|

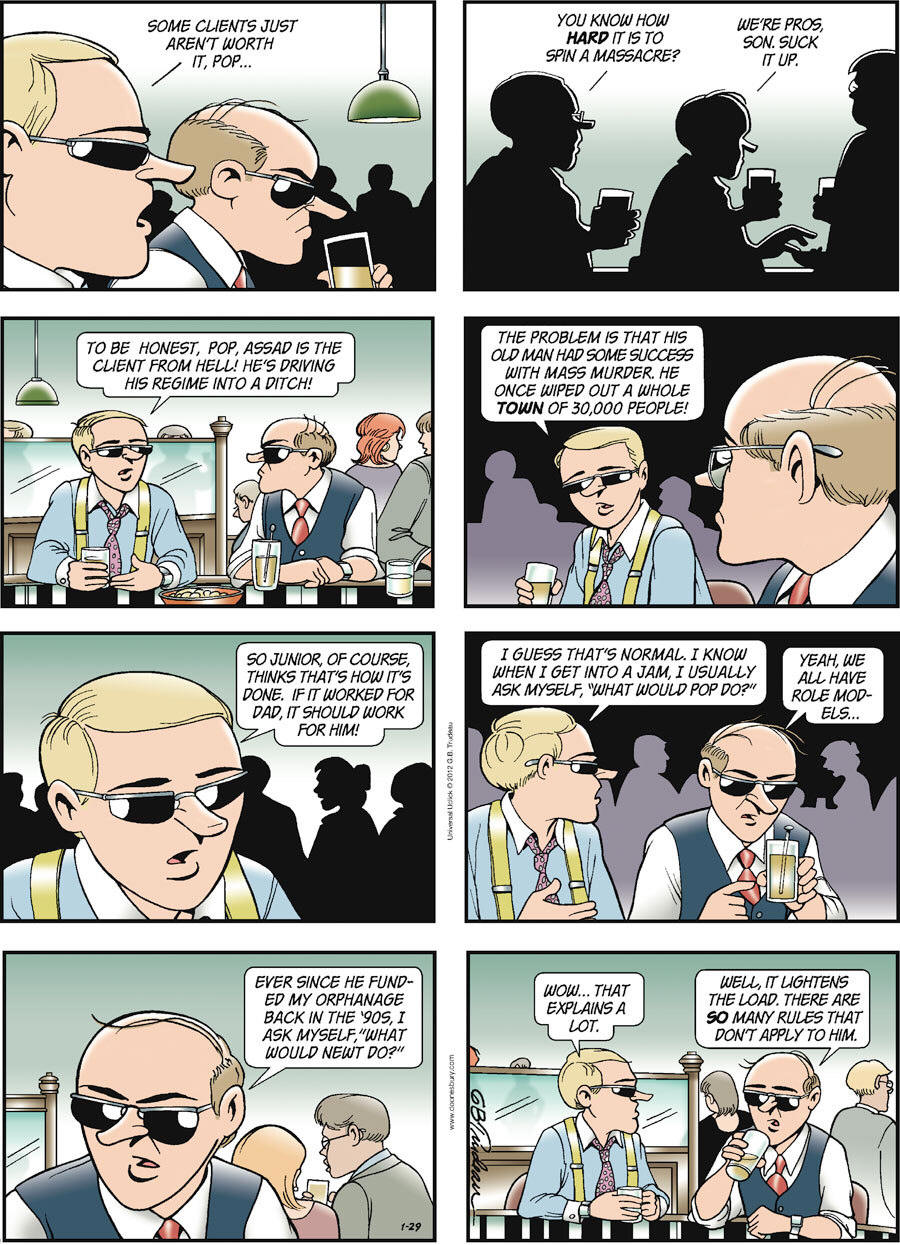

History > 2012 > USA > International (I)

Doonesbury

by Garry Trudeau

Gocomics

January 29, 2012

Tunisia Faces a Balancing Act

of Democracy and Religion

January 30,

2012

The New York Times

By ANTHONY SHADID

TUNIS — The

insults were furious. “Infidel!” and “Apostate!” the religious protesters

shouted at the two men who had come to the courthouse to show their support for

a television director on trial on charges of blasphemy. Fists, then a head butt

followed.

When the scuffle ended a few minutes later, Tunisia, which much of the Arab

world sees as a model for revolution, had witnessed a crucial scene in what some

have cast as a gathering contest for its soul.

“We’re surrendering our right to think and speak differently,” said Hamadi

Redissi, one of the two men, still bearing a scab on his forehead from the

attack last week.

The challenges before Tunisia’s year-old revolution are immense — righting an

ailing economy, drafting a new constitution and recovering from decades of

dictatorship that cauterized civic life. But in the first months of a coalition

government led by the Ennahda Party, seen as one of the most pragmatic of the

region’s Islamist movements, the most emotional of struggles has surged to the

forefront: a fight over the identity of an Arab and Muslim society that its

authoritarian leaders had always cast as adamantly secular.

The popular revolts that began to sweep across the Middle East one year ago have

forced societies like Tunisia’s, removed from the grip of authoritarian leaders

and celebrating an imagined unity, to confront their own complexity. The

aftermath has brought elections in Egypt and Tunisia as well as more decisive

Islamist influence in Morocco, Libya and, perhaps, Syria. The upheaval has given

competing Islamist movements a chance to exert influence and define themselves

locally and on the world stage. It has also given rise to fears, where people in

places like Tunis, a seaside metropolis proud of its cosmopolitanism, worry

about what a revolution they embraced might unleash.

An opposition newspaper has warned darkly of puritanical Islamists declaring

their own fief in some backwater town. Protests convulsed a university in Tunis

over its refusal to let female students take examinations while wearing veils

that concealed their faces. Then there is the trial Mr. Redissi attended on Jan.

23, of a television director who faces as many as five years in prison for

broadcasting the French animated movie “Persepolis,” which contains a brief

scene depicting God that many here have deemed blasphemous.

The trial was postponed again, this time until April. But its symbolism,

precedence and implications infused a secular rally Saturday that drew thousands

to downtown Tunis in one of the biggest demonstrations here in recent months.

“Make a common front against fanaticism,” one banner declared.

Tunisia and Egypt are remarkable for how much freer they have become in the year

since their revolts. They may become more conservative, too, as Islamist parties

inspire and articulate the mores and attitudes of populations that have always

been more traditional than the urban elite. Some here hope the contest may

eventually strike a balance between religious sensitivity and freedom of

expression, an issue as familiar in the West as it is in Muslim countries.

Others worry that debates pressed by the most fervent — over the veil,

sunbathing on beaches and racy fare in the media — may polarize societies and

embroil nascent governments in debates they seem to prefer to avoid.

“It’s like a war of attrition,” said Said Ferjani, a member of Ennahda’s

political bureau, who complained that his party was trapped between two

extremes, the most ardently secular and the religious. “They’re trying not to

let us focus on the real issues.”

Nearly everyone here seems to agree that “Persepolis” was broadcast Oct. 7 on

Nessma TV as a provocation of some sort. Abdelhalim Messaoudi, a journalist at

Nessma, said he envisioned the film, about a girl’s childhood in revolutionary

Iran, “as a pretext to start a conversation.” But many in Tunisia, both pious

and less so, were taken aback by the brief scene in which God was personified —

speaking in Tunisian slang no less. A week later, a crowd of Salafis — the term

used for the most conservative Islamists — attacked the house of Nabil Karoui,

the station’s director, and he was soon charged with libeling religion and

broadcasting information that could “harm public order or good morals.”

The trial, which Human Rights Watch called “a disturbing turn for the nascent

Tunisian democracy,” was originally scheduled for Nov. 16, then postponed until

January.

On Jan. 23, crowds gathered outside the colonnaded courthouse, along a sylvan

street in Tunisia’s old town, known as the casbah. Tempers flared and, in a

scene captured on YouTube, Mr. Redissi and Zied Krichen, the editor of the

newspaper Al Maghreb, tried to leave.

“All I could think was to not look behind me, walk ahead, and not open my

mouth,” said Mr. Krichen, who is 54. A man rushed toward him, hitting him from

behind. When Mr. Redissi, 59, turned to defend his colleague, he was

head-butted. At first, the police did nothing, then helped escort the two men to

a police station down the road.

