|

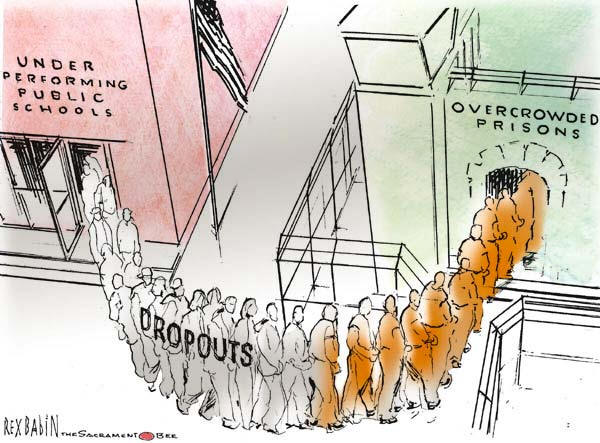

History > 2011 > USA > Justice > Prison / Jail (I)

Rex Babin

The Sacramento Bee

California

Cagle

26 January 2011

http://www.cagle.com/politicalcartoons/PCcartoons/PCbest9.asp

California Inmates

End 3-Week Hunger Strike

October 13, 2011

The New York Times

By IAN LOVETT

LOS ANGELES — The hunger strike at California state prisons has ended, the

Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation said Thursday.

Thousands of inmates at prisons across California had stopped eating over the

past three weeks in renewed protest against conditions of prolonged isolation in

security housing units, though the number of hunger strikers dwindled to fewer

than 600 this week.

But after negotiations on Thursday between the corrections department and

lawyers representing the inmates, strike leaders agreed to resume eating.

Corrections officials reiterated the reforms the department had agreed to at the

end of the previous hunger strike in July, which they said would take several

months to finalize, and “agreed to stay on its same course,” according to a news

release from the department.

The department had already agreed to a review of its policies for placing

inmates in security housing units.

But Carol Strickman, a lawyer with Legal Services for Prisoners with Children

who negotiated on behalf of the inmates, said that, most importantly, the

department had agreed to review the cases of all prisoners already in isolation

because of “validated” gang affiliation, rather than because of their behavior

while in prison.

“This is the first time the prisoners had heard that kind of review was in the

works,” Ms. Strickman said. “That new information, I believe, convinced them to

end the hunger strike.”

Erica Goode contributed reporting from New York.

California Inmates End

3-Week Hunger Strike, NYT, 13.10.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/14/us/california-inmates-end-3-week-hunger-strike.html

Exonerated of Murder, a Boxer Makes a Debut at 52

October 10, 2011

The New York Times

By PETER APPLEBOME

PHILADELPHIA — The television crew had him up at dawn doing the Rocky

fandango, dashing up the 72 stone steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and

dancing around in triumph like another over-the-hill, underdog pugilist who had

made it big.

Cliché or not, it is hard not to imagine the familiar trumpet score along with

the thwock, thwock, thwock of fists on punching bags as Dewey Bozella trains for

one of the least likely boxing matches in history.

After 26 years in New York State prisons, and two years after he was exonerated

of murder, Mr. Bozella will make his professional boxing debut on Saturday in

Los Angeles, at age 52, on the undercard of the light-heavyweight champion

Bernard Hopkins. (A mere 46 himself, Mr. Hopkins became the oldest fighter to

win a major world championship this May.)

Mr. Bozella’s other fight, in which he is seeking compensation for the half of

his life he spent behind bars, may be even more daunting than chasing victory in

the ring. But for now, Mr. Bozella is focused on what he says will be his one

and only professional bout.

“I want to go out there and give 100 percent and then move on with my life,” he

said. “This is not a career move. It’s a personal move and a way to let people

know to never give up on their dreams. My favorite quote is ‘Don’t let fear

determine who you are and never let where you come from determine where you’re

going.’ That’s what this is about.”

The product of a violent broken family and a hard life on the streets, Mr.

Bozella was a troubled 18-year-old in 1977 when Emma Crapser, 92, was murdered

in her Poughkeepsie, N.Y., home after returning from playing bingo. Six years

later, based almost entirely on the testimony of two criminals who repeatedly

changed their stories, he was convicted of the murder.

There was no physical evidence implicating Mr. Bozella. Instead, there was the

fingerprint of another man, Donald Wise, who was later convicted of committing a

nearly identical murder of another elderly woman in the same neighborhood. Mr.

Bozella was retried in 1990, and was offered a deal that would let him go free

in exchange for an admission that he committed the crime. He refused. A jury

convicted him again.

At Sing Sing, he earned a bachelor’s degree from Mercy College and a master’s

from the New York Theological Seminary. And he boxed in the prison’s “Death

House,” once the scene of electrocutions, then a boxing ring, where he became

Sing Sing’s light-heavyweight champion. At parole hearings, he repeatedly

refused to express remorse for the crime he did not commit. He would get out one

way, he said, either in a box or as an exonerated man. The box seemed more

likely.

In the end, he was saved by a miracle. The Innocence Project, a legal clinic

dedicated to overturning wrongful convictions, believing in his case but unable

to pursue it absent DNA evidence, referred it to the law firm WilmerHale.

Lawyers there eventually found the Poughkeepsie police lieutenant who had

investigated the case. He had retired, and Mr. Bozella’s was the only file he

had saved. It included numerous pieces of evidence favorable to Mr. Bozella that

had not been turned over to his lawyers. On Oct. 28, 2009, he walked out of the

courthouse in Poughkeepsie finally a free man.

He struggled to find work, eventually counseling former convicts while teaching

boxing at a Newburgh, N.Y., gym until ESPN became interested in his story. In

July, at its annual ESPY Awards, he was given its Arthur Ashe Courage Award,

whose past recipients have included Muhammad Ali, Pat Tillman and Nelson

Mandela. The offer to box professionally came as a result of that appearance.

But when he took the rigorous California State Athletic Commission test on Aug.

24 to get licensed to box in the state, he failed. After Labor Day, he began

working out in Philadelphia with the trainers for Mr. Hopkins. They were

skeptical.

“I’m thinking, ‘I’m going to kill this old guy,’ ” said Danny Davis, one of Mr.

Hopkins’s trainers. “There’s no way this guy can make it through my training.”

But Mr. Bozella got tougher, leaner and more nimble, dropping 10 pounds in

little more than a week. He sparred with, and took serious lumps from, a

world-class fighter: Lajuan Simon, a middleweight title contender. Mr. Bozella

took the test again on Sept. 29. This time he passed.

Officials said Mr. Bozella was believed to be the oldest fighter ever licensed

to box in California. Fighters that age are extremely rare but hardly unknown.

“The Ultimate Book of Boxing Lists,” by Bert Randolph Sugar and Teddy Atlas, has

a section on “Boxing’s Greatest Methuselahs” that includes Mr. Hopkins; Jem

Mace, the legendary 19th-century English boxer who fought at 59; and Saoul

Mamby, a former junior welterweight titleholder who fought in 2008 at the age of

60, making him the oldest fighter ever to appear in an officially sanctioned

bout.

Mr. Bozella, a cruiserweight — between light-heavyweights and heavyweights —

will not be fighting for a championship; he is taking on Larry Hopkins, 30, of

Houston, who is 0-3 as a professional (and is not related to Bernard Hopkins).

His purse in the pay-per-view bout will be in the very low four figures.

But even if hype and marketing are as much a part of boxing as quick feet and

sharp jabs, Mr. Bozella said the bout was anything but a stunt.

“You’ve seen the workout I went through, the pain, blood and bruises I’m

getting,” he said after four rounds sparring with Mr. Simon last week. “No one’s

giving me nothing for free. I can go out there and get knocked out, or I can

knock the other guy out. It’s that simple.”

