|

Vocapedia >

Economy > Consumers

Andy Singer

NO EXIT

Cagle

30 October 2010

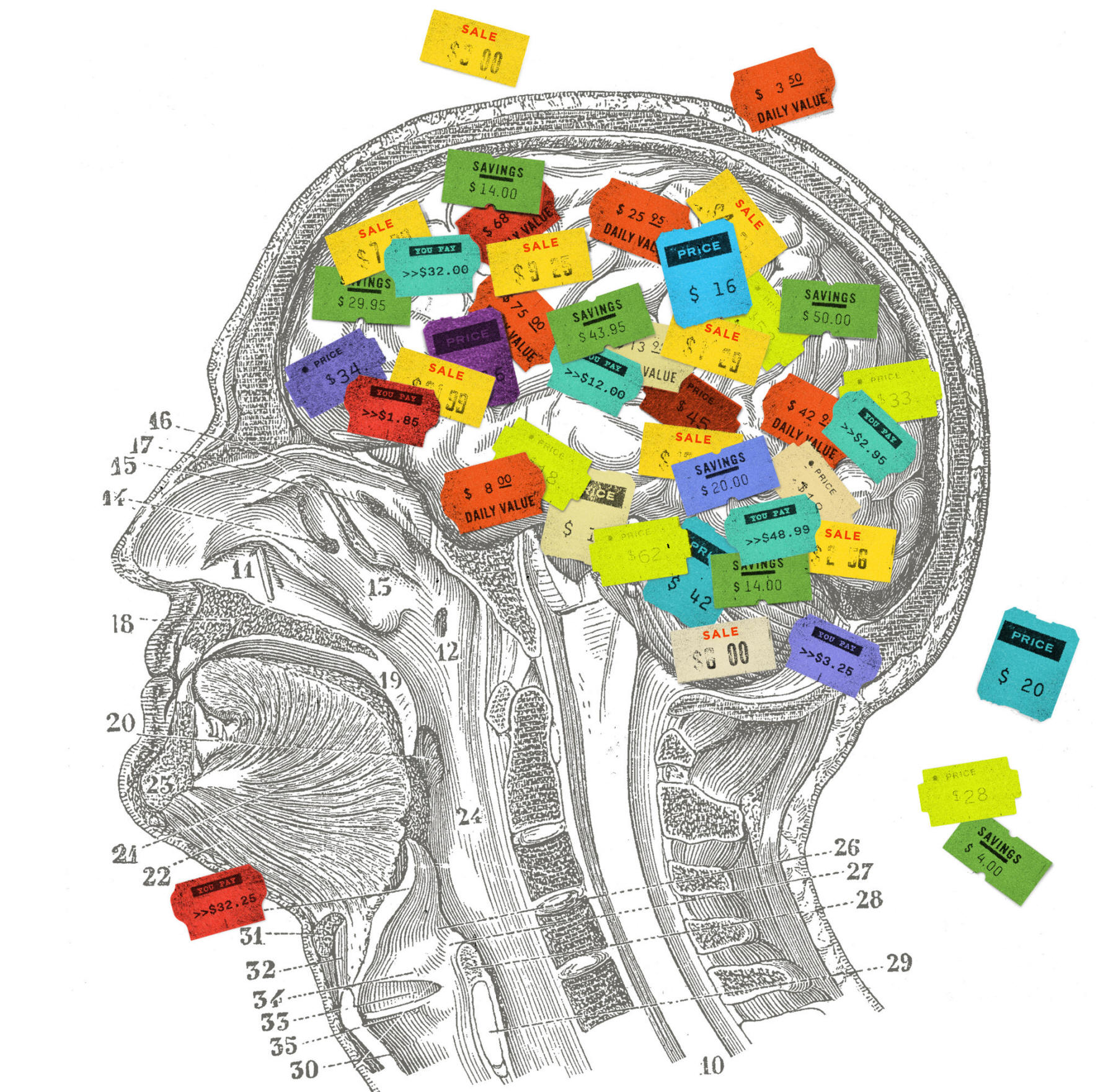

Illustration: Mike McQuade

Sunday Book Review

Tom McCarthy’s ‘Satin Island’

NYT

FEB. 20, 2015

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/22/

books/review/tom-mccarthys-satin-island.html

Andy Singer

cartoon

NO EXIT

Cagle

29 September 2010

Andy Singer

cartoon

No Exit

Cagle

21 November 2009

Illustration: Cara Lichtenstein

Being Poor in a ‘Charge It’ Society

NYT

17.2.2008

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/02/17/

opinion/l17spend.html

The Guardian

p. 14 6 December 2008

http://digital.guardian.co.uk/guardian/2008/12/06/pdfs/gdn_081206_ber_14_21390842.pdf

consume

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/07/25/

style/tiktok-underconsumption-influencers.html

consumer

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2008/jun/27/gdp.growth

consumer

USA

http://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2016/10/25/

499185907/the-at-t-time-warner-merger-what-are-the-pros-and-cons-for-consumers

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/15/your-money/credit-and-debit-cards/

consumers-not-powerless-in-the-face-of-card-fraud.html

https://www.reuters.com/article/ousivMolt/idUSTRE4AG3I3

20081117/

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/31/opinion/31krugman.html

consumer watchdog

USA

https://www.npr.org/2018/02/12/

584980698/trump-administration-to-defang-consumer-protection-watchdog

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/11/

opinion/quietly-killing-a-consumer-watchdog.html

Dodd-Frank Financial

Reform >

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau CFPB

USA

The Consumer

Financial Protection Bureau

was created after the

financial crisis

to protect Americans from being ripped off

by financial firms.

https://www.npr.org/2018/02/12/

584980698/trump-administration-to-defang-consumer-protection-watchdog

https://www.npr.org/2018/02/18/

586493309/trump-administrations-latest-strike-on-cfpb-budget-cuts

https://www.npr.org/2018/02/12/

584980698/trump-administration-to-defang-consumer-protection-watchdog

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/04/

opinion/paul-krugman-dodd-frank-financial-reform-is-working.html

consumer behavior

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/topic/subject/

consumer-behavior

economic behaviour

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2015/mar/17/

germanys-financial-prudence-preferred-toilet-paper

retail > bad manners

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/26/fashion/shopping-etiquette-retail-advice.html

consumer optimism

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/24/

business/rising-consumer-optimism-fuels-an-annual-spree.html

USA >

consumer lending

https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSTRE4AO4XV20081125/

consumer society

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/12/business/economy/12leonhardt.html

consumer culture

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/12/business/economy/12leonhardt.html

new way of consuming

rental / sharing economy > rent

USA 2014

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/30/

upshot/is-owning-overrated-the-rental-economy-rises.html

consumer

sentiment

consumer protection

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/topic/subject/consumer-protection

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/24/opinion/24wed1.html

consumer product safety

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/topic/subject/consumer-product-safety

consumer electronics

CES > the world's largest consumer

technology tradeshow USA

https://www.ces.tech/

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/ces-2011

consumerism

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2024/dec/04/

revisited-too-much-stuff-can-we-solve-our-addiction-to-consumerism-podcast

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/dec/02/

are-young-people-poised-to-slam-the-brake-on-endless-economic-growth

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2011/aug/22/

uk-riots-economy-consumerism-values

consumerism

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/12/

opinion/sunday/unequal-yet-happy.html

consumerist

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/

consumerism-sustainability-short-termism - 2 December 2010

consuming

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/12/

business/economy/12leonhardt.html

overconsumption

USA

https://www.npr.org/2024/02/25/

1198910494/deinfluencers-ring-the-alarm-on-overconsumption

underconsumption

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/article/2024/aug/04/

reuse-that-teabag-ignore-that-special-offer-

its-time-to-join-the-underconsumer-revolution

underconsumption

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/07/25/

style/tiktok-underconsumption-influencers.html

underconsumer

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/article/2024/aug/04/

reuse-that-teabag-ignore-that-special-offer-

its-time-to-join-the-underconsumer-revolution

consumer confidence

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/money/2010/dec/21/

consumer-confidence-12-month-low

economic confidence

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2011/mar/25/voters-cuts-coalition-poll

consumer confidence

USA

https://www.gocomics.com/stevebreen/2025/02/27

http://www.npr.org/blogs/thetwo-way/2013/06/25/

195515025/5-year-high-in-consumer-confidence-bodes-well-for-economy

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/01/business/economy/01econ.html

https://www.reuters.com/article/ousiv/idUSN12222686

20080313/

https://www.reuters.com/article/domesticNews/idUSN12170655

20080312/

Consumer Confidence Index

shopper

budget shoppers USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/22/business/22dollar.html

shopping

cartoons > Cagle > Holiday shopping

USA 2010

http://www.cagle.com/news/Shopping10/

main.asp

browse USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/02/business/economy/

gloomy-numbers-for-holiday-shoppings-big-weekend.html

brand UK

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/sep/22/

coolbrands-apple-twitter-stella-mccartney-chanel-uk

http://www.guardian.co.uk/money/shortcuts/2012/may/23/rise-own-brand

label UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/money/shortcuts/2012/may/23/rise-own-brand

spend

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2008/nov/23/economy-taxandspending

spend

USA

https://www.npr.org/2020/09/21/

915289340/spend-savvier-save-smarter-5-tips-to-stop-stress-spending

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/25/

opinion/why-we-spend-why-they-save.html

consumer spending

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/business/

consumerspending

spending

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2011/aug/22/

uk-riots-economy-consumerism-values

cut back on

spending

miser

mean UK

https://www.theguardian.com/money/blog/2011/jan/18/

mean-penurious-uk-skinflints

meanies

stingy UK

https://www.theguardian.com/money/blog/2011/jan/18/

mean-penurious-uk-skinflints

skinflint UK

https://www.theguardian.com/money/blog/2011/jan/18/

mean-penurious-uk-skinflints

consumer crunch

slip

consumer prices

expensive

unexpensive

cheap

it doesn't

come cheap

price war USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/24/business/24shop.html

