|

Vocapedia >

Life / Health > Old

people > Centenarians

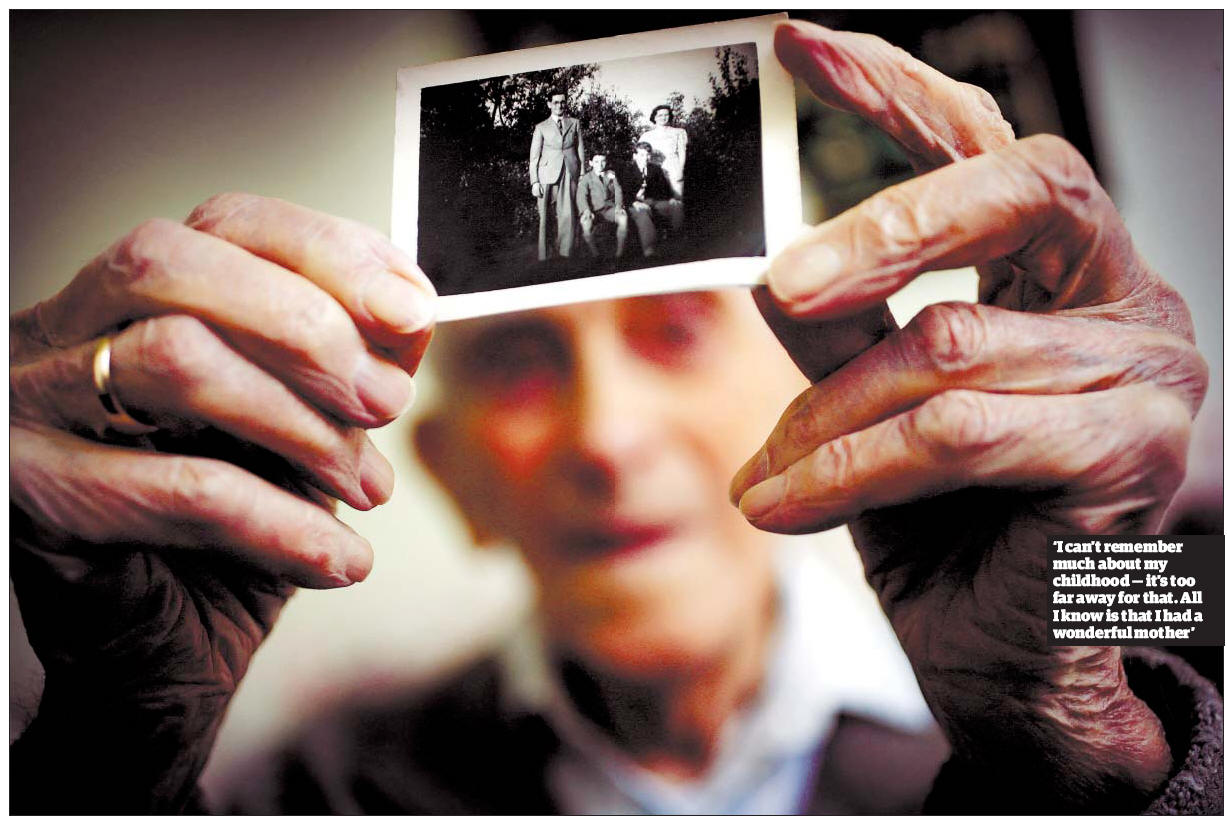

Wilfred Talbot, Bath

The Guardian G2

pp. 12-13

18 January 2006

Life at 100

In the 60s,

fewer than 300 people in Britain

had reached the

age of 100.

Today, there are more than 6,000,

a number expected to swell to 40,000

in three

decades' time.

But what is it like

to have lived a life that spans a century?

Stephen Moss

sought out eight centenarians to ask them

The Guardian G2

Wednesday January 18, 2006

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2006/jan/18/

longtermcare.britishidentityandsociety

Black and white photograph

Alexander Imich, a Polish immigrant,

belatedly celebrated his 111th birthday at

home

on the Upper West Side last week.

Photograph:

Damon Winter

The New York Times

An Ever-Curious Spirit, Unbeaten After

111 Years

By RALPH BLUMENTHAL NYT

MAY 4, 2014

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/05/

nyregion/111-year-journey-of-the-worlds-oldest-man.html

Related > Obituary

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/09/

nyregion/worlds-oldest-man-though-only-briefly-dies-at-111-in-new-york.html

Colour photograph

Alexander Imich with Trish Corbett on

April 30.

“I never thought I’d be that old,”

he said

of his record-setting longevity.

Photograph: Damon Winter

The New York Times

World’s Oldest Man, Though Only Briefly,

Dies at 111 in New York

By RALPH BLUMENTHAL NYT

JUNE 9, 2014

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/09/nyregion/

worlds-oldest-man-though-only-briefly-dies-at-111-in-new-york.htm

centenarian UK

2023

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2023/feb/18/

100-centenarians-100-tips-for-a-life-well-lived

2022

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2022/jun/20/

tell-us-do-you-know-any-centenarians-or-are-you-one

2014

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/10/

the-secrets-of-living-to-a-ripe-old-age

http://www.theguardian.com/science/2014/mar/21/

number-people-over-100-fivefold-increase-statistics

2013

http://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2013/sep/27/

super-old-how-many-centenarians

2011

http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2011/apr/19/

live-to-be-100-one-in-four-britons

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/gallery/2011/mar/19/

100-year-olds-britain-photographs-chris-steele-perkins

2010

http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2010/dec/30/

one-in-six-people-live-100

2006

http://www.theguardian.com/society/2006/jan/18/

longtermcare.britishidentityandsociety

100 and She Just

Won't Stop

She is a national

champion,

a former activist

and a centenarian. And she runs.

NYT

Apr. 22, 2016

https://www.nytimes.com/video/nyregion/

100000004351251/100-and-she-just-wont-stop.html

centenarian USA

2023

https://www.npr.org/2023/12/07/

1218044792/centenarian-pearl-harbor-survivors-return-to-honor-

those-who-were-killed-82-year

https://www.npr.org/2023/11/29/

915981256/henry-kissinger-dead

https://www.npr.org/2023/01/02/

1145096613/centenarians-of-oklahoma

2021

https://www.npr.org/2021/04/24/

990505023/hester-ford-oldest-living-american-dies-at-115-or-116

2020

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/15/

books/a-e-hotchner-dead.html

https://www.npr.org/2020/02/05/

156511592/kirk-douglas-hollywood-tough-guy-and-spartacus-superstar-dies-at-103

https://www.npr.org/2020/01/17/

797305975/indianas-oldest-state-worker-is-retiring-at-102-i-ve-been-a-pretty-lucky-guy

