|

Vocapedia >

Law > USA > U.S. Supreme court

Law, Constitution, Regulation

Walt Handelsman

Political cartoon

GoComics

June 24,

2016

https://www.gocomics.com/walthandelsman/2016/06/24

Left:

Barack Obama

Related

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/24/

us/supreme-court-immigration-obama-dapa.html

Samantha Elauf, center, with Majda Elauf, her mother,

and David Lopez, general counsel

for the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission,

on Wednesday.

Photograph: Chip Somodevilla

Getty Images

In a Case of Religious Dress,

Justices Explore the Obligations

of Employers

NYT

FEB. 25, 2015

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/26/

us/in-a-case-of-religious-dress-justices-explore-the-obligations-of-employers.html

podcasts > before 2024

The Supreme Court / High Court

/ top court

the highest

tribunal in the United States

for all cases and controversies

arising under the

Constitution

https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs

https://www.supremecourt.gov/

https://www.nytimes.com/topic/organization/

us-supreme-court

2024

https://www.npr.org/2024/07/02/

nx-s1-5026959/supreme-court-term

https://www.gocomics.com/johndeering/2024/05/19

2023

https://www.npr.org/2023/07/05/

1185864571/chief-justice-takes-back-the-reins-at-the-supreme-court-this-term

https://www.npr.org/2023/07/03/

1185712684/vp-kamala-harris-says-

the-supreme-court-took-rights-from-the-people-of-america

https://www.npr.org/2023/06/28/

1183337280/supreme-court-ethics-financial-disclosures-

possible-conflicts-of-interest

https://www.npr.org/2023/06/06/

1180389289/supreme-court-supermajority-michael-waldman-abortion-guns

https://www.npr.org/2023/05/22/

1177228505/supreme-court-shadow-docket

https://www.gocomics.com/claybennett/2023/05/06

2022

https://www.npr.org/2022/10/08/

1127288778/supreme-court-artist-retires-

45-years-documenting-art-lien-sketches-drawings

https://www.gocomics.com/claybennett/2022/06/25

https://www.gocomics.com/mikeluckovich/2022/06/24

https://www.npr.org/2022/05/07/

1097382507/supreme-court-abortion-clarence-thomas-bullied-roe-v-wade

2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/30/

opinion/supreme-court-republican.html

https://www.npr.org/2021/11/03/

1049380749/gun-rights-supreme-court-arguments-new-york

https://www.npr.org/2021/09/17/

1038272245/justice-clarence-thomas-says-the-supreme-court-is-flawed-but-still-works

https://www.npr.org/2021/09/08/

1035383975/supreme-court-stay-of-execution-john-henry-ramirez-texas-pastor

https://www.npr.org/2021/09/03/

1033733918/the-supreme-court-heads-toward-reversing-abortion-rights

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/sep/02/

us-supreme-court-texas-abortion-law-cruel-partisan

https://www.npr.org/2021/07/23/

1019746478/on-abortion-mississippi-swings-for-the-fences-

asks-the-supreme-court-to-reverse-

https://www.npr.org/2021/06/02/

1002482606/the-supreme-court

https://www.npr.org/2021/05/17/

997478374/supreme-court-to-review-mississippi-abortion-ban

https://www.npr.org/2021/04/28/

991683886/frightened-to-death-

cheerleader-speech-case-gives-supreme-court-pause

https://www.npr.org/2021/04/28/

988083256/at-supreme-court-mean-girls-meet-1st-amendment

https://www.npr.org/2021/02/12/

966747620/supreme-court-

stays-execution-of-alabama-inmate-who-requested-pastors-presence

2020

https://www.npr.org/2020/12/31/

951620847/supreme-courts-new-supermajority-what-it-means-for-roe-v-wade

https://www.npr.org/2020/12/07/

943937968/supreme

2019

https://www.npr.org/2019/02/07/

690319510/supreme-court-

stops-louisiana-abortion-law-from-being-implemented

2018

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/05/

opinion/supreme-courts-legitimacy-crisis.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/05/

opinion/brett-kavanaugh-supreme-court-trump.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/05/

opinion/brett-kavanaugh-senate-susan-collins.html

https://www.npr.org/2018/10/02/

653492150/is-8-enough-

the-consequences-of-the-supreme-court-starting-one-justice-down

https://www.npr.org/2018/09/29/

652944082/trump-administration-

moves-to-escalate-census-lawsuits-to-supreme-court

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/23/

opinion/columnists/supreme-court-brett-kavanaugh-partisan-republicans.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/13/

opinion/editorials/kavanaugh-supreme-court-divide.html

https://www.npr.org/2018/09/05/

644824174/the-most-dangerous-branch-

asks-whether-the-supreme-court-has-become-too-powerful

https://www.npr.org/2018/07/07/

626711777/religion-the-supreme-court-and-why-it-matters

https://www.npr.org/2018/07/07/

626711777/religion-the-supreme-court-and-why-it-matters

https://www.theguardian.com/law/2018/jul/02/

supreme-court-donald-trump-anthony-kennedy-conservative-nominee-republicans

https://www.npr.org/2018/07/01/

624838031/a-lifetime-investment-big-money-pours-into-supreme-court-battle

https://www.npr.org/2018/06/30/

624918050/justice-kennedy-

may-soon-find-himself-disappointed-and-his-legacy-undermined

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/28/

opinion/sunday/the-right-has-won-the-supreme-court-now-what.html

https://www.npr.org/2018/06/04/

605003519/supreme-court-decides-in-favor-of-baker-over-same-sex-couple-in-cake-shop-case

https://www.npr.org/2018/05/29/

606163667/in-win-for-privacy-rights-court-says-police-need-warrant-to-search-area-around-h

https://www.npr.org/2018/05/29/

615149823/supreme-court-declines-to-take-up-appeal-of-restrictive-abortion-ban-in-arkansas

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/28/

opinion/sunday/justice-kennedy-supreme-court-open-letter.html

https://www.npr.org/2018/04/17/

603160263/supreme-court-strikes-down-part-of-immigration-law

https://www.npr.org/2018/03/05/

590920670/from-fraud-to-individual-right-where-does-the-supreme-court-stand-on-guns

https://www.npr.org/2018/02/27/

589096901/supreme-court-ruling-means-immigrants-can-continue-to-be-detained-indefinitely

https://www.npr.org/2018/02/26/

588813001/supreme-court-declines-to-take-up-key-daca-case-for-now

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/26/

us/politics/supreme-court-trump-daca-dreamers.html

https://www.npr.org/2018/02/21/

587733571/supreme-court-gets-moving-issuing-as-many-decisions-in-one-day-as-it-has-in-5-mo

https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2018/02/20/

587330832/supreme-court-wont-hear-challenge-to-california-s-gun-laws

https://www.npr.org/2018/01/17/

578479044/do-you-have-the-right-to-plead-not-guilty-when-your-lawyer-disagrees

2017

https://www.npr.org/2017/12/05/

568653522/supreme-court-sharply-divided-over-same-sex-wedding-cake-case

http://www.npr.org/2017/10/06/

555862822/no-class-action-supreme-court-weighs-whether-workers-must-face-arbitrations-alon

http://www.npr.org/2017/10/03/

552904504/this-supreme-court-case-could-radically-reshape-politics

http://www.npr.org/2017/10/01/

554538819/supreme-court-to-open-a-whirlwind-term

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/09/28/

554225345/supreme-court-adds-more-cases-to-2017-2018-session-including-union-dispute

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/09/25/

553490088/supreme-court-removes-cases-over-trumps-travel-ban-from-calendar

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/07/14/

537159288/hawaii-judge-exempts-grandparents-and-other-relatives-from-trump-travel-ban

http://www.npr.org/2017/06/20/

533657035/as-term-winds-down-supreme-court-says-it-will-take-on-political-gerrymandering

