|

History > 2011 > USA > War >

Afghanistan (I)

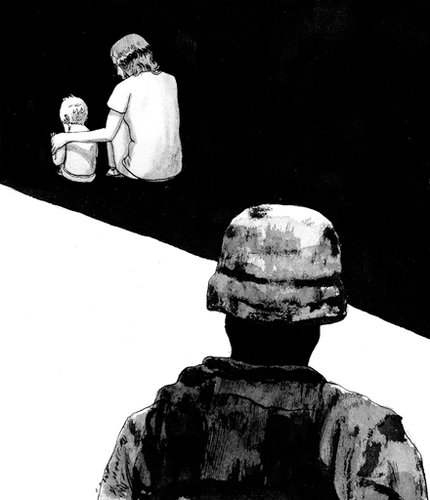

An injured woman

is

escorted out of “Finest” supermarket in central Kabul

after the suicide

attack.

Rahmat Gul/Associated

Press

Boston Globe > Big

Picture > Afghanistan, January 2011

February 3, 2011

http://www.boston.com/bigpicture/2011/02/afghanistan_january_2011.html

Suicide bomber kills 20

in Afghanistan's southeast

KHOST, Afghanistan | Mon Mar 28, 2011

2:52am EDT

Reuters

KHOST, Afghanistan (Reuters) - Three suicide bombers killed 20 people in an

attack on a construction firm in a restive province in southeastern Afghanistan,

government officials said Monday, with the Taliban claiming responsibility for

the assault.

Violence across Afghanistan has spiraled in the past year, with Taliban-led

militants stepping up their fight against the Afghan government and its Western

backers as Kabul prepares to take over responsibility for security gradually

from foreign forces.

An Interior Ministry statement said the attackers forced their way into the

firm's compound after killing a security guard and then detonated a truck packed

with explosives.

"As a result, 20 employees of the construction company were killed and 50 others

were injured," the statement said.

Mohebullah Sameem, governor of southeastern Paktika province, earlier put the

death toll from the attack in the remote Bermel district at 13.

He said the dead and wounded included employees of the firm and other civilians.

Construction crews and others working on infrastructure projects are frequently

targeted by insurgents.

Bermel shares a long border with lawless areas of neighboring Pakistan, where

insurgents are said to have safe havens from which they launch attacks inside

Afghanistan.

In an emailed statement to media, Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid claimed

the Islamist group had carried out the attack but said it had been on a military

base and that 49 foreign and Afghan troops had been killed and wounded.

Taliban insurgents often inflate casualties inflicted on Afghan government

forces and foreign troops.

Violence across Afghanistan last year reached its worst levels since the Taliban

were ousted by U.S.-backed Afghan forces in 2001, with civilian and military

casualties hitting record levels.

The violence underscores the challenges ahead as U.S. and NATO forces begin to

hand over security responsibility to Afghan troops, allowing foreign troops to

withdraw gradually from an increasingly unpopular war.

The process, announced last week, will begin with the handover of seven areas in

July and culminate in the withdrawal of all foreign combat troops by 2014.

(Reporting by Elyas Wahdat; Writing by Hamid Shalizi; Editing by Paul Tait and

Alan Raybould)

Suicide bomber kills 20 in Afghanistan's

southeast, R, 28.3.2011,

http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/03/28/us-afghanistan-attack-idUSTRE72R0W420110328

NATO Airstrike in Afghanistan

Claims Civilians

March 26, 2011

The New York Times

By RAY RIVERA

KABUL, Afghanistan — A NATO airstrike targeting Taliban fighters accidentally

killed and wounded an unspecified number of civilians Friday in the southern

province of Helmand, one of the most insecure regions in the country, NATO

officials said on Saturday.

NATO officials are investigating the episode. It occurred when the NATO-led

International Security Assistance Force called in an airstrike on two vehicles

believed to be carrying a Taliban leader and his associates. A NATO team

assessing the damage discovered the civilians following the airstrike. NATO

officials have not disclosed how many civilians were killed and wounded, and did

not say whether suspected Taliban were among the casualties.

Civilian casualties has been one of the most contentious issues in Afghanistan,

exacerbating tensions in the delicate relationship between international forces

and President Hamid Karzai. Mr. Karzai raised the issue again in a speech on

Tuesday, listing the reduction of civilian deaths as an issue that must be

addressed as Afghan forces begin taking over responsibility for security in some

areas of the country beginning this summer.

A United Nations report earlier this month said that 2,777 civilians were killed

in Afghanistan in 2010, the deadliest toll in more than nine years of war. The

Taliban were blamed for 75 percent of the deaths. The number of deaths by NATO

forces declined 26 percent. But a number of high-profile episodes have led to

continuing strains between NATO and the Afghan government.

Meanwhile, a NATO soldier was killed in an insurgent attack in southern

Afghanistan on Saturday. NATO does not release the identity or nationality of

casualties until their national authorities are notified.

NATO Airstrike in

Afghanistan Claims Civilians, NYT, 26.3.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/27/world/asia/27afghanistan.html

Soldier Expected to Plead Guilty

to Afghan Murders

March 23, 2011

The New York Times

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

JOINT BASE LEWIS-MCCHORD, Wash. (AP) — A 22-year-old soldier accused of

carrying out a brutal plot to murder Afghan civilians faces a court-martial

Wednesday in a case that involves some of the most serious criminal allegations

to arise from the U.S. war in Afghanistan.

Spc. Jeremy Morlock, of Wasilla, Alaska, has agreed to plead guilty to three

counts of murder, one count of conspiracy to commit assault and battery, and one

count of illegal drug use in exchange for a maximum sentence of 24 years, said

Geoffrey Nathan, one of his lawyers.

His client is one of five soldiers from Joint Base Lewis-McChord's 5th Stryker

Brigade charged in the killings of three unarmed Afghan men in Kandahar province

in January, February and May 2010. Morlock is the first of the five men to be

court-martialed — which Nathan characterized as an advantage.

"The first up gets the best deal," he said by phone Tuesday, noting that even

under the maximum sentence, Morlock would serve no more than eight years before

becoming eligible for parole.

According to a copy of the plea agreement, which was obtained by The Associated

Press, Morlock has agreed to testify against his co-defendants. In his plea

deal, Morlock said he and others slaughtered the three civilians knowing that

they were unarmed and posed no legitimate threat.

He also described taking a lead role in the January incident — lobbing a grenade

at the civilian while another soldier shot at him, and then lying about it to

his squad leader.

The court-martial comes days after a German news organization, Der Spiegel,

published three graphic photos showing Morlock and other soldiers posing with

dead Afghans. One image features Morlock grinning as he lifts the head of a

corpse by its hair.

Army officials had sought to strictly limit access to the photographs due to

their sensitive nature. A spokesman for the magazine declined to say how it had

obtained the pictures, citing the need to protect its sources.

Morlock told investigators the murder plot was led by Staff Sgt. Calvin Gibbs,

of Billings, Mont., who is also charged in the case; Gibbs maintains the reasons

behind the killings were legitimate.

Nathan said Morlock's mother, hockey coach and pastor are among the witnesses

who might testify on his behalf in court. He indicated the defense would argue

that a lack of leadership in the unit contributed to the killings.

"He's really a good kid. This is just a bad war at a bad time in our country's

history," Nathan said. "There was a lack of supervision, a lack of command

control, the environment was terrible. In his mind, he had no choice."

After the January killing, platoon member Spc. Adam Winfield, of Cape Coral,

Fla., sent Facebook messages to his parents saying that his fellow soldiers had

murdered a civilian and were planning to kill more. Winfield said his colleagues

warned him not to tell anyone.

Winfield's father alerted a staff sergeant at Lewis-McChord, which is south of

Seattle, but no action was taken until May, when a witness in a drug

investigation in the unit also reported the deaths.

