|

History > 2008 > USA > Jail, Prison (II)

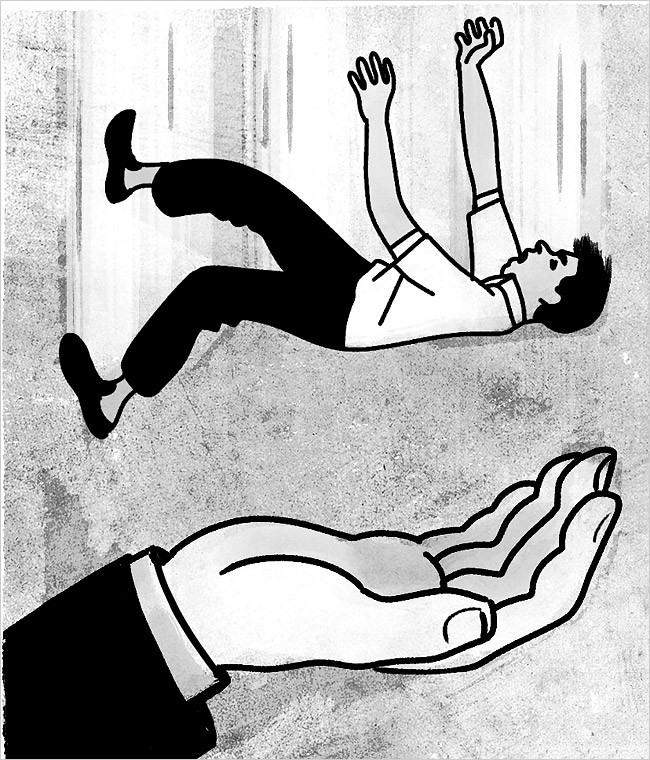

Illustration: Kyle T. Webster

Helping Prisoners Re-enter Society

NYT

27.5.2008

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/27/opinion/l27jails.html

Judges to Decide

Whether Crowded California Prisons

Are

Unconstitutional

December 8, 2008

The New York Times

By MALIA WOLLAN

SAN FRANCISCO — Faced with chronically packed prisons and a federal mandate

to improve medical and living conditions, a three-judge panel is meeting here to

decide whether the overcrowding results in unconstitutional treatment of

California’s more than 150,000 inmates. If so, the judges could order the state

to release tens of thousands of prisoners.

“We have a motion today to exercise a very serious order which interferes in a

profound way with the state’s right to run its own affairs,” one of the judges

on the panel, Lawrence Karlton of Federal District Court, said in a hearing last

week. “And on the other hand, we have a serious failure of the state to provide

adequate care.”

California’s 33 adult prisons teem with nearly double the inmates they were

designed to hold. Lawyers for the inmates say the conditions lead to violence,

outbreaks of disease, inadequate mental and other health care for prisoners, and

even death.

“Overcrowding is dangerous for the prisoners, for the corrections officers and

for the public,” said Michael Bien, a lawyer for the inmates, who asked the

judges to reduce the prison population by 52,000 inmates over two years.

Lawyers for the state argued that reducing the prison population would result in

increased crime and burden counties already facing tight budgets.

“Releasing more than 50,000 inmates onto the streets is dangerous,” said Matthew

Cate, secretary of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation,

who added that he had seen reports saying that California’s inmates tended to

have more felony offenses than inmates in other states.

“Our most serious problem is providing enough appropriate space for our

seriously mentally ill inmates,” Mr. Cate said, “and releasing prisoners is not

going to fix that problem.”

But lawyers for the inmates said that they were not seeking the release of

dangerous criminals and that much of the reduction in the number of inmates

could come from not sending people who have committed minor parole violations

back to prison.

The state’s prison health system is currently under the control of a federal

receiver, who announced in August that the state would need to spend $8 billion

to fix its prisons and build facilities.

But the state is also facing a severe budget crisis. Last Monday, Gov. Arnold

Schwarzenegger declared a financial emergency and requested the State

Legislature to address an $11.2 billion dollar deficit, saying that without

immediate action, “our state is headed for a fiscal disaster where everyone will

be hurt.”

Another judge at the hearing, Stephen Reinhardt of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, said, “We should start from the premise that

there’s not going to be any more money spent on this problem.”

The panel is expected to rule early next year, but an order to release prisoners

would most likely face an appeal to the United States Supreme Court.

Judges to Decide Whether

Crowded California Prisons Are Unconstitutional, NYT, 8.12.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/08/us/08calif.html

The California Prison Disaster

October 25, 2008

The New York Times

The mass imprisonment philosophy that has packed prisons and sent corrections

costs through the roof around the country has hit especially hard in California,

which has the largest prison population, the highest recidivism rate and a

prison budget raging out of control.

According to a new federally backed study conducted at the University of

California, Irvine, the state’s corrections costs have grown by about 50 percent

in less than a decade and now account for about 10 percent of state spending —

nearly the same amount as higher education. The costs could rise substantially

given that a federal lawsuit may require the state to spend $8 billion to bring

the prison system’s woefully inadequate medical services up to constitutional

standards.

The solution for California is to shrink its vastly overcrowded prison system.

To do so, it would need to move away from mandatory sentencing laws that have

proved to be disastrous across the country — locking up more people than

protecting public safety requires.

In addition, the state also has perhaps the most counterproductive and

ill-conceived parole system in the United States. More people are sent to prison

in California by parole officers than by the courts. In addition, about 66

percent of California’s parolees land back in prison after three years, compared

with about 40 percent nationally. Four in 10 are sent back for technical

violations like missed appointments or failed drug tests.

Later this year, the state is expected to begin testing a new system that

redirects the lowest-risk drug addicts to treatment. But that will only work if

the state and the counties dramatically expand treatment slots.

The heart of the problem is that California’s parole system is simply too big.

Most states keep dangerous people behind bars or reserve parole supervision for

the most serious offenders. California puts virtually everyone on parole,

typically for three years.