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/02/us/

politics/travel-ban-supreme-court-trump.html

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/06/02/

531158852/trump-asks-supreme-court-to-reinstate-travel-ban

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/05/26/

530289200/life-without-parole-sentences-for-d-c-sniper-thrown-out-by-judge

http://www.npr.org/2017/05/23/

529634901/supreme-court-rejects-2-n-c-congressional-districts-as-unconstitutional

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/05/01/

526413560/cities-can-sue-big-banks-over-effects-of-discriminatory-practices-supreme-court

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/04/

opinion/the-supreme-court-as-partisan-tool.html

http://www.npr.org/2017/03/06/

518877248/supreme-court-allows-prying-into-jury-deliberations-if-racism-is-perceived

www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/03/06/

518795387/supreme-court-wont-hear-transgender-teens-challenge-to-bathroom-policy

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/04/

opinion/sunday/will-the-supreme-court-stand-up-to-trump.html

http://www.npr.org/2017/01/11/

509179589/supreme-court-considers-how-schools-support-students-with-disabilities

2016

http://www.npr.org/2016/12/27/

506332876/from-delay-to-action-the-supreme-court-to-take-a-conservative-turn-in-2017

http://www.nytimes.com/video/opinion/

100000004677716/supreme-court-v-the-american-voter.html - 2016

http://www.npr.org/2016/09/29/

495960902/the-supreme-court-a-winning-issue-in-the-presidential-campaign

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/28/us/

abortion-rights-supporters-find-ruling-a-practical-and-symbolic-victory.html

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/06/27/us/

eight-member-supreme-court.html

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/02/29/us/

why-the-abortion-clinics-have-closed.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/28/us/

supreme-court-texas-abortion.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/26/

opinion/sunday/the-supreme-courts-silent-failure-on-immigration.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/24/us/

supreme-court-immigration-obama-dapa.html

http://www.gocomics.com/walthandelsman/2016/06/24

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/31/

opinion/suppress-votes-id-rather-lose-my-job.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/18/

opinion/resetting-the-post-scalia-supreme-court.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/15/

opinion/the-supreme-court-after-justice-scalia.html

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/02/14/us/

politics/scalia-opinions.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/11/

opinion/the-court-blocks-efforts-to-slow-climate-change.html

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/02/10/

466258777/supreme-court-puts-white-houses-carbon-pollution-limits-on-hold

2015

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/10/

opinion/guns-and-thunder-on-the-supreme-courts-right.html

http://www.npr.org/2015/12/07/

458815934/rejecting-appeal-on-assault-ban-supreme-court-again-stays-out-of-gun-policy

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/09/

opinion/the-illusion-of-a-liberal-supreme-court.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/05/

opinion/sunday/the-activist-roberts-court-10-years-in.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/05/

opinion/sunday/linda-greenhouse-the-supreme-court-and-the-politics-of-fear.html

http://www.npr.org/2015/07/02/

419468563/was-the-most-current-supreme-court-session-a-liberal-term-for-the-ages

http://www.supremecourt.gov/oral_arguments/audio/2014/14-556-q1

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2015/06/26/

417731614/obama-supreme-court-ruling-on-gay-marriage-a-victory-for-america

http://www.npr.org/2015/06/26/

417754255/how-the-high-court-has-changed-the-legal-landscape-for-same-sex-marriage

http://www.npr.org/2015/06/26/

417754169/supreme-court-rules-that-all-states-must-allow-same-sex-marriages

http://www.npr.org/2015/06/26/

417754210/today-at-the-high-court-a-triumph-for-gay-rights-advocates

http://www.npr.org/2015/06/26/

417840345/supreme-court-changes-face-of-marriage-in-historic-ruling

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2015/06/26/

417717613/supreme-court-rules-all-states-must-allow-same-sex-marriages

http://www.npr.org/sections/itsallpolitics/2015/06/15/

414490496/whats-left-for-the-supreme-court-same-sex-marriage-obamacare-and-more

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2015/06/26/

417720924/roberts-celebrate-todays-decision-but-do-not-celebrate-the-constitution

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/22/us/

at-supreme-court-holders-justice-dept-routinely-backs-officers-use-of-force.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/03/

opinion/the-supreme-courts-secret-decisions.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/27/us/

oklahoma-asks-justices-to-delay-executions.html

http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2015/01/26/

the-supreme-court-meets-the-real-world

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/17/us/

supreme-court-to-decide-whether-gays-nationwide-can-marry.html

2014

http://www.npr.org/blogs/thetwo-way/2014/05/05/

309752095/prayers-before-town-hall-meetings-are-constitutional-high-court-finds

2013

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/06/

opinion/sunday/the-supreme-court-returns.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/27/

opinion/the-same-sex-marriage-rulings.html

2012

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/08/us/

supreme-court-agrees-to-hear-two-cases-on-gay-marriage.html

2011

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/12/28/

what-we-think-about-when-we-think-about-the-court/

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/05/

opinion/05sat1.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/19/us/19scotus.html

https://www.reuters.com/article/newsOne/idUSWAT009353

20080417

http://www.economist.com/agenda/displayStory.cfm?story_id=4366298

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/11/03/

politics/politicsspecial1/03legal.html

http://www.nytimes.com/pages/politics/politicsspecial1/index.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/25/

politics/25schiavo.html

This revision of “The U.S. Supreme Court:

Equal Justice Under the Law”

is a collection of essays that explains

how the highest court in the United States

functions.

It has been updated

to reflect the appointments of new justices

and recent, significant decisions of the court.

- United States Department of State

Bureau of International information Programs

US Supreme Court: Equal Justice Under the Law

ISBN: 978–1–625–92001–

http://photos.state.gov/libraries/korea/49271/april_2014/

dwoa_0313_The_US_Supreme_Court__Equal_Justice_Under_the_Law.pdf

the pinnacle of the judicial system

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/27/us/

politics/27court.html

'Equal Justice Under Law'

https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/courtbuilding.pdf

https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/constitutional.aspx

term

http://www.npr.org/2017/10/01/

554538819/supreme-court-to-open-a-whirlwind-term

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/17/us/

supreme-court-to-decide-whether-gays-nationwide-can-marry.html

debates > Supreme Court’s Ban on Cameras

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/24/

opinion/open-the-supreme-court-to-cameras.html

the top court

Historic Supreme Court Decisions - by Party

Name

https://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/cases/name.htm

deadlocked Supreme

Court

http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2016/05/18/

is-a-deadlocked-supreme-court-such-a-bad-thing

Religion and The Supreme Court

https://www.npr.org/2018/07/07/

626711777/religion-the-supreme-court-and-why-it-matters

U.S. Supreme Court >

gun control

https://www.gocomics.com/mikeluckovich/2022/06/24

https://www.npr.org/2018/03/05/

590920670/from-fraud-to-individual-right-where-does-the-supreme-court-stand-on-guns

decline to hear

a

Second Amendment case,

turning away a

constitutional challenge

to a 10-day waiting

period

for the purchase of

guns in California.

The court's decision

not to hear the case

came over an angry

dissent

from conservative

Justice

Clarence Thomas.

https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2018/02/20/

587330832/supreme-court-wont-hear-challenge-to-california-s-gun-laws

decline

to hear

a Second Amendment

challenge

to a California law

that places strict

limits

on carrying guns in public.

