|

Vocapedia

> Justice > USA > Incarceration

>

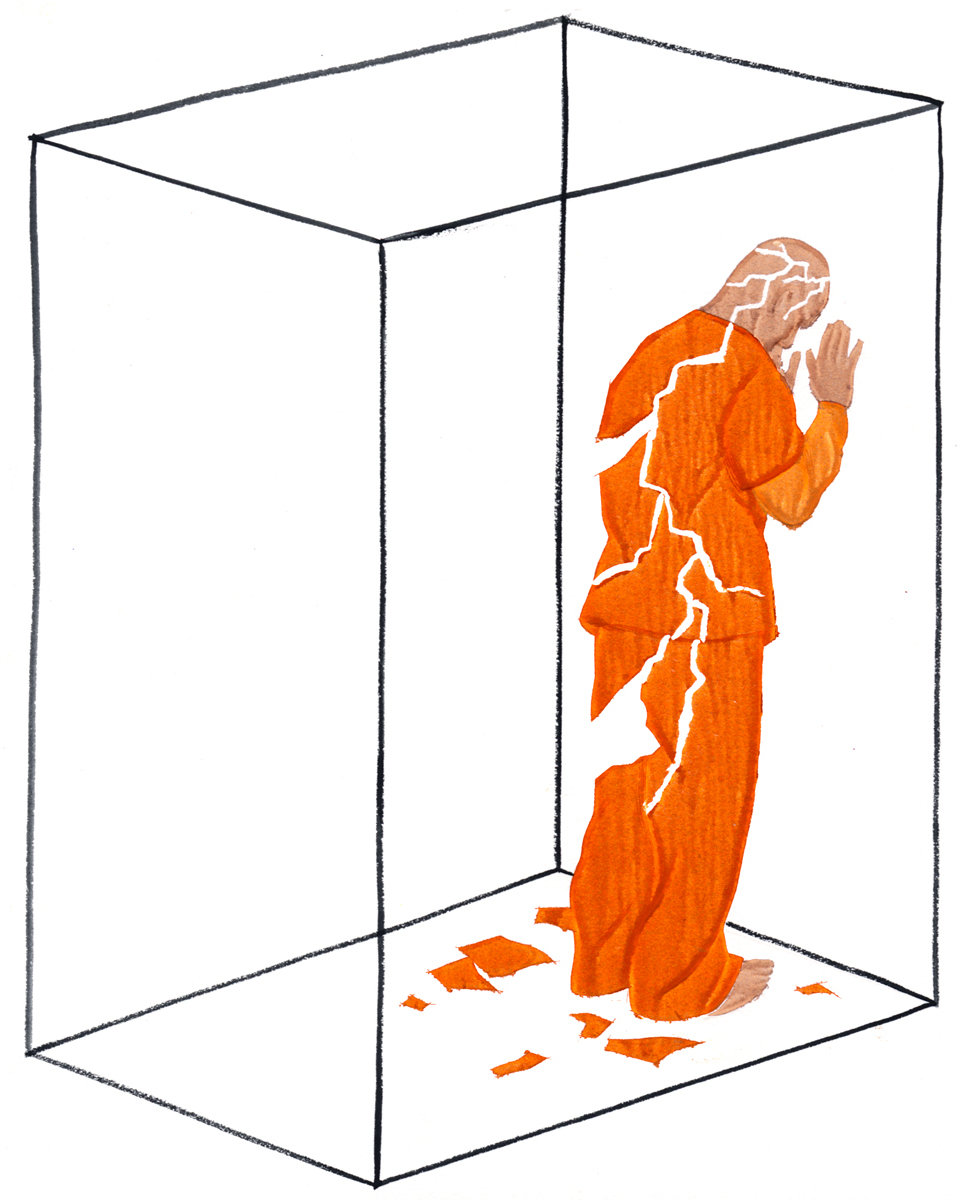

Solitary confinement

Matthieu Bourel

for The Marshall Project, NBC News and

ProPublica.

Source images:

Jonathan Knowles/Getty Images, simonkr/Getty

Images,

Image Source/Getty Images, Ranta

Images/Getty Images

Shackles and Solitary:

Inside Louisiana’s Harshest Juvenile Lockup

Teens at Louisiana’s newest juvenile lockup,

Acadiana Center for Youth at St.

Martinville,

were held in solitary confinement around the

clock,

shackled with leg irons and deprived of an

education.

“This is child abuse,” one expert said.

by Annie Waldman, ProPublica; Beth

Schwartzapfel,

The Marshall Project; and Erin Einhorn, NBC

News

ProPublica

March 10, 2022

https://www.propublica.org/article/

shackles-and-solitary-inside-louisianas-harshest-juvenile-lockup

Illustration: Alex Nabaum

Solitary Confinement Is Cruel and All Too Common

NYT By THE EDITORIAL

BOARD SEPT. 2, 2015

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/03/

opinion/solitary-confinement-is-cruel-common-and-useless.html

Illustration: Jeffrey Smith

My Night in Solitary

By RICK RAEMISCH NYT

FEB. 20, 2014

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/21/

opinion/my-night-in-solitary.html

Rick Raemisch,

the new executive director

of Colorado’s

Corrections Department,

in a solitary confinement cell

at the Colorado State

Penitentiary in Cañon City,

similar to the cell he stayed in.

