|

Vocapedia >

Earth >

Wildlife > Conservation

Woolly Mammoth,

Royal BC Museum, Victoria, British Columbia

Credit: Stephen Wilkes

for The New York Times

The Mammoth Cometh

Bringing extinct animals back to life is really happening

— and it’s going to be very, very cool.

Unless it ends up being very, very bad.

NYT

FEB. 27, 2014

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/02/magazine/the-mammoth-cometh.html

American bison / American buffalo

Wikipedia

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8d/American_bison_k5680-1.jpg

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:American_bison_k5680-1.jpg

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_bison

biodiversity

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/

biodiversity

https://www.theguardian.com/science/audio/2024/apr/16/

soundscape-ecology-a-window-into-a-disappearing-world-

podcast

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/apr/16/

world-faces-deathly-silence-of-nature-as-wildlife-disappears-

warn-experts-aoe

https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2022/dec/14/

the-age-of-extinction-can-we-prevent-an-ecological-collapse-

podcast -

Guardian podcast

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/video/2022/dec/07/

the-five-ways-were-killing-nature-and-why-it-has-to-stop-video-explainer

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/may/03/

climate-crisis-is-about-to-put-humanity-at-risk-un-scientists-warn

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/30/

opinion/ecology-lessons-from-the-cold-war.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2010/may/21/

un-biodiversity-economic-report

biodiversity

USA

https://www.npr.org/2022/12/07/1140861347/

un-biodiversity-convention-aims-to-slow-humanitys-war-with-nature-

heres-whats-at

biodiversity

destruction UK

https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2022/dec/14/

the-age-of-extinction-can-we-prevent-an-ecological-collapse-

podcast -

Guardian podcast

environmental

destruction UK

https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2022/dec/14/

the-age-of-extinction-can-we-prevent-an-ecological-collapse-

podcast -

Guardian podcast

ecological collapse

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2022/dec/14/

the-age-of-extinction-can-we-prevent-an-ecological-collapse-

podcast -

Guardian podcast

loss of

biodiversity UK

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/video/2022/dec/07/

the-five-ways-were-killing-nature-and-why-it-has-to-stop-

video-explainer

drop USA

https://www.npr.org/2025/09/12/

nx-s1-5535551/insect-populations-human-interference-study

be on the decline

USA

https://www.npr.org/2025/09/12/

nx-s1-5535551/insect-populations-human-interference-study

biodiversity crisis UK

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/video/2022/dec/07/

the-five-ways-were-killing-nature-

and-why-it-has-to-stop-video-explainer - Guardian video

UN biodiversity report

2010 UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2010/may/21/

un-biodiversity-economic-report

ecosystem

USA

https://www.npr.org/2025/08/05/

nx-s1-5449187/desert-tortoise

species UK

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/may/03/

climate-crisis-is-about-to-put-humanity-at-risk-

un-scientists-warn

threatened species

threatened bird >

seabirds > USA >

Hawaii > Newell's shearwater

USA

https://www.npr.org/2020/01/04/

792730362/threatened-hawaiian-bird-strives-to-make-comeback

endangered species / animals UK

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/

endangeredspecies

https://www.npr.org/2025/08/05/

nx-s1-5449187/desert-tortoise

https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2024/feb/28/

from-the-archive-how-maverick-rewilders-are-trying-to-turn-back-the-tide-of-extinction-

podcast - Guardian podcast - first release in 2020

https://www.npr.org/2021/06/03/

1002612132/endangered-right-

whales-are-shrinking-scientists-blame-commercial-fishing-gear

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/may/15/

endangered-species-day-a-photo-essay

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2012/aug/05/

overseas-territories-wildlife-threatened

http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2009/jun/25/

sharks-extinction-iucn-red-list

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2008/dec/28/

wildlife-animals-conservation

http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2006/nov/02/

travelnews.science

http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2006/mar/28/

g2.conservationandendangeredspecies

endangered species / animals USA

https://www.npr.org/2025/08/05/

nx-s1-5449187/desert-tortoise

https://www.npr.org/2022/11/29/

1139665889/northern-long-eared-bat-endangered-white-nose

https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/08/01/

541010111/great-lakes-gray-wolves-spot-safe-on-endangered-species-list-for-now

https://travel.nytimes.com/2011/05/15/

travel/endangered-species-travel-guide.html

endangered fungus >

fingers of willow gloves UK

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/mar/26/

rare-fungus-willow-gloves-scotland-england-hopes-to-save-species

Eastern

Australia > endangered species > Koalas

USA

https://www.npr.org/2022/02/11/

1080081190/koalas-endangered-australia

endangered and extinct species USA

https://www.nytimes.com/topic/subject/

endangered-and-extinct-species

https://www.npr.org/2023/10/17/

1206664432/21-species-extinct-fish-wildlife-birds

Them and us:

endangered animals - in pictures

UK

25 May 2012

Many of the world's animals

are fast disappearing.

