five senators who are running for president -- Joseph R. Biden Jr., Hillary

Clinton, Barack Obama, Christopher J. Dodd, all Democrats, and John McCain --

did not cast votes. The four Democrats had said they would not support Mr.

Mukasey because of his equivocation during the confirmation hearings over

whether waterboarding is torture. Mr. McCain has also denounced the

interrogation method but he issued a statement last week saying he would vote to

approve the nomination.

The attorney general’s post became vacant in late August when Mr. Gonzales

stepped down. For months, he had faced severe criticism over accusations that

political calculations played a part in the department’s dismissal of some

United States attorneys last year and over his role in shaping the

administration’s policies on torture and electronic surveillance.

Mr. Mukasey was initially hailed by Democrats as a leader who would bring

welcome change to the Justice Department. His nomination had been recommended by

Senator Charles E. Schumer, Democrat of New York, a member of the party

leadership familiar with Mr. Mukasey from his service on the bench in New York.

On the first day of his confirmation hearings, Mr. Mukasey said he would resign

if directed by the White House to take any action he believed was illegal or

violated the Constitution, winning Democratic praise. On the second day of his

testimony, Mr. Mukasey sidestepped the question of whether waterboarding was

torture and also suggested that the president’s Constitutional powers could

supersede federal law in some cases.

Those responses stirred strong Democratic opposition, throwing his confirmation

into question. Trying to stem the rising opposition, Mr. Mukasey said that while

he personally found the concept of waterboarding repugnant, he could not pass

judgment on whether it was illegal because he had not been briefed on

administration interrogation techniques.

Senator Dianne Feinstein, Democrat of California, said she was confident that

Mr. Mukasey would be nonpartisan and that his refusal to make a judgment on

torture without knowing all the facts of interrogation policy should not keep

him from the post.

“This man has been a judge for 18 years,” said Ms. Feinstein, who along with Mr.

Schumer provided the key supporting votes to push Mr. Mukasey through the

Judiciary Committee. “Maybe he likes to consider the facts before he makes a

decision.”

But she was in conflict with most of her Democratic colleagues. Senator Harry

Reid of Nevada, the Democratic leader, opposed the choice even though he said he

was predisposed to back Mr. Mukasey.

“During his confirmation hearings, Judge Mukasey expressed views about executive

power that I and many other senators found deeply disturbing,” Mr. Reid said.

“And I was outraged by his evasive, hair-splitting approach to questions about

the legality of waterboarding.”

Republicans hailed Mr. Mukasey and accused Democrats of stalling the nomination

and focusing on the torture issue to score political points. “The Department of

Justice has a vital role to play in the war against Islamic terrorists, and it

is critically important that it have a leader who can ensure that it fulfills

its mission,” said Senator Jon Kyl, Republican of Arizona. “Judge Mukasey is

this kind of leader.”

Mukasey Wins Vote

in Senate, Despite Doubts, NYT, 9.11.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/09/washington/09mukasey.html?hp

Op-Ed Contributor

A Vote for Justice

November 6, 2007

The New York Times

By CHARLES SCHUMER

Washington

I AM voting today to support Michael B. Mukasey for attorney general for one

critical reason: the Department of Justice — once the crown jewel among our

government institutions — is a shambles and is in desperate need of a strong

leader, committed to depoliticizing the agency’s operations.

The department has been devastated under the Bush administration. Outstanding

United States attorneys have been dismissed without cause; career civil-rights

lawyers have been driven out in droves; people appear to have been prosecuted

for political reasons; young lawyers have been rejected because they were not

conservative ideologues; and politics has been allowed to infect

decision-making.

We are now on the brink of a reversal. There is virtually universal agreement,

even from those who oppose Judge Mukasey, that he would do a good job in turning

the department around. My colleagues who oppose his confirmation have gone out

of their way to praise his character and qualifications. Senator Sheldon

Whitehouse, Democrat of Rhode Island, for one, commended Judge Mukasey as “a

brilliant lawyer, a distinguished jurist and by all accounts a good man.”

Most important, Judge Mukasey has demonstrated his fidelity to the rule of law,

saying that if he believed the president were violating the law he would resign.

Should we reject Judge Mukasey, President Bush has said he would install an

acting, caretaker attorney general who could serve for the rest of his term

without the advice and consent of the Senate. To accept such an unaccountable

attorney general, I believe, would be to surrender the department to the extreme

ideology of Vice President Dick Cheney and his chief of staff, David Addington.

