|

History > 2008 > USA > Terrorism (IV)

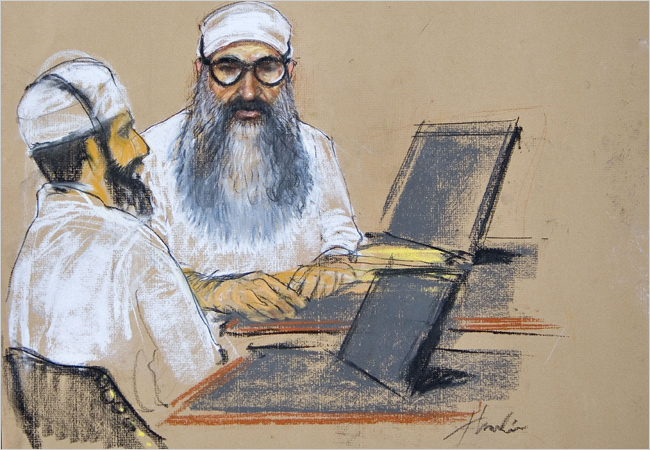

Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, right,

and Walid bin Attash

at their

arraignment

on Thursday in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.

Pool courtroom sketch

by Janet Hamlin

Arraigned, 9/11 Defendants Talk of Martyrdom

NYT

6.6.2008

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/06/washington/06gitmo.html

Op-Ed Contributor

Fight Terror With YouTube

June 26, 2008

The New York Times

By DANIEL KIMMAGE

Baku, Azerbaijan

AL QAEDA made its name in blood and pixels, with deadly attacks and an avalanche

of electronic news media. Recent news articles depict an online terrorist

juggernaut that has defied the best efforts by the United States government to

counter it. While these articles are themselves a testimony to Al Qaeda’s media

savvy, they don’t tell the whole story.

When it comes to user-generated content and interactivity, Al Qaeda is now

behind the curve. And the United States can help to keep it there by encouraging

the growth of freer, more empowered online communities, especially in the

Arab-Islamic world.

The genius of Al Qaeda was to combine real-world mayhem with virtual marketing.

The group’s guerrilla media network supports a family of brands, from Al Qaeda

in the Islamic Maghreb (in Algeria and Morocco) to the Islamic State of Iraq,

through a daily stream of online media products that would make any corporation

jealous.

A recent report I wrote for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty details this flow.

In July 2007, for example, Al Qaeda released more than 450 statements, books,

articles, magazines, audio recordings, short videos of attacks and longer films.

These products reach the world through a network of quasi-official online

production and distribution entities, like Al Sahab, which releases statements

by Osama bin Laden.

But the Qaeda media nexus, as advanced as it is, is old hat. If Web 1.0 was

about creating the snazziest official Web resources and Web 2.0 is about letting

users run wild with self-created content and interactivity, Al Qaeda and its

affiliates are stuck in 1.0.

In late 2006, with YouTube and Facebook growing rapidly, a position paper by a

Qaeda-affiliated institute discouraged media jihadists from overly “exuberant”

efforts on behalf of the group for fear of diluting its message.

This is probably sound advice, considering how Al Qaeda fares on YouTube. A

recent list of the most viewed YouTube videos in Arabic about Al Qaeda included

a rehash of an Islamic State of Iraq clip with sardonic commentary added and

satirical verses about Al Qaeda by an Iraqi poet.

Statements by Mr. bin Laden and his chief deputy, Ayman al-Zawahri, that are

posted to YouTube do draw comments aplenty. But the reactions, which range from

praise to blanket condemnation, are a far cry from the invariably positive

feedback Al Qaeda gets on moderated jihadist forums. And even Al Qaeda’s biggest

YouTube hits attract at most a small fraction of the millions of views that

clips of Arab pop stars rack up routinely.

Other Qaeda ventures into interactivity are equally unimpressive. Mr. Zawahri

solicited online questions last December, but his answers didn’t appear until

early April. That’s eons in Web time.

Even if security concerns dictated the delay, as Mr. Zawahri claimed, this is

further evidence of the online obstacles facing the world’s most-wanted

fugitives. Try to imagine Osama bin Laden managing his Facebook account, and you

can see why full-scale social networking might not be Al Qaeda’s next frontier.

It’s also an indication of how a more interactive, empowered online community,

particularly in the Arab-Islamic world, may prove to be Al Qaeda’s Achilles’

heel. Anonymity and accessibility, the hallmarks of Web 1.0, provided an ideal

platform for Al Qaeda’s radical demagoguery. Social networking, the emerging

hallmark of Web 2.0, can unite a fragmented silent majority and help it to find

its voice in the face of thuggish opponents, whether they are repressive rulers

or extremist Islamic movements.

Unfortunately, the authoritarian governments of the Middle East are doing their

best to hobble Web 2.0. By blocking the Internet, they are leaving the field

open to Al Qaeda and its recruiters. The American military’s statistics and

jihadists’ own online postings show that among the most common countries of

origin for foreign fighters in Iraq are Egypt, Libya, Saudi Arabia, Syria and

Yemen. It’s no coincidence that Reporters Without Borders lists Egypt, Saudi

Arabia and Syria as “Internet enemies,” and Libya and Yemen as countries where

the Web is “under surveillance.” There is a simple lesson here: unfettered

access to a free Internet is not merely a goal to which we should aspire on

principle, but also a very practical means of countering Al Qaeda. As users

increasingly make themselves heard, the ensuing chaos will not be to everyone’s

liking, but it may shake the online edifice of Al Qaeda’s totalitarian ideology.

It would be premature to declare Al Qaeda’s marketing strategy hopelessly

anachronistic. The group has shown remarkable resilience and will find ways to

adapt to new trends.

But Al Qaeda’s online media network is also vulnerable to disruption.

Technology-literate intelligence services that understand how the Qaeda media

nexus works will do some of the job. The most damaging disruptions to the nexus,

however, will come from millions of ordinary users in the communities that Al

Qaeda aims for with its propaganda. We should do everything we can to empower

them.

Daniel Kimmage is a senior analyst at Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

Fight Terror With

YouTube, NYT, 26.6.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/26/opinion/26kimmage.html

Inside a 9/11

Mastermind’s Interrogation

June 22, 2008

The New York Times

By SCOTT SHANE

WASHINGTON — In a makeshift prison in the north of Poland, Al Qaeda’s

engineer of mass murder faced off against his Central Intelligence Agency

interrogator. It was 18 months after the 9/11 attacks, and the invasion of Iraq

was giving Muslim extremists new motives for havoc. If anyone knew about the

next plot, it was Khalid Shaikh Mohammed.