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/26/us/

politics/supreme-court-guns-public-california.html

turned away Second Amendment cases

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/26/

us/politics/supreme-court-guns-public-california.html

Trump administration

> file a motion with the Supreme Court

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/07/14/

537159288/hawaii-judge-exempts-grandparents-and-other-relatives-from-trump-travel-ban

consider

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/10/us/

10scotus.html

case

https://www.npr.org/2021/12/01/

1060508566/roe-v-wade-arguments-abortion-supreme-court-case-mississippi-law

https://www.npr.org/2021/11/03/

1049380749/gun-rights-supreme-court-arguments-new-york

http://www.npr.org/2017/10/03/

552904504/this-supreme-court-case-could-radically-reshape-politics

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/06/

opinion/sunday/the-supreme-court-returns.html

case> Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization

https://www.npr.org/2021/12/01/

1060508566/roe-v-wade-arguments-abortion-supreme-court-case-mississippi-law

landmark Supreme Court case

https://www.npr.org/2018/01/03/

571647322/students-identify-with-50-year-old-supreme-court-case

take up cases

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/08/us/

supreme-court-agrees-to-hear-two-cases-on-gay-marriage.html

agree to take

up a case

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/06/26/

534417186/high-court-to-hear-case-of-cake-shop-that-refused-to-bake-for-same-sex-wedding

hear cases

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/06/26/

533934989/supreme-court-will-hear-cases-on-president-trumps-travel-ban

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/24/us/

justices-to-hear-case-on-execution-drugs.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/06/

opinion/sunday/the-supreme-court-returns.html

agree to

hear arguments

over immigration cases

that were filed in federal courts

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/06/26/

533934989/supreme-court-will-hear-cases-on-president-trumps-travel-ban

hear arguments

https://www.npr.org/2021/12/01/

1060508566/roe-v-wade-arguments-abortion-supreme-court-case-mississippi-law

https://www.npr.org/2021/11/08/

1052567444/supreme-court-to-hear-arguments-on-fbis-surveillance-of-mosques

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/02/

opinion/its-not-citizens-united.html

hear the case of N

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/10/28/

499793588/supreme-court-will-hear-case-on-bathroom-rules-for-transgender-students

re-hear

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/06/26/

533988735/supreme-court-will-re-hear-immigrant-indefinite-detention-case

weigh

http://www.npr.org/2017/10/06/

555862822/no-class-action-supreme-court-weighs-whether-workers-must-face-arbitrations-alon

http://www.npr.org/2016/04/18/

474376140/supreme-court-weighs-obamas-executive-action-on-immigration

nix /

reject /

refuse to hear

death penalty > refuse to hear an

appeal brought by N

https://www.npr.org/2021/05/24/

999782039/inmate-who-sought-execution-by-firing-squad-loses-supreme-court-appeal

decline to take up a case

https://www.npr.org/2018/02/26/

588813001/supreme-court-declines-to-take-up-key-daca-case-for-now

decline to

hear an appeal from N

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/05/us/

justices-decide-not-to-hear-oklahoma-abortion-case.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/10/us/

10sniper.html

turn away an emergency application /

reject bid to V

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/20/us/

supreme-court-rejects-bid-to-block-texas-abortion-law.html

dismiss two

lawsuits

send

a case back to a lower court

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/06/26/

533968647/supreme-court-sends-cross-border-shooting-case-back-to-lower-court

The Supreme Court of the United

States

By Mikki K. Harris

USA TODAY

Court takes harder stance on

abortion

Analysis by Joan Biskupic USA

TODAY 18.4.2007

https://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/washington/2007-04-18-

partial-birth-ruling_N.htm - broken link

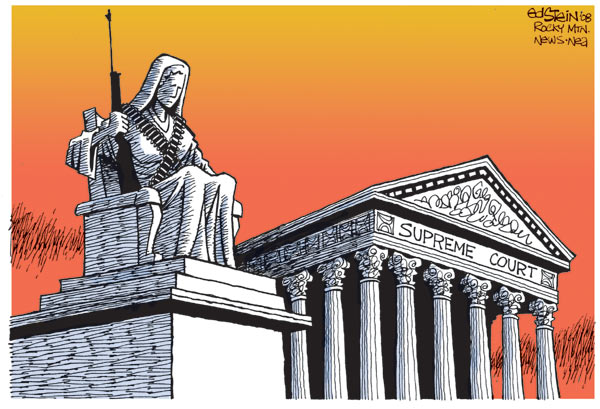

Ed Stein

political cartoon

The Rocky Mountain News, Colorado

Cagle

2.7.2008

Related

http://www.usatoday.com/news/washington/2008-06-26-scotus-guns_N.htm -

broken link

United States Constitution

the 10th Amendment limits federal

power

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/19/us/

19bar.html

law

law / legislation

a piece of legislation

constitutionality

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/27/us/oklahoma-

asks-justices-to-delay-executions.html

constitutional

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/30/

opinion/a-divided-court-on-three-big-rulings.html

constitutional rights

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/25/us/

federal-judge-finds-violations-of-rights-by-sheriff-joe-arpaio.html

Miranda rights

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/21/us/

a-debate-over-delaying-suspects-miranda-rights.html

unconstitutional

http://www.npr.org/2016/01/12/

462821735/supreme-court-strikes-down-floridas-death-penalty-system

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/07/

opinion/is-the-death-penalty-unconstitutional.html

clemency / the power of executive clemency / clemency power

(a) constitutional provision

(...)

gives the president

virtually unlimited authority

to

grant clemency

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/10/opinion/mercy-in-the-justice-system.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/24/

opinion/reviving-clemency-serving-justice.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/10/

opinion/mercy-in-the-justice-system.html

https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2013/12/19/

statement-president-clemency

prohibit

legalize

vote

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/22/

us/politics/transgender-ban-military-supreme-court.html

tie vote

a tie

vote

automatically affirms

the lower court’s ruling

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/26/

opinion/sunday/the-supreme-courts-silent-failure-on-immigration.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/26/

opinion/sunday/the-supreme-courts-silent-failure-on-immigration.html

vote

pass

approve

approved

enact

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/27/

opinion/l27arizona.html

enacted

Ohio’s incest law

lawmakers

Library of Congress > American Memory

A Century of Lawmaking For a New Nation

U.S. Congressional Documents and

Debates

https://www.loc.gov/collections/

century-of-lawmaking/about-this-collection/

Law Library of Congress

https://www.loc.gov/law/index.php

the

marshal of the U.S. Supreme Court / The Supreme Court marshal

https://www.npr.org/2022/07/03/

1109614708/protests-at-homes-of-supreme-court-justices

State lawmakers

New Jersey lawmakers

state law

Rhode Island voting rights law

ban

declare the

Partial Birth Abortion Ban Act unconstitutional

Lloyd Bentsen

Corpus of news articles

USA > Law, Constitution, Regulation >

High Court / U.S. Supreme court

Supreme Court Strikes Down

Texas Abortion Restrictions

JUNE 27, 2016

The New York Times

By ADAM LIPTAK

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court on Monday struck down parts of a restrictive

Texas law that could have reduced the number of abortion clinics in the state to

about 10 from what was once a high of roughly 40.

The 5-to-3 decision was the court’s most sweeping statement on abortion rights

since Planned Parenthood v. Casey in 1992. It applied a skeptical and exacting

version of that decision’s “undue burden” standard to find that the restrictions

in Texas went too far.

The decision on Monday means that similar restrictions in other states are most

likely also unconstitutional, and it imperils many other kinds of restrictions

on abortion.

Justice Stephen G. Breyer wrote the majority opinion, joined by Justices Anthony

M. Kennedy, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan. Chief Justice

John G. Roberts Jr. and Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel A. Alito Jr.

dissented.

The decision concerned two parts of a Texas law that imposed strict requirements

on abortion providers. It was passed by the Republican-dominated Texas

Legislature and signed into law in July 2013 by Rick Perry, the governor at the

time.

One part of the law requires all clinics in the state to meet the standards for

ambulatory surgical centers, including regulations concerning buildings,

equipment and staffing. The other requires doctors performing abortions to have

admitting privileges at a nearby hospital.

“We conclude,” Justice Breyer wrote, “that neither of these provisions offers

medical benefits sufficient to justify the burdens upon access that each

imposes. Each places a substantial obstacle in the path of women seeking a

previability abortion, each constitutes an undue burden on abortion access, and

each violates the federal Constitution.”

Last June, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, in New

Orleans, largely upheld the contested provisions of the Texas law, saying it had

to accept lawmakers’ assertions about the health benefits of abortion

restrictions. The appeals court ruled that the law, with minor exceptions, did

not place an undue burden on the right to abortion.

