|

USA > History > 2010 > Education (I)

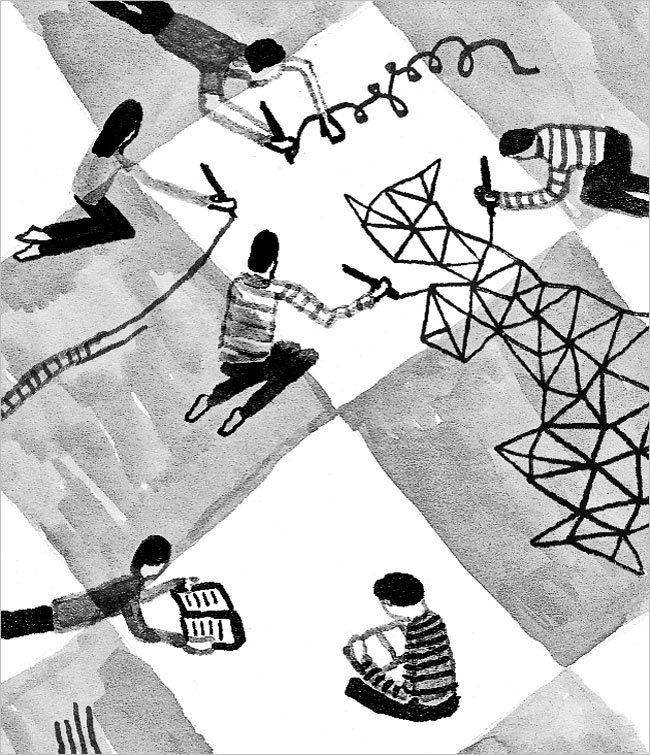

Illustration: Eleanor Rudge

Using Talk and Play to Develop Minds

NYT

8.2.2010

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/08/opinion/l08teach.html

Serious Mental Health

Needs Seen Growing at Colleges

December 19, 2010

The New York Times

By TRIP GABRIEL

STONY BROOK, N.Y. — Rushing a student to a psychiatric emergency room is

never routine, but when Stony Brook University logged three trips in three days,

it did not surprise Jenny Hwang, the director of counseling.

It was deep into the fall semester, a time of mounting stress with finals

looming and the holiday break not far off, an anxiety all its own.

On a Thursday afternoon, a freshman who had been scraping bottom academically

posted thoughts about suicide on Facebook. If I were gone, he wrote, would

anybody notice? An alarmed student told staff members in the dorm, who called

Dr. Hwang after hours, who contacted the campus police. Officers escorted the

student to the county psychiatric hospital.

There were two more runs over that weekend, including one late Saturday night

when a student grew concerned that a friend with a prescription for Xanax, the

anti-anxiety drug, had swallowed a fistful.

On Sunday, a supervisor of residence halls, Gina Vanacore, sent a BlackBerry

update to Dr. Hwang, who has championed programs to train students and staff

members to intervene to prevent suicide.

“If you weren’t so good at getting this bystander stuff out there,” Ms. Vanacore

wrote in mock exasperation, “we could sleep on the weekends.”

Stony Brook is typical of American colleges and universities these days, where

national surveys show that nearly half of the students who visit counseling

centers are coping with serious mental illness, more than double the rate a

decade ago. More students take psychiatric medication, and there are more

emergencies requiring immediate action.

“It’s so different from how people might stereotype the concept of college

counseling, or back in the ’70s students coming in with existential crises: who

am I?” said Dr. Hwang, whose staff of 29 includes psychiatrists, clinical

psychologists and social workers. “Now they’re bringing in life stories

involving extensive trauma, a history of serious mental illness, eating

disorders, self-injury, alcohol and other drug use.”

Experts say the trend is partly linked to effective psychotropic drugs

(Wellbutrin for depression, Adderall for attention disorder, Abilify for bipolar

disorder) that have allowed students to attend college who otherwise might not

have functioned in a campus setting.

There is also greater awareness of traumas scarcely recognized a generation ago

and a willingness to seek help for those problems, including bulimia,

self-cutting and childhood sexual abuse.

The need to help this troubled population has forced campus mental health

centers — whose staffs, on average, have not grown in proportion to student

enrollment in 15 years — to take extraordinary measures to make do. Some have

hospital-style triage units to rank the acuity of students who cross their

thresholds. Others have waiting lists for treatment — sometimes weeks long — and

limit the number of therapy sessions.

Some centers have time only to “treat students for a crisis, bandaging them up

and sending them out,” said Denise Hayes, the president of the Association for

University and College Counseling Center Directors and the director of

counseling at the Claremont Colleges in California.

“It’s very stressful for the counselors,” she said. “It doesn’t feel like why

you got into college counseling.”

A recent survey by the American College Counseling Association found that a

majority of students seek help for normal post-adolescent trouble like romantic

heartbreak and identity crises. But 44 percent in counseling have severe

psychological disorders, up from 16 percent in 2000, and 24 percent are on

psychiatric medication, up from 17 percent a decade ago.

The most common disorders today: depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, alcohol

abuse, attention disorders, self-injury and eating disorders.

Stony Brook, an academically demanding branch of the State University of New

York (its admission rate is 40 percent), faces the mental health challenges

typical of a big public university. It has 9,500 resident students and 15,000

who commute from off-campus. The highly diverse student body includes many who

are the first in their families to attend college and carry intense pressure to

succeed, often in engineering or the sciences. A Black Women and Trauma therapy

group last semester included participants from Africa, suffering post-traumatic

stress disorder from violence in their youth.

Stony Brook has seen a sharp increase in demand for counseling — 1,311 students

began treatment during the past academic year, a rise of 21 percent from a year

earlier. At the same time, budget pressures from New York State have forced a 15

percent cut in mental health services over three years.

Dr. Hwang, a clinical psychologist who became director in July 2009, has dealt

with the squeeze by limiting counseling sessions to 10 per student and referring

some, especially those needing long-term treatment for eating disorders or

schizophrenia, to off-campus providers.

But she has resisted the pressure to offer only referrals. By managing

counselors’ workloads, the center can accept as many as 60 new clients a week in

peak demand between October and the winter break.

“By this point in the semester to not lose hope or get jaded about the work, it

can be a challenge,” Dr. Hwang said. “By the end of the day, I go home so

adrenalized that even though I’m exhausted it will take me hours to fall

asleep.”

For relief, she plays with her 2-year-old daughter, and she has taken up the

guitar again.

Shifting to Triage

Near the student union in the heart of campus, the Student Health Center

building dates from the days when a serious undergraduate health problem was

mononucleosis. But the hiring of Judy Esposito, a social worker with experience

counseling Sept. 11 widows, to start a triage unit three years ago was a sign of

the new reality in student mental health.

At 9 a.m. on the Tuesday after the campus’s very busy weekend, Ms. Esposito had

just passed the Purell dispenser by the entrance when she noticed two colleagues

hurrying toward her office. Before she had taken off her coat, they were

updating her about a junior who had come in the previous week after cutting

herself and expressing suicidal thoughts.

Ms. Esposito’s triage team fields 15 to 20 requests for help a day. After brief

interviews, most students are scheduled for a longer appointment with a

psychologist, which leads to individual treatment. The one in six who do not

become patients are referred to other university departments like academic

advising, or to off-campus therapists if long-term help is needed. There are no

charges for on-campus counseling.

This day the walk-ins included a young man complaining of feeling friendless and

depressed. Another student said he was struggling academically, feared that his

parents would find out and was drinking and feeling hopeless.