2017

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/19/

opinion/on-turning-100-centenarian.html

2016

http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2016/04/22/

at-100-still-running-for-her-life/

http://www.npr.org/2016/03/30/

472442367/in-one-italian-village-nearly-300-residents-are-over-100-years-old

2015

http://www.npr.org/2015/09/25/

443489171/this-100-year-old-probably-runs-faster-than-you

http://www.npr.org/2015/05/17/

407447328/centenarian-among-the-oldest-ever-to-earn-a-ph-d

http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2015/04/11/

398325030/eating-to-break-100-longevity-diet-tips-from-the-blue-zones

turn 100 USA

https://www.npr.org/2023/01/02/

1145096613/centenarians-of-oklahoma

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/19/

opinion/on-turning-100-centenarian.html

http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2016/12/06/

as-he-turns-100-john-morris-recalls-a-century-in-photojournalism/

Susannah Mushatt

Jones,

who was believed

to be the world's

oldest person at 116,

(dies in New York)

USA 2016

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/05/13/

477966609/susannah-mushatt-jones-the-worlds-oldest-person-has-died-in-new-york

USA >

World's

oldest person, Edna Parker,

dies at 115

USA

2008

http://www.latimes.com/obituaries/

la-me-parker28-2008nov28,0,7015786.story

USA > World's oldest

man dies at 114 UK

Walter Breuning was

born in 1896

and put his longevity

down

to eating just two

meals a day

and working for as

long as he could

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/apr/15/

world-oldest-man-dies-at-114

Britain's oldest

person, Gladys Hooper, dies aged 113

UK 2016

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/jul/09/

britains-oldest-person-gladys-hooper-dies-aged-113

at 133

USA

https://www.npr.org/2022/11/16/

1137082042/the-woman-whose-dance-with-the-obamas-went-viral-

dies-at-113

at 112

USA

https://www.npr.org/2022/01/05/

1070789122/oldest-living-world-war-ii-veteran-dies-lawrence-brooks

at 111 USA

https://www.npr.org/2021/10/12/

1045309046/ruthie-tompson-disney-animator-obituary

108

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/mar/29/

spanish-flu-survivor-dies-from-coronavirus-aged-108

at 107

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/10/

business/mary-anderson-died-co-founder-of-rei-cooperative.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/21/

sports/football/at-107-a-buffalo-bills-fan-who-sees-it-all.html

“I’m one-oh-seven.” USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/20/us/

horror-drove-her-from-south-100-years-later-she-returned.html

at 106 USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/11/

world/europe/gilbert-seltzer-dead.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/07/

sports/ncaafootball/106-centenarian-john-risher-university-of-virginia.html

https://www.wbur.org/hereandnow/2016/03/04/

virginia-mclaurin-dancing-volunteer

105

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/31/

nyregion/coronavirus-nursing-homes-nyc.html

105-year-old runner USA

https://www.npr.org/2021/11/12/

1055008880/105-year-old-runner-100m-sprinter

103 USA

https://www.npr.org/2020/02/05/

156511592/kirk-douglas-

hollywood-tough-guy-and-spartacus-superstar-

dies-at-103

at 102 UK

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2023/jun/05/

a-new-start-after-60-

i-was-devastated-by-divorce-at-70-

but-at-102-i-know-the-secrets-of-a-well-lived-life

102

USA

https://www.npr.org/2020/01/17/

797305975/indianas-oldest-state-worker-is-retiring-at-102-

i-ve-been-a-pretty-lucky-guy

http://www.npr.org/2014/02/12/

275918145/at-102-reflections-on-race-and-the-end-of-life

101

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/24/

science/katherine-johnson-dead.html

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/05/16/

528615872/101-year-old-d-day-veteran-claims-new-record-for-oldest-skydiver

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/03/20/

520841767/david-rockefeller-philanthropist-banker-and-collector-

dies-at-101

at 101 USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/06/

arts/television/norman-lear-dead.html

100th birthday

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/23/

opinion/coronavirus-100-years-old.html

at 100

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/society/2006/jan/18/

longtermcare.britishidentityandsociety

at 100 USA

https://www.npr.org/2021/09/22/

1039721368/100-year-old-national-park-ranger-betty-soskin

turn 100

USA

https://archive.nytimes.com/lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2016/12/06/

as-he-turns-100-

john-morris-recalls-a-century-in-photojournalism/

World’s Oldest Man, Though Only Briefly,

Dies at 111 in New York

USA 2014

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/09/nyregion/

worlds-oldest-man-though-only-briefly-dies-at-111-in-new-york.html

the

oldest man on earth

Alexander Imich, 111 ¼ years old

USA 2014

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/05/nyregion/

111-year-journey-of-the-worlds-oldest-man.html

USA >

Fred Hale (1890-2004), the

world's oldest man UK

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2004/nov/22/usa.

sciencenews

the oldest man

in the world

Henry Allingham 2009

http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2009/jun/19/

briton-becomes-worlds-oldest-man

Arbella Perkins

Ewings USA

1894-2008

http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2008-03-23-

114-yearold-woman_N.htm

The oldest

person in the world

Elizabeth Bolden

2006

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/12/

obituaries/12bolden.html

the oldest

person in Britain

Corpus of news articles

Life / Health > Older people >

Centenarians

Life

Goes On, and On ...

December

17, 2011

The New York Times

By JAMES ATLAS

A FRIEND

calls from her car: “I’m on my way to Cape Cod to scatter my mother’s ashes in

the bay, her favorite place.” Another, encountered on the street, mournfully

reports that he’s just “planted” his mother. A third e-mails news of her

mother’s death with a haunting phrase: “the sledgehammer of fatality.” It feels

strange. Why are so many of our mothers dying all at once?

As an actuarial phenomenon, the reason isn’t hard to grasp. My friends are in

their 60s now, some creeping up on 70; their mothers are in their 80s or 90s.

Ray Kurzweil, the author of “The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend

Biology,” believes that we’re close to unlocking the key to immortality. Perhaps

within this century, he prophesies, “software-based humans” will be able to

survive indefinitely on the Web, “projecting bodies whenever they need or want

them, including virtual bodies in diverse realms of virtual reality.” Neat, huh?

But for now, it’s pretty much dust to dust, the way it’s always been — mothers

included. (Most of our fathers are long gone, alas. Women live longer than men.)

It’s the ones who aren’t dead who should baffle us. My own mother, for instance,

still goes to the Boston Symphony and attends a weekly current events class at

Brookhaven, her “lifecare living” center (can’t we find a less technocratic

word?) near Boston. She writes poems in iambic pentameter for every occasion. At

94, she’s hardly anomalous: there are plenty of nonagenarians at Brookhaven.

Ninety is the new old age. As Dr. Muriel Gillick, a specialist in geriatrics and

palliative care at Harvard Medical School, says, “If you’ve made it to 85 then

you have a reasonable chance of making it to 90.” That number has nearly tripled

in the last 30 years. And if you get that far... it’s been estimated that there

will be eight million centenarians by 2050.

It won’t end there. Scientists are closing in on the mechanism of what are

called “senescent cells,” which cause the tissue deterioration responsible for

aging. Studies of mice suggest that targeting these cells can slow down the

process. “Every component of cells gets damaged with age,” Leonard Guarente, a

biology professor at M.I.T., explained to me. “It’s like an old car. You have to

repair it.” We’re not talking about immortality, Professor Guarente cautions.

Biotechnology has its limits. “We’re just extending the trend.” Extending the

trend? I can hear it now: 110 is the new 100.