Consumer Price Index CPI

USA

https://www.bls.gov/cpi/

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/16/business/16cnd-econ.html

VAT

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2010/jun/27/liberal-democrat-mps-vat-poor

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2008/nov/23/economy-taxandspending

VAT rise

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/cartoon/2010/jun/27/

martin-rowson-coalition-budget-cuts

R.J. Matson

cartoon

The New York Observer and Roll Call

NY

Cagle

14

November 2008

Record fuel prices blow budgets

USA March 2008

http://www.usatoday.com/money/industries/energy/2008-03-10-

oil-gas-prices_N.htm

- broken ink

personal spending

purchasing power

thrift

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2008/dec/14/

credit-crunch-high-street

thriftiness

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/14/

business/14homeec.html

on a shoestring

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/28/garden/28britain.html

home economics

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/14/business/14homeec.html

budget

spend

http://www.guardian.co.uk/money/2007/dec/29/retail.highstreetretailers

buy

https://www.reuters.com/article/ousivMolt/idUSTRE4AG3I3

20081117

purchase

purchase

bid

outbid

pay

https://www.reuters.com/article/ousivMolt/idUSTRE4AG3I3

20081117

payment USA

https://www.npr.org/2022/07/02/

1109105779/monthly-car-payments-record-700

order

order

delivery

refund

refund

value for money

afford USA

http://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/03/11/

519416036/im-pregnant-what-would-happen-if-i-couldnt-afford-health-care

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/05/

sunday-review/the-families-that-cant-afford-summer.html

affordable

affordable housing UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2010/nov/26/

guardian-christmas-2010-charity-appeal

unaffordable UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2010/oct/31/

london-housing-crisis-benefit-cuts

price USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/23/

business/23haggle.html

save

USA

https://www.npr.org/2020/09/21/

915289340/spend-savvier-save-smarter-5-tips-to-stop-stress-spending

save up to half price

50% off

huge savings

rip-off

be skint

(colloquial)

hard-up

increase in consumer prices

pay bank fees

bills

USA

https://www.npr.org/2020/12/16/

941292021/paycheck-to-paycheck-nation-how-life-in-america-adds-up

struggle

struggle UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/money/2011/apr/12/

savers-struggling-despite-inflation-drop

struggle to pay

one's bills

struggle with bills

USA

https://www.npr.org/2020/12/16/

941292021/paycheck-to-paycheck-nation-how-life-in-america-adds-up

struggle with very little capital

cost of living

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/dec/02/

are-young-people-poised-to-slam-the-brake-on-endless-economic-growth

https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2022/jan/19/

the-cost-of-living-crisis-in-the-uk-podcast

https://www.theguardian.com/money/2005/apr/26/

debt.uknews

living standards

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/07/opinion/when-wealth-disappears.html

live beyond

one's means USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/07/opinion/when-wealth-disappears.html

Ed Stein

political cartoon

The Rocky Mountain News

Colorado

Cagle

25 November 2008

cardholder

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/10/

your-money/credit-and-debit-cards/10rates.html

buy now,

pay later

https://www.reuters.com/article/ousivMolt/idUSTRE4AG3I3

20081117

store

card

payment card for kids

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/money/2006/jan/26/

creditcards.business

cash UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/green-living-blog/2009/oct/28/

live-without-money

be out of cash

cash

machine / cash dispenser / ATM USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/31/nyregion/31nyc.html

ATM charges

USA

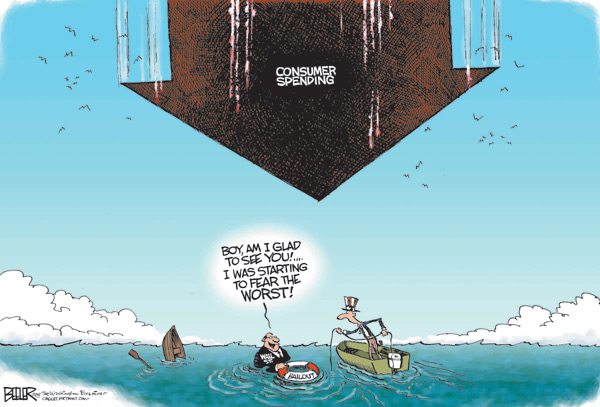

Nate Beeler

political cartoon

The Washington Examiner

Washington, D.C.

Cagle

14.11.2008

R: Uncle Sam

thrift economy

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/25/us/25garage.html

car boot sale

UK

http://www.carbootjunction.com/

http://www.guardian.co.uk/travel/interactive/2008/jun/10/vauxhall.art.car.boot

yard sales / garage sales

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/23/us/23bethsidebar.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/25/us/25garage.html

barter

bartering

Kirk Anderson

political cartoon

Cagle

8 December 2004

http://cagle.slate.msn.com/politicalcartoons/PCcartoons/anderson.asp

http://www.kirktoons.com/cartoons.html

own

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/article/2024/aug/04/

reuse-that-teabag-ignore-that-special-offer-

its-time-to-join-the-underconsumer-revolution

owner

owning USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/30/

upshot/is-owning-overrated-the-rental-economy-rises.html

ownership

President George W. Bush's

vision of an "ownership society"

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/01/16/politics/16own.html

middle and lower-income classes

Social Security system

Social Security trust

solvency

private Social Security accounts

waste UK

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/

waste

https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2024/dec/04/

revisited-too-much-stuff-can-we-solve-our-addiction-to-consumerism-podcast

food waste USA

http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/11/01/

from-farm-to-fridge-to-garbage-can/

waste

USA

https://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/11/01/

from-farm-to-fridge-to-garbage-can/

Andy Singer

cartoon

No Exit

Cagle

11 August 2009

Black Friday USA

the day after Thanksgiving /

the first official day of the U.S. holiday shopping

season

http://intransit.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/11/25/travel-deals-black-friday-hotel-sales/

https://www.reuters.com/article/newsOne/idUSN23617641

20071123

Cagle cartoons > Black Friday / Holiday

Shopping USA

http://www.cagle.com/news/ChristmasShopping09/main.asp

Cyber Monday

- the first Monday after

Thanksgiving USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/26/technology/26ecom.html

