|

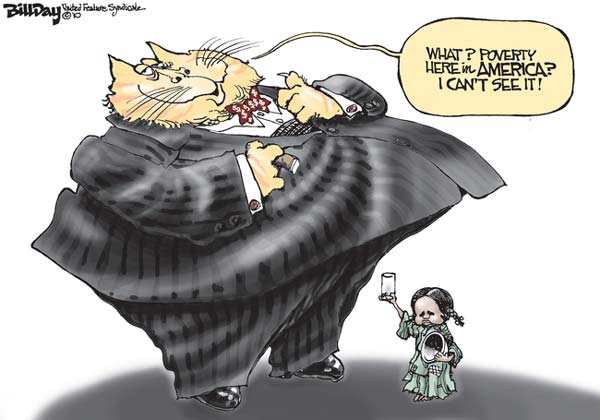

USA > History > 2010 > Economy > Poverty (I)

Bill Day

Tennessee

Cagle

15 September 2010

Los Angeles

Confronts Homelessness Reputation

December 12, 2010

The New York Times

By ADAM NAGOURNEY

LOS ANGELES — It was just past dusk in the upscale enclave of Brentwood as a

homeless man, wrapped in a tattered gray blanket, stepped into a doorway to

escape a light rain, watching the flow of people on their way to the high-end

restaurants that lined the street.

Across town in Hollywood the next morning, homeless people were wandering up and

down Sunset Boulevard, pushing shopping carts and slumped at bus stops. More

homeless men and women could be found shuffling along the boardwalks of Venice

and Santa Monica, while a few others were spotted near the heart of Beverly

Hills, the very symbol of Los Angeles wealth.

And, as always, San Julian Street, the infamous center of Skid Row on the south

edge of downtown Los Angeles, was teeming: a small city of people were making

the street their home in a warm December sun, waiting for one of the many

missions there to serve a meal.

At a time when cities across the country have made significant progress over the

past decade in reducing the number of homeless, in no small part by building

permanent housing, the problem seems intractable in the County of Los Angeles.

It has become a subject of acute embarrassment to some civic leaders, upset over

the county’s faltering efforts, the glaring contrast of street poverty and

mansion wealth, and any perception of a hardhearted Los Angeles unmoved by a

problem that has motivated action in so many other cities.

For national organizations trying to eradicate homelessness, Los Angeles — with

its 48,000 people living on the streets, including 6,000 veterans, according to

one count — stands as a stubborn anomaly, an outlier at a time when there has

been progress, albeit modest and at times fitful, in so many cities.

Its designation as the homeless capital of America, a title that people here

dislike but do not contest, seems increasingly indisputable.

“If we want to end homelessness in this country, we have to do something about

L.A.; it is the biggest nut,” said Nan Roman, the president of the National

Alliance to End Homelessness. “It has more homeless people than anyplace else.”

Neil J. Donovan, the executive director of the National Coalition for the

Homeless, said he believed that, after years of decline, there had been a slight

rise in the number of homeless nationally this year because of the economic

downturn, and that Los Angeles had led the way.

“Los Angeles’s homeless problem is growing faster than the overall national

problem,” he said, “trending upwards in every demographic, dashing every hope of

progress anywhere.”

In a reflection of the growing concern here, a task force created by the Chamber

of Commerce and the United Way of Greater Los Angeles has stepped in with a

plan, called Home for Good, to end homelessness here in five years. The idea is

to, among other things, build housing for 12,000 of the chronically unemployed

and provide food, maintenance and other services at a cost of $235 million a

year.

The proposal, based on the task force’s study of what other cities had done, was

embraced by political and civic leaders even as it served as a reminder of how

many of these plans have failed over the years.

“This is not rocket science,” said Zev Yaroslavsky of the County Board of

Supervisors. “It’s been done in New York, it’s been done in Atlanta, and it’s

been done in San Francisco.”

Part of the impetus for this most recent flurry of attention is concern in the

business and political communities that the epidemic is threatening to tarnish

Los Angeles’s national image and undercut a campaign to promote tourism,

particularly in downtown, which has been in the midst of a transformation of

sorts, with a boom of museums, concert halls, restaurants, boutiques, parks and

lofts.

The gentrification has pushed many of the homeless people south, but they can

still be seen settled on benches and patches of grass in the center of downtown.

“If you have a homeless problem, then your sense of security is diminished, and

that makes people not want to come,” said Jerry Neuman, a co-chairman of the

task force. “It’s a problem that diminishes us in many ways: the way we view

ourselves and the way other people view us.”

Fittingly enough, it was even the subject of a movie last year, “The Soloist,”

which portrayed the relationship between a Los Angeles Times columnist, Steve

Lopez, who has written extensively about the homeless, and a musician living on

the streets.

The obstacles seem particularly great in this part of the country. The warm

climate has always been a draw for homeless people. And the fact that people

sleeping outside rarely die of exposure means there is less pressure on civic

leaders to act. (In New York City, when a homeless woman known only as “Mama”

was found dead at Grand Central Terminal on a frigid Christmas in 1985, it was

front-page news that inspired a campaign to deal with the epidemic.)

The governmental structure here, of a county that includes 88 cities and a maze

of conflicting jurisdictions, responsibilities and boundaries, has defused

responsibility and made it nearly impossible for any one organization or person

to take charge.

And Los Angeles is a place where people drive almost everywhere, so there are

fewer of the reminders of homelessness — walking around a sleeping person on a

sidewalk, responding to requests for money at the corner — that are common in

concentrated cities like New York.

“It’s easy to get up in the morning, go to work, drive home and never encounter

someone who is homeless,” said Wendy Greuel, the Los Angeles city controller. “I

don’t think it’s seeped into the public’s consciousness that homelessness is a

problem.”

The homelessness task force offered its plan at a conference that attracted some

of the top elected officials here, including Mayor Antonio R. Villaraigosa and

three of the five members of the Board of Supervisors, a notable show of

political support.

“We believe that with the release of this plan, we now have a blueprint to end

chronic homelessness and veteran homelessness,” said Christine Marge, director

of housing for the United Way of Greater Los Angeles.

Yet in a time of severe budget retrenchment, the five-year goal seems daunting.

Even though the drafters of the plan say that no new money will be needed to

finance it — Los Angeles is already spending more than $235 million a year on

hospital, overnight housing and police costs dealing with the homeless —

government financing of all social services has come under assault.

“I don’t for a minute think it’s not going to require a tremendous amount of

political will to make it happen,” said Richard Bloom, the mayor of Santa

Monica. “Do I think it can happen? Yes, because I’ve seen what happens in other

cities, like New York City, Denver and Boston.”

Still, Mr. Bloom, who said he regularly attended conferences involving officials

from other communities, added: “Our numbers are way out of whack with those

numbers I hear elsewhere. It’s just so much more enormous and daunting here.”

Los Angeles Confronts

Homelessness Reputation,

NYT,

12.12.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/13/us/13homeless.html

When Home Has No Place to Park

October 3, 2010

The New York Times

By IAN LOVETT

LOS ANGELES — Every day, Diane Butler and her husband park their two

hand-painted R.V.’s in a lot at the edge of Venice Beach here, alongside dozens

of other rickety, rusted campers from the 1970s and ’80s. During the day, she

sells her artwork on the boardwalk. When the parking lot closes at sunset, she

and the other R.V.-dwellers drive a quarter-mile inland to find somewhere on the

street to park for the night.

Their nomadic existence might be ending, though. The Venice section of Los

Angeles has become the latest California community to enact strict new

regulations limiting street parking and banning R.V.’s from beach lots —

regulations that could soon force Ms. Butler, 58, to leave the community where

she has lived for four decades.

“They’re making it hard for people in vehicles to remain in Venice,” she said.

