|

History > 2008 > USA > Health (VI)

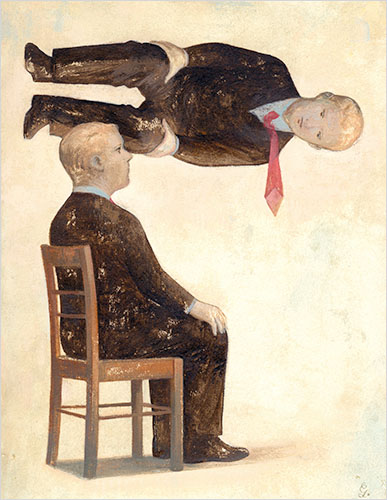

Illustration: Gerard Dubois

NYT

December 1, 2008

Standing in Someone Else’s Shoes, Almost for Real

NYT

2.12.2008

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/02/health/02mind.html

Expansion of Clinics

Shapes a Bush Legacy

December 26, 2008

The New York Times

By KEVIN SACK

NASHVILLE — Although the number of uninsured and the cost of coverage have

ballooned under his watch, President Bush leaves office with a health care

legacy in bricks and mortar: he has doubled federal financing for community

health centers, enabling the creation or expansion of 1,297 clinics in medically

underserved areas.

For those in poor urban neighborhoods and isolated rural areas, including Indian

reservations, the clinics are often the only dependable providers of basic

services like prenatal care, childhood immunizations, asthma treatments, cancer

screenings and tests for sexually transmitted diseases.

As a crucial component of the health safety net, they are lauded as a

cost-effective alternative to hospital emergency rooms, where the uninsured and

underinsured often seek care.

Despite the clinics’ unprecedented growth, wide swaths of the country remain

without access to affordable primary care. The recession has only magnified the

need as hundreds of thousands of Americans have lost their employer-sponsored

health insurance along with their jobs.

In response, Democrats on Capitol Hill are proposing even more significant

increases, making the centers a likely feature of any health care deal struck by

Congress and the Obama administration.

In Nashville, United Neighborhood Health Services, a 32-year-old community

health center, has seen its federal financing rise to $4.2 million, from $1.8

million in 2001. That has allowed the organization to add eight clinics to its

base of six, and to increase its pool of patients to nearly 25,000 from 10,000.

Still, says Mary Bufwack, the center’s chief executive, the clinics satisfy only

a third of the demand in Nashville’s pockets of urban poverty and immigrant

need.

One of the group’s recent grants helped open the Southside Family Clinic, which

moved last year from a pair of public housing apartments to a gleaming new

building on a once derelict corner.

As she completed a breathing treatment one recent afternoon, Willie Mai Ridley,

a 68-year-old beautician, said she would have sought care for her bronchitis in

a hospital emergency room were it not for the new clinic. Instead, she took a

short drive, waited 15 minutes without an appointment and left without paying a

dime; the clinic would bill her later for her Medicare co-payment of $18.88.

Ms. Ridley said she appreciated both the dignity and the affordability of her

care. “This place is really very, very important to me,” she said, “because you

can go and feel like you’re being treated like a person and get the same medical

care you would get somewhere else and have to pay $200 to $300.”

As governor of Texas, Mr. Bush came to admire the missionary zeal and

cost-efficiency of the not-for-profit community health centers, which qualify

for federal operating grants by being located in designated underserved areas

and treating patients regardless of their ability to pay. He pledged support for

the program while campaigning for president in 2000 on a platform of

“compassionate conservatism.”

In Mr. Bush’s first year in office, he proposed to open or expand 1,200 clinics

over five years (mission accomplished) and to double the number of patients

served (the increase has ended up closer to 60 percent). With the health centers

now serving more than 16 million patients at 7,354 sites, the expansion has been

the largest since the program’s origins in President Lyndon B. Johnson’s war on

poverty, federal officials said.

“They’re an integral part of a health care system because they provide care for

the low-income, for the newly arrived, and they take the pressure off of our

hospital emergency rooms,” Mr. Bush said last year while touring a clinic in

Omaha.

With federal encouragement, the centers have made a major push this decade to

expand dental and mental health services, open on-site pharmacies, extend hours

to nights and weekends and accommodate recent immigrants — legal and otherwise —

by employing bilingual staff. More than a third of patients are now Hispanic,

according to the National Association of Community Health Centers.

The centers now serve one of every three people who live in poverty and one of

every eight without insurance. But a study released in August by the Government

Accountability Office found that 43 percent of the country’s medically

underserved areas lack a health center site. The National Association of

Community Health Centers and the American Academy of Family Physicians estimated

last year that 56 million people were “medically disenfranchised” because they

lived in areas with inadequate primary care.

President-elect Barack Obama has said little about how the centers may fit into

his plans to remake American health care. But he was a sponsor of a Senate bill

in August that would quadruple federal spending on the program — to $8 billion

from $2.1 billion — and increase incentives for medical students to choose

primary care. His wife, Michelle, worked closely with health centers in Chicago

as vice president for community and external relations at the University of

Chicago Medical Center.

And Mr. Obama’s choice to become secretary of health and human services, former

Senator Tom Daschle of South Dakota, argues in his recent book on health care

that financing should be increased, describing the health centers as “a

godsend.”

The federal program, which was first championed in Congress by Senator Edward M.

Kennedy, Democrat of Massachusetts, has earned considerable bipartisan support.

Leading advocates, like Senator Bernie Sanders, independent of Vermont, and

Representative James E. Clyburn, Democrat of South Carolina, the House majority

whip, argue that any success Mr. Obama has in reducing the number of uninsured

will be meaningless if the newly insured cannot find medical homes. In

Massachusetts, health centers have seen increased demand since the state began

mandating health coverage two years ago.

At $8 billion, the Senate measure may be considered a relative bargain compared

with the more than $100 billion needed for Mr. Obama’s proposal to subsidize

coverage for the uninsured. If his plan runs into fiscal obstacles, a vast

expansion of community health centers may again serve as a stopgap while

universal coverage waits for flusher times.

Recent job losses, meanwhile, are stoking demand for the clinics’ services,

often from first-time users. The United Neighborhood Health Services clinics in

Nashville have seen a 35 percent increase in patients this year, with much of

the growth from the newly jobless.

“I’m seeing a lot of professionals that no longer have their insurance or

they’re laid off from their jobs,” said Dr. Marshelya D. Wilson, a physician at

the center’s Cayce clinic. “So they come here and get their health care.”

Studies have generally shown that the health centers — which must be governed by

patient-dominated boards — are effective at reducing racial and ethnic

disparities in medical treatment and save substantial sums by keeping patients

out of hospitals. Their trade association estimates that they save the health

care system $17.6 billion a year, and that an equivalent amount could be saved

if avoidable emergency room visits were diverted to clinics. Some centers,

including here in Nashville, have brokered agreements with hospitals to do

exactly that.

Many centers are finding that federal support is not keeping pace with the

growing cost of treating the uninsured. Government grants now account for 19

percent of community health center revenues, compared with 22 percent in 2001,

according to the Health Resources and Services Administration, which oversees

the program. The largest revenue sources are public insurance plans like

Medicaid, Medicare and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program, making the

centers vulnerable to government belt-tightening.

The centers are known for their efficiency. Though United Neighborhood Health

Services has more than doubled in size this decade, Ms. Bufwack, its chief

executive, manages to run five neighborhood clinics, five school clinics, a

homeless clinic, two mobile clinics and a rural clinic, with 24,391 patients, on

a budget of $8.1 million. Starting pay for her doctors is $120,000. Patients are

charged on an income-based sliding scale, and the uninsured are expected to pay

at least $20 for an office visit. One clinic is housed in a double-wide trailer.

