|

History > 2014 > USA > African-Americans (I)

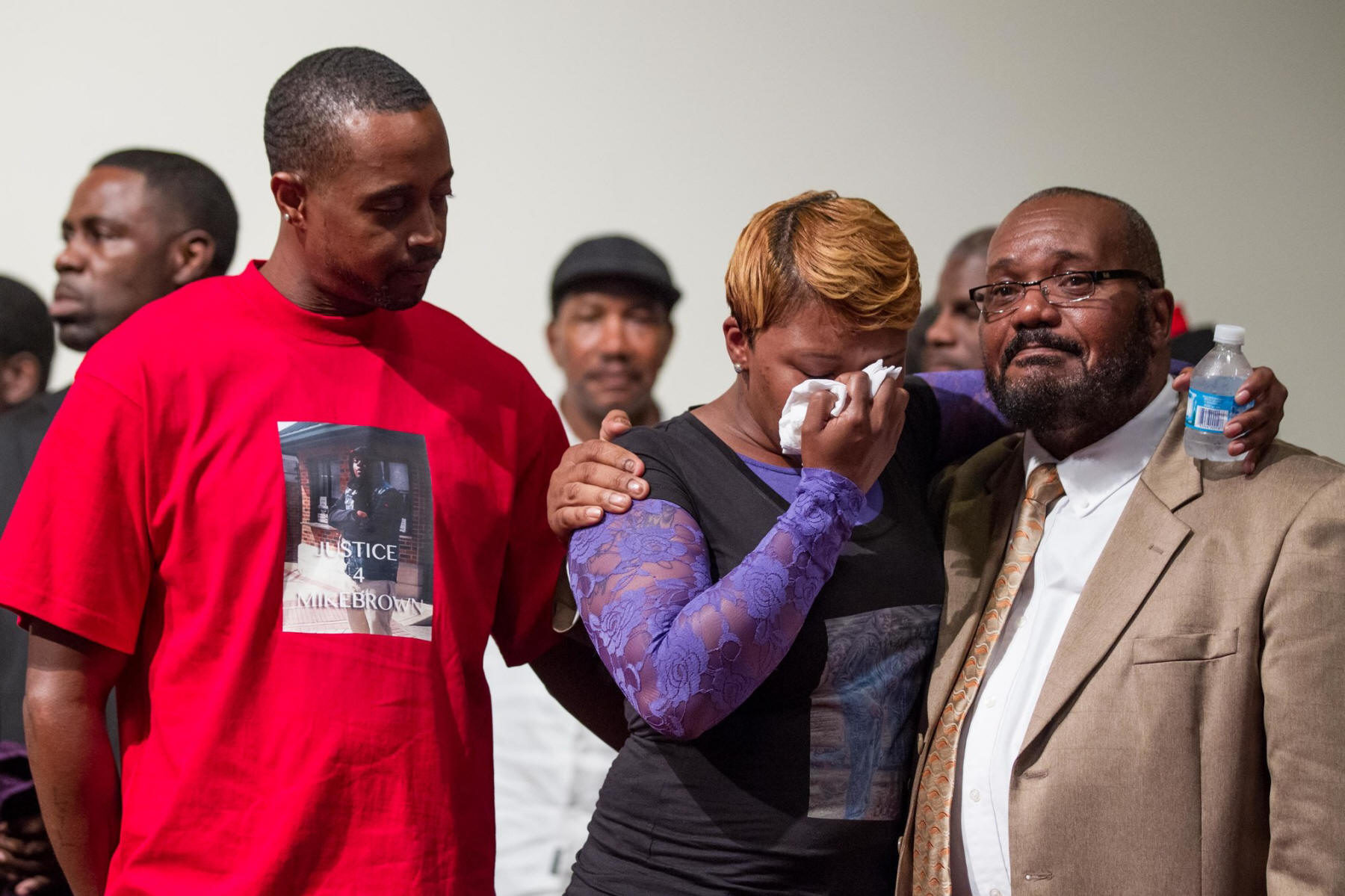

Lesley McSpadden and her husband, Louis Head,

mourning for her son, Michael Brown,

who died in the street on Saturday.

Photograph:

Huy Mach/St. Louis Post-Dispatch, via Associated Press

Grief and Protests Follow Shooting of a Teenager

NYT

10.8.2014

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/11/us/police-say-mike-brown-was-killed-after-struggle-for-gun.html

Mr. Brown’s stepfather, Louis Head, left,

his mother, Lesley McSpadden, and an uncle, Charles Ewing

were at the church gathering.

The Rev. Al Sharpton also attended.

Photpgraph: Whitney Curtis for The New York Times

Amid Protests in Missouri, Officer’s Name Is Still

Withheld

NYT

13.8.2014

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/14/us/missouri-teenager-and-officer-scuffled-before-shooting-chief-says.html

Timeline for a Body:

4 Hours in the Middle

of a Ferguson Street

AUG. 23, 2014

By JULIE BOSMAN

and JOSEPH GOLDSTEIN

FERGUSON, Mo. — Just after noon on Saturday, Aug. 9, Michael

Brown was shot dead by a police officer on Canfield Drive.

For about four hours, in the unrelenting summer sun, his body remained where he

fell.

Neighbors were horrified by the gruesome scene: Mr. Brown, 18, face down in the

middle of the street, blood streaming from his head. They ushered their children

into rooms that faced away from Canfield Drive. They called friends and local

news stations to tell them what had happened. They posted on Twitter and

Facebook and recorded shaky cellphone videos that would soon make their way to

the national news.

Mr. Brown probably could not have been revived, and the time that his body lay

in the street may ultimately have no bearing on the investigations into whether

the shooting was justified. But local officials say that the image of Mr.

Brown’s corpse in the open set the scene for what would become a combustible

worldwide story of police tactics and race in America, and left some of the

officials asking why.

“The delay helped fuel the outrage,” said Patricia Bynes, a committeewoman in

Ferguson. “It was very disrespectful to the community and the people who live

there. It also sent the message from law enforcement that ‘we can do this to you

any day, any time, in broad daylight, and there’s nothing you can do about it.’

”

Two weeks after Mr. Brown’s death, interviews with law enforcement officials and

a review of police logs make clear that a combination of factors, some under

police control and some not, contributed to the time lapse in removing his body.

The St. Louis County Police Department, which almost immediately took over the

investigation, had officers on the scene quickly, but its homicide detectives

were not called until about 40 minutes after the shooting, according to county

police logs, and they arrived around 1:30 p.m. It was another hour before an

investigator from the medical examiner’s office arrived.

And officials were contending with what they described as “sheer chaos” on

Canfield Drive, where bystanders, including at least one of Mr. Brown’s

relatives, frequently stepped inside the yellow tape, hindering investigators.

Gunshots were heard at the scene, further disrupting the officers’ work.

“Usually they go straight to their jobs,” Officer Brian Schellman, a county

police spokesman, said of the detectives who process crime scenes for evidence.

“They couldn’t do that right away because there weren’t enough police there to

quiet the situation.”

For part of the time, Mr. Brown’s body lay in the open, allowing people to

record it on their cellphones. A white sheet was draped over Mr. Brown’s body,

but his feet remained exposed and blood could still be seen. The police later

shielded the body with a low, six-panel orange partition typically used for car

crashes.

Experts in policing said there was no standard for how long a body should remain

at a scene, but they expressed surprise at how Mr. Brown’s body had been allowed

to remain in public view.

Asked to describe procedures in New York, Gerald Nelson, a chief who commands

the patrol forces in much of Brooklyn, said that as soon as emergency medical

workers have concluded that a victim is dead, “that body is immediately

covered.”

“We make sure we give that body the dignity it deserves,” Chief Nelson said.

St. Louis County police officials acknowledged that they were uncomfortable with

the time it took to shield Mr. Brown’s body and have it removed, and that they

were mindful of the shocked reaction from residents. But they also defended

their work, saying that the time that elapsed in getting detectives to the scene

was not out of the ordinary, and that conditions made it unusually difficult to

do all that they needed.

“Michael Brown had one more voice after that shooting, and his voice was the

detectives’ being able to do a comprehensive job,” said Jon Belmar, chief of the

St. Louis County Police Department.