Is this a good thing or a bad thing? On the debit side, there’s the ... debit.

The old-age safety net is already frayed. According to some estimates, Social

Security benefits will run out by 2037; Medicare insurance is guaranteed only

through 2024. These projected shortfalls are in part the unintended consequence

of the American health fetish. The ad executives in “Mad Men” firing up Lucky

Strikes and dosing themselves with Canadian Club didn’t have to worry. They’d be

dead long before it was time to collect.

Then there’s the question of whether reaching 5 score and 10 is worth it — the

quality-of-life question. Who wants to end up — as Jaques intones in “As You

Like It” — “sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything”? You may live to

be as old as Methuselah, who lasted 969 years, but chances are you’ll feel it.

Worse — it’s no longer a rare event — you can outlive your children. Reading the

obituary of Christopher Ma, a Washington Post executive who had been a college

classmate of mine, I was especially sad to see that Chris was survived by his

wife, a daughter, a son, a brother, two sisters and “his mother, Margaret Ma of

Menlo Park, Calif.” Can anything more tragic befall a parent than to be

predeceased by a child?

These are the perils old people suffer. What about us, the boomers, now

ourselves elderly children? One challenge my entitled generation faces is that

many of our long-lived parents are running through their retirement money, which

leaves the burden of supporting them to us. (To their credit, it’s a burden that

often bothers our parents, too.) And the cost of end-stage health care is huge —

a giant portion of all medical expenses in this country are incurred in the last

months of life. Meanwhile, our prospects of retirement recede on the horizon.

Also, elder care is stressful and time consuming. The broken hips, the trips to

the E.R., the bill paying and insurance paperwork demand patience. A paper

titled “Personality Traits of Centenarians’ Offspring” suggests this cohort

scores high marks “extraversion, openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness.”

But even the well-adjusted find looking after old parents tough.

In the mid-’80s, when the idea of the “sandwich generation” was born — boomers

saddled with the care of aging parents while raising their own children — it

seemed like a problem we would eventually outgrow. Twenty-five years later,

we’re still sandwiched, and some of those caught in the middle feel the squeeze.

So what’s the good part? Time spent with an elderly parent can offer an

opportunity for the resolution of “unfinished business,” a chance to indulge in

last-act candor. A college classmate writes in our 40th-reunion book of

ministering to her chronically ill mother and being “moved by how the twists and

turns of complicated health care have deepened our relationship.” I hear a lot

about late-in-life bonding between parent and child.

My mother needs a minor operation. “I’ve outlasted my time,” she says as she’s

wheeled into surgery. “Anyway, you’re too old to have a mother.” Thanks, Ma.

What about Rupert Murdoch? His mother is 102. Also, if I’m too old to have a

mother, why do I still feel like a child?

Two weeks later, Mom comes to Vermont to recuperate. My father, who died a

decade ago at 87, is buried in the field behind our house (hope this is legal).

His gravestone reads “Donald Herman Atlas 1913-2001,” and it has an epitaph from

his favorite poet, T. S. Eliot, carved in italics: “I grow old ... I grow old

.../ I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled.” Mom likes to visit him

there. Standing over Dad’s grave, she carries on a dialogue of one. “I thought

I’d have joined you by now, Donny, but I’m a tough old bird.” As she heads back

up to the house, she turns and waves. “À bientôt.” See you soon.

Not so fast, Mom. I still have issues.

James Atlas

is the author

of “My Life in the Middle Ages: A Survivor’s Tale.”

Life Goes On, and On ...,

NYT,

17.12.2011,

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/18/

opinion/sunday/old-age-life-goes-on-and-on.html

Paying

for Old Age

February

25, 2011

The New York Times

By HENRY T. C. HU

and TERRANCE ODEAN

LIFE

expectancy at birth for Americans is about 78. But many Americans will die well

before then, while others, like Eunice Sanborn, who died in Texas last month,

will live to be 114.

Anyone planning for retirement must answer an impossible question: How long will

I live? If you overestimate your longevity, you might scrimp unnecessarily. If

you underestimate, you might outlive your savings.

This is hardly a new problem — and yet not a single financial product offers a

satisfactory solution to this risk.

We believe that a new product — a federally issued, inflation-adjusted annuity —

would make it possible for people to deal with this problem, with the bonus of

contributing to the public coffers. By doing good for individuals, the federal

government could actually do well for itself.

The insurance industry sells an inflation-adjusted annuity that goes part of the

way toward helping people cope with the possibility of outliving their savings.

During your working years or at the time of retirement, you can pay a premium to

an insurance company in exchange for the promise that the company will pay you a

fixed annual income, adjusted for inflation, until you die.

But in a world in which A.I.G. had an excellent rating only days before it

became a ward of the state, how can someone — particularly a young person — know

for sure which insurance companies will be solvent half a century from now?

Annuities aren’t federally guaranteed. The only backstops are state-based

systems, and the current protection ceilings are sometimes modest. If an

insurance company goes under, the retiree may end up with nothing close to what

was promised.

The federal government can offer a product that solves that problem. Individuals

would face no more risk of default than that associated with Treasury bills and

other obligations backed by the United States.

Here’s how it would work. Initially, people who wanted to buy this insurance

would enroll through one of the qualified retirement savings plans already

offered to the public, like a 401(k) plan, and could choose this annuity option

instead of, or in addition to, investments in stocks, bonds or mutual funds.

How much the payouts would be could be based on a variety of factors, including

interest rates on government bonds; mortality tables that, among other things,

take into account that healthier people are more likely to buy annuities; and

administrative costs. This new product wouldn’t cost the government a penny. In

fact, the Treasury would benefit. It is only an incremental move beyond issuing

inflation-adjusted bonds, which the Treasury already does. By allowing the

government to tap a new class of investors, the cost of government borrowing

over all would probably drop.

Moreover, by expanding the government’s base of domestic investors, the plan

would help address overreliance on foreign lenders, who now own close to half of

all outstanding federal debt — nearly 10 times the proportion in 1970. True, the

government would be on the hook if a technological breakthrough caused an

unanticipated increase in life expectancy. But that’s a risk that the government

is already bearing implicitly: that is, a drastic enough increase could threaten

the solvency of private issuers of annuities as well as the many retirees who

don’t have annuities, creating pressure for government bailouts of insurers or

individuals. Taking on the risk explicitly and pricing the fair cost of this

risk into the annuities is a far preferable route.

There is also the concern that government-issued annuities would crowd out

private annuity sales. To the contrary: they could spur growth in private

annuities. Since the inflation-adjusted monthly payments on such risk-free

government annuities would be low, many retirees may choose to supplement them

with riskier, higher-paying annuities.

Furthermore, insurance companies could be allowed to package the

government-issued annuities with their own products, creating appealing

combinations that mix safety and the potential for higher returns.

Our proposal is a winner for everyone. The Treasury could lower borrowing costs

and diversify its investor base while acknowledging and budgeting for risk that

it already bears. Individuals could eliminate the risk of living too long. By

looking at the promised rate of return on the annuities, individuals will have a

better sense of how much they need to save. The Eunice Sanborns of the world, as

well as all taxpayers, would rest a little easier at night.

