|

USA > History > 2010 > War > Iraq (II)

Bob Gorrell

National/Syndicated

Cagle

19 August 2010

Obama Says

Iraq Combat Mission Is Over

August 31, 2010

The New York Times

By HELENE COOPER

and SHERYL GAY STOLBERG

WASHINGTON — President Obama declared an end on Tuesday to the seven-year

American combat mission in Iraq, saying that the United States has met its

responsibility to that country and that it is now time to turn to pressing

problems at home.

In a prime-time address from the Oval Office, Mr. Obama balanced praise for the

troops who fought and died in Iraq with his conviction that getting into the

conflict had been a mistake in the first place. But he also used the moment to

emphasize that he sees his primary job as addressing the weak economy and other

domestic issues — and to make clear that he intends to begin disengaging from

the war in Afghanistan next summer.

“We have sent our young men and women to make enormous sacrifices in Iraq, and

spent vast resources abroad at a time of tight budgets at home,” Mr. Obama said.

“Through this remarkable chapter in the history of the United States and Iraq,

we have met our responsibility. Now, it’s time to turn the page.”

Seeking to temper partisan feelings over the war on a day when Republicans

pointed out that Mr. Obama had opposed the troop surge generally credited with

helping to bring Iraq a measure of stability, the president offered some praise

for his predecessor, George W. Bush. Mr. Obama acknowledged their disagreement

over Iraq but said that no one could doubt Mr. Bush’s “support for our troops,

or his love of country and commitment to our security.”

Mr. Obama spoke for about 18 minutes, saying that violence would continue in

Iraq and that the United States would continue to play a key role in nurturing a

stable democracy there. He celebrated America’s fighting forces as “the steel in

our ship of state,” and pledged not to waver in the fight against Al Qaeda.

But he suggested that he sees his role in addressing domestic issues as

dominant, saying that it would be difficult to get the economy rolling again but

that doing so was “our central mission as a people, and my central

responsibility as president.”

With his party facing the prospect of losing control of Congress in this fall’s

elections and his own poll numbers depressed in large part because of the

lackluster economy and still-high unemployment, he said the nation’s

perseverance in Iraq must be matched by determination to address problems at

home.

Over the last decade, “we have spent over a trillion dollars at war, often

financed by borrowing from overseas,” he said. “And so at this moment, as we

wind down the war in Iraq, we must tackle those challenges at home with as much

energy and grit and sense of common purpose as our men and women in uniform who

have served abroad.”

Mr. Obama acknowledged a war fatigue among Americans who have called into

question his focus on the Afghanistan war, now approaching its 10th year. He

said that American forces in Afghanistan “will be in place for a limited time”

to give Afghans the chance to build their government and armed forces.

“But, as was the case in Iraq, we cannot do for Afghans what they must

ultimately do for themselves,” the president said. He reiterated that next July

he would begin transferring responsibility for security to Afghans, at a pace to

be determined by conditions.

“But make no mistake: this transition will begin, because open-ended war serves

neither our interests nor the Afghan people’s,” he said.

This was no iconic end-of-war moment with photos of soldiers kissing nurses in

Times Square or victory parades down America’s Main Streets.

Instead, in the days leading to the Tuesday night deadline for the withdrawal of

American combat troops, it has appeared as if administration officials and the

American military were the only ones marking the end of this country’s combat

foray into Iraq. Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr., Defense Secretary Robert M.

Gates and Adm. Mike Mullen, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, are all

in Baghdad for the official ceremony on Wednesday.

The very sight of Mr. Obama addressing Americans from the Oval Office — from the

same desk where Mr. Bush announced the beginning of the conflict — shows the

distance traveled since the Iraq war began. On the night of March 20, 2003, when

the Army’s Third Infantry Division first rolled over the border from Kuwait into

Iraq, Mr. Obama was a state senator in Illinois.

Mr. Bush was at the height of his popularity, and the perception at home and in

many places abroad was that America could achieve its national security goals

primarily through military power. One of the biggest fears among the American

troops in the convoy pouring into Iraq that night — every one of them suited in

gas masks and wearing biohazard suits — was that the man they came to topple

might unleash a chemical weapons attack.

Seven years and five months later, the biggest fears of American soldiers

revolve around the primitive, basic, homemade bombs and old explosives in

Afghanistan that were left over from the Soviet invasion. In Iraq, what was

perceived as a threat from a powerful dictator, Saddam Hussein, has dissolved

into the worry that as United States troops pull out they are leaving behind an

unstable and weak government that could be influenced by Iran.

On Tuesday, a senior intelligence official said that Iran continues to supply

militant groups in Iraq with weapons, training and equipment.

“Much has changed since that night,” when Mr. Bush announced the war in Iraq,

Mr. Obama said. “A war to disarm a state became a fight against an insurgency.

Terrorism and sectarian warfare threatened to tear Iraq apart. Thousands of

Americans gave their lives; tens of thousands have been wounded. Our relations

abroad were strained. Our unity at home was tested.”

The withdrawal of combat forces represents a significant milestone after the war

that toppled Mr. Hussein, touched off waves of sectarian strife and claimed the

lives of more than 4,400 American soldiers and more than 70,000 Iraqis,

according to United States and Iraqi government figures.

“Operation Iraqi Freedom is over,” Mr. Obama said, using the military name for

the mission, “and the Iraqi people now have lead responsibility for the security

of their country.”

As Mr. Obama prepared to observe the end of one phase of the war, he called Mr.

Bush from Air Force One, as he was en route to Fort Bliss in Texas to meet with

American troops home from Iraq.

The two spoke “just for a few moments,” Ben Rhodes, deputy national security

adviser for strategic communications, told reporters aboard the plane, declining

to give any additional details.

American troops reached Mr. Obama’s goal for the drawdown early — last week Gen.

Ray Odierno, the American commander in Iraq, said that the number of troops had

dropped to 49,700, roughly the number that would stay through next summer.

That is less than a third of the number of troops in Iraq during the surge in

2007. Under an agreement between Iraq and the United States, the remaining

troops are to leave by the end of 2011, though some Iraqi and American officials

say they think that the agreement may be renegotiated to allow for a longer

American military presence.

The remaining “advise and assist” brigades will officially concentrate on

supporting and training Iraqi security forces, protecting American personnel and

facilities, and mounting counterterrorism operations.

Still, as Mr. Obama himself acknowledged Tuesday, the milestone came with all of

the ambiguity and messiness that accompanied the war itself.

A political impasse, in place since March elections, has left Iraq without a

permanent government just as the government in Baghdad was supposed to be

asserting more control.

Republican critics of the president were quick to point out Tuesday that Mr.

Obama opposed the troop surge that they credit for decreased violence in Iraq.

“Some leaders who opposed, criticized, and fought tooth-and-nail to stop the

surge strategy now proudly claim credit for the results,” Representative John A.

Boehner of Ohio, the House Republican leader, told veterans at the national

convention of the American Legion in Milwaukee.

Carl Hulse and Mark Mazzetti contributed reporting.

Obama Says Iraq Combat

Mission Is Over, NYT, 31.8.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/01/world/01military.html

President Obama’s Address on Iraq

August 31, 2010

The New York Times

The following is the text, as prepared for delivery, of President Obama’s

address from the Oval Office on Tuesday night, provided by the White House:

Good evening. Tonight, I’d like to talk to you about the end of our combat

mission in Iraq, the ongoing security challenges we face, and the need to

rebuild our nation here at home.

I know this historic moment comes at a time of great uncertainty for many

Americans. We have now been through nearly a decade of war. We have endured a

long and painful recession. And sometimes in the midst of these storms, the

future that we are trying to build for our nation — a future of lasting peace

and long-term prosperity may seem beyond our reach.

But this milestone should serve as a reminder to all Americans that the future

is ours to shape if we move forward with confidence and commitment. It should

also serve as a message to the world that the United States of America intends

to sustain and strengthen our leadership in this young century.