Under this setup, about 80 percent of the parolees have fewer than two 15-minute

meetings with a parole officer per month. That might be adequate for low-risk

offenders, but it’s clearly too little time for serious offenders who present a

risk to public safety.

A good first step would be to place fewer people on parole. The second step

would be to reserve the most intensive supervision for offenders who present the

greatest risk.

State lawmakers, some of whom are fearful of being seen as soft on crime, have

failed to make perfectly reasonable sentencing modifications and other changes

that the prisons desperately need. Unless they muster some courage soon,

Californians will find themselves swamped by prison costs and unable to afford

just about anything else.

The California Prison

Disaster, NYT, 25.10.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/25/opinion/25sat1.html

Man Who Killed His Family Found Dead in Prison

October 9, 2008

Filed at 12:52 p.m. ET

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

The New York Times

PENDLETON, Ind. (AP) -- An Indiana man convicted of raping and killing a

10-year-old neighborhood girl, then slaying his wife and three young daughters,

has died in prison of an apparent suicide.

Simon Rios of Fort Wayne was found hanging in his cell at the Pendleton

Correctional Facility Thursday morning. Prison spokesman David Barr says Rios

was pronounced dead after medical personnel couldn't revive him.

The 36-year-old had been serving five life terms for the 2005 deaths.

Rios pleaded guilty in 2007 to abducting the neighbor girl near her school bus

stop, driving her to a gravel pit and sexually assaulting and killing her. Days

later, he killed his wife and three young daughters.

An autopsy is planned.

Man Who Killed His

Family Found Dead in Prison, NYT, 9.10.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/us/AP-Indiana-Slayings.html

The Changing of the Guard

September 28, 2008

The New York Times

By BROOKE HAUSER

IN her 19 years as a corrections officer on Rikers Island, Barbara Williams

has been trapped in a mess hall with rioting inmates and thrown against an iron

gate by a man twice her size who left her with a fractured shoulder. But nothing

makes her wince like remembering the time an inmate commented on the way her

hips swayed ever so slightly beneath her boxy blue uniform, back when she first

came on the job.

“He said: ‘Damn! You remind me of a pantyhose commercial,’ ” recalled Ms.

Williams, who is in her late 40s and has a compact build and a deep, raspy

voice. “The feeling I had all that day was as if he had touched me or

something.”

She spoke of the episode one recent afternoon at Horizon Academy, a high school

for male inmates that is in the George Motchan Detention Center, one of eight

jails on the island holding inmates awaiting trial. Ms. Williams cited the man’s

comment as a crucial moment in her career.

“I saw right off that I have to change my demeanor: I have to be more forceful;

I have to harden myself,” said Ms. Williams, a single mother of two grown

daughters. That very night, she went back to her apartment in Jamaica, Queens,

and practiced stiffening her walk in front of a mirror.

“It’s like I tell my daughters: In life, you have to know when to be a woman and

when to be a lady,” she said. “I don’t feel that ladies belong in jail. So, that

softer part of me, I try to leave outside. I walk in here, and I try to be 110

percent woman.”

Women have worked in the city’s Department of Correction for decades, but never

in such large numbers as they do today. Women make up 45 percent of about 9,300

uniformed employees of the department, according to the agency. From guards to

wardens to the four-star chief, Carolyn Thomas, they fill almost every rank. And

in many respects, they are changing the culture of the city’s jails.

Walk down the corridors of any of the city’s 11 active jails, and it is clear

that not only are there a high number of female officers, but a majority of

those women — 75 percent — are black, said Stephen Morello, a department

spokesman. They are former soldiers, beauticians and bank tellers. They are

single mothers who took the job to support their children. They are grandmothers

like Angela Crim (“Crime without the ‘E,’ ” she says sweetly), who carries

handwritten Scripture in her purse and says she tries not to judge the men whom

she guards.

Some of the women are natural caretakers who dispense wisdom to inmates along

with bars of lye soap. Others are hard-nosed disciplinarians. But all the women

have one thing in common: They are taking their place in a world traditionally

dominated by men.

Nowhere is their sense of sorority more evident than in the women’s locker room,

where pictures of Barack Obama and male models with rippling torsos provide a

little relief after a long shift, and jars of hair products like Queen Helene

Styling Gel clutter the sink counters.

Upward Bound

Ask any woman in the city’s Correction Department why she wanted a job that

brings with it such stress and potential danger, and she’ll tell you that it’s

the security. Such a career, in which no college degree is required and the top

yearly pay for an officer is $75,000, can mean the difference between a life of

hardship and a ticket into the middle class.

“I don’t think anybody grows up saying, ‘I want to be in charge of inmates,’ ”

said Chantay Forbes, a 30-year-old single mother from East New York, Brooklyn,

who took the corrections officer’s exam about a decade ago when she was pregnant

with her son. She recently bought a house upstate.

“All I saw was what it could do for my future,” added Ms. Forbes, a newly

promoted captain. “If it wasn’t for this job, I might not be able to own a home

right now.”

Several factors explain the rising number of women entering the city’s

Correction Department. One is the 1977 United States Supreme Court decision in

Dothard v. Rawlinson, a watershed sex discrimination case that helped opened

doors for women in law enforcement.

Another is the fact that in the mid-’80s, the agency’s third female

commissioner, Jacqueline McMickens, began assigning female guards to all-male

jails that were once off limits to them. More recently, academic experts

suggest, labor shortages and an overhaul of the welfare system have driven more

women into the field.

But nothing beats word of mouth. Over the years, mothers and daughters, sisters

and girlfriends have recruited one another. One recruit, Suzeth Orr, a

hairdresser who used to work at a salon in Downtown Brooklyn, learned about the

job from two clients who worked for the department. “They said it’s not a hard

job,” she said. “It’s actually safe.”

Statistics bear that out. Last year was the safest on record for the city’s

jails, according to the department, and many female corrections officers think

that the decrease in violence is linked in part to their presence.

“The female touch is a little more gentle,” said Joandrea Davis, a warden who

runs a jail for sentenced male inmates on Rikers and keeps her office stocked

with bottles of Perrier and candy-apple-scented hand lotion. “You don’t have

that machismo that comes into confrontational situations, and sometimes we’re

able to quell things.”