Perhaps, says Diane Ackerman,

Joel Sartore's majestic portraits

will help us not only feel

a greater kinship with other species,

but realise what's at stake

when the world's biodiversity

is allowed to shirink

dramatically

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/gallery/2012/may/25/

animals-wildlife-photographs

England's threatened species by region

UK

March 2010

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/interactive/2010/mar/11/

england-lost-threatened-species

doomed species

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/may/14/

london-zoo-team-save-doomed-species-rewilding-socorro-dove-wild

a disappearing world

> nature loss UK

https://www.theguardian.com/science/audio/2024/apr/16/

soundscape-ecology-a-window-into-a-disappearing-world-

podcast

vanish

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/19/

science/bird-populations-america-canada.html

species > go extinct

USA

https://www.npr.org/2024/12/06/

nx-s1-5218583/how-many-species-could-go-extinct-from-climate-change-

it-depends-on-how-hot-it-gets

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/04/16/

climate/glaciers-melting-alaska-washington.html

extinct UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2008/dec/14/

birdlovers-split-reintroduction-sea-eagle

exctinct animal

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/02/

magazine/the-mammoth-cometh.html

extinct

in the wild UK

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/may/14/

london-zoo-team-save-doomed-species-rewilding-socorro-dove-wild

be threatened

with extinction UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2007/nov/12/

conservation.wildlife

on the brink of extinction

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2006/jul/21/

conservationandendangeredspecies.internationalnews

driven to extinction

extinct species

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2010/mar/11/

extinct-species-england

extinction

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/series/

the-age-of-extinction

https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2022/dec/14/

the-age-of-extinction-can-we-prevent-an-ecological-collapse-

podcast -

Guardian podcast

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/aug/24/

vesper-flights-by-helen-macdonald-review-towards-the-sixth-extinction

https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2024/feb/28/

from-the-archive-how-maverick-rewilders-are-trying-to-turn-back-the-tide-of-extinction-

podcast - podcast released in 2020

http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/nov/26/

iucn-red-list-endangered-species-extinction

http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/sep/29/

scottish-wildcat-extinction-by-stealth

extinction

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/28/

climate/endangered-animals-extinct.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/13/

opinion/sunday/the-global-solution-to-extinction.html

mass

extinction USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/01/

science/mass-extinctions-are-accelerating-scientists-report.html

sixth mass extinction

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/11/

climate/mass-extinction-animal-species.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/16/

books/review/the-sixth-extinction-by-elizabeth-kolbert.html

http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2009/05/25/

the-sixth-extinction

species at risk of

annihilation UK

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/may/03/

climate-crisis-is-about-to-put-humanity-at-risk-

un-scientists-warn

biological

annihilation USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/11/

climate/mass-extinction-animal-species.html

wild species at risk UK

http://www.theguardian.com/environment/gallery/2016/may/25/

do-you-know-your-wild-species-at-risk-in-pictures

The noughties: a decade of lost species

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/gallery/2009/oct/21/

decade-lost-species

England's lost species by region > Interactive

map UK 2010

The biggest national study of threats to

biodiversity

highlights around 500 species of flora and fauna

that have been lost completely from England.

Still more species

are becoming extinct by region.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/interactive/2010/mar/11/

england-lost-threatened-species

kill off

die out

USA

https://www.npr.org/2025/08/05/

nx-s1-5449187/desert-tortoise

wipe out

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2010/jun/06/

tide-oil-wipes-out-pelican

http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2007/mar/25/

conservation.theobserver

(be)

