|

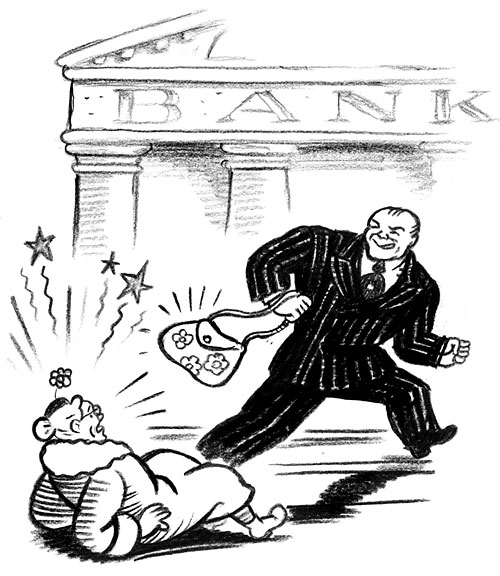

USA > History > 2010 > Economy (II)

Ross MacDonald

Retirees at the Mercy of the Bankers

NYT

25.1.2010

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/25/opinion/l25retirees.html

Overqualified?

Yes, but Happy to Have a Job

March 28, 2010

The New York Times

By MICHAEL LUO

GRANDVIEW, Mo. — Don Carroll, a former financial analyst with

a master’s degree in business administration from a top university, was clearly

overqualified for the job running the claims department for Cartwright

International, a small, family-owned moving company here south of Kansas City.

But he had been out of work for six months, and the department badly needed

modernization after several decades of benign neglect. It turned out to be a

perfect match.

After being hired in December, Mr. Carroll, 31, quickly set about revamping the

four-person department, which settles damage claims from moves, and creating

tracking tools so the company could better understand its spending.

Conventional wisdom warns against hiring overqualified candidates like Mr.

Carroll, who often find themselves chafing at their new roles. (The posting for

his job had specified “bachelor’s degree preferred but not required.”) But four

months into his employment, it seems to be working out well for all involved.

It is a situation being repeated across the country as the aspirations of many

workers have been recalibrated amid the recession, enabling some companies to

reap unexpected rewards.

A result is a new cadre of underemployed workers dotting American companies,

occupying slots several rungs below where they are accustomed to working. These

are not the more drastic examples of former professionals toiling away at

“survival jobs” at Home Depot or Starbucks. They are the former chief financial

officer working as comptroller, the onetime marketing director who is back to

being an analyst, the former manager who is once again an “individual

contributor.”

The phenomenon was probably inevitable in a labor market in which job seekers

outnumber openings five to one. Employers are seizing the opportunity to stock

up on discounted talent, despite the obvious risks that the new hires will

become dissatisfied and leave. “They’re trying to really professionalize this

company,” said Mr. Carroll, who is the sole breadwinner for his family of four

and had lost his home to foreclosure. “I’ve been able to play a big role in

that.”

In some cases, of course, the new employees fail to work out, forcing the

company through the process of hiring and training someone else. But Mr. Carroll

is just one of several recent hires at Cartwright who would be considered

overqualified, including a billing clerk who is a certified public accountant

and a human resources director who once oversaw that domain for 5,000 employees

but is now dealing with just 65.

They represent marked upgrades for Cartwright, a modest-size business with

expanding ambitions. The company is benefiting from an influx of talent it

probably never would have been able to attract in a better economic climate.

“There’s a nice free-agent market right now,” said Randy Woehl, the human

resources director. “The best it’s ever been.”

Exact numbers for workers toiling in positions where their experience or

education exceed their job descriptions are hard to come by, in part because the

concept is difficult to measure and can be quite subjective. Several studies

have put the figure at roughly one in five American workers, although some doubt

the numbers are that high. Economists and sociologists, however, agree that the

frequency inevitably increases in hard times.

Nevertheless, an overriding complaint among many job seekers, particularly

professionals, is how often they are rejected for lower-level positions that

they desperately want and believe they could practically do in their sleep.

Academic research on the subject confirms that workers who perceive themselves

as overqualified do, in fact, report lower job satisfaction and higher rates of

turnover. But the studies also indicate that those workers tend to perform

better. Moreover, there is evidence that many of the negatives that come with

overqualified hires can be mitigated if they are given autonomy and made to feel

valued and respected.

The new variable in all of this is the continuing grim economic climate. Many

workers’ ambitions have evolved, after all, from climbing the ladder to simply

holding on to a job, any job. Turnover would also seem to be less of a concern

amid predictions that it could be years before unemployment returns to

pre-recession levels.

Jackie Swanson, 44, accepted a part-time job in May as a facilities manager at

Conservation Services Group, a Massachusetts company that delivers

energy-efficiency programs and training across the country. She had been laid

off after 16 years at another company, where she had handled more than 50

offices as a corporate facilities planner.

In her previous position, she had been more of a project manager, whereas the

new job was mostly about the upkeep of the headquarters building. Ms. Swanson

managed to convince the company’s recruiter that she was excited about the

organization and that her priorities for a job had changed.

“I was willing to take a drastic cut in pay just to have stability,” she said.

Since then, Ms. Swanson has been promoted to full time. Even though her job

still represents a step down in responsibilities, she has no plans to leave

anytime soon.

“I’m happy here,” she said. “I actually feel respected.”

At Cartwright, Mr. Carroll said he had so far found enough to keep him engaged

because he had mostly been given free rein in the department. He has also

volunteered to help the company’s finance and accounting managers with anything

they might need. Whenever he gets a request from someone higher up the ladder,

he consciously tries to overdeliver.

Nevertheless, there are signs of angst. He is being paid a third less than he

used to make. He and his wife realize that many of their financial goals could

be set back years by this period. He is still paying attention to what is

happening in the job market but is not actively looking.

Mr. Carroll’s cubicle mate, Mindy William, a former graphic designer and single

mother who had been working at Target before she was recently hired as a claims

adjuster, said she had noticed that he seemed to talk about his old job a lot.

“I know it’s been an adjustment for him,” she said. “He’s just making the best

of it like the rest of us are. We’re glad to have jobs in this recession.”

For his part, Mr. Carroll admitted that he had caught himself often trying to

drop his credentials into conversations at his new workplace.

“Obviously that stems from maybe some embarrassment at the level that I’m at,”

he said. “I do want people to know that, to some extent, this isn’t who I am.”

It helps somewhat that most of his former business school classmates are hardly

becoming masters of the universe.

“It’s not like anyone else is tearing it up,” he said.

While he is happy for now, Mr. Carroll worries about what will happen once he

has finished the more interesting work of overhauling the department. He wonders

how long simply having a job will be enough.

Overqualified? Yes,

but Happy to Have a Job, NYT, 29.3.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/29/us/29overqualified.html

Households Facing Foreclosure

Rose in 4th Quarter

March 25, 2010

The New York Times

By DAVID STREITFELD

The ranks of those facing foreclosure swelled by a

quarter-million households in the fourth quarter, new government data shows.

Households that are at least 90 days delinquent on their mortgage payment now

number at least 1.6 million, according to a report Thursday issued by the Office

of the Comptroller of the Currency and the Office of Thrift Supervision.

Though more people are in worse trouble, the good news is that fewer households

are entering delinquency. The number of people who were only one payment behind

actually dropped in the quarter by 16,000.

One reason for the ballooning number of seriously delinquent borrowers is that

foreclosure, for better or worse, is becoming an increasingly lengthy process.

Many delinquent borrowers are in trial modifications, which keeps the final

stages of foreclosure at bay.

The number of foreclosures completed in the fourth quarter rose 9 percent, to

128,859. Another 38,000 owners disposed of their house in a short sale, where

the lender agrees to accept less than it is owed.