Henry T. C. Hu

is a professor

at the University of Texas School of Law.

Terrance Odean is a

finance professor

at the University of California at Berkeley.

Paying for Old Age,

NYT,

25.2.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/26/

opinion/26Hu.html

Real Life Among the Old Old

December 30, 2010

The New York Times

By SUSAN JACOBY

I RECENTLY turned 65, just ahead of the millions in the baby

boom generation who will begin to cross the same symbolically fraught threshold

in the new year to a chorus of well-intended assurances that “age is just a

number.” But my family album tells a different story. I am descended from a long

line of women who lived into their 90s, and their last years suggest that my

generation’s vision of an ageless old age bears about as much resemblance to

real old age as our earlier idealization of painless childbirth without drugs

did to real labor.

In the album is a snapshot of my mother and me, smiling in front of the

Rockefeller Center Christmas tree when she was 75 and I was 50. She did seem

ageless just 15 years ago. But now, as she prepares to turn 90 next week, she

knows there will be no more holiday adventures in her future. Her mind is as

acute as ever, but her body has failed. Chronic pain from a variety of

age-related illnesses has turned the smallest errand into an excruciating

effort.

On the next page is a photograph of my maternal grandmother and me, taken on a

riverbank in 1998, a few months short of her 100th birthday. For one sunny

afternoon, I had spirited her away from the nursing home where she spent the

last three years of her life, largely confined to a wheelchair, with a bright

mind — like my mother’s today — trapped in a body that would no longer do her

bidding.

“It’s good to be among the living again,” Gran said, in a tone conveying not

self-pity but her own realistic assessment that she had lived too long to live

well.

Yet people my age and younger still pretend that old age will yield to what has

long been our generational credo — that we can transform ourselves endlessly,

even undo reality, if only we live right. “Age-defying” is a modifier that

figures prominently in advertisements for everything from vitamins and beauty

products to services for the most frail among the “old old,” as demographers

classify those over 85. You haven’t experienced cognitive dissonance until you

receive a brochure encouraging you to spend thousands of dollars a year for

long-term care insurance as you prepare to “defy” old age.

“Deny” is the word the hucksters of longevity should be using. Nearly half of

the old old — the fastest-growing segment of the over-65 population — will spend

some time in a nursing home before they die, as a result of mental or physical

disability.

Members of the “forever young” generation — who, unless a social catastrophe

intervenes, will live even longer than their parents — prefer to think about

aging as a controllable experience. Researchers who were part of a panel

discussion titled “90 Is the New 50,” presented at the World Science Festival in

2008, spoke to a middle-aged, standing-room-only audience about imminent medical

miracles. The one voice of caution about inflated expectations was that of

Robert Butler, the pioneering gerontologist who was the first head of the

National Institute on Aging in the 1970s and is generally credited with coining

the term “ageism.”

Earlier this year, a few months before his death from leukemia at age 83, I

asked Dr. Butler what he thought of the premise that 90 might become the new 50.

“I’m a scientist,” he replied, “and a scientist always hopes for the big

breakthrough. The trouble with expecting 90 to become the new 50 is it can stop

rational discussion — on a societal as well as individual level — about how to

make 90 a better 90. This fantasy is a lot like waiting for Prince Charming, in

that it doesn’t distinguish between hope and reasonable expectation.”

The crucial nature of this distinction has become foremost in my thinking about

what lies ahead.

My hope is that I will not live as long as my mother and grandmother. We all

want to be the exceptions: Elliott Carter, an active composer when he walked

onto the stage of Carnegie Hall for his centennial tribute in 2008; Betty White,

a bravura comedian who wows audiences at 88; John Paul Stevens, the author of

brilliant judicial opinions until the day he retired from the Supreme Court at

90. I, too, hope to go on being productive, writing long after the age when most

people retire, in the twilight of the print culture that has nourished my life.

Yet it is sobering for me — as it is for Americans in many businesses and

professions that once seemed a sure thing — to see younger near contemporaries

being downsized out of jobs long before they are emotionally or financially

ready for retirement.

Furthermore, I am acutely aware — and this is the difference between hope and

expectation — that my plans depend, above all, on whether I am lucky enough to

retain a working brain. I haven’t mentioned, because I don’t like to think about

it, that my paternal grandmother, who also lived into her 90s, died of

Alzheimer’s disease. The risk of dementia, of which Alzheimer’s is the leading

cause, doubles every five years after 65.

Contrary to what the baby boom generation prefers to believe, there is almost no

scientifically reliable evidence that “living right” — whether that means

exercising, eating a nutritious diet or continuing to work hard — significantly

delays or prevents Alzheimer’s. This was the undeniable and undefiable

conclusion in April of a major scientific review sponsored by the National

Institutes of Health.

Good health habits and strenuous intellectual effort are beneficial in

themselves, but they will not protect us from a silent, genetically influenced

disaster that might already be unfolding in our brains. I do not have the

slightest interest in those new brain scans or spinal fluid tests that can

identify early-stage Alzheimer’s. What is the point of knowing that you’re

doomed if there is no effective treatment or cure? As for imminent medical

miracles, the most realistic hope is that any breakthrough will benefit the

children or grandchildren of my generation, not me.

I would rather share the fate of my maternal forebears — old old age with an

intact mind in a ravaged body — than the fate of my other grandmother. But the

cosmos is indifferent to my preferences, and it is chilling to think about

becoming helpless in a society that affords only the most minimal support for

those who can no longer care for themselves. So I must plan, as best I can, for

the unthinkable.

I have no children — a much more common phenomenon among boomers than among old

people today. The man who was the love of my adult life died several years ago;

now I must find someone else I trust to make medical decisions for me if I

cannot make them myself. This is a difficult emotional task, and it does not

surprise me, for all of the public debate about end-of-life care in recent

years, that only 30 percent of Americans have living wills. Even fewer have

actually appointed a legal representative, known as a health care proxy, to make

life-and-death decisions.

I can see that the “90 is the new 50” crowd might object to my thinking more

about worst-case scenarios than best-case ones. But if the best-case scenario

emerges and I become one of those exceptional “ageless” old people so lauded by

the media, I won’t have a problem. I can also take it if fate hands me a

passionate late-in-life love affair, a financial bonanza or the energy to write

more books in the next 25 years than I have in the past 25.

What I expect, though — if I do live as long as the other women in my family —

is nothing less than an unremitting struggle, ideally laced with moments of

grace. On that day by the riverbank — the last time we saw each other — Gran

cast a lingering glance over the water and said, “It’s good to know that the

beauty of the world will go on without me.”

If I can say that, in full knowledge of my rapidly approaching extinction, I

will consider my life a success — even though I will have failed, as everyone

ultimately does, to defy old age.

Susan Jacoby is the author,

most recently, of the forthcoming

“Never Say Die:

The Myth and Marketing of the New Old Age.”