Mr. Brown and a friend, Dorian Johnson, were walking down Canfield Drive at

12:01 p.m. when Officer Darren Wilson of the Ferguson Police Department

encountered them. Moments later, Mr. Brown was dead, shot at least six times by

Officer Wilson.

Other Ferguson officers were summoned, including Tom Jackson, the chief of

police in this town of 21,000 people. While Chief Jackson was en route, he

called Chief Belmar of the county police.

It was typical, given the limited resources of the Ferguson Police Department,

to transfer a homicide investigation to the St. Louis County police, a much

larger force with more specialized officers.

According to police logs, the county police received a report of the shooting at

12:07, and their officers began arriving around 12:15. Videos taken by

bystanders show that in the first minutes after Mr. Brown’s death, officers

quickly secured the area with yellow tape. In one video, several police cars

were on the scene, and officers were standing close to their cars, a distance

away from Mr. Brown’s body.

Around 12:10, a paramedic who happened to be nearby on another call approached

Mr. Brown’s body, checked for a pulse, and observed the blood and “injuries

incompatible with life,” said his supervisor, Chris Cebollero, the chief of

emergency medical services at Christian Hospital. He estimated that it had been

around 12:15 when a sheet was retrieved from an ambulance and used to cover Mr.

Brown.

Relatives of Mr. Brown said they were at the scene quickly after hearing of the

shooting from a family friend, who had been driving in the area and recognized

the teenager’s body. They said they begged for information but received nothing.

Louis Head, Mr. Brown’s stepfather, said the police had prevented him from

approaching the body. “Nobody came to nobody and said, ‘Hey, we’re sorry,’ ” he

said. “Nobody said nothing.”

At one point, Brendan Ewings, Mr. Brown’s uncle, is seen in a video walking up

to the police tape and staring at Mr. Brown’s body. Mr. Ewings, 39, ducked under

the tape and walked slowly toward the body, prompting one officer to yell,

sprint toward him and lead him away.

“I went up to it,” Mr. Ewings recalled in an interview on Thursday. “I seen the

body, and I recognized the body. That’s when the dude grabbed me.”

Mr. Ewings said he pleaded for information about his nephew. “I said, ‘A cop did

this?’ ”

It was not until 12:43 p.m. that detectives from the county police force were

notified of the shooting, according to county police records. Officer Schellman,

the county police spokesman, said Friday that Chief Belmar did not recall

exactly when he had received the call from his counterpart in Ferguson. But,

Officer Schellman said, Chief Belmar reported that as soon as he hung up, he

immediately called the chief of detectives.

The detectives arrived around 1:30, and an hour later, a forensic investigator,

who gathers information for the pathologist who will conduct the autopsy,

arrived from the medical examiner’s office, said Suzanne McCune, an

administrator in that office.

Mr. Brown’s body had been in the street for more than two hours.

Francis G. Slay, the mayor of St. Louis, whose city did not have a role in the

shooting or the investigation, said in an interview that his city had a “very

specific policy” for handling such situations.

He continued: “We’ll cover the body appropriately with screening or tents, so

it’s not exposed to the public. We do the investigation as quickly as we can.”

Dr. Michael M. Baden, the former New York City chief medical examiner who was

hired by the Brown family’s lawyers to do an autopsy, said it was “a mistake” to

let the body remain in the street for so long.

“In my opinion, it’s not necessary to leave a body in a public place for that

many hours, particularly given the temperature and the fact that people are

around,” he said. “There is no forensic reason for doing that.”

The St. Louis County police declined to give details about what evidence

investigators had been gathering while Mr. Brown’s body was in the street.

Typically, said John Paolucci, a former detective sergeant at the New York

Police Department, crime scene investigators would work methodically.

If there had been a struggle between an officer and a shooting victim, the

officer’s shirt would be taken as evidence. The police cruiser would be towed to

a garage and examined there.

Detectives would want to find any shell casings, said Mr. Paolucci, who retired

in 2012 as the commanding officer of the unit that served as liaison between the

detective bureau and the medical examiner’s office.

Usually, the police conduct very little examination of the body at the scene,

other than photographing it, he said.

“We might use vehicles to block the body from public view depending on where

cameras are and how offensive the scene is, if something like that is starting

to raise tensions,” Mr. Paolucci said.

Chief Belmar said that while he was unable to explain why officers had waited to

cover Mr. Brown’s body, he said he thought they would have done so sooner if

they could have.

As the crowd on Canfield Drive grew, the police, including officers from St.

Louis County and Ferguson, tried to restore order. At one point, they called in

a Code 1000, an urgent summons to nearby police officers to help bring order to

a scene, police officials said.

Even homicide detectives, who do not ordinarily handle such tasks, “were trying

to get the scene under control,” said Officer Rick Eckhard, another spokesman

for the St. Louis County police.

Sometime around 4 p.m., Mr. Brown’s body, covered in a blue tarp and loaded into

a dark vehicle, was transported to the morgue in Berkeley, Mo., about six miles

from Canfield Drive, a roughly 15-minute drive.

Mr. Brown’s body was checked into the morgue at 4:37 p.m., more than four and a

half hours after he was shot.

Alan Blinder and John Eligon contributed reporting.

A version of this article appears in print on August 24, 2014, on page A1 of the

New York edition with the headline: Timeline for a Body: 4 Hours in the Middle

of a Ferguson Street.

Timeline for a Body: 4 Hours in the Middle of

a Ferguson Street,

NYT, 23.8.2014,

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/24/us/

michael-brown-a-bodys-timeline-4-hours-on-a-ferguson-street.html

Despite Similar Shooting,

Los Angeles’s ‘Bank of Trust’

Tempers Reaction

AUG. 22, 2014

The New York Times

By JENNIFER MEDINA

LOS ANGELES — When Los Angeles police officers shot and killed

Ezell Ford, an unarmed 25-year-old black man last week, it took less than 24

hours for Lita Herron to get a phone call from a ranking officer at a nearby

station.

“They wanted to check in and gauge our rage,” said Ms. Herron, a grandmother and

organizer who has worked to prevent gang violence on the streets of South Los

Angeles for years. “They wanted to ask us to quell rumors and hear what we need.

We’ve all been through this before — even when we know things are wrong, we

aren’t looking for things to explode.”

In Ferguson, Mo., however, angry protests stretched on for nearly two weeks

after the police killing of Michael Brown in circumstances that were strikingly

similar: an unarmed young black man shot by the police, who some witnesses say

was not putting up a struggle.

The killings occurred two days apart. The protests in Missouri were driven

initially, in large part, by the police’s refusal to release the name of the

officer involved or details of the Aug. 9 shooting. Here, the police are still

holding back the autopsy report and the names of the officers involved, citing

security concerns.

Yet the reaction in Los Angeles, where clashes between the police and residents

have a long history, has so far been much calmer.

While there have been several protests since the Aug. 11 shooting of Mr. Ford,

who was mentally ill, including an impromptu march that blocked traffic on city

streets, the police have maintained a relatively low profile, relying primarily

on a handful of bicycle-riding officers in polo shirts rather than the

rifle-carrying officers in riot gear pictured in Ferguson. This week, Chief

Charlie Beck and other top-ranking officials showed up for a community meeting

at a local church, telling the angry crowd of several hundred that there were

still more questions than answers about the shooting.

In the more than two decades since riots erupted after white police officers

were acquitted in the beating of Rodney G. King, a black construction worker,

relations between law enforcement and their communities here have changed

drastically. In many South Los Angeles police precincts, officers routinely

check in with organizers like Ms. Herron. Local church leaders have officers’

phone numbers committed to memory. When protests are planned, seasoned

organizers let the police know — even when the police are the target of their

outrage.

“We have an infrastructure here where there are outlets for people to vent

frustration and move into action,” said Marqueece Harris-Dawson, the president

of Community Coalition, which runs several programs for residents in South Los

Angeles. “This has taken more than 20 years to build and sustain — there’s no

question it would not have been this way a generation or two ago.”