All the work we did to pressure Attorney General Alberto Gonzales to resign

would be undone in a moment.

I deeply oppose this administration’s opaque policy on the use of torture — its

refusal to reveal what forms of interrogation it considers acceptable. In

particular, I believe that the cruel and inhumane technique of waterboarding is

not only repugnant but also illegal under current laws and conventions. I also

support Congress’s efforts to pass additional measures that would explicitly ban

this and other forms of torture. I voted for Senator Ted Kennedy’s anti-torture

amendment in 2006 and am a co-sponsor of his similar bill in this Congress.

Judge Mukasey’s refusal to state that waterboarding is illegal was

unsatisfactory to me and many other members of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

But Congress is now considering — and I hope we will soon pass — a law that

would explicitly ban the use of waterboarding and other abusive interrogation

techniques. And I am confident that Judge Mukasey would enforce that law.

On Friday, he personally made clear to me that if the law were in place, the

president would have no legal authority to ignore it — not even under some

theory of inherent authority granted by Article II of the Constitution, as Vice

President Cheney might argue. Nor would the president be able to evade a clear

pronouncement on the subject from the courts. Judge Mukasey also pledged to

enforce such a law.

From a Bush nominee, this is no small commitment. In many aspects, Judge Mukasey

reminds me of Jim Comey, a former deputy attorney general in the Bush

administration who has been widely praised for his independence; he did not

always agree with us on the issues, but was willing to fight administration

officials when he thought they were wrong.

Even without the proposed law in place, Judge Mukasey would be more likely than

a caretaker attorney general to find on his own that waterboarding and other

techniques are illegal. Indeed, his written answers to our questions have

demonstrated more openness to ending the practices we abhor than either of this

president’s previous attorney general nominees have had.

I understand and respect my colleagues who believe that Judge Mukasey’s view on

torture should trump all other considerations. For the Senate to make a bold

declaration about torture and waterboarding by rejecting him is appealing. But

if we block Judge Mukasey’s nomination and then learn in six months that

waterboarding has continued unabated, that victory will seem much less valuable.

To defeat him would be to abandon the hope of instituting the many reforms

called for by our investigation. No one questions that Judge Mukasey would do

much to remove the stench of politics from the Justice Department. I believe we

should give him that chance.

Charles Schumer, a Democrat, is a senator from New York.

A Vote for Justice,

NYT, 6.11.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/06/opinion/06schumer.html

Rules Lower Prison Terms in Sentences for Crack

November 2, 2007

The New York Times

By SOLOMON MOORE

Crack cocaine offenders will receive shorter prison sentences

under more lenient federal sentencing guidelines that went into effect

yesterday.

The United States Sentencing Commission, a government panel that recommends

appropriate federal prison terms, estimated that the new guidelines would reduce

the federal prison population by 3,800 in 15 years.

The new guidelines will reduce the average sentence for crack cocaine possession

to 8 years 10 months from 10 years 1 month. At a sentencing commission hearing

in Washington on Nov. 13, members will consider whether to apply the guidelines

retroactively to an estimated 19,500 crack cocaine offenders who were sentenced

under the earlier, stricter guidelines.

The changes to the original 1987 guidelines could also add impetus to three

bills in the Senate, one sponsored by a Democrat and two by Republicans, that

would reduce or eliminate mandatory minimums for simple drug possession.

Department of Justice officials said yesterday that applying the new guidelines

retroactively would erode federal drug enforcement efforts and undermine

Congress’s role in creating sentencing policy.

“The commission is now considering applying the changes retroactively, something

that Congress has not suggested in any of the pending bills,” wrote a department

spokesman, Peter Carr. “As we state in a letter filed with the commission today,

we believe this would be a mistake, having a serious impact on the safety of our

communities and impose an unreasonable burden upon our judicial system.”

If the guidelines are retroactive, crack cocaine offenders would be eligible to

apply to the judge or court that sentenced them for reduced prison terms.

In a letter to the commission in support of retroactivity, the American Bar

Association acknowledged the possibility that “courts will likely be inundated”

by crack cocaine offenders trying to appeal their cases under the new guidelines

regardless of the commission’s decision. But the association said that applying

the new rules to current prisoners would result in “cleaner and more uniform

decisions.”

