|

History

> 2011 > USA > War >

Iraq (II)

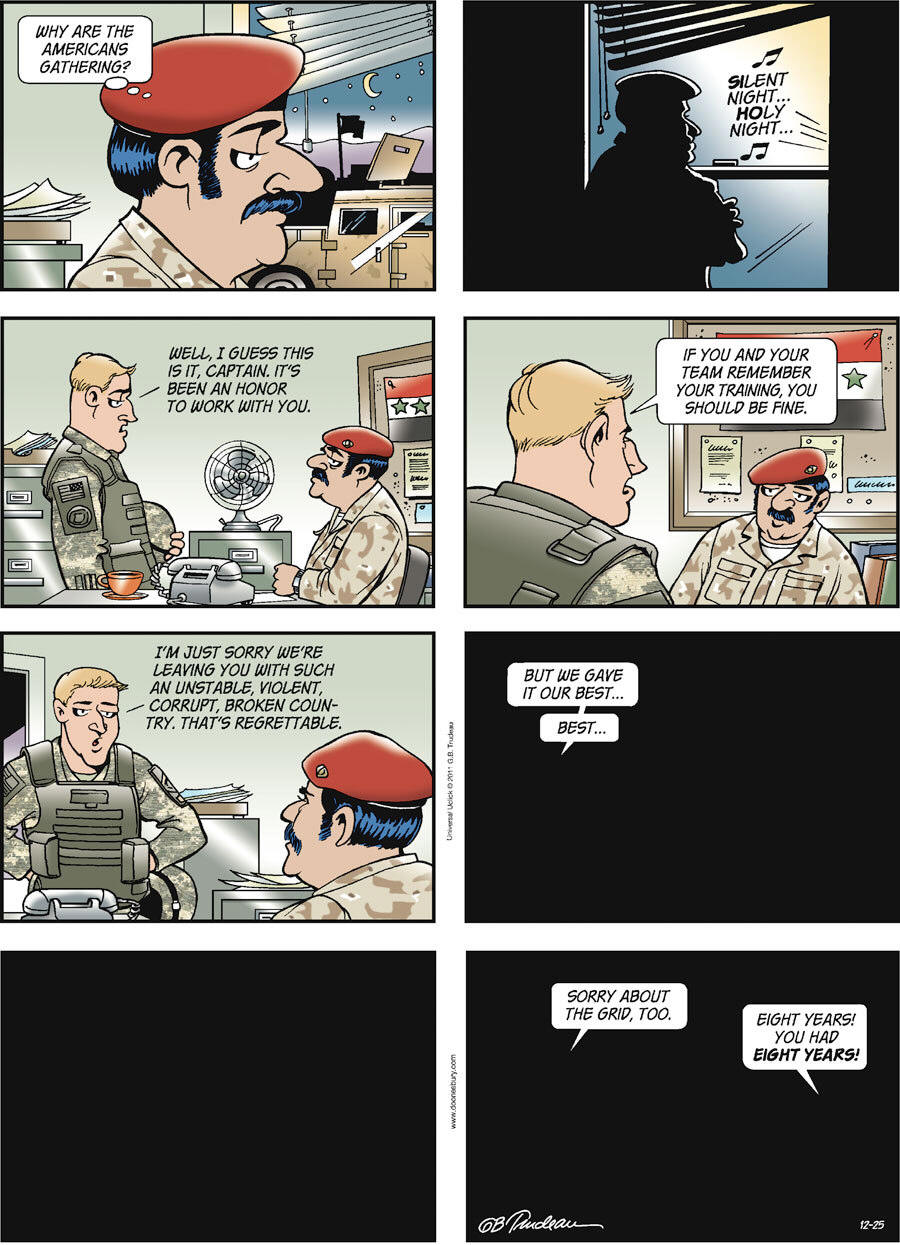

Doonesbury

by Garry Trudeau

GoComics

December 25, 2011

http://www.gocomics.com/doonesbury/2011/12/25

Weapons Sales to Iraq

Move Ahead Despite U.S. Worries

December

28, 2011

The New York Times

By MICHAEL S. SCHMIDT

and ERIC SCHMITT

BAGHDAD —

The Obama administration is moving ahead with the sale of nearly $11 billion

worth of arms and training for the Iraqi military despite concerns that Prime

Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki is seeking to consolidate authority, create a

one-party Shiite-dominated state and abandon the American-backed power-sharing

government.

The military aid, including advanced fighter jets and battle tanks, is meant to

help the Iraqi government protect its borders and rebuild a military that before

the 1991 Persian Gulf war was one of the largest in the world; it was disbanded

in 2003 after the United States invasion.

But the sales of the weapons — some of which have already been delivered — are

moving ahead even though Mr. Maliki has failed to carry out an agreement that

would have limited his ability to marginalize the Sunnis and turn the military

into a sectarian force. While the United States is eager to beef up Iraq’s

military, at least in part as a hedge against Iranian influence, there are also

fears that the move could backfire if the Baghdad government ultimately aligns

more closely with the Shiite theocracy in Tehran than with Washington.

United States diplomats, including Ambassador James F. Jeffrey, have expressed

concern about the military relationship with Iraq. Some have even said it could

have political ramifications for the Obama administration if not properly

managed. There is also growing concern that Mr. Maliki’s apparent efforts to

marginalize the country’s Sunni minority could set off a civil war.

“The optics of this are terrible,” said Kenneth M. Pollack, an expert on

national security issues at the Brookings Institution in Washington and a critic

of the administration’s Iraq policy.

The program to arm the military is being led by the United States Embassy here,

which through its Office of Security Cooperation serves as a broker between the

Iraqi government and defense contractors like Lockheed Martin and Raytheon.

Among the big-ticket items being sold to Iraq are F-16 fighter jets, M1A1 Abrams

main battle tanks, cannons and armored personnel carriers. The Iraqis have also

received body armor, helmets, ammunition trailers and sport utility vehicles,

which critics say can be used by domestic security services to help Mr. Maliki

consolidate power.

“The purpose of these arrangements is to assist the Iraqis’ ability to defend

their sovereignty against foreign security threats,” said Capt. John Kirby, a

Pentagon spokesman in Washington.

But Iraqi politicians and analysts, while acknowledging that the American

military withdrawal had left Iraq’s borders, and airspace, vulnerable, said

there were many reasons for concern.

Despite pronouncements from American and Iraqi officials that the Iraqi military

is a nonsectarian force, they said, it had evolved into a hodgepodge of Shiite

militias more interested in marginalizing the Sunnis than in protecting the

country’s sovereignty. Across the country, they said, Shiite flags — not Iraq’s

national flag — fluttered from tanks and military vehicles, evidence, many said,

of the troops’ sectarian allegiances.

“It is very risky to arm a sectarian army,” said Rafe al-Essawi, the country’s

finance minister and a leading Sunni politician. “It is very risky with all the

sacrifices we’ve made, with all the budget to be spent, with all the support of

America — at the end of the day, the result will be a formal militia army.”

Mr. Essawi said that he was concerned about how the weapons would be used if

political tension led to a renewed tide of sectarian violence. Some Iraqis and

analysts said they believed that the weapons could give Mr. Maliki a significant

advantage in preventing several Sunni provinces from declaring autonomy from the

central government.

“Washington took the decision to build up Iraq as a counterweight to Iran

through close military cooperation and the sale of major weapon systems,” said

Joost Hiltermann, the International Crisis Group’s deputy program director for

the Middle East. “Maliki has shown a troubling inclination toward enhancing his

control over the country’s institutions without accepting any significant checks

and balances.”

Uncertainty over Mr. Maliki’s intentions, and with that the wisdom of the

weapons sale, began to emerge even before the last American combat forces

withdrew 11 days ago. Mr. Maliki moved against his Sunni rivals, arresting

hundreds of former Baath Party members on charges that they were involved in a

coup plot. Then security forces under Mr. Maliki’s control sought to arrest the

country’s Sunni vice president, who fled to the semiautonomous Kurdish region in

the north. In addition, Mr. Maliki threatened to release damning information on

other politicians.

With these actions plunging the country into a political crisis, a few days

later, Mr. Maliki said the country would be turned into “rivers of blood” if the

predominantly Sunni provinces sought more autonomy.

This was not a completely unforeseen turn of events. Over the summer, the

Americans told high-ranking Iraqi officials that the United States did not want

an ongoing military relationship with a country that marginalized its minorities

and ruled by force.