From this desk, seven and a half years ago, President Bush announced the

beginning of military operations in Iraq. Much has changed since that night. A

war to disarm a state became a fight against an insurgency. Terrorism and

sectarian warfare threatened to tear Iraq apart. Thousands of Americans gave

their lives; tens of thousands have been wounded. Our relations abroad were

strained. Our unity at home was tested.

These are the rough waters encountered during the course of one of America’s

longest wars. Yet there has been one constant amidst those shifting tides. At

every turn, America’s men and women in uniform have served with courage and

resolve. As commander in chief, I am proud of their service. Like all Americans,

I am awed by their sacrifice, and by the sacrifices of their families.

The Americans who have served in Iraq completed every mission they were given.

They defeated a regime that had terrorized its people. Together with Iraqis and

coalition partners who made huge sacrifices of their own, our troops fought

block by block to help Iraq seize the chance for a better future. They shifted

tactics to protect the Iraqi people; trained Iraqi security forces; and took out

terrorist leaders. Because of our troops and civilians — and because of the

resilience of the Iraqi people — Iraq has the opportunity to embrace a new

destiny, even though many challenges remain.

So tonight, I am announcing that the American combat mission in Iraq has ended.

Operation Iraqi Freedom is over, and the Iraqi people now have lead

responsibility for the security of their country.

This was my pledge to the American people as a candidate for this office. Last

February, I announced a plan that would bring our combat brigades out of Iraq,

while redoubling our efforts to strengthen Iraq’s security forces and support

its government and people. That is what we have done. We have removed nearly

100,000 U.S. troops from Iraq. We have closed or transferred hundreds of bases

to the Iraqis. And we have moved millions of pieces of equipment out of Iraq.

This completes a transition to Iraqi responsibility for their own security. U.S.

troops pulled out of Iraq’s cities last summer, and Iraqi forces have moved into

the lead with considerable skill and commitment to their fellow citizens. Even

as Iraq continues to suffer terrorist attacks, security incidents have been near

the lowest on record since the war began. And Iraqi forces have taken the fight

to Al Qaeda, removing much of its leadership in Iraqi-led operations.

This year also saw Iraq hold credible elections that drew a strong turnout. A

caretaker administration is in place as Iraqis form a government based on the

results of that election. Tonight, I encourage Iraq’s leaders to move forward

with a sense of urgency to form an inclusive government that is just,

representative, and accountable to the Iraqi people. And when that government is

in place, there should be no doubt: the Iraqi people will have a strong partner

in the United States. Our combat mission is ending, but our commitment to Iraq’s

future is not.

Going forward, a transitional force of U.S. troops will remain in Iraq with a

different mission: advising and assisting Iraq’s security forces; supporting

Iraqi troops in targeted counterterrorism missions; and protecting our

civilians. Consistent with our agreement with the Iraqi government, all U.S.

troops will leave by the end of next year. As our military draws down, our

dedicated civilians — diplomats, aid workers, and advisers — are moving into the

lead to support Iraq as it strengthens its government, resolves political

disputes, resettles those displaced by war, and builds ties with the region and

the world. And that is a message that Vice President Biden is delivering to the

Iraqi people through his visit there today.

This new approach reflects our long-term partnership with Iraq — one based upon

mutual interests, and mutual respect. Of course, violence will not end with our

combat mission. Extremists will continue to set off bombs, attack Iraqi

civilians and try to spark sectarian strife. But ultimately, these terrorists

will fail to achieve their goals. Iraqis are a proud people. They have rejected

sectarian war, and they have no interest in endless destruction. They understand

that, in the end, only Iraqis can resolve their differences and police their

streets. Only Iraqis can build a democracy within their borders. What America

can do, and will do, is provide support for the Iraqi people as both a friend

and a partner.

Ending this war is not only in Iraq’s interest — it is in our own. The United

States has paid a huge price to put the future of Iraq in the hands of its

people. We have sent our young men and women to make enormous sacrifices in

Iraq, and spent vast resources abroad at a time of tight budgets at home. We

have persevered because of a belief we share with the Iraqi people — a belief

that out of the ashes of war, a new beginning could be born in this cradle of

civilization. Through this remarkable chapter in the history of the United

States and Iraq, we have met our responsibility. Now, it is time to turn the

page.

As we do, I am mindful that the Iraq war has been a contentious issue at home.

Here, too, it is time to turn the page. This afternoon, I spoke to former

President George W. Bush. It’s well known that he and I disagreed about the war

from its outset. Yet no one could doubt President Bush’s support for our troops,

or his love of country and commitment to our security. As I have said, there

were patriots who supported this war, and patriots who opposed it. And all of us

are united in appreciation for our servicemen and women, and our hope for Iraq’s

future.

The greatness of our democracy is grounded in our ability to move beyond our

differences, and to learn from our experience as we confront the many challenges

ahead. And no challenge is more essential to our security than our fight against

Al Qaeda.

Americans across the political spectrum supported the use of force against those

who attacked us on 9/11. Now, as we approach our 10th year of combat in

Afghanistan, there are those who are understandably asking tough questions about

our mission there. But we must never lose sight of what’s at stake. As we speak,

Al Qaeda continues to plot against us, and its leadership remains anchored in

the border region of Afghanistan and Pakistan. We will disrupt, dismantle, and

defeat Al Qaeda, while preventing Afghanistan from again serving as a base for

terrorists. And because of our drawdown in Iraq, we are now able to apply the

resources necessary to go on offense. In fact, over the last 19 months, nearly a

dozen Al Qaeda leaders — and hundreds of Al Qaeda’s extremist allies — have been

killed or captured around the world.

Within Afghanistan, I have ordered the deployment of additional troops who —

under the command of General David Petraeus — are fighting to break the

Taliban’s momentum. As with the surge in Iraq, these forces will be in place for

a limited time to provide space for the Afghans to build their capacity and

secure their own future. But, as was the case in Iraq, we cannot do for Afghans

what they must ultimately do for themselves. That’s why we are training Afghan

security forces and supporting a political resolution to Afghanistan’s problems.

And, next July, we will begin a transition to Afghan responsibility. The pace of

our troop reductions will be determined by conditions on the ground, and our

support for Afghanistan will endure. But make no mistake: this transition will

begin — because open-ended war serves neither our interests nor the Afghan

people’s.

Indeed, one of the lessons of our effort in Iraq is that American influence

around the world is not a function of military force alone. We must use all

elements of our power — including our diplomacy, our economic strength, and the

power of America’s example — to secure our interests and stand by our allies.

And we must project a vision of the future that is based not just on our fears,

but also on our hopes — a vision that recognizes the real dangers that exist

around the world, but also the limitless possibility of our time.

Today, old adversaries are at peace, and emerging democracies are potential

partners. New markets for our goods stretch from Asia to the Americas. A new

push for peace in the Middle East will begin here tomorrow. Billions of young

people want to move beyond the shackles of poverty and conflict. As the leader

of the free world, America will do more than just defeat on the battlefield

those who offer hatred and destruction — we will also lead among those who are

willing to work together to expand freedom and opportunity for all people.

That effort must begin within our own borders. Throughout our history, America

has been willing to bear the burden of promoting liberty and human dignity

overseas, understanding its link to our own liberty and security. But we have

also understood that our nation’s strength and influence abroad must be firmly

anchored in our prosperity at home. And the bedrock of that prosperity must be a

growing middle class.

Unfortunately, over the last decade, we have not done what is necessary to shore

up the foundation of our own prosperity. We have spent over a trillion dollars

at war, often financed by borrowing from overseas. This, in turn, has

shortchanged investments in our own people, and contributed to record deficits.

For too long, we have put off tough decisions on everything from our

manufacturing base to our energy policy to education reform. As a result, too

many middle class families find themselves working harder for less, while our

nation’s long-term competitiveness is put at risk.