Professionals in a mental health center are mindful of their own well-being. For

this reason the staff had planned a potluck holiday lunch. While a turkey

roasted in the kitchen that serves as the break room, Ms. Esposito helped warm

up candied yams, stuffing and the store-bought quiche that was her own

contribution.

Just then Regina Frontino, the triage assistant who greets walk-ins at the front

desk, swept into the kitchen to say a student had been led in by a friend who

feared that she was suicidal.

Ms. Esposito rushed to the lobby. From a brief conversation, she knew that the

distraught student would have to go to the hospital. The counseling center does

not have the ability to admit suicidal or psychotic students overnight for

observation or to administer powerful drugs to calm them. It arranges for them

to be taken to the Stony Brook University Medical Center, on the far side of the

1,000-acre campus. The hospital has a 24-hour psychiatric emergency room that

serves all of Suffolk County.

“They’re not going to fix what’s going on,” Ms. Esposito said, “but in that

moment we can ensure she’s safe.” She called Tracy Thomas, an on-call counselor,

to calm the student, who was crying intermittently, while she phoned the

emergency room and informed Dr. Hwang, who called the campus police to transport

the young woman.

When Ms. Esposito heard the crackle of police radios in the hallway, she went to

tell the student for the first time that she would have to go to the hospital.

“This is not something students love to do,” Ms. Esposito recounted. The young

woman told her she did not want to go. Ms. Esposito replied that the staff was

worried for her safety, and she repeated the conversation she had had earlier

with the young woman:

Are you having thoughts about wanting to die?

Yes.

Are you afraid you are actually going to kill yourself?

Yes.

She invited a police officer into the counseling room, and the student teared up

again at the sight of him. Ms. Esposito assured her that she was not in trouble.

Meanwhile, an ambulance crew arrived with a rolling stretcher, but the young

woman walked out on her own with the officers.

Because Ms. Thomas, a predoctoral intern in psychology, now needed to regain her

own equilibrium before seeing other clients, Ms. Esposito debriefed her about

what had just happened.

Finally she returned to her office, having missed the holiday lunch, and found

that her team had prepared a plate for her.

“It’s kind of like firemen,” she said. “When the fire’s on, we are just at it.

But once the fire’s out, we can go back to the house and eat together and

laugh.”

Reaching Out

Even though the appointment books of Stony Brook counselors are filled, all

national evidence suggests that vastly more students need mental health

services.

Forty-six percent of college students said they felt “things were hopeless” at

least once in the previous 12 months, and nearly a third had been so depressed

that it was difficult to function, according to a 2009 survey by the American

College Health Association.

Then there is this: Of 133 student suicides reported in the American College

Counseling Association’s survey of 320 institutions last year, fewer than 20 had

sought help on campus.

Alexandria Imperato, 23, remembers that as a Stony Brook freshman all her high

school friends were talking about how great a time they were having in college,

while she felt miserable. She faced family issues and the pressure of adjusting

to college. “You go home to Thanksgiving dinner, and the family asks your

brother how is his gerbil, and they ask you, ‘What are doing with the rest of

your life?’ ” Ms. Imperato said.

She learned she had clinical depression. She eventually conquered it with

psychotherapy, Cymbalta and lithium. She went on to form a Stony Brook chapter

of Active Minds, a national campus-based suicide-prevention group.

“I knew how much better it made me feel to find others,” said Ms. Imperato, who

plans to be a nurse.

On recent day, she was one of two dozen volunteers in black T-shirts reading

“Chill” who stopped passers-by in the Student Activities Center during lunch

hour.

“Would you like to take a depression screening?” they asked, offering a

clipboard with a one-page form to all who unplugged their ear buds. Students

checked boxes if they had difficulty sleeping, felt hopeless or “had feelings of

worthlessness.” They were offered a chance to speak privately with a

psychologist in a nearby office. Sixteen said yes.

The depression screenings are part of a program to enlist students to monitor

the mental health of peers, which is run by the four-year-old Center for

Outreach and Prevention, a division of mental health services that Dr. Hwang

oversaw before her promotion to director of all counseling services.

She is committed to outreach in its many forms, including educating dormitory

staff members to recognize students in distress and encouraging professors to

report disruptive behavior in class.

In previous years, more than 1,000 depression screenings were given to students,

with 22 percent indicating signs of major depression. Dr. Hwang credits that and

other outreach efforts to the swell of new cases for counseling. “For a lot of

people it’s terrifying” to come to the counseling center, she said. “If there’s

anything we can do to make it easier to walk in, I feel like we owe it to them.”

Stony Brook has not had a student suicide since spring 2009, unusual for a

campus its size. But Dr. Hwang is haunted by the impact on the campus of several

off-campus student deaths in accidents and a homicide in the past year. “With

every vigil, with every conversation with someone in pain, there’s this

overwhelming sense of we need to learn something,” she said. “I think about

these parents who’ve invested so much into getting their kids alive to 18.”

One student who said yes to an impromptu interview with a counselor after

filling out a depression screening was a psychology major, a senior from upstate

New York. As it happened, Dr. Hwang had wandered over from the counseling center

to check on the screenings, and the young woman spent a long time conferring

with her, never removing her checked coat or backpack.

“I don’t have motivation for things anymore,” the student said afterward. “This

place just depresses me the whole time.”

She had been unaware that students could walk in unannounced to the counseling

center. “I thought you had to make an appointment,” she said. “Yes,” she said,

“I’ll do that.”

Serious Mental Health

Needs Seen Growing at Colleges, NYT, 19.12.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/20/health/20campus.html

Is Going to an Elite College Worth the Cost?

December 17, 2010

The New York Times

By JACQUES STEINBERG

AS hundreds of thousands of students rush to fill out college applications to

meet end-of-the-year deadlines, it might be worth asking them: Is where you

spend the next four years of your life that important?

The sluggish economy and rising costs of college have only intensified questions

about whether expensive, prestigious colleges make any difference. Do their

graduates make more money? Get into better professional programs? Make better

connections? And are they more satisfied with their lives, or at least with

their work?

Many college guidance counselors will say, find your own rainbow. But that can

sound like pablum to even the most laid-back parent and student.

Answers to such questions cannot be found, typically, in the sort of data

churned out annually in the U.S. News and World Report rankings, which tend to

focus on inputs like average SAT scores or college rejection rates. Handicappers

shy away from collating such information partly because it can be hard to

measure something like alumni satisfaction 5 to 10 years out. Moreover, in

taking a yardstick to someone’s success, or quality of life, how much can be

attributed to one’s alma mater, versus someone’s aptitude, intelligence and

doggedness?

But economists and sociologists have tried to tackle these questions. Their

research, however hedged, does suggest that elite schools can make a difference

in income and graduate school placement. But happiness in life? That’s a

question for another day.

Among the most cited research on the subject — a paper by economists from the

RAND Corporation and Brigham Young and Cornell Universities — found that “strong

evidence emerges of a significant economic return to attending an elite private

institution, and some evidence suggests this premium has increased over time.”

Grouping colleges by the same tiers of selectivity used in a popular college

guidebook, Barron’s, the researchers found that alumni of the most selective

colleges earned, on average, 40 percent more a year than those who graduated

from the least selective public universities, as calculated 10 years after they

graduated from high school.

Those same researchers found in a separate paper that “attendance at an elite

private college significantly increases the probability of attending graduate

school, and more specifically graduate school at a major research university.”

One major caveat: these studies, which tracked more than 5,000 college

graduates, some for more than a decade, are themselves now more than a decade

old. Over that period, of course, the full sticker price for elite private

colleges has far outstripped the pace of inflation, to say nothing of the cost

of many of their public school peers (even accounting for the soaring prices of

some public universities, especially in California, suffering under state budget

crises).