Because of a nationwide shortage of primary care physicians, the clinics rely on

federal programs like the National Health Service Corps that entice medical

students with grants and loan write-offs in exchange for agreements to practice

as generalists in underserved areas. Of the 16 doctors working for United

Neighborhood, seven are current or former participants.

Dr. LaTonya D. Knott, 37, who treated Ms. Ridley for her bronchitis, is among

them. Born to a 15-year-old mother in south Nashville, she herself had been a

regular childhood patient at one of the center’s clinics. After graduating as

her high school’s valedictorian, she went to college on scholarships and then to

medical school on government grants, with an obligation to serve for two years.

She said she now felt a responsibility to be a role model. “I do a whole lot of

social work,” she said, noting that it was not uncommon for children to drop by

the clinic for help with homework, or for a peanut butter sandwich. “It’s not

just that we provide the medical care. I’m trying to provide you with a future.”

Despite such commitment, national staffing shortages have reinforced concerns

about the quality of care at health centers, notably the management of chronic

diseases. This year, the government started collecting data at the centers on

performance measures like cervical cancer screening and diabetes control.

“The question is not just, ‘Are you going to have more community health

centers?’ ” said Dr. H. Jack Geiger, founder of the health centers movement and

a professor emeritus at the City University of New York. “It’s, ‘Are you going

to have adequate services?’ ”

A deeper frustration for health centers concerns their difficulty in securing

follow-up appointments with specialists for patients who are uninsured or have

Medicaid. All too often, said Ms. Bufwack, medical care ends at the clinic door,

reinforcing the need to expand both primary care and health insurance coverage.

“That’s when our doctors feel they’re practicing third world medicine,” she

said. “You will die if you have cancer or a heart condition or bad asthma or

horrible diabetes. If you need a specialist and specialty tests and specialty

meds and specialty surgery, those things are totally out of your reach.”

Expansion of Clinics

Shapes a Bush Legacy, NYT, 26.12.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/26/health/policy/26clinics.html

Psychiatrists

Revising the

Book of Human Troubles

December 18, 2008

The New York Times

By BENEDICT CAREY

The book is at least three

years away from publication, but it is already stirring bitter debates over a

new set of possible psychiatric disorders.

Is compulsive shopping a mental problem? Do children who continually recoil from

sights and sounds suffer from sensory problems — or just need extra attention?

Should a fetish be considered a mental disorder, as many now are?

Panels of psychiatrists are hashing out just such questions, and their answers —

to be published in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders — will have consequences for insurance reimbursement, research

and individuals’ psychological identity for years to come.

The process has become such a contentious social and scientific exercise that

for the first time the book’s publisher, the American Psychiatric Association,

has required its contributors to sign a nondisclosure agreement.

The debate is particularly intense because the manual is both a medical

guidebook and a cultural institution. It helps doctors make a diagnosis and

provides insurance companies with diagnostic codes without which the insurers

will not reimburse patients’ claims for treatment.

The manual — known by its initials and edition number, DSM-V — often organizes

symptoms under an evocative name. Labels like obsessive-compulsive disorder have

connotations in the wider culture and for an individual’s self-perception.

“This is not cardiology or nephrology, where the basic diseases are well known,”

said Edward Shorter, a leading historian of psychiatry whose latest book,

“Before Prozac,” is critical of the manual. “In psychiatry no one knows the

causes of anything, so classification can be driven by all sorts of factors” —

political, social and financial.

“What you have in the end,” Mr. Shorter said, “is this process of sorting the

deck of symptoms into syndromes, and the outcome all depends on how the cards

fall.”

Psychiatrists involved in preparing the new manual contend that it is too early

to say for sure which cards will be added and which dropped.

The current edition of the manual, which was published in 2000, describes 283

disorders — about triple the number in the first edition, published in 1952.

The scientists updating the manual have been meeting in small groups focusing on

categories like mood disorders and substance abuse — poring over the latest

scientific studies to clarify what qualifies as a disorder and what might

distinguish one disorder from another. They have much more work to do, members

say, before providing recommendations to a 28-member panel that will gather in

closed meetings to make the final editorial changes.

Experts say that some of the most crucial debates are likely to include gender

identity, diagnoses of illness involving children, and addictions like shopping

and eating.

“Many of these are going to involve huge fights, I expect,” said Dr. Michael

First, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia who edited the fourth edition of

the manual but is not involved in the fifth.

One example, Dr. First said, is binge eating, now in the manual’s appendix as a

tentative category.

“A lot of people want that included in the manual,” Dr. First said, “and there’s

some research out there, some evidence that drugs are helpful. But binge eating

is also a normal behavior, and you run the risk of labeling up to 30 percent of

people with a disorder they don’t really have.”

The debate over gender identity, characterized in the manual as “strong and

persistent cross-gender identification,” is already burning hot among

transgender people. Soon after the psychiatric association named the group of

researchers working on sexual and gender identity, advocates circulated online

petitions objecting to two members whose work they considered demeaning.

Transgender people are themselves divided about their place in the manual. Some

transgender men and women want nothing to do with psychiatry and demand that the

diagnosis be dropped. Others prefer that it remain, in some form, because a

doctor’s written diagnosis is needed to obtain insurance coverage for treatment

or surgery.

“The language needs to be reformed, at a minimum,” said Mara Keisling, executive

director of the National Center for Transgender Equity. “Right now, the manual

implies that you cannot be a happy transgender person, that you have to be a

social wreck.”

Dr. Jack Drescher, a New York psychoanalyst and member of the sexual disorders

work group, said that, in some ways, the gender identity debate echoed efforts

to remove homosexuality from the manual in the 1970s.

After protests by gay activists provoked a scientific review, the

“homosexuality” diagnosis was dropped in 1973. It was replaced by “sexual

orientation disturbance” and then “ego-dystonic homosexuality” before being

dropped in 1987.

“You had, in my opinion, what was a social issue, not a medical one; and, in

some sense, psychiatry evolved through interaction with the wider culture,” Dr.

Drescher said.

The American Psychiatric Association says the contributors’ nondisclosure

agreement is meant to allow the revisions to begin without distraction and to

prevent authors from making deals to write casebooks or engage in other projects

based on the deliberations without working through the association.

In a phone interview, Dr. Darrel A. Regier, the psychiatric association’s

research director, who with Dr. David Kupfer of the University of Pittsburgh is

co-chairman of the task force, said that experts working on the manual had

presented much of their work in scientific conferences.

“But you need to synthesize what you’re doing and make it coherent before having

that discussion,” Dr. Regier said. “Nobody wants to put a rough draft or raw

data up on the Web.”

Some critics, however, say the secrecy is inappropriate.

“When I first heard about this agreement, I just went bonkers,” said Dr. Robert

Spitzer, a psychiatry professor at Columbia and the architect of the third

edition of the manual. “Transparency is necessary if the document is to have

credibility, and, in time, you’re going to have people complaining all over the

place that they didn’t have the opportunity to challenge anything.”

Scientists who accepted the invitation to work on the new manual — a prestigious

assignment — agreed to limit their income from drug makers and other sources to

$10,000 a year for the duration of the job. “That’s more conservative” than the

rules at many agencies and universities, Dr. Regier said.

This being the diagnostic manual, where virtually every sentence is likely to be

scrutinized, critics have said that the policy is not strict enough. They have

long suspected that pharmaceutical money subtly influences authors’ decisions.

Industry influence was questioned after a surge in diagnoses of bipolar disorder

in young children. Once thought to affect only adults and adolescents, the

disorder in children was recently promoted by psychiatrists on drug makers’

payrolls.