Mr. Messaoudi, who was sitting at a cafe across the street, was also assaulted.

Two days later, in a statement many secular figures deemed too timid, Samir

Dilou, a government spokesman and a member of Ennahda, reiterated the party’s

view that the film was “a violation of the sacred.” But he condemned the

violence and promised to act. One of the assailants, identified in the video,

was later arrested.

For people like Mr. Messaoudi, though, the incident reflected a months-long

trend of thuggery by Salafis, from an attack on a theater airing a film they

deemed objectionable to their brief control last month over a northern Tunisian

town called Sanjan. Some secular figures acknowledge that Ennahda is embarrassed

by the incidents, loath to be grouped with the Salafis. Others view both as part

of a broader Islamist outlook that celebrates Tunisia’s Muslim identity as a way

to promote a more conservative society.

“Certain Islamist factions want to turn identity into their Trojan horse,” Mr.

Messaoudi said. “They use the pretext of protecting their identity as a way to

crush what we have achieved as a Tunisian society. They want to crush the

pillars of civil society.”

The debates in Tunisia often echo similar confrontations in Turkey, another

country with a long history of secular authoritarian rule now governed by a

party inspired by political Islam. In both, secular elites long considered

themselves a majority and were treated as such by the state. In both, those

elites now recognize themselves as minorities and are often mobilized more by

the threat than the reality of religious intolerance.

Mr. Redissi, a columnist and professor, predicted secular Tunisians might soon

retreat to enclaves.

“We’ve become the ahl al-dhimma,” he said, offering a term in Islamic law to

denote protected minorities in a Muslim state. “It’s like the Middle Ages.”

As in Egypt, the prominence of the Salafis since the revolution has taken many

Tunisians by surprise. Their numbers pale before their brethren in Egypt, but

like them, they are assertive and determined to make their presence felt, often

embarrassing more moderate counterparts like Ennahda and the Muslim Brotherhood.

On Friday, they organized a demonstration in front of the Foreign Ministry in

support of Syrian protesters. For weeks, they held a sit-in at Manouba

University here in Tunis to demand that women in full veils be allowed to take

exams, eventually forcing the campus to close for a time.

“There are red lines not to be crossed,” said Abdel-Qadir al-Hashemi, a

28-year-old Salafi activist who helped organize the protest at Manouba. “The

film ‘Persepolis’ was a provocation, simply a provocation, with the goal of

driving us toward violence.”

A few of his colleagues turned out for the secular protest Saturday.

“Go back to your caves and mind your own business!” someone shouted at them.

They heckled back.

“You lost your daddy, Ben Ali!” one of them taunted, referring to the Tunisian

dictator, President Zine El-Abdine Ben Ali, who was forced into exile in Saudi

Arabia last year.

Even secular figures like Mr. Redissi suggest that Ennahda would rather avoid

the debate over “Persepolis.” He predicted the trial would be postponed until

after the next elections that follow the drafting of the constitution, in a year

or so. Others insisted that Ennahda take a stronger stand against the Salafis

before society became even more polarized.

“I don’t see either action or reaction — where is the government?” asked Ahmed

Ounaïes, a former diplomat who briefly served as foreign minister after the

revolution. “What is Ennahda’s concept of Tunisia of tomorrow? It hasn’t made

that clear.”

In Ennahda’s offices, Mr. Ferjani shook his head. He complained that the case

had been “blown out of proportion,” that media were recklessly fueling the

debate and that the forces of the old government were inciting Salafis to

tarnish Ennahda. But he conceded that the line between freedom of expression and

religious sensitivity would not be drawn soon.

“The struggle is philosophical,” he said, “and it will go on and on and on.”

Tunisia Faces a Balancing Act of Democracy and Religion, NYT, 30.1.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/31/world/africa/tunisia-navigates-a-democratic-path-tinged-with-religion.html

European Leaders Agree to New Budget Discipline

Measures

January 30,

2012

The New York Times

By STEPHEN CASTLE and JAMES KANTER

BRUSSELS —

All but two European Union countries agreed Monday to new and tougher measures

to enforce budget discipline in the euro zone, but the bloc still showed few

signs of producing a comprehensive solution for the sovereign debt crisis or a

credible plan to revive fragile economies across Europe’s weakened Mediterranean

tier.

The meeting of 27 European Union heads of state and government here in Brussels

was aimed at completing the text of a so-called fiscal compact for the 17

nations relying on or intending to join the euro zone — with only Britain and

the Czech Republic opting not to adopt the measures.

After a meeting lasting seven hours, the leaders also issued a declaration

calling for a new push to restart growth and combat joblessness across the

Continent.

But a number of politicians and analysts said the pledge by the European leaders

to create new jobs was mostly empty, and others complained that the proposed

rules to keep deficits under control contained little to actually help nations

with high borrowing costs.

The summit declaration also skirted the continuing problems in Greece, where a

second bailout is being held up by the inability of the government in Athens to

complete a deal with private holders of Greek bonds over the losses they should

accept.

Until Athens and its private-sector creditors can agree on a $132 billion

writedown on Greek government debt, the International Monetary Fund and the

European Union are not prepared to sign off on a further bailout. Chancellor

Angela Merkel of Germany said the Greek situation would not be addressed until

after representatives of Greece’s so-called troika of creditors — the European

Union, the I.M.F. and the European Central Bank — report back on their

investigation into what will be needed for Greece to manage its finances on its

own.

Nicolas Sarkozy, the French president, told a news conference at the end of the

summit that there would be a “definitive agreement” on the private sector’s

involvement in reducing Greek debt in coming days. After Monday night’s summit

meeting, informal talks continued between the Greek prime minister, Lucas

Papademos, and European officials.

Despite the various other problems to deal with, an agreement on the fiscal

compact could clear the way for Germany to accept stronger efforts by the

European Central Bank to support ailing countries and a more comprehensive

bailout fund aimed at protecting Italy and Spain against the risk of default.

“It is an important step forward to a stability union,” Mrs. Merkel told

reporters. “For those looking at the union and the euro from the outside, it is

a very important to show this commitment.” Britain, which clashed openly with

France and Germany last month over the pact, did not give any ground Monday and

was joined by the Czech Republic, which also elected to stay outside.

“We are not signing this treaty,” David Cameron, the British prime minister,

said. “We are not ratifying it. And it places no obligations” on the United

Kingdom, he said.

He added: “Our national interest is that these countries get on and sort out the

mess that is the euro.”

Mr. Sarkozy sounded philosophical about the Britons’ intransigence. “There are

different degrees of integration and everyone is free to choose where they

stand,” he said.

While European leaders agreed to bring a permanent bailout fund into existence

earlier than previously foreseen, they postponed any final decisions on its

ultimate size and how it will be financed. The International Monetary Fund has

been pressing Europe to commit enough money to provide a credible backstop that

would insure that Italy and Spain could pay their bills and continue to finance

their debts.

Germany backed away from a suggestion that it wanted the government in Athens to

cede temporarily control over tax and spending decisions to a new, all-powerful,

budget commissioner before it can secure further bailouts. Italy won its battle

to restrict the scope of the fiscal compact, which calls for making it easier to

impose sanctions against countries that break European Union budget rules. The

text said the compact would make it harder to block sanctions against countries

that exceed annual deficit targets but that the same tough system would not

apply to nations with excessive overall debt, like Italy.

The compact will come into force in those nations that agree to its terms once

12 euro zone nations have ratified it. That would prevent the project being held

up if one or two nations hold referendums on the deal.

Still, impatience with the German focus on belt-tightening loomed large over the

summit meeting.

“You don’t have to be an economics professor to know that if you have zero

growth you are not going to sort things out,” said Martin Schulz, the president

of the European Parliament. Critics of austerity point to Greece, which is being

strangled by a vicious cycle of deficit cutting, declining tax revenues and more

budget cutting, while making little if any progress on its overall budget

deficit.

Guy Verhofstadt, leader of the centrist liberal and democrat group, and a former

prime minister of Belgium, took a similar stand.

“The new agreement consolidates fiscal discipline but omits completely to

address the other side of the coin — that of solidarity and investment that will

create jobs and growth,” Mr. Verhofstadt said. “E.U. leaders should act instead

of producing more paper.”