The interrogator, Deuce Martinez, a soft-spoken analyst who spoke no Arabic, had

turned down a C.I.A. offer to be trained in waterboarding. He chose to leave the

infliction of pain and panic to others, the gung-ho paramilitary types whom the

more cerebral interrogators called “knuckledraggers.”

Mr. Martinez came in after the rough stuff, the ultimate good cop with the

classic skills: an unimposing presence, inexhaustible patience and a willingness

to listen to the gripes and musings of a pitiless killer in rambling, imperfect

English. He achieved a rapport with Mr. Mohammed that astonished his fellow

C.I.A. officers.

A canny opponent, Mr. Mohammed mixed disinformation and braggadocio with details

of plots, past and planned. Eventually, he grew loquacious. “They’d have long

talks about religion,” comparing notes on Islam and Mr. Martinez’s Catholicism,

one C.I.A. officer recalled. And, the officer added, there was one other detail

no one could have predicted: “He wrote poems to Deuce’s wife.”

Mr. Martinez, who by then had interrogated at least three other high-level

prisoners, would bring Mr. Mohammed snacks, usually dates. He would listen to

Mr. Mohammed’s despair over the likelihood that he would never see his children

again and to his catalog of complaints about his accommodations.

“He wanted a view,” the C.I.A. officer recalled.

The story of Mr. Martinez’s role in the C.I.A.’s interrogation program,

including his contribution to the first capture of a major figure in Al Qaeda,

provides the closest look to date beneath the blanket of secrecy that hides the

program from terrorists and from critics who accuse the agency of torture.

Beyond the interrogator’s successes, this account includes new details on the

campaign against Al Qaeda, including the text message that led to Mr. Mohammed’s

capture, the reason the C.I.A. believed his claim that he was the murderer of

the Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl and the separate teams at the

C.I.A.’s secret prisons of those who meted out the agony and those who asked the

questions.

In the Hollywood cliché of Fox’s “24,” a torturer shouts questions at a bound

terrorist while inflicting excruciating pain. The C.I.A. program worked

differently. A paramilitary team put on the pressure, using cold temperatures,

sleeplessness, pain and fear to force a prisoner to talk. When the prisoner

signaled assent, the tormenters stepped aside. After a break that could be a day

or even longer, Mr. Martinez or another interrogator took up the questioning.

Mr. Martinez’s success at building a rapport with the most ruthless of

terrorists goes to the heart of the interrogation debate. Did it suggest that

traditional methods alone might have obtained the same information or more? Or

did Mr. Mohammed talk so expansively because he feared more of the brutal

treatment he had already endured?

A definitive answer is unlikely under the Bush administration, which has

insisted in court that not a single page of 7,000 documents on the program can

be made public. The C.I.A. declined to provide information for this article, in

part, a spokesman said, because the agency did not want to interfere with the

military trials planned for Mr. Mohammed and four other Qaeda suspects at

Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.

The two dozen current and former American and foreign intelligence officials

interviewed for this article offered a tantalizing but incomplete description of

the C.I.A. detention program. Most would speak of the highly classified program

only on the condition of anonymity.

Mr. Martinez declined to be interviewed; his role was described by colleagues.

Gen. Michael V. Hayden, director of the C.I.A., and a lawyer representing Mr.

Martinez asked that he not be named in this article, saying that the former

interrogator believed that the use of his name would invade his privacy and

might jeopardize his safety. The New York Times, noting that Mr. Martinez had

never worked undercover and that others involved in the campaign against Al

Qaeda have been named in news articles and books, declined the request. (An

editors’ note on this issue has been posted on The Times’s Web site.)

The very fact that Mr. Martinez, a career narcotics analyst who did not speak

the terrorists’ native languages and had no interrogation experience, would end

up as a crucial player captures the ad-hoc nature of the program. Officials

acknowledge that it was cobbled together under enormous pressure in 2002 by an

agency nearly devoid of expertise in detention and interrogation.

“I asked, ‘What are we going to do with these guys when we get them?’ ” recalled

A. B. Krongard, the No. 3 official at the C.I.A. from March 2001 until 2004. “I

said, ‘We’ve never run a prison. We don’t have the languages. We don’t have the

interrogators.’ ”

In its scramble, the agency made the momentous decision to use harsh methods the

United States had long condemned. With little research or reflection, it

borrowed its techniques from an American military training program modeled on

the torture repertories of the Soviet Union and other cold-war adversaries, a

lineage that would come to haunt the agency.

It located its overseas jails based largely on which foreign intelligence

officials were most accommodating and rushed to move the prisoners when word of

locations leaked. Seeking a longer-term solution, the C.I.A. spent millions to

build a high-security prison in a remote desert location, according to two

former intelligence officials. The prison, whose existence has never been

disclosed, was completed — and then apparently abandoned unused — when President

Bush decided in 2006 to move all the prisoners to Guantánamo.

By then, whether it was a result of a fear of waterboarding, the patient

trust-building mastered by Mr. Martinez or the demoralizing effects of

isolation, Mr. Mohammed and some other prisoners had become quite compliant. In

fact, according to several officials, they had become a sort of terrorist focus

group, advising their captors on their fellow extremists’ goals, ideology and

tradecraft.

Asked, for example, how he would smuggle explosives into the United States, Mr.

Mohammed told C.I.A officers that he might send a shipping container from Japan

loaded with personal computers, half of them packed with bomb materials,

according to a foreign official briefed on the episode.

“It was to understand the mind of a terrorist — how a terrorist would do certain

things,” the foreign official said of the discussions of hypothetical attacks.

Thus did the architect of 9/11 become, in effect, a counterterrorism adviser to

the American government he professed to despise.

A Break in Pakistan

When Mr. Martinez flew to Pakistan early in 2002, he was joining an increasingly

desperate campaign to catch and question anyone who might know the plans for the

next terrorist attack.

Months had passed since Sept. 11, 2001, without a single senior Qaeda figure

being taken alive. Intelligence agencies were alarmed by the eavesdropping

“chatter” about threats. But without a high-level terrorist in custody, the

government had few sources to warn of plots in progress.

Then, in February 2002, the C.I.A. station in Islamabad, Pakistan, learned that

Abu Zubaydah, Al Qaeda’s logistics specialist, was in Lahore or Faisalabad,

Pakistani cities 80 miles apart with a combined population of more than 10

million. The hunt for the terrorist’s electronic trail grew intensive.

Armed with Abu Zubaydah’s cellphone number, eavesdropping specialists deployed

what some called the “magic box,” an electronic scanner that could track any

switched-on mobile phone and give its approximate location. But Abu Zubaydah was

careful about security: he turned his phone on only briefly to collect messages,

not long enough for his trackers to get a fix on his whereabouts.