But not all the time. “It is a jail,” she added. “We’re not dealing with

choirboys here.”

It’s impossible to quantify the exact impact women have had on the city’s jails.

But the system has seen changes.

“Certainly it disrupts a culture that is all about masculinity; we see both

resistances and progress,” said Dana Britton, a sociology professor at Kansas

State University and the author of the 2003 book “At Work in the Iron Cage: The

Prison as Gendered Organization.”

And Commissioner Martin Horn, the Correction Department’s top official, notes

that the increased number of women brings unique challenges.

He ticked off a litany of complicated issues: “Do women search men? How far do

they go? Do you do a pat frisk? Do you do a strip search? Where does the right

of the female officer to do the full range of her duties of her job bump up

against the privacy rights of the inmate or the sensibilities of the female

officer? The skies don’t open up and reveal an answer.”

Shaping an Inmate’s Life

Nearly two decades after perfecting her walk in front of the mirror, Barbara

Williams is, by her own account, “Mom to everybody.” She has one daughter

heading to law school, and the other is a small-business entrepreneur.

Neighborhood children flocked to Ms. Williams’s home when they needed advice, or

just a sandwich. But to male corrections officers, she is simply Nana, an

affectionate nickname for a grandmother.

“Hey, Grandma!” a beefy officer greeted her one recent afternoon as he passed

her desk at Horizon Academy. “Look at them big ol’ eyelashes!”

Ms. Williams, who has a fondness for false eyelashes and wears green-rimmed

glasses, declines to reveal her exact age, not because she’s afraid of seeming

old, she said, but because she wants to be perceived as older than she really

is, especially among male inmates.

She has had particular success shaping the life of a 23-year-old inmate named

Luis, who is facing a charge of attempted second-degree murder in connection

with a fight in a diner in Williamsburg.

One day last year, Luis told Ms. Williams that he wanted to attend classes at

Rikers, and she arranged for him to enter Horizon Academy. Although his

attendance was spotty at first, he eventually began attending class regularly.

“And he’s been with us ever since,” Ms. Williams said one day as she and Luis

sat in an empty classroom and discussed his progress. “He ironed out good.”

This has partly to do with the fact that male inmates may perceive female

officers as comforting surrogates for women they are close to outside.

“She remind me of a family member,” Luis said. “Just like my moms or my aunt,

always leading me the right way.”

Ms. Williams has heard it before.

“They all say that,” she said. “ ‘Oh, you remind me of my aunt.’ ‘You remind me

of my grandmother.’ ‘You remind me of my wife.’ I don’t pay it no mind.”

Many female officers were raised in environments not that different from those

in which inmates grew up. Some officers said they occasionally see in the jails

people whom they recognize from the world outside.

This has happened more than once to Ms. Williams, who has even recognized

inmates from her own neighborhood, including an old acquaintance who dared to

call her by her first name. She arranged for the inmate to be transferred to

another jail.

“Say we’re neighbors, and you come to jail,” she said. “All right, you did what

you did, but I do what I do. You’re going to respect my position. If we passed

sugar over the fence, there’s no more passing sugar over the fence. You got to

go! This is my space now.”

Trailblazers

If anyone has been a visible role model for female corrections officers, it is

Carolyn Thomas, 50, a 27-year veteran of the department. Two years ago, Ms.

Thomas was promoted to chief of the department, the highest-ranked uniformed

officer, second only to the commissioner. One of the first female corrections

officers to work with male inmates, she manages a staff of nearly 10,000 and an

inmate population of about 14,000, overseeing the daily operations of all the

city’s jails, court holding pens and prison wards.

On a recent afternoon in Ms. Thomas’s office on Rikers, a trailer decorated

inside with a fake gingerbread house and a bouquet of artificial daisies, roses

and baby’s breath, she talked about the challenges she faced as she moved up in

the ranks.

“You have to do your job 10 times better than a male to prove yourself, and you

do that by not asking for anything special,” said Ms. Thomas, wearing a starched

white shirt with four gold stars on the collar. In a lament commonly heard among

women in male-dominated jobs, she added: “You’re proving yourself in the sense

that ‘I can do this job as good as you can. I don’t belong to a clique. I don’t

belong to anything.’ ”

Women go through the same 15-week training as men at the Correction Academy in

Queens, where they learn defense tactics such as how to escape a chokehold and

how to use their riot batons. (The department does not keep statistics on the

number of injuries among women compared with men’s.)

But their progress has not been without problems. In the late ’80s, some female

employees made accusations about gender bias and sexual harassment. In 1990, in

one particularly incendiary lawsuit against the city, a group of current and

former female officers contended that they were forced to have abortions or take

dangerous assignments to keep their jobs. A $2.2 million settlement was reached

in 1991.

Much progress has been made since then, thanks to female pioneers in corrections

like Ms. Thomas. In fact, Ms. Davis, who rose from deputy warden, said her

promotions had been a bit of a sore spot between her and her husband, a

corrections officer whom she met on the job in 1989, when they were both

starting out as guards.

“It was difficult at first,” Ms. Davis said. “His peers would tease him: ‘You

got to salute your wife now.’ ”

Recently, Ms. Davis has begun grooming other women for promotions within the

department. Ms. Thomas also mentors women eager to move up. In return, they give

her homey mementos, among them a painted tile that reads, “It’s a rare person

who can take care of hearts while also taking care of business.”

After nearly 30 years in the department, the chief said, she has no desire to

become the next female commissioner. Instead, she is looking forward to a long

and prosperous retirement on Long Island.

“This is it for me,” Ms. Thomas said one afternoon in her office, breaking into

a gap-toothed smile. “I’m going to sit back and be a housewife, and I’m going to

go on to enjoy the second part of my life.”

•

Ms. Williams of Horizon Academy is also mulling her future. After almost two

decades working in the jail, she has just one more year before she can retire

and reap the benefits of a pension package that drew her into being a

corrections officer in the first place.

