|

History > 2008 > USA > Internet, media (I)

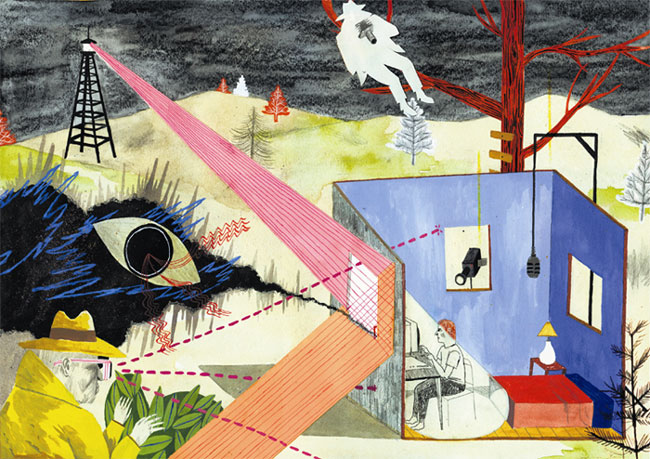

Illustration:

Drew Beckmeyer

The Undercover Parent

NYT

16.3.2008

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/16/opinion/16coben.html?ref=opinion

Wikipedia Questions Paths to More Money

March 21,

2008

Filed at 5:22 a.m. ET

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

The New York Times

Scroll the

list of the 10 most popular Web sites in the U.S., and you'll encounter the

Internet's richest corporate players -- names like Yahoo, Amazon.com, News

Corp., Microsoft and Google.

Except for No. 7: Wikipedia. And there lies a delicate situation.

With 2 million articles in English alone, the Internet encyclopedia ''anyone can

edit'' stormed the Web's top ranks through the work of unpaid volunteers and the

assistance of donors. But that gives Wikipedia far less financial clout than its

Web peers, and doing almost anything to improve that situation invites scrutiny

from the same community that proudly generates the content.

And so, much as how its base of editors and bureaucrats endlessly debate touchy

articles and other changes to the site, Wikipedia's community churns with

questions over how the nonprofit Wikimedia Foundation, which oversees the

project, should get and spend its money.

Should it proceed on its present course, soliciting donations largely to keep

its servers running? Or should it expand other sources of revenue -- with ads,

perhaps, or something like a Wikipedia game show -- to fulfill grand visions of

sending DVDs or printed books to people who lack computers? Is it helpful -- or

counter to the project's charitable, free-information mission -- to have the

Wikimedia Foundation tight with a prominent venture capital firm?

These would be tough questions for any organization, let alone one in which

hundreds of participants can expect to have a say.

The system ''has strengths and weaknesses,'' says Jimmy Wales, Wikipedia's

co-founder and ''chairman emeritus.'' ''The strength is, we don't do anything

randomly, without lots and lots of lots of discussion. The downside is we don't

get anything done unless we actually come to a conclusion.''

Even the foundation's leaders aren't unified. Florence Devouard, a French plant

scientist who chairs the board, said she and other Europeans involved with the

project are more skeptical than Americans such as Wales about moneymaking side

projects with for-profit entities.

The project's financial situation is not exactly dire. Although the group does

not have an endowment fund with interest fueling operations, cash contributions

jumped to $2.2 million last year, from $1.3 million in the prior year. With big

gifts recently, the foundation's budget is $4.6 million this year.

In the past year, the foundation has tried to become less of an ad hoc outfit,

expanding staff from less than 10 people to roughly 15 and moving to San

Francisco from St. Petersburg, Fla. It has a new executive director, Sue

Gardner, formerly head of the Canadian Broadcasting Corp.'s Web operations, who

expects to add professional fund-raisers and improve ties with Wikimedia

patrons.

''Two years ago, if you donated $10,000, you might not even get a phone call or

a thank-you letter,'' Wales said. ''That's just not acceptable.''

Gardner appears to favor an incremental strategy, stretching the staff to 25

people by 2010, with the budget increasing toward $6 million. Even such

relatively simple changes, she said, would keep the foundation from missing out

on business partnerships and other opportunities.

For example, project leaders would like to hold ''Wikipedia Academies'' in

developing countries, to encourage new cadres of contributors in other

languages. Wales also wants to implement software that makes it less technically

daunting for newcomers to edit Wikipedia articles -- an idea that has been

discussed for at least two years.

It might seem surprising that such a low-key agenda could prove contentious,

given that Wikimedia and Wales have also encountered complaints of being

incautious with donors' money. But some Wikipedians want the foundation to be

spending more.

''Why should they have to be wise spending such a little amount of money when

they could have so much more?'' said Nathan Awrich, a Wikipedia contributor from

Vermont who advocates limited ads on the site, to help pay for technical

improvements, better outreach and even a legal-defense fund. ''This is not a

foundation that needs to last one more year. This is a foundation that needs to

be planning for a longer term, and it doesn't seem like they're doing it.''

Gardner said she opposes advertising unless it came down to a choice between

''shutting down the servers and putting ads on the site. I don't think we're

ever going to get to that point, so I don't see advertising as an issue.''

Wales sounds political on the matter. On one hand, he said he believes

''advertising is really a nonstarter'' because of the potential harm to

Wikipedia's noncommercial image. However, he also said the subject requires more

research, so Wikipedians truly understand how much money the project is leaving

on the table by rejecting ads.

''I think it's a fallacy to say learning about something implies you want to do

it,'' he said. ''I would like to learn about it because I suspect it's not worth

it.''

Another subject getting carefully parsed is the foundation's relationship with

Elevation Partners, the venture firm co-founded by Roger McNamee and U2's Bono.

Elevation owns stakes in Forbes magazine and Palm Inc., among other companies.

McNamee has donated at least $300,000 to the Foundation, according to Danny

Wool, a former Wikimedia employee who processed the transactions. More recently,

the foundation said, McNamee introduced the group to people who made separate

$500,000 gifts. Their identities have not been disclosed.

Officially, Gardner and McNamee say he is a merely a fan of Wikimedia's

free-information project, separate from Elevation's profit-making interests.

''He has been clear -- when he talks to me, he's talking as a private

individual,'' Gardner said.

Yet the relationship runs deeper than that would suggest.

Another Elevation partner, Marc Bodnick, has met with Wales multiple times and

went to a 2007 Wikimedia board meeting in the Netherlands. (Wales described that

as a ''get to know you session'' and said Elevation, among many other venture

firms, quickly learned that the foundation was not interested in changing its

core, nonprofit mission.)

Bodnick and Bono had also been with Wales in 2006 in Mexico City, where U2 was

touring. On a hotel rooftop, Bono suggested that Wikipedia use its

volunteer-written articles as a starting point, then augment that with

professionals who would polish and publish the content, according to two people

who were present. Bono compared it to Bob Dylan going electric -- a jarring move

that people came to love.

McNamee and Bodnick declined to comment.

Although Wales says no business with Elevation is planned, that hasn't quelled

that element ever-present in Wikipedia: questions.

In the recent interview, Devouard, the board chair, said she believed Elevation

was interested in being more than just friends, though she wasn't sure just what

the firm hoped to get out of the nonprofit project.

''It is easy to see which interest WE have in getting their interest,'' she

wrote to Wales that day on an internal board mailing list, in an exchange

obtained by The Associated Press. ''The contrary is not obvious at all: Can you

explain to me why EP (Elevation Partners) are interested in us?''

------

On the Net:

http://www.wikimedia.org

Wikipedia Questions Paths to More Money, NYT, 21.3.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/technology/AP-Wikipedia-Finances.html

Op-Ed Contributor

The Undercover Parent

March 16, 2008

By HARLAN COBEN

Ridgewood, N.J.