Mr. Bozella hopes to open his own gym as a way to mentor youngsters, but beyond

its Hollywood touches, his feel-good story turns cloudier. The day after he

passed the boxing test, a federal judge threw out his lawsuit against Dutchess

County and the City of Poughkeepsie over the evidence that was not turned over

to his lawyers.

The decision was primarily based on a controversial Supreme Court ruling in the

case of Connick v. Thompson. By a 5-to-4 margin, the court, in a decision

written by Justice Clarence Thomas in March, threw out a $14 million jury award

to a former death row inmate freed after prosecutorial misconduct came to light.

The decision stated that only a pattern of misconduct in properly turning over

evidence could warrant financial compensation, no matter how egregious the

misconduct against a single defendant.

“I’m not going to disrespect the courts,” Mr. Bozella said. “I’d just like the

justice system to be fair. Same thing with boxing. If the judges are fair, then

the real winner wins. Just be fair. That’s it.”

Exonerated of Murder, a

Boxer Makes a Debut at 52, NYT, 10.10.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/11/nyregion/exonerated-of-murder-dewey-bozella-makes-a-boxing-debut.html

California Begins Moving Prison Inmates

October 8, 2011

The New York Times

By JENNIFER MEDINA

LOS ANGELES — Facing an unprecedented order from the Supreme Court to

decrease its inmate population by 11,000 over the next three months and by

34,000 over the next two years, California prisons last week began to shift

inmates to county jails and probation officers, starting what many believe will

be a fundamental and far-reaching change in the nation’s largest corrections

system.

Last spring, the Supreme Court ruled that overcrowding and poor conditions in

state prisons violated inmates’ constitutional rights and, in a first, ordered a

state to rapidly decrease its inmate population. Gov. Jerry Brown and the

Legislature approved a plan that would place many more offenders in the custody

of individual counties.

Under the plan, inmates who have committed nonviolent, nonserious and nonsexual

offenses will be released back to the county probation system rather than to

state parole officers. Those newly convicted of such crimes will be sent

directly to the counties, which will decide if they should go to a local jail or

to an alternative community program. And newly accused defendants may wear

electronic monitoring bracelets while they await trial.

“This is the largest change in the California state system in my lifetime,” said

Barry Krisberg, a law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, who

has watched the state prisons for decades and testified in the Supreme Court

case last year. “Given that what we had was completely broken and was the most

expensive, overcrowded and least effective in America, there’s some hope that

this will change it.”

The shift of prisoners to county facilities began Monday, and state officials

expect to satisfy the Supreme Court’s mandate by June 2013 — at which time they

must have reduced the state inmate population of 144,000, which put the prisons

at 180 percent capacity, to 110,000, or 135 percent of capacity. First, though,

they must reach the initial court-ordered benchmark by reducing the prison

population to 133,000 by December.

In what the state calls a realignment of the criminal justice system, the plan

places more responsibilities on the counties, and some local officials say they

are unprepared and underfinanced to get the job done. But state officials say

that keeping inmates closer to their communities will increase the chances that

they can be rehabilitated, rather than in and out of state prison.

For the last several years, state parole officers would often catch criminals on

technical parole violations, sending them back to prison for several weeks at a

time — a practice many derided as a revolving door.

The constant influx of new and former inmates also sharply increased the cost

for the state, because it must pay for a medical evaluation and several other

assessments every time an inmate enters the system.

Matthew Cate, the secretary of the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation,

said the state hoped that the counties would concentrate on rehabilitating

prisoners and helping them reintegrate into the community, something the state

system was never able to do. Figures show that nearly 70 percent of inmates in

California prisons end up there again.

“The catch-and-release way we had before was not working — I don’t know how

anyone could disagree with that,” Mr. Cate said. “The only alternative we had

was just a massive release of people from prison. Nobody seemed to want to talk

about that.”

But some city and county officials say that the changes are likely to overwhelm

local law enforcement agencies and that the state has not given them enough time

or money to prepare. Last week, Mayor Antonio R. Villaraigosa of Los Angeles and

the city’s police chief, Charlie Beck, said they would have to reassign 150

police officers to help monitor the former inmates.

Sheriff Scott R. Jones of Sacramento County has been one of the most outspoken

critics of the plan, saying it is likely to drive up crime. He called it a

“collision course with disaster,” because there is not enough money for the

counties.

“To do all the things that they are asking everyone to do will cost an enormous

amount of money, and we don’t have it,” Sheriff Jones said. “If this doesn’t

work, it’s not like we get to go back and try again — we’re going to be stuck

with the consequences.”

Sheriff Jones said the state might have been better off simply releasing 10,000

inmates, so it could use the extra time to figure out how to get more money or

create a more comprehensive system for counties. “It’s not like we’re ready,

because we’re not, and it’s not like we know what is best, because we don’t,” he

added. “The only thing that is driving this is a court demand.”

But Mr. Cate dismissed the criticisms, saying the state had no other choice and

had been coordinating plans for months.

“Everyone just wants to inoculate themselves from any kind of crime increase and

blame it on realignment,” Mr. Cate said. “This is some massive change. It’s

going to be subtle and happen over time.”

Counties across the state have been working “feverishly” to figure out their

plans to handle the new responsibilities, said Sheriff Mark Pazin of Merced

County, president of the California State Sheriffs’ Association.

“It’s a little tiring that we’re finally at the point where we have to do

something and people start to react by just hitting the panic button,” Sheriff

Pazin said.

Studies show that reduced sentences do not cause drastic increases in crime, he

said, and many counties are working on alternative programs. “We need to be

concentrating on what works best and how we can actually turn things around,” he

said.

Sheriff Pazin said Mr. Brown had reassured him that the state would consider

changing the way money is allocated to individual counties. Officials hope that

five years from now, they will be able to determine which counties have been

most effective at reducing the recidivism rate.

But several advocates for prisoners say they worry that the state is not doing

enough to ensure that the counties will consider alternatives to jail, and

several counties have said they will deal with the influx simply by adding more

beds to their jails. Many of the county jails across the state are already

overcrowded, and the Los Angeles County jails are being investigated by the

F.B.I. over accusations of inmate abuse by deputies.

“There are no kind of guiding principles or oversight or monitoring,” said

Donald Specter, the director of the Prison Law Office, which argued for the

prisoners in the Supreme Court case. “I think there will be extreme variations,

where some counties just will use the money to lock them up with no support and

others who really try to figure out real solutions.”

Any violent crime committed by one of the former inmates is likely to grab

headlines, but it will be years before the state can measure the impact of the

change.

“We don’t have a lot of options,” Mr. Cate said. “The question years from now

will really be: Did we avoid a disaster?”

California Begins Moving

Prison Inmates, NYT, 8.10.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/09/us/california-begins-moving-prisoners.html

Report Details Wide Abuse

in Los Angeles Jail System

September 28, 2011

The New York Times

By JENNIFER MEDINA

LOS ANGELES — One inmate said he was forced to walk down a hallway naked

after sheriff’s deputies accused him of stealing a piece of mail. They taunted

him in Spanish, calling him a derogatory name for homosexuals.

Another former inmate said that after he protested that guards were harassing a

mentally ill prisoner, the same deputies took him into another room, slammed his

head into a wall and repeatedly punched him in the chest.

And a chaplain said he saw deputies punching an inmate until he collapsed to the

ground. They then began kicking the apparently unconscious man’s head and body.

The examples are just a fraction of dozens of detailed allegations of abuse in

Los Angeles County’s Men’s Central Jail and Twin Towers, according to a report

that the American Civil Liberties Union is expected to file in Federal District

Court here on Wednesday. The Los Angeles County jail system, the nation’s

largest, is also the nation’s most troubled, according to lawyers, advocates and

former law enforcement officials.