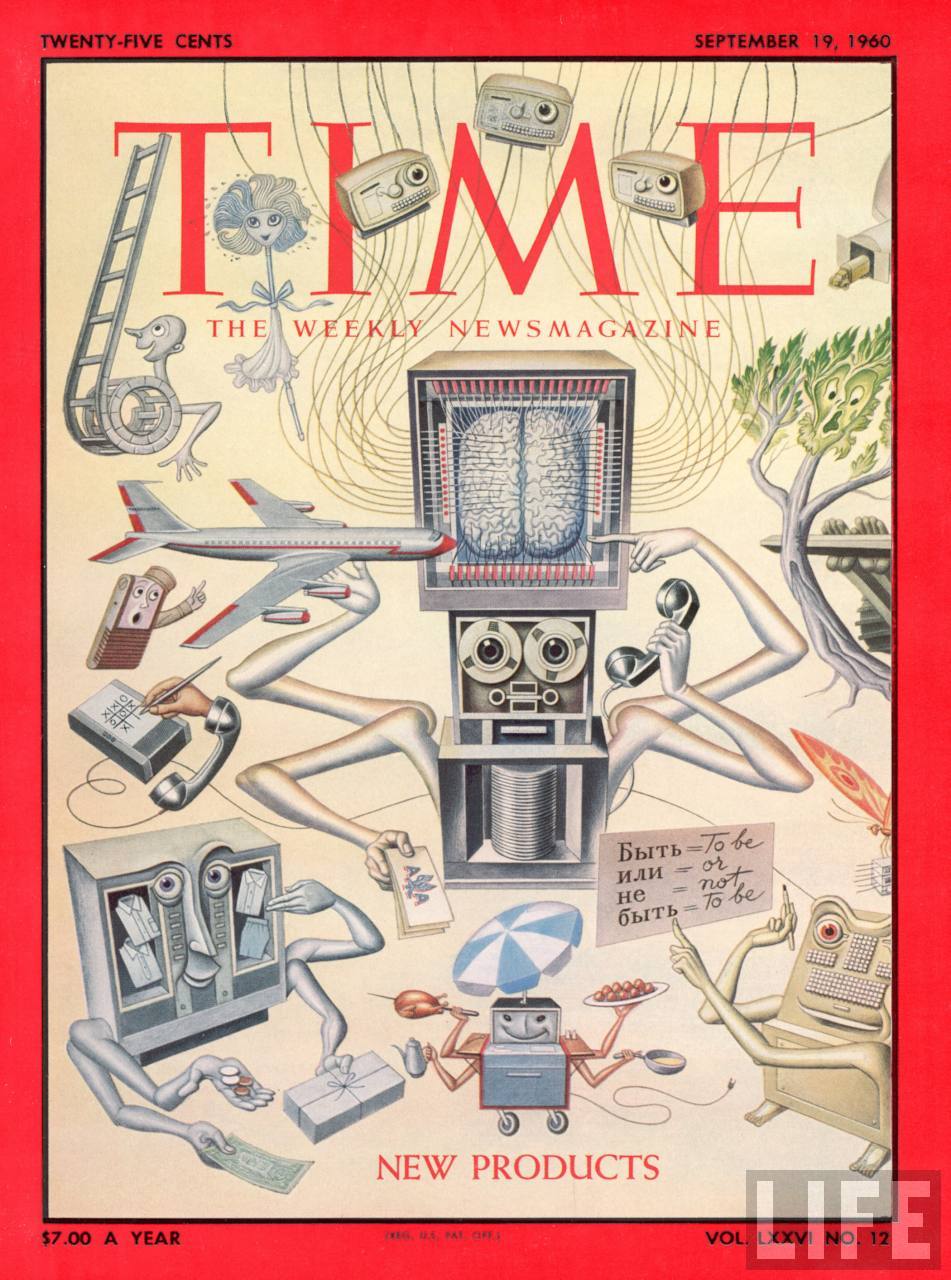

Time Covers - The 60S

TIME cover 09-19-1960 ill. depicting New Products.

Date taken: September 19, 1960

Photograph: Boris Artzybasheff

Life Images

http://images.google.com/hosted/life/l?imgurl=f9a24682c47d9ef7 - broken link

Corpus of news articles

Economy > Consumers

Why We

Spend, Why They Save

November

24, 2011

The New York Times

By SHELDON GARON

Princeton,

N.J.

CHRISTMAS

is nearly upon us. Americans, once again, are told that it’s our civic duty to

shop. The economy demands increased consumer spending. And it’s true. The

problem is that millions of lower- and middle-income households have lost their

capacity to spend. They lack savings and are mired in debt. Although it would be

helpful if affluent households spent more, we shouldn’t be calling upon a

struggling majority to do so. In the long run, the health of the economy depends

on the financial stability of our households.

What might we learn from societies that promote a more balanced approach to

saving and spending? Few Americans appreciate that the prosperous economies of

western and northern Europe are among the world’s greatest savers. Over the past

three decades, Germany, France, Austria and Belgium have maintained household

saving rates between 10 and 13 percent, and rates in Sweden recently soared to

13 percent. By contrast, saving rates in the United States dropped to nearly

zero by 2005; they rose above 5 percent after the 2008 crisis but have recently

fallen below 4 percent.

Unlike the United States, the thrifty societies of Europe have long histories of

encouraging the broad populace to save. During the 19th century, European

reformers and governments became preoccupied with creating prudent citizens.

Civic groups founded hundreds of savings banks that enabled the masses to save

by accepting small deposits. Central governments established accessible postal

savings banks, whereby small savers could bank at any post office. To inculcate

thrifty habits in the young, governments also instituted school savings banks.

During the two world wars, citizens everywhere were bombarded with messages to

save. Savings campaigns continued long after 1945 in Europe and Japan to finance

reconstruction.

All this fostered cultures of saving that endure today in many advanced

economies. The French government attracts millions of lower-income and young

savers with its Livret A account available at savings banks, postal savings

banks and all other banks. This small savers’ account is tax free, requires only

a tiny minimum balance, and commonly pays above-market interest rates. In German

cities, one cannot turn the corner without coming upon one of the immensely

popular savings banks, called Sparkassen. Legally charged with encouraging the

“savings mentality,” these banks offer no-fee accounts for the young and sponsor

financial education in the schools.

Supported by public opinion, policy makers in European countries have also

restrained the expansion of consumer and housing credit, lest citizens become

“overindebted.” Home equity loans are rare in Germany, and Belgians, Italians

and Germans are rarely offered an American-style credit card that allows the

user to carry an unpaid balance.

How did America arrive at its widely divergent approach to saving and

consumption? Seldom over the past two centuries has the federal government

promoted saving; it left matters to the states or the market. In the 19th

century, savings banks and building and loan associations did thrive in the

Northeastern and Midwestern states; where they existed, working people saved at

high rates. However, the vast majority of Americans in the Southern and Western

states lacked access to any savings institution as late as 1910. Most Americans

became regular savers only after the federal government decisively intervened to

institute the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation in 1934 and mass-market

United States savings bonds in World War II.

The United States emerged from the war with unparalleled prosperity and hardly

needed further savings campaigns. Instead politicians, businessmen and labor

leaders all promoted consumption as the new driver of economic growth. Rather

than democratize saving, the American system rapidly democratized credit. An

array of federal housing and tax policies enabled Americans to borrow to buy

homes and products as no other people could.

But from the 1980s, financial deregulation and new tax legislation spurred the

growth of credit cards, home equity loans, subprime mortgages and predatory

lending. Soaring home prices emboldened the financial industry to make housing

and consumer loans that many Americans could no longer repay. Still, Americans

wondered, why save when it is so easy to borrow? Only after housing prices

collapsed in 2008 did they discover that wealth on paper is not the same as

money in the bank.

As we seek to restore a balance between saving and consumption, what aspects of

other nations’ experiences might we adapt to our circumstances? The new Consumer

Financial Protection Bureau, while politically besieged, possesses broad powers

to curb predatory lending. The bureau might also promote the creation of

financial education programs in every school. Congress should consider ending

costly tax incentives for wealthier savers and homebuyers while creating new

incentives to encourage low- and middle-income people to save. Finally, federal

intervention is needed to stop the banks from fleecing and driving away their

poorest customers. If the banks cannot be encouraged to offer low-fee accounts

for young and lower-income customers, the government might consider creating

postal savings accounts for small savers.

To improve the balance sheets of America’s households, we must approach saving

in a more forthright manner — not an easy thing to do when again and again we

hear that individual prudence acts to impair the economy.

Sheldon Garon,

a professor of history

and East Asian studies at Princeton,

is the author

of “Beyond Our Means:

Why America Spends While the World Saves.”

Why We Spend, Why They Save,

NYT,

24.11.2011,

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/25/

opinion/why-we-spend-why-they-save.html

From Farm to Fridge to Garbage Can

November 1, 2010

5:27 pm

The New York Times

By TARA PARKER-POPE

How much food does your family waste?

A lot, if you are typical. By most estimates, a quarter to half of all food

produced in the United States goes uneaten — left in fields, spoiled in

transport, thrown out at the grocery store, scraped into the garbage or

forgotten until it spoils.

A study in Tompkins County, N.Y., showed that 40 percent of food waste occurred

in the home. Another study, by the Cornell University Food and Brand Lab, found

that 93 percent of respondents acknowledged buying foods they never used.

And worries about food safety prompt many of us to throw away perfectly good

food. In a study at Oregon State University, consumers were shown three samples

of iceberg lettuce, two of them with varying degrees of light brown on the edges

and at the base. Although all three were edible, and the brown edges easily cut

away, 40 percent of respondents said they would serve only the pristine lettuce.

In his new book “American Wasteland: How America Throws Away Nearly Half of Its

Food” (Da Capo Press), Jonathan Bloom makes the case that curbing food waste

isn’t just about cleaning your plate.

“The bad news is that we’re extremely wasteful,” Mr. Bloom said in an interview.