NOT long ago, friends of mine confessed over dinner that they

had put spyware on their 15-year-old son’s computer so they could monitor all he

did online. At first I was repelled at this invasion of privacy. Now, after

doing a fair amount of research, I get it.

Make no mistake: If you put spyware on your computer, you have the ability to

log every keystroke your child makes and thus a good portion of his or her

private world. That’s what spyware is — at least the parental monitoring kind.

You don’t have to be an expert to put it on your computer. You just download the

software from a vendor and you will receive reports — weekly, daily, whatever —

showing you everything your child is doing on the machine.

Scary. But a good idea. Most parents won’t even consider it.

Maybe it’s the word: spyware. It brings up associations of Dick Cheney sitting

in a dark room, rubbing his hands together and reading your most private

thoughts. But this isn’t the government we are talking about — this is your

family. It’s a mistake to confuse the two. Loving parents are doing the

surveillance here, not faceless bureaucrats. And most parents already monitor

their children, watching over their home environment, their school.

Today’s overprotective parents fight their kids’ battles on the playground,

berate coaches about playing time and fill out college applications — yet when

it comes to chatting with pedophiles or watching beheadings or gambling away

their entire life savings, then...then their children deserve independence?

Some will say that you should simply trust your child, that if he is old enough

to go on the Internet he is old enough to know the dangers. Trust is one thing,

but surrendering parental responsibility to a machine that allows the entire

world access to your home borders on negligence.

Some will say that it’s better just to use parental blocks that deny access to

risky sites. I have found that they don’t work. Children know how to get around

them. But more than that — and this is where it gets tough — I want to know

what’s being said in e-mail and instant messages and in chat rooms.

There are two reasons for this. First, we’ve all read about the young boy

unknowingly conversing with a pedophile or the girl who was cyberbullied to the

point where she committed suicide. Would a watchful eye have helped? We rely in

the real world on teachers and parents to guard against bullies — do we just

dismiss bullying on the Internet and all it entails because we are entering

difficult ethical ground?

Second, everything your child types can already be seen by the world — teachers,

potential employers, friends, neighbors, future dates. Shouldn’t he learn now

that the Internet is not a haven of privacy?

One of the most popular arguments against spyware is the claim that you are

reading your teenager’s every thought, that in today’s world, a computer is the

little key-locked diary of the past. But posting thoughts on the Internet isn’t

the same thing as hiding them under your mattress. Maybe you should buy your

children one of those little key-locked diaries so that they too can understand

the difference.

Am I suggesting eavesdropping on every conversation? No. With new technology

comes new responsibility. That works both ways. There is a fine line between

being responsibly protective and irresponsibly nosy. You shouldn’t monitor to

find out if your daughter’s friend has a crush on Kevin next door or that Mrs.

Peterson gives too much homework or what schoolmate snubbed your son. You are

there to start conversations and to be a safety net. To borrow from the national

intelligence lexicon — and yes, that’s uncomfortable — you’re listening for

dangerous chatter.

Will your teenagers find other ways of communicating to their friends when they

realize you may be watching? Yes. But text messages and cellphones don’t offer

the anonymity and danger of the Internet. They are usually one-on-one with

someone you know. It is far easier for a predator to troll chat rooms and

MySpace and Facebook.

There will be tough calls. If your 16-year-old son, for example, is visiting

hardcore pornography sites, what do you do? When I was 16, we looked at Playboy

centerfolds and read Penthouse Forum. You may argue that’s not the same thing,

that Internet pornography makes that stuff seem about as harmful as “SpongeBob.”

And you’re probably right. But in my day, that’s all you could get. If something

more graphic had been out there, we probably would have gone for it. Interest in

those, um, topics is natural. So start a dialogue based on that knowledge. You

should have that talk anyway, but now you can have it with some kind of context.

Parenting has never been for the faint of heart. One friend of mine, using

spyware to monitor his college-bound, straight-A daughter, found out that not

only was she using drugs but she was sleeping with her dealer. He wisely took a

deep breath before confronting her. Then he decided to come clean, to let her

know how he had found out, to speak with her about the dangers inherent in her

behavior. He’d had these conversations before, of course, but this time he had

context. She listened. There was no anger. Things seem better now.

Our knee-jerk reaction as freedom-loving Americans is to be suspicious of

anything that hints at invasion of privacy. That’s a good and noble thing. But

it’s not an absolute, particularly in the face of the new and evolving

challenges presented by the Internet. And particularly when it comes to our

children.

Do you tell your children that the spyware is on the computer? I side with yes,

but it might be enough to show them this article, have a discussion about your

concerns and let them know the possibility is there.

Harlan Coben is the author of the forthcoming novel “Hold Tight.”

The Undercover

Parent, NYT, 16.3.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/16/opinion/16coben.html?ref=opinion

To Aim

Ads, Web Is Keeping Closer Eye on You

March 10,

2008

The New York Times

By LOUISE STORY

A famous

New Yorker cartoon from 1993 showed two dogs at a computer, with one saying to

the other, “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.”

That may no longer be true.

A new analysis of online consumer data shows that large Web companies are

learning more about people than ever from what they search for and do on the

Internet, gathering clues about the tastes and preferences of a typical user

several hundred times a month.

These companies use that information to predict what content and advertisements

people most likely want to see. They can charge steep prices for carefully

tailored ads because of their high response rates.

The analysis, conducted for The New York Times by the research firm comScore,

provides what advertising executives say is the first broad estimate of the

amount of consumer data that is transmitted to Internet companies.

Privacy advocates have previously sounded alarms about the practices of Internet

companies and provided vague estimates about the volume of data they collect,

but they did not give comprehensive figures.

The Web companies are, in effect, taking the trail of crumbs people leave behind

as they move around the Internet, and then analyzing them to anticipate people’s

next steps. So anybody who searches for information on such disparate topics as

iron supplements, airlines, hotels and soft drinks may see ads for those

products and services later on.

Consumers have not complained to any great extent about data collection online.

But privacy experts say that is because the collection is invisible to them.

Unlike Facebook’s Beacon program, which stirred controversy last year when it

broadcast its members’ purchases to their online friends, most companies do not

flash a notice on the screen when they collect data about visitors to their

sites.

“When you start to get into the details, it’s scarier than you might suspect,”

said Marc Rotenberg, executive director of the Electronic Privacy Information

Center, a privacy rights group. “We’re recording preferences, hopes, worries and

fears.”

But executives from the largest Web companies say that privacy fears are

misplaced, and that they have policies in place to protect consumers’ names and

other personal information from advertisers. Moreover, they say, the data is a

boon to consumers, because it makes the ads they see more relevant.

These companies often connect consumer data to unique codes identifying their

computers, rather than their names.

“What is targeting in the long term?” said Michael Galgon, Microsoft’s chief

advertising strategist. “You’re getting content about things and messaging about

things that are spot-on to who you are.”

The rich troves of data at the fingertips of the biggest Internet companies are

also creating a new kind of digital divide within the industry. Traditional

media companies, which collect far less data about visitors to their sites, are

increasingly at a disadvantage when they compete for ad dollars.

The major television networks and magazine and newspaper companies “aren’t even

in the same league,” said Linda Abraham, an executive vice president at

comScore. “They can’t really play in this sandbox.”

During the Internet’s short life, most people have used a yardstick from

traditional media to measure success: audience size. Like magazines and

newspapers, Web sites are most often ranked based on how many people visit them

and how long they are there.

But on the Internet, advertisers are increasingly choosing where to place their

ads based on how much sites know about Web surfers. ComScore’s analysis is a

novel attempt to estimate how many times major Web companies can collect data

about their users in a given month.

Web companies once could monitor the actions of consumers only on their own

sites. But over the last couple of years, the Internet giants have spread their

reach by acting as intermediaries that place ads on thousands of Web sites, and

now can follow people’s activities on far more sites.