“This situation, the length of time it has been going on, the volume of

complaints and the egregious nature are much, much worse than anything I’ve ever

seen,” said Tom Parker, a retired F.B.I. official who led the agency’s Los

Angeles office for years and oversaw investigations into the Rodney King beating

and charges of corruption in the Los Angeles Police Department. “They are

abusing inmates with impunity, and the worst part is that they think they can

get away with it.”

The system has a long history of accusations of abuse and poor conditions. The

A.C.L.U. filed a federal lawsuit 35 years ago, and an agreement eventually

allowed the organization to place monitors inside the jails. But those monitors

say that they receive six or seven complaints a week now, primarily from the two

large jails in downtown Los Angeles that house thousands of men. The F.B.I. has

also begun to investigate several episodes in the jails.

Sheriff Lee Baca has repeatedly dismissed any suggestion of a systemic problem

in the jails, saying that all allegations of abuse are investigated and that

most are unfounded.

This week, The Los Angeles Times reported that F.B.I. agents sneaked a cellphone

to a prisoner as part of an investigation. Sheriff Baca reacted to the

investigation angrily, saying that the agency did not know what it was doing and

was putting prisoners and guards in danger.

Sheriff Baca discussed the matter with a Justice Department official in a

meeting on Tuesday. Nicole Nishida, the sheriff’s spokeswoman, said that the

department thoroughly investigated all complaints of abuse that it received and

that most were unsubstantiated.

With California under an order from the United States Supreme Court to shed

thousands of inmates from the state prisons, county jails are expected to

receive many more inmates in the next year, which could aggravate overcrowding

and other problems. Officials from the Sheriff’s Department have said that they

will not place inmates from the state in the Men’s Central Jail, which they

concede is an antiquated building.

But lawyers from the A.C.L.U. say that the Los Angeles County system is, in many

ways, even worse than the state prisons that have been found unconstitutional.

They say that many complaints are never properly investigated, and that often

the very guards accused of abuse are in the room when an inmate is interviewed

about the complaint.

In the last several months, the civil rights group has amassed 70 declarations

from former prisoners and civilians who witnessed beatings. The statements

suggest few patterns — the complaints span all times of day and multiple units

in the jail. But, the A.C.L.U. says, the guards do seem to use the same terms

repeatedly, shouting, “Stop resisting!” and “Stop fighting!” while they hit

inmates, even when inmates are not moving or are in handcuffs.

Paulino Juarez, a Roman Catholic chaplain who has worked in the jail since 1998,

was visiting an inmate’s cell early one morning in February 2009 when he heard

several thumps and gasps in the hallway. When he moved to the cell door, he saw

three deputies hitting a man and yelling, “Stop fighting!”

“But he wasn’t fighting; he wasn’t even defending himself,” Mr. Juarez said in

an interview. “When they saw me, they froze. I was frozen, too. I didn’t say

anything. I was too shocked, and I was terrified.”

Mr. Juarez filed a report with the Sheriff’s Department but did not hear

anything about it for several months. More than two years later, during a

meeting with his supervisor and Sheriff Baca, Mr. Juarez was told that the

department found that the inmate had resisted going into his cell. There was no

record of Mr. Juarez’s report, although a guard indicated in the file that the

chaplain had exaggerated what he had witnessed. He was told that the inmate,

whose name he did not know at the time, had later been released.

“I really don’t trust anymore,” Mr. Juarez said. “They always say inmates are

liars and nobody believes them. But I saw them treated like this.”

While the sheriff has repeatedly dismissed complaints from prisoners, the number

of civilians who have witnessed beatings has steadily increased, showing the

brazenness of many of the guards in the jails, said Peter Eliasberg, legal

director for the A.C.L.U. Foundation of Southern California.

This year, Esther Lim, the current monitor for the A.C.L.U., said she saw

several deputies beat a man inside the Twin Towers jail, next door to Men’s

Central, as if he were a “human punching bag.” The attack was widely reported in

the local news media, and at the time a spokesman dismissed it, saying that Ms.

Lim should have reported it sooner and that the inmate was attacking the

deputies.

Mr. Eliasberg and Ms. Lim said that inmates who were beaten were routinely

placed for several days afterward in isolation, known as “the hole,” and were

often accused of assaulting the guards.

The A.C.L.U. plans to call for a wide-ranging federal investigation, and for

Sheriff Baca to resign.

Report Details Wide

Abuse in Los Angeles Jail System, NYT, 28.9.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/28/us/aclu-suit-details-wide-abuse-in-los-angeles-jail-system.html

The Lingering Injustice of Attica

September 8, 2011

The New York Times

By HEATHER ANN THOMPSON

Philadelphia

FORTY years ago today, more than 1,000 inmates at Attica Correctional Facility

began a major civil and human rights protest — an uprising that is barely

mentioned in textbooks but nevertheless was one of the most important rebellions

in American history.

A forbidding institution that opened in 1931, Attica, roughly midway between

Buffalo and Rochester, was overcrowded and governed by rigid and often

capricious penal practices.

The guards were white men from small towns in upstate New York; the prisoners

were mostly urban African-Americans and Puerto Ricans. They wanted decent

medical care so that an inmate like Angel Martinez, 21, could receive treatment

for his debilitating polio. They wanted more humane parole so that a man like L.

D. Barkley, also 21, wouldn’t be locked up in a maximum security facility like

Attica for driving without a license. They also wanted less discriminatory

policies so that black inmates like Richard X. Clark wouldn’t be given the worst

jobs, while white prisoners were given the best. These men first tried writing

to state officials, but their pleas for reform were largely ignored. Eventually,

they erupted.

Over five days, Americans sat glued to their televisions as this uprising

unfolded. They watched in surprise as inmates elected representatives from each

cellblock to negotiate on their behalf. They watched in disbelief as these same

inmates protected the guards and civilian employees they had taken hostage.

They also saw the inmates request the presence of official “observers” to ensure

productive and peaceful interactions with the state. These eventually included

the New York Times columnist Tom Wicker; the radical lawyer William M. Kunstler;

politicians like Arthur O. Eve, John R. Dunne and Herman Badillo; and ministers

as well as activists.

As the rebellion wore on, and the lawn around Attica filled with hundreds of

heavily armed state troopers, these observers worried that Gov. Nelson A.

Rockefeller, having already refused to grant amnesty to the inmates if they

surrendered, would turn to force. This, they knew, would result in a massacre.

Several observers begged the governor to come to Attica. In lieu of amnesty,

they reasoned, his presence might at least assure the inmates that the state

would honor any agreement it made with them and prevent any reprisals should

they end their protest. Rockefeller wouldn’t consider it.

On the morning of Sept. 13, 1971, he gave the green light for helicopters to

rise suddenly over Attica and blanket it with tear gas. As inmates and hostages

fell to the ground blinded, choking and incapacitated, more than 500 state

troopers burst in, riddling catwalks and exercise yards with thousands of

bullets. Within 15 minutes the air was filled with screams, and the prison was

littered with the bodies of 39 people — 29 inmates and 10 hostages — who lay

dead or dying. “I could see all this blood just running out of the mud and

water,” one inmate recalled. “That’s all I could see.”

Incredibly, state officials claimed that the inmates, not the troopers, had

killed the hostages. Meanwhile, scores of inmates who had survived the assault

were tortured. Enraged troopers, and not a few correctional officers, forced

these men, many of whom had been shot multiple times, to crawl naked across

shattered glass and to run a gantlet as fists, gun butts and nightsticks rained

down on their bodies. Investigators from the state police, the very entity that

had led the assault, were then asked to determine what had gone wrong — all but

guaranteeing that only inmates, not troopers, would face charges. Public opinion

toward the inmates, once sympathetic, gradually turned against them.

The hostages were also treated miserably. The state offered families of dead

hostages small checks, which they cashed to tide them over in this difficult

time, but it did not tell them that taking this money meant forgoing their right

to sue the state for sizable damages.

