|

Vocapedia >

Arts >

Painting, Sculpture > Sculpture

Gateshead, UK

The Angel of the North statue

is covered in snow,

as a yellow weather warning for

snow and ice remains in place

for the eastern coast,

stretching from Scotland to

East Anglia

Photograph: Owen Humphreys

PA

A helicopter crash and a cat in

the wild:

photos of the day – Friday

The Guardian’s picture editors

select photographs

from around the world

G

Fri 1 Dec 2023

13.43 CET

https://www.theguardian.com/news/gallery/2023/dec/01/

helicopter-crash-and-cat-in-wild-photos-of-the-day-friday

Gateshead, England

A dusting of snow decorates the

Angel of the North in Gateshead

Photograph: Owen Humphreys

PA

A Nasa capsule and wintry

weather: Monday’s best photos

The Guardian’s picture editors

select photo highlights from around the world

G

Mon 12 Dec 2022 12.57 GMT

https://www.theguardian.com/news/gallery/2022/dec/12/

a-nasa-capsule-and-wintry-weather-mondays-best-photos

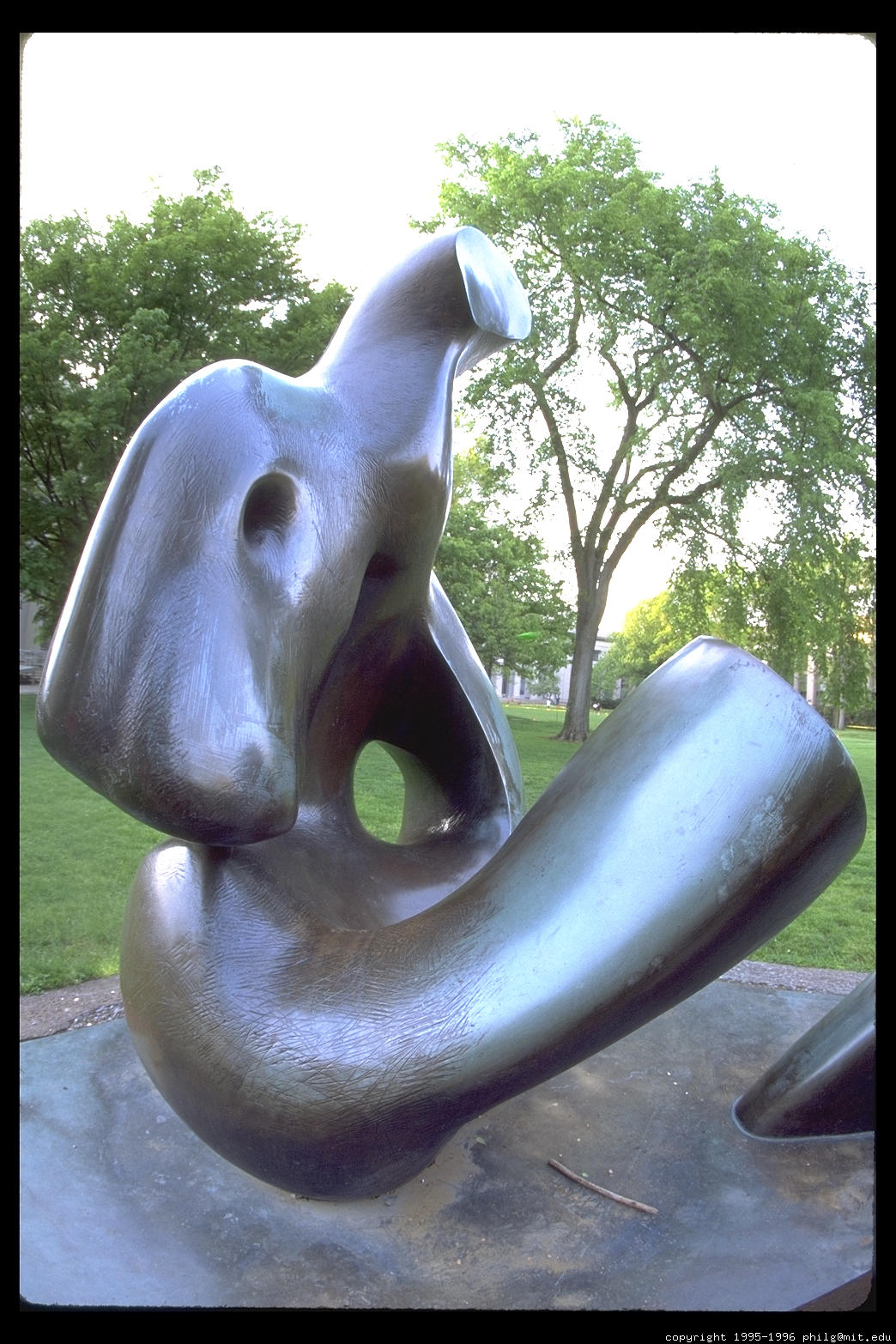

Henry Moore sculpture.

Reclining Figure (1951)

outside the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge,

is characteristic of Moore's sculptures,

with an abstract female figure intercut

with voids.