Large Web companies like Microsoft and Yahoo have also acquired a number of

companies in the last year that have rich consumer data.

“So many of the deals are really about data,” said David Verklin, chief

executive of Carat Americas, an ad agency in the Aegis Group that decides where

to place ads for clients.

“Everyone feels that if we can get more data, we could put ads in front of

people who are interested in them,” he said. “That’s the whole idea here: put

dog food ads in front of people who have dogs.”

Web companies also can collect more data as people spend more time online. The

number of searches that American Web users enter each month has nearly doubled

since summer of 2006, to 14.6 billion searches in January, according to

comScore.

ComScore analyzed 15 major media companies’ potential to collect online data in

December. The analysis captured how many searches, display ads, videos and page

views occurred on those sites and estimated the number of ads shown in their ad

networks.

These actions represented “data transmission events” — times when consumer data

was zapped back to the Web companies’ servers. Five large Web operations —

Yahoo, Google, Microsoft, AOL and MySpace — record at least 336 billion

transmission events in a month, not counting their ad networks.

The methodology was worked out with comScore and based on the advice of senior

online advertising executives at two of the largest Internet companies.

“I think it’s a reasonable way to look at how many touch-points companies have

with their consumers,” Jules Polonetsky, the chief privacy officer for AOL, said

of the comScore findings on Friday.

But Mr. Polonetsky cautions that not all of the data at every company is used

together. Much of it is stored separately.

The information transmitted might include the person’s ZIP code, a search for

anything from vacation information to celebrity gossip, or a purchase of

prescription drugs or other intimate items. Some types of data, like search

queries, tends to be more valuable than others.

Yahoo came out with the most data collection points in a month on its own sites

— about 110 billion collections, or 811 for the average user. In addition, Yahoo

has about 1,700 other opportunities to collect data about the average person on

partner sites like eBay, where Yahoo sells the ads.

MySpace, which is owned by the News Corporation, and AOL, a unit of Time Warner,

were not far behind.

ComScore said it recorded the ad networks using different methods and that the

exact ordering of these top companies might vary with a different methodology,

but the overall picture would be similar.

Google also has scores of data collection events, but the company says it is

unique in that it mostly uses only current information rather than past actions

to select ads.

The depth of Yahoo’s database goes far in explaining why AOL is talking with

Yahoo about a merger and Microsoft is willing to pay more than $41.2 billion to

acquire the company.

Traditional media companies come in far behind.

Condé Nast magazine sites, for example, have only 34 data collection events for

the average site visitor each month. The numbers for other traditional media

companies, as generated by comScore, were 45 for The New York Times Company; 49

for another newspaper company, the McClatchy Corporation; and 64 for the Walt

Disney Company.

Some companies are trying to close the gap. Walt Disney, for example, is

studying how to combine data from its divisions like ESPN, Disney and ABC. The

News Corporation is exploring ways to use information that MySpace members post

on that site to select ads for those members when they visit other News

Corporation sites.

IAC is using data from its LendingTree site to deliver ads on its other sites to

people it knows are looking for mortgages.

Some advertising executives say media companies will have little choice but to

outsource their ad sales to companies like Microsoft and Yahoo to benefit from

their data. The Web companies may prove they can use their algorithms and

consumer information to better select which ads for visitors better than media

companies can.

“I think a lot of publishers are going to find they don’t have enough data,”

said David W. Kenny, chief executive of Digitas, a digital advertising agency in

the Publicis Groupe. “There’s only going to be a handful of big players who can

manage the data.”

People who spend more time on the Internet, of course, will have more

information transmitted about them. The comScore per-person figures are

averages; occasional Web users have far less transmitted about them.

The comScore figures do not include the data that consumers offer voluntarily

when registering for sites or e-mail services. When consumers do so, they often

give sites permission to link some of their interests or searches to their user

name.

The figures also do not account for information people enter on social network

pages. MySpace, for example, collects billions of user actions each day in the

form of blogs, comments and profile updates, said Peter Levinsohn, president of

Fox Interactive Media, which owns MySpace.

Even with all the data Web companies have, they are finding ways to obtain more.

The giant Internet portals have been buying ad-delivery companies like

DoubleClick and Atlas, which have stockpiles of information. Atlas, for example,

delivers 6 billion ads every day. The comScore figures do not capture such data.

Executives from Web companies said they had been working to inform consumers on

their data practices.

These companies noted their consumer-protection policies. AOL, for example, lets

users opt out of some ad targeting, Google lets users edit the search histories

that are linked to their user names, Yahoo is working on a policy to obscure

people’s computer identification addresses that are connected to search results,

and Microsoft says it does not link any of its visitors’ behavior to their user

names, even if those people are registered.

A study of California adults last year found that 85 percent thought sites

should not be allowed to track their behavior around the Web to show them ads,

according to the Samuelson Law, Technology & Public Policy Clinic at the

University of California at Berkeley, which conducted the study.

To Aim Ads, Web Is Keeping Closer Eye on You, NYT,

10.3.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/10/technology/10privacy.html?hp

Four

Charged With Running Online Prostitution Ring

March 7,

2008

The New York Times

By ALAN FEUER

Federal

authorities arrested four people Thursday on charges of running an online

prostitution ring that serviced clients in New York, Paris and other cities and

took in more than $1 million in profits over four years.

The ring, known as the Emperor’s Club V.I.P., had 50 prostitutes available for

appointments in New York, Washington, Miami, London and Paris, according to a

complaint unsealed on Thursday in Federal District Court in Manhattan. The

appointments, made by telephone or through on an online booking service, cost

$1,000 to $5,500 an hour and could be paid for with cash, credit card, wire

transfers or money orders, the complaint said.

According to the office of the United States attorney in Manhattan, Mark Brener,

62, of New Jersey, was the leader of the ring, but delegated day-to-day business

responsibilities to Cecil Suwal, 23, also of New Jersey. The office said that

Ms. Suwal controlled the bank accounts, took applications from prospective

prostitutes and oversaw two booking agents, identified by the authorities as

Temeka Rachelle Lewis, 32, of Brooklyn, and Tanya Hollander, 36, of Rhinebeck,

N.Y.

Ms. Hollander’s lawyer, Mary E. Mulligan, said her client was innocent, and that

“up until today, she lived a very quiet life in a small town.”

The ring’s Web site showed pictures of the prostitutes, cropped so faces were

not visible, and listed names like Sienna and Christine. The Web site, which was

disabled shortly after the arrests were announced, ranked the prostitutes on a

scale of one to seven “diamonds.” A three-diamond woman, for example, could

command a fee of $1,000 per hour. A seven-diamond woman cost more than $3,000 an

hour.

For its most valued clients, the Emperor’s Club offered membership in the elite

“Icon Club,” with hourly fees starting at $5,500, according to the federal

complaint. The club also offered clients the opportunity to purchase direct

access to a prostitute without having to contact the agency.

As part of the investigation, federal agents worked with a woman who claimed to

have worked for the Emperor’s Club as a prostitute in 2006, according to court

papers. An undercover agent posed as a potential client and arranged

appointments by phone and online.

After obtaining authorization to tap the club’s phones, federal agents recorded

more than 5,000 calls and text messages and had access to 6,000 e-mail messages,

court papers said. Many of these were somewhat mundane requests for

appointments. The authorities — the case was investigated by the Internal

Revenue Service and the F.B.I. — did not identify any of the clients.

Ms. Lewis and Ms. Hollander were charged with a conspiracy to violate federal

prostitution laws. Each faces up to five years in prison if convicted.

Mr. Brener and Ms. Suwal were accused of prostitution and money laundering: The

complaint says they funneled profits through bank accounts in the names of two

front companies, identified as QAT Consulting Group and QAT International. They

face maximum penalties of 25 years in prison if convicted.