For example, full tuition and fees at Princeton this year is more than $50,000,

while Rutgers, the state university just up the New Jersey Turnpike, costs state

residents less than half that. The figures are similar for the University of

Pennsylvania and Pennsylvania State University. (For the sake of this exercise,

set aside those students at elite colleges whose financial aid packages cover

most, if not all, of their education.)

Despite the lingering gap in pricing between public and private schools, Eric R.

Eide, one of the authors of that paper on the earnings of blue-chip college

graduates, said he had seen no evidence that would persuade him to revise, in

2010, the conclusion he reached in 1998.

“Education is a long-run investment,” said Professor Eide, chairman of the

economics department at Brigham Young, “It may be more painful to finance right

now. People may be more hesitant to go into debt because of the recession. In my

opinion, they should be looking over the long run of their child’s life.”

He added, “I don’t think the costs of college are going up faster than the

returns on graduating from an elite private college.”

Still, one flaw in such research has always been that it can be hard to

disentangle the impact of the institution from the inherent abilities and

personal qualities of the individual graduate. In other words, if someone had

been accepted at an elite college, but chose to go to a more pedestrian one,

would his earnings over the long term be the same?

In 1999, economists from Princeton and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation looked at

some of the same data Professor Eide and his colleagues had used, but crunched

them in a different way: they compared students at more selective colleges to

others of “seemingly comparable ability,” based on their SAT scores and class

rank, who had attended less selective schools, either by choice or because a top

college rejected them.

The earnings of graduates in the two groups were about the same — perhaps

shifting the ledger in favor of the less expensive, less prestigious route. (The

one exception was that children from “disadvantaged family backgrounds” appeared

to earn more over time if they attended more selective colleges. The authors,

Stacy Berg Dale and Alan B. Krueger, do not speculate why, but conclude, “These

students appear to benefit most from attending a more elite college.”)

Earnings, of course, and even graduate school attendance, are but two of many

measurements of graduates’ success post-college.

Earlier this year, two labor and education professors from Penn State, along

with a sociologist from Claremont Graduate University in California, sought to

examine whether graduates from elite colleges were, in general, more satisfied

in their work than those who attended less prestigious institutions.

Writing in April in the Journal of Labor Research, the three researchers argued

that “an exclusive focus on the economic outcomes of college graduation, and

from prestigious colleges in particular, neglects a host of other employment

features.”

Mining a sample of nearly 5,000 recipients of bachelor’s degrees in 1992 and

1993, who were then tracked for nearly a decade, the authors concluded that “job

satisfaction decreases slightly as college selectivity moves up.” One hypothesis

by the authors was that the expectations of elite college graduates — especially

when it came to earnings — might have been higher, and thus more subject to

disappointment, than the expectations of those who graduated from less

competitive colleges.

Still, one of those authors, Scott L. Thomas, a sociologist who is a professor

of educational studies at Claremont, said high school students and their parents

should take any attempt to apply broad generalizations to such personal choices

with a grain of salt.

“Prestige does pay,” Mr. Thomas said in an interview. “But prestige costs, too.

The question is, is the cost less than the added return?”

His answer was one he said he knew families would find maddening: “It depends.”

For example, someone who knew he needed to earn a reliable salary immediately

after graduation, and as a result chose to study something practical like

business or engineering, might find the cost-benefit analysis tilted in favor of

a state school, he said.

“Students from less affluent backgrounds are going to find themselves in

situations where college is less about ‘finding themselves,’ and more about

skills acquisition and making contacts that will lead straight into the labor

market,” Mr. Thomas said. For such a student, he said, a state university,

particularly a big one, may also have a large, passionate alumni body. It, in

turn, may play a disproportionate role in deciding who gets which jobs in a

state in a variety of fields — an old-boy (and increasingly old-girl) network

that may be less impressed with a job applicant’s Ivy league pedigree.

“If you’ve attended a big state school with a tremendous football program,” Mr.

Thomas said, “there’s tremendous affinity and good will — whether or not you had

anything to do with the football program.”

In the end, some researchers echo that tried-and-perhaps-even-true wisdom of

guidance counselors: the extent to which one takes advantage of the educational

offerings of an institution may be more important, in the long run, than how

prominently and proudly that institution’s name is being displayed on the back

windows of cars in the nation’s wealthiest enclaves.

In this analysis, one’s major — and how it aligns with the departmental

strengths of a university — may be more significant than the place in the

academic pecking order awarded to that college by the statisticians at U.S.

News.

“Everything we know from studying college student experiences and outcomes tells

us that there is more variability within schools than between them,” said

Alexander C. McCormick, a former admissions officer at his alma mater, Dartmouth

College, and now an associate professor of education at Indiana University at

Bloomington.

“This is the irony, given the dominance of the rankings mentality of who’s No. 5

or No. 50,” Professor McCormick added. “The quality of that biology major

offered at School No. 50? It may exceed that at School No. 5.”

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: December 17, 2010

An earlier version of this article referred incorrectly to the RAND organization

as a foundation.

Is Going to an Elite

College Worth the Cost?, NYT, 17.12.22010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/19/weekinreview/19steinberg.html

College, Jobs and Inequality

December 13, 2010

The New York Times

Searching for solace in bleak unemployment numbers, policy makers and

commentators often cite the relatively low joblessness among college graduates,

which is currently 5.1 percent compared with 10 percent for high school

graduates and an overall jobless rate of 9.8 percent. Ben Bernanke, the chairman

of the Federal Reserve, cited the data recently on “60 Minutes” to make the

point that “educational differences” are a root cause of income inequality.

A college education is better than no college education and correlates with

higher pay. But as a cure for unemployment or as a way to narrow the chasm

between the rich and everyone else, “more college” is a too-easy answer. Over

the past year, for example, the unemployment rate for college grads under age 25

has averaged 9.2 percent, up from 8.8 percent a year earlier and 5.8 percent in

the first year of the recession that began in December 2007. That means recent

grads have about the same level of unemployment as the general population. It

also suggests that many employed recent grads may be doing work that doesn’t

require a college degree.

Even more disturbing, there is no guarantee that unemployed or underemployed

college grads will move into much better jobs as conditions improve. Early bouts

of joblessness, or starting in a lower-level job with lower pay, can mean lower

levels of career attainment and earnings over a lifetime.Graduates who have been

out of work or underemployed in the downturn may also find themselves at a

competitive disadvantage with freshly minted college graduates as the economy

improves.

When it comes to income inequality, college-educated workers make more than

noncollege-educated ones. But higher pay for college grads cannot explain the

profound inequality in the United States. The latest installment of the

groundbreaking work on income inequality by the economists Thomas Piketty and

Emmanuel Saez shows that the richest 1 percent of American households — those

making more than $370,000 a year — received 21 percent of total income in 2008.

That was slightly below the highs of the bubble years but still among the

highest percentages since the Roaring Twenties.

The top 10 percent — those making more than $110,000 — received 48 percent of

total income, leaving 52 percent for the bottom 90 percent. Where are

college-educated workers? Their median pay has basically stagnated for the past

10 years, at roughly $72,000 a year for men and $52,000 a year for women.

A big reason for the huge gains at the top is the outsize pay of executives,

bankers and traders. Lower on the income ladder, workers have not fared well, in

part because health care has consumed an ever-larger share of compensation and

bargaining power has diminished with the decline in labor unions.