The Americans warned Iraqi officials that if they wanted to continue receiving

military aid, Mr. Maliki had to fulfill an agreement from 2010 that required the

Sunni bloc in Parliament to have a say in who ran the Defense and Interior

Ministries. But despite a pledge to do so, the ministries remain under Mr.

Maliki’s control, angering many Sunnis.

Corruption, too, continues to pervade the security forces. American military

advisers have said that many low- and midlevel command positions in the armed

forces and the police are sold, despite American efforts to emphasize training

and merit, said Anthony Cordesman, an analyst at the Center for Security and

International Studies in Washington.

Pentagon and State Department officials say that weapons sales agreements have

conditions built in to allow American inspectors to monitor how the arms are

used, to ensure that the sales terms are not violated.

“Washington still has considerable leverage in Iraq by freezing or withdrawing

its security assistance packages, issuing travel advisories in more stark terms

that will have a direct impact on direct foreign investment, and reassessing

diplomatic relations and trade agreements,” said Matthew Sherman, a former State

Department official who spent more than three years in Iraq. “Now is the time to

exercise some of that leverage by publicly putting Maliki on notice.”

Lt. Gen. Robert L. Caslen, the head of the American Embassy office that is

selling the weapons, said he was optimistic that Mr. Maliki and the other Iraqi

politicians would work together and that the United States would not end up

selling weapons to an authoritarian government.

“If it was a doomsday scenario, at some point I’m sure there will be plenty of

guidance coming my way,” he said in a recent interview.

A spokesman for the United States Embassy declined to comment, as did the

National Security Council in Washington.

As the American economy continues to sputter, some analysts believe that Mr.

Maliki and the Iraqis may hold the ultimate leverage over the Americans.

“I think he would like to get the weapons from the U.S.,” Mr. Pollack said. “But

he believes that an economically challenged American administration cannot

afford to jeopardize $10 billion worth of jobs.”

If the United States stops the sales, Mr. Pollack said, Mr. Maliki “would simply

get his weapons elsewhere.”

Michael S.

Schmidt reported from Baghdad, and Eric Schmitt from Washington.

Weapons Sales to Iraq Move Ahead Despite U.S. Worries, NYT, 28.12.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/29/world/middleeast/us-military-sales-to-iraq-raise-concerns.html

How to Save Iraq From Civil War

December

27, 2011

The New York Times

By AYAD ALLAWI, OSAMA AL-NUJAIFI

and RAFE AL-ESSAWI

Baghdad

IRAQ today stands on the brink of disaster. President Obama kept his campaign

pledge to end the war here, but it has not ended the way anyone in Washington

wanted. The prize, for which so many American soldiers believed they were

fighting, was a functioning democratic and nonsectarian state. But Iraq is now

moving in the opposite direction — toward a sectarian autocracy that carries

with it the threat of devastating civil war.

Since Iraq’s 2010 election, we have witnessed the subordination of the state to

Prime Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki’s Dawa party, the erosion of judicial

independence, the intimidation of opponents and the dismantling of independent

institutions intended to promote clean elections and combat corruption. All of

this happened during the Arab Spring, while other countries were ousting

dictators in favor of democracy. Iraq had a chance to demonstrate, for the first

time in the modern Middle East, that political power could peacefully pass

between political rivals following proper elections. Instead, it has become a

battleground of sects, in which identity politics have crippled democratic

development.

We are leaders of Iraqiya, the political coalition that won the most seats in

the 2010 election and represents more than a quarter of all Iraqis. We do not

think of ourselves as Sunni or Shiite, but as Iraqis, with a constituency

spanning the entire country. We are now being hounded and threatened by Mr.

Maliki, who is attempting to drive us out of Iraqi political life and create an

authoritarian one-party state.

In the past few weeks, as the American military presence ended, another military

force moved in to fill the void. Our homes and offices in Baghdad’s Green Zone

were surrounded by Mr. Maliki’s security forces. He has laid siege to our party,

and has done so with the blessing of a politicized judiciary and law enforcement

system that have become virtual extensions of his personal office. He has

accused Iraq’s vice president, Tariq al-Hashimi, of terrorism; moved to fire

Deputy Prime Minister Saleh al-Mutlaq; and sought to investigate one of us, Rafe

al-Essawi, for specious links to insurgents — all immediately after Mr. Maliki

returned to Iraq from Washington, wrongly giving Iraqis the impression that he’d

been given carte blanche by the United States to do so.

After Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. urged all parties to maintain a unity

government on Dec. 16, Mr. Maliki threatened to form a government that

completely excluded Iraqiya and other opposition voices. Meanwhile, Mr. Maliki

is welcoming into the political process the Iranian-sponsored Shiite militia

group Asaib Ahl al-Haq, whose leaders kidnapped and killed five American

soldiers and murdered four British hostages in 2007.

It did not have to happen this way. The Iraqi people emerged from the bloody and

painful transition after the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime hoping for a

brighter future. After the 2010 election, we felt there was a real opportunity

to create a new Iraq that could be a model for the region. We needed the United

States to protect the political process, to prevent violations of the

Constitution and to help develop democratic institutions.

For the sake of stability, Iraqiya agreed to join the national unity government

following a landmark power-sharing agreement reached a year ago in Erbil.

However, for more than a year now Mr. Maliki has refused to implement this

agreement, instead concentrating greater power in his own hands. As part of the

Erbil agreement, one of us, Ayad Allawi, was designated to head a proposed

policy council but declined this powerless appointment because Mr. Maliki

refused to share any decision-making authority.

After the 2010 election, Mr. Maliki assumed the roles of minister of the

interior, minister of defense and minister for national security. (He has since

delegated the defense and national security portfolios to loyalists without

parliamentary approval.) Unfortunately, the United States continued to support

Mr. Maliki after he reneged on the Erbil agreement and strengthened security

forces that operate without democratic oversight.

Now America is working with Iraqis to convene another national conference to

resolve the crisis. We welcome this step and are ready to resolve our problems

peacefully, using the Erbil agreement as a starting point. But first, Mr.

Maliki’s office must stop issuing directives to military units, making

unilateral military appointments and seeking to influence the judiciary; his

national security adviser must give up complete control over the Iraqi

intelligence and national security agencies, which are supposed to be

independent institutions but have become a virtual extension of Mr. Maliki’s

Dawa party; and his Dawa loyalists must give up control of the security units

that oversee the Green Zone and intimidate political opponents.

The United States must make clear that a power-sharing government is the only

viable option for Iraq and that American support for Mr. Maliki is conditional

on his fulfilling the Erbil agreement and dissolving the unconstitutional

entities through which he now rules. Likewise, American assistance to Iraq’s

army, police and intelligence services must be conditioned on those institutions

being representative of the nation rather than one sect or party.

For years, we have sought a strategic partnership with America to help us build

the Iraq of our dreams: a nationalist, liberal, secular country, with democratic

institutions and a democratic culture. But the American withdrawal may leave us

with the Iraq of our nightmares: a country in which a partisan military protects

a sectarian, self-serving regime rather than the people or the Constitution; the

judiciary kowtows to those in power; and the nation’s wealth is captured by a

corrupt elite rather than invested in the development of the nation.

We are glad that your brave soldiers have made it home for the holidays and we

wish them peace and happiness. But as Iraq once again teeters on the brink, we

respectfully ask America’s leaders to understand that unconditional support for

Mr. Maliki is pushing Iraq down the path to civil war.

Unless America acts rapidly to help create a successful unity government, Iraq

is doomed.

Ayad Allawi,

leader of the Iraqiya coalition,

was Iraq’s prime minister from 2004-5.

Osama

al-Nujaifi is the speaker of the Iraqi Parliament.

Rafe al-Essawi

is Iraq’s finance minister.

How to Save Iraq From Civil War, NYT, 27.12.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/28/opinion/how-to-save-iraq-from-civil-war.html

U.S. Embraces Low-Key Plan

as Turmoil in Iraq Deepens

December 24, 2011

The New York Times

By HELENE COOPER and THOM SHANKER

WASHINGTON — As Iraq erupted in recent days, Vice President Joseph R. Biden

Jr. was in constant phone contact with the leaders of the country’s dueling

sects. He called the Shiite prime minister and the Sunni speaker of the

Parliament on Tuesday, and the Kurdish leader on Thursday, urging them to try to

resolve the political crisis.