Winfield is accused of participating in the final murder. He admitted in a

videotaped interview that he took part and said he feared the others might kill

him if he didn't.

Also charged in the murders are Pvt. 1st Class Andrew Holmes of Boise, Idaho,

and Spc. Michael Wagnon II of Las Vegas.

Seven other soldiers in the platoon are charged with lesser crimes, including

assaulting the witness in the drug investigation, drug use, firing on unarmed

farmers and stabbing a corpse.

Soldier Expected to

Plead Guilty to Afghan Murders, NYT, 23.3.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2011/03/23/us/AP-US-Afghan-Probe.html

Settling the Afghan War

March 22, 2011

The New York Times

By LAKHDAR BRAHIMI

and THOMAS R. PICKERING

DESPITE the American-led counterinsurgency in Afghanistan, the Taliban

resistance endures. It is not realistic to think it can be eradicated. Efforts

by the Afghan government, the United States and their allies to win over

insurgents and co-opt Taliban leaders into joining the Kabul regime are unlikely

to end the conflict.

The current strategy of “reintegration” may peel away some fighters and small

units, but it does not provide the political resolution that peace will require.

Neither side of the conflict can hope to vanquish the other through force.

Meanwhile, public support in Western countries for keeping troops in Afghanistan

has fallen. The Afghan people are weary of a long and debilitating war.

For their part, the Taliban have encountered resistance from Afghans who are not

part of their dedicated base when they have tried to impose their stern moral

code. International aid has improved living standards among Afghans in areas not

under Taliban control. That has placed new pressure on the Taliban, as has an

increasing ambivalence toward the Taliban in Pakistan.

The stalemate can be resolved only with a negotiated political settlement

involving President Hamid Karzai’s government and its allies, the Taliban and

its supporters in Pakistan, and other regional and international parties. The

United States has been holding back from direct negotiations, hoping the ground

war will shift decisively in its favor. But we believe the best moment to start

the process toward reconciliation is now, while force levels are near their

peak.

For the insurgents, the prospects for negotiating a share of national power are

not likely to improve by waiting until the United States withdraws most combat

forces by the end of 2014; on the contrary, the possibility that Americans might

find a way to maintain an enduring military presence past 2014 suggests that

perhaps the only way they can truly get the Americans out is with a negotiated

settlement.

A peace settlement would require a domestic element — a political order broadly

acceptable to Afghans — and an international element: severing Taliban ties to

Al Qaeda and containing rampant drug production and trafficking in Afghanistan.

Both elements would need to be negotiated along parallel tracks.

None of it will be easy: Afghans will have to allow for fair representation of

the Taliban in central and provincial governments; get the Taliban to abide by

election results; determine the proper role of Islamic law in regulating dress,

behavior and the administration of justice; protect human rights and women’s

rights; decide whether and how to bring perpetrators of war atrocities to

justice; and incorporate some Taliban fighters into police and security forces.

A guaranteed withdrawal of foreign forces, as the insurgency has demanded, would

almost certainly be part of a deal.

As chairmen of an Afghanistan task force with 15 members from nine countries,

organized by the Century Foundation, a nonpartisan research institution, we had

confidential conversations for nearly a year with dozens of people from almost

every side of the conflict.

Attention has rightly focused on the conflicting views about negotiating peace

with the Taliban among Mr. Karzai’s supporters, disaffected northerners and

other groups in Afghan society, not to mention hesitation in the international

community. But there is considerable division within the insurgency too.

The insurgency is not as fragmented as the old anti-Soviet mujahedeen alliance

was, but it is hardly monolithic, as we learned from conversations with Taliban

field commanders and individuals close to the Quetta Shura, which is made up of

Taliban leaders loyal to Mullah Muhammad Omar; the Haqqani network, an insurgent

group allied with the Taliban; and the Hezb-i-Islami group, which is led by the

longtime mujahedeen warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar.

Some of the people we interviewed stuck to hard-line positions: “There is

nothing to negotiate,” “Foreigners just need to leave Afghanistan,” “This is our

country,” and so on. But others engaged in a give-and-take, making clear they

wanted to see an end to violence and a start toward serious talks for peace.

For example, an adviser to the Haqqani network told us it was operationally

independent but recognized the authority of Mullah Omar — and therefore could

not negotiate separately with the Karzai government and the American-led

coalition. Yet we were also told that the network was eager to engage in

“friendly” dialogue.

Contrary to popular view, Pakistan cannot unilaterally dictate the outcome.

Pakistanis told us they were finding it increasingly difficult to prevent the

Afghan conflict from fueling extremist violence in their country. Pakistani

security officers who have provided long-time support for the Taliban run the

risk of events getting beyond their control.

A neutral international facilitator is needed to begin explorations with all

potential parties toward negotiation. The United Nations could appoint a

facilitator. Or a facilitator could be a group, an international organization, a

neutral state or a group of states. A settlement would require international

guarantees, aid, peacekeeping and enforcement of the agreement.

The international community has confronted equally intractable conflicts in

Cambodia, Bosnia and elsewhere and, with unity of purpose, resolved them.

Afghanistan is a particularly challenging case, but it is not hopeless.

Lakhdar Brahimi is a former United Nations special representative for

Afghanistan. Thomas R. Pickering is a former ambassador and under secretary of

state.

Settling the Afghan War,

NYT, 22.3.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/23/opinion/23brahimi.html

Photos Stoke Tension

Over Afghan Civilian Deaths

March 21, 2011

The New York Times

By ALISSA J. RUBIN

KABUL, Afghanistan — The release of explicit photographs of American soldiers

engaged in atrocities against Afghan civilians threatens to ignite tensions

between the Afghan and American governments and provide fodder for the Taliban’s

efforts to persuade ordinary Afghans that the foreign troops fighting here are a

malevolent force.

NATO officials and Western diplomats here have been steeling themselves for the

release, worried that it will further undermine relations with President Hamid

Karzai at a sensitive moment when there have been several recent episodes of

civilian casualties. Despite an overall decline in civilian casualties caused by

NATO forces, the incidents have tarnished the coalition campaign and put

President Karzai in the awkward position of having to explain why the country’s

allies are killing unarmed children and women.

Three photographs, published in the German magazine Der Spiegel, show members of

the self-designated “Kill Team” comprised of United States Army soldiers who are

accused of making a sport of killing innocent Afghans as they show off one of

their victims in a kind of trophy photo; another photograph shows two Afghan

civilians who appear to be dead.

Der Spiegel, which published the photographs in its March 20 print edition, but

has not yet put the photos online, has blurred the victims’ faces so that their

expressions can not be seen. While that makes the photographs somewhat less

inflammatory than they would be otherwise, it does not conceal the faces of the

soldiers, who look disconcertingly satisfied as they kneel next to an apparently

dead Afghan civilian.

Five of the soldiers involved in the killings, who were from the 5th Stryker

Brigade, 2nd Infantry Division, based at Joint Base Lewis-McChord in Washington

State, are now facing court martial proceedings for the deaths of three, unarmed

Afghan civilians. Seven other members of the unit are accused of lesser crimes.

The men are accused of faking combat situations to justify killing randomly

chosen Afghans with grenades and guns. The case came to light after one of the

soldiers informed military investigators about the killings; he was then beaten

so severely by other members of the unit for betraying them that he had to be

hospitalized.

The killings occurred in Maiwand district of Kandahar Province, one of the areas

that was dominated by the Taliban until major military operations last summer

and fall.

The pictures bring to mind those of the torture and humiliation suffered by

Iraqis at the hands of American troops in the Abu Ghraib prison, which came to

light in the spring of 2004. However, there were dozens of those pictures and

they clearly showed the victims’ faces, making their pain all the more apparent.

That case reverberated across the Muslim world in ways that this case has yet to

do in part because of the absence of photographs. The release of the images

threatens to change that.