Real Life Among the

Old Old, NYT, 30.12.2010,

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/31/opinion/31jacoby.html

UK war veteran

becomes oldest man in the world

at 113

Death of Japanese titleholder

puts Britain's Henry Allingham

into the record

books

Maev Kennedy

Friday 19 June 2009

14.52 BST

Guardian.co.uk

This article was first published on guardian.co.uk

at 14.52 BST

on Friday 19

June 2009.

It was last updated at 15.09 BST

on Friday 19 June 2009.

At the age of 113 Henry Allingham, the oldest surviving veteran of the first

world war, has officially been proclaimed the oldest man alive by Guinness World

Records, after the death today of Tomoji Tanabe in Japan.

His friend Denis Goodwin, a founder of the First World War Veterans Association,

who has escorted Allingham to innumerable parades, memorial services and

presentations, said: "It's staggering. He will take it in his stride, like he

does everything else. He withdraws in himself and he chews it over like he does

all the things he has done in his life. That's his secret, I think."

At St Dunstan's home for blind ex-service personnel, near Brighton, where

Allingham has lived since he finally gave up his Eastbourne flat at the age of

110, chief executive Robert Leader sent sympathy to the family of Tanabe, who

died in his sleep, also aged 113. He added: "We are proud to be caring for such

a remarkable man. He has just celebrated his 113th birthday, and knowing Henry

as I do, he will take the news in his stride."

It is the latest in a series of recent landmarks in the extraordinarily ordinary

life of a man who remembers watching WG Grace playing cricket, returned from the

hell of the trenches to marriage, and had a long contented career as an

engineer. He never spoke of his wartime experiences for most of the 20th century

until he was asked to give some talks to school children.

Allingham is the last survivor of the Battle of Jutland, the last surviving

founding member of the Royal Air Force, the last survivor of the Royal Naval Air

Service, and the oldest ever surviving member of any of the British armed

forces.

As an engineer on a Sopwith Schneider seaplane, he recalls shells bouncing

across the waves in the Battle of Jutland, and he was behind the lines in

training and support units at the Western Front in 1917.

Despite an apparently blameless life, he attributes his longevity to

"cigarettes, whisky and wild, wild women – and a sense of humour". On his 110th

birthday, when he was already the oldest man in Britain, his presents included

enough whisky to swim in, including a bottle personally presented by Gordon

Brown.

He was awarded France's highest honour, the Légion d'honneur in 2003 as a

chevalier, upgraded earlier this year to officier.

In the last decade he has joined hundreds of ceremonies marking major

anniversaries of the first world war. He joined the march past the Cenotaph

every year until 2005. The following year's parade was the first without any

veterans of the first world war. But Allingham was not tucked up at home. He was

laying a wreath in France.

An honour which particularly pleased him came last December, when the Institute

of Civil Engineers presented him with an honorary award as Chartered Engineer

and he has since also been awarded an honorary doctorate from Southampton Solent

University. Despite a lifetime working in aviation and car engineering – he

finally retired from Ford in Dagenham in 1960 – he had no formal qualifications.

UK war veteran becomes

oldest man in the world at 113, G, 19.6.2009,

http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2009/jun/19/briton-becomes-worlds-oldest-man

World's oldest person,

Edna Parker,

dies at 115

November 28, 2008

From Times Online

Hannah Strange

A great-great-grandmother who was the world's oldest person has died at the

age of 115.

Indiana woman Edna Parker, who assumed the mantle more than a year ago, passed

away on Wednesday at a nursing home in Shelbyville. She was 115 years, 220 days

old.

Mrs Parker was born April 20, 1893, in central Indiana and had been recognised

by Guinness as the world’s oldest person since the 2007 death of Japan's Yone

Minagawa, who was four months her senior.

Dr Stephen Coles, the UCLA gerontologist who maintains a list of the world’s

oldest people, said Mrs Parker was the 14th oldest validated super-centenarian

in history. Maria de Jesus of Portugal, who was born September 10, 1893, is now

the world’s oldest living person, according to the Gerontology Research Group.

Mrs Parker became a widow in 1939 - the year Judy Garland starred in The Wizard

of Oz - when her husband, Earl Parker, died of a heart attack. She was 48. She

remained alone in their farmhouse until age 100, when she moved into a son’s

home and later to the Shelbyville nursing home.

Though she never drank alcohol or smoked and led an active lifestyle, she didn't

credit this for her advanced years.

A teacher, her only advice to those who gathered to celebrate when she became

the world's oldest person was to get “more education.”

Mrs Parker outlived both her sons, Clifford and Earl Jr. She also had five

grandchildren, 13 great-grandchildren and 13 great-great-grandchildren.

Don Parker, 60, said his grandmother had a small frame and a mild temperament.

She walked a lot and kept busy even after moving into the nursing home, he said.

“She kept active,” he said yesterday. “We used to go up there, and she would be

pushing other patients in their wheelchairs.”

Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels, who celebrated with Mrs Parker on her 114th

birthday, said it had been a "delight" to know her. She must have been a

remarkable lady at any age, he added.

Mrs Parker graduated from the state's Franklin College in 1911 and went on to

teach in a two-room school for several years.

She married Earl, her childhood sweetheart and neighbour, in 1913.

As was usual at the time, her career came to an end with her marriage and Mrs

Parker became a farmer's wife, spending her days tending the home and preparing

meals for the dozen men who worked on the farm.

Last year, she noted with pride that she and her husband were one of the first

owners of an automobile in their rural area.

Coincidentally, Mrs Parker lived in the same nursing home as Sandy Allen, whom

at 7ft 7¼ was officially the world's tallest woman until her death in August.

World's oldest person,

Edna Parker, dies at 115, Ts, 28.11.2008,

http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/us_and_americas/

article5250767.ece

In Strangers,

Centenarian Finds Literary Lifeline

August 1, 2008

The New York Times

By SARAH KRAMER

Stephanie Sandleben, a yoga instructor with tattoos on each shoulder, just

finished Chapter 19 of Tina Brown’s biography of Diana, Princess of Wales. Sara

Nolan, a 28-year-old graduate student, is 30 pages into a Rumer Godden novel.

Mark Kalinowsky, 48 and a real estate broker, has long since stopped reading; he

just comes to chat.

These three disparate characters are part of a ragtag crew that cycles through

the worn one-bedroom Murray Hill walk-up where Elizabeth Goodyear, who recently

celebrated her 101st birthday, is confined after two knee operations. A lifelong

lover of books, Ms. Goodyear lost her sight about four years ago, but in its

place has acquired a roster of readers who stop by regularly, bringing with them

dogs, gifts from their international travels and offerings of dark chocolate,

the elixir she has savored daily since she was 3.

“Usually there’s something going on here,” Ms. Goodyear observed the other day

during Ms. Sandleben’s weekly visit. “It’s strange. You’d think if you got to be

101, nothing much would happen. But it does.”

It started with a neighbor two generations younger, who once asked Ms. Goodyear

to watch her bags while she ran back upstairs to fetch a bow and arrows for a

trip to Maine.