European Leaders Agree to New Budget Discipline Measures, NYT, 30.1.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/31/world/europe/eu-leaders-fall-short-of-far-reaching-debt-solution.html

Citing Violence, Arab League Suspends Monitoring in

Syria

January 28,

2012

The New York Times

By NADA BAKRI and KAREEM FAHIM

BEIRUT,

Lebanon — The Arab League suspended its monitoring mission in Syria on Saturday

after a sharp escalation of violence there, as government armed forces battled

opposition fighters across the country.

Intensified fighting in recent weeks has added weight to the belief, expressed

by Arab League officials and others, that Syria’s civil conflict has moved well

beyond the peaceful demonstration movement that began 10 months ago into an

armed struggle against President Bashar al-Assad’s government in several parts

of the country. Since its start, the upheaval has claimed more than 5,400 lives,

according to the United Nations.

The head of the Arab League, Nabil al-Araby, said in a statement Saturday that

after discussions with Arab foreign ministers, the 22-member body had decided to

suspend the monitors’ mission in Syria because of “a severe deterioration in the

situation and the continued use of violence.” A final decision about the

mission’s future is due in the coming days.

Mr. Araby blamed the Syrian government for the bloodshed, saying that it has

decided “to escalate the military option in complete violation of its

commitments to the Arab plan” and added that “innocent citizens” were the

victims. The Syrian government has denied that it is facing a popular uprising,

insisting instead that it has been battling armed terrorist groups funded by

foreign interests.

Mr. Araby’s deputy, Ahmed Ben Heli, told reporters at the League’s headquarters

in Cairo that about 100 monitors would remain in Damascus in the meantime.

The monitoring mission’s effectiveness has come under increasingly sharp

questioning since it began a month ago, and on Tuesday several gulf countries

ended their participation in it. The head of the monitoring mission, Lt. Gen.

Muhammad Ahmed al-Dabi, of Sudan, called on all Syrian parties to halt violence

on Friday.

The mission’s mandate was to observe the implementation of a peace plan and was

extended for a second month. The suspension came a week after the Arab League

called on President Assad to step down and said it was going to take an Arab

peace proposal to the United Nations to help end violence in Syria. That plan

would have Mr. Assad hand power to a vice president while an interim government

was formed. Mr. Araby and other Arab League officials were traveling to New York

on Saturday in preparation to meet with United Nations officials.

Activists and residents have reported heavy clashes between security forces

loyal to the government and opposition armed fighters on the outskirts of

Damascus and in southern Syria.

The Arab League observers traveled to the town of Rankous on Saturday morning, a

restive city near the Lebanese border from which the government has had to

withdraw its troops. The observers never made it inside. One of the members of

the team said that Syrian Army officers had told them it was too dangerous

because snipers and gunmen were menacing the town.

During a visit to Rankous by reporters after the observers left, residents and

fighters who said they were with the Free Syrian Army opposition militia told a

different story. They said that the army, which had surrounded the town of

23,000 people with tanks, had been shelling for days. Most of the residents had

fled, but about 50 families remained in the town, they said.

Soon after a group of reporters arrived in the center of Rankous, tanks could be

seen taking up positions on the outskirts. Within about an hour, shelling and

heavy machine gun fire could be heard. The Free Syrian Army fighters said

government snipers were surrounding the town. Bullets whistled by a house where

they had taken up positions.

By nightfall, at a spot on the edge of the town where observers had visited

earlier in the morning and seen nothing, several tanks had moved into place,

tightening a cordon around Rankous.

“It’s under the government’s full siege now,” said Col. Ammar Alwawi, an Free

Syrian Army official speaking by phone from Turkey. “If the regime continues the

use of force there, there will be a massacre. They can’t enter. There are

civilians there who didn’t leave their houses.”

Nada Bakri reported from Beirut, and Kareem Fahim from Rankous, Syria.

Citing Violence, Arab League Suspends Monitoring in Syria, NYT, 28.1.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/29/world/middleeast/arab-league-suspends-its-monitoring-in-syria.html

Iran Says It May Cut Off Its Oil Exports to Europe

January 26,

2012

The New York Times

By RICK GLADSTONE and J. DAVID GOODMAN

Iran struck

a combative tone Thursday in its confrontation with the West over the nuclear

issue, threatening to terminate oil exports to European nations even before

their embargo takes effect this summer. But its president also acknowledged that

the regimen of punitive sanctions imposed on Iran, which he had long dismissed

as insignificant, were hurting ordinary Iranians.

“It is a big lie that they are not targeting the people,” President Mahmoud

Ahmadinejad said of the sanctions in a speech reported by Iran’s official

Islamic Republic News Agency. Directing his ire at the Western powers that have

imposed the sanctions, which have constricted Iran’s ability to sell oil and

conduct international financial transactions, he said, “You are the real enemy

of people and are putting pressure on them.”

Political analysts said Mr. Ahmadinejad’s acknowledgment of sanction pain, in an

otherwise bellicose speech, was a departure from the government depiction of

Iran as an immune fortress. They said it may reflect the harsh reality that the

corrosive effect of sanctions on Iran’s currency, exports and employment could

no longer be ignored by Iranian politicians facing their audience at home.

Just one day earlier, Mr. Ahmadinejad was forced to reverse himself and approve

a sharp rise in bank deposit interest rates as part of an effort to stop a

plunge in the value of Iran’s currency, the rial, which accelerated after the

European Union announced the oil embargo on Monday. Many Iranians have been

seeking to sell rials for gold and foreign currencies, fearful that their own

money is becoming worthless.

“Iran’s official narrative has long been that sanctions have a negligible

impact, and in fact have been helpful in making the country economically

self-sufficient,” said Karim Sadjadpour, an Iran expert at the Carnegie

Endowment for International Peace in Washington. “While it may be tough to

suddenly pivot from that and say that sanctions are the cause of Iran’s economic

malaise, it’s no longer possible to dismiss the impact of sanctions when

everyone in Iran has been affected by the country’s ongoing currency crisis.”

The uranium enrichment program at the heart of the sanctions has become the most

urgent point of contention between Iran and the West, which has long suspected

that the Iranians are working to build a nuclear weapon despite their repeated

denials. Iran has said it is enriching uranium for civilian energy and medical

purposes. Israel, which considers Iran its most dangerous adversary, has hinted

at the possibility of a pre-emptive military strike against Iran’s nuclear

facilities.

In his speech, at an industrial project ceremony in southeast Iran, Mr.

Ahmadinejad expressed his country’s willingness to re-engage with the Western

powers in negotiations over its uranium enrichment program, as his foreign

minister, Ali Akbar Salehi, had said last week.

But Mr. Ahmadinejad also accused them of insincerity in their own offers to

resume the talks, which were suspended a year ago.

“I admonish you to pave the right track and do not make any excuses while the

time is ripe for negotiations,” Mr. Ahmadinejad said. “Be friendly to Iranians

because it is no longer a time of making noises and bullying others in the

world.”

A more belligerent warning came from Iran’s Parliament, where lawmakers were

working on a plan to stop Iran’s oil exports to Europe in retaliation for the

embargo, which is to begin July 1.

“Europe will burn in the fire of Iran’s oil wells,” Nasser Soudani, a member of

the Parliament’s energy committee, said in remarks carried by the Fars News

Agency.

Under their plan, he said, “All European countries that made Iran the target of

their sanctions will not be able to buy even one drop of oil from Iran.”

Mr. Soudani further predicted that the Europeans, who are heavily reliant on

imported oil, would have no choice but to renounce the embargo because

“abandoning Iran’s oil would mean the extinguishing of the candles of their

economic lives.”

His remarks may have been intended to rattle the global oil market, where the

price of crude has sometimes jumped in response to previous threats by Iran, the

world’s fourth-largest oil exporter.

But crude prices, which have hovered around the $100-per-barrel range, were

little changed on Thursday, partly reflecting what oil traders said was ample

evidence that other producers — notably Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Libya — could

compensate for any absence of Iranian oil.

Steven

Erlanger contributed reporting from Paris.