Four Charged With Running Online Prostitution Ring, NYT,

7.3.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/07/nyregion/07prostitution.html

The Very

Model of a Modern Media Mogul

March 3,

2008

The New York Times

By BROOKS BARNES

LOS ANGELES

— When Michael D. Eisner left the Walt Disney Company in 2005 and set about

remaking himself in new media, investing in a video-sharing Web site and

starting a digital studio, some people in Hollywood snickered. Here we go, the

whispers went, another fading star who doesn’t know when to leave the stage.

Could Mr. Eisner get the last laugh?

Among the Hollywood developers scrambling to create original Internet programs,

Mr. Eisner, 65, is one of the very few who can claim early success. “Prom

Queen,” a murder-mystery series distributed on MySpace and other Web sites, has

been viewed by nearly 20 million people since its debut last spring.

He sold a dubbed version in France, peddled remake rights in Japan and made a

sequel, “Prom Queen: Summer Heat.” The series, which came with commercials, even

turned a profit along the way, a spokesman said.

Now, Mr. Eisner’s second series, “The All-For-Nots,” a comedy that documents the

travails of a fictional indie rock band, will make its debut next week on the

Internet, mobile devices and the HDNet cable network. The project reflects

lessons learned. This time Mr. Eisner is protecting broad foreign syndication

sales by restricting foreign access to the series, which will be available in

the United States on YouTube and other sites.

With “The All-For-Nots,” which is sponsored by Chrysler and Expedia, Mr. Eisner

is out to prove there is money to be made in the space between user-generated

content and traditional television production.

“I would like to say I have a McKinsey study of a strategy,” he said, referring

to the management consulting firm. “It doesn’t work that way. You just take your

history and your education and your instincts and you put them all into a

melting pot and out comes something.”

There are plenty of people in Hollywood who are rooting for him to fail.

Jealousy over the success of “Prom Queen” — and Mr. Eisner’s occasional boasting

about it — is one reason. He also retains his share of detractors from the

Disney days. And while Internet types have overwhelmingly welcomed him, others

remain skeptical.

“Just because Eisner is behind something, it doesn’t mean it is going to be a

success,” said Darren Aftahi, a digital media analyst at ThinkEquity Partners in

Minneapolis.

Still, the manner in which Mr. Eisner signed up Chrysler goes a long way toward

explaining how he has become a leader of the digital media pack.

Most of his rivals — including his former employer, which announced the creation

of a digital production studio last week — must labor to woo big-name

advertisers to their untested Web content. The Disney-ABC Television Group spent

months refining its strategy before Toyota signed on as the inaugural sponsor.

Mr. Eisner just flips through his Rolodex. When you spend 21 years running

Disney, your friends are people like Robert L. Nardelli, the chairman of

Chrysler. “I needed a car for the show so I called Bob,” Mr. Eisner said. (His

successor at Disney and the other media kingpins have deep business

relationships of their own, of course, but do not have the luxury of devoting

their full attention to lining up product placements.)

Vuguru, Mr. Eisner’s Web studio, is just one of dozens of players trying to make

a business out of Web shows. Many have popped up in recent months, as producers

idled by the writers’ strike tested the medium. Others, like the producers of

“Lonelygirl15,” have been tinkering in the area for years.

Studios like Warner Brothers and NBC Universal also have been trying to muscle

in to the area. There have been pockets of success, but no studio has proved

that it has a workable business model, said Michael Pond, a media analyst at

Nielsen Online.

“The big studios have a lot of resources, but fast for them is pretty slow for

the Web,” he said. “They are focusing harder on creating Web programs, but

others are already there.”

Like Mr. Eisner. Vuguru, a made-up word he thought sounded hip, is part of a

constellation of new-media plays he is making. Through Tornante, the venture

capital firm he founded after leaving Disney, Mr. Eisner owns Vuguru; a large

stake in Veoh, a site that allows users to download video with the quality of

high-definition television; and Team Baby Entertainment, which makes

sports-themed DVDs for infants and toddlers.

Most recently, Tornante, which is Italian for “hairpin turn,” paid $385 million

for Topps, the longtime maker of trading cards and Bazooka bubble gum.

Mr. Eisner is keeping his ultimate playbook to himself, but drops a few hints.

“With Topps, I was interested in a company that could be a far bigger sports and

entertainment media company,” he said. Among his ideas are the digital delivery

of trading cards and the creation of Topps-branded sports movies or sports

channels on cable. As for Bazooka Joe, the gum mascot, he recently told a trade

magazine that “it would be foolish of me not to try and build that character

into something as much as or more than he ever was.”

In some ways, “The All-For-Nots” is comfortable territory for Mr. Eisner. While

working at ABC in 1970, he helped develop “The Partridge Family,” the series

about a musical family that unexpectedly hits it big. “The new show is not that

different from that experience of marrying music to story,” he said.

The idea for “The All-For-Nots” came last spring when Mr. Eisner saw “The Burg,”

a Web comedy about the Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn. “It had real

flair,” he said. “It was funny.” He sought out the creator, a company called

Dinosaur Diorama, and asked for ideas.

He passed on “The Burg 2,” but a pitch about the hubristic futility of trying to

conquer the nation with indie rock sounded fun.

Bebo, the large social networking site, signed on as a distribution partner,

along with a half-dozen other sites. “The All-For-Nots” cast members will have

Bebo profiles that link to a channel where users can watch the series. David

Aufhauser, Bebo’s business development director, noted that the site’s features

would allow users to distribute “All-For-Nots” content among themselves.

Verizon Wireless became the mobile video partner and Mr. Eisner got HDNet on

board. Mark Cuban, the founder of HDNet, had been a guest on Mr. Eisner’s CNBC

talk show. “Michael and I talk ideas all the time,” Mr. Cuban wrote in an e-mail

message. “The approach we have taken with ‘All-For-Nots’ gives us three shots at

consumers, any of which could take off singularly or in combination. Web

exclusivity is too limited.”

Like Chrysler, Expedia paid to be woven into the story line. As the band travels

to 24 cities in search of fame, it books hotel rooms using Expedia, the online

travel agency. Sarah Pynchon, Expedia’s vice president for brand marketing, said

the company has been looking for product-placement opportunities in Web shows,

but has been reluctant because the Internet audience “is going to be much more

skeptical” of advertiser integration than television viewers.

Mr. Pond of Nielsen said that Mr. Eisner was smart to focus on music-driven

stories, pointing to the success of shows like “Hannah Montana.” The concept

also provides additional marketing angles. Cast members of “The All-For-Nots”

will perform a concert on March 11 at the South by Southwest festival in Austin,

Tex.

Mr. Eisner is the first to caution that, despite his early success, he has not

found the Web video Rosetta Stone. Indeed, the slogan for “The All-For-Nots”

could be his own. “The band that will conquer the World Wide Web,” the show’s

Web site reads, “unless they run out of gas.”

The Very Model of a Modern Media Mogul, NYT, 3.3.3008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/03/business/media/03eisner.html

Adobe

Blurs Line Between PC and Web

February

25, 2008

The New York Times

By JOHN MARKOFF

SAN

FRANCISCO — On sabbatical in 2001 from Macromedia, Kevin Lynch, a software

developer, was frustrated that he could not get to his Web data when he was off

the Internet and annoyed that he could not get to his PC data when he was

traveling.

Why couldn’t he have access to all his information, like movie schedules and

word processing documents, in one place?

He hit upon an idea that he called “Kevincloud” and mocked up a quick

demonstration of the idea for executives at Macromedia, a software development

tools company. It took data stored on the Internet and used it interchangeably

with information on a PC’s hard drive. Kevincloud also blurred the line between

Internet and PC applications.

