|

History > 2008 > USA > Wars > Afghanistan (II)

Steve Sack

cartoon

Minnesota

The Minneapolis Star-Tribune

Cagle

2.7.2008

FACTBOX:

Military deaths in Afghanistan

Wed Jul 30, 2008

6:59am EDT

Reuters

(Reuters) - A British soldier in Helmand province, southern Afghanistan, was

killed in a firefight with Taliban militants on Tuesday, Britain's Ministry of

Defense said on Wednesday.

Here are figures for foreign military deaths as a result of violence or

accidents in Afghanistan since the Taliban government was toppled in 2001:

NATO/U.S.-LED COALITION FORCES:

United States 561

Britain 114

Canada 88

Germany 26*

Spain 23

Netherlands 16

Other nations 75

TOTAL: 903

* NOTE: Figures supplied by German Ministry of Defense.

Sources: Reuters/icasualties (

www.icasualties.org/oef ), compiled from official figures.

FACTBOX: Military deaths

in Afghanistan, R, 30.7.2008,

http://www.reuters.com/article/newsOne/idUKL051040220080730

Op-Ed Columnist

Drilling in Afghanistan

July 30, 2008

The New York Times

By THOMAS L. FRIEDMAN

Sometimes in politics, particularly in campaigns, parties get wedded to

slogans — so wedded that no one stops to think about what they’re saying,

whether the reality has changed and what the implications would be if their

bumper stickers really guided policy when they took office. Today, we have two

examples of that: “Democrats for Afghanistan” and “Republicans for offshore

drilling.”

Republicans have become so obsessed with the notion that we can drill our way

out of our current energy crisis that re-opening our coastal waters to offshore

drilling has become their answer for every energy question.

Anyone who looks at the growth of middle classes around the world and their

rising demands for natural resources, plus the dangers of climate change driven

by our addiction to fossil fuels, can see that clean renewable energy — wind,

solar, nuclear and stuff we haven’t yet invented — is going to be the next great

global industry. It has to be if we are going to grow in a stable way.

Therefore, the country that most owns the clean power industry is going to most

own the next great technology breakthrough — the E.T. revolution, the energy

technology revolution — and create millions of jobs and thousands of new

businesses, just like the I.T. revolution did.

Republicans, by mindlessly repeating their offshore-drilling mantra, focusing on

a 19th-century fuel, remind me of someone back in 1980 arguing that we should be

putting all our money into making more and cheaper IBM Selectric typewriters —

and forget about these things called the “PC” and “the Internet.” It is a

strategy for making America a second-rate power and economy.

But Democrats have their analog. For many Democrats, Afghanistan was always the

“good war,” as opposed to Iraq. I think Barack Obama needs to ask himself

honestly: “Am I for sending more troops to Afghanistan because I really think we

can win there, because I really think that that will bring an end to terrorism,

or am I just doing it because to get elected in America, post-9/11, I have to be

for winning some war?”

The truth is that Iraq, Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon and Pakistan are just

different fronts in the same war. The core problem is that the Arab-Muslim world

in too many places has been failing at modernity, and were it not for

$120-a-barrel oil, that failure would be even more obvious. For far too long,

this region has been dominated by authoritarian politics, massive youth

unemployment, outdated education systems, a religious establishment resisting

reform and now a death cult that glorifies young people committing suicide,

often against other Muslims.

The humiliation this cocktail produces is the real source of terrorism. Saddam

exploited it. Al Qaeda exploits it. Pakistan’s intelligence services exploit it.

Hezbollah exploits it. The Taliban exploit it.

The only way to address it is by changing the politics. Producing islands of

decent and consensual government in Baghdad or Kabul or Islamabad would be a

much more meaningful and lasting contribution to the war on terrorism than even

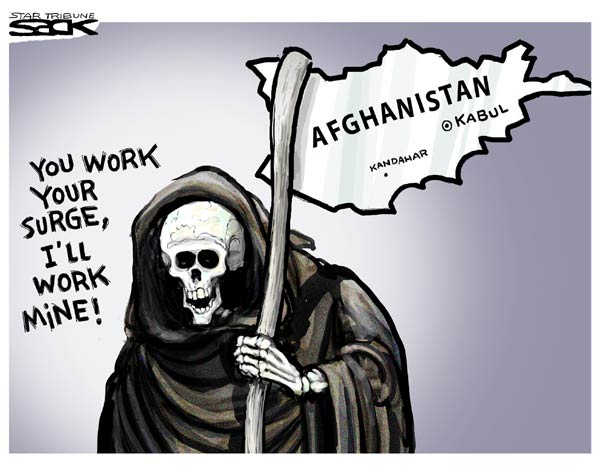

killing bin Laden in his cave. But it needs local partners. The reason the surge

helped in Iraq is because Iraqis took the lead in confronting their own

extremists — the Shiites in their areas, the Sunnis in theirs. That is very good

news — although it is still not clear that they can come together in a single

functioning government.

The main reason we are losing in Afghanistan is not because there are too few

American soldiers, but because there are not enough Afghans ready to fight and

die for the kind of government we want.

Take 20 minutes and read the stunning article in last Sunday’s New York Times

Magazine by Thomas Schweich, a former top Bush counternarcotics official focused

on Afghanistan, and dwell on his paragraph on Afghan President Hamid Karzai:

“Karzai was playing us like a fiddle: The U.S. would spend billions of dollars

on infrastructure improvement; the U.S. and its allies would fight the Taliban;

Karzai’s friends could get rich off the drug trade; he could blame the West for

his problems; and in 2009, he would be elected to a new term.”

Then read the Afghan expert Rory Stewart’s July 17 Time magazine cover story

from Kabul: “A troop increase is likely to inflame Afghan nationalism because

Afghans are more anti-foreign than we acknowledge, and the support for our

presence in the insurgency areas is declining ... The more responsibility we

take in Afghanistan, the more we undermine the credibility and responsibility of

the Afghan government and encourage it to act irresponsibly. Our claims that

Afghanistan is the ‘front line in the war on terror’ and that ‘failure is not an

option’ have convinced the Afghan government that we need it more than it needs

us. The worse things become, the more assistance it seems to receive. This is

not an incentive to reform.”

Before Democrats adopt “More Troops to Afghanistan” as their bumper sticker,

they need to make sure it’s a strategy for winning a war — not an election.

Drilling in Afghanistan,

NYT, 30.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/30/opinion/30friedman.html?ref=opinion

Is Afghanistan a Narco-State?

July 27, 2008

The New York Times

By THOMAS SCHWEICH

On March 1, 2006, I met Hamid Karzai for the first time. It was a clear,

crisp day in Kabul. The Afghan president joined President and Mrs. Bush,

Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and Ambassador Ronald Neumann to dedicate

the new United States Embassy. He thanked the American people for all they had

done for Afghanistan. I was a senior counternarcotics official recently arrived

in a country that supplied 90 percent of the world’s heroin. I took to heart

Karzai’s strong statements against the Afghan drug trade. That was my first

mistake.

Over the next two years I would discover how deeply the Afghan government was

involved in protecting the opium trade — by shielding it from American-designed

policies. While it is true that Karzai’s Taliban enemies finance themselves from

the drug trade, so do many of his supporters. At the same time, some of our NATO

allies have resisted the anti-opium offensive, as has our own Defense

Department, which tends to see counternarcotics as other people’s business to be

settled once the war-fighting is over. The trouble is that the fighting is

unlikely to end as long as the Taliban can finance themselves through drugs —

and as long as the Kabul government is dependent on opium to sustain its own

hold on power.

It wasn’t supposed to be like this. When I attended an Afghanistan briefing for

Anne Patterson on Dec. 1, 2005, soon after she became assistant secretary of

state for international narcotics and law-enforcement affairs, she turned to me

with her characteristic smile and said, “What have we gotten ourselves into?” We

had just learned that in the two previous months Afghan farmers had planted

almost 60 percent more poppy than the year before, for a total of 165,000

hectares (637 square miles). The 2006 harvest would be the biggest narco-crop in

history. That was the challenge we faced. Patterson — already a three-time

ambassador — made me her deputy at the law-enforcement bureau, which has

anti-crime programs in dozens of countries.