Starting this month, the Treasury Department is promoting new rules to

facilitate short sales. Borrowers who are trying to sell their house in a short

sale can also put off the endgame for many months.

Both lenders and the Treasury are under pressure to save many of the homeowners

now in foreclosure limbo. Bank of America, the country’s biggest bank, announced

this week that it would forgive principal balances over a period of years on an

initial 45,000 troubled loans.

Lenders began offering principal forgiveness last year on loans they held in

their own portfolios. In the fourth quarter, however, this process abruptly

reversed itself. The number of modifications that included principal reduction

fell by half.

The Treasury is expected to announce soon adjustments to its mortgage

modification plan that will do more to promote principal forgiveness. On

Thursday, it detailed smaller changes to improve the program. Loan servicers are

now required to pre-emptively reach out to borrowers who have missed two

payments and solicit them for a modification.

The quarterly regulators’ report is one of the broadest surveys of loan

performance, covering 34 million first-lien loans. It shows about 4.6 million

borrowers qualify as distressed, ranging from only one payment behind to those

within days of being evicted by the sheriff.

Since the report only covers about two-thirds of American mortgage loans — and

the higher quality loans at that — the actual number of the distressed is about

seven million households.

Households Facing

Foreclosure Rose in 4th Quarter, NYT, 26.3.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/26/business/economy/26mortgages.html

Sales of New Homes Weaken in February

March 24, 2010

The New York Times

By JAVIER C. HERNANDEZ

Sales of new homes weakened to a record low in February,

dimming prospects for a swift recovery for the housing market.

Over all, sales were down 2.2 percent, the Commerce Department said Wednesday,

to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 308,000. Economists had forecast a 1.9

percent rise.

Those numbers followed a similarly bleak report on Tuesday that showed sales of

existing homes dropped in February, despite a generous government tax credit

meant to lure buyers.

Taken together, the bleak data resurrected concerns that the market could fall

into another downturn, with new downward pressure on prices as the supply of

homes increases but demand dwindles.

“It was dismal no matter how one tries to slice and dice it,” Joshua Shapiro, an

economist for MFR Inc. wrote in a research note.

Sales of new homes have now fallen 23 percent since October. Sales rose at a

rapid pace last fall as buyers rushed to take advantage of an $8,000 tax credit

before its original expiration date. The credit has since been extended to April

30, but so far there has been no evidence of a buying frenzy.

Mr. Shapiro said he expected the credit to bolster sales somewhat over the next

several months. But beyond that, the forecast is murkier. Weaning the housing

market from the tax credit “is going to be a difficult process,” he wrote.

The drop in February was partly the result of stronger results the previous

month: the government said sales reached a rate of 315,000 units in January,

better than the 309,000 rate originally forecast. Economists said a series of

snow storms in February may also have contributed to the decline, though they

reiterated that the underlying data was still weak.

A separate report on Wednesday showed businesses continued to ramp up spending

on durable goods in February, raising hopes that a vigorous rebound for

manufacturing may help drive a turnaround for the United States economy.

Orders for long-lasting goods rose 0.5 percent in February, the Commerce

Department said, fueled in part by greater demand from abroad and inventory

restocking.

But a closely watched measure that excludes volatile aircraft and military

orders fell 0.6 percent, suggesting a fast-paced resurgence in orders may be

slowing slightly. Severe winter weather may have also hampered growth,

economists said.

Paul Dales, an economist for Capital Economics in Toronto, said the results were

“further evidence that manufacturers are enjoying a healthy recovery.”

Manufacturing activity has grown briskly since last summer, accompanies by a

steady rise in business confidence. Durable goods orders have increased for

three consecutive months now, and they rose 3.9 percent in January. They were

nearly 8 percent higher than the levels of February 2009.

Economists said that momentum was probably sustainable in the short term, but

could weaken later in the year as government stimulus programs end and

restocking slows.

“Business decision makers, still uncertain about the long-term outlook for

economic growth, are exercising caution with regards to capital spending,” Cliff

Waldman, an economist for the Manufacturers Alliance/MAPI, wrote in a research

note.

A surge in exports has helped prop up orders. The cheap dollar has made American

products more appealing overseas, bolstering demand.

But some sectors continue to lag. Transportation fell 0.7 percent in February

after a drop in car orders. Analysts said that may have been related to Toyota’s

decision to halt production at several plants after widespread concern over the

safety of its vehicles.

Sales of New Homes

Weaken in February, NYT, 24.3.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/25/business/economy/25econ.html

Op-Ed Columnist

The Broken Society

March 19, 2010

The New York Times

By DAVID BROOKS

The United States is becoming a broken society. The public has

contempt for the political class. Public debt is piling up at an astonishing and

unrelenting pace. Middle-class wages have lagged. Unemployment will remain high.

It will take years to fully recover from the financial crisis.

This confluence of crises has produced a surge in vehement libertarianism.

People are disgusted with Washington. The Tea Party movement rallies against big

government, big business and the ruling class in general. Even beyond their

ranks, there is a corrosive cynicism about public action.

But there is another way to respond to these problems that is more communitarian

and less libertarian. This alternative has been explored most fully by the

British writer Phillip Blond.

He grew up in working-class Liverpool. “I lived in the city when it was being

eviscerated,” he told The New Statesman. “It was a beautiful city, one of the

few in Britain to have a genuinely indigenous culture. And that whole way of

life was destroyed.” Industry died. Political power was centralized in London.

Blond argues that over the past generation we have witnessed two revolutions,

both of which liberated the individual and decimated local associations. First,

there was a revolution from the left: a cultural revolution that displaced

traditional manners and mores; a legal revolution that emphasized individual

rights instead of responsibilities; a welfare revolution in which social workers

displaced mutual aid societies and self-organized associations.

Then there was the market revolution from the right. In the age of deregulation,

giant chains like Wal-Mart decimated local shop owners. Global financial markets

took over small banks, so that the local knowledge of a town banker was replaced

by a manic herd of traders thousands of miles away. Unions withered.

The two revolutions talked the language of individual freedom, but they

perversely ended up creating greater centralization. They created an atomized,

segmented society and then the state had to come in and attempt to repair the

damage.

The free-market revolution didn’t create the pluralistic decentralized economy.

It created a centralized financial monoculture, which requires a gigantic

government to audit its activities. The effort to liberate individuals from

repressive social constraints didn’t produce a flowering of freedom; it weakened

families, increased out-of-wedlock births and turned neighbors into strangers.

In Britain, you get a country with rising crime, and, as a result, four million

security cameras.

In a much-discussed essay in Prospect magazine in February 2009, Blond wrote,

“Look at the society we have become: We are a bi-polar nation, a bureaucratic,

centralised state that presides dysfunctionally over an increasingly fragmented,

disempowered and isolated citizenry.” In a separate essay, he added, “The

welfare state and the market state are now two defunct and mutually supporting

failures.”

The task today, he argued in a recent speech, is to revive the sector that the

two revolutions have mutually decimated: “The project of radical transformative

conservatism is nothing less than the restoration and creation of human

association, and the elevation of society and the people who form it to their

proper central and sovereign station.”

Economically, Blond lays out three big areas of reform: remoralize the market,

relocalize the economy and recapitalize the poor. This would mean passing zoning

legislation to give small shopkeepers a shot against the retail giants, reducing

barriers to entry for new businesses, revitalizing local banks, encouraging

employee share ownership, setting up local capital funds so community

associations could invest in local enterprises, rewarding savings, cutting

regulations that socialize risk and privatize profit, and reducing the subsidies

that flow from big government and big business.