The team working on childhood disorders is expected to debate the merits of

adding pediatric bipolar as a distinct diagnosis, experts say. It is also

expected to discuss whether Asperger’s syndrome, a developmental disorder,

should be merged with high-functioning autism. The two are virtually identical,

but bear different social connotations.

The same team is likely to make a recommendation on so-called sensory processing

disorder, a vague label for a poorly understood but disabling childhood

behavior. Parent groups and some researchers want recognition in the manual in

order to help raise money for research and obtain insurance coverage of

expensive treatments.

“I know that some are pushing very hard to get that in,” Dr. First said, “and

they believe they have been warmly received. But you just never know for sure,

of course, until the thing is published.”

In all, it is a combination of suspense, mystery and prepublication controversy

that many publishers would die for. The psychiatric association knows it has a

corner on the market and a blockbuster series. The last two editions sold more

than 830,000 copies each.

Psychiatrists Revising the Book of

Human Troubles, NYT, 18.12.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/18/health/18psych.html?hp

Mind

A Crisis of Confidence for Masters of the Universe

December 16, 2008

The New York Times

By RICHARD A. FRIEDMAN, M.D.

Meltdown. Collapse. Depression. Panic. The words would seem to

apply equally to the global financial crisis and the effect of that crisis on

the human psyche.

Of course, it is too soon to gauge the true psychiatric consequences of the

economic debacle; it will be some time before epidemiologists can tell us for

certain whether depression and suicide are on the rise. But there’s no question

that the crisis is leaving its mark on individuals, especially men.

One patient, a hedge fund analyst, came to me recently in a state of great

anxiety. “It’s bad, but it might get a lot worse,” I recall him saying. The

anxiety was expected and appropriate: he had lost a great deal of his (and

others’) assets, and like the rest of us he had no idea where the bottom was. I

would have been worried if he hadn’t been anxious.

Over the course of several weeks, with the help of some anti-anxiety medication,

his panic subsided as he realized that he would most likely survive

economically.

But then something else emerged. He came in one day looking subdued and plopped

down in the chair. “I’m over the anxiety, but now I feel like a loser.” This

from a supremely self-confident guy who was viewed by his colleagues as an

unstoppable optimist.

He was not clinically depressed: his sleep, appetite, sex drive and ability to

enjoy himself outside of work were unchanged. This was different.

The problem was that his sense of success and accomplishment was intimately tied

to his financial status; he did not know how to feel competent or good about

himself without this external measure of his value.

He wasn’t the only one. Over the last few months, I have seen a group of

patients, all men, who experienced a near collapse in their self-esteem, though

none of them were clinically depressed.

Another patient summed it up: “I used to be a master-of-the-universe kind of

guy, but this cut me down to size.”

I have plenty of female patients who work in finance at high levels, but none of

them has had this kind of psychological reaction. I can’t pretend this is a

scientific survey, but I wonder if men are more likely than women to respond

this way. At the risk of trading in gender stereotypes, do men rely

disproportionately more on their work for their self-esteem than women do? Or

are they just more vulnerable to the inevitable narcissistic injury that comes

with performing poorly or losing one’s job?

A different patient was puzzled not by his anxiety about the market, but by his

total lack of self-confidence. He had always had an easy intuitive feel for

finance. But in the wake of the market collapse, he seriously questioned his

knowledge and skill.

Each of these patients experienced a sudden loss of the sense of mastery in the

face of the financial meltdown and could not gauge their success or failure

without the only benchmark they knew: a financial profit.

The challenge of maintaining one’s self-esteem without recognition or reward is

daunting. Chances are that if you are impervious to self-doubt and go on feeling

good about yourself in the face of failure, you have either won the

temperamental sweepstakes or you have a real problem tolerating bad news.

Of course, the relationship between self-esteem and achievement can be circular.

Some argue that that the best way to build self-esteem is to tell people at

every turn how nice, smart and talented they are.

That is probably a bad idea if you think that self-esteem and recognition should

be the result of accomplishment; you feel good about yourself, in part, because

you have done something well. On the other hand, it is hard to imagine people

taking the first step without first having some basic notion of self-confidence.

On Wall Street, though, a rising tide lifts many boats and vice versa, which

means that there are many people who succeed — or fail — through no merit or

fault of their own.

This observation might ease a sense of personal responsibility for the economic

crisis, but it was of little comfort to my patients. I think this is because for

many of them, the previously expanding market gave them a sense of power along

with something as strong as a drug: thrill.

The human brain is acutely attuned to rewards like money, sex and drugs. It

turns out that the way a reward is delivered has an enormous impact on its

strength. Unpredictable rewards produce much larger signals in the brain’s

reward circuit than anticipated ones. Your reaction to situations that are

either better or worse than expected is generally stronger to those you can

predict.

In a sense, the stock market is like a vast gambling casino where the reward can

be spectacular, but always unpredictable. For many, the lure of investing is the

thrill of uncertain reward. Now that thrill is gone, replaced by anxiety and

fear.

My patients lost more than money in the market. Beyond the rush and excitement,

they lost their sense of competence and success. At least temporarily: I have no

doubt that, like the economy, they will recover. But it’s a reminder of just how

fragile our self-confidence can be.

Richard A. Friedman is a professor of psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical

College.

A Crisis of

Confidence for Masters of the Universe, NYT, 16.12.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/16/health/views/16mind.html

Suits

Over ‘Light’ Cigarettes Allowed

December

15, 2008

Filed at 11:18 a.m. ET

The New York Times

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

WASHINGTON

(AP) -- The Supreme Court on Monday handed a surprising defeat to tobacco

companies counting on it to put an end to lawsuits alleging deceptive marketing

of ''light'' cigarettes.

In a 5-4 split won by the court's liberals, it ruled that smokers may use state

consumer protection laws to sue cigarette makers for the way they promote

''light'' and ''low tar'' brands.

The decision was at odds with recent anti-consumer rulings that limited state

regulation of business in favor of federal power.

The tobacco companies argued that the lawsuits are barred by the federal

cigarette labeling law, which forbids states from regulating any aspect of

cigarette advertising that involves smoking and health.

Justice John Paul Stevens, however, said in his majority opinion that the

labeling law does not shield the companies from state laws against deceptive

practices. The decision forces tobacco companies to defend dozens of suits filed

by smokers in Maine, where the case originated, and across the country.

People suing the cigarette makers still must prove that the use of 'light' and

'lowered tar' actually violate the state anti-fraud laws, but those lawsuits may

go forward, Stevens said.

He was joined by the other liberal justices, Stephen Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg

and David Souter, as well as Justice Anthony Kennedy, whose vote often decides

cases where there is an ideological division.

The conservative justices, Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Samuel Alito,

Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas, dissented.

Thomas, writing for the dissenters, said the link between the fraud claims and

smokers' health is unmistakable.

But he also said: ''The alleged misrepresentation here -- that 'light' and

'low-tar' cigarettes are not as healthy as advertised -- is actionable only

because of the effect that smoking light and low-tar cigarettes had on

respondents' health.''

Three Maine residents sued Altria Group Inc. and its Philip Morris USA Inc.

subsidiary under the state's law against unfair marketing practices. The

class-action claim represents all smokers of Marlboro Lights or Cambridge Lights

cigarettes, both made by Philip Morris.

The lawsuit argues that the company knew for decades that smokers of light

cigarettes compensate for the lower levels of tar and nicotine by taking longer

puffs and compensating in other ways.

A federal district court threw out the lawsuit, but the 1st U.S. Circuit Court

of Appeals said it could go forward.

The case is Altria Group Inc. v. Good, 07-562.