And for the United States, that is where the American intervention in Iraq

officially stops.

Sectarian violence and political turmoil in Iraq escalated within days of the

United States military’s withdrawal, but officials said in interviews that

President Obama had no intention of sending troops back into the country, even

if it devolved into civil war.

The United States, without troops on the ground or any direct influence over

Iraq’s affairs, has lost much of its leverage there. And so the latest crisis, a

descent into sectarian distrust and hostility that was punctuated by a bombing

in Baghdad on Thursday that killed more than 60 people, is being treated in much

the same way that the United States would treat any diplomatic emergency abroad.

Mr. Obama, his aides said, is adamant that the United States will not send

troops back to Iraq. At Fort Bragg, N.C., on Dec. 14, he told returning troops

that he had left Iraq in the hands of the Iraqi people, and in private

conversations at the White House, he has told aides that the United States gave

Iraqis an opportunity; what they do with that opportunity is up to them.

Though the president has been heralding the end of the Iraq war as a victory,

and a fulfillment of his campaign promise to bring American troops home, the

sudden crisis could quickly become a political problem for Mr. Obama, foreign

policy experts said.

“Right now, Iraq, along with getting Osama bin Laden, succeeding in Libya, and

restoring the U.S. reputation in the world, is a clear plus for Obama,” said

David Rothkopf, a former official in the administration of Bill Clinton and a

national security expert. “He kept his promise and got out. But the story could

turn on him very rapidly.”

For instance, Mr. Rothkopf and other national security experts said, Prime

Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki of Iraq is swiftly adopting policies that are

setting off deep divisions among Sunnis, Kurds and Shiites. If Iraq fragments,

if Iran starts to assert more visible influence or if a civil war breaks out,

“the president could be blamed,” Mr. Rothkopf said. “He would be remembered not

for leaving Iraq but for how he left it.”

Already, Mr. Obama is coming under political fire. Senator John McCain,

Republican of Arizona, said that Mr. Obama’s decision to pull American troops

out had “unraveled.” Appearing on CBS News on Thursday, Mr. McCain said that “we

are paying a very heavy price in Baghdad because of our failure to have a

residual force there,” adding that while he was disturbed by what had happened

in the past week, he was not surprised.

Administration officials, for their part, countered that it was hard to see how

American troops could have prevented either the political crisis or the

coordinated attacks in Iraq.

“These crises before happened when there were tens of thousands of American

troops in Iraq, and they all got resolved, but resolved by Iraqis through the

political process,” said Antony J. Blinken, Mr. Biden’s national security

adviser. “The test will be whether, with our diplomatic help, they continue to

use politics to overcome their differences, pursue power sharing and get to a

better place.”

So far, the administration is maintaining a hands-off stance in public, even as

Mr. Biden has privately exhorted Iraqi officials to mend their differences.

Several Obama administration officials have been on the phone all week imploring

Mr. Maliki and other Iraqi officials to quickly work through the charges and

countercharges swirling around Mr. Maliki’s accusation that the Sunni vice

president, Tariq al-Hashimi, enlisted personal bodyguards to run a death squad.

Aides said that Mr. Biden talked to Mr. Maliki; Osama al-Nujaifi, a Sunni

political leader; and Jalal Talabani, the Kurdish leader. He urged the men to

organize a meeting of Iraq’s top political leaders, from Mr. Maliki on down,

conveying the message that “you all need to stop hurling accusations at each

other through the media and actually sit together and work through your

competing concerns,” a senior administration official said. That official, like

several others, agreed to discuss internal administration thinking only on the

condition of anonymity because of the delicacy of the issue.

American officials say they believe that Mr. Talabani is the best person to

convene such a meeting, because he is respected by the most Iraqis.

Mr. Biden is not the only high-ranking American official who is actively

involved in discussions with Iraqi officials. David H. Petraeus, the director of

the C.I.A. who formerly served as the top commander in Iraq, traveled to Baghdad

recently for talks with his Iraqi counterparts.

Beyond that, Obama administration officials have conveyed to Mr. Maliki that the

American economic, security and diplomatic relationship with Iraq will be

“colored” by the extent to which Mr. Maliki can hold together a coalition

government that includes Sunnis and Kurds, one administration official said.

Even without a military presence in Iraq, the United States maintains at least

some leverage over Iraqi officials. Iraq wants to purchase F-16 warplanes from

the United States, for example, and the Obama administration has been trying to

help the government forge better relations with its Sunni Arab neighbors, like

the United Arab Emirates, which recently sent its defense chief to Baghdad to

talk about how the Iraqis could participate in regional exercises.

Pentagon officials and military officers had hoped a deal could be struck with

the Iraqi government to keep at least several thousand American combat troops

and trainers in Iraq after Dec. 31. But domestic politics in Iraq made that

impossible, and the outcome also fit with Mr. Obama’s narrative of a full

withdrawal from a war he vowed to end.

Even plans quietly drawn up for the continued deployment of counterterrorism

commandos were just as quietly pulled off the table, to make sure that Mr.

Obama’s pledge to reduce American combat forces to zero would be met, according

to senior administration officials.

The only American military personnel remaining in Iraq today are the fewer than

200 members of an Office of Security Cooperation that operates within the

American Embassy to coordinate military relations between Washington and

Baghdad, particularly arms sales.

The United States has about 40,000 service members remaining throughout the

Middle East and the Persian Gulf region, including a ground combat unit that was

one of the last out of Iraq — and remains, at least temporarily, just across the

border in Kuwait. Significant numbers of long-range strike aircraft also are on

call aboard aircraft carriers and at bases in the region.

As the responsibility for nurturing bilateral relations shifts to the State

Department, the responsibility for security assistance moves to the C.I.A.,

which operates in Iraq under a separate authority, independent of the military.

Although the United States military is unlikely to return to Iraq, it is

possible that military counterterrorism personnel could return, if approved by

the president, under C.I.A. authority, just as an elite team of Navy commandos

carried out the raid that killed Osama bin Laden under C.I.A. command.

The C.I.A. historically has operated its own strike teams, and it also has the

authority to hire indigenous operatives to participate in its counterterrorism

missions.

“As the U.S. military has drawn down to zero in terms of combat troops, the U.S.

intelligence community has not done the same,” a senior administration official

said. “Intelligence cooperation remains very important to the U.S.-Iraqi

relationship.”

The official acknowledged a risk punctuated by the recent unrest. “There are

serious counterterrorism issues that confront Iraq,” the official said. “And we

don’t want to let go of the very solid relationships we have built over the

years to share information of importance to both countries.”

Even if the unrest rose to levels approaching civil war, American officials

said, it was unlikely that Mr. Obama would allow the American military to

return.

“There is a strong sense that we need to let events in Iraq play out,” said one

senior administration official. “There is not a great deal of appetite for

re-engagement. We are not going to reinvade Iraq.”

U.S. Embraces Low-Key Plan as Turmoil in Iraq

Deepens, NYT, 24.12.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/25/world/middleeast/us-loses-leverage-in-iraq-now-that-troops-are-out.html

Clash Over Regional Power

Spurs Iraq’s Sectarian Rift

December 23, 2011

The New York Times

By JACK HEALY

BAQUBA, Iraq — The governor has fled this uneasy city. Half

the members of the provincial council are camped out in northern Iraq, afraid to

return to their offices. Peaceful protesters fill the dusty streets, though just

days ago angrier crowds blockaded the highways with burning tires and shattered

glass.

All of this because the local government here in northeastern Diyala Province

recently dared to raise a simple but explosive question, one that is central to

the unrest now surging through Iraq’s shaky democracy: Should a post-American

Iraq exist as one unified nation, or will it split into a loose confederation of

islands unto themselves?

A dire political crisis exploded in Baghdad this week, after an arrest warrant

was issued against the Sunni Arab vice president, Tariq al-Hashimi, accusing him

of running a death squad. But years of accumulated anger and disenfranchisement

are now driving some of the country’s largely Sunni Arab provinces to seek

greater control over their security and finances by distancing themselves from

Iraq’s Shiite leaders.

Many Sunni leaders have rallied to the cause while top Shiites in Baghdad have

fought the efforts, aggravating the sectarian divisions among the country’s

political elite.

“They feel that they have no future with the central government,” said Deputy

Prime Minister Saleh al-Mutlaq, a prominent Sunni.