Although Congress sets federal criminal statutes and could have rejected the

sentencing guidelines within the 180-day period that ended yesterday, once the

new guidelines were adopted it became the commission’s sole decision to apply

the new rules retroactively or not.

Some legal observers said the guideline changes were a way of shoring up the

commission’s credibility in the wake of a 2005 Supreme Court case that allowed

federal judges, many of whom thought the guidelines were too harsh, to apply

lower sentences in some crack cocaine sentences.

“That created a kind of instability in the overall sentencing guidelines,” said

Douglas A. Berman, an Ohio State University law professor. “I think the

commission recognized that the long-term health of all of its guidelines depends

on its ability to get judicial adherence to their guidelines.”

Federal penalties for crack cocaine were also widely criticized by civil rights

activists, politicians and the Sentencing Commission itself for increasing

racial disparities in the federal prison population. Blacks make up more than 80

percent of federal crack convictions, according to the commission.

Critics said it was unfair to apply longer sentences for crack cocaine than for

similar substances, including powder cocaine. Under the current federal law, for

example, the minimum sentence for possession of 5,000 grams of powder cocaine is

10 years, the same as the minimum sentence for 50 grams of crack cocaine.

The commission has also argued that the old sentencing rules diverted resources

away from major drug cases to low-level street dealers.

The commission proposed changes to its guidelines on crack cocaine offenses in

1995 and was rejected by Congress, sparking riots in the federal prison system.

Rules Lower Prison

Terms in Sentences for Crack, NYT, 2.11.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/02/us/02crack.html

Illustration: Igor Kopelnitsky

The Issue Is Torture: Voices of Outrage

NYT 2.11.2007

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/02/opinion/l02torture.html

Letters

The Issue Is Torture: Voices of Outrage

November 2, 2007

The New York Times

To the Editor:

Re “Nominee’s Stand May Avoid Tangle of Torture Cases” (front page, Nov. 1):

What are we coming to when Judge Michael B. Mukasey, a thoroughly decent man

whom I have known and admired for more than 30 years, is forced essentially to

plead the Fifth Amendment as to whether the department he has been asked to lead

authorizes illegal torture?

We are fast becoming an embarrassment in the world court of public opinion.

Frederick T. Davis

Paris, Nov. 1, 2007

The writer is a lawyer.

•

To the Editor:

Michael B. Mukasey, the nominee for attorney general, is doing an elaborate tap

dance around the issue of waterboarding and torture to steer clear of potential

legal problems for the C.I.A. and members of the Bush administration.

With this much choreography, there is one obvious conclusion: contrary to

statements by President Bush, we do torture. Sam Duncan

Wayne, Pa., Nov. 1, 2007

To the Editor:

So our nominee for attorney general refuses to declare waterboarding illegal —

after being educated by a member of Congress on what it actually is. That

explanation destroyed Judge Michael B. Mukasey’s ability to deny knowledge of

the practice; one is reminded of the obfuscation of Alberto R. Gonzales, the

former attorney general, in his bobbing and weaving before Congress’s questions.

Clearly, if confirmed, Judge Mukasey would act as a “team player” of the Bush

administration, helping to cover up issues of torture, rather than as an

independent enforcer of the nation’s laws.

Part of the legacy of such a confirmation would be, inevitably, condoning

waterboarding and other methods of torture in the future — with continuing

damage to our values, our international relations and the safety of our own

soldiers if captured.

Can such a man ever be expected to rule fairly on issues involving torture?

Kathryn W. Kelber

Houston, Nov. 1, 2007

The writer is a lawyer.

•

To the Editor:

So, Judge Michael B. Mukasey has refused so far to acknowledge that

waterboarding is torture because of his concern that such a statement by him

might put the C.I.A. and other American interrogators in legal jeopardy. But

doesn’t a former federal judge know that there is a remedy for such situations?

It’s called the judicial system.

Someone accused of breaking the law is investigated, perhaps charged, arrested,

arraigned, witnesses are called and so on — in short, a trial. The attorney

general is not charged with protecting possible violators of the law but of

prosecuting them. This is a nation of laws, not men. Walter Friedenberg

Denver, Nov. 1, 2007

•

To the Editor:

I had the misfortune to come very close to drowning. I panicked while swimming

in a river in England, and was pulled out of the water unconscious by a young

woman, who saved my life.

Recalling that experience, which must have lasted a couple of minutes at the

most, is still enough to make me tremble; it happened 30 years ago.