Photograph:

Matthew Staver for The New York Times

After 20 Hours in Solitary, Colorado’s Prisons Chief Wins

Praise

By ERICA GOODE New York Times

MARCH 15, 2014

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/16/us/

after-20-hours-in-solitary-colorados-prisons-chief-wins-praise.html

The solitary confinement area of the Colorado State

Penitentiary.

Photograph:

Matthew Staver for The New York Times

After 20 Hours in Solitary, Colorado’s Prisons Chief Wins

Praise

By ERICA GOODE New York Times

MARCH 15, 2014

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/16/us/

after-20-hours-in-solitary-colorados-prisons-chief-wins-praise.html

isolation

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/11/us/

rethinking-solitary-confinement.html

isolation of inmates with H.I.V.

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/22/us/

alabama-to-end-isolation-of-inmates-with-hiv.html

USA >

solitary confinement UK / USA

2022

https://www.npr.org/2022/08/05/

1115885434/angola-three-albert-woodfox-dies

https://www.propublica.org/article/

shackles-and-solitary-inside-louisianas-harshest-juvenile-lockup - March 10,

2022

2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/21/

us/derek-chauvin-solitary-confinement.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/25/

opinion/solitary-confinement-reform.html

2018

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/28/

nyregion/solitary-confinement-lawsuit-young-inmates.html

https://www.npr.org/2018/07/31/

630602624/north-dakota-prison-officials-think-outside-the-box-to-revamp-solitary-confineme

2017

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/05/

opinion/sunday/solitary-confinement-prison-juveniles.html

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/07/13/

537076246/federal-report-criticizes-harsh-treatment-of-lewisburg-prisoners

http://www.npr.org/2017/04/04/

522513148/new-yorks-solitary-confinement-overhaul-gets-pushback-from-union

http://www.npr.org/2017/04/04/

522513148/new-yorks-solitary-confinement-overhaul-gets-pushback-from-union

2016

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/12/

opinion/chris-christies-defense-of-solitary-confinement.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/08/nyregion/rikers-island-

solitary-confinement.html

http://www.theguardian.com/world/commentisfree/2016/apr/28/

solitary-confinement-inhumane-prison-stories-6-x-9

http://www.theguardian.com/world/ng-interactive/2016/apr/27/

you-start-seeing-figures-in-the-paint-chips-recollections-of-life-in-solitary-confinement

http://www.npr.org/2016/04/18/

474397998/solitary-confinement-is-what-destroyed-my-son-grieving-mom-says

http://www.npr.org/sections/therecord/2016/04/06/

473260432/country-legend-merle-haggard-dies-at-79

http://www.npr.org/2016/03/24/

470824303/doubling-up-prisoners-in-solitary-creates-deadly-consequences

http://www.npr.org/2016/03/19/

470828257/after-decades-in-solitary-last-of-the-angola-3-carry-on-their-struggle

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/21/us/

for-45-years-in-prison-louisiana-man-kept-calm-and-held-fast-to-hope.html

https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/02/19/

467406096/last-of-angola-3-released-after-more-than-40-years-in-solitary-confinement

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/feb/19/

albert-woodfox-released-louisiana-jail-43-years-solitary-confinement

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/02/

opinion/president-obama-speaks-out-on-solitary.html

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/01/25/

463891388/obama-announces-reforms-to-solitary-confinement-in-federal-prisons

2015

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/18/nyregion/

new-york-prisons-take-an-unsavory-punishment-off-the-table.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/03/

opinion/solitary-confinement-is-cruel-common-and-useless.html

http://www.npr.org/2015/09/01/

436673728/california-prisons-to-limit-number-of-inmates-in-solitary-confinement

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2015/09/01/

436628891/californias-prisons-will-change-solitary-confinement-rules

http://www.npr.org/2015/08/24/

432622699/new-york-begins-to-question-solitary-confinement-as-default

http://www.npr.org/2015/08/24/

432622666/amid-backlash-against-isolating-inmates-new-mexico-moves-toward-change

http://www.npr.org/2015/08/23/

432622096/how-solitary-confinement-became-hardwired-in-u-s-prisons

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/16/us/

citing-safety-adult-jails-put-youths-in-solitary-despite-risks.html

http://www.npr.org/2015/07/27/

426742309/the-shock-of-confinement-the-grim-reality-of-suicide-in-jail

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/17/

magazine/the-law-that-keeps-people-on-death-row-despite-flawed-trials.html

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/07/03/

putting-fewer-innocents-behind-bars/

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/03/us/

glenn-ford-spared-death-row-dies-at-65.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/20/