There are several bronze versions of this sculpture,

but this one is made from

painted plaster.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Moore

Image: HenryMoore RecliningFigure 1951.jpg

from Wikipedia

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e1/HenryMoore_RecliningFigure_1951.jpg

added 25 July 2007

Henry Moore sculpture.

Killian Court. Massachusetts Institute of

Technology

Canon EOS-5, 15mm fisheye lens

copyright 1995-1996

philg@mit.edu

http://photo.net/photo/pcd2388/henry-moore-23.tcl

added 25 July 2007

Anthony caro's "Jupiter."

Mitchell-Inness & Nash

A Passage for the Master of Heavy Metal

NYT

July 25,

2007

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/25/

arts/design/25caro.html

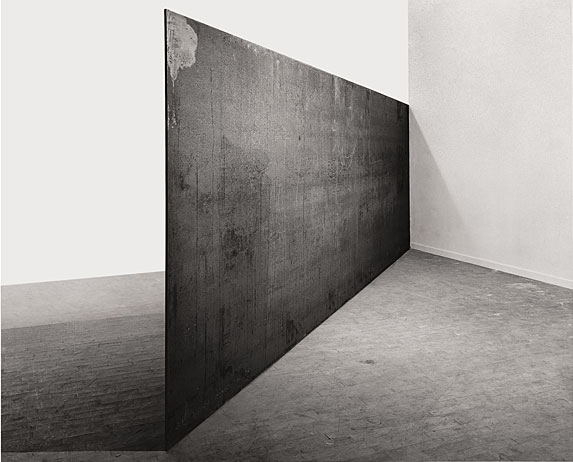

Strike: To Roberta and Rudy, 1969–71.

Hot-rolled steel, 96 x 288 x 1 inches.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum,

Panza Collection. 91.3871.

© 2005 Richard Serra/Artists Rights Society (ARS),

New York.

http://www.guggenheimcollection.org/site/artist_work_md_144A_7.html

Antony Gormley > London sculpture

1 of 31 life-size figures on London's skyline

Author: Antony McCallum

Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Gormley-event-horizon.jpg

sculpture

'performing' sculptures

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/jul/31/

tate-2015-programme-calder-hepworth-pollock

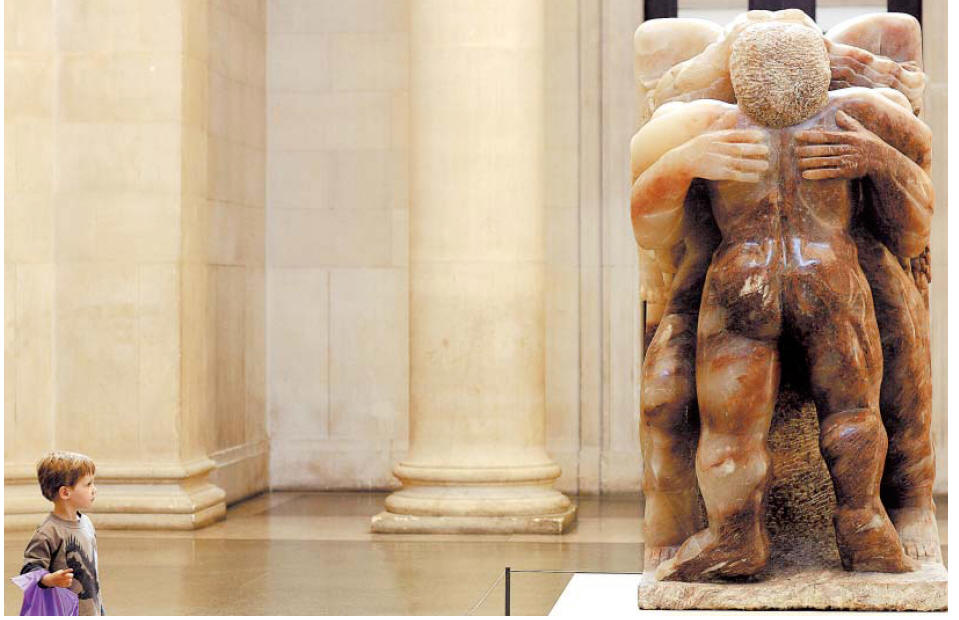

Presence: The

Art of Portrait Sculpture – review 3

June 2012

Holburne Museum, Bath

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2012/jun/03/

presence-art-portrait-sculpture-holburne-review

sculptor

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/28/

arts/design/richard-serra-death-notebook.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/11/

arts/design/john-mccracken-sculptor-of-geometric-forms-dies-at-76.html

women sculptors UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/may/22/

sarah-lucas-polly-morgan-female-sculptors

workshop UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/apr/29/

michael-landy-patron-destruction

model

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/15/

obituaries/audrey-munson-overlooked.html

grand sculptures

> Antony Gormley UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/

gormley

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Angel_of_the_North

https://www.theguardian.com/news/gallery/2023/dec/01/

helicopter-crash-and-cat-in-wild-photos-of-the-day-friday

https://www.theguardian.com/news/gallery/2022/dec/12/

a-nasa-capsule-and-wintry-weather-mondays-best-photos

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2010/jun/03/antony-gormley-lights-white-cube

