|

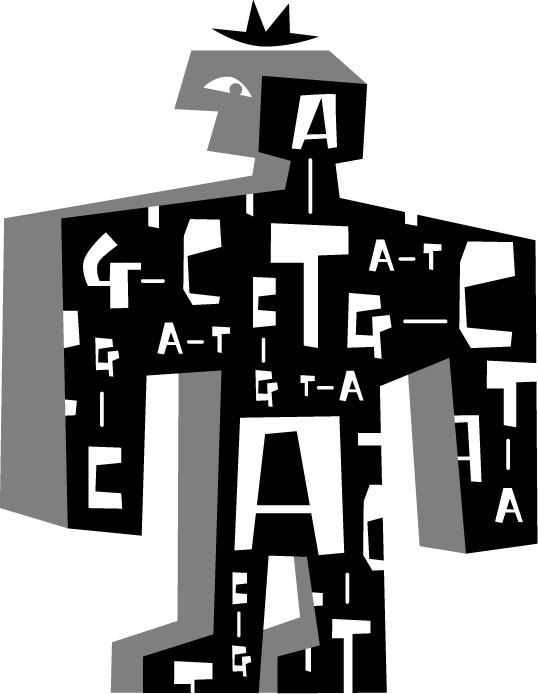

History > 2007 > USA > Health (V)

Illustration: Michael Bartalos

Getting to Know Your DNA

NYT

23 November 2007

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/23/opinion/l23dna.html

Six Killers: Lung Disease

From Smoking Boom,

a Major Killer of Women

November 29, 2007

The New York Times

By DENISE GRADY

For Jean Rommes, the crisis came five years ago, on a Monday

morning when she had planned to go to work but wound up in the hospital, barely

able to breathe. She was 59, the president of a small company in Iowa. Although

she had quit smoking a decade earlier, 30 years of cigarettes had taken their

toll.

After several days in the hospital, she was sent home tethered to an oxygen

tank, with a raft of medicines and a warning: “If I didn’t do something, life

was going to continue to be a pretty scary experience.”

Ms. Rommes has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or C.O.P.D., a progressive

illness that permanently damages the lungs and is usually caused by smoking.

Once thought of as an old man’s disease, this disorder has become a major killer

in women as well, the consequence of a smoking boom in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s.

The death rate in women nearly tripled from 1980 to 2000, and since 2000, more

women than men have died or been hospitalized every year because of the disease.

“Women started smoking in what I call the Virginia Slims era, when they started

sponsoring sporting events,” said Dr. Barry J. Make, a lung specialist at

National Jewish Medical and Research Center in Denver. “It’s now just catching

up to them.”

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease actually comprises two illnesses: one,

emphysema, destroys air sacs deep in the lungs; the other, chronic bronchitis,

causes inflammation, congestion and scarring in the airways. The disease kills

120,000 Americans a year, is the fourth leading cause of death and is expected

to be third by 2020. About 12 million Americans are known to have it, including

many who have long since quit smoking, and studies suggest that 12 million more

cases have not been diagnosed. Half the patients are under 65. The disease has

left some 900,000 working-age people too sick to work and costs $42 billion a

year in medical bills and lost productivity.

“It’s the largest uncontrolled epidemic of disease in the United States today,”

said Dr. James Crapo, a professor at the National Jewish Medical and Research

Center.

Experts consider the statistics a national disgrace. They say chronic lung

disease is misdiagnosed, neglected, improperly treated and stigmatized as

self-induced, with patients made to feel they barely deserve help, because they

smoked. The disease is mired in a bog of misconception and prejudice, doctors

say. It is commonly mistaken for asthma, especially in women, and treated with

the wrong drugs.

Although incurable, it is treatable, but many patients, and some doctors,

mistakenly think little can be done for it. As a result, patients miss out on

therapies that could help them feel better and possibly live longer. The

therapies vary, but may include drugs, exercise programs, oxygen and lung

surgery.

Incorrectly treated, many fall needlessly into a cycle of worsening illness and

disability, and wind up in the emergency room over and over again with pneumonia

and other exacerbations — breathing crises like the one that put Ms. Rommes in

the hospital — that might have been averted.

“Patients often come to me with years of being under treated,” said Dr. Byron

Thomashow, the director of the Center for Chest Disease at

NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia hospital.

Still others are overtreated for years with steroids like prednisone, which is

meant for short-term use and if used too much can thin the bones, weaken muscles

and raise the risk of cataracts.

Adequate treatment means drugs, usually inhaled, that open the airways and quell

inflammation — preventive medicines that must be used daily, not just in

emergencies. It is essential to quit smoking.

Patients also need antibiotics to fight lung infections, vaccines to prevent flu

and pneumonia and lessons on special breathing techniques that can help them

make the most of their diminished lungs. Some need oxygen, which can help them

be more active and prolong life in severe cases. Many need dietary advice:

obesity can worsen symptoms, but some with advanced disease lose so much weight

that their muscles begin to waste. Some people with emphysema benefit from

surgery to remove diseased parts of their lungs.

Above all, patients need exercise, because shortness of breath drives many to

become inactive, and they become increasingly weak, homebound, disabled and

depressed. Many could benefit from therapy programs called pulmonary

rehabilitation, which combine exercise with education about the disease, drugs

and nutrition, but the programs are not available in all parts of the country,

and insurance coverage for them varies.

“I have a complicated, severe group of patients, but I will swear to you that

very few wind up in hospitals,” Dr. Thomashow said. “I treat aggressively. I use

the medicines, I exercise all of them. You can make a difference here. This is

an example of how we’re undertreating this entire disease.”

Little-Known Epidemic

Researchers say there is so little public awareness of how common and serious

C.O.P.D. is that the O might as well stand for “obscure” or “overlooked.”

The disease may not be well known, but people who have it are a familiar sight.

They are the ones who cannot climb half a flight of stairs without getting

winded, who have a perpetual smoker’s cough or wheeze, who need oxygen to walk

down the block or push a cart through the supermarket. Some grow too weak and

short of breath to leave the house. The flu or even a cold can put them in the

hospital. In advanced stages, the lung disease can lead to heart failure.

“This is a disease where people eventually fade away because they can no longer

cope with life,” said Grace Anne Dorney Koppel, who has chronic lung disease.

(Ms. Dorney Koppel, a lawyer, is married to Ted Koppel.) “My God, if you don’t

have breath, you don’t have anything.”

Most cases, about 85 percent, are caused by smoking, and symptoms usually start

after age 40, in people who have smoked a pack a day for 10 years or more. In

the United States, 45 million people smoke, 21 percent of adults. Only about 20

percent of smokers develop chronic lung disease.

The illness is not the same as asthma, but some patients have asthma along with

their other lung problems. Most have a combination of emphysema and chronic

bronchitis. In about one-sixth of cases, emphysema is the main problem. Women

are far more likely than men to develop chronic bronchitis, and are less prone

to emphysema. Some studies have suggested that women’s lungs are more sensitive

than men’s to the toxins in smoke.

Worldwide, these lung diseases kill 2.5 million people a year. An article in

September in The Lancet, a medical journal, said that “if every smoker in the

world were to stop smoking today, the rates of C.O.P.D. would probably continue

to increase for the next 20 years.” The reason is that although quitting slows

the disease, it can develop later.

Cigarettes are the major cause worldwide, but other sources are important in

developing countries, especially smoke from indoor fires that burn wood, coal,

straw or dung for heating and cooking. Women and children are most likely to be

exposed. Outdoor air pollution plays less of a part: it can aggravate existing

disease, but is believed to cause only 1 percent of cases in rich countries and

2 percent in poorer ones. Occupational exposures in cotton mills and mines may

contribute.