At the beginning of 2006, I went to the high-profile London Conference on

Afghanistan. It was a grand event mired in deception, at least with respect to

the drug situation. Everyone from the Afghan delegation and most in the

international community knew that poppy cultivation and heroin production would

increase significantly in 2006. But the delegates to the London Conference

instead dwelled on the 2005 harvest, which was lower than that of 2004,

principally because of poor weather and market manipulation by drug lords like

Sher Muhammad Akhundzada, who had been governor of the heroin capital of the

world — Helmand Province — and then a member of Afghanistan’s Parliament. So the

Afghans congratulated themselves on their tremendous success in fighting drugs

even as everyone knew the problem was worse than ever.

About three months later, after meeting with local officials in Helmand — my

helicopter touched down in the middle of a poppy field — I went to the White

House to brief Vice President Cheney, Secretary Rice, Defense Secretary Donald

Rumsfeld and others on the expanding opium problem. I advocated a policy

replicating what had worked in other countries: public education about the evils

of heroin and the illegality of cultivating poppies; alternative crops;

eradication of poppy fields; interdiction of drug shipments and arrest of

traffickers; and improvements to the judicial system.

I emphasized at this and subsequent meetings that crop eradication, although

claiming less than a third of the $500 million budgeted for Afghan

counternarcotics, was the most controversial part of the program. But because no

other crop came even close to the value of poppies, we needed the threat of

eradication to force farmers to accept less-lucrative alternatives. (Eradication

was an essential component of successful anti-poppy efforts in Guatemala,

Southeast Asia and Pakistan.) The most effective method of eradication was the

use of herbicides delivered by crop-dusters. But Karzai had long opposed aerial

eradication, saying it would be misunderstood as some sort of poison coming from

the sky. He claimed to fear that aerial eradication would result in an uprising

that would cause him to lose power. We found this argument perplexing because

aerial eradication was used in rural areas of other poor countries without a

significant popular backlash. The chemical used, glyphosate, was a weed killer

used all over the United States, Europe and even Afghanistan. (Drug lords use it

in their gardens in Kabul.) There were volumes of evidence demonstrating that it

was harmless to humans and became inert when it hit the ground. My assistant at

the time was a Georgia farmer, and he told me that his father mixed glyphosate

with his hands before applying it to their orchards.

Nonetheless, Karzai opposed it, and we at the Bureau of International Narcotics

and Law Enforcement Affairs went along. We financed ground-based eradication

instead: police using tractors and weed-whackers to destroy the fields of

farmers who refused to plant alternative crops. Ground-based eradication was

inefficient, costly, dangerous and more subject to corrupt dealings among local

officials than aerial eradication. But it was our only option.

Yet I continued to press for aerial eradication and a greater commitment to

providing security for eradicators. Rumsfeld was already in political trouble,

so when he started to resist my points, Rice quickly and easily shut him down.

The briefing at the White House was well received by Rice and the others

present. White House staff members also made clear to me that Bush continued to

be “a big fan of aerial eradication.”

The vice president made only one comment: “You got a tough job.”

Even before she got to the bureau of international narcotics, Anne Patterson

knew that the Pentagon was hostile to the antidrug mission. A couple of weeks

into the job, she got the story firsthand from Lt. Gen. Karl Eikenberry, who

commanded all U.S. forces in Afghanistan. He made it clear: drugs are bad, but

his orders were that drugs were not a priority of the U.S. military in

Afghanistan. Patterson explained to Eikenberry that, when she was ambassador to

Colombia, she saw the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) finance

their insurgency with profits from the cocaine trade, and she warned Eikenberry

that the risk of a narco-insurgency in Afghanistan was very high. Eikenberry was

familiar with the Colombian situation, but the Pentagon strategy was

“sequencing” — defeat the Taliban, then have someone else clean up the drug

business.

The Drug Enforcement Administration worked the heroin trafficking and

interdiction effort with the Afghans. They targeted kingpins and disrupted

drug-smuggling networks. The D.E.A. had excellent agents in Afghanistan, but

there were not enough of them, and they had seemingly unending difficulties

getting Mi-17 helicopters and other equipment that the Pentagon promised for the

training of the counternarcotics police of Afghanistan. In addition, the

Pentagon had reneged on a deal to allow the D.E.A. the use of precious ramp

space at the Kabul airport. Consequently, the effort to interdict drug shipments

and arrest traffickers had stalled. Less than 1 percent of the opium produced in

Afghanistan was being seized there. The effort became even more complicated

later in 2006, when Benjamin Freakley, the two-star U.S. general who ran the

eastern front, shut down all operations by the D.E.A. and Afghan

counternarcotics police in Nangarhar — a key heroin-trafficking province. The

general said that antidrug operations were an unnecessary obstacle to his

military operations.

The United States Agency for International Development (USAid) was also under

fire — particularly from Congress — for not providing better alternative crops

for farmers. USAid had distributed seed and fertilizer to most of Afghanistan,

but more comprehensive agricultural programs were slow to start in parts of the

country. The USAid officers in Kabul were competent and committed, but they had

already lost several workers to insurgent attacks, and were understandably

reluctant to go into Taliban territory to implement their programs.

The Department of Justice had just completed an effort to open the Afghan

anti-narcotics court, so capacity to prosecute was initially low. Justice in

Afghanistan was administered unevenly by tribes, religious leaders and poorly

paid, highly corruptible judges. In the rare cases in which drug traffickers

were convicted, they often walked in the front door of a prison, paid a bribe

and walked out the back door. We received dozens of reports to this effect.

And then there was the problem of the Afghan National Police. The Pentagon

frequently proclaimed that the Afghan National Army (which the Pentagon trained)

was performing wonderfully, but that the police (trained mainly by the Germans

and the State Department) were not. A respected American general in Afghanistan,

however, confided to me that the army was not doing well, either; that the

original plan for training the army was flimsy and underfinanced; and that,

consequently, they were using police to fill holes in the army mission. Thrust

into a military role, unprepared police lost their lives trying to hold

territory in dangerous areas.

There was no coherent strategy to resolve these issues among the U.S. agencies

and the Afghan government. When I asked career officers at the State Department

for the interagency strategy for Afghan counternarcotics, they produced the same

charts I used to brief the cabinet in Washington months before. “There is no

written strategy,” they confessed.

As big as these challenges were, there were even bigger ones. A lot of

intelligence — much of it unclassified and possible to discuss here — indicated

that senior Afghan officials were deeply involved in the narcotics trade.

Narco-traffickers were buying off hundreds of police chiefs, judges and other

officials. Narco-corruption went to the top of the Afghan government. The

attorney general, Abdul Jabbar Sabit, a fiery Pashtun who had begun a

self-described “jihad against corruption,” told me and other American officials

that he had a list of more than 20 senior Afghan officials who were deeply

corrupt — some tied to the narcotics trade. He added that President Karzai —

also a Pashtun — had directed him, for political reasons, not to prosecute any

of these people. (On July 16 of this year, Karzai dismissed Sabit after Sabit

announced his candidacy for president. Karzai’s office said Sabit’s candidacy

violated laws against political activity by officials. Sabit told a press

conference that Karzai “has never been able to tolerate rivals.”)

A nearly equal challenge in 2006 was the lack of resolve in the international

community. Although Britain’s foreign office strongly backed antinarcotics

efforts (with the exception of aerial eradication), the British military were

even more hostile to the antidrug mission than the U.S. military. British forces

— centered in Helmand — actually issued leaflets and bought radio advertisements

telling the local criminals that the British military was not part of the

anti-poppy effort. I had to fly to Brussels and show one of these leaflets to

the supreme allied commander in Europe, who oversees Afghan operations for NATO,

to have this counterproductive information campaign stopped. It was a small

victory; the truth was that many of our allies in the International Security

Assistance Force were lukewarm on antidrug operations, and most were openly

hostile to aerial eradication.