https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/news/

gormley-reveals-labyrinthine-artwork-1990527.html - 3

June 2010

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/gallery/2010/mar/10/antony-gormley-new-york-sculptures

http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art-and-architecture/news/

modern-public-artworks-are-crap-says-gormley-this-is-how-it-should-be-done-791922.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/arts/gallery/2007/may/15/1?picture=329852334

http://www.guardian.co.uk/arts/gallery/2007/may/03/art?picture=329805762

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2005/jun/25/

art

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2005/jun/25/

art

Antony Gormley > angel of

the North UK

https://www.theguardian.com/news/gallery/2023/dec/01/

helicopter-crash-and-cat-in-wild-photos-of-the-day-friday

https://www.theguardian.com/news/gallery/2022/dec/12/

a-nasa-capsule-and-wintry-weather-mondays-best-photos

metal sculptures > Richard Serra UK

https://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2007/

serra/

http://www.guardian.co.uk/arts/features/story/0,11710,1329744,00.html

http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio3/johntusainterview/serra_transcript.shtml

metal sculptures

> Anthony Caro UK

http://arts.guardian.co.uk/art/news/story/0,,2134196,00.html

http://observer.guardian.co.uk/review/story/0,,2078342,00.html

http://arts.guardian.co.uk/features/story/0,,1385495,00.html

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2004/mar/08/

arts.artsnews1

metal

sculpture > torqued metal rings USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/28/

arts/design/richard-serra-death-notebook.html

metal

sculpture > curves USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/28/

arts/design/richard-serra-death-notebook.html

geometric forms

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/11/

arts/design/john-mccracken-sculptor-of-geometric-forms-dies-at-76.html

neon sculptures

> Chryssa USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/19/

arts/chryssa-artist-who-saw-neons-potential-as-a-medium-dies-at-79.html

kinetic

sculpture UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/apr/29/

michael-landy-patron-destruction

sound sculpture / a sound piece

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2007/apr/17/

art.jonathanjones

https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2004/oct/12/1

fibreglass sculpture

steel

plastic

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/15/arts/design/15kauffman.html

papier mache UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2022/may/07/

household-favourites-everyday-objects-in-papier-mache-bernie-kaminski-in-pictures

ceramics

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/25/

arts/design/ken-price-sculptor-who-helped-elevate-ceramics-dies-at-77.html

steel

crushed-up cars

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/dec/22/

john-chamberlain-sculptor-cars-dies

light

sculptures UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/article/2024/jun/19/

anthony-mccall-light-sculptures-alive-tate-modern

sculptural installation

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/dec/05/

martin-boyce-turner-prize-winner

conceptual Art movement

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/18/

arts/design/michael-asher-artist-dies-at-69.html

conceptual artist

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/16/

arts/design/on-kawara-conceptual-artist-who-found-elegance-in-every-day-dies-at-81.html

British pop art

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2005/apr/22/

obituaries

statue

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2012/oct/11/

damien-hirst-statue-monstrosity

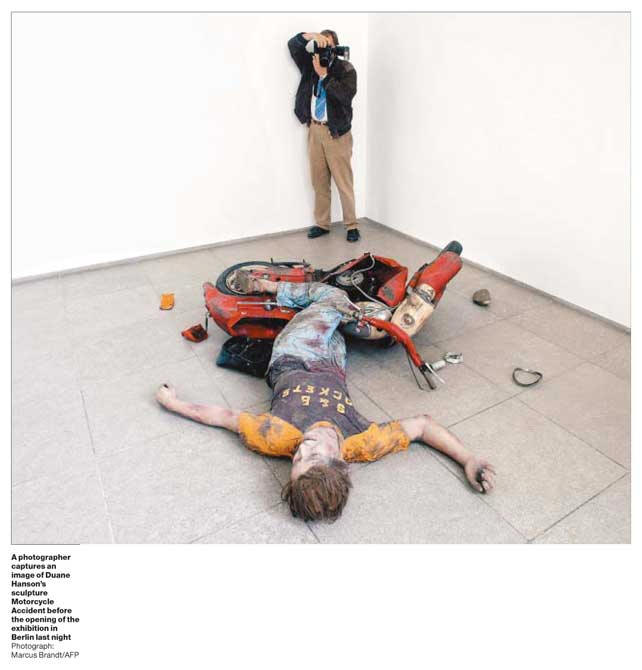

Duane Hanson USA 1925-1996

American Photorealist Sculptor

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Duane_Hanson

carve

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2011/aug/25/

female-uk-sculptures-women

Taking the Tate into the future

Charlotte Higgins, arts correspondent

The Guardian

p. 9

Monday September 12, 2005

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2005/sep/12/

arts.artsnews1

iconoclasm

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/jul/05/

tate-art-under-attack-british-iconoclasm

The Guardian p. 3 22

September 2004

Charles Ray's "Unpainted Sculpture" (1997)

Photograph: Craig Lassig for The New York Times

April

15, 2005

NYT

https://www.nytimes.com/2005/04/15/

arts/design/probing-fringes-finding-stars.html

Corpus of news articles

Arts > Sculpture

Art Review | Alexander Calder

Calder at Play:

Finding Whimsy in Simple Wire

October 17, 2008

The New York Times

By HOLLAND COTTER

Is art basically glorified child’s play, extending into adulthood, through a

lifetime, picking up ideas and gaining finesse as it goes? That’s one way to

think of “Alexander Calder: The Paris Years, 1926-1933” at the Whitney Museum of

American Art. Few exhibitions have focused so intently on one artist’s child

within. It’s a Peter Pan syndrome show.