Iran Says It May Cut Off Its Oil Exports to Europe?, NYT, 26.1.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/27/world/middleeast/ahmadinejad-says-iran-is-ready-for-nuclear-talks.html

Will

Israel Attack Iran?

January 25,

2012

The New York Times

By RONEN BERGMAN

As the

Sabbath evening approached on Jan. 13, Ehud Barak paced the wide living-room

floor of his home high above a street in north Tel Aviv, its walls lined with

thousands of books on subjects ranging from philosophy and poetry to military

strategy. Barak, the Israeli defense minister, is the most decorated soldier in

the country’s history and one of its most experienced and controversial

politicians. He has served as chief of the general staff for the Israel Defense

Forces, interior minister, foreign minister and prime minister. He now faces,

along with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and 12 other members of Israel’s

inner security cabinet, the most important decision of his life — whether to

launch a pre-emptive attack against Iran. We met in the late afternoon, and our

conversation — the first of several over the next week — lasted for two and a

half hours, long past nightfall. “This is not about some abstract concept,”

Barak said as he gazed out at the lights of Tel Aviv, “but a genuine concern.

The Iranians are, after all, a nation whose leaders have set themselves a

strategic goal of wiping Israel off the map.”

When I mentioned to Barak the opinion voiced by the former Mossad chief Meir

Dagan and the former chief of staff Gabi Ashkenazi — that the Iranian threat was

not as imminent as he and Netanyahu have suggested and that a military strike

would be catastrophic (and that they, Barak and Netanyahu, were cynically

looking to score populist points at the expense of national security), Barak

reacted with uncharacteristic anger. He and Netanyahu, he said, are responsible

“in a very direct and concrete way for the existence of the State of Israel —

indeed, for the future of the Jewish people.” As for the top-ranking military

personnel with whom I’ve spoken who argued that an attack on Iran was either

unnecessary or would be ineffective at this stage, Barak said: “It’s good to

have diversity in thinking and for people to voice their opinions. But at the

end of the day, when the military command looks up, it sees us — the minister of

defense and the prime minister. When we look up, we see nothing but the sky

above us.”

Netanyahu and Barak have both repeatedly stressed that a decision has not yet

been made and that a deadline for making one has not been set. As we spoke,

however, Barak laid out three categories of questions, which he characterized as

“Israel’s ability to act,” “international legitimacy” and “necessity,” all of

which require affirmative responses before a decision is made to attack:

1. Does Israel have the ability to cause severe damage to Iran’s nuclear sites

and bring about a major delay in the Iranian nuclear project? And can the

military and the Israeli people withstand the inevitable counterattack?

2. Does Israel have overt or tacit support, particularly from America, for

carrying out an attack?

3. Have all other possibilities for the containment of Iran’s nuclear threat

been exhausted, bringing Israel to the point of last resort? If so, is this the

last opportunity for an attack?

For the first time since the Iranian nuclear threat emerged in the mid-1990s, at

least some of Israel’s most powerful leaders believe that the response to all of

these questions is yes.

At various points in our conversation, Barak underscored that if Israel or the

rest of the world waits too long, the moment will arrive — sometime in the

coming year, he says — beyond which it will no longer be possible to act. “It

will not be possible to use any surgical means to bring about a significant

delay,” he said. “Not for us, not for Europe and not for the United States.

After that, the question will remain very important, but it will become purely

theoretical and pass out of our hands — the statesmen and decision-makers — and

into yours — the journalists and historians.”

Moshe Ya’alon, Israel’s vice prime minister and minister of strategic affairs,

is the third leg in the triangle supporting a very aggressive stance toward

Iran. When I spoke with him on the afternoon of Jan. 18, the same day that Barak

stated publicly that any decision to strike pre-emptively was “very far off,”

Ya’alon, while reiterating that an attack was the last option, took pains to

emphasize Israel’s resolve. “Our policy is that in one way or another, Iran’s

nuclear program must be stopped,” he said. “It is a matter of months before the

Iranians will be able to attain military nuclear capability. Israel should not

have to lead the struggle against Iran. It is up to the international community

to confront the regime, but nevertheless Israel has to be ready to defend

itself. And we are prepared to defend ourselves,” Ya’alon went on, “in any way

and anywhere that we see fit.”

For years, Israeli and American intelligence agencies assumed that if Iran were

to gain the ability to build a bomb, it would be a result of its relationship

with Russia, which was building a nuclear reactor for Iran at a site called

Bushehr and had assisted the Iranians in their missile-development program.

Throughout the 1990s, Israel and the United States devoted vast resources to

weakening the nuclear links between Russia and Iran and applied enormous

diplomatic pressure on Russia to cut off the relationship. Ultimately, the

Russians made it clear that they would do all in their power to slow down

construction on the Iranian reactor and assured Israel that even if it was

completed (which it later was), it wouldn’t be possible to produce the refined

uranium or plutonium needed for nuclear weapons there.

But the Russians weren’t Iran’s only connection to nuclear power. Robert

Einhorn, currently special adviser for nonproliferation and arms control at the

U. S. State Department, told me in 2003: “Both countries invested huge efforts,

overt and covert, in order to find out what exactly Russia was supplying to Iran

and in attempts to prevent that supply. We were convinced that this was the main

path taken by Iran to secure the Doomsday weapon. But only very belatedly did it

emerge that if Iran one day achieved its goal, it will not be by the Russian

path at all. It made its great advance toward nuclear weaponry on another path

altogether — a secret one — that was concealed from our sight.”

That secret path was Iran’s clandestine relationship with the network of Abdul

Qadeer Khan, the father of Pakistan’s atom bomb. Cooperation between American,

British and Israeli intelligence services led to the discovery in 2002 of a

uranium-enrichment facility built with Khan’s assistance at Natanz, 200 miles

south of Tehran. When this information was verified, a great outcry erupted

throughout Israel’s military and intelligence establishment, with some demanding

that the site be bombed at once. Prime Minister Ariel Sharon did not authorize

an attack. Instead, information about the site was leaked to a dissident Iranian

group, the National Resistance Council, which announced that Iran was building a

centrifuge installation at Natanz. This led to a visit to the site by a team of

inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency, who were surprised to

discover that Iran was well on its way to completing the nuclear fuel cycle —

the series of processes for the enrichment of uranium that is a critical stage

in producing a bomb.

Despite the discovery of the Natanz site and the international sanctions that

followed, Israeli intelligence reported in early 2004 that Iran’s nuclear

project was still progressing. Sharon assigned responsibility for putting an end

to the program to Meir Dagan, then head of the Mossad. The two knew each other

from the 1970s, when Sharon was the general in charge of the southern command of

the Israel Defense Forces and Dagan was a young officer whom he put in charge of

a top-secret unit whose purpose was the systematic assassination of Palestine

Liberation Organization militiamen in the Gaza Strip. As Sharon put it at the

time: “Dagan’s specialty is separating an Arab from his head.”

Sharon granted the Mossad virtually unlimited funds and powers to “stop the

Iranian bomb.” As one recently retired senior Mossad officer told me: “There was

no operation, there was no project that was not carried out because of a lack of

funding.”

At a number of secret meetings with U.S. officials between 2004 and 2007, Dagan

detailed a “five-front strategy” that involved political pressure, covert

measures, counterproliferation, sanctions and regime change. In a secret cable

sent to the U.S. in August 2007, he stressed that “the United States, Israel and

like-minded countries must push on all five fronts in a simultaneous joint

effort.” He went on to say: “Some are bearing fruit now. Others” — and here he

emphasized efforts to encourage ethnic resistance in Iran — “will bear fruit in

due time, especially if they are given more attention.”

From 2005 onward, various intelligence arms and the U.S. Treasury, working

together with the Mossad, began a worldwide campaign to locate and sabotage the

financial underpinnings of the Iranian nuclear project. The Mossad provided the

Americans with information on Iranian firms that served as fronts for the

country’s nuclear acquisitions and financial institutions that assisted in the

financing of terrorist organizations, as well as a banking front established by

Iran and Syria to handle all of these activities. The Americans subsequently

tried to persuade several large corporations and European governments —

especially France, Germany and Britain — to cease cooperating with Iranian

financial institutions, and last month the Senate approved sanctions against

Iran’s central bank.