Nonetheless, throughout 2006 and into 2007 there were positive developments

(although the Pentagon did not supply the helicopters to the D.E.A. until early

2008). The D.E.A. was training special Afghan narcotics units, while the

Pentagon began to train Afghan pilots for drug operations. We put together

educational teams that convened effective antidrug meetings in the more stable

northern provinces. We used manual eradication to eliminate about 10 percent of

the crop. In some provinces with little insurgent activity, the eradication

numbers reached the 20 percent threshold — a level that drug experts see as a

tipping point in eradication — and poppy cultivation all but disappeared in

those areas by 2007. And the Department of Justice got the counternarcotics

tribunal to process hundreds of midlevel cases.

By late 2006, however, we had startling new information: despite some successes,

poppy cultivation over all would grow by about 17 percent in 2007 and would be

increasingly concentrated in the south of the country, where the insurgency was

the strongest and the farmers were the wealthiest. The poorest farmers of

Afghanistan — those who lived in the north, east and center of the country —

were taking advantage of antidrug programs and turning away from poppy

cultivation in large numbers. The south was going in the opposite direction, and

the Taliban were now financing the insurgency there with drug money — just as

Patterson predicted.

In late January 2007, there was an urgent U.S. cabinet meeting to discuss the

situation. The attendees agreed that the deputy secretary of state John

Negroponte and John Walters, the drug czar, would oversee the development of the

first interagency counternarcotics strategy for Afghanistan. They asked me to

coordinate the effort, and, after Patterson’s intervention, I was promoted to

ambassadorial rank. We began the effort with a briefing for Negroponte, Walters,

Attorney General Alberto Gonzales and several senior Pentagon officials. We

displayed a map showing how poppy cultivation was becoming limited to the south,

more associated with the insurgency and disassociated from poverty. The Pentagon

chafed at the briefing because it reflected a new reality: narcotics were

becoming less a problem of humanitarian assistance and more a problem of

insurgency and war.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime was arriving at the same

conclusion. Later that year, they issued a report linking the drug trade to the

insurgency and made a controversial statement: “Opium cultivation in Afghanistan

is no longer associated with poverty — quite the opposite.” The office

convincingly demonstrated that poor farmers were abandoning the crop and that

poppy growth was largely confined to some of the wealthiest parts of

Afghanistan. The report recommended that eradication efforts be pursued “more

honestly and more vigorously,” along with stronger anticorruption measures.

Earlier this year, the U.N. published an even more detailed paper titled “Is

Poverty Driving the Afghan Opium Boom?” It rejected the idea that farmers would

starve without the poppy, concluding that “poverty does not appear to have been

the main driving factor in the expansion of opium poppy cultivation in recent

years.”

The U.N. reports shattered the myth that poppies are grown by destitute farmers

who have no other source of income. They demonstrated that approximately 80

percent of the land under poppy cultivation in the south had been planted with

it only in the last two years. It was not a matter of “tradition,” and these

farmers did not need an alternative livelihood. They had abandoned their

previous livelihoods — mainly vegetables, cotton and wheat (which was in

severely short supply) — to take advantage of the security vacuum to grow a more

profitable crop: opium.

Around the same time, the United States released photos of industrial-size poppy

farms — many owned by pro-government opportunists, others owned by Taliban

sympathizers. Most of these narco-farms were near major southern cities. Farmers

were digging wells, surveying new land for poppy cultivation, diverting

U.S.-built irrigation canals to poppy fields and starting expensive reclamation

projects.

Yet Afghan officials continued to say that poppy cultivation was the only choice

for its poor farmers. My first indication of the insincerity of this position

came at a lunch in Brussels in September 2006 attended by Habibullah Qaderi, who

was then Afghanistan’s minister for counternarcotics. He gave a speech in which

he said that poor Afghan farmers have no choice but to grow poppies, and asked

for more money. A top European diplomat challenged him, holding up a U.N. map

showing the recent trend: poppy growth decreasing in the poorest areas and

growing in the wealthier areas. The minister, taken aback, simply reiterated his

earlier point that Afghanistan needed more money for its destitute farmers.

After the lunch, however, Qaderi approached me and whispered: “I know what you

say is right. Poverty is not the main reason people are growing poppy. But this

is what the president of Afghanistan tells me to tell others.”

In July 2007, I briefed President Karzai on the drive for a new strategy. He was

interested in the new incentives that we were developing, but became sullen and

unresponsive when I discussed the need to balance those incentives with new

disincentives — including arrests of high-level traffickers and eradication of

poppy fields in the wealthier areas of the Pashtun south, where Karzai had his

roots and power base.

We also tried to let the public know about the changing dynamics of the trade.

Unfortunately, most media outlets clung to the myth that the problem was out of

control all over the country, that only desperate farmers grew poppies and that

any serious law-enforcement effort would drive them into the hands of the

Taliban. The “starving farmer” was a convenient myth. It allowed some European

governments to avoid involvement with the antidrug effort. Many of these

countries had only one- or two-year legislative mandates to be in Afghanistan,

so they wanted to avoid any uptick in violence that would most likely result

from an aggressive strategy, even if the strategy would result in long-term

success. The myth gave military officers a reason to stay out of the drug war,

while prominent Democrats used the myth to attack Bush administration policies.

And the Taliban loved it because their propaganda campaign consisted of trotting

out farmers whose fields had been eradicated and having them say that they were

going to starve.

An odd cabal of timorous Europeans, myopic media outlets, corrupt Afghans,

blinkered Pentagon officers, politically motivated Democrats and the Taliban

were preventing the implementation of an effective counterdrug program. And the

rest of us could not turn them around.

Nonetheless, we stayed hopeful as we worked on what became the U.S.

Counternarcotics Strategy for Afghanistan. The Defense Department was initially

cooperative (as I testified to Congress). We agreed to expand the local meetings

and education campaign that worked well in the north. Afghan religious leaders

would issue anti-poppy statements, focusing on the anti-Islamic nature of drugs

and the increasing addiction rate in Afghanistan. In the area of agricultural

incentives, since most farmers already had an alternative crop, we agreed to

improve access to markets not only in Afghanistan but also in Pakistan and the

wider region. USAid would establish more cold-storage facilities, build roads

and establish buying cooperatives that could guarantee prices for legal crops.

With the British, we developed an initiative to reward provinces that became

poppy-free or reduced their poppy crop by a specified amount. Governors who

performed well would get development projects: schools, bridges and hospitals.

But there had to be disincentives too. We agreed to provide security for manual

poppy eradication, so that we could show the Afghan people that the

more-powerful farmers were vulnerable. We focused on achieving better

ground-based eradication, but reintroduced the possibility of aerial

eradication. We agreed to increase D.E.A. training of counternarcotics police

and establish special investigative units to gather physical and documentary

evidence against corrupt Afghan officials. And we developed policies that would

increase the Afghan capacity to prosecute traffickers.

Adding to the wave of optimism was the arrival of William Wood as the new U.S.

ambassador to Afghanistan. He had been ambassador in Colombia, so he understood

drugs and insurgency well. His view was that poppy cultivation was illegal in

Afghanistan, so he didn’t really care whether the farmers were poor or rich. “We

have a lot of poor people in the drug trade in the U.S.A. — people mixing meth

in their trailers in rural areas and people selling crack in the inner cities —

and we put them in jail,” he said.

At first Wood advocated — in an unclassified e-mail message, surprisingly — a

massive aerial-eradication program that would wipe out 80,000 hectares of

poppies in Helmand Province, delivering a fatal blow to the root of the

narcotics problem. “If there is no poppy, there is nothing to traffic,” Wood

said. The plan looked good on paper, but we knew it would be impossible to sell

to Karzai and the Pentagon. Wood eventually agreed to language advocating, at a

minimum, force-protected ground-based eradication with the possibility of

limited aerial eradication.