It’s also a large show, with a chunky, charming catalog. Yet it feels intimate

and light, not to say lightweight. Gallery by gallery, it’s as suspenseful and

insubstantial as a magic act: what will the artist pull from his sleeve next?

The story it tells is like a Kids R Us version of early 20th-century Modernism,

with a grown-up surprise at the end.

Calder didn’t start out with ambitions to be an artist; if anything, he was

pulled in the opposite direction. He watched his father, a professional

sculptor, fret over commissions and struggle with money. So when it came time

for college the young Calder chose an engineering school in New Jersey over art

school.

But of course he was an artist, a natural. He may just not have known at first

what that meant. Even as a child he was astonishingly inventive. The tiny figure

of a rocking-horse-style bird shaped from brass sheeting is, for economy of form

and conceptual daring, one of the more radical works in the show. He made it

when he was 11.

He made stuff all the time. He was one of those people with nonstop eyes and

hands: every scrap of stray matter was a candidate for transformation. Give him

some wire, clothespins and a scrap of cloth and, presto chango, you had a bird

or a cow or a circus clown: nothing, then something, which is what magic is.

There’s a hyperactive pace to his early career. While working at engineering

jobs after college, he was also drawing like crazy and designing toys. In 1923

he enrolled at the Art Students League to study painting; John Sloan and George

Luks were his teachers. At the same time he took on illustrating gigs for

publications like The New Yorker and The National Police Gazette.

His academic drawings from the time are gauche and ordinary. The

staying-still-in-a-studio they required obviously cramped his style. Much

fresher is the dashed-off, manic-looking magazine work. And his Ash Can

School-type paintings of New York scenes — a drunken party; a trip to the

Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus — have a gawky spark of life. Then

there are his pen-and-ink drawings of zoo animals. They’re in a different

category, almost by a different artist, one more relaxed and assured. Often done

as one continuous line, they are like an effortlessly sophisticated form of

penmanship. So are some of the openwork sculptures of bent and twisted wire that

he began to experiment with at this time.

In 1926, with all these balls in the air, he suddenly moved to Paris, because

motion for him was a stimulant and because he felt that Paris was the hot place

to be, which it was. With its crowded cafes, charged thinking, endless talking

and jumpy personalities, the city was hyperkinetic. Calder fell in love with it.

And, although he continued to return to New York for long stretches, he made

Paris his home base for seven years.

His wire sculpture took off there. Several examples in the form of portrait

heads are the first thing you see when you step off the elevator on the

Whitney’s fourth floor. They’re an arresting sight, in a gently wow-inspiring

way. Wows were what Calder was after, along with chuckles and satisfied ahs. He

was a showman, a performer. “See what I can do, right before your eyes, without

even trying?” his art seems to say.

For his purposes industrial steel wire was an ideal medium. It was cheap,

malleable, portable and equally adaptable to precision work and doodling, which

to him were almost the same thing. Wire was like three-dimensional ink; it was a

means of combining drawing and sculpture in space.

In the Paris years he used it for portraiture. His first subject was a star he

admired from afar, Josephine Baker. She was the toast of the town in the 1920s.

One look at film clips of her dancing a semi-nude Charleston tells you why.

Calder made five small Baker figures; four are in the show. With their tiny

heads, spiraling breasts and long, long single-strand legs, they catch something

of the image Baker wanted to project: that of an ethnographic specimen come to

irrepressibly self-amused life.

He made other figures too, of the tennis champion Helen Wills, of John D.

Rockefeller playing golf. They are the work of a pop illustrator, clever but

nothing special. But for people he actually knew, portrait heads were the form

of choice. Of the 18 examples in the show, most depict people Calder had met in

avant-garde circles in Paris, including celebrity friends like Edgard Varèse,

Joan Miró and Alice Prin, the multitasking muse better known as Kiki de

Montparnasse. You can see why Calder did these likenesses: they were an

attention-getting novelty; they advertised his skill; they gave him a pretext to

network.

They also look as if they were fun to make. One of the attractive features of

Calder’s art from this period is its gee-I-could-do-that unpretentiousness. At

the same time each is a fabulous little virtuosic feat, abstract but exacting.

Set on bases or freely suspended, and casting subtle shadows — Jennifer Tipton,

the theatrical lightning designer, was in charge of illumination — the portraits

have the wit and refinement that will show up again in Calder’s first abstract

sculptures.