In addition to these interventions, as well as to efforts to disrupt the supply

of nuclear materials to Iran, since 2005 the Iranian nuclear project has been

hit by a series of mishaps and disasters, for which the Iranians hold Western

intelligence services — especially the Mossad — responsible. According to the

Iranian media, two transformers blew up and 50 centrifuges were ruined during

the first attempt to enrich uranium at Natanz in April 2006. A spokesman for the

Iranian Atomic Energy Council stated that the raw materials had been “tampered

with.” Between January 2006 and July 2007, three airplanes belonging to Iran’s

Revolutionary Guards crashed under mysterious circumstances. Some reports said

the planes had simply “stopped working.” The Iranians suspected the Mossad, as

they did when they discovered that two lethal computer viruses had penetrated

the computer system of the nuclear project and caused widespread damage,

knocking out a large number of centrifuges.

In January 2007, several insulation units in the connecting fixtures of the

centrifuges, which were purchased from a middleman on the black market in

Eastern Europe, turned out to be flawed and unusable. Iran concluded that some

of the merchants were actually straw companies that were set up to outfit the

Iranian nuclear effort with faulty parts.

Of all the covert operations, the most controversial have been the

assassinations of Iranian scientists working on the nuclear project. In January

2007, Dr. Ardeshir Husseinpour, a 44-year-old nuclear scientist working at the

Isfahan uranium plant, died under mysterious circumstances. The official

announcement of his death said he was asphyxiated “following a gas leak,” but

Iranian intelligence is convinced that he was the victim of an Israeli

assassination.

Massoud Ali Mohammadi, a particle physicist, was killed in January 2010, when a

booby-trapped motorcycle parked nearby exploded as he was getting into his car.

(Some contend that Mohammadi was not killed by the Mossad, but by Iranian agents

because of his supposed support for the opposition leader Mir Hussein Moussavi.)

Later that year, on Nov. 29, a manhunt took place in the streets of Tehran for

two motorcyclists who had just blown up the cars of two senior figures in the

Iranian nuclear project, Majid Shahriari and Fereydoun Abbasi-Davani. The

motorcyclists attached limpet mines (also known as magnet bombs) to the cars and

then sped away. Shahriari was killed by the blast in his Peugeot 405, but

Abbassi-Davani and his wife managed to escape their car before it exploded.

Following this assassination attempt, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad appointed

Abbassi-Davani vice president of Iran and head of the country’s atomic agency.

Today he is heavily guarded wherever he goes, as is the scientific head of the

nuclear project, Mohsin Fakhri-Zadeh, whose lectures at Tehran University were

discontinued as a precautionary measure.

This past July, a motorcyclist ambushed Darioush Rezaei Nejad, a nuclear

physicist and a researcher for Iran’s Atomic Energy Organization, as he sat in

his car outside his house. The biker drew a pistol and shot the scientist dead

through the car window.

Four months later, in November, a huge explosion occurred at a Revolutionary

Guards base 30 miles west of Tehran. The cloud of smoke was visible from the

city, where residents could feel the ground shake and hear their windows rattle,

and satellite photos showed that almost the entire base was obliterated. Brig.

Gen. Hassan Moghaddam, head of the Revolutionary Guards’ missile-development

division, was killed, as were 16 of his personnel. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei,

Iran’s spiritual leader, paid respect by coming to the funeral service for the

general and visiting the widow at her home, where he called Moghaddam a martyr.

Just this month, on Jan. 11, two years after his colleague and friend Massoud

Ali Mohammadi was killed, a deputy director at the Natanz uranium-enrichment

facility named Mostafa Ahmadi-Roshan left his home and headed for a laboratory

in downtown Tehran. A few months earlier, a photograph of him accompanying

Ahmadinejad on a tour of nuclear installations appeared in newspapers across the

globe. Two motorcyclists drove up to his car and attached a limpet mine that

killed him on the spot.

Israelis cannot enter Iran, so Israel, Iranian officials believe, has devoted

huge resources to recruiting Iranians who leave the country on business trips

and turning them into agents. Some have been recruited under a false flag,

meaning that the organization’s recruiters pose as other nationalities, so that

the Iranian agents won’t know they are on the payroll of “the Zionist enemy,” as

Israel is called in Iran. Also, as much as possible, the Mossad prefers to carry

out its violent operations based on the blue-and-white principle, a reference to

the colors of Israel’s national flag, which means that they are executed only by

Israeli citizens who are regular Mossad operatives and not by assassins

recruited in the target country. Operating in Iran, however, is impossible for

the Mossad’s sabotage-and-assassination unit, known as Caesarea, so the

assassins must come from elsewhere. Iranian intelligence believes that over the

last several years, the Mossad has financed and armed two Iranian opposition

groups, the Muhjahedin Khalq (MEK) and the Jundallah, and has set up a forward

base in Kurdistan to mobilize the Kurdish minority in Iran, as well as other

minorities, training some of them at a secret base near Tel Aviv.

Officially, Israel has never admitted any involvement in these assassinations,

and after Secretary of State Hillary Clinton spoke out against the killing of

Ahmadi-Roshan this month, President Shimon Peres said he had no knowledge of

Israeli involvement. The Iranians vowed revenge after the murder, and on Jan.

13, as I spoke with Ehud Barak at his home in Tel Aviv, the country’s

intelligence community was conducting an emergency operation to thwart a joint

attack by Iran and Hezbollah against Israeli and Jewish targets in Bangkok.

Local Thai forces, reportedly acting on information supplied by the Mossad,

raided a Hezbollah hideout in Bangkok and later apprehended a member of the

terror cell as he tried to flee the country. The prisoner reportedly confessed

that he and his fellow cell members intended to blow up the Israeli Embassy and

a synagogue.

Meir Dagan, while not taking credit for the assassinations, has praised the hits

against Iranian scientists attributed to the Mossad, saying that beyond “the

removal of important brains” from the project, the killings have brought about

what is referred to in the Mossad as white defection — in other words, the

Iranian scientists are so frightened that many have requested to be transferred

to civilian projects. “There is no doubt,” a former top Mossad official told me

over breakfast on Jan. 11, just a few hours after news of Ahmadi-Roshan’s

assassination came from Tehran, “that being a scientist in a prestigious nuclear

project that is generously financed by the state carries with it advantages like

status, advancement, research budgets and fat salaries. On the other hand, when

a scientist — one who is not a trained soldier or used to facing

life-threatening situations, who has a wife and children — watches his

colleagues being bumped off one after the other, he definitely begins to fear

that the day will come when a man on a motorbike knocks on his car window.”

As we spoke, a man approached and, having recognized me as a journalist who

reports on these issues, apologized before asking: “When is the war going to

break out? When will the Iranians bomb us?” The Mossad official smiled as I

tried to reassure the man that we wouldn’t be nuked tomorrow. Similar scenes

occur almost every day — Israelis watch the news, have heard that bomb shelters

are being prepared, know that Israel test-fired a missile into the sea two

months ago — and a kind of panic has begun to overtake Israeli society, anxiety

that missiles will start raining down soon.

Dagan believes that his five-fronts strategy has succeeded in significantly

delaying Iran’s progress toward developing nuclear weapons; specifically “the

use of all the weapons together,” he told me and a small group of Israeli

journalists early last year. “In the mind of the Iranian citizen, a link has

been created between his economic difficulties and the nuclear project. Today in

Iran, there is a profound internal debate about this matter, which has divided

the Iranian leadership.” He beamed when he added, “It pleases me that the

timeline of the project has been pushed forward several times since 2003 because

of these mysterious disruptions.”

Barak and Netanyahu are less convinced of the Mossad’s long-term success. From

the beginning of their terms (Barak as defense minister in June 2007, Netanyahu

as prime minister in March 2009), they have held the opinion that Israel must

have a military option ready in case covert efforts fail. Barak ordered

extensive military preparations for an attack on Iran that continue to this day

and have become more frequent in recent months. He was not alone in fearing that

the Mossad’s covert operations, combined with sanctions, would not be

sufficient. The I.D.F. and military intelligence have also experienced waning

enthusiasm. Three very senior military intelligence officers, one who is still

serving and two who retired recently, told me that with all due respect for

Dagan’s success in slowing down the Iranian nuclear project, Iran was still

making progress. One recalled Israel’s operations against Iraq’s nuclear program

in the late 1970s, when the Mossad eliminated some of the scientists working on

the project and intimidated others. On the night of April 6, 1979, a team of

Mossad operatives entered the French port town La Seyne-sur-Mer and blew up a

shipment necessary for the cooling system of the Iraqi reactor’s core that was

being manufactured in France. The French police found no trace of the

perpetrators. An unknown organization for the defense of the environment claimed

responsibility.