Much of the nation, however, never heard this history. Had it not been for the

legal fight waged by inmates to hold the state accountable, and the testimony

provided later by surviving hostages and their families, there might have been

no official record of these brutal acts.

In 1997, the inmates were awarded damages for the many violations of their civil

rights and, though the state fought that judgment, in 2000 it had to pay out a

settlement of $8 million. In 2005, the state reached a settlement with the

guards and other workers for $12 million. The vast majority of the inmates and

guards got far less than they deserved.

Despite having to pay damages, 40 years later, the State of New York still has

not taken responsibility for Attica. It has never admitted that it used

excessive force. It has never acknowledged that its troopers killed inmates and

guards. It has never admitted that those who surrendered were tortured, nor that

employees were misled.

We have all paid a very high price for the state’s lies and half-truths and its

refusal to investigate and prosecute its own. The portrayal of prisoners as

incorrigible animals contributed to a distrust of prisoners; the erosion of

hard-won prison reforms; and the modern era of mass incarceration. Not

coincidentally, it was Rockefeller who, in 1973, signed the law establishing

mandatory prison terms for possession or sale of relatively small amounts of

drugs, which became a model for similar legislation elsewhere.

As America begins to rethink the wisdom of mass imprisonment, Attica reminds us

that prisoners are in fact human beings who will struggle mightily when they are

too long oppressed. It shows as well that we all suffer when the state

overreacts to cries for reform.

Heather Ann Thompson, an associate professor of history at Temple University,

is writing a book on the Attica uprising.

The Lingering Injustice

of Attica, NYT, 8.9.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/09/opinion/the-lingering-injustice-of-attica.html

In California, Victims’ Families Fight for the Dead

August 19, 2011

The New York Times

By IAN LOVETT

SAN DIEGO — The other day, at the sprawling state prison here, Linda and

Alfred Tay sat in a cramped, windowless room, just feet from the man serving

time for murdering their son.

Quarters are close at parole hearings.

They listened as the inmate made his case for parole. And then, exercising their

rights as victims under California law, the Tays made their own case, pleading

with the parole board not to grant freedom to the man who killed their son. It

was the second time they had gone through this painful ritual.

“We constantly have a shadow hanging over our lives,” Ms. Tay told the

commissioners. “When you suffer such a horrific crime, there is never closure.”

The rights of families like the Tays to be heard has been a fundamental tenet of

a movement since California passed its first victims’ bill of rights three

decades ago — a model that has been followed by states across the nation.

Until recently, most of these parole hearings — however difficult they may have

been for the family members — had little practical importance: inmates serving

life sentences for murder were virtually never set free. Even on the rare

occasions when the parole board granted a release, California’s two previous

governors — Gray Davis, a Democrat, and Arnold Schwarzenegger, a Republican —

almost invariably overturned it.

But now, with a United States Supreme Court mandate in May to reduce the

populations of California’s overcrowded prisons, Gov. Jerry Brown has thus far

upheld 207 of the parole board’s 253 decisions to release convicted killers.

Already this year, more release dates granted to killers have been allowed to

stand than in any year since governors got the power to reverse them.

As a result, these hearings have taken on a new urgency for victims’ family

members — many of whom have seen themselves as the last line of defense between

a killer and freedom — because inmates are now more likely than ever to be

paroled.

For some family members, attending the hearings is cathartic, offering a voice

to those who feel powerless in the wake of crimes that have upended their lives.

But even as victims have gained the right to be heard, the laws have also

created unintended consequences — sometimes dividing families or resurrecting

traumas year after year.

“The emotional experience is beyond words,” said Harriet Salarno, who has spoken

at nine parole hearings, beginning in 1993, for the man who killed her daughter

32 years ago. “I’ve thought about not going many times. But I was fearful he

would get out.”

Despite an increased possibility of parole, the emotional and financial burdens

of attending hearings are too overwhelming for many families. Brandi Cambron,

29, testified last year against parole for her mother, who was convicted of

murdering Ms. Cambron’s younger brother. But she did not return this year from

her home in Virginia for the hearing near Los Angeles.

“As much as it’s fulfilling to go there and speak and be heard, it also reopened

all these old wounds that I’d worked so hard to close,” she said.

California has led the way in passing victims’ rights laws. It became the first

state to allow victims’ families to speak at parole hearings, and in 1982 passed

a victims’ bill of rights — one of the first major pieces of such legislation in

the country. More than 30 states have amended their constitutions to include

similar measures.

Parole commissioners and victims’ rights advocates say that victim statements

can have a major influence. They put a human face on a murder victim, who is

often referred to only as “the deceased” during a parole hearing, and make it

that much more difficult for the board to grant release.

Some victims who survived murder attempts show their scars — missing limbs or

disfiguring burns — while relatives detail the emotional trauma they have

endured.

“You need to be there so the board understands what this has done to your life,”

said Nina Salarno Ashford, a lawyer with Crime Victims United, a group that

helps represent some victims at parole hearings.

Ms. Salarno Ashford said the increase in parole grants upheld under Governor

Brown makes it all the more important for victims to attend hearings.

“The governor seems not to be taking a hard-line stance as Davis or

Schwarzenegger did,” she said. “It really highlights the necessity for victims

to go to these hearings, so the parole board can feel the full impact of the

crime.”

Like many such advocates, Ms. Salarno Ashford’s involvement with the issue is

personal: her sister Catina was murdered in 1979. Harriet Salarno, her mother,

quit her job and founded Crime Victims United, and the group has been one of the

foremost opponents of the plan to reduce prison overcrowding by releasing

inmates.

Few victims’ families — around 8 percent — actually attend parole hearings. But

for those that do, the process, however painful, can also be restorative.

Some victims eventually even stop opposing an inmate’s release. Katie James,

manager of victims’ services for the California Department of Corrections and

Rehabilitation, said those cases showed how well the process could work for the

families.

“When the family goes to multiple hearings over a long period of time, they kind

of get to know the inmate,” Ms. James said. “They get to see a gradual change in

the offender. They’re never going to forgive what the inmate did, but they can

be O.K. with what the parole board decides.”

Most victims, however, never reach that point. For some, the hearings become an

obsession. They skip happy events in the lives of their living children — high

school or college graduations — to honor a dead child at a parole hearing. For

older victims, hearings can take a toll on their health, Ms. James said.

“For some families, the hearings eat away at them, and destroy their other

relationships,” she said. “We try to encourage them to have a balance and let

someone else go instead. But some feel like it has to be them.”

If nothing else, as the Brown administration allows more inmates sentenced to

life to be paroled, more victims will be spared the pain of returning year after

year to parole hearings. But more families will also watch killers win release

dates, as the Tays did. Ms. Tay said she was considering writing to the

governor, in the hope that he would reverse the decision. “I would keep going

forever if I could,” she said.

Perhaps no one has gone to as many parole hearings as Debra Tate, the sister of

Sharon Tate, who was murdered in 1969 in the Manson Family killings. She has, by

her own count, spoken at dozens, perhaps even a hundred parole hearings: almost

every one of those held for the Manson killers since the mid-1990s.

So far, only one of the members of Charles Manson’s murderous cult has died:

Susan Atkins, in 2009. A few weeks before Ms. Atkins’s death, Ms. Tate spoke at

her final parole hearing. On the day Ms. Atkins died, Ms. Tate wore all black,

in memory of the murder victims.

“I cried one long alligator tear,” Ms. Tate said at the event. “It’s still a

life lost. She had nieces and nephews. It’s never just about one person.”

Over the course of 40 years, the two women had become part of each other’s

lives.

But Ms. Atkins’s death was not a relief, Ms. Tate said. “There are still so many

hearings to go to.”