Still, on the streets of South Los Angeles, a predominantly black and Latino

neighborhood, a sense of distrust of the police remains. Mr. Harris-Dawson, who

is black, often points out that he has had a gun pointed at him by an L.A.P.D.

officer four times and has never carried a weapon. Black and Latino teenage boys

rattle off instances where they were pulled over and questioned for what they

say was no reason. Still, many local leaders are willing to give the department

some leeway to continue the investigation into the Ford shooting before coming

to a clear conclusion.

Continue reading the main story Continue reading the main story

“The chief also does not make it the job of the department to exonerate the

officer,” Mr. Harris-Dawson said. “They do take a minute to have some remorse

for the fact that someone is dead.”

When Earl Ofari Hutchinson, a longtime civil rights leader here and a frequent

critic of the department, demanded a meeting with top police officials last

week, they quickly arranged to discuss the case. They listened to Mr.

Hutchinson’s demands for a “fast track” investigation and a quick release of the

officers’ names and the autopsy results. Earl Paysinger, an assistant police

chief, declined to predict when such information would be available, saying

detectives were still canvassing the area looking for witnesses.

Chief Paysinger said in an interview on Friday that the department was “well

aware we can’t let it go on indefinitely.”

“We’ve seen this film before — this is ‘Groundhog Day’ for us,” Chief Paysinger

said. “What the people are demanding is not unreasonable. We know that whatever

we say first will become gospel, and we’d rather deal with some discontent now

than putting out information we have to correct later.”

Mr. Paysinger, who has been with the department for nearly 40 years and oversees

its day-to-day operations, said that the department had for years now tried to

rely on what it called the “bank of trust” among community members. Just more

than a year ago, the department was under a consent decree imposed by the

Justice Department, after dozens of officers were accused of tampering with

evidence and physically abusing and framing suspects.

“We’ve learned that community outreach can’t wait for the day when you’re in

trouble and need help,” Chief Paysinger said. Now, he said, the network of

community support is so wide, it is a matter of course for officers to call

local leaders routinely. And the efforts have expanded along with the importance

of social media: Each police station now assigns personnel to monitor websites,

Facebook and Twitter almost round-the-clock, watching for everything from signs

of gang activity to how people are reacting to political events.

In some sense, Mr. Ford’s death is remarkable for the publicity it has received

here — several longtime activists said it would be easy to imagine the shooting

getting little attention were it not for the outrage in Missouri.

Officers here have shot and killed 12 people so far this year, compared with 14

such deaths all of last year. In several protests after the Ford shooting, one

organization held up a large banner listing the names of more than 300 people

who have died during conflicts with law enforcement here in the last seven

years.

“This happened just as it became clear that Ferguson was a billboard of what we

did not want to do,” said Curren Price, a city councilman who represents South

Los Angeles and organized the community meeting this week, which was attended by

the police chief, as well as the head of the police oversight board. “We all

knew this is another critical juncture for us.”

“There are a lot of deep wounds — L.A.P.D. was a pretty notorious organization

not that long ago,” Mr. Price said. “Unfortunately, anytime something like this

happens, it brings all that back to the surface. There’s still a long way to go

before we can say things are good.”

A version of this article appears in print on August 23, 2014, on page A14 of

the New York edition with the headline: Despite Similar Shooting, Los Angeles’s

‘Bank of Trust’ Tempers Reaction.

Despite Similar Shooting,

Los Angeles’s ‘Bank of Trust’ Tempers Reaction,

NYT, 22.8.2014,

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/23/us/despite-similar-shootings-steps

by-los-angeles-police-temper-reaction.html

Constructing a Conversation on Race

AUG. 20, 2014

The New York Times

The Opinion Pages | Op-Ed Columnist

Charles M. Blow

The killing of an unarmed teenager, Michael Brown, by a police

officer, Darren Wilson, and the protests that have followed have brought about

calls for the much-ballyhooed — or bemoaned, depending on your perspective —

conversation about race.

I wish these calls were not so episodic and tied to tragedies. I also wish this

call for a conversation wasn’t tied to protests. Protests have life cycles. They

explode into existence, but they all eventually die. They build like pressure in

the volcano until they erupt. Then there is quiet until the next eruption. The

cycle is untenable and nearly devoid of aim and the possibility of resolution.

What we must discuss is best discussed during the dormancy.

The discussion just needs some guidance.

Let’s start with understanding what a racial conversation shouldn’t look like.

It shouldn’t be an insulated, circular, intra-racial dialogue only among people

who feel aggrieved.

A true racial dialogue is not intra-racial but interracial. It is not

one-directional — from minorities to majorities — but multidirectional. Data

must be presented. Experiences must be explored. Histories and systems must be

laid bare. Biases, fears, stereotype and mistrust must be examined. Personal —

as well as societal and cultural — responsibility must be taken.

And privileges and oppressions must be acknowledged. We must acknowledge how

each of us is, in myriad ways, materially and spiritually affected by a society

in which bias has been widely documented to exist and in which individuals also

acknowledge that it exists.

Take the results of a CBS News poll released in July. While three-fourths of

respondents believe, rightly, that progress has been made to get rid of racial

discrimination, most Americans acknowledge that discrimination against blacks

still exists today.

It may come as little surprise that 88 percent of blacks gauged that level of

discrimination as “a lot” or “some” as opposed to “only a little” or “none at

all,” but 65 percent of whites agree the level of discrimination against blacks

rises to “a lot” or “some.”

Yet when asked whether whites or blacks have a better chance of getting ahead

today, 63 percent of whites and 43 percent of blacks said that the chances were

equal. (By comparison, 28 percent of whites and 46 percent of blacks said whites

had a better chance of getting ahead, and only 5 percent of whites and 4 percent

of black said blacks had a better chance.)

We have to stop here and really process what we are saying: that even though we

acknowledge the existence of discrimination, we still expect those who are the

focus of it to succeed, or “get ahead,” at the same rate as those who aren’t. In

effect, we are expecting black people to simply shoulder the extra burden that

society puts on their shoulders — oppression — while others are free to rise, or

even fall, without such a burden — privilege.

Understanding this fundamental inequality, one that trails each of us from

cradle to grave, is one of the first steps to genuine, honest dialogue, because

in that context we can better understand the choice that people make and the

degree to which personal responsibility should be taken or the degree to which

it is causative or curative.

And while acknowledging the inequality, and hopefully working to remedy it, we

have to find ways to encourage and fortify its targets. I often tell people that

while I know well that things aren’t fair or equal, we still have to decide how

we are going to deal with that reality, today. The clock on life is ticking. If

you wait for life to be fair you may be waiting until life is over. I urge

people to fight on two fronts: Work to dismantle as much systematic bias as you

can, as much for posterity as for the present, and make the best choice you can

under the circumstances to counteract the effects of these injustices on your

life right now.

Next, understand that race is a weaponized social construct used to divide and

deny.

According to a policy statement on race by the American Anthropological

Association, “human populations are not unambiguous, clearly demarcated,

biologically distinct groups” and “there is greater variation within ‘racial’

groups than between them.”

The statement continues:

“How people have been accepted and treated within the context of a given society

or culture has a direct impact on how they perform in that society. The ‘racial’

worldview was invented to assign some groups to perpetual low status, while

others were permitted access to privilege, power, and wealth. The tragedy in the

United States has been that the policies and practices stemming from this

worldview succeeded all too well in constructing unequal populations among

Europeans, Native Americans, and peoples of African descent.”

It ends:

“We conclude that present-day inequalities between so-called ‘racial’ groups are

not consequences of their biological inheritance but products of historical and

contemporary social, economic, educational, and political circumstances.”

And yet, we have tuned our minds to register this difference above all others,

in the blink of an eye. As National Geographic reported in October, “A study of

brain activity at the University of Colorado at Boulder showed that subjects

register race in about one-tenth of a second, even before they discern gender.”

This means that racial registration — and responses to any subconscious bias we

may have attached to race — are most likely happening ahead of any deliberative

efforts on our part to be egalitarian.

Another step is that we must understand that race is not an isolated construct

or consideration. Race and class, education and economics, crime and justice,

and family and culture all overlap and intersect. We can’t treat the organ as if

it is separate from the organism.

Lastly, some immunity must be granted. Assuming that the conversational

engagement is honest and earnest, we must be able to hear and say things that

some might find offensive as we stumble toward interpersonal empathy and

understanding.