The attack was successful, but a year later the damage was repaired and further

sabotage efforts were thwarted. The project advanced until late in 1980, when it

was discovered that a shipment of fuel rods containing enriched uranium had been

sent from France to Baghdad, and they were about to be fed into the reactor’s

core. Israel determined that it had no other option but to launch Operation

Opera, a surprise airstrike in June 1981 on the Tammuz-Osirak reactor just

outside Baghdad.

Similarly, Dagan’s critics say, the Iranians have managed to overcome most

setbacks and to replace the slain scientists. According to latest intelligence,

Iran now has some 10,000 functioning centrifuges, and they have streamlined the

enrichment process. Iran today has five tons of low-grade fissile material,

enough, when converted to high-grade material, to make about five to six bombs;

it also has about 175 pounds of medium-grade material, of which it would need

about 500 pounds to make a bomb. It is believed that Iran’s nuclear scientists

estimate that it will take them nine months, from the moment they are given the

order, to assemble their first explosive device and another six months to be

able to reduce it to the dimensions of a payload for their Shahab-3 missiles,

which are capable of reaching Israel. They are holding the fissile material at

sites across the country, most notably at the Fordo facility, near the holy city

Qom, in a bunker that Israeli intelligence estimates is 220 feet deep, beyond

the reach of even the most advanced bunker-busting bombs possessed by the United

States.

Barak serves as the senior Israeli representative in the complex dialogue with

the United States on this topic. He disagrees with the parallels that some

Israeli politicians, mainly his boss, Netanyahu, draw between Ahmadinejad and

Adolf Hitler, and espouses far more moderate views. “I accept that Iran has

other reasons for developing nuclear bombs, apart from its desire to destroy

Israel, but we cannot ignore the risk,” he told me earlier this month. “An

Iranian bomb would ensure the survival of the current regime, which otherwise

would not make it to its 40th anniversary in light of the admiration that the

young generation in Iran has displayed for the West. With a bomb, it would be

very hard to budge the administration.” Barak went on: “The moment Iran goes

nuclear, other countries in the region will feel compelled to do the same. The

Saudi Arabians have told the Americans as much, and one can think of both Turkey

and Egypt in this context, not to mention the danger that weapons-grade

materials will leak out to terror groups.

“From our point of view,” Barak said, “a nuclear state offers an entirely

different kind of protection to its proxies. Imagine if we enter another

military confrontation with Hezbollah, which has over 50,000 rockets that

threaten the whole area of Israel, including several thousand that can reach Tel

Aviv. A nuclear Iran announces that an attack on Hezbollah is tantamount to an

attack on Iran. We would not necessarily give up on it, but it would definitely

restrict our range of operations.”

At that point Barak leaned forward and said with the utmost solemnity: “And if a

nuclear Iran covets and occupies some gulf state, who will liberate it? The

bottom line is that we must deal with the problem now.”

He warned that no more than one year remains to stop Iran from obtaining nuclear

weaponry. This is because it is close to entering its “immunity zone” — a term

coined by Barak that refers to the point when Iran’s accumulated know-how, raw

materials, experience and equipment (as well as the distribution of materials

among its underground facilities) — will be such that an attack could not derail

the nuclear project. Israel estimates that Iran’s nuclear program is about nine

months away from being able to withstand an Israeli attack; America, with its

superior firepower, has a time frame of 15 months. In either case, they are

presented with a very narrow window of opportunity. One very senior Israeli

security source told me: “The Americans tell us there is time, and we tell them

that they only have about six to nine months more than we do and that therefore

the sanctions have to be brought to a culmination now, in order to exhaust that

track.”

Many European analysts and some intelligence agencies have in the past responded

to Israel’s warnings with skepticism, if not outright suspicion. Some have

argued that Israel has intentionally exaggerated its assessments to create an

atmosphere of fear that would drag Europe into its extensive economic campaign

against Iran, a skepticism bolstered by the C.I.A.’s incorrect assessment about

Iraqi W.M.D. before to the Iraq war.

Israel’s discourse with the United States on the subject of Iran’s nuclear

project is more significant, and more fraught, than it is with Europe. The U.S.

has made efforts to stiffen sanctions against Iran and to mobilize countries

like Russia and China to apply sanctions in exchange for substantial American

concessions. But beneath the surface of this cooperation, there are signs of

mutual suspicion. As one senior American official wrote to the State Department

and the Pentagon in November 2009, after an Israeli intelligence projection that

Iran would have a complete nuclear arsenal by 2012: “It is unclear if the

Israelis firmly believe this or are using worst-case estimates to raise greater

urgency from the United States.”

For their part, the Israelis suspect that the Obama administration has abandoned

any aggressive strategy that would ensure the prevention of a nuclear Iran and

is merely playing a game of words to appease them. The Israelis find evidence of

this in the shift in language used by the administration, from “threshold

prevention” — meaning American resolve to stop Iran from having a nuclear-energy

program that could allow for the ability to create weapons — to “weapons

prevention,” which means the conditions can exist, but there is an American

commitment to stop Iran from assembling an actual bomb.

“I fail to grasp the Americans’ logic,” a senior Israeli intelligence source

told me. “If someone says we’ll stop them from getting there by praying for more

glitches in the centrifuges, I understand. If someone says we must attack soon

to stop them, I get it. But if someone says we’ll stop them after they are

already there, that I do not understand.”

Over the past year, Western intelligence agencies, in particular the C.I.A.,

have moved closer to Israel’s assessments of the Iranian nuclear project.

Defense Secretary Leon Panetta expressed this explicitly when he said that Iran

would be able to reach nuclear-weapons capabilities within a year. The

International Atomic Energy Agency published a scathing report stating that Iran

was in breach of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty and was possibly trying to

develop nuclear weapons. Emboldened by this newfound accord, Israel’s leaders

have adopted a harsher tone against Iran. Ya’alon, the deputy prime minister,

told me in October: “We have had some arguments with the U.S. administration

over the past two years, but on the Iranian issue we have managed to close the

gaps to a certain extent. The president’s statements at his last meeting with

the prime minister — that ‘we are committed to prevent ’ and ‘all the options

are on the table’ — are highly important. They began with the sanctions too

late, but they have moved from a policy of engagement to a much more active

(sanctions) policy against Iran. All of these are positive developments.” On the

other hand, Ya’alon sighed as he admitted: “The main arguments are ahead of us.

This is clear.”

Now that the facts have been largely agreed upon, the arguments Ya’alon

anticipates are those that will stem from the question of how to act — and what

will happen if Israel decides that the moment for action has arrived. The most

delicate issue between the two countries is what America is signaling to Israel

and whether Israel should inform America in advance of a decision to attack.

Matthew Kroenig is the Stanton Nuclear Security Fellow at the Council on Foreign

Relations and worked as a special adviser in the Pentagon from July 2010 to July

2011. One of his tasks was defense policy and strategy on Iran. When I spoke

with Kroenig last week, he said: “My understanding is that the United States has

asked Israel not to attack Iran and to provide Washington with notice if it

intends to strike. Israel responded negatively to both requests. It refused to

guarantee that it will not attack or to provide prior notice if it does.”

Kroenig went on, “My hunch is that Israel would choose to give warning of an

hour or two, just enough to maintain good relations between the countries but

not quite enough to allow Washington to prevent the attack.” Kroenig said Israel

was correct in its timeline of Iran’s nuclear development and that the next year

will be critical. “The future can evolve in three ways,” he said. “Iran and the

international community could agree to a negotiated settlement; Israel and the

United States could acquiesce to a nuclear-armed Iran; or Israel or the United

States could attack. Nobody wants to go in the direction of a military strike,”

he added, “but unfortunately this is the most likely scenario. The more

interesting question is not whether it happens but how. The United States should

treat this option more seriously and begin gathering international support and

building the case for the use of force under international law.”