In California, Victims’

Families Fight for the Dead, NYT, 19.8.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/20/us/20parole.html

Barbarous Confinement

July 17, 2011

The New York Times

By COLIN DAYAN

Nashville

MORE than 1,700 prisoners in California, many of whom are in maximum isolation

units, have gone on a hunger strike. The protest began with inmates in the

Security Housing Unit at Pelican Bay State Prison. How they have managed to

communicate with each other is anyone’s guess — but their protest is everyone’s

concern. Many of these prisoners have been sent to virtually total isolation and

enforced idleness for no crime, not even for alleged infractions of prison

regulations. Their isolation, which can last for decades, is often not

explicitly disciplinary, and therefore not subject to court oversight. Their

treatment is simply a matter of administrative convenience.

Solitary confinement has been transmuted from an occasional tool of discipline

into a widespread form of preventive detention. The Supreme Court, over the last

two decades, has whittled steadily away at the rights of inmates, surrendering

to prison administrators virtually all control over what is done to those held

in “administrative segregation.” Since it is not defined as punishment for a

crime, it does not fall under “cruel and unusual punishment,” the reasoning

goes.

As early as 1995, a federal judge, Thelton E. Henderson, conceded that so-called

“supermax” confinement “may well hover on the edge of what is humanly

tolerable,” though he ruled that it remained acceptable for most inmates. But a

psychiatrist and Harvard professor, Stuart Grassian, had found that the

environment was “strikingly toxic,” resulting in hallucinations, paranoia and

delusions. In a “60 Minutes” interview, he went so far as to call it “far more

egregious” than the death penalty.

Officials at Pelican Bay, in Northern California, claim that those incarcerated

in the Security Housing Unit are “the worst of the worst.” Yet often it is the

most vulnerable, especially the mentally ill, not the most violent, who end up

in indefinite isolation. Placement is haphazard and arbitrary; it focuses on

those perceived as troublemakers or simply disliked by correctional officers

and, most of all, alleged gang members. Often, the decisions are not based on

evidence. And before the inmates are released from the barbarity of

22-hour-a-day isolation into normal prison conditions (themselves shameful) they

are often expected to “debrief,” or spill the beans on other gang members.

The moral queasiness that we must feel about this method of extracting

information from those in our clutches has all but disappeared these days,

thanks to the national shame of “enhanced interrogation techniques” at

Guantánamo. Those in isolation can get out by naming names, but if they do so

they will likely be killed when returned to a normal facility. To “debrief” is

to be targeted for death by gang members, so the prisoners are moved to

“protective custody” — that is, another form of solitary confinement.

Hunger strikes are the only weapon these prisoners have left. Legal avenues are

closed. Communication with the outside world, even with family members, is so

restricted as to be meaningless. Possessions — paper and pencil, reading matter,

photos of family members, even hand-drawn pictures — are removed. (They could

contain coded messages between gang members, we are told, or their loss may

persuade the inmates to snitch when every other deprivation has failed.)

The poverty of our criminological theorizing is reflected in the official

response to the hunger strike. Now refusing to eat is regarded as a threat, too.

Authorities are considering force-feeding. It is likely it will be carried out —

as it has been, and possibly still continues to be — at Guantánamo (in possible

violation of international law) and in an evil caricature of medical care.

In the summer of 1996, I visited two “special management units” at the Arizona

State Prison Complex in Florence. A warden boasted that one of the units was the

model for Pelican Bay. He led me down the corridors on impeccably clean floors.

There was no paint on the concrete walls. Although the corridors had skylights,

the cells had no windows. Nothing inside could be moved or removed. The cells

contained only a poured concrete bed, a stainless steel mirror, a sink and a

toilet. Inmates had no human contact, except when handcuffed or chained to leave

their cells or during the often brutal cell extractions. A small place for

exercise, called the “dog pen,” with cement floors and walls, so high they could

see nothing but the sky, provided the only access to fresh air.

Later, an inmate wrote to me, confessing to a shame made palpable and real: “If

they only touch you when you’re at the end of a chain, then they can’t see you

as anything but a dog. Now I can’t see my face in the mirror. I’ve lost my skin.

I can’t feel my mind.”

Do we find our ethics by forcing prisoners to live in what Judge Henderson

described as the setting of “senseless suffering” and “wretched misery”? Maybe

our reaction to hunger strikes should involve some self-reflection. Not allowing

inmates to choose death as an escape from a murderous fate or as a protest

against continued degradation depends, as we will see when doctors come to make

their judgment calls, on the skilled manipulation of techniques that are

indistinguishable from torture. Maybe one way to react to prisoners whose only

reaction to bestial treatment is to starve themselves to death might be to do

the unthinkable — to treat them like human beings.

Colin Dayan, a professor of English at Vanderbilt University, is the author of

“The Law Is a White Dog: How Legal Rituals Make and Unmake Persons.”

Barbarous Confinement,

NYT, 17.7.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/18/opinion/18dayan.html

Casey Anthony Freed From Jail, Slips From View

July 17, 2011

The New york Times

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

ORLANDO, Fla. (AP) — Casey Anthony was freed from a Florida jail early

Sunday, 12 days after she was acquitted of murder in the death of her 2-year-old

daughter Caylee in a verdict that drew furious responses and even threats from

people across the U.S. who had followed the case with rapt attention.

Wearing a pink Polo T-shirt and blue jeans, Anthony left the jail at 12:14 a.m.

with her attorney, Jose Baez. After three years behind bars, Anthony was given

$537.68 in cash from her jail account and escorted outside by two sheriff's

deputies armed with semi-automatic rifles. Neither Anthony nor Baez said

anything to reporters and protesters gathered outside.

Anthony, looking somber with her eyes cast downward, said "thank you" to a

jailer in the few seconds it took to escort her to the waiting SUV.

"It is my hope that Casey Anthony can receive the counseling and treatment she

needs to move forward with the rest of her life," Baez said in a statement

released to reporters.

News helicopters briefly tracked the SUV through Orlando's streets, but she

quickly vanished from public view.

"This release had an unusual amount of security so, therefore, in that sense, it

would not be a normal release," Orange County Jail spokesman Allen Moore said.

"We have made every effort to not provide any special treatment for her. She's

been treated like every other inmate."

Moore said there were no known threats received at the jail. Officials had a

number of contingency plans in place, including plans in case shots were fired

as she was being released.

After Anthony left the jail, the news helicopters followed the SUV to a covered

parking garage at a downtown Orlando office building. The SUV never reemerged

and other cars left that area, but it could not be seen if Anthony was in any of

them.

A short time later, there was police activity as two vehicles pulled up to a

twin-engine private jet at Orlando Executive Airport but no one saw Anthony get

out and onto the plane. The news helicopter shots showed only some middle-aged

men with luggage and golf travel bags. That plane took off shortly after 1 a.m.

Sunday for Ohio, the home state of Anthony's parents.

As midnight approached, upward of 100 spectators had gathered outside the jail's

booking and release center, where plastic orange barricades had been erected.

The crowd included about a half-dozen, sign-carrying protesters who had gathered

despite a drenching thunderstorm earlier. Onlookers had varied reactions to her

release from the jail, where seven or eight deputies in bullet-proof vests

patrolled the area. At least one officer carried an assault weapon and about

five officers patrolled on horseback.

"She is safer in jail than she is out here," said Mike Quiroz, who drove from

Miami to spend his 22nd birthday outside the jail. "She better watch her butt.

She is known all over the world."

Lamar Jordan said he felt a pit in his stomach when he saw Anthony walking free.

"The fact that she is being let out, the fact that it is her child and she

didn't say what happened, made me sick," Jordan said.

Not all of those who gathered condemned the 25-year-old.

"I'm for Casey," said Kizzy Smith, of Orlando. "She was proven innocent. At the

end of the day, Caylee is at peace. We're the ones who are in an uproar."

Since her acquittal on murder charges on July 5, Anthony was finishing her

four-year sentence for telling investigators several lies, including an early

claim that Caylee was kidnapped by a nonexistent nanny. With credit for the

nearly three years she's spent in jail since August 2008 and good behavior, she

had only days remaining when she was sentenced July 7.