And so at this moment, as we wind down the war in Iraq, we must tackle those

challenges at home with as much energy, and grit, and sense of common purpose as

our men and women in uniform who have served abroad. They have met every test

that they faced. Now, it is our turn. Now, it is our responsibility to honor

them by coming together, all of us, and working to secure the dream that so many

generations have fought for — the dream that a better life awaits anyone who is

willing to work for it and reach for it.

Our most urgent task is to restore our economy, and put the millions of

Americans who have lost their jobs back to work. To strengthen our middle class,

we must give all our children the education they deserve, and all our workers

the skills that they need to compete in a global economy. We must jump-start

industries that create jobs, and end our dependence on foreign oil. We must

unleash the innovation that allows new products to roll off our assembly lines,

and nurture the ideas that spring from our entrepreneurs. This will be

difficult. But in the days to come, it must be our central mission as a people,

and my central responsibility as president.

Part of that responsibility is making sure that we honor our commitments to

those who have served our country with such valor. As long as I am president, we

will maintain the finest fighting force that the world has ever known, and do

whatever it takes to serve our veterans as well as they have served us. This is

a sacred trust. That is why we have already made one of the largest increases in

funding for veterans in decades. We are treating the signature wounds of today’s

wars post-traumatic stress and traumatic brain injury, while providing the

health care and benefits that all of our veterans have earned. And we are

funding a post-9/11 G.I. bill that helps our veterans and their families pursue

the dream of a college education. Just as the G.I. Bill helped those who fought

World War II — including my grandfather — become the backbone of our middle

class, so today’s servicemen and women must have the chance to apply their gifts

to expand the American economy. Because part of ending a war responsibly is

standing by those who have fought it.

Two weeks ago, America’s final combat brigade in Iraq — the Army’s Fourth

Stryker Brigade — journeyed home in the predawn darkness. Thousands of soldiers

and hundreds of vehicles made the trip from Baghdad, the last of them passing

into Kuwait in the early morning hours. Over seven years before, American troops

and coalition partners had fought their way across similar highways, but this

time no shots were fired. It was just a convoy of brave Americans, making their

way home.

Of course, the soldiers left much behind. Some were teenagers when the war

began. Many have served multiple tours of duty, far from their families who bore

a heroic burden of their own, enduring the absence of a husband’s embrace or a

mother’s kiss. Most painfully, since the war began 55 members of the Fourth

Stryker Brigade made the ultimate sacrifice — part of over 4,400 Americans who

have given their lives in Iraq. As one staff sergeant said, “I know that to my

brothers in arms who fought and died, this day would probably mean a lot.”

Those Americans gave their lives for the values that have lived in the hearts of

our people for over two centuries. Along with nearly 1.5 million Americans who

have served in Iraq, they fought in a faraway place for people they never knew.

They stared into the darkest of human creations — war — and helped the Iraqi

people seek the light of peace.

In an age without surrender ceremonies, we must earn victory through the success

of our partners and the strength of our own nation. Every American who serves

joins an unbroken line of heroes that stretches from Lexington to Gettysburg;

from Iwo Jima to Inchon; from Khe Sanh to Kandahar — Americans who have fought

to see that the lives of our children are better than our own. Our troops are

the steel in our ship of state. And though our nation may be travelling through

rough waters, they give us confidence that our course is true, and that beyond

the predawn darkness, better days lie ahead.

Thank you. May God bless you. And may God bless the United States of America,

and all who serve her.

President Obama’s

Address on Iraq, NYT, 31.8.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/01/world/01obama-text.html

The War in Iraq

August 31, 2010

The New York Times

We were glad to see President Obama go to Fort Bliss on Tuesday before his

Oval Office speech on Iraq, to thank those Americans who most shouldered the

burdens of a tragic, pointless war. One of the few rays of light in the conflict

has been the distance America has come since Vietnam, when blameless soldiers

were scorned for decisions made by politicians.

President George W. Bush tried to make Iraq an invisible, seemingly cost-free

war. He refused to attend soldiers’ funerals and hid their returning coffins

from the public. So it was fitting that Mr. Obama, who has improved veterans’

health care and made the Pentagon budget more rational, paid tribute to them.

“At every turn, America’s men and women in uniform have served with courage and

resolve,” he said on Tuesday night. He added: “There were patriots who supported

this war, and patriots who opposed it. And all of us are united in appreciation

for our servicemen and women, and our hope for Iraq’s future.”

The speech also made us reflect on how little Mr. Bush accomplished by

needlessly invading Iraq in March 2003 — and then ludicrously declaring victory

two months later.

Saddam Hussein’s weapons of mass destruction proved to be Bush administration

propaganda. The war has not created a new era of democracy in the Middle East —

or in Iraq for that matter. There are stirrings of democratic politics in Iraq

that give us hope. But there is no government six months after national

elections.

In many ways, the war made Americans less safe, creating a new organization of

terrorists and diverting the nation’s military resources and political will from

Afghanistan. Deprived of its main adversary, a strong Iraq, Iran was left freer

to pursue its nuclear program, to direct and finance extremist groups and to

meddle in Iraq.

Mr. Obama graciously said it was time to put disagreements over Iraq behind us,

but it is important not to forget how much damage Mr. Bush caused by misleading

Americans about exotic weapons, about American troops being greeted with open

arms, about creating a model democracy in Baghdad.

That is why it was so important that Mr. Obama candidly said the United States

is not free of this conflict; American troops will see more bloodshed. We hope

he follows through on his vow to work with Iraq’s government after the

withdrawal of combat troops.

There was no victory to declare last night, and Mr. Obama was right not to try.

If victory was ever possible in this war, it has not been won, and America still

faces the daunting challenges of the other war, in Afghanistan.

Mr. Obama, addressing those who either believe that he is not committed to the

fight in Afghanistan or believe that he will not leave, said Americans should

“make no mistake” — he will stick to his plan to begin withdrawing troops next

August. He still needs to clearly explain, and soon, how he will “disrupt,

dismantle and defeat Al Qaeda” and meet that timetable.

As we heard Mr. Obama speak from his desk with his usual calm clarity and

eloquence, it made us wish we heard more from him on many issues. We are puzzled

about why he talks to Americans directly so rarely and with seeming reluctance.

This was only his second Oval Office address in more than 19 months of crisis

upon crisis. The country particularly needs to hear more from Mr. Obama about

what he rightly called the most urgent task — “to restore our economy and put

the millions of Americans who have lost their jobs back to work.”

For this day, it was worth dwelling on this milestone in Iraq and on some grim

numbers: more than 4,400 Americans dead and some 35,000 wounded, many with lost

limbs. And on one number that American politicians are loath to mention: at

least 100,000 Iraqis dead.

The War in Iraq, NYT,

31.8.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/01/opinion/01wed1.html

After Years of War,

Few Iraqis Have a Clear View of the Future

August 31, 2010

The New York Times

By ANTHONY SHADID

BAGHDAD — The invasion of Iraq, occupation and tumult that followed were

called Operation Iraqi Freedom back then. It will be named New Dawn on

Wednesday.

But America’s attempt to bring closure to an unpopular war has collided with a

disconnect familiar since 2003: the charts and trend lines offered by American

officials never seem to capture the intangible that has so often shaped the

pivots in the war in Iraq.

Call it the mood. And the country, seemingly forever unsettled and unhappy, is

having a slew of bad days.

“Nothing’s changed, nothing!” Yusuf Sabah shouted in the voice of someone rarely

listened to, as he waited for gas in a line of cars winding down a dirt road

past a barricade of barbed wire, shards of concrete and trash turned uniformly

brown. “From the fall of Saddam until now, nothing’s changed. The opposite. We

keep going backwards.”

Down the road waited Haitham Ahmed, a taxi driver. “Frustrated, sick, worn out,

pessimistic and angry,” he said, describing himself.

“What else should I add?”

The Iraq that American officials portray today — safer, more peaceful, with more

of the trappings of a state — relies on 2006 as a baseline, when the country was

on the verge of a nihilistic descent into carnage. For many here, though, the

starting point is the statement President George W. Bush made on March 10, 2003,

10 days before the invasion, when he promised that “the life of the Iraqi

citizen is going to dramatically improve.”