That was when Mr. Martinez arrived, beginning what would be an unlikely

engagement with the world’s worst terrorists.

The son of a C.I.A. technician who worked on the agency’s secret communications

and eventually became a senior executive, Mr. Martinez grew up in Virginia,

majored in political science at James Madison University and went directly into

the C.I.A. training program not long before his father retired. He wound up in

the agency’s Counternarcotics Center, learning to sift masses of phone numbers,

travel records, credit card transactions and more to search for people.

“Deuce had a reputation as one of those eggheads who could sit down with a lot

of data and make sense out of it,” said one former C.I.A. officer who knew him

well. In the agency’s great cultural divide, he was a stay-at-home analyst, not

an “operator,” one of the glamorous spies who recruited foreign agents overseas.

His tool was the computer, and until the earthquake of 9/11 his expertise was

drug cartels, not terrorist networks.

After the attacks, officials recognized that tracking drug lords was not so

different from searching for terrorist masterminds, and Mr. Martinez was among a

half dozen or so narcotics analysts moved to the Counterterrorist Center to

become “targeting officers” in the hunt for Al Qaeda.

Colleagues say Mr. Martinez, then 36, threw himself into the new work with a

passion. On a wall at the American Embassy in Islamabad, he posted a large,

blank piece of paper. He wrote Abu Zubaydah’s phone number at the center. Then,

over a week or so, he and others added more and more linked phone numbers from

the eavesdropping files of the National Security Agency and Pakistani

intelligence. They excluded known institutions like mosques and shops and

gradually built a map of the network of contacts around Abu Zubaydah.

“It was a spider’s web,” said one person who saw the telephone chart.

“Aesthetically it was quite pretty.”

Using the numbers, and premises linked to them, Mr. Martinez and his colleagues

sought to identify Abu Zubaydah’s most likely hide-outs. They could not reduce

the list to fewer than 14 addresses in Lahore and Faisalabad, which they put

under surveillance. At 2 a.m. on March 28, 2002, teams led by Pakistan’s Punjab

Elite Force, with Americans waiting outside, hit the locations all at once.

One of the SWAT teams found Abu Zubaydah, protected by Syrian and Egyptian

bodyguards, at a handsome house on Canal Road in Faisalabad. It held bomb-making

equipment and a safe loaded with $100,000 in cash, according to a terrorism

consultant briefed on the event. Photographs of the raid reviewed by The Times

last month showed Abu Zubaydah, a cleanshaven 30-year-old Palestinian, shot

three times during the raid, lying face down in the back of a Toyota pickup

before he was taken to a hospital.

At first, Abu Zubaydah fell in and out of consciousness, emerging occasionally

to speak incoherently — once, evidently imagining himself in a restaurant,

ordering a glass of red wine, a C.I.A. official said. The agency, desperate to

keep him alive, flew in a Johns Hopkins Hospital surgeon to consult. Within a

few days, Abu Zubaydah was flown to Thailand, to the first of the “black sites,”

the agency’s interrogation facilities for major Qaeda figures.

Thailand, which had long faced Muslim insurgents in its south, became the first

choice because C.I.A. officers had a very close relationship with their

counterparts in Bangkok, according to one American intelligence official. At

first, the official said, “they didn’t even tell the prime minister.”

Inside a ‘Black Site’

It was at the Thai jail, not far from Bangkok, that Mr. Martinez first tried his

hand at interrogation on Abu Zubaydah, who refused to speak Arabic with his

captors but spoke passable English. It was also there, as previously reported,

that the C.I.A. would first try physical pressure to get information, including

the near-drowning of waterboarding. The methods came from the military’s SERE

training program, for Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape, which many of

the C.I.A.’s paramilitary officers had themselves completed. A small version of

SERE had long operated at the C.I.A.’s Virginia training site, known as The

Farm.

Senior Federal Bureau of Investigation officials thought such methods

unnecessary and unwise. Their agents got Abu Zubaydah talking without the use of

force, and he revealed the central role of Mr. Mohammed in the 9/11 plot. They

correctly predicted that harsh methods would darken the reputation of the United

States and complicate future prosecutions. Many C.I.A. officials, too, had their

doubts, and the agency used contract employees with military experience for much

of the work.

Some C.I.A. officers were torn, believing the harsh treatment could be

effective. Some said that only later did they understand the political cost of

embracing methods the country had long shunned.

John C. Kiriakou, a former C.I.A. counterterrorism officer who was the first to

question Abu Zubaydah, expressed such conflicted views when he spoke publicly to

ABC News and other news organizations late last year. In a December interview

with The Times, before being cautioned by the C.I.A. not to discuss classified

matters, Mr. Kiriakou, who was not present for the waterboarding but read the

resulting intelligence reports, said he had been told that Abu Zubaydah became

compliant after 35 seconds of the water treatment.

“It was like flipping a switch,” Mr. Kiriakou said of the shift from resistance

to cooperation. He said he thought such “desperate measures” were justified in

the “desperate time” in 2002 when another attack seemed imminent. But on

reflection, he said, he had concluded that waterboarding was torture and should

not be permitted. “We Americans are better than that,” he said.

With Abu Zubaydah’s case, the pattern was set. With a new prisoner, the

interrogators, like Mr. Martinez, would open the questioning. In about

two-thirds of cases, C.I.A. officials have said, no coercion was used.

If officers believed the prisoner was holding out, paramilitary officers who had

undergone a crash course in the new techniques, but who generally knew little

about Al Qaeda, would move in to manhandle the prisoner. Aware that they were on

tenuous legal ground, agency officials at headquarters insisted on approving

each new step — a night without sleep, a session of waterboarding, even a “belly

slap” — in an exchange of encrypted messages. A doctor or medic was always on

hand.

The tough treatment would halt as soon as the prisoner expressed a desire to

talk. Then the interrogator would be brought in.

Interrogation became Mr. Martinez’s new forte, first with Abu Zubaydah; then

with Ramzi bin al-Shibh, the Yemeni who was said to have been an intermediary

between the 9/11 hijackers and Qaeda leaders, caught in September 2002; and then

with Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, the Saudi accused of planning the bombing of the

American destroyer Cole in 2000, who was caught in November 2002.

Mr. bin al-Shibh quickly cooperated; Mr. Nashiri resisted and was subjected to

waterboarding, intelligence officials have said. C.I.A superiors offered Mr.

Martinez and some other analysts the chance to be “certified” in what the C.I.A.

euphemistically called “enhanced interrogation methods.”

Mr. Martinez declined, as did several other C.I.A. officers. He did not condemn

the tough methods, colleagues said, but he was learning that his talents lay

elsewhere.