This development comes at a moment of rising tensions and could herald a

near-breakdown of relations between the countryside and the leaders behind the

concrete walls and concertina wire guarding Baghdad’s Green Zone. It has

splintered communities within provinces along religious lines, while deepening

the sense of political uncertainty pervading Iraq in the days after the American

military’s withdrawal.

“We’ve reached a point where the exasperation with the entire political process

is so big in Sunni majority areas,” said Reidar Visser, an expert on Iraqi

politics and the editor of the blog historiae.org. “They are just fed up and

disillusioned.”

On Friday, thousands of protesters marched through largely Sunni cities to

condemn the warrant for Mr. Hashimi’s arrest. In Samarra, where the destruction

of a Shiite shrine in 2006 set off waves of violence, 2,000 demonstrators filled

the streets after Friday Prayer, waving signs that declared, “The people of

Samarra condemn the fabricated charges against Hashimi.”

The schism is one thread of a growing battle between Prime Minister Nuri Kamal

al-Maliki, a Shiite, and politicians from the political opposition and Iraq’s

Sunni Muslim minority.

Security forces who take orders from Mr. Maliki — sometimes personally — have

arrested dozens of people tied to opposition politicians in recent weeks. The

government accused Mr. Hashimi, the Sunni vice president, of running a death

squad from his offices in central Baghdad, a charge he denies. And Mr. Maliki

has urged Iraqi lawmakers to unseat his own deputy, Mr. Mutlaq, who frequently

inveighs against the prime minister.

A leading political coalition supported by many Sunnis and secular Iraqis has

boycotted Parliament, refusing to attend sessions, and its ministers and

lawmakers have threatened to resign en masse. An American-backed partnership

government uniting Iraq’s three main factions — the Shiite majority, Sunnis and

Kurds — appears poised to fall.

That discord is resonating in the largely Sunni provinces around the capital,

places that once hewed to a rigid nationalism cultivated by Saddam Hussein.

In recent months, Anbar, Salahuddin and Diyala Provinces have each pushed for a

public vote on creating their own regional governments.

Mr. Maliki has pushed back harder. His supporters contend that the movement

threatens to destabilize the central government. They say that regions

controlled only by local security forces would provide safe havens for Al Qaeda

in Iraq, the Baath Party and other Sunni-aligned militant groups at a tenuous

moment so soon after the American military withdrawal.

During a trip to Washington this month, Mr. Maliki was asked in a meeting about

the movement for greater regional control and offered a brusque reply, according

to an American who met with Mr. Maliki during his visit.

“His response was: ‘Everything those people are doing is illegal. The only way

to deal with them is through a legal process, and not a political process,’ ”

said the American, who asked to remain anonymous to avoid jeopardizing access to

Iraqi leaders. “This is not a guy who has any interest in compromising.”

Early Friday morning, Iraqi police commandos arrested a leading advocate of

Salahuddin Province’s push for regional status and seized his computer and reams

of documents, security officials said. They did not say why he had been

detained.

The provinces are not seeking a total divorce from the rest of Iraq, just a

wider separation in the mold of Kurdistan, the relatively prosperous and safe

area in northern Iraq. The Kurds, who have lived for decades as a people apart

from the rest of Iraq, have their own Parliament and president, command their

own security forces and have signed lucrative oil deals with foreign companies

without Baghdad’s approval.

It is not a new idea. Iraq’s Constitution gives provinces the right to carve out

their own regional governments. In 2006 and 2007, during Iraq’s civil war, Vice

President Joseph R. Biden Jr., then the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations

Committee, suggested partitioning the country into three federal states to calm

the sectarian bloodshed.

But could Iraq still stand if it were divided into Kurdistan, Shiitestan and

Sunnistan? Even raising the issue unleashes a torrent of emotion.

On Dec. 12, a majority of the members of the Diyala provincial council announced

that they were asking Iraq’s central government to hold a referendum on whether

the province could form its own semiautonomous region. Diyala is about 60

percent Sunni, 20 percent Shiite and 20 percent Kurdish, and its government

roughly reflects that breakdown.

Distrust of the central government runs deep here among the snaking rivers and

palm plantations that once served as battlegrounds and hide-outs for Qaeda

insurgents. Last year, three of the Sunni members of the provincial council were

thrown into jail by Iraqi security forces. Others were threatened.

But the abrupt announcement of a potential Diyala region angered and frightened

some of the province’s Shiites. It was read as a power grab that would put

Shiites and Kurds in the province at the mercy of unknown new security forces,

and could presage the fragmentation of Iraq.

On Dec. 15, about 1,000 outraged demonstrators, most of them Shiites, streamed

past the Shiite-dominated national police forces and into the provincial

council’s headquarters. They occupied the building for a few hours, then set up

roadblocks and tents in the streets. Half the city’s elected officials fled for

safety.

Protesters said they had acted spontaneously, but several Sunni officials

believed that Iraq’s central government had mobilized the protesters and stoked

their outrage to kill the proposal.

“We left the city because of the chaos and insecurity,” said Rasim al-Ugaili, a

member of the provincial council who supported the proposal for a new region.

“We feared for our lives.”

A few days later, the roads were clear, but the fate of the Diyala region was

anything but. The Kurds on the provincial council withdrew their support for the

referendum after the protests erupted, and much of the council was still

missing.

The deputy governor, Furat al-Tamimi, was filling in until his boss returned.

Mr. Tamimi, a Shiite, said he was pleased to see the banners and protesters

shouting passionately through the afternoon. “This is all about democracy,” he

said.

Reporting was contributed by Omar al-Jawoshy from Baghdad, Duraid

Adnan

and an Iraqi employee of The New York Times from Baquba,

and an Iraqi employee of The Times from Samarra.

Clash Over Regional Power Spurs Iraq’s

Sectarian Rift, NYT, 23.12.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/24/world/middleeast/iraqi-sunnis-and-shiites-clash-over-regional-power.html

The End, for Now

December 20, 2011

The New York Times

By THOMAS L. FRIEDMAN

With the withdrawal of the last U.S. troops from Iraq, we’re

finally going to get the answer to the core question about that country: Was

Iraq the way Iraq was because Saddam was the way Saddam was, or was Saddam the

way Saddam was because Iraq is the way Iraq is — a collection of sects and

tribes unable to live together except under an iron fist. Now we’re going to get

the answer because both the internal iron fist that held Iraq together (Saddam

Hussein) and the external iron fist (the U.S. armed forces) have been removed.

Now we will see whether Iraqis can govern themselves in a decent manner that

will enable their society to progress — or end up with a new iron fist. You have

to hope for the best because so much is riding on it, but the early signs are

worrying.

Iraq was always a war of choice. As I never bought the argument that Saddam had

nukes that had to be taken out, the decision to go to war stemmed, for me, from

a different choice: Could we collaborate with the people of Iraq to change the

political trajectory of this pivotal state in the heart of the Arab world and

help tilt it and the region onto a democratizing track? After 9/11, the idea of

helping to change the context of Arab politics and address the root causes of

Arab state dysfunction and Islamist terrorism — which were identified in the

2002 Arab Human Development Report as a deficit of freedom, a deficit of

knowledge and a deficit of women’s empowerment — seemed to me to be a legitimate

strategic choice. But was it a wise choice?

My answer is twofold: “No” and “Maybe, sort of, we’ll see.”

I say “no” because whatever happens in Iraq, even if it becomes Switzerland, we

overpaid for it. And, for that, I have nothing but regrets. We overpaid in

lives, in the wounded, in tarnished values, in dollars and in the lost focus on

America’s development. Iraqis, of course, paid dearly as well.

One reason the costs were so high is because the project was so difficult.

Another was the incompetence of George W. Bush’s team in prosecuting the war.

The other reason, though, was the nature of the enemy. Iran, the Arab dictators

and, most of all, Al Qaeda did not want a democracy in the heart of the Arab

world, and they tried everything they could — in Al Qaeda’s case, hundreds of

suicide bombers financed by Arab oil money — to sow enough fear and sectarian

discord to make this democracy project fail.

So no matter the original reasons for the war, in the end, it came down to this:

Were America and its Iraqi allies going to defeat Al Qaeda and its allies in the

heart of the Arab world or were Al Qaeda and its allies going to defeat them?