For now, Ms. Williams sits at her desk and watches the new crop of inmates, and

she is particularly struck by how young they seem, with their do-rags and baggy

jeans.

“Pull them pants up on you!” Ms. Williams sometimes says. “If you don’t fix

those pants, I’m going to bust you up!”

Often they listen. Just the other morning, a young fellow whom Ms. Williams had

reprimanded for acting up in class passed her desk. She asked whether he was

behaving himself.

“Yes, ma’am, Miss Williams,” he replied. “I love you, Miss Williams.”

To which she responded: “Don’t love me. Love your mother. She’s the one that’s

crying for you because you’re in here. You broke your mother’s heart.”

Sometimes, Ms. Williams said, “you got to hit them with the truth.”

The Changing of the

Guard, NYT? 28.9.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/28/nyregion/thecity/28guar.html?hp

Two Decades in Solitary

September 23, 2008

The New York Times

By JOHN ELIGON

He is one of New York’s most isolated prisoners, spending 23 hours a day for

the past two decades in a 9-by-6-foot cell. The only trimmings are a cot and a

sink-toilet combination. His visitors — few as they are — must wedge into a nook

outside his cell and speak to him through a 1-by-3-foot window of foggy

plexiglass and iron bars.

In this static existence, Willie Bosket, 45, seems to have gone from defiant

menace to subdued and empty inmate.

It was 30 years ago this month that a state law took effect allowing juveniles

to be tried as adults, largely in response to Mr. Bosket’s slaying of two people

on a New York subway when he was 15. He served only five years in jail for that

crime because he was a juvenile, sparking public outrage. But shortly after

completing his sentence, Mr. Bosket was arrested for assaulting a 72-year-old

man.

He once claimed to be at “war” with prison officials. He said he laughed at the

system and claimed to have committed more than 2,000 crimes as a child. He set

fire to his cell and attacked guards. Mr. Bosket was sentenced to 25 years to

life for stabbing a guard in the visitors’ room in 1988, along with other

offenses, leading prison authorities to make him virtually the most restricted

inmate in the state.

Now Mr. Bosket, who has gone 14 years without a disciplinary violation, does

mainly three things: read, sleep and think.

“Just blank” is how Mr. Bosket described his existence during a recent interview

at Woodbourne Correctional Facility, about 75 miles north of Manhattan.

“Everything is the same every day. This is hell. Always has been.”

He is scheduled to remain isolated from the general prison population until

2046.

Mr. Bosket’s seclusion is part of a bigger debate over the confinement of

troublesome inmates and the role of the prison system. Some say that Mr.

Bosket’s level of seclusion is draconian, that he should be given an opportunity

to rejoin the general population.

“He is a very dangerous person; he’s killed people,” said Jo Allison Henn, a

lawyer who helped represent Mr. Bosket roughly 20 years ago when he fought

unsuccessfully to have some of his restrictions removed. “I’m not saying he

should be released from custody entirely, just the custody that he is in. It is

beyond inhumane. I don’t think that too many civilized countries do that.”

But proponents of Mr. Bosket’s restrictions say he has proved to be something of

an incorrigible danger to prison guards and other inmates and cannot be trusted

in the general population. He is evaluated periodically, meaning he could rejoin

the general prison population before 2046, said Erik Criss, a spokesman for the

Department of Corrections.

“This guy was violent or threatening violence practically every day,” Mr. Criss

said. “Granted, it has been a while, but there are consequences for being

violent in prison. We have zero tolerance for that.”

From 1985 to 1994, Mr. Bosket was written up nearly 250 times for disciplinary

violations that included spitting on guards, throwing food and swallowing the

handle of a spoon, according to prison reports.

Few, if any, of the state’s current inmates have been in disciplinary housing

longer than Mr. Bosket, said Linda Foglia, a spokeswoman for the corrections

department.

Mr. Bosket says he wakes up at 7:15 every morning and gets a visit from a

counselor at 8. At 9, he gets his first of three doses of medication for asthma

and high cholesterol, he said. Lunch comes at 11:30, followed by more medication

at 1 p.m. and 5 p.m.

He is entitled to three showers a week. Other than one hour of recreation a day,

also solitary, he may leave his cell only for medical visits and haircuts. The

recreation area measures 34 feet by 17 feet, surrounded by nearly 9-foot-high

walls with bars on the top. Mr. Bosket said he was chained to a door during his

recreation time and could not walk more than six feet, but corrections officials

disputed that account, saying he was allowed to roam freely during his hour like

other inmates.

And while other prisoners in isolation are escorted to a visiting room when they

have guests, he must stay in his cell, speaking through the plexiglass.

Most of his waking hours, he said, are spent reading books, magazines,

newspapers and anything else he can get his hands on. His favorite magazine, he

said, was Elle.

“It’s very colorful,” he said. “It keeps me up to date on technology and the

world.”

Mr. Bosket has long been known as a paradox, a man of charm and extraordinary

intelligence but also of inexplicable fits of rage.

“It was like a terrifying metamorphosis when this spark within him went off, and

you could see the rage in him building,” said Robert Silbering, a former

prosecutor who tried Mr. Bosket for the subway murders. “I never have seen

anything like that before or afterward.”

The killings led Gov. Hugh L. Carey to sign a law allowing people as young as 13

to be tried as adults for murder. Mr. Bosket said he saw it as something of an

honor that he could drastically change a justice system that he said made him a

“monster.”

“If I’m the perfect example, then I’ve been taught well,” he said.

At the sight of a recent visitor, Mr. Bosket cheerfully nodded and, revealing a

small gap between his front teeth, gave a friendly, “Hi, how’s it going?”

He spoke with the aura of a professor, using deliberate gestures and emphasizing

the ends of many words. He often spoke in metaphors and used stories and

quotations to explain his philosophies.

As he contemplated his words, Mr. Bosket often folded his right arm across his

bulging stomach and lay the fingers of his left hand across his mouth and nose.

He sometimes rocked in his chair.

Despite his bleak situation, Mr. Bosket refused to concede defeat: “I’m not

broken down and never will be.”