Another ally for a more aggressive approach to the problem was David Kilcullen,

a blunt counterterrorism expert. He became increasingly concerned about the drug

money flowing to the Taliban. He noted that, while Afghans often shift

alliances, what remains constant is their respect for strength and consistency.

He recommended mobile courts that had the authority to execute drug kingpins in

their own provinces. (You could have heard a pin drop when he first made that

suggestion at a large meeting of diplomats.) In support of aerial eradication,

Kilcullen pointed out that, with manual eradication you have to “fight your way

in and fight your way out” of the poppy fields, making it deadly, inefficient

and subject to corrupt bargaining. Aerial eradication, by contrast, is quick,

fair and efficient. “If we are already bombing Taliban positions, why won’t we

spray their fields with a harmless herbicide and cut off their money?” Kilcullen

asked.

So it appeared that things were moving nicely. We were going to increase

incentives to farmers and politicians while also increasing the disincentives

with aggressive eradication and arrest of criminal officials and leading

traffickers. The Pentagon seemed on board.

Then it all began to unravel.

In May 2007, Anthony Harriman, the senior director for Afghanistan at the

National Security Council, in order to ensure the strategy paper would be

executed, decided to take it to the Deputies Committee — a group of cabinet

deputy secretaries led by Lt. Gen. Douglas Lute, whom President Bush had

appointed his “war czar” — which had the power to make the document official

U.S. policy. Harriman asked me to start developing an unclassified version for

public release.

Almost immediately, the Pentagon bureaucracy — particularly the South Asia

office — made an about-face. First, they resisted bringing the paper to the

deputies. When that effort failed (largely because of unexpected support for the

plan from new field commanders like Gen. Dan McNeill, who saw the

narcotics-insurgency nexus and were willing to buck their Pentagon minders), the

Pentagon bureaucrats tried to prevent the release of an unclassified version to

the public. Indeed, two senior Pentagon officials threatened me with

professional retaliation if we made the unclassified document public. When we

went ahead anyway, the Pentagon leaked the contents of the classified version to

Peter Gilchrist, a British general posted in Washington. Defense Department

officials were thus enlisting a foreign government to help kill U.S. policy — a

policy that implicitly recognized that the Pentagon’s “sequencing” approach had

failed and that the Defense Department would have to get more involved in

fighting the narcotics trade.

Gilchrist told me that the plan was unacceptable to Britain. Britain, apparently

joined by Sweden (which has fewer than 500 troops in a part of the country where

there is no poppy cultivation), sent letters to Karzai urging him to reject key

elements of the U.S. plan. By the time Wood and Secretary Rice pressed Karzai

for more aggressive action, Karzai told Rice that because some people in the

U.S. government did not support the plan, and some allies did not support it, he

was not going to support it, either. An operations-center assistant, who

summarized the call for me over my car phone just after it occurred, made an

uncharacteristic editorial comment: “It was not a good call, ambassador.”

Even more startling, it appeared that top Pentagon officials knew nothing about

the changing nature of the drug problem or about the new plan. When, through a

back channel, I briefed the under secretary of defense for intelligence, James

Clapper, on the relationship between drugs and the insurgency, he said he had

“never heard any of this.” Worse still, Defense Secretary Robert Gates testified

to Congress in December 2007 that we did not have a strategy for fighting drugs

in Afghanistan. I received a quick apology from the Pentagon counterdrugs unit,

which sent a memo to Gates informing him that we actually did have a strategy.

This dissension was, I believe, music to Karzai’s ears. When he convened all 34

Afghan provincial governors in Kabul in September 2007 (I was a “guest of

honor”), he made antidrug statements at the beginning of his speech, but then

lashed out at the international community for wanting to spray his people’s

crops and giving him conflicting advice. He got a wild ovation. Not surprising —

since so many in the room were closely tied to the narcotics trade. Sure, Karzai

had Taliban enemies who profited from drugs, but he had even more supporters who

did.

Karzai was playing us like a fiddle: the U.S. would spend billions of dollars on

infrastructure improvement; the U.S. and its allies would fight the Taliban;

Karzai’s friends could get rich off the drug trade; he could blame the West for

his problems; and in 2009 he would be elected to a new term.

This is not just speculation, even when you stick with unclassified materials.

In September 2007, The Kabul Weekly, an independent newspaper, ran a blunt

editorial laying out the issue: “It is obvious that the Afghan government is

more than kind to poppy growers. . . . [It] opposes the American proposal for

political reasons. The administration believes that it will lose popularity in

the southern provinces where the majority of opium is cultivated. They’re afraid

of losing votes. More than 95 percent of the residents of . . . the poppy

growing provinces — voted for President Karzai.” The editorial recommended

aerial eradication. That same week, the first vice president of Afghanistan,

Ahmad Zia Massoud, wrote a scathing op-ed article in The Sunday Telegraph in

London: “Millions of pounds have been committed in provinces including Helmand

Province for irrigation projects and road building to help farmers get their

produce to market. But for now this has simply made it easier for them to grow

and transport opium. . . . Deep-rooted corruption . . . exists in our state

institutions.” The Afghan vice president concluded, “We must switch from

ground-based eradication to aerial spraying.”

But Karzai did not care. Back in January 2007, Karzai appointed a convicted

heroin dealer, Izzatulla Wasifi, to head his anticorruption commission. Karzai

also appointed several corrupt local police chiefs. There were numerous

diplomatic reports that his brother Ahmed Wali, who was running half of

Kandahar, was involved in the drug trade. (Said T. Jawad, Afghanistan’s

ambassador to the United States, said Karzai has “taken the step of issuing a

decree asking the government to be vigilant of any business dealing involving

his family, and requesting that any suspicions be fully investigated.”) Some

governors of Helmand and other provinces — Pashtuns who had advocated aerial

eradication — changed their positions after the “palace” spoke to them. Karzai

was lining up his Pashtun allies for re-election, and the drug war was going to

have to wait. “Maybe we taught him too much about politics,” Rice said to me

after I briefed her on these developments.

Karzai then put General Khodaidad (who, like many Afghans, goes by only one

name) in charge of the Afghan counternarcotics efforts. Khodaidad — a

conscientious man, competent and apparently not corrupt — was a Hazara. The

Hazaras had no influence over the southern Pashtuns who were dominating the drug

trade. While Khodaidad did well in the north, he got nowhere in Helmand and

Kandahar — and told me so. Karzai had to have known this would be the case.

But the real test for the Afghan government and the Pentagon came with the

“force protection” issue. At high-level international conferences, the Afghans —

finally, under European pressure — agreed to eradicate 50,000 hectares (more

than 25 percent of the crop) in the first months of this year; and they agreed

that the Afghan National Army would provide force protection.

The plan was simple. The Afghan Poppy Eradication Force would go to Helmand

Province with two battalions of the national army and eradicate the fields of

the wealthier farmers — including fields owned by local officials. Protecting

the eradication force would also enable the arrest of key traffickers. The U.S.

military, which trained the Afghan army, would assist in moving the soldiers

there and provide outer-perimeter security. The U.S. military would not

participate directly in eradication or arrest operations; it would only enable

them.

But once again, Karzai and his Pentagon friends thwarted the plan. First,

Anthony Harriman was replaced at the National Security Council by a colonel who

held the old-school Pentagon view that “we don’t do the drug thing.” He would

not let me see General Lute or Stephen J. Hadley, the national security adviser,

when the force-protection plans failed to materialize. We asked numerous

Pentagon officials to lobby the defense minister, Abdul Rahim Wardak, for

immediate force protection, but they did little.

Consequently, in late March, the central eradication force set out for Helmand

without the promised Afghan National Army. Almost immediately, they came under

withering attack for several days — 107-millimeter rockets, rocket-propelled

grenades, machine-gun fire and mortars. Three members of the Afghan force were

killed and several were seriously wounded. They eradicated just over 1,000

hectares, about 1 percent of the Helmand crop, before withdrawing to Kabul.

This spring, more U.S. troops arrived in Afghanistan. They were effective,

experienced warriors — many coming from Iraq — but they knew little about drugs.