Researchers have differed about whether passive smoking plays a role, but a

Lancet article in September predicted that in China, among the 240 million

people who are now over 50, 1.9 million who never smoked will die from chronic

lung disease — just from exposure to other people’s smoke.

Many patients with lung disease have other illnesses as well, like heart

disease, acid reflux, hypertension, high cholesterol, sinus problems or

diabetes. Compared with other smokers, those with C.O.P.D. are more likely to

develop lung cancer as well. Researchers suspect that all the ailments stem

partly from the same underlying condition, widespread inflammation, a reaction

by the immune system that can affect blood vessels, organs and tissues all over

the body.

Lung disease can creep up insidiously, because human beings have lung power to

spare. Millions of airways, with enough surface area to cover a tennis court,

provide so much reserve that most people would not notice it if they lost the

use of a third or even half of a lung. But all that extra capacity can hide an

impending disaster.

“If it comes on gradually, the body can adjust,” said Dr. Neil Schachter, a lung

specialist and professor at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York. “Some of

these patients are at oxygen levels where you and I would be gasping for

breath.”

People adjust psychologically as well, cutting back their activities, deciding

perhaps that they just do not enjoy sports anymore, that they are getting older,

gaining weight or a bit out of shape. But at some point the body can no longer

compensate, and denial does not work anymore.

“It’s like trying to breathe through a straw,” Dr. Schachter said. “It’s very

uncomfortable.”

By then, half a lung might be ruined. On a CT scan, he said, the lungs may look

“moth-eaten,” full of holes where tissue has been destroyed.

Often, the diagnosis is not made until the disease is advanced. Even though

breathing tests are easy to perform and recommended for high-risk patients like

former and current smokers, many doctors do not bother. People who do get a

diagnosis frequently are not taught how to use the inhalers that are the

mainstay of treatment. Access to pulmonary rehabilitation is limited because

Medicare has left coverage decisions to the states. Some programs have shut

down, and there are bills in the House and Senate that would require pulmonary

rehabilitation to be covered by Medicare. Medicare may also reduce coverage for

home oxygen.

Meanwhile, billions are spent on treating exacerbations, episodes of severe

breathing trouble that are often caused by colds, flu or other respiratory

infections.

A recent study of 1,600 consecutive hospitalizations for chronic lung disease in

five New York hospitals found that once patients were in the hospital, their

treatment was generally correct, Dr. Thomashow said. But “most upsetting,” he

said, was that the majority had been incorrectly treated before going to the

hospital.

For many, trying to control the disease, rather than be controlled by it, is a

daily struggle. Diane Williams Hymons, 57, a social service consultant and

therapist in Silver Spring, Md., has had lifelong problems with bronchitis,

allergies and asthma. In the last five or 10 years, her breathing difficulties

have worsened, but she was told only three years ago that she had C.O.P.D. It

motivated her to give up cigarettes, after smoking for more than 30 years.

“I have good days, and days that aren’t as great,” she said. “I sometimes have

trouble walking up steps. I have to stop and catch my breath.”

She is “usually fine” when sitting, she said.

Her mother, also a former smoker with chronic lung disease, has been in a

pulmonary rehabilitation program. Ms. Williams Hymons’s doctor has not

recommended such a program for her, but she has no idea why. They have discussed

surgery to remove part of her lungs, which helps some people with emphysema, but

she said no decision had been made yet because it is not clear whether her main

problem is emphysema or asthma. She is not sure what her prognosis is.

A Risky Approach

Ms. Williams Hymons has been taking prednisone pills for years, something both

she and her doctor know is risky. But when she tries to cut back, the disease

flares up. She has many side effects from the drug.

“My bone density is not looking real good,” she said. “I have cramps in my hands

and feet, weight gain and bloating, the moon face, excess facial hair, fat

deposits between my shoulder blades. Yes, I have those.”

She has broken two ribs just from coughing, probably because the prednisone has

thinned her bones, she said. She went to a hospital for the rib pain last year

and was given so much asthma medication to stop the coughing that it caused

abnormal heart rhythms. She wound up in the cardiac unit for five days, and now

says “never again” to being hospitalized.

Her doctor orders regular bone density tests.

“I know he’s concerned, like I’m concerned,” Ms. Williams Hymons said, “but we

can’t seem to kind of get things under control.”

A recent study of 25 primary care practices around the United States treating

chronic lung disease found that most did not perform spirometry, a simple

breathing test used to diagnose or monitor the disease, even when they had the

equipment to do so. The test takes only a few minutes, but doctors said there

was not enough time during the usual 15-minute visit. Similarly, the practices

did not offer much help with smoking cessation.

The author of the study (published in August in The American Journal of

Medicine), Pamela L. Moore, said many of the doctors felt unable to help smokers

quit, and believed that as long as patients kept smoking, treatments for lung

disease would be for nought. But Dr. Moore said research had found that people

are more likely to quit or start cutting back if doctors recommend it.

Labeling the disease self-induced is “an unbelievably painful concept,” Dr.

Thomashow said. “Patients blame themselves, their family blames them, we even

have evidence that health providers blame them.”

Shame and Blame

Indeed, a patient at a clinic in Manhattan, with nasal oxygen tubing attached to

equipment in a backpack, said, “This is one of the evils you must suffer for the

things we did in our life.”

Smoking also contributes to heart disease, Dr. Thomashow said, and yet people

“don’t waste time blaming the patient.”

“This disease quite frankly has an image problem,” said Dr. James Kiley, the

director of lung research at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, which

started a campaign last January to educate people about the disease.

In one way or another every patient seems to have encountered what John Walsh,

president of the C.O.P.D. Foundation, calls the “shame and blame” attached to

this disease.

It is a familiar theme to Ms. Dorney Koppel, who agreed to become a spokeswoman

for the institute’s education campaign. She was surprised to be asked to help,

she said, because the campaign needed a celebrity, and she is merely married to

one. She asked the person who invited her, whether there were no famous people

with C.O.P.D.

“I was told, ‘None who will admit it,’” she said.

Ms. Dorney Koppel, who is candid about being a former smoker, calls the illness

the Rodney Dangerfield of diseases.

“You don’t get no respect,” she said. “I have to pay publicly for my sins. I

have paid.”

Like many patients, Ms. Rommes has both emphysema and chronic bronchitis, along

with asthma. She had symptoms for years before receiving the correct diagnosis.

She began smoking in college during the 1960s, when she was 18. People whom she

admired smoked, and it seemed cool. She smoked for 30 years.

When she quit in 1992, it was not because she thought she was ill, but because

she realized that she was organizing her day around chances to smoke. But she

almost certainly was ill. She was only 50, but climbing a flight of stairs left

her winded. From what she found in medical dictionaries, she began to suspect

she had lung disease.

By 2000 she was so short of breath that she consulted her doctor about it.

He gave her a spirometry test. In one second, healthy adults should be able to

blow out 80 percent of the total they can exhale; her score was 34 percent,

which, she knows now, indicated moderate to severe lung disease.

“I honestly don’t know whether he knew,” she said of her doctor. “I suspect he

did, but he didn’t call it emphysema.”

“He put me on a couple of inhalers and he called it asthma,” Ms. Rommes said. “I

sort of ignored the whole thing, because the inhalers did make me feel better. I

started to gain some weight, and things got progressively worse.”

She cannot help wondering now if she could have avoided becoming so desperately

ill, if she had only known sooner what a dangerous illness she had.

The turning point came in February 2003 when she tried to take a shower and

found that she could not breathe. The steam all but suffocated her. She managed

to drive from her home in Osceola, Iowa, to her doctor’s office, struggle across

the parking lot like someone climbing a mountain and collapse, gasping, onto a

couch inside the clinic. Her blood oxygen was perilously low, two-thirds of

normal, even when she was given oxygen. The hospital was next door, and her

doctor had her admitted immediately.