Iraq generates more electricity than it did then, but far greater demand has

left many sweltering in the heat. Water is often filthy. Iraqi security forces

are omnipresent, but drivers habitually deride them for their raggedy appearance

and seeming unprofessionalism. That police checkpoints snarl traffic does not

help.

What American officials portray as their greatest accomplishment — a nascent

democracy, however flawed — often generates a rueful response. “People can’t

live only on the air they breathe,” said Qassem Sebti, an artist.

In a conflict often defined by unintended consequences, the March election may

prove a turning point in an unexpected way. To an unprecedented degree, people

took part, regardless of sect and ethnicity.

But nearly six months later, politicians are still deadlocked over forming a

government, and the glares at the sport-utility vehicles that ferry them and

their gun-toting entourages from air-conditioned offices to air-conditioned

homes, after meetings unfailingly described as “positive,” have become sharper.

Disenchantment runs rife not with one faction or another, but with an entire

political class that the United States helped empower with its invasion.

“The people of Kadhimiya mourn for the government in the death of water and

electricity,” a tongue-and-cheek banner read near a Shiite shrine in Baghdad.

The year 2003, when the Americans invaded, often echoes in 2010, as they prepare

to leave. Little feels linear here these days; the sense of the recurrent is

more familiar.

Lines at fuel stations returned this month, that testament to one the greatest

of Iraq’s ironies: a country with the world’s third largest reserve of oil in

which people must endure long waits for gas.

“Ghamidh” was the word heard often in those earliest years. It means obscure and

ambiguous, and then, as now, it was typically the answer to any question.

“After seven years our destiny is still unknown,” Mr. Sabah said, waiting in a

gas line. “When you look to the future, you have no idea what it holds.”

Complaints over shoddy services paraphrase the same grievances of those anarchic

months after Saddam Hussein’s fall. The sense of the unknown persists, as

frustration mounts, Iraqi leaders bicker and no one seems sure of American

intentions, even as President Obama observes what the administration describes

as a turning point in the conflict.

“I challenge anyone to say what has happened, what’s happening now and what will

happen in the future,” Mohammed Hayawi, a bookseller whose girth matched his

charm, said as sweat poured down his jowly face on a hot summer day in 2003.

Mr. Hayawi died in 2007, as a car bomb tore through his bookstore filled with

tomes of ayatollahs, predictions by astrologers and poems of Communist

intellectuals. This week, in the same shop, still owned by his family, Najah

Hayawi reflected on his words, near a poster that denounced “the cowardly,

wretched bombing” that had killed his brother.

“There is no one in Iraq who has any idea — not only about what’s happened or

what’s happening — but about what will happen in the future,” he said. “Not just

me, not just Mohammed, God rest his soul, but anyone you talk to. You won’t find

anyone.”

Iraqis call the overthrow of Mr. Hussein’s government the “suqut.” It means the

fall. Seven years later, no one has yet quite defined what replaced it, an

interim as inconclusive as the invasion was climactic. “Theater,” Mr. Hayawi’s

brother called it, and he said the populace still had no hand in writing a

script that was in others’ hands.

“The best thing is that I have no children,” Shahla Atraqji, a 38-year-old

doctor, said back in 2003, as she sipped coffee at Baghdad’s Hunting Club to the

strains of Lebanese pop. “If I can’t offer my children a good life, I would

never bring them into this world.”

This week, Thamer Aziz, a doctor who helps fit amputees with artificial limbs at

the Medical Rehabilitation Center, stared at Musafa Hashem, a 6-year-old boy who

lost his right leg in a car bomb in Kadhimiya in July. His father was paralyzed.

“I’ve believed this for a long time, and I still do,” he said. “I cannot get

married and have a family because I may lose them any minute, by a bomb or

bullet.”

“Just like him,” he said, gesturing toward the boy.

Even in the denouement of America’s experience here, old habits die hard.

On Monday, four American Humvees drove the wrong way down a street, turrets

swinging at oncoming traffic. Cars stopped, giving them distance. The Humvees

turned, plowed over a curb, dug a trench in the muddy median, then rumbled on

their way.

“See! Did you see?” asked Mustafa Munaf, a storekeeper.

“It’s the same thing,” he said, shaking his head. “What’s changed?”

After Years of War, Few

Iraqis Have a Clear View of the Future, NYT, 31.8.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/01/world/middleeast/01iraq.html

Leader Says Iraq Independent as U.S. Ends Combat

August 31, 2010

Filed at 7:55 a.m. ET

The New York Times

By REUTERS

BAGHDAD (Reuters) - Iraq's prime minister said the end of U.S. combat

operations on Tuesday restored Iraq's sovereignty and meant it stood as an equal

to the United States, despite political deadlock and persistent violence.

U.S. troop levels were cut to 50,000 before the partly symbolic deadline of

August 31 pledged by President Barack Obama to fulfill his pledge to end the war

launched by his predecessor George W. Bush.

The six remaining U.S. brigades will turn their focus to training Iraqi police

and troops as Iraq takes charge of its own destiny ahead of a full U.S.

withdrawal by the end of next year.

"Iraq today is sovereign and independent," Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki told

Iraqis in a televised address to mark the U.S. forces' shift to assisting rather

than leading the fight against a Sunni Islamist insurgency and Shi'ite militia.

"With the execution of the troop pullout, our relations with the United States

have entered a new stage between two equal, sovereign countries."

Obama promised war-weary U.S. voters he would extricate the United States from

the war, launched by Bush with the stated aim of destroying Iraqi weapons of

mass destruction.

No such weapons were found. Almost a trillion dollars have been spent and more

than 4,400 U.S. soldiers and over 100,000 Iraqi civilians killed since the 2003

invasion.

Obama's Democrats are battling to retain control of Congress in November

elections and he faces other challenges -- a worsening war in Afghanistan and

storm clouds over the economy.

Tuesday's deadline was to some extent a symbolic one. The 50,000 U.S. soldiers

staying on in Iraq for another 16 months are a formidable and heavily-armed

force.

Iraqi security forces have already been taking the lead since a bilateral

security pact came into force in 2009. U.S. soldiers pulled out of Iraqi towns

and cities in June last year.

"WE'LL BE FINE, THEY'LL BE FINE"

Nevertheless, Iraqis are apprehensive as U.S. military might is scaled down,

especially amid a political impasse six months after an inconclusive election.

"We'll be just fine, they'll be just fine," U.S. Vice President Joe Biden said

after flying into Baghdad on Monday to mark the end of combat operations and to

urge Iraqi leaders to speed up the formation of a new government.

"Notwithstanding what the national press says about increased violence, the

truth is things are very much different. Things are much safer," Biden told

Maliki on Tuesday before their meeting was closed to the media.

Toppled dictator Saddam Hussein's outlawed Baath party crowed that the U.S.

pullback was a result of "devastating" strikes against U.S. troops by Iraqi

resistance fighters.

"They withdrew dragging tails of failure and defeat, leaving by the same roads

they used as invaders," it said in a statement carried by Iraqi websites. "The

end of the U.S. combat mission in Iraq is a useless attempt to save face, if any

is left."

U.S. officials said Washington had a long-term commitment to Iraq, and the

military pullback would allow diplomats to take the lead in building economic,

cultural and educational ties. For that they need a new Iraqi government to be

in place.

Violence has declined sharply since the peak in 2006/07 of the sectarian

slaughter unleashed by the invasion, but a recent series of attacks has rung

alarm bells.

The animosity that led to carnage between majority Shi'ites and once dominant

Sunnis has not healed, and a potentially explosive dispute between Arabs and

Kurds has not been resolved.

More than 1.5 million Iraqis are still displaced after being driven from their

homes by violence. Many live in squalor.

Many Iraqis had hoped the March 7 election would chart a path toward stability

at a time when deals to develop the country's vast oilfields hold the promise of

prosperity.