However there was little reaction on Monday because it was Nowruz, the Persian

New Year, which is a national holiday and many families go out for picnics so

that even those few with internet access were less likely to see the photos. The

Afghan government had no comment on Monday on the release nor did the American

Embassy, which referred all questions to the American military.

The military and diplomats are hoping to mute public anger by emphasizing that

the soldiers in the Afghan case are being brought to justice. In a statement,

the Army described the actions as “repugnant” and underscored that a prosecution

was underway.

“The actions portrayed in these photographs remain under investigation and are

now the subject of ongoing U.S. court-martial proceedings,” the statement said.

“The United States Army is committed to adherence to the Law of War and the

humane and respectful treatment of combatants, noncombatants, and the dead,” the

statement added. “When allegations of wrongdoing by Soldiers surface, to include

the inappropriate treatment of the dead, they are fully investigated. Soldiers

who commit offenses will be held accountable as appropriate.”

One of the pictures published by Der Spiegel shows a soldier, Spc. Jeremy

Morlock of Wasilla, Alaska, posing, a grin on his face, next to a dead Afghan

who is mostly undressed, his body streaked with blood, as the soldier lifts up

the man’s head as if showing him off like a trophy. Specialist Morlock has been

charged with murder.

A second, similar photograph shows another soldier, Pfc. Andrew Holmes, who has

been charged with murder, kneeling next to the same corpse.

A third photograph shows two Afghan civilians who appear to be dead and whose

bodies have been arranged leaning limply against a post.

The photos had been described to reporters by defense lawyers for some of the

soldiers, but their release had been prohibited by a military judge. It is not

clear how Der Spiegel obtained the images.

Photos Stoke Tension

Over Afghan Civilian Deaths, NYT, 21.3.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/22/world/asia/22afghanistan.html

NATO air strike killed

two Afghan children in east - officials

KABUL | Tue Mar 15, 2011

10:56am GMT

Reuters

KABUL (Reuters) - An air strike by NATO-led forces killed two children as

they were watering fields in Afghanistan's eastern Kunar province late on

Monday, an Afghan official and lawmaker said.

The deaths occurred weeks after tensions between Afghan President Hamid Karzai

and his Western backers were inflamed by the killing of nine children who were

collecting firewood in the same province.

Last year was the most lethal for non-combatants since the Taliban were ousted

from power in 2001, with a 15 percent rise in civilian casualties to 2,777

according to a report by the United Nations last week. The report said

insurgents were responsible for three quarters of the deaths.

Abdul Marjan, district chief of Chawki in Kunar where the two brothers, aged 10

and 15, where killed on Monday, said the boys had been working on irrigation

channels before they were hit.

"They might have been mistaken for insurgents as they were carrying spades on

their shoulders," Marjan told Reuters.

Shahzada Shahid, a lawmaker from Kunar, said the pair were students who had gone

out to help work their father's fields.

Irrigation agreements between villagers in the area mean the family's land gets

access to river water only in the evening.

A spokesman for the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force,(ISAF) said

an air strike in Chawki on Monday evening targeted two suspected insurgents,

killing one and wounding another after they were seen planting a roadside bomb.

He added that ISAF were looking into media reports of civilian casualties.

NATO-led forces have significantly tightened rules governing air strikes and

night raids in the past two years, leading to a drop in civilian casualties, but

deaths are still relatively frequent and highly sensitive.

Karzai this month told General David Petraeus, the commander of U.S. and NATO

forces in Afghanistan, that his apology for the strike that killed nine children

was "not enough," and civilian casualties by foreign troops were "no longer

acceptable" to the Afghan government or people.

(Reporting by Rohullah Anwari, writing by Hamid Shalizi, editing by Emma

Graham-Harrison)

NATO air strike killed

two Afghan children in east - officials, R, 15.3.2011,

http://uk.reuters.com/article/2011/03/15/uk-afghanistan-civilians-nato-idUKTRE72E2XS20110315

Targeted civilian killings spiral

in Afghan war: U.N.

KABUL | Wed Mar 9, 2011

1:37am EST

Reuters

By Matt Robinson

KABUL (Reuters) - Targeted killings of civilians in Afghanistan doubled last

year, the United Nations said on Wednesday, as an expanding insurgency strikes

at Western efforts to build up the Afghan government and security forces.

Of 462 assassinations in 2010, half occurred in Taliban strongholds in the

south, where the United States says it has made most gains from a troop surge

aimed at turning the tide of the almost decade-old war.

In an annual report on the conflict's civilian toll, the United Nations said

there had been a 15 percent rise in the number of civilians killed to 2,777 in

2010, continuing a steady rise over the past four years.

Insurgents were responsible for 75 percent of those deaths.

Abductions rose 83 percent, and violence continued to spread from the south to

the north, east and west, the report said. Civilian deaths in the north, in

particular, rose 76 percent.

But the most "alarming" trend, it said, was a 105 percent increase in the

targeted killing of government officials, aid workers and civilians perceived to

be supportive of the Afghan government or NATO-led foreign forces.

The tactic threatens to undermine further the handover of responsibility for

security to the Afghan government, police and army starting this year, as

Washington and its NATO allies seek to draw down their combined 150,000-strong

force.

In many parts of Afghanistan, local governors live behind sandbags on U.S.

military outposts and government officials rarely travel to the areas they are

supposed to run.

The social and psychological impact of assassinations are "more devastating than

a body count would suggest," the U.N. report said.

"An individual deciding to join a district shura (meeting), to campaign for a

particular candidate, to take a job with a development organization, or to speak

freely about a new Taliban commander in the area, often knows that their

decision may have life or death consequences," it said.

"This suppression of individuals' rights also has political, economic and social

consequences as it impedes governance and development efforts."

VIOLENCE SPREADING

Civilian assassinations were up 588 percent and 248 percent in Helmand and

Kandahar provinces respectively, the main strongholds of the Taliban and the

focus of a U.S. troop surge.

The report noted a 26 percent decline in the number of civilian deaths caused by

coalition and Afghan forces.

Yet the killing of civilians in NATO operations has re-emerged as a major source

of friction between Kabul and its Western backers.

Last week, NATO helicopters gunned down nine Afghan boys collecting firewood,

drawing condemnation from Afghan President Hamid Karzai and apologies from

President Barack Obama and his top commander in Afghanistan, General David

Petraeus.

U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates repeated the apology on Monday during a

visit to assess security progress before Washington starts gradually withdrawing

troops in July.

Casualties among women rose 6 percent in 2010, and among children by 21 percent,

while "the spread and intensity of the conflict meant that more women and

children had even less access to essential services such as healthcare and

education."

Suicide attacks and homemade bombs claimed most lives.

Of the 440 deaths attributed to NATO and Afghan forces, 171 were caused by

aerial attacks, sharply down on 2009 as a result of tightened rules of

engagement.

The report noted a decline in civilian casualties in "night raids" by foreign

forces, a tactic ramped up under Petraeus to the anger of Afghans and Karzai's

government.

It attributed the drop to stricter regulations, but expressed concern about

"consistent implementation" and a "persistent lack of transparency on

investigations and accountability."

(Editing by Paul Tait and Daniel Magnowski)

Targeted civilian

killings spiral in Afghan war: U.N., R, 9.3.2011,

http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/03/09/us-afghanistan-civilians-idUSTRE7224WJ20110309

Putting Afghan Plan Into Action

Proves Difficult

March 8, 2011

The New York Times

By C. J. CHIVERS

ALAM KHEL, Afghanistan — If the American-led fight against the Taliban was

once a contest for influence in well-known and conventionally defined areas —

the capital and large cities, main roads, the border with Pakistan, and a

handful of prominent valleys and towns — today it has become something else.