opinion/justice-kennedy-on-solitary-confinement.html

http://www.npr.org/2015/06/12/

413730912/coming-home-straight-from-solitary-

damages-inmates-and-their-families

http://www.npr.org/sections/itsallpolitics/2015/06/09/

413184527/advocates-push-to-bring-solitary-confinement-

out-of-the-shadows

2014

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/22/

opinion/four-decades-of-solitary-in-louisiana.html

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/sep/04/

angola-three-albert-woodfox-lawsuit-louisiana-prison

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/29/nyregion/

new-law-boosts-oversight-of-use-of-solitary-confinement-at-rikers.html

http://parenting.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/07/20/

immaculate-incarceration-a-baby-in-solitary-confinement/

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/17/

opinion/what-is-this-child-doing-in-prison.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/26/nyregion/

complaint-by-fired-correction-officer-adds-details-about-a-death-at-rikers-island.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/16/us/

after-20-hours-in-solitary-colorados-prisons-chief-wins-praise.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/27/

opinion/efforts-to-curb-solitary-confinement.html

http://www.npr.org/2014/02/25/

282589184/before-lawmakers-former-inmates-tell-their-stories

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/21/

opinion/my-night-in-solitary.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/21/

opinion/new-york-rethinks-solitary-confinement.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/20/nyregion/

new-york-state-agrees-to-big-changes-in-how-prisons-discipline-inmates.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/18/

opinion/18dayan.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/08/us/

08hunger.html

6x9: a virtual experience of solitary confinement

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/world/series/

6x9--a-virtual-experience-of-solitary-confinement

http://www.theguardian.com/world/ng-interactive/2016/apr/27/

6x9-a-virtual-experience-of-solitary-confinement

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/apr/27/

6x9-could-you-survive-solitary-confinement-vr

Isolating

Inmates:

Solitary Confinement In The U.S.

http://www.npr.org/series/

434376567/isolating-inmates-solitary-confinement-in-the-u-s

http://www.npr.org/series/434376567/

isolating-inmates-solitary-confinement-in-the-u-s

solitary confinement for children

York

Correctional Institution for Women in Niantic, Conn.

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/17/

opinion/what-is-this-child-doing-in-prison.html

solitary confinement unit

/ solitary confinement for mentally ill

inmates

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/07/13/

537076246/federal-report-criticizes-harsh-treatment-of-lewisburg-prisoners

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/26/nyregion/

complaint-by-fired-correction-officer-adds-details-about-a-death-at-rikers-island.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/25/nyregion/

correction-officer-charged-with-indifference-in-death-of-rikers-island-inmate.html

solitary confinement

for mentally ill prisoners

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/30/us/

california-plans-to-reduce-isolation-of-mentally-ill-inmates.html

juvenile lockup >

Acadiana Center for Youth

at St. Martinville, Louisiana

https://www.propublica.org/article/

shackles-and-solitary-inside-louisianas-harshest-juvenile-lockup - March 10,

2022

the "Angola 3"

Albert Woodfox has

spent more time

in solitary

confinement

than any man alive in

the U.S. today

— 43 years. He and

Robert King

are the surviving

members of a group

known as the "Angola

Three."

Together with the

late Herman Wallace,

they spent more than

100 years

in solitary

confinement

for the 1972 death of

a prison guard,

Brent Miller,

at the maximum

security

Louisiana State

Penitentiary,

known as Angola.

No forensic evidence

tied the Angola Three

to Miller's killing,

and they always

maintained their innocence.

- March 19, 2016

5:36 PM ET

https://www.npr.org/2016/03/19/

470828257/after-decades-in-solitary-last-of-the-angola-3-carry-on-their-struggle

https://www.npr.org/tags/228566068/angola-three

https://www.npr.org/2022/08/05/

1115885434/angola-three-albert-woodfox-dies

https://www.npr.org/2016/03/19/

470828257/after-decades-in-solitary-last-of-the-angola-3-carry-on-their-struggle

https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/02/19/

467406096/last-of-angola-3-released-after-more-than-40-years-in-solitary-confinement

https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2015/06/12/

413973741/appeals-court-denies-immediate-release-to-last-of-angola-3

USA > Robert King > 29 years in solitary confinement

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2010/aug/28/

29-years-solitary-confinement-robert-king

50-square-foot cell

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/21/us/

for-45-years-in-prison-louisiana-man-kept-calm-and-held-fast-to-hope.html

suicide

http://www.npr.org/2015/07/27/

426742309/the-shock-of-confinement-the-grim-reality-of-suicide-in-jail

Corpus of news

articles

Justice > USA >

Prison, jail, inmates

Isolation,

Solitary confinement

My Night in Solitary

FEB. 20, 2014

The New York Times

By RICK RAEMISCH

COLORADO SPRINGS — AT 6:45 p.m. on Jan. 23, I was delivered to

a Colorado state penitentiary, where I was issued an inmate uniform and a mesh

bag with my toiletries and bedding. My arms were handcuffed behind my back, my

legs were shackled and I was deposited in Administrative Segregation — solitary

confinement.