wiped out

USA

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/oct/13/

almost-70-of-animal-populations-wiped-out-since-1970-report-reveals-aoe

Almost

70% of animal populations

wiped

out since 1970, report reveals UK

Huge

scale of human-driven loss of species

demands

urgent action,

say

world’s leading scientists

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/oct/13/

almost-70-of-animal-populations-wiped-out-since-1970-report-reveals-aoe

endangered habitats

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/

endangered-habitats

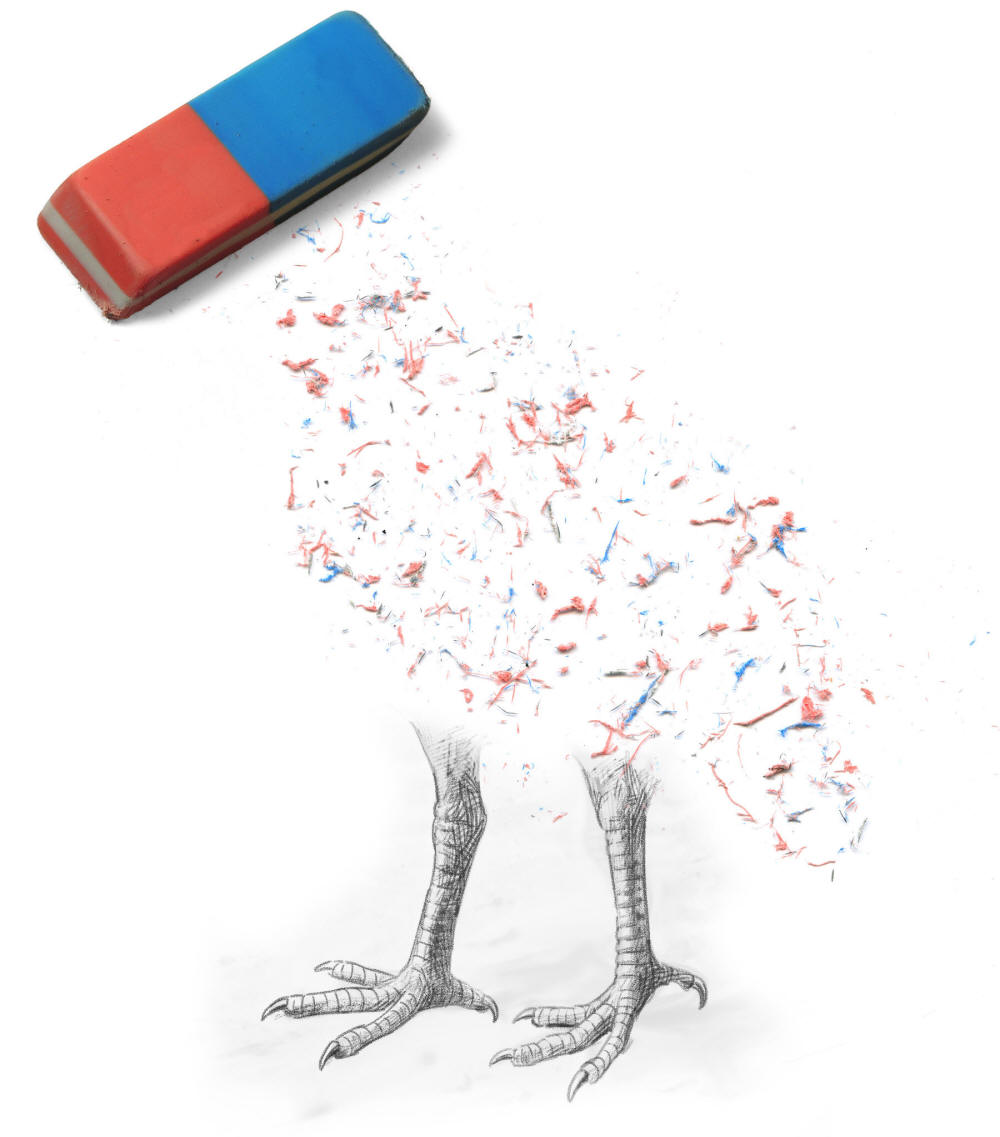

Illustration: Christoph Niemann

Without a Trace

‘The Sixth Extinction,’ by Elizabeth Kolbert

By

AL GORE

NYT

FEB. 10, 2014

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/16/

books/review/the-sixth-extinction-by-elizabeth-kolbert.html

conservation UK

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/

conservation

http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2009/jun/25/

sharks-extinction-iucn-red-list

conservationist UK

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/may/14/

london-zoo-team-save-doomed-species-rewilding-socorro-dove-wild

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2011/jun/26/

salmon-numbers-leap

Environment Agency UK

https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/

environment-agency

http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2006/aug/03/

conservationandendangeredspecies.uknews

World Wide Fund WWF

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/

wwf

http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2006/oct/10/

pollution.conservation

CITES

(the Convention on International Trade

in Endangered Species

of

Wild Fauna and Flora)

is an international agreement

between governments.