Seven years later, his brainchild is about to come into focus on millions of

PCs. On Monday, Mr. Lynch, who was recently named the chief technology officer

at Adobe Systems, which bought Macromedia in 2005, will release the official

version of AIR, a software development system that will power potentially tens

of thousands of applications that merge the Internet and the PC, as well as blur

the distinctions between PCs and new computing devices like smartphones.

Adobe sees AIR as a major advance that builds on its Flash multimedia software.

Flash is the engine behind Web animations, e-commerce sites and many streaming

videos. It is, the company says, the most ubiquitous software on earth, residing

on almost all Internet-connected personal computers.

But most people may never know AIR is there. Applications will look and run the

same whether the user is at his desk or his portable computer, and soon when

using a mobile device or at an Internet kiosk. Applications will increasingly be

built with routine access to all the Web’s information, and a user’s files will

be accessible whether at home or traveling.

AIR is intended to help software developers create applications that exist in

part on a user’s PC or smartphone and in part on servers reachable through the

Internet.

To computer users, the applications will look like any others on their device,

represented by an icon. The AIR applications can mimic the functions of a Web

browser but do not require a Web browser to run.

The first commercial release of AIR takes place on Monday, but dozens of

applications have been built around a test or beta version.

EBay offers an AIR-based application called eBay Desktop that gives its

customers the power to buy wherever they are. Adobe uses AIR for Buzzword, an

online word processing program. At Monday’s introduction event in San Francisco,

new hybrid applications from companies including Salesforce, FedEx, eBay,

Nickelodeon, Nasdaq, AOL and The New York Times Company will be demonstrated.

Like Adobe’s Flash software, AIR will be given away. The company makes its money

selling software development kits to programmers.

Mr. Lynch and a rapidly growing number of industry executives and technologists

believe that the model represents the future of computing.

Moreover, the move away from PC-based applications is likely to get a

significant jump start in the coming weeks when Intel introduces its low-cost

“Netbook” computer strategy, which is intended to unleash a new wave of

inexpensive wireless connected mobile computers.

The new machines will have a relatively small amount of solid state disk storage

capacity and will increasingly rely on data stored on Internet servers.

“There is a big cloud movement that is building an infrastructure that speaks

directly to this kind of software and experience,” said Sean M. Maloney, Intel’s

executive vice president.

Adobe faces stiff competition from a number of big and small companies with the

same idea. Many small developers like OpenLazlo and Xcerion are creating

“Web-top” or “Web operating systems” intended to move applications and data off

the PC desktop and into the Internet through the Web browser.

Mozilla, the developer of the Firefox Web browser, has created a system known as

Prism. Sun Microsystems introduced JavaFX this year, which is also aimed at

blurring the Web-desktop line. Google is testing a system called Gears, which is

intended to allow some Web services to work on computers that are not connected

to the Internet.

Finally, there is Microsoft. It is pushing its competitor to Flash, called

Silverlight. Three years ago, Microsoft hired one of Mr. Lynch’s crucial

software developers at Macromedia, Brad Becker, to help create it. Mr. Becker

was a leading designer of the Flash programming language.

The blurring of Web and desktop applications and PC and phone applications is

further encouraged by the cellphone industry’s race to catch up with Apple’s

iPhone. The industry is focusing on smartphones, or what Sanjay K. Jha, the

chief operating officer of Qualcomm, calls “pocketable computing.”

“We need to deliver an experience that is like the PC desktop,” he said. “At the

same time, people are used to the Internet and you can’t shortchange them.”

Much software will have to be rewritten for the new devices, in what Mr. Lynch

said is the most significant change for the software industry since the

introduction in the 1980s of software that can be run through clicking icons

rather than typing in codes. This upheaval pits the world’s largest software

developer groups against one another in a battle for the new hybrid software

applications. Industry analysts say there are now about 1.2 billion

Internet-connected personal computers. Market researchers peg the number of

smartphones sold in 2007 at 123 million, but that market is growing rapidly.

“There is a proliferation of platforms,” Mr. Lynch said. “This is a battle for

the hearts and minds of people who are building things.”

The battle will largely pit Microsoft’s 2.2 million .Net software developers

against the more than one million Adobe Flash developers, who have until now

developed principally for the Web, as well as a vast number of other

Web-oriented designers who use open-source software development tools that are

referred to as AJAX.

Microsoft executives said they thought the company would have an advantage

because Silverlight has a more sophisticated security model. “Desktop

integration is a mixed blessing. There is potentially a gaping security hole,”

said Microsoft’s Mr. Becker. “We’ve learned at the school of hard knocks about

security.”

Microsoft’s competitors challenge its intent and assert that its goal is

retaining its desktop monopoly. “Microsoft is taking their desktop franchise and

trying to move that franchise to the Web,” said John Lilly, chief executive of

Mozilla. He faults the design of Silverlight for being an island that is not

truly integrated with the Internet.

“You get this rectangle in a Web browser and it can’t interact with the rest of

the Web,” he said.

He said Mozilla’s Prism offers a simple alternative to capitalize on the

explosion of creative software development taking place on the Internet. “There

are jillions of applications. A million more got launched today. The whole world

is collaborating on this.”

Up to now, it has been a low-level war between Microsoft and Adobe. Silverlight,

for instance, got high marks from developers for its ability to handle high

resolution video, but Adobe quickly upgraded Flash last year in response.

“We said, ‘Let’s put this in right now,’ ” Mr. Lynch said. With revenue last

year of $3.16 billion, Adobe is large enough to fight Microsoft.

Adobe, the maker of Photoshop, Acrobat and other software, also has a strong

reputation as a maker of tools for the creative class. "We’re one of the best

tool makers in the world," said Mr. Lynch, who worked on software design at

MicroPro, the publishers of the Wordstar word processor, and at General Magic,

an ill-fated effort to create what could be called a predecessor to today’s

smartphones, before joining Macromedia.

“Adobe’s known for its designer tools, but they realize that development — for

the browser, for the desktop, and for devices such as cellphones — is a huge

growth market,” said Steve Weiss, executive editor at O’Reilly Media, a

technology publishing firm.

Adobe Blurs Line Between PC and Web, NYT, 25.2.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/02/25/technology/25adobe.html

Judge

Shuts Down Web Site Specializing in Leaks

February

20, 2008

The New York Times

By ADAM LIPTAK and BRAD STONE

In a move

that legal experts said could present a major test of First Amendment rights in

the Internet era, a federal judge in San Francisco on Friday ordered the

disabling of a Web site devoted to disclosing confidential information.

The site, Wikileaks.org, invites people to post leaked materials with the goal

of discouraging “unethical behavior” by corporations and governments. It has

posted documents said to show the rules of engagement for American troops in

Iraq, a military manual for the operation of the detention center at Guantánamo

Bay, Cuba, and other evidence of what it has called corporate waste and

wrongdoing.

The case in San Francisco was brought by a Cayman Islands bank, Julius Baer Bank

and Trust. In court papers, the bank said that “a disgruntled ex-employee who

has engaged in a harassment and terror campaign” provided stolen documents to

Wikileaks in violation of a confidentiality agreement and banking laws.

According to Wikileaks, “the documents allegedly reveal secret Julius Baer trust

structures used for asset hiding, money laundering and tax evasion.”

On Friday, Judge Jeffrey S. White of Federal District Court in San Francisco

granted a permanent injunction ordering Dynadot, the site’s domain name

registrar, to disable the Wikileaks.org domain name. The order had the effect of

locking the front door to the site — a largely ineffectual action that kept back

doors to the site, and several copies of it, available to sophisticated Web

users who knew where to look.

Domain registrars like Dynadot, Register.com and GoDaddy .com provide domain

names — the Web addresses users type into browsers — to Web site operators for a

monthly fee. Judge White ordered Dynadot to disable the Wikileaks.org address

and “lock” it to prevent the organization from transferring the name to another

registrar.