It turns my stomach to think that those who act on behalf of this civilized

country may be using simulated drowning to question potentially innocent people.

Is there no decency left in this ugly so-called war? Peter Cleary

San Francisco, Nov. 1, 2007

•

To the Editor:

Re “Torture and the Attorneys General” (editorial, Nov. 1):

Torture is indubitably illegal under customary international law and the laws

and treaties of the United States.

It is also inherently unreliable as a method of extracting information, because

there’s always the risk that the one being tortured will say or do anything to

stop the pain.

Furthermore, broadcasting to the world that the United States engages in torture

when expedient inevitably undermines our reputation as an exemplar of democracy

and human rights. Why, then, does Judge Michael B. Mukasey, the man who might

become the nation’s top law enforcement official, seem to waffle when it comes

to this seemingly straightforward issue?

What part of illegal does he not understand? James P. Rudolph

Washington, Nov. 1, 2007

The writer is a lawyer.

•

To the Editor:

“Bearing Witness to Torture,” by Clyde Haberman (NYC column, Oct. 30), suggests

there may be a connection between the upsurge in torture victims seeking help at

the N.Y.U. Program for Survivors of Torture and the United States’ current

policies on torture.

When the leaders of the United States government shirk their obligation under

international law to prohibit torture against suspected terrorists held in

American prisons, when presidential candidates make statements implying a

defense of torture and when the president’s nominee for attorney general, Judge

Michael B. Mukasey, refuses to say whether he believes that waterboarding is

torture, we shouldn’t be surprised if governments around the world step up

torture against their citizens.

As director of the N.Y.U. Center, Dr. Allen S. Keller deals with the awful

consequences of torture and says N.Y.U. has been “swamped” by a record 581

patients from October 2006 to September 2007.

His experiences as director tell him correctly that waterboarding is torture.

From his wise perspective, as he says, it may be a more brutal form of water

torture. Larry Cox

Executive Director

Amnesty International USA

New York, Oct. 30, 2007

The Issue Is Torture:

Voices of Outrage, NYT, 2.11.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/02/opinion/l02torture.html

Op-Ed Contributor

How to

Try a Terrorist

November 1,

2007

The New York Times

By JOHN C. COUGHENOUR

Seattle

MICHAEL B. MUKASEY, President Bush’s nominee to be attorney general, is coming

under increasing fire for his views on what constitutes illegal torture. But the

aspect of his philosophy that worries me more is his view of the judiciary’s

role in prosecuting the war on terror.

Judge Mukasey expressed his own views on the subject in August in an op-ed

article in The Wall Street Journal in which he argued that our legal system is

“strained and mismatched,” and implored Congress to consider “several proposals

for a new adjudicatory framework.” Judge Mukasey suggested we strike a different

balance between civil liberties and national security in terrorism cases.

His views are undoubtedly informed by the time he spent on the federal bench,

where he presided over the trial of Omar Abdel Rahman and others involved in the

1993 World Trade Center bombing. By most accounts, Judge Mukasey did an

exemplary job of protecting national security while ensuring that defendant’s

right to a fair trial. The conclusion he draws, however, is by no means

compelled by a vantage point from the bench.

In 2001, I presided over the trial of Ahmed Ressam, the confessed Algerian

terrorist, for his role in a plot to bomb Los Angeles International Airport.

That experience only strengthened my conviction that American courts, guided by

the principles of our Constitution, are fully capable of trying suspected

terrorists.

As evidence of “the inadequacy of the current approach to terrorism

prosecutions,” Judge Mukasey noted that there have been only about three dozen

convictions in spite of Al Qaeda’s growing threat. Open prosecutions, he argued,

potentially disclose to our enemies methods and sources of

intelligence-gathering. Our Constitution does not adequately protect society

from “people who have cosmic goals that they are intent on achieving by

cataclysmic means,” he wrote.

It is regrettable that so often when our courts are evaluated for their ability

to handle terrorism cases, the Constitution is conceived as mere solicitude for

criminals. Implicit in this misguided notion is that society’s somehow

charitable view toward “ordinary” crimes of murder or rape ought not to extend

to terrorists. In fact, the criminal procedure required under our Constitution

reflects the reality that law enforcement is not perfect, and that questions of

guilt necessarily precede questions of mercy.