Southern California, with its forgiving weather, has long been a popular

destination for those living in vehicles and other homeless people. And for

decades, people living in R.V.’s, vans and cars have settled in Venice, the

beachfront Los Angeles community once known as the “Slum by the Sea” and famous

for its offbeat, artistic culture.

Yet even as the economic downturn has forced more people out of their homes and

into their cars, vehicle-dwellers are facing fewer options, with more

communities trying to push them out.

As nearby neighborhoods and municipalities passed laws restricting overnight

parking in recent years, Venice became the center of vehicle dwelling in the

region. More than 250 vehicles now serve as shelter on Venice streets, according

to the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority.

“The only place between Santa Barbara and San Diego where campers can park seven

blocks from the beach is this little piece of land,” said City Councilman Bill

Rosendahl, whose district includes Venice. “Over the years, it’s only gotten

worse, as every other community along the coast has adopted restrictions.”

In the past, bohemian Venice was tolerant of vehicle-dwellers, but,

increasingly, the proliferation of R.V.’s in this gentrifying neighborhood has

prompted efforts to remove them.

“The status quo is unacceptable,” said Mark Ryavec, president of the Venice

Stakeholders Association, a group of residents devoted to removing R.V.’s from

the area. “It’s time to give us some relief from R.V.’s parking on our

doorsteps.”

A bitter debate has raged between residents who want to get rid of R.V.’s and

those who want to combat the problems of homelessness in the community by

offering safe places to park and access to public bathrooms. Last year,

residents voted to establish overnight parking restrictions, but the California

Coastal Commission twice vetoed the plan.

However, a recent incident involving an R.V. owner’s arrest on charges of

dumping sewage into the street has accelerated efforts to remove

vehicle-dwellers. Starting this week, oversize vehicles will be banned from the

beach parking lots; an ordinance banning them from parking on the street

overnight could take effect within a month.

While Mr. Rosendahl supported parking restrictions, he has also secured $750,000

from the city to pay for a pilot program to house R.V.-dwellers. Modeled after

efforts in Santa Barbara and Eugene, Ore., the Vehicles to Homes program will

offer overnight parking for vehicle-dwellers who agree to meet certain

conditions, with the goal of moving participants into permanent housing.

“For people who want help, we’ll support them,” Mr. Rosendahl said. “The others

can take their wheels and go up the coast or somewhere else, God bless them.

It’s not our responsibility to be the only spot where near-homelessness is dealt

with in the state of California.”

While some have expressed interest in the program, many said they did not want

to subject themselves to curfews and oversight or had no means or desire to

return to renting. Mr. Ryavec believes few will participate.

“I will not debate that some people are mentally ill, indigent or drugged out,”

Mr. Ryavec said. “But my stance is that the bulk of these people are making a

lifestyle choice.”

Still, according to Gary L. Blasi, a law professor at the University of

California, Los Angeles, and an activist on homeless issues, most people choose

to live in vehicles only when the alternative is sleeping in a shelter or on the

street.

“The idea of carefree vagabonds is statistically false,” Professor Blasi said.

“More often, these are people who lived in apartments in Venice before they

lived in R.V.’s. The reason for losing housing is usually the loss of a job or

some health care crisis.”

Even if all the vehicle-dwellers in Venice wanted to participate, the pilot

program will accommodate only a small fraction of them. In Southern California,

though, there may not be anywhere else R.V.’s can legally park. According to

Neil Donovan, executive director of the National Coalition for the Homeless,

ordinances banning R.V.’s have spread from metropolitan areas into the suburbs

as vehicle-dwellers venture farther afield in search of somewhere to sleep.

“Communities are now forming a patchwork of ordinances, which virtually

prohibits a geographic cure to the situation,” Mr. Donovan said. “If you’re in a

community and they tell you to leave, you can’t just go to the next community,

because they establish similar ordinances, especially in California.”

Mr. Donovan said vehicle-dwellers often end up on the street after their

vehicles are towed or become inoperable. When his organization surveyed tent

camps in California, they found that many residents had come from R.V.’s.

Vehicle-dwellers in Venice are now considering their options, but few expressed

any intention of leaving.

“They can keep throwing more laws at us, but we’re not just going to go away,”

said Mario Manti-Gualtiero, who lost his job as an audio engineer and now lives

in an R.V. “We can’t just evaporate.”

When Home Has No Place

to Park, NYT, 3.10.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/04/us/04rv.html

At East Village Food Pantry,

the Price Is a Sermon

September 28, 2010

The New York Times

By JOSEPH BERGER

The shopping carts are lined up hours early in Tompkins Square Park, not far

from the dog run, where the East Village’s more genteel residents are unleashing

retrievers and beagles and chatting animatedly. The poor or elderly waiting on

benches to get the free food that comes with a dose of the Gospel seem more lost

in their own thoughts, even though many meet every Tuesday.

A guard, Mike Luke, a powerhouse known as Big Mike who himself was a consumer at

church pantries until he found religion and decided to work for “the man

upstairs,” manages the crowd with crisp authority until the 11 a.m. service

starts across the street at the Tompkins Square Gospel Fellowship. There is

nervous tension because only the first 50 will get in, and suddenly two women

are squabbling over a black cart.

“How do you know that’s your cart?” Big Mike firmly asks one, a fair question

since the carts look alike. But the mystery is cleared up with the discovery of

an orphaned gray cart.

Inside the worship hall, the 50 men and women sit in neat rows in front of a

pulpit and a painting of a generic waterfall while a pianist softly plays hymns.

Their carts are reassembled in neat rows as well.

The room has the shopworn air of Sergeant Sarah Brown’s Save-a-Soul Mission in

“Guys and Dolls.” One almost expects Stubby Kaye to get up and sing “Sit Down,

You’re Rockin’ the Boat.” But people don’t mind having to sit through a sermon

as the price of admission, and few have jobs they need to run to. While they

wait, volunteers fill each cart with a couple of bread loaves — redolent of a

Gospel miracle, except these are ciabatta and 10-grain — a couple of bananas, a

couple of less-than-freshly-picked ears of corn, a box of eggs, a box of

blueberries, even an Asian pear.

The food is donated by Trader Joe’s, the gourmet and organic food purveyor,

which has a store nearby. It usually feeds the kinds of professionals who use

the dog run, but it provides the fellowship with a wealth of unsold baked goods,

fruit and vegetables.

The fellowship was started 115 years ago as a mission to the immigrant Jews of

the Lower East Side but now mostly serves the black, Latino and Asian poor. The

East Village has several other pantries that dispense food without sermons;

their food is government-financed and so must be religion-free. The fellowship

started its giveaways in January and now feeds 250 people during three services

on Tuesdays — one in Chinese — and a single evening service on Sundays and

Wednesdays.

The mission is run by the Rev. Bill Jones, a lively ordained Baptist minister

from the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina.

“People are not only hungry for food, but hungry for the word of God,” Mr. Jones

said. “There’s not just a physical need but a spiritual need.”

Nevertheless, he is aware of the actual hunger. “If you wait for three hours to

get $25 worth of groceries,” he said, “you have a need.”

He affirms that thought to the waiting crowd in a stentorian drawl.

“You all get blueberries today,” he announces. “Some of you get eggs. If you

don’t get eggs, don’t be upset. You neighbor is getting eggs, so be grateful.”

The people who come include Rafael Mercado, 52, who lost his job as a mailroom

clerk four years ago.

“I don’t have the kind of money now to go shopping,” he said, “so I go to many

pantries.” Another is Asia Feliciano, 37, a single mother with a lush head of

cornrow braids. She and her sons, Trevor, 5, and Jordan, 3, live in a nearby

shelter, and they stumbled upon the mission in August while panhandling.

“It puts food on our plates every night,” she said.