I hadn’t committed a crime. Instead, as the new head of the state’s corrections

department, I wanted to learn more about what we call Ad Seg.

Most states now agree that solitary confinement is overused, and many — like New

York, which just agreed to a powerful set of reforms this week — are beginning

to act. When I was appointed, Gov. John Hickenlooper charged me with three

goals: limiting or eliminating the use of solitary confinement for mentally ill

inmates; addressing the needs of those who have been in solitary for long

periods; and reducing the number of offenders released directly from solitary

back into their communities. If I was going to accomplish these, I needed a

better sense of what solitary confinement was like, and what it did to the

prisoners who were housed there, sometimes for years.

My cell, No. 22, was on the second floor, at the end of what seemed like a very

long walk. At the cell, the officers removed my shackles. The door closed and

the feed tray door opened. I was told to put my hands through it so the cuffs

could be removed. And then I was alone — classified as an R.F.P., or “Removed

From Population.”

In regular Ad Seg, inmates can have books or TVs. But in R.F.P. Ad Seg, no

personal property is allowed. The room is about 7 by 13 feet. What little there

is inside — bed, toilet, sink — is steel and screwed to the floor.

First thing you notice is that it’s anything but quiet. You’re immersed in a

drone of garbled noise — other inmates’ blaring TVs, distant conversations,

shouted arguments. I couldn’t make sense of any of it, and was left feeling

twitchy and paranoid. I kept waiting for the lights to turn off, to signal the

end of the day. But the lights did not shut off. I began to count the small

holes carved in the walls. Tiny grooves made by inmates who’d chipped away at

the cell as the cell chipped away at them.

For a sound mind, those are daunting circumstances. But every prison in America

has become a dumping ground for the mentally ill, and often the “worst of the

worst” — some of society’s most unsound minds — are dumped in Ad Seg.

If an inmate acts up, we slam a steel door on him. Ad Seg allows a prison to run

more efficiently for a period of time, but by placing a difficult offender in

isolation you have not solved the problem — only delayed or more likely

exacerbated it, not only for the prison, but ultimately for the public. Our job

in corrections is to protect the community, not to release people who are worse

than they were when they came in.

Terry Kupers, a psychiatrist and expert on confinement, described in a paper

published last year the many psychological effects of solitary. Inmates reported

nightmares, heart palpitations and “fear of impending nervous breakdowns.” He

pointed to research from the 1980s that found that a third of those studied had

experienced “paranoia, aggressive fantasies, and impulse control problems ... In

almost all instances the prisoners had not previously experienced any of these

psychiatric reactions.”

Too often, these prisoners are “maxed out,” meaning they are released from

solitary directly into society. In Colorado, in 2012, 140 people were released

into the public from Ad Seg; last year, 70; so far in 2014, two.

The main light in my cellblock eventually turned off, and I fell into a fitful

sleep, awakening every time a toilet flushed or an officer yanked on the doors

to determine they were secure. Then there were the counts. According to the Ad

Seg rules, within every 24-hour period there are five scheduled counts and at

least two random ones. They are announced over the intercom and prisoners must

stand with their feet visible to the officer as he looks through the door’s

small window. As executive director, I praise the dedication, but as someone

trying to sleep and rest my mind — forget it. I learned later that a number of

inmates make earplugs out of toilet paper.

Thank you for sharing this harrowing account. Just one night spent in Solitary

starts the process of reducing a human being and those who...

When 6:15 a.m. and breakfast finally came, I brushed my teeth, washed my face,

did two sets of push-ups, and made my bed. I looked out my small window, saw

that it was still dark outside, and thought, now what?

I would spend a total of 20 hours in that cell. Which, compared with the typical

stay, is practically a blink. On average, inmates who are sent to solitary in

Colorado spend an average of 23 months there. Some spend 20 years.

Eventually, I broke a promise to myself and asked an officer what time it was.

11:10 a.m. I felt as if I’d been there for days. I sat with my mind. How long

would it take before Ad Seg chipped that away? I don’t know, but I’m confident

that it would be a battle I would lose.

Inmates in Ad Seg have, of course, committed serious crimes. But I don’t believe

that justifies the use of solitary confinement. My predecessor, Tom Clements,

who was as courageous a reformer as they come, felt the same way. Mr. Clements

had already gone a long way to reining in the overuse of solitary confinement in

Colorado. In little more than two years, he and his staff cut it by more than

half: from 1,505 inmates (among the highest rates in the country) to 726. As of

January, the number was down to 593. (We have also gotten the number of severely

mentally ill inmates in Ad Seg down to the single digits.)

But Mr. Clements had barely begun his work when he was assassinated last March.

In a tragic irony, he was murdered in his home by a gang member who had been

recently released directly from Ad Seg. This former inmate murdered a pizza

delivery person, allegedly for the purpose of wearing his uniform to lure Mr.