Another Suspect Is Seized

The hunt for Khalid Shaikh Mohammed involved the entire American intelligence

establishment, with its billion-dollar arrays of spy satellites and global

eavesdropping net. But his capture came down to a simple text message sent from

an informant who had slipped into the bathroom of a house in Rawalpindi, near

the Pakistani capital, Islamabad.

“I am with K.S.M.,” the message said, according to an intelligence officer

briefed on the episode.

The capture team waited a few hours before going in on the night of March 1,

2003, to blur the connection to the informant, a walk-in attracted by the offer

of a $25 million reward. The informant, described by one American who met him as

“a little guy who looked like a farmer,” would later get a face-to-face thank

you from George J. Tenet, then the C.I.A. director, at the American Embassy in

Abu Dhabi, intelligence officials say, and he was resettled with his reward

money under a new identity in the United States.

Within days, Mr. Mohammed was flown to Afghanistan and then on to Poland, where

the most important of the C.I.A.’s black sites had been established. The secret

base near Szymany Airport, about 100 miles north of Warsaw, would become a

second home to Mr. Martinez during the dozens of hours he spent with Mr.

Mohammed.

Poland was picked because there were no local cultural and religious ties to Al

Qaeda, making infiltration or attack by sympathizers unlikely, one C.I.A.

officer said. Most important, Polish intelligence officials were eager to

cooperate.

“Poland is the 51st state,” one former C.I.A. official recalls James L. Pavitt,

then director of the agency’s clandestine service, declaring. “Americans have no

idea.”

Mr. Mohammed met his captors at first with cocky defiance, telling one veteran

C.I.A. officer, a former Pakistan station chief, that he would talk only when he

got to New York and was assigned a lawyer — the experience of his nephew and

partner in terrorism, Ramzi Yousef, after Mr. Yousef’s arrest in 1995.

But the rules had changed, and the tough treatment began shortly after Mr.

Mohammed was delivered to Poland. By several accounts, he proved especially

resistant, chanting from the Koran, doling out innocuous information or offering

obvious fabrications. The Times reported last year that the intensity of his

treatment — various harsh techniques, including waterboarding, used about 100

times over a period of two weeks — prompted worries that officers might have

crossed the boundary into illegal torture.

His cooperation came in fits and starts, and interrogators said they believed at

times that he gave them disinformation. But he talked most freely to Mr.

Martinez.

An obvious chasm separated these enemies — the interrogator and the prisoner.

But Mr. Martinez shared a few attributes with his adversary that he could

exploit as he sought his secrets. They were close in age, approaching 40; they

had attended public universities in the American South (Mr. Mohammed had studied

engineering at North Carolina A&T); they were both religious; and they were both

fathers.

Mr. Mohammed, according to one former C.I.A. officer briefed on the sessions,

“would go through these emotional cycles.”

“He’d be chatty, almost friendly,” the officer added. “He liked to debate. He

got to the stage where he’d draw parallels between Christianity and Islam and

say, ‘Can’t we get along?’ ”

By this account, Mr. Martinez would reply to the man who had overseen the

killing of nearly 3,000 people: “Isn’t it a little late for that?”

At other times, the C.I.A. officer said, Mr. Mohammed would grow depressed,

complaining about being separated from his family and ranting about his cell or

his food — a common theme for other prisoners, including Abu Zubaydah, who

protested when the flavor of his Ensure nutrition drink was changed.

Sometimes Mr. Mohammed wrote letters to the Red Cross or to President Bush with

his demands; the letters went to C.I.A. psychologists for analysis.

And there were the poetic tributes to Mr. Martinez’s wife, scribbled in Mr.

Mohammed’s ungrammatical English and intended as a show of respect for his

interrogator, according to a colleague who heard Mr. Martinez’s account.

But as time passed, Mr. Mohammed provided more and more detail on Al Qaeda’s

structure, its past plots and its aspirations. When he sometimes sought to

mislead, interrogators often took his claims immediately to other Qaeda

prisoners at the Polish compound to verify the information.

The intelligence riches ultimately gleaned from Mr. Mohammed were reflected in

the report of the national 9/11 commission, whose footnotes credit his

interrogations 60 times for facts about Al Qaeda and its plotting — while also

occasionally noting assertions by him that were “not credible.”

The interrogations the commission cited began just 11 days after Mr. Mohammed’s

capture and ended just days before the commission’s report was published in

mid-2004. Together they amount to a detailed history of Mr. Mohammed’s

initiation into terrorism along with his nephew, Mr. Yousef; his plotting of

mayhem from Bosnia to the Philippines; and his alliance with Osama bin Laden, to

whom the egotistical Mr. Mohammed was reluctant to defer.

Mr. Mohammed also claimed a role in a long list of completed and thwarted

attacks. Human rights advocates have questioned some of Mr. Mohammed’s claims,

including the beheading of Mr. Pearl, the Wall Street Journal reporter,

suggesting that they may have been false statements made to stop torture.

But Mr. Martinez told colleagues that Mr. Mohammed volunteered out of the blue

that he was the man who killed Mr. Pearl. The C.I.A. at first was skeptical,

according to two former agency officials. Intelligence analysts eventually were

convinced, however, in part because Mr. Mohammed pointed out to Mr. Martinez

details of the hand and arm of the masked killer in a videotape of the murder

that appeared to show it was him.

“He was a leader,” said a foreign counterterrorism official briefed on the

episode. “He wanted to demonstrate to his people how ruthless he could be.”

Divergent Paths

On June 5, Mr. Mohammed made a theatrical return to the public eye at his

Guantánamo Bay arraignment, with a long, graying beard and a defiant insistence

that the American military commission could do no more to him than give him his

wish: execution and martyrdom.

His interrogator has moved on, too. Like many other C.I.A. officers in the

post-9/11 security boom, Mr. Martinez left the agency for more lucrative work

with government contractors.

His life today is quiet by comparison with the secret interrogations of 2002 and

2003. But Mr. Martinez has not turned away entirely from his old world. He now

works for Mitchell & Jessen Associates, a consulting company run by former

military psychologists who advised the C.I.A. on the use of harsh tactics in the

secret program.

And his new employer sent Mr. Martinez right back to the agency. For now, the

unlikely interrogator of the man perhaps most responsible for the horrors of

9/11 teaches other C.I.A. analysts the arcane art of tracking terrorists.

Inside a 9/11

Mastermind’s Interrogation, NYT, 22.6.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/22/washington/22ksm.html?hp

Obama says bin Laden

must not be a martyr

June 18, 2008

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Filed at 3:50 p.m. ET

The New York Times

WASHINGTON (AP) -- Barack Obama says if Osama bin Laden were captured on his

watch, he'd want to ensure he doesn't become a martyr if he were prosecuted.

Obama said he's not sure that the terrorist mastermind would be captured alive.