Thanks to the Sunni Awakening movement in Iraq, and the surge, America and its

allies defeated them and laid the groundwork for the most important product of

the Iraq war: the first ever voluntary social contract between Sunnis, Kurds and

Shiites for how to share power and resources in an Arab country and to govern

themselves in a democratic fashion. America helped to midwife that contract in

Iraq, and now every other Arab democracy movement is trying to replicate it —

without an American midwife. You see how hard it is.

Which leads to the “maybe, sort of, we’ll see.” It is possible to overpay for

something that is still transformational. Iraq had its strategic benefits: the

removal of a genocidal dictator; the defeat of Al Qaeda there, which diminished

its capacity to attack us; the intimidation of Libya, which prompted its

dictator to surrender his nuclear program (and helped expose the Abdul Qadeer

Khan nuclear network); the birth in Kurdistan of an island of civility and free

markets and the birth in Iraq of a diverse free press. But Iraq will only be

transformational if it truly becomes a model where Shiites, Sunnis and Kurds,

the secular and religious, Muslims and non-Muslims, can live together and share

power.

As you can see in Syria, Yemen, Egypt, Libya and Bahrain, this is the issue that

will determine the fate of all the Arab awakenings. Can the Arab world develop

pluralistic, consensual politics, with regular rotations in power, where people

can live as citizens and not feel that their tribe, sect or party has to rule or

die? This will not happen overnight in Iraq, but if it happens over time it

would be transformational, because it is the necessary condition for democracy

to take root in that region. Without it, the Arab world will be a dangerous

boiling pot for a long, long time.

The best-case scenario for Iraq is that it will be another Russia — an

imperfect, corrupt, oil democracy that still holds together long enough so that

the real agent of change — a new generation, which takes nine months and 21

years to develop — comes of age in a much more open, pluralistic society. The

current Iraqi leaders are holdovers from the old era, just like Vladimir Putin

in Russia. They will always be weighed down by the past. But as Putin is

discovering — some 21 years after Russia’s democratic awakening began — that new

generation thinks differently. I don’t know if Iraq will make it. The odds are

really long, but creating this opportunity was an important endeavor, and I have

nothing but respect for the Americans, Brits and Iraqis who paid the price to

make it possible.

The End, for Now, NYT, 20.12.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/21/opinion/friedman-the-end-for-now.html

Sunni Leader in Iraq

Denies Ordering Assassinations

December 20, 2011

The New York Times

By MICHAEL S. SCHMIDT

BAGHDAD — The political crisis in Iraq deepened on Tuesday, as the Sunni vice

president angrily rebutted charges that he had ordered his security guards to

assassinate government officials, saying that Shiite-backed security forces had

induced the guards into false confessions.

In a nationally televised news conference, the vice president, Tariq al-Hashimi,

blamed the Shiite-led government of Prime Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki for

using the country’s security forces to persecute political opponents,

specifically Sunnis.

“The accusations have not been proven, so the accused is innocent until proven

guilty,” Mr. Hashimi said at the news conference in Erbil, in the Kurdish north

of Iraq. “I swear by God I didn’t do this disobedience against Iraqi blood, and

I would never do this.”

He added: “The goal is clear, it is not more than political slander.”

Standing in front of an Iraqi flag, Mr. Hashimi questioned why Mr. Maliki had

waited until the day after the American military withdrew its troops from Iraq

to publicly lay out the charges.

Almost as significant as what Mr. Hashimi said was where he said it: in Erbil,

the capital of the semi-autonomous northern region of Kurdistan. Because of the

region’s autonomy, Mr. Maliki’s security forces cannot easily act on a warrant

issued Monday to arrest Mr. Hashimi.

Mr. Hashimi said he would not return to Baghdad, effectively making him an

internal exile. The case against him should be transferred to Kurdistan where he

could face a fair trial, he said.

The response from Mr. Hashimi came a day after the Shiite-led government ordered

him arrested and played videotaped confessions on national television from three

men who said they had worked as his bodyguards and had been ordered by him to

commit murders. The men claimed to have used roadside bombs and

silencer-equipped pistols to kill Iraqi government officials and security

officers. Mr. Hashimi, they said, rewarded them with money.

Shortly before the news conference on Tuesday, the speaker of the Parliament,

Osama al-Nujaifi, one of the most respected Sunni leaders in Iraq, issued a

statement saying that the playing of the videotapes had a “sectarian” tone that

tried to exploit the historic divide between Sunnis and Shiites.

Mr. Nujaifi’s statements were striking because he has said little publicly about

the growing crisis, and in recent years has cast himself as a nationalist,

developing close relationships with Mr. Maliki and other Shiite leaders.

Since the accusations surfaced over the weekend, there has been no noticeable

increase in violence. Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether the political

tension would galvanize Sunnis and insurgents against the government or would be

a political drama that plays itself out in televised news conferences.

Mr. Hashimi, a close ally of the United States, criticized President Obama, who

ordered American troops in October to leave Iraq by the end of 2011.

“I’m surprised by the statement of President Obama when he said that the United

States had left a democratic Iraq,” he said.

“Is that the reality of Iraq? I’m sad. Either the American president is deceived

or he is overlooking the facts existing here. Today my house is surrounded with

tanks. I’d ask him, what democracy are you talking about President Obama?”

As Mr. Hashimi’s news conference was broadcast on several Iraqi television

channels, the state-run channel replayed the confessions from his guards at

least twice.

In the confessions, one of the men said that Mr. Hashimi asked him whether he

would carry out attacks on his behalf. After saying he would, the man said he

received orders from one of Mr. Hashimi’s deputies.

Among the attacks the man said he committed was planting a bomb in a busy

traffic circle and assassinating an official from the Foreign Ministry with a

silencer pistol.

“The vice president called us, and he thanked us,” said the man, Abdul Karim

Mohammed al-Jabouri. “He gave us an envelope with money, and I thanked him.”

Yasir Ghazi and Zaid Thaker contributed reporting.

Sunni Leader in Iraq Denies Ordering

Assassinations, NYT, 20.12.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/21/world/middleeast/sunni-leader-in-iraq-denies-ordering-assassinations.html

Arrest Order for Sunni Leader in Iraq

Opens New Rift

December 19, 2011

The New York Times

By JACK HEALY

BAGHDAD — Iraq’s Shiite-dominated government was thrown into

crisis on Monday night as authorities issued an arrest warrant for the Sunni

vice president, accusing him of running a personal death squad that assassinated

security officials and government bureaucrats.

The sensational charges against Tariq al-Hashimi, one of the country’s most

prominent Sunni leaders, threatened to inflame widening sectarian and political

conflicts in Iraq just one day after the last American convoy of American troops

rolled out of the country into Kuwait.

The accusations were broadcast over Iraqi television, in a half-hour of grainy

video confessions from three men identified as Mr. Hashimi’s bodyguards. They

spoke of how they had planted bombs in public squares, driven up to convoys

carrying Iraqi officials and opened fire.

Under the direction of Mr. Hashimi’s top aides, the men said, they gunned down

convoys carrying Shiite officials and planted roadside bombs in traffic circles

and wealthy neighborhoods of Baghdad, then detonated them as their targets drove

by. One of the men said Mr. Hashimi had personally handed him an envelope with

$3,000 after one of the attacks.

It was impossible to substantiate any of the accusations aired in the

confessions.

An aide in Mr. Hashimi’s office said the three men had indeed worked for the

vice president, but he denied all of the allegations. The aide said Mr. Hashimi

was in the northern region of Kurdistan, meeting with Kurdish officials to

defuse the worsening political standoff with Prime Minister Nuri Kamal

al-Maliki.

Reidar Visser, an analyst of Iraqi politics and editor of the blog

historiae.org, called the situation the worst crisis Iraq had faced in five

years.

“Any leading Sunni politician seems now to be a target of this campaign by

Maliki,” Mr. Visser said. “It seems that every Sunni Muslim or secularist is in

danger of being labeled either a Baathist or a terrorist.”

The last week has yielded a near breakdown of relations between Mr. Maliki, a

religious Shiite, and his adversaries in the Iraqiya coalition, a large

political bloc that holds some 90 seats in Parliament and is supported by many

Sunni Iraqis.

Members of the Iraqiya coalition walked away from Parliament on Saturday,

accusing Mr. Maliki of seizing power and thwarting democratic procedures through

a wave of politically tinged arrests in recent weeks. The boycott was the

culmination of months of political discord, and signaled the near breakdown of

relations between two of the country’s most powerful political adversaries.