Justice Breyer said the appeals court’s approach was at odds with the proper

application of the undue-burden standard. The Casey decision, he said, “requires

that courts consider the burdens a law imposes on abortion access together with

the benefits those laws confer.”

In dissent, Justice Thomas said the majority opinion “reimagines the

undue-burden standard,” creating a “benefits-and-burdens balancing test.” He

said courts should resolve conflicting positions by deferring to legislatures.

“Today’s opinion,” Justice Thomas wrote, “does resemble Casey in one respect:

After disregarding significant aspects of the court’s prior jurisprudence, the

majority applies the undue-burden standard in a way that will surely mystify

lower courts for years to come.”

The majority opinion considered whether the claimed benefits of the restrictions

outweighed the burdens they placed on a constitutional right. Justice Breyer

wrote that there was no evidence that the admitting-privileges requirement

“would have helped even one woman obtain better treatment.”

At the same time, he wrote, there was good evidence that the

admitting-privileges requirement caused the number of abortion clinics in Texas

to drop from 40 to 20.

In a second dissent, Justice Alito, joined by Chief Justice Roberts and Justice

Thomas, said the causal link between the law and the closures was unproven.

Withdrawal of state funds, a decline in the demand for abortions and doctors’

retirements may have played a role, Justice Alito wrote.

Justice Breyer wrote that the requirement that abortion clinics meet the

demanding and elaborate standards for ambulatory surgical centers also did more

harm than good.

“Abortions taking place in an abortion facility are safe — indeed, safer than

numerous procedures that take place outside hospitals and to which Texas does

not apply its surgical-center requirements,” he wrote, reviewing the evidence.

“Nationwide, childbirth is 14 times more likely than abortion to result in

death, but Texas law allows a midwife to oversee childbirth in the patient’s own

home.”

In dissent, Justice Alito said there was good reason to think that the

restrictions were meant to and did protect women. “The law was one of many

enacted by states in the wake of the Kermit Gosnell scandal, in which a

physician who ran an abortion clinic in Philadelphia was convicted for the first

degree murder of three infants who were born alive and for the manslaughter of a

patient,” Justice Alito wrote.

Justice Breyer acknowledged that “Gosnell’s behavior was terribly wrong.”

“But,” he added, “there is no reason to believe that an extra layer of

regulation would have affected that behavior.”

The clinics challenging the law said it has already caused about half of the

state’s 41 abortion clinics to close. If the contested provisions had taken full

effect, they said, the number of clinics would again be cut in half.

The remaining Texas clinics would have been clustered in four metropolitan

areas: Austin, Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston and San Antonio. “None is located west

or south of San Antonio, a vast geographic area that is larger than California,”

a brief for the clinics said. An appeals court did allow a partial exemption for

a clinic in McAllen, the brief added, but “imposed limitations on the clinic’s

operational capacity that would severely restrict its ability to provide

abortions.”

Justice Breyer, announcing the majority opinion in the hushed Supreme Court

chamber, said that the requirements in the Texas statute “are not consistent

with the constitutional standard set forth in Casey,” and were, therefore, both

unconstitutional.

Justice Alito responded with an extended dissent from the bench, a sign of deep

disagreement. “We are supposed to be a neutral court of law,” he said, outlining

what he conceded were “dry and technical” points of legal doctrine he argued

should have precluded the petitioners from presenting the challenge in the first

place. “There is no justification for treating abortion cases differently from

other cases.”

Julie Hirschfeld Davis contributed reporting.

Follow The New York Times’s politics

and Washington coverage on Facebook and

Twitter,

and sign up for the First Draft politics newsletter.

Supreme Court Strikes Down Texas Abortion Restrictions,

NYT,

June 27, 2016,

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/28/

us/supreme-court-texas-abortion.html

Supreme

Court

Set to

Decide Marriage Rights

for Gay

Couples Nationwide

JAN. 16, 2015

The New York

Times

By ADAM LIPTAK

WASHINGTON —

The Supreme Court on Friday agreed to decide whether all 50 states must allow

gay and lesbian couples to marry, positioning it to resolve one of the great

civil rights questions in a generation before its current term ends in June.

The decision came just months after the justices ducked the issue, refusing in

October to hear appeals from rulings allowing same-sex marriage in five states.

That decision, which was considered a major surprise, delivered a tacit victory

for gay rights, immediately expanding the number of states with same-sex

marriage to 24, along with the District of Columbia, up from 19.

Largely as a consequence of the Supreme Court’s decision not to act, the number

of states allowing same-sex marriage has since grown to 36, and more than 70

percent of Americans live in places where gay couples can marry.

The cases the Supreme Court agreed to hear on Friday were brought by some 15

same-sex couples in four states. The plaintiffs said they have a fundamental

right to marry and to be treated as opposite-sex couples are, adding that bans

they challenged demeaned their dignity, imposed countless practical difficulties

and inflicted particular harm on their children.

The pace of change on same-sex marriage, in both popular opinion and in the

courts, has no parallel in the nation’s history.

Gay rights advocates hailed the court’s move on Friday as one of the final steps

in a decades-long journey toward equal treatment, and they expressed confidence

they would prevail.

“We are finally within sight of the day when same-sex couples across the country

will be able to share equally in the joys, protections and responsibilities of

marriage,” said Jon W. Davidson, the legal director of Lambda Legal.

Supporters of traditional marriage said the Supreme Court now has a chance to

return the issue to voters and legislators.

“Lower court judges have robbed millions of people of their voice and vote on

society’s most fundamental relationship — marriage,” said Tony Perkins, the

president of the Family Research Council, a conservative policy and lobbying

group. “There is nothing in the Constitution that empowers the courts to silence

the people and impose a nationwide redefinition of marriage.”

The Supreme Court’s lack of action in October and its last three major gay

rights rulings suggest that the court will rule in favor of same-sex marriage.

But the court also has a history of caution in this area.

It agreed once before to hear a constitutional challenge to a same-sex marriage

ban, in 2012 in a case called Hollingsworth v. Perry that involved California’s

Proposition 8. At the time, nine states and the District of Columbia allowed

same-sex couples to marry.

When the court’s ruling arrived in June 2013, the justices ducked, with a

majority saying that the case was not properly before them, and none of them

expressing a view on the ultimate question of whether the Constitution requires

states to allow same-sex marriage.

But a second decision the same day, in United States v. Windsor, provided the

movement for same-sex marriage with what turned out to be a powerful tailwind.

The decision struck down the part of the Defense of Marriage Act that barred

federal benefits for same-sex couples married in states that allowed such

unions.

The Windsor decision was based partly on federalism grounds, with Justice

Anthony M. Kennedy’s majority opinion stressing that state decisions on how to

treat marriages deserved respect. But lower courts focused on other parts of his

opinion, ones that emphasized the dignity of gay relationships and the harm that

families of gay couples suffered from bans on same-sex marriage. In a remarkable

and largely unbroken line of more than 40 decisions, state and federal courts

relied on the Windsor decision to rule in favor of same-sex marriage.

The most important exception was a decision in November from a divided

three-judge panel of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit,

in Cincinnati. Writing for the majority, Judge Jeffrey S. Sutton said that

voters and legislators, not judges, should decide the issue.

That decision created a split among the federal appeals courts, a criterion that

the Supreme Court often looks to in deciding whether to hear a case. That

criterion had been missing in October.

The Sixth Circuit’s decision upheld bans on same-sex marriage in Kentucky,

Michigan, Ohio and Tennessee. The Supreme Court agreed to hear petitions seeking

review from plaintiffs challenging those bans in each state.

The court said it will hear two and a half hours of argument, probably in the

last week of April. The first 90 minutes will be devoted to the question of

whether the Constitution requires states “to license a marriage between two

people of the same sex.”

The last hour will concern a question that will be moot if the answer to the

first one is yes: whether states must “recognize a marriage between two people

of the same sex when their marriage was lawfully licensed and performed out of

state.”

