|

History > 2008 > USA > Health (IV)

Ramona Lamascola

with her mother, Theresa Lamascola.

Photograph: Ruby Washington

The New York Times

Doctors Say Medication Is Overused in Dementia

NYT

24.6.2008

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/24/health/24deme.html

Gene-Hunters Find Hope and Hurdles

in Schizophrenia Studies

July 31, 2008

The New York Times

By NICHOLAS WADE

Two groups of researchers hunting for schizophrenia genes on a

larger scale than ever before have found new genetic variants that point toward

a different understanding of the disease.

The variants discovered by the two groups, one led by Dr. Kari Stefansson of

Decode Genetics in Iceland and the other by Dr. Pamela Sklar of Massachusetts

General Hospital, are rare. They substantially increase the risk of

schizophrenia but account for a tiny fraction of the total number of cases.

This finding, coupled with the general lack of success so far in finding common

variants for schizophrenia, raises the possibility that the genetic component of

the disease is due to a large number of variants, each of which is very rare,

rather than to a handful of common variants.

“What is beginning to emerge is that a lot of the risk of brain diseases is

conferred by rare deletions,” Dr. Stefansson said. The three variants discovered

by his group and Dr. Sklar’s involve the deletion of large sections of DNA from

specific sites in a patient’s genome.

Their report, published online Wednesday by the journal Nature, follows a

finding in March from researchers at the University of Washington in Seattle

that rare deletions and duplications of DNA figure prominently in schizophrenia.

The new focus on rare mutations suggests that natural selection is highly

efficient at removing schizophrenia-causing genes from the population. Despite

selection against the disease, according to this new idea, schizophrenia

continues to appear because it is driven by a spate of new mutations that occur

all the time in the population.

“We’ve looked for common variants in schizophrenia and get almost nothing,” said

Dr. David Goldstein, a geneticist at Duke University and one of Dr. Stefansson’s

co-authors. “This means natural selection has done a really good job of purging

them away, and we’re left with rare variants, a constant flow of them, as the

principal driver of the disease.”

“This may be the case in other brain diseases, too,” Dr. Goldstein said,

“because successful cognitive functioning is a highly complex system and there

are many independent ways to take it down.”

One obvious way in which natural selection acts against the disease is that

schizophrenics have fewer children than others. “The brain diseases are those

where we find the biggest evidence for negative selection, “ Dr. Stefansson

said, a finding he found surprising because “I would have thought the brain was

a luxury organ when it comes to reproductive success.”

Devising treatments for schizophrenia could be more difficult if the disease is

caused by subsets of 2,000 rare variants, say, rather than by just 20 common

ones. But several experts said it was too early to know what mix of common and

rare variants may cause the disease and whether that might affect the search for

treatments.

The search for common variants in schizophrenia, however, has not been very

successful so far, though not for want of trying. There have been more than a

thousand studies, implicating 3,608 genetic variants.

But when all the data are pooled, only 24 of those variants turn out to be

statistically significant, according to an analysis in the current issue of

Nature Genetics by a group led by Dr. Lars Bertram of Massachusetts General

Hospital.

Most of the early studies had too few patients and focused on mutations in what

seemed to be plausible genes, an approach that is rarely successful. A new and

more fruitful method is to survey the whole genome without any prior

assumptions, a strategy made possible by new gene chips and a database of human

genetic variation known as the hapmap.

But even these genome-wide association studies have had little success in

finding common variants. Five such studies of schizophrenia have now been

completed, and one of the largest found no common variants, Dr. Bertram said.

The consortiums led by Dr. Stefansson and Dr. Sklar are still looking for common

variants but published their rare deletions now because they were so prominent,

Dr. Sklar said.

Should most of the genetic component of the disease turn out to depend on

multiple rare variants, the task of finding general treatments might seem to be

far harder than if a few common variants were involved. Dr. Stefansson said,

however, that was not the case.

“The only thing you need is to find pathways that are up- or down-regulated,” he

said. “The assumption that this is a more difficult situation is just not

correct.”

Dr. Thomas Insel, director of the National Institute of Mental Health, said the

new landscape might complicate development of genetic diagnostics for

schizophrenia but not necessarily of therapies.

“If you can understand the mechanism,” Dr. Insel said, “you should be able to

devise new treatments. So I think this is a big advance, not a signal for

hopelessness.”

Gene-Hunters Find

Hope and Hurdles in Schizophrenia Studies, NYT, 31.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/31/health/research/31gene.html

U.S. Blacks, if a Nation,

Would Rank High on AIDS

July 30, 2008

The New York Times

By LAWRENCE K. ALTMAN

If black America were a country, it would rank 16th in the world in the

number of people living with the AIDS virus, the Black AIDS Institute, an

advocacy group, reported Tuesday.

The report, financed in part by the Ford Foundation and the Elton John AIDS

Foundation, provides a startling new perspective on an epidemic that was first

recognized in 1981.

Nearly 600,000 African-Americans are living with H.I.V., the virus that causes

AIDS, and up to 30,000 are becoming infected each year. When adjusted for age,

their death rate is two and a half times that of infected whites, the report

said. Partly as a result, the hypothetical nation of black America would rank

below 104 other countries in life expectancy.

Those and other disparities are “staggering,” said Dr. Kevin A. Fenton, who

directs H.I.V. prevention efforts at the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention, the federal agency responsible for tracking the epidemic in the

United States.

“It is a crisis that needs a new look at prevention,” Dr. Fenton said.

In a separate report on Tuesday, the United Nations painted a somewhat more

optimistic picture of the worldwide AIDS epidemic, noting that fewer people are

dying of the disease since its peak in the late 1990s and that more people are

receiving antiretroviral drugs.

Nevertheless, the report found that progress remained uneven and that the future

of the epidemic was uncertain. The report was issued in advance of the 17th

International AIDS Conference, which begins this weekend in Mexico City.

The gains are partly from the Bush administration’s program to deliver drugs and

preventive measures to people in countries highly affected by H.I.V.

The Black AIDS Institute took note of that program in criticizing the

administration’s efforts at home. The group said that more black Americans were

living with the AIDS virus than the infected populations in Botswana, Ethiopia,

Guyana, Haiti, Namibia, Rwanda or Vietnam — 7 of the 15 countries that receive

support from the administration’s anti-AIDS program.

The international effort is guided by a strategic plan, clear benchmarks like

the prevention of seven million H.I.V. infections by 2010 and annual progress

reports to Congress, the group said. By contrast, it went on, “America itself

has no strategic plan to combat its own epidemic.”

In a telephone interview, Dr. Fenton said, “We recognize this is a crisis, and

clearly more can be done.”

The institute, based in Los Angeles, describes itself as the only national

H.I.V./AIDS study group focused exclusively on black people. Phill Wilson, the

group’s chief executive and an author of the report, said his group supported

the government’s international anti-AIDS program. But Mr. Wilson’s report also

said that “American policy makers behave as if AIDS exists ‘elsewhere’ — as if

the AIDS problem has been effectively solved” in this country.

The group also chided the government for not reporting H.I.V. statistics to the

United Nations for inclusion in its biannual report.

Dr. Fenton said the C.D.C. had ensured that its data were forwarded to officials

in the Department of Health and Human Services and was investigating why the

data were not in the United Nations report.

Others speaking for the agency said the answer would have to come from the State

Department, which did not respond to an inquiry.

Dr. Helene Gayle, president of CARE and a former director of H.I.V. prevention

efforts at the disease control centers, told reporters on Tuesday that the

United States needed to devote more resources to care for people with sexually

transmitted diseases. Such infections can increase the risk of H.I.V. infection.