Instead, the ballot could widen ethnic and sectarian rifts if the actual vote

leader, ex-premier Iyad Allawi's Sunni-backed cross-sectarian Iraqiya alliance,

is excluded from power by the major Shi'ite-led political factions.

"I promise you the sectarian war will not return. We will not allow it. Iraqis

will live as loving brothers," Maliki said.

Suspected Sunni Islamist insurgents linked to al Qaeda have tried to exploit the

political vacuum and declining U.S. troop numbers with suicide bombings and

assassinations.

They have targeted security forces in particular. A suicide bomber killed 57

army recruits and soldiers on August 17 and more than 60 died on August 25 in

attacks on police stations.

Iraqis also fear that Shi'ite Iran will seek to fill any vacuum left by the U.S.

military, in competition with Sunni-led neighbors such as Turkey and Saudi

Arabia.

(Additional reporting by Ahmed Rasheed, Khalid al-Ansary, Muhanad Mohammed

and Aseel Kami; writing by Michael Christie; editing by Andrew Roche)

Leader Says Iraq

Independent as U.S. Ends Combat, NYT, 31.8.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/reuters/2010/08/31/world/middleeast/international-us-iraq.html

Marking Iraq Milestone, Gates Strikes Cautious Note

August 31, 2010

The Newx York Times

By ELISABETH BUMILLER

MILWAUKEE — Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates warned on Tuesday against

“premature victory parades or self-congratulations” as American combat

operations in Iraq drew officially to a close, and at the same time said that

the success of United States forces in Afghanistan was only “possible,” not

inevitable.

In remarks to the American Legion that foreshadowed an address by President

Obama on Tuesday night to mark the Aug. 31 date for the withdrawal of all United

States combat troops from Iraq, Mr. Gates sounded a restrained, sober note about

the state of America’s two wars.

In Iraq, he said, the most recent elections have yet to result in a coalition

government, Al Qaeda in Mesopotamia is beaten but not gone, and sectarian

tensions remain. He said the 50,000 United States troops still in Iraq would

continue to work with Iraqi security forces, who only last week faced a flurry

of coordinated insurgent attacks across the country that killed at least 51

people.

“I am not saying that all is, or necessarily will be, well in Iraq,” Mr. Gates,

who is one of Mr. Obama’s most influential advisers, told the legion.

In Afghanistan, he said, the Taliban are “a cruel and ruthless adversary, and

are not going quietly.” Their leadership, he said, has ordered a campaign of

intimidation against Afghan civilians and is singling out women for brutal

attacks.

“I know there is a good deal of concern and impatience about the pace of

progress since the new strategy was announced last December,” Mr. Gates said,

referring to Mr. Obama’s decision to send to Afghanistan 30,000 additional

United States troops, who have finished arriving only this month. Total American

forces in Afghanistan now number nearly 100,000.

But in an attempt to draw a parallel between the current fragile stability of

Iraq and what might be possible in Afghanistan, Mr. Gates said that the

intensifying combat and rising casualties in Afghanistan were in many ways

reminiscent of the early months of the surge of United States forces ordered in

Iraq by President George W. Bush in 2007, when American troops were taking the

highest losses of the war.

“Three and a half years ago very few believed the surge could take us to where

we are today in Iraq, and there were plenty of reasons for doubts,” said Mr.

Gates, who helped make the surge decision as Mr. Bush’s defense secretary at the

time. But “back then, this country’s civilian and military leadership chose the

path we believed had the best chance of achieving our national security

objectives, as we are doing in Afghanistan today.”

He added: “Success there is not inevitable. But with the right strategy and the

willingness to see it through, it is possible. And it is certainly worth the

fight.”

Despite his cautious tone on Iraq, Mr. Gates cited what he called dramatic

security gains. He said that violence levels this year remained at their lowest

level since the beginning of the war in 2003, that American forces have not had

to conduct an airstrike in six months and that Al Qaeda in Mesopotamia had been

largely cut off “from its masters abroad.”

But he said the gains had been purchased “at a terrible cost”: 4,427 American

service members killed, 34,268 Americans wounded or injured and untold losses

and trauma endured by the Iraqis themselves.

Mr. Gates’s voice seemed to choke as he then said: “The courage of these men and

women, their determination, their sacrifice — and that of their families — along

with the service and sacrifice of so many others in uniform, have made this day,

this transition, possible. And we must never forget.”

In Afghanistan, Mr. Gates promised that the United States would take a hard line

against corruption in the Afghan government. He also echoed Mr. Obama and senior

military commanders by saying that the president’s deadline for the start of

withdrawals of United States forces from Afghanistan next July would be a

gradual beginning, not a massive departure.

“If the Taliban really believe that America is heading for the exits next summer

in large numbers, they’ll be deeply disappointed and surprised to find us very

much in the fight,” he said.

Marking Iraq Milestone, Gates Strikes Cautious

Note, NYT, 31.8.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/01/world/01military.html

We Owe the Troops an Exit

August 30, 2010

The New York Times

By BOB HERBERT

At least 14 American soldiers have been killed in Afghanistan over the past

few days.

We learned on Saturday that our so-called partner in this forlorn war, Hamid

Karzai, fired a top prosecutor who had insisted on, gasp, fighting the

corruption that runs like a crippling disease through his country.

Time magazine tells us that stressed-out, depressed and despondent soldiers are

seeking help for their mental difficulties at a rate that is overwhelming the

capacity of available professionals. What we are doing to these troops who have

been serving tour after tour in Afghanistan and Iraq is unconscionable.

Time described the mental-health issue as “the U.S. Army’s third front,” with

the reporter, Mark Thompson, writing: “While its combat troops fight two wars,

its mental-health professionals are waging a battle to save soldiers’ sanity

when they come back, one that will cost billions long after combat ends in

Baghdad and Kabul.”

In addition to the terrible physical toll, the ultimate economic costs of these

two wars, as the Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz and his colleague Linda Bilmes

have pointed out, will run to more than $3 trillion.

I get a headache when I hear supporters of this endless warfare complaining

about the federal budget deficits. They’re like arsonists complaining about the

smell of smoke in the neighborhood.

There is no silver lining to this nearly decade-old war in Afghanistan. Poll

after poll has shown that it no longer has the support of most Americans. And

yet we fight on, feeding troops into the meat-grinder year after tragic year —

to what end?

“Clearly, the final chapters of this particular endeavor are very much yet to be

written,” said Gen. David Petraeus, the commander of American and NATO forces in

Afghanistan, during a BBC interview over the weekend. He sounded as if those

chapters would not be written any time soon.

In a reference to President Obama’s assertion that U.S. troops would begin to

withdraw from Afghanistan next July, General Petraeus told the interviewer:

“That’s a date when a process begins, nothing more, nothing less. It’s not the

date when the American forces begin an exodus and look for the exit and the

light to turn off on the way out of the room.”

A lot of Americans who had listened to the president thought it was, in fact, a

date when the American forces would begin an exodus. The general seems to have

heard something quite different.

In truth, it’s not at all clear how President Obama really feels about the

awesome responsibilities involved in waging war, and that’s a problem. The

Times’s Peter Baker wrote a compelling and in many ways troubling article

recently about the steep learning curve that Mr. Obama, with no previous

military background, has had to negotiate as a wartime commander in chief.

Quoting an unnamed adviser to the president, Mr. Baker wrote that Mr. Obama sees

the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq as “problems that need managing” while he

pursues his mission of transforming the nation. Defense Secretary Robert Gates,

speaking on the record, said, “He’s got a very full plate of very big issues,

and I think he does not want to create the impression that he’s so preoccupied

with these two wars that he’s not addressing the domestic issues that are

uppermost in people’s minds.”

Wars are not problems that need managing, which suggests that they will always

be with us. They are catastrophes that need to be brought to an end as quickly

as possible. Wars consume lives by the thousands (in Iraq, by the scores of

thousands) and sometimes, as in World War II, by the millions. The goal when

fighting any war should be peace, not a permanent simmer of nonstop maiming and

killing. Wars are meant to be won — if they have to be fought at all — not

endlessly looked after.