His life has always been empty, he said.

“I grew up with nothing,” he said. “I was born with nothing. I still have

nothing. I will never have nothing. Forty-five years of living the way I have

lived, I like ‘nothing.’ No one can take ‘nothing’ from you.”

Mr. Bosket, who has spent all but two years in some form of lockup since he was

9, also said he had formed a “breastplate” from a lifetime of incarceration.

“I’ve become so callous to the poking of the sword that, literally, instead of

bleeding to death, the blood was drained and I became absent of concern, void of

emotions, cold — plain cold to the degree that not much affects me anymore,” he

said.

Yet Mr. Bosket did hint at something of a life of suffering.

“If somebody came to me with a lethal injection, I’d take it,” he said. “I’d

rather be dead.”

His change from vicious to quiescent, Mr. Bosket said, was a calculated move.

Growing up in Harlem, Mr. Bosket said, his heroes were revolutionaries like Huey

Newton and Assata Shakur. He said he believed blacks needed to use violence to

survive in the 1970s and ’80s.

But in 1994, he said, he sensed a change in society. “Blacks don’t need to go

and attack to get their message across,” he recalled thinking.

He said that he also wanted young people to see positive in his life, and that

continued violence could be counterproductive.

“I don’t believe at this point it’s strategic for me to be aggressive or

violent,” he said. “I’ve made my point.”

“I’m not proud of a lot of the things I’ve done,” he added.

Mr. Bosket’s sister, Cheryl Stewart, 51, said her brother had expressed remorse

in letters.

“What was done was wrong, and if he could redo it, he wouldn’t do it again,” she

said. “He knows what was done was wrong and is just sorry for what all has went

down.”

Though she corresponds with her brother, Ms. Stewart said she had not visited

him in 23 years because it was difficult to see him so confined. Mr. Bosket is

lucky to receive more than two visits a year.

Adam Mesinger, a television and movie producer, said he had visited Mr. Bosket

seven times over the past four years and is shopping a script for a movie about

Mr. Bosket’s life. He said that Mr. Bosket had always been warm and open with

him and that he would consider him a friend.

“I have no fear of him,” Mr. Mesinger said. “I don’t think he would ever harm

me. I don’t think he ever really wants to harm anybody.”

But not even Mr. Bosket would say that his days of violence are behind him.

“When you’re in hell,” he said, “you can’t predict the future.”

Two Decades in Solitary,

NYT, 23.9.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/23/nyregion/23inmate.html

$8 Billion Demand in California Prison Case

August 14, 2008

The New York Times

By SOLOMON MOORE

LOS ANGELES — The court-appointed receiver in charge of bringing California’s

prison health system into compliance with federal constitutional prohibitions

against cruel and unusual treatment of prisoners said Wednesday that he would

ask a judge to seize $8 billion from the state treasury to pay for improvements.

The federal receiver, J. Clark Kelso, said he would seek an order forcing

California to pay to build new medical facilities and upgrade existing ones at

its 33 state prisons.

Mr. Kelso said he would also urge Judge Thelton E. Henderson of Federal District

Court in San Francisco to hold Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger and Controller John

Chiang in contempt of court for their failure to pay for the plan. Mr. Kelso

said the state should pay the $8 billion over five years. The requests will be

heard in court on Sept. 22.

The receivership was created after the ruling in a class-action lawsuit that

California’s prison medical facilities did not meet constitutional standards.

The receiver’s demands come after the Legislature twice failed to pass a bill

that would have provided financing for the prison plan and as the state is

facing a $15.2 billion budget deficit. The plan would add $3.1 billion to this

year’s deficit.

Officials in the governor’s administration predicted that a final budget

settlement would resolve the receivership’s financing problem before the motion

was heard and acknowledged Mr. Kelso’s broad authority to demand state money.

Mr. Kelso said his prison health care proposals should take precedence over

other state mandates because of the constitutional issues involved.

“We still have people dying because of the conditions of health care in

California’s prisons,” Mr. Kelso said. “I need to move as quickly as I can to

rectify those conditions.”

California’s prisons are among the nation’s most crowded, with about 159,000

inmates in facilities designed for about 100,000.

$8 Billion Demand in

California Prison Case, NYT, 14.8.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/14/us/14prison.html?ref=us

Federal Report Finds Poor Conditions at Cook County Jail

July 18, 2008

The New York Times

By MONICA DAVEY

CHICAGO — People awaiting trial here at the Cook County Jail, one of the

nation’s largest local jails, have endured vastly inadequate medical care,

beatings at the hands of jail workers and dilapidated, dangerous building

conditions often left unrepaired for months, federal authorities said on

Thursday.

Grim images peppered 98 pages of federal findings from a sweeping 17-month

investigation about the jail, a West Side complex of buildings, the oldest of

which once housed Al Capone, that is now temporary home to about 9,800 men and

women.

The investigation by the civil rights division of the United States Department

of Justice and the office of Patrick J. Fitzgerald, the United States attorney

here, found that the jail had systematically violated the constitutional rights

of inmates. The Cook County Sheriff’s Office, which oversees the jail, strongly

denied that.

Among dozens of glimpses of life inside the jail, the federal investigators

wrote of an inmate who, after exposing himself to a female officer in July 2007,

was handcuffed, then hit and kicked by a group of jail officers. Some inmates

were not given their mental illness medications for weeks, the investigators

said, while others were given such drugs without records of why. In August 2006,

an inmate’s leg was amputated after an infection beneath a cast went untreated.

“You can’t have conditions where people are dying and being amputated,” Mr.

Fitzgerald said at a news conference.

The authorities would not say what had led in early 2007 to an investigation

into the jail, a 96-acre complex that houses mainly people waiting for their

trials and that, by some federal measures, was in 2007 among the top half-dozen

jails in the nation in numbers of inmates. About 100,000 people are admitted to

the Cook County Jail in a given year.