“The positive side of it is that we have a real role to play here, and we can

effect change. If we all reduce food waste in our homes, we’ll have a

significant impact.”

Why should we care about food waste? For starters, it’s expensive. Citing

various studies, including one at the University of Arizona called the Garbage

Project that tracked home food waste for three decades, Mr. Bloom estimates that

as much as 25 percent of the food we bring into our homes is wasted. So a family

of four that spends $175 a week on groceries squanders more than $40 worth of

food each week and $2,275 a year.

And from a health standpoint, allowing fresh fruits, vegetables and meats to

spoil in our refrigerators increases the likelihood that we will turn to less

healthful processed foods or restaurant meals. Wasted food also takes an

environmental toll. Food scraps make up about 19 percent of the waste dumped in

landfills, where it ends up rotting and producing methane, a greenhouse gas.

A major culprit, Mr. Bloom says, is refrigerator clutter. Fresh foods and

leftovers languish on crowded shelves and eventually go bad. Mr. Bloom tells the

story of discovering basil, mint and a red onion hiding in the fridge of a

friend who had just bought all three, forgetting he already had them.

“It gets frustrating when you forget about something and discover it two weeks

later,” Mr. Bloom said. “So many people these days have these massive

refrigerators, and there is this sense that we need to keep them well stocked.

But there’s no way you can eat all that food before it goes bad.”

Then there are chilling and food-storage problems. The ideal refrigerator

temperature is 37 degrees Fahrenheit, and the freezer should be zero degrees,

says Mark Connelly, deputy technical director for Consumer Reports, which

recently conducted extensive testing on a variety of refrigerators. The magazine

found that most but not all newer models had good temperature control, although

models with digital temperature settings typically were the best.

Vegetables keep best in crisper drawers with separate humidity controls.

If food seems to be spoiling quickly in your refrigerator, check to make sure

you’re following the manufacturer’s care instructions. Look behind the fridge to

see if coils have become caked with dust, dirt or pet hair, which can interfere

with performance.

“One of the pieces of advice we give is to go to a hardware store and buy a

relatively inexpensive thermometer,” Mr. Connelly said. “Put it in the

refrigerator to check the temperature to make sure it’s cold enough.”

There’s an even easier way: check the ice cream. If it feels soft, that means

the temperature is at least 8 degrees Fahrenheit and you need to lower the

setting. And if you’re investing in a new model, don’t just think about space

and style, but focus on the refrigerator that has the best sight lines, so you

can see what you’re storing. Bottom-freezer units put fresh foods at eye level,

lowering the chance that they will be forgotten and left to spoil.

Mr. Bloom also suggests “making friends with your freezer,” using it to store

fresh foods that would otherwise spoil before you have time to eat them.

Or invest in special produce containers with top vents and bottom strainers to

keep food fresh. Buy whole heads of lettuce, which stay fresher longer, or add a

paper towel to the bottom of bagged lettuce and vegetables to absorb liquids.

Finally, plan out meals and create detailed shopping lists so you don’t buy more

food than you can eat.

Don’t be afraid of brown spots or mushy parts that can easily be cut away.

“Consumers want perfect foods,” said Shirley Van Garde, the now-retired

co-author of the Oregon State study. “They have real difficulty trying to tell

the difference in quality changes and safety spoilage. With lettuce, take off a

couple of leaves, you can do some cutting and the rest of it is still usable.”

And if you do decide to throw away food, give it a second look, Mr. Bloom

advises. “The common attitude is ‘when in doubt, throw it out,’” he said. “But I

try to give the food the benefit of the doubt.”

From Farm to Fridge to

Garbage Can, NYT, 1.11.2010,

http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/11/01/from-farm-to-fridge-to-garbage-can/

A Reluctance to Spend

May Be a Legacy of the Recession

August 29, 2009

The New York Times

By PETER S. GOODMAN

AUSTIN, Tex. — Even as evidence mounts that the Great

Recession has finally released its chokehold on the American economy, experts

worry that the recovery may be weak, stymied by consumers’ reluctance to spend.

Given that consumer spending has in recent years accounted for 70 percent of the

nation’s economic activity, a marginal shrinking could significantly depress

demand for goods and services, discouraging businesses from hiring more workers.

Millions of Americans spent years tapping credit cards, stock portfolios and

once-rising home values to spend in excess of their incomes and now lack the

wherewithal to carry on. Those who still have the means feel pressure to

conserve, fearful about layoffs, the stock market and real estate prices.

“We’re at an inflection point with respect to the American consumer,” said Mark

Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Economy .com, who correctly forecast a dip in

spending heading into the recession, and who provided data supporting sustained

weakness.

“Lower-income households can’t borrow, and higher-income households no longer

feel wealthy,” Mr. Zandi added. “There’s still a lot of debt out there. It

throws a pall over the potential for a strong recovery. The economy is going to

struggle.”

In recent weeks, spending has risen slightly because of exuberant car buying,

fueled by the cash-for-clunkers program. On Friday, the Commerce Department said

spending rose 0.2 percent in July from the previous month. But most economists

see this activity as short-lived, pointing out that incomes did not rise. Some

suggest the recession has endured so long and spread pain so broadly that it has

seeped into the culture, downgrading expectations, clouding assumptions about

the future and eroding the impulse to buy.

The Great Depression imbued American life with an enduring spirit of thrift. The

current recession has perhaps proven wrenching enough to alter consumer tastes,

putting value in vogue.

“It’s simply less fun pulling up to the stoplight in a Hummer than it used to

be,” said Robert Barbera, chief economist at the research and trading firm ITG.

“It’s a change in norms.”

Here in Austin, a laid-back city on the banks of the Colorado River, change is

palpable.

A decade ago, Heather Nelson gained a lucrative job in telecommunications and

celebrated by buying a new Ford sport utility vehicle with leather seats and an

expensive stereo system. Today, Ms. Nelson, 38, again has designs on a new

vehicle, but this time she plans to buy a Toyota Prius, the fuel-efficient

hybrid.

In December, Ms. Nelson was laid off from her six-figure job as a patent

attorney at a local software firm. Self-assured, she exudes confidence she will

land another high-paying position.

But even if her spending power is restored, Ms. Nelson says her inclination to

buy has been permanently diminished. Through nine months of joblessness, she has

learned to forgo the impulse buys that used to provide momentary pleasure — $4

lattes at Starbucks, lip gloss, mints. She has found she can survive without the

pedicures and chocolate martinis that once filled regular evenings at the spa.

Before punishing heat and drought turned much of central Texas brown, she

subsisted primarily on vegetables harvested from her plot at a community garden,

where only one oasis of flowers remains.

Once intent on buying a home, Ms. Nelson now feels security in remaining a

renter, steering clear of the shark-infested waters of the mortgage industry.

“I’m having to shift my dreams to accommodate the new realities,” she said.

“Now, I have more of a bunker mentality. If you get hit hard enough, it lasts.

This impact is going to last.”

For years, Americans have tapped stock portfolios and borrowed against homes to

fill wardrobes with clothes, garages with cars and living rooms with furniture

and electronics. But stock markets have proven volatile. Home values are sharply

lower. Banks remain reluctant to lend in the aftermath of a global financial

crisis.

Households must increasingly depend upon paychecks to finance spending, a

reality that seems likely to curb consumption: Unemployment stands at 9.4

percent and is expected to climb higher. Working hours have been slashed even

for those with jobs.

Economists subscribe to a so-called wealth effect: as households amass wealth,

they tend to expand their spending over the following year, typically by 3 to 5

percent of the increase.

Between 2003 and 2007 — prime years of the housing boom — the net worth of an

American household expanded to about $540,000, from about $400,000, according to

an analysis of federal data by Moody’s Economy.com.

Now, the wealth effect is working in reverse: by the first three months of this

year, household net worth had dropped to $421,000.

“Not only have people lost money, but they don’t expect as much appreciation in

the money they have, and that should affect consumption,” said Andrew Tilton, an

economist at Goldman Sachs. “This is a cultural shift going on. People will save

more.”

As recently as the middle of 2007, Americans saved less than 2 percent of their

income, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. In recent months, the rate

has exceeded 4 percent.

Austin has fared better than most cities during the recession. Increased

government payrolls enabled by the state’s energy wealth have largely

compensated for layoffs in construction and technology. Local unemployment

reached 7.1 percent in June — well below the national average. Housing prices

have mostly held. Yet even people with high incomes appear reluctant to spend.

“The only time you do a lot of business is when you throw a sale,” said Pat

Bennett, a salesman at a Macy’s in north Austin. “You see very little impulse

buying. They come in saying, ‘I need a pair of underwear,’ and they get it and

leave. You don’t really see them saying, ‘Oh, I love the way that shirt looks,

and I’m just going to get it.’ ”

Mr. Bennett attributes frugality to a general uneasiness about the future.