Consider the fact that of the 598 people initially detained at Guantánamo Bay in

2002, 267 have been released. It is likely that for a number of the former

detainees, there was simply no basis for detention. The American ideal of a just

legal system is inconsistent with holding “suspects” for years without trial.

Judge Mukasey raises a legitimate concern about whether open judicial

proceedings may compromise intelligence gathering. But courts are equipped to

meet this challenge. The Classified Information Procedures Act provides a set of

rules for criminal cases. They include the appointment of a court security

officer to oversee protocol for classified information. The law also states that

only people with security clearance may have access to classified information,

and only as needed for their jobs.

Certainly this system cannot entirely prevent any misuse of information; the

mere fact of an arrest may tell a story we’d rather our enemies not hear. But

our system provides a sensible way to protect national security while

maintaining some degree of transparency.

The case against Mr. Ressam demonstrates that our courts can protect Americans

from terrorism. Through the commendable efforts of law enforcement authorities

in 1999, Mr. Ressam was captured before he was able to carry out his plan to

bomb the airport. For two years after his conviction, thanks in part to the

fairness he was shown by the court, Mr. Ressam provided intelligence useful to

terrorism investigations around the world, as German, Italian, French and

British authorities were willing to attest.

After a fair and open trial in which Mr. Ressam was convicted by a jury of his

peers, I stated at sentencing that “we have the resolve in this country to deal

with the subject of terrorism, and people who engage in it should be prepared to

sacrifice a major portion of their life in confinement.” Mr. Ressam now sits in

a federal prison, and his punishment has the imprimatur of our time-honored

constitutional values.

If confirmed, Judge Mukasey will join Michael Chertoff as another esteemed

former jurist in the executive branch facing the formidable task of keeping our

nation safe from terrorism. The distinction between the roles of judge and law

enforcement officer should not be lost in the transition. Our courts ensure an

independent process; they do not enforce the prerogatives of law enforcement.

Any proposal that would blur this distinction would compromise a bedrock

principle of government that has defined this country from its inception. This

is a price too high to pay.

John C. Coughenour is a federal district judge.

How to Try a Terrorist, NYT, 1.11.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/01/opinion/01coughenour.html

Editorial

Torture

and the Attorneys General

November 1,

2007

The New York Times

Consider

how President Bush has degraded the office of attorney general.

His first choice, John Ashcroft, helped railroad undue restrictions of civil

liberties through Congress after the 9/11 attacks. Mr. Ashcroft apparently had

some red lines and later rebuffed the White House when it pushed him to endorse

illegal wiretapping. Then came Alberto Gonzales who, while he was White House

counsel, helped to redefine torture, repudiate the Geneva Conventions and create

illegal detention camps. As attorney general, Mr. Gonzales helped cover up the

administration’s lawless behavior in anti-terrorist operations, helped revoke

fundamental human rights for foreigners and turned the Justice Department into a

branch of the Republican National Committee.

Mr. Gonzales resigned after his extraordinary incompetence became too much for

even loyal Republicans. Now Mr. Bush wants the Senate to confirm Michael

Mukasey, a well-respected trial judge in New York who has stunned us during the

confirmation process by saying he believes the president has the power to negate

laws and by not committing himself to enforcing Congressional subpoenas. He also

has suggested that he will not uphold standards of decency during wartime

recognized by the civilized world for generations.

After a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing in which Mr. Mukasey refused to

detail his views on torture, he submitted written answers to senators’ questions

that were worse than his testimony. They suggest that he, like Mr. Gonzales,

would enable Mr. Bush’s lawless behavior and his imperial attitude toward

Congress and the courts.

In a letter to the 10 Democrats on the committee, Mr. Mukasey refused to say

whether he considered waterboarding (a method of extracting information by

making a prisoner believe he is about to be drowned) to be torture. He said he

found it “repugnant,” but could not say whether it is illegal until he has been

briefed on the interrogation programs that Mr. Bush authorized at Central

Intelligence Agency prisons.

This is a crass dodge. Waterboarding is torture and was prosecuted as such as

far back as 1902 by the United States military when used in a slightly different

form on insurgents in the Philippines. It meets the definition of torture that

existed in American law and international treaties until Mr. Bush changed those

rules. Even the awful laws on the treatment of detainees that were passed in

2006 prohibited the use of waterboarding by the American military.