When they arrived in southern Afghanistan, they announced that they would not

interfere with poppy harvesting in the area. “Not our job,” they said. Despite

the wheat shortage and the threat of starvation, they gave interviews saying

that the farmers had no choice but to grow poppies.

At the same time, the 101st Airborne arrived in eastern Afghanistan. Its

commanders promptly informed Ambassador Wood that they would only permit crop

eradication if the State Department paid large cash stipends to the farmers for

the value of their opium crop. Payment for eradication, however, is disastrous

counternarcotics policy: If you pay cash for poppies, farmers keep the cash and

grow poppies again next year for more cash. And farmers who grow less-lucrative

crops start growing poppies so that they can get the money, too. Drug experts

call this type of offer a “perverse incentive,” and it has never worked anywhere

in the world. It was not going to work in eastern Afghanistan, either. Farmers

were lining up to have their crops eradicated and get the money.

On May 12, at a press conference in Kabul, General Khodaidad declared the 2008

anti-poppy effort in southern Afghanistan to be a failure. Eradication this year

would total less than a third of the 20,000 hectares that Afghanistan eradicated

in 2007. The north and east — particularly Balkh, Badakhshan and Nangarhar

provinces — continued to improve because of strong political will and better

civilian-military cooperation. But the base of the Karzai government — Kandahar

and Helmand — would have record crops, less eradication and fewer arrests than

in years past. And the Taliban would get stronger.

Despite this development, the Afghans were busily putting together an optimistic

assessment of their progress for the Paris Conference on Afghanistan — where, on

June 12, world leaders, including Karzai, met in an event reminiscent of the

London Conference of 2006. In Paris, the Afghan government raised more than $20

billion in additional development assistance. But the drug problem was a

nuisance that could jeopardize the financing effort. So drugs were eliminated

from the formal agenda and relegated to a 50-minute closed discussion at a

lower-level meeting the week before the conference.

That is where we are today. The solution remains a simple one: execute the

policy developed in 2007. It requires the following steps:

1. Inform President Karzai that he must stop protecting drug lords and

narco-farmers or he will lose U.S. support. Karzai should issue a new decree of

zero tolerance for poppy cultivation during the coming growing season. He should

order farmers to plant wheat, and guarantee today’s high wheat prices. Karzai

must simultaneously authorize aggressive force-protected manual and aerial

eradication of poppies in Helmand and Kandahar Provinces for those farmers who

do not plant legal crops.

2. Order the Pentagon to support this strategy. Position allied and Afghan

troops in places that create security pockets so that Afghan counternarcotics

police can arrest powerful drug lords. Enable force-protected eradication with

the Afghan-set goal of eradicating 50,000 hectares as the benchmark.

3. Increase the number of D.E.A. agents in Kabul and assist the Afghan attorney

general in prosecuting key traffickers and corrupt government officials from all

ethnic groups, including southern Pashtuns.

4. Get new development projects quickly to the provinces that become poppy-free

or stay poppy free. The north should see significant rewards for its successful

anticultivation efforts. Do not, however, provide cash to farmers for

eradication.

5. Ask the allies either to help in this effort or stand down and let us do the

job.

There are other initiatives that could help as well: better engagement of

Afghanistan’s neighbors, more drug-treatment centers in Afghanistan, stopping

the flow into Afghanistan of precursor chemicals needed to make heroin and

increased demand-reduction programs. But if we — the Afghans and the U.S. — do

just the five items listed above, we will bring the rule of law to a lawless

country; and we will cut off a key source of financing to the Taliban.

Is Afghanistan a

Narco-State?, NYT, 27.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/27/magazine/27AFGHAN-t.html?hp

Obama’s

Visit Renews Focus on Afghanistan

July 20,

2008

The New York Times

By CARLOTTA GALL and JEFF ZELENY

KABUL,

Afghanistan — Senator Barack Obama arrived in Afghanistan on Saturday, on a

high-profile foreign trip in a country that is increasingly the focus of his

clash with Senator John McCain over whether the war in Iraq has been a

distraction in hunting down terrorists.

Even as Mr. Obama met privately with American troops, military leaders and

Afghan officials in the eastern part of the country, Mr. McCain was questioning

his judgment on foreign policy. In a radio address on Saturday, he said Mr.

Obama had been wrong about the increase in troops in Iraq, a strategy Mr. McCain

said should be the basis for addressing deteriorating conditions in Afghanistan

as well.

As the American presidential campaign unfolded across borders and time zones,

Mr. Obama received support from an unexpected corner: Iraq’s prime minister,

Nuri Kamal al-Maliki, told a German magazine that he endorsed the Obama plan to

withdraw most American troops in a gradual timeline of 16 months.

Mr. Obama flew to eastern Afghanistan, near Pakistan, to get a firsthand look at

the region where American troops are feeling the brunt of increased attacks from

militants infiltrating the border. In selecting Afghanistan as an early stop in

his first overseas trip as the presumptive Democratic nominee, he was seeking to

highlight what he says is the central front in the fight against terrorism. He

made no public statements on his first day here.

The visit was part of a weeklong tour that will take him to Iraq, Israel and

Western Europe on a trip intended to build impressions, and counter criticism,

about his ability to serve on the world stage in a time of war. It carries

political risk, particularly if Mr. Obama makes a mistake — the three broadcast

network news anchors will be along for the latter parts of the trip — or is seen

as the preferred candidate of Europe and other parts of the world. But his

advisers believe it offers an opportunity for him to be seen as a leader who can

improve America’s image.

“I’m more interested in listening than doing a lot of talking,” Mr. Obama told

reporters before leaving Washington for a trip cloaked in secrecy because of

security concerns. “And I think it is very important to recognize that I’m going

over there as a U.S. senator. We have one president at a time.”

Even as the fragile economy has emerged as the chief issue on American voters’

minds, the arguments that reverberated from the United States to Afghanistan

served as a reminder that the nation is at war and that the candidates offer

very different backgrounds and approaches when it comes to national security.

Mr. Obama touched down here just before noon on Saturday, his aides said, after

stopping to visit, and play basketball with, American troops in Kuwait. In

Afghanistan, he received a briefing from military commanders at Bagram Air Base

and Afghan officials at an American base in Jalalabad. He was scheduled to meet

on Sunday with President Hamid Karzai before heading to Iraq.

While the Iraq war has been one of the dominant issues in the presidential

campaign, Afghanistan has moved to the forefront of the foreign policy plans of

both candidates. President Bush’s agreement to a “general time horizon” for

withdrawing American troops in Iraq has opened the door to new consideration of

strengthening the American and NATO presence in Afghanistan, which Mr. Obama and

Mr. McCain agree on in principle.

For months, Mr. McCain, the presumptive Republican nominee, has criticized his

rival for failing to visit Afghanistan and taking only one trip to Iraq. Even on

Saturday, in a radio address, Mr. McCain renewed his criticism and sought to

minimize Mr. Obama’s trip. “In a time of war,” Mr. McCain said, “the commander

in chief’s job doesn’t get a learning curve.”

Mr. McCain, whose campaign spokeswoman suggested that Mr. Obama was embarking on

a “campaign rally overseas,” said his rival was not going to Afghanistan and

Iraq with an open mind. “Apparently,” Mr. McCain said in his radio address,

“he’s confident enough that he won’t find any facts that might change his

opinion or alter his strategy. Remarkable.”

But Republicans were carefully watching Mr. Obama’s trip, which is rare in its

profile and scope for a presidential candidate. The White House also made clear

Saturday that it was monitoring Mr. Obama’s travels; it accidentally sent e-mail

to a broad list of reporters with the news report that the Iraqi prime minister

supported Mr. Obama’s proposed 16-month timeline for withdrawing combat troops

from Iraq.

In an interview with Der Spiegel magazine in Germany that was released on

Saturday, Mr. Maliki said he was not endorsing Mr. Obama’s candidacy, but called

his proposal “the right timeframe for a withdrawal.”