Refinement is not a quality associated with the famously funky tabletop

assemblage known as Calder’s Circus. A prime draw of the Whitney’s permanent

collection, it has rarely been off view since the museum acquired it 25 years

ago. But it gets a rethinking here.

Up to now it has been exhibited as a compact, one-ring affair with its many tiny

handmade figures — clowns, acrobats, animal trainers and so on — doing all the

varied things they do at once. The show’s curators, Joan Simon of the Whitney

and Brigitte Leal of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, have separated the components

into individual acts meant to be seen as taking place sequentially, a format

that corresponds to the way Calder himself presented the work in live

performances.

You can see him giving one in a 1955 film by Jean Painlevé, which is in the

show. Calder introduces the figures silently one by one, manipulating them and

activating the low-tech mechanisms (cranks, pull-strings, air hoses) that

animate their activities. If, like me, you’ve always found Calder’s Circus a

little too cute for comfort, the film may change your mind.

When at one point Calder slowly and carefully removes layer after layer of

hand-sewn costumes from one clown figure until he arrives at what looks like a

skeleton, it’s hard to known whether you’re seeing a circus or a medieval

morality play. No wonder the original Paris performances pulled in the savvy

audiences they did. Jean Cocteau, Marcel Duchamp and Piet Mondrian were among

the many vanguard types who sat on crates and watched with rapt attention.

The Whitney show’s real shock comes a bit later, though, in the last three

galleries, when Calder the polymath entertainer becomes Calder the Modern

sculptor. The shift happened almost literally overnight. In October 1930 he

visited Mondrian’s Paris studio; instantly he became an abstract artist. And for

some people Calder starts to become interesting only at this point. No more

Kikis and tennis players. Now everything is floating circles and curving lines

anchored by balls in space.

But two things stayed constant: motion and play. For conservation reasons only

one sculpture in the Whitney show is now motorized as intended; others can be

seen in action on film. And action is the essence in a piece like “Small Sphere

and Heavy Sphere” (1932-33), which consists of two suspended wooden balls and,

set out on the gallery floor, a wooden box, four wine bottles, a can and a gong.

Nothing much, right? Until — as seen on film — the balls, attached to a

motorized bar, start to move in a slow circle, hitting a bottle, then the can,

then the gong. Music! (Varèse loved this piece.) Yet move a bottle an inch or

two this way or that and the performance changes. Turn on a fan or open a window

and you could create a new score. The game Calder is playing is a finely tuned,

verging on magical, game of chance. And it really is a game. And it really is

play.

“Alexander Calder: The Paris Years, 1926-1933”

remains at the Whitney Museum of

American Art,

945 Madison Avenue (at 75th Street),

through Feb. 15.

It will then

be at the Centre Pompidou, Paris,

from March 18 through July 20.

Calder at Play: Finding

Whimsy in Simple Wire,

NYT, 17.10.2008,

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/17/

arts/design/17cald.html

Modern public artworks are 'crap',

says Gormley.

This is how it should be

done

Thursday, 6 March 2008

The Independent

By Arifa Akbar,

Arts Correspondent

Antony Gormley made his name as the creator of grand sculptures with his

monumental Angel of the North. So it may surprise many artists attempting to

emulate his success to hear that he has condemned the current crop of modern

public artworks across the UK as "crap".

"On the whole," he said, "We have not reinvented the statue very convincingly

for the 21st century," adding "There is an awful lot of crap out there."

A decade after his experimental 65ft-high figure was erected in Gateshead,

Gormley said the success of the sculpture had inadvertently set a precedent for

the proliferation of unchallenging works of art in public spaces.

He singled out The Meeting Place statue of two lovers embracing at St Pancras

International Station for criticism. Other works he dislikes are a statue of

Churchill and Roosevelt on Bond Street and David Wynne's Boy With a Dolphin in

Chelsea.

He went on: "I don't like the way the Angel of the North has been used for some

kind of precedent to encourage people and local authorities looking for European

funding or investment. When we made the Angel, it was an experiment. We managed

to get lottery money and European funding but it was a huge risk."

To many, Gormley, who is currently on a shortlist for creating a sculpture for

the fourth plinth in London's Trafalgar Square, is the most prominent producer

of public art alive in Britain today. Aside from the Angel sculpture of 1998, he

also produced Another Place for Crosby Beach near Liverpool and Iron:Man, placed

in Birmingham's Victoria Square.

He said it was not the quantity of public artworks in Britain that offended him

but the prevailing lack of creativity.

"So much of the art of the 20th century has ended up being corralled into

museums. I would love to see more significant work in public spaces that is not

institutionalised – work that is truly everyone's. There are works that really

challenge you that maybe you don't understand at first but you keep going back

to see them because they niggle. But art placed in public spaces that does not

challenge does a disservice.

"A lot of public art is gunge, an excuse which says, 'we're terribly sorry to

have built this senseless glass and steel tower but here is this 20-foot bronze

cat'," he said.

The artist also felt that Britain needed a proper structure to shortlist and

judge commissions, similar to that currently in place in Germany and Holland,

which he claimed have greater forms of quality control for a commissioned piece

of public art.