The federal government and communities needed to promote more testing among all

people, particularly blacks, to detect H.I.V. infection in its earliest stages

when treatment is more effective, Dr. Gayle said.

Also, she said, more needed to be done to promote needle exchange programs,

which have proved effective in preventing H.I.V. infection among injecting drug

users but that are illegal in many places.

The United Nations report said that in Rwanda and Zimbabwe, changes in sexual

behavior had led to declines in the number of new H.I.V. infections.

Condom use is increasing among young people with multiple partners in many

countries and more young people are postponing their initial sexual intercourse

before age 15.

The percentage of pregnant women receiving antiretroviral drugs to prevent

transmission of H.I.V. to their infants increased to 33 percent in 2007 from 14

percent in 2005. During the same period, the number of new infections among

children fell to 370,000 from 410,000.

The United Nations report affirmed treatment gains in Namibia, which increased

treatment to 88 percent of the estimated need in 2007, from 1 percent in 2003;

and in Cambodia, where the percentage rose to 67 in 2007 from 14 percent in

2004. Other countries with high treatment rates are Botswana, Brazil, Chile,

Costa Rica, Cuba and Laos.

In most areas of the world, more women than men are receiving antiretroviral

therapy, the report said.

Despite inadequate monitoring systems in many countries, data suggest that most

of the H.I.V. epidemics in the Caribbean appear to have stabilized. A few have

declined in urban areas in the Dominican Republic and Haiti which have had the

largest epidemics in the region.

Increased treatment was partly responsible for a decline in AIDS-related deaths

to an estimated 2 million in 2007 from 2.2 million in 2005.

The AIDS epidemic has had less overall economic effect than earlier feared, the

report said, but is having profound negative effects in industries and

agriculture in high-prevalence countries.

The United Nations has set 2015 as the year by which it hopes to reverse the

epidemic. But even if the world achieved that goal, the report said, “the

epidemic would remain an overriding global challenge for decades.”

To underscore the point, the United Nations said that for every two people who

received treatment, five people became newly infected.

U.S. Blacks, if a

Nation, Would Rank High on AIDS, NYT, 30.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/30/health/research/30aids.html

The Price of Beauty

As Doctors Cater to Looks,

Skin Patients Wait

July 28, 2008

The New York Times

By NATASHA SINGER

Dr. Donald Richey, a dermatologist in Chico, Calif., has two office telephone

numbers: calls to the number for patients seeking an appointment for skin

conditions like acne and psoriasis often go straight to voice mail, but a

full-time staff member fields calls on the dedicated line for cosmetic patients

seeking beauty treatments like Botox.

Dr. Richey has two waiting rooms. The medical patients’ waiting room is

comfortable, but the lounge for cosmetic clients is luxurious, with soft music

and flowers.

And he has two kinds of treatment rooms: clinical-looking for skin disease

patients, soothing for cosmetic laser patients.

“Cosmetic patients have a much more private environment than general medical

patients because they expect that,” said Dr. Richey, who estimated that he spent

about 40 percent of his time treating cosmetic patients. “We are a little bit

more sensitive to their needs.”

Like airlines that offer first-class and coach sections, dermatology is fast

becoming a two-tier business in which higher-paying customers often receive

greater pampering. In some dermatologists’ offices, freer-spending cosmetic

patients are given appointments more quickly than medical patients for whom

health insurance pays fixed reimbursement fees.

In other offices, cosmetic patients spend more time with a doctor. And in still

others, doctors employ a special receptionist, called a cosmetic concierge, for

their beauty patients.

Dr. David M. Pariser, a dermatologist in Norfolk, Va., and the president-elect

of the American Academy of Dermatology, said some practices did maintain

preferential policies for cosmetic patients.

“The message is that the cosmetic patient is more important than the medical

patient, and that’s not a good message,” Dr. Pariser said.

At a time when dermatologists are trying to advance the idea of a national skin

cancer epidemic, such a two-tier system is raising concerns that the coddling of

beauty patients may divert attention from skin diseases.

A study published last year in The Journal of the American Academy of

Dermatology found that dermatologists in 11 American cities and one county

offered faster appointments to a person calling about Botox than for someone

calling about a changing mole, a possible sign of skin cancer.

And dermatologists nationwide are increasingly hiring nurse practitioners and

physicians’ assistants, called physician extenders, who primarily see medical

patients, according to a study published earlier this year in the same journal.

“What are the physician extenders doing? Medical dermatology,” Dr. Allan C.

Halpern, chief of dermatology at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in

Manhattan, said in a melanoma lecture at a dermatology conference this year.

“What are the dermatologists doing? Cosmetic dermatology.”

There are no published studies showing that the rise of beauty procedures has

caused harm to medical dermatology patients. If patients with skin problems have

difficulty getting appointments, it is because over the last 30 years the demand

to see skin doctors has far outstripped the number of physicians trained in the

specialty, said Dr. Jack S. Resneck Jr., an assistant professor of dermatology

at the medical school of the University of California, San Francisco.

Dr. Resneck, who researches professional issues in dermatology, said about

10,500 dermatologists now practiced in the United States, the majority devoting

little time to vanity medicine.

Even so, dermatologists perform several million beauty treatments annually,

according to estimates by the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery,

including more than two million anti-wrinkle injection treatments last year — an

increase of 130 percent over 2005.

Several patients interviewed for this article said that they believed the

dermatologists they visited for medical care treated them as potential cosmetic

consumers. Dianne Ryan, who works for an airline in Dallas, went to a

dermatologist in her insurance network three years ago after her husband pointed

out a mole growing on the side of her foot, she said. The doctor dismissed the

mole as benign, she said, but recommended she buy his brand of bleaching cream

for pigmentation on her face.

A few months later, Ms. Ryan said, she sought a second opinion from another

dermatologist, whose diagnosis was melanoma.

“I don’t know if dermatology, with all the new technology, is turning away from

melanoma or whether it is the glamour and excitement,” said Ms. Ryan, who was

called by this reporter after an exchange in a chat room of the Melanoma

Research Foundation. “If you do an extreme makeover on someone, you are a hero.”

Dermatology is one of the fields — along with plastic surgery and behavioral

sleep medicine — in which patients are not only willing to pay for

quality-of-life treatments that may not be covered by insurance, but also

willing to pay much more for such treatments than insurers would pay for a

medical procedure that takes a similar amount of time.

Some health insurers reimburse a doctor $60 to $90 for a visit including a

full-body skin cancer check that might take 10 minutes; for Botox injections to

the forehead, a doctor might receive $500 for 10 minutes, paid on the day of

treatment.

According to a presentation for doctors from Allergan, the makers of Botox, a

medical dermatology practice might have a net income of $387,198 annually, but a

dermatologist who decreased focus on skin diseases while adding cosmetic medical

procedures to a practice could net $695,850 annually. The same material advises

doctors to “identify and segment high priority customers.”

People who wish to avoid a cosmetic-driven practice should simply seek

appointments with medical dermatologists who focus on skin diseases, said Dr.

Alexa B. Kimball, the vice chairwoman of dermatology at Massachusetts General

Hospital in Boston.

But many dermatologists now offer both medical treatment and beauty procedures,

which can confuse patients. And some doctors differentiate between patients —

either within their own practices or by treating cosmetic patients in

stand-alone facilities called medical spas.

Lecturers at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, held in

San Antonio in February, encouraged such segregation.

For example, Dr. Jason R. Lupton, a dermatologist in Del Mar, Calif., advised

young physicians to oblige cosmetic patients by giving them appointments within

seven days; empty appointment slots could later be filled with general

dermatology patients, he said.