College is still the path to higher-paying professions. But without a concerted

effort to develop new industries, the weakened economy will be hard pressed to

create enough better-paid positions to absorb all graduates.

And to combat inequality, the drive for more college and more jobs must coincide

with efforts to preserve and improve the policies, programs and institutions

that have fostered shared prosperity and broad opportunity — Social Security,

Medicare, public schools, progressive taxation, unions, affirmative action,

regulation of financial markets and enforcement of labor laws.

College is not a cure-all, but it will certainly take the best and brightest

minds to confront those challenges.

College, Jobs and

Inequality, NYT, 13.15.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/14/opinion/14tue1.html

Promoting Learning, or Dependence?

November 21, 2010

The New York Times

To the Editor:

Re “More

Professors Give Out Hand-Held Devices to Monitor Students and Engage Them”

(“The Choice,” news article, Nov. 16):

I read your article with dismay. The devices mentioned in the article that

require students to give feedback to the professor every 15 minutes (to make

sure that the students are not sleeping or doing social networking) follow a

trend that encourages students to become increasingly dependent. These students

are not being taught the value of self-motivation and responsibility; they are

being prompted to respond.

As one student said: “I actually kind of like it. It does make you read. It

makes you pay attention. It reinforces what you are supposed to be doing as a

student.” Isn’t it sad that this student needs a clicker to make sure that she

does what she is supposed to be doing as a student? When she graduates, I

suppose that her future employers will need to distribute clickers to make sure

that she does what she is supposed to be doing as an employee.

In my courses I expect that students are young adults committed to learning and

that they will accept responsibility for their success or their failure. I

consider this approach part of my duty to help prepare them for life as

independent, self-motivated members of society.

Gustavo Pellón

Charlottesville, Va., Nov. 16, 2010

The writer is an associate professor of Spanish and comparative literature at

the University of Virginia.

•

To the Editor:

The effectiveness of clickers to promote learning is based on the principle of

active response immediately followed by knowledge of results. It is an upgraded

variation of what teachers in K-12 have used since schools began.

The only caveat is that the clickers provide students with practice that is

appropriate for the goals teachers want to achieve. It’s easy to equate swift

and correct responses with deeper understanding. That’s why it’s risky to assume

that teachers can be judged strictly on the basis of observations.

Walt Gardner

Los Angeles, Nov. 16, 2010

The writer’s Reality Check blog is published in Education Week.

•

To the Editor:

Use of handheld devices to pose questions during class is not strictly an

undergraduate trend. Many lecturers at the Columbia College of Physicians and

Surgeons (and I assume other grad schools as well) enlist the devices not only

to stimulate critical thinking but also to encourage collaboration with

classmates.

Thus if used correctly, this technology may be interactive in the true sense of

the word. It plants the seeds for the interdisciplinary approach to

problem-solving that epitomizes modern medicine and other professional fields

today.

Geoff Rubin

New York, Nov. 16, 2010

The writer is a third-year medical student at Columbia.

•

To the Editor:

Your article about hand-held “clickers” being used in college classrooms across

the country to take attendance, increase student participation, monitor student

understanding, facilitate brief quizzes and generally enhance learning appeared

after a Nov. 5 front-page article described classes on the Web at the University

of Florida and a number of other large universities as these institutions

struggle to respond simultaneously to shrinking budgets and growing enrollments

(“Still in Dorm, Because Class Is on the Web”).

There may be a painful inconsistency between “serving” as many students as

possible and teaching them effectively. It is not hard to imagine that the

clicker-equipped students will be learning more, maybe much more, than their

peers who watch a computer monitor still clad in their pajamas. In the future,

what will “college graduate” mean?

James W. Davis

Clayton, Mo., Nov. 16, 2010

The writer is professor emeritus of political science at Washington University

in St. Louis.

Promoting Learning, or

Dependence?, NYT, 21.11.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/22/opinion/l22clicker.html

More Professors Give Out Hand-Held Devices to Monitor Students and Engage Them

November 15, 2010

The New York Times

By JACQUES STEINBERG

EVANSTON, Ill. — If any of the 70 undergraduates in Prof. Bill White’s

“Organizational Behavior” course here at Northwestern University are late for

class, or not paying attention, he will know without having to scan the lecture

hall.

Their “clickers” will tell him.

Every student in Mr. White’s class has been assigned a palm-size, wireless

device that looks like a TV remote but has a far less entertaining purpose. With

their clickers in hand, the students in Mr. White’s class automatically clock in

as “present” as they walk into class.

They then use the numbered buttons on the devices to answer multiple-choice

quizzes that count for nearly 20 percent of their grade, and that always begin

precisely one minute into class. Later, with a click, they can signal to their

teacher without raising a hand that they are confused by the day’s lesson.

But the greatest impact of such devices — which more than a half-million

students are using this fall on several thousand college campuses — may be

cultural: they have altered, perhaps irrevocably, the nap schedules of anyone

who might have hoped to catch a few winks in the back row, and made it harder

for them to respond to text messages, e-mail and other distractions.

In Professor White’s 90-minute class, as in similar classes at Harvard, the

University of Arizona and Vanderbilt, barely 15 minutes pass without his asking

students to “grab your clickers” to provide feedback

Though some Northwestern students say they resent the potential Big Brother

aspect of all this, Jasmine Morris, a senior majoring in industrial engineering,

is not one of them.

“I actually kind of like it,” Ms. Morris said after a class last week. “It does

make you read. It makes you pay attention. It reinforces what you’re supposed to

be doing as a student.”

Inevitably, some students have been tempted to see clickers as “cat and mouse”

game pieces. Noshir Contractor, who teaches a class on social networking to

Northwestern undergraduates, said he began using clickers in spring 2008 — and,

not long after, watched a student array perhaps five of the devices in front of

him.

The owners had skipped class, but their clickers had made it.

Professor Contractor said he tipped his cap to the students’ creativity — this

was, after all, a class on social networking — but then reminded them that there

“are other ways to count attendance,” and that, by the way, they were all

signatories to the school’s honor principle. The practice stopped, he said.

Though the technology is relatively new, preliminary studies at Harvard and Ohio

State, among other institutions, suggest that engaging students in class through

a device as familiar to them as a cellphone — there are even applications that

convert iPads and BlackBerrys into class-ready clickers — increases their

understanding of material that may otherwise be conveyed in traditional

lectures.

The clickers are also gaining wide use in middle and high schools, as well as at

corporate gatherings. Whatever the setting, audience responses are received on a

computer at the front of the room and instantly translated into colorful bar

graphs displayed on a giant monitor.

The remotes used at Northwestern were made by Turning Technologies, a company in

Youngstown, Ohio, and are compatible with PowerPoint. Depending on the model,

the hand-helds can sell for $30 to $70 each. Some colleges require students to

buy them; others lend them to students.

Tina Rooks, the chief instructional officer for Turning Technologies, said the

company expected to ship over one million clickers this year, with roughly half

destined for about 2,500 university campuses, including community colleges and

for-profit institutions. The company said its higher-education sales had grown

60 percent since 2008, and 95 percent since 2006.

At Northwestern, more than three dozen professors now use clickers in their

classrooms. Professor White, who teaches industrial engineering, was among the

first here to adopt them about six years ago.

He smiled knowingly when asked about some students’ professed dislike of the

clickers.

“They should walk in with them in their hands, on time, ready to go,” he said.

Professor White acknowledged, though, that the clickers were hardly a silver

bullet for engaging students, and that they were just one of many tools he

employed, including video clips, guest speakers and calling on individual

students to share their thoughts.