Earlier on Monday, Iraq’s high court — a body often seen as beholden to Mr.

Maliki — announced it was barring Mr. Hashimi from leaving the country. For days

before the confessions were broadcast, several of Mr. Hashimi’s bodyguards were

detained while state-run television and government surrogates promised to reveal

evidence tying Mr. Hashimi to criminal acts.

On Sunday, Mr. Maliki sent a letter to Parliament seeking a no-confidence vote

in one of his deputies, a prominent Sunni politician who has also been a

vociferous critic.

The American Embassy said Ambassador James F. Jeffrey was in contact with Iraqi

officials, but declined to comment further.

Arrest Order for Sunni Leader in Iraq Opens

New Rift, NYT, 19.12.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/20/world/middleeast/iraqi-government-accuses-top-official-in-assassinations.html

Iraq, a War Obama Didn’t Want,

Shaped His Foreign

Policy

December 17, 2011

The New York Times

By MARK LANDLER

WASHINGTON — President Obama has made good on his campaign

pledge to end the Iraq war, portraying the departure of the last troops as a

chance to turn to nation-building at home.

But from Afghanistan to the Arab Spring, from China to counterterrorism, the

lessons of that war still hang over the administration’s foreign policy —

shaping, and sometimes limiting, how the president projects American power in

the world.

The war that Mr. Obama never wanted to fight has weighed on internal debates,

dictated priorities and often narrowed options for the United States, according

to current and former administration officials.

Most tangibly, the swift American drawdown in Iraq will influence how the United

States handles the endgame in Afghanistan, where NATO forces have agreed to hand

over security and pull out by 2014. The fact that the troops are leaving Iraq

without a wholesale breakdown in security, some analysts said, may embolden a

war-weary administration to move up the timetable for getting out of

Afghanistan.

It has also shifted the balance of power in Washington, from the military

commanders, who were desperate to leave a residual force of soldiers in Iraq,

toward Mr. Obama’s civilian advisers, who are busy calculating how getting them

all home by Christmas might help their boss’s re-election bid.

“There used to be a hot debate over even setting a timetable,” said Benjamin J.

Rhodes, a deputy national security adviser. While he cautioned that Iraq is not

a perfect precedent for Afghanistan, “there should be no doubt about our

commitment to follow through on the timelines we set in Afghanistan,” he said.

Mr. Rhodes, who wrote Mr. Obama’s foreign policy speeches during his 2008

campaign, said Iraq was a “dramatically underrepresented element of the way in

which people look at Obama’s foreign policy.” As a candidate whose opposition to

the war helped define him, Mr. Rhodes said, “Senator Obama constructed an entire

argument of foreign policy, based on Iraq.”

His argument had two central pillars: that Iraq had taken the United States’ eye

off the real battle in Afghanistan, and that it had diminished the United

States’ standing in the world. This led directly to two of the administration’s

most significant foreign policy and national security projects: Mr. Obama’s

lethal counterterrorism strategy and his recent series of diplomatic and

military initiatives in Asia.

The drone strikes and commando raids that the president recently boasted had

killed “22 out of 30 top Al Qaeda leaders,” including Osama bin Laden, were

honed in the night raids by American troops on militants in Iraq.

Mr. Obama’s emphasis on restoring the United States’ place in Asia grew out of a

post-Iraq “strategic rebalancing” pushed by Secretary of State Hillary Rodham

Clinton and the national security adviser, Thomas E. Donilon. The war, they

contend, sucked American time and resources from other parts of the world,

allowing China to expand its sway throughout much of the Pacific Rim.

In the early days of his presidency, as Mr. Obama weighed more troop deployments

in Afghanistan, he was still heavily influenced by commanders like Gen. David H.

Petraeus, who was fresh off his successful “surge” in Iraq and pressed for an

ambitious counterinsurgency strategy in Afghanistan.

“Here was a general who, in Petraeus’s case, had turned around a situation

dramatically in Iraq, and was offering to do it again,” said Bruce O. Riedel,

who ran the White House’s initial policy review on Afghanistan.

By 2011, however, Mr. Obama had developed his own views about the use of

military force. His reluctant intervention in Libya — only after receiving the

imprimatur of the Arab League, and then with limited military engagement — bore

the hallmarks of a post-Iraq operation. In Syria, where a dictator in the

Baathist tradition of Saddam Hussein has killed his own people, the United

States has not considered a no-fly zone, let alone broader military

intervention.

“The larger legacy of Iraq was that the U.S. military cannot shape outcomes,”

said Vali Nasr, a former senior adviser in the State Department. “That led to

skittishness on our part about using the military.”

Mr. Obama made much of his commitment to a multilateral foreign policy, in

contrast to President George W. Bush’s unilateral invasion of Iraq. That, his

advisers say, grew out of a conviction the United States needed to work with

others and forge consensus to restore its moral standing.

But it also reflects a sober economic reality: with more than $800 billion in

costs from the Iraq war — and nearly $450 billion from Afghanistan — the United

States can no longer afford another big, go-it-alone military campaign.

“The impulse toward multilateralism is more complicated,” said Dennis B. Ross,

who until last month was one of Mr. Obama’s senior Middle East advisers. “There

is a desire, understandably, for our actions to have greater legitimacy on the

world stage. But there is also an interest in burden-sharing and sharing the

cost as well.”

Some analysts argue that the administration’s multilateral approach owes less to

Iraq than it does to traditional Democratic Party philosophy.

“No doubt, Iraq contributed to his view that we should wield power less, should

not act without U.N. resolutions and multilateral support, and should try to

‘engage’ with hostile regimes, but I suspect the president held those views

years earlier,” said Elliott Abrams, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign

Relations who worked in the George W. Bush and Reagan administrations.

“That’s pretty standard stuff on the left,” he added. “Iraq made them more

central to his actions as president, but I doubt it taught him much.”

The Bush administration had hoped that Iraq would be a catalyst for democratic

change across the Arab world. But there is little evidence that Iraq prepared

the United States for the political changes that swept over the Middle East and

North Africa this spring, eight years after American troops toppled Mr. Hussein.

The Obama administration’s initial response to the upheaval in Egypt and

elsewhere was halting, as it balanced its support for the protesters with its

fear of losing strategic allies. Mr. Rhodes said Iraq’s legacy was visible in

the administration’s insistence on homegrown, rather than externally imposed,

democratic change. That is likely to mean coming to terms with rulers it views

as less than ideal, like the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist parties,

which made striking gains in Egypt’s recent parliamentary elections.

“Iraq has taught us we can live with Islamists,” Mr. Nasr said. “We can live

with a Maliki in Egypt,” he said, referring to Iraq’s Shiite prime minister,

Nuri Kamal al-Maliki. “Iraq exorcised the way we latched on to secular

dictators.”

Iraq, a War Obama Didn’t Want, Shaped His

Foreign Policy, NYT, 17.12.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/18/us/politics/iraq-war-shaped-obamas-foreign-policy-white-house-memo.html

Last Convoy of American Troops

Leaves Iraq,

Marking an End to the War

December 18, 2011

The New York Times

By TIM ARANGO and MICHAEL S. SCHMIDT

BAGHDAD — The last convoy of American troops to leave Iraq drove

into Kuwait on Sunday morning, marking the end of the nearly nine-year war.

The convoy’s departure, which included about 110 vehicles and 500 soldiers, came

three days after the American military folded its flag in a muted ceremony here

to celebrate the end of its mission.

In darkness, the convoy snaked out of Contingency Operating Base Adder, near the

southern city of Nasiriyah, around 2:30 a.m., and headed toward the border. The

departure appeared to be the final moment of a drawn-out withdrawal that

included weeks of ceremonies in Baghdad and around Iraq, and included visits by

Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. and Defense Secretary Leon E. Panetta, as

well as a trip to Washington by Prime Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki of Iraq.

As dawn approached on Sunday morning, the last trucks began to cross over the

border into Kuwait at an outpost lit by floodlights and secured by barbed wire.

“I just can’t wait to call my wife and kids and let them know I am safe,” said

Sgt. First Class Rodolfo Ruiz just before his armored vehicle crossed over the

border. “I am really feeling it now.”

Shortly after crossing into Kuwait, Sergeant Ruiz told the men in his vehicle:

“Hey guys, you made it.”