And yet the nominee for attorney general has no view on whether it would be

legal for an employee of the United States government to subject a prisoner to

that treatment? The only information Mr. Mukasey can possibly be lacking is

whether Mr. Bush broke the law by authorizing the C.I.A. to use waterboarding —

a judgment that the White House clearly does not want him to render in public

because it could expose a host of officials to criminal accountability.

Mr. Mukasey’s letter to the Senate committee accepts the administration’s use of

the so-called shocks-the-conscience test to determine the legality of

interrogation methods, rather than the clear and specific prohibitions against

torture, humiliation and cruel treatment embedded in American and international

law. The administration’s standard is dangerously vague, invites abuse and

amounts to a unilateral reinterpretation of the Geneva Conventions. Would Mr.

Mukasey approve of a foreign jailer using waterboarding on an American soldier?

Mr. Bush’s policies increase the danger of that happening.

There seems to be little chance that Mr. Bush will appoint the sort of attorney

general that the nation needs, a job that includes enforcing voting rights laws

and civil rights laws and ensuring that criminal prosecutions are done fairly.

Still, senators with a conscience that can be shocked should insist that Mr.

Bush meet a higher standard than this nomination.

Torture and the Attorneys General, NYT, 1.11.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/01/opinion/01thu1.html

Nominee’s Stand Avoiding Tangle of Torture Cases

November 1,

2007

The New York Times

By SCOTT SHANE

WASHINGTON,

Oct. 31 — In adamantly refusing to declare waterboarding illegal, Michael B.

Mukasey, the nominee for attorney general, is steering clear of a potential

legal quagmire for the Bush administration: criminal prosecution or lawsuits

against Central Intelligence Agency officers who used the harsh interrogation

practice and those who authorized it, legal experts said Wednesday.

On Wednesday, Senator Patrick J. Leahy, Democrat of Vermont, the chairman of the

Senate Judiciary Committee, scheduled a confirmation vote for Tuesday amid deep

uncertainty about the outcome at the committee level. If Mr. Mukasey’s

nomination reaches the Senate floor, moderate Democrats appear likely to join

Republicans to produce a majority for confirmation. But a party-line vote in the

Judiciary Committee, which seemed a possibility, could block the nomination from

reaching the floor.

The biggest problem for Mr. Mukasey remains his refusal to take a clear legal

position on the interrogation technique. Fear of opening the door to criminal or

civil liability for torture or abuse, whether in an American court or in courts

overseas, appeared to loom large in Mr. Mukasey’s calculations as he parried

questions from the committee this week. Some legal experts suggested that

liability could go all the way to President Bush if he explicitly authorized

waterboarding.

Waterboarding is a centuries-old interrogation method in which a prisoner’s face

is covered with cloth and then doused with water to create a feeling of

suffocation. It was used in 2002 and 2003 by C.I.A. officers questioning at

least three high-level terrorism suspects, government officials say.

Senator Arlen Specter of Penn-sylvania, the committee’s top Republican, said at

a hearing Wednesday that any statement by Mr. Mukasey that waterboarding is

torture could fuel criminal charges or lawsuits against those responsible for

waterboarding.

“The facts are that an expression of an opinion by Judge Mukasey prior to

becoming attorney general would put a lot of people at risk for what has

happened,” Mr. Specter said.

Mr. Specter, who said he was briefed on the interrogation issue this week by the

C.I.A. director, Gen. Michael V. Hayden, noted that human rights groups had

filed a criminal complaint on torture against Donald H. Rumsfeld, the former

defense secretary, while he was visiting France this month. Such cases, based on

the legal concept of “universal jurisdiction” for torture and certain other

crimes, have proliferated in recent years, though they have often posed more of

an aggravation than a serious threat.

Jack L. Goldsmith, who served in the Justice Department in 2003 and 2004, wrote

in his recent memoir, “The Terror Presidency,” that the possibility of future

prosecution for aggressive actions against terrorism was a constant worry inside

the Bush administration.

“I witnessed top officials and bureaucrats in the White House and throughout the

administration openly worrying that investigators, acting with the benefit of

hindsight in a different political environment, would impose criminal penalties

on heat-of-battle judgment calls,” Mr. Goldsmith wrote.

Scott L. Silliman, an expert on national security law at Duke University School

of Law, said any statement by Mr. Mukasey that waterboarding was illegal torture

“would open up Pandora’s box,” even in the United States. Such a statement from

an attorney general would override existing Justice Department legal opinions

and create intense pressure from human rights groups to open a criminal

investigation of interrogation practices, Mr. Silliman said.