Suits Over ‘Light’ Cigarettes Allowed, NYT, 15.12.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2008/12/15/washington/AP-Scotus-Cigarette-Suit.html?hp

Op-Ed Contributor

Inhaling Fear

December 12, 2008

The New York Times

By MARTIN LINDSTROM

Sydney, Australia

TEN years ago, in settling the largest civil lawsuit in American history, Big

Tobacco agreed to pay the 50 states $246 billion, which they’ve used in part to

finance efforts to prevent smoking. The percentage of American adults who smoke

has fallen since then to just over 20 percent from nearly 30 percent, but

smoking is still the No. 1 preventable cause of death in the United States, and

smoking-related health care costs more than $167 billion a year.

To reduce this cost, the incoming Obama administration should abandon one

antismoking strategy that isn’t working.

A key component of the Food and Drug Administration’s approach to smoking

prevention is to warn about health dangers: Smoking causes fatal lung cancer;

smoking causes emphysema; smoking while pregnant causes birth defects. Compared

with warnings issued by other nations, these statements are low-key. From Canada

to Thailand, Australia to Brazil, warnings on cigarette packs include vivid

images of lung tumors, limbs turned gangrenous by peripheral vascular disease

and open sores and deteriorating teeth caused by mouth and throat cancers. In

October, Britain became the first European country to require similar gruesome

images on packaging.

But such warnings don’t work. Worldwide, people continue to inhale 5.7 trillion

cigarettes annually — a figure that doesn’t even take into account duty-free or

black-market cigarettes. According to World Bank projections, the number of

smokers is expected to reach 1.6 billion by 2025, from the current 1.3 billion.

A brain-imaging experiment I conducted in 2006 explains why antismoking scare

tactics have been so futile. I examined people’s brain activity as they reacted

to cigarette warning labels by using functional magnetic resonance imaging, a

scanning technique that can show how much oxygen and glucose a particular area

of the brain uses while it works, allowing us to observe which specific regions

are active at any given time.

We tested 32 people (from Britain, China, Germany, Japan and the United States),

some of whom were social smokers and some of whom were two-pack-a-day addicts.

Most of these subjects reported that cigarette warning labels reduced their

craving for a cigarette, but their brains told us a different story.

Each subject lay in the scanner for about an hour while we projected on a small

screen a series of cigarette package labels from various countries — including

statements like “smoking kills” and “smoking causes fatal lung cancers.” We

found that the warnings prompted no blood flow to the amygdala, the part of the

brain that registers alarm, or to the part of the cortex that would be involved

in any effort to register disapproval.

To the contrary, the warning labels backfired: they stimulated the nucleus

accumbens, sometimes called the “craving spot,” which lights up on f.M.R.I.

whenever a person craves something, whether it’s alcohol, drugs, tobacco or

gambling.

Further investigation is needed, but our study has already revealed an

unintended consequence of antismoking health warnings. They appear to work

mainly as a marketing tool to keep smokers smoking.

Barack Obama has said he’s been using nicotine gum to fight his own cigarette

habit. His new administration can help other smokers quit, too, by eliminating

the government scare tactics that only increase people’s craving.

Martin Lindstrom is the author of “Buyology: Truth and Lies About Why We Buy.”

Inhaling Fear, NYT,

12.12.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/12/opinion/12lindstrom.html

Uninsured Put a Strain on Hospitals

December 9, 2008

The New York Times

By REED ABELSON

As increasing numbers of the unemployed and uninsured turn to

the nation’s emergency rooms as a medical last resort, doctors warn that the

centers — many already overburdened — could have even more trouble handling the

heart attacks, broken bones and other traumas that define their core mission.

Even before the recession became evident, many emergency rooms around the

country were already overcrowded, with dangerously long waits for some patients

and the frequent need to redirect ambulances to other hospitals.

“We have no capacity now,” said Dr. Angela F. Gardner, the president-elect of

the American College of Emergency Physicians, which represents 27,000 emergency

doctors. “There’s no way we have room for any more people to come to the table.”

In a report to be released Tuesday, her group warns that the nation’s system of

emergency rooms is in “serious condition.” Dr. Gardner argues that any public

discussion of overhauling the current health system must include the nation’s

emergency departments.

The number of patients coming to emergency departments has been steadily

increasing. Helping push up that volume have been the growing ranks of the

uninsured, because emergency rooms are legally obliged to see all patients who

enter their doors, regardless of their ability to pay. But even insured patients

who have no quick access to regular doctors are also showing up — among them

older people, who represent the fastest growing population of emergency room

visitors.

So far, there are no firm figures on the recent influx. But even two years ago,

when a government survey found that the annual volume of visits to emergency

departments had reached 120 million — a third higher than a decade earlier —

doctors considered many emergency rooms overburdened.

Now the recession, whose full impact is yet to be seen, threatens to make

conditions even worse, emergency doctors say. Hospitals are absorbing increasing

amounts in unpaid medical bills, and some are already experiencing much higher

numbers of patients without insurance.

For example, Denver Health, a public hospital system, had a 19 percent increase

in emergency visits by uninsured patients in November — to 3,325, up from 2,792

a year earlier.

“Virtually every time I work a nine-hour shift, I encounter a couple of patients

who have never been here before because they’ve just lost their insurance,” said

Dr. Vincent J. Markovchick, the director of the hospital’s emergency medical

services.

They include patients like Matthew Armijo, 29, who was laid off from his client

services job at a technology company in August and could continue his health

insurance only through October. He showed up at Denver Health’s urgent care

center, a part of the emergency department, suffering from increasing abdominal

pain. Mr. Armijo said he went there because he would not have to pay anything.

Denver Health expects the amount of care it delivers for which it will never be

paid to grow to more than $300 million this year, compared with $276 million in

2007.

Some patients are people who have delayed seeking medical care as long as they

can, like those who arrive during an asthma attack after deferring treatment.

“I am definitely seeing patients coming in presenting worse in their illness

because they are further along,” said Dr. Katherine A. Bakes, the director of

the program’s emergency services for children.

Other doctors around the country also report treating people who seem to have no

other option. One emergency room doctor in Iowa, Dr. Thomas E. Benzoni, said he

recently saw a mother come in with her two children for what he thought was

routine care. When he asked her why she had not gone to her family doctor, she

said she did not have health insurance.

“I don’t know what else she was supposed to do,” Dr. Benzoni said.

The increase is not affecting all emergency rooms. Some emergency physicians, in

fact, said there had actually been a recent decline in visits. A report by the

American Hospital Association for July, August and September found a slight

overall decrease in hospital traffic, including emergency visits, as some people

apparently sought to avoid spending money on anything they did not deem

absolutely essential.

But as the recession continues, many officials of the college of emergency

doctors predict it is only a matter of time until the rising number of uninsured

and the delays in getting primary care create a crisis.

“I think we’re seeing the tip,” said Dr. Nicholas J. Jouriles, the group’s

current president. Patients, he said, will have no choice but to come to the

emergency department when they have no money or insurance. “They will get turned

away elsewhere,” he said.

One of the doctors’ major concerns is the long waits by patients requiring a

hospital bed. The doctors group, surveying its members last year, learned of at

least 200 deaths related to the practice of “boarding” — in which patients on

stretchers line the corridors until they can be moved into a bed.

“Crowding is a national public health problem,” said Dr. Jesse M. Pines, an

emergency physician in Philadelphia.

Patients forced to wait for hours on end for a bed clearly suffer.

“It was pure hell,” recalled Robert Roth, whose 90-year-old mother, Kato, last

year spent 36 hours at the emergency department of a Queens hospital, near her

home in Jackson Heights, waiting for a room after going to the emergency room in

the middle of the night. Mrs. Roth, who had a recent series of falls, said she

had been hearing music in her ears, and both her son and the doctor he called

were worried about a possible stroke.