Mr. Jones begins the service with a prayer — “Heavenly father, we are so

grateful for the provisions you have brought us for another day.” He then offers

a lesson from the Gospel of John, in which Jesus tells the disciples to love one

another. With ardor that is not quite brimstone, Mr. Jones urges listeners to

love one another as well, not give in to temptations and pray to remain faithful

to God.

Many among the 50 sit stone-faced. But some clearly listen. Though she comes

mostly for the food, Ms. Feliciano indicates that the worship has subversively

taken hold.

“When I have to sit through the service, it opens my eyes,” she said. “So I

started reading the Bible and I asked them for a Bible, and they gave me one.”

Jim Dwyer is on leave.

At East Village Food

Pantry, the Price Is a Sermon, NYT, 28.9.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/29/nyregion/29about.html

We Haven’t Hit Bottom Yet

September 24, 2010

The New York Times

By BOB HERBERT

Wallingford, Conn.

Marcus Vogt is 20 years old and homeless. Or, as he puts it, “I’m going through

a couch-surfing phase.”

Mr. Vogt is a Wal-Mart employee but he was injured in a car accident and was

unable to work for a couple of months. With no income and no health insurance,

he quickly found himself unable to pay the rent. Even meals were hard to come

by.

(His situation is quite a statement about real life in the United States in the

21st century. On the same day that I spoke with Mr. Vogt, Forbes magazine came

out with its list of the 400 most outrageously rich Americans.)

I met Mr. Vogt at Master’s Manna, a food pantry and soup kitchen here that also

offers a variety of other services to individuals and families that have fallen

on hard times. He told me that his cellphone service has been cut off and he has

more than $3,000 in medical bills outstanding. But he was cheerful and happy to

report that he’s back at work, although it will take at least a few more

paychecks before he’ll have enough money to rent a room.

Other folks who make their way to Master’s Manna are not so upbeat. The Great

Recession has long since ended, according to the data zealots in their

windowless rooms. But it is still very real to the millions of men and women who

wake up each morning to the grim reality of empty pockets and empty cupboards.

Wallingford is nobody’s definition of a depressed community. It’s a middle-class

town on the Quinnipiac River. But the number of people seeking help at Master’s

Manna is rising, not falling. And when I asked Cheryl Bedore, who runs the

program, if she was seeing more clients from the middle class, she said: “Oh,

absolutely. We have people who were donors in the past coming to our doors now

in search of help.”

The political upheaval going on in the United States right now is being driven

by the economic upheaval. It’s sometimes hard to see this clearly amid the

craziness and ugliness stirred up by the professional exploiters. But the

essential issue is still the economy — the rising tide of poor people and the

decline of the middle class. The true extent of the pain has not been widely

chronicled.

“The minute you open the doors, it’s like a wave of desperation that’s hitting

you,” said Ms. Bedore. “People are depressed, despondent. They’re on the edge,

especially those who have never had to ask for help before.”

In recent weeks, a few homeless people with cars have been showing up at

Master’s Manna. Ms. Bedore has gotten permission from the local police

department for them to park behind her building and sleep in their cars

overnight. “We’ve been recognized as a safe haven,” she said.

In two of the cars, she said, were families with children.

It’s not just joblessness that’s driving people to the brink, although that’s a

big factor. It’s underemployment, as well. “For many of our families,” said Ms.

Bedore, “the 40-hour workweek is over, a thing of the past. They may still have

a job, but they’re trying to survive on reduced hours — with no benefits. Some

are on forced furloughs.

“Once you start losing the income and you’ve run through your savings, then your

car is up for repossession, or you’re looking at foreclosure or eviction. We’re

a food pantry, but hunger is only the tip of the iceberg. Life becomes a

constant juggling act when the money starts running out. Are you going to pay

for your medication? Or are you going to put gas in the car so you can go to

work?

“Kids are going back to school now, so they need clothes and school supplies.

Where is the money for that to come from? The people we’re seeing never expected

things to turn out like this — not at this stage of their lives. Not in the

United States. The middle class is quickly slipping into a lower class.”

Similar stories — and worse — are unfolding throughout the country. There are

more people in poverty now — 43.6 million — than at any time since the

government began keeping accurate records. Nearly 15 million Americans are out

of work and home foreclosures are expected to surpass one million this year. The

Times had a chilling front-page article this week about the increasing fear

among jobless workers over 50 that they will never be employed again.

The politicians seem unable to grasp the immensity of the problem, which is why

the policy solutions are so woefully inadequate. During my conversations with

Ms. Bedore, she dismissed the very thought that the recession might be over.

“Whoever said that was sadly mistaken,” she said. “We haven’t even bottomed-out

yet.”

Charles M. Blow is off today.

We Haven’t Hit Bottom

Yet, NYT, 24.9.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/25/opinion/25herbert.html

Two Different Worlds

September 17, 2010

The New York Times

By BOB HERBERT

I didn’t notice much when a terrific storm slammed into parts of New York

City on Thursday evening. I was working at my computer in a quiet apartment on

the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The skies darkened and it began to rain, and I

could hear thunder. But that’s all. I made a cup of coffee and kept working.

While I remained oblivious, the storm took a frightening toll in the boroughs of

Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island. A woman who was trying to walk home with her

10-year-old daughter from Prospect Park in Brooklyn told me the next day that it

had been the most harrowing experience of her life. “With the wind and the rain,

it was like being trapped in a car wash,” she said. “And then a tree crashed

down on a car right in front of us.”

They ran soaking wet up the steps of a brownstone and the owner, a stranger, let

them come inside.

The winds reached tornadolike intensity. Trees were uprooted and blown into

electrical power lines. Roofs were blown from buildings. One woman was killed,

and several neighborhoods were devastated.

I eventually heard about it on the news.

The movers and shakers of our society seem similarly oblivious to the terrible

destruction wrought by the economic storm that has roared through America.

They’ve heard some thunder, perhaps, and seen some lightning, and maybe felt a

bit of the wind. But there is nothing that society’s leaders are doing — no

sense of urgency in their policies or attitudes — that suggests they understand

the extent of the economic devastation that has come crashing down like a plague

on the poor and much of the middle class.

The American economy is on its knees and the suffering has reached historic

levels. Nearly 44 million people were living in poverty last year, which is more

than 14 percent of the population. That is an increase of 4 million over the

previous year, the highest percentage in 15 years, and the highest number in

more than a half-century of record-keeping. Millions more are teetering on the

edge, poised to fall into poverty.

More than a quarter of all blacks and a similar percentage of Hispanics are

poor. More than 15 million children are poor.

The movers and shakers, including most of the mainstream media, have paid

precious little attention to this wide-scale economic disaster.

Meanwhile, the middle class, hobbled for years with the stagnant incomes that

accompany extreme employment insecurity, is now in retreat. Joblessness, home

foreclosures, personal bankruptcy — pick your poison. Median family incomes were

5 percent lower in 2009 than they were a decade earlier. The Harvard economist

Lawrence Katz told The Times, “This is the first time in memory that an entire

decade has produced essentially no economic growth for the typical American

household.”

I don’t know what it will take, maybe a full-blown depression, for policy makers

to decide that they need to take extraordinary additional steps to cope with

this drastic economic and employment emergency. Nothing currently on the table

will turn things around in a meaningful way. We’re facing a jobs deficit of

about 11 million, which is about how many new ones we’d have to create just to

get our heads above water. It will take years — years — just to get employment

back to where it was when the recession struck in December 2007.

If Republicans take over the policy levers, forget about it. The party of Palin,

Limbaugh and Boehner — with its tax cuts for the rich and obsession with the

deregulatory, free-market zealotry that brought us the Great Recession — will

only accelerate the mass march into poverty.

The G.O.P. wants to further shred the safety net, wants to give corporations

even greater clout over already debased workers, and wants to fatten the coffers

of the already obscenely rich.