“You would ask not just who carried it out, but who specifically approved it,”

said Mr. Silliman, director of the Center on Law, Ethics and National Security

at Duke. “Theoretically, it could go all the way up to the president of the

United States; that’s why he’ll never say it’s torture,” Mr. Silliman said of

Mr. Mukasey.

Robert M. Chesney, of Wake Forest University School of Law, said Mr. Mukasey’s

statements could influence the climate in which prosecution decisions are made.

“There is a culture of concern about where Monday-morning quarterbacking could

lead to,” Mr. Chesney said. If Mr. Mukasey declared waterboarding illegal, “it

would make it politically more possible to go after interrogators in the

future,” he said. “Whether it would change the legal equities is far less

clear.”

Mr. Chesney and other specialists emphasized that prosecution in the United

States, even under a future administration, would face huge hurdles because

Congress since 2005 has adopted laws offering legal protections to interrogators

for actions taken with government authorization. Justice Department legal

opinions are believed to have approved waterboarding, among other harsh methods.

Jennifer Daskal, senior counterterrorism counsel at Human Rights Watch, said Mr.

Mukasey “is hedging in the interest of protecting current and former

administration officials from possible prosecution,” either in other countries

or by a future American administration. “What he should be doing is providing a

straightforward interpretation of the law,” she said.

Mr. Mukasey, 66, a retired federal judge from New York, referred to the criminal

liability issue several times in nearly 180 pages of written answers delivered

to the Senate on Tuesday. He said that while he personally found waterboarding

and similar interrogation methods “repugnant,” he could not call them illegal.

One reason, he said, was to avoid any implication that intelligence officers and

their bosses had broken the law.

“I would not want any uninformed statement of mine made during a confirmation

process to present our own professional interrogators in the field, who must

perform their duty under the most stressful conditions, or those charged with

reviewing their conduct,” Mr. Mukasey wrote, “with a perceived threat that any

conduct of theirs, past or present, that was based on authorizations supported

by the Department of Justice could place them in personal legal jeopardy.”

If the judiciary committee were to split along party lines, the deciding vote

could go to Senator Charles E. Schumer, Democrat of New York, who first

suggested Mr. Mukasey to succeed Alberto R. Gonzales.

That would leave Mr. Schumer, ordinarily an enthusiastic partisan combatant,

with a difficult decision: whether to break with his fellow Democrats and save

Mr. Mukasey’s nomination or to vote to kill the nomination of a man he has

highly praised.

On Wednesday, Mr. Schumer was uncharacteristically reluctant to discuss his

views. He avoided television crews waiting outside an unrelated press conference

and refused to answer questions about the judge’s letter on waterboarding.

“I’m not going to comment on Judge Mukasey here,” he said. “I’m reading the

letter, I’m going over it.”

Dana M. Perino, the White House press secretary, said Democrats were “playing

politics” with the waterboarding issue, noting that Mr. Mukasey had not been

briefed on classified interrogation methods. “I can’t imagine the Democrats

would want to hold back his nomination just because he is a thoughtful, careful

thinker who looks at all the facts before he makes a judgment,” Ms. Perino said.

Senator Orrin G. Hatch, Republican of Utah, offered a fierce defense of Mr.

Mukasey, who he said had spent “40 days in the partisan wilderness,” on the

Senate floor. “What kind of crazy, topsy-turvy confirmation process is this?”

Mr. Hatch asked.

But Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, Democrat of Rhode Island, declared on the floor

that he would vote against confirming Mr. Mukasey, whom he called a good man and

a brilliant lawyer, because of the torture question. “I don’t think anyone

intended this nomination to turn on this issue,” Mr. Whitehouse said.

Three Republicans who have denounced waterboarding wrote to Mr. Mukasey on

Wednesday, suggesting that they would support him but urging him to declare

waterboarding illegal after he is confirmed.

The senators, John McCain of Arizona, John W. Warner of Virginia and Lindsey

Graham of South Carolina, said anyone who engaged in waterboarding “puts himself

at risk of prosecution, including under the War Crimes Act, and opens himself to

civil liability as well.”

Carl Hulse and Steven Lee Myers contributed reporting.

Nominee’s Stand Avoiding Tangle of Torture Cases, NYT,

1.11.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/01/washington/01mukasey.html?hp

|