The court consolidated the four petitions, not all of which had addressed both

questions.

Two cases — Obergefell v. Hodges, No. 14-556, from Ohio, and Tanco v. Haslam,

No. 14-562, from Tennessee — challenged state laws barring the recognition of

same-sex marriages performed elsewhere.

“Ohio does not contest the validity of their out-of-state marriages,” the

plaintiffs seeking to overturn the ban wrote in their brief seeking Supreme

Court review. “It simply refuses to recognize them.”

State officials in Ohio had urged the justices to hear the case. “The present

status quo is unsustainable,” they said. “The country deserves a nationwide

answer to the question — one way or the other.”

Gov. Bill Haslam of Tennessee, a Republican, took a different approach from

those of officials in the other states whose cases the Supreme Court agreed to

decide. He did what litigants who have won in the lower court typically do: He

urged the justices to decline to hear the case.

The Michigan case, DeBoer v. Snyder, No. 14-571, was brought by April DeBoer and

Jayne Rowse, two nurses. They sued to challenge the state’s ban on same-sex

marriage.

In urging the Supreme Court to hear their case, they asked the justices to do

away with “the significant legal burdens and detriments imposed by denying

marriage to same-sex couples, as well as the dignity and emotional well-being of

the couples and any children they may have.”

Gov. Rick Snyder, a Republican, joined the plaintiffs in urging the Supreme

Court to hear the case.

The Kentucky case, Bourke v. Beshear, No. 14-574, was brought by two sets of

plaintiffs. The first group included four same-sex couples who had married in

other states and who sought recognition of their unions. The second group, two

couples, sought the right to marry in Kentucky.

In his response to the petition in the Supreme Court, Gov. Steven L. Beshear, a

Democrat, said he had a duty to enforce the state’s laws. But he agreed that the

Supreme Court should settle the matter and “resolve the issues creating the

legal chaos that has resulted since Windsor.”

A version of this article appears in print

on January 17, 2015,

on page A1 of

the New York edition

with the headline:

Justices to Decide Marriage Rights for

Gay Couples.

Supreme Court

Set to Decide Marriage Rights for Gay Couples Nationwide,

NYT,

JAN 15, 2015,

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/17/

us/supreme-court-to-decide-whether-gays-nationwide-can-marry.html

Personal

Guns

and the Second Amendment

December

17, 2012

The New York Times

When the

Supreme Court struck down a ban on handguns by the District of Columbia in 2008,

ruling that there is a constitutional right to keep a loaded handgun at home for

self-defense, the decision was enormously controversial in the legal world. But

the court’s conclusion has generally been accepted in the real world because the

ruling was in tune with popular opinion — favoring Americans’ rights to own guns

but also control of gun ownership.

The text of the Second Amendment creates no right to private possession of guns,

but Justice Antonin Scalia found one in legal history for himself and the other

four conservatives. He said the right is not outmoded even “in a society where

our standing army is the pride of our Nation, where well-trained police forces

provide personal security, and where gun violence is a serious problem.”

It is not just liberals who have lambasted the ruling, but some prominent

conservatives like Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. The majority, he wrote, “read an ambiguous

constitutional provision as creating a substantive right that the Court had

never acknowledged in the more than two hundred years since the amendment’s

enactment. The majority then used that same right to strike down a law passed by

elected officials acting, rightly or wrongly, to preserve the safety of the

citizenry.” He said the court undermined “conservative jurisprudence.”

In the real world, however, criticism has abated in part because the majority

opinion was strikingly respectful of commonplace gun regulations. “Like most

rights,” Justice Scalia said, “the right secured by the Second Amendment is not

unlimited.”

And: “nothing in our opinion should be taken to cast doubt on longstanding

prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, or

laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and

government buildings, or laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the

commercial sale of arms. We also recognize another important limitation on the

right to keep and carry arms” —“prohibiting the carrying of ‘dangerous and

unusual weapons.’ ”

Justice Scalia does not say how federal courts should evaluate such regulations

and the Supreme Court may need to return to this issue soon, to resolve a

substantial disagreement that has arisen in federal appeals courts.

Does the court’s 4-year-old ruling imply “a right to carry a loaded gun outside

the home”? That is what the Seventh Circuit appellate court concluded last week

in striking down an Illinois law that prohibited most people from carrying a

loaded weapon in public.

Or does the Supreme Court’s ruling on handguns support the view that public

interest in safety outweighs an individual’s interest in self-defense because

gun rights are more limited outside the home? That is what the Second Circuit

found last month in upholding a New York State law limiting handgun possession

in public to people who can show a threat to their own safety.

Where “gun violence is a serious problem,” as Justice Scalia said it is in the

United States, the courts must be very cautious about extending the individual

right to own a gun. The justice’s opinion made that clear.

Read related editorials on gun control:

rethinking guns and legislation

abroad.

Personal Guns and the Second Amendment,

NYT,

17.12.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/18/

opinion/the-gun-challenge-second-amendment.html

The Human Cost

of the Second Amendment

September 26, 2012

8:30 pm

Opinionator -

A Gathering of Opinion From Around the Web

By THERESA BROWN

Wisconsin, Aurora, Virginia Tech, Columbine. We all know these

place names and what happened there. By the time this column appears, there may

well be a new locale to add to the list. Such is the state of enabled and

murderous mayhem in the United States.

With the hope of presenting the issue of guns in America in a novel way, I'm

going to look at it from an unusual vantage point: the eyes of a nurse. By that

I mean looking at guns in America in terms of the suffering they cause, because

to really understand the human cost of guns in the United States we need to

focus on gun-related pain and death.

Every day 80 Americans die from gunshots and an additional 120 are wounded,

according to a 2006 article in The Journal of Policy Analysis and Management.

Those 80 Americans left their homes in the morning and went to work, or to

school, or to a movie, or for a walk in their own neighborhood, and never

returned. Whether they were dead on arrival or died later on in the hospital, 80

people's normal day ended on a slab in the morgue, and there's nothing any of us

can do to get those people back.

In a way that few others do, I became aware early on that nurses deal with death

on a daily basis. The first unretouched dead bodies I ever saw were the two

cadavers we studied in anatomy lab. One man, one woman, both donated their

bodies for dissection, and I learned amazing things from them: the sponginess of

lung tissue, the surprising lightness of a human heart, the fabulous intricacy

of veins, arteries, tendons and nerves that keep all of us moving and alive.

I also learned something I thought I already knew: death is scary. I expected my

focus in the lab to be on acquiring knowledge, and it was, but my feelings about

these cadavers intruded also. I had nightmares. The sound of bones being sawed

and snapped was excruciating the day our teaching assistant broke the ribs of

one of them to extract a heart. Some days the smell was so overwhelming I wanted

to run from the lab. Death is the only part of life that is really final, and I

learned about the awesomeness of finality during my 12 weeks with those two very

dead people.

Of course, in hospitals, death and suffering are what nurses and doctors

struggle against. Our job is to restore people to health and wholeness, or at

the very least, to keep them alive. That's an obvious aim on the oncology floor

where I work, but nowhere is the medical goal of maintaining life more

immediately urgent than in trauma centers and intensive-care units. In those

wards, patients often arrive teetering on the border between life and death, and

the medical teams that receive them have fleeting moments in which to act.

The focus on preserving life and alleviating suffering, so evident in the

hospital, contrasts strikingly with its stubborn disregard when applied to lives

ended by Americans lawfully armed as if going into combat. The deaths from guns

are as disturbing, and as final, as the cadavers I studied in anatomy lab, but

the talk we hear from the gun lobby is about freedom and rights, not life and

death.

Gun advocates say that guns don't kill people, people kill people. The truth,

though, is that people with guns kill people, often very efficiently, as we saw

so clearly and so often this summer. And while there can be no argument that the

right to bear arms is written into the Constitution, we cannot keep pretending

that this right is somehow without limit, even as we place reasonable limits on

arguably more valuable rights like the freedom of speech and due process.