While working people are suffering the torments of joblessness, underemployment

and dwindling compensation, corporate profits have rebounded and the financial

sector is once again living the high life. This helps to keep the people at the

top comfortably in denial about the extent of the carnage.

Millions of struggling voters have no idea which way to turn. They are suffering

under the status quo, but those with any memory at all are afraid of a rerun of

the catastrophic George W. Bush era. An Associated Press article, based on

recent polling, summed the matter up: “Glum and distrusting, a majority of

Americans today are very confident in — nobody.”

What is desperately needed is leadership that recognizes the depth and intensity

of the economic crisis facing so many ordinary Americans. It’s time for the

movers and shakers to lift the shroud of oblivion and reach out to those many

millions of Americans trapped in a world of hurt.

Two Different Worlds,

NYT, 17.9.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/18/opinion/18herbert.html

Number of Families in Shelters Rises

September 11, 2010

The New York Times

By MICHAEL LUO

PROVIDENCE, R.I. — For a few hours at the mall here this month, Nick

Griffith, his wife, Lacey Lennon, and their two young children got to feel like

a regular family again.

Never mind that they were just killing time away from the homeless shelter where

they are staying, or that they had to take two city buses to get to the shopping

center because they pawned one car earlier this year and had another

repossessed, or that the debit card Ms. Lennon inserted into the A.T.M. was

courtesy of the state’s welfare program.

They ate lunch at the food court, browsed for clothes and just strolled,

blending in with everyone else out on a scorching hot summer day. “It’s exactly

why we come here,” Ms. Lennon said. “It reminds us of our old life.”

For millions who have lost jobs or faced eviction in the economic downturn,

homelessness is perhaps the darkest fear of all. In the end, though, for all the

devastation wrought by the recession, a vast majority of people who have faced

the possibility have somehow managed to avoid it.

Nevertheless, from 2007 through 2009, the number of families in homeless

shelters — households with at least one adult and one minor child — leapt to

170,000 from 131,000, according to the Department of Housing and Urban

Development.

With long-term unemployment ballooning, those numbers could easily climb this

year. Late in 2009, however, states began distributing $1.5 billion that has

been made available over three years by the federal government as part of the

stimulus package for the Homeless Prevention and Rapid Re-Housing Program, which

provides financial assistance to keep people in their homes or get them back in

one quickly if they lose them.

More than 550,000 people have received aid, including more than 1,800 in Rhode

Island, with just over a quarter of the money for the program spent so far

nationally, state and federal officials said.

Even so, it remains to be seen whether the program is keeping pace with the

continuing economic hardship.

On Aug. 9, Mr. Griffith, 40, Ms. Lennon, 26, and their two children, Ava, 3, and

Ethan, 16 months, staggered into Crossroads Rhode Island, a shelter that

functions as a kind of processing and triage center for homeless families, after

a three-day bus journey from Florida.

“It hit me when we got off the bus and walked up and saw the Crossroads

building,” Ms. Lennon said. “We had all our stuff. We were tired. We’d already

had enough, and it was just starting.”

The number of families who have sought help this year at Crossroads has already

surpassed the total for all of 2009. Through July, 324 families had come needing

shelter, compared with 278 all of last year.

National data on current shelter populations are not yet available, but checks

with other major family shelters across the country found similar increases.

The Y.W.C.A. Family Center in Columbus, Ohio, one of the largest family shelters

in the state, has seen an occupancy increase of more than 20 percent over the

last three months compared with the same period last year. The UMOM New Day

Center in Phoenix, the largest family shelter in Arizona, has had a more than 30

percent increase in families calling for shelter over the last few months.

Without national data, it is impossible to say for certain whether these are

anomalies. Clearly, however, many families are still being sucked into the

swirling financial drain that leads to homelessness.

The Griffith family moved from Rhode Island to Florida two years ago after Mr.

Griffith, who was working as a waiter at an Applebee’s restaurant, asked to be

transferred to one opening in Spring Hill, an hour north of Tampa, where he

figured the cost of living would be lower.

He did well at first, earning as much as $25 an hour, including tips. He also

got a job as a line cook at another restaurant, where he made $12 an hour.

The family eventually moved into a three-bedroom condominium and lived the

typical suburban life, with a sport-utility vehicle and a minivan to cart around

their growing family.

In January, however, the restaurant where Mr. Griffith was cooking closed. Then

his hours began drying up at Applebee’s. The couple had savings, but squandered

some of it figuring he would quickly find another job. When he did not, they

were evicted from their condo.

They lived with Ms. Lennon’s mother at first in her one-bedroom house in Port

Richey, Fla., but she made it clear after two months that the arrangement was no

longer feasible. The family moved to an R.V. park, paying $186 a week plus

utilities. By late July, however, they had mostly run out of options.

They called some 100 shelters in Florida and found that most were full; others

would not allow them to stay together.

They considered returning to Rhode Island. An Applebee’s in Smithfield agreed to

hire Mr. Griffith. They found Crossroads on the Internet and were assured of a

spot. Using some emergency money they had left and $150 lent by relatives, they

bought bus tickets to Providence.

Now, the family is crammed into a single room at Crossroads’ 15-room family

shelter, which used to be a funeral home. All four sleep on a pair of single

beds pushed together. There is a crib for Ethan, but with all the turmoil, he

can now fall asleep only when next to his parents. A lone framed photograph of

the couple, dressed up for a night out, sits atop a shelf.

The living conditions are only part of the adjustment; there is also the

shelter’s long list of rules. No one can be in the living quarters from 10 a.m.

to 4:30 p.m. The news is even off-limits as television programming in the common

area. Residents were recently barred from congregating around the bench outside.

Infractions bring write-ups; three write-ups bring expulsion.

The changes have taken a toll on the family in small and large ways. Ethan has

taken to screaming for no reason. Ava had been on the verge of being

potty-trained, but is now back to diapers. Their nap schedules and diets are a

mess. Their parents are squabbling more and have started smoking again.

Mr. Griffith found that he could work only limited hours at his new job because

of the bus schedule. The family did qualify last week for transitional housing,

but that usually takes a month to finalize. They are still pursuing rapid

rehousing assistance.

Others at the shelter with no job prospects face a steeper climb meeting the

requirements.

Every few days, new families arrive. A few hours after the Griffiths got back

from the mall, a young woman pushing a stroller with a toddler rang the shelter

doorbell, quietly weeping.

Number of Families in

Shelters Rises, NYT, 11.9.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/12/us/12shelter.html

Wal-Mart Gives $2 Billion to Fight Hunger

May 12, 2010

The New York Times

By STEPHANIE STROM

The Wal-Mart Corporation announced plans on Wednesday to contribute $2

billion in cash and food to the nation’s food banks, one of the largest

corporate gifts on record.

Over the next five years, the giant retail company will distribute some 1.1

billion pounds of food to food banks and provide $250 million to help those

organizations buy refrigerated trucks, improve storage and develop better

logistics.

“Hunger is just a huge problem, and as the largest grocer in the country, we

need to be at the head of the pack in doing something about it,” said Margaret

McKenna, president of the Wal-Mart Foundation.

While the economy seems to be turning around, the number of people turning to

charities to help put food on their tables continues to grow. A recent survey by

Feeding America found that 37 million people a year now use its national network

of food banks, a 46 percent increase from 2006. The survey drew on interviews

with more than 61,000 people who use food banks, as well as reports from 37,000

food banks across the country.

Put another way, 1 in every 8 Americans uses a food bank to make ends meet, the

survey said.

More than one-third of those surveyed said they would not have been able to pay

for basics like rent, utilities and medical care without relying on food banks

to offset the cost of their meals — and more than a third said at least one

person in their household was working.

“It is not just the unemployed that are going hungry,” said Vicki B. Escarra,

chief executive of Feeding America.