“Everyone learns differently,” he said. “Some learn watching stuff. Some learn

by listening. Some learn by reading. I try to mix it all into every class.”

Many of Professor White’s students said the highlight of his class was often the

display of results of a survey-via-clicker, when they could see whether their

classmates shared their opinions. They also said that they appreciated the

anonymity, and that while the professor might know how they responded, their

peers would not.

Last week, for example, he flashed a photo of the university president, Morton

Schapiro, onto the screen, along with a question, “Source of power?” followed by

these possible answers:

¶“1. Coercive power” (sometimes punitive).

¶“2. Reward power.”

¶“3. Legitimate power” (typically by virtue of one’s office).

¶“4. Expert power” (more typically applied to someone like an electrician or a

mechanic).

¶ 5. Referent power” (usually tied to how the leader is viewed personally).

To Professor White’s seeming relief, a clear majority, 71 percent, chose No. 3,

a sign that they considered his ultimate boss to be “legitimate.”

And then, to his delight, the students emerged from their electronic veils to

register their opinions the old-fashioned way.

“They can be very reluctant to speak when they think they’re in the minority,”

he said. “Once they see they’re not the only ones, they speak up more.”

More Professors Give Out

Hand-Held Devices to Monitor Students and Engage Them, NYT, 15.11.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/16/education/16clickers.html

In School Efforts to End Bullying, Some See Agenda

November 6, 2010

The New York Times

By ERIK ECKHOLM

HELENA, Mont. — Alarmed by evidence that gay and lesbian students are common

victims of schoolyard bullies, many school districts are bolstering their

antiharassment rules with early lessons in tolerance, explaining that some

children have “two moms” or will grow up to love members of the same sex.

But such efforts to teach acceptance of homosexuality, which have gained urgency

after several well-publicized suicides by gay teenagers, are provoking new

culture wars in some communities.

Many educators and rights advocates say that official prohibitions of slurs and

taunts are most effective when combined with frank discussions, from

kindergarten on, about diverse families and sexuality.

Angry parents and religious critics, while agreeing that schoolyard harassment

should be stopped, charge that liberals and gay rights groups are using the

antibullying banner to pursue a hidden “homosexual agenda,” implicitly

endorsing, for example, same-sex marriage.

Last summer, school officials here in Montana’s capital unveiled new guidelines

for teaching about sexuality and tolerance. They proposed teaching first graders

that “human beings can love people of the same gender,” and fifth graders that

sexual intercourse can involve “vaginal, oral or anal penetration.”

A local pastor, Rick DeMato, carried his shock straight to the pulpit.

“We do not want the minds of our children to be polluted with the things of a

carnal-minded society,” Mr. DeMato, 69, told his flock at Liberty Baptist

Church.

In tense community hearings, some parents made familiar arguments that innocent

youngsters were not ready for explicit language. Other parents and pastors,

along with leaders of the Big Sky Tea Party, saw a darker purpose.

“Anyone who reads this document can see that it promotes acceptance of the

homosexual lifestyle,” one mother said at a six-hour school board meeting in

late September.

Barely heard was the plea of Harlan Reidmohr, 18, who graduated last spring and

said he was relentlessly tormented and slammed against lockers after coming out

during his freshman year. Through his years in the Helena schools, he said at

another school board meeting, sexual orientation was never once discussed in the

classroom, and “I believe this led to a lot of the sexual harassment I faced.”

Last month, the federal Department of Education told schools they were

obligated, under civil rights laws, to try to prevent harassment, including that

based on sexual orientation and gender identity. But the agency did not address

the controversy over more explicit classroom materials in grade schools.

Some districts, especially in larger cities, have adopted tolerance lessons with

minimal dissent. But in suburban districts in California, Illinois and

Minnesota, as well as here in Helena, the programs have unleashed fierce

opposition.

“Of course we’re all against bullying,” Mr. DeMato, one of numerous pastors who

opposed the plan, said in an interview. “But the Bible says very clearly that

homosexuality is wrong, and Christians don’t want the schools to teach subjects

that are repulsive to their values.”

The divided Helena school board, after four months of turmoil, recently adopted

a revised plan for teaching about health, sex and diversity. Much of the

explicit language about sexuality and gay families was removed or replaced with

vague phrases, like a call for young children to “understand that family

structures differ.” The superintendent who has ardently pushed the new

curriculum, Bruce K. Messinger, agreed to let parents remove their children from

lessons they find objectionable.

In Alameda, Calif., officials started to introduce new tolerance lessons after

teachers noticed grade-schoolers using gay slurs and teasing children with gay

or lesbian parents. A group of parents went to court seeking the right to remove

their children from lessons that included reading “And Tango Makes Three,” a

book in which two male penguins bond and raise a child.

The parents lost the suit, and the school superintendent, Kirsten Vital, said

the district was not giving ground. “Everyone in our community needs to feel

safe and visible and included,” Ms. Vital said.

Some of the Alameda parents have taken their children out of public schools,

while others now hope to unseat members of the school board.

After at least two suicides by gay students last year, a Minnesota school

district recently clarified its antibullying rules to explicitly protect gay and

lesbian students along with other target groups. But to placate religious

conservatives, the district, Anoka-Hennepin County, also stated that teachers

must be absolutely neutral on questions of sexual orientation and refrain from

endorsing gay parenting.

Rights advocates worry that teachers will avoid any discussion of gay-related

topics, missing a chance to fight prejudice.

While nearly all states require schools to have rules against harassment, only

10 require them to explicitly outlaw bullying related to sexual orientation.

Rights groups including the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network, based

in New York, are promoting a federal “safe schools” act to make this a universal

requirement, although passage is not likely any time soon.

Candi Cushman, an educational analyst with Focus on the Family, a Christian

group, said that early lessons about sexuality and gay parents reflected a

political agenda, including legitimizing same-sex marriage. “We need to protect

all children from bullying,” Ms. Cushman said. “But the advocacy groups are

promoting homosexual lessons in the name of antibullying.”

Ellen Kahn of the Human Rights Campaign in Washington, which offers a “welcoming

schools” curriculum for grade schools, denied such motives.

“When you talk about two moms or two dads, the idea is to validate the families,

not to push a debate about gay marriage,” Ms. Kahn said. The program involves

what she described as age-appropriate materials on family and sexual diversity

and is used in dozens of districts, though it has sometime stirred dissent.

The Illinois Safe Schools Alliance, which runs teacher-training programs and

recommends videos and books depicting gay parents in a positive light, has met

opposition in several districts, including the Chicago suburb of Oak Park.

Julie Justicz, a 47-year-old lawyer, and her partner live in Oak Park with two

sons ages 6 and 11. Ms. Justicz saw the need for early tolerance training, she

said, when their older son was upset by pejorative terms about gays in the

schoolyard.

Frank classroom discussions about diverse families and hurtful phrases had

greatly reduced the problem, she said.

But one of the objecting parents, Tammi Shulz, who describes herself as a

traditional Christian, said, “I just don’t think it’s great to talk about

homosexuality with 5-year-olds.”

Tess Dufrechou, president of Helena High School’s Gay-Straight Alliance, a club

that promotes tolerance, counters that, “By the time kids get to high school,

it’s too late.”

Only a handful of students in Helena high schools are openly gay, with others

keeping the secret because they fear the reactions of parents and peers,

students said.

Michael Gengler, one of the few to have come out, said, “You learn from an early

age that it’s not acceptable to be gay,” adding that he was disappointed that

the teaching guidelines had been watered down.

But Mr. Messinger, the superintendent, said he still hoped to achieve the

original goals without using the explicit language that offended many parents.