Clements to open his front door. A few days later, the man was killed in a

shootout with the Texas police after he had shot an officer during a traffic

stop. Whatever solitary confinement did to that former inmate and murderer, it

was not for the better.

When I finally left my cell at 3 p.m., I felt even more urgency for reform. If

we can’t eliminate solitary confinement, at least we can strive to greatly

reduce its use. Knowing that 97 percent of inmates are ultimately returned to

their communities, doing anything less would be both counterproductive and

inhumane.

Rick Raemisch is executive director

of the Colorado Department of Corrections.

A version of this op-ed appears in print

on February 21, 2014,

on page A25 of the New York edition with the headline:

My Night in Solitary.

My Night in Solitary,

NYT,

20.2.2014,

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/21/

opinion/my-night-in-solitary.html

New York State in Deal

to Limit Solitary Confinement

FEB. 19, 2014

The New York Times

By BENJAMIN WEISER

New York State has agreed to sweeping reforms intended to curtail the

widespread use of solitary confinement, including prohibiting its use in

disciplining prisoners under 18.

In doing so, New York becomes the largest prison system in the United States to

prohibit the use of disciplinary confinement for minors, according to the New

York Civil Liberties Union, which represented the three prisoners who se lawsuit

led to the agreement cited in court papers filed on Wednesday.

State correction officials will also be prohibited from imposing solitary

confinement as a disciplinary measure for inmates who are pregnant, and the

punishment will be limited to 30 days for those who are developmentally

disabled, the court filing says.

Related Coverage

document Document: Agreement Regarding Solitary ConfinementFEB. 19, 2014

The agreement imposes “sentencing guidelines” for all prisoners, specifying the

length of punishment allowed for different infractions and, for the first time

in all cases, a maximum length that such sentences may run, the civil liberties

group said. No such guidelines exist, except in cases involving certain violent

and drug-related offenses.

“New York State has done the right thing by committing to comprehensive reform

of the way it uses extreme isolation, a harmful and inhumane practice that has

for years been used as a punishment of first resort” in prisons, said Donna

Lieberman, executive director of the organization.

Several states, including Colorado, Mississippi and Washington, had begun to

look into how to reduce the use of solitary confinement; a Senate judiciary

subcommittee is holding a hearing next week on the issue.

Taylor Pendergrass, the lead lawyer in the case for the civil liberties group,

said a small number of states had also banned or limited the use of solitary

confinement for inmates under 18, in adult or juvenile detention facilities.

But given New York’s size and visibility, the agreement places the state “at the

vanguard” of progressive thinking about how to move away from “a very punitive

system that almost every state has adopted in one form or another over the last

couple of decades,” Mr. Pendergrass said.

The agreement also calls for the N.Y.C.L.U. and the state to each designate an

expert to assess current disciplinary practices across the state prisons and

recommend further changes.

If the reform process is successful, the lawsuit will be settled in two years,

the civil rights group said.

The filing, by lawyers for the plaintiffs and the state, asks the judge, Shira

A. Scheindlin of Federal District Court in Manhattan, to delay the litigation

while the process takes place. Judge Scheindlin gave that approval on Wednesday.

The agreement calls for the creation of a new post of assistant commissioner and

a separate research position to allow the Department of Corrections and

Community Supervision to “oversee and monitor the disciplinary system”

statewide, through data collection and tracking performance, with the goal of

“promoting consistency and fairness” in the imposition of such discipline.

Under the agreement, 16- and 17-year-old prisoners who are subjected to even the

most restrictive form of disciplinary confinement must be given at least five

hours of outdoor exercise and programming outside of their cells five days a

week. The state must also set aside space at designated facilities to

accommodate the minors who would normally be placed in solitary confinement.

The agreement followed months of negotiations between the office of the

governor, the attorney general and the Corrections Department. The plaintiffs

were represented by the civil rights organization; the law firm Morrison &

Foerster, which donated its services; and a prisoners’ rights expert, Alexander

A. Reinert, a professor at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law.

Anthony J. Annucci, acting commissioner of the Corrections Department, said the

agreement would result in “historic and appropriate changes in the use and

conditions of special housing units.”

He added that the changes would “make the disciplinary practices in New York’s

prisons more humane, and ultimately, our state’s criminal justice system more

fair and progressive, while maintaining safety and security.”

But the union representing state corrections officers, the New York State

Correctional Officers & Police Benevolent Association, was more critical of the

agreement.

“Today’s disciplinary confinement policies have evolved over decades of

experience, and it is simply wrong to unilaterally take the tools away from law

enforcement officers who face dangerous situations on a daily basis,” a

statement released by the union said. “Any policy changes must prioritize the

safety and security of everyone who works or lives in these institutions.”

There are about 3,800 state prisoners currently being held in “extreme

isolation” cells, known as special housing units or S.H.U.s, according to the

civil liberties group. The organization’s 2012 report, “Boxed In,” found that

from 2007 through 2011, corrections officials issued such sentences about 68,000

times for disciplinary reasons. The most common infraction was failure to obey

an order, which resulted in 35,000 such punishments, the data showed.