The case drew national attention ever since Caylee was reported missing. Cable

network HLN aired the entire trial, with pundit Nancy Grace dissecting the case

nightly. Vitriol poured into social networking sites after the acquittal, with

observers posting angry messages on Twitter and Facebook's "I Hate Casey

Anthony" page.

Outraged lawmakers in several states responded by proposing so-called Caylee's

laws that would allow authorities to prosecute parents who don't quickly report

missing children. And many still speculate about what really happened to Caylee:

Was she suffocated with duct tape by her mother, as prosecutors argued? Or did

she drown in an accident that snowballed out of control, as defense attorneys

contended?

Now that she is free, it's not clear where Anthony will stay or what she will do

next.

Her relationship with her parents, George and Cindy, has been strained since

defense attorneys accused George Anthony of molesting Casey when she was young.

They also said George Anthony made Caylee's death look like a homicide after the

girl accidentally drowned in the family pool.

Caylee's remains were found in December 2008 in woods near the home Casey

Anthony shared with her parents. George Anthony has adamantly denied covering up

his granddaughter's death or molesting Casey Anthony when she was a child. Baez

argued during trial that the alleged abuse resulted in psychological issues that

caused her to lie and act without apparent remorse after Caylee's death. But

defense attorneys never called witnesses to support their claims.

Prosecutors alleged that Anthony suffocated her daughter with duct tape because

motherhood interfered with her desire for a carefree life of partying with

friends and spending time with her boyfriend. However, some jurors have told

various media outlets that the state didn't prove its case beyond a reasonable

doubt as required for a conviction — though some have said they believe she

bears some responsibility in the case.

Defense attorneys and sheriff's officials have declined to say where Anthony was

headed. What Anthony will do to make a living also remains unknown. Anthony, a

high school dropout, hasn't had a job since 2006.

One of her attorneys, Cheney Mason, said Friday that Anthony was scared to leave

jail, given the numerous threats on her life and the scorn of a large segment of

the public that believes she had something to do with the June 2008 death.

Her attorneys have said she has received numerous threats, including an email

with a manipulated photo showing their client with a bullet hole in her

forehead.

Security experts have said Anthony will need to hole up inside a safe house

protected by bodyguards, perhaps for weeks, given the threats.

Greene also said Friday that Anthony was emotionally unstable and needed "a

little breathing room" after her draining two-month trial.

The lies that were the basis of her conviction on the misdemeanor charges began

in mid-July 2008, about a month after Caylee was last seen alive. Around the

time the girl disappeared, Casey Anthony had begun staying with friends and not

with her parents. When Anthony's mother Cindy began asking about Caylee, Anthony

told her she was staying with a nanny named Zanny.

In mid-July, George and Cindy Anthony were notified that their car had been

impounded after it was abandoned in a check-cashing store's parking lot. When

the picked up the car, George Anthony — a former police officer — and the

impound lot manager both said it smelled like a dead body had been inside.

Cindy Anthony then tracked down her daughter at a friend's apartment and when

she couldn't produce Caylee, called the sheriff's office on July 15, 2008. The

court found she lied to investigators about working at the Universal Studios

theme park, about leaving her daughter with a nanny, about telling two friends

that Caylee had been kidnapped and about receiving a phone call from her.

Mike Silva, 26, a makeup artist from Orlando, came to the jail Saturday night

with a friend. Silva said he was surprised how there was not chaos. He said it

was probably in her best interested to leave Orlando. "Why would she stay here?

Everyone in Orlando knows her damn face."

Tad Campbell, a 50-year-old personal trainer from Orlando is glad the trial is

over. But, he added, "I think the general consensus is that she got away with

murder."

Casey Anthony Freed From

Jail, Slips From View, NYT, 17.7.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2011/07/17/us/AP-US-Casey-Anthony.html

In a California Prison,

Bunk Beds Replace Pickup Games

May 24, 2011

The New York Times

By JENNIFER MEDINA

CHINO, Calif. — The basketball hoops jimmied up to the ceiling prove that

this dingy space was a gym once upon a time. But for years now, the windowless

space has served as a de facto cell for dozens of prisoners at the California

Institution for Men.

The rows of bunk beds, just a few inches apart, covered almost every empty space

on the floor Tuesday afternoon. The gap between most beds allowed only the

thinnest of inmates to stand comfortably. A few prisoners wandered around, but

most simply rested on their thin mattresses, reading or dozing. As a rule, they

go out to the yard just two or three times a week.

Ominous messages stenciled on the walls signaled the tension: “Caution: No

warning shots will be fired.” Two guards mind the 200 prisoners, while another,

known as a gunner, watches from up high, ready to intervene at any moment.

It would be hard to call the cavernous cell anything but crowded. Still, there

are fewer people in it than there were just a few months ago, when triple bunk

beds lined the wall. Now, those have been converted to hold just two inmates.

“That helped,” said Michael Collins, a 49-year-old inmate who sits a few feet

from a dank corner converted into a group of metal toilets and open shower

stalls. “We have less people using the bathroom now. If you just mind your

business and stay in your bed, it’s O.K.”

But according to a Supreme Court ruling issued Monday, California — which has

the highest overcrowding rate of any prison system in the country — must

eliminate rooms like this at its facilities across the state, shedding some

30,000 prisoners over the next two years.

The problem is not new. For decades, the prison population has steadily risen,

largely because of tougher mandatory sentencing laws. The overcrowding has led

to riots, suicides and killings of inmates and guards over the last several

years.

Matthew Cate, the secretary of the California Department of Corrections and

Rehabilitation, said conditions had actually improved since the filing of the

lawsuit in 2006 that ended with Monday’s court decision. There are now roughly

143,000 inmates in the state’s prisons, down from 162,000 in 2006, in part

because the state has sent some 10,000 inmates to out-of-state facilities.

While there were once nearly 20,000 inmates in spaces not meant for housing,

commonly referred to as “bad beds,” that number has dropped to 6,600.

“It’s not perfect, but we haven’t been at those kinds of levels since the early

1990s,” Mr. Cate said. “The standard that I use personally is: are the prisons

clean, are the staff positions filled and are prisoners complaining about care?

I think that conditions are good on a day-to-day basis on the basics.”

But critics say that it is impossible for the state to deal with such a glutted

system. The lack of space can make it impossible, for example, to move inmates

from one prison to another for their own safety.

Mr. Cate said that the state was “the birthplace for every major prison gang in

the country,” but that the overcrowding paralyzes wardens from switching

prisoners to defuse racial and gang tensions.

“It’s an unacceptable working environment for everyone,” said Jeanne Woodford, a

former director of the state prisons and a former warden at San Quentin prison.

“Every little space is filled with inmates and they are housed where they

shouldn’t be housed, and every bed is full. It leads to greater violence, more

staff overtime and a total inability to deal with health care and mental illness

issues.”

One major impact of the overcrowding, and a centerpiece of the Supreme Court’s

ruling, is the lack of adequate health care for prisoners with mental illness or

other chronic medical conditions.

In 2005, a federal official began overseeing California’s prison health care

system after a judge ruled that the state was giving substandard medical care

for prisoners. Now, Mr. Cate said, roughly 90 percent of all clinical positions

are filled, although that rate varies among the prisons.

Donald Specter, the director of the Prison Law Office who argued against the

state before the Supreme Court, said that medical care was still wanting.

“There are not enough beds for the mentally ill, you have prisons all over the

state who are flunking by every measure in taking care of chronic conditions

like H.I.V. and diabetes and high blood pressure,” Mr. Specter said, citing

several recent reports by the state’s inspector general.

Mr. Cate concedes that the state is doing little to rehabilitate prisoners and

has almost no space to run programs that would keep them from landing back here

again.