“This is not about advocating a lifestyle, but making sure our children

understand it and, I hope, accept it,” he said.

In School Efforts to End

Bullying, Some See Agenda, NYT, 6.11.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/07/us/07bully.html

Learning in Dorm, Because Class Is on the Web

November 4, 2010

The New York Times

By TRIP GABRIEL

GAINESVILLE, Fla. — Like most other undergraduates, Anish Patel likes to

sleep in. Even though his Principles of Microeconomics class at 9:35 a.m. is

just a five-minute stroll from his dorm, he would rather flip open his laptop in

his room to watch the lecture, streamed live over the campus network.

On a recent morning, as Mr. Patel’s two roommates slept with covers pulled

tightly over their heads, he sat at his desk taking notes on Prof. Mark Rush’s

explanation of the term “perfect competition.” A camera zoomed in for a close-up

of the blackboard, where Dr. Rush scribbled in chalk, “lots of firms and lots of

buyers.”

The curtains were drawn in the dorm room. The floor was awash in the flotsam of

three freshmen — clothes, backpacks, homework, packages of Chips Ahoy and Cap’n

Crunch’s Crunch Berries.

The University of Florida broadcasts and archives Dr. Rush’s lectures less for

the convenience of sleepy students like Mr. Patel than for a simple principle of

economics: 1,500 undergraduates are enrolled and no lecture hall could possibly

hold them.

Dozens of popular courses in psychology, statistics, biology and other fields

are also offered primarily online. Students on this scenic campus of stately

oaks rarely meet classmates in these courses.

Online education is best known for serving older, nontraditional students who

can not travel to colleges because of jobs and family. But the same technologies

of “distance learning” are now finding their way onto brick-and-mortar campuses,

especially public institutions hit hard by declining state funds. At the

University of Florida, for example, resident students are earning 12 percent of

their credit hours online this semester, a figure expected to grow to 25 percent

in five years.

This may delight undergraduates who do not have to change out of pajamas to

“attend” class. But it also raises questions that go to the core of a college’s

mission: Is it possible to learn as much when your professor is a mass of pixels

whom you never meet? How much of a student’s education and growth — academic and

personal — depends on face-to-face contact with instructors and fellow students?

“When I look back, I think it took away from my freshman year,” said Kaitlyn

Hartsock, a senior psychology major at Florida who was assigned to two online

classes during her first semester in Gainesville. “My mom was really upset about

it. She felt like she’s paying for me to go to college and not sit at home and

watch through a computer.”

Across the country, online education is exploding: 4.6 million students took a

college-level online course during fall 2008, up 17 percent from a year earlier,

according to the Sloan Survey of Online Learning. A large majority — about three

million — were simultaneously enrolled in face-to-face courses, belying the

popular notion that most online students live far from campuses, said Jeff

Seaman, co-director of the survey. Many are in community colleges, he said. Very

few attend private colleges; families paying $53,000 a year demand low

student-faculty ratios.

Colleges and universities that have plunged into the online field, mostly

public, cite their dual missions to serve as many students as possible while

remaining affordable, as well as a desire to exploit the latest technologies.

At the University of Iowa, as many as 10 percent of 14,000 liberal arts

undergraduates take an online course each semester, including Classical

Mythology and Introduction to American Politics.

At the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, first-year Spanish students

are no longer offered a face-to-face class; the university moved all instruction

online, despite internal research showing that online students do slightly less

well in grammar and speaking.

“You have X amount of money, what are you going to do with it?” said Larry King,

chairman of the Romance languages department, where budget cuts have forced

difficult choices. “You can’t be all things to all people.”

The University of Florida has faced sweeping budget cuts from the State

Legislature totaling 25 percent over three years. That is a main reason the

university is moving aggressively to offer more online instruction. “We see this

as the future of higher education,” said Joe Glover, the university provost.

“Quite honestly, the higher education industry in the United States has not been

tremendously effective in the face-to-face mode if you look at national

graduation rates,” he added. “At the very least we should be experimenting with

other modes of delivery of education.”

A sampling of Florida professors teaching online found both enthusiasm and

doubts. “I would prefer to teach classes of 50 and know every student’s name,

but that’s not where we are financially and space-wise,” said Megan Mocko, who

teaches statistics to 1,650 students. She said an advantage of the Internet is

that students can stop the lecture and rewind when they do not understand

something.

Ilan Shrira, who teaches developmental psychology to 300, said that he chose his

field because of the passion of a professor who taught him as an undergraduate.

But he thought it unlikely that anyone could be so inspired by an online course.

Kristin Joos built interactivity into her Principles of Sociology course to keep

students engaged. There are small-group online discussions, and students join a

virtual classroom once a week using a conferencing software called WiZiQ.

“Hi, everyone, welcome to Week 9. Hello!” Dr. Joos said in a peppy voice

recently to about 60 students who had logged on. She sat at a desk in her home

office; a live video feed she switched on at one point showed her in black

librarian’s glasses and a tank top.

Ms. Hartsock, the senior psychology major, followed the class from her own

off-campus home, her laptop open on the dining room table. As Dr. Joos lectured,

a chat box scrolled with students’ comments and questions.

The topic was sexual identity, which Dr. Joos defined as “a determination made

through the application of socially agreed-upon biological criteria for

classifying persons as females and males.”

She asked students for their own definitions. One, bringing an online-chat

sensibility to an academic discussion, typed: “If someone looks like a chick and

wants to be called a chick even though they’re not, now they can be one.”

Ms. Hartsock, 23, diligently typed notes. A hard-working student who maintains

an A average, she was frustrated by the online format. Other members of her

discussion group were not pulling their weight, she said. The one test so far,

online, required answering five questions in 10 minutes — a lightning round

meant to prevent cheating by Googling answers.

In a conventional class, “I’m someone who sits toward the front and shares my

thoughts with the teacher,” she said. In the 10 or so online courses she has

taken in her four years, “it’s all the same,” she said. “No comments. No

feedback. And the grades are always late.”

As her attention wandered, she got up to microwave some leftover rice.

Learning in Dorm,

Because Class Is on the Web, NYT, 4.11.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/05/us/05college.html

48th Is Not a Good Place

October 26, 2010

The New York Times

The National Academies, the country’s leading advisory group on science and

technology, warned in 2005 that unless the United States improved the quality of

math and science education, at all levels, it would continue to lose economic

ground to foreign competitors.

The situation remains grim. According to a follow-up report published last

month, the academies found that the United States ranks 27th out of 29 wealthy

countries in the proportion of college students with degrees in science or

engineering, while the World Economic Forum ranked this country 48th out of 133

developed and developing nations in quality of math and science instruction.

More than half the patents awarded here last year were given to companies from

outside the United States. In American graduate schools, nearly half of students

studying the sciences are foreigners; while these students might once have spent

their careers here, many are now opting to return home.

In a 2009 survey, nearly a third of this country’s manufacturing companies

reported having trouble finding enough skilled workers.

The academies call on federal and state governments to improve early childhood

education, strengthen the public school math and science curriculum, and improve

teacher training in these crucial subjects. It calls on government and colleges

to provide more financial and campus support to students who excel at science.

The report sets a goal of increasing the percentage of people with undergraduate

degrees in science from 6 percent to 10 percent. It calls for the country to

quickly double the number of minority students who hold science degrees — to

160,000 from about 80,000.

Too often, science curriculums are grinding and unimaginative, which may help

explain why more than half of all college science majors quit the discipline

before they earn their degrees. The science establishment has long viewed a high

abandonment rate as part of a natural winnowing.