After the first five hours of waiting, she became increasingly disoriented and

delusional. Mr. Roth was unable to stay with her during the entire wait. After

he left and returned, he said, the hospital staff told him they had no idea

where she was. She turned up in an empty room off the emergency department, and

her physical and mental condition had clearly deteriorated, Mr. Roth said. She

believed that she had been kidnapped.

When she had to go several weeks later to another emergency department in

Manhattan, she endured a 20-hour wait for a room, again becoming disoriented

after several hours, forcing her to be sedated.

The emergency staffs “just seemed overwhelmed, overwhelmed,” said Mr. Roth, who

wondered why emergency departments could not handle the elderly in a special

fashion.

Dr. Ann S. O’Malley is a physician and senior researcher for the Center for

Studying Health System Change, a nonprofit group in Washington that has studied

emergency services in different communities. While some hospitals have taken

steps to reduce crowding and move patients more efficiently from the emergency

department into rooms, Dr. O’Malley said, others have responded by expanding

their facilities — attracting more patients.

“Emergency departments,” she said, “are a kind of barometer of the general

health of the rest of the system.”

Dr. Eric J. Lavonas, an emergency physician in Denver, said: “The nation’s

emergency rooms are the end of the line. We will strain and stretch and bulge

under the weight.”

Dr. Gardner, of the emergency doctors’ group, said the question now is whether

the emergency room safety net will break — how often people with heart attacks

will not be able to get care in time to be saved. Her group’s report, she said,

is meant to alert people to the precarious nature of the system.

“What they don’t understand,” she said, “is that the system is fundamentally

flawed and will fail.”

Melinda Sink contributed reporting from Denver.

Uninsured Put a

Strain on Hospitals, NYT, 9.12.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/09/business/09emergency.html

Sharon Yacketta has had almost 20 surgeries

since a botched operation in 2004 at

University Hospital in Syracuse.

Then the errors there snowballed, a lawsuit says.

“They messed my life up,” Ms.

Yacketta said of her surgeons.

James Rajotte for The New York Times

Weak Oversight Lets Bad Hospitals Stay Open

NYT

8.12.2008

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/08/business/08hospital.html

The Evidence Gap

Weak

Oversight Lets Bad Hospitals Stay Open

December 8, 2008

The New York Times

By ALEX BERENSON

SYRACUSE — In March 2004, Sharon Yacketta walked into University Hospital

here for an operation to help control her incontinence.

But her doctor, Robert S. Lai, botched the procedure, causing urine to leak into

her abdomen. A month later, Dr. Lai and a second surgeon perforated her colon

during a follow-up operation at University. Four years and 20 operations later,

Ms. Yacketta has lost most of her colon and is still incontinent.

“They messed my life up,” Ms. Yacketta said of her surgeons. “I hope those

doctors rot.”

Dr. Lai, who has left University and now practices outside Chicago, acknowledged

that he and his surgical team had accidentally injured Ms. Yacketta but said he

had not been negligent.

Mistakes happen even at good hospitals, of course. But evidence shows that

University, which is owned by the State University of New York system, is not a

good hospital. In fact, in late 2006 a state commission recommended that it be

scaled back and merged with another hospital.

The state’s inability to follow through on that plan for University provides a

stark example of how hard it can be — not just in New York, but around the

nation — to close or shrink hospitals, even when there is evidence they are

providing costly and below-average care.

Certainly the evidence against University Hospital was strong. In 2006, patients

at University were three times as likely to develop infections stemming from

hospitals as were patients at the average New York hospital. HealthGrades, a

company that rates hospitals using data from Medicare, ranks University among

the least safe hospitals in the United States — although the hospital’s

executives strongly dispute that assertion. University, meanwhile, is expensive

to run.

Yet, today, University remains under state ownership. And far from shrinking,

University is expanding.

Unlike some other nations, including France, the United States has no federal

agency charged with hospital oversight. Instead, it relies on a patchwork of

state health departments and a nonprofit group called the Joint Commission that

sets basic quality standards for the nation. Hospitals are rarely closed or hit

with significant financial penalties for hurting patients.

One of the reasons is that even troubled hospitals are major employers, and

communities generally rally behind them when they face the threat of cuts, as

Syracuse did for University.

“We haven’t been forthright about the dirty little secret, the huge variation of

quality and safety in the system,” said Arthur Aaron Levin, director of the

Center for Medical Consumers, a nonprofit patient advocacy group. Nearly a

decade after the Institute of Medicine report, preventable errors remain

shockingly common, said Mr. Levin, who was a member of the commission that wrote

the report.

“It’s nine years later, and we can’t even tell you if it’s better,” Mr. Levin

said. “How is that permissible?”

Any effort to maintain national standards is left largely to Medicare and the

Joint Commission, a nonprofit group based in Oakbrook Terrace, Ill., which along

with state health departments certifies that hospitals are operating safely.

But the commission lacks the heft and enforcement powers of a federal regulator.

With fewer than 1,000 employees, it accredits and sets patient safety goals for

17,000 hospitals, nursing homes and assisted-living providers nationally. A

typical survey lasts less than a week and involves fewer than a half-dozen

examiners, said Dr. Mark R. Chassin, the president of the Joint Commission.

Hospitals account for the largest single slice of the nation’s medical spending,

31 percent, or about $650 billion in 2007, according to Medicare. Despite that

enormous bill, hospital care is uneven, and often deadly. In 1999, a report from

the Institute of Medicine found that hospital errors caused as many as 98,000

deaths a year in the United States.

Medicare is pressing for quality improvements, using as leverage the $155

billion it spends on hospital care annually. But Herb Kuhn, deputy administrator

of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, said hospitals would not make

patient safety their top priority until Medicare changed its reimbursement

system.

At present, Medicare pays the same amount to a hospital for treating a patient,

whether that patient lives or dies — even if the hospital made a preventable

error that caused the patient’s death. On Oct. 1, Medicare began a project to

end payments for a handful of “hospital-acquired conditions,” Medicare-speak for

illnesses caused by preventable errors. But the program is scheduled to reduce

reimbursement by only $21 million in 2009, not enough to make a major

difference, Mr. Kuhn said.

“We’ve got to get our payment systems changed,” he said.

States’ Efforts

While Medicare experiments, states are making their own halting efforts to

improve quality while lowering costs. Among the first was New York, which in

April 2005 created an 18-member panel to make systematic recommendations about

which hospitals and nursing homes should be closed statewide.

The need for change is acute in New York, which has among the most dysfunctional

and expensive health-care systems in the nation. In 2004, New Yorkers and their

insurers spent an average of $6,535 for each patient on health care, 24 percent

more than the national average. Yet New Yorkers are more likely to die from

chronic disease than people in any other state.

The legislation that created the panel, generally called the Berger Commission,

after its chairman, Stephen Berger, provided that its recommendations would

become law unless lawmakers overruled them.

But the legislation also provided that the state Health Department, not the

commission itself, would enforce the commission’s recommendations. That loophole

would eventually prove crucial.

On Nov. 30, 2006, after studying the state’s health-care system for almost two

years, the commission announced that nine hospitals should close and 50 others

should shrink or merge. Among the commission’s recommendations was that

University Hospital be joined with Crouse Hospital, its neighbor in Syracuse,

and that the new hospital have fewer than 600 beds, compared with the 366 beds

at University and 576 beds at Crouse, a private nonprofit hospital.

Both hospitals had problems. In 2006, patients at University had a 1-in-37

chance of suffering postoperative blood infections, compared with a 1-in-65

chance statewide, according to the Niagara Health Quality Consortium, a

nonprofit group that analyzes hospital billing records.