In a follow-up telephone interview, Dr. Lupton said that, in his own practice,

he accommodated medical and cosmetic patients equally.

In an interview, Dr. Susan H. Weinkle, a dermatologist in Bradenton, Fla., said

that she typically spends more time with cosmetic patients because they come in

wanting to look better, the kind of amorphous desire that takes longer to

satisfy than defined medical problems. One of her staff members always calls a

beauty client to follow up, she said.

“It is very rare that you would call an acne patient and say, ‘How are you doing

with that new prescription?’ ” Dr. Weinkle said. “But with a cosmetic patient,

the consultant calls them the next day.”

This dual-class treatment system is not limited to the fanciest of private

practices. Even academic institutions like the University of Michigan Health

System in Ann Arbor are openly catering to beauty consumers. The Web site of the

dermatology department warns a medical patient seeking an appointment to obtain

a referral from a primary care physician “regardless of your type of insurance.”

Meanwhile, the same Web site —

www.med.umich.edu/derm/patient/cdlcappointment.shtml — promotes the

attentiveness of its cosmetic doctors and encourages those seeking vanity

procedures to ask about the “convenient” valet parking.

A new profession — called aesthetic practice consultant — has emerged to advise

doctors in the care of cosmetic patients.

“Instead of laying on an exam table with a paper liner, you have them lay on a

sheet,” said Deborah Bish, a former nurse who works as a practice consultant in

Yardley, Pa. “You have to class it up for these patients.”

It makes economic sense that dermatologists competing for Botox dollars want to

create enticing environments, said Julie Cantor, a lawyer and medical school

graduate who teaches a course in medical ethics at the law school of the

University of California, Los Angeles. But Ms. Cantor said research was needed

to determine whether such environmental changes alter a doctor’s behavior with

medical patients.

“If you really started treating patients differently based on their ability to

pay out of pocket, that’s a real problem,” Ms. Cantor said. “People who want

their wrinkles fixed to go to a wedding should not be treated better than those

who have psoriasis.”

Dr. Richey, the Chico, Calif., dermatologist, said that in his practice, the

attention to cosmetic patients had no bearing on the treatment of medical

patients; he maintains daily walk-in slots for medical patients with urgent skin

problems, and many of his patients visit both sides of his practice.

“I don’t believe in differentiating,” Dr. Richey said.

Nonetheless, some medical patients said that they believed other dermatologists

brushed off their medical concerns in favor of marketing cosmetic procedures.

Melissa Bundy, a health communications manager in Atlanta, said that several

years ago she went to a dermatologist who seemed more interested in selling face

treatments than in conducting a thorough skin cancer examination. She has since

switched doctors.

“Cosmetic things, it’s a really great business,” Ms. Bundy said. “But it really

does seem to be at the expense of people like me getting the medical services

that we are looking for.”

As Doctors Cater to

Looks, Skin Patients Wait, NYT, 28.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/28/us/28beauty.html

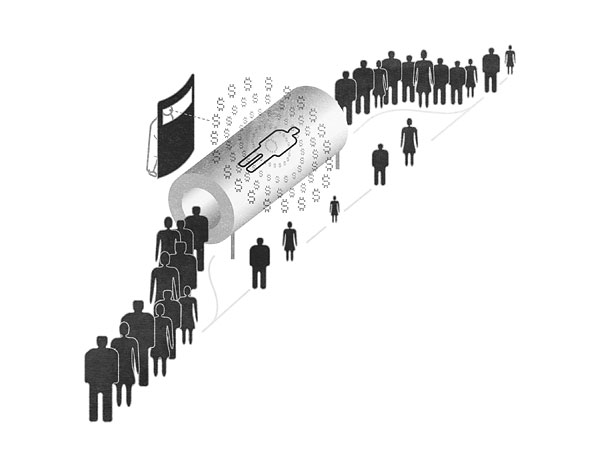

Illustration: John Hersey

Paying Doctors to Ignore Patients

NYT

24.7.2008

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/24/opinion/24bach.html

Op-Ed Contributor

Paying Doctors to

Ignore Patients

July 24, 2008

The New York Times

By PETER B. BACH

THE longstanding push-pull between Medicare and Congress has erupted again.

Last week, Congress, overriding a presidential veto, canceled Medicare’s

scheduled 10.6 percent cut in payment rates for doctors, and instead raised the

rates 1.1 percent. But this action fails to address the problem with the

Medicare payment system, which is not the amounts doctors are paid but the way

their payments are calculated.

Medicare pays doctors for specific services. If a patient has a checkup that

includes an X-ray, a urine analysis and a physical, Medicare pays the doctor

three separate fees.

Each fee is meant to reimburse the doctor for the time and skill he or she

devotes to the patient. But it is also supposed to pay for overhead, and this is

where the problem begins. To Medicare, a doctor’s overhead (or “practice

expense”) includes such items as rent, staff salaries and the cost of high-tech

medical equipment. When the agency pays a fee to a doctor who has performed a CT

scan, it is meant to cover some of the cost of buying or leasing the scanner

itself. Services using more expensive equipment generate higher fees.

Any first-year business school student can see the profit opportunity here. The

cost of a CT scanner is fixed, but a doctor earns fees each time it is used.

This means that a scanner becomes highly profitable as soon as it’s paid for.

In contrast, the doctor-patient visit, which involves no expensive equipment,

offers no significant profit opportunity. So the best way for a doctor to make

money in his practice is not to spend time with patients but to use equipment as

much as possible. That means moving the maximum number of patients through the

practice, and spending the minimum amount of time with each one.

From 2000 to 2005, the number of Medicare patients seen by doctors increased by

8.5 percent, while the number of services each one received was up 14 percent,

according to the Government Accountability Office.

It’s not only Medicare that pays doctors on a fee-for-service basis; most

private insurers do also. This is part of the reason that spending on physician

services nationwide has risen every year since 2000 by about $25 billion. This

year the tab will exceed $500 billion.

Doctors who do their own CT scanning and other imaging order roughly two to

eight times as many imaging tests as those who do not have their own equipment,

a 2002 study by researchers at the University of North Carolina found.

Altogether, doctors are ordering roughly $40 billion worth of unnecessary

imaging each year — which adds up to nearly 2 percent of the total Americans pay

for health care.

No wonder the Government Accountability Office last month urged Medicare to find

a way to constrain doctors’ use of imaging tests.

Over the years, Congress and Medicare have made various attempts to stamp out

some of the most egregious excesses in Medicare payments. Sometimes they have

succeeded. In 2004 and 2005, when Congress lowered the fees associated with

anti-testosterone drugs used to treat prostate cancer, urologists and other

doctors prescribed them less.

Around the same time, though, urologists started buying multimillion-dollar

radiation therapy machines for treating prostate cancer. Reimbursement for

radiation treatment remains very generous.

Clearly, scattershot strategies aimed at individual fees are unlikely to reduce

health care costs. More fundamental changes are needed in the way doctors are

paid.

For their time, doctors should be given a stipend for each of their patients. It

should be larger for patients with complicated medical conditions and smaller

for those who are healthy, and it should not be influenced by the number of

services or tests a doctor orders.

For overhead, doctors should be paid an amount that covers the typical cost of

tests and treatments needed to address a patient’s condition. This strategy —

known as “case rate” or “prospective” payment — is standard in American

hospitals. The hospital receives a payment for dealing with a patient’s

underlying condition rather than individual payments for each test and

treatment. This approach offers no incentive to run unneeded tests, and it has

been credited with substantially slowing the growth in Medicare payments to

hospitals.