To create a civil state, Blond would reduce the power of senior government

officials and widen the discretion of front-line civil servants, the people

actually working in neighborhoods. He would decentralize power, giving more

budget authority to the smallest units of government. He would funnel more

services through charities. He would increase investments in infrastructure, so

that more places could be vibrant economic hubs. He would rebuild the “village

college” so that universities would be more intertwined with the towns around

them.

Essentially, Blond would take a political culture that has been oriented around

individual choice and replace it with one oriented around relationships and

associations. His ideas have made a big splash in Britain over the past year.

His think tank, ResPublica, is influential with the Conservative Party. His

book, “Red Tory,” is coming out soon. He’s on a small U.S. speaking tour,

appearing at Georgetown’s Tocqueville Forum Friday and at Villanova on Monday.

Britain is always going to be more hospitable to communitarian politics than the

more libertarian U.S. But people are social creatures here, too. American

society has been atomized by the twin revolutions here, too. This country, too,

needs a fresh political wind. America, too, is suffering a devastating crisis of

authority. The only way to restore trust is from the local community on up.

The Broken Society,

NYT, 19.3.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/19/opinion/19brooks.html

Junk Bond Avalanche Looms for Credit Markets

March 15, 2010

The New York Times

By NELSON D. SCHWARTZ

When the Mayans envisioned the world coming to an end in 2012

— at least in the Hollywood telling — they didn’t count junk bonds among the

perils that would lead to worldwide disaster.

Maybe they should have, because 2012 also is the beginning of a three-year

period in which more than $700 billion in risky, high-yield corporate debt

begins to come due, an extraordinary surge that some analysts fear could

overload the debt markets.

With huge bills about to hit corporations and the federal government around the

same time, the worry is that some companies will have trouble getting new loans,

spurring defaults and a wave of bankruptcies.

The United States government alone will need to borrow nearly $2 trillion in

2012, to bridge the projected budget deficit for that year and to refinance

existing debt.

Indeed, worries about the growth of national, or sovereign, debt prompted

Moody’s Investors Service to warn on Monday that the United States and other

Western nations were moving “substantially” closer to losing their top-notch Aaa

credit ratings.

Sovereign debt aside, the approaching scramble for corporate financing could

strain the broader economy as jobs are cut, consumer spending is scaled back and

credit is tightened for both consumers and businesses.

The apocalyptic talk is not limited to perpetual bears and the rest of the

doom-and-gloom crowd.

Even Moody’s, which is known for its sober public statements, is sounding the

alarm.

“An avalanche is brewing in 2012 and beyond if companies don’t get out in front

of this,” said Kevin Cassidy, a senior credit officer at Moody’s.

Private equity firms and many nonfinancial companies were able to borrow on easy

terms until the credit crisis hit in 2007, but not until 2012 does the

long-delayed reckoning begin for a series of leveraged buyouts and other deals

that preceded the crisis.

That is because the record number of bonds and loans that were issued to finance

those transactions typically come due in five to seven years, said Diane Vazza,

head of global fixed-income research at Standard & Poor’s.

In addition, she said, many companies whose debt matured in 2009 and 2010 have

been able to extend their loans, but the extra breathing room is only adding to

the bill for 2012 and after.

The result is a potential financial doomsday, or what bond analysts call a

maturity wall. From $21 billion due this year, junk bonds are set to mature at a

rate of $155 billion in 2012, $212 billion in 2013 and $338 billion in 2014.

The credit markets have gradually returned to normal since the financial crisis,

particularly in recent months, making more loans available to companies and

signaling confidence in the pace of economic recovery. But the issue is whether

they can absorb the coming surge in demand for credit.

As was the case with the collapse of the subprime mortgage market three years

ago, derivatives played a big role in the explosion of risky corporate debt. In

this case the culprit was a financial instrument called a collateralized loan

obligation, which helped issuers repackage corporate loans much as subprime

mortgages were sliced, diced and then resold to other investors. That made many

more risky loans available.

“The question is, ‘Should these deals have ever been financed in the first

place?’ ” asked Anders J. Maxwell, a corporate restructuring specialist at Peter

J. Solomon Company in New York.

The period from 2012 to 2014 represents payback time for a Who’s Who of private

equity firms and the now highly leveraged companies they helped buy in the

precrisis boom years.

The biggest include the hospital owner HCA, which was taken private in 2006 by a

group led by Bain Capital and Kohlberg Kravis & Roberts for $33 billion, and has

$13.3 billion in debt payments coming due between 2012 and 2014. Another buyout

led by Kohlberg Kravis, for the giant Texas utility TXU, has $20.9 billion that

needs to be refinanced in the same period.

Realogy, which owns real estate franchises like Century 21 and Coldwell Banker,

was taken private by Apollo in the spring of 2007 just as the housing market was

beginning to unravel and as the first tremors of the subprime crisis were being

felt.

Realogy was saddled with $8 to $9 of debt for every $1 in earnings, well above

the “$5 to $6 level that is manageable for a company in a highly cyclical

industry,” according to Emile Courtney, a credit analyst with Standard & Poor’s.

Realogy has survived — barely. “The company’s cash flow is still below what’s

needed to cover the interest on its debt,” Mr. Courtney said.

Realogy said it ended 2009 with a substantial cushion on its financial covenants

and over $200 million of available cash on its balance sheet. “The company

generated over $340 million of net cash provided by operating activities in 2009

after paying interest on its debt,” the company said.

Not everyone is convinced that 2012 will spell catastrophe for the junk bond

market, however.

Optimists like Martin Fridson, a veteran high-yield strategist, note that

investors seeking high yields snapped up speculative-grade bonds last year and

early this year, and he suggests that continued demand will allow companies to

refinance before their loans come due.

“The companies have nearly two years to push out the 2012 maturity wall,” he

said. “Of course, the ability to refinance will depend upon the state of the

economy.”

That is still a wild card, but even if the economy improves, companies with a

lot of debt will be competing with a raft of better-rated borrowers that are

expected to seek buyers of their debt at around the same time.

Chief among those is the best-rated borrower of all: the United States

government. The Treasury Department estimates that the federal budget deficit in

2012 will total $974 billion, down from this year’s $1.8 trillion, but still

huge by historical standards.

Most critics of deficit spending have focused on the budget gap alone, but

Washington will actually have to borrow $1.8 trillion in 2012, because $859

billion in old bonds will come due and have to be refinanced in addition to the

deficit. By 2013 and 2014, $1.4 trillion will have to be raised annually.

In the late 1990s, the federal government ran a surplus and actually paid down a

small portion of the national debt. But with the huge deficits of the last few

years, the national debt has grown to more than $12 trillion.

Next in line are companies with investment-grade credit ratings. They must

refinance $1.2 trillion in loans between 2012 and 2014, including $526 billion

in 2012. Finally, there is the looming rollover of commercial mortgage-backed

securities, which will double in the next three years, hitting $59.7 billion in

2012.

Even if most of the debt does get refinanced, companies may have to pay more, if

heavy government borrowing causes rates for all borrowers to rise.

“These are huge numbers,” said Tom Atteberry, who manages $5.6 billion in bonds

for First Pacific Advisors, and is particularly alarmed by Washington’s

borrowing. “Other players will get crowded out or have to pay significantly

more, because the government is borrowing so much.”

Junk Bond Avalanche

Looms for Credit Markets, NYT, 16.3.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/16/business/16debt.html

Michael Jackson’s Estate Signs Sweeping Contract

March 16, 2010

The New York Times

By BEN SISARIO

Nine months after Michael Jackson’s death, his estate has

signed one of the biggest recording contracts in history, giving Sony, Mr.

Jackson’s longtime label, the rights to sell his back catalog and draw on a

large vault of unheard recordings.