The University of Maryland, Baltimore County — one of the leading producers of

African-American research scientists in the country — rejects that view. It has

shown that science and engineering students thrive when they are given mentors

and early exposure to exciting, cutting-edge laboratory science. Other colleges

are now trying to emulate the program.

Congress has an important role to play. It can start by embracing the academies’

call to attract as many as 10,000 qualified math and science teachers annually

to the profession. One sound way to do that — while also increasing the number

of minority scientists — is to expand funding for programs that support

high-caliber math and science students in college in return for their commitment

to teach in needy districts.

48th Is Not a Good

Place, NYT? 26.10.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/26/opinion/26tue2.html

Our Choice: How to Save the Schools

October 16, 2010

The New York Times

To the Editor:

Re “Grading School Choice,” by Ross

Douthat (column, Oct. 11), about “Waiting for ‘Superman,’ ” a new documentary

film:

This is not a movie about public education, as Mr. Douthat and other

commentators seem to believe. It is a movie about families and children who care

about education.

This, in turn, raises the questions that have derailed every school reform plan

yet devised: How, exactly, does “school choice” help the girl whose single

mother is too caught up in alcohol and drugs to sign up for a lottery? How does

giving a voucher to the father who sexually abuses his young son make a

difference in that child’s life?

A Times article last spring said that, according to a 2008 report from the

Center for New York City Affairs at the New School, about 140,000 teenagers

“were missing a month or more of classes each year by the time they reached high

school.”

If your mother’s or father’s idea of “school choice” is to let you stay home

whenever you choose, then grading teachers is not going to be a cure.

John J. Viall

Cincinnati, Oct. 11, 2010

The writer is a retired public school teacher.

•

To the Editor:

Choice does not make better schools; parental involvement does.

Public schools all over San Francisco have been turning around because parents

cannot afford the $20,000 tuition for private schools and instead are becoming

involved in their local public schools.

But even in these success stories, subjects like art, music and physical

education are often taught by the regular classroom teacher or “independent

contractors” who make weekly visits. Middle-class parents supplement with

after-school enrichment, like music lessons, sports teams, art classes and

tutoring.

But many of the lowest-performing schools cannot rely on parental involvement.

These schools need to provide after-school homework help, art, music, sports and

in some cases health services like dental and medical visits. The students need

to learn the discipline of doing homework, but also the joy of education through

art, music and sports.

We have all heard for many years now, “Read to your children.” But for many

children, this simple act never occurs.

Catherine Palmer

San Francisco, Oct. 11, 2010

•

To the Editor:

I wait patiently for someone to explain this: Why is Ross Douthat (and most of

the right wing in this country) so sure that “monopoly breeds mediocrity” and

competition is the answer to improving public schools?

The best educational systems in the world, such as those in Finland, Japan and

South Korea, are pure public “monopolies.”

Max Page

Amherst, Mass., Oct. 11, 2010

The writer is a professor of architecture and history at the University of

Massachusetts and a member of the executive committee of the Massachusetts

Teachers Association.

•

To the Editor:

Ross Douthat argues that increasing competition in education through a

free-market ideology will improve schools. But any teacher who sees money as an

incentive to improving the quality of instruction should not be teaching.

Merit pay, charter schools and vouchers are all based on the same mistaken

assumption that a free-market ideology will raise academic standards. The

motivation behind good teaching is intrinsic. It is a profession that does not

readily lend itself to market forces.

The real problem with the academic reform dialogue is that too few teachers are

included.

Larry Hoffner

New York, Oct. 11, 2010

The writer is a high school teacher.

•

To the Editor:

Ross Douthat says that there are high-achieving charter schools like those in

KIPP and the Harlem Children’s Zone, but that many other charter schools are not

high-achieving. Yet the same is true of public, private and parochial schools.

The question of how to shape school structure is a political and sadly circular

debate that allows children to get lost.

Every ineffective school is a problem, and within every successful school we can

seek solutions that can be replicated. The issue should not be about “grading

school choice,” but about making certain that we maximize the opportunities for

each child.

Shelly Beaser

Bala Cynwyd, Pa., Oct. 11, 2010

The writer is a teacher and is on the board of KIPP Philadelphia.

Our Choice: How to Save

the Schools, NYT, 16.10.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/17/opinion/l17douthat.html

Grading School Choice

October 10, 2010

The New York Times

By ROSS DOUTHAT

In this fall’s must-see documentary, “Waiting for ‘Superman,’ ” Davis

Guggenheim offers a critique of America’s public school bureaucracy that’s

manipulative, simplistic and more than a little bit utopian.

Not that there’s anything wrong with that. Guggenheim’s cause, the plight of

children trapped in failing schools with lousy, union-protected teachers, is

important enough to make his overzealousness forgivable. And his prescription —

more accountability for teachers and bureaucrats, and more choices for parents

and kids — deserves all the support his film promises to win for it.

But if propaganda has its virtues, it also has its limits. Guggenheim’s movie,

which follows five families through the brutal charter school lotteries that

determine whether their kids will escape from public “dropout factories,” stirs

an entirely justified outrage at the system’s unfairnesses and cruelties. This

outrage needs to be supplemented, though, with a dose of realism about what

education reformers can reasonably hope to accomplish, and what real choice and

competition would ultimately involve.

With that in mind, I have a modest proposal: Copies of Frederick Hess’s recent

National Affairs essay, “Does School Choice ‘Work’?” should be handed out at

every “Waiting for ‘Superman’ ” showing, as a sober-minded complement to

Guggenheim’s cinematic call to arms.

An education scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, Hess supports just

about every imaginable path to increasing competition in education: charter

schools, merit pay for teachers, vouchers, even for-profit academies.

But he also recognizes that partisans of school choice tend to wildly

overpromise — implying that their favored policies could swiftly Lake Wobegonize

America, and make every school and student above average. (This is a trap, alas,

that “Waiting for ‘Superman’” falls into as well.)

Overpromising leads inevitably to disappointment. When it comes to raising test

scores, the grail of most reformers, school choice’s record is still ambiguous.

For every charter school success story like the Harlem Children’s Zone and the

KIPP network — both touted in Guggenheim’s documentary — there’s a charter

school where scores are worse than the public school status quo. The same is

true for vouchers and merit pay: the jury is still out on whether either policy

consistently raises academic performance.

This doesn’t mean that school choice doesn’t work, Hess argues. It just means

that the benefits are often more modest and incremental than many reformers want

to think. They can be measured in money saved (both charter and private schools

usually spend much less per pupil than their public competitors), in improved

graduation rates, and in higher parental and student satisfaction. But they

don’t always show up in test scores.

This insight leads to Hess’s second argument — that if reformers want to see

more than modest academic improvements, they need to set more ambitious goals.

The theory of school choice is the theory of the free market: monopoly breeds

mediocrity, and more competition should make all the competitors improve. But in

practice, even the more ambitious school choice experiments have protected the

public school system from the rigors of real competition.

When poor-performing public schools lose students to charters or private-school

competitors, Hess points out, there are rarely any consequences. In Milwaukee,

for instance, where a high-profile voucher program has been in place since 1990,

public school enrollment has dropped as families have taken vouchers and fled

the public system. But spending on public schools has gone steadily upward,

effectively rewarding bureaucrats for their failure to keep parents and students

happy. As Hess writes, “This is choice without consequences — competition as

soft political slogan rather than hard economic reality.”