Its aim is to ensure that international trade

in specimens of wild animals and plants

does not threaten their survival.

https://cites.org/eng/disc/what.php

conservationist > Lawrence Anthony

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2009/feb/22/

lawrence-anthony-conservationist

save N from extinction

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2010/oct/27/

the-decline-of-the-eel

rewilders

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2024/feb/28/

from-the-archive-

how-maverick-rewilders-are-trying-to-turn-back-the-tide-of-extinction-

podcast

conservationists’ hopes of rewilding captive species

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/may/14/

london-zoo-team-save-doomed-species-rewilding-socorro-dove-wild

environmentalist > Roger Deakin UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2008/oct/25/

roger-deakin-environmentalist-nature-diary

ecologists UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2013/jan/29/

hedgehog-population-dramatic-decline

naturalist > David Attenborough UK

https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/

david-attenborough

https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2020/dec/12/

david-attenborough-the-earth-and-its-oceans-are-finite-

we-need-to-show-mutual-restraint

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/sep/26/

why-david-attenborough-is-the-doomsayer-we-still-adore

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2020/sep/25/

david-attenborough-a-life-on-our-planet-review-climate-emergency-documentary

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/sep/18/

dont-look-away-now-are-viewers-finally-ready-for-the-truth-about-nature-aoe

https://www.theguardian.com/world/video/2020/jul/09/

sir-david-attenborough-appeal-save-zsl-london-whipsnade-zoos-charity-video

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/may/28/

david-attenborough-climate-crisis-a-life-on-our-planet

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/video/2019/dec/30/

its-nice-to-meet-you-greta-thunberg-and-david-attenborough-speak-over-skype-video

https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2019/oct/27/

seven-worlds-one-planet-review-david-attenborough-breathtaking-moving-harrowing

http://www.guardian.co.uk/tv-and-radio/2012/oct/26/

richard-attenborough-climate-global-arctic-environment

http://www.guardian.co.uk/tv-and-radio/2012/may/05/

david-attenborough-bbc-series

http://www.guardian.co.uk/tv-and-radio/2010/oct/31/

david-attenborough-feature-readers-questions

protected species

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/topic/subject/

endangered-and-extinct-species

rewild UK

https://www.theguardian.com/news/audio/2020/dec/29/

revisited-otters-badgers-and-orcas-can-the-pandemic-help-rewild-britain-podcast

Corpus of news articles

Earth > Wildlife > Biodiversity,

Conservation, Extinction

A

Coast-to-Coast Guide

to Endangered Species

May 13,

2011

The New York Times

By BRYN NELSON

THE whoosh

of a surfacing orca and the glower of a mother grizzly still have the power to

raise goose bumps; a soaring California condor can yet astonish. But chances to

admire many of our wildlife neighbors are becoming increasingly uncommon.

Invasive buffelgrass is crowding out saguaros and other native cactuses

throughout the Southwest, while melting sea ice is threatening the Pacific

walrus and polar bear in Alaska. Mosquito-borne diseases are threatening

Hawaii’s songbirds, and white-nose syndrome is wiping out bats in the East.

Even so, the nation brims with natural wonders and a treasure trove of diverse

plants and animals. Conserved parklands, including our national parks and

wildlife preserves and their state and local counterparts, provide bulwarks

against further habitat loss and offer some of the best viewing opportunities

for these rarities.

Some federally protected species, like the northern spotted owl and gray wolf,

have become symbols of bitter political divides. Others, like the bald eagle and

American bison, have regained their status as emblems of national pride. Nearly

all can inspire travelers to go well out of their way to see, to hear or to

experience something truly marvelous.

Here is a sampling of the wildlife that can be found. Animals and plants

identified in boldface are either among the nearly 1,400 endangered or

threatened species or populations, or among the 260 candidates waiting to be

listed under the Endangered Species Act.

Northeast

Sandy soils and the coastal influence of the North Atlantic have fashioned a

range of unique habitats here, from Maine’s blueberry barrens to New Jersey’s

“pygmy forest” of dwarf pitch pine and scrub oak. Some natural wonders have

already vanished, like the sea mink hunted to extinction in the 19th century.

But visitors may still glimpse the increasingly rare New England cottontail

rabbit in tangled thickets or the wetland-dwelling bog turtle and ringed

boghaunter, an orange-striped dragonfly among the rarest in North America.