But if he were, Obama said he would want to bring him to justice ''in a way that

allows the entire world to understand the murderous acts that he's engaged in

and not to make him into a martyr.''

Obama was asked about how he would handle bin Laden at a news conference

Wednesday after he met with a new team of national security advisers. The

meeting came after rival John McCain's campaign criticized Obama for a having a

pre-9-11 mind-set for promoting trial of terrorists.

Obama says bin Laden

must not be a martyr, NYT, 18.6.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/washington/AP-Obama-National-Security.html

Justices Rule Terror Suspects Can Appeal in Civilian Courts

June 13, 2008

The New York Times

By DAVID STOUT

WASHINGTON — Foreign terrorism suspects held at the Guantánamo Bay naval base

in Cuba have constitutional rights to challenge their detention there in United

States courts, the Supreme Court ruled, 5 to 4, on Thursday in a historic

decision on the balance between personal liberties and national security.

“The laws and Constitution are designed to survive, and remain in force, in

extraordinary times,” Justice Anthony M. Kennedy wrote for the court.

The ruling came in the latest battle between the executive branch, Congress and

the courts over how to cope with dangers to the country in the post-9/11 world.

Although there have been enough rulings addressing that issue to confuse all but

the most diligent scholars, this latest decision, in Boumediene v. Bush, No.

06-1195, may be studied for years to come.

In a harsh rebuke of the Bush administration, the justices rejected the

administration’s argument that the individual protections provided by the

Detainee Treatment Act of 2005 and the Military Commissions Act of 2006 were

more than adequate.

“The costs of delay can no longer be borne by those who are held in custody,”

Justice Kennedy wrote, assuming the pivotal role that some court-watchers had

foreseen.

The issues that were weighed in Thursday’s ruling went to the very heart of the

separation-of-powers foundation of the United States Constitution. “To hold that

the political branches may switch the Constitution on or off at will would lead

to a regime in which they, not this court, say ‘what the law is,’ ” Justice

Kennedy wrote, citing language in the 1803 ruling in Marbury v. Madison, in

which the Supreme Court articulated its power to review acts of Congress.

Joining Justice Kennedy’s opinion were Justices John Paul Stevens, Stephen G.

Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and David H. Souter. Writing separately, Justice

Souter said the dissenters did not sufficiently appreciate “the length of the

disputed imprisonments, some of the prisoners represented here today having been

locked up for six years.”

The dissenters were Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justices Samuel A.

Alito Jr., Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas, generally considered the

conservative wing on the high court.

Reflecting how the case divided the court not only on legal but, perhaps,

emotional lines, Justice Scalia said that the United States was “at war with

radical Islamists,” and that the ruling “will almost certainly cause more

Americans to get killed.”

And Chief Justice Roberts said the majority had struck down “the most generous

set of procedural protections ever afforded aliens detained by this country as

enemy combatants.”

The immediate effects of the ruling are not clear. For instance, Cmdr. Jeffrey

Gordon, a Pentagon spokesman, told The Associated Press he had no information on

whether a hearing at Guantánamo for Omar Khadr, a Canadian charged with killing

an American soldier in Afghanistan, would go forward next week, as planned. Nor

was it initially clear what effects the ruling would have beyond Guantánamo.

The 2006 Military Commission Act stripped the federal courts of jurisdiction to

hear habeas corpus petitions filed by detainees challenging the bases for their

confinement. That law was upheld by the United States Court of Appeals for the

District of Columbia Circuit in February 2007.

At issue were the “combatant status review tribunals,” made up of military

officers, that the administration set up to validate the initial determination

that a detainee deserved to be labeled an “enemy combatant.”

The military assigns a “personal representative” to each detainee, but defense

lawyers may not take part. Nor are the tribunals required to disclose to the

detainee details of the evidence or witnesses against him — rights that have

long been enjoyed by defendants in American civilian and military courts.

Under the 2005 Detainee Treatment Act, detainees may appeal decisions of the

military tribunals to the District of Columbia Circuit, but only under

circumscribed procedures, which include a presumption that the evidence before

the military tribunal was accurate and complete.

The ruling on Thursday focused in large part on the centuries old writ of habeas

corpus (“you have the body,” in Latin), a means by which prisoners can challenge

their incarceration. Noting that the Constitution provides for suspension of the

writ only in times of rebellion or invasion, Justice Kennedy called it “an

indispensable mechanism for monitoring the separation of powers.”

In the years-long debate over the treatment of detainees, some critics of

administration policy have asserted that those held at Guantánamo have fewer

rights than people accused of crimes under American civilian and military law

and that they are trapped in a sort of legal limbo.

Justice Kennedy wrote that the cases involving the detainees “lack any precise

historical parallel. They involve individuals detained by executive order for

the duration of a conflict that, if measure from September 11, 2001, to the

present, is already among the longest wars in American history.”

President Bush, traveling in Rome, did not immediately react to the court’s

decision. "People are reviewing the decision," Mr. Bush’s press secretary, Dana

M. Perino, said. The president has said he wants to close the Guantánamo

detention unit eventually.

The detainees at the center of the case decided on Thursday are not all typical

of the people confined at Guantánamo. True, the majority were captured in

Afghanistan or Pakistan. But the man who gave the case its title, Lakhdar

Boumediene, is one of six Algerians who immigrated to Bosnia in the 1990’s and

were legal residents there. They were arrested by Bosnian police within weeks of

the Sept. 11 attacks on suspicion of plotting to attack the United States

embassy in Sarajevo — “plucked from their homes, from their wives and children,”

as their lawyer, Seth P. Waxman, a former solicitor general put it in the

argument before the justices on Dec. 5.

The Supreme Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina ordered them released three months

later for lack of evidence, whereupon the Bosnian police seized them and turned

them over to the United States military, which sent them to Guantánamo.

Mr. Waxman argued before the United States Supreme Court that the six Algerians

did not fit any authorized definition of enemy combatant, and therefore ought to

be released.

The head of the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights, which

represents dozens of prisoners at Guantánamo, hailed the ruling. “The Supreme

Court has finally brought an end to one of our nation’s most egregious

injustices,” Vincent Warren, the organization’s executive director, told The

Associated Press.

Senator Barack Obama of Illinois, the presumptive Democratic presidential

nominee, has called for closing the Guantánamo detention unit. So has his

Republican opponent, Senator John McCain of Arizona, but the issue of what to do

with the detainees could still figure prominently in the campaign, as Mr.

McCain’s remarks on Thursday signaled.

Speaking to reporters in Boston on Thursday morning, Mr. McCain said he had not

had time to read the decision, but “it obviously concerns me.”