Fear and Anger

She had Type 2 diabetes as well as lung disease, and her doctor told her that

losing weight would help both illnesses. But she said, “He made it pretty clear

that he didn’t think I would or could.”

Motivated by fear and anger, she began riding an exercise bike, walking on a

treadmill, lifting weights at a gym and eating only 1,200 to 1,500 calories a

day, mostly lean meat with plenty of vegetables and fruit.

“I kind of came to the conclusion that if I didn’t, I probably wasn’t going to

be around,” Ms. Rommes said. “I wasn’t ready to check out. And my husband was

beginning to show the signs of Alzheimer’s disease. I knew that if I couldn’t

continue to manage our affairs, it wasn’t going to work out.”

By December 2003, her efforts were starting to pay off. She went from needing

oxygen around the clock to using it only for sleeping, and by January 2005 she

no longer needed it at all. She was able to lower the doses of her inhalers and

diabetes medicines. By February 2005, she had lost 100 pounds.

The daily exercise also helped her deal with the stress of her husband’s

illness. He died in June.

“I had no clue that exercise would do as much for ability to breathe as it did,”

she said, adding that it helped more than the drugs, which she described as

“really pretty minimal.”

She is hooked on exercise now, getting up every morning at 5 a.m. to walk for 45

minutes on the treadmill. She goes at it hard enough to break a sweat, wearing a

blood oxygen monitor to make sure her level does not dip too low (if it does,

she slows down or uses special breathing techniques to bring it up). She walks

outdoors, as well, and three times a week, she works out with weights at a gym.

“Exercise is absolutely essential, and it’s essential to start it as soon as you

know you have C.O.P.D.,” she said.

Exercise does not heal or strengthen the lungs themselves, but it improves

overall fitness, which people with lung disease need desperately because their

shortness of breath leads to inactivity, muscle wasting and loss of stamina.

“Both my pulmonologist and my regular doctor have made it really, really clear

to me that I have not increased my lung capacity at all,” Ms. Rommes said. “But

I’ve improved the mechanics. I’ve done everything I know how to do to make the

lung capacity as efficient as possible. That’s the key for me; I know there are

lots of people with this disease who don’t exercise, who I guess just give up.”

She realizes that she has two serious chronic diseases that could shorten her

life. But it does not worry her much, she said, because she figures she is doing

everything she can to take care of herself, and would rather spend her time

enjoying life — work, reading, opera, traveling, children and grandchildren.

“I will tell pretty much anybody that I have emphysema,” Ms. Rommes said. “They

say, ‘Did you smoke?’ I say, ‘Yes I did, for 30 years, and I quit in 1992.’

Maybe it’s why I’ve attacked this the way I did. O.K., I did it to myself, and

so I better do everything I can to get out of it. We all do things in our lives

that are stupid, and then you do what you can to fix it.”

From Smoking Boom, a

Major Killer of Women, NYT, 29.11.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/29/health/29lung.html

States Slow

to Ban Restaurant Trans Fats

November 27, 2007

Filed at 7:52 p.m. ET

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

The New York Times

COLUMBUS, Ohio (AP) -- States from Connecticut to California

have looked this year to mimic the success of large cities like New York in

banning artery-clogging trans fats from restaurants.

But in the 14 states that have so far proposed a ban or restriction, not a

single bill has been passed as the year draws to a close. This month, Ohio

became the 15th state to make such a proposal.

New bills often take time to wind their way through committees and come up for a

vote. But the legislation has also faced strong opposition from the National

Restaurant Association and its state-level affiliates -- although the

Massachusetts' group recently said it wouldn't fight that state's bill.

The national association says it doesn't oppose phasing out trans fats but

objects to what it calls ''inflexible bans with unrealistic timetables.''

''It's not as easy as just dumping in a new oil,'' said Sheila Weiss, director

of nutrition policy for the group.

A voluntary, gradual approach would ''significantly diminish the impact and

unintended consequences of an outright ban,'' Richard Mason, lobbyist for the

Ohio Restaurant Association, wrote in a letter to Ohio's trans fat bill sponsor.

The industry points to the voluntary no-trans-fat movements at fast-food

restaurants such as Wendy's, KFC and Taco Bell to emphasize to lawmakers that

there's no need to get government involved. A ban could force restaurants to

switch to saturated fats -- which also contribute to heart disease -- if they

haven't had time to find a healthier alternative, the industry says.

But proponents of the bills said it's relatively easy to switch to other oils

such as canola or corn oil, pointing to New York City, where restaurants have

complied with the ban's first phase -- which applies to oils, shortening and

margarine used for frying and spreading -- without much fanfare.

Sylvia's, a soul food restaurant in Manhattan, said it switched to frying

without trans fat oil before the city's ban went into effect in July. The

transition was easy except for a few desserts, said restaurant marketing

director Trenness Woods-Black.

''We switched and no one noticed the difference. We still have super crispy

fried chicken,'' she said.

But some bakeries around the country have said it's hard to make baked goods

with the same quality without trans fats. The main source of trans fat is

partially hydrogenated oils, created when hydrogen is added to liquid cooking

oils to harden them for baking or for a longer shelf life.

The Philadelphia City Council approved a bill to exempt bakeries from that

city's ban after many bakeries complained.

Critics say the restaurant group's argument is undercut by the success

restaurants have had getting rid of trans fats.

''The restaurant association has a very strong lobbying effort and they've made

a major effort to keep this from getting passed,'' said Julie Greenstein, deputy

director for health promotion policy at the Center for Science in the Public

Interest in Washington. In many cases, the center has been the driving force

behind trans fat bills.

A New York Democratic legislator, Felix Ortiz, has been trying since 2004 to get

a trans fat restriction into state law. But the restaurant industry has

cultivated members on key committees, Ortiz said. His latest bill focuses on

chain restaurants.

''We are going to get it done,'' said Ortiz, who pushed through New York's ban

on talking on a cell phone while driving.

The other states that have proposed a ban or restriction on trans fats in

restaurants are Maryland, Michigan, Illinois, New Jersey, New Hampshire, Rhode

Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Vermont and Hawaii.

------

On the Net:

http://www.restaurant.org

http://www.cspinet.org

States Slow to Ban

Restaurant Trans Fats, NYT, 28.11.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/us/AP-Diet-Trans-Fat-States.html

Felix Sockwell

Health Care: A National Conversation

NYT 28.11.2007

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/28/opinion/lweb28health.html

Letters

Health Care: A National Conversation

November 28, 2007

The New York Times

To the Editor:

“The High Cost of Health Care”

(editorial, Nov. 25) captures the true complexities facing the challenges of the

American health care system.

Those who truly immerse themselves in the issues of health care are well aware

that indeed reform is not near, nor will it ever be achieved until there is a

fundamental compromise on all the matters outlined.

The greatest obstacle to achieving universal health care will come from those

who choose to avoid these fundamental issues while guided only by their

political ambitions.

Reno DiScala, M.D.

Glen Cove, N.Y., Nov. 25, 2007

•

To the Editor:

Your otherwise thoughtful editorial about the health care crisis facing the

United States curiously dismisses the idea of a single-payer health care plan as

“no panacea” for the cost problem and as having “limited political support.”

But the question isn’t whether a single-payer plan is a panacea — it is whether

a single-payer plan would significantly reduce costs compared with

insurance-based plans, and the answer is a decided yes.

The administrative costs of Medicare are approximately 20 percent of the

administrative costs of private insurance plans, and all of those administrative

savings in a comprehensive Medicare-for-all system could be poured into more and

better health care.

As to whether a single-payer plan has political support, it depends on whether

you ask the average person or the average politician. Whereas polls show that a

majority of the people favor a single-payer plan, the politicians, many of whom

are beholden to the insurance industry, would like you to believe otherwise.