Slowly, almost imperceptibly, the United States military has settled into a

campaign for scattered villages and bits of terrain that few people beyond their

immediate environs have heard of.

In and near places like this village in Ghazni Province, American units have

pushed their counterinsurgency doctrine and rules for waging war into freshly

contested areas of rural Afghanistan — even as their senior officers have

decided to back out of other remote areas, like the Pech, Korangal and Nuristan

valleys, once deemed priorities. In doing so, American infantry units have

expanded a military footprint over lightly populated terrain from the Helmand

and Arghandab River basins to the borders of the former Soviet Union, where the

Taliban had been weak.

Depending on point of view, this shift — which resulted from both the current

military leadership’s reconsideration of past commanders’ decisions and the

troop buildup ordered by President Obama — is either an operational achievement

or grounds for exasperation, even confusion.

On a morning a few weeks ago, helicopters touched down before dawn on a hard,

frozen field beside this village. American and Afghan soldiers ran out and

clustered against mud walls, where they shivered until beginning their searches

at sunrise.

For hours, the young men entered homes, separating local men from local women,

seeking signs of those who plant bombs and ambush government patrols. They found

little beyond a staple of Afghan counterguerrilla war: a procession of men who

said they knew nothing of the Taliban.

One ritualized exchange summarized the encounters. The soldiers questioned a man

who had seemed to signal their movements by repeatedly honking a minivan horn.

His right hand bore a tattoo of crossed swords.

Asked by the American platoon commander, First Lt. Philip Divinski, what the

tattoo signified, the man said he didn’t know. “My mother put it there,” he

said. He added, “When I was 2.”

The lieutenant gave a sigh.

Episodes like this, duplicated countless times on patrols in places where more

American forces have fanned out, underscore an institutionalized frustration in

a war in its second decade. They capture the latest change in how the Pentagon’s

counterinsurgency campaign feels on the ground — in a new list of villages

designated “key terrain,” the old search for Afghan needles in Afghan haystacks

grinds on.

Officially, Mr. Obama’s Afghan buildup shows signs of success, demonstrating

both American military capabilities and the revival of a campaign that had been

neglected for years. But in the rank and file, there has been little

triumphalism as the administration’s plan has crested.

With the spring thaw approaching, officers and enlisted troops alike say they

anticipate another bloody year. And as so-called surge units complete their

tours, to be replaced by fresh battalions, many soldiers, now seasoned with

Afghan experience, express doubts about the prospects of the larger campaign.

The United States military has the manpower and, thus far, the money to occupy

the ground that its commanders order it to hold. But common questions in the

field include these: Now what? How does the Pentagon translate presence into

lasting success?

The answers reveal uncertainty. “You can keep trying all different kinds of

tactics,” said one American colonel outside of this province. “We know how to do

that. But if the strategic level isn’t working, you do end up wondering: How

much does it matter? And how does this end?”

The strategic vision, roughly, is that American units are trying to diminish the

Taliban’s sway over important areas while expanding and coaching Afghan

government forces, to which these areas will be turned over in time.

But the colonel, a commander who asked that his name be withheld to protect him

from retaliation, referred to “the great disconnect,” the gulf between the

intense efforts of American small units at the tactical level and larger

strategic trends.

The Taliban and the groups it collaborates with remain deeply rooted; the Afghan

military and police remain lackluster and given to widespread drug use; the

country’s borders remain porous; Kabul Bank, which processes government

salaries, is wormy with fraud, and President Hamid Karzai’s government, by

almost all accounts, remains weak, corrupt and erratically led.

And the Pakistani frontier remains a Taliban safe haven.

Even a successful military campaign, soldiers and Marines consistently say, is

unlikely to untangle this knot of dysfunction, much less within the deadlines

discussed in Washington. The Obama administration hopes to begin withdrawing

forces within months and to complete a drawdown by 2014 (a plan reiterated by

Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates in Afghanistan this week).

“This is tough,” one company commander, Capt. Edward T. Peskie, said of the

problems. “And it’s more complex than I think most people realize.”

And if the American presence is decreased, the troops often say, to whom is the

country’s security to be entrusted?

An awareness of the disconnect should not be confused with pessimism, at least

not outwardly expressed. A can-do pragmatism and a quick operational tempo are

apparent in many infantry units, even if the work is overlaid with nagging

questions.

Another commander, Lt. Col. Alan Streeter, leads a reinforced infantry battalion

newly arrived in Ghazni Province for a one-year tour. “I think this place is far

from secure,” he said of the Andar and Deh Yak districts, where his unit, Second

Battalion, Second Infantry, is assigned. “But I think it is a hell of a lot

better than it was.”

With cold weather lingering, he planned to have soldiers meet local Afghans

while they can — before temperatures climb and vegetation rises, making

conditions better for the Taliban to stage attacks. “I want to take this chance

to get out, to talk to the people,” he said. “Because in the spring we may be

too busy fighting.”

Such determination is evident in many conversations. But in some ways, the

mission of Colonel Streeter’s battalion frames another difficulty with the

Pentagon’s puzzle: the math. His reinforced battalion, about 1,000 soldiers, is

assigned to secure territory with an estimated 150,000 people. And he was

explicit: these districts are far from secure.

Afghanistan has nearly 30 million people. How can an American force of roughly

100,000 secure them all? The question tends to bring perplexed looks, or even

grimaces, meaning — politely and carefully — take that question upstairs.

Again, the generals have an answer. The Afghan military and police are growing,

and in a few years could be roughly three times the size of the NATO forces,

they say.

But the escalating numerical projections, which have grown each year as the

United States has deepened its involvement in the war, have yet to undo these

forces’ reputation for poor initiative, corruption, marginal skills and an

enduring dependency on foreign supervision for everything from resupply and fire

support to actions that should be routine, like standing post.

Many American officers, year in and year out, describe a persistent trait

visible to anyone who visits almost any line unit for an extended time. Afghan

units are supposed to be preparing to take over security. Yet they are often

unwilling to set out on independent patrols, beyond trips back and forth between

their own positions, or to the bazaar. They remain largely a tag-along force.

And so, firefight by firefight, bomb by bomb, many of the troops whose lives are

at risk openly discuss how gains feel tentative, perhaps temporary.

Their generals have designated scores of rural areas “key terrain districts.”

The soldiers are creating, at cost of money and blood, pockets of security.

But when Americans arrive in a new area, attacks and improvised bombs typically

follow — making roads and trails more dangerous for the civilians whom, under

current Pentagon counterinsurgency doctrine, the soldiers have arrived to

protect.

And in some cases, the old priorities — like the fight for the Pech Valley — are

later deemed unnecessary, even as the latest effort carves out ground.

“We create little security bubbles,” said Sgt. First Class Paul Meacham, a

platoon leader in Third Battalion, 187th Infantry, which swept Alam Khel, after

one of his last patrols before rotating back to the States last month. “But they

are little bubbles that are easy to attack and infiltrate.”

After a moment of reflection, he said: “I think it could work. But it’s going to

be a long time.”

Asked how long, his answer was immediate. “These people,” he said, nodding

toward the villages nearby, “think in decades.”

Putting Afghan Plan Into

Action Proves Difficult, NYT, 8.3.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/09/world/asia/09ghazni.html

Petraeus Sees Military Progress

in Afghanistan

March 8, 2011

The New York Times

By CARLOTTA GALL

KABUL, Afghanistan — Besides well-reported advances in southern provinces,

American and NATO forces have also been able to halt or reverse Taliban gains

around the capital, Kabul, and even in the north and west of the country, Gen.

David H. Petraeus, the top American commander in Afghanistan, said Tuesday.

The general made his case for an improving overall picture in Afghanistan in an

interview, offering a preview of what is likely to be his argument next week

when he testifies before Congress for the first time since he took over command

of coalition forces in Afghanistan eight months ago.