"Here, the standards are very low [for] the way submissions are judged," he

said.

Gormley's outspoken comments came as he unveiled an indoor sculptural piece,

Lost Horizon, priced at £1.35m and displayed at White Cube Gallery in Mason's

Yard, London. It follows last year's public art project 'Event Horizon', which

he did with the Hayward Gallery, in which he placed several statues modelled on

his own body on buildings around central London.

Another new work, Firmament, priced at £850,000, is a geometrical structure

based on the human body and could also be suitable for outdoor display.

The artist joins a long-running debate on the value of public art which was

reinvigorated by Marjorie Trusted, senior curator of sculpture at the Victoria

and Albert Museum, who said many commissions were "disappointing, old-fashioned

and awkward" while Tim Knox, director of Sir John Soane's Museum in London,

dismissed them as "horrors".

Modern public artworks

are 'crap', says Gormley.

This is how it should be done, I, 6.3.2008,

http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art-and-architecture/news/modern-public-artworks-are-crap-says-gormley-this-is-how-it-should-be-done-791922.html

Art Review | Richard Prince

Pilfering a Culture Out of Joint

September 28, 2007

The New York TimeS

By ROBERTA SMITH

Richard Prince has heard America singing, and it is not in tune. The

paradoxically beautiful, seamless 30-year survey of his work at the Guggenheim

Museum catches many of our inharmonious country’s discontents and refracts them

back to us. The central message of this array of about 160 photographs,

drawings, paintings and sculptures, most of which incorporate images or objects

cribbed from popular culture, is that we won’t be getting along any time soon.

But in Mr. Prince’s view, little of life’s cacophony is real except the parts

deep inside all of us that are hardest to reach.

Mr. Prince has devoted his career to this surface unreality, attempting to

collect, count and order its ways. He has said that his goal is “a virtuoso

real,” something beyond real that is patently fake. But his art is inherently

corrosive; it eats through things. His specialty is a carefully constructed

hybrid that is also some kind of joke, charged by conflicting notions of high,

low and lower.

Frequent targets include the art world, straight American males and middle-class

virtue, complacency and taste. His work disturbs, amuses and then splinters in

the mind. It unsettles assumptions about art, originality and value, class and

sexual difference and creativity.

The work in the Guggenheim exhibition opening today, subtitled “Spiritual

America,” defines the nation’s culture as a series of weird, isolated

subcultures — from modernist abstraction to stand-up comedy to pulp-fiction

cover art — and gives them equal dignity. It begins on the ground floor with

“American Prayer,” a magnificent, haunting new sculpture for which the chassis

of a 1969 Charger, a classic muscle car, has been stripped bare and cantilevered

above the floor by a large block that merges with its hood. As aerodynamic as a

bird’s skull and as commodious as a double coffin, it is not on blocks but

lodged in one, like a stray bullet. Its bulky support suggests a pedestal, a

Minimalist box, an anchorage and an altar. It is spackled and Bondoed, ready for

its final, shiny coat, unlike the rest of the car. Together they form a memorial

to custom cars presented as an abstracted body awaiting resurrection or a

truncated crucifix lying in state.

Mr. Prince’s ancestors include Duchamp, Jasper Johns and especially Andy Warhol.

But unlike Warhol, he is much less interested in the stars than in the audience.

Thus he is just as much an heir to Walker Evans and Carson McCullers, with their

awareness of the common person.

Over the years, Mr. Prince has shown himself to be in touch with the same

shamed, shameless side of America that gave us tell-too-much talk shows, reality

TV and the current obsession with celebrity. Practically every last American

could find something familiar, if usually a bit unsettling, in his work. If he

were the Statue of Liberty, the words inscribed on his base might read: Give me

your tired, your poor, but also your traveling salesmen and faithless wives;

your biker girlfriends, porn stars, custom-car aficionados and wannabe

celebrities; as well as your first-edition book collectors (of which he is one).

It often seems that Mr. Prince has never met a piece of contemporary Americana

he couldn’t use. Customized checks with images of SpongeBob SquarePants or Jimi

Hendrix? He pastes them to canvas and paints on them. Mail-order fiberglass

hoods for muscle cars? He hangs them on the wall — instant blue-collar

Minimalist reliefs. Planters made of sliced and splayed truck tires? There’s one

at the Guggenheim, cast in white resin, where the fountain should be. Is it a

comment on the work of Matthew Barney, a gallery-mate who had his own Guggenheim

fete? Probably. But from above it resembles a plastic toy crown or the

after-splash of milk in that famous stop-action Harold Edgerton photograph.

And borscht belt jokes? They are a signature staple that runs rampant in the

show, appearing on modernist monochromes, on fields of checks and as arbitrary

punch lines for postwar New Yorker or Playboy cartoons. These examples of a

better class of humor are variously whole, fragmented, steeped in white or piled

into colorful, nearly abstract patterns yet still retain their familiarity. The

same jokes occur in different works, alternately writ big or little, sharp or

fading, straight or rippled as if spoken by someone on a bender.