The average “extreme isolation” sentence was about five months, the report said,

with nearly 2,800 sentences of a year or more.

Such prisoners are held in their cells for 23 hours a day, receive their meals

through a slot in the cell door and are granted one hour of outdoor recreation

in a “walled-in solitary pen,” the civil liberties group says.

Roughly half of such inmates are confined alone, while the other half are held

with another prisoner in a space about the size of a parking spot, the report

says.

“Double-celled prisoners experience the same isolation and idleness, withdrawal

and anxiety, anger and depression as do prisoners living alone in the S.H.U.,”

the report said. But such inmates also must “endure the constant, unabating

presence of another man in their personal physical and mental space,” it added.

While disciplinary confinement makes up the vast majority of those placed in

solitary, a small percentage of prisoners are placed there for administrative

reasons or for protective custody.

The lawsuit that led to the agreement had originally been filed by a prisoner,

Leroy Peoples. The N.Y.C.L.U. later took on the case for Mr. Peoples, who had

spent two periods in isolation, totaling more than two years, according to the

suit.

Mr. Peoples had been convicted of two first-degree rapes and had been sentenced

to 13 to 16 years in prison. His infractions included possessing dietary

supplement pills and the filing of false liens against prosecutors in the Queens

district attorney’s office.

The civil liberties group later assumed representation of two more plaintiffs,

Tonja Fenton and Dewayne Richardson, who had also each sued without a lawyer,

and was intending to seek class-action status on behalf of all state inmates,

Mr. Pendergrass said.

A version of this article appears in print

on February 20, 2014,

on page A1 of the New York edition with the headline:

New York State in Deal to Limit Inmate Isolation.

New York State in Deal to Limit Solitary

Confinement,

NYT,

19.2.2014,

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/20/

nyregion/new-york-state-agrees-to-big-changes-

in-how-prisons-discipline-inmates.html

Barbarous Confinement

July 17, 2011

The New York Times

By COLIN DAYAN

Nashville

MORE than 1,700 prisoners in California, many of whom are in maximum isolation

units, have gone on a hunger strike. The protest began with inmates in the

Security Housing Unit at Pelican Bay State Prison. How they have managed to

communicate with each other is anyone’s guess — but their protest is everyone’s

concern. Many of these prisoners have been sent to virtually total isolation and

enforced idleness for no crime, not even for alleged infractions of prison

regulations. Their isolation, which can last for decades, is often not

explicitly disciplinary, and therefore not subject to court oversight. Their

treatment is simply a matter of administrative convenience.

Solitary confinement has been transmuted from an occasional tool of discipline

into a widespread form of preventive detention. The Supreme Court, over the last

two decades, has whittled steadily away at the rights of inmates, surrendering

to prison administrators virtually all control over what is done to those held

in “administrative segregation.” Since it is not defined as punishment for a

crime, it does not fall under “cruel and unusual punishment,” the reasoning

goes.

As early as 1995, a federal judge, Thelton E. Henderson, conceded that so-called

“supermax” confinement “may well hover on the edge of what is humanly

tolerable,” though he ruled that it remained acceptable for most inmates. But a

psychiatrist and Harvard professor, Stuart Grassian, had found that the

environment was “strikingly toxic,” resulting in hallucinations, paranoia and

delusions. In a “60 Minutes” interview, he went so far as to call it “far more

egregious” than the death penalty.

Officials at Pelican Bay, in Northern California, claim that those incarcerated

in the Security Housing Unit are “the worst of the worst.” Yet often it is the

most vulnerable, especially the mentally ill, not the most violent, who end up

in indefinite isolation. Placement is haphazard and arbitrary; it focuses on

those perceived as troublemakers or simply disliked by correctional officers

and, most of all, alleged gang members. Often, the decisions are not based on

evidence. And before the inmates are released from the barbarity of

22-hour-a-day isolation into normal prison conditions (themselves shameful) they

are often expected to “debrief,” or spill the beans on other gang members.

The moral queasiness that we must feel about this method of extracting

information from those in our clutches has all but disappeared these days,

thanks to the national shame of “enhanced interrogation techniques” at

Guantánamo. Those in isolation can get out by naming names, but if they do so

they will likely be killed when returned to a normal facility. To “debrief” is

to be targeted for death by gang members, so the prisoners are moved to

“protective custody” — that is, another form of solitary confinement.

Hunger strikes are the only weapon these prisoners have left. Legal avenues are

closed. Communication with the outside world, even with family members, is so

restricted as to be meaningless. Possessions — paper and pencil, reading matter,

photos of family members, even hand-drawn pictures — are removed. (They could

contain coded messages between gang members, we are told, or their loss may

persuade the inmates to snitch when every other deprivation has failed.)

The poverty of our criminological theorizing is reflected in the official

response to the hunger strike. Now refusing to eat is regarded as a threat, too.

Authorities are considering force-feeding. It is likely it will be carried out —

as it has been, and possibly still continues to be — at Guantánamo (in possible

violation of international law) and in an evil caricature of medical care.