It will also be his first testimony since the influx of additional American and

Afghan troops began to change the balance of the fighting in southern

Afghanistan in late 2010.

Under General Petraeus, the tempo of operations has been stepped up enormously.

American Special Operations forces and coalition commandos have mounted more

than 1,600 missions in the 90 days before March 4 — an average of 18 a night —

and the troops have captured and killed close to 3,000 insurgents, according to

information provided by the general.

“The momentum of the Taliban has been halted in much of the country and reversed

in some important areas,” he said.

“The Taliban have never been under the pressure that they were put under over

the course of the last 8 to 10 months,” he added.

Other aspects of the war remain difficult, and progress is patchy and slow,

General Petraeus conceded. There has been only modest momentum on efforts to

persuade Taliban fighters to give up the fight and join a reintegration program,

and a plan to train and install thousands of local police officers in rural

communities to mobilize resistance to the Taliban has proved to be a painstaking

business constrained by concerns that it will create militias loyal to warlords.

But security in and around Kabul has significantly improved, he said, thanks in

part to specialized commando units of the Afghan Army, the police and the

intelligence service, which operate in the greater Kabul area.

In 2009, Kabul was encircled by Taliban forces and there was talk of the

capital’s falling to the insurgents, but now much of the greater Kabul area has

been secured, he said.

President Hamid Karzai is to announce on the Afghan New Year, March 21, the

beginning of the transition to Afghan control of some districts around the

country, part of the plan to pass responsibility for security to the Afghan

government by 2014.

The Taliban are expected to try to retake lost territory in coming months, and

in particular to single out those districts in transition, the general said. But

he said coalition forces would mount their own spring offensive to pre-empt

Taliban efforts to retake lost territory.

“You cannot eliminate all the sensationalist attacks,” he said. “That is one of

the objectives for our spring offensive — to solidify those gains and push them

back further.”

Over the past four months, coalition forces have seen a fourfold increase in the

number of weapons and explosives caches found and cleared, in large measure

because the Taliban were forced out of territory they had held for up to five

years, he said.

“The Taliban had to leave hastily, and the fighters and leaders were killed,

captured or run off, and if they were run off they could not cart off all the

I.E.D. and weapons and explosives that they had established over five years in

some cases,” the general said, referring to improvised explosive devices.

Troops were finding more than 120 explosives and weapons caches a month recently

compared with 40 a month a year ago, according to information from the

International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan provided by the general.

Destroying the infrastructure the Taliban had built up over the years, including

field hospitals, weapons stores, bomb-making factories, safe houses and even

detention facilities, would make it harder for them to regain the territory, he

said. “Not having those will make their job more difficult this spring,” he

said.

Many of the Taliban leaders and fighters had escaped to sanctuaries in Pakistan,

he said, and coalition forces would focus in coming months on a strategy called

“defense and depth,” blocking their return through strategic border regions that

the insurgents traditionally used, namely in southern Helmand, eastern Kandahar

and eastern Nangarhar Provinces, where Afghanistan borders Pakistan, and

preventing them from regaining control of their old havens in Afghanistan.

As Afghanistan braces for an increase in fighting that traditionally occurs in

the spring, however, tensions over civilian casualties have flared again, after

an episode in eastern Afghanistan last week when American helicopter gunners

killed nine boys collecting firewood.

A time lag between the sighting of a group of insurgents by ground forces and

the relay of the information to a helicopter attack team led to the deaths, the

general said, citing a preliminary inquiry. The attack team believed that the

group of boys was the group of insurgents, he said.

“They thought they saw the same group but did not, and there was a gap in time

before the final positive identification from the ground force until the handoff

to the weapons team,” he said. “Beyond a human tragedy, it was a terrible and

tragic mistake.”

That episode on March 1 came soon after a more controversial attack in the same

region that the Afghan government said killed 65 civilians on Feb. 17. Mr.

Karzai rejected General Petraeus’s earlier explanation that the victims were

Taliban fighters, and he refused to accept his apology on Sunday for the deaths

of the nine boys.

President Obama and Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates have also apologized to

Mr. Karzai and the Afghan people for the deaths.

“This kind of event does clearly undermine the trust between the Afghan

government and ISAF, and more important, between the Afghan people and ISAF,”

General Petraeus conceded. The full investigation was nearly complete, he said,

and a review had been ordered of the tactical directive given to troops. He

declined comment on the Feb. 17 episode.

Despite the flare-up, relations with President Karzai were good, the general

insisted. The two meet several times a week, including for one-on-one meetings.

“We have open and forthright conversations with one another,” he said.

Over all, he noted, civilian casualties caused by Afghan and coalition forces

had declined in 2010 by about 20 percent from the previous year, which he said

was “impressive” given the deployment of 100,000 more Afghan and coalition

troops and the increase in operations in 2010.

A United Nations report on civilian casualties in Afghanistan to be released

Wednesday would show the majority — 75 percent — of civilian casualties in 2010

were caused by Taliban and insurgent attacks, he said.

Petraeus Sees Military

Progress in Afghanistan, NYT, 8.3.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/09/world/asia/09petraeus.html

Gates Says U.S. Positioned

to Take Some Troops

Out of

Afghanistan

March 7, 2011

The New York Times

By ELISABETH BUMILLER

KABUL, Afghanistan — Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates said on Monday that

the United States is now “well-positioned” to begin withdrawing some American

troops from Afghanistan in July, but he said a substantial force would remain

and that the United States was starting talks with the Afghans about keeping a

security presence in the country beyond 2014.

At a joint news conference in the Afghan capital with President Hamid Karzai,

Mr. Gates said that no decisions had been made about the number of troops to go

home. His remarks were tempered with enough caveats, however, to suggest that

the July drawdown, a promise of President Obama, could be minor. “As I have said

time and again, we are not leaving Afghanistan this summer,” Mr. Gates said.

Currently there are some 100,000 American forces in the country.

Mr. Gates also used the news conference to offer an extended apology to Mr.

Karzai about the mistaken killings last week of nine Afghan boys, which Mr.

Karzai accepted. On Sunday Mr. Karzai had rejected an apology about the killings

from Gen. David H. Petraeus, the top American commander in Afghanistan.

“This breaks our heart,” Mr. Gates said as he stood beside Mr. Karzai in the

Afghan presidential palace. “Not only is their loss a tragedy for their

families, it is a setback for our relationship with the Afghan people.”

One boy who was wounded but survived the incident described a helicopter gunship

that hunted down the children as they gathered wood on the mountainside outside

their village. The gunners apparently mistook the children for insurgents who

hours earlier had fired on an American base. The boys were from 9 to 15 years

old.

Mr. Karzai, after responding that civilian casualties were at the heart of the

tensions between the United States and Afghanistan, said of Mr. Gates that “I

trust him fully when he says he’s sorry.”

Mr. Gates, who is on an unannounced two-day trip to Afghanistan, spoke more

positively than he has in recent months about what he cited as progress in the

nearly decade-old war. “The gains we are seeing across the country are

significant,” he said, citing improvements in security in Helmand and Kandahar

Provinces in the south as well as some progress on Afghanistan’s eastern border

with Pakistan.

Mr. Gates made similar remarks to American troops at Bagram Air Base earlier in

the day, when he told them that “you’re having success, there’s just no question

about it.” He added, “I know you’ve had a tough winter, it’s going to be a

tougher spring and summer, but you’ve made a lot of headway, and I think you’ve

proven with your Afghan partners that this thing is going to work.”

Despite the optimism in Mr. Gates’s remarks, American commanders in the east and

north have seen continued violence in 2011 and two of the most lethal suicide

bomb attacks in nearly two years occurred in the last four weeks. One in the

eastern city of Jalalabad killed 40 people and another in Kunduz Province in the

north killed 32.

And on Monday a bomb blast in Jalalabad killed another two people and injured

19.