Wal-Mart began taking on hunger as a cause in 2005, when it distributed 9.9

million pounds of food to food banks; last year, it provided 116.1 million

pounds of food. The company also has donated the services of its staff to help

food banks improve lighting and refrigeration, and develop ways to increase the

amount of fresh food on their shelves.

“We’ve learned a lot about this problem and the kinds of things we can do to

help,” Ms. McKenna said. “We’ve learned, for instance, that there is a huge gap

in terms of the protein and fresh produce that food banks can deliver, so we’ve

learned how to fast-freeze things like meat and dairy. You can’t put 100 pounds

of bananas on a truck that isn’t refrigerated and expect them to be edible for

long.”

Almost one-third of the food Wal-Mart is donating this year will be fresh, and

one of the first cash gifts out of the new grant will go to increasing the

number of refrigerated trucks delivering food to food banks. “These are the

types of resources we don’t get much from other sources,” Ms. Escarra said.

Wal-Mart and other companies currently are focused on how to get food to

children to expose them to fruits, vegetables and meats that traditionally have

not been available to poor families because of limited supplies or high cost.

For instance, the Target Corporation on Tuesday announced a $2.3 million program

to create pantries in schools that can be used to teach children about good

nutrition at the same time they are fed.

Target provided an additional $1.2 million to Feeding America to support other

school-based feeding programs.

Ms. McKenna said she was concerned about getting food during the summer to

children who rely on school breakfast and lunch programs. “We know about sending

kids home with backpacks of food for the weekends,” she said, “but what do we do

to feed them when they aren’t going to school?”

Wal-Mart Gives $2

Billion to Fight Hunger, NYT, 12.5.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/13/us/13gift.html

City’s Homeless Services Commissioner Resigns

April 19, 2010

The New York Times

By JULIE BOSMAN

Robert V. Hess, the city’s commissioner of homeless services, said on Monday

that he will leave his post after four years of overseeing one of the Bloomberg

administration’s most demanding agencies.

Mr. Hess said he had accepted a position at the Doe Fund, a nonprofit

organization that helps the homeless find work and housing. He will be replaced

by Seth Diamond, an executive deputy commissioner at the Human Resources

Administration.

In an interview, Mr. Hess said that after he received the offer, he decided it

was time to move on.

“I committed to the mayor to serve the second term, and I did that,” he said. “I

think it’s the right timing for the administration. I’m very proud of the work

that we’ve done.”

Mr. Hess, 54, is the latest high-ranking figure to leave the Bloomberg

administration, in what aides to the mayor have privately described as a

deliberate house cleaning intended to bring fresh faces into City Hall and clear

out weak performers.

Since Mr. Bloomberg decided to seek a third term last fall, he has announced the

departure of 16 high-level aides, many of them agency commissioners, a level of

turnover without precedent during his time in office. The mayor prizes loyalty

and stability — most top aides have remained with him eight years — but became

convinced that he needed to replace much of his cabinet to ensure a successful

third term.

In recent months, Mr. Hess has appeared to be under increasing pressure. During

the four years he has overseen the Department of Homeless Services, the number

of people living in shelters grew to more than 36,000 people from 31,000. In

October, the population in the city shelter system reached an all-time high, in

large part because of the large numbers of families seeking shelter.

Mr. Hess said he attributed the higher-than-usual intake to the poor economy.

“I would just remind folks that the Department of Homeless Services is the final

safety net for New Yorkers,” he said. “Many, many factors outside of this

department’s control determines who ends up at the front door of the shelter

system.”

In his new position at the Doe Fund, Mr. Hess will build the national profile of

one of its programs, called Ready, Willing and Able.

Mr. Bloomberg is close to the group’s founder, George McDonald, and has

personally donated at least $325,000 to the Doe Fund through the Carnegie

Corporation of New York. The donations are technically anonymous but widely

known to be from the mayor, records show.

When Mr. Hess was appointed commissioner in April 2006, he inherited a number of

problems, including a flawed rent subsidy program that was shut down a year

after he came to the agency. That was replaced by another rent assistance

program, Advantage, which is in the process of being drastically revamped.

And Mr. Hess has been dogged by an outspoken group of elected officials and

advocates for the homeless, who seemed to oppose the administration and its

policies at every turn — frequently with placards and microphones on the steps

of City Hall. He was also unable to deliver on one of Mr. Bloomberg’s grandest

goal on homelessness — reducing it by two-thirds in five years. The five years

ran out in 2009.

But Mr. Hess did have his successes, some of them significant.

An Army veteran, Mr. Hess directed his department to focus on housing homeless

veterans, renovating shelters specifically for their use and building new ones.

Street homelessness throughout the city has been drastically reduced in the last

several years, the result of aggressive street outreach by the city and its

contracted nonprofit providers. According to the city’s annual point-in-time

count of the street homeless, the overall number of people living on the street

and in the subways has decreased by 29 percent since 2005.

In an interview, Linda I. Gibbs, the deputy mayor for health and human services,

praised the work that Mr. Hess has done. But she conceded that the growth in

homeless families in the last four years has been “a frustration.”

“We, as a collective team, have been disappointed that we haven’t seen the

reduction in homeless families," she said. “Nobody predicted the double whammy

of the burst of the housing bubble and the recession and the job loss all

combined. So that’s put a huge strain on the homeless family system in

particular.”

Mr. Hess, a former high-ranking director of homeless services in Philadelphia,

will be replaced by Mr. Diamond, a longtime city official who grew up in New

York, but has relatively little experience working on homelessness.

Mr. Diamond, 47, has devoted much of his career to welfare reform, serving under

Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani in the Human Resources Administration, the city’s

welfare agency.

“Homelessness is not welfare — there are significant differences, and I

recognize that,” Mr. Diamond said in an interview. “But there’s also significant

overlap, both in sort of the mission and in the approach. And I think even

though I haven’t worked directly in the homelessness system, I think I have

enough experience that I can do well there.”

Mr. Diamond said that he hoped to import more of the work-based philosophy that

dominates the city’s welfare agency to the homeless services system.

“What we’ve done there, which I think is applicable in a lot of ways to the

homeless system, is setting high expectations for people, supporting them as

they try and reach those expectations, strongly supporting people who go to

work, and having some consequences for people who fail to take advantage of some

of the opportunities that we make available,” he said. “That’s the philosophy

that we’ve tried in the welfare area, being very aggressive about insisting that

people who can work go to work, providing a range of opportunities and supports

for people as they try and go to work, giving them stronger support even after

they enter the employment market. And a lot of that philosophy, I think, is

applicable to the shelter system.”

Mr. Diamond, a native New Yorker, grew up on Roosevelt Island and attended

Stuyvesant High School. He will begin as commissioner at homeless services next

week.

City’s Homeless Services

Commissioner Resigns, NYT, 19.4.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/20/nyregion/20homeless.html

3-Day Effort Aims for Accurate Census of Homeless

March 31, 2010

Filed at 2:50 p.m. ET

The New York Times

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

SEATTLE (AP) -- Thousands of U.S. Census workers have fanned out to soup

kitchens, city streets and homeless shelters this week in an attempt to count

the nation's homeless, an operation that officials are hoping yields the most

accurate count yet.

The Census Bureau mobilized a small army of enumerators -- the people that count

-- for the three-day operation that wraps up Wednesday. In San Francisco alone,

800 people canvassed 1,700 streets, said Michael Burns, deputy regional director

for the Seattle region. In the Puget Sound area of Washington state, 700 workers

are being dispatched. Enumerators hit both city and rural streets.

But counting the nation's homeless population remains challenging for the

Census, which uses home addresses to send its decennial questionnaire to U.S.

residents. Moreover, the actual questionnaire doesn't have an option for people

without a home.

There's also no agreed definition of homelessness among federal agencies, Burns

said.

Because of that, for the second census in a row, the bureau partnered with

service providers -- faith-based soup kitchens, advocacy groups, shelters and

others -- across the country to reach out and pinpoint areas where the homeless

gather.