“My father was never home, he was always drinking booze. He saw a sign saying

‘Drink Canada Dry.’ So he went up there.” “I went to see a psychiatrist. He

said, ‘Tell me everything.’ I did, and now he’s doing my act.”

Mr. Prince’s act has been one of continual breakouts and surprises, some better

than others, and of increasing command. Selected and expertly installed by Nancy

Spector, the Guggenheim’s chief curator, with considerable input from Mr.

Prince, the show includes examples from nearly 20 series of works, but it also

skips a lot of weaker efforts, tryouts and rehearsals. It sums up more than

recounts the path of a brilliant artist whose sense of visual style is matched

by an ear for language, as he progresses from hip, hermetic mind games to hip,

inclusive generosity and even tenderness.

Mr. Prince was born in the Panama Canal Zone in 1949 and has shown in New York

since the late 1970s. He is a leading member of the sprawling appropriation

generation of the early ’80s that included artists like Barbara Kruger, Cindy

Sherman and Jeff Koons and that continues to add new recruits, like Wayne Guyton

and Kelly Walker.

In a sense his career has been a process of self-liberation by expanding upon an

esoteric mode that he helped invent. His early work, the essence of orthodox

postmodern appropriation, consists of influential yet hermetic rephotographs of

the ads and fashion spreads in glossy magazines. Cropped, enlarged and grouped

according to subject and pose, these images exposed with almost anthropological

precision advertising’s subliminal codes and stereotypes. For all its elegance,

the early work had a spindly endgame air that seemed to disdain anything as

touch-feely as making an actual art object. But that is just what Mr. Prince

proceeded to do, regularly introducing new subjects, mediums and techniques.

The primness of the early photographs gives way to the Technicolor flamboyance

of the Cowboy series, pirated from the famous Marlboro Country campaign. Then

come the grainy, clustered “gangs,” as he called them, of related magazine

images — big-wheeled trucks, rock bands, surfers’ waves. Surprisingly, Mr.

Prince’s latest camera works reject appropriation altogether. They are dour yet

lyrical images of the hardscrabble area in upstate New York where he lives.

His paintings have become similarly free, or perhaps traditional, as evinced by

his pulp-fiction-cover Nurse series. But the final gallery leaves him working at

new extremes. On the one hand he seems to be painting for all his worth in his

garish new reprises of de Kooning’s “Women,” in which most of the girls are guys

who look a little too much like Jar Jar Binks. On the other are his latest

straight-out ready-mades: the American English series simply and suavely

juxtaposes American and English editions of books like Lenny Bruce’s “How to

Talk Dirty and Influence People” or Bob Dylan’s “Tarantula,” creating a subtle

exegesis of the national character of design.

Early in the show an especially imposing joke painting offers a summation of his

ambition. “I Know a Guy” (2000) has a snowy surface powdered with eminently

touchy-feely plumes of pastel but starkly divided by a horizontal band of large

black Helvetica type, all caps and hand-stenciled. In a crowded rush, the words

inject a twitching dose of stand-up monologue: “I knew a guy who was so rich he

could ski uphill. Another one, I told my mother-in-law my house is your house.

Last week she sold it. Another one ... ”

The clincher here is the urgent aside “another one,” which has echoes in

subsequent joke paintings: “Again.” “One more.” It turns these paintings into

portraits of the artist at work, sweating it out, honing his material and

timing, egging himself on to come up with another one and then another one until

he gets our full attention, cracks us up and, in stand-up parlance, kills.

That, in a nutshell, might be the story of Mr. Prince’s career, one of nonstop

production, of collecting, editing and honing, of sifting and shifting styles

and techniques, and getting better all the time. Among other things, it means

that the Nurse and the de Kooning series, if continued, can only improve.

“Richard Prince: Spiritual America”

continues through Jan. 9

at the Guggenheim

Museum, 1071 Fifth Avenue,

at 89th Street; (212) 423-3500.

Pilfering a Culture Out

of Joint, NYT, 28.9.2007,

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/28/arts/design/28prin.html

A Passage

for the Master of Heavy Metal

July 25, 2007

The New York Times

By CAROL VOGEL

LONDON — Although he is widely viewed as Britain’s greatest living sculptor,

received a knighthood 20 years ago and has been the subject of countless museum

retrospectives, Anthony Caro has yet to have an exhibition in New York’s

Chelsea, the epicenter of today’s contemporary art scene.

“I used to go to New York all the time, but it’s been three years,” Mr. Caro,

83, said one recent morning over tea at a long wooden table in one of the former

pipe and piano factories where he works in North London.

But this fall, he will finally have his Chelsea moment. He recently completed a

series of monumental painted steel sculptures, weighing about two tons each,

titled “Passage.” Five of them will go on view at Mitchell-Innes & Nash in

Chelsea in October, and four will be shown at Annely Juda Fine Art in London in

September.

A return to the abstract steel sculptures that made him famous more than 40

years ago, the latest work is as architectural as it is sculptural. Yet unlike

the vast pieces by Richard Serra that are currently on view at the Museum of

Modern Art, which physically envelop the viewer, Mr. Caro’s latest sculptures

can be experienced only from a slight remove. There is no point of entry.