Although fewer American troops are dying this year than last, commanders say it

is hard to tell whether that is due to a weakening in the Taliban offensive or

the traditional winter hiatus in fighting. But if Afghan troops prove able to

keep the violence under control, that could signal a growing ability to protect

difficult patches on their own. Training Afghan troops well enough to defend

their own country is the long-term goal of the United States and Mr. Obama’s

strategy for ending the war.

Maj. Gen. John F. Campbell, the top American commander in eastern Afghanistan,

told reporters traveling with Mr. Gates that violence in his region on the

border with Pakistan was up from a year ago and that it had also increased in

the last 30 days. “I think the enemy is trying to get an early start on what

they call their spring campaign,” General Campbell said.

In recent weeks American forces have withdrawn from remote parts of the Pech

Valley, which is part of General Campbell’s battle space, in order to

concentrate more forces in the border area. General Campbell refused to call the

thinning of forces in the valley, once deemed vital to American interests, a

retreat, although the fighting there had dragged on for years with no clear

result.

“When somebody says you’ve abandoned the Pech, that’s absolutely false,” General

Campbell said.

Despite the rise in violence in the east, General Campbell said the attacks by

insurgents were less effective than a year ago. His office produced statistics

stating that American and coalition forces had killed 2,448 insurgents in his

region between June 2010 and February 2011 and had captured 2,870 in the same

time period.

As far as an American military presence in Afghanistan beyond 2014, Mr. Gates

said that an American team would be in Kabul next week to begin negotiations on

what he called a security partnership, which he predicted would be a “small

fraction” of the American forces in Afghanistan today. “We have no interest in

permanent bases, but if the Afghans want us here, we are certainly prepared to

contemplate that,” Mr. Gates said.

From Afghanistan, Mr. Gates is to fly to Stuttgart, Germany, the headquarters of

United States Africa Command, where he will preside over a ceremony observing

General Carter Ham’s ascension as commander of Africa Command, which has Libya

in its area of responsibility.

After that, Mr. Gates will attend a meeting of NATO defense ministers in

Brussels, where the civil war in Libya and American troop withdrawals in

Afghanistan will be discussed.

Alissa J. Rubin contributed reporting

Gates Says U.S.

Positioned to Take Some Troops Out of Afghanistan, NYT, 7.3.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/08/world/asia/08gates.html

U.S. apology for Afghan deaths

"not enough": Karzai

KABUL | Sun Mar 6, 2011

10:50am EST

Reuters

By Hamid Shalizi and Jonathon Burch

KABUL (Reuters) - Afghan President Hamid Karzai told General David Petraeus,

the commander of U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan, on Sunday his apology for

a foreign air strike that killed nine children last week was "not enough."

At a meeting with his security advisers at which Petraeus was present, Karzai

said civilian casualties by foreign troops were "no longer acceptable" to the

Afghan government or to the Afghan people, Karzai's palace said in a statement.

Civilian casualties caused by NATO-led and Afghan forces hunting insurgents have

again become a major source of friction between Karzai and his Western backers.

In the meeting, Petraeus apologized for the deaths of the nine children in

eastern Kunar province last Tuesday, saying the killings were a "great mistake"

and there would be no repeat.

"In return, the president said the apology was not enough and stressed that

civilian casualties caused during operations by coalition forces were the main

cause of strained relations between the United States and Afghanistan," the

palace said.

"The people of Afghanistan are fed up with such horrific incidents and apologies

or condemnation is not going to heal their wounds," it quoted Karzai as saying.

Hours before Karzai's statement, hundreds of people chanting "Death to America"

protested in the Afghan capital against the recent spate of civilian deaths, in

a sign of the simmering anti-Western feeling among many ordinary Afghans.

International concern over civilian casualties has grown, and the fallout from

the recent incidents is even threatening to hamper peace and reconciliation

efforts, with a gradual drawdown of the 150,000 foreign troops in Afghanistan to

begin in July.

"DEEP REGRET"

Last Tuesday, two attack helicopters gunned down nine Afghan boys as they

collected firewood in Kunar after a nearby foreign base had come under insurgent

attack.

The incident, in a volatile area that has seen a recent spike in foreign

military operations, prompted rare public apologies from Petraeus and his

deputy.

President Barack Obama also expressed "deep regret" over the killings and the

United Nations called for a review of air strikes.

There have been at least four incidents of civilian casualties by foreign troops

in the east in the past two weeks in which Afghan officials say more than 80

people died.

Demonstrators marched through the center of Kabul, some carrying banners bearing

pictures of blood-covered dead children they said were killed in air strikes by

foreign forces.

"We will never forgive the blood shed by our innocent Afghans who were killed by

NATO forces," said one protester Ahmad Baseer, a university student.

"The Kunar incident is not the first and it will not be the last time civilian

casualties are caused by foreign troops."

Dozens of women were also among the protesters, a rare occurrence in a country

where women are largely banned from public life. Using loudspeakers, some of the

women chanted: "We don't want Americans, we don't want the Taliban, we want

peace."

PROTESTERS BLAME BOTH SIDES

U.S. and NATO commanders have tightened procedures for using air strikes in

recent years, but mistaken killings of innocent Afghans still happen, especially

with U.S. and NATO forces stepping up operations in the past few months.

Although civilian casualties caused by foreign forces have decreased over the

past two years -- mainly due to a fall in air strikes -- aid groups last

November warned a recent rise in the use of air power risked reversing those

gains.

Civilian casualties in Afghanistan rose 20 percent in the first 10 months of

2010 compared with 2009, according to U.N. figures, with insurgents responsible

for more than three-quarters of those killed or wounded.

In the latest attack by insurgents, 12 civilians were killed on Sunday when

their vehicle was hit by a roadside bomb in southeastern Paktika province,

governor Mohebullah Sameem said.

But while insurgents are responsible for the large majority of civilian deaths,

it is those by foreign forces which rile Afghans most. Many Afghans say militant

attacks would not happen if international troops were not in Afghanistan.

"Killing civilians, whether it is the Taliban or foreign forces, is a crime,"

said protester Shahla Noori.

"Both the Taliban and Americans are responsible for the killings of thousands of

civilians," she said.

(Additional reporting by Matt Robinson in Kabul and Elyas Wahdat in Khost;

Writing by Jonathon Burch; Editing by Elizabeth Fullerton)

U.S. apology for Afghan

deaths "not enough": Karzai, R, 6.3.2011,

http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/03/06/us-afghanistan-civilians-idUSTRE7224WJ20110306

NATO Apologizes

for Killing 9 Afghan Civilians

March 2, 2011

Filed at 8:14 a.m. EST

The New York Times

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

KABUL, Afghanistan (AP) — NATO has apologized for killing nine civilians in

Kunar province, a hotbed of the insurgency in northeast Afghanistan.

In a statement Wednesday, the coalition said preliminary findings indicate that

NATO forces accidentally killed nine civilians in the Pech district of Kunar

province on Tuesday. Local officials say nine boys, ages 12 and under, were

killed as they were gathering firewood.

The coalition says there apparently was miscommunication in passing information

about the location of militants firing on a coalition base.

Top NATO commander Gen. David Petraeus said the coalition was "deeply sorry" for

the tragedy and said the deaths should never have occurred. Petraeus says he

will personally apologize to President Hamid Karzai when he returns from London.

THIS IS A BREAKING NEWS UPDATE. Check back soon for further information. AP's

earlier story is below.

KABUL, Afghanistan (AP) — Several hundred villagers protested Wednesday against

coalition strikes that they claim killed scores of civilians, including nine

boys, in a hotbed of the insurgency in the northeast. NATO has contested the

claims, saying armed insurgents, not civilians, were killed.

Civilian casualties have long been a source of friction between Afghan President

Hamid Karzai and the U.S.-led international force fighting in Afghanistan.