We can talk this through. We can have this conversation. We must. Hopefully this

provides a little nudge and a few parameters.

Constructing a Conversation on Race, NYT,

20.8.2014,

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/21/opinion/

charles-blow-constructing-a-conversation-on-race.html

Anger, Hurt

and Moments of Hope

in Ferguson

AUG. 20, 2014

By JOHN ELIGON

The New York Times

FERGUSON, Mo. — The long, white bus emerged from a dark side

street earlier in the week. Through the tinted windows, people on the street

could see flashing lights and bodies moving to a beat. It was a party bus.

It crept slowly through an angry crowd of demonstrators and a cluster of armored

vehicles and police officers with large weapons threatening to arrest people if

they did not disperse. Some in the crowd started dancing.

Eventually, the bus made a U-turn and raced out of the police spotlight’s glare.

And the demonstrators returned their attention to the police, shouting, “Don’t

shoot me,” and gesturing obscenely.

Ferguson is a strange place these days. Ever since a white police officer,

Darren Wilson, fatally shot an unarmed black youth, Michael Brown, two Saturdays

ago, this St. Louis suburb has been deeply troubled, but also sometimes hard to

fathom. By night, it can seethe with anger and frustration; by day, hope and

even celebration can appear.

It is a place where the emotions of young black men run raw and real, where they

say their voices are finally being heard. They hope the fallout from the death

of Mr. Brown, 18, will change the way the police treat them.

Night after night, the more orderly passions of the day have given way to the

actions of a provocative few who have volleyed bottles at the police. Some stick

up their middle fingers and fire guns. There have been tear gas, smoke grenades

and the National Guard.

On Monday night, police officers in helmets and body armor clutched large

weapons. They stood close to armored vehicles parked in a tight cluster in the

middle of a dark street, shining spotlights on the taunting crowd around them.

Several men bounded toward the officers with their hands in the air. One of them

knelt. “Don’t shoot me!” they yelled.

“You must leave the area in a peaceful manner,” one officer barked over a

loudspeaker.

“You are unlawfully assembled,” said another.

People in the crowd only screamed back louder. Some stood tall and squared up to

the officers. Before long, a bang rang out. And then fire, smoke, pops, screams

and a mad dash. People running every which way, ducking.

By dawn it was all gone, and what seemed to be an ordinary new day broke in

Ferguson.

Two of the town’s main retail zones are along West Florissant Avenue and South

Florissant Road, parallel north-south streets. At the southern end of West

Florissant in Ferguson is the Northland Shopping Center, with a Target, a

Schnucks grocery store and smaller retailers. At night it becomes the command

post for the riot police and the National Guard troops. Heading north are some

strip malls and free-standing stores, including the convenience store that Mr.

Brown is said to have robbed minutes before he died, and businesses that were

damaged in the week of rioting.

Among these were a looted and burned QuikTrip convenience store, a short

distance from Canfield Road, and a cluster of low-rise apartment buildings,

occupied largely by low-income black families, including Mr. Brown’s

grandmother.

Continue reading the main story

South Florissant remains a mostly quiet, charming strip of low-slung brick

buildings with a diverse offering of mom-and-pop restaurants and bars. Nearby,

on residential streets with modest clapboard or brick homes, residents can be

found mowing their lawns and playing basketball.

Businesses toe the uncomfortable line between caution and acceptance — many have

boarded up their windows but spray-painted the plywood with big black letters

that say they remain open.

“I’m just confused — don’t know who to trust,” said Abe, a co-owner of Sam’s

Meat Market, who declined to give his last name, while surveying his half-empty

store that has been looted twice since Mr. Brown’s death. Since his store opened

in 2009, he said, he has made many friends in the community, including Mr. Brown

and his family. So while he hates the looting, he also wants to see justice for

the dead teenager.

“I’m not happy what they’re doing, kicking all the protesters out,” he said of

the police. “I want to see protests.”

People pace West Florissant Avenue, the center of the protests, shouting into

bullhorns and holding signs with messages like “Black Lives Matter” and “Don’t

Shoot.” A man wearing a white tank top bounded down the side of the road,

clutching cases of bottled water in each hand, giving bottles away, while

another man across the street carried and distributed water from three stacked

cases. Conversations with people, from police officers to ministers to

protesters, usually end with the send-off, “Be safe.”

A tall, athletic man with a crisp, white shirt circulated through the McDonald’s

on West Florissant one afternoon, offering to refill people’s drinks. He owns a

McDonald’s in an adjacent town, Jennings, and came here to volunteer. “This is a

safe haven; we love being here,” he said, declining to give his name. “I’m proud

to be a part of this.”

Michael Parnell, 29, of Ferguson, said that despite the violence, at least

people in the community were not directing it toward one another.

“It’s bringing everybody together,” said Mr. Parnell, who has been supportive of

the violent clashes with the police. “It’s getting everybody to know one

another. It’s getting everybody to love each other and to show we are united. We

can come together and not fight amongst each other, but for the right things for

the right person.”

There has been a noticeable generational divide since the demonstrations began,

with an apparently leaderless group of young people facing off with the police

late at night. But in recent days, some older leaders, including local ministers

and others representing various civil rights groups, have turned out to provide

guidance and to try to bridge the gap.

The Rev. Rodney T. Francis, the pastor of the Washington Tabernacle Missionary

Baptist Church and a member of the St. Louis Metropolitan Clergy Coalition,

spoke at a vigil last weekend and said he and others were seeking black

entertainers and athletes to help communicate with young African-Americans to

call for peace.

“We clearly have a group of young people who are just totally disaffected by any

appeals for calm that we are making,” Mr. Francis said. “Their disengagement is

very deep and they are very hurt, and that certainly doesn’t excuse their

actions.”

For some, Ferguson feels like a place they simply have to be.

Martez Davis is only 13, and wisp thin, but he came here by himself from

Jennings.

“I just think what they did to that young boy is wrong,” he said, marching with

a cardboard sign that said the protests would continue until the officer who

shot Mr. Brown was charged.

When James Williams, 23, saw Martez, he extended a hand and said, “You good,

little bro?”

For Mr. Williams, all the outrage swirling right now presents a chance to

release long-stifled emotions. About 13 years ago, St. Louis County police

officers shot and killed his mother after raiding her house for drugs and

shooting her on the stairs when, they said, she wielded a shiny object. The

object his mother, Annette Green, was holding was a foot-long bolt, the police

said.

A grand jury convened under Robert P. McCulloch, the same St. Louis County

prosecutor investigating the Brown shooting, declined to charge the officer who

shot Ms. Green. Mr. Williams, who was 10 at the time, said he did not remember

any major unrest or protest in the wake of his mother’s death. Certainly nothing

like what is going on now.

“I do understand where the people are coming from,” said Mr. Williams, who kept

a smile one morning as he rode a bicycle around the protest area on West

Florissant. Now, Mr. Williams said, Mr. Brown might get the justice that he

wanted for his mother.

But emotions can be upended quickly. Later in the day, after Mr. Williams

exchanged words with an officer who wanted him to move from where he was

standing, he bounded down West Florissant furiously, having to be restrained by

a fellow protester. He dared officers to shoot him.

Photo

Joshua Harris at Red’s on West Florissant in Ferguson. Businesses along the road

were damaged during the week of rioting. Credit Eric Thayer for The New York

Times

“I’ll go meet her,” Mr. Williams, referring to his mother, screamed at officers

lining the street. One of the officers appeared to be filming Mr. Williams with

his camera phone. The officer shot Mr. Williams a sarcastic smile and wave,

which riled him up even more.

“What!” Mr. Williams cried. “You recording? You going to go home and laugh about

it?”

This level of disdain for the police in the St. Louis region is common among the

black men of Mr. Williams’s generation, who rattle off the times that they say

they have been roughed up and disrespected by the police with little

provocation.

This collective anger weighs heavily in Ferguson. It pops up in conversations

during protest marches, and in moments of reflection next to the memorial in the

middle of the narrow residential street where Mr. Brown fell. Brandon and Brian

Curtis, 23, stood by their black Pontiac next to that memorial on Monday, saying

they fully empathized with the feelings of those who have been skirmishing

against the police here. From their car stereo blared a rap song by Lil Boosie

that uses derogatory language to insult the police.