Then, he ordered the vehicles in his convoy not to flash their lights or honk

their horns.

For security reasons, the last soldiers made no time for goodbyes to Iraqis with

whom they had become acquainted. To keep details of the final trip secret from

insurgents, interpreters for the last unit to leave the base called local tribal

sheiks and government leaders on Saturday morning and conveyed that business

would go on as usual, not letting on that all the Americans would soon be gone.

Many troops wondered how the Iraqis, whom they had worked closely with and

trained over the past year, would react when they awoke on Sunday to find that

the remaining American troops on the base had left without saying anything.

“The Iraqis are going to wake up in the morning and nobody will be there,” said

a soldier who only identified himself as Specialist Joseph. He said he had

immigrated to the United States from Iraq in 2009 and enlisted a year later, and

refused to give his full name because he worried for his family’s safety.

Fearing that insurgents would try to attack the last Americans leaving the

country, the military treated all convoys like combat missions.

As the armored vehicles drove through the desert, Marine, Navy and Army

helicopters and planes flew overhead scanning the ground for insurgents and

preparing to respond if the convoys were attacked.

Col. Douglas Crissman, one of the military’s top commanders in southern Iraq,

said in an interview on Friday that he planned to be in a Blackhawk helicopter

over the convoy with special communication equipment.

“It is a little bit weird,” he said, referring to how he had not told his

counterparts in the Iraqi military when they were leaving. “But the

professionals among them understand.”

Over the past year, Colonel Crissman and his troops spearheaded the military’s

efforts to ensure the security of the long highway that passes through southern

Iraq that a majority of convoys traveled on their way out of the country.

“Ninety-five percent of what we have done has been for everyone else,” Colonel

Crissman said.

Across the highway, the military built relationships with 20 tribal sheiks,

paying them to clear the highway of garbage, making it difficult for insurgents

to hide roadside bombs in blown-out tires and trash.

Along with keeping the highway clean, the military hoped that the sheiks would

help police the highway and provide intelligence on militants.

“I can’t possibly be all places at one time,” said Colonel Crissman in an

interview in May. “There are real incentives for them to keep the highway safe.

Those sheiks we have the best relationships with and have kept their highways

clear and safe will be the most likely ones to get renewed for the remainder of

the year.”

All American troops were legally obligated to leave the country by the end of

the month, but President Obama, in announcing in October the end of the American

military role here, promised that everyone would be home for the holidays.

The United States will continue to play a role in Iraq. The largest American

embassy in the world is located here, and in the wake of the military departure

it is doubling in size — from about 8,000 people to 16,000 people, most of them

contractors. Under the authority of the ambassador will be less than 200

military personnel, to guard the embassy and oversee the sale of weapons to the

Iraqi government.

History’s final judgment on the war, which claimed nearly 4,500 American lives

and cost almost $1 trillion, may not be determined for decades. But it will be

forever tainted by the early missteps and miscalculations, the faulty

intelligence over Saddam Hussein’s weapons programs and his supposed links to

terrorists, and a litany of American abuses, from the Abu Ghraib prison torture

scandal to a public shootout involving Blackwater mercenaries that left

civilians dead — a sum of agonizing factors that diminished America’s standing

in the Muslim world and its power to shape events around the globe.

When President George W. Bush announced the start of the war in 2003 in an

address from the Oval Office, he proclaimed, “we will accept no outcome but

victory.”

But the end appears neither victory, nor defeat, but a stalemate — one in which

the optimists say violence has been reduced to a level that will allow the

country to continue on its lurching path toward stability and democracy, and the

pessimists say the American presence has been a bandage on a festering wound.

The war’s conclusion marks a political triumph for President Obama, who ran for

office promising to bring the troops home, but is bittersweet for Iraqis who

will now face on their own the unfinished legacy of a conflict that rid their

country of a hated dictator but did little else to improve their lives.

Last Convoy of American Troops Leaves Iraq,

Marking an End to the War, NYT, 18.12.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/19/world/middleeast/last-convoy-of-american-troops-leaves-iraq.html

An Unstable, Divided Land

December 15, 2011

The New York Times

By REIDAR VISSER

Noordwijk, the Netherlands

WHEN the last remaining American forces withdraw from Iraq at the

end of this month, they will be leaving behind a country that is politically

unstable, increasingly volatile, and at risk of descending into the sort of

sectarian fighting that killed thousands in 2006 and 2007.

Prime Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki has overseen a consolidation of military

force, but the core of his government is remarkably unrepresentative: it is made

up of mostly pro-Iranian Shiite Islamists. The secular Iraqiya Party, which won

a plurality of votes in the March 2010 parliamentary elections, has been

marginalized within the cabinet and was not represented when Mr. Maliki visited

Washington on Monday.

This Shiite Islamist government bodes ill for the country’s future. And

unfortunately, it is a direct product of America’s misguided thinking about Iraq

since the 2003 invasion — an approach that stressed proportional sectarian

representation rather than national unity and moderate Islamism.

This flawed policy has been more important in shaping today’s Iraq than the size

of the original force that occupied the country in 2003, the Abu Ghraib

prison-abuse scandal in 2004 or the “surge” of 2007. And it is to blame for the

precarious condition in which the United States is leaving Iraq today.

In the 1990s, America envisaged post-Saddam Hussein Iraq as a federation of

Arabs and Kurds. At the time, Kurds focused on their own autonomy; Shiite

Islamists rejected federalism south of Kurdistan; and many other Shiites

explicitly ruled out an Iranian model of government for fear that it might

alienate secularists and the Sunni minority.

The fateful change in American thinking came in 2002 as the Bush administration

was preparing for war. At conferences with exiled Iraqi opposition leaders,

Americans argued that new political institutions should reflect Iraq’s

ethno-sectarian groups proportionally. Crucially, the focus moved beyond the

primary Arab-Kurdish cleavage to include notions of separate quotas for Shiites

and Sunnis.

When Americans designed the first post-Hussein political institution in July

2003, the Iraqi governing council, the underlying principle was sectarian

proportionality. What had formerly been an Arab-Kurdish relationship was

transformed into a Sunni-Shiite-Kurdish triangle. Arabs who saw themselves first

and foremost as Iraqis suddenly became anomalies.

Remarkably, Iraqis themselves turned against this system. After the violent

sectarian conflict in 2006 and 2007, Iraqis rediscovered nationalism. The

American surge and growing nationalist criticism of the country’s new

constitution provided the necessary environment for Mr. Maliki to emerge in 2009

as a national leader who commanded respect across sectarian lines. Some Sunnis

even began considering a joint ticket with Mr. Maliki.

But in May 2009, with President Obama now in the White House, Shiite Islamists

who had been marginalized by Mr. Maliki in the local elections regrouped in

Tehran. Their aim was a purely sectarian Shiite alliance that would ultimately

absorb Mr. Maliki as well. The purging of Sunni officials with links to the

former government, known as de-Baathification, became their priority.

By this time, however, Washington was blind to what was going on. Instead of

appreciating the intense struggle between the cleric Moktada al-Sadr’s sectarian

Shiite followers, and moderate Shiites who believed in a common Iraqi identity,

the Obama administration remained steadfastly focused on the

Sunni-Shiite-Kurdish trinity, thereby reinforcing sectarian tensions rather than

helping defuse them.

After faring poorly in the 2010 parliamentary elections, Mr. Maliki switched

course and adopted a pan-Shiite sectarian platform to win a second term as prime

minister. But Obama administration officials failed to see how Mr. Maliki had

changed. Nor did they appreciate the chance they’d had to bring Mr. Maliki back

from the sectarian brink through a small but viable coalition with the secular

Iraqiya Party — a scenario that could have provided competent, stable government

to Iraqi Arabs and left the Kurds to handle their own affairs.

Instead, an oversize, unwieldy power-sharing government was formed, with

Washington’s support, in December 2010.

The main reason Mr. Maliki could not offer American forces guarantees for

staying in the country beyond 2011 was that his premiership was clinched by

pandering to sectarian Shiites. As a result, he has become a hostage to the

impulses of pro-Iranian Islamists while most Sunnis and secularists in the

government have been marginalized. His current cabinet is simply too big and

weak to develop any coherent policies or keep Iranian influence at bay.