Karzai's office issued a statement condemning the NATO strike.

"Innocent children who were collecting fire wood for their families during this

cold winter were killed. Is this the way to fight terrorism and maintain

stability in Afghanistan?" Karzai asked in the statement. He said NATO should

focus more on "terrorist sanctuaries" — a phrase he typically uses when

referring to Taliban refuges in neighboring Pakistan.

Noorullah Noori, a member of the local development council in Manogai district,

said four of the nine boys killed were age 7, three were age 8, one was nine

years old and one was 12. Also, one child was wounded, he said.

He said the children were gathering wood under a tree in the mountains on

Tuesday about a half kilometer from a village in Manogai district.

"I myself was involved in the burial," he said. "Yesterday we buried them at 5

p.m."

He said that during the four-hour demonstration, protesters chanted "Death to

America" and "Death to the spies," a reference to what they said was bad

intelligence given to helicopter weapons teams.

The coalition said it was investigating the villagers' allegations. NATO said

coalition forces returned fire after two rockets were fired at a coalition base,

slightly wounding a local contractor.

Late last month, tribal elders in Kunar claimed that NATO forces killed more

than 50 civilians in air and ground strikes. The international coalition denied

that claim, saying video showed troops targeting and killing dozens of

insurgents and a subsequent investigation yielded no evidence that civilians had

been killed. An Afghan government investigation has said that 65 civilians were

killed.

In Logar province on Tuesday, four Afghan soldiers and their interpreter were

killed by a roadside bomb, according to Din Mohammad Darwesh, a spokesman for

the province. He said Wednesday that the soldiers were on a joint patrol with

U.S. forces when their vehicle hit the bomb planted in Charkh district.

NATO Apologizes for

Killing 9 Afghan Civilians, NYT, 2.3.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2011/03/02/world/asia/AP-AS-Afghanistan.html

Taliban Bet on Fear

Over Brawn as Tactic

February 26, 2011

The New York Times

By ALISSA J. RUBIN

KABUL, Afghanistan — This year the spring offensive by the Taliban and other

insurgent groups has a new and terrifying face: the insurgents are using suicide

bombers who create high casualties to sow terror and are planning an

assassination campaign as well, Afghan and American military analysts say.

The insurgents’ deadly bet is that fear will trump anger and that Afghans will

lose any faith they had in their government’s security forces and eventually

turn to the Taliban.

“You have to ask yourself, ‘If you were the Taliban now, what would you do?’ ”

said Gen. Jack Keane, who retired from the Army in 2003 and is now a consultant

to Gen. David H. Petraeus, the NATO commander for Afghanistan.

Given the massing of NATO forces in the south, the answer appears to be attack

the urban, civilian population, creating widespread insecurity in an effort to

reinforce the existing resentment of foreign troops and doubts about President

Hamid Karzai’s government.

In less than four weeks, 116 Afghans have died in seven suicide attacks, most

recently in Faryab Province on Saturday. Two of the attacks, one in Jalalabad on

Feb. 19 and another in Kandahar on Feb. 12, involved multiple assailants and

were carefully choreographed and skillfully timed to obtain a high death toll

and maximum media coverage. In at least one case, the mission was carefully

rehearsed.

This is a striking change from Afghan suicide bombings of just six months ago,

in which the bombers exacted few casualties.

These new tactics highlight the challenge of an adaptive insurgency with a

reservoir of potential fighters, many of them madrasa students in Pakistan’s

tribal areas. They show too the increasingly integrated network of insurgent

groups that lend their expertise to one another as well as the difficulties the

Afghan government has had in rallying its own people to fight them.

President Karzai has compounded the problem, some Afghan analysts say, by

insisting that the Taliban are not to blame for the violence and that they are

“upset brothers” rather than mortal enemies.

Underlying the latest attacks are the region’s geopolitics. Both Pakistan and

Iran are known to be supporting the Taliban and play out their antagonism to the

United States on Afghan soil. “You have to see these attacks in the broader

strategic context,” said Haseeb Humayoon, the director of a risk consulting firm

here.

A period of relative calm last year in Afghan cities coincided with an easing of

tensions between the Afghans and Pakistan over negotiations with the Taliban.

Now the Afghans appear to be trying to negotiate with the Taliban on their own,

and there is talk of permanent American bases here, which Pakistan and Iran see

as a potential loss of their influence.

“Our neighbors interpret that as Afghans’ seeking guarantors of security other

than them,” Mr. Humayoon said.

“Both the international military and our own government are distracted,” he

added. “Our government is not focusing enough on rallying people against these

forces, and the international military coalition has not focused enough on

Pakistan.”

American commanders play down the significance of the attacks in terms of the

overall fight in Afghanistan, but Afghan security officials say they see a

troubling and potentially crippling development. “It’s not that the American

surge operations will be affected by this directly,” said a former Afghan

security official. Rather, he predicted that the suicide attacks could preoccupy

Afghan security leaders, diminishing their ability to contribute to the fight in

the south.

The Americans had not expected the suicide bombings on this scale but were

bracing for assassination attempts this spring against officials, said Rear Adm.

Gregory J. Smith, NATO’s chief of strategic communications.

The Taliban in the past have been careful not to single out civilians, although

civilians are often killed in attacks. At least some Taliban factions seem

worried about the latest tactics. Zabiullah Mujahid, the Taliban spokesman for

the north and east of the country, said an investigation was under way into the

Jalalabad attack, which killed 40 people, nearly half of them civilians.

“We are taking this issue seriously as we have appointed a delegate to assess

the civilians casualties,” he said. “We are not happy when there is even one

civilian lost.”

Despite such statements, attacks on civilians are clearly on the rise and the

sophistication of the suicide bombings has been striking, Admiral Smith said.

American and Afghan officials now believe that Lashkar-e-Taiba, the group that

planned the attacks in Mumbai, India, in 2008, has been working with the Haqqani

network, which is based in North Waziristan. Lashkar-e-Taiba specializes in

planning complex suicide attacks.

“The suicide bombings are, we believe, predominantly requested and funded by

Haqqani but facilitated by LET and AQ,” said a senior American military

official, referring to Lashkar-e-Taiba and Al Qaeda. “The latter groups provide

bombers and material in exchange for money. Haqqani chooses targets.”

The bombing of the Kabul Bank branch in Jalalabad used a formula Lashkar-e-Taiba

has used elsewhere: multiple attackers, a first bomber to clear the way for the

others and the holding of one bomber in reserve to attack the police and medical

workers who arrive to help. Other signatures included having a suicide bomber on

a cellphone with a handler, as was the case in the Mumbai attacks.

What cannot be ignored, however, is the situation across the border in Pakistan.

While American troops have made clear gains in uprooting the Taliban from

Kandahar and large areas of Helmand Province, Pakistan has not made similar

strides in ousting the Taliban from the tribal areas, according to analysts

here. The Haqqani network, among the most brutal, remains anchored in North

Waziristan despite a stream of drone strikes by the Central Intelligence Agency.

And in bad news for Afghanistan, a little-noticed peace deal took place late

last year between the Haqqani network and Shiite tribes in the Kurram Agency in

Pakistan, which opened up a new route for Haqqani agents to enter Afghanistan,

American and Afghan intelligence officials said. A number of fighters have been

observed crossing the border over the past several weeks, American intelligence

officials said.

No one yet seems to have figured out how to deal with the two largest underlying

problems: the poor performance of the Afghan government, which makes many of the

country’s citizens reluctant to fight for it, and the millions of Pashtuns in

the tribal areas who feel they are unrepresented and even discriminated against

and are willing to cross the border to fight in Afghanistan.

“You still have two major factors,” General Keane said, “the ineffectiveness of

the central government and the Pakistani sanctuaries.”