No one argues that it should be legal to shout "fire" in a crowded theater; we

accept this limit on our right to speak freely because of its obvious real-world

consequences. Likewise, we need to stop talking about gun rights in America as

if they have no wrenching real-world effects when every day 80 Americans, their

friends, families and loved ones, learn they obviously and tragically do.

Many victims never stand a chance against a dangerously armed assailant, and

there's scant evidence that being armed themselves would help. Those bodies skip

the hospital and go straight to the morgue. The lucky ones, the survivors - the

120 wounded per day - get hustled to trauma centers and then intensive care

units to, if possible, be healed. Many of them never fully recover.

A trauma nurse I know told me she always looked at people's shoes when they lay

on gurneys in the emergency department. It struck her that life had still been

normal when that patient put them on in the morning. Whether they laced up

Nikes, pulled on snow boots or slid feet into stiletto heels, the shoes became a

relic of the ordinariness of the patient's life, before it turned savage.

So I have a request for proponents of unlimited access to guns. Spend some time

in a trauma center and see the victims of gun violence - the lucky survivors -

as they come in bloody and terrified. Understand that our country's blind

embrace of gun rights made this violent tableau possible, and that it's playing

out each day in hospitals and morgues all over the country.

Before leaving, make sure to look at the patients' shoes. Remember that at the

start of the day, before being attacked by a person with a gun, that patient

lying on a stretcher writhing helplessly in pain was still whole.

Theresa Brown is an oncology nurse and the author

of "Critical Care: A New Nurse Faces Death, Life,

and Everything in

Between."

The Human Cost of the Second Amendment,

NYT,

26.9.2012,

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/09/26/

the-human-cost-of-the-second-amendment/

Embarrassed by Bad Laws

April 16,

2012

The New York Times

A year ago,

few people outside the world of state legislatures had heard of the American

Legislative Exchange Council, a four-decade-old organization run by right-wing

activists and financed by business leaders. The group writes prototypes of state

laws to promote corporate and conservative interests and spreads them from one

state capital to another.

The council, known as ALEC, has since become better known, with news

organizations alerting the public to the damage it has caused: voter ID laws

that marginalize minorities and the elderly, antiunion bills that hurt the

middle class and the dismantling of protective environmental regulations.

Now it’s clear that ALEC, along with the National Rifle Association, also played

a big role in the passage of the “Stand Your Ground” self-defense laws around

the country. The original statute, passed in Florida in 2005, was a factor in

the local police’s failure to arrest the shooter of a Florida teenager named

Trayvon Martin immediately after his killing in February.

That was apparently the last straw for several prominent corporations that had

been financial supporters of ALEC. In recent weeks, McDonald’s, Wendy’s, Intuit,

Mars, Kraft Foods, Coca-Cola and PepsiCo have stopped supporting the group,

responding to pressure from activists and consumers who have formed a

grass-roots counterweight to corporate treasuries. That pressure is likely to

continue as long as state lawmakers are more responsive to the needs of big

donors than the public interest.

The N.R.A. pushed Florida’s Stand Your Ground law through the State Legislature

over the objections of law enforcement groups, and it was signed by Gov. Jeb

Bush. It allows people to attack a perceived assailant if they believe they are

in imminent danger, without having to retreat. John Timoney, formerly the Miami

police chief, recently called the law a “recipe for disaster,” and he said that

he and other police chiefs had correctly predicted it would lead to more violent

road-rage incidents and drug killings. Indeed, “justifiable homicides” in

Florida have tripled since 2005.

Nonetheless, ALEC — which counts the N.R.A. as a longtime and generous member —

quickly picked up on the Florida law and made it one of its priorities,

distributing it to legislators across the country. Seven years later, 24 other

states now have similar laws, thanks to ALEC’s reach, and similar bills have

been introduced in several other states, including New York.

The corporations abandoning ALEC aren’t explicitly citing the Stand Your Ground

statutes as the reason for their decision. But many joined the group for

narrower reasons, like fighting taxes on soda or snacks, and clearly have little

interest in voter ID requirements or the N.R.A.’s vision of a society where

anyone can fire a concealed weapon at the slightest hint of a threat.

In a statement issued on Wednesday, ALEC bemoaned the opposition it is facing

and claimed it is only interested in job creation, government accountability and

pro-business policies. It makes no mention of its role in pushing a law that

police departments believe is increasing gun violence and deaths. That’s

probably because big business is beginning to realize the Stand Your Ground laws

are indefensible.

Embarrassed by Bad Laws, NYT, 16.4.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/17/opinion/embarrassed-by-bad-laws.html

Is

Religion Above the Law?

October 17,

2011

9:00 pm

The New York Times

By STANLEY FISH

Stanley Fish on education, law and society.

The

religion clause case recently argued before the Supreme Court — Hosanna-Tabor v.

EEOC — centers on the “ministerial exception,” the doctrine (elaborated over the

last 40 years) that exempts religious associations from complying with neutral,

generally applicable laws in some, but not all, circumstances.

In 2005 Cheryl Perich, a teacher in the Hosanna-Tabor Lutheran Evangelical

School, returned from an extended sick leave (she had been diagnosed with

narcolepsy) to find that her services were no longer wanted. She declined to

resign as requested, and after a resolution satisfactory to her was not

forthcoming she filed a disability discrimination suit. The church responded by

terminating her as a teacher, alleging that its reason was theological, not

retaliatory. The Missouri synod, the church explained, requires its adherents to

resolve disputes rather than bring suit in civil court; in failing to follow

this rule, Perich had transgressed a core Lutheran belief.

The church further argued that as a “commissioned minister” Perich fell under

the ministerial exception even though the bulk of her time was spent teaching

secular subjects. Perich (through her attorneys) replied that her duties were

not primarily religious, and that the assertion of a doctrinal violation was an

afterthought devised to serve as a pretext for an act of retaliation in response

to her having gone to the courts in an effort to secure her rights.

So the issues are, first, was she a minister in the sense that would bring her

under the exception (in which case the state could not intervene to protect

her), and, second, was the doctrine the church invoked as the reason for its

action truly central to its faith? (There are other issues in play but, as we

shall see, two are more than enough.)

The most perspicuous example of a ministerial exception is the Catholic church’s

limitation of membership in the priesthood to males. If a university were to

have a rule that only men could serve as professors, it would be vulnerable to a

suit brought under the anti-discrimination provisions of Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964. The difference (or so it has been asserted) is that there is

no relationship between professorial skills and gender — a woman can perform the

duties of a teacher of history or chemistry as well as a man — while the

tradition of an all-male priesthood is rooted in religious doctrine. So the

university would be engaged in discrimination pure and simple, whereas the

church’s discrimination is a function of its belief that the all-male priesthood

was initiated by Christ in his choice of the apostles.

Were the state to intervene and declare the tradition of an all-male priesthood

and the doctrine underlying it unconstitutional, it would be forcing the church

to conform to secular norms in violation both of the free exercise clause (the

right of a religion to be governed by its own tenets would be curtailed) and the

establishment clause (the state would in effect have taken over the management

of the church by dictating its hiring practices). (I am rehearsing, not

endorsing, these arguments.)

This clear-cut example — to which both sides in Hosanna-Tabor v. EEOC refer

frequently — may be the only one (and it is only clear-cut because it has behind

it 2,000 years of history). For the question quickly becomes one of boundaries —

how far does the ministerial exception extend? To whom does it apply? Not only

are there no answers to such questions, it is not obvious who is empowered to

ask them.

If the ministerial exemption is to have any bite, there must be a way of

distinguishing employees central to a religious association’s core activities

from employees who play only a supporting role (the example always given is

janitors). But if the line marking the distinction is drawn by the state, the

state is setting itself up as the arbiter of ecclesiastical organization and

thus falling afoul of the establishment clause. And if the line is drawn by the

religious association, the religious association is being granted the power to

deprive as many of its employees as it likes of the constitutional protections

supposedly afforded to every citizen. It is these equally unpalatable

alternatives — this Scylla and Charybdis — that the justices find themselves

between in oral argument. What a mess!