Two destinations better known for their beaches host a particularly impressive

roster of coastal-dwelling curiosities. Wildlife is recolonizing Cape Cod

National Seashore (nps.gov/caco), meaning increased sightings of weasel-like

fishers, American oystercatchers and a booming population of seals. The seals,

in turn, have attracted great white sharks to what amounts to a sandbar

smorgasbord.

A springtime bonanza of plankton can lure endangered North Atlantic right whales

to within spotting distance, while summer rains bring the reclusive eastern

spadefoot toads from their burrows for an evening of frenzied mating in the

Province Lands’ vernal pools. Protective mesh fences mark the well-camouflaged

nesting sites of one of the region’s biggest natural attractions, the threatened

piping plover.

Likewise positioned along the Atlantic migratory flyway, Fire Island National

Seashore is prime birding territory in the spring and fall along the

32-mile-long barrier island. The piping plover and the endangered roseate tern

breed here every year; plovers can sometimes be seen darting along the beach.

Visitors to Sailors Haven can stroll the boardwalk through the dune-protected

sunken forest, marked by American holly trees up to 300 years old and tangles of

wild grape, greenbrier and other vines. The threatened seabeach amaranth, a

low-growing, waxy-leaved plant with reddish stems, sprouts intermittently above

the high tide line. Edible beach plums blanket the dunes’ backsides, and

insectivorous plants like sundews grow farther inland in the low, moist soils.

Southeast

As more temperate climes give way to a tropical Caribbean influence, the seasons

here compress into wet and dry; the continent ends in a confluence of wetlands

and warm coastal waters. Habitats critical to the survival of many species are

becoming worn around the edges, however, from the Mississippi River delta to

Florida’s mangroves and the barrier islands of the Carolinas. For some regional

icons, like the ivory-billed woodpecker, it may already be too late. But

conservation efforts are helping other species hang on, such as the Tennessee

purple coneflower, the Mississippi gopher frog and the Louisiana black bear.

One of the nation’s best-known wetlands and a historical trail provide prime

access to the region’s untamed southern living.

Everglades National Park (nps.gov/ever), the largest remaining subtropical

wilderness in the United States, is actually a patchwork of habitats extending

from the outskirts of suburban Miami to Florida’s Gulf Coast. With a

half-million acres underwater, the park claims the biggest protected mangrove

forest in the Western Hemisphere as well as the continent’s most extensive stand

of sawgrass prairie.

Shark River Slough, a “slow-moving river of grass” that ambles southward at 100

feet a day, is a dominant feature. Here, river otters snack on baby alligators

while marsh rabbits venture out for a swim. The Cape Sable seaside sparrow — the

“Goldilocks bird” — forages in the slough’s just-right marsh prairie, while the

equally rare wood stork nests near the Shark Valley Visitor Center off Highway

41. Binocular-equipped hikers sometimes spot greater flamingoes during high tide

from the end of Snake Bight Trail, north of the Flamingo Visitor Center, while

right outside the center American crocodiles frequent Florida Bay’s brackish

waters. The nearby Flamingo Marina is a good place to see the Florida manatee in

winter, especially from a canoe or kayak; bottlenose dolphins frolic farther out

in the sun-splashed bay. With an estimated population of less than 100 in all of

South Florida, the Florida panther is far more elusive; most of the tawny

wildcat’s prime habitat lies north of Interstate 75 in Big Cypress National

Preserve (nps.gov/bicy).

Combining history with wildlife, the Natchez Trace National Parkway

(nps.gov/natr) wends its way across 444 miles and three state lines: an

800-foot-wide ribbon of green with a roadway running through it from the

foothills of the Appalachians in Tennessee to the bluffs of Natchez, Miss. Duck

River, which flows along the parkway near milepost 404, supports a rich

diversity of fish and mussels. Ruby-throated hummingbirds feast on orange

jewelweed nectar near Rock Spring.

In 2003, biologists cheered the first confirmed sighting of small brown

Mitchell’s satyr butterflies in the park, in wetlands dominated by sedges

between mileposts 290 and 302. Black Belt prairie near Tupelo, with its loamy

soil and chalky substrate, nourishes more than 400 plant species and abundant

birds. Along the Pearl River watershed near milepost 125, patient observers may

spot a petite ringed map turtle basking on fallen trees in the river,

identifiable by the yellow rings decorating its bony carapace. And between

mileposts 85 and 87, cautious drivers can catch sight of rare Webster’s

salamanders crossing the road en masse after winter rains as they head from

foraging grounds on limestone outcroppings to ephemeral breeding pools.