Without changes to the way Medicare pays doctors, the fights in Congress over

raising or lowering payment rates will continue. And doctors will still have no

financial incentive to do what is most important: spend more time with their

patients.

Peter B. Bach, a doctor at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, was a senior

adviser to the administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

from 2005 to 2006.

Paying Doctors to Ignore

Patients, NYT, 24.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/24/opinion/24bach.html

Billionaires Back Antismoking Effort

July 24, 2008

Yhe New York Times

By DONALD G. MCNEIL JR

Bill Gates and Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg announced on Wednesday that they

will spend $500 million to stop people around the world from smoking.

The World Health Organization estimates that tobacco will kill up to a billion

people in the 21st century, most of them in poor and middle-income countries. In

an effort to cut that number, Mr. Bloomberg’s foundation plans to commit $250

million over four years on top of $125 million he announced two years ago. The

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is allocating $125 million over five years.

That far outstrips current spending of about $20 million a year on antismoking

campaigns in poor and middle-income countries, according to a recent W.H.O.

report.

The $500 million would be spent on a multipronged campaign — nicknamed Mpower —

that Mr. Bloomberg and Dr. Margaret Chan, director of the health organization,

outlined in February. It coordinates efforts by the Bloomberg Initiative to

Reduce Tobacco Use, the health organization, the World Lung Foundation, the

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention Foundation and the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids.

The campaign will urge governments to sharply raise tobacco taxes, outlaw

smoking in public places, outlaw advertising to children and free giveaways of

cigarettes, start antismoking advertising campaigns and offer their citizens

nicotine patches or other help quitting. Third world health officials, consumer

groups, journalists, tax officers and others will be brought to the United

States for workshops on topics like lobbying, public service advertising,

catching cigarette smugglers and running telephone hot lines for smokers wanting

to quit. A list of grants is at tobaccocontrolgrants.org.

The campaign will concentrate on five countries where most of the world’s

smokers live: China, India, Indonesia, Russia and Bangladesh.

Dr. Richard Peto, an Oxford epidemiologist who leads studies on the effects of

smoking in the developing world, called the announcement “excellent news.”

“I reckon this will avoid tens of millions of deaths in my lifetime and hundreds

of millions in my kids’ lifetimes,” he said.

Catherine Armstrong, a spokeswoman for British American Tobacco — one of the

Western tobacco companies that focuses on sales to the third world — would not

comment directly on the new initiative. But she said, “We have no problem with

government organizations educating people on the risks of tobacco.”

Mr. Bloomberg, founder of the financial news company bearing his name and

creator of the Bloomberg Family Foundation, has long been known for his

antipathy to tobacco. During his administration, New York has adopted several

antismoking measures, including a ban on smoking in bars and restaurants, and

significant increases in cigarette taxes. His foundation gave $2 million to the

W.H.O. to underwrite its latest tobacco report.

“When I announced this initiative, I said that I hoped that others would step

forward,” said Mr. Bloomberg, referring to his initial $125 million commitment,

in a written statement released before the afternoon news conference in Midtown

Manhattan. “I’m delighted Bill and Melinda Gates are supporting one of the most

important public health efforts of our time.”

It promises to be a struggle. Cigarettes are not only highly addictive and

supported by huge advertising campaigns, they are also an important source of

income for many foreign governments. In some countries, tobacco is a state-owned

monopoly, and low and middle-income countries collect $66 billion a year in

tobacco taxes.

About 5 percent of countries in the world have any antismoking measures like

those the campaign envisions.

But Dr. Peto said anti-smoking campaigns were already having effects in some

countries. He surveyed thousands of smokers in China in the 1990s — “before the

government was taking it seriously,” he said — and found 4 percent who

identified themselves as former smokers. In his more recent surveys, he said,

there were 20 percent.

In India, where people have long chewed tobacco but widespread smoking is more

recent, Dr. Peto said he found almost no one who had quit. “India is where China

was in the mid-1990s,” he said.

Waves of lung cancer deaths — which typically begin about 40 years after smoking

takes hold in a society — help persuade the next generation that smoking is

dangerous, as in the United States in the 1960s, he said. And, he added, “When

doctors and journalists start to take it seriously, things start to change.”

The Gates foundation’s main focus has been global health, but up until now it

has concentrated mostly on infectious diseases like AIDS, tuberculosis and

malaria rather than chronic ones like the cancers caused by tobacco. A

spokeswoman for the foundation said that some years ago, Mr. Gates read “The

Tobacco Atlas,” a 2002 publication from the World Health Organization describing

worldwide tobacco use — much of it by children. “He said, ‘Wow, why aren’t we

looking at this?’ ” said the spokeswoman, Melissa Derry.

Mr. Gates recently gave up his post as president of Microsoft to devote himself

full time to running the foundation, which has assets of about $37 billion.

Billionaires Back

Antismoking Effort, NYT, 24.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/24/health/24smoke.html?hp

Health Plan From Obama Spurs Debate

July 23, 2008

The New York Times

By KEVIN SACK

It is one of the most audacious promises in a campaign that

has been thick with them.

In speech after speech, Senator Barack Obama has vowed that he will lower the

country’s health care costs enough to “bring down premiums by $2,500 for the

typical family.” Moreover, Mr. Obama, the presumptive Democratic nominee, has

promised that his health plan will be in place “by the end of my first term as

president of the United States.”

Whether Mr. Obama can deliver is a matter of considerable dispute among health

analysts and economists. While there is consensus that the American health care

system is bloated with waste, eliminating enough to save $2,500 per family would

require simultaneous and synergistic solutions to a host of problems that have

proved intractable for decades.

Even if the next president and Congress can muster the political will, analysts

question whether significant savings would materialize in as little as four

years, or even in 10. But as Mr. Obama confronts an electorate that is deeply

unsettled by escalating health costs, he is offering a precise “chicken in every

pot” guarantee based on numbers that are largely unknowable. Furthermore, it is

not completely clear what he is promising.

His words about lowering “premiums” by $2,500 for the average family of four

have been fairly consistent. But the health policy advisers who formulated the

figure say it actually represents the average family’s share of savings not only

in premiums paid by individuals, but also in premiums paid by employers and in

tax-supported health programs like Medicare and Medicaid.

“What we’re trying to do,” said one of the advisers, David M. Cutler, in

explaining the gap between Mr. Obama’s words and his intent, “is find a way to

talk to people in a way they understand.”

The original arithmetic was somewhat basic. In May 2007, three Harvard

professors who are unpaid advisers to the Obama campaign — Mr. Cutler, David

Blumenthal and Jeffrey Liebman — produced a memorandum offering their “best

guess” that a menu of changes would produce savings of at least $200 billion a

year (it has since been revised to $214 billion). That would amount to about 8

percent of the $2.5 trillion in health care spending projected for 2009, when

the next president takes office.

The memorandum attributed specific savings to several broad initiatives, with

the numbers plucked from recent studies. Investments in computerized medical

records would save $77 billion a year, the advisers wrote. Reducing

administrative costs in the insurance industry would yield up to $46 billion.

Improving prevention programs and chronic disease management would be worth $81

billion.

The total savings were then divided by the country’s population, multiplied for

a family of four, and rounded down slightly to a number that was easy to grasp:

$2,500. The average cost of family coverage bought through an employer was

$12,106 in 2007, with workers paying $3,281 of that amount, according to the

Kaiser Family Foundation, a health research group.

Mr. Obama aspires to cover the country’s 47 million uninsured by requiring

insurers to accept all comers, regardless of their health status, and by

providing generous tax credits to low-income workers. The tax credits could be

used to buy into a new federal health plan or private plans marketed through a

government exchange.