In the summer of 1996, I visited two “special management units” at the Arizona

State Prison Complex in Florence. A warden boasted that one of the units was the

model for Pelican Bay. He led me down the corridors on impeccably clean floors.

There was no paint on the concrete walls. Although the corridors had skylights,

the cells had no windows. Nothing inside could be moved or removed. The cells

contained only a poured concrete bed, a stainless steel mirror, a sink and a

toilet. Inmates had no human contact, except when handcuffed or chained to leave

their cells or during the often brutal cell extractions. A small place for

exercise, called the “dog pen,” with cement floors and walls, so high they could

see nothing but the sky, provided the only access to fresh air.

Later, an inmate wrote to me, confessing to a shame made palpable and real: “If

they only touch you when you’re at the end of a chain, then they can’t see you

as anything but a dog. Now I can’t see my face in the mirror. I’ve lost my skin.

I can’t feel my mind.”

Do we find our ethics by forcing prisoners to live in what Judge Henderson

described as the setting of “senseless suffering” and “wretched misery”? Maybe

our reaction to hunger strikes should involve some self-reflection. Not allowing

inmates to choose death as an escape from a murderous fate or as a protest

against continued degradation depends, as we will see when doctors come to make

their judgment calls, on the skilled manipulation of techniques that are

indistinguishable from torture. Maybe one way to react to prisoners whose only

reaction to bestial treatment is to starve themselves to death might be to do

the unthinkable — to treat them like human beings.

Colin Dayan,

a professor of English at Vanderbilt University,

is the author of “The Law Is a White Dog:

How Legal Rituals Make and Unmake

Persons.”

Barbarous Confinement,

NYT, 17.7.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/18/opinion/18dayan.html

Two Decades in Solitary

September 23, 2008

The New York Times

By JOHN ELIGON

He is one of New York’s most isolated prisoners, spending 23 hours a day for

the past two decades in a 9-by-6-foot cell. The only trimmings are a cot and a

sink-toilet combination. His visitors — few as they are — must wedge into a nook

outside his cell and speak to him through a 1-by-3-foot window of foggy

plexiglass and iron bars.

In this static existence, Willie Bosket, 45, seems to have gone from defiant

menace to subdued and empty inmate.

It was 30 years ago this month that a state law took effect allowing juveniles

to be tried as adults, largely in response to Mr. Bosket’s slaying of two people

on a New York subway when he was 15. He served only five years in jail for that

crime because he was a juvenile, sparking public outrage. But shortly after

completing his sentence, Mr. Bosket was arrested for assaulting a 72-year-old

man.

He once claimed to be at “war” with prison officials. He said he laughed at the

system and claimed to have committed more than 2,000 crimes as a child. He set

fire to his cell and attacked guards. Mr. Bosket was sentenced to 25 years to

life for stabbing a guard in the visitors’ room in 1988, along with other

offenses, leading prison authorities to make him virtually the most restricted

inmate in the state.

Now Mr. Bosket, who has gone 14 years without a disciplinary violation, does

mainly three things: read, sleep and think.

“Just blank” is how Mr. Bosket described his existence during a recent interview

at Woodbourne Correctional Facility, about 75 miles north of Manhattan.

“Everything is the same every day. This is hell. Always has been.”

He is scheduled to remain isolated from the general prison population until

2046.

Mr. Bosket’s seclusion is part of a bigger debate over the confinement of

troublesome inmates and the role of the prison system. Some say that Mr.

Bosket’s level of seclusion is draconian, that he should be given an opportunity

to rejoin the general population.

“He is a very dangerous person; he’s killed people,” said Jo Allison Henn, a

lawyer who helped represent Mr. Bosket roughly 20 years ago when he fought

unsuccessfully to have some of his restrictions removed. “I’m not saying he

should be released from custody entirely, just the custody that he is in. It is

beyond inhumane. I don’t think that too many civilized countries do that.”

But proponents of Mr. Bosket’s restrictions say he has proved to be something of

an incorrigible danger to prison guards and other inmates and cannot be trusted

in the general population. He is evaluated periodically, meaning he could rejoin

the general prison population before 2046, said Erik Criss, a spokesman for the

Department of Corrections.

“This guy was violent or threatening violence practically every day,” Mr. Criss

said. “Granted, it has been a while, but there are consequences for being

violent in prison. We have zero tolerance for that.”

From 1985 to 1994, Mr. Bosket was written up nearly 250 times for disciplinary

violations that included spitting on guards, throwing food and swallowing the

handle of a spoon, according to prison reports.

Few, if any, of the state’s current inmates have been in disciplinary housing

longer than Mr. Bosket, said Linda Foglia, a spokeswoman for the corrections

department.

Mr. Bosket says he wakes up at 7:15 every morning and gets a visit from a

counselor at 8. At 9, he gets his first of three doses of medication for asthma

and high cholesterol, he said. Lunch comes at 11:30, followed by more medication

at 1 p.m. and 5 p.m.