They had an 8.6 percent chance of dying from pneumonia, compared with a 5.5

percent chance statewide. Like HealthGrades, Niagara tries to adjust the data so

that hospitals are not penalized if the patients they treat are sicker to begin

with than those that the average hospital treats.

Crouse, for its part, had filed for bankruptcy protection in 2001 and was

running at 50 percent occupancy. Of all the commission’s recommendations,

merging University and Crouse “was the most obvious,” Mr. Berger, an investment

banker, said in a recent interview.

But University and Crouse disagreed. Days after the commission released its

report, Dr. David R. Smith, the president of Upstate Medical University, the

state-run medical school that owns University Hospital, began lobbying Eliot

Spitzer, then the governor, and Dr. Richard Daines, the state health

commissioner, to undo the recommendation.

“We’re a university, not just a hospital,” said Dr. Smith, who took over Upstate

in September 2006.

Dr. Smith and other officials at University say that the patient safety

statistics are misleading because they do not fully capture the fact that the

hospital treats very sick patients.

Dr. David Duggan, an associate dean at Upstate Medical, said that other surveys

show that University Hospital’s patient safety record is generally on par with

other hospitals. “There are some areas where I think we are above average,” Dr.

Duggan said, “and other areas where I think we need to work.”

In his battle to keep University independent of Crouse, Dr. Smith had a powerful

ally: the hospital’s unions. Most hospital employees in New York, including

those at Crouse, are represented by Local 1199. But those at University are

represented by state employees’ unions, which have richer contracts than 1199.

In 2007, University Hospital received a state subsidy of $42.2 million, about

$2,500 for each patient it admitted, to make up the difference. Not

surprisingly, University unions paid for television advertisements, lobbied

lawmakers and filed a lawsuit to overturn the recommendations.

Within Syracuse, University also had support. The medical school and hospital

are by far the largest employer in the city. “They employ people at decent

jobs,” said James Tallon, the president of the United Hospital Fund, a nonprofit

group that studies health care in New York State. “And the money comes from

Washington — money comes from elsewhere.”

By spring 2007, the state Health Department backed off the plan to join

University and Crouse, saying both could remain open and independent.

But Mr. Berger, whose commission had no authority after it filed its report in

late 2006, says the public would be better off if the state had followed its

recommendation by folding University into Crouse.

“The place that I’m most unhappy about,” he said, “is Syracuse.”

The Errors Snowball

Sharon Yacketta, 56, has not had an easy life: four brief marriages, three

children given up for adoption, six months in jail for welfare fraud. She lives

in a two-room apartment near downtown Syracuse, with dingy gray carpets and a

hulking black television.

On March 12, 2004, she entered University Hospital for an operation by Dr. Lai

to relieve her incontinence. But during the surgery, a suture punctured her

right ureter — the duct connecting the kidney to the bladder — and urine began

leaking into her abdomen, according to a lawsuit she has filed against

University that takes its details directly from her medical records.

Then the errors snowballed, according to the complaint, which lays out in flatly

clinical language three years of suffering.

Ms. Yacketta suffered near-fatal infections, endured severe pain and watched in

horror as urine and stool leaked from her body. Since the first surgery, she has

had at least 19 operations. In October 2005, she moved to St. Joseph’s Hospital,

which by many measures is the highest-rated hospital in Syracuse.

Since then, she has been under the care of Dr. B. Sivikumar, director of St.

Joseph’s surgical intensive care unit. Dr. Sivikumar said that Ms. Yacketta’s

continuing problems were very likely caused by the initial operations at

University.

After examining Ms. Yacketta’s claims, Dr. Jonathan Fine, a retired internist

and founder of At Your Side, a nonprofit group that trains volunteers as bedside

advocates for patients, said University had repeatedly made preventable errors

in her care.

“This case alone merits, from ground up, a total revamping of the procedures

that are in place in that hospital, and the culture of the hospital,” Dr. Fine

said.

Dr. Duggan said he could not comment specifically on Ms. Yacketta’s suit but

cautioned against reading too much into any one case. “We are not going to be

able to prevent every problem from occurring,” he said.

Other lawsuits, and reports from the state Health Department, also point to

problems at University. A 2005 state report refers to a case of surgery on an

infant in which “generally accepted standards of professional care were not

consistently provided,” leading the infant to be discharged prematurely and

return in less than 48 hours with kidney failure.

Another report, after a surgery in December 2006 in which doctors operated on

the wrong part of the body, criticizes the hospital for failing to make changes

promised after another “wrong-site surgery” two years before.

Dr. Smith said he had made patient safety a priority for University. “It is a

major focus of this institution,” he said.

But without faster and more accurate data gathering, no one outside University —

or any other hospital — can know whether it is doing a good job, or penalize it

if it is not, said Dr. Donald Berwick, the president of the Institute for

Healthcare Improvement, a national nonprofit group trying to reduce hospital

mistakes.

“We need to act with more speed and diligence to stop practice where it’s

actively harmful,” Dr. Berwick said. “Let the needs of patients come first, not

the needs of a hospital.”

Weak Oversight Lets Bad

Hospitals Stay Open, NYT, 8.12.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/08/business/08hospital.html?hp

Warning Given

on Use of 4 Popular Asthma Drugs,

but Debate

Remains

December 6, 2008

The New York Times

By GARDINER HARRIS

WASHINGTON — Two federal drug officials have concluded that asthma sufferers

risk death if they continue to use four hugely popular asthma drugs — Advair,

Symbicort, Serevent and Foradil. But the officials’ views are not universally

shared within the government.

The two officials, who work in the safety division of the Food and Drug

Administration, wrote in an assessment on the agency’s Web site on Friday that

asthma sufferers of all ages should no longer take the medicines. A third

drug-safety official concluded that Advair and Symbicort could be used by adults

but that all four drugs should no longer be used by people age 17 and under.

Dr. Badrul A. Chowdhury, director of the division of pulmonary and allergy

products at the agency, cautioned in his own assessment that the risk of death

associated with the drugs was small and that banning their use “would be an

extreme approach” that could lead asthmatics to rely on other risky medications.

Once unheard of, public disagreements among agency experts have occurred on

occasion in recent years. The agency is convening a committee of experts on

Wednesday and Thursday to sort out the disagreement, which has divided not only

the F.D.A. but also clinicians and experts for more than a decade.

Sudden deaths among asthmatics still clutching their inhalers have fed the

debate. But trying to determine whether the deaths were caused by patients’

breathing problems or the inhalers has proved difficult.

The stakes for drug makers are high. Advair sales last year were $6.9 billion

and may approach $8 billion this year, making the medication GlaxoSmithKline’s

biggest seller and one of the biggest-selling drugs in the world. Glaxo also

sells Serevent, which had $538 million in sales last year. Symbicort is made by

AstraZeneca and Foradil by Novartis.

Whatever the committee’s decision, the drugs will almost certainly remain on the

market because even the agency’s drug-safety officials concluded that they were

useful in patients suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, nearly

all of whom are elderly.

Dr. Katharine Knobil, global clinical vice president for Glaxo, dismissed the

conclusions of the agency’s drug-safety division as “not supported by their own

data.” Dr. Knobil said that Advair was safe and that Serevent was safe when used

with a steroid.

Michele Meeker, a spokeswoman for AstraZeneca, said that the F.D.A.’s safety

division improperly excluded most studies of Symbicort in its analysis, and that

a review of all of the information shows that the drug does not increase the

risks of death or hospitalization.

Dr. Daniel Frattarelli, a Detroit pediatrician and member of the American

Academy of Pediatrics’s committee on drugs, said that he was treating children

with Advair and that his committee had recently discussed the safety of the

medicines.