The feebleness of the action suggests that the bank, and the judge, did not

understand how the domain system works, or how quickly Web communities will move

to counter actions they see as hostile to free speech online.

The site itself could still be accessed at its Internet Protocol address

(http://88.80.13.160/) — the unique number that specifies a Web site’s location

on the Internet. Wikileaks also maintained “mirror sites,” or copies usually

produced to ensure against failures and this kind of legal action. Some sites

were registered in Belgium (http://wikileaks.be/), Germany (http://wikileaks.de)

and the Christmas Islands (http://wikileaks.cx) through domain registrars other

than Dynadot, and so were not affected by the injunction.

Fans of the site and its mission rushed to publicize those alternate addresses

this week. They have also distributed copies of the bank information on their

own sites and via peer-to-peer file sharing networks.

In a separate order, also issued on Friday, Judge White ordered Wikileaks to

stop distributing the bank documents. The second order, which the judge called

an amended temporary restraining order, did not refer to the permanent

injunction but may have been an effort to narrow it.

Lawyers for the bank and Dynadot did not respond to requests for comment. Judge

White has scheduled a hearing in the case for Feb. 29.

In a statement on its site, Wikileaks compared Judge White’s orders to ones

eventually overturned by the United States Supreme Court in the Pentagon Papers

case in 1971. In that case, the federal government sought to enjoin publication

by The New York Times and The Washington Post of a secret history of the Vietnam

War.

“The Wikileaks injunction is the equivalent of forcing The Times’s printers to

print blank pages and its power company to turn off press power,” the site said,

referring to the order that sought to disable the entire site.

The site said it was founded by dissidents in China and journalists,

mathematicians and computer specialists in the United States, Taiwan, Europe,

Australia and South Africa. Its goal, it said, is to develop “an uncensorable

Wikipedia for untraceable mass document leaking and analysis.”

Judge White’s order disabling the entire site “is clearly not constitutional,”

said David Ardia, the director of the Citizen Media Law Project at Harvard Law

School. “There is no justification under the First Amendment for shutting down

an entire Web site.”

The narrower order, forbidding the dissemination of the disputed documents, is a

more classic prior restraint on publication. Such orders are disfavored under

the First Amendment and almost never survive appellate scrutiny.

Judge Shuts Down Web Site Specializing in Leaks, NYT,

20.2.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/02/20/us/20wiki.html?hp

Facing

Free Software, Microsoft Looks to Yahoo

February 9,

2008

The New York Times

By MATT RICHTEL

SAN

FRANCISCO — Nearly a quarter-century ago, the mantra “information wants to be

free” heralded an era in which news, entertainment and personal communications

would flow at no charge over the Internet.

Now comes a new rallying cry: software wants to be free. Or, as the tech

insiders say, it wants to be “zero dollar.”

A growing number of consumers are paying just that — nothing. This is the

Internet’s latest phase: people using freely distributed applications, from

e-mail and word processing programs to spreadsheets, games and financial

management tools. They run on distant, massive and shared data centers, and

users of the services pay with their attention to ads, not cash.

While such services have been emerging for years, their rapid adoption has been

an important but largely overlooked driver of the $44.6 billion hostile bid that

Microsoft made to take over Yahoo this week.

That proposed deal would give Microsoft access to Yahoo’s vast news,

information, search and advertising network — and the ability to compete more

squarely with Google.

But a merger would also allow Microsoft to adapt its empire to compete in a

world of low-cost Internet-centered software.

Yahoo’s huge user base could provide the audience and the infrastructure for

Microsoft to change how it distributes its products and charges for them.

“Microsoft makes its money selling licenses to millions and millions of people

who install it on individual hard drives,” said Nicholas Carr, a former editor

at The Harvard Business Review and author of “The Big Switch,” a book about the

transition to what the technology industry calls cloud computing.

“Most of what you need is on the Internet — and it’s free,” he said. “There are

early warning signs that the traditional Microsoft programs are losing their

grip.”

Certainly, analysts said, Microsoft’s revenue — $51 billion last year, most of

it from software — is not yet suffering in any meaningful way.

The company said, to the contrary, that business is booming, and that Microsoft

Office, a flagship product, is having a record-breaking year.

“Last year was our best year, and this year is better,” said Chris Capossela, a

Microsoft vice president with the Office division.

At the same time, though, the company has lowered prices. Last year it began

selling its $120 student-teacher edition to mainstream consumers, who had been

asked to pay more than $300 for a similar product.

The bulk of the company’s profit comes from selling to corporations, which

unlike consumers may be slower to adapt to a system in which proprietary data is

not stored in corporate-owned data centers.

Microsoft said that corporate customers prefer using software that they are

familiar with and that provides more functions and better security.

But the corporate business, too, is coming under increasing assault from

lower-cost Internet competitors, including Microsoft’s archnemesis, Google.

On Thursday, Google took its attack to a new level. It released Google Apps Team

Edition — a version of its productivity software that includes word processing,

spreadsheet and calendar programs. In a form of guerrilla marketing, the fans of

Google Docs can take it into the office, bypassing or perhaps influencing

decisions made by corporate executives, who until now have overwhelmingly bought

Microsoft software.

Google, while it gives such software free to consumers, charges corporations for

a premium edition, though the fee is less than what Microsoft charges for

productivity software, analysts said.

The change is coming not from corporations but on the computers of a growing

base of individuals who increasingly expect their software to be free — and for

it to be processed and managed over the Internet.

Kevin Twohy, 20, a mathematics student at U.C.L.A., uses a free service on

Facebook to store and share photos, a program called Picnik to edit the images,

and Gmail.

For his English class last semester, he wrote a term paper about William Blake

using Google’s free word processing software, even though Microsoft Office had

come loaded on his personal computer.

The advantage of the Google program, he said, was that it allowed him to keep

his information on Google’s servers so that it was accessible at any computer,

whether he was working at his fraternity, a coffee shop, a campus computer bank

or the library. The experience, he said, has persuaded him not to pay money for

software.

“I don’t ever see myself buying a copy of Office,” he said.

Those individual users may be able to do what an army of lawyers and regulators

in the United States and Europe have never been able to do — rein in Microsoft’s

monopoly power. There is some evidence that the erosion in its pricing power has

already begun.

Last fall, Microsoft lowered prices of its most powerful productivity software

for students, whom it regards as important future customers. For a limited time,

it said, students could buy a $60 downloadable version of its most feature-rich

version of Office, which ordinarily costs around $460.

Microsoft has also had ad-supported online competitors who have challenged other

prominent brands, like the Encarta encyclopedia and Microsoft Money, personal

finance management software.

“If Microsoft had to start over today, it wouldn’t even think about charging

money for its software,” said Yun Kim, an industry analyst with Pacific Growth

Equities. “Nobody in their right mind is developing a business in the consumer

market to charge” for software.

Mr. Kim said that he expected Microsoft at some point to introduce a free

ad-supported version of Office for consumers, though the company insists that it

has no such intention.

Mr. Kim, however, expects that Microsoft’s corporate business is more entrenched

and resilient, and less susceptible to the influences of free or ad-supported

cloud computing.

Microsoft’s online competitors disagree. Among them is Zimbra, a division of

Yahoo that offers Internet-centered productivity software for e-mail, word

processing and spreadsheets.

Consumers pay nothing for the product, but corporations pay as much as $50 a

year per license. About 20,000 companies, most of them small, are paying

customers.

For Office software, Microsoft charges $75 a year per license to large

companies, and up to $300 for small companies, according to Forrester Research.

Satish Dharmaraj, general manager of Zimbra, said the company could undercut

Microsoft because it costs far less to create, maintain, fix and upgrade

software that runs in a central data center instead of on thousands of

individual computers.