It is tempting to bypass the mess by getting rid of the ministerial exception

altogether and demanding that churches, synagogues and mosques obey the law just

as everyone else does. But that draconian solution would imply that we get rid

of the religion clause as well; for it would amount to saying that religion

isn’t special, and both sides of the clause insist that it is. The free-exercise

clause tells us that that religion is especially favored and the establishment

clause tells us that it is especially feared (the state should avoid

entanglement with that stuff). How do you honor the claims of free exercise

without bumping up against the establishment clause by allowing exceptions to

laws that everyone else must follow?

The difficulty is sometimes finessed by cabining free exercise in the private

sphere. Free exercise, it is said, is fine as long as its scope is limited to

the expression and profession of belief; but once it crosses over into actions

the state has a duty to regulate, free exercise must give way to the authority

of fair and neutral laws. (This is the holding of a line of cases from Reynolds

v. United States [1878] to Employment Division v. Smith [1990].)

This cutting of the joint works fine for a religion that places minimal burdens

on its adherents and asks only that they attend to the personal relationship

between them and their God. But what about religions that expand the area of

faith to include rites the faithful must celebrate and worldly actions they are

expected to perform? What about religions that refuse to recognize, and even

consider impious, the distinction between the private and the public spheres?

Can the state step in and say, “No, you’re wrong; that practice you’re worried

about isn’t really essential to your faith; give it up so that a system of laws

put in place for everyone isn’t destroyed by exceptions.” Doesn’t society,

Justice Sonia Sotomayor asked at oral argument, “have a right at some point to

say certain conduct is unacceptable, even if religious?”

The question is, at what point? And who gets to decide when that point has been

reached? Indeed there is a question even more basic (and equally unanswerable

except by fiat): who gets to say whether a “certain conduct” is religious and

centrally so? A resolution of the Hosanna-Tabor case, Justice Samuel Alito

observes, “depends on how central a teaching of Lutheranism” the injunction

against “suing in a civil tribunal” really is. Before we can decide (he

continues) whether the church’s asserted reason for terminating Perich is a

pretext, we must determine whether this is in fact “a central tenet of

Lutheranism.” And if we decide that it isn’t, wouldn’t we be “making a judgment

about the relative importance of the Catholic doctrine that only males can be

ordained as priests and the Lutheran doctrine that a Lutheran should not sue the

church in civil courts?” And what authorizes the Court to do that in opposition

to what the churches themselves say?

The same dilemma attends the other vexed question. How, wonders Chief Justice

John Roberts, “do we decide who’s covered by the ministerial exception?” By

getting to “the heart of the ministerial exception,” answers Douglas Laycock,

speaking for the church. But that is simply to relocate the problem in a phrase

that itself demands explication. Who’s to say where the heart is? In some

churches, Justice Anthony Kennedy observes, there aren’t “full time ministers at

all; they’re all ministers.” So does everyone fall under the exception and can a

non-hierarchical church simply declare that none of its members can seek redress

for acts of discrimination because they’re all ministers? Just before the oral

argument concludes, Justice Sotomayor is still awaiting clarification: “So

define minister for me again?”

She will be waiting forever. There is no way out of these puzzles, and that is

exactly the conclusion Justice Stephen Breyer reaches: “I just can’t see a way …

of getting out of the whole thing.” Justice Alito points to the absurdity of

calling in expert witnesses to determine the truth of disputed matters of

religion, but, he asks, “How are we going to avoid that? I just don’t see it.”

Later he concludes that “you just cannot get away from evaluating religious

issues,” which is of course exactly what the courts are not supposed to be

doing.

So how will the case turn out? Clearly none of the justices wishes to pronounce

as a theologian. And just as clearly none of them is happy with the prospect of

a ministerial exception without defined limits. Breyer gestures in the direction

of a solution that avoids the hard questions. Grant the Church the core doctrine

it cites and inquire into whether Perich was given adequate notice of it. If she

was, she loses; if she wasn’t, she wins. But no one will be satisfied with that

maneuver, which will itself raise a host of new unanswerable questions in place

of the questions supposedly avoided. All these questions were explored by John

Locke at length in his “Letter Concerning Toleration” (1689), and at one point

Locke gives voice to a weariness we might echo today: Would that “this business

of religion were left alone.” But as long as there is a religion clause, that’s

not an option.

Is Religion Above the Law?, NYT, 17.10.2011,

https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/10/17/

is-religion-above-the-law/

Davis Is Executed in Georgia

September 21, 2011

The New York Times

By KIM SEVERSON

JACKSON, Ga. — Proclaiming his innocence, Troy Davis was put

to death by lethal injection on Wednesday night, his life — and the hopes of

supporters worldwide — prolonged by several hours while the Supreme Court

reviewed but then declined to act on a petition from his lawyers to stay the

execution.

Mr. Davis, 42, who was convicted of murdering a Savannah police officer 22 years

ago, entered the death chamber shortly before 11 p.m., four hours after the

scheduled time. He died at 11:08.

This final chapter before his execution had become an international symbol of

the battle over the death penalty and racial imbalance in the justice system.

“It harkens back to some ugly days in the history of this state,” said the Rev.

Raphael Warnock of Ebenezer Baptist Church, who visited Mr. Davis on Monday.

Mr. Davis remained defiant at the end, according to reporters who witnessed his

death. He looked directly at the members of the family of Mark MacPhail, the

officer he was convicted of killing, and told them they had the wrong man.

“I did not personally kill your son, father, brother,” he said. “All I can ask

is that you look deeper into this case so you really can finally see the truth.”

He then told his supporters and family to “keep the faith” and said to prison

personnel, “May God have mercy on your souls; may God bless your souls.”

One of the witnesses, a radio reporter from WSB in Atlanta, said it appeared

that the MacPhail family “seemed to get some satisfaction” from the execution.

For Mr. Davis’s family and other supporters gathered in front of the prison, the

final hours were mixed with hope, tears and exhaustion. The crowd was buoyed by

the Supreme Court’s involvement, but crushed when the justices issued their

one-sentence refusal to consider a stay.

When the news of his death came, the family left quietly and the 500 or so

supporters began to pack up and leave their position across the state highway

from the prison entrance. Mr. Davis’s body was driven out of the grounds about

midnight.

During the evening, a dozen supporters of the death penalty, including people

who knew the MacPhail family sat quietly, separated from the Davises and their

supporters by a stretch of lawn and rope barriers.

The appeal to the Supreme Court was one of several last-ditch efforts by Mr.

Davis on Wednesday. Earlier in the day, an official with the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People said that the vote by the

Georgia parole board to deny clemency to Mr. Davis was so close that he hoped

there might be a chance to save him from execution.

The official, Edward O. DuBose, president of the Georgia chapter, said the group

had “very reliable information from the board members directly that the board

was split 3 to 2 on whether to grant clemency.”

“The fact that that kind of division was in the room is even more of a sign that

there is a strong possibility to save Troy’s life,” he said.

The N.A.A.C.P said it had been in contact with the Department of Justice on

Wednesday, in the hope that the federal government would intervene on the basis

of civil rights violations, meaning irregularities in the original investigation

and at the trial.

Earlier in the day, his lawyers had asked the state for another chance to spare

him: a lie detector test.

But the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Parole, which on Tuesday denied Mr.

Davis’s clemency after a daylong hearing on Monday, quickly responded that there

would be no reconsideration of the case, and the polygraph test was abandoned.

Mr. Davis’s supporters also reached out to the prosecutor in the original case

and asked him to persuade the original judge to rescind the death order.

Benjamin Jealous, the president of the N.A.A.C.P, also tried to ask President

Obama for a reprieve.