One of the reasons we’re in this state of nonstop warfare is the fact that so

few Americans have had any personal stake in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

There is no draft and no direct financial hardship resulting from the wars. So

we keep shipping other people’s children off to combat as if they were some sort

of commodity, like coal or wheat, with no real regard for the terrible price so

many have to pay, physically and psychologically.

Not only is this tragic, it is profoundly disrespectful. These are real men and

women, courageous and mostly uncomplaining human beings, that we are sending

into the war zones, and we owe them our most careful attention. Above all, we

owe them an end to two wars that have gone on much too long.

We Owe the Troops an

Exit, NYT, 30.8.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/31/opinion/31herbert.html

Obama to Make 2nd Oval Office Speech

August 30, 2010

The New ork Times

By HELENE COOPER

WASHINGTON — For only the second time since he took office, President Obama

will speak to the nation from the Oval Office on Tuesday night, in an address

meant to convey that he has kept one of the central promises of his campaign:

withdrawing American combat troops from Iraq.

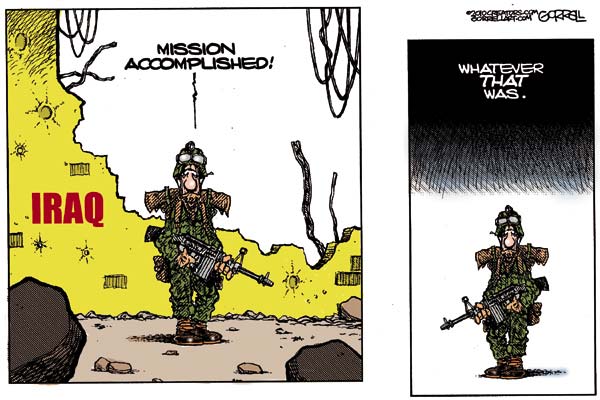

Mr. Obama will steer clear of the “mission accomplished” tone that President

George W. Bush struck so famously seven years ago — and that subsequently came

back to haunt him as Iraq fell into further chaos. “You won’t hear those words

coming from us,” said the White House press secretary, Robert Gibbs.

But Mr. Obama will still strike a promises-kept theme, aides said, even as he

seeks to reconcile his opposition to the Iraq war — and his opposition to the

so-called troop surge, which Republicans and many military officials credit for

the decrease in violence in Iraq — with his role as a wartime commander in chief

seeking to credit his troops with carrying out a difficult mission. The

president, his aides said, will seek to honor the American soldiers who served

in Iraq.

On Monday, Mr. Obama made an unannounced trip to Walter Reed Army Medical Center

in Washington to visit with soldiers wounded in Iraq, and on Tuesday morning he

will travel to Fort Bliss, Tex., to meet with American troops.

In his Oval Office address, Mr. Obama will also try to put into larger context

“what this drawdown means to our national security efforts in Afghanistan and

Southeast Asia and around the world as we take the fight to Al Qaeda,” Mr. Gibbs

said. That means speaking to the country about the American presence in

Afghanistan, a topic that the president has spoken about only in general terms

since announcing his Afghanistan policy last December.

“I’m a general fan of how he’s handled the two wars,” said Michael E. O’Hanlon,

senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “But if there’s a consistent

weakness, it’s the episodic quality in how we hear from him about the wars. He

temporarily engages.”

Mr. Obama, Mr. O’Hanlon said, should use his Oval Office pulpit on Tuesday night

to explain in clear terms exactly what American troops have been doing in

Afghanistan over the past few months, and, looking forward, what his aims are

over the next year.

Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. arrived in Baghdad on Monday to commemorate

the official end of the American combat mission in Iraq, which saw about seven

years of fighting, and 4,400 American soldiers and countless Iraqis killed. But

for all of the celebration in Washington and among American officials in

Baghdad, this week’s commemorations come as Iraq is wrestling with a political

stalemate that has been in place since an inconclusive general election about

six months ago.

Administration officials have hastened to say that the stalemate simply means

that — in Mr. Biden’s words — “politics has broken out in Iraq.”

Michael R. Gordon contributed reporting from Baghdad.

Obama to Make 2nd Oval

Office Speech, NYT, 30.8.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/31/world/middleeast/31prexy.html

Abandoned in Baghdad

August 30, 2010

The New York Times

By SAURABH SANGHVI

New Haven

AS the United States ends combat operations in Iraq today, it is leaving behind

the thousands of Iraqis who worked on behalf of the American government — and

who fear their lives and families are threatened by insurgents as a result.

In 2008 Congress significantly expanded a program that provided these Iraqis

with visas to immigrate to the United States. But in the intervening years, the

program has proven to be a bureaucratic failure. Unless we improve the

resettlement process for our Iraqi allies, their lives will continue to be in

danger long after the last American soldier has returned home.

The basic problem with the program, called the special immigrant visa, is that

it treats applicants — many of whom are on the run and often facing death

threats — as if they were being audited by the Internal Revenue Service.

First, to apply for a visa Iraqis have to get a letter of clearance from the

American Embassy, a step that can involve bizarre requirements: for example, the

embassy has at times asked applicants who were low-level employees of major

contractors to list all contracts between their former employers and the

American government, information they almost certainly don’t have.

The process also throws up unexpected hurdles. Minor issues — like whether the

applicant provides two letters of recommendation or one letter that is

co-signed, or whether the letter comes on the appropriate letterhead — have

delayed applications for months.

Embassy approval is just the first step. The applicant must then send the

paperwork through the unreliable Iraqi postal service to Nebraska — a challenge

in its own right — and then go through two more similarly bureaucratic approval

rounds, each with different government entities.

A single stage can take months to complete, and applicants receive little word

in the meantime about where they stand. One senior State Department official

said at a recent hearing that the program is more difficult for applicants to

navigate than the refugee process it was supposed to bypass.

Indeed, while applicants who are rejected for refugee status can at least ask

for a limited review of their cases, Iraqis who go through the special immigrant

visa process have little recourse if they are rejected.

One Iraqi I know who submitted his paperwork in January 2009 was rejected five

months later, before any interview and despite passing a background check. Even

his former supervisors could not uncover the reason for his rejection. The

embassy said he could reapply, but it gave no guidance about what he could do

differently. In the meantime, he has been shot at and nearly killed by

militants. He remains in hiding in Iraq.

Given such obstacles, it’s no surprise that relatively few people have

successfully used the program: an Aug. 12 letter to the administration by 22

members of Congress noted that only 2,145 visas have been issued, even though

the program has 15,000 available slots.

Fortunately, there are some obvious ways to simplify the process. For starters,

the agencies involved should gather information on Iraqi employees from

contractors and internal databases so that they can verify the applicants’

employment records themselves — a step required by the original Congressional

legislation. That way applicants wouldn’t need to hunt down former employers

while avoiding insurgents.

The agencies should also allow Iraqis to submit their applications by e-mail,

and then bring their original documents to a subsequent interview. And they

should provide rejected applicants with sufficient information about why they

were denied visas and a fair, transparent process for challenging the decisions.

Some might worry that making it easier to apply would also increase the risk of

fraud. But these common-sense changes would streamline the process and lead to

better information sharing, which if anything would help prevent abuse of the

program.

True, the American Embassy in Baghdad has a lot of work on its plate right now.

But given the risks that our Iraqi allies have taken, fulfilling our promise to

help them immigrate to the United States is the least we owe them.

Saurabh Sanghvi, a third-year law student at Yale, is a student director of the

Iraqi Refugee Assistance Project.

Abandoned in Baghdad,

NYT, 30.8.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/31/opinion/31sanghvi.html

Restoring Names to Iraq War’s Unknown Casualties

August 30, 2010

The New York Times

By ANTHONY SHADID

BAGHDAD — In a pastel-colored room at the Baghdad morgue known simply as the

Missing, where faces of the thousands of unidentified dead of this war are

projected onto four screens, Hamid Jassem came on a Sunday searching for

answers.