The deal, for about 10 recordings through 2017, will guarantee the Jackson

estate up to $250 million in advances and other payments and offer an especially

high royalty rate for sales both inside and outside the United States, according

to people with knowledge of the contract who spoke anonymously because they were

not authorized to speak about it publicly.

It also allows Sony and the estate to collaborate on a wide range of lucrative

licensing arrangements, like the use of Jackson music for films, television and

stage shows and lines of memorabilia that will be limited only by the

imagination of the estate and the demand of a hungry worldwide market.

“We think that recordings will always be an important part of the estate,” John

Branca, an entertainment lawyer who is one of the estate’s executors, said in an

interview on Monday. “New generations of kids are discovering Michael.”

“A lot of the people that went to see ‘This Is It’ were families,” he added,

referring to the Jackson concert film released in October. “ ‘This Is It’ was

one of the few films allowed into China. So we think there are growing and

untapped markets for Michael’s music.”

The first recording covered by the new contract is the “This Is It” soundtrack,

released last year, and Sony plans a new album of unreleased recordings for

November.

Sony’s contract is a bet on the continued appeal of Mr. Jackson, whose sales

spiked after his death in June at the age of 50. With overall record sales on a

decade-long plunge, mega-deals like this one have become rare, and Mr. Branca

said the deal “exceeds all previous industry benchmarks.” Five years ago Bruce

Springsteen signed a deal with Sony worth a reported $110 million, and in 2008

Live Nation and Jay-Z struck a $150 million deal for recordings, concert tours

and other rights.

Demand for Jackson music has leveled off after the initial rush — in the weeks

after his death Sony scrambled to replenish retailers’ stock of any and all

Jackson titles — but remains high. Last year Mr. Jackson was the biggest-selling

artist in the United States by a wide margin, with 8.3 million combined album

sales and 12.4 million downloads of single tracks, according to Nielsen

SoundScan. Mr. Branca said that since his death Mr. Jackson has sold more than

31 million albums, about two-thirds of them outside the United States.

But as record sales have tapered off over the last decade, licensing has emerged

as the biggest growth area for revenue from recorded music. And given the

success of the Beatles and the Elvis Presley estate in reissuing and repackaging

old albums as well as finding new uses for their music — like “Love,” the

Beatles’ hit theatrical show by Cirque du Soleil — it is not hard to imagine the

direction that the Jackson estate might take in using old recordings in new

ways.

“It’s not just a record deal,” said Rob Stringer, chairman of the Columbia/Epic

Label Group, a Sony division. “We’re not just basing this on how many CDs we

sell or how many downloads. There are also audio rights for theater, movies,

computer games. I don’t know how an audio soundtrack will be used in 2017, but

you’ve got to bet on Michael Jackson in any new platform.”

Michael Jackson’s

Estate Signs Sweeping Contract, NYT, 16.3.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/16/arts/music/16jackson.html

China’s Exports Rise 46%

March 10, 2010

The New York Times

By SHARON LAFRANIERE

BEIJING —China announced Wednesday that its exports climbed 46

percent in February from a year earlier. Economists said the data signaled a

rebound in consumer demand from the United States and other Western markets

after the financial crisis last year.

It was the third consecutive month of increases in Chinese exports and the

fastest growth in three years. Orders from the United States, the European Union

and Japan accounted for almost half the growth, following a pickup in demand

from emerging markets in the previous two months.

Chinese imports also rose 45 percent over the previous year, led by crude oil as

factories stepped up production.

Some economists said the figures indicated China’s recovery was well under way.

Tao Wang, head of China research for UBS Securities, predicted that Chinese

exports would rebound to the level of 2008 before China took a big hit from the

global financial crisis.

She and others suggested that the robust growth could increase pressure on China

to let its currency, the renminbi, appreciate against the U.S. dollar.

Western governments contend the peg to the dollar keeps Chinese exports

artificially cheap and depresses competing economies. The Chinese prime

minister, Wen Jiabao, said last week that exchange rates would remain “basically

stable” for now.

Commerce Minister Chen Deming said in late December that the outlook for

international trade remained “extremely complicated” and predicted that it could

take two or three years for Chinese exports to recover to precrisis levels. A

Commerce Ministry spokesman repeated that prediction late last month.

But some analysts saw a hint of a possible shift in policy in comments made

Saturday by the central bank governor, Zhou Xiaochuan. He called pegging the

renminbi to the U.S. dollar a “special foreign exchange mechanism” that would be

abandoned “sooner or later.”

February figures are harder to interpret than those for other months because of

China’s holiday break, which occurs early every year but not on the same date.

Moreover, the comparison with the previous year could be somewhat misleading

because February 2009 was a particularly bleak month for Chinese exports and

imports.

Nonetheless, Moody’s Economy.com, an economic research organization, said the

data “reflects the dramatic improvement in the trade sector” over a year ago.

Other economists said the figures suggested the outlook of the Chinese Commerce

Ministry was too pessimistic.

The 46 percent increase in exports beat economists’ predictions and the January

increase of 21 percent. Exports of textiles, steel products, televisions and

motorcycles also rose. In China’s industrial heartland, some factories are

reporting labor shortages as they strive to fill orders.

The pace of growth in imports slowed from January, when China reported an 85

percent increase. Economists attributed that largely to rising prices.

China reported a $7.6 billion trade surplus for the month. The trade surplus for

January through February shrank by half compared to a year ago, according to Ms.

Wang, of UBS. She said the smaller surplus was probably temporary, because of

the rising prices of commodities. She predicted a modest drop in the trade

surplus for the year.

Separately, others figures from the National Bureau of Statistics also released

Wednesday showed the economy was humming along. Investment in real estate rose

31.1 percent in the first two months of the year, compared with a year earlier,

Reuters reported.

China unveiled strict new rules Wednesday governing bankers’ pay that are

designed to limit risk taking, Reuters reported from Beijing.

Payment of 40 percent or more of an executive’s salary must be delayed for a

minimum of three years and could be withheld if the bank performs poorly, the

China Banking Regulatory Commission said in a statement on its Web site.

This would ostensibly put China at the forefront of a global movement to use

regulation of bankers’ pay as a way to control investment behavior. The

implications in China are less significant, however, because bankers are, in

effect, employees of the government in the largely state-owned banking system

and their salaries are already significantly lower than those of international

peers.

Zhang Jing contributed research.

China’s Exports Rise

46%, NYT, 11.3.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/11/business/global/11yuan.html

Editorial

As Foreclosures Continue ...

March 1, 2010

The New York Times

President Obama went to Henderson, Nev., the other day to show

Americans that he was responding to the cries for help from struggling

homeowners (and maybe give a boost to Senator Harry Reid’s re-election). He

announced a $1.5 billion effort to prevent foreclosures in five states hard-hit

by the housing bust — Nevada, Arizona, California, Florida and Michigan — by

feeding money into programs that would be developed and carried out by the

housing agencies in the targeted states.

The audience in Henderson applauded the announcement, and understandably so. In

Nevada, unemployment is 13 percent and 70 percent of homeowners with mortgages

owe more on their homes than they are worth; in industry parlance, they are

“underwater.” Since a combination of joblessness and underwater loans is the

main driver of foreclosure, Nevadans are clearly at high risk of losing their

homes, as are homeowners in the other four states.

So it was good to see Mr. Obama focusing aid where it is needed most. But two

big concerns remain. First, the new plan must be implemented quickly and

efficiently for it to be more than a public relations ploy, and as yet there is

no timetable. More broadly, it is still not clear whether the administration

realizes that the importance of the plan lies not just in what it might do for a

handful of states but in the direction it should set nationally.

The administration’s $75 billion antiforeclosure program, which subsidizes

lenders to rework bad loans, has been a big disappointment. One reason is that

its usual method of modifying loans — lowering the monthly payment by reducing

the interest rate — does not work well for jobless and underwater borrowers.