“Our parents had the Depression,” Mr. Bennett said. “This is like a mini-shock

for the baby boomers after the go-go years.”

At a mall devoted to home furnishings, many storefronts were vacant, and

survivors were draped in the banners of desperation: “Inventory Clearance,” “50%

Off,” “It’s All On Sale.”

But at the Natural Gardener — a lush assemblage of demonstration plots that

sells seeds, plants and tools for organic gardening — business has never been

better.

Sales of vegetable plants swelled fivefold in March over past years. The company

added a public address system and bleachers to accommodate hordes showing up for

vegetable-growing classes.

Part of the embrace of gardening stems from concerns about the environment and

food safety, says the company’s president, John Dromgoole. Momentum also

reflects desire to save on food costs.

“People are very interested in shoring up against losing their jobs,” he said.

A Reluctance to Spend

May Be a Legacy of the Recession,

NYT, 29.8.2009,

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/29/

business/economy/29consumer.html

Editorial

Real Consumer Protection

June 24, 2009

The New York Times

The federal consumer protection system failed the country,

disastrously, in the years leading up to the mortgage crisis. One big cause was

the sharing of responsibility for compliance with laws and regulations among

several agencies that communicate poorly with each other and tend to put the

bankers’ interests first and consumer protection second — if they pay attention

to it all.

The Obama administration was right on the mark last week when it recognized this

problem and proposed a solution: consolidating the far-flung responsibilities

into a strong, new agency that focuses directly on consumer protection. The

plan, modeled on a bill already introduced in the Senate by Richard Durbin,

Democrat of Illinois, deserves broad support in Congress.

Before the current crisis, the lure of big money from Wall Street, which could

not get enough of mortgage-backed securities, spread corruption right through

the mortgage process. Banks and mortgage companies fed kickbacks to brokers, who

often steered borrowers into high-risk, high-cost loans. Appraisers did their

part by inflating property values so that people could borrow beyond their

means.

Deceptive practices became the order of the day. Borrowers who thought they were

getting traditional fixed-rate mortgages sometimes learned at the last minute

that they had been given loans with escalating interest rates, exploding

payments or complicated structures that they clearly did not understand.

Federal regulators were slow to recognize the rising threat to the economy. They

were also vulnerable to “regulatory arbitrage” by the banks, which currently get

to choose their own regulators. If one regulator seems too scrupulous, a bank

can shift to another and then another, in search of the weakest possible

oversight.

Federal regulators may even have accelerated the mortgage crisis by invalidating

state laws that would have protected people from misleading and predatory

lending practices. By pre-empting those tougher state laws, the regulators

helped create an atmosphere in which risky lending practices became the norm.

The new agency envisioned by the Obama administration would put an end to this

slippery practice. It would have authority over all banks, credit card

companies, other credit-granting businesses and independent, nonbank mortgage

companies, which are currently not covered by federal bank regulation.

One of the agency’s principal responsibilities would be to ensure that mortgage

documents are clear and easy to understand. Federal rules would serve as a

floor, not a ceiling, so that the states could pass even more stringent laws

without fear of federal pre-emption. The administration also envisions a

data-driven agency that would react swiftly to events like the ones that should

have foreshadowed the subprime crisis.

In general, the new agency would require little in the way of new institutional

infrastructure. As the administration notes in its proposal, three of the four

federal banking agencies have mostly or entirely separated the consumer

protection function from the rest of the agency. It would be a relatively simple

matter to consolidate those divisions in a new, free-standing agency.

Congress should resist its typical urge to water down this plan for the special

interests that write campaign checks but helped precipitate this crisis.

Lawmakers need to bear in mind that consumer protection laws don’t just shield

individuals. They also protect the economy. That’s a good argument for building

a strong, effective consumer protection agency.

Real Consumer

Protection, NYT, 24.6.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/24/opinion/24wed1.html

Economy Shrank In Third Quarter

as Consumers Retreat

October 30, 2008

Filed at 9:02 a.m. ET

The New York Times

By REUTERS

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - The U.S. economy shrank at a 0.3

percent annual rate in the third quarter, its sharpest contraction in seven

years as consumers cut spending and businesses reduced investment in the face of

rising fears that recession was setting in.

The Commerce Department said the third-quarter contraction in gross domestic

product was the steepest since the corresponding quarter in 2001 though it was

slightly less than the 0.5 percent rate of reduction that Wall Street economists

surveyed by Reuters had forecast.

The third-quarter contraction was a striking turnaround from the second

quarter's relatively brisk 2.8 percent rate of growth. It occurred when

financial market turmoil that has heightened concerns about a potentially

lengthy U.S. recession.

Consumer spending, which fuels two-thirds of U.S. economic growth, fell at a 3.1

percent rate in the third quarter - the first cut in quarterly spending since

the closing quarter of 1991 and the biggest since the second quarter of 1980.

Spending on nondurable goods - items like food and paper products - dropped at

the sharpest rate since late 1950.

Continuing job losses coupled with declining gains from stocks and other

investments have put consumers under severe stress. The GDP report showed that

disposable personal income dropped at an 8.7 percent rate in the third quarter -

the steepest since quarterly records on this component were started in 1947 --

after rising 11.9 percent in the second quarter when most of economic stimulus

payments still were flowing.

Consumers cut spending on durable goods like cars and furniture at a 14.1

percent annual rate in the third quarter, the biggest cut in this category of

spending since the beginning of 1987. Car dealers have said that sales have

virtually stalled, in part because tight credit makes it hard for even

creditworthy buyers to get loans.

Businesses also were clearly wary about the future, cutting investments at a 1

percent rate after boosting them 2.5 percent in the second quarter. It was the

first reduction in business investment since the end of 2006. Inventories of

unsold goods backed up at a $38.5-billion rate in the third quarter after rising

$50.6 billion in the second quarter.

Prices were still rising relatively strongly in the third quarter, with the

personal consumption expenditures index up at a 5.4 percent annual rate, the

sharpest since early 1990. Even excluding volatile food and energy items, core

prices grew at a 2.9 percent rate, up from the second quarter's 2.2 percent

rise.

However, many commodity prices in October have begun to ease and the Federal

Reserve indicated on Wednesday when it slashed interest rates again that its

concern for the future was focused more heavily on weak growth than on

inflation.

(Reporting by Glenn Somerville,

editing by Neil Stempleman)

Economy Shrank In

Third Quarter as Consumers Retreat,

NYT, 30.10.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/reuters/business/business-us-usa-economy.html

Op-Ed Contributor

Dying of Consumption

November 28, 2008

The New York Times

By STEPHEN S. ROACH

Hong Kong

IT’S game over for the American consumer. Inflation-adjusted personal

consumption expenditures are on track for rare back-to-back quarterly declines

in the second half of 2008 at a 3.5 percent average annual rate. There are only

four other instances since 1950 when real consumer demand has fallen for two

quarters in a row. This is the first occasion when declines in both quarters

will have exceeded 3 percent. The current consumption plunge is without

precedent in the modern era.

The good news is that lines should be short for today’s “first shopping day” of

the holiday season. The bad news is more daunting: rising unemployment,

weakening incomes, falling home values, a declining stock market, record

household debt and a horrific credit crunch. But there is a deeper, potentially

positive, meaning to all this: Consumers are now abandoning the asset-dependent

spending and saving strategies they embraced during the bubbles of the past

dozen years and moving back to more prudent income-based lifestyles.

This is a painful but necessary adjustment. Since the mid-1990s, vigorous growth

in American consumption has consistently outstripped subpar gains in household

income. This led to a steady decline in personal saving. As a share of

disposable income, the personal saving rate fell from 5.7 percent in early 1995

to nearly zero from 2005 to 2007.

In the days of frothy asset markets, American consumers had no compunction about

squandering their savings and spending beyond their incomes. Appreciation of

assets — equity portfolios and, especially, homes — was widely thought to be

more than sufficient to make up the difference. But with most asset bubbles

bursting, America’s 77 million baby boomers are suddenly facing a savings-short

retirement.

Worse, millions of homeowners used their residences as collateral to take out

home equity loans. According to Federal Reserve calculations, net equity

extractions from United States homes rose from about 3 percent of disposable

personal income in 2000 to nearly 9 percent in 2006. This newfound source of

purchasing power was a key prop to the American consumption binge.

As a result, household debt hit a record 133 percent of disposable personal

income by the end of 2007 — an enormous leap from average debt loads of 90

percent just a decade earlier.

In an era of open-ended house price appreciation and extremely cheap credit, few

doubted the wisdom of borrowing against one’s home. But in today’s climate of

falling home prices, frozen credit markets, mounting layoffs and weakening

incomes, that approach has backfired. It should hardly be surprising that

consumption has faltered so sharply.