Instead of wringing your hands about the supposed unworkability and unpopularity

of a single-payer plan (even in the face of the highly successful and popular

Medicare, with a 40-year track record), The Times should put its considerable

influence behind the only real solution to the health care crisis: Medicare for

all.

Peter Hanauer

Berkeley, Calif., Nov. 25, 2007

•

To the Editor:

A single-payer, government-run system was only briefly mentioned and was

immediately dismissed as “no panacea for the cost problem.” The truth is that

single-payer, government-run health care has been a panacea.

In the 46 years that I’ve practiced family medicine, I’ve found Medicare,

Medicaid, the Veterans Administration, all of them single-payer

government-administered health care programs, more predictable, uniform and

reliable than the for-profit health care insurance companies. This is better for

doctors and hospitals and certainly better for the patients.

I like one form to file, one payer, one set of rules for everyone and the

assurance that everyone has health care coverage when patients come to see me.

Melvin H. Kirschner, M.D.

Van Nuys, Calif., Nov. 25, 2007

•

To the Editor:

With regard to “The High Cost of Health Care,” the amount we spend on health

care, while troubling, should not be the main issue in the great health care

debate. The focus should be on two things: one, the 47 million uninsured who

cannot regularly participate in the health care system (not all of which is due

to the high cost); and two, the poor state of our nation’s health in comparison

to other countries that spend far less in this area.

Many of our citizens do not have good health, despite the expensive technology,

drugs and specialists indicative of our health care system. Our infant mortality

rate remains high in comparison to other nations, and older adults live many

years with chronic illness and disability.

We can expect many of our health status indicators to get worse, not better, in

the coming decades as our uninsured population grows, our minority and immigrant

populations grow, and as baby boomers age.

These demographic influences are the rationale for the Healthy People 2010 goals

of reducing racial and ethnic health disparities and extending years of healthy

life. We are the richest nation. First, let’s allocate our economic, medical and

research resources to provide good health to every American; then we can figure

out how to do it cost-effectively.

Jan Warren-Findlow

Charlotte, N.C., Nov. 25, 2007

The writer is an assistant professor of public health sciences, University of

North Carolina at Charlotte.

•

To the Editor:

The Times is right to call health care costs “the worst long-term fiscal crisis

facing the nation.”

Although universal coverage could be cheaper to finance and easier to

administer, few concur on how to preserve consumer choice or how to persuade the

uninsured to buy into the system.

Here’s how:

Extend Medicare coverage to all, financed by an increase in the withholding tax

and elimination of the tax subsidies for employee health insurance. Those

willing to settle on a Canadian-style system can have one, but those wanting to

opt out could receive a tax credit to buy alternative or supplemental policies

offered by the private market.

Insurers would be required to accept all applicants and offer community rates,

with the government underwriting catastrophic costs above a defined level.

The Medicare withholding tax could be progressively structured and the credit

capped to provide fairness.

Allan Ostergren

Director, Institute for SocioEconomic Studies

White Plains, Nov. 26, 2007

•

To the Editor:

I would certainly not agree with “almost all economists” that “the main driver

of high medical spending here is our wealth.” The per capita income of Americans

is less than that of several European countries, and certainly not enough to

explain our spending twice as much per capita on health care.

Where we are unique is in leaving most of our health system to the tender

mercies of profit-maximizing investor-owned businesses.

You are right that Medicare-for-all “is no panacea for the cost problem.” As now

structured, Medicare pays specialists extravagant fees to perform tests and

procedures, which drives up costs. But it could easily be reformed. In any case,

some sort of single-payer system will be necessary to control costs, even if not

sufficient.

Marcia Angell, M.D.

Cambridge, Mass., Nov. 25, 2007

The writer is a senior lecturer in social medicine at Harvard Medical School and

a former editor in chief of The New England Journal of Medicine.

•

To the Editor:

Have any of us ever recommended a physician based on his or her prudent

allotment of health care dollars? The cardiologist who forgoes cardiac

catheterization in your elderly grandmother because her short life expectancy

doesn’t justify the expense? The neonatologist who declines to aggressively

resuscitate your premature newborn because its tiny chance of intact survival

doesn’t justify the astronomical cost of months of neonatal intensive care? The

emergency medicine doctor who refuses to med-flight your teenager after a deadly

car crash because he isn’t going to make it anyway?

It’s easy to blame doctors for spending lavishly on their patients. But it is

simply hypocritical for patients to criticize the spendthrift culture of

American medicine while continuing to demand any intervention available despite

its high cost and/or low likelihood of benefit.

There’s no such thing as a free lunch.

Joshua U. Klein, M.D.

Brookline, Mass., Nov. 25, 2007

•

To the Editor:

Several states are already pursuing their own health care payment programs. The

federal government should not develop a one-size-fits-all national program but

rather encourage all of the states to develop programs. Placing the

responsibility for financing and administering the program at the state level

would preserve the disparities in expenditures on health care from one region to

another; it would foster experimentation and competition among states to develop

and carry out cost-saving strategies.

As the state programs prove themselves, even Medicare might be delegated to

them.

John A. Rowland

Rocky River, Ohio, Nov. 26, 2007

•

To the Editor:

With malpractice insurance approaching $100,000 a year for many health care

providers, litigation plays more than a “minor role” in driving up costs. How

often do physicians recommend additional treatments just to avoid a potential

lawsuit?

Does the legal environment diminish the availability of quality health care by

reducing the supply and increasing the cost? How many patients are put at

increased risk, and forced to pay higher costs, simply because of a hostile

attitude toward the medical profession by often-greedy lawyers?

Malpractice occasionally occurs, and there should be remedies for those who are

harmed. But there’s an army of litigators out there who are eager to generate

income at the expense of the system. Why else would so many trial lawyers make

substantial contributions to politicians who are willing to ignore any

possibility of medical liability reform?

Health care costs cannot be contained without addressing the legal issues.

William L. Burge

Ballwin, Mo., Nov. 25, 2007

•

To the Editor:

Missing from the editorial was the problems we face in end-of-life care and its

effect on all of medicine. Although hospice use has increased, so has the number

of people dying in intensive care units. Thousands, perhaps hundreds of

thousands, of nursing home patients each year are transferred to hospitals for

acute care from which they can derive no benefit because of that person’s

underlying health.

This type of care is more prevalent in our large teaching hospitals, training

young doctors that inappropriate, expensive care is the norm, which has

contributed to the widespread excessive use of procedures and drugs.

It takes judgment to determine what is suitable for each individual’s unique

health situation. Any solution to our health care problem must emphasize

appropriate care tailored to the individual needs of every patient.

Kenneth A. Fisher, M.D.

Kalamazoo, Mich., Nov. 26, 2007

Health Care: A National

Conversation, NYT, 28.11.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/28/opinion/lweb28health.html

Editorial

The High Cost of Health Care

November 25, 2007

The New York Times

The relentless, decades-long rise in the cost of health care has left many

Americans struggling to pay their medical bills. Workers complain that they

cannot afford high premiums for health insurance. Patients forgo recommended

care rather than pay the out-of-pocket costs. Employers are cutting back or

eliminating health benefits, forcing millions more people into the ranks of the

uninsured. And state and federal governments strain to meet the expanding costs

of public programs like Medicaid and Medicare.

Health care costs are far higher in the United States than in any other advanced

nation, whether measured in total dollars spent, as a percentage of the economy,

or on a per capita basis. And health costs here have been rising significantly

faster than the overall economy or personal incomes for more than 40 years, a

trend that cannot continue forever.

It is the worst long-term fiscal crisis facing the nation, and it demands a

solution, but finding one will not be easy or palatable.