Unemployed homeowners often cannot make even reduced payments and underwater

borrowers need principal reductions to succeed over the long run, not lower

rates.

And yet, the administration has resisted calls to revamp its program, citing

cost and complexity. Another obstacle is that banks are generally loath to

modify loans by reducing principal, which would require them to take big upfront

losses that they would prefer to postpone.

In at least a tacit acknowledgment of those issues, Mr. Obama specifically said

that the five-state effort is intended to aid homeowners who are out of work and

underwater. To help jobless owners, states could use the money for loans to

cover mortgage payments, an approach used successfully in Pennsylvania. With

unemployment expected to remain high for a long time, Mr. Obama should consider

a national program of that kind.

It is less clear how the new fund would help underwater borrowers. Why would

states be successful in negotiating principal reductions when the administration

has not been able to persuade or compel the banks to do them? Still, now that

Mr. Obama has set the aim of helping underwater borrowers, it is up to the

administration — by working with states or by revamping its own efforts — to

make it happen. The banks won’t like it. But the alternative is more

foreclosures, further price declines and — as the housing market continues to

wobble — an endangered economic recovery.

By itself, Mr. Obama’s new plan for Nevada and the other states is too small to

make a meaningful dent in foreclosures. But by aiming to help unemployed and

underwater borrowers, it is headed in the right direction, if the administration

is willing to set a new course.

As Foreclosures

Continue ..., NYT, 1.3.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/01/opinion/01mon1.html

Bernanke Forecasts Long Period of Low Interest Rates

February 25, 2010

The New York Times

By SEWELL CHAN

WASHINGTON — Ben S. Bernanke, the Federal Reserve chairman,

signaled on Wednesday that he did not plan to begin raising interest rates

anytime soon, saying the economic recovery would remain halting for months to

come.

In presenting the Fed’s semiannual monetary report to Congress, Mr. Bernanke did

not waver from the Jan. 27 statement of the central bank’s key policy making

board, or from a Feb. 10 statement in which he explained to Congress the

strategies for gradually reducing the vast sums that banks hold in reserves at

the Fed.

“Although the federal funds rate is likely to remain exceptionally low for an

extended period, as the expansion matures, the Federal Reserve will at some

point need to begin to tighten monetary conditions to prevent the development of

inflationary pressures,” Mr. Bernanke said in a prepared statement.

While Mr. Bernanke did not change his outlook on interest rates or the economy,

he did announce two significant steps to improve transparency and accountability

of the Fed, after a period in which the central bank has faced considerable

criticism.

Significantly, Mr. Bernanke said that the Fed would “support legislation that

would require the release” of the names of borrowers that used the extraordinary

lending programs the Fed created in 2008 to prop up the markets for commercial

paper, money market funds and even consumer loans. The Fed lent to investment

banks for the first time and helped arrange the sale of the investment bank Bear

Stearns and the rescues of the American International Group and Citigroup.

“While the emergency credit and liquidity facilities were important tools for

implementing monetary policy during the crisis, we understand that the unusual

nature of those facilities creates a special obligation to assure the Congress

and the public of the integrity of their operations,” Mr. Bernanke said.

He said the release should not occur until a “lag that is sufficiently long” to

avoid creating the impression that the borrower still faces financial problems,

undermine market confidence or discourage future borrowing. Mr. Bernanke also

said he would support audits by the Government Accountability Office of how the

lending programs were conducted.

In his testimony, Mr. Bernanke predicted that the recovery would be slow. Much

of the pickup in growth late last year, he said, could be attributed to

companies reducing unwanted inventories of unsold goods, making them more

willing to bolster production.

“As the impetus provided by the inventory cycle is temporary, and as the fiscal

support for economic growth likely will diminish later this year, a sustained

recovery will depend on continued growth in private-sector final demand for

goods and services,” he said.

Mr. Bernanke’s prepared testimony, which accompanied the Fed’s 53-page monetary

policy report, did not contain many surprises. Observers were more interested in

what he would tell members of the House Financial Services Committee under

questioning.

In his testimony, Mr. Bernanke said consumer demand seemed to be “growing at a

moderate pace,” notably business investment in equipment and software and in a

rebound of international trade. Housing starts, however, have been flat, and

despite recent signs that job losses have slowed, the “job market remains quite

weak.”

As the hearing commenced, the committee chairman, Representative Barney Frank of

Massachusetts, allowed various members to air their views.

Representative Ron Paul, the Texas Republican and persistent libertarian critic

of the Fed — he favors something like a return to the gold standard — said the

Fed continued to create “moral hazard” by allowing companies to take risks

because they believe they will be bailed out if they fail.

“ ‘Too big to fail’ creates a tremendous moral hazard,” he said, “but of course

the real moral hazard over the many decades has been the deception put into the

markets by the Federal Reserve.”

After Mr. Paul suggested that money used in the 1972 Watergate break-in came

from the Federal Reserve, and that the Fed had loaned $5.5 billion to the regime

of Saddam Hussein of Iraq, Mr. Bernanke replied, “The specific allegations you

have made are absolutely bizarre. I have no knowledge of anything remotely like

what you’ve described.”

And when Mr. Paul asked whether the Fed would bail out the Greek government, Mr.

Bernanke replied, “We have no plans whatsoever to be involved in any foreign

bailouts or anything of that sort.”

Under questioning, Mr. Bernanke tried his best not to take a side in the

Congressional debates over how best to help the economy despite the huge

deficits.

“Obviously unemployment is the biggest problem that we have,” Mr. Bernanke told

Mr. Frank. “If the Federal Reserve and the Congress can address that issue, we

need to address that issue, but there are difficult trade-offs.”

But he added: “There are real long-term budget problems which need to be

addressed.”

In response to Representative Spencer T. Bachus of Alabama, the senior

Republican on the committee, Mr. Bernanke conceded that the long-term growth in

the debt and deficit was not sustainable. “In order to maintain a stable ratio

of debt-to-G.D.P., you need to have a deficit that’s 2.5 to 3 percent at most,

so yes, under current projections, we have a deficit, debt, that will continue

to grow, interest-rate costs that will continue to grow,” he said.

A plan to bring the nation’s fiscal house in order, he said, would be “very

helpful — even to the current recovery, to markets, to confidence.”

The only topic that lawmakers from both parties persistently raised with Mr.

Bernanke was the state of the commercial real estate market, and in particular

the challenges small businesses are having in obtaining loans.

“We know that small-business lending is closely tied to job creation,” Mr.

Bernanke told Representative Melvin L. Watt, Democrat of North Carolina. “We

know that there are problems with bank lending to small businesses.”

And he told Representative Nydia M. Velazquez, Democrat of New York: “The real

concern at this point is that the fundamentals for hotels and office buildings

and malls and so on are quite weak. That’s why the loans are going bad. Really

the only solution there is first to strengthen the economy overall and second,

to help the banks deal with those problems, work them out.”

Bernanke Forecasts

Long Period of Low Interest Rates, NYT, 28.2.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/25/business/economy/25fed.html

The New Poor

Millions of Unemployed Face Years Without Jobs

February 21, 2010

The New York Times

By PETER S. GOODMAN

BUENA PARK, Calif. — Even as the American economy shows

tentative signs of a rebound, the human toll of the recession continues to

mount, with millions of Americans remaining out of work, out of savings and

nearing the end of their unemployment benefits.

Economists fear that the nascent recovery will leave more people behind than in

past recessions, failing to create jobs in sufficient numbers to absorb the

record-setting ranks of the long-term unemployed.

Call them the new poor: people long accustomed to the comforts of middle-class

life who are now relying on public assistance for the first time in their lives

— potentially for years to come.