In a blue plastic chair, he sat under harsh fluorescent lights and a clock that

read 8:58 and 44 seconds, no longer keeping time. With deference and patience,

he stared at the screen, each corpse bearing four digits and the word “majhoul,”

or unknown:

No. 5060 passed, with a bullet to the right temple; 5061, with a bruised and

bloated face; 5062 bore a tattoo that read, “Mother, where is happiness?” The

eyes of 5071 were open, as if remembering what had happened to him.

“Go back,” Hamid asked the projectionist. No. 5061 returned to the screen.

“That’s him,” he said, nodding grimly.

His mother followed him into the room, her weathered face framed in a black

veil. “Show me my son!” she cried.

Behind her, Hamid pleaded silently. He waved his hands at the projectionist,

begging him to spare her. In vain, he shook his head and mouthed the word “no.”

“Don’t tell me he’s dead,” she shouted at the room. “It’s not him! It’s not

him!”

No. 5061 returned to the screen.

She lurched forward, shaking her head in denial. Her eyes stared hard. And in

seconds, her son’s 33 years of life seemed to pass before her eyes.

“Yes, yes, yes,” she finally sobbed, falling back in her chair.

Reflexively, her hands slapped her face. They clawed, until her nails drew

blood. “If I had only known from the first day!” she cried.

The horror of this war is its numbers, frozen in the portraits at the morgue: an

infant’s eyes sealed shut and a woman’s hair combed in blood and ash. “Files

tossed on the shelves,” a policeman called the dead, and that very anonymity

lends itself to the war’s name here — al-ahdath, or the events.

On the charts that the American military provides, those numbers are seen as

success, from nearly 4,000 dead in one month in 2006 to the few hundred today.

The Interior Ministry offers its own toll of war — 72,124 since 2003, a number

too precise to be true. At the morgue, more than 20,000 of the dead, which even

sober estimates suggest total 100,000 or more, are still unidentified.

This number had a name, though.

No. 5061 was Muhammad Jassem Bouhan al-Izzawi, father, son and brother. At 9

a.m., on that Sunday, Aug. 15, his family left the morgue in a white Nissan and

set out to find his body in a city torn between remembering and forgetting,

where death haunts a country neither at war nor peace.

There is a notion in Islamic thought called taqiya, in which believers can

conceal their faith in the face of persecution. Hamid’s family, Sunnis in the

predominantly Shiite neighborhood of New Baghdad, engaged in their own.

As sectarian killings intensified in 2005 and Shiite militias stepped up

attacks, they hung two posters of Shiite saints near the apartment’s windows,

shattered in car bombings and patched with cardboard. To strangers, they changed

their tribal name from Izzawi to Mujahadi, hoping to blend in. They learned not

to say, “Salaam aleikum” — peace be upon you — in farewell, as more devout

Sunnis will do.

Burly and bearded, Muhammad was the most devout in the family, and perhaps the

least discreet. He allowed himself American action films, “Van Damme and

Arnold,” his brother recalled. But his routine was ordered by the call to

prayer, bringing him five times a day to the Arafat Mosque.

“We said, ‘Listen to us, just pray at home,’ ” Hamid recalled begging him.

“It’s in God’s hands if I’m killed,” he said his brother replied.

On July 1, 2005, at 5 a.m., guns clanged on their metal front door like brittle

bells. Muhammad’s mother opened it, and men dressed as police officers forced

her back. Barely awake, Muhammad clambered down the stairs in a white undershirt

and red pajamas. The men bundled him into a police pickup and drove off, leaving

his 2-month-old daughter, Aisha, and his wife and mother, who cried for help as

the headlights disappeared into the dawn.

In all, 11 men joined the ranks of the missing that morning.

Willing to Help, for $20,000

Shadowed by militias, the family found that going to the morgue was often too

dangerous, but as the weeks passed, Muhammad’s brother-in-law went anyway. He

found nothing. The family gave nearly $650 to a relative who had a friend who

knew a driver for a Shiite militiaman. A month later, he came back with no word,

but kept $100 for his time. Another acquaintance offered to help for $20,000.

“Where were we going to get that kind of money?” Hamid asked.

A chance encounter in August brought the family to the morgue. A neighbor had

found his father among the pictures in the Missing room. He was one of the 11.

Hamid is a quiet man in a city that does not embrace silence. Modest, even

bashful, he is full of abbreviated gestures, questions becoming stutters when

faced with authority.

Gingerly, he clutched a note from the morgue. No. 5061, it said, along with the

name of the police station, Rafidain, that had recovered his brother’s body. He

drove his family to the vast Shiite slum Sadr City, past a gas station named for

April 9, the date of Saddam Hussein’s fall, and a bare pedestal where the

dictator’s statue once stood.

Police officers in mismatched uniforms sprawled in chairs at the entrance, near

a barricade of razor wire laced through tires, a car seat and a fender that

suggested the city’s impermanence. “What do you want?” one of them barked at

Hamid.

The family needed a letter from the police station, the first step in claiming

Muhammad’s death certificate and finding out where he was buried. With Hamid

beside her, the mother pleaded to let them inside. For five years they had

looked for him, she said.

The policeman glared at her suspiciously. “If you’re lying, I’ll put you all in

jail right now,” he shouted.

“My son is dead, and this is what you say to us?” the mother answered.

The policeman turned his head in disgust.

“Dog,” he muttered under his breath.

Slogans litter Baghdad. They are scrawled on the blast walls that partition this

city of concrete. They proclaim unity from billboards over traffic snarled at

impotent checkpoints. The more they are uttered, it seems, the less resonant

they become.

“Respect and be respected,” read the one the family passed, entering the police

station.

They followed Kadhem Hassan, the weary 60-year-old police officer in charge of

records, whose office was around the corner from toilets piled with excrement.

“They keep throwing rocks at us at night,” he said, kicking shards of bricks

away from the entrance to his office, near a slogan that read, “Heroes.”

His office was bare but for a rickety desk and cabinets piled with curled,

yellowing files. A fan circulated the heat; Officer Hassan had bought it for

$20. Sitting in his chair, he endlessly shuffled files. In words slurred by

missing teeth, he told Hamid’s nephew to go buy paper if they wanted a letter.

Eventually, he found the police report of Muhammad’s death.

Dated July 3, 2005, it read: “We discovered 11 unidentified bodies, their hands

bound from behind, their eyes blindfolded and their mouths gagged. The bodies

bore signs of torture.”

“All of us were victims,” Officer Hassan told Hamid, in an attempt at sympathy.

“Who was the exception? No one was. Not the martyrs, not the policemen, no one.”

“If they just shot them, O.K.,” Hamid said. “But they beat them, tortured them

and then they burned them. Why? And those guys” — the politicians, he meant — “

are just watching.”

“Power and positions, that’s all they’re worried about,” Officer Hassan said.

“Let me be honest,” Hamid said, flashing rare anger at no one in particular.

“Just to tell the truth. It would have been better if we had stayed under Saddam

Hussein.”

The policeman shrugged and stayed silent.

A Bureaucratic Odyssey

From the Rafidain police station, carrying a letter on paper he had paid for,

Hamid went to the morgue. His letter, said a clerk there, Ihab Sami, was

incomplete.

“The police don’t understand and neither do you!” Mr. Sami shouted at him.

Quiet, Hamid shook his head and returned to Sadr City.

“Come tomorrow morning,” Officer Hassan told him.

He did. Sometimes with his mother, sometimes his nephew, he went back to the

morgue, the police station again, the courthouse in Sadr City and the morgue.

Over seven days, he collected papers, each with the number 5061.

“We lost someone,” Hamid said as he drove. “They should take it easy on us.” He

grew quiet. “I guess nothing ends easily,” he whispered, “for the living or the

dead.”