The subsidies are expensive, estimated at well over $100 billion. Other

components of the Obama plan also bear up-front costs, like a pledge to spend

$50 billion over five years to speed the computerization of health records, $6

billion a year on tax credits to small businesses that provide coverage to

workers, and an unspecified amount to buffer businesses from high-cost insurance

claims.

The source Mr. Obama has identified to pay for them — the repeal of President

Bush’s tax cuts for those making more than $250,000 — would cover only about

half. That means additional health care savings would be needed, not only to

keep premiums under control but also to help pay for the subsidies.

A consensus has emerged among health economists that at least a third of the

country’s spending on health care is unnecessary. Both Mr. Obama, of Illinois,

and his Republican rival, Senator John McCain of Arizona, agree that significant

sums could be saved through reductions in unneeded procedures and improvements

in electronic record-keeping, prevention and chronic disease management.

But the dollar values Mr. Obama has attached to individual components of his

plan are beginning to attract scrutiny. In particular, the Congressional Budget

Office issued a report in May questioning the amount to be saved from the

computerization of health systems.

Mr. Obama took his estimate of $77 billion a year from a 2005 study by the RAND

Corporation (which cautioned that reductions of that magnitude would not emerge

for 15 years). The Congressional analysts found, however, that for various

methodological reasons the RAND study was “not an appropriate guide” to

potential savings.

This month, Mr. Obama’s health advisers tried to recast the debate so that the

questioning of any one number would not undermine the plan’s broader

credibility. They enlisted eight health policy experts to sign a letter that,

without endorsing the math behind any single initiative, proclaimed it was “not

only possible, but likely” that Mr. Obama could save $200 billion annually. They

did not say by when.

Mr. Cutler, who helped collect the signatures, said he and his colleagues had

decided “that our attempt to lay out one plausible scenario for the savings had

created more problems than it had solved.” He added: “Putting the debate where

this message puts it — do you believe we can save 8 percent of health spending

through a major series of public and private reforms — asks the question in a

way that is much more productive than the issue of ‘Do you believe a single

estimate among many, many studies?’ ”

Mr. Obama’s economic policy director, Jason Furman, said the campaign’s

estimates were conservative and asserted that much of the savings would come

quickly. “We think we could get to $2,500 in savings by the end of the first

term, or be very close to it,” Mr. Furman said.

The campaign won additional backing this week from Kenneth E. Thorpe of Emory

University, an authority on health care costs who helped formulate Bill

Clinton’s failed plan in 1993. In an assessment that he initiated in

coordination with the campaign, Mr. Thorpe wrote that if all of Mr. Obama’s

proposals were enacted they would reduce health spending by between $203 billion

and $273 billion by 2012. He calculated that half of the savings would accrue to

the federal government.

The Obama advisers said that while not all of the savings would translate into

lower premiums, consumers would gain in other ways. The savings to employers

would be passed along as higher wages, they predicted, and the savings to

government would eventually mean either lower taxes or added benefits.

But whether employers and governments respond that way cannot be guaranteed,

particularly in a difficult economy. And a number of health policy experts have

questioned whether the $2,500 projection is either fiscally or politically

realistic. Reducing health care costs, they emphasized, means taking money from

someone’s pocket and rationing care that Americans have come to expect, a recipe

for stiff resistance.

“There is no easy money because, as the saying goes, one person’s fraud and

abuse is another person’s income,” said Joseph R. Antos of the American

Enterprise Institute. “I wouldn’t think that four years or eight years or

probably 10 years will be enough to see numbers of that sort.”

The Commonwealth Fund, a health research group in New York, published a study in

December projecting that a robust overhaul consisting of 15 broad initiatives

would generate savings of only 6 percent after 10 years. “Doing it by the end of

a first term is ambitious and would require tough policies,” said Karen Davis,

the group’s president.

Jonathan B. Oberlander, who teaches health policy at the University of North

Carolina at Chapel Hill, called it wishful thinking. “Do they have the potential

to generate significant savings in the long run?” Dr. Oberlander asked. “Yes. Do

I believe they will produce substantial savings in the short run that can be

used to finance Obama’s plan? No.”

Health Plan From

Obama Spurs Debate, NYT, 23.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/23/us/23health.html?ref=opinion

Trial Intensifies Concerns About Safety of Vytorin

July 22, 2008

The New YorkTimes

By ALEX BERENSON

In a clinical trial, the cholesterol-lowering drug Vytorin did not help

people with heart-valve disease avoid further heart problems but did appear to

increase their risk of cancer, scientists reported Monday.

The scientists who reported on the trial, called Seas, cautioned against

panicking over the cancer findings, saying that even well-designed clinical

trials sometimes produce chance results. A review of two other, much larger

trials did not find a similar risk, they said.

Vytorin and Zetia, a companion drug, are prescribed each month to almost three

million people worldwide and are among the world’s top-selling medicines.

But other cardiologists and epidemiologists said that the cancer risk could not

be so easily dismissed.

The findings of the Seas trial will heighten concerns about Vytorin’s safety and

effectiveness, said Dr. Steven Nissen, a former president of the American

College of Cardiology and a longtime critic of Vytorin. Six months ago, a fourth

clinical trial, called Enhance, also failed to show that Vytorin benefited

patients, leading a panel of top cardiologists to recommend using Vytorin and

Zetia only as a last resort.

Since that recommendation, Vytorin and Zetia prescriptions have plunged, though

the drugs remain among the largest sellers for Merck and Schering- Plough, which

jointly sell them. The drugs had combined sales of $5 billion last year.

Shares of Merck and Schering skidded Monday after the Seas trial results were

reported, with Merck shares down 6 percent and Schering down 12 percent. After

the close of trading, both companies reported second-quarter earnings that were

slightly ahead of analysts’ estimates.

Vytorin is a single pill that combines two cholesterol-lowering medicines —

Zocor, or simvastatin, and Zetia, or ezetimibe. Both Zocor and Zetia are also

available as single pills. Zocor is a statin. Because two decades of research

have proven that statins reduce the risk of heart attacks and do not raise the

risk of cancer, the new safety concerns center around ezetimibe. In the United

States, about two million prescriptions a month are written for ezetimibe,

either independently as Zetia or in the Vytorin combination pill.

In the Seas trial, which involved nearly 1,900 patients whose heart valves were

partially blocked, participants were given either Vytorin or a placebo pill that

contained no medicine. Scientists hoped that the trial would show that patients

taking Vytorin would have a lower risk of needing valve replacement surgery or

having heart failure. But the drug did not show those benefits.

“No significant difference was observed between the treatment groups for the

combined primary endpoint,” Dr. Terje Pedersen, the principal investigator for

the study and a professor medicine at Ulleval University Hospital in Norway,

said. The primary endpoint is the result that scientists hope to prove when they

conduct a clinical trial.

However, patients taking Vytorin in the Seas trial did have a sharply higher

risk of developing and dying from cancer. In the trial 102 patients taking

Vytorin developed cancer, compared with 67 taking the placebo. Of those, 39

people taking Vytorin died from their cancer, compared with 23 taking placebo.

The absolute numbers of cancer cases were relatively small. But they reached

statistical significance, meaning the odds were less than 5 percent that they

were the result of chance.

To evaluate the cancer findings, Richard Peto, professor of medical statistics

and epidemiology at the University of Oxford, examined the interim results of

two other clinical trials of Vytorin — called Sharp and Improve-It. The

University of Oxford is leading the Sharp trial, which is sponsored by Merck and

Schering-Plough but run independently by the university’s Clinical Trial Service

Unit.

The Improve-It trial is being led by investigators by Harvard and Duke

University.