Yet the social safety net is already showing severe strains. Roughly 2.7 million

jobless people will lose their unemployment check before the end of April unless

Congress approves the Obama administration’s proposal to extend the payments,

according to the Labor Department.

Here in Southern California, Jean Eisen has been without work since she lost her

job selling beauty salon equipment more than two years ago. In the several

months she has endured with neither a paycheck nor an unemployment check, she

has relied on local food banks for her groceries.

She has learned to live without the prescription medications she is supposed to

take for high blood pressure and cholesterol. She has become effusively

religious — an unexpected turn for this onetime standup comic with X-rated

material — finding in Christianity her only form of health insurance.

“I pray for healing,” says Ms. Eisen, 57. “When you’ve got nothing, you’ve got

to go with what you know.”

Warm, outgoing and prone to the positive, Ms. Eisen has worked much of her life.

Now, she is one of 6.3 million Americans who have been unemployed for six months

or longer, the largest number since the government began keeping track in 1948.

That is more than double the toll in the next-worst period, in the early 1980s.

Men have suffered the largest numbers of job losses in this recession. But Ms.

Eisen has the unfortunate distinction of being among a group — women from 45 to

64 years of age — whose long-term unemployment rate has grown rapidly.

In 1983, after a deep recession, women in that range made up only 7 percent of

those who had been out of work for six months or longer, according to the Labor

Department. Last year, they made up 14 percent.

Twice, Ms. Eisen exhausted her unemployment benefits before her check was

restored by a federal extension. Last week, her check ran out again. She and her

husband now settle their bills with only his $1,595 monthly disability check.

The rent on their apartment is $1,380.

“We’re looking at the very real possibility of being homeless,” she said.

Every downturn pushes some people out of the middle class before the economy

resumes expanding. Most recover. Many prosper. But some economists worry that

this time could be different. An unusual constellation of forces — some embedded

in the modern-day economy, others unique to this wrenching recession — might

make it especially difficult for those out of work to find their way back to

their middle-class lives.

Labor experts say the economy needs 100,000 new jobs a month just to absorb

entrants to the labor force. With more than 15 million people officially

jobless, even a vigorous recovery is likely to leave an enormous number out of

work for years.

Some labor experts note that severe economic downturns are generally followed by

powerful expansions, suggesting that aggressive hiring will soon resume. But

doubts remain about whether such hiring can last long enough to absorb anywhere

close to the millions of unemployed.

A New Scarcity of Jobs

Some labor experts say the basic functioning of the American economy has changed

in ways that make jobs scarce — particularly for older, less-educated people

like Ms. Eisen, who has only a high school diploma.

Large companies are increasingly owned by institutional investors who crave

swift profits, a feat often achieved by cutting payroll. The declining influence

of unions has made it easier for employers to shift work to part-time and

temporary employees. Factory work and even white-collar jobs have moved in

recent years to low-cost countries in Asia and Latin America. Automation has

helped manufacturing cut 5.6 million jobs since 2000 — the sort of jobs that

once provided lower-skilled workers with middle-class paychecks.

“American business is about maximizing shareholder value,” said Allen Sinai,

chief global economist at the research firm Decision Economics. “You basically

don’t want workers. You hire less, and you try to find capital equipment to

replace them.”

During periods of American economic expansion in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, the

number of private-sector jobs increased about 3.5 percent a year, according to

an analysis of Labor Department data by Lakshman Achuthan, managing director of

the Economic Cycle Research Institute, a research firm. During expansions in the

1980s and ’90s, jobs grew just 2.4 percent annually. And during the last decade,

job growth fell to 0.9 percent annually.

“The pace of job growth has been getting weaker in each expansion,” Mr. Achuthan

said. “There is no indication that this pattern is about to change.”

Before 1990, it took an average of 21 months for the economy to regain the jobs

shed during a recession, according to an analysis of Labor Department data by

the National Employment Law Project and the Economic Policy Institute, a

labor-oriented research group in Washington.

After the recessions in 1990 and in 2001, 31 and 46 months passed before

employment returned to its previous peaks. The economy was growing, but

companies remained conservative in their hiring.

Some 34 million people were hired into new and existing private-sector jobs in

2000, at the tail end of an expansion, according to Labor Department data. A

year later, in the midst of recession, hiring had fallen off to 31.6 million.

And as late as 2003, with the economy again growing, hiring in the private

sector continued to slip, to 29.8 million.

It was a jobless recovery: Business was picking up, but it simply did not

translate into more work. This time, hiring may be especially subdued, labor

economists say.

Traditionally, three sectors have led the way out of recession: automobiles,

home building and banking. But auto companies have been shrinking because

strapped households have less buying power. Home building is limited by fears

about a glut of foreclosed properties. Banking is expanding, but this seems

largely a function of government support that is being withdrawn.

At the same time, the continued bite of the financial crisis has crimped the

flow of money to small businesses and new ventures, which tend to be major

sources of new jobs.

All of which helps explain why Ms. Eisen — who has never before struggled to

find work — feels a familiar pain each time she scans job listings on her

computer: There are positions in health care, most requiring experience she

lacks. Office jobs demand familiarity with software she has never used. Jobs at

fast food restaurants are mostly secured by young people and immigrants.

If, as Mr. Sinai expects, the economy again expands without adding many jobs,

millions of people like Ms. Eisen will be dependent on an unemployment insurance

already being severely tested.

“The system was ill prepared for the reality of long-term unemployment,” said

Maurice Emsellem, a policy director for the National Employment Law Project.

“Now, you add a severe recession, and you have created a crisis of historic

proportions.”

Fewer Protections

Some poverty experts say the broader social safety net is not up to cushioning

the impact of the worst downturn since the Great Depression. Social services are

less extensive than during the last period of double-digit unemployment, in the

early 1980s.

On average, only two-thirds of unemployed people received state-provided

unemployment checks last year, according to the Labor Department. The rest

either exhausted their benefits, fell short of requirements or did not apply.

“You have very large sets of people who have no social protections,” said Randy

Albelda, an economist at the University of Massachusetts in Boston. “They are

landing in this netherworld.”

When Ms. Eisen and her husband, Jeff, applied for food stamps, they were turned

away for having too much monthly income. The cutoff was $1,570 a month — $25

less than her husband’s disability check.

Reforms in the mid-1990s imposed time limits on cash assistance for poor single

mothers, a change predicated on the assumption that women would trade welfare

checks for paychecks.

Yet as jobs have become harder to get, so has welfare: as of 2006, 44 states cut

off anyone with a household income totaling 75 percent of the poverty level —

then limited to $1,383 a month for a family of three — according to an analysis

by Ms. Albelda.

“We have a work-based safety net without any work,” said Timothy M. Smeeding,

director of the Institute for Research on Poverty at the University of

Wisconsin, Madison. “People with more education and skills will probably figure

something out once the economy picks up. It’s the ones with less education and

skills: that’s the new poor.”

Here in Orange County, the expanse of suburbia stretching south from Los

Angeles, long-term unemployment reaches even those who once had six-figure

salaries. A center of the national mortgage industry, the area prospered in the

real estate boom and suffered with the bust.

Until she was laid off two years ago, Janine Booth, 41, brought home roughly

$10,000 a month in commissions from her job selling electronics to retailers. A

single mother of three, she has been living lately on $2,000 a month in child

support and about $450 a week in unemployment insurance — a stream of checks

that ran out last week.

For Ms. Booth, work has been a constant since her teenage years, when she

cleaned houses under pressure from her mother to earn pocket money. Today, Ms.

Booth pays her $1,500 monthly mortgage with help from her mother, who is herself

living off savings after being laid off.