In June 2007, I met with a former director of the Mossad, Meir Amit, who handed

me a document stamped, “Top secret, for your eyes only.” Amit wanted to

demonstrate the complexity of the relations between the United States and

Israel, especially when it comes to Israeli military operations in the Middle

East that could significantly impact American interests in the region.

Almost 45 years ago, on May 25, 1967, in the midst of the international crisis

that precipitated the Six-Day War, Amit, then head of the Mossad, summoned John

Hadden, the C.I.A. chief in Tel Aviv, to an urgent meeting at his home. The

meeting took place against the background of the mounting tensions in the Middle

East, the concentration of a massive Egyptian force in the Sinai Peninsula, the

closing of the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping and the threats by President

Gamal Abdel Nasser to destroy the State of Israel.

In what he later described as “the most difficult meeting I have ever had with a

representative of a foreign intelligence service,” Amit laid out Israel’s

arguments for attacking Egypt. The conversation between them, which was

transcribed in the document Amit passed on to me, went as follows:

Amit: “We are approaching a turning point that is more important for you than it

is for us. After all, you people know everything. We are in a grave situation,

and I believe we have reached it, because we have not acted yet. . . .

Personally, I am sorry that we did not react immediately. It is possible that we

may have broken some rules if we had, but the outcome would have been to your

benefit. I was in favor of acting. We should have struck before the build-up.”

Hadden: “That would have brought Russia and the United States against you.”

Amit: “You are wrong. . . . We have now reached a new stage, after the expulsion

of the U.N. inspectors. You should know that it’s your problem, not ours.”

Hadden: “Help us by giving us a good reason to come in on your side. Get them to

fire at something, a ship, for example.”

Amit: “That is not the point.”

Hadden: “If you attack, the United States will land forces to help the attacked

state protect itself.”

Amit: “I can’t believe what I am hearing.”

Hadden: “Do not surprise us.”

Amit: “Surprise is one of the secrets of success.”

Hadden: “I don’t know what the significance of American aid is for you.”

Amit: “It isn’t aid for us, it is for yourselves.”

That ill-tempered meeting, and Hadden’s threats, encouraged the Israeli security

cabinet to ban the military from carrying out an immediate assault against the

Egyptian troops in the Sinai, although they were perceived as a grave threat to

the existence of Israel. Amit did not accept Hadden’s response as final,

however, and flew to the United States to meet with Defense Secretary Robert

McNamara. Upon his return, he reported to the Israeli cabinet that when he told

McNamara that Israel could not reconcile itself to Egypt’s military actions, the

secretary replied, “I read you very clearly.” When Amit then asked McNamara if

he should remain in Washington for another week, to see how matters developed,

McNamara responded, “Young man, go home, that is where you are needed now.”

From this exchange, Amit concluded that the United States was giving Israel “a

flickering green light” to attack Egypt. He told the cabinet that if the

Americans were given one more week to exhaust their diplomatic efforts, “they

will hesitate to act against us.” The next day, the cabinet decided to begin the

Six-Day War, which changed the course of Middle Eastern history.

Amit handed me the minutes of that conversation from the same armchair that he

sat in during his meeting with Hadden. It is striking how that dialogue

anticipated the one now under way between Israel and the United States.

Substitute “Tehran” for “Cairo” and “Strait of Hormuz” for “Straits of Tiran,”

and it could have taken place this past week. Since 1967, the unspoken

understanding that America should agree, at least tacitly, to Israeli military

actions has been at the center of relations between the two countries.

During my lengthy conversation with Barak, I pulled out the transcript of the

Amit-Hadden meeting. Amit was his commander when Barak was a young officer, in a

unit that carried out commando raids deep inside enemy territory. Barak, a

history buff, smiled at the comparison, and then he completely rejected it.

“Relations with the United States are far closer today,” he said. “There are no

threats, no recriminations, only cooperation and mutual respect for each other’s

sovereignty.”

In our conversation on Jan. 18, Ya’alon, the deputy prime minister, was sharp in

his criticism of the international community’s stance on Iran. “These are

critical hours on the question of which way the international community will

take the policy,” he said. “The West must stand united and resolute, and what is

happening so far is not enough. The Iranian regime must be placed under pressure

and isolated. Sanctions that bite must be imposed against it, something that has

not happened as yet, and a credible military option should be on the table as a

last resort. In order to avoid it, the sanctions must be stepped up.” It is, of

course, important for Ya’alon to argue that this is not just an Israeli-Iranian

dispute, but a threat to America’s well-being. “The Iranian regime will be

several times more dangerous if it has a nuclear device in its hands,” he went

on. “One that it could bring into the United States. It is not for nothing that

it is establishing bases for itself in Latin America and creating links with

drug dealers on the U.S.-Mexican border. This is happening in order to smuggle

ordnance into the United States for the carrying out of terror attacks. Imagine

this regime getting nuclear weapons to the U.S.-Mexico border and managing to

smuggle it into Texas, for example. This is not a far-fetched scenario.”

Ehud Barak dislikes this kind of criticism of the United States, and in a rather

testy tone in a phone conversation with me on Jan. 18 said: “Our discourse with

the United States is based on listening and mutual respect, together with an

understanding that it is our primary ally. The U.S. is what helps us to preserve

the military advantage of Israel, more than ever before. This administration

contributes to the security of Israel in an extraordinary way and does a lot to

prevent a nuclear Iran. We’re not in confrontation with America. We’re not in

agreement on every detail, we can have differences — and not unimportant ones —

but we should not talk as if we are speaking about a hostile entity.”

Over the last four years, since Barak was appointed minister of defense, the

Israeli military has prepared in unprecedented ways for a strike against Iran.

It has also grappled with questions of how it will manage the repercussions of

such an attack. Much of the effort is dedicated to strengthening the country’s

civil defenses — bomb shelters, air-raid sirens and the like — areas in which

serious defects were discovered during the war against Hezbollah in Lebanon in

the summer of 2006. Civilian disaster exercises are being held intermittently,

and gas masks have been distributed to the population.

On the operational level, any attack would be extremely complex. Iran learned

the lessons of Iraq, and has dispersed its nuclear installations throughout its

vast territory. There is no way of knowing for certain if the Iranians have

managed to conceal any key facilities from Israeli intelligence. Israel has

limited air power and no aircraft carriers. If it attacked Iran, because of the

1,000 or so miles between its bases and its potential targets, Israeli planes

would have to refuel in the air at least once (and more than once if faced with

aerial engagements). The bombardment would require pinpoint precision in order

to spend the shortest amount of time over the targets, which are heavily

defended by antiaircraft-missile batteries.

In the end, a successful attack would not eliminate the knowledge possessed by

the project’s scientists, and it is possible that Iran, with its highly

developed technological infrastructure, would be able to rebuild the damaged or

wrecked sites. What is more, unlike Syria, which did not respond after the

destruction of its reactor in 2007, Iran has openly declared that it would

strike back ferociously if attacked. Iran has hundreds of Shahab missiles armed

with warheads that can reach Israel, and it could harness Hezbollah to strike at

Israeli communities with its 50,000 rockets, some of which can hit Tel Aviv.

(Hamas in Gaza, which is also supported by Iran, might also fire a considerable

number of rockets on Israeli cities.) According to Israeli intelligence, Iran

and Hezbollah have also planted roughly 40 terrorist sleeper cells across the

globe, ready to hit Israeli and Jewish targets if Iran deems it necessary to

retaliate. And if Israel responded to a Hezbollah bombardment against Lebanese

targets, Syria may feel compelled to begin operations against Israel, leading to

a full-scale war. On top of all this, Tehran has already threatened to close off

the Persian Gulf to shipping, which would generate a devastating ripple through

the world economy as a consequence of the rise in the price of oil.

The proponents of an attack argue that the problems delineated above, including

missiles from Iran and Lebanon and terror attacks abroad, are ones Israel will

have to deal with regardless of whether it attacks Iran now — and if Iran goes

nuclear, dealing with these problems will become far more difficult.