The Causes

Varied and Deep-Rooted. Contrary to popular beliefs, this is not a problem

driven mainly by the aging of the baby boom generation, or the high cost of

prescription drugs, or medical malpractice litigation that spawns defensive

medicine. Those issues often dominate political discourse, but they have played

relatively minor roles in driving up medical spending in this country and

abroad. The major causes are much more deep-seated and far harder to root out.

Almost all economists would agree that the main driver of high medical spending

here is our wealth. We are richer than other countries and so willing to spend

more. But authoritative analyses have found that we spend well above what mere

wealth would predict.

This is mostly because we pay hospitals and doctors more than most other

countries do. We rely more on costly specialists, who overuse advanced

technologies, like CT scans and M.R.I. machines, and who resort to costly

surgical or medical procedures a lot more than doctors in other countries do.

Perverse insurance incentives entice doctors and patients to use expensive

medical services more than is warranted. And our fragmented array of insurers

and providers eats up a lot of money in administrative costs, marketing expenses

and profits that do not afflict government-run systems abroad.

Does It Matter? If citizens of an extremely wealthy nation like the United

States want to spend more on health care and less on a third car, a new computer

or a vacation home, what’s wrong with that? By some measures, Americans are

getting good value. Studies by reputable economists have concluded that spending

on such advanced treatments as cardiac drugs, devices and surgery; neonatal care

for low-birth-weight infants; and mental health drugs have more than paid for

themselves by extending lives and improving their quality.

But if health care spending continues on its same trajectory, the United States

will reach the point — probably several decades from now — where every penny of

the annual increase in gross domestic product would have to go for health care.

There would be less and less money for other things, like education,

environmental protection, scientific research and national security, that may be

equally or more important to the well-being of society.

Governmental budgets will face the crisis even sooner. States are already

complaining that they have to crimp other vital activities, like education, to

meet soaring Medicaid costs. And federal spending on Medicare and Medicaid is

surging upward at rates that will cause the deficit to soar. That means

politicians will have to raise taxes, severely cut a wide range of other

governmental programs, or chop back the health programs themselves.

The question is: What can be done to lower both the high level of health care

spending and its high rate of increase from year to year?

The Solutions

Geography. Pioneering studies by researchers at Dartmouth have shown enormous

disparities in expenditures on health care from one region to another with no

discernible difference in health outcomes. Doctors in high-cost areas use

hospitals, costly technology and platoons of consulting physicians a lot more

often than doctors in low-cost areas, yet their patients, on average, fare no

better. There are hints that they may even do worse because they pick up

infections in the hospital and because having a horde of doctors can mean no one

is in charge.

If the entire nation could bring its costs down to match the lower-spending

regions, the country could cut perhaps 20 to 30 percent off its health care

bill, a tremendous saving. That would require changing the long- ingrained

practices of the medical profession. Public and private insurers might need to

refuse coverage for high-cost care that adds little value.

Stick to What Works. The sad truth is that less than half of all medical care in

the United States is supported by good evidence that it works, according to

estimates cited by the Congressional Budget Office. If doctors had better

information on which treatments work best for which patients, and whether the

benefits were commensurate with the costs, needless treatment could be junked,

the savings could be substantial, and patient care would surely improve. It

could take a decade, or several, to conduct comparative-effectiveness studies,

modify relevant laws, and change doctors’ behavior.

Managed Care. For a brief period in the 1990s it looked as if health maintenance

organizations competing for patients and carefully managing their care might

bring down costs and improve quality at the same time. The H.M.O.’s did help

restrain costs for a few years. The problem was, doctors and patients hated the

system, management became much looser, and the upsurge in costs resumed. Managed

care techniques are creeping back into some health plans, especially for

services apt to be overused, but too heavy a hand would most likely produce

another backlash.

Information Technologies. The American health care system lags well behind other

sectors of the economy — and behind foreign medical systems — in adopting

computers, electronic health records and information-sharing technologies that

can greatly boost productivity. There is little doubt that widespread

computerization could greatly reduce the paperwork burden on doctors and

hospitals, head off medication errors, and reduce the costly repetition of

diagnostic tests as patients move from one doctor to another. Without an

infusion of capital, the transition from paper records is not apt to happen very

quickly.

Prevention. Everyone seems to be hoping that preventive medicine — like weight

control, exercise, better nutrition, smoking cessation, regular checkups,

aggressive screening and judicious use of drugs to reduce risks — will not only

improve health but also lower costs in the long run. Preventive medicine

actually costs money — somebody has to spend time counseling patients and

screening them for disease — and it is not clear how soon, or even whether,

substantial savings will show up. Still, the effort has to be made. The Milken

Institute recently estimated that the most common chronic diseases cost the

economy more than $1 trillion annually, mostly from lost worker productivity,

which could balloon to nearly $6 trillion by the middle of the century.

Disease Management. Virtually all policy experts want more careful coordination

of the care of chronically ill patients, who account for the largest portion of

the nation’s health care expenditures. Although that should improve the quality

of the care they get, coordination may not cut costs as substantially as people

expect. In some initial trials it has cut costs, in others not.

Drug Prices. Compared with the residents of other countries, Americans pay much

more for brand-name prescription drugs, less for generic and over-the-counter

drugs, and roughly the same prices for biologics. This page believes it would be

beneficial to allow Medicare to negotiate with manufacturers for lower

prescription drug prices and to allow cheaper drugs to be imported from abroad.

The prospect for big savings is dubious.

Who Picks Up the Tab?

Pay Providers Less. With doctors dreadfully unhappy under the heavy hand of

insurers, it would seem shortsighted to make them even unhappier by cutting

their compensation to levels paid in other countries. But many experts believe

it should be possible to tap into the vast flow of money sluicing through

hospitals, nursing homes and other health care facilities to find savings.

Emphasize Primary Care. In a health system as uncoordinated as ours, many

experts believe we could get better health results, possibly for less cost, if

we changed reimbursement formulas and medical education programs to reward and

produce more primary care doctors and fewer specialists inclined to proliferate

high-cost services. It would be a long-term project.

Skin in the Game. The solution favored by many conservatives is to force

consumers to shell out more money when they seek medical care so that they will

think harder about whether it is really necessary. The “consumer-directed health

care” movement calls for providing people with enough information about doctors

and treatments so that they can make wise decisions.

There would most likely be some savings. A classic experiment by Rand

researchers from 1974 to 1982 found that people who had to pay almost all of

their own medical bills spent 30 percent less on health care than those whose

insurance covered all their costs, with little or no difference in health

outcomes. The one exception was low-income people in poor health, who went

without care they needed. Any cost-sharing scheme would have to protect those

unable to bear the burden.

And consumer-driven plans have limitations. Most health care spending is racked

up by a small percentage of individuals whose bills are so high they are no

longer subject to cost sharing; they will hardly be deterred from expensive care

they desperately need. Moreover, few consumers have the competence or knowledge

to second-guess a doctor’s recommendations.

Single Payer. Deep in their hearts, many liberals yearn for a single-payer

system, sometimes called Medicare-for-all, that would have the federal

government pay for all care and dictate prices. Such a system would let the

government offset the price-setting strength of the medical and pharmaceutical

industries, eliminate much of the waste due to a multiplicity of private

insurance plans, and greatly cut administrative costs.

But a single-payer system is no panacea for the cost problem — witness

Medicare’s own cost troubles — and the approach has limited political support.

Private insurers could presumably eliminate some of the waste through uniform

billing and payment procedures.

•

By now it should be clear that there is no silver bullet to restrain soaring

health care costs. A wide range of contributing factors needs to be tackled

simultaneously, with no guarantee they will have a substantial impact any time

soon. In many cases we do not have enough solid information to know how to cut

costs without impairing quality. So we need to get cracking on a range of

solutions. The cascade of knowledge flowing from the human genome project, new

nanotechnologies and the advent of treatments tailor-made for individual

patients may well accelerate, not mitigate, the rise in medical spending. If we

want the benefits, we will need to make them affordable.