Midwest

Great Lakes, big rivers and meandering streams cover the nation’s midsection,

including nearly 12,000 lakes in Minnesota alone. Together, these bodies of

water harbor the highest diversity of freshwater mollusks in the world, an

impressive collection imperiled by habitat degradation and the invasive zebra

mussel. Dozens of species, including the acorn ramshorn, are presumed extinct.

Others have made a comeback, with thousands of bald eagles spending their

winters on the Mississippi. But survival is tenuous for natives like the Indiana

bat, Kirtland’s warbler and nearly two-foot-long Ozark hellbender salamander.

Two parks hugging the Lake Michigan shoreline provide a rich sampling of the

Midwest’s other varied inhabitants.

Near the tip of the “little finger” on the Michigan mitt, Sleeping Bear Dunes

National Lakeshore (nps.gov/slbe) offers sweeping views of Lake Michigan, the

famous Dune Climb and nesting sites for the endangered Great Lakes population of

piping plovers. Spiky-leafed Pitcher’s thistle occupies the open dunes, and the

delicate yellow-bloomed Michigan monkey-flower rises up from flowing springs of

inland lakes. Elusive bobcats, snowshoe hares and northern flying squirrels

populate the night. South Manitou Island reveals one of the region’s best

natural bouquets of springtime wildflowers, an old-growth grove of giant

northern white cedars and a dozen species of orchid.

At the southern tip of Lake Michigan, prickly pear cactuses grow beside Arctic

bearberry along the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore (nps.gov/indu). In

midsummer, visitors hiking along the Inland Marsh Trail might glimpse the

inchlong Karner blue butterfly feeding on nectar in an exceedingly rare black

oak savanna, the largest such ecosystem in the nation. A true sphagnum moss bog

adds unexpected diversity to a park featuring more than 1,100 plant species.

Pitcher’s thistle grows here too, and piping plovers ply the sandy beaches.

Migratory birds, including merlins and short-eared owls, use the shoreline of

Lake Michigan as a navigational aid to reach their winter roosts.

Great Plains

The prairie has lent its name to a long list of flora and fauna: the western

prairie fringed orchid and the prairie mole cricket make their homes here, as do

both the greater and lesser prairie-chicken. Wild grasslands, though, are far

from monolithic, with wet and dry, hill and savanna, tall and short varieties,

each sheltering its own assemblage of life. Natural wildfires have been a part

of the prairie’s lifecycle for millenniums, but the landscape is now one of

North America’s most human-altered, challenging the resilience of species like

the statuesque whooping crane and little Topeka shiner.

Some bastions of grasslands remain, including one set atop a remarkable

labyrinth of limestone.

Below Wind Cave National Park (nps.gov/wica) in South Dakota, the world’s

fourth-longest cave system extends in a maze of passageways filled with boxwork,

frostwork and popcorn formations that occupy more than 135 miles. Above ground,

a sea of grass gives way to vanilla-scented ponderosa pines. The resident bison

herd, repopulated from 14 animals housed at the Bronx Zoo in 1913, numbers about

400 now and shares the grasslands with reintroduced elk and pronghorn antelope.

Black-tailed prairie dog towns, including one at Bison Flats, less than a

half-mile from the visitors’ center, are magnets for the black-footed ferret, a

major predator. Observant tourists on evening walks may spot one of the roughly

four dozen ferrets reintroduced to the park in 2007 and 2010 peering back at

them from a conquered prairie dog den. The prairie dog towns also attract

thirteen-lined ground squirrels, prairie rattlesnakes and prairie falcons. The

star lily’s snow-white petals and the jewel-toned American rubyspot damselfly

appear like fragile grace notes, while hikers may see spirited dance

competitions among groups of male sharp-tailed grouse in April or May as they

vie to impress a mate.

Rocky Mountains

A rugged spine running up the continent from northern New Mexico through

northern Montana into Canada, the Rocky Mountains form a natural dividing line

for wildlife: white-tailed deer predominate to the east, while mule deer rule

the west. Deer and other game have supported stealthy predators like the North

American wolverine and Canada lynx, though the mountains have drawn their share

of more destructive predation as well. Blister rust, an introduced fungal

disease, is laying waste to increasingly rare whitebark pines; the invasive

banded elm bark beetle is felling elms already weakened by drought or Dutch elm

disease.

For a bit of comic relief, it’s hard to beat the elaborate courtship strut of

the greater sage-grouse, while breathtaking beauty lies in one destination that

still survives virtually intact.