In Seattle, information booths have been set up in hygiene centers, for example.

And even after the three-day operation ends, some more outreach will be

conducted.

''That close alliance, working with people at the grass roots levels ... I think

it's definitely going to make for a more accurate count. We're working with

people who know where (the homeless) stay at night,'' Burns said.

The bureau goes beyond the questionnaire to tally the number of people with no

home, and it keeps a separate data set for it.

Reta Stevenson, who was enjoying a game of pinochle at the Family & Adult

Service Center in Seattle, said she had turned down the census workers four

times, but ''I figured if I'd do it, they would leave me alone.''

The 45-year-old, who has been homeless since 1984, said the worker didn't really

explain why she needed to be counted, besides saying she needed to be counted.

She also got a free mug.

Behind the count is money. More than $440 billion will be distributed based on

the Census data. More than $20 billion will go to the U.S. Department of Housing

and Urban Development, according to an analysis by the Brookings Institute. HUD

often works with people with no permanent shelter.

The history between the Census and the homeless, though, is not without

controversy. The last two censuses yielded complaints about how the government

handled the count.

In 1992, Baltimore and San Francisco and a group of homeless advocates sued,

wanting the Census to recount. They charged that the bureau deliberately failed

to count thousands of homeless people, when its tally spanned just one night, in

order to reduce the federal aid available to the homeless.

After the 2000 Census, lawmakers demanded that the Census say exactly how many

homeless people it found, instead of grouping them into a less specific category

called ''other noninstitutionalized group quarters.''

Some of the tensions have not eased, said Neil Donovan, executive director of

the National Coalition for the Homeless. ''Not at the level of decision making,

not at the national level where the resources are, where the resources are

committed,'' Donovan said.

His group's concerns with the 2000 Census included that drop-in centers, health

care facilities and outreach programs were not included. He said the Census has

promised improvement this time around, but that won't be seen until a year or

more from now, when the data is tallied and released.

Undercounting remains a concern for Donovan. He said homeless advocates, HUD and

others have estimated higher homeless populations than what the Census has

tallied.

But in Los Angeles, Herbert L. Smith, president and chief executive of the Los

Angeles Mission in the city's Skid Row district, praised the Census Bureau's

efforts to count members of the city's homeless population.

''They heard the criticisms from the last go-around and I think they're trying

to address these as best they can,'' Smith said. ''They have really touched all

the bases in trying to make the count as accurate as possible.''

The bureau was also hiring former homeless people who graduated from the

Mission's addiction programs to guide census takers through encampments later

this week, Smith said.

Back in Seattle, one thing remained certain to Alison Eisinger, whose

Seattle-King County Coalition on Homelessness has conducted an annual one-night

count for the past three decades.

''We know by that experience you'll always have an undercount,'' she said.

------

Associated Press Writer Jacob Adelman in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

3-Day Effort Aims for

Accurate Census of Homeless, NYT, 31.3.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2010/03/31/us/AP-US-Census-Homeless.html

Families Struggle to Afford Food, Survey Finds

January 26, 2010

The New York Times

By JASON DePARLE

WASHINGTON — Nearly one in five Americans said they lacked the money to buy

the food they needed at some point in the last year, according to a survey

co-sponsored by the Gallup organization and released Tuesday by an anti-hunger

group.

The numbers soared at the start of the recession, but dipped in 2009 despite the

continuing rise in unemployment. The anti-hunger group, the Food Research and

Action Center, attributed that trend to falling food prices, an increasing use

of food stamps and a rise in the amount of the food stamps benefit.

More than 38 million Americans — one in eight — now receive food stamps, a

record high.

The unusually large survey, which covered more than a half-million people,

offers the most recent snapshot of hunger-related problems. And it is the first

survey big enough to provide data on each of the nation’s 435 Congressional

districts and Washington, D.C.

Indeed, its most interesting finding may be just how broad a problem food

affordability has become. In 45 states and 311 Congressional districts, 15

percent or more of those surveyed said they had recently lacked money to buy

enough food.

“While there is certainly more hardship in some areas than in others, the data

also show that this is a nearly universal problem,” said James D. Weill, the

hunger group’s president.

Efforts to measure hunger-related problems often spawn political disputes, and

this one may do so as well. Some conservative critics have accused liberals of

exaggerating the problems to justify increased government spending. Others have

accused the conservative critics of ignoring the problem’s depth.

Avoiding the word “hunger,” the Agriculture Department releases an annual survey

of what it now calls “food insecurity.” Its interviewers ask up to 18 nuanced

questions about how often people skipped meals, cut portions or worried about

running out of food.

Its most recent data, for 2008, found that 14.6 percent of Americans lacked

consistent access to sufficient food, the highest in the survey’s 14-year

history.

The Gallup survey asked just one question: “Have there been times in the last

month when you did not have enough money to buy food that you or your family

needed?” But it has been asking 1,000 people nearly every day for the past two

years, producing a sample size much larger than the government’s and one that

can track monthly trends.

In the fourth quarter of 2009, 18.5 percent of Americans said they had

experienced problems in being able to afford food, down from 19.5 percent at the

end of 2008. Among families with children, the rates were significantly higher,

at 24.1 percent nationally in the most recent quarter.

Mississippi had the largest number of people with what the report called “food

hardship” (26.2 percent), while North Dakota had the lowest (10.6 percent).

Despite the variation, the data suggests a problem that few areas of the country

escape. Of the 100 largest metropolitan areas, 82 had food hardship rates of 15

percent or more. Likewise, only 23 Congressional districts had a food hardship

rate of less than 10 percent, and 139 had rates of more than 20 percent.

The survey found the biggest problems in the South Bronx. In New York’s 16th

District, nearly 37 percent of the residents answered yes when asked if they had

lacked the money to buy needed food.

Last year’s federal stimulus package, the American Recovery and Reinvestment

Act, temporarily increased the average food stamps benefit by 18 percent, to

about $130 a month for each member of a household.

The hardship data is part of the Gallup Healthways Well-Being Index, which poses

many questions about physical and mental health. (Gallup’s partner in the

project, Healthways, is a disease management company.)

The food research group bought the data when it learned that the survey included

a question about food-related hardships.

Families Struggle to

Afford Food, Survey Finds, NYT, 26.1.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/26/us/26food.html

A Fight for the Homeless and Against Authority

January 12, 2010

The New York Times

By JESSE McKINLEY

SAN LUIS OBISPO, Calif. — Burly, bearded and gleefully obscene, Dan de Vaul

does not look the part of the bleeding-heart homeless advocate, sporting as he

does a feather-topped cowboy hat, a large collection of guns and a bushel of

hoary wisecracks.

But for nearly a decade, Mr. de Vaul has been housing dozens of homeless men and

women in a farmhouse and a collection of tents, trailers and sheds spread around

his 72-acre ranch here on the outskirts of this city in central California.

Mr. de Vaul says he is simply doing the work his county cannot or will not do.

But officials say that the housing at Mr. de Vaul’s ranch, known as Sunny Acres,

is substandard, often illegal, and rife with dangerous code violations,

including missing fire detectors and faulty wiring.

Now Mr. de Vaul faces possible jail time, and his activities are sharply

dividing residents of San Luis Obispo and the surrounding county, even as the

county’s surging homeless population — estimated to be 3,800 people — outstrips

the capacity of its shelters, which have about 125 beds.

The feud reached a boiling point in recent weeks after Mr. de Vaul’s conviction

in November on two misdemeanors related to code violations, a judgment that the

authorities had hoped might cajole Sunny Acres into compliance. But Mr. de Vaul

refused a deal for probation and has since been sentenced to 90 days in jail and

fined $1,000 by a judge, who called Mr. de Vaul’s behavior “irresponsible and

arrogant.”