“There’s far too much idleness, and that’s the thing that concerns me the most,”

he said. “When you have lockdown as often as we have to, it’s not setting anyone

up for anything good.”

Many of the prisoners here are serving sentences of less than a year for parole

violations. According to California law, any parolee caught violating the terms

of release could be sent back to state prison, creating a situation that many

call the “revolving door.” Under a plan Gov. Jerry Brown has proposed, those

inmates would instead be sent to county jails.

Robert Caldera, 52, has spent much of his life floating in and out of the prison

system, most recently arriving at Chino after he did not report to his parole

officer. Mr. Caldera was convicted of second-degree robbery several years ago,

he said. Now, he spends his days reading the Bible with a group of inmates. He,

too, said the conditions had improved, but like nearly everyone else here, he

said the real problem is the bathroom.

“It’s nasty pretty much all the time,” he said. “There are holes in the walls

that have feces in them. It’s damp constantly so you don’t ever feel clean.”

Even from several feet away, it is possible to smell the scent of an overused

locker room. There is something that looks like mold on each of the walls and

one guard said they are constantly battling broken pipes and leaks.

The conditions at other California prisons have led to outbreaks of viruses,

causing officials to quarantine hundreds of prisoners at a time.

Correction officers in Chino say that while the crowding has eased, guarding as

many as 70 prisoners at a time is unspeakably stressful. Several said they

looked forward to the day when they would have a more manageable number of

inmates. But it can be hard for them to muster sympathy for their charges.

“It’s worse than this in the Navy and you don’t hear those guys complaining,”

said Robert Spejcher, an officer who oversees a room converted to hold 42

inmates. “We never really know what we’re dealing with and we never know how

long they are going to stay.”

In a California Prison,

Bunk Beds Replace Pickup Games, NYT, 25.5.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/25/us/25prison.html

Prison Ruling Raises Stakes in California Fiscal Crisis

May 23, 2011

The New York Times

By JENNIFER MEDINA

LOS ANGELES — The Supreme Court’s order to California to ease overcrowding in

the state’s prisons, by releasing tens of thousands of inmates if no other

solution can be found, will probably aid Gov. Jerry Brown’s plan to move more

inmates from state prisons to county jails.

But it is also sure to set off a fresh round of budget battling in the

financially distressed state as the governor and local officials insist on

ensuring state financing before changing the system.

The ruling on Monday has also already inspired a fresh round of political

recriminations, with some law enforcement officials and Republicans echoing the

Supreme Court’s dissenters by saying the release will result in more violence as

released inmates, unable to find jobs, return to their former way of life.

“We’re bracing for the worst and hoping for the best,” said Mark Pazin, the

Merced County sheriff and chairman of the state’s sheriffs’ association. “This

potential tsunami of inmates being released would have such an impact on local

communities. Each of those who would be released have really earned their

pedigree as a criminal. It could create real havoc.”

And since the court requires that the state reduce the population one way or

another, California’s residents were greeting the decision with a mix of

nervousness and fatalism. That anxiety is unlikely to be eased by the news that

about 150 prisoners took part in a fight on Sunday in the dining hall at San

Quentin State Prison in which four men were stabbed or slashed. The cause of the

melee was under investigation.

Matthew Cate, the secretary of the California Department of Corrections and

Rehabilitation, called the court ruling disappointing because it did not

recognize improvements the state had made over the last several years. But Mr.

Cate said state officials would push even harder for the Legislature to approve

the governor’s plan, which he said would save money over time.

“Our goal is to not release inmates at all,” Mr. Cate said, adding that the

governor’s plan would mostly address the overcrowding problem, although it would

take three to four years to do so, longer than the two-year timeline laid out by

the court. He said the state could apply for an extension and added, “I don’t

think we can guarantee anything at this point.”

With the state facing a $10 billion deficit, Republicans have refused to sign on

to the governor’s plan to ask voters to approve tax extensions. Under Mr.

Brown’s proposal, some of that money would go to the counties, which would have

responsibility for housing and rehabilitating the inmates.

According to Mr. Brown’s plan, no inmate convicted of violent, sex-related or

otherwise serious crimes would be sent to the county jail systems. And while

many counties have said that they can cope with the inmates, they say it would

be impossible without extra money from the state.

“The only logical way to deal with the court order in a manner that continues to

protect the public is to send some people to the counties,” said Paul McIntosh,

the executive director of the California State Association of Counties. “A

one-time release would be a terrible decision, and we need a fundamental change

in the way we deal with criminals. The state really needs to step up quickly to

give us the ability to deal with this.”

Lee Baca, the Los Angeles County sheriff, said the state, with the help of local

officials, should immediately begin devising a plan, particularly to assure the

public that hardened criminals would not soon be roaming the streets.

“The public does not want to see a violent predator slip through the cracks on

this,” Sheriff Baca said. “We have to assure them that the department of

corrections will not make a mistake on who gets released.”

Los Angeles County is expected to have some 11,000 prisoners come into its

system under the plan. Sheriff Baca said he was confident that the county had

programs to deal with the additional inmates and could do even more with

programs to reduce recidivism.

“But you can’t just foist the problem on us without any more money,” he said.

Donald Specter, who argued for the prisoners before the Supreme Court, called

the landmark ruling “fantastic” and said it would force the state to deal with

problems it had long tried to avoid.

“The state has a lot of options,” Mr. Specter said. “It can reduce sentences for

parole violations or change sentencing law or go along with the governor’s plan,

but it has to do something.”

In Sacramento, Sheriff Scott Jones was less enthusiastic. He said the ruling

could have “horrific consequences” in his jails, which are nearly filled to

capacity each day.

“Whatever money they don’t give us, we have to make up with letting go a

commensurate number of parolees or people who should be behind bars,” Sheriff

Jones said. “There has to be a better way, but I don’t think we are going to get

it here.”

Prison Ruling Raises

Stakes in California Fiscal Crisis, NYT, 23.5.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/24/us/24california.html

Juvenile Killers in Jail for Life Seek a Reprieve

April 20, 2011

The New York Times

By ADAM LIPTAK and LISA FAYE PETAK

CHARLESTON, Mo. — More than a decade ago, a 14-year-old boy

killed his stepbrother in a scuffle that escalated from goofing around with a

blowgun to an angry threat with a bow and arrow to the fatal thrust of a hunting

knife.

The boy, Quantel Lotts, had spent part of the morning playing with Pokémon

cards. He was in seventh grade and not yet five feet tall.

Mr. Lotts is 25 now, and he is in the maximum-security prison here, serving a

sentence of life without the possibility of parole for murder.

The victim’s mother, Tammy Lotts, said she lost two children on that November

day in 1999. One was a son, Michael Barton, who was 17 when he died. The other

was a stepson, Mr. Lotts.

“I don’t feel he’s guilty,” she said of Mr. Lotts in the living room of her

modest St. Louis apartment, growing emotional. “But if he was, he’s already done

his time. He should be released. Time served. If they think that’s too easy, let

somebody look over his case.”

As things stand now, though, the law gives Mr. Lotts no hope of ever getting

out.

Almost a year ago, the Supreme Court ruled that sentencing juvenile offenders to

life without the possibility of parole violated the Eighth Amendment’s ban on

cruel and unusual punishment — but only for crimes that did not involve

killings. The decision affected around 130 prisoners convicted of crimes like

rape, armed robbery and kidnapping.

Now the inevitable follow-up cases have started to arrive at the Supreme Court.

Last month, lawyers for two other prisoners who were 14 when they were involved

in murders filed the first petitions urging the justices to extend last’s year’s

decision, Graham v. Florida, to all 13- and 14-year-old offenders.

The Supreme Court has been methodically whittling away at severe sentences. It

has banned the death penalty for juvenile offenders, the mentally disabled and

those convicted of crimes other than murder. The Graham decision for the first

time excluded a class of offenders from a punishment other than death.