Continue reading the main story

If the police fire tear gas, Brian Curtis said, protesters should pick up the

canisters and throw them back. The north St. Louis County residents recalled one

time in the winter about two years ago when they were returning home from a

convenience store with some friends, and police officers stopped them and

slammed them into the snow. One of their friends had a broken arm, they said,

but the officer still made him put it behind his back.

“It’s to the point like, years and years and years, man, it’s like war with

these people,” said Brandon Curtis, who works in retail.

But they said the looting and pre-emptive violence needed to stop. That was like

going to your last resort first, they said.

This was such an important moment, Brian Curtis emphasized, that they had to get

it right.

History is being made in Ferguson, he said. Then, referring to the police, he

added, “St. Louis need to change their ways, though, for real.”

On West Florissant, after the sun had set, Qua Calhoun also felt the magnitude

of the moment. But his opinion of how to seize it was much different.

Mr. Calhoun, 21, has been among the relatively small group that comes out at

night, relishing a confrontation with the police. He carries an attitude that

frustrates most protesters who have remained peaceful. But he does not really

care.

On this evening, he had a bandanna tied around his neck. He bounced around and

gazed at his surroundings with a giddy smile.

“Never thought I’d live to see hell on earth,” he said. “And this is hell on

earth.”

The looting and the fighting with the police is all necessary, Mr. Calhoun said.

Without it, no one would be paying attention, he said, and no way would they get

what they ultimately want: the police to stop harassing them.

“Just imagine if the dude gets found not guilty,” Mr. Calhoun said, referring to

Officer Wilson. “It’s going to be way more than looting going on.”

Tanzina Vega contributed reporting.

A version of this article appears in print on August 21, 2014,

on page A1 of the New York edition with the headline:

Anger, Hurt and Moments of Hope in Ferguson.

Anger, Hurt and Moments of Hope in Ferguson,

NYT, 20.8.2014,

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/21/us/in-ferguson-anger-hurt-

and-moments-of-hope.html

In Ferguson,

Scrutiny on Police Is Growing

AUG. 20, 2014

The New York Times

By JOHN ELIGON

and MICHAEL S. SCHMIDT

FERGUSON, Mo. — Early one morning in September 2011, an unarmed

31-year-old black man ran down a residential street here yelling at cars while

he pounded his hands on them.

“God is good,” the man, Jason Moore, said. “I am Jesus.”

The first officer to approach Mr. Moore told him to raise his hands and walk

toward him, according to a police report on the episode. But Mr. Moore, whose

family said he was mentally ill, started running toward the officer “in an

aggressive manner while swinging his fist in a pinwheel motion,” the officer

said in the report. And when he failed to obey commands to get on the ground,

the officer took out his Taser gun and fired it at him, the report said.

Mr. Moore fell to the ground, but after he tried to get up, the officer fired

the Taser twice more into him. Mr. Moore let out a raspy sound and stopped

breathing. He was pronounced dead soon after.

Mr. Moore’s death and how it was handled by the Ferguson Police Department are

now receiving renewed scrutiny after one of the department’s officers, Darren

Wilson, killed Michael Brown, an unarmed 18-year old, on Aug. 9. On Tuesday,

relatives of Mr. Moore filed two lawsuits against the Police Department in

federal court, saying that the department wrongfully killed him. The suit was

one of several filed in recent years that raised questions about excessive use

of force or civil rights violations by the Ferguson Police Department.

The police contend that they behaved properly in all of those cases, and none of

the lawsuits has yet led to a judgment against the department. But critics

assert that the complaints show a pattern of violent behavior or weak discipline

within the force — and say that the department’s conduct should be closely

investigated by the Justice Department, which has already opened an inquiry into

Mr. Brown’s death.

Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr., who visited Ferguson on Wednesday, and top

Justice Department officials have begun weighing whether to open just such a

broader civil rights review of Ferguson’s police practices, according to law

enforcement officials who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss

internal talks. Their discussion has been prompted in part by past complaints

against the force, including a 2009 case in which a man said that four police

officers beat him, then charged him with damaging government property — by

getting blood on their uniforms. That case is now the subject of one of the

lawsuits against the department.

During his daylong visit, Mr. Holder met with local and state officials,

including Gov. Jay Nixon, but also with a group of residents that included Mr.

Moore’s sister, Molyrik Welch, 27, who described her brother’s death. “A lot has

happened here,” Ms. Welch said after the meeting. She added that Mr. Holder had

promised that “things were going to change.”

Before a briefing at local F.B.I. headquarters, Mr. Holder promised that the

investigation into Mr. Brown’s death would be “thorough and fair” and that “very

experienced” prosecutors and agents had been assigned. “We’re looking for

violations of federal criminal civil rights statutes,” he said. But at another

stop, a meeting with residents at a community college, he also spoke in deeply

personal terms about his own problems with the police when he was a young man.

Saying he could “understand that mistrust” that many young blacks feel toward

the police, Mr. Holder recalled twice being pulled over on the New Jersey

Turnpike and having his car searched. “I remember how humiliating that was and

how angry I was and the impact it had on me,” Mr. Holder told the group.

He also recounted being stopped by the police in Georgetown, an upscale section

of Washington, because he was running to see a film. “I wasn’t a kid. I was a

federal prosecutor. I worked at the United States Department of Justice,” he

said. “So I’ve confronted this myself.”

Mr. Holder continued: “We need concrete action to change things in this country.

The same kid who got stopped on the New Jersey freeway is now the attorney

general of the United States. This country is capable of change. But change

doesn’t happen by itself.”

For most of Wednesday morning and early afternoon, the stretch of West

Florissant Avenue that has been the center of protest and confrontation turned

quiet enough to seem like any other commercial thoroughfare — save for the

pieces of plywood covering smashed store windows here and there.

As evening came, a sparse crowd milled, caught up briefly in a heavy downpour.

At one point, tensions flared when a couple identifying themselves as Chuck and

Dawn showed up along the route with signs supporting Officer Wilson. “Justice is

for Everybody — Even P.O. Wilson,” one of the signs read. Some protesters began

to crowd around and jeer, while others urged calm.

As the shouting grew louder and a water bottle was thrown, the police stepped in

and spirited the couple away from the crowd.

Also Wednesday, the St. Louis County Police Department said that an officer from

a local police department had been suspended after he pointed a semiautomatic

rifle at a peaceful protester following a verbal exchange on Tuesday night. In a

news release, the county police called the officer’s action “inappropriate,”

saying that a police sergeant had immediately escorted him away from the scene.

The episode involving Mr. Moore began at 6:46 a.m. on Sept. 17, 2011, when an

officer was sent in response to reports that Mr. Moore was running naked through

the streets, according to police reports. “I exited my patrol vehicle and

advised Jason to put his hands in the air and to walk my way,” the officer said

in a statement he filed afterward. Mr. Moore, the officer said, began moving

aggressively toward him, and despite several commands to stop, he did not.

“Jason continued to charge, at the time I deployed one five-second burst from

the Taser,” the officer said in the report. “The Taser darts made contact with

Jason on his left side of his chest and the right thigh.”

The officer said that after the initial shot, Mr. Moore fell to the ground and

then tried to get back on his feet. Again, Mr. Moore ignored commands to remain

where he was, the officer said. “In fear for my safety and the safety of Jason,

I administered a second five-second burst,” the officer said.

Continue reading the main story Continue reading the main story

As another officer arrived at the scene and got out of his vehicle, Mr. Moore

tried for a third time to get up. Mr. Moore again ignored commands to remain on

the ground, and the officer used the Taser gun on him again.

The officer who had just arrived handcuffed Mr. Moore and laid him on his

stomach, at which point emergency medical responders were sent to the scene.

Another officer tried to speak with Mr. Moore but received no response,

according to the police reports.

One of the lawsuits filed by Mr. Moore’s relatives says that the officers left

Mr. Moore face down and did not monitor his vital signs.

According to the police reports, about a minute after Mr. Moore was handcuffed,

the officer noticed that he was not breathing and removed the handcuffs. The

officers rolled Mr. Moore over and began administering CPR for several minutes.