He is entitled to three showers a week. Other than one hour of recreation a day,

also solitary, he may leave his cell only for medical visits and haircuts. The

recreation area measures 34 feet by 17 feet, surrounded by nearly 9-foot-high

walls with bars on the top. Mr. Bosket said he was chained to a door during his

recreation time and could not walk more than six feet, but corrections officials

disputed that account, saying he was allowed to roam freely during his hour like

other inmates.

And while other prisoners in isolation are escorted to a visiting room when they

have guests, he must stay in his cell, speaking through the plexiglass.

Most of his waking hours, he said, are spent reading books, magazines,

newspapers and anything else he can get his hands on. His favorite magazine, he

said, was Elle.

“It’s very colorful,” he said. “It keeps me up to date on technology and the

world.”

Mr. Bosket has long been known as a paradox, a man of charm and extraordinary

intelligence but also of inexplicable fits of rage.

“It was like a terrifying metamorphosis when this spark within him went off, and

you could see the rage in him building,” said Robert Silbering, a former

prosecutor who tried Mr. Bosket for the subway murders. “I never have seen

anything like that before or afterward.”

The killings led Gov. Hugh L. Carey to sign a law allowing people as young as 13

to be tried as adults for murder. Mr. Bosket said he saw it as something of an

honor that he could drastically change a justice system that he said made him a

“monster.”

“If I’m the perfect example, then I’ve been taught well,” he said.

At the sight of a recent visitor, Mr. Bosket cheerfully nodded and, revealing a

small gap between his front teeth, gave a friendly, “Hi, how’s it going?”

He spoke with the aura of a professor, using deliberate gestures and emphasizing

the ends of many words. He often spoke in metaphors and used stories and

quotations to explain his philosophies.

As he contemplated his words, Mr. Bosket often folded his right arm across his

bulging stomach and lay the fingers of his left hand across his mouth and nose.

He sometimes rocked in his chair.

Despite his bleak situation, Mr. Bosket refused to concede defeat: “I’m not

broken down and never will be.”

His life has always been empty, he said.

“I grew up with nothing,” he said. “I was born with nothing. I still have

nothing. I will never have nothing. Forty-five years of living the way I have

lived, I like ‘nothing.’ No one can take ‘nothing’ from you.”

Mr. Bosket, who has spent all but two years in some form of lockup since he was

9, also said he had formed a “breastplate” from a lifetime of incarceration.

“I’ve become so callous to the poking of the sword that, literally, instead of

bleeding to death, the blood was drained and I became absent of concern, void of

emotions, cold — plain cold to the degree that not much affects me anymore,” he

said.

Yet Mr. Bosket did hint at something of a life of suffering.

“If somebody came to me with a lethal injection, I’d take it,” he said. “I’d

rather be dead.”

His change from vicious to quiescent, Mr. Bosket said, was a calculated move.

Growing up in Harlem, Mr. Bosket said, his heroes were revolutionaries like Huey

Newton and Assata Shakur. He said he believed blacks needed to use violence to

survive in the 1970s and ’80s.

But in 1994, he said, he sensed a change in society. “Blacks don’t need to go

and attack to get their message across,” he recalled thinking.

He said that he also wanted young people to see positive in his life, and that

continued violence could be counterproductive.

“I don’t believe at this point it’s strategic for me to be aggressive or

violent,” he said. “I’ve made my point.”

“I’m not proud of a lot of the things I’ve done,” he added.

Mr. Bosket’s sister, Cheryl Stewart, 51, said her brother had expressed remorse

in letters.

“What was done was wrong, and if he could redo it, he wouldn’t do it again,” she

said. “He knows what was done was wrong and is just sorry for what all has went

down.”

Though she corresponds with her brother, Ms. Stewart said she had not visited

him in 23 years because it was difficult to see him so confined. Mr. Bosket is

lucky to receive more than two visits a year.

Adam Mesinger, a television and movie producer, said he had visited Mr. Bosket

seven times over the past four years and is shopping a script for a movie about

Mr. Bosket’s life. He said that Mr. Bosket had always been warm and open with

him and that he would consider him a friend.

“I have no fear of him,” Mr. Mesinger said. “I don’t think he would ever harm

me. I don’t think he ever really wants to harm anybody.”

But not even Mr. Bosket would say that his days of violence are behind him.

“When you’re in hell,” he said, “you can’t predict the future.”

Two Decades in Solitary,

NYT,

23.9.2008,

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/23/

nyregion/23inmate.html

Explore more on these topics

Anglonautes > Vocapedia

prison, jail > USA

justice, law, death penalty,

U.S. Constitution, U.S. Supreme Court > USA

justice, law, prison > UK

justice > courtroom artists > UK,USA

miscarriage of justice > UK, USA

terrorism

> USA > Guantánamo Bay

mental health, psychology

Related > Anglonautes >

Videos >

Documentaries >

2010s > USA

Justice > Prison

|