But the relative quality of Microsoft’s software continues to attract customers,

argued J. P. Gownder, an industry analyst with Forrester Research.

He said that Microsoft has an opportunity to develop a hybrid version of its

software that combines the convenience of cloud computing with the security of

processing on the desktop, thus helping it maintain and further its empire.

“This is the predominant reason why Microsoft has gone after Yahoo,” Mr. Gownder

said. “The ad revenue is a nice short-term achievement, but in the long run it

is much more about delivering apps over the Web.”

Facing Free Software, Microsoft Looks to Yahoo, NYT,

9.2.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/02/09/technology/09free.html?ref=business

Google

Works to Torpedo Microsoft Bid for Yahoo

February 4,

2008

The New York Times

By ANDREW ROSS SORKIN and MIGUEL HELFT

Standing

between a marriage of Microsoft and Yahoo may be the technology behemoth that

has continually outsmarted them: Google.

In an unusually aggressive effort to prevent Microsoft from moving forward with

its $44.6 billion hostile bid for Yahoo, Google emerged over the weekend with

plans to play the role of spoiler.

Publicly, Google came out against the deal, contending in a statement that the

pairing, proposed by Microsoft on Friday in the form of a hostile offer, would

pose threats to competition that need to be examined by policy makers around the

world.

Privately, Google, seeing the potential deal as a direct attack, went much

further. Its chief executive, Eric E. Schmidt, placed a call to Yahoo’s chief,

Jerry Yang, offering the company’s help in fending off Microsoft, possibly in

the form of a partnership between the companies, people briefed on the call

said.

Google’s lobbyists in Washington have also begun plotting how it might present a

case against the transaction to lawmakers, people briefed on the company’s plans

said. Google could benefit by simply prolonging a regulatory review until after

the next president takes office.

In addition, several Google executives made “back-channel” calls over the

weekend to allies at companies like Time Warner, which owns AOL, to inquire

whether they planned to pursue a rival offer and how they could assist, these

people said. Google owns 5 percent of AOL.

Despite Google’s efforts and the work of Yahoo’s own bankers over the weekend to

garner interest in a bid to rival Microsoft’s, one did not seem likely, at least

at this early stage.

For example, a spokesman for the News Corporation said Sunday night that it was

not preparing a bid, and other frequently named prospective suitors like Time

Warner, AT&T and Comcast have not begun work on offers, people close to them

said. They suggested that they did not want to enter a bidding war with

Microsoft, which could easily top their offers.

A spokesman for Time Warner declined to comment, as did a spokesman for Comcast.

A representative for AT&T could not be reached.

In the meantime, people close to Yahoo said that the company received a flurry

of inquires over the weekend from potential suitors. Some people inside Yahoo

have even speculated about the prospect of breaking up the company. That could

mean selling or outsourcing its search-related business to Google and spinning

off or selling its operations that produce original content, these people said.

“Everyone is considering all kinds of options and a deal on search is one of

them,” a person familiar with the situation said.

One person involved in Yahoo’s deliberations suggested that “the sum of the

parts are worth more than the whole,” arguing that its various pieces like Yahoo

Finance, for example, could be sold to a company like the News Corporation for a

huge premium while Yahoo Sports could be sold to a company like ESPN, a unit of

the Walt Disney Company.

Executives at rival companies were less optimistic about such a breakup

strategy. “No one can get to a $44 billion price,” one executive at a major

media company said, “even if you split it into a dozen pieces.”

In making its bid for Yahoo, Microsoft is betting that past antitrust rulings

against it for abusing its monopoly power in personal computer software will not

restrain its hand in an Internet deal.

In the United States, a federal district court in Washington ruled in 2001 that

Microsoft had repeatedly violated the law by stifling the threat to its monopoly

position posed by Netscape, which popularized the Web browser. The suit, brought

during the Clinton administration, was settled by the Bush administration. But

as a result of a consent decree extending through 2009, a federal court and a

three-member team of technical experts monitors Microsoft’s behavior.

In 2006, for example, after Google complained to the Justice Department and the

European Commission that Microsoft was making its MSN search engine the default

in the most recent version of its Web browser, Microsoft modified the software

so that consumers could easily change to Google or Yahoo.

In Google’s statement on Sunday, it said that the potential purchase of Yahoo by

Microsoft could pose threats to competition that needed to be examined by policy

makers.

Google’s broadly worded concerns lacked detailed claims about any

anticompetitive effects of the deal, and the company did not publicly ask

regulators to take specific actions at this time.

“Could Microsoft now attempt to exert the same sort of inappropriate and illegal

influence over the Internet that it did with the PC?” asked David Drummond,

Google’s senior vice president and chief legal officer, writing on the company’s

blog.

Yahoo and Microsoft declined to comment Sunday on Google’s actions. Earlier on

Sunday, Microsoft’s general counsel, Bradford L. Smith, said in a statement:

“The combination of Microsoft and Yahoo will create a more competitive

marketplace by establishing a compelling No. 2 competitor for Internet search

and online advertising.”

Google’s effort to derail or delay the deal on antitrust grounds mirrors

Microsoft’s own actions with respect to Google’s bid for the online advertising

specialist DoubleClick for $3.1 billion, announced in April.

The strategy is not surprising, considering that any delays would work to

Google’s benefit. “Google can tap into all of the ill will that Microsoft has

created in the last couple of decades on the antitrust front,” said Eric

Goldman, director the High-Tech Law Institute at the Santa Clara University

School of Law.

The outcome of any antitrust inquiry will hinge, in part, on how regulators

define various markets. Microsoft-Yahoo, for instance, would have a large share

of the Web-based e-mail market, but a smaller share of the overall e-mail

market.

“The potential concern would be that Microsoft, if it acquires Yahoo, could do

on the Internet what it did in the personal computer world — make technical

standards more Microsoft-centric and steer consumers to its products,” said

Stephen D. Houck, a lawyer representing the states involved in the consent

decree against Microsoft.

Yahoo has not made a public statement about the proposed deal since Friday, when

it said it was weighing Microsoft’s offer as well as alternatives and would

“pursue the best course of action to maximize long-term value for shareholders.”

Carl W. Tobias, a law professor at the University of Richmond in Virginia, said

an antitrust review of the Microsoft-Yahoo deal could take a long time and “may

well bleed into a new administration with an entire new view on antitrust than

the Bush administration.”

Steve Lohr contributed reporting.

Google Works to Torpedo Microsoft Bid for Yahoo, NYT,

4.2.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/02/04/technology/04yahoo.html?hp

Talking

Business

A Giant

Bid That Shows How Tired the Giant Is

February 2,

2008

The New York Times

By JOE NOCERA

Oh, how the

mighty have fallen.

This may seem like an odd way to characterize a company that just announced its

willingness to plunk down $44.6 billion to make its first hostile takeover ever.

A company that will probably generate somewhere around $60 billion in revenue

when its fiscal year ends in June. A company whose market share in its two core

products is still so high — despite recent inroads by a certain flashy

competitor — that it qualifies as a monopoly.

But this is Microsoft we’re talking about, and if its proposed acquisition of

Yahoo signals anything, it serves as a confirmation that Microsoft’s glory days

are in the past. Having failed to challenge Google where it matters most — in

online advertising — it has been reduced to bulking up by buying Google’s

nearest but still distant competitor. In many ways, the company has become

exactly what Bill Gates used to fear the most — sluggish, bureaucratic, slow to

respond to new forms of competition — just as I.B.M. was when Microsoft

convinced that era’s tech behemoth to use Microsoft’s operating system in its

new personal computer.