“I don’t want to take money from her,” Ms. Booth said. “I just want to find a

job.”

Ms. Booth, with a résumé full of well-paid sales jobs, seems the sort of person

who would have little difficulty getting work. Yet two years of looking have

yielded little but anxiety.

She sends out dozens of résumés a week and rarely hears back. She responds to

online ads, only to learn they are seeking operators for telephone sex lines or

people willing to send mysterious packages from their homes.

She spends weekdays in a classroom in Anaheim, in a state-financed training

program that is supposed to land her a job in medical administration. Even if

she does find a job, she will be lucky if it pays $15 an hour.

“What is going to happen?” she asked plaintively. “I worry about my kids. I just

don’t want them to think I’m a failure.”

On a recent weekend, she was running errands with her 18-year-old son when they

stopped at an A.T.M. and he saw her checking account balance: $50.

“He says, ‘Is that all you have?’ ” she recalled. “ ‘Are we going to be O.K.?’ ”

Yes, she replied — and not only for his benefit.

“I have to keep telling myself it’s going to be O.K.,” she said. “Otherwise, I’d

go into a deep depression.”

Last week, she made up fliers advertising her eagerness to clean houses — the

same activity that provided her with spending money in high school, and now the

only way she sees fit to provide for her kids. She plans to place the fliers on

porches in some other neighborhood.

“I don’t want to clean my neighbors’ houses,” she said. “I know I’m going to

come out of this. There’s no way I’m going to be homeless and poverty-stricken.

But I am scared. I have a lot of sleepless nights.”

For the Eisens, poverty is already here. In the two years Ms. Eisen has been

without work, they have exhausted their savings of about $24,000. Their credit

card balances have grown to $15,000.

“I don’t know how we’re still indoors,” she said.

Her 1994 Dodge Caravan broke down in January, leaving her to ask for rides to an

employment center.

She does not have the money to move to a cheaper apartment.

“You have to have money for first and last month’s rent, and to open utility

accounts,” she said.

What she has is personality and presence — two traits that used to seem enough.

She narrates her life in a stream of self-deprecating wisecracks, her punch

lines tinged with desperation.

“See that,” she said, spotting a man dressed as the Statue of Liberty. Standing

on a sidewalk, he waved at passing cars with a sign advertising a tax

preparation business. “That will be me next week. Do you think this guy ever

thought he’d be doing this?”

And yet, she would gladly do this. She would do nearly anything.

“There are no bad jobs now,” she says. “Any job is a good job.”

She has applied everywhere she can think of — at offices, at gas stations.

Nothing.

“I’m being seen as a person who is no longer viable,” she said. “I’m chalking it

up to my age and my weight. Blame it on your most prominent insecurity.”

Two Incomes, Then None

Ms. Eisen grew up poor, in Flatbush in Brooklyn. Her father was in maintenance.

Her mother worked part time at a company that made window blinds.

She married Jeff when she was 19, and they soon moved to California, where he

had grown up. He worked in sales for a chemical company. They rented an

apartment in Buena Park, a growing spread of houses filling out former orange

groves. She stayed home and took care of their daughter.

“I never asked him how much he earned,” Ms. Eisen said. “I was of the mentality

that the husband took care of everything. But we never wanted.”

By the early 1980s, gas and rent strained their finances. So she took a job as a

quality assurance clerk at a factory that made aircraft parts. It paid $13.50 an

hour and had health insurance.

When the company moved to Mexico in the early 1990s, Ms. Eisen quickly found a

job at a travel agency. When online booking killed that business, she got the

job at the beauty salon equipment company. It paid $13.25 an hour, with an

annual bonus — enough for presents under the Christmas tree.

But six years ago, her husband took a fall at work and then succumbed to various

ailments — diabetes, liver disease, high blood pressure — leaving him confined

to the couch. Not until 2008 did he secure his disability check.

And now they find themselves in this desert of joblessness, her paycheck

replaced by a $702 unemployment check every other week. She received 14 weeks of

benefits after she lost her job, and then a seven-week extension.

For most of October through December 2008, she received nothing, as she waited

for another extension. The checks came again, then ran out in September 2009.

They were restored by an extension right before Christmas.

Their daughter has back problems and is living on disability checks, making the

church their ultimate safety net.

“I never thought I’d be in the position where I had to go to a food bank,” Ms.

Eisen said. But there she is, standing in the parking lot of the Calvary Chapel

church, chatting with a half-dozen women, all waiting to enter the Bread of Life

Food Pantry.

When her name is called, she steps into a windowless alcove, where a smiling

woman hands her three bags of groceries: carrots, potatoes, bread, cheese and a

hunk of frozen meat.

“Haven’t we got a lot to be thankful for?” Ms. Eisen asks.

For one thing, no pinto beans.

“I’ve got 10 bags of pinto beans,” she says. “And I have no clue how to cook a

pinto bean.”

Local job listings are just as mysterious. On a bulletin board at the

county-financed ProPath Business and Career Services Center, many are written in

jargon hinting of accounting or computers.

“Nothing I’m qualified for,” Ms. Eisen says. “When you can’t define what it is,

that’s a pretty good indication.”

Her counselor has a couple of possibilities — a cashier at a supermarket and a

night desk job at a motel.

“I’ll e-mail them,” Ms. Eisen promises. “I’ll tell them what a shining example

of humanity I am.”

Millions of

Unemployed Face Years Without Jobs, NYT, 20.2.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/21/business/economy/21unemployed.html

Data Ease Fear of Inflation, Despite Higher Energy Costs

February 20, 2010

The New York Times

By JAVIER C. HERNANDEZ

Prices for consumers in the United States inched upward in

January, but the increase was slight, easing some of the concerns about

inflation as economy slowly recovers.

The price of a variety of goods, everything from rent to cigarettes, rose 0.2

percent in January. Excluding food and fuel costs, which tend to be volatile,

prices fell 0.1 percent — the first decrease since 1982.

The Labor Department attributed much of the increase in its Consumer Price Index

to rising energy costs — namely gasoline, fuel oil and natural gas. A decrease

in the price of rent, new cars and airline tickets helped offset the jump in

energy prices.

Economists said the results indicated that businesses were keeping prices low in

an effort to lure price-conscious customers.

“People are very much price-sensitive, they are still paying down their debts,

not taking that vacation, not buying that extra item of apparel,” said Anna

Piretti, senior economist for BNP Paribas. “That is going to be the theme for

some time. Prospects for employment are not looking very bright.”

Thursday’s report on jobless filings, in fact, rekindled worries that the labor

market would be slow to bounce back. First-time unemployment claims last week

were much higher than expected — 473,000, up 31,000 from the previous week.

Economists also said that Friday’s consumer price index indicated that the

government’s decision to pump billions into the economy has yet to translate

into inflation, which should help ease concerns that the Federal Reserve could

raise its benchmark rate any time soon.

The results beat Wall Street forecasts, and shortly after their release, stocks

pared some of their losses in after-hours trading.

On Thursday, the government offered a similar portrait in its report on producer

prices, which rose 1.4 percent in January. There were indications, however, that

higher prices may be in the pipeline, especially for metals, food and energy

products.

Still, while fuel and food costs may continue to rise, many economists do not

see higher prices as a threat in the near term, though they say inflation could

become an issue in the next several years.

The Federal Reserve, which has kept interest rates at historic lows to stimulate

lending, is not expected to raise the crucial federal funds rate for at least

six months. The central bank has begun to take steps to normalize lending,

however, and on Thursday it announced it would raise the interest rate it

charges on short-term loans to banks, known as the discount rate.

It remains to be seen whether businesses can afford to pass their rising costs

down to consumers. But if they do not pass along those price increases, analysts

said, that may worsen their own financial health and prolong unemployment.