Mr. de Vaul was bailed out of jail, pending an appeal, by a juror who said she

regretted her vote to convict him.

“He’s chosen to take in this undesirable population that most of us turn our

heads to,” said the juror, Mary Partin, an office manager. “I had to do the

right thing.”

But critics question Mr. de Vaul’s motives and methods, like charging tenants

$300 a month for often meager shelter and asking them to perform five hours of

odd jobs a week, like splitting wood, cooking and housework. Others wonder

whether Mr. de Vaul is fighting to do good works or merely obsessed with

sticking his thumb in the eye of authority.

“I believe he truly does care for the people he takes in,” said Bruce Gibson,

the outgoing chairman of the San Luis Obispo County Board of Supervisors. “And

there’s only one thing he cares more about. And that’s fighting with the

county.”

Mr. de Vaul admits to enjoying battling local officials, but he also says he has

been shaken by his prosecution.

“What I’m saying is that I’m in over my head,” Mr. de Vaul said. “And because I

don’t like authority, I’m not going to give up.”

Mr. de Vaul is one of a handful of people who have taken the problem of

homelessness into their own hands in California, often running afoul of

officials. Last summer, the police disbanded an encampment in Sacramento pitched

with the permission of a private property owner, while in Loomis, Calif., a

couple was cited in November for allowing a homeless family to park in a lot the

couple owned.

A ramshackle compound that abuts a row of suburban homes, Mr. de Vaul’s ranch is

not much to look at. A converted dairy barn serves as a kitchen. Cars and trucks

sit in a dirt parking lot, while rusting equipment — bulldozers, a fire truck —

dots the surrounding fields, where the ranch’s cows also make their homes.

Mr. de Vaul, 66, still limps from an old dune buggy accident and lives in the

attic of a barn stuffed with cars and tools; the 101-year-old farmhouse where he

grew up houses homeless people.

Neighbors say they are sympathetic to the homeless but have complained

repeatedly about Mr. de Vaul’s activities at the ranch, including stockpiling

vehicles.

“People say it’s all about the view,” said Christine Mulholland, a neighbor and

former city councilwoman. “But the fact is I have windows in my house, and, yes,

when I look out my window, I see his property.”

Mr. de Vaul’s family had rented the Sunny Acres ranch since the 1930s. One day

in the 1980s, Mr. de Vaul was digging a well at another family property when a

ragged-looking man asked if he could park a camper there. Mr. de Vaul agreed.

About a week later, Mr. de Vaul noticed another man on the property, who turned

out to be a high school friend. He was also a Vietnam veteran and a

schizophrenic.

“No one else is going to help him,” Mr. de Vaul recalled thinking.

Mr. de Vaul bought the Sunny Acres ranch in 2002, and started allowing dozens of

homeless people to live there. Now there are about 30, including Daniel

Brainerd, 45, who came to the ranch after leaving a shelter in Santa Barbara

County.

“It’s not an option,” Mr. Brainerd said of returning to that shelter, while

cooking a meal of cheddar cheese melted on a hot dog. “I don’t like people that

much.”

Jennifer Ferraez, a clinical social worker who recommended Sunny Acres to Mr.

Brainerd, said Mr. de Vaul’s way of dealing with the homeless — putting them to

work and largely letting them deal with their demons on their own time — paid

dividends.

“Dan will take them as they are,” Ms. Ferraez said.

Mr. de Vaul, who says he kicked a serious drug and alcohol habit two decades

ago, says Sunny Acres is a clean and sober facility, and says residents are

required to attend meetings of Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous.

But officials are skeptical, and records from the sheriff’s department show

three calls for people “drunk in public” there since 2007, as well as reports of

theft, battery, disturbing the peace, attempted suicide and compliance checks

for parolees and sex offenders. Mr. de Vaul counters by saying that he has

called in many of those problems himself.

Officials also have safety concerns, including nearly a dozen hand-made wooden

sheds — each with four beds — which Mr. de Vaul coated with crankcase oil, a

flammable lubricant. (Mr. de Vaul says it gives the wood “life.”) The sheds have

been condemned.

County and city officials say they have tried to help Mr. de Vaul bring his

operation into code compliance, offering to waive fees, haul off junk and even

bring architects to the site.

“We really felt the county was bending over backward to have Dan be able to

house homeless people,” said Dee Torres, the homeless-services director for the

county’s low-income service agency. “And Dan would not give a centimeter.”

Mr. de Vaul’s appeal is expected to be heard sometime this year. In the

meantime, he says he will continue to take in the down-and-out.

“It’s just like when you start to drill a well,” he said. “The deeper you get

into it, the more you want to see it through.”

A Fight for the Homeless

and Against Authority, NYT, 12.1.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/12/us/12homeless.html

About New York

Where Unsold Clothes Meet People in Need

January 10, 2010

The New York Times

By JIM DWYER

Good ideas have legs. One day in 1985, Suzanne Davis asked a friend, Larry

Phillips, the president of the Phillips-Van Heusen clothing line, if his company

had any excess inventory that could be used by homeless men. A few days later,

Mr. Phillips sent 100 boxes of windbreakers to a shelter on the Bowery.

Then he nudged friends, and 750 London Fog trench coats arrived, followed by

crates of Jockey underwear. “All this merchandise they weren’t going to sell, so

what were they going to do with it?” Ms. Davis recalled.

A few years earlier, City Harvest had been created to rescue edible food that

was going to be destroyed; separately, the Food Bank for New York City was

established to collect and organize food for distribution.

Inspired by these projects, Ms. Davis, then director of the J.M. Kaplan Fund,

organized the New York Clothing Bank to recover unworn garments. It opened in

1986 in a city office on Church Street, and now occupies a 20,000-square-foot

warehouse in the Brooklyn Army Terminal. An executive from J. C. Penney helped

set up the inventory system. Retailers and manufacturers donate goods worth $10

million annually. With a paid staff of three, the bank gives clothing to 250 aid

groups, which help 80,000 people.

Stacked on the warehouse shelves last week were girls’ uniform school blouses

wrapped in plastic, boys’ coats still in bags, boxes of gloves, bundles of

women’s sweaters. The retail sale tags had been stripped.

“Unintentionally, it is one of the city’s best-kept secrets,” said Mary Lanning,

the chairwoman of the Clothing Bank.

Vast quantities of unworn clothing are destroyed every day in the United States.

Last week, I wrote about a City University graduate student, Cynthia Magnus, who

had discovered that a branch of the clothing retailer H & M in Herald Square was

slashing new clothing that it could not sell, then discarding it in the trash. A

cyber-cyclone followed: tens of thousands of people commented on Twitter. H & M

said that it usually donated unsold clothes, and that the 34th Street store was

not following proper procedures. Hundreds of people sent me e-mail. Many said

that they worked at big retailers around the country where useable garments are

routinely destroyed.

The reasons are complex. No business wants to compete with its own garbage, or

risk having people show up at a store seeking refunds on clothes that were never

sold. “That’s why many retailers will damage unsold garments,” said Luis

Jimenez, the director of the Clothing Bank, which is now operated for the city

by Peter Young Housing, Industries and Treatment.

Some businesses do not want their goods worn by poor people. Ed Foy, the founder

of eFashionSolutions.com, said that brands invest billions of dollars in their

images, using models and athletes, which makes them cautious about where donated

leftovers might end up. “They want us to see that the people wearing their

brands are the people we aspire to be,” said Mr. Foy, a board member of the

Clothing Bank. “They want to know, ‘Who’s wearing the clothing and how can that

hurt my brand?’ ”

From the outset, the Clothing Bank tried to address the business concerns, Mr.