The I.B.M. PC was introduced in the summer of 1981. Here we are nearly 27 years

later, and Microsoft’s core product is still its operating system, now called

Windows — that and its suite of applications, called Office, that run on

Windows. They generate billions of dollars annually for the company. The most

recent version of Windows, released almost exactly a year ago, has already been

installed in 100 million computers. Yet in technology, 27 years is a lifetime,

and there is a powerful sense that while it has spent enormous effort over the

years protecting its monopoly, the world has passed it by. In particular, the

technology world now centers on the Internet, where Google reigns supreme, and

Microsoft has never succeeded in making serious inroads. Years ago, it started

its own online service, MSN. It has made efforts to develop a search engine that

could compete with Google’s. It has developed an advertising infrastructure to

both place ads on other Web sites —another Google specialty—and to generate its

own ad revenues. In every case, it has come up a day late and a dollar short.

For instance, only 4 percent of Internet searches worldwide are done with

Microsoft’s engine, compared with over 65 percent done with Google’s.

“Of its five major divisions,” said Brent Thill, the software analyst for

Citigroup, “the online division is the only one that loses money. They are

software engineers at Microsoft,” he continued, “and their DNA is very different

from the DNA of someone who builds online assets. It’s just a different

mind-set.”

Besides, the old strategies that once worked so well for Microsoft — strategies

that worked when the world still revolved around Windows — have no place in this

new world. In the mid-1990s, when Netscape posed a threat to Microsoft’s

hegemony, Microsoft created its own competing browser, Internet Explorer, made

it an integral part of Windows, and used its desktop monopoly to fight back.

Eventually, Netscape was reduced to also-ran status — and the Justice Department

took Microsoft to court on antitrust violations.

Today, Microsoft lacks both the weaponry and the nimbleness to compete with

Google. Its operating system monopoly gives it no advantages in this battle.

People can use Microsoft’s operating system and browser to get to the Internet —

and to Google — or they can use Apple’s. It truly doesn’t matter. Meanwhile,

with every new Internet fad, like the current frenzy over social networking,

Microsoft is invariably caught flat-footed and has to race to just get a foot in

the game. But that’s always the way it is when companies get big — and it is why

real innovation always comes from small companies that don’t have a

predetermined mind-set, or monopoly profits to protect.

Will the purchase of Yahoo — assuming it goes through, which is far from a

foregone conclusion — be a game-changer for Microsoft? Anything is possible, I

suppose. I spoke to a number of technology experts Friday who were convinced

that it made some sense. Andy Kessler, the technology investor and writer,

called it “a smart offensive move.” Mark Anderson, the president of Strategic

News Service, said, “They are getting the No. 2 online guy in the ad business at

a good time and a good price.” Rob Enderle of the Enderle Group told me that it

was only a matter of time before somebody made a bid for Yahoo — “and it makes

sense that it’s Microsoft.”

But let’s be honest here. Microsoft isn’t exactly buying a high-flier. Even

after a Microsoft-Yahoo merger, Google would still have twice the search market

of its competitor. Its ad placement service is superior to either Microsoft’s or

Yahoo’s. And Yahoo has struggled enormously in the last few years. It, too,

could have been early in social networking; its chat rooms could have lent

themselves easily to something that might have rivaled Facebook. Just like

Microsoft, it missed the opportunity. It is quite clearly a company that has

lost its way, and the question of whether Microsoft can refocus into a viable

Google competitor, well, let’s just say I’m dubious.

I also have to wonder about what Yahoo gets out of the deal — other than a

premium for its depressed stock. “Does it help their brand?” asked Mark Mahaney,

who covers Yahoo for Citigroup. “No. Does it give them better search technology?

No. Does it give them a better ad sales force? No. I suspect this is the

question being asked in Yahoo’s boardroom right now,” he added.

What was most striking to me Friday was Microsoft’s own expectations for the

deal. To put it bluntly, they are awfully low. When I spoke to Yusuf Mehdi,

Microsoft’s senior vice president for strategic partnership — and the man who

had been driving much of its online efforts in recent years — he never once

talked about crushing the competition, or even catching up.

A Yahoo deal, he told me, “will be good for consumers who want another search

engine, Web publishers who want another ad placement service, and syndicated

advertisers” — who also want a choice other than Google. He continued: “Because

of Google’s heavy volume and its algorithms, they are a very efficient buy. But

people are rooting for a credible No. 2. We got lots of calls today from Web

sites and others saying, ‘We’re with you.’ ”

Was he really saying that Microsoft would be content as a “credible No. 2?” I

had a hard time believing it. But when I pushed him on this point, he reiterated

it. “Online advertising revenues are going to be $80 billion within a couple of

years,” he said. (They’re about $50 billion now.) “That is going to mean a

tremendous opportunity to all players. There has to be a place for another

credible player.”

I think back to the fall of 2005, when Bill Gates visited The New York Times,

and an editor asked him if Microsoft “would do to Google what you did to

Netscape?”

“Nah,” laughed Mr. Gates, “we’ll do something different.” This ain’t it.

A Giant Bid That Shows How Tired the Giant Is, NYT,

2.2.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/02/02/technology/02nocera.html

Microsoft Bids $44.6 Billion for Yahoo

February 1,

2008

The New York Times

By MIGUEL HELFT

SAN

FRANCISCO — In a bold move to counter Google’s online pre-eminence, Microsoft

said Friday that it had made an unsolicited offer to buy Yahoo for about $44.6

billion in a mix of cash and stock.

If consummated, the deal would redraw the competitive landscape in Internet

consumer services, where both Microsoft and Yahoo have both struggled to compete

with Google.

The offer of $31 a share represents a 62 percent premium over Yahoo’s closing

stock price of $19.18 on Thursday. It would be Microsoft’s largest acquisition

ever.

Microsoft said the combination of the two companies would create efficiencies

that would save approximately $1 billion annually. The software giant also said

that it has an integration plan to include employees of both companies and

intends to offer incentives to retain Yahoo employees.

Steven A. Ballmer, the Microsoft chief executive, said that he called his Yahoo

counterpart, Jerry Yang, on Thursday night to tell him that Microsoft intended

to bid on the company, and that they had a substantive discussion. “I wouldn’t

call it a courtesy call,” he said in an interview.

Mr. Ballmer said he had decided to pursue a takeover because friendly deal

negotiations would most likely be protracted and would probably become public.

“These things are hard to keep quiet in the best of times,” he said. He said his

conversation with Mr. Yang was constructive, but suggested that a deal may not

come easily.

Yahoo said in a news release Friday that its board would evaluate Microsoft’s

bid “carefully and promptly in the context of Yahoo’s strategic plans.”

In a letter to Yahoo’s board, Mr. Ballmer wrote that the two companies discussed

a possible merger, as well as other ways to work together, in late 2006 and

2007. Mr. Ballmer said that in February 2007, Yahoo decided to end the merger

discussions because its board was confident in the company’s “potential upside.”

“A year has gone by, and the competitive situation has not improved,” Mr.

Ballmer wrote.

As a result, he said, “while a commercial partnership may have made sense at one

time, Microsoft believes that the only alternative now is the combination of

Microsoft and Yahoo that we are proposing.”

Mr. Ballmer met several times in late 2006 and 2007 with Terry S. Semel, then

Yahoo’s chief executive, people involved in the talks said. While the talks —

originally focused on the prospect of a merger or a joint venture — were

initially constructive and appeared to move forward, they quickly broke down,

these people said.

After a series of secret meetings between both sides in hotels around California

and elsewhere, Mr. Semel and Yahoo’s board decided against progressing with the

talks, betting that its stock would turn around as it introduced a new

advertising system called Panama, these people said. Mr. Yang, in particular,

was adamantly against selling the company to Microsoft and championed the view

of remaining independent, they added.

Mr. Ballmer constantly consulted with Bill Gates, the Microsoft chairman, about

the progress of the negotiations, people close to the company said, and when the

talks collapsed, he decided to wait to see the fate of Yahoo’s stock price. As