As Ms. Goodyear grew more frail, the neighbor, a yoga instructor named Alison

West, started stopping by to kiss her goodnight each evening. On learning that

Ms. Goodyear had outlived her savings, Ms. West raised money to pay for her

rent-controlled apartment and part of her home health aide’s wages. Then, about

five years ago, she posted a sign seeking readers at yoga studios downtown and

sent out an e-mail message that was forwarded and forwarded again.

“Liz has no family at all, and all her old friends have died, but she remains

eternally positive and cheerful and loves to have people come by to read to her

or talk about life, politics, travel — or anything else,” the message read. “She

also loves good chocolate!”

Reading to the blind or the elderly is hardly novel. In New York City, two

well-established programs, Lighthouse International and Visions/Services for the

Blind and Visually Impaired, have hundreds of volunteers who make home visits or

read to clients at their offices and in senior centers. The National Federation

of the Blind provides a free telephone service through which people can hear

articles from more than 200 newspapers and magazines, and the Jewish Guild for

the Blind offers a similar program using special radios.

But the casual, organic way in which this particular group came together around

Ms. Goodyear is a window into the way New York can be a small town, the way

strangers become a community, the way books, reading and, especially, stories

bind people together.

“I remember looking forward to seeing you, but also looking forward to hearing

what’s happening next in the book,” Ms. Sandleben, the 30-year-old tattooed yoga

instructor, told Ms. Goodyear the other day. “I was relieved when you told me

that I was the only person reading the story because I didn’t want to miss out

on anything.”

Rebecca Feldman was one of the first to visit Ms. Goodyear, and has since

married, become a nurse and enrolled in graduate school to become a midwife.

“When I first started visiting, I was afraid she’d be dead the next time I

came,” said Ms. Feldman, 31, who is eight months pregnant and plans to soon

bring a new baby to meet Ms. Goodyear. “When I tell people about her, I say I

have this 101-year-old friend. I don’t think of it as volunteering anymore.”

Ms. Goodyear was born in 1907, a premature twin delivered at home in, as she

said, “a suburb of Philadelphia whose name I cannot remember.” (Her twin, who

weighed just a pound, died within an hour of birth.) On doctor’s orders, she

said, she was placed in a bureau drawer with hot water bottles and fed “whiskey

and cream” via medicine dropper.

She came to New York in 1928, seeking a stage career, but said that after six

months at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, “they told me I had poise,

personality and good looks but no acting ability.” Instead, Ms. Goodyear had a

variety of jobs, including assisting the lighting director for the New York City

Ballet and theater press agents. In between, she wrote or collaborated on 20

plays — including two, “Widow’s Walk” and “The Painted Wagon,” that made it to

the stage — and saw many more, the titles of which she ticks off,

alphabetically, in her mind to stave off loneliness and boredom.

After a brief marriage and an ectopic pregnancy, Ms. Goodyear moved to the

Murray Hill walk-up in 1961, when the rent was $69. “Everything was red,” she

said, laughing at the memory of asking a co-worker to repaint for her. “The

windowsills, the walls, the hall, the doors, everything.”

She has taken dance lessons from Martha Graham, had drinks with Duke Ellington,

spent a couple of hours with George Balanchine and his cats, and accompanied

Gypsy Rose Lee, actress and burlesque entertainer, on a game show. One visitor

recalled listening to Ms. Goodyear’s stories and then racing home to Google

unfamiliar characters.

“I think I only remember the amusing things; I don’t remember any depressing

things,” Ms. Goodyear said in an interview. “I think I just put them out of my

mind. I know everybody has things that they want to forget, but I don’t even

have to forget. I just don’t remember.”

Ms. Goodyear now has an aide from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. to help bathe, move and feed

her. Her only medications are a monthly shot of vitamin B12 and one daily

Tylenol her doctor prescribed because, as she put it, “I guess I have to do

something.” Because she can no longer leave her apartment without an ambulette,

her doctor makes house calls — once a year.

“He says he has to worry about his younger patients,” Ms. Sandleben said.

Ms. Goodyear may have a glass eye and some teeth missing, but she can recite

detailed plotlines from books she read 60 years ago.

A couple of weeks after her 101st birthday, her refrigerator contained five

bottles of Champagne and dark chocolate in truffle and bar forms. Birthday cards

from her 100th were strung across a wall of the living room, above the

plastic-covered table holding the beloved books the volunteers-turned-friends

have been reading — many are novels by Rumer Godden, a 20th-century British

writer whom Ms. Goodyear adores.

Glamour photos of Ms. Goodyear from the 1920s sit on the television. Four

decades of bound copies of Theatre World line the hallway shelves. In Ms.

Goodyear’s bedroom are a hospital bed and a couple of stuffed dogs. A “Do Not

Resuscitate” sign is posted by the front door.

Ms. Nolan, the graduate student, started visiting Ms. Goodyear two years ago,

but since moving to Colorado last August to study poetry, she calls once a week

and reads to her over the phone.

Mr. Kalinowsky, the real estate broker, said he also began visiting Ms. Goodyear

two years ago, after both his father and his grandmother died, because he missed

being close to people from other generations.

Ms. Sandleben brings Ms. Goodyear chocolates from Costa Rica, Zurich, SoHo. And

when she was away in Arizona on Ms. Goodyear’s most recent birthday, she got her

whole family on the phone to sing to her.

“I don’t know how I ever managed to do it,” Ms. Goodyear said of her numerous

friendships.

“You hook them in,” Ms. Sandleben teased.

“They come,” Ms. Goodyear responded, “and for some reason, they always come

back.”

In Strangers,

Centenarian Finds Literary Lifeline, NYT, 1.8.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/01/nyregion/01read.html

The age revolution:

How to live to be 150

Experts believe that the first person to live half way

through their second

century has already been born.

Jeremy Laurance, health editor,

reports on the

stunning breakthroughs that science promises,

while Sarah Harris outlines 10

ways

to extend your life

Published: 07 January 2007

The Independent on Sunday

For today's centenarians, living to be 100 is an achievement marked by a

message from the Queen. Within two generations it could be as routine as

collecting a bus pass.

The first person to live to 150 may already have been born, according to some

scientists. Worldwide, life expectancy has more than doubled over the past 200

years and recent research suggests it has yet to reach a peak.

What will the world be like when people live long enough to see their

great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren? Extending life by adding

extra years of sickness and growing frailty holds little appeal. Increased

longevity is one of the modern world's great successes, but long life without

health is an empty prize. The aim is for humans to die young - as late as

possible.

It is eight years since Jeanne Calment died peacefully in a nursing home in

Arles, southern France in 1998. She was aged 122 years, five months and 14 days

- and no one has yet challenged her title as the oldest person with an

authenticated birth record to have lived. She attributed her longevity to a diet

rich in olive oil, regular glasses of port and her ability to "keep smiling".

Destiny undoubtedly played a part, too. If you want to grow old, choose your

parents carefully. The genetic determinants of long life are gradually being

unravelled, In recent years at least 10 gene mutations have been identified that

extend the lifespan of mice by up to half. The good news is that these

super-geriatric mice are no more frail or sickly than their younger brethren.

In humans, several genetic variants have been linked with longevity. They

include a family of genes dubbed the Sirtuins, which one Italian study found

occurred more commonly in centenarian men than in the general population.