With its million-plus acres of nearly pristine wilderness, Glacier National Park

(nps.gov/glac) is a haven for grazing ungulates: moose and elk, bighorn sheep

and mountain goats. Rarely seen gray wolves furtively hunt their prey. Tourists

have a better chance of spotting one of the park’s roughly 300 grizzly bears

from the Many Glacier Valley or Logan Pass trails (group outings are highly

recommended, as is bear spray).

In this hiker’s paradise, tall white tufts of lilylike beargrass bloom

unpredictably every three to seven years. The more bear-favored yellow glacier

lilies cover hillsides high above turquoise glacial lakes like Grinnell and

Cracker. Floating trumpet-shaped water howellia flowers grace the margins of

wetlands linked to ephemeral kettle ponds. Bald eagles soar amid the peaks,

American pikas scurry in the high country, and bull trout spawn in streams

below. The park’s 25 glaciers are themselves endangered, expected to vanish well

before 2030 if warming trends continue.

Southwest

The sun-baked Southwest might seem an inhospitable environment, but its

astonishingly varied habitats host an array of plants and animals adapted to

steep mountains and canyons, sere deserts and vast flatlands. The iconic great

roadrunner still races throughout the region. Other indigenous species, like the

desert tortoise and the enormous Colorado pikeminnow, have seen their home

ranges shrink precipitously, and natives like the Mexican gray wolf and the

California condor, both reintroduced in the 1990s, face uncertainty.

Big Bend National Park (nps.gov/bibe) encapsulates the seeming contradiction of

a harsh desert teeming with life. The largest protected swath of Chihuahuan

Desert in the United States, the 800,000-acre Big Bend borders the Rio Grande in

southwestern Texas and rises in elevation from less than 2,000 feet to nearly

8,000 feet. The park’s aerial menagerie is unsurpassed in the nation, with

confirmed sightings of more than 450 bird species, 180 butterfly species and 20

species of bat.

Birders can spy on a pair of nesting common black-hawks by Rio Grande Village,

glimpse the only Colima warblers north of Mexico and even spot a black-capped

vireo in the transition zone between mountain woodlands and desert. On the

ground, visitors logged 175 sightings of mountain lions last year. More than 50

cactus species dot the desert with vivid blooms every spring, including the

diminutive pink-fringed Chisos Mountain hedgehog cactus in the low open desert.

In the summer, Mexican long-nosed bats stir at twilight to feed on the nectar of

blooming century plants; in the fall, male tarantulas in search of mates cross

the roads, their eyes shining diamond blue in the night.

Northwest

Vast evergreen forests end abruptly at the rugged Northwest coastline and the

bracing waters of the North Pacific. In Alaska, the cold is not nearly enough to

halt the melting of sea ice critical for polar bear survival, and humans are

increasingly disturbing the arctic tundra habitat of the yellow-billed loon.

Elimination of the northern spotted owl’s old-growth forest habitat through

logging has spawned bitter political battles; meanwhile, the last known Tacoma

pocket gophers were killed by domestic cats. Some endemic species remain in

scattered pockets, like the giant Palouse earthworm, which can grow to more than

three feet in length; the coastal meadow-dwelling Oregon silverspot butterfly;

and the reddish-gray northern Idaho ground squirrel.

In Washington, the largest unmanaged herd of Roosevelt elk in the nation roams

the impossibly green Hoh and Quinault rain forests of Olympic National Park

(nps.gov/olym), where annual precipitation can be 12 to 14 feet. Record-setting

Sitka spruce and western red cedar (their circumferences can reach 60 feet) are

standouts in a forest of giants; when toppled, they can be swept out to sea

along the peninsula’s 10 major rivers and then washed ashore as gargantuan

pieces of driftwood.

From the viewing platform at Salmon Cascades on the Sol Duc River, visitors can

see coho salmon jumping in October, while chinook salmon reaching up to 70

pounds will soon spawn freely up the Elwha River upon completion of an extensive

dam removal project. Migrating gray whales can be spotted in March and April

along Rialto or Kalaloch Beaches, though you will have to go a bit farther north

to Lime Kiln Point State Park to see killer whales, or orcas. Native animals

like the Olympic chipmunk frequent the edges of the national park’s subalpine

forests; the increasingly rare Olympic marmot inhabits the backcountry. Hikers

willing to become intimately familiar with tide charts may even spy sea otters

lolling in secluded coves along the coastline and Steller sea-lions hauled out

on the offshore rocks.