The High Cost of Health

Care, NYT, 25.11.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/25/opinion/25sun1.html

Letters

Getting

to Know Your DNA

November

23, 2007

The New York Times

To the

Editor:

Re “My Genome, Myself: Seeking Clues in DNA” (“The DNA Age” series, front page,

Nov. 17):

Wanting to know more about ourselves is both a strength and a hazard. The lure

of genetic data can be compelling but misleading, for no list of tiny variants

in one’s genetic code can reliably predict one’s future regarding cancer, heart

attacks or diabetes, let alone I.Q., addiction or gullibility.

Amy Harmon’s humorous account of her own genome search may still leave many

readers willing to send off a little saliva — and a big check — to a genome

company. Those companies are selling only a fragment of your identity. Knowing

that you have this or that disease-associated SNP in your genes tells you very

little or helps only with rare diseases.

What causes the SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism) to be expressed, to spring

into action or to remain dormant? Why can identical twins, with genomes alike

down to the last SNP, develop different diseases? What if you smoke, toil for

years in a high-stress job or live in a polluted neighborhood?

Predispositions are just the beginning. Your future depends on much more than

your genetic code. Ms. Harmon would have done better to spend her money on a

good gym, and The Times would serve us better by emphasizing the limits of

genetic knowledge.

Susan M. Reverby, Ph.D.

Jay Kaufman, Ph.D.

H. Jack Geiger, M.D.

Cambridge, Mass., Nov. 18, 2007

Dr. Reverby is professor of the history of ideas at Wellesley College; Dr.

Kaufman is associate professor of epidemiology at the University of North

Carolina, Chapel Hill; and Dr. Geiger is emeritus professor of community

medicine at City University of New York Medical School.

•

To the Editor:

The exposé on surfing for one’s genome demonstrates the slipperiness of tapping

genetic information. Personally, I’d rather not know about my predilection for

certain tastes mainly because it would take the fun out of trying new foods.

(Not the cream of lobster: I’m lactose-intolerant and lack the taste gene for

bottom-feeding sea creatures!!)

Yet I recognize the importance of genetic research in biology and medicine. The

paradox is that to make intellectual strides, society must accept some risk.

People should recognize that a wealth of both critical and inconsequential

genetic information is becoming available. But within privacy laws, they should

also be able to keep the right to choose the movies they watch, the Web sites

they frequent and how much they want to learn about their genetic potential.

Andrew Zinn, M.D.

Kew Gardens, Queens, Nov. 17, 2007

•

To the Editor:

Amy Harmon mentions the risk that insurers might deny coverage based on future

availability of a person’s detailed genetic information. The future also poses a

risk that employers could misuse genetic screening and data.

Since 1990, most states have passed laws to prevent genetic discrimination, but

federal protection is essential. The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act

of 2007 was passed by the House this spring; Senator Olympia Snowe, Republican

of Maine, has proposed a Senate version. If you are worried about such

discrimination (and you should be), contact your senators to voice your support

of this legislation.

Katherine Brokaw

Atlanta, Nov. 17, 2007

•

To the Editor:

The real news is that the genetic genie is out of the bottle. The consumer’s

embrace of genetic analysis is now unstoppable. And though the medical community

warns how little we can actually learn from most of our genes, these caveats do

not diminish our curiosity.

The truth is that the medical establishment has not co-opted the genetic

paradigm because doctors are busy and see little value right now for themselves

or their patients. As such, genetics may go the way of cosmetic dermatology and

surgery.

Hugh Young Rienhoff Jr., M.D.

San Francisco, Nov. 18, 2007

The writer is director of MyDaughtersDNA.org., a forum on genetics.

Getting to Know Your DNA, NYT, 23.11.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/23/opinion/l23dna.html

Analysis: Hurdles Remain for Stem Cells

November

22, 2007

Filed at 12:51 a.m. ET

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

The New York Times

NEW YORK

(AP) -- For all the excitement, big questions remain about how to turn this

week's stem cell breakthrough into new treatments for the sick. And it's not

clear when they'll be answered.

Scientists have to learn more about the new kind of cell the landmark research

produced. They have to find a different way to make it, to avoid a risk of

cancer. And even after that, there are plenty of steps needed to harness this

laboratory advance for therapy.

So if you ask when doctors and patients will see new treatments, scientists can

only hedge.

''I just can't tell you dates,'' says James Thomson of the University of

Wisconsin-Madison, one of the scientists in the U.S. and Japan who announced the

breakthrough on Tuesday.

''The short answer is: It's still going to be years,'' Dr. John Gearhart, a stem

cell expert at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine who was familiar with the

work, said Wednesday.

Such a delay isn't unusual. It can often take a long time for medical payoffs to

flow from basic scientific findings.

For example, the inspiration for a group of cystic fibrosis drugs now being

tested in people or animals goes back 18 years to a genetic discovery. And more

generally, gene therapy -- the notion of fixing or replacing defective genes --

has been studied in people for more than 15 years without much success.

At least, federal money for research into the new kind of cell won't be a

problem, said Story Landis, head of the National Institutes of Health's Stem

Cell Task Force. The task force is about to invite scientists to apply for new

grants for such work, she said.

This week's advance has apparently solved a supply problem for the study of

embryonic stem cells. These cells are valued for their ability to morph into any

of the cell types of the body. Scientists had long searched for a way to produce

embryonic cells that carry the genes of a particular person.

Such cells could be used for at least three purposes. The most highly publicized

one is to create transplant tissue for treating disease. In the shorter term,

they could be used to create ''diseases in a dish,'' colonies of cells bearing

illness-promoting genes that could reveal the vulnerable roots of medical

conditions. And finally, scientists could use such cells for rapidly screening

potential medicines in the laboratory.

Until this week's announcement, scientists who wanted to make such cells looked

to an expensive, cumbersome cloning process that destroyed embryos, making it an

ethical lightning rod. And it hadn't yet worked with human embryos.

The new technique is much simpler. It makes human skin cells behave like

embryonic stem cells without using embryos at all.

End of problem? Not unless these altered skin cells can truly replace embryonic

cells, and that's not clear yet, a prominent scientist says.

Paul Berg, a Stanford University Nobel laureate who helped establish federal

guidelines for human research on genetically manipulated cells, said the

celebration over this week's announcement is premature.

''I'm amazed at the ethicists'' saying the problem of needing embryos has been

solved, Berg said. ''We're not in the clear -- this is a first step.''

So what are the next steps?

The first basic question to solve is how similar iPS cells are in behavior and

potential to the embryonic cells that scientists have studied for nearly a

decade.

''My guess is that we'll find that there are significant differences,'' said Dr.

Robert Lanza of Advanced Cell Technology, which has been trying to produce stem

cells from cloned human embryos. ''I'd be surprised if these cells can do all

the same tricks as well as stem cells derived from embryos.''

Another big question is how to make iPS cells in a different way. The

breakthrough technique treats skin cells by using viruses to carry in a quartet

of genes. Those viruses disrupt the DNA of the skin cells. When that happens,

there's a risk of cancer.

That's show-stopper when it comes to creating tissue to transplant into people.

So scientists have to figure out a way to make iPS cells without those

DNA-disrupting viruses.

Scientists should be able to find other ways to slip the genes into the skin

cells, Thomson said. Other scientists suggest that a purely chemical treatment,

not inserting genes at all, might be able to get the same result.

The cancer-risk problem should be solved quickly, maybe within a year or so,

said Doug Melton, co-director of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute.