A real marketplace in education, he suggests, probably wouldn’t fund schools

directly at all. It would only fund students, tying a school’s budget to the

number of children seeking to enroll. If there are 150 applicants for a charter

school, they should all bring their funding with them — and take it away from

the failing schools they’re trying to escape.

This is a radical idea, guaranteed to meet intense resistance from just about

every educational interest group. But Hess makes a compelling case that it needs

to be the school choice movement’s long-term goal, if reformers hope to do more

than just tinker around the edges of the system.

In the shorter term, meanwhile, he suggests that school choice advocates need to

make a case for greater competition that doesn’t depend on test scores alone.

Maybe charter schools, merit pay and vouchers won’t instantly turn every

American child into a test-acing dynamo. But if they “only” create a more

cost-effective system that makes parents and students happier with their schools

— well, that would be no small feat, and well worth fighting for.

Grading School Choice,

NYT, 10.10.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/11/opinion/11douthat.html

The Face of Private-School Growth, Familiar-Looking but

Profit-Making

September 21, 2010

The New York Times

By JENNY ANDERSON

The British International School of New York offers spacious waterfront

classrooms, small computers encased in rubber for small people who tend to drop

them, and a pool for the once-a-week swimming classes required for all students.

But there is nothing within its halls or on its Web site that indicates what

differentiates British International from the teeming masses of expensive

private schools in New York: It is run for profit.

It is one of a small number of large for-profit schools that have opened

recently or plan to open in New York City next year. While they are a speck on

the city’s private-school landscape, for-profit schools are practically the only

significant primary and secondary institutions to have started up in the last

decade, and may represent the future of private-school growth.

Parents and consultants have begun to take notice, and the Independent School

Admission Association of Greater New York, the umbrella group for the city’s

elite private schools, is contemplating withdrawing its requirement that members

be nonprofit, two association members said.

James Williams, executive director of the National Independent Private School

Association, whose members are for-profit schools, said that although

private-school enrollment nationally had fallen because of the recession, he had

seen a small upswing in applications for accreditation from for-profit schools,

with significant growth in schools for children with special needs.

Parents may be hard-pressed to see much difference between for-profit and

nonprofit independent schools. Both cost a lot, both depend on the children of

wealthy people to attend, both pay their headmasters large salaries.

But nonprofit schools enjoy generous tax advantages, including low-cost benefit

packages, property-tax exemptions and grant eligibility. They also must bridge

the gap between tuition revenue and the expense of running the institution with

donations, no surprise to parents who face frequent solicitations for pricey

galas and the ever-needy annual fund. For-profit schools pay taxes but generally

refrain from soliciting parents, instead securing money from investors who hope

to make money later, if the school is sold or the company that owns it goes

public.

It remains unclear how profitable a for-profit school can be, especially since

private corporations are not required to disclose their financial information.

But the market for private-school enrollment generally seems robust: according

to one study conducted for a new school, the number of school-age children in

households between Battery Park City and 72nd Street with annual incomes above

$500,000 soared to 15,700 in 2010, from 4,300 a decade before. According to the

study, the top dozen schools in the city — all nonprofit — have only 11,000

seats.

With real estate acquisition and construction so expensive in New York —

estimates range from $50 million to $100 million to build a top-flight school

for multiple grades — starting a school requires either a huge donation or

significant venture capital.

All the leaders of new for-profit schools believe there is money to be made —

efficiencies to be exploited, though they are loath to say as much — in running

a school in a city where parents go to extreme measures to secure their children

space in elite schools that charge more than $35,000 for kindergarten. But those

leaders are also conscious that the notion of profiting from the noble

aspirations of educating children can seem a little unsavory, especially in

light of recent scandals involving for-profit colleges and commercial companies

managing public charter schools.

“I don’t think for-profits or not-for-profits have a corner on educational

efficacy,” said Christopher Whittle, who in 1991 founded the Edison Project, a

plan to open up to 1,000 technologically advanced for-profit schools that would

operate more efficiently than public schools He is now focused on creating

Avenues: the World School, a for-profit school scheduled to open on the West

Side of Manhattan next year. “They’re both capable of really good things and

less than great things. The main difference is their capital source.”

Susan Wolford of BMO Capital Markets, a boutique investment bank, said that

for-profit schools had profit margins of 20 to 25 percent, before taxes and

interest on debt and amortization.

The key revenue drivers are tuition and enrollment. While competition is fierce

for admission to the brand-name schools, it remains to be seen if newcomers will

be able to lure the same crowds. “Parents like schools with a long history and

reputation of excellence,” said Victoria Goldman, author of “The Manhattan

Family Guide to Private Schools and Selective Public Schools.” “Certainly if

they pay $30,000 to $35,000, they want tried-and-true.”

But owners of for-profit schools say they will have more freedom to experiment

without a backlash from parents, teachers, administrators and alumni.

“There’s a can-do attitude here,” said William T. Phelps, the new headmaster of

the British International School. “If I say, ‘Can you try this out,’ 95 percent

of the time the answer is ‘Yes.’ In established schools, you try to move a

painting and there’s a backlash.”

Some of the city’s for-profit schools have been around for decades, including

the Dwight School, York Preparatory School and the Mandell School.One of the

newcomers, Claremont Preparatory, is part of a company called MetSchools, which

owns 10 schools and preschools in New York City. Among them are for-profit and

nonprofit schools, including the Rebecca School and the Aaron School, which

cater to children with developmental disabilities and rely heavily on government

money.

Claremont’s experience is a study in contradictions. It was founded in 2005 with

54 students. This year, 575 children will stretch out over the school’s 325,000

square feet. (It has a pool and a banquet hall, which can be rented for

parties.)

But the school has had three headmasters in five years and was sued last year by

a former school psychologist who said she was fired for reporting to child

welfare authorities that a student had said his mother had hit him.

In its response to the suit, Claremont denied the psychologist’s accusations and

said she had breached her contract and failed to use her training to properly

evaluate the situation. Lawyers on both sides did not return several calls for

comment.

In June, Claremont’s founder, Michael Koffler, abruptly announced that the

headmaster would be leaving, angering parents who had already put down deposits

for the fall. And while enrollment has grown, it is nowhere near the school’s

onetime goal of 1,000 students by 2007. Mr. Koffler declined to comment; a

spokeswoman said he was too busy with the start of the school year.

To attract students, the new schools often try to offer something special.

Claremont, which has little competition in its Wall Street neighborhood, has its

modern, spacious campus. The Avenues school intends to let students transfer

seamlessly among its planned 20 schools in major cities around the world — if,

for example, their parents’ high-salary jobs require them to move abroad.

The World Class Learning Academy, in the East Village, another for-profit

venture, will use the patented International Primary Curriculum, which it says

is used in 1,000 schools worldwide (5 in the United States). Originally

scheduled to open in 2011, World Class announced this spring that it would

instead start in September, only to back away from the decision soon afterward,

citing construction issues and the fact that it had enrolled only a small number

of children.

Initial plans for Avenues give a sense of where for-profit schools might try to

find savings: class size will be roughly the same as at top Manhattan schools,

but there will be fewer teachers, and they will be expected to spend a larger

percentage of their day in the classroom. One person involved in the project,

who spoke on the condition of anonymity since the plans were still fluid, said

the school also planned to pay the teachers more than the notoriously low

salaries of private-school teachers.

And administrators of for-profit schools are eager to highlight that they do not

go hat-in-hand to parents every few months. “Those donations come with strings

and baggage,” said Gabriella Rowe, head of the Mandell School.

Andrea Greystoke, the British International School founder, who has six children

of her own, said, “After paying six lots of school fees, I have a great

antipathy for fund-raising.”