“Moore would seem to start to breathe on his own and stop,” one of the police

reports said.

Mr. Moore was taken to a hospital, where he was pronounced dead.

In one of their lawsuits, the family asserts that Mr. Moore was unarmed and

“suffering from a psychological disorder and demonstrated clear signs of mental

illness.” A lawyer for the family declined to comment, or to explain why it had

taken three years to file the lawsuit.

But in an interview posted on YouTube last week, Mr. Moore’s sister said the

family had been unable to find a lawyer willing to handle the case until

recently.

John Eligon reported from Ferguson, and Michael S. Schmidt from Washington.

Reporting was contributed by Mosi Secret, Joseph Goldstein and Dan Barry from

Ferguson, Matt Apuzzo from Washington, and Kitty Bennett from Seattle.

A version of this article appears in print on August 21, 2014,

on page A15 of the New York edition with the headline: Scrutiny on the Police Is

Building in Ferguson.

In Ferguson, Scrutiny on Police Is Growing,

NYT, 20.8.2014,

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/21/us/

in-ferguson-scrutiny-on-police-is-growing.html

Calling for Calm in Ferguson,

Obama Cites Need

for Improved Race Relations

AUG. 18, 2014

The New York Times

By JULIE HIRSCHFELD DAVIS

WASHINGTON — President Obama called for calm and healing in

Ferguson, Mo., on Monday even as he acknowledged the deep racial divisions that

continue to plague not only that St. Louis suburb but cities across the United

States.

“In too many communities around the country, a gulf of mistrust exists between

local residents and law enforcement,” Mr. Obama said at the White House. “In too

many communities, too many young men of color are left behind and seen only as

objects of fear.”

“We’ve made extraordinary progress” in race relations, he said, “but we have not

made enough progress.”

Mr. Obama’s comments were a notable moment for the first African-American

president during the most racially fraught crisis of his time in office, set off

by the fatal shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager, by the

police. Mr. Obama and his administration are working to restore peace in

Ferguson and ensure an evenhanded investigation into the shooting all while

responding to anger — in Missouri and elsewhere — among blacks about what they

say is systemic discrimination by law enforcement officials.

“To a community in Ferguson that is rightly hurting and looking for answers, let

me call once again for us to seek some understanding rather than simply holler

at each other,” the president said in his first extended comments on the chaos

there.

Mr. Obama took pains to make clear that he was not issuing a blanket indictment

of either the protesting crowds or the law enforcement officers responding to

the demonstrations. He criticized both the “small minority” of protesters who he

said were exploiting the anger over Mr. Brown’s death to loot Ferguson stores as

well as the police who used violence of their own against demonstrators.

“While I understand the passions and the anger that arise over the death of

Michael Brown, giving in to that anger by looting or carrying guns and even

attacking the police only serves to raise tensions and stir chaos,” Mr. Obama

said during questioning by reporters.

Still, he emphasized, “there’s no excuse for excessive force by police or any

action that denies people the right to protest peacefully.”

Mr. Obama has mostly avoided speaking about himself or his agenda in explicitly

racial terms, but he has increasingly been less reticent to do so.

“I’m personally committed to changing both perception and reality,” Mr. Obama

said, making explicit reference to the $200 million, five-year initiative known

as “My Brother’s Keeper” that he started in February to address the plight of

black youth.

It was inspired in part by the fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin, another unarmed

black teenager, in 2012 in Florida and the acquittal of the man who killed him,

George Zimmerman.

“If I had a son,” Mr. Obama said after Mr. Martin’s death, “he’d look like

Trayvon.”

The president’s aides have said the situation in Ferguson has affected him in

similar ways.

“You have young men of color in many communities who are more likely to end up

in jail or in the criminal justice system than they are in a good job or in

college,” Mr. Obama said on Monday. He said part of his job was to “to get at

those root causes.”

The president spoke after receiving a formal briefing from Attorney General Eric

H. Holder Jr. on the situation in Ferguson.

Mr. Holder announced Sunday that a federal medical examiner would conduct an

independent autopsy of Mr. Brown.

The Police Department in Ferguson has been harshly criticized for refusing to

clarify the circumstances of the shooting and then escalating tensions by

responding to protests using military weapons and gear.

The president announced that Mr. Holder, who has made civil rights a cornerstone

of his tenure, will travel to Ferguson on Wednesday to monitor the situation.

Mr. Obama, when asked, did not say whether he would make a personal visit.

A version of this article appears in print on August 19, 2014,

on page A12 of the New York edition with the headline:

Calling for Calm in Ferguson, Obama Cites Need for Improved Race Relations.

Calling for Calm in Ferguson, Obama Cites Need

for Improved Race Relations,

NYT, 18.8.2014,

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/19/us/

calling-for-calm-in-ferguson-obama-cites-need-for-improved-race-relations.html

National Guard Troops

Fail to Quell Unrest in Ferguson

AUG. 19, 2014

The New York Times

By MONICA DAVEY,

JOHN ELIGON

and ALAN BLINDER

FERGUSON, Mo. — Violence erupted here once more on Monday night,

even as Missouri National Guard troops arrived, the latest in a series of

quickly shifting attempts to quell the chaos that has upended this St. Louis

suburb for more than a week.

In the days since an unarmed black teenager, Michael Brown, was shot to death by

a white police officer here on Aug. 9, an array of state and local law

enforcement authorities have swerved from one approach to another: taking to the

streets in military-style vehicles and riot gear; then turning over power to a

State Highway Patrol official who permitted the protests and marched along; then

calling for a curfew.

Early Monday, after a new spate of unrest, Gov. Jay Nixon said he was bringing

in the National Guard. Hours later, he said he was lifting the curfew and said

the Guard would have only a limited role, protecting the police command post.

Although the tactics changed, the nighttime scene did not.

Late Monday night, peaceful protests devolved into sporadic violence, including

gunshots, by what the authorities said was a small number of people, and

demonstrators were met with tear gas and orders to leave. Two men were shot in

the crowd, officials said in an early morning news conference, and 31 people —

some from New York and California — were arrested. Fires were reported in two

places. The police were shot at, the authorities said, but did not fire their

weapons.

“We can’t have this,” said Ron Johnson, a captain of the State Highway Patrol,

who stood near a table that held two guns and a Molotov cocktail that had been

seized. “We do not want to lose another life.”

Captain Johnson, who is coordinating security operations, gave no sense of

whether the police may change their tactics again on Tuesday, but he urged

peaceful protesters to demonstrate during daylight so as not to give cover to

“violent agitators,” and he pledged, despite the repeated nights of tumult,

“We’re going to make this neighborhood whole.”

Adding to the turbulence was confusion over the curfew. Although it was no

longer in force, around midnight the police demanded that the crowd disperse, a

fact the authorities attributed to increasingly unsafe conditions.

Also Monday, more details emerged from autopsies performed on Mr. Brown’s body.

One showed that he had been shot at least six times; another found evidence of

marijuana in his system.

In Washington, President Obama said Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. would go

to Ferguson on Wednesday to meet with F.B.I. agents conducting a federal civil

rights investigation into the shooting. He seemed less than enthusiastic about

the decision to call in the National Guard.

Mr. Obama said he had told the governor in a phone call on Monday that the Guard

should be “used in a limited and appropriate way.”

“I’ll be watching over the next several days to assess whether in fact it’s

helping rather than hindering progress in Ferguson,” said Mr. Obama, who

emphasized that the State of Missouri, not the White House, had called in the

Guard.

He again tried to strike a balance between the right of protest and approaches

to security.

“While I understand the passions and the anger that arise over the death of

Michael Brown, giving in to that anger by looting or carrying guns and even

attacking the police only serves to raise tensions,” Mr. Obama said.

As darkness set in, along West Florissant Avenue, one of the city’s main

thoroughfares and a center of the weeklong protests, demonstrators were required

to keep moving.

After more of than an hour of peaceful protests, some in the crowd began to

throw bottles at the police, who brought out armored vehicles and tactical

units. But many peacekeepers in the crowd formed a human chain and got the

agitators to back down.

At another point, as protesters gathered near a convenience store, some of them

threw objects; the police responded with tear gas.