“Most of us felt these were pretty good drugs,” Dr. Frattarelli said. “I’m

really looking forward to hearing what the F.D.A. committee decides.”

About 9 percent of Advair’s prescriptions go to those age 17 and under,

according to Glaxo. Ms. Meeker could not provide similar figures for Symbicort.

In 1994, Serevent was approved for sale, and the F.D.A. began receiving reports

of deaths. A letter to the New England Journal of Medicine described two elderly

patients who died holding Serevent inhalers. Glaxo warned patients that the

medicine, unlike albuterol, does not work instantly and should not be used

during an attack.

In 1996, Glaxo began a study of Serevent’s safety, but the company refused for

years to report the results publicly. In 2001, the company introduced Advair,

whose sales quickly cannibalized those of Serevent and then far surpassed them.

Finally in 2003, Glaxo reported the results of its Serevent study, which showed

that those given the medicine were more likely to die than those given placebo

inhalers. Glaxo said problems with the trial made its results impossible to

interpret.

Asthma is caused when airways within the lungs spasm and swell, restricting the

supply of oxygen. The two primary treatments are steroids, which reduce

swelling, and beta agonists, which treat spasms. Rescue inhalers usually contain

albuterol, which is a beta agonist with limited duration. Serevent and Foradil

are both beta agonists but have a longer duration than albuterol and were

intended to be taken daily to prevent attacks.

Advair contains Serevent and a steroid. Symbicort, introduced last year,

contains Foradil and a steroid. In the first nine months of this year, Symbicort

had $209 million in sales.

The problem with albuterol is that it seems to make patients’ lungs more

vulnerable to severe attacks, which is why asthmatics are advised to use their

rescue inhalers only when needed. The long-acting beta agonists may have the

same risks.

But drug makers say this risk disappears when long-acting beta agonists are

paired with steroids. The labels that accompany Serevent and Foradil instruct

doctors to pair the medicines with an inhaled steroid.

Warning Given on Use of

4 Popular Asthma Drugs, but Debate Remains, NYT, 7.12.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/06/health/policy/06allergy.html?em

When a Job Disappears, So Does the Health Care

December 7, 2008

The New York Times

By ROBERT PEAR

ASHLAND, Ohio — As jobless numbers reach levels not seen in 25 years, another

crisis is unfolding for millions of people who lost their health insurance along

with their jobs, joining the ranks of the uninsured.

The crisis is on display here. Starla D. Darling, 27, was pregnant when she

learned that her insurance coverage was about to end. She rushed to the

hospital, took a medication to induce labor and then had an emergency Caesarean

section, in the hope that her Blue Cross and Blue Shield plan would pay for the

delivery.

Wendy R. Carter, 41, who recently lost her job and her health benefits, is

struggling to pay $12,942 in bills for a partial hysterectomy at a local

hospital. Her daughter, Betsy A. Carter, 19, has pain in her lower right jaw,

where a wisdom tooth is growing in. But she has not seen a dentist because she

has no health insurance.

Ms. Darling and Wendy Carter are among 275 people who worked at an Archway

cookie factory here in north central Ohio. The company provided excellent health

benefits. But the plant shut down abruptly this fall, leaving workers without

coverage, like millions of people battered by the worst economic crisis since

the Depression.

About 10.3 million Americans were unemployed in November, according to the

Bureau of Labor Statistics. The number of unemployed has increased by 2.8

million, or 36 percent, since January of this year, and by 4.3 million, or 71

percent, since January 2001.

Most people are covered through the workplace, so when they lose their jobs,

they lose their health benefits. On average, for each jobless worker who has

lost insurance, at least one child or spouse covered under the same policy has

also lost protection, public health experts said.

Expanding access to health insurance, with federal subsidies, was a priority for

President-elect Barack Obama and the new Democratic Congress. The increase in

the ranks of the uninsured, including middle-class families with strong ties to

the work force, adds urgency to their efforts.

“This shows why — no matter how bad the condition of the economy — we can’t

delay pursuing comprehensive health care,” said Senator Sherrod Brown, Democrat

of Ohio. “There are too many victims who are innocent of anything but working at

the wrong place at the wrong time.”

Some parts of the federal safety net are more responsive to economic distress.

The number of people on food stamps set a record in September, with 31.6 million

people receiving benefits, up by two million in one month.

Nearly 4.4 million people are receiving unemployment insurance benefits, an

increased of 60 percent in the past year. But more than half of unemployed

workers are not getting help because they do not qualify or have exhausted their

benefits.

About 1.7 million families receive cash under the main federal-state welfare

program, little changed from a year earlier. Welfare serves about 4 of 10

eligible families and fewer than one in four poor children.

In a letter dated Oct. 3, Archway told workers that their jobs would be

eliminated, and their insurance terminated on Oct. 6, because of “unforeseeable

business circumstances.” The company, owned by a private equity firm based in

Greenwich, Conn., filed a petition for relief under Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy

Code.

Archway workers typically made $13 to $20 an hour. To save money in a tough

economy, they are canceling appointments with doctors and dentists, putting off

surgery, and going without prescription medicines for themselves and their

children.

Archway cited “the challenging economic environment” as a reason for closing.

“We have been operating at a loss due largely to the significant increases in

raw material costs, such as flour, butter, sugar and dairy, and the record high

fuel costs across the country,” the company said. At this time of year, the

Archway plant is usually bustling as employees work overtime to make Christmas

cookies. This year the plant is silent. The aromas of cinnamon and licorice are

missing. More than 40 trailers sit in the parking lot with nothing to haul.

In the weeks before it filed for bankruptcy protection, Archway apparently fell

behind in paying for its employee health plan. In its bankruptcy filing, Archway

said it owed more than $700,000 to Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois, one

of its largest creditors.

Richard D. Jackson, 53, was an oven operator at the bakery for 30 years. He and

his two daughters often used the Archway health plan to pay for doctor’s visits,

imaging, surgery and medicines. Now that he has no insurance, Mr. Jackson takes

his Effexor antidepressant pills every other day, rather than daily, as

prescribed.

Another former Archway employee, Jeffrey D. Austen, 50, said he had canceled

shoulder surgery scheduled for Oct. 13 at the Cleveland Clinic because he had no

way to pay for it.

“I had already lined up an orthopedic surgeon and an anesthesiologist,” Mr.

Austen said.

In mid-October, Janet M. Esbenshade, 37, who had been a packer at the Archway

plant, began to notice that her vision was blurred. “My eyes were burning,

itching and watery,” she said. “Pus was oozing out. If I had had insurance, I

would have gone to an eye doctor right away.”

She waited two weeks. The infection became worse. She went to the hospital on

Oct. 26. Doctors found that she had keratitis, a painful condition that she may

have picked up from an old pair of contact lenses. They prescribed antibiotics,

which have cleared up the infection.

Ms. Esbenshade has two daughters, ages 6 and 10, with asthma. She has explained

to them why “we are not Christmas shopping this year — unless, by some miracle,

mommy goes back to work and gets a paycheck.”

She said she had told the girls, “I would rather you stay out of the hospital

and take your medication than buy you a little toy right now because I think

your health is more important.”

In some cases, people who are laid off can maintain their group health benefits

under a federal law, the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1986,

known as Cobra. But that is not an option for former Archway employees because

their group health plan no longer exists. And they generally cannot afford to

buy insurance on their own.

Wendy Carter’s case is typical. She receives $956 a month in unemployment

benefits. Her monthly expenses include her share of the rent ($300), car

payments ($300), auto insurance ($75), utilities ($220) and food ($260). That

leaves nothing for health insurance.

Ms. Darling, who was pregnant when her insurance ran out, worked at Archway for

eight years, and her father, Franklin J. Phillips, worked there for 24 years.