Both Sharp and Improve-It are comparing Vytorin with simvastatin — Zocor —

alone.

Neither trial has yet been completed, but the two trials combined have about

20,000 patients, nearly 10 times as many as the Seas trial.

So far, about the same number of patients taking Vytorin in Sharp and Improve-It

have developed cancer as those taking simvastatin alone, Mr. Peto said in London

on Monday. That fact strongly suggests that the finding in Seas is due to

chance, Mr. Peto said.

“I think we should not be diverted by fears of cancer,” he said.

Mr. Peto also noted that the increase in cancers was not clustered around a

single type of malignancy, but occurred widely. If ezetimibe did cause cancer,

it would be more likely to cause a single type than many types, he said.

But other doctors said the data from Improve-It and Sharp were not definitive.

The patients in those trials have generally been followed for one to two years,

while the Seas trial followed patients for four years. Because cancer generally

takes years to develop, it may take some time for Vytorin’s risks — if they are

real — to become evident in patients.

“I don’t know that you have much information about the cancer risk from the

other two trials,” said Dr. Bruce Psaty, professor of epidemiology at the

University of Washington.

In addition, the other two trials contain a puzzling finding. While the number

of cancer cases is similar in those trials among patients taking Vytorin and

those who were not, the number of cancer deaths is approximately one-third

higher among those taking Vytorin. In all, 136 people taking Vytorin have died

of cancer in the three trials, compared with 95 taking other medicines or a

sugar placebo pill.

Dr. Rob Califf, the director of the Duke Translational Medicine Institute and

the co-chairman of Improve-It, the largest of the clinical trials examining

Vytorin, said that stopping the trials early would be a mistake, since there was

no proof that ezetimibe — either in the form of Vytorin or Zetia — caused

cancer.

“To accept nonevidence as evidence is a worse mistake than to finish the trial

and get the data one way or the other,” Dr. Califf said. However, patients

outside the trials, who can choose to take other cholesterol-lowering drugs,

should discuss the findings with their doctors, he said. In general, patients

who can tolerate statins should take them and not ezetimibe, he said.

Trial Intensifies

Concerns About Safety of Vytorin, NYT, 22.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/22/business/22drug.html

Trying to Save by Increasing Doctors’ Fees

July 21, 2008

The New York Times

By MILT FREUDENHEIM

Cutting health costs by paying doctors more?

That is the premise of experiments under way by federal and state government

agencies and many insurers around the country. The idea is that by paying family

physicians, internists and pediatricians to devote more time and attention to

their patients, insurers and patients can save thousands of dollars downstream

on unnecessary tests, visits to expensive specialists and avoidable trips to the

hospital.

Nationally, Medicare and commercial insurers pay an average of only about $60 a

visit to the office of a primary-care doctor and rarely if ever pay for

telephone or e-mail consultations. Many health policy experts say the payments

are not enough to let the doctors spend more than a few minutes with each

patient.

Robert Williamson, a 60-year-old Philadelphia man, recalls the cursory exam he

received a few years ago from a harried doctor who, Mr. Williamson says, missed

the danger signals and sent him home. A short time later Mr. Williamson had a

stroke.

For want of a careful examination by a primary-care doctor, Mr. Williamson

became one of countless Americans each year whose unidentified or under-treated

illnesses escalate into medical conditions with catastrophic personal and

economic costs. Besides incurring $30,000 in hospital bills paid by his

employer’s insurer, Mr. Williamson had to stop working as a customer service

representative at Philadelphia Gas Works and go on Social Security disability,

at a current cost to taxpayers of $1,900 a month.

With Mr. Williamson’s new doctor, such an outcome would be much less likely.

“I give him my heart and diabetes readings by e-mail and phone, without getting

up out of my chair,” Mr. Williamson said. “I can get better directions, at the

very moment I need them. It’s life-saving.”

His current internist, Richard Baron, is one of more than 100 physicians in

metropolitan Philadelphia taking part in the experiment, which is being

conducted jointly by some of the region’s largest insurers. Dr. Baron still gets

a fee of only about $64 for each office visit. But his five-doctor group will

also receive $200,000 to $300,000 this year beyond their regular fees to keep

better track of their 8,400 patients.

“We are trying to do more e-mail care and telephone care, which we haven’t been

paid for in the past,” Dr. Baron said.

Insurers are conducting similar pilot projects in at least a half-dozen states,

in experiments involving thousands of doctors and nearly 2 million patients.

Many more are in the planning stages, at the urging of health policy experts and

employers that provide medical benefits.

The big government health care programs, Medicaid and Medicare, are also

studying the concept. A Medicaid experiment already under way in North Carolina

saved the government program in that state about $162 million in 2006. That was

11 percent less than the state would have spent under the old system of

reimbursement, according to an audit by Mercer, a consulting firm.

Earlier this month, as part of a bill to protect Medicare payments to doctors,

the Senate overrode President Bush’s veto to authorize $100 million to finance a

three-year Medicare pilot to further test the concept of spending more on

primary care.

Under the various payment experiments, family doctors are encouraged to hire

additional staff to help monitor patients’ treatment and follow-up, and to help

patients stay ahead of problems by sending reminders when they are due for

preventive tests like mammograms and colon exams.

For people like Mr. Williamson with serious chronic illnesses, the doctors take

personal charge, answering patients’ phone or e-mail questions promptly. In

emergencies, patients can show up at the office and see their doctors on short

notice.

Such features add up to a model of primary care that proponents refer to as

providing people with a “medical home” — a base where doctors, staff and

patients pull together as one big health-care family. Or at least that is the

ideal.

“It’s the latest new, new thing — testing whether medical homes can be a vehicle

for pulling America upwards from the grossly inefficient swamp in which our

health system is currently mired,” said Dr. Arnold Milstein, a senior consultant

at Mercer who is also member of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, an

independent Congressional agency.

The panel has recommended that Medicare expand its plans for a medical-home

pilot project next year that is expected to pay primary-care doctors in eight

states $30 to $40 a month extra for each person enrolled with a chronic illness.

In Michigan, the auto industry has been a major force behind one of the largest

medical-home projects yet devised. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, which has

4.7 million members, plans to spend $30 million this year to help primary-care

doctors offer such services. About 4,900 primary-care doctors are participating,

said Dr. Thomas Simmer, chief medical officer of Michigan Blue Cross.

Advocates of the approach hope it will attract more doctors to primary care.

Last year only 7 percent of medical school graduates chose family practice, a

field with a median income of $150,000, according to the American Academy of

Family Physicians. That compares with $406,000 for gastroenterologists and

$433,00 for cardiac surgeons, as measured by the Medical Group Management

Association.

The American Medical Association said that in its latest count, in 2006, there

were slightly more than 251,000 practicing family physicians, general,

practitioners, and internists in this country, compared with nearly 472,000

specialists.

“The pipeline of primary-care doctors has been running dry for several years,”

said Dr. Barbara Starfield, a health policy expert at Johns Hopkins University.

Many parts of the country do not meet the generally accepted standard of one

primary-care doctor for every 1,000 to 2,000 people, Dr. Starfield said.

The Philadelphia pilot project is sponsored by three of the area’s largest

insurers — Independence Blue Cross, Aetna and Cigna — as well as some local

providers of Medicaid services, which together have agreed to spend $13 million

on the program over the next three years.

Dr. Baron expects the project to add as much 15 percent to the annual revenue of

his medical group. He declined to specify the practice’s total gross income last

year, but said that each of the five physicians earned less than the $177,000

national median for internists.

To participate in the Philadelphia experiment, doctors must arrange for their

offices to keep in close communication with their entire rosters of patients.