By consistently thinking of Mr. Maliki as a Shiite rather than as an Iraqi Arab,

American officials overlooked opportunities that once existed in Iraq but are

now gone. Thanks to their own flawed policies, the Iraq they are leaving behind

is more similar to the desperate and divided country of 2006 than to the

optimistic Iraq of early 2009.

Reidar Visser,

a research fellow

at the Norwegian Institute of

International Affairs,

is the author of “A Responsible End?

The United States and the Iraqi Transition, 2005-2010.”

An Unstable, Divided Land, NYT, 15.12.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/16/opinion/an-unstable-divided-land.html

In Iraq, Abandoning Our Friends

December 15, 2011

The New York Times

By KIRK W. JOHNSON

West Chicago, Ill.

ON the morning of May 6, 1783, Guy Carleton, the British commander charged with

winding down the occupation of America, boarded the Perseverance and sailed up

the Hudson River to meet George Washington and discuss the British withdrawal.

Washington was furious to learn that Carleton had sent ships to Canada filled

with Americans, including freed slaves, who had sided with Britain during the

revolution.

Britain knew these loyalists were seen as traitors and had no future in America.

A Patriot using the pen name “Brutus” had warned in local papers: “Flee then

while it is in your power” or face “the just vengeance of the collected

citizens.” And so Britain honored its moral obligation to rescue them by sending

hundreds of ships to the harbors of New York, Charleston and Savannah. As the

historian Maya Jasanoff has recounted, approximately 30,000 were evacuated from

New York to Canada within months.

Two hundred and twenty-eight years later, President Obama is wrapping up our own

long and messy war, but we have no Guy Carleton in Iraq. Despite yesterday’s

announcement that America’s military mission in Iraq is over, no one is acting

to ensure that we protect and resettle those who stood with us.

Earlier this week, Mr. Obama spoke to troops at Fort Bragg, N.C., of the

“extraordinary milestone of bringing the war in Iraq to an end.” Forgotten are

his words from the campaign trail in 2007, that “interpreters, embassy workers

and subcontractors are being targeted for assassination.” He added, “And yet our

doors are shut. That is not how we treat our friends.”

Four years later, the Obama administration has admitted only a tiny fraction of

our own loyalists, despite having eye scans, fingerprints, polygraphs and

letters from soldiers and diplomats vouching for them. Instead we force them to

navigate a byzantine process that now takes a year and a half or longer.

The chances for speedy resettlement of our Iraqi allies grew even worse in May

after two Iraqi men were arrested in Kentucky and charged with conspiring to

send weapons to jihadist groups in Iraq. These men had never worked for

Americans, and they managed to enter the United States as a result of poor

background checks. Nevertheless, their arrests removed any sense of urgency in

the government agencies responsible for protecting our Iraqi allies.

The sorry truth is that we don’t need them anymore now that we’re leaving, and

resettling refugees is not a winning campaign issue. For over a year, I have

been calling on members of the Obama administration to make sure the final act

of this war is not marred by betrayal. They have not listened, instead adopting

a policy of wishful thinking, hoping that everything turns out for the best.

Meanwhile, the Iraqis who loyally served us are under threat. The extremist

Shiite leader Moktada al-Sadr has declared the Iraqis who helped America

“outcasts.” When Britain pulled out of Iraq a few years ago, there was a public

execution of 17 such outcasts — their bodies dumped in the streets of Basra as a

warning. Just a few weeks ago, an Iraqi interpreter for the United States Army

got a knock on his door; an Iraqi policeman told him threateningly that he would

soon be beheaded. Another employee, at the American base in Ramadi, is in hiding

after receiving a death threat from Mr. Sadr’s militia.

It’s not the first time we’ve abandoned our allies. In 1975, President Gerald R.

Ford and Henry A. Kissinger ignored the many Vietnamese who aided American

troops until the final few weeks of the Vietnam War. By then, it was too late.

Although Mr. Kissinger had once claimed there was an “irreducible list” of

174,000 imperiled Vietnamese allies, the policy in the war’s frantic closing

weeks was icily Darwinian: if you were strong enough to clear our embassy walls

or squeeze through the gates and force your way onto a Huey, you could come

along. The rest were left behind to face assassination or internment camps. The

same sorry story occurred in Laos, where America abandoned tens of thousands of

Hmong people who had aided them.

It wasn’t until months after the fall of Saigon, and much bloodshed, that

America conducted a huge relief effort, airlifting more than 100,000 refugees to

safety. Tens of thousands were processed at a military base on Guam, far away

from the American mainland. President Bill Clinton used the same base to save

the lives of nearly 7,000 Iraqi Kurds in 1996. But if you mention the Guam

Option to anyone in Washington today, you either get a blank stare of historical

amnesia or hear that “9/11 changed everything.”

And so our policy in the final weeks of this war is as simple as it is shameful:

submit your paperwork and wait. If you can survive the next 18 months, maybe

we’ll let you in. For the first time in five years, I’m telling Iraqis who write

to me for help that they shouldn’t count on America anymore.

Moral timidity and a hapless bureaucracy have wedged our doors tightly shut and

the Iraqis who remained loyal to us are weeks away from learning how little

America’s word means.

Kirk W. Johnson,

a former reconstruction coordinator in Iraq,

founded the List Project to Resettle Iraqi Allies.

In Iraq, Abandoning Our Friends, NYT,

15.12.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/16/opinion/in-iraq-abandoning-our-friends.html

A Formal End

December 15, 2011

The New York Times

It is a relief that the American role in the misguided Iraq war

is finally over. It came to an official close on Thursday with an appropriately

subdued ceremony in Baghdad. We mourn the nearly 4,500 American troops and tens

of thousands of Iraqis who lost their lives.

After so much pain and sacrifice, Iraqis now have the responsibility for making

their own better future. The fighting is not over, and success is still a long

shot. The United States has a major role to play: encouraging, supporting and

goading Iraq’s leaders to make the long-delayed political compromises that are

their only hope for building a stable democracy.

The fact that Saddam Hussein is gone is a genuine cause for celebration. But the

list of errors and horrors in this war is inexcusably long, starting with a rush

to invasion based on manipulated intelligence.

The Bush administration had no plan for governing the country once Saddam was

deposed. The Iraqi economy still bears the scars from the first frenzied days of

looting. The decision to disband the Sunni-dominated Iraqi Army helped unleash

five years of sectarian strife that has not fully abated. Iraq’s political

system remains deeply riven by ethnic and religious differences.

America’s reputation has yet to fully recover from the horrors of Abu Ghraib.

The country is still paying a huge price for President George W. Bush’s decision

to shortchange the war in Afghanistan. American policy makers, for generations

to come, must study these mistakes carefully and ensure that they are not

repeated.

As for Iraq today, the authoritarian tendencies of Prime Minister Nuri Kamal

al-Maliki are deeply troubling. A member of the Shiite majority that was badly

persecuted under Saddam, he has been far more interested in payback than

inclusion.

Washington has pushed him over the years — but, often, not hard enough.

The Baghdad government promised jobs to 100,000 members of the Sunni Awakening

movement — insurgents whose decision to switch sides helped end the civil war —

but only half that have been hired. Parliament still needs to enact a law,

called for in the Constitution, that would provide a legal basis for determining

who should be prosecuted for supporting Saddam’s Baath Party or other extremist

ideologies. Iraq’s leaders have many more issues to resolve. Incredibly, they

have still not decided how to divide the country’s oil wealth. There is no

agreement on who will control the oil-rich city of Kirkuk, which is claimed by

both Baghdad and the semiautonomous Kurdish regional government.

Iraq’s oil production still has not rebounded, and basic services like

electricity are still woefully inadequate. Iraq needs an impartial justice

system. Washington has pressed Baghdad for years to end corruption and build a

representative government. It will need to keep pressing.

After investing billions of dollars, the United States has had more success

rebuilding Iraq’s security forces. But Iraqi and American commanders say these

forces are not ready to fully protect the country against insurgents or

potentially hostile neighbors. There are critical weaknesses in intelligence,

air defenses, artillery and logistics.

The Obama administration was unable to reach a new defense agreement with

Baghdad that would have allowed several thousand American troops to stay behind

as backup. We hope that the Iraqi Army will do better than expected. The

administration must be prepared to offer limited help if the army does get into

serious trouble.

President Obama, who first ran for office campaigning against the war, has never

wavered on his promise to bring the troops home. The last few thousand will be

out of Iraq by year’s end. We celebrate their return. But this country must