The outcome of the findings remains uncertain. Mr. Fitzgerald said he hoped to

reach an agreement with Cook County officials regarding changes at the jail. If

those efforts fail, a lawsuit is possible, prosecutors said, under a 1980 act

that has led to federal investigations into claims of systematic abuse at 430

jails, mental health facilities, nursing homes and other public institutions.

Perhaps most remarkable about the federal findings was the comprehensive scope

of the critique; almost no element of the jail seemed to meet muster.

Investigators pointed to poor supervision of inmates, the presence of weapons,

mistreatment of inmates, unsatisfactory dental, mental health and medical care,

electrical hazards, plumbing problems and ventilation failings.

The office of Thomas J. Dart, the Cook County sheriff since late 2006, issued a

statement on Thursday pledging to work with federal authorities on improvements,

but also taking strong issue with elements of the report. Most notably, the

statement said, many improvements have been put into place — before and after

federal investigators visited the jail in 2007.

“The report often relies on inflammatory language and draws conclusions based on

anecdotes and hearsay from inmates,” the statement said, adding that the

“allegations of systematic violations of civil rights at the jail are

categorically rejected by the sheriff’s office.”

In a separate statement, the office of Todd H. Stroger, president of the Cook

County Board, said that the county had in recent years provided financing for

more correctional officers, and that its facilities and maintenance workers had

finished 40,000 “work orders” at the jail in the past year. The county’s health

bureau “continues to work diligently to provide quality medical care for the

inmates,” it said.

Among causes of the jail’s troubles, the report pointed to inadequate staffing

(3,800 sworn officers and civilians work there), crowding, inadequate policies

and procedures, insufficient supervision and what Mr. Fitzgerald called a

culture of abuse.

In one case, investigators said, an inmate had to be hospitalized and placed on

a ventilator after being beaten by several officers.

“There’s clearly examples of corrections officers in organized groups beating

inmates to retaliate for verbal abuse, and people going to the hospital for it,”

Mr. Fitzgerald said. “And that’s got to stop.”

Violence among the inmates, too, is prevalent, investigators found. In less than

two months in 2006, seven knife fights caused serious injuries to some 33

inmates and seven jail workers. One inmate died.

And investigators identified “numerous instances” in which it said the county’s

failure to handle medical treatment properly “likely contributed to preventable

deaths, amputation, hospitalizations and unnecessary harm.”

Among the cases they cited was that of an H.I.V.-positive woman who complained

of shortness of breath and a cough, and was then found to have an abnormal

X-ray. Despite the test, the woman received no follow-up care, the investigators

said, and died in early 2006.

Catrin Einhorn contributed reporting.

Federal Report Finds

Poor Conditions at Cook County Jail, NYT, 18.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/18/us/18cook.html

Letters

Helping

Prisoners Re-enter Society

May 27, 2008

The New York Times

To the Editor:

Re “A Second Chance” (editorial, May 20):

Most re-entry efforts focus on prison inmates, yet about nine million people

cycle annually through our country’s jails. This is roughly 10 times the number

who leave prisons.

Jail inmates generally return to their communities after short incarcerations,

bringing with them a higher incidence of communicable diseases and mental health

conditions than exists in the general population.

Left untreated, these problems add to society’s health burden, emergency room

costs and municipal budgets. They also increase the likelihood that inmates will

commit new offenses and return to jail again, at public expense.

Jails are required to provide health care to inmates. This mandate creates an

opportunity to support re-entry efforts. By linking inmates with community-based

doctors, whom they can continue seeing after release, jails can stabilize

inmates’ health and help improve the health and safety of the community.

The Second Chance Act is a welcome step. We can do more to support jail inmates

by remembering that they are part of our communities and by providing them with

community-based health care during incarceration.

Keith Barton

South Londonderry, Vt., May 20, 2008

The writer, a physician, is medical director of Community Oriented Correctional

Health Services in Oakland, Calif.

•

To the Editor:

Financing of the Second Chance Act will support useful services to support the

transition from prison to community. But these services must also be accompanied

by removal of conflicting and counterproductive policies that stand in the way

of community reintegration.

For example, while New York State allocated $3.1 million to assist re-entry

efforts this year, the same budget projects an estimated $40 million in revenues

from fees and surcharges imposed on people convicted of crimes, 80 percent of

whom are indigent.

This crushing debt will leave releasees unable to acquire employment and

housing, reverting to a life of crime that jeopardizes the community safety.

If New York is truly committed to public safety and reintegration, it must stop

using financial penalties that undermine the intent of legislation like the

Second Chance Act.

Marsha Weissman

Executive Director

Center for Community Alternatives

New York, May 22, 2008

•

To the Editor:

Your editorial prompts me to note several aspects of New York’s second-chance

philosophy.

As The Times has noted, four upstate prisons are being kept open, fully staffed,

costing taxpayers $33 million a year, during tough fiscal times and when the

prison population is down by 8,000 people over the last decade. That money could

be better used for re-entry programs, lessening recidivism, bolstering the

upstate economy, and a real battle against crime.

We would never staff a school without students or a hospital without patients.

Let’s use criminal justice resources to reduce crime.

Glenn E. Martin

Associate Vice President of Policy and Advocacy

The Fortune Society

Long Island City, Queens, May 21, 2008

Helping Prisoners

Re-enter Society, NYT, 27.5.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/27/opinion/l27jails.html

Editorial

A Second Chance

May 20, 2008

The New York Times

With prison costs soaring, many states are understandably desperate for ways

to cut recidivism and increase the chances that newly released prisoners build

viable lives. The Second Chance Act, signed into law by President Bush last

month, would galvanize the re-entry effort, providing the states with money and

guidance. Now Congress must appropriate the promised dollars.

Some states are already leading the way. In Illinois — where the inmate

population has doubled since the late 1980s — Gov. Rod Blagojevich has begun a

promising re-entry program that could become a national model. The comprehensive

plan includes drug treatment, job training and placement and a variety of

community-based initiatives designed to help newly released inmates forge

successful postprison lives.