Dr. Baron’s practice, besides the physicians, a business manager and clerical

assistants, has added a patient educator, whom he said would cost $60,000 in

salary plus $60,000 more for benefits and supporting technology. The group is

also spending $25,000 for part-time services of a data analyst.

Employers predict that better early care will reduce their health costs in the

long run. “We want to buy our care this way, we think it’s the right thing to

do,” said Dr. Paul Grundy, I.B.M.’s director of health care technology and

strategic initiatives.

Despite the hopes riding on the pilot projects, some experts are skeptical.

“There is very little concrete rigorous evidence that the medical home will do

all those wonderful things they want it to do,” said Mark Pauly, a health policy

economist at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

Even executives at Aetna and Cigna are cautious about betting on a payoff from

the Philadelphia project, which was orchestrated by Pennsylvania’s Democratic

Governor Edward G. Rendell and his office of health care reform.

It is uncertain whether there will be a direct return on the investment within a

“reasonable time horizon,” said Dr. Don Liss, an Aetna medical director who is

an internist himself. Still, Dr. Liss added, “a reasonable body of evidence

suggests that improving primary care as a foundation for health care will

improve quality and access to care.”

The Pennsylvania program will start expanding to other parts of the state this

fall. It comes none too soon, in the view of Dr. Joseph Mambu, a family

physician in Lower Gwynedd, a Philadelphia suburb. Trying to build a

medical-home practice before the pilot project began, Dr. Mambu said he went

into debt installing an electronic medical records system and establishing

patient-friendly features like evening and Saturday office hours.

“Last year, I hit the red ink because of all the technology,” he said. “Unless

we get help from the insurance companies and the government, the system is going

down the toilet.”

But with the new medical-home money, Dr. Mambu said he expected to pay down his

debts and start a patient wellness program. The insurance pilot project, he

said, offers “a ray of hope.”

Trying to Save by

Increasing Doctors’ Fees, NYT, 21.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/21/business/21medhome.html?hp

While the U.S. Spends Heavily on Health Care, a Study Faults the Quality

July 17, 2008

The New York Times

By REED ABELSON

American medical care may be the most expensive in the world, but that does

not mean it is worth every penny. A study to be released Thursday highlights the

stark contrast between what the United States spends on its health system and

the quality of care it delivers, especially when compared with many other

industrialized nations.

The report, the second national scorecard from this influential health policy

research group, shows that the United States spends more than twice as much on

each person for health care as most other industrialized countries. But it has

fallen to last place among those countries in preventing deaths through use of

timely and effective medical care, according to the report by the Commonwealth

Fund, a nonprofit research group in New York.

Access to care in the United States has worsened since the fund’s first report

card in 2006 as more people — some 75 million — are believed to lack adequate

health insurance or are uninsured altogether. And within the nation, the report

found, the cost and quality of care vary drastically.

The findings are likely to provide supporting evidence for the political notion

that the nation’s health care system needs to be fixed. Both presumptive

presidential nominees, Senator John McCain and Senator Barack Obama, argue that

the country needs to get more value for its health care money, even if they do

not agree on what changes would be most effective. But few people these days

defend the status quo.

“It’s harder to keep deluding yourself or be complacent that we don’t have areas

that need improvement,” said Karen Davis, president of the Commonwealth Fund.

The study, which assesses the United States on 37 health care measures, finds

little improvement since the last report, as the cost of health care continues

to rise steadily and more people — even those with insurance — struggle to pay

their medical bills.

“The central finding is that access has deteriorated,” Ms. Davis said.

Even some experts who are quick to point to some of the country’s medical

successes, as in reducing the deaths from heart disease or childhood cancers,

for example, also acknowledge the need for change.

“We need to generate better value in this country,” said Dr. Denis A. Cortese,

the chief executive of the Mayo Clinic.

In some cases, the nation’s progress was overshadowed by improvements in other

industrialized countries, which typically have more centralized health systems,

which makes it easier to put changes in place.

The United States, for example, has reduced the number of preventable deaths for

people under the age of 75 to 110 deaths for every 100,000 people, compared with

115 deaths five years earlier, but other countries have made greater strides. As

a result, the United States now ranks last in preventable mortality, just below

Ireland and Portugal, according to the Commonwealth Fund’s analysis of World

Health Organization data. The leader by that measure is France, followed by

Japan and Australia.

Other countries worked hard to improve, according to the Commonwealth Fund

researchers. Britain, for example, focused on steps like improving the

performance of individual hospitals that had been the least successful in

treating heart disease. The success is related to “really making a government

priority to get top-quality care,” Ms. Davis said.

The presidential candidates both emphasize the need to shift the country’s

health priorities, to provide more medical care that helps prevent people from

developing disease and that helps control conditions before they become

expensive and hard to treat. And the mounting evidence indicates that such

issues are not simply political talking points, said Len Nichols, a health

economist at New America Foundation, a nonprofit group in Washington that

advocates universal health care coverage.

More hospital executives and doctors understand their performance could be

better, Mr. Nichols said.

Dr. James J. Mongan, the chief executive of Partners HealthCare System, a big

medical network in Boston, agrees that “there’s substantial room for

improvement.” Dr. Mongan is one of several health care leaders who is working

with the Commonwealth Fund to develop a model for a better system.

Business leaders also see a pressing need for health care changes, said Helen

Darling, the president of the National Business Group on Health, which

represents big employers that provide medical benefits to their workers. The

report “documents that it’s been as bad as we have been thinking it is,” she

said.

But Ms. Darling and others were also heartened because some areas in the report

said that the United States had shown marked improvement, including the

measurements hospitals use to track how well they treated conditions like heart

failure and pneumonia.

“It proves once again if you have quantitative information and metrics and make

people pay attention, they change,” Ms. Darling said.

But the report also emphasizes the inefficiencies of the American health care

system. The administrative costs of the medical insurance system consume much

more of the current health care dollar, about 7.5 percent, than in other

countries.

Bringing those administrative costs down to the level of 5 percent or so as in

Germany and Switzerland, where private insurers play a significant role, would

save an estimated $50 billion a year in the United States, Ms. Davis said.

“It kind of dwarfs everything else you can do,” she said.

Much of the high costs are attributed to the lack of computerized systems that

may link pharmacies and doctors’ offices for filling prescriptions, for example,

or that may enable insurers to more efficiently pay doctors’ bills.

“An awful lot of the waste in this system is the antiquity of the information

technology,” Ms. Darling said.

Karen Ignagni, the chief executive of America’s Health Insurance Plans, an

industry trade group, argues that much of the higher administrative costs stem

from the additional services provided by United States insurers, like disease

management programs, and the burdensome regulatory and compliance costs of doing

business in 50 states. A more uniform system could result in savings, she said.

While the U.S. Spends

Heavily on Health Care, a Study Faults the Quality, NYT, 17.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/17/business/17health.html

Op-Ed Columnist

The Luxurious Growth

July 15, 2008

The New York Times

By DAVID BROOKS

We all know the story of Dr. Frankenstein, the scientist so caught up in his

own research that he arrogantly tried to create new life and a new man. Today,

if you look at people who study how genetics shape human behavior, you find a

collection of anti-Frankensteins. As the research moves along, the scientists

grow more modest about what we are close to knowing and achieving.

It wasn’t long ago that headlines were blaring about the discovery of an

aggression gene, a happiness gene or a depression gene. The implication was

obvious: We’re beginning to understand the wellsprings of human behavior, and it

won’t be long before we can begin to intervene to enhance or transform human

life.

Few talk that way now. There seems to be a general feeling, as a Hastings Center

working group put it, that “behavioral genetics will never explain as much of

human behavior as was once promised.”