Before then, iPS cells could be used in lab studies to study the early roots of

genetic disease or to screen drugs. But of course, it's anybody's guess when a

useful treatment would result from that.

Even with the cancer problem solved for transplant uses, there's another big

hurdle:

The whole idea of using embryonic stem cells or iPS cells for treating people

with conditions like diabetes and Parkinson's disease via transplant is itself

far from proven. Scientists will need to learn how to turn iPS cells into the

right kind of tissue, and how to use that tissue in a way that will treat a

person's disease.

Such studies, in the lab, animals and finally people, will take years.

As far as that obstacle goes, Thomson said, the breakthrough announced this week

changes nothing.

''We have a lot of work to do.''

------

AP Medical Writer Marilynn Marchione contributed to this story from Milwaukee.

Analysis: Hurdles Remain for Stem Cells, NYT, 22.11.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/us/AP-Stem-Cells.html

Man Who

Helped Start Stem Cell War May End It

November

22, 2007

The New York Times

By GINA KOLATA

If the stem

cell wars are indeed nearly over, no one will savor the peace more than James A.

Thomson.

Dr. Thomson’s laboratory at the University of Wisconsin was one of two that in

1998 plucked stem cells from human embryos for the first time, destroying the

embryos in the process and touching off a divisive national debate.

And on Tuesday, his laboratory was one of two that reported a new way to turn

ordinary human skin cells into what appear to be embryonic stem cells without

ever using a human embryo.

The fact is, Dr. Thomson said in an interview, he had ethical concerns about

embryonic research from the outset, even though he knew that such research

offered insights into human development and the potential for powerful new

treatments for disease.

“If human embryonic stem cell research does not make you at least a little bit

uncomfortable, you have not thought about it enough,” he said. “I thought long

and hard about whether I would do it.”

He decided in the end to go ahead, reasoning that the work was important and

that he was using embryos from fertility clinics that would have been destroyed

otherwise. The couples whose sperm and eggs were used to create the embryos had

said they no longer wanted them. Nonetheless, Dr. Thomson said, announcing that

he had obtained human embryonic stem cells was “scary,” adding, “It was not

known how it would be received.”

But he never anticipated the extent and rancor of the stem cell debate. For

nearly a decade now, the issue has bitterly divided patients and politicians,

religious groups and researchers.

Now with the new technique, which involves adding just four genes to ordinary

adult skin cells, it will not be long, he says, before the stem cell wars are a

distant memory. “A decade from now, this will be just a funny historical

footnote,” Dr. Thomson said in the interview.

As for the science behind it, the thrill of discovery, he said, “Surprisingly,

there is no ‘Wow’ moment,” either from 1998 or now. Both times, the discovery

came after he had spent months rigorously testing the cells to be sure they

really were stem cells, worrying all the while that they could die or be lost to

contamination. When he knew he had succeeded, the suspense was gone.

“Imagine holding your breath for a few months,” Dr. Thomson said. When he was

done, he said, “I felt mostly a sense of relief.”

But he knows what he wrought. Stem cells, universal cells that can turn into any

of the body’s 220 cell types, normally emerge only fleetingly after a few days

of embryo development. Scientists want to use them to study complex human

diseases like Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s in a petri dish, finding causes and

treatments. And, they say, it may be possible to use the cells to grow

replacement tissues for patients.

The problem until now had been the source of the cells — human embryos.

The topic, says R. Alta Charo, a University of Wisconsin ethicist, “took on an

almost iconic quality the same way Roe v. Wade has.”

In the meantime, many leading scientists decided not to get into the stem cell

field. There was a stigma attached, Dr. Thomson says. And, he adds, “Most

scientists don’t like controversial things.”

A native of Oak Park, Ill., James Alexander Thomson, 48, did not set out to

throw bioethical bombs. All he wanted, he said, was to answer the most basic

scientific questions about cellular development.

First there was a degree in biophysics from the University of Illinois. As a

graduate student, Dr. Thomson began working with mouse embryonic stem cells and

then, with federal support, he extracted stem cells from monkey embryos. After

earning two doctorates from the University of Pennsylvania, one in veterinary

medicine and one in molecular biology, he continued research at his own

laboratory at the University of Wisconsin.

Eventually he realized, though, that studying mice and monkeys could take him

only so far. If he wanted to understand how human embryos develop and why their

development sometimes goes awry, he needed human stem cells. But, he says, he

hesitated.

In 1995, he began consulting with two ethicists at his university, Dr. Norman

Fost, a physician, and Ms. Charo, a law professor. He wanted to anticipate what

the ethical problems might be and what the criticisms might be.

Dr. Fost was impressed.

“It is unusual in the history of science for a scientist to really want to think

carefully about the ethical implications of his work before he sets out to do

it,” Dr. Fost said. “The biggest problem in ethics is not anticipating

problems.”

But Dr. Fost and Dr. Thomson guessed wrong about what would bother people most.

They thought it would be what Dr. Fost termed “the technological power” of stem

cells. What if someone put human stem cells into the brain of a rat, for

example?

“I thought at the time that this was possibly the biggest issue,” Dr. Fost said.

“It was unprecedented in the history of biology. It’s the ‘Help, get me out of

here’ scenario. Let’s say the rat brain turns out to be entirely human cells.

What’s going on in there? Is it a human brain? And how would you study it — you

can’t ask the rat.”

Meanwhile, as Dr. Thomson was planning his effort to obtain human embryonic stem

cells, another discovery changed his entire view of development. In 1997, Ian

Wilmut, a scientist in Scotland, announced the creation of the first cloned

mammal, Dolly, cloned from frozen udder cells from a long-dead sheep.

Dr. Wilmut had slipped an udder cell — a cell that normally would never be

anything but an udder cell — into an egg whose genetic material had been

removed. The egg somehow brought the udder cell’s chromosomes back to the state

they had been in when embryo development first began.

“Dolly changed the way I thought about developmental biology,” Dr. Thomson says.

“Development was reversible.”

Four years ago he and, independently, Shinya Yamanaka of Kyoto University set

out to figure out a way to mimic what an egg can do. Both succeeded and both

discovered that all they had to do was add four genes to the cells and the cells

would turn into what look, so far, just like stem cells.

“It is actually fairly straightforward to repeat what we have done,” Dr. Thomson

said.

More work remains, but he is confident that the path ahead is clear.

“Isn’t it great to start a field and then to end it,” he said.

Man Who Helped Start Stem Cell War May End It, NYT,

22.11.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/22/science/22stem.html?hp

New Stem

Cell Method Could Ease Ethical Concerns

November

21, 2007

The New York Times

By GINA KOLATA

Two teams

of scientists are reporting today that they turned human skin cells into what

appear to be embryonic stem cells without having to make or destroy an embryo —

a feat that could quell the ethical debate troubling the field.

All they had to do, the scientists said, was add four genes. The genes

reprogrammed the chromosomes of the skin cells, making the cells into blank

slates that should be able to turn into any of the 220 cell types of the human

body, be it heart, brain, blood or bone. Until now, the only way to get such

human universal cells was to pluck them from a human embryo several days after

fertilization, destroying the embryo in the process.

The reprogrammed skin cells may yet prove to have subtle differences from

embryonic stem cells that come directly from human embryos, and the new method

includes potentially risky steps, like introducing a cancer gene. But stem cell

researchers say they are confident that it will not take long to perfect the

method and that today’s drawbacks will prove to be temporary.

Researchers and ethicists not involved in the findings say the work should

reshape the stem cell field. At some time in the near future, they said, today’s

debate over whether it is morally acceptable to create and destroy human embryos

to obtain stem cells should be moot.

“Everyone was waiting for this day to come,” said the Rev. Tadeiusz Pacholczyk,

director of education at the National Catholic Bioethics Center. “You should

have a solution here that will address the moral objections that have been

percolating for years,” he added.