“These are unlawful combatants, they’re not American citizens, and I think that

we should pay attention to Justice Roberts’s opinion in this decision,” Mr.

McCain said. "But it is a decision the Supreme Court had made, and now we need

to move forward."

Mr. McCain, who was held for more than five years as a prisoner of war in

Vietnam, was one of the chief architects of the Military Commissions Act of

2006. He argued during the drafting of that law that it gave detainees more than

adequate provisions to challenge their detention.”

Senator John Kerry of Massachusetts, the 2004 Democratic presidential nominee,

applauded the ruling. “Today, the Supreme Court affirmed what almost everyone

but the administration and their defenders in Congress always knew,” he said.

“The Constitution and the rule of law bind all of us even in extraordinary times

of war. No one is above the Constitution.”

Kate Zernike contributed reporting from Boston.

Justices Rule Terror

Suspects Can Appeal in Civilian Courts, NYT, 13.6.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/13/washington/12cnd-gitmo.html?hp

Arraigned,

9/11 Defendants

Talk of Martyrdom

June 6,

2008

The New York Times

By WILLIAM GLABERSON

GUANTÁNAMO

BAY, Cuba — When at last he got the chance to speak, Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, the

self-proclaimed planner of the Sept. 11 attacks, on Thursday called President

Bush a crusader and ridiculed the trial system here as an inquisition.

Mr. Mohammed, the former senior operations chief for Al Qaeda, said he would

represent himself and dared the Guantánamo tribunal to put him to death.

“This is what I want,” he told a military judge here, in his first appearance to

answer war crimes charges for the terrorism attacks that killed 2,973 people and

set America on a path to war.

“I’m looking to be martyr for long time,” he said in serviceable English,

improved, perhaps, by five years of custody, including three in secret C.I.A.

prisons.

The arraignment on Thursday of Mr. Mohammed and four other detainees the

government says were high-level coordinators of the Sept. 11 attacks was the

start of hearings in the case, which is the centerpiece of the Bush

administration’s war crimes system here.

But it was also the first public appearance by Mr. Mohammed, who has long cast

himself in the role of superterrorist, claiming responsibility in the past not

only for the 2001 plot, but for some 30 others, including the murder of Daniel

Pearl, a reporter for The Wall Street Journal.

A bushy gray beard all but covered Mr. Mohammed’s face, so familiar from the

well-known photograph of him in a baggy undershirt that was taken the day of his

capture in Pakistan in 2003. On Thursday, he worked to get as much control as

possible over the proceedings.

Peering through big black-rimmed glasses, he rejected American lawyers as agents

of the Bush administration’s “crusade war against Islamic world.” He said the

lawyers could stay to help him as advisers.

He quickly staked out his position as the leader of the accused men. He gestured

to them, shared animated conversations while the proceedings droned on and, at

one point, turned his chair toward the back of the courtroom to face his

co-defendants, lined up in a row behind him.

His strategy seemed to work. One of the detainees, a military lawyer said,

decided to reject his lawyers on Thursday, after a few minutes in the courtroom.

Another, Mustafa Ahmed al-Hawsawi, was intimidated by Mr. Mohammed, said his

designated lawyer, Maj. Jon Jackson.

By day’s end, each of Mr. Mohammed’s four co-defendants had said he wanted to

represent himself. That could turn a trial into a jumble of rhetoric and a new

opportunity for critics to attack the Guantánamo system as designed to get easy

convictions.

Each of the five men remained seated when the judge asked that they rise for the

formal arraignment.

“I reject this session,” said Walid bin Attash, a detainee known as Khallad, who

investigators say selected and trained some of the hijackers. Ramzi bin

al-Shibh, who was to have been one of the hijackers, said that he too, like Mr.

Mohammed, was ready for martyrdom.

He recalled that he had “tried for 9/11” but was denied an American visa so had

missed his chance.

The judge, Col. Ralph H. Kohlmann, agreed to permit three of the men to

represent themselves. He said he wanted more information on Major Jackson’s

assertion. In Mr. Shibh’s case, he said he wanted to investigate a new report on

Thursday from a military lawyer that Mr. Shibh has been on psychotropic

medication.

When Judge Kohlmann asked Mr. Shibh why he was taking the medication, security

officials cut the sound fed to reporters in a glassed-in gallery and a satellite

press center. It was one of half a dozen times in a long court day when a

private national-security consultant to the court cut the sound when detainees

appeared to be discussing what several of them said had been years of torture.

Mr. Mohammed managed to get the reference through the censor twice.

“After torturing,” he said, warming to his subject, “they transfer us to

Inquisitionland in Guantánamo.”

Central Intelligence Agency officials have said that Mr. Mohammed was one of

three detainees subjected to the simulated drowning technique known as

waterboarding.

The sound was cut twice when Mr. Mohammed seemed to be discussing his claim.

He was far from shy, and he looked lean compared with the photograph taken of

him after his 2003 capture. He chanted verses in Arabic and then translated them

into English. He vied with Judge Kohlmann for control of the courtroom.

“Go ahead,” he told the judge from time to time when there was a pause, as if

he, at the shiny new defense table in a specially built courtroom here, and not

the man in the black robe on the bench, were in charge.

He was, Mr. Mohammed said cheerfully, unable to accept lawyers who knew little

of Islamic law. He asked that the five men facing terrorism, conspiracy and

other charges for the Sept. 11 attacks be permitted to meet. They needed, he

said, to plan “one front.”

The request for a meeting, like most requests from the defense on Thursday, was

rejected by Judge Kohlmann.

All five accused men were held in the secret C.I.A. program and transferred to

Guantánamo to face charges in the military commission system.

“Sit down,” the judge barked out a few times as defense lawyers assigned to the

cases by the military and by the American Civil Liberties Union tried to slow

the proceedings.

The lawyers said that Mr. Mohammed and the other men had not had enough

opportunity to meet with them. As a result, they said, the detainees could not

understand the implications of representing themselves with their lives

potentially on the line. No one would prevail with the argument that the

arraignment could not proceed as scheduled, Judge Kohlmann announced.

The Pentagon has been pressing to move its war crimes cases quickly after years

of delays and legal setbacks. Critics, including a former chief military

prosecutor, have said there is intense political pressure to start the trials by

the end of the Bush administration.

The Pentagon general who has become the most visible advocate of the commission

system, Thomas W. Hartmann, has repeatedly said that accelerating the filing and

prosecution of charges is not motivated by politics.

Whatever the motivation, it was clear inside the wire of the new court complex

in the bright sun here that the Guantánamo trial system had begun its most

important test. Reporters from Italy, Pakistan, Britain and Canada mixed with

Americans crowded into a press center for the first glimpse of Mr. Mohammed and

his co-defendants.