The Israeli Air Force is where most of the preparations are taking place. It

maintains planes with the long-range capacity required to deliver ordnance to

targets in Iran, as well as unmanned aircraft capable of carrying bombs to those

targets and remaining airborne for up to 48 hours. Israel believes that these

platforms have the capacity to cause enough damage to set the Iranian nuclear

project back by three to five years.

In January 2010, the Mossad sent a hit team to Dubai to liquidate the

high-ranking Hamas official Mahmoud al-Mabhouh, who was coordinating the

smuggling of rockets from Iran to Gaza. The assassination was carried out

successfully, but almost the entire operation and all its team members were

recorded on closed-circuit surveillance TV cameras. The operation caused a

diplomatic uproar and was a major embarrassment for the Mossad. In the

aftermath, Netanyahu decided not to extend Dagan’s already exceptionally long

term, informing him that he would be replaced in January 2011. That decision was

not well received by Dagan, and three days before he was due to leave his post,

I and several other Israeli journalists were surprised to receive invitations to

a meeting with him at Mossad headquarters.

We were told to congregate in the parking lot of a movie-theater complex north

of Tel Aviv, where we were warned by Mossad security personnel, “Do not bring

computers, recording devices, cellphones. You will be carefully searched, and we

want to avoid unpleasantness. Leave everything in your cars and enter our

vehicles carrying only paper and pens.” We were then loaded into cars with

opaque windows and escorted by black Jeeps to a site that we knew was not marked

on any map. The cars went through a series of security checks, requiring our

escorts to explain who we were and show paperwork at each roadblock.

This was the first time in the history of the Mossad that a group of journalists

was invited to meet the director of the organization at one of the country’s

most secret sites. After the search was performed and we were seated, the

outgoing chief entered the room. Dagan, who was wounded twice in combat, once

seriously, during the Six-Day War, started by saying: “There are advantages to

being wounded in the back. You have a doctor’s certificate that you have a

backbone.” He then went into a discourse about Iran and sharply criticized the

heads of government for even contemplating “the foolish idea” of attacking it.

“The use of state violence has intolerable costs,” he said. “The working

assumption that it is possible to totally halt the Iranian nuclear project by

means of a military attack is incorrect. There is no such military capability.

It is possible to cause a delay, but even that would only be for a limited

period of time.”

He warned that attacking Iran would start an unwanted war with Hezbollah and

Hamas: “I am not convinced that Syria will not be drawn into the war. While the

Syrians won’t charge at us in tanks, we will see a massive offensive of missiles

against our home front. Civilians will be on the front lines. What is Israel’s

defensive capability against such an offensive? I know of no solution that we

have for this problem.”

Asked if he had said these things to Israel’s decision-makers, Dagan replied: “I

have expressed my opinion to them with the same emphasis as I have here now.

Sometimes I raised my voice, because I lose my temper easily and am overcome

with zeal when I speak.”

In later conversations Dagan criticized Netanyahu and Barak, and in a lecture at

Tel Aviv University he observed, “The fact that someone has been elected doesn’t

mean that he is smart.”

In the audience at that lecture was Rafi Eitan, 85, one of the Mossad’s most

seasoned and well-known operatives. Eitan agreed with Dagan that Israel lacked

the capabilities to attack Iran. When I spoke with him in October, Eitan said:

“As early as 2006 (when Eitan was a senior cabinet minister), I told the cabinet

that Israel couldn’t afford to attack Iran. First of all, because the home front

is not ready. I told anyone who wanted and still wants to attack, they should

just think about two missiles a day, no more than that, falling on Tel Aviv. And

what will you do then? Beyond that, our attack won’t cause them significant

damage. I was told during one of the discussions that it would delay them for

three years, and I replied, ‘Not even three months.’ After all, they have

scattered their facilities all over the country and under the ground. ‘What harm

can you do to them?’ I asked. ‘You’ll manage to hit the entrances, and they’ll

have them rebuilt in three months.’ ”

Asked if it was possible to stop a determined Iran from becoming a nuclear

power, Eitan replied: “No. In the end they’ll get their bomb. The way to fight

it is by changing the regime there. This is where we have really failed. We

should encourage the opposition groups who turn to us over and over to ask for

our help, and instead, we send them away empty-handed.”

Israeli law stipulates that only the 14 members of the security cabinet have the

authority to make decisions on whether to go to war. The cabinet has not yet

been asked to vote, but the ministers might, under pressure from Netanyahu and

Barak, answer these crucial questions about Iran in the affirmative: that these

coming months are indeed the last opportunity to attack before Iran enters the

“immunity zone”; that the broad international agreement on Iran’s intentions and

the failure of sanctions to stop the project have created sufficient legitimacy

for an attack; and that Israel does indeed possess the capabilities to cause

significant damage to the Iranian project.

In recent weeks, Israelis have obsessively questioned whether Netanyahu and

Barak are really planning a strike or if they are just putting up a front to

pressure Europe and the U.S. to impose tougher sanctions. I believe that both of

these things are true, but as a senior intelligence officer who often

participates in meetings with Israel’s top leadership told me, the only

individuals who really know their intentions are, of course, Netanyahu and

Barak, and recent statements that no decision is imminent must surely be taken

into account.

After speaking with many senior Israeli leaders and chiefs of the military and

the intelligence, I have come to believe that Israel will indeed strike Iran in

2012. Perhaps in the small and ever-diminishing window that is left, the United

States will choose to intervene after all, but here, from the Israeli

perspective, there is not much hope for that. Instead there is that peculiar

Israeli mixture of fear — rooted in the sense that Israel is dependent on the

tacit support of other nations to survive — and tenacity, the fierce conviction,

right or wrong, that only the Israelis can ultimately defend themselves.

Ronen Bergman,

an analyst for the Israeli newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth, is the author of ‘‘The

Secret War With Iran’’ and a contributing writer for the magazine.

Editor: Joel

Lovell

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: January 25, 2012

An earlier version misstated part of the name of a treaty that limits the

proliferation

of nuclear

weapons. It is the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, not Proliferation.

Will Israel Attack Iran?, NYT, 25.1.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/29/magazine/will-israel-attack-iran.html

Israel

Senses Bluffing in Iran’s Threats of Retaliation

January 26,

2012

The New York Times

By ETHAN BRONNER

JERUSALEM —

Israeli intelligence estimates, backed by academic studies, have cast doubt on

the widespread assumption that a military strike on Iranian nuclear facilities

would set off a catastrophic set of events like a regional conflagration,

widespread acts of terrorism and sky-high oil prices.

The estimates, which have been largely adopted by the country’s most senior

officials, conclude that the threat of Iranian retaliation is partly bluff. They

are playing an important role in Israel’s calculation of whether ultimately to

strike Iran, or to try to persuade the United States to do so, even as Tehran

faces tough new economic sanctions from the West.

“A war is no picnic,” Defense Minister Ehud Barak told Israel Radio in November.

But if Israel feels itself forced into action, the retaliation would be

bearable, he said. “There will not be 100,000 dead or 10,000 dead or 1,000 dead.

The state of Israel will not be destroyed.”

The Iranian government, which says its nuclear program is for civilian purposes,

has threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz — through which 90 percent of gulf

oil passes — and if attacked, to retaliate with all its military might.

But Israeli assessments reject the threats as overblown. Mr. Barak and Prime

Minister Benjamin Netanyahu have embraced those analyses as they focus on how to

stop what they view as Iran’s determination to obtain nuclear weapons.

No issue in Israel is more fraught than the debate over the wisdom and

feasibility of a strike on Iran. Some argue that even a successful military

strike would do no more than delay any Iranian nuclear weapons program, and

perhaps increase Iran’s determination to acquire the capability. Security

officials are increasingly kept from journalists or barred from discussing Iran.

Much of the public talk is as much message delivery as actual policy.

With the region in turmoil and the Europeans having agreed to harsh sanctions

against Iran, strategic assessments can quickly lose their currency. “They’re

like cartons of milk — check the sell-by date,” one senior official said.

But conversations with eight current and recent top Israeli security officials

suggested several things: since Israel has been demanding the new sanctions,

including an oil embargo and seizure of Iran’s Central Bank assets, it will give

the sanctions some months to work; the sanctions are viewed here as probably

insufficient; a military attack remains a very real option; and postattack

situations are considered less perilous than one in which Iran has nuclear

weapons.