And at nearly midnight, the police began announcing over loudspeakers that

people needed to leave the area or risk arrest after what the police say were

repeated gunshots and a deteriorating situation.

A few blocks away, at the police command post, National Guard members in Army

fatigues, some with military police patches on their uniforms, stood ready but

never entered the area where protesters were marching. State and local law

enforcement authorities oversaw operations there.

Residents seemed puzzled and frustrated by the continually changing approaches,

suggesting that the moving set of rules only worsened longstanding tensions over

policing and race in the town of 21,000.

“It almost seems like they can’t decide what to do, and like law enforcement is

fighting over who’s got the power,” said Antione Watson, 37, who stood near a

middle-of-the-street memorial of candles and flowers for Mr. Brown, the

18-year-old killed on a winding block here.

“First they do this, then there’s that, and now who can even tell what their

plan is?” Mr. Watson said. “They can try all of this, but I don’t see an end to

this until there are charges against the cop.”

The latest turn in law enforcement tactics — the removal of a midnight-to-5 a.m.

curfew imposed Saturday and the arrival of members of the Guard — followed a

chaotic Sunday night. Police officers reported gunfire and firebombs from some

among a large group, and they responded with tear gas, smoke canisters and

rubber bullets.

By Monday, the police seemed intent on taking control of the situation long

before evening and the expected arrival of protesters, some of them inclined to

provoke clashes. The authorities banned stationary protests, even during the

day, ordering demonstrators to continue walking, particularly in an area along

West Florissant, not far from where the shooting occurred. One of those told to

move along was the Rev. Jesse L. Jackson.

Six members of the Highway Patrol, plastic flex-ties within easy reach, stood

guard at a barbecue restaurant that has been a hub of the turmoil. Just north of

the restaurant, about 30 officers surrounded a convenience store that was

heavily damaged early in the unrest. Several people were arrested during the

day, including a photographer for Getty Images, Scott Olson, who was led away in

plastic handcuffs in the early evening.

Explaining his decision to call in the National Guard, Mr. Nixon recounted

details of the unrest on Sunday night, and he described the events as “very

difficult and dangerous as a result of a violent criminal element intent upon

terrorizing the community.”

Yet Mr. Nixon also emphasized that the Guard’s role would be limited to

providing protection for a police command center here, which the authorities say

came under attack. Gregory Mason, a brigadier general of the Guard, described

the arriving troops as “well trained and well seasoned.”

“With these additional resources in place,” said Mr. Nixon, a Democrat in his

second term, “the Missouri State Highway Patrol and local law enforcement will

continue to respond appropriately to incidents of lawlessness and violence and

protect the civil rights of all peaceful citizens to make their voices heard.”

While Mr. Obama and other leaders called for healing and more than 40 F.B.I.

agents fanned out around this city to interview residents about the shooting,

emotions remained raw, and the divide over all that had happened seemed only to

be growing amid multiple investigations and competing demonstrations.

A recent survey by the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press showed

that Americans were deeply divided along racial lines in their reaction to Mr.

Brown’s killing. The report showed that 80 percent of blacks thought the case

raised “important issues about race that need to be discussed,” while only 37

percent of whites thought it did.

Blacks surveyed were also less confident in the investigations into the

shooting, with 76 percent reporting little to no confidence in the

investigation, compared with 33 percent of whites.

Supporters of Darren Wilson, the Ferguson police officer who fired the fatal

shots, gathered outside a radio station over the weekend in St. Louis.

Mr. Brown is now the subject of three autopsies. The first was conducted by St.

Louis County, the results of which were delivered to the county prosecutor’s

office on Monday. That autopsy report showed evidence of marijuana in Mr.

Brown’s system, according to someone briefed on the report who was not

authorized to discuss it publicly before it was released.

Another, on Monday, was done by a military doctor as part of the Justice

Department’s investigation.

On Sunday, at the request of Mr. Brown’s family, the body was examined by Dr.

Michael Baden, a former New York City medical examiner.

The findings showed that he was shot at least six times in the front of his body

and that he did not appear to have been shot from very close range because no

powder burns were found on his body. But that determination could change if

burns were found on his clothing, which was not available for examination.

In a news conference on Monday, family members and Dr. Baden said that the

autopsy he had performed confirmed witness accounts that Mr. Brown was trying to

surrender when he was killed.

Daryl Parks, a lawyer for the family, said the autopsy proved that the officer

should have been arrested. The bullet that killed Mr. Brown entered the top of

his head and came out through the front at an angle that suggested he was facing

downward when he was killed, Mr. Parks said. The autopsy did not show what Mr.

Brown was doing when the bullet struck his head.

“Why would he be shot in the very top of his head, a 6-foot-4 man?” Mr. Parks

said. “It makes no sense. And so that’s what we have. That’s why we believe that

those two things alone are ample for this officer to be arrested.”

Piaget Crenshaw, who told reporters that she had witnessed Mr. Brown’s death

from her nearby apartment, seemed unsurprised by the eruptions of anger, which

have left schools closed and some businesses looted. “This community had

underlying problems way before this happened,” Ms. Crenshaw said. “And now the

tension is finally broken.”

For businesses here, the days and long nights have been costly and frightening.

At Dellena Jones’s hair salon, demonstrators had tossed concrete slabs into the

business as Ms. Jones’s two children prepared for what they had expected to be a

first day back to school.

“I had a full week that went down to really nothing,” she said of her business,

which has sat mostly empty. “They’re too scared to come.” As she spoke, a man

walked by and shouted, “You need a gun in there, lady!”

In his news conference, Mr. Obama said that most protesters had been peaceful.

“As Americans, we’ve got to use this moment to seek out our shared humanity

that’s been laid bare by this moment,” Mr. Obama said.

Frances Robles and Tanzina Vega contributed reporting from Ferguson, and Julie

Hirschfeld Davis and Matt Apuzzo from Washington.

A version of this article appears in print on August 19, 2014,

on page A1 of the New York edition with the headline:

Fitful Night in Ferguson as National Guard Arrives.

National Guard Troops Fail to Quell Unrest in

Ferguson, NYT, 19.8.2014,

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/20/us/ferguson-missouri-protests.html

Frustration in Ferguson

AUG. 17, 2014

The New York Times

The Opinion Pages | Op-Ed Columnist

Charles M. Blow

The response to the killing of the unarmed teenager Michael Brown

— whom his family called the “gentle giant” — by the Ferguson, Mo., police

officer Darren Wilson — who was described by his police chief as “a gentle,

quiet man” and “a gentleman” — has been anything but genteel.

There have been passionate but peaceful protests to be sure, but there has also

been some violence and looting. Police forces in the town responded with an

outlandish military-like presence more befitting Baghdad than suburban Missouri.

There were armored vehicles, flash grenades and a seemingly endless supply of

tear gas — much of it Pentagon trickle-down. There were even officers perched

atop vehicles, in camouflage and body armor, pointing weapons in the direction

of peaceful protesters.

Let me be clear here: Pointing a gun at an innocent person is an act of violence

and provocation.

Americans were aghast at the images, and condemnation was swift and bipartisan.

The governor put the state’s Highway Patrol in charge of security. Tensions

seemed to subside, for a day.

But then on Friday, when releasing the name of the officer who did the shooting,

the police chief also released details and images of a robbery purporting to

show Brown stealing cigars from a local convenience store and pushing a store

employee in the process.

The implication seemed to be that Wilson was looking for the person who

committed the convenience store crime when he encountered Brown. But, later in

the day, the chief said Wilson didn’t know Brown was a robbery suspect when they

encountered each other.

Something seemed off. The police chief’s decision to release the details of the

robbery and the images — without releasing an image of Wilson — struck many as

perfidious. In a strongly worded statement, Brown’s family and attorneys accused

the chief of attempting to assassinate the character of the dead teen.

Some also deemed it an attempt at distraction from the central issue: An officer

shot an unarmed teenager who witnesses claim had raised his hands in surrender

when at least some of the shots were fired, which the family and its attorneys

called “a brutal assassination of his person in broad daylight.”