The situation is strikingly reminiscent of Iraq in 2005, when that country’s

cities were gripped by violence, the government was unable to keep the people

safe and fighters flowed in from other countries. It took four years to stem

that violence, and an influx of troops like the one that Americans have now

carried out in Afghanistan. The rash of recent bombings risks undermining the

psychological advantage that had come with increased American troop strength in

southern Afghanistan.

Eric Schmitt contributed reporting from Washington.

Taliban Bet on Fear Over

Brawn as Tactic, NYT, 26.2.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/27/world/asia/27afghanistan.html

Warning Against Wars

Like Iraq and Afghanistan

February 25, 2011

The New York Times

By THOM SHANKER

WEST POINT, N.Y. — Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates bluntly told an audience

of West Point cadets on Friday that it would be unwise for the United States to

ever fight another war like Iraq or Afghanistan, and that the chances of

carrying out a change of government in that fashion again were slim.

“In my opinion, any future defense secretary who advises the president to again

send a big American land army into Asia or into the Middle East or Africa should

‘have his head examined,’ as General MacArthur so delicately put it,” Mr. Gates

told an assembly of Army cadets here.

That reality, he said, meant that the Army would have to reshape its budget,

since potential conflicts in places like Asia or the Persian Gulf were more

likely to be fought with air and sea power, rather than with conventional ground

forces.

“As the prospects for another head-on clash of large mechanized land armies seem

less likely, the Army will be increasingly challenged to justify the number,

size, and cost of its heavy formations,” Mr. Gates warned.

“The odds of repeating another Afghanistan or Iraq — invading, pacifying, and

administering a large third-world country — may be low,” Mr. Gates said, but the

Army and the rest of the government must focus on capabilities that can “prevent

festering problems from growing into full-blown crises which require costly —

and controversial — large-scale American military intervention.”

Mr. Gates was brought into the Bush cabinet in late 2006 to repair the war

effort in Iraq that was begun under his predecessor, Donald H. Rumsfeld, and

then was kept in office by President Obama. He did not directly criticize the

Bush administration’s decisions to go to war. Even so, his never-again

formulation was unusually pointed, especially at a time of upheaval across the

Arab world and beyond. Mr. Gates has said that he would leave office this year,

and the speech at West Point could be heard as his farewell to the Army.

A decade of constant conflict has trained a junior officer corps with

exceptional leadership skills, he told the cadets, but the Army may find it

difficult in the future to find inspiring work to retain its rising commanders

as it fights for the money to keep large, heavy combat units in the field.

“Men and women in the prime of their professional lives, who may have been

responsible for the lives of scores or hundreds of troops, or millions of

dollars in assistance, or engaging or reconciling warring tribes, may find

themselves in a cube all day re-formatting PowerPoint slides, preparing

quarterly training briefs, or assigned an ever-expanding array of clerical

duties,” Mr. Gates said. “The consequences of this terrify me.”

He said Iraq and Afghanistan had become known as “the captains’ wars” because

“officers of lower and lower rank were put in the position of making decisions

of higher and higher degrees of consequence and complexity.”

To find inspiring work for its young officers after combat deployments, the Army

must encourage unusual career detours, Mr. Gates said, endorsing graduate study,

teaching, or duty in a policy research institute or Congressional office.

Mr. Gates said his main worry was that the Army might not overcome the

institutional bias that favored traditional career paths. He urged the service

to “break up the institutional concrete, its bureaucratic rigidity in its

assignments and promotion processes, in order to retain, challenge, and inspire

its best, brightest, and most battle-tested young officers to lead the service

in the future.”

There will be one specific benefit to the fighting force as the pressures of

deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan decrease, Mr. Gates said: “The opportunity

to conduct the kind of full-spectrum training — including mechanized combined

arms exercises — that was neglected to meet the demands of the current wars.”

Warning Against Wars

Like Iraq and Afghanistan, NYT, 25.2.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/26/world/26gates.html

The Next Impasse

February 24, 2011

The New York Times

By DEXTER FILKINS

THE WRONG WAR

Grit, Strategy, and the Way Out of Afghanistan

By Bing West

Illustrated. 307 pp. Random House. $28.

In the nine years since the first American troops landed in Afghanistan, a

new kind of religion has sprung up, one that promises success for the Americans

even as the war they have been fighting has veered dangerously close to defeat.

Follow the religion’s tenets, give yourself over to it and the new faith will

reward you with riches and fruits.

The new religion, of course, is counterinsurgency, or in the military’s jargon,

COIN. The doctrine of counterinsurgency upends the military’s most basic notion

of itself, as a group of warriors whose main task is to destroy its enemies.

Under COIN, victory will be achieved first and foremost by protecting the local

population and thereby rendering the insurgents irrelevant. Killing is a

secondary pursuit. The main business of American soldiers is now building

economies and political systems. Kill if you must, but only if you must.

The showcase for COIN came in Iraq, where after years of trying to kill and

capture their way to victory, the Americans finally turned the tide by

befriending the locals and striking peace deals with a vast array of insurgents.

In 2007 and 2008, violence dropped dramatically. The relative stability in Iraq

has allowed Americans to come home. As a result, counterinsurgency has become

the American military’s new creed, the antidote not just in Iraq but Afghanistan

too. At the military’s urging, President Obama has become a convert, ordering

thousands of extra young men and women to that country, in the hopes of saving

an endeavor that was beginning to look doomed. No one in the Obama

administration uses the phrase “nation-building,” but that is, of course,

precisely what they are trying to do — or some lesser version of it. Protect the

Afghan people, build schools and hold elections. And the insurgents will wither

away.

So what’s wrong? Why hasn’t the new faith in Afghanistan delivered the success

it promises? In his remarkable book, “The Wrong War,” Bing West goes a long way

to answering that question. “The Wrong War” amounts to a crushing and seemingly

irrefutable critique of the American plan in Afghanistan. It should be read by

anyone who wants to understand why the war there is so hard.

The strength of West’s book is the legwork he’s done. Most accounts of America’s

wars, particularly those by former military officers, are written in the comfort

of an office in the United States. Not so here. At age 70, West, the author of

several books on America’s wars, went to Afghanistan and into the bases and out

on patrols with the grunts, waded through the canals, ran through firefights and

humped up the mountains. (At one point he contracted cholera and was evacuated

by helicopter.) Embedding with American troops in God-forsaken places like Kunar

and Helmand Provinces is hard business. What drives this man? West is worth a

book in himself.

But the legwork pays off. West shows in the most granular, detailed way how and

why America’s counterinsurgency in Afghanistan is failing. And, in the places

where the effort is showing promise, he demonstrates why we don’t have the

resources to duplicate that success on a wider scale. Mind you, West is no

antiwar lefty: he’s a former infantry officer who fought in Vietnam. An

assistant secretary of defense in the Reagan administration, he admires — nay,

adores — America’s fighting men and women, and he wants the United States to

succeed. But the facts on the ground, it appears, lead him to darker truths.

West joined American troops in Garmsir, Marja and Nawa in Helmand Province;

Barge Matal in Nuristan; and the Korengal Valley in Kunar — all in the heart of

the fight. His basic argument can be summed up like this: American soldiers and

Marines are very good at counterinsurgency, and they are breaking their hearts,

and losing their lives, doing it so hard. But the central premise of

counterinsurgency doctrine holds that if the Americans sacrifice on behalf of

the Afghan government, then the Afghan people will risk their lives for that

same government in return. They will fight the Taliban, finger the informants

hiding among them and transform themselves into authentic leaders who spurn

death and temptation.

This isn’t happening. What we have created instead, West shows, is a vast

culture of dependency: Americans are fighting and dying, while the Afghans by

and large stand by and do nothing to help them. Afghanistan’s leaders, from the

presidential palace in Kabul to the river valleys in the Pashtun heartland, are

enriching themselves, often criminally, on America’s largesse. The Taliban,