The expansive new courtroom, built specifically for the Sept. 11 case, provided

an austere setting. It is a big, windowless white room, decorated only with a

large American flag and the seals of each of the American military branches.

The reporters and a handful of observers from human rights, military and legal

groups sat in an observation room at the rear. Sound to the room was delayed 20

seconds, so people in the proceedings rose and sat on occasion before their

voices could be heard.

In the courtroom, the prosecutors sat to the right at three long tables. On the

left, there were six long tables, the final one unused. At the end of each

table, a detainee sat, in a white prison uniform. Only one, Mr. Shibh, was

shackled to the floor.

Mr. Mohammed, who is sometimes known as K.S.M., was at the first table. He could

not, he explained, work easily with lawyers trained in the American legal

system, which he described as evil. “They allow same sexual marriage,” he said,

“and many things are very bad.”

He held his own in rapid fire back-and-forth with the judge dealing with the

particulars of the proceedings, but then would retreat into another world. When

Judge Kohlmann explained the risks of going through a death penalty case without

a lawyer, Mr. Mohammed answered: “Nothing shall befall us, save what Allah has

ordained for us.”

Arraigned, 9/11 Defendants Talk of Martyrdom, NYT,

6.6.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/06/washington/06gitmo.html

US

accused of holding terror suspects on prison ships

· Report

says 17 boats used

· MPs seek details of UK role

· Europe attacks 42-day plan

Monday June

2 2008

The Guardian

Duncan Campbell and Richard Norton-Taylor

The United

States is operating "floating prisons" to house those arrested in its war on

terror, according to human rights lawyers, who claim there has been an attempt

to conceal the numbers and whereabouts of detainees.

Details of ships where detainees have been held and sites allegedly being used

in countries across the world have been compiled as the debate over detention

without trial intensifies on both sides of the Atlantic. The US government was

yesterday urged to list the names and whereabouts of all those detained.

Information about the operation of prison ships has emerged through a number of

sources, including statements from the US military, the Council of Europe and

related parliamentary bodies, and the testimonies of prisoners.

The analysis, due to be published this year by the human rights organisation

Reprieve, also claims there have been more than 200 new cases of rendition since

2006, when President George Bush declared that the practice had stopped.

It is the use of ships to detain prisoners, however, that is raising fresh

concern and demands for inquiries in Britain and the US.

According to research carried out by Reprieve, the US may have used as many as

17 ships as "floating prisons" since 2001. Detainees are interrogated aboard the

vessels and then rendered to other, often undisclosed, locations, it is claimed.

Ships that are understood to have held prisoners include the USS Bataan and USS

Peleliu. A further 15 ships are suspected of having operated around the British

territory of Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean, which has been used as a military

base by the UK and the Americans.

Reprieve will raise particular concerns over the activities of the USS Ashland

and the time it spent off Somalia in early 2007 conducting maritime security

operations in an effort to capture al-Qaida terrorists.

At this time many people were abducted by Somali, Kenyan and Ethiopian forces in

a systematic operation involving regular interrogations by individuals believed

to be members of the FBI and CIA. Ultimately more than 100 individuals were

"disappeared" to prisons in locations including Kenya, Somalia, Ethiopia,

Djibouti and Guantánamo Bay.

Reprieve believes prisoners may have also been held for interrogation on the USS

Ashland and other ships in the Gulf of Aden during this time.

The Reprieve study includes the account of a prisoner released from Guantánamo

Bay, who described a fellow inmate's story of detention on an amphibious assault

ship. "One of my fellow prisoners in Guantánamo was at sea on an American ship

with about 50 others before coming to Guantánamo ... he was in the cage next to

me. He told me that there were about 50 other people on the ship. They were all

closed off in the bottom of the ship. The prisoner commented to me that it was

like something you see on TV. The people held on the ship were beaten even more

severely than in Guantánamo."

Clive Stafford Smith, Reprieve's legal director, said: "They choose ships to try

to keep their misconduct as far as possible from the prying eyes of the media

and lawyers. We will eventually reunite these ghost prisoners with their legal

rights.

"By its own admission, the US government is currently detaining at least 26,000

people without trial in secret prisons, and information suggests up to 80,000

have been 'through the system' since 2001. The US government must show a

commitment to rights and basic humanity by immediately revealing who these

people are, where they are, and what has been done to them."

Andrew Tyrie, the Conservative MP who chairs the all-party parliamentary group

on extraordinary rendition, called for the US and UK governments to come clean

over the holding of detainees.

"Little by little, the truth is coming out on extraordinary rendition. The rest

will come, in time. Better for governments to be candid now, rather than later.

Greater transparency will provide increased confidence that President Bush's

departure from justice and the rule of law in the aftermath of September 11 is

being reversed, and can help to win back the confidence of moderate Muslim

communities, whose support is crucial in tackling dangerous extremism."

The Liberal Democrat's foreign affairs spokesman, Edward Davey, said: "If the

Bush administration is using British territories to aid and abet illegal state

abduction, it would amount to a huge breach of trust with the British

government. Ministers must make absolutely clear that they would not support

such illegal activity, either directly or indirectly."

A US navy spokesman, Commander Jeffrey Gordon, told the Guardian: "There are no

detention facilities on US navy ships." However, he added that it was a matter

of public record that some individuals had been put on ships "for a few days"

during what he called the initial days of detention. He declined to comment on

reports that US naval vessels stationed in or near Diego Garcia had been used as

"prison ships".

The Foreign Office referred to David Miliband's statement last February

admitting to MPs that, despite previous assurances to the contrary, US rendition

flights had twice landed on Diego Garcia. He said he had asked his officials to

compile a list of all flights on which rendition had been alleged.

CIA "black sites" are also believed to have operated in Thailand, Afghanistan,

Poland and Romania.

In addition, numerous prisoners have been "extraordinarily rendered" to US

allies and are alleged to have been tortured in secret prisons in countries such

as Syria, Jordan, Morocco and Egypt.

US accused of holding terror suspects on prison ships, G,

2.6.2008,

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/jun/02/usa.humanrights

States

Chafing at U.S. Focus on Terrorism

May 26,

2008

The New York Times

By ERIC SCHMITT and DAVID JOHNSTON

Juliette N.

Kayyem, the Massachusetts homeland security adviser, was in her office in early

February when an aide brought her startling news. To qualify for its full

allotment of federal money, Massachusetts had to come up with a plan to protect

the state from an almost unheard-of threat: improvised explosive devices, known

as I.E.D.’s.

“I.E.D.’s? As in Iraq I.E.D.’s?” Ms. Kayyem said in an interview, recalling her

response. No one had ever suggested homemade roadside bombs might begin

exploding on the highways of Massachusetts. “There was no new intelligence about

this,” she said. “It just came out of nowhere.”