Researchers at Harvard Medical School in the US, convinced they have discovered

a "longevity gene", are now studying whether adding an extra copy of the gene

extends the lives of mice. The long term aim is to find a way of manipulating

the genes to add an extra decade or two to the human lifespan.

Other gene variants affect the production of growth hormone and insulin-like

growth factor (IGF), both of which increase metabolism - organisms with higher

metabolism tend to die sooner. Blocking receptors for growth hormone and IGF, so

slowing metabolism, provide possible targets for anti-ageing drugs.

Also promising, but still far from yielding concrete results, are telomeres,

which are present in every cell. Telomeres shorten with every cell division,

like a burning fuse; when they can shorten no more, the cell dies. Inhibiting

the enzyme telomerase to prevent the shortening of the telomeres in effect

extends the lifespan of the cell, and, as we are comprised of millions of cells,

could extend life.

Ageing cannot be reversed but it may, perhaps, be delayed. The emergence of the

extremely old population has only happened in the past 50 years and is chiefly

due to improvements in the health, lifestyle and environment of the elderly that

started in the 1950s - how we eat and drink, where we live, what we do.

Ageing is an irresistible target for snake oil salesmen and the pharmaceutical

industry. Several hundred medical compounds that can boost memory and learning

ability are being investigated. Research teams are examining genes for

Alzheimer's disease, mechanisms that cause cells to age and die, and brain

interfaces that promise to pump new life into aged or diseased limbs. The aim

here is to add life to years, as well as years to life, but ageing itself is

taking over as the new target for therapeutic innovation.

One promising avenue of research is to increase the resistance of cells to the

stresses caused by free radicals, unstable molecules that disrupt cellular

processes. There is no evidence that the sort of anti-ageing compounds sold over

the internet containing anti-oxidants that promise to tackle free radicals

actually slow ageing. However, delivering antioxidant enzymes direct to the cell

has been shown in mice to extend lifespan by 20 per cent - pointing the way to

future research.

But the optimism comes with a warning - that the consistent increase in life

expectancy we have enjoyed for the past 200 years could be about to go into

reverse. Some Jeremiahs in the scientific community claim ours could be the

first generation in which parents outlive their children. The greatest enemy of

extending life further is growing obesity, they say. Its effects could rapidly

approach and exceed those of heart disease and cancer. Calculations by US

scientists suggest that life expectancy would already be up to a year longer but

for obesity. As Jeannne Calment indicated, wisely if unexcitingly, on her 122nd

birthday, those who live moderately live long.

Ten things you can do to help increase your life expectancy

Exercise regularly

Keeping fit is the elixir of youth. Even 30 minutes of regular gentle exercise

three times per week, such as walking or swimming, can add years to your life

expectancy.

Aerobic exercise preserves the heart, lungs and brain, elevates your mood, can

help ward off breast and colon cancer and prevent atrophy of the muscles and

bones.

Gareth Jones of the Canadian Centre for Activity and Ageing in London, found

that for an over-50 who has never taken part in physical activity a brisk

30-minute walk three times a week can "basically reverse your physiological age

by about 10 years." Not exercising can knock off five years.

A 1986 study at Stanford University found that death rates fell in direct

proportion to the number of calories burned weekly.

Live dangerously

Mild sunburn, a glass of wine and some low-level radiation sounds like a recipe

for disaster, but many researchers believe that small doses of "stressors" can

reverse the ageing process.

While this "hormeosis", is not a licence to lie on a hot beach all day swigging

vodka, mild exposure to certain harmful agents can trigger the body's natural

repair mechanisms. The body is tricked into producing particular DNA-repair

enzymes and heat shock proteins to fix the damage that has been caused.

Sometimes the body's repair mechanisms overcompensate, treating unrelated damage

- "rejuvenating" as well as repairing it. Hormeosis could stretch the average

healthy life span to 90.

Live in a good area

It is not only how you live, but where you live that matters - and the residents

of Okinawa in Japan seem to know the secret. These Japanese islands are home to

the world's largest population of centenarians.

At 103, the daily routine of resident Seiryu Toguchi included stretching

exercises, a diet of whole grain rice and vegetables, gardening and playing his

three-stringed instrument, the sanshin.

The clean-living Seventh Day Adventists of Utah also do pretty well, living on

average eight years longer than their fellow Americans.

Worst off are those living in poor, polluted urban areas such as Glasgow, where

residents of the poorest suburbs have a life expectancy of only 54.

Overcrowding, dirt and noise all contribute to high blood pressure, anxiety and

depression, which reduce lifespan.

Be very successful

The more rich, privileged, successful and educated you are, the longer you will

live. The Whitehall Studies, 1967-77, examined the health of male civil servants

between the ages of 20 and 64, and found that men in the lowest-paid positions

had a mortality rate three times higher than those at the top level.

The study proved that the more important a task a person is asked to perform,

the longer they are likely to live; that the person at the top with the big

office, shouting orders will have a more relaxed and pleasurable existence than

his frustrated underlings. And it's not only civil servants: Canadian

researchers found that Oscar-winners live longer than other actors because of am

increased sense of self-worth and confidence.

And if you can't manage an Oscar, then only one extra year in education could

increase your life expectancy by a year and a half.

Eat the right foods

Certain foods delay the ageing process and may increase life expectancy. Green

leafy vegetables such as spinach and broccoli are rich in antioxidants and

beta-carotene. Diets high in fruit, vegetables, fibre and omega-3 oils, and low

in fat may prevent high blood pressure and heart disease.

In their low-fat diet of fruit, vegetables and rice, the long-living people of

Okinawa also consume more soy than anyone on earth, and soy is linked to low

cancer rates. Eating cooked tomato daily can slash your risk of heart disease by

30 per cent, found research at Harvard.

Challenge yourself

An active mind is as important as an active body. Studies show that you can

boost your immune system and delay the onset of conditions from depression to

dementia by keeping your brain engaged and stimulated.

Leonard Poon, director of the University of Georgia Gerontology Center found

that people who reach three figures tend to have a high level of cognition,

demonstrating skill in everyday problem-solving and learning. And Marian Diamond

of the University of California, Berkley, found that rodents who were given

problems to solve and toys to play with, lived 50 per cent longer.

Enjoy your life

Good relationships are the key to longevity. Social contact staves off

depression, stress and boosts the development of the brain and immune system.

Most research shows that people with family, friends, partners or pets, live

longer than those who don't. Marriage is also a good idea if you want to meet

the 100-mark, adding an average of seven years to the life of a man, and two to

a woman.

Indulgence, too, can be good for you. Chocolate can enhance endorphin levels and

acts as a natural antidepressant, wine contains natural anti-oxidants, and

laughing is good for your immunity.

Find God - or friends

It's official: having religion pays off - and not just in the after-life.

Nearly 1,000 studies have indicated that those who go to a place of worship are

healthier than their faithless counterparts - and live an average seven years

longer. One in 10 of the nuns of the convent of the School Sisters of Notre Dame

in Minnesota have managed to reach their 100th birthday. But atheists should not

despair: experts believe that a sense of community, and of belief in something

larger than yourself, are vital ingredients in a long and happy life.