“When I heard that I was losing my insurance,” she said, “I was scared. I

remember that the bill for my son’s delivery in 2005 was about $9,000, and I

knew I would never be able to pay that by myself.”

So Ms. Darling asked her midwife to induce labor two days before her health

insurance expired.

“I was determined that we were getting this baby out, and it was going to be

paid for,” said Ms. Darling, who was interviewed at her home here as she cradled

the infant in her arms.

As it turned out, the insurance company denied her claim, leaving Ms. Darling

with more than $17,000 in medical bills.

The latest official estimate of the number of uninsured, from the Census Bureau,

is for 2007, when the economy was in better condition. In that year, the bureau

says, 45.7 million people, accounting for 15.3 percent of the population, were

uninsured.

M. Harvey Brenner, a professor of public health at the University of North Texas

and Johns Hopkins University, said that three decades of research had shown a

correlation between the condition of the economy and human health, including

life expectancy.

“In recessions, with declines in national income and increases in unemployment,

you often see increases in mortality from heart disease, cancer, psychiatric

illnesses and other conditions,” Mr. Brenner said.

The recession is also taking a toll on hospitals.

“We have seen a significant increase in patients seeking assistance paying their

bills,” said Erin M. Al-Mehairi, a spokeswoman for Samaritan Hospital in

Ashland. “We’ve had a 40 percent increase in charity care write-offs this year

over the 2007 level of $2.7 million.”

In addition, people are using the hospital less. “We’ve seen a huge decrease in

M.R.I.’s, CAT scans, stress tests, cardiac catheterization tests, knee and hip

replacements and other elective surgery,” Ms. Al-Mehairi said.

When a Job Disappears,

So Does the Health Care, NYT, 7.12.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/07/us/07uninsured.html?hp

H. M., an Unforgettable Amnesiac, Dies at 82

December 5, 2008

The New York Times

By BENEDICT CAREY

He knew his name. That much he could remember.

He knew that his father’s family came from Thibodaux, La., and his mother was

from Ireland, and he knew about the 1929 stock market crash and World War II and

life in the 1940s.

But he could remember almost nothing after that.

In 1953, he underwent an experimental brain operation in Hartford to correct a

seizure disorder, only to emerge from it fundamentally and irreparably changed.

He developed a syndrome neurologists call profound amnesia. He had lost the

ability to form new memories.

For the next 55 years, each time he met a friend, each time he ate a meal, each

time he walked in the woods, it was as if for the first time.

And for those five decades, he was recognized as the most important patient in

the history of brain science. As a participant in hundreds of studies, he helped

scientists understand the biology of learning, memory and physical dexterity, as

well as the fragile nature of human identity.

On Tuesday evening at 5:05, Henry Gustav Molaison — known worldwide only as H.

M., to protect his privacy — died of respiratory failure at a nursing home in

Windsor Locks, Conn. His death was confirmed by Suzanne Corkin, a neuroscientist

at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who had worked closely with him

for decades. Henry Molaison was 82.

From the age of 27, when he embarked on a life as an object of intensive study,

he lived with his parents, then with a relative and finally in an institution.

His amnesia did not damage his intellect or radically change his personality.

But he could not hold a job and lived, more so than any mystic, in the moment.

“Say it however you want,” said Dr. Thomas Carew, a neuroscientist at the

University of California, Irvine, and president of the Society for Neuroscience.

“What H. M. lost, we now know, was a critical part of his identity.”

At a time when neuroscience is growing exponentially, when students and money

are pouring into laboratories around the world and researchers are mounting

large-scale studies with powerful brain-imaging technology, it is easy to forget

how rudimentary neuroscience was in the middle of the 20th century.

When Mr. Molaison, at 9 years old, banged his head hard after being hit by a

bicycle rider in his neighborhood near Hartford, scientists had no way to see

inside his brain. They had no rigorous understanding of how complex functions

like memory or learning functioned biologically. They could not explain why the

boy had developed severe seizures after the accident, or even whether the blow

to the head had anything do to with it.

Eighteen years after that bicycle accident, Mr. Molaison arrived at the office

of Dr. William Beecher Scoville, a neurosurgeon at Hartford Hospital. Mr.

Molaison was blacking out frequently, had devastating convulsions and could no

longer repair motors to earn a living.

After exhausting other treatments, Dr. Scoville decided to surgically remove two

finger-shaped slivers of tissue from Mr. Molaison’s brain. The seizures abated,

but the procedure — especially cutting into the hippocampus, an area deep in the

brain, about level with the ears — left the patient radically changed.

Alarmed, Dr. Scoville consulted with a leading surgeon in Montreal, Dr. Wilder

Penfield of McGill University, who with Dr. Brenda Milner, a psychologist, had

reported on two other patients’ memory deficits.

Soon Dr. Milner began taking the night train down from Canada to visit Mr.

Molaison in Hartford, giving him a variety of memory tests. It was a

collaboration that would forever alter scientists’ understanding of learning and

memory.

“He was a very gracious man, very patient, always willing to try these tasks I

would give him,” Dr. Milner, a professor of cognitive neuroscience at the

Montreal Neurological Institute and McGill University, said in a recent

interview. “And yet every time I walked in the room, it was like we’d never

met.”

At the time, many scientists believed that memory was widely distributed

throughout the brain and not dependent on any one neural organ or region. Brain

lesions, either from surgery or accidents, altered people’s memory in ways that

were not easily predictable. Even as Dr. Milner published her results, many

researchers attributed H. M.’s deficits to other factors, like general trauma

from his seizures or some unrecognized damage.

“It was hard for people to believe that it was all due” to the excisions from

the surgery, Dr. Milner said.

That began to change in 1962, when Dr. Milner presented a landmark study in

which she and H. M. demonstrated that a part of his memory was fully intact. In

a series of trials, she had Mr. Molaison try to trace a line between two

outlines of a five-point star, one inside the other, while watching his hand and

the star in a mirror. The task is difficult for anyone to master at first.

Every time H. M. performed the task, it struck him as an entirely new

experience. He had no memory of doing it before. Yet with practice he became

proficient. “At one point he said to me, after many of these trials, ‘Huh, this

was easier than I thought it would be,’ ” Dr. Milner said.

The implications were enormous. Scientists saw that there were at least two

systems in the brain for creating new memories. One, known as declarative

memory, records names, faces and new experiences and stores them until they are

consciously retrieved. This system depends on the function of medial temporal

areas, particularly an organ called the hippocampus, now the object of intense

study.

Another system, commonly known as motor learning, is subconscious and depends on

other brain systems. This explains why people can jump on a bike after years

away from one and take the thing for a ride, or why they can pick up a guitar

that they have not played in years and still remember how to strum it.

Soon “everyone wanted an amnesic to study,” Dr. Milner said, and researchers

began to map out still other dimensions of memory. They saw that H. M.’s

short-term memory was fine; he could hold thoughts in his head for about 20

seconds. It was holding onto them without the hippocampus that was impossible.

“The study of H. M. by Brenda Milner stands as one of the great milestones in

the history of modern neuroscience,” said Dr. Eric Kandel, a neuroscientist at

Columbia University. “It opened the way for the study of the two memory systems

in the brain, explicit and implicit, and provided the basis for everything that

came later — the study of human memory and its disorders.”

Living at his parents’ house, and later with a relative through the 1970s, Mr.

Molaison helped with the shopping, mowed the lawn, raked leaves and relaxed in

front of the television. He could navigate through a day attending to mundane

details — fixing a lunch, making his bed — by drawing on what he could remember

from his first 27 years.

He also somehow sensed from all the scientists, students and researchers