The two independent teams, from Japan and Wisconsin, note that their method also

creates stem cells that genetically match the donor without having to resort to

the controversial step of cloning. If stem cells are used to make replacement

cells and tissues for patients, it would be invaluable to have genetically

matched cells because they would not be rejected by the immune system. Even more

important, scientists say, is that genetically matched cells from patients will

enable them to study complex diseases, like Alzheimer’s, in the lab.

Until now, the only way to get embryonic stem cells that genetically matched an

individual would be to create embryos that were clones of that person and

extract their stem cells. Just last week, scientists in Oregon reported that

they did this with monkeys, but the prospect of doing such experiments in humans

has been ethically fraught.

But with the new method, human cloning for stem cell research, like the creation

of human embryos to extract stem cells, may be unnecessary.

“It really is amazing,” said Dr. Leonard Zon, director of the stem cell program

at Harvard Medical School’s Children’s Hospital.

And, said Dr. Douglas Melton, co-director of the Stem Cell Institute at Harvard

University, it is “ethically uncomplicated.”

For all the hopes invested in it over the past decade, embryonic stem cell

research has not yet produced any cures or major therapeutic discoveries. Stem

cells are so malleable that they may pose risk of cancer, and the new method of

obtaining stem cells includes steps that raise their own safety concerns.

Still, the new work could allow the field to vault significant problems,

including the shortage of human embryonic stem cells and restrictions on federal

funding for such research. Even when scientists have other sources of funding,

they report that it is expensive and difficult to find women who will provide

eggs for such research.

The new discovery is being published online today in Cell, in a paper by Shinya

Yamanaka of Kyoto University and the Gladstone Institute for Cardiovascular

Disease in San Francisco, and in Science, in a paper by James Thomson and his

colleagues at the University of Wisconsin.

While both groups used just four genes to reprogram human skin cells, two of the

four genes used by the Japanese scientists were different from two of the four

used by the American group. All the genes in question, though, act in a similar

way – they are master regulator genes whose role is to turn other genes on or

off.

The reprogrammed cells, the scientists report, appear to behave exactly like

human embryonic stem cells.

“By any means we test them they are the same as embryonic stem cells,” Dr.

Thomson says.

He and Dr. Yamanaka caution, though, that they still must confirm that the

reprogrammed human skin cells really are the same as stem cells they get from

embryos. And while those studies are underway, Dr. Thomson and others say, it

would be premature to abandon research with stem cells taken from human embryos.

Another caveat is that , so far, scientists use a type of virus, a retrovirus,

to insert the genes into the cells’ chromosomes. Retroviruses slip genes into

chromosomes at random, sometimes causing mutations that can make normal cells

turn into cancers.

In addition, one of the genes that the Japanese scientists insert actually is a

cancer gene.

The cancer risk means that the resulting stem cells would not be suitable for

replacement cells or tissues for patients with diseases, like diabetes, in which

their own cells die. They would, though, be ideal for the sort of studies that

many researchers say are the real promise of this endeavor — studying the causes

and treatments of complex diseases.

For example, researchers want to make embryonic stem cells from a person with a

disease like Alzheimer’s and turn the stem cells into nerve cells in a petri

dish. Then, scientists hope, they may be able to understand what goes awry in

Alzheimer’s patients when their brain cells die and how to prevent or treat the

disease.

But even the retrovirus drawback may be temporary, scientists say. Dr. Yamanaka

and several other researchers are trying to get the same effect by adding

chemicals or using more benign viruses to get the genes into cells. They say

they are starting to see success.

It is only a matter of time until retroviruses are not needed, Dr. Melton

predicted.

“Anyone who is going to suggest that this is just a side show and that it won’t

work is wrong,” Dr. Melton said.

The new discovery was preceded by work in mice. Last year, Dr. Yamanaka

published a paper showing that he could add four genes to mouse cells and turn

them into mouse embryonic stem cells.

He even completed the ultimate test to show that the resulting stem cells could

become any type of mouse cell. He used them to create new mice, whose every cell

came from one of those stem cells. Twenty percent of those mice, though,

developed cancer, illustrating the risk of using retroviruses and a cancer gene

to make cells for replacement parts.

Scientists were electrified by the reprogramming discovery, Dr. Melton said.

“Once it worked, I hit my forehead and said, ‘it’s so obvious,’ ”he said. “But

it’s not obvious until it’s done.”

Some were skeptical about Dr. Yamanaka’s work and questioned whether such an

approach would ever work in humans.

“They said, ‘That’s very good with mice. But let’s see if you can do it with a

human,”’ Dr. Zon recalled.

But others set off in what became an international race to repeat the work with

human cells.

“Dozens, if not hundreds of labs, have been attempting to do this,” said Dr.

George Daley, associate director of the stem cell program at Children’s

Hospital.

Few expected Dr. Yamanka would succeed so soon. Nor did they expect that the

same four genes would reprogram human cells.

“This shows it’s not an esoteric thing that happened in the mouse,” said Rudolf

Jaenisch, a stem cell researcher at M.I.T.

Ever since the birth of Dolly the sheep, scientists knew that adult cells could,

in theory, turn into embryonic stem cells. But they had no idea how to do it

without cloning, the way Dolly was created.

With cloning, researchers put an adult cell’s chromosomes into an unfertilized

egg whose genetic material was removed. The egg, by some mysterious process,

then does all the work. It reprograms the adult cell’s chromosomes, bringing

them back to the state they were in just after the egg was fertilized. Those

reprogrammed genes then direct the development of an embryo. A few days later, a

ball of stem cells emerges in the embryo. Since the embryo’s chromosomes came

from the adult cell, every cell of the embryo, including its stem cells, are

exact genetic matches of the adult.

The abiding question, though, was, How did the egg reprogram the adult cell’s

chromosomes? Would it be possible to reprogram an adult cell without using an

egg?

About four years ago, Dr. Yamanaka and Dr. Thomson independently hit upon the

same idea. They would search for genes that are being used in an embryonic stem

cell that are not being used in an adult cell. Then they would see if those

genes would reprogram an adult cell.

Dr. Yamanaka worked with mouse cells and Dr. Thomson worked with human cells

from foreskins.

The researchers found more than 1,000 candidate genes. So both groups took

educated guesses, trying to whittle down the genes to the few dozen they thought

might be the crucial ones and then asking whether any combinations of those

genes could turn a skin cell into a stem cell.

It was laborious work, with no guarantee of a payoff.

“The number of factors could have been one or ten or 100 or more,” Dr. Yamanaka

said in a telephone interview from his lab in Japan.

If many genes were required, the experiments would have failed, Dr. Thomson

said, because it would be impossible to test all the gene combinations.

The mouse work went more quickly than Dr. Thomson’s work with human cells. As

soon as Dr. Yamanaka saw that the mouse experiments succeeded, he began trying

the same brute force method in human skin cells that he ordered from a

commercial laboratory. Some were face cells from a 36 year old white woman and

others were connective tissue cells from joints of a 69 year old white man.

Dr. Yamanaka said he thought it would take a few years to find the right genes

and the right conditions to make the human experiments work. Feeling the hot

breath of competitors on his neck, he was in his lab every day for 12 to 14

hours a day, he said.

A few months later, he succeeded.

“We did work very hard,” Dr. Yamanaka said. “But we were very surprised.”

New Stem Cell Method Could Ease Ethical Concerns, NYT,

21.11.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/21/science/21stem.html?hp

Stem

Cell Breakthrough Reported

November

20, 2007

Filed at 9:59 a.m. ET

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

The New York Times

NEW YORK

(AP) -- Scientists have made ordinary human skin cells take on the

chameleon-like powers of embryonic stem cells, a startling breakthrough that