Jeff Levin, author of God, Faith, and Health: Exploring the Spirituality-Healing

Connection, argues that a place of worship provides a social network and a

source of comfort to the ageing, ill and needy.

Reduce your calories

One hundred years of hunger is what you can look forward to if you follow the

Calorie Restriction philosophy. Practitioners of CR believe that by reducing

your calorie intake (by between 10 and 60 per cent) you can extend life

expectancy by lowering your metabolism and the production of harmful free

radicals. It sounds like torture, but there is research to suggest that it

works.

One study reported that participants who ate 25 per cent less for three months

had lower levels of insulin in their blood, a reduced body temperature and less

DNA damage. Brian Delaney, president of the California-based Calorie Restriction

Society, is aiming to live to 122, and with a diet of barely 1,800 calories per

day (2,500 is the normal for men).

Get your health checked

To last a century, stay ahead of life-threatening illnesses. It is possible with

regular blood tests to detect the first signs of prostate cancer, one of the

commonest causes of cancer deaths in men over 85.

If you're between 60 and 69 you can have free bowel cancer screening, cervical

screening for women aged 24 to 64, and mammograms for women aged 50 to 70.

Figures show that 95 per cent of women who had invasive breast cancer detected

by screening are alive five years later.

The age revolution: How

to live to be 150,

IoS,

7.1.2007,

http://news.independent.co.uk/uk/health_medical/article2132502.ece

In Mystery of Reaching 104,

Mrs. Astor Is a

Case Study

August 3, 2006

The New York Times

By JANNY SCOTT

One startling truth stands out among the

accusations about the care of Brooke Astor in her old age: Mrs. Astor is not

simply old, she is 104. That makes her a member of a most exclusive club, the

exceptionally long lived. Route to admission? Mysterious. Benefits of

membership? A blessing, though possibly a curse as well.

Mrs. Astor, the philanthropist and socialite, took her Dubonnet in moderation,

practiced yoga, gave up smoking a lifetime ago. She swam laps all winter, walked

with her dogs, had flocks of friends. She was disciplined, curious, flirtatious.

She had a mission. She was resilient. She never let herself, she said, become

depressed.

“It didn’t matter if we were at her apartment or the Knickerbocker or the Four

Seasons,” said Graydon Carter, the editor of Vanity Fair and a frequent lunch

companion of Mrs. Astor’s. “She would order a club sandwich or fish and a tall

Campari and soda, which she would drink about a quarter of.”

She was always reading, Mr. Carter said, two books at a time.

Mrs. Astor also comes from a long-lived lineage. Her mother, Mabel H. Howard

Russell, died at 88; her father, Maj. Gen. John Henry Russell, died at 74. Both

grew up at a time when average life expectancy was in the 40’s. A grandfather,

Rear Adm. John Henry Russell, born when John Quincy Adams was president, died at

69.

People who study exceptional longevity — the state of living to 100 or beyond —

say factors like diet, exercise, health habits, social support and the ability

to find meaning in life appear to play a role in getting people to, say, 85.

But, some of them say, they suspect that genes play the dominant role in hitting

100 or above.

“I have no one that was exercising,” said Nir Barzilai, director of the

Institute for Aging Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, who is

studying 400 centenarians. “I don’t have vegetarians. Nobody ate yogurt or

anything like that. If you have longevity genes, well, lucky you. If you don’t,

you know what to do.”

The gift of good genes is not without drawbacks, as the family struggle over the

guardianship of Mrs. Astor suggests. The longer a person lives, the more

generations take their place in line. Anecdotally, it appears to some that more

opportunities arise for squabbling over care, expenses and who stands to inherit

what.

“The longer the person lives, the more generations you have to deal with and the

more your own future becomes an issue,” said Roberta Satow, a sociologist at

Brooklyn College and the author of a book on caring for parents. “We have

70-year-olds taking care of their 90- and 100-year-old parents. Those

70-year-olds are worried about what they’re going to have if they’re spending

the money on Mom and Dad.”

In Mrs. Astor’s case, a grandson, Philip Marshall, has gone to court asking that

his father, Anthony D. Marshall, be replaced as her guardian. He has accused his

father, Mrs. Astor’s only son, of neglect — failing to fill her prescriptions,

cutting her staff, removing art, banishing her dogs to the pantry and forcing

her to sleep on a couch.

Anthony Marshall, 82, a Broadway producer and former diplomat, has said the

charges are untrue. He has said he has always taken good care of his mother,

overseeing annual expenditures of more than $2.5 million “for her care and

comfort alone.” He said she has a staff of eight to provide her with whatever

she needs.

There is no up-to-date count of centenarians in New York City. But, according to

the 2000 census, there were 1,253 women age 100 to 104 in the city at that time,

and 104 women age 105 to 109. The numbers of men over 100 were slightly lower.

Why some people live to those ages is unclear, researchers say.

Ronald D. Adelman, co-chief of geriatrics at Weill Medical College of Cornell

University in Manhattan, whose mother recently won a golf tournament at 91,

believes the answer is a mix of genes and factors like diet, exercise, social

networks and ability to handle stress.

But Dr. Barzilai, a professor of medicine and molecular genetics, said the

answer might lie in mutations in three genes that have a role in cholesterol and

lipoproteins.

“I have a 104-year-old lady who’s been smoking for 95 years,” he said. “Her

response is, ‘Every doctor who told me to stop is now dead.’ ”

Mrs. Astor’s life has not been free of adversity. Her first marriage was

unhappy; her second husband died in her arms. Her third husband, Vincent Astor,

died five and a half years into their marriage, but left her with $62 million

along with another $60 million for charity, which she helped parlay into $195

million and gave away over a 40-year period.

She ran the foundation into her late 90’s and remained a fixture on the social

scene. “She had the zest for life and the zest for people,” said John Fairchild,

a retired publisher of Women’s Wear Daily and a close friend. “She used to

drink, I remember, a watered-down Scotch. Nothing was ever in excess. She’s a

wonderful flirt. It kept her young.’’

Elizabeth Corbett, who worked as a dressmaker for Mrs. Astor, said Mrs. Astor

used to advise her to take a vacation: “She said, ‘Elizabeth, you have to get to

the shore, you have to get to the mountains, you have to get to four different

places to stay alive. You have to refresh the body and the mind.’ ”

And did Miss Corbett take the advice? “Of course not,” she said. “I didn’t have

the money or the time.”

In

Mystery of Reaching 104, Mrs. Astor Is a Case Study,

NYT,

3.8.2006,

https://www.nytimes.com/2006/08/03/

nyregion/03astor.html

Related > Anglonautes >

Vocapedia

contraception,

abortion,

pregnancy, birth,

life, life expectancy,

getting older / aging,

death

body,

health, medicine, drugs,

viruses, bacteria,

diseases / illnesses,

hygiene, sanitation,

health care / insurance

health > diseases > Alzheimer's

health > Coronaviruses >

SARS-CoV-2 virus >

COVID-19 disease >

pandemic timeline > 2019-2023

jobs > retirement, pensions

time

|