“If producers see their profits being hurt they will be more reluctant to hire,”

Ms. Piretti said. “It’s a circle.”

Data Ease Fear of Inflation, Despite Higher

Energy Costs, NYT, 19.1.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/20/business/economy/20econ.html

In a Message to Democrats, Wall St. Sends Cash to G.O.P.

February 8, 2010

The New York Times

By DAVID D. KIRKPATRICK

WASHINGTON — If the Democratic Party has a stronghold on Wall

Street, it is JPMorgan Chase.

Its chief executive, Jamie Dimon, is a friend of President Obama’s from Chicago,

a frequent White House guest and a big Democratic donor. Its vice chairman,

William M. Daley, a former Clinton administration cabinet official and Obama

transition adviser, comes from Chicago’s Democratic dynasty.

But this year Chase’s political action committee is sending the Democrats a

pointed message. While it has contributed to some individual Democrats and state

organizations, it has rebuffed solicitations from the national Democratic House

and Senate campaign committees. Instead, it gave $30,000 to their Republican

counterparts.

The shift reflects the hard political edge to the industry’s campaign to thwart

Mr. Obama’s proposals for tighter financial regulations.

Just two years after Mr. Obama helped his party pull in record Wall Street

contributions — $89 million from the securities and investment business,

according to the nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics — some of his

biggest supporters, like Mr. Dimon, have become the industry’s chief lobbyists

against his regulatory agenda.

Republicans are rushing to capitalize on what they call Wall Street’s “buyer’s

remorse” with the Democrats. And industry executives and lobbyists are warning

Democrats that if Mr. Obama keeps attacking Wall Street “fat cats,” they may

fight back by withholding their cash.

“If the president doesn’t become a little more balanced and centrist in his

approach, then he will likely lose that support,” said Kelly S. King, the

chairman and chief executive of BB&T. Mr. King is a board member of the

Financial Services Roundtable, which lobbies for the biggest banks, and last

month he helped represent the industry at a private dinner at the Treasury

Department.

“I understand the public outcry,” he continued. “We have a 17 percent real

unemployment rate, people are hurting, and they want to see punishment. But the

political rhetoric just incites more animosity and gets people riled up.”

A spokesman for JPMorgan Chase declined to comment on its political action

committee’s contributions or relations with the Democrats. But many Wall Street

lobbyists and executives said they, too, were rethinking their giving.

“The expectation in Washington is that ‘We can kick you around, and you are

still going to give us money,’ ” said a top official at a major Wall Street

firm, speaking on the condition of anonymity for fear of alienating the White

House. “We are not going to play that game anymore.”

Wall Street fund-raisers for the Democrats say they are feeling under attack

from all sides. The president is lashing out at their “arrogance and greed.”

Republican friends are saying “I told you so.” And contributors are wishing they

had their money back.

“I am a big fan of the president,” said Thomas R. Nides, a prominent Democrat

who is also a Morgan Stanley executive and chairman of a major Wall Street trade

group, the Securities and Financial Markets Association. “But even if you are a

big fan, when you are the piñata at the party, it doesn’t really feel good.”

Roger C. Altman, a former Clinton administration Treasury official who founded

the Wall Street boutique Evercore Partners, called the Wall Street backlash

against Mr. Obama “a constant topic of conversation.” Many bankers, he said,

failed to appreciate the “white hot anger” at Wall Street for the financial

crisis. (Mr. Altman said he personally supported “the substance” of the

president’s recent proposals, though he questioned their feasibility and

declined to comment at all on what he called “the rhetoric.”)

Mr. Obama’s fight with Wall Street began last year with his proposals for

greater oversight of compensation and a consumer financial protection

commission. It escalated with verbal attacks this year on what he called Wall

Street’s “obscene bonuses.” And it reached a new level in his calls for policies

Wall Street finds even more infuriating: a “financial crisis responsibility” tax

aimed only at the biggest banks, and a restriction on “proprietary trading” that

banks do with their own money for their own profit.

“If the president wanted to turn every Democrat on Wall Street into a

Republican,” one industry lobbyist said, “he is doing everything right.”

Though Wall Street has long been a major source of Democratic campaign money

(alongside Hollywood and Silicon Valley), Mr. Obama built unusually direct ties

to his contributors there. He is the first president since Richard M. Nixon

whose campaign relied solely on private donations, not public financing.

Wall Street lobbyists say the financial industry’s big Democratic donors help

ensure that their arguments reach the ears of the president and Congress. White

House visitors’ logs show dozens of meetings with big Wall Street fund-raisers,

including Gary D. Cohn, a president of Goldman Sachs; Mr. Dimon of JPMorgan

Chase; and Robert Wolf, the chief of the American division of the Swiss bank

UBS, who has also played golf, had lunch and watched July 4 fireworks with the

president.

Lobbyists say they routinely brief top executives on policy talking points

before they meet with the president or others in the administration. Mr. Wolf,

in particular, also serves on the Presidential Economic Recovery Advisory Board

led by the former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul A. Volcker.

Mr. Wolf was the only Wall Street executive on the panel and became the board’s

leading opponent of what became known as the Volcker rule against so-called

proprietary trading, according to participants. Such trading did nothing to

cause the crisis, Mr. Wolf argued, as the industry lobbyists do now. (The panel

concluded that the crisis established a precedent for government rescue that

could enable big banks to speculate for their own gain while taxpayers took the

biggest risks.)

Mr. Wolf and Mr. Dimon, who was in Washington last week for meetings on Capitol

Hill and lunch with the president, have both pressed the industry’s arguments

against other proposed regulations and the bank tax as well — saying the rules

could cramp needed lending and send business abroad, according to lobbyists.

Both men are said to remain personally supportive of the president. But UBS’s

political action committee has shifted its contributions, according to the

Center for Responsive Politics. After dividing its money evenly between the

parties for 2008, it has given about 56 percent to Republicans this cycle.

Most of its biggest contributions, of $10,000 each, went to five Republican

opponents of Mr. Obama’s regulatory proposals, including Senator Richard C.

Shelby of Alabama, the ranking minority member of the Banking Committee.

The Democratic campaign committees declined to comment on Wall Street money. But

their Republican rivals are actively courting it.

Senator John Cornyn of Texas, chairman of the National Republican Senatorial

Committee, said he visited New York about twice a month to try to tap into Wall

Street’s “buyers’ remorse.”

“I just don’t know how long you can expect people to contribute money to a

political party whose main plank of their platform is to punish you,” Mr. Cornyn

said.

In a Message to

Democrats, Wall St. Sends Cash to G.O.P., 13.2.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/08/us/politics/08lobby.html

The Safety Net

Once Stigmatized, Food Stamps Find New Acceptance

February 11, 2010

The New York Times

By JASON DEPARLE and ROBERT GEBELOFF

A decade ago, New York City officials were so reluctant to

give out food stamps, they made people register one day and return the next just

to get an application. The welfare commissioner said the program caused

dependency and the poor were “better off” without it.

Now the city urges the needy to seek aid (in languages from Albanian to

Yiddish). Neighborhood groups recruit clients at churches and grocery stores,

with materials that all but proclaim a civic duty to apply — to “help New York

farmers, grocers, and businesses.” There is even a program on Rikers Island to

enroll inmates leaving the jail.

“Applying for food stamps is easier than ever,” city posters say.

The same is true nationwide. After a U-turn in the politics of poverty, food

stamps, a program once scorned as “welfare,” enjoys broad new support. Following

deep cuts in the 1990s, Congress reversed course to expand eligibility, cut red

tape and burnish the program’s image, with a special effort to enroll the

working poor. These changes, combined with soaring unemployment, have pushed