Jimenez said. The warehouse is secure, lowering the chances that the donated

clothes would be stolen and resold; only not-for-profit groups receive the

distributions, so that, for example, no individual can collect a pallet full of

Dress Barn merchandise. Donations are tax-deductible. If a donor wants labels

removed, they are cut out by volunteers, including inmates on work release from

the Lincoln Correctional Facility in Harlem. “Hard workers,” Mr. Jimenez said.

The city stopped financing the bank last year, but Mr. Jimenez was able to get

the landlord — also the city — to reduce the rent on the warehouse to $80,000 a

year from $120,000.

Manufacturers and retailers became far more careful with their donations.

Macy’s, which had been making deliveries to the bank three or four times a year,

sent one. “It was 55 boxes,” Mr. Jimenez said, smiling. “The Gap is very nice,

but they’ve been saying ‘we don’t have anything for you now.’ ”

And much depends on personal contacts. The bank had been getting regular

shipments of diapers from Toys R Us, and expected one in September. “When it

didn’t come, we called our contact there, and got no reply,” Mr. Jimenez said.

“Then in November we got a call — the gentleman had passed away suddenly, and

someone had just gotten into his voice mail. That same week, we got eight

pallets of diapers.”

Now retired, Ms. Davis, the founder of the Clothing Bank, said she was heartened

by the graduate student who disclosed the waste at H & M. Good ideas may have

legs. They also need people to run with them.

Where Unsold Clothes

Meet People in Need, NYT, 10.1.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/10/nyregion/10about.html

The Safety Net

Living on Nothing but Food Stamps

January 3, 2010

The New York Times

By JASON DEPARLE and ROBERT M. GEBELOFF

CAPE CORAL, Fla. — After an improbable rise from the Bronx projects to a job

selling Gulf Coast homes, Isabel Bermudez lost it all to an epic housing bust —

the six-figure income, the house with the pool and the investment property.

Now, as she papers the county with résumés and girds herself for rejection, she

is supporting two daughters on an income that inspires a double take: zero

dollars in monthly cash and a few hundred dollars in food stamps.

With food-stamp use at a record high and surging by the day, Ms. Bermudez

belongs to an overlooked subgroup that is growing especially fast: recipients

with no cash income.

About six million Americans receiving food stamps report they have no other

income, according to an analysis of state data collected by The New York Times.

In declarations that states verify and the federal government audits, they

described themselves as unemployed and receiving no cash aid — no welfare, no

unemployment insurance, and no pensions, child support or disability pay.

Their numbers were rising before the recession as tougher welfare laws made it

harder for poor people to get cash aid, but they have soared by about 50 percent

over the past two years. About one in 50 Americans now lives in a household with

a reported income that consists of nothing but a food-stamp card.

“It’s the one thing I can count on every month — I know the children are going

to have food,” Ms. Bermudez, 42, said with the forced good cheer she mastered

selling rows of new stucco homes.

Members of this straitened group range from displaced strivers like Ms. Bermudez

to weathered men who sleep in shelters and barter cigarettes. Some draw on

savings or sporadic under-the-table jobs. Some move in with relatives. Some get

noncash help, like subsidized apartments. While some go without cash incomes

only briefly before securing jobs or aid, others rely on food stamps alone for

many months.

The surge in this precarious way of life has been so swift that few policy

makers have noticed. But it attests to the growing role of food stamps within

the safety net. One in eight Americans now receives food stamps, including one

in four children.

Here in Florida, the number of people with no income beyond food stamps has

doubled in two years and has more than tripled along once-thriving parts of the

southwest coast. The building frenzy that lured Ms. Bermudez to Fort Myers and

neighboring Cape Coral has left a wasteland of foreclosed homes and written new

tales of descent into star-crossed indigence.

A skinny fellow in saggy clothes who spent his childhood in foster care, Rex

Britton, 22, hopped a bus from Syracuse two years ago for a job painting parking

lots. Now, with unemployment at nearly 14 percent and paving work scarce, he

receives $200 a month in food stamps and stays with a girlfriend who survives on

a rent subsidy and a government check to help her care for her disabled toddler.

“Without food stamps we’d probably be starving,” Mr. Britton said.

A strapping man who once made a living throwing fastballs, William Trapani, 53,

left his dreams on the minor league mound and his front teeth in prison, where

he spent nine years for selling cocaine. Now he sleeps at a rescue mission,

repairs bicycles for small change, and counts $200 in food stamps as his only

secure support.

“I’ve been out looking for work every day — there’s absolutely nothing,” he

said.

A grandmother whose voice mail message urges callers to “have a blessed good

day,” Wanda Debnam, 53, once drove 18-wheelers and dreamed of selling real

estate. But she lost her job at Starbucks this year and moved in with her son in

nearby Lehigh Acres. Now she sleeps with her 8-year-old granddaughter under a

poster of the Jonas Brothers and uses her food stamps to avoid her

daughter-in-law’s cooking.

“I’m climbing the walls,” Ms. Debnam said.

Florida officials have done a better job than most in monitoring the rise of

people with no cash income. They say the access to food stamps shows the safety

net is working.

“The program is doing what it was designed to do: help very needy people get

through a very difficult time,” said Don Winstead, deputy secretary for the

Department of Children and Families. “But for this program they would be in even

more dire straits.”

But others say the lack of cash support shows the safety net is torn. The main

cash welfare program, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, has scarcely

expanded during the recession; the rolls are still down about 75 percent from

their 1990s peak. A different program, unemployment insurance, has rapidly

grown, but still omits nearly half the unemployed. Food stamps, easier to get,

have become the safety net of last resort.

“The food-stamp program is being asked to do too much,” said James Weill,

president of the Food Research and Action Center, a Washington advocacy group.

“People need income support.”

Food stamps, officially the called Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program,

have taken on a greater role in the safety net for several reasons. Since the

benefit buys only food, it draws less suspicion of abuse than cash aid and more

political support. And the federal government pays for the whole benefit, giving

states reason to maximize enrollment. States typically share in other programs’

costs.

The Times collected income data on food-stamp recipients in 31 states, which

account for about 60 percent of the national caseload. On average, 18 percent

listed cash income of zero in their most recent monthly filings. Projected over

the entire caseload, that suggests six million people in households with no

income. About 1.2 million are children.

The numbers have nearly tripled in Nevada over the past two years, doubled in

Florida and New York, and grown nearly 90 percent in Minnesota and Utah. In

Wayne County, Mich., which includes Detroit, one of every 25 residents reports

an income of only food stamps. In Yakima County, Wash., the figure is about one

of every 17.

Experts caution that these numbers are estimates. Recipients typically report a

small rise in earnings just once every six months, so some people listed as

jobless may have recently found some work. New York officials say their numbers

include some households with earnings from illegal immigrants, who cannot get

food stamps but sometimes live with relatives who do.

Still, there is little doubt that millions of people are relying on incomes of

food stamps alone, and their numbers are rapidly growing. “This is a reflection

of the hardship that a lot of people in our state are facing; I think that is

without question,” said Mr. Winstead, the Florida official.

With their condition mostly overlooked, there is little data on how long these

households go without cash incomes or what other resources they have. But they

appear an eclectic lot. Florida data shows the population about evenly split

between families with children and households with just adults, with the latter

group growing fastest during the recession. They are racially mixed as well —

about 42 percent white, 32 percent black, and 22 percent Latino — with the

growth fastest among whites during the recession.

The expansion of the food-stamp program, which will spend more than $60 billion

this year, has so far enjoyed bipartisan support. But it does have conservative

critics who worry about the costs and the rise in dependency.

“This is craziness,” said Representative John Linder, a Georgia Republican who

is the ranking minority member of a House panel on welfare policy. “We’re at

risk of creating an entire class of people, a subset of people, just comfortable

getting by living off the government.”

Mr. Linder added: “You don’t improve the economy by paying people to sit around

and not work. You improve the economy by lowering taxes” so small businesses

will create more jobs.

With nearly 15,000 people in Lee County, Fla., reporting no income but food