The Justice Department is even investigating whether Brown’s civil rights were

violated. This would include the excessive use of force. As the department makes

clear, this “does not require that any racial, religious, or other

discriminatory motive existed.”

It’s impossible to truly know the chief’s motives for his decision to release

the robbery information at the same time as the officer’s name, but the effect

was clear: That night, a fragile peace was shattered. There was more looting,

although peaceful protesters struggled heroically to block the violent ones.

On Saturday, the governor issued a midnight curfew for the town. A small band of

protesters defied it and some were arrested.

The community is struggling to find its way back to normalcy, but it would

behoove us to dig a bit deeper into the underlying frustrations that cause a

place like Ferguson to erupt in the first place and explore the untenable nature

of our normal.

Continue reading the main story Continue reading the main story

Yes, there are the disturbingly repetitive and eerily similar circumstances of

many cases of unarmed black people being killed by police officers. This

reinforces black people’s beliefs — supportable by actual data — that blacks are

treated less fairly by the police.

But I submit that this is bigger than that. The frustration we see in Ferguson

is about not only the present act of perceived injustice but also the calcifying

system of inequity — economic, educational, judicial — drawn largely along

racial lines.

In 1951, Langston Hughes began his poem “Harlem” with a question: “What happens

to a dream deferred?” Today, I must ask: What happens when one desists from

dreaming, when the very exercise feels futile?

The discussion about issues in the black community too often revolves around a

false choice: systemic racial bias or poor personal choices. In fact, these

factors are interwoven like the fingers of clasped hands. People make choices

within the context of their circumstances and those circumstances are affected —

sometimes severely — by bias.

These biases do material damage as well as help breed a sense of

disenfranchisement and despair, which in turn can have a depressive effect on

aspiration and motivation. This all feeds back on itself.

If we want to truly address the root of the unrest in Ferguson, we have to ask

ourselves how we can break this cycle.

Otherwise, Hughes’s last words of “Harlem,” referring to the dream deferred,

will continue to be prophetic: “does it explode?”

A version of this op-ed appears in print on August 18, 2014,

on page A19 of the New York edition with the headline: Frustration in Ferguson.

Frustration in Ferguson, NYT, 17.8.2014,

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/18/opinion/

charles-m-blow-frustration-in-ferguson.html

Around St. Louis, a Circle of Rage

AUG. 16, 2014

The New York Times

By TANZINA VEGA and JOHN ELIGON

FERGUSON, Mo. — Garland Moore, a hospital worker, lived in this

St. Louis suburb for much of his 33 years, a period in which a largely white

community has become a largely black one.

He attended its schools and is raising his family in this place of suburban

homes and apartment buildings on the outskirts of a struggling Midwest city. And

over time, he has felt his life to be circumscribed by Ferguson’s demographics.

Mr. Moore, who is black, talks of how he has felt the wrath of the police here

and in surrounding suburbs for years — roughed up during a minor traffic stop

and prevented from entering a park when he was wearing St. Louis Cardinals red.

And last week, as he stood at a vigil for an unarmed 18-year-old shot dead by

the police — a shooting that provoked renewed street violence and looting early

Saturday — Mr. Moore heard anger welling and listened to a shout of: “We’re

tired of the racist police department.”

“It broke the camel’s back,” Mr. Moore said of the killing of the teenager,

Michael Brown. Referring to the northern part of St. Louis County, he continued,

“The people in North County — not just African-Americans, some of the white

people, too — they are tired of the police harassment.”

The origins of the area’s complex social and racial history date to the 19th

century when the city of St. Louis and St. Louis County went their separate

ways, leading to the formation of dozens of smaller communities outside St.

Louis. Missouri itself has always been a state with roots in both the Midwest

and the South, and racial issues intensified in the 20th century as St. Louis

became a stopping point for the northern migration of Southern blacks seeking

factory jobs in Detroit and Chicago.

As African-Americans moved into the city and whites moved out, real estate

agents and city leaders, in a pattern familiar elsewhere in the country,

conspired to keep blacks out of the suburbs through the use of zoning ordinances

and restrictive covenants. But by the 1970s, some of those barriers had started

to fall, and whites moved even farther away from the city. These days, Ferguson

is like many of the suburbs around St. Louis, inner-ring towns that accommodated

white flight decades ago but that are now largely black. And yet they retain a

white power structure.

Although about two-thirds of Ferguson residents are black, its mayor and five of

its six City Council members are white. Only three of the town’s 53 police

officers are black.

Turnout for local elections in Ferguson has been poor. The mayor, James W.

Knowles III, noted his disappointment with the turnout — about 12 percent — in

the most recent mayoral election during a City Council meeting in April.

Patricia Bynes, a black woman who is the Democratic committeewoman for the

Ferguson area, said the lack of black involvement in local government was partly

the result of the black population’s being more transient in small

municipalities and less attached to them.

There is also some frustration among blacks who say town government is not

attuned to their concerns.

Aliyah Woods, 45, once petitioned Ferguson officials for a sign that would warn

drivers that a deaf family lived on that block. But the sign never came. “You

get tired,” she said. “You keep asking, you keep asking. Nothing gets done.”

Mr. Moore, who recently moved to neighboring Florissant, said he had attended a

couple of Ferguson Council meetings to complain that the police should be

patrolling the residential streets to try to prevent break-ins rather than lying

in wait to catch people for traffic violations.

This year, community members voiced anger after the all-white, seven-member

school board for the Ferguson-Florissant district pushed aside its black

superintendent for unrevealed reasons. That spurred several blacks to run for

three board positions up for election, but only one won a seat.

The St. Louis County Police Department fired a white lieutenant last year for

ordering officers to target blacks in shopping areas. That resulted in the

department’s enlisting researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles,

to study whether the department was engaging in racial profiling.

And in recent years, two school districts in North County lost their

accreditation. One, Normandy, where Mr. Brown graduated this year, serves parts

of Ferguson. When parents in the mostly black district sought to allow their

children to transfer to schools in mostly white districts, they said, they felt

a backlash with racial undertones. Frustration with underfunded and

underperforming schools has long been a problem, and when Gov. Jay Nixon held a

news conference on Friday to discuss safety and security in Ferguson, he was

confronted with angry residents demanding to know what he would do to fix their

schools.

Ferguson’s economic shortcomings reflect the struggles of much of the region.

Its median household income of about $37,000 is less than the statewide number,

and its poverty level of 22 percent outpaces the state’s by seven percentage

points.

In Ferguson, residents say most racial tensions have to do with an overzealous

police force.

“It is the people in a position of authority in our community that have to come

forward,” said Jerome Jenkins, 47, who, with his wife, Cathy, owns Cathy’s

Kitchen, a downtown Ferguson restaurant.

“What you are witnessing is our little small government has to conform to the

change that we are trying to do,” Mr. Jenkins added. “Sometimes things happen

for a purpose; maybe we can get it right.”

Ferguson’s police chief, Thomas Jackson, has been working with the Justice

Department’s community relations team on improving interaction with residents.

At a news conference here last week, he acknowledged some of the problems.

“I’ve been trying to increase the diversity of the department ever since I got

here,” Chief Jackson said, adding that “race relations is a top priority right

now.” As for working the with Justice Department, he said, “I told them, ‘Tell

me what to do, and I’ll do it.’ ”

Although experience and statistics suggest that Ferguson’s police force

disproportionately targets blacks, it is not as imbalanced as in some

neighboring departments in St. Louis County. While blacks are 37 percent more

likely to be pulled over compared with their proportion of the population in

Ferguson, that is less than the statewide average of 59 percent, according to

Richard Rosenfeld, a professor of criminology at the University of Missouri-St.

Louis.

In fact, Mr. Rosenfeld said, Ferguson did not fit the profile of a community

that would be a spark for civil unrest. The town has “pockets of disadvantage”

and middle and upper-middle income families. He said Ferguson had benefited in

the last five to 10 years from economic growth in the northern part of the

county, such as the expansion of Express Scripts, the Fortune 500 health care

giant.

“Ferguson does not stand out as the type of community where you would expect

tensions with the police to boil over into violence and looting,” Mr. Rosenfeld

said.

But the memory of the region’s racial history lingers.

In 1949, a mob of whites showed up to attack blacks who lined up to get into the