Illinois is also revamping its parole system by hiring more parole officers and

changing regulations so that parolees who commit lesser violations are dealt

with in their community — with counseling, drug treatment or more vigilant

monitoring — rather than being reflexively sent back to prison. The state is

working with Chicago’s Safer Foundation to provide job training and placement

for people just out of prison.

Parole-based reforms are also proving effective in Texas and Kansas. Both states

have expanded drug treatment and other services and have seen a drop in parole

revocations. Therapeutic programs that help ex-offenders reconnect with their

families — while providing them with medical and mental health care — are also

important.

A fully funded Second Chance Act would help other states develop their own

much-needed re-entry programs. The $330 million cost is a small price to pay to

reduce prison populations and give more ex-offenders a better chance to make it

on the outside.

A Second Chance, NYT,

20.5.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/20/opinion/20tue3.html?ref=opinion

New Tack Offers

Straying Parolees a Hand, Not Cuffs

May 17, 2008

The New York Times

By ERIK ECKHOLM

WICHITA, Kan. — Since his release in January after serving time for a 2006

theft conviction, Lonnie Kemp has violated his parole conditions several times,

getting drunk and kicked out of a halfway house and showing traces of marijuana

in urine tests. If this were a few years ago, he almost certainly would be back

in prison.

Similar parole violations after a previous theft conviction, in 1988, had

repeatedly landed him back inside. In those days, parole was enforced with a

spirit that officials recall, only half-jokingly, as “trail ’em, nail ’em, jail

’em,” overfilling the prisons but doing little to rehabilitate offenders.

Today, Kansas is a leader in a spreading national effort to make parole more

effective and useful — to reduce violations and reincarcerations as it protects

the public and seeks to help more offenders go straight. Mr. Kemp’s parole

officer is keeping close tabs on him, but instead of sending him for a punitive

stretch behind bars, he required Mr. Kemp to attend a substance-abuse program,

made sure he had a stable home with a relative and helped him get a job with a

construction company.

A similar transformation of the parole system has begun in several states

including Arizona, California, Georgia, Illinois, Michigan, New York and Texas.

It has been prompted in part by financial concerns: more than one-third of all

prison admissions are for parole violations, helping to drive an unsustainable

surge in prison-building.

It has also been driven by evidence that conventional parole supervision is

often a waste of resources. “If we sent him back to prison for 90 days, he’d

have to start all over with his life again,” Kent Sisson, parole director for

southern Kansas, said of Mr. Kemp. “Instead, he’s working, paying child support

and getting a G.E.D.”

Mr. Kemp, 51, said: “Before, you didn’t want to have parole officers around,

they’d send you back for almost anything. This time, I have positive people

around me and I can call my parole officer any time.”

An influential study in 2005 by the Urban Institute concluded that parole

supervision had little effect on the rate at which ex-prisoners were

re-arrested.

“Parole is a system set up to find failure,” said Michael Jacobson, president of

the Vera Institute of Justice in New York and a former chief of corrections and

probation for the city. “If what you’re interested in is finding failure and

putting people back in prison, it’s like shooting fish in a barrel.”

“But it doesn’t work in terms of public safety or public spending,” said Mr.

Jacobson, who praised Kansas as a pioneer in reforms.

As part of a get-tough spirit, a number of states in recent decades adopted

mandatory sentences and ended the historic discretion of parole boards over

release dates. Yet every state still has post-release supervision for most

offenders, averaging three years with stiff conditions like not consuming

alcohol, having urine tests, abiding by curfews, holding a job and meeting

regularly with a parole officer.

The most widespread change is the use of risk assessments that help officials

concentrate on those deemed most likely to commit new crimes. Those seen as low

risk are only loosely supervised, perhaps even allowed to just send in status

reports by mail.

“Half the offenders will do fine without any supervision,” Mr. Sisson said.

“We’re trying to better understand who are the 50 percent most likely to commit

more crimes, and how we can prevent that.”

The reformers are seeking a deeper change in attitude as well. “We’ve rewritten

all our job descriptions,” said Roger Werholtz, the Kansas secretary of

corrections. “The idea is to work with offenders to prevent them from violating

their conditions of release, rather than just monitoring them to see if

violations occur.”

In a sharp break with tradition, here and in some other states, parole agencies

are hiring officers with backgrounds in social work rather than law enforcement.

Parole officers are partnering with re-entry case workers who help prepare

prisoners for society with group therapy and housing and job assistance. They

start meeting prisoners well before their release, visit their families and may

even drive them to a job interview.

“We now talk about reducing the barriers to success,” said Mr. Sisson, who works

closely with the county re-entry director, Sally Frey.

In Kansas, parolees who threaten violence or openly defy the rules are still put

back in prison, and those who commit new crimes are put on trial. But for those

with lesser lapses, like Mr. Kemp, officials try to judge whether

reincarceration will be useful and may rely instead on a combination of help,

closer supervision and graduated sanctions.

Those seen as on the edge are required to report six evenings a week to a day

reporting center, where they attend group therapy meetings designed to make them

examine their motives and goals. They are often required to wear G.P.S. ankle

bracelets that record their movements and flag violations, like not being home

at curfew or, for a sex offender, going too near a school.

The changes, introduced over the last few years, are having measurable success,

Mr. Werholtz said.

In Kansas in 2003, he said, an average of 203 parolees were returned to prison

each month. By last year the number dropped to 103 a month. This could simply

mean that those violating parole were left unpunished. But the number of

convictions for new crimes by parolees has also declined; in the late 1990s, the

number of people on parole with new convictions averaged 424 a year; in the last

three years, it was down to 280 despite greater overall numbers under

supervision.

“I think the data pretty well establish that not only are we keeping people out

of prison at a better rate but that the amount of criminal activity they are

inflicting on the public has also declined,” Mr. Werholtz said.

The state has also been able to put off costly prison construction plans, he

said.

For inmates seen as high-risk, the re-entry team starts meeting them as early as

18 months before their release, often getting them into therapy groups and

starting schooling or job training. The parole officers may join in about six

months prior to release.