The magazine interview was far from helpful to the McCain campaign, and aides to

Mr. McCain sought to clarify Mr. Maliki’s remarks.

“John McCain believes withdrawal must be based on conditions on the ground,” Mr.

McCain’s senior foreign policy adviser, Randy Scheunemann, said in a statement.

“Prime Minister Maliki has repeatedly affirmed the same view, and did so again

today. Timing is not as important as whether we leave with victory and honor.”

Besides visiting Iraq, Mr. Obama is also set to meet with presidents, prime

ministers and opposition leaders as he travels to Jordan, Israel and three

European capitals, including Berlin, where he is to give a major speech on

Thursday. On the Afghanistan and Iraq leg of the trip, he is being joined by

Senators Chuck Hagel, Republican of Nebraska, and Jack Reed, Democrat of Rhode

Island; the two men have been mentioned as possible running mates for Mr. Obama.

The three senators, all of whom have been critical of the administration’s

policy in Iraq and Afghanistan, were casually dressed as they flew on Saturday

to Jalalabad, one of 13 provincial bases that are commanded by American forces

in the Regional Command East of the NATO force in Afghanistan. Many of those

provinces, including Kunar, Nuristan, Nangarhar, Khost and Paktika, line the

border with Pakistan’s turbulent tribal areas, where militant groups allied with

the Taliban and Al Qaeda have gained in strength and have increased attacks by

some 40 percent in recent months.

The governor of Nangarhar Province, Gul Agha Shirzai, was the only Afghan

official to meet the senators, along with the United States ambassador and

generals. A former mujahedeen commander with a brutal past, Mr. Shirzai is

nevertheless favored by the United States as someone who can get things done,

and has been praised for his tough action against poppy cultivation and official

corruption in his province. He is thought to have his own aspirations in Afghan

presidential elections next year.

“Barack Obama thanked the officials of Nangarhar and the people of Nangarhar for

eliminating poppy cultivation, fighting corruption,” Mr. Shirzai said by

telephone after the one-hour meeting, “and he promised that the United States

would give more help to Afghanistan and especially to Nangarhar.”

The senators flew back to Bagram Air Base, north of Kabul, at 5 p.m., the

governor said. At 6 p.m. two Chinook military helicopters landed at the United

States Embassy, as two more attack helicopters circled above.

Afghans in Kabul said they knew nothing of Mr. Obama’s visit; some interviewed

on the streets near the embassy did not even know who he was. But some who had

heard of him said they liked his message, in particular that he would pursue Al

Qaeda in Pakistan.

“So far what he is talking about is what Afghans want to hear: reduce troops in

Iraq, focus on Afghanistan and focus on Pakistan,” said Ashmat Ghani, an

influential tribal leader whose home province of Logar, just south of the

capital, is suffering from growing instability by insurgent groups.

Mr. Ghani, a critic of Mr. Karzai’s leadership who opposes his running for

another presidential term next year, also welcomed Mr. Obama’s recent criticism

that the Afghan president had not come out of his bunker to lead efforts in

reconstruction and building security institutions.

“We would welcome such a direct voice that would close up this problem,” Mr.

Ghani said.

Yet other Afghans interviewed were skeptical that a new American president would

make much difference for them.

“What have we seen from the current president that we should expect anything

from a future president?” said Abdul Wakil, 28, who runs a juice stall in the

street near the heavily guarded embassy in central Kabul.

Carlotta Gall reported from Afghanistan, and Jeff Zeleny from Washington. Larry

Rohter contributed reporting.

Obama’s Visit Renews Focus on Afghanistan, NYT, 20.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/20/us/politics/20obama.html?hp

Obama Lands in Afghanistan

July 20, 2008

The New YorkTimes

By JEFF ZELENY

WASHINGTON – Senator Barack Obama arrived in Afghanistan early Saturday

morning, opening his first overseas trip as the presumptive Democratic

presidential nominee, to meet with American commanders there and later in Iraq

to receive an on-the-ground assessment of military operations in the two major

U.S. war zones.

Mr. Obama touched down in Kabul about noon, according to a pool report released

by his aides. In addition to attending briefings with military leaders, he hoped

to meet with President Hamid Karzai of Afghanistan before flying to Iraq later

in the weekend.

His trip was cloaked in secrecy, which advisers said was due to security

concerns set forth by the Secret Service. His whereabouts have been unknown

since he departed Chicago. He left Andrews Air Force Base near Washington on

Thursday afternoon, according to a pool report, and turned up in Afghanistan on

Saturday.

Before he left the United States, he gave a brief outline of his trip to two

pool reporters traveling with him from Chicago to Washington. No reporters

accompanied him to Afghanistan.

“Well, you know, I’m more interested in listening than doing a lot of talking,”

Mr. Obama said. “And I think it is very important to recognize that I’m going

over there as a U.S. senator. We have one president at a time, so it’s the

president’s job to deliver those messages.”

Mr. Obama’s arrival opened a weeklong foreign trip that includes visits to Iraq

and two other stops in the Middle East as well as appearances in three European

capitals. His tour of Afghanistan and Iraq are part of a Congressional

delegation — similar to trips that Senator John McCain, the presumptive

Republican nominee, made in the spring — in which he is joined by Senators Chuck

Hagel, Republican of Nebraska, and Jack Reed, Democrat of Rhode Island, both of

whom have been mentioned as possible vice presidential running mates.

The international trip by Mr. Obama is intended to counter Republican criticism

— and one advanced by Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton during the Democratic

primary campaign — that he has too little experience in foreign affairs to serve

as a world leader.

His advisers said Mr. Obama chose to begin his trip in Afghanistan because he

believes that the region is among the most important foreign policy challenges

facing the United States.

“Well, I’m looking forward to seeing what the situation on the ground is,” Mr.

Obama told reporters on Thursday before he left Washington. “I want to,

obviously, talk to the commanders and get a sense, both in Afghanistan and in

Baghdad of, you know, what the most, ah, their biggest concerns are. And I want

to thank our troops for the heroic work that they’ve been doing.”

It is the first trip to Afghanistan for Mr. Obama, a member of the Foreign

Relations Committee. This week, he proposed deploying about 10,000 more troops

to battle resurgent forces in Afghanistan, a plan intended to shift the American

military focus from the Iraq war to what he calls the central fight against

terrorism.

The proposal has become a centerpiece of Mr. Obama’s foreign policy and a major

point of disagreement with Mr. McCain, who maintains that both places are major

battlegrounds and disputes Mr. Obama’s suggestion that the war in Iraq has

distracted the United States from its efforts in Afghanistan.

Mr. McCain has suggested to voters that Mr. Obama lacks the experience to serve

as commander in chief. He particularly criticized the Illinois Democrat for not

having held a single hearing in his capacity as chairman of the Foreign

Relations Committee’s subcommittee on European affairs.

“He’s going to go to the American people and say, ‘I want to be commander in

chief,’ ” Mr. McCain told reporters on Thursday, “and yet he has been the

chairman of the subcommittee that oversights NATO and he has never had a

hearing, nor has he ever visited Afghanistan.’ ”

But that criticism was dismissed this week by Senator Joseph R. Biden Jr. of

Delaware, the chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, who said issues

related to Afghanistan were intentionally being addressed “at the full committee

level.”

Mr. Obama’s trip is drawing considerable attention in the United States and

abroad. It is being carefully choreographed by his campaign strategists to

coincide with a new television advertisement in 18 states intended to highlight

his ideas on foreign policy and portray him as ready to serve as commander in

chief, which is one area where polls show that voters give an edge to Mr.

McCain.

In addition to visiting Iraq and Afghanistan, Mr. Obama is extending his

overseas tour, his first as a presidential candidate, to include a visit to

Amman, Jordan, on Monday, followed by stops in Jerusalem, the Palestinian

territories, Berlin, France and London.