A decade of excess consumption pushed consumer spending in the United States up

to 72 percent of gross domestic product in 2007, a record for any large economy

in the modern history of the world. With such a huge portion of the economy now

shrinking, a deep and protracted recession can hardly be ruled out. Consumption

growth, which averaged close to 4 percent annually over the past 14 years, could

slow into the 1 percent to 2 percent range for the next three to five years.

The United States needs a very different set of policies to cope with its

post-bubble economy. It would be a serious mistake to enact tax cuts aimed at

increasing already excessive consumption. Americans need to save. They don’t

need another flat-screen TV made in China.

The Obama administration needs to encourage the sort of saving that will put

consumers on sounder financial footing and free up resources that could be

directed at long overdue investments in transportation infrastructure,

alternative energy, education, worker training and the like. This strategy would

not only create jobs but would also cut America’s dependence on foreign saving

and imports. That would help reduce the current account deficit and the heavy

foreign borrowing such an imbalance entails.

We don’t need to reinvent the wheel to come up with effective saving policies.

The money has to come out of Americans’ paychecks. This can be either incentive

driven — expanded 401(k) and I.R.A. programs — or mandatory, like increased

Social Security contributions. As long as the economy stays in recession, any

tax increases associated with mandatory saving initiatives should be off the

table. (When times improve, however, that may be worth reconsidering.)

Fiscal policy must also be aimed at providing income support for newly

unemployed middle-class workers — particularly expanded unemployment insurance

and retraining programs. A critical distinction must be made between providing

assistance for the innocent victims of recession and misplaced policies aimed at

perpetuating an unsustainable consumption binge.

Crises are the ultimate in painful learning experiences. The United States

cannot afford to squander this opportunity. Runaway consumption must now give

way to a renewal of saving and investment. That’s the best hope for economic

recovery and for America’s longer-term economic prosperity.

Stephen S. Roach

is the chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia.

Dying of Consumption,

NYT, 28.11.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/28/opinion/28roach.html

Economic Scene

Buying Binge Slams to Halt

November 12, 2008

The New York Times

By DAVID LEONHARDT

Just as one crisis of confidence may be ending, another may be

coming.

The panic on Wall Street has eased in the last few weeks, and banks have become

somewhat more willing to make loans. But in those same few weeks, American

households appear to have fallen into their own defensive crouch.

Suddenly, our consumer society is doing a lot less consuming. The numbers are

pretty incredible. Sales of new vehicles have dropped 32 percent in the third

quarter. Consumer spending appears likely to fall next year for the first time

since 1980 and perhaps by the largest amount since 1942.

With Wall Street edging back from the brink, this crisis of consumer confidence

has become the No. 1 short-term issue for the economy. Nobody doubts that

families need to start saving more than they saved over the last two decades.

But if they change their behavior too quickly, it could be very painful.

Already, Circuit City has filed for bankruptcy, and General Motors has said that

it’s in danger of running out of cash. If the consumer slump continues, there is

a potential for a dangerous feedback loop, in which spending cuts and layoffs

reinforce each other.

“It’s a scary time,” Liz Allen, 29, a nursing student in Atlanta, told one of

the Times reporters who fanned out across the country last weekend to ask people

about the economy. “Worry can make the economy worse. If people worry too much,

they won’t spend as much money. We’re seeing that happen, I think, already.”

It’s not entirely clear what anyone, including Barack Obama and his incoming

administration, can do to temper the current worries. Mr. Obama has called for a

stimulus package, which will make up for some of the consumer pullback. He and

his advisers will also try to shore up confidence by projecting both a calm

competence and a willingness to be more aggressive than the Bush administration.

All of that should help.

But the stimulus package under discussion would bring no more than $150 billion

in new government spending. The difference between a good year for consumer

spending and a really bad one is about $400 billion.

So 2009 could turn out to be fairly miserable. The American consumer, long the

spender of last resort for the global economy, may finally be spent.

•

You have heard such warnings before, I realize. For years, journalists and other

economic worrywarts have been predicting a serious slump in consumer spending,

and it did not happen. “Never underestimate the American consumer,” as a Wall

Street cliché puts it.

Like most clichés, this one has some truth to it. Even before its recent

housing-fueled boom, consumer spending was a bigger part of the American economy

than of, say, the French or German economy. Americans like to buy things, and

they also don’t tend to stay pessimistic for long.

Andrew Kohut, president of the Pew Research Center, noted that his recent polls

showed a sharp rise in the number of people planning to cut back on spending —

but also a clear increase in the number who expected the economy to be in better

shape next year. “What the American economy has going for it is the innate

optimism of the public,” he said. “Americans get optimistic at the drop of a

hat.”

Perhaps falling gas prices or Mr. Obama’s victory will shake them out of their

torpor, Mr. Kohut said. A recent Gallup Poll found that consumer confidence rose

slightly after the election. (Links to the Pew and Gallup research are at

nytimes.com/economix.) Based on recent history, it’s easy to imagine that the

trend will continue and spending will soon bounce back.

Yet if the last year has proven anything, it’s that we should not assume

something can’t happen simply because it hasn’t happened recently. Cold economic

realities deserve the benefit of the doubt, even when they point to

uncomfortable conclusions. And right now, the economic realities are pointing to

a serious consumer recession.

Let’s start with the job market. It “already appears to be in worse shape than

at any time during the recessions of the early 1990s or early 2000s,” says

Lawrence Katz, a Harvard professor and former Labor Department chief economist.

Unemployment is higher than the official rate suggests, and it is rising.

Incomes, which for most families barely kept pace with inflation over the past

decade, are now falling.

In all, the total amount of income taken home by American households will still

probably rise next year, because the population will grow and government

transfer payments (like jobless benefits) will surely increase. But total real

income will rise a lot more slowly than it has been rising recently. One percent

is a reasonable estimate.

The next question is how much of that income people will spend. For decades —

from the 1950s through the 1980s — Americans spent about 91 percent of their

income, on average, and put away the rest. In the last few years, they have

spent close to 99 percent and saved only about 1 percent.

This simply cannot continue. For one thing, people need to pay down their debts

and replenish their retirement accounts. For another, the psychology of spending

and saving may well be changing. After the worst housing bust on record and one

of the three worst bear markets of the last century, Americans are probably

starting to realize that they can’t always fall back on ever-rising house values

or stock values to make ends meet.

In the unlikely event that Mr. Obama decided to mimic President Bush’s post-9/11

plea for spending in the name of patriotism, it probably would not have the same

impact. We’re not as flush as we were in 2001.

Economists are now busy trying to forecast how rapidly people will begin saving

again, but it’s essentially an exercise in guesswork. There is no good

historical analogy. A savings rate of about 3 percent seems plausible — higher,

but not radically so — and that’s what some forecasters are projecting.

At that rate, consumer spending would decline about 1 percent next year, which

is worse than it sounds. It would be the first annual decline since 1980, as I

mentioned above, and the biggest since 1942. Relative to the typical increases

from recent years, it would represent $400 billion in lost consumer spending. To

find a stimulus package so big, you’d have to go to Beijing.

And get this: Spending in the last few months has actually been falling at an

annual rate of 3 percent. So the seemingly pessimistic events I have sketched

out here are based on the assumption that things are about to get better.

As Joshua Shapiro of MFR, an economic research firm in New York, puts it, the

American consumer has quickly gone from being the world economy’s greatest

strength to its Achilles’ heel. “Everything has changed,” he says. “The

financial sector is deleveraging. Credit availability is severely constrained.

Asset prices are deflating. And household balance sheets are severely stressed.”

It would be silly to insist that a few terrible months meant the end of American

consumer culture. But it would be equally silly to assume that culture could

never change. It might be changing right now.

Robbie Brown, Sean Hamill

and John Dougherty contributed

reporting.

Buying Binge Slams to

Halt, NYT, 12.11.2008,

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/12/

business/economy/12leonhardt.html

NYC

We’re All Bankers Now.

So Why’s the A.T.M. Still

Charging

Us $2?

October 31, 2008

The New York Times

By CLYDE HABERMAN

According to our math, not the most reliable of guides, each

taxpayer in this country has a $1,785.71 ownership share in the banks of

America.

This figure is based on the $250 billion that the Treasury Department is

investing in banks to prod them to start lending again. We divided $250 billion

by 140 million, which the Internal Revenue Service says is the number of

individual tax returns filed last year. By our count, that gives every taxpayer

a $1,785.71 stake in JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, Wells Fargo, Bank of America and

the rest.

(In that 140 million, we are not including Charles J. O’Byrne, who resigned

under fire as Gov. David A. Paterson’s top lieutenant. We can’t be sure that Mr.