In a cauterized country caught between its haunted past and uncertain future,

death seems to shape life in Baghdad. As Hamid drove patiently through its

crumpled landscape, he passed the cemeteries whose tombstones read like an

inventory of war, one built on the day after the fall of Saddam Hussein, at a

riverside park, near pomegranate trees too desiccated to bear fruit.

“Whoever reads the Koran for me, cry for my youth,” read the marker for Oday

Ahmed Khalaf. “Yesterday I was living, and today I’m buried beneath the earth.”

Across the Tigris River was the Jawad Orphanage, where Hussein Rahim, who does

not know his age, played with other children whose parents had been killed in

the violence. An explosion entombed his family in their home in July 2008. He

lived because he was playing soccer. His father’s name, he thinks, was Ali. But

he can’t recall the name of his 6-month-old sister, nor his mother. They are the

past, he said, and “no one wants to talk about it.”

“I can’t forget,” Hamid said, on the eighth day of his odyssey.

A roadside mine had closed the street, and Hamid parked nearly a mile away. With

his nephew, he walked toward the office for unclaimed death certificates and

past a billboard that read, “Hand in hand, we’ll build Iraq together.”

Government offices under construction had grown dilapidated even before they

were finished. The carcasses of car bombs were piled on the side of the street.

“I don’t consider this my country anymore,” Hamid said. “Really, I feel like a

stranger. Not just me. Everyone does.”

The office — a flattering term for a ramshackle tan trailer with brown trim —

was down a dirt road, across from a nursery lined with unplanted pots. Here,

even the nursery was coiled in barbed wire.

“They don’t even put a sign out front,” Hamid complained.

Perky, with good-natured cheer that seemed at odds with her work, Maysoun Azzawi

sat inside with her harried and haggard assistant, Hajji Saleh. She dispatched

him to plumb the 100 notebooks — stacked upright and on their side, some with

binders missing, all with pages torn — to find the death certificate for 5061.

“Come on, hurry up!” she yelled at him. “Look for the old records! 2005!”

She turned to Hamid. “Are you a Sunni or Shiite?” she asked.

“Mixed,” he answered.

She nodded knowingly, then yelled again. “Hajji, are you going to find it or do

I have to come in there?”

He shuffled in, and she pored over the ledger, line after line of unidentified

dead, its pages blown by an air-conditioner propped up on two broken cinder

blocks.

“Whatever happened to us?” she asked, as she turned the pages, looking for 5061.

“There are good people here, brother, but God damn this country.”

“It’s here,” she said finally, and asked for a pen.

She pulled out the death certificate, written in red and numbered 946777. The

morgue had sent Muhammad’s body south for burial on July 22, she told Hamid, and

the undertaker was Sheik Sadiq al-Sheikh Daham. She handed him the onionskin

paper certificate.

“You have everything you need now,” she said. “You can go to Najaf.”

She kept the pen.

In the Valley of Peace

Najaf, the spiritual capital of Shiite Islam, is a city of the dead.

For more than a millennium, the deceased have arrived at its cemetery, the

Valley of Peace, seeking blessings in their burial near the golden-domed tomb of

Imam Ali, the revered Shiite saint. There are moments of beauty here — finely

rendered calligraphy on turquoise tiles, domes of a perfect symmetry that life

cannot share. But shades of ocher predominate, the tan brick of headstones

stretching to the horizon like supplicants awaiting an audience.

The cemetery receives the unknown, whether Sunni or Shiite.

Before the sun rose, on the ninth day after identifying his brother’s picture,

Hamid drove his three sisters, Muhammad’s wife and daughter and his mother past

Baghdad’s outskirts. American jets whispered through the sky. As the sun rose

gingerly, Hamid’s car passed the tomb of the Prophet Job.

In Hamid’s hand was his brother’s death certificate.

“Corrected,” it read simply.

Only the caretaker knew where Muhammad’s grave was; he had sketched its location

on a hand-drawn map in a red leather book bound by yellow tape. Three stacks of

bricks covered in hastily poured concrete marked it. “Unknown, 5061, July 2,

2005,” it read. Next to it was 5067, 5060 and so on, hundreds more, stretching

row after row, so cluttered that some of the dead shared a grave.

The women stumbled toward it, throwing sand on their heads in grief. Their

chorus of cries intersected with the Shiite lamentations of a nearby funeral.

Muhammad’s wife grasped the marker, as though it was incarnate. His sister

kissed the cement.

“How long have we looked for you, my son?” his mother screamed, tears turning

the sand on her face to mud. “All this time, and you’ve been suffering under the

sun.”

She shouted at Hamid and the others.

“Please dig him out! Let me see him. It’s been five years. Hamid! We haven’t

seen him. Show him to me, just show him to me for a little while.”

She turned to Muhammad’s daughter, Aisha.

“This is your child!” she yelled.

Wearing pink, Aisha paid no attention. Too young to know grief, she played with

dusty red plastic carnations, glancing at the rest of the dead, anonymous like

her father.

Hamid stayed back, his tears turning to sobs.

“There is nothing left to do,” he said, shaking his head.

An hour later, the family pulled away in Hamid’s car, his mother’s cries still

audible. “Let me take your place,” she moaned. It turned onto a ribbon of black

asphalt. For a moment, the car caught the glint of the sun, then disappeared

behind the countless tombs.

Behind them was 5061. With a brick, they had furrowed a line into the marker.

With a bottle of water, they had washed it, revealing a newly white tile in a

sea of brown.

Restoring Names to Iraq

War’s Unknown Casualties, NYT, 30.8.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/31/world/middleeast/31legacy.html

Nation Building Works

August 30, 2010

The New York Times

By DAVID BROOKS

The U.S. venture into Iraq was a war, but it was also a nation-building

exercise. America has spent $53 billion trying to reconstruct Iraq, the largest

development effort since the Marshall Plan.

So how’s it working out?

On the economic front, there are signs of progress. It’s hard to know what role

the scattershot American development projects have played, but this year Iraq

will have the 12th-fastest-growing economy in the world, and it is expected to

grow at a 7 percent annual clip for the next several years.

“Iraq has made substantial progress since 2003,” the International Monetary Fund

reports. Inflation is reasonably stable. A budget surplus is expected by 2012.

Unemployment, though still 15 percent, is down from stratospheric levels.

Oil production is back around prewar levels, and there are some who say Iraq may

be able to rival Saudi production. That’s probably unrealistic, but Iraq will

have a healthy oil economy, for better and for worse.

Living standards are also improving. According to the Brookings Institution’s

Iraq Index, the authoritative compendium of data on this subject, 833,000 Iraqis

had phones before the invasion. Now more than 1.3 million have landlines and

some 20 million have cellphones. Before the invasion, 4,500 Iraqis had Internet

service. Now, more than 1.7 million do.

In the most recent Gallup poll, 69 percent of Iraqis rated their personal

finances positively, up from 36 percent in March 2007. Baghdad residents say the

markets are vibrant again, with new electronics, clothing and even liquor

stores.

Basic services are better, but still bad. Electricity production is up by 40

percent over pre-invasion levels, but because there are so many more

air-conditioners and other appliances, widespread power failures still occur.

In February 2009, 45 percent of Iraqis said they had access to trash removal

services, which is woeful, though up from 18 percent the year before. Forty-two

percent were served by a fire department, up from 23 percent.

About half the U.S. money has been spent building up Iraqi security forces, and

here, too, the trends are positive. Violence is down 90 percent from pre-surge

days. There are now more than 400,000 Iraqi police officers and 200,000 Iraqi

soldiers, with operational performance improving gradually. According to an ABC

News/BBC poll last year, nearly three-quarters of Iraqis had a positive view of

the army and the police, including, for the first time, a majority of Sunnis.

Politically, the basic structure is sound, and a series of impressive laws have

been passed. But these gains are imperiled by the current stalemate at the top.

Iraq ranks fourth in the Middle East on the Index of Political Freedom from The

Economist’s Intelligence Unit — behind Israel, Lebanon and Morocco, but ahead of