More openly than at any time since the Sept. 11 attacks, state and local

authorities have begun to complain that the federal financing for domestic

security is being too closely tied to combating potential terrorist threats, at

a time when they say they have more urgent priorities.

“I have a healthy respect for the federal government and the importance of

keeping this nation safe,” said Col. Dean Esserman, the police chief in

Providence, R.I. “But I also live every day as a police chief in an American

city where violence every day is not foreign and is not anonymous but is right

out there in the neighborhoods.”

The demand for plans to guard against improvised explosives is being cited by

state and local officials as the latest example that their concerns are not

being heard, and that federal officials continue to push them to spend money on

a terrorism threat that is often vague. Some $23 billion in domestic security

financing has flowed to the states from the federal government since the Sept.

11 attacks, but authorities in many states and cities say they have seen little

or no intelligence that Al Qaeda, or any of its potential homegrown offshoots,

has concrete plans for an attack.

Local officials do not dismiss the terrorist threat, but many are trying to

retool counterterrorism programs so that they focus more directly on combating

gun violence, narcotics trafficking and gangs — while arguing that these

programs, too, should qualify for federal financing, on the theory that

terrorists may engage in criminal activity as a precursor to an attack.

Michael Chertoff, the Homeland Security secretary, said in an interview that his

department had tried to be flexible to accommodate local needs.

“We have not been highly restrictive,” Mr. Chertoff said. But he said the

department’s programs were never meant to assist local law enforcement agencies

in their day-to-day policing. The requirements of the Homeland Security programs

had helped strengthen the country against an attack, Mr. Chertoff said,

expressing concern about shifting money to other law enforcement problems from

counterterrorism. “If we drop the barrier and start to lose focus,” he said, “we

will make it easier to have successful attacks here.”

Local officials have long groused that Homeland Security grants seemed

mismatched with local needs and that the agency’s requirements failed to

recognize regional differences. After Hurricane Katrina struck Gulf Coast states

in 2005, federal authorities demanded that cities come up with evacuation plans,

even on the West Coast where earthquakes, not hurricanes, are a threat.

Most of the $23 billion in federal grants has been spent shoring up local

efforts to prevent, prepare for and ferret out a possible attack. Because

official post-9/11 critiques found huge gaps in communication and coordination,

billions of dollars have been spent linking federal law enforcement and

intelligence authorities to the country’s more than 750,000 police officers,

sheriffs and highway patrol officers. Many Homeland Security-financed “fusion

centers,” designed to collect and analyze data to deter terrorist attacks, have

evolved into what are known as “all-crimes” or “all-hazards” operations,

branching out from terrorism to focus on violent crime and natural disasters.

Intelligence officials assert that Al Qaeda remains intent on striking inside

the United States. The Seattle chief of police, R. Gil Kerlikowske, said, “If

the law enforcement focus at the local level is only on counterterrorism, you

will be unable as a local entity to sustain it unless you are an all-crimes

operation, and you may be missing some very significant issues that could be

related to terrorism.”

Chief Kerlikowske is president of a group of police chiefs from major cities who

said in a report last week that local governments were being forced to spend

increasingly scarce resources because, they say, Homeland Security did not pay

for all the costs. “Most local governments move law enforcement,

counterterrorism and intelligence programs down on the priority list because

their municipality has not yet been directly affected by an attack,” the report

said.

Seattle has experienced its own terrorism scares since 9/11, after photographs

of the Space Needle were recovered in 2002 from suspected Qaeda safe houses in

Afghanistan. The city had another jolt last year when the Federal Bureau of

Investigation sought the public’s help in locating two men “exhibiting unusual

behavior” on a ferry. Neither episode proved an actual threat.

In the case of this year’s focus on improvised explosives, the main killer of

American troops in Iraq, Homeland Security officials say the attention to the

domestic threat stems from a classified strategy that President Bush approved

last year that is designed to help the country to deter and defeat I.E.D.’s

before terrorists can detonate them here.

The administration is completing a plan to assign specific training, prevention

and response duties to several federal agencies, including the F.B.I. and

Homeland Security, the officials said. But they also said that state advisers

misunderstood the financing guidelines, and that states could also meet the

requirement by improving their overall preparedness against a range of undefined

terrorist threats.

State officials say the federal government issued the grant requirement without

providing any new information pointing to the danger of bomb threats in the

United States — an approach they said underscored the glaring disconnect between

how states and the federal government view the terrorist threat.

“I.E.D. detection, protection, and prevention is an important issue, and we all

need to be looking at that,” Matthew Bettenhausen, California’s homeland

security director, said in a telephone interview. But, he said of the grant

requirement: “It’s another thing to be so prescriptive; that came as a surprise

to many of us states.”

Maj. Gen. Tod M. Bunting, the homeland security director for Kansas, said

Washington ran the risk of raising undue public alarm by prescribing such a

large part of the grant to bomb prevention.

“A federal cookie-cutter mandate doesn’t work on every state,” said General

Bunting, who is also the state’s adjutant general.

Leesa Berens Morrison, Arizona’s homeland security director, said the new

federal guidance “absolutely surprised us,” and said state officials were

scrambling to comply.

In Massachusetts, Ms. Kayyem regarded a potential grant this year of $20 million

in federal homeland security money as too important to pass up, even though she

said that technically one-quarter of it had to be spent on I.E.D.’s to qualify

for the money. So, Massachusetts officials wrote a creative proposal, pledging

to upgrade bomb squads in many of the state’s 351 cities and towns. It also

proposed buying new hazardous-material suits, radios to communicate between law

enforcement agencies and explosive-detection devices.

But Ms. Kayyem acknowledged that much of the equipment was chosen to serve

double duty. Hazmat suits could be useful in the event of a bombing, but would

be even more help with accidents that state officials regarded as much more

probable, like chemical spills on the Massachusetts Turnpike.

The grant was approved by federal authorities, but Mr. Chertoff warned: “There

are times when you get so far away from the core purpose that it’s hard to

justify the grant money.”

In one effort to crack down on what Mr. Chertoff referred to as “mission creep,”

Homeland Security officials last year imposed restrictions on use of a heavy

truck by the police in Providence, R.I.

The truck had been bought with federal counterterrorism money, based on a plan

that it be used to haul a patrol boat used for port security. But when the

Police Department began to use the truck instead to pull a horse trailer,

federal authorities sought to draw the line, relenting only after local

officials protested in a phone call with Washington, said local and federal

officials.

Eric Schmitt reported from Boston, Phoenix and Topeka, Kan.;

and David Johnston

from Washington.

States Chafing at U.S. Focus on Terrorism, NYT, 26.5.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/26/us/26terror.html

|