Studies designed to link specific genes to behavior have failed to find anything

larger than very small associations. It’s now clear that one gene almost never

leads to one trait. Instead, a specific trait may be the result of the interplay

of hundreds of different genes interacting with an infinitude of environmental

factors.

First, there is the complexity of the genetic process. As Jim J. Manzi pointed

out in a recent essay in National Review, if a trait like aggressiveness is

influenced by just 100 genes, and each of those genes can be turned on or off,

then there are a trillion trillion possible combinations of these gene states.

Second, because genes respond to environmental signals, there’s the complexity

of the world around. Prof. Eric Turkheimer of the University of Virginia,

conducted research showing that growing up in an impoverished environment harms

I.Q. He was asked what specific interventions would help children realize their

potential. But, he noted, that he had no good reply. Poverty as a whole has this

important impact on people, but when you try to dissect poverty and find out

which specific elements have the biggest impact, you find that no single factor

really explains very much. It’s possible to detect the total outcome of a

general situation. It’s harder to draw a linear relationship showing cause and

effect.

Third, there is the fuzziness of the words we use to describe ourselves. We talk

about depression, anxiety and happiness, but it’s not clear how the words that

we use to describe what we feel correspond to biological processes. It could be

that we use one word, depression, to describe many different things, or perhaps

depression is merely a symptom of deeper processes that we’re not aware of. In

the current issue of Nature, there is an essay about the arguments between

geneticists and neuroscientists as they try to figure out exactly what it is

that they are talking about.

The bottom line is this: For a time, it seemed as if we were about to use the

bright beam of science to illuminate the murky world of human action. Instead,

as Turkheimer writes in his chapter in the book, “Wrestling With Behavioral

Genetics,” science finds itself enmeshed with social science and the humanities

in what researchers call the Gloomy Prospect, the ineffable mystery of why

people do what they do.

The prospect may be gloomy for those who seek to understand human behavior, but

the flip side is the reminder that each of us is a Luxurious Growth. Our lives

are not determined by uniform processes. Instead, human behavior is complex,

nonlinear and unpredictable. The Brave New World is far away. Novels and history

can still produce insights into human behavior that science can’t match.

Just as important is the implication for politics. Starting in the late 19th

century, eugenicists used primitive ideas about genetics to try to re-engineer

the human race. In the 20th century, communists used primitive ideas about

“scientific materialism” to try to re-engineer a New Soviet Man.

Today, we have access to our own genetic recipe. But we seem not to be falling

into the arrogant temptation — to try to re-engineer society on the basis of

what we think we know. Saying farewell to the sort of horrible social

engineering projects that dominated the 20th century is a major example of human

progress.

We can strive to eliminate that multivariate thing we call poverty. We can take

people out of environments that (somehow) produce bad outcomes and try to

immerse them into environments that (somehow) produce better ones. But we’re not

close to understanding how A leads to B, and probably never will be.

This age of tremendous scientific achievement has underlined an ancient

philosophic truth — that there are severe limits to what we know and can know;

that the best political actions are incremental, respectful toward accumulated

practice and more attuned to particular circumstances than universal laws.

Bob Herbert is off today.

The Luxurious Growth,

NYT, 15.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/15/opinion/15brooks.html?ref=opinion

Individual health policies leave many behind

16 July 2008

USA Today

By Julie Appleby

Soon after a pediatrician noted in his medical records that 5-year-old Logan

Swaim was short for his age, his mother, Theresa, tried to buy health insurance.

Her husband, William, had started his own landscaping business after being

laid off, and the insurance he got from his former employer was about to expire.

Two insurers accepted the Swaims and three of their children for new coverage,

but they rejected Logan, fearing his height — 40½ inches — might indicate a

glandular problem that could be expensive to treat.

For two years, the Swaims paid all of Logan's medical bills themselves, about

$4,300. Eventually they got test results showing there was nothing wrong with

him. Even so, the insurers wouldn't cover him, Theresa Swaim says, because the

time to appeal the denial of coverage had expired.

Like the Swaims, nearly 18 million people nationwide buy their own insurance

because they're self-employed, are students or have jobs that don't offer

coverage. The so-called individual health insurance market works well for some,

but as the Swaims' case shows, it is fraught with complexities for many others.

Unlike group plans offered by employers — which provide coverage to everyone, no

matter how sick — there is no guarantee in most states that individuals can get

insurance. Even if they can, their policies may not cover existing medical

conditions such as hay fever, depression or pregnancy.

Fixing the problems in the individual market could go a long way toward

expanding health coverage in America, where 47 million people are uninsured.

State and federal lawmakers — and the presidential candidates — propose changes

that could reshape that market. One approach would loosen regulations, which

could prompt insurers to offer a wider range of plans to more people. The other

would increase government oversight to make it easier for people with health

conditions to get coverage.

Among recent developments:

• In the past few months, regulators in California, Connecticut and several

other states have fined or taken other action against insurers who revoked

individual coverage after policyholders fell ill, leaving them with thousands of

dollars in unpaid medical bills.

• In Congress, Sens. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., and Bob Bennett, R-Utah, are pushing the

first sweeping, bipartisan health care proposal in years, one that could shift

many workers from getting coverage through employers to buying their own

insurance. Breaking the link between employment and insurance, they say, would

let people keep their coverage when they lose or switch jobs. The proposal

requires everyone to have coverage and forces insurers to sell to all

applicants.

• Both presidential candidates say they want to improve options for people who

buy their own coverage. Democrat Barack Obama says he would create ways for

individuals to buy insurance in groups and would require insurers to sell to

everyone.

That would allow "individuals and small firms to get all the benefits of the

purchasing power of big firms," Obama adviser David Cutler says.

Republican John McCain has made individuals the centerpiece of his health plan.

He proposes $2,500 to $5,000 tax credits to all Americans to purchase their own

coverage and would end the tax breaks workers get for job-based coverage.

McCain says that would even the playing field between those who get coverage at

work and those who buy their own.

Yet even as McCain's advisers advocate expanding the individual market, they

acknowledge the current system is broken.

"The (individual market) right now is not very good," Douglas Holtz-Eakin,

senior policy adviser to McCain, said at a forum in May exploring challenges for

individuals in getting and paying for coverage.

"I don't want to give the impression that the individual or small group market

is a good place to be," Holtz-Eakin said. "It's not. The idea is to create a

better one."

In the current market, insurers selling individual policies try to pick the

healthiest applicants to lower their risks. In most states, insurers can

consider an applicant's health history in deciding whether to offer coverage and

how much to charge.

Insurers "will not cover the sick if they can avoid them," says Len Nichols, an

economist with the New America Foundation, a centrist think tank.

Nichols and other experts say limits on who can get coverage is one of at least

three major problems with the individual market that must be addressed.

The other two are cost and coverage: Is the policy affordable? And will it pay

for what's needed when you get sick?

1. Can you get coverage?

The problem: People who have health problems may be unable to get coverage in

the individual market.

Even if they can, insurers may choose not to cover applicants' "pre-existing"

medical conditions. Excluded conditions vary by insurer.

In a 2001 study by Karen Pollitz of the Georgetown Health Policy Institute,

researchers submitted applications to 19 insurers on behalf of seven fictitious

applicants, who had medical conditions ranging from HIV to allergies. Of 420

applications, 37% were rejected.

"What we have shown is there are carriers who will turn you down if you have hay

fever," Pollitz says.

Insurers say the market isn't all that tough.

A December report by America's Health Insurance Plans, the industry's lobbying

group, examined nearly 1.9 million individual applications. About 18.5% were