Now that Mr. Obama has decided to take the trip, the McCain campaign is not sure

what to make of it. Jill Hazelbaker, the communications director for Mr. McCain,

offered a hint of the Republican criticism of the trip on Thursday by dismissing

it as “the first-of-its-kind campaign rally overseas.” But Mr. McCain sought to

temper the message, saying: “I’m glad he is going to Iraq. I am glad he is going

to Afghanistan. It’s long, long overdue if you want to lead this nation.”

Robert Gibbs, a senior campaign strategist for Mr. Obama, dismissed that

suggestion. He said the trip was rooted in substance, rather than politics.

“The trip is not at all a campaign trip, a rally of any sort,” Mr. Gibbs told

reporters on Friday. He said Mr. Obama would hold “a series of substantive

meetings with our friends and our allies to talk about the common challenges

that we face and the national security dangers for the 21st century.”

In the next week, Mr. Obama is scheduled to meet several foreign leaders,

including German Chancellor Angela Merkel, British Prime Minister Gordon Brown,

French President Nicolas Sarkozy, Jordan’s King Abdullah, Israeli Prime Minister

Ehud Olmert and President Shimon Peres and Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas.

Obama Lands in

Afghanistan, NYT, 20.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/20/us/politics/20OBAMA.html?hp

U.S. Abandons Site of Afghan Attack

July 17, 2008

The New York Times

By CARLOTTA GALL

KABUL, Afghanistan — American forces have abandoned the outpost in

northeastern Afghanistan where nine American soldiers were killed Sunday in a

heavy attack by insurgents, NATO officials said Wednesday.

The withdrawal handed a propaganda victory to the Taliban, and insurgents were

quick to move into the village of Wanat beside the abandoned outpost, Afghan

officials said. Insurgents nearly overran the barely built outpost in a dawn

raid on Sunday, the most deadly assault for United States forces in Afghanistan

since 2005.

Those forces have fought some of their most difficult battles in Kunar and

Nuristan Provinces, with their thickly forested mountainsides and steep ravines.

Guerrillas mount ambushes and rocket attacks from the mountains and then easily

escape.

Local people have been angered by civilian casualties caused by American

airstrikes aimed at militants, and some now may be cooperating with the

militants, Afghan officials said.

Rahmatullah Rashidi, the leader of the provincial council of Nuristan, said some

insurgents occupied Wanat on Tuesday immediately after American and Afghan

troops had withdrawn. “They were up in the forest not far away,” he said. But on

Wednesday, he added, a council of village elders persuaded the Taliban to leave,

saying they feared that the Taliban’s presence would draw more fighting.

The local police, who pulled out Tuesday with the American force, returned to

Wanat on Wednesday with the support of the tribal elders, Mr. Rashidi said. News

agencies quoted Omar Sami Taza, an official in the provincial governor’s office,

confirming that the area had fallen to the Taliban.

NATO officials described the area as part of Kunar, but in the Afghan government

the district falls under the jurisdiction of neighboring Nuristan. They played

down the pullout and did not confirm that Taliban forces had moved into Wanat.

In Kabul, Capt. Mike Finney, a spokesman for the NATO force, said that “the

citizens in Wanat and northern Kunar Province can be assured” that NATO and

Afghan troops would continue to patrol the district and maintain “a strong

presence in the area.”

“We are committed, now more than ever, to establishing a secure environment that

will allow even greater opportunities for development and a stronger Afghan

governmental influence,” he added.

Only 45 American soldiers and 25 Afghans had occupied the Wanat outpost for a

few days before the attack. Far outnumbered by militants, the force was nearly

overrun and fought a four-hour battle before the Taliban were repelled. In

addition to the nine American deaths, 15 American soldiers were wounded. Four

Afghan soldiers were wounded.

At the Pentagon, Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates and Adm. Mike Mullen,

chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said Wednesday that the attack, and other

recent cross-border strikes, underscored the need for more allied troops in

Afghanistan and more aggressive action by Pakistani security forces on the other

side of the border.

“There is no question that the absence of pressure on the Pakistani side of the

border is creating an opportunity for more people to cross the border and to

launch attacks,” Mr. Gates told reporters. “There is a real need to do something

on the Pakistani side of the border to bring pressure to bear on the Taliban and

some of these other violent groups.”

Admiral Mullen said the attacks probably foreshadowed even greater cross-border

violence. “We see this threat accelerating,” said Admiral Mullen, who met with

senior Pakistani officials in Islamabad on Saturday. “We see it almost becoming

a syndicate of different groups who heretofore had not worked closely together.”

The Bush administration is considering the withdrawal of more combat forces from

Iraq beginning in September, in part because of the need for more forces in

Afghanistan. Admiral Mullen offered no new timetable, but said, “We are clearly

working very hard to see if there are opportunities to send additional forces

sooner rather than later.”

Eric Schmitt contributed reporting from Washington.

U.S. Abandons Site of

Afghan Attack, NYT, 17.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/17/world/asia/17afghan.html

9 Americans Die in Afghan Attack

July 14, 2008

The New York Times

By CARLOTTA GALL

KABUL, Afghanistan — Taliban insurgents carried out a bold assault on a

remote base near the border with Pakistan on Sunday, NATO reported, and a senior

American military official said nine American soldiers were killed.

The attack, the worst against Americans in Afghanistan in three years,

illustrated the growing threat of Taliban militants and their associates, who in

recent months have made Afghanistan a far deadlier war zone for American-led

forces than Iraq.

The assault on the American base in Kunar Province was one of the fiercest by

insurgents since the American-led invasion of Afghanistan routed the Taliban and

Al Qaeda militants in late 2001.

The militants have since regained strength in the tribal areas of Pakistan,

which they have often used as a base for raids into Afghanistan, an increasingly

sore point for the American and Afghan governments.

The new American commander of NATO forces in Afghanistan emphasized that issue

on Sunday in an interview that took place before details of the Kunar attack

were disclosed, asserting that the militants were not only entering Afghan

territory but also firing at targets from the Pakistan side.

“It all goes back to the problem set that there are sanctuaries in the tribal

areas that militant insurgent groups are able to operate from with impunity,”

said the commander, Gen. David D. McKiernan, who took over the NATO-led

International Security Assistance Force in June.

General McKiernan said insurgents based in Pakistan had carried out some kind of

attack on Afghanistan “almost every day I have been here.”

It was the first time a senior commander had stated so clearly that militant

groups were not only infiltrating from across the border to attack but were also

firing from positions inside Pakistan.

NATO officials reported that nine soldiers were killed in the Kunar attack but

did not specify the nationalities, in accordance with the policy of letting

member countries report them first. A senior military official in Washington

said that all nine were American.

The Kunar attack also left at least 15 other NATO soldiers — almost certainly

Americans — and 4 Afghan soldiers wounded, and it was one of at least three

significant attacks on Sunday, including a devastating suicide bombing in a

southern city’s bazaar that killed at least 25 people, 20 of them civilians.

This year of the Afghanistan war is already proving to be the deadliest since

the American-led invasion. Bush administration officials are now considering a

redeployment of troops to Afghanistan from Iraq to help deal with the rising

threat.

Deaths of American troops and their allies for the last two months have been

higher than those inflicted in Iraq. In addition, nearly 700 Afghan civilians

were killed in the first five months of the year, a marked increase over

previous years, United Nations officials have said.

General McKiernan, a four-star general who commanded allied land forces during

the invasion of Iraq in 2003, said there were three main reasons for the

increase in violence: a change in tactics by the insurgents to small attacks on

more vulnerable targets, such as the civilian population, district centers and

convoys; the increasing progress of Afghan and NATO forces in pushing into

regions previously controlled by the Taliban, which has led to more fighting;

and the “deteriorating situation with tribal sanctuaries across the border” in

Pakistan.

General McKiernan’s comments followed a weeklong visit to the region by the

chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Adm. Mike Mullen, who discussed a wide

array of security issues with Pakistan’s leaders on Saturday in a surprise visit

to Pakistan.

Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates, after conferring with President Bush and

Stephen J. Hadley, the national security adviser, directed Admiral Mullen to add

the stop in Pakistan. Given that this was Admiral Mullen’s fourth trip to

Pakistan this year and his second in two months, the admiral’s talks with

Pakistani officials underscored the Bush administration’s increasing concern

over the rising violence in Afghanistan and its links with the Pakistan tribal

areas.

“The secretary wanted to take advantage of the fact that Admiral Mullen would be

in the region to reinforce our concern with the Pakistanis about the spike in

violence in Afghanistan and to keep the pressure on in the tribal areas,” Geoff

Morrell, the Pentagon press secretary, said in a telephone interview about

Admiral Mullen’s Pakistan stopover.

Capt. John Kirby, a spokesman for Admiral Mullen, said it was apparent to the

admiral that “the Pakistani leadership is aware of their challenges in the

border region, as well as of U.S. military concerns there, and are working to

address those challenges.”

Pakistan, for its part, has complained that American forces have repeatedly hit

Pakistani territory, in particular on June 10, when United States air and

artillery strikes killed 11 members of the Pakistani paramilitary force, the

Frontier Corps, manning a border post.

General McKiernan did not comment on the June 10 attack since a three-party

investigation into the border clash had not yet been concluded, but he was very

clear that militants were using their sanctuary in Pakistan to fire across the

border and that the NATO and American forces had the right to fire back. “We

have the ability to protect ourselves,” he said.

“The point that I am trying to make is that the border security situation is not

good, and that border runs for 2,500 kilometers,” or about 1,500 miles, he said.

While he expressed optimism that the American-led forces here would prevail and

the insurgency would be defeated, “I look at this problem regionally, the viable

outcome in Afghanistan to a large degree is dependent on some outcome in

Pakistan with these tribal areas. That is a problem that is not getting better

with time.”

The base that came under attack in Kunar Province on Sunday lies in one of the

most inhospitable mountainous regions where American forces have frequently

faced fierce battles with insurgents.

A NATO news release issued in Kabul said the insurgents attacked the Kunar base

with rocket-propelled grenades and mortars, using houses, shops and a mosque in

the nearby village of Wanat for cover. Both sides suffered casualties as the

insurgents were repulsed, it said.

The only bigger single death toll for the Americans in the Afghanistan war came

in June 2005 — also near Kunar — when an American Chinook helicopter was shot

down by Taliban gunners in heavy combat. All 16 aboard and three others on the

ground were killed.

The American command also reported a heavy clash on Sunday between Taliban

insurgents and Afghan and American forces patrolling in the southern province of

Helmand in which it estimated that 40 militants were killed by airstrikes as

boats and bridges across the Helmand River were destroyed.

A suicide bomber on a motorbike blew himself up in a busy bazaar in the town of

Deh Rawood in the southern province of Oruzgan, killing the local police chief

and four subordinates. Twenty civilians were also killed and 30 more were

wounded, the provincial police chief, Juma Gul Himat, said by telephone. Bodies

and wounded people were strewn across the street as the police rushed to help.

Taimoor Shah contributed reporting from Kandahar, Afghanistan, Jane Perlez from

Islamabad, Pakistan, and Eric Schmitt from Washington.

9 Americans Die in

Afghan Attack, NYT, 14.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/14/world/asia/14afghan.html?ref=asia

Taliban attacks spur calls for troops

14 July 2008

USA TODAY

By Tom Vanden Brook

WASHINGTON — A shortage of ground troops in Afghanistan has led the Pentagon

to significantly intensify its air campaign in the first half of the year to the

highest levels since 2003 to fight the resurgence of the Taliban.

However, the increased bombing has not slowed the Taliban, the fundamentalist

Islamic group that ran Afghanistan until its ouster by U.S. forces in late 2001.

On Sunday, Taliban fighters attacked a base near the Pakistan border, killing

nine U.S. soldiers and wounding 15.

Such Taliban strength, military officials and analysts say, shows the airstrikes

alone cannot stop attacks and that more ground troops are needed.

Three U.S. brigades of about 3,500 troops each are needed to bolster the 32,000

U.S. forces already in Afghanistan, said Adm. Michael Mullen, chairman of the

Joint Chiefs of Staff. U.S. troops make up about half of the allied forces

there. "The Taliban is clearly resurgent," Mullen said in a recent interview.

"We don't have enough troops there, and we need to get troops in there to really

meet the combat needs."

U.S.-led coalition warplanes dropped 1,853 bombs and missiles in Afghanistan

through June in 2008, according to data compiled by the Air Forces Central

Combined Air and Space Operations Center. That's a 40% increase from the same

period in 2007. The 646 weapons used in June was the second-highest monthly

total on record. The highest occurred in August 2007.

In eastern Afghanistan near the border with Pakistan, where many recent

airstrikes have occurred, attacks from insurgents have risen 40% this year. The

deaths of 28 U.S. troops in June, made it the deadliest month for U.S. troops in

Afghanistan since the war began in 2001.

Taliban fighters and al-Qaeda militants are hiding in neighboring Pakistan and

crossing into Afghanistan to launch many of their attacks. In a Saturday meeting

in Pakistan with President Pervez Musharraf, Mullen expressed his "growing

concern over the flow of insurgents across the border," according to his

spokesman, Navy Capt. John Kirby.

The Pentagon is sending more air power to the battle. Last week, the aircraft

carrier USS Lincoln was repositioned to the area to supply more attack planes,

Defense Secretary Robert Gates said.

Airstrikes can kill enemy fighters, but "you're not owning the terrain," said

Dakota Wood, a military analyst at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary

Assessments.

Civilian casualties have caused tensions between the military and the Afghan

government. Last week, an Afghan government probe found that a July 6 airstrike

killed 47 civilians. Coalition forces are investigating, Army Capt. Christian

Patterson said. "Civilians are never targeted," he said.

Commanders should coordinate airstrikes with local officials, said Michael

O'Hanlon, a military analyst at the Brookings Institution.

Taliban attacks spur

calls for troops, UT, 14.7.2008,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/military/2008-07-14-afghanistan_N.htm

2.45pm BST

US air strike wiped out Afghan wedding party, inquiry finds

Friday July 11, 2008

Guardian.co.uk

James Sturcke and agencies

This article was first published on guardian.co.uk on Friday July 11 2008.

It was last updated at 23:44 on July 11 2008.

A US air strike killed 47 civilians, including 39 women and children, as they

were travelling to a wedding in Afghanistan, an official inquiry found today.

The bride was among the dead.

Another nine people were wounded in Sunday's attack, the head of the Afghan

government investigation, Burhanullah Shinwari, said.

Fighter aircraft attacked a group of militants near the village of Kacu in the

eastern Nuristan province, but one missile went off course and hit the wedding

party, said the provincial police chief spokesman, Ghafor Khan.

The US military initially denied any civilians had been killed.

Lieutenant Rumi Nielson-Green, a spokeswoman for the US-led coalition, told AFP

today the military regretted the loss of any civilian life and was investigating

the incident.

The US is facing similar charges over strikes two days earlier in another border

area of Afghanistan.

The nine-member inquiry team appointed by the Afghan president, Hamid Karzai, to

look into the wedding party incident found only civilians had been killed in the

attack.

"We found that 47 civilians, mostly women and children, were killed in the air

strikes and another nine were wounded," said Shinwari, who is also the deputy

speaker of Afghanistan's senate.

"They were all civilians and had no links with the Taliban or al-Qaida."

Around 10 people were missing and believed to be still under rubble, he said.

The inquiry team were shown the bloodied clothes of women and children in a

visit to the scene.

The Red Cross said 250 people had been killed or wounded in five days of

military action and militant attacks in the past week.

The toll included the US-led air strikes and a suicide blast outside the Indian

embassy in Kabul on Monday that killed more than 40 people, including two Indian

envoys.

The UN said last month that nearly 700 Afghan civilians had lost their lives

this year - about two-thirds in militant attacks and about 255 in military

operations.

Karzai has pleaded repeatedly for western troops to take care not to harm