O’Byrne has fully recovered from what his lawyer calls late-filing syndrome when

it comes to his taxes. Also excluded is Joe the Publicity-Hungry Unlicensed

Plumber. Public records have shown that Joe suffers from Sticky Fingers Syndrome

in paying all that he owes.)

Far be it for us to tell Henry M. Paulson Jr., the treasury secretary, or Ben S.

Bernanke, the Federal Reserve chairman, how to manage $250 billion. They’re the

brains. And they’re doing a heck of a job. Thanks to all that brilliance in

Washington and on Wall Street, the rest of us now know how to make a small

fortune: by investing a large fortune.

But as shareholders, we have thoughts on aspects of banking that seem beyond the

scope of Messrs. Paulson and Bernanke. Call them small-bore issues. But they

affect ordinary people every day.

Let’s start with something really easy. Is it too much to ask that all banks

have pens that work on the counters with the deposit and withdrawal slips? In

too many places, the pens are useless. How can people feel confident that their

money is being managed wisely if those in charge can’t even provide a

functioning pen?

As shareholders, we were going to suggest that the top executives of the banks

forgo end-of-year bonuses, but Andrew M. Cuomo, New York’s attorney general, was

ahead of us. He sent a letter on Wednesday to nine big financial institutions

asking for information about their plans in this regard. It doesn’t guarantee

that mega-bonuses are finished. But, really, why should we give a dime to

executives who had to come to us hat in hand? Better to give an extra buck or

two to the guy in the subway with an outstretched plastic cup.

How about a moratorium on new bank branches in New York neighborhoods? The

tanking economy will probably take care of that anyway. But an ironclad

agreement by the banks to halt further expansion would delight New Yorkers. Many

are infuriated as they watch cherished local stores die and give way to

impersonal bank outlets, often located within yards of one another. Enough is

enough.

Why not forbid any bank receiving taxpayer money to purchase naming rights to

sports stadiums and arenas? Citigroup is handing the Mets something like $20

million a year to call their new stadium Citi Field. Surely, the Mets do not

need Citigroup’s money — not to mention yours — to keep failing to make the

playoffs.

Might we end the procedure by which banks stiff you when you deposit a large

check? Often, you are initially credited with only part of the deposit, and must

wait a few days to gain access to the rest. Meanwhile, the bank is using the

withheld portion to pick up a few bucks for itself. Check-clearance times have

been speeded up in recent years. But why shouldn’t depositors be able to get at

their money immediately, all of it?

For that matter, why must bank customers pay several times to retrieve cash at

an A.T.M. (known to some as short for Always Taking Money)? If you use an A.T.M.

at a bank other than your own, that bank usually charges you a fee. Fair enough.

But your own bank also charges you for the same transaction. So you pay twice

for the privilege — no, make that the right — to withdraw your own money. How is

that?

As long as we have $1,785.71 at stake, can’t we ask that banks have recognizable

names?

A few years ago, something called Sovereign Bank began popping up all over town.

We’d never heard of Sovereign. Now, just as we’ve been getting used to the name,

we learn that Sovereign has had it.

A full-page advertisement in Thursday’s paper announced that Sovereign had been

taken over by a company called Santander. What in the name of the Bailey Savings

and Loan is Santander?

Turns out that the full name is Banco Santander, based in Spain. Want to bet

that Santander left out “banco,” except in very small type at the bottom of the

ad, so that few would see right away that another piece of America had been

acquired by a foreign institution.

Sovereign, we hardly knew ye. But at least you didn’t go by a dopey moniker like

WaMu. That’s what Washington Mutual called itself before it, too, flopped. The

name WaMu will soon be gone, whammo!

Here’s hoping the same doesn’t happen to our $1,785.71.

We’re All Bankers

Now. So Why’s the A.T.M. Still Charging Us $2?, NYT, 31.10.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/31/nyregion/31nyc.html

Op-Ed Columnist

When Consumers Capitulate

October 31, 2008

The New York Times

By PAUL KRUGMAN

The long-feared capitulation of American consumers has

arrived. According to Thursday’s G.D.P. report, real consumer spending fell at

an annual rate of 3.1 percent in the third quarter; real spending on durable

goods (stuff like cars and TVs) fell at an annual rate of 14 percent.

To appreciate the significance of these numbers, you need to know that American

consumers almost never cut spending. Consumer demand kept rising right through

the 2001 recession; the last time it fell even for a single quarter was in 1991,

and there hasn’t been a decline this steep since 1980, when the economy was

suffering from a severe recession combined with double-digit inflation.

Also, these numbers are from the third quarter — the months of July, August, and

September. So these data are basically telling us what happened before

confidence collapsed after the fall of Lehman Brothers in mid-September, not to

mention before the Dow plunged below 10,000. Nor do the data show the full

effects of the sharp cutback in the availability of consumer credit, which is

still under way.

So this looks like the beginning of a very big change in consumer behavior. And

it couldn’t have come at a worse time.

It’s true that American consumers have long been living beyond their means. In

the mid-1980s Americans saved about 10 percent of their income. Lately, however,

the savings rate has generally been below 2 percent — sometimes it has even been

negative — and consumer debt has risen to 98 percent of G.D.P., twice its level

a quarter-century ago.

Some economists told us not to worry because Americans were offsetting their

growing debt with the ever-rising values of their homes and stock portfolios.

Somehow, though, we’re not hearing that argument much lately.

Sooner or later, then, consumers were going to have to pull in their belts. But

the timing of the new sobriety is deeply unfortunate. One is tempted to echo St.

Augustine’s plea: “Grant me chastity and continence, but not yet.” For consumers

are cutting back just as the U.S. economy has fallen into a liquidity trap — a

situation in which the Federal Reserve has lost its grip on the economy.

Some background: one of the high points of the semester, if you’re a teacher of

introductory macroeconomics, comes when you explain how individual virtue can be

public vice, how attempts by consumers to do the right thing by saving more can

leave everyone worse off. The point is that if consumers cut their spending, and

nothing else takes the place of that spending, the economy will slide into a

recession, reducing everyone’s income.

In fact, consumers’ income may actually fall more than their spending, so that

their attempt to save more backfires — a possibility known as the paradox of

thrift.

At this point, however, the instructor hastens to explain that virtue isn’t

really vice: in practice, if consumers were to cut back, the Fed would respond

by slashing interest rates, which would help the economy avoid recession and

lead to a rise in investment. So virtue is virtue after all, unless for some

reason the Fed can’t offset the fall in consumer spending.

I’ll bet you can guess what’s coming next.

For the fact is that we are in a liquidity trap right now: Fed policy has lost

most of its traction. It’s true that Ben Bernanke hasn’t yet reduced interest

rates all the way to zero, as the Japanese did in the 1990s. But it’s hard to

believe that cutting the federal funds rate from 1 percent to nothing would have

much positive effect on the economy. In particular, the financial crisis has

made Fed policy largely irrelevant for much of the private sector: The Fed has

been steadily cutting away, yet mortgage rates and the interest rates many

businesses pay are higher than they were early this year.

The capitulation of the American consumer, then, is coming at a particularly bad

time. But it’s no use whining. What we need is a policy response.

The ongoing efforts to bail out the financial system, even if they work, won’t

do more than slightly mitigate the problem. Maybe some consumers will be able to

keep their credit cards, but as we’ve seen, Americans were overextended even

before banks started cutting them off.

No, what the economy needs now is something to take the place of retrenching

consumers. That means a major fiscal stimulus. And this time the stimulus should

take the form of actual government spending rather than rebate checks that

consumers probably wouldn’t spend.

Let’s hope, then, that Congress gets to work on a package to rescue the economy

as soon as the election is behind us. And let’s also hope that the lame-duck

Bush administration doesn’t get in the way.

When Consumers

Capitulate, NYT, 31.10.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/31/opinion/31krugman.html

Economy Shrank In Third Quarter

as Consumers Retreat

October 30, 2008

Filed at 9:02 a.m. ET

The New York Times

By REUTERS

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - The U.S. economy shrank at a 0.3

percent annual rate in the third quarter, its sharpest contraction in seven

years as consumers cut spending and businesses reduced investment in the face of

rising fears that recession was setting in.

The Commerce Department said the third-quarter contraction in gross domestic

product was the steepest since the corresponding quarter in 2001 though it was

slightly less than the 0.5 percent rate of reduction that Wall Street economists

surveyed by Reuters had forecast.

The third-quarter contraction was a striking turnaround from the second

quarter's relatively brisk 2.8 percent rate of growth. It occurred when

financial market turmoil that has heightened concerns about a potentially

lengthy U.S. recession.

Consumer spending, which fuels two-thirds of U.S. economic growth, fell at a 3.1

percent rate in the third quarter - the first cut in quarterly spending since

the closing quarter of 1991 and the biggest since the second quarter of 1980.