This progression suggests it should not be long until the justices decide to

address the question posed in the petitions. An extension of the Graham decision

to all juvenile offenders would affect about 2,500 prisoners.

Mr. Lotts, a stout man with an easy manner, said he was not reconciled to his

sentence. “I understand that I deserve some punishment,” he said. “But to be put

here for the rest of my life with no chance, I don’t think that’s a fair

sentence.”

Much of the logic of the Graham decision and the court’s 2005 decision banning

the death penalty for juvenile offenders, Roper v. Simmons, would seem to apply

to the new cases.

The majority opinions in both were written by Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, who

said teenagers deserved more lenient treatment than adults because they are

immature, impulsive, susceptible to peer pressure and able to change for the

better over time. Justice Kennedy added that there was an international

consensus against sentencing juveniles to life without parole, which he said had

been “rejected the world over.”

One factor cuts in the opposite direction. Justice Kennedy relied on what he

called a national consensus against the punishment for crimes that did not

involve killings. Juvenile offenders were sentenced to life without parole for

such nonhomicide crimes, he wrote, in only 12 states and even then rarely.

There does not appear to be such a consensus against life without parole

sentences for juveniles who take a life. That may be why opponents of the

punishment are focusing for now on killings committed by very young offenders

like Mr. Lotts.

That strategy follows the one used in attacking the juvenile death penalty,

which the Supreme Court eliminated in two stages, banning it for those under 16

in 1988 and those under 18 in 2005.

Kent S. Scheidegger, the legal director of the Criminal Justice Legal

Foundation, a victims’ rights group, said that categorical approaches were

misguided in general and particularly unjustified where murders by young

offenders were involved.

“Since I think Graham is wrong,” he said, “extending it to homicides would be

wrong squared.”

“Sharp cutoffs by age, where a person’s legal status changes suddenly on some

birthday, are only a crude approximation of correct policy,” he added. There are

around 70 prisoners serving sentences of life without parole for homicides

committed when they were 14 or younger, according to a report by the Equal

Justice Initiative, a nonprofit law firm in Alabama that represents poor people

and prisoners.

The effort to extend the Graham decision has so far been unsuccessful in the

lower courts. According to a study to be published in The New York University

Review of Law and Social Change by Scott Hechinger, a fellow at the Partnership

for Children’s Rights, 10 courts have decided not to apply Graham to cases

involving killings committed by the defendants, and seven others have said the

same thing where the defendants were accomplices to murders. Courts have reached

differing results, though, where the offense was attempted murder.

All of this suggests that the question left open in Graham may only be answered

by the Supreme Court. In March, lawyers with the Equal Justice Initiative asked

the justices to hear the two cases raising the question.

One concerns Kuntrell Jackson, an Arkansas man who was 14 when he and two older

youths tried to rob a video store in 1999. One of the other youths shot and

killed a store clerk.

The second case involves Evan Miller, an Alabama prisoner who was 14 in 2003

when he and an older youth beat a 52-year-old neighbor and set fire to his home

after the three had spent the evening smoking pot and playing drinking games.

The neighbor died of smoke inhalation.

In Mr. Lotts’s case, too, state and federal courts in Missouri have said that

his sentence is constitutional. In December, in a different case, the Missouri

Supreme Court divided 4-to-3 over the constitutionality of the punishment in a

case involving the killing of a St. Louis police officer.

A dissenting judge, Michael A. Wolff, wrote that “juveniles should not be

sentenced to die in prison any more than they should be sent to prison to be

executed.”

At the prison here, about 130 miles south of St. Louis, Mr. Lotts said he had

grown up around drugs and violence, and he acknowledged that he used to have a

combustible temper. But he said the years he spent living with his father and

Ms. Lotts were good ones.

He and his brother Dorell were inseparable, he recalled, from Ms. Lotts’s three

boys. The group was sometimes taunted because Quantel and Dorell were black and

the other boys were white.

“If you wanted to fight one of us,” he said, “you had to fight all of us.”

He said he recalled very little about assaulting Michael. But he said he knew

some things for sure.

“That’s my brother,” he said. “Why would I want to kill my brother? That’s not

what I set out to do. That’s not what I meant to do. That’s not what I intended

to do.”

Tammy Lotts said race figured in her stepson’s trial. “They said a black boy

stabbed a white boy,” she said. For years, state officials prohibited her from

visiting Mr. Lotts, fearing she would try to harm him. “I’m the victim’s

mother,” she said, shrugging.

At the prison last week, Mr. Lotts was wearing a handsome wedding ring, and it

prompted questions. Beaming, he said he had been married just a few weeks before

to a woman who had written to him after hearing him interviewed. He pointed to

where the ceremony had taken place, a couple of yards away, near the vending

machines.

Ms. Lotts attended the wedding, but only after satisfying herself that the bride

was a suitable match.

“She’s marrying my son,” Ms. Lotts explained.

Juvenile Killers in Jail

for Life Seek a Reprieve, NYT, 20.4.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/21/us/21juvenile.html

The Prosecution Rests, but I Can’t

April 9, 2011

The New York Times

By JOHN THOMPSON

New Orleans

I SPENT 18 years in prison for robbery and murder, 14 of them on death row. I’ve

been free since 2003, exonerated after evidence covered up by prosecutors

surfaced just weeks before my execution date. Those prosecutors were never

punished. Last month, the Supreme Court decided 5-4 to overturn a case I’d won

against them and the district attorney who oversaw my case, ruling that they

were not liable for the failure to turn over that evidence — which included

proof that blood at the robbery scene wasn’t mine.

Because of that, prosecutors are free to do the same thing to someone else

today.

I was arrested in January 1985 in New Orleans. I remember the police coming to

my grandmother’s house — we all knew it was the cops because of how hard they

banged on the door before kicking it in. My grandmother and my mom were there,

along with my little brother and sister, my two sons — John Jr., 4, and Dedric,

6 — my girlfriend and me. The officers had guns drawn and were yelling. I guess

they thought they were coming for a murderer. All the children were scared and

crying. I was 22.

They took me to the homicide division, and played a cassette tape on which a man

I knew named Kevin Freeman accused me of shooting a man. He had also been

arrested as a suspect in the murder. A few weeks earlier he had sold me a ring

and a gun; it turned out that the ring belonged to the victim and the gun was

the murder weapon.

My picture was on the news, and a man called in to report that I looked like

someone who had recently tried to rob his children. Suddenly I was accused of

that crime, too. I was tried for the robbery first. My lawyers never knew there

was blood evidence at the scene, and I was convicted based on the victims’

identification.

After that, my lawyers thought it was best if I didn’t testify at the murder

trial. So I never defended myself, or got to explain that I got the ring and the

gun from Kevin Freeman. And now that I officially had a history of violent crime

because of the robbery conviction, the prosecutors used it to get the death

penalty.

I remember the judge telling the courtroom the number of volts of electricity

they would put into my body. If the first attempt didn’t kill me, he said,

they’d put more volts in.

On Sept. 1, 1987, I arrived on death row in the Louisiana State Penitentiary —

the infamous Angola prison. I was put in a dead man’s cell. His things were

still there; he had been executed only a few days before. That past summer they

had executed eight men at Angola. I received my first execution date right

before I arrived. I would end up knowing 12 men who were executed there.

Over the years, I was given six execution dates, but all of them were delayed

until finally my appeals were exhausted. The seventh — and last — date was set

for May 20, 1999. My lawyers had been with me for 11 years by then; they flew in

from Philadelphia to give me the news. They didn’t want me to hear it from the

prison officials. They said it would take a miracle to avoid this execution. I

told them it was fine — I was innocent, but it was time to give up.

But then I remembered something about May 20. I had just finished reading a

letter from my younger son about how he wanted to go on his senior class trip.