The Innocence Project, which has had a hand in the exoneration of 17 death-row

inmates through the use of DNA testing, sent a letter to the Chatham County

district attorney, Larry Chisolm, urging him to withdraw the execution warrant

against Mr. Davis.

Mr. Davis was convicted of the 1989 shooting of Officer MacPhail, who was

working a second job as a security guard. A homeless man called for help after a

group that included Mr. Davis began to assault him, according to court

testimony. When Officer MacPhail went to assist him, he was shot in the face and

the heart.

Before Wednesday, Mr. Davis had walked to the brink of execution three times.

His conviction came after testimony by some witnesses who later recanted and on

the scantest of physical evidence, adding fuel to those who rely on the Internet

to rally against executions and to question the validity of eyewitness

identification and of the court system itself.

But for the family of the slain officer and others who believed that two

decades’ worth of legal appeals and Supreme Court intervention was more than

enough to ensure justice, it was not an issue of race but of law.

Inside the prison, Officer MacPhail’s widow, Joan MacPhail-Harris, said calling

Mr. Davis a victim was ludicrous.

“We have lived this for 22 years,” she said on Monday. “We are victims.”

She added: “We have laws in this land so that there is not chaos. We are not

killing Troy because we want to.”

Mr. Davis, who refused a last meal, had been in good spirits and prayerful, said

Wende Gozan Brown, a spokeswoman for Amnesty International, who visited him on

Tuesday. She said he had told her his death was for all the Troy Davises who

came before and after him.

“I will not stop fighting until I’ve taken my last breath,” she recounted him as

saying. “Georgia is prepared to snuff out the life of an innocent man.”

The case has been a slow and convoluted exercise in legal maneuvering and death

penalty politics.

The state parole board granted him a stay in 2007 as he was preparing for his

final hours, saying the execution should not proceed unless its members “are

convinced that there is no doubt as to the guilt of the accused.” The board has

since added three new members.

In 2008, his execution was about 90 minutes away when the Supreme Court stepped

in. Although the court kept Mr. Davis from execution, it later declined to hear

the case.

This time around, the case catapulted into the national consciousness with

record numbers of petitions — more than 630,000 — delivered to the board to stay

the execution, and the list of people asking for clemency included former

President Jimmy Carter, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, 51 members of Congress,

entertainment figures like Cee Lo Green and even some death penalty supporters,

including William S. Sessions, a former F.B.I. director.

Kim Severson reported from Jackson,

and John Schwartz from New York.

Davis Is Executed in

Georgia,

NYT,

21.9.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/22/

us/final-pleas-and-vigils-in-troy-davis-execution.html

The First Amendment, Upside Down

June 27, 2011

The New York Times

The Supreme Court decision striking down public matching funds in Arizona’s

campaign finance system is a serious setback for American democracy. The opinion

written by Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. in Monday’s 5-to-4 decision shows

again the conservative majority’s contempt for campaign finance laws that aim to

provide some balance to the unlimited amounts of money flooding the political

system.

In the Citizens United case, the court ruled that the government may not ban

corporations, unions and other moneyed institutions from spending in political

campaigns. The Arizona decision is a companion to that destructive landmark

ruling. It takes away a vital, innovative way of ensuring that candidates who do

not have unlimited bank accounts can get enough public dollars to compete

effectively.

Arizona’s campaign finance law provided a set amount of money in initial public

support for candidates who opted into its financing system, depending on the

type of election. If a candidate faced a rival who opted out, the state would

match the spending of the privately financed candidate and independent groups

supporting him, up to triple the initial amount. Once that limit is reached, the

publicly financed candidate receives no other public funds and is barred from

using private contributions, no matter how much more the privately financed

candidate spends.

Chief Justice Roberts found that this mechanism “imposes a substantial burden”

on the free speech rights of candidates and independent groups because it

penalized them when their spending triggered additional money for a candidate

who opted into the public program. The court turns the First Amendment on its

head. It denies the actual effect of the Arizona law, which is not to limit

spending but to increase it with public funds. The state program expands

political speech by giving all candidates, not just the wealthy, a chance to run

— while allowing privately financed candidates to spend as much as they want.

Justice Elena Kagan, writing in dissent, dissects the court’s willful

misunderstanding of the result. Rather than a restriction on speech, she says,

the trigger mechanism is a subsidy with the opposite effect: “It subsidizes and

produces more political speech.” Those challenging the law, she wrote, demanded

— and have now won — the right to “quash others’ speech” so they could have “the

field to themselves.” She explained that the matching funds program — unlike a

lump sum grant to candidates — sensibly adjusted the amount disbursed so that it

was neither too little money to attract candidates nor too large a drain on

public coffers.

Arizona’s system was a response to a history of terrible corruption in the

state’s politics. Rather than seeing the law as a way to control corruption, the

court struck it down as a limit on the right of wealthy candidates and

independent groups to speak louder than others.

The ruling left in place other public financing systems without such trigger

provisions, including public financing for presidential elections. It shows,

however, how little the court cares about the interest of citizens in Arizona or

elsewhere in keeping their electoral politics clean.

The First Amendment,

Upside Down,

NYT,

27.6.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/28/opinion/28tue1.html

Supreme

Court Allows Suit

to Force DNA Testing of Evidence

March 7,

2011

The New York Times

By ADAM LIPTAK

WASHINGTON

— The Supreme Court on Monday made it easier for inmates to sue for access to

DNA evidence that could prove their innocence.

The legal issue in the case was tightly focused, and quite preliminary: Was Hank

Skinner, a death row inmate in Texas, entitled to sue a prosecutor there under a

federal civil rights law for refusing to allow testing of DNA evidence in his

case? By a 6-to-3 vote, the court said yes, rejecting a line of lower-court

decisions that had said the only proper procedural route for such challenges was

a petition for habeas corpus.

In her opinion for the majority, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg emphasized how

narrowly the court was ruling. Allowing Mr. Skinner to sue, she said, is not the

same thing as saying he should win his suit.

Justice Ginsburg added that a 2009 decision, District Attorney’s Office v.

Osborne, had severely limited the kinds of claims that prisoners who are seeking

DNA evidence can make. The Osborne decision, Justice Ginsburg wrote, “left slim

room for the prisoner to show that the governing state law denies him procedural

due process.”

The case that was decided on Monday, Skinner v. Switzer, No. 09-9000, arose from

three killings on New Year’s Eve in 1993. Mr. Skinner contends that he was

asleep on a sofa in a vodka-and-codeine haze that night when his girlfriend,

Twila Busby, and her two sons were killed. Mr. Skinner says that an uncle of Ms.

Busby, Robert Donnell, who has since died, was probably the killer.

Prosecutors tested some but not all of the evidence from the crime scene. Some

of the test results pointed toward Mr. Skinner, who never denied that he was

present, but some of the results did not. His trial lawyer, wary of what

additional testing would show, did not ask for it.

In the years since Mr. Skinner was convicted, prosecutors have blocked his

requests to test blood, fingernail scrapings and hair found at the scene. In

their Supreme Court briefs, prosecutors accused Mr. Skinner of playing games

with the system, dragging out his case and seeking to impose unacceptable

burdens on government resources and the victims’ dignity. They added that

testing would be pointless because “no item of evidence exists that would

conclusively prove that Skinner did not commit the murder.”

In 2001, Texas enacted a law allowing post-conviction DNA testing in limited

circumstances. State courts in Texas rejected Mr. Skinner’s requests under the

law on the ground that he was at fault for not having sought testing earlier.

Mr. Skinner then sued in federal court under a federal civil rights law known as

Section 1983, saying that the Texas law violated his right to due process. That

suit was rejected in the lower federal courts on the ground that the proper

vehicle for a challenge was a petition for habeas corpus.

Section 1983 suits are often more attractive to prisoners than habeas petitions

because Congress and the Supreme Court have placed significant barriers in the

path of inmates seeking habeas corpus.

Justice Ginsburg wrote that a Section 1983 suit was available in cases where the