“When I saw this body of work I felt he had done something dramatic,” said Lucy

Mitchell-Innes, Mr. Caro’s New York dealer. “Although he picked up on old themes

from the ’60s of using grills and grids, this time they don’t just define space

but restrict access to it.”

Those who know Mr. Caro’s work will instantly recognize the “Passage” series as

his, yet the artist considers these sculptures a significant departure.

“I’m not interested in doing old things,” he said. “I’m always trying to push it

and see what happens.”

He said he chose that title for the series because he conceived of the

sculptures as visual passages, even though you cannot physically walk through

them.

One of the biggest changes from his past work is that he used galvanized steel

rather than rusted steel. “I thought I wanted to paint them, so I sent the steel

out to be galvanized in order to get the surface right,” he said. “And when it

came back, I liked the way it looked.” So he kept it as is.

While fragments of sculptural objects are strewn around his studio — remnants of

steel and machine parts that he buys by the weight at scrap yards around Europe

— the works from this new series were nowhere in sight. Some had been sent to

storage, and others were on their way to the dealers. He did have transparencies

of them carefully laid out on a lightbox.

In the Cubist tradition, Mr. Caro has long seized on found objects and used them

as the basis for his sculptures. One of the new works, “Star Passage,” made of

steel galvanized and painted blue, incorporates a big guillotine for slicing

steel that he found in the South of France. For another, “Chalk Line,” he took a

long stone drinking trough, laid it on wood and applied galvanized steel planes

to it in sections to make it seem as though he had dissected the stone.

Resting atop it is a hollow steel pole. “It is almost as if you crossed a Donald

Judd with a Roman sarcophagus,” Ms. Mitchell-Innes said.

Unlike most artists, Mr. Caro generally does not work from drawings or maquettes

when making sculptures. “I prefer to do the real thing,” he said. “You can feel

the weight and reality of moving around steel. Whereas if you do something on a

smaller scale, when it gets bigger it looks different.”

Sometimes, however, such free-style thinking is impossible, as with his current

project for a choir for a church in northern France.

Occupying several studio buildings of his London work space are a series of

dollhouse-like structures that are scaled-down models of the medieval Church of

St.-Jean-Baptiste in Bourbourg, including stained-glass windows and a pair of

round towers.

“It’s a 12th-century building, and at the time of Dunkirk, a plane landed on the

roof and caught fire to the church,” he said, referring to the German invasion

of the region in 1940. “The roof was restored but not the choir. Eight years

ago, they asked me to do the choir.”

Unlike his sculptures, in which issues of scale, materials and design are all up

to him, this project involves fitting a predetermined architectural space. “I’m

leaving nothing to chance,” Mr. Caro said as he peered into a wood model.

He has created two towers for the choir and what he called an immersion tank for

christenings. There will also be nine niches with sculptures in them that tell

the story of the Creation. “Not exactly the Creation from the Bible,” he said.

“More about animals, fish and things we see around us.” Outside the church, he

has designed a tower of Cor-Ten steel, which he also calls a visual passage.

Mr. Caro is accustomed to big projects. After attending Cambridge University

and art school, he began working as Henry Moore’s assistant in 1951. A decade

later he created his own large-scale abstract structures. They were considered

revolutionary at the time because he had abandoned figurative sculpture and gone

totally abstract. And rather than setting his sculptures on a pedestal, he

placed them on the ground, relating them directly to human scale.

By the 1960s and ’70s, he had become as well known as a Damien Hirst or Jeff

Koons is today. But with the wane of formalism in the United States, his

popularity waned, and he is now far better known in Europe.

Some contemporary artists still look to him for inspiration. The Los Angeles

sculptor Charles Ray has made works in homage to him, including a re-creation of

one of his most famous works, “Early One Morning,” a bright red horizontal metal

sculpture of disparate lines and planes.

Jessica Stockholder, a sculptor who directs graduate studies in sculpture at the

Yale University School of Art, says she is an enthusiastic fan. “I’ve always

admired him,” she said. “His work is about how things jump across space to meet

each other, and my work is about that too. In the ’80s I made a tabletop

sculpture piece called ‘Ode to Anthony Caro.’ ”

Just how a Chelsea audience will react to Mr. Caro’s latest work is anyone’s

guess. “Who can say what’s going to be hot or cold from one year to the next?”

Ms. Stockholder asked.

Meanwhile, Mr. Caro seems unconcerned. “When you get older,” he said, “you just

have to go your own way.”

A Passage for the Master of Heavy

Metal,

NYT,

25.7.2007,

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/25/

arts/design/25caro.html

Explore more on these topics

Anglonautes > Vocapedia

painting, street art, tattoes, sculpture

children's

books

e-books / reading on the

Internet

books

/ newspapers / www >

comics, superheroes, superheroines

graphic novels

architecture, towns, cities

describing pictures >

phrases and verb forms

Related > Anglonautes >

Arts

painting, sculpture

Related

Tate

UK

https://www.tate.org.uk/

https://www.tate.org.uk/visit/tate-modern

|