Spending on nondurable goods - items like food and paper products - dropped at

the sharpest rate since late 1950.

Continuing job losses coupled with declining gains from stocks and other

investments have put consumers under severe stress. The GDP report showed that

disposable personal income dropped at an 8.7 percent rate in the third quarter -

the steepest since quarterly records on this component were started in 1947 --

after rising 11.9 percent in the second quarter when most of economic stimulus

payments still were flowing.

Consumers cut spending on durable goods like cars and furniture at a 14.1

percent annual rate in the third quarter, the biggest cut in this category of

spending since the beginning of 1987. Car dealers have said that sales have

virtually stalled, in part because tight credit makes it hard for even

creditworthy buyers to get loans.

Businesses also were clearly wary about the future, cutting investments at a 1

percent rate after boosting them 2.5 percent in the second quarter. It was the

first reduction in business investment since the end of 2006. Inventories of

unsold goods backed up at a $38.5-billion rate in the third quarter after rising

$50.6 billion in the second quarter.

Prices were still rising relatively strongly in the third quarter, with the

personal consumption expenditures index up at a 5.4 percent annual rate, the

sharpest since early 1990. Even excluding volatile food and energy items, core

prices grew at a 2.9 percent rate, up from the second quarter's 2.2 percent

rise.

However, many commodity prices in October have begun to ease and the Federal

Reserve indicated on Wednesday when it slashed interest rates again that its

concern for the future was focused more heavily on weak growth than on

inflation.

(Reporting by Glenn Somerville,

editing by Neil Stempleman)

Economy Shrank In

Third Quarter as Consumers Retreat,

NYT, 30.10.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/reuters/business/business-us-usa-economy.html

Consumers Gloomiest Ever

as Home Prices Plunge

October 28, 2008

Filed at 12:12 p.m. ET

The New York Times

By REUTERS

NEW YORK (Reuters) - U.S. consumer confidence dived to a

record low in October as plunging home values and a severe financial crisis left

Americans anxious about their jobs and pessimistic about the future.

The Conference Board said on Tuesday its index measuring consumer sentiment

tumbled to 38.0 in October, down from 61.4 in September and the lowest reading

since the index was first published back in 1967.

One factor depressing Americans was the rapidly declining value of their homes.

U.S. single-family home prices dropped a record 16.6 percent in August from a

year earlier and plummeted more than 30 percent in Las Vegas and Phoenix,

Standard & Poor's said on Tuesday.

This was making consumers feel a lot less wealthy and dampening their spending,

on which U.S. economic growth so keenly depends.

"Consumers are completely shut down at this point," said Lindsey Piegza, a

market analyst at FTN Financial. "They see no end in sight even with all the

actions that the government has taken."

The government has indeed done a lot. The Federal Reserve was expected to cut

interest rates yet again this week to prop up the economy and try to stimulate

lending, while the Treasury seemed to be trying to broaden its support of

industry to include insurers and automakers.

Yet none of this has stopped the carnage in the stock market, which on Tuesday

was struggling to hold in positive territory, and has already fallen nearly 25

percent in October alone.

The losses have also spread globally, with emerging markets showing an even more

virulent reaction to the prospect of a global recession, and theories about a

possible "decoupling" from the United States now shown to be largely

implausible.

HOLE IN THE BUDGET

The frantic efforts of U.S. financial authorities to restore calm in the markets

will also clearly come at a large long-term cost to taxpayers. Anthony Ryan, the

Treasury's acting undersecretary for domestic finance, said on Tuesday the

government faces huge borrowing needs this year to finance the multiple programs

aimed at soothing investors' nerves.

Against this backdrop, it is not hard to see why consumers had grown so glum. In

the Conference Board survey, the present situation index fell to 41.9, its

lowest since December 1992, from 61.1 in September The expectations subindex

plunged to a record low of 35.5 from an upwardly revised 61.5 last month and

from 80.0 a year ago.

The number of respondents who said jobs are "hard to get" rose to 37.2 percent

from 32.2, while those saying jobs were "plentiful" fell to 8.9 percent from

12.6.

Housing was another centerpiece of the economy's woes. According to S&P, home

prices in its narrower index of 10 metropolitan areas declined 1.1 percent from

July to August alone, and were down 17.7 percent from a year ago.

"The downturn in residential real estate prices continued, with very few bright

spots in the data," David M. Blitzer, chairman of the Index Committee at

Standard & Poor's, said in the statement.

(Reporting by Steven S. Johnson,

Pedro Nicolaci da Costa and Julie Haviv;

Editing by Andrea Ricci)

Consumers Gloomiest

Ever as Home Prices Plunge, NYT, 28.10.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/reuters/business/business-us-usa-economy.html

Yard Sales Boom,

and Sentiment Is First Thing to Go

October 25, 2008

The New York Times

By PATRICIA LEIGH BROWN

MANTECA, Calif. — As the classified ads put it, everything

must go. Socks. Christmas ornaments. Microwave ovens. Three-year-old Marita

Duarte’s tricycle was sold by her mother, Beatriz, to a stranger for $3 even as

her daughter was riding it.

On Mission Ridge Drive and other avenues, lanes and ways in this formerly

booming community, even birthday celebrations must go. “It was no money, no

birthday,” said Ms. Duarte, who lost her job as a floral designer two months

ago. The family commemorated Marita’s third birthday without presents last week,

the occasion marked by a small cake with Cinderella on the vanilla frosting.

They will move into a rental apartment next month.

An eternity ago, people in this city in northern San Joaquin County braved

four-hour round-trip commutes to the San Francisco Bay Area for a toehold on the

dream. Today, Manteca’s lawns and driveways are storefronts of the new

garage-sale economy — the telltale yellow signs plastered in the rear windows of

parked cars Friday through Sunday directing traffic to yet another sale, yet

another family.

“You can get great deals,” said Sharrell Johnson, 32, who was scouting for toys

in the Indian summer heat last Friday amid boxes of tools and DVDs and forests

of little skirts and shirts dangling from plastic hangers on suspended rope.

“Sad to say, you’re finding really good things. Because everybody’s losing their

homes.”

The garage-sale economy is flourishing here and in many other regions of the

country, so much so that some cities have begun cracking down. With more

residents trying to increase their income, the city of Weymouth, Mass., limited

yard sales to just three a year per address. Detective Sgt. Richard Fuller said

it was now common to see 15 cars parked in front of a house.

Richmond, Ind., has had such an onslaught of garage sale signs posted in the

right of way that the city has placed stickers on prominent light poles warning

of violations and fines.

But it is a Sisyphean task: Manteca’s ordinance, restricting residents to two

sales a year, is widely ignored.

The sales are part of the once-underground “thrift economy,” as a team of

Brigham Young University sociologists have called it, which includes thrift

stores, pawn shops and so-called recessionistas name-brand shopping at Goodwill.

“This is the perfect storm for garage sales,” said Gregg Kettles, a visiting

professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles who studies outdoor commerce.

“We’re coming off a 20-year boom in which consumers filled ever-bigger houses.

Now people need cash because of the bust.”

And so the garages and yards of Manteca, some tinder-dry from neglect, offer a

crash course in kitchen-table economics each weekend. On Klondike Way: “Tools,

various household items, & much more!” On Virginia Street: “Moving Sale! Fridge,

washer & dryer, men’s clothing, bike, BBQ, dinette, dresser, fans, microwaves,

recliner, DVD player. Everything must go!”

When life’s daily trappings and keepsakes are laid out for sale on a collapsible

table, sentiment is the first thing to go. “The cash helps a lot,” Constantino

Gonzalez, Ms. Duarte’s neighbor, said of the family’s second sale in two weeks,

in which he and his wife, Julia, were reluctantly selling their children’s

inflatable bounce house for $650, with pump.

Since losing his construction job, Mr. Gonzalez, 43, has been economizing,

disconnecting the family’s Internet and long-distance telephone service, and

barely using his truck and the Jeep, strewn with leaves in the driveway. He has

taken to picking up his children from school on his bicycle, with 6-year-old

Daniel on the handlebars, cushioned by a terry-cloth towel.

The inflatable bounce house is the children’s favorite toy, but the family’s

$1,800 mortgage payment is coming. So it sits propped up in its bright blue

case, awaiting customers, many of them desperate themselves. Customers are

searching for bargains on necessities so they might chip away at the rent, the

truck payment, the remodeling bill on the credit card.

“We need to eat,” Mr. Gonzalez tells his children about selling off their toys.

“I can’t cover the sun with my finger. So why lie?”

As he spoke, he watched his neighbor across the street pull out of her driveway

with her family for the last time, their pickup truck piled high with chairs,