At the Winfield Correctional Facility, Mike Lentz, a parole officer who deals

with gang-connected offenders, recently joined a re-entry case worker, Brianna

Morphis, and a police liaison and a substance abuse specialist for Mr. Lentz’s

first meeting with prisoners he would later supervise.

One of them, Raphael Frazier, 27, has about four months left to serve on a

forgery conviction before starting parole. After being sent to prison in 1999

for aggravated robbery, Mr. Frazier was released on parole in 2003 but

re-imprisoned in 2004 for three months for absconding, or failure to report.

In 2005 he was convicted on a new charge of forgery. This time he had more help,

including group therapy and technical training in airplane building that should

land him a good job with one of the aircraft companies clustered around Wichita.

“It makes it easier knowing that people are out to help you, instead of driving

a stake in your back every time you turn around,” Mr. Frazier said. “I changed

my attitude.”

Another innovation is accountability panels, which are groups of community

volunteers, including former inmates, pastors and others who meet with newly

released offenders to offer encouragement and meet them later to discuss

problems or, ideally, congratulate them for completing parole. Panelists try to

be encouraging and helpful.

Lorlei Sontag, 37, who has struggled with crack addiction, recently met her

panel when she finally completed drug treatment after failed efforts. She told

of going to the dentist and seeing a familiar crack house through the window.

“My stomach was doing flips, but I didn’t go,” she said. As the group applauded

her progress, one panelist said she knew of a different dentist Ms. Sontag could

see in a less tempting location.

At Wichita’s day reporting center, Shontell J., 31, described his three months

wearing a G.P.S.-monitor ankle bracelet: “It’s irritating as hell, you can feel

it’s always there.”

Convicted when he was 17 for aggravated battery, he spent twelve and a half

years in prison and has a large scar on his cheek from a prison fight.

He started a roofing job while still in prison and has kept it for three years,

and he has adopted his girlfriend’s two children.

But he has also had serious parole violations that put him under house arrest

three times and then on daily reporting, with G.P.S. surveillance. Once he drove

to Topeka, beyond the permitted 50-mile limit, and got caught when he was

stopped for a traffic violation. He was arrested in a bar fight in another town

and he failed a urine test.

Now, still reporting most days but no longer wearing the ankle bracelet, he

said: “I tell myself a thousand times, I will not get into trouble.”

Mr. Kemp’s violations did not result in an ankle bracelet, but Mr. Lentz, his

parole officer, said that in the past he still would have sent him back for a

prison stay. In the new spirit, though, Mr. Lentz noted that “none of his

actions are so heinous or hurtful to the community.”

Mr. Kemp works from 7 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. each day, assembling lumber for a

company that makes trusses for houses. Initially he is making just $6.50 an hour

— “not much, but it pays the bills,” he said — but he is in line for a permanent

position and a raise.

“Things are going real smooth now,” he said.

He has one son who is 29 and another who is 14 and living with a relative.

“When I get myself together, I want my two boys to come live with me,” Mr. Kemp

said. “I want to be a father.”

New Tack Offers Straying

Parolees a Hand, Not Cuffs, NYT, 17.5.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/17/us/17parole.html

Editorial

Racial

Inequity and Drug Arrests

May 10,

2008

The New York Times

The United

States prison system keeps marking shameful milestones. In late February, the

Pew Center on the States released a report showing that more than 1 in 100

American adults are presently behind bars — an astonishingly high rate of

incarceration notably skewed along racial lines. One in nine black men aged 20

to 34 are serving time, as are 1 in 36 adult Hispanic men.

Now, two new reports, by The Sentencing Project and Human Rights Watch, have

turned a critical spotlight on law enforcement’s overwhelming focus on drug use

in low-income urban areas. These reports show large disparities in the rate at

which blacks and whites are arrested and imprisoned for drug offenses, despite

roughly equal rates of illegal drug use.

Black men are nearly 12 times as likely to be imprisoned for drug convictions as

adult white men, according to one haunting statistic cited by Human Rights

Watch. Those who are not imprisoned are often arrested for possession of small

quantities of drugs and later released — in some cases with a permanent stain on

their records that can make it difficult to get a job or start a young person on

a path to future arrests.

Similar concerns are voiced by the New York Civil Liberties Union, which issued

a separate study of the outsized number of misdemeanor marijuana arrests among

people of color in New York City.

Between 1980 and 2003, drug arrests for African-Americans in the nation’s

largest cities rose at three times the rate for whites, a disparity “not

explained by corresponding changes in rates of drug use,” The Sentencing Project

finds. In sum, a dubious anti-drug strategy spawned amid the deadly

crack-related urban violence of the 1980s lives on, despite changed

circumstances, the existence of cost-saving alternatives to prison for low-risk

offenders or the distrust of the justice system sowed in minority communities.

Nationally, drug-related arrests continue to climb. In 2006, those arrests

totaled 1.89 million, according to federal data, up from 1.85 million in 2005,

and 581,000 in 1980. More than four-fifths of the arrests were for possession of

banned drugs, rather than for their sale or manufacture. Underscoring law

enforcement’s misguided priorities, fully 4 in 10 of all drug arrests were for

marijuana possession. Those who favor continuing these policies have not met

their burden of proving their efficacy in fighting crime. Nor have they have

persuasively justified the yawning racial disparities.

All is not gloomy. Many states have begun expanding their use of drug treatment

as an alternative to prison. New York’s historic crime drop has continued even

as it has begun to reduce the number of nonviolent drug offenders in prison,

attesting to the oft-murky relationship between incarceration and crime control.

In December, the United States Sentencing Commission amended the federal

sentencing guidelines to begin to lower the disparities between the sentences

imposed for crack cocaine, which is more often used by blacks, and those imposed

for the powder form of the drug.

The looming challenge, says Jeremy Travis, the president of John Jay College of

Criminal Justice, is to have arrest and incarceration policies that are both

effective for fighting crime and promoting racial justice and respect for the

law. As the new findings attest, the nation has a long road to travel to attain

that goal.

Racial Inequity and Drug Arrests, NYT, 10.5.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/10/opinion/10sat1.html

|