West

Within the seismically active Ring of Fire, the West has been shaken by

volcanoes and earthquakes but tempered by the Pacific. The lovely western lily

clings to the northern coast, while the fork-tailed California least tern visits

the southern beaches during the summer breeding season. Inland, the Great Basin

bristlecone pines of Inyo National Forest are among the most ancient living

things in the world, with many dated to more than 4,000 years old.

Thousands of miles across the Pacific, Hawaii’s volcanic soils have nourished an

exotic profusion of endemic plants and animals. Dozens of species have already

succumbed to threats from the mainland, but hothouse wonders remain, including

more than 30 types of the protected haha plants and the blind Kauai cave wolf

spider.

Golden Gate National Recreation Area (nps.gov/goga), the nation’s largest urban

park, also has among the highest number of endangered plant and animal species.

Teeming tidal pools and more than 100 sea caves stud the rocky California coast,

where brown pelicans dive for dinner. Harbor seals and California sea lions haul

out at Point Bonita Cove as well as at Sea Lion Cove at Point Reyes National

Seashore (nps.gov/pore), about 55 miles to the north. The San Francisco garter

snake and its favorite meal, the California red-legged frog, haunt the wetlands

at Mori Point in Pacifica. Colossal redwoods dominate Muir Woods National

Monument, while fog-shrouded grassland, maritime chaparral and coastal scrubland

adapted to the distinctive Mediterranean climate accommodate a remarkable

assortment of endangered plants. Presidio clarkia, a delicate lavender-pink

evening primrose relative, has taken to the harsh mineral soil above the parking

lot at Inspiration Point in the Presidio in San Francisco. Stonecrop plants

sustain the San Bruno elfin butterfly, whose larvae are tended by ant au pairs,

and silver lupines nourish the iridescent mission blue butterfly.

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park (nps.gov/havo) boasts living marvels found

nowhere else on earth. Visitors can spot a showy Kamehameha butterfly by mamaki

trees, and admire one of Hawaii Island’s rarest plants, the hibiscuslike hau

kuahiwi; it was rescued from the brink of extinction by decades of painstaking

propagation, and now greets visitors by trail sign 11 in Kipuka Puaulu (Bird

Park). In all, the park hosts 26 endangered or threatened endemic plant species,

including the Mauna Loa silversword.

Five rare or critically endangered types of honeycreeper songbird persist at

higher altitudes, where they can evade mosquito-borne diseases. Hawaiian petrels

nest in lava tubes high on the slopes of Mauna Loa, while flocks of nene

(Hawaiian geese) honk as they pass overhead in the early morning and early

evening. Solitary Hawaiian monk seals rest on remote beaches, and backcountry

hikers may spot a hawksbill sea turtle nesting at Keauhou, Halape or Apua Point

from July through September.

10 Species Near Extinction

ALABAMA CAVEFISH (Speoplatyrhinus poulsoni)

Confined to underground pools in Key Cave National Wildlife Refuge, this rare

species is dependent on aquatic animals that feed on bat guano.

ALALA OR HAWAIIAN CROW (Corvus hawaiiensis)

The entire population survives in captive breeding programs at Keauhou Bird

Conservation Center and the Maui Bird Conservation Center in Hawaii.

BIG BEND GAMBUSIA (Gambusia gaigei)

A small fish reintroduced to three ponds in Big Bend National Park in Texas, its

main threats are habitat loss and predation by introduced sunfish and other

species.

COLUMBIA BASIN PYGMY RABBIT (Brachylagus idahoensis)

Conservationists are crossbreeding a small captive group with their close Idaho

relatives and gradually reintroducing the progeny to central Washington.

FLORIDA BONNETED BAT (Eumops floridanus)

It persists in scattered roosts in South Florida, threatened by habitat loss and

pesticides.

FRANCISCAN MANZANITA (Arctostaphylos hookeri ssp. franciscana)

A lone plant was spotted near the Golden Gate Bridge in 2009 and was relocated

to a more secure site.

MIAMI BLUE BUTTERFLY (Hemiargus thomasi ssp. bethunebakeri)

Scattered individuals are found within Key West National Wildlife Refuge in

Florida. Loss of coastal habitat, insecticides and poaching are threats.

OHA WAI (Clermontia peleana)

Presumed extinct for 90 years, this flowering plant was rediscovered in the

Kohola Mountains of Hawaii. Seeds are being collected for propagation.

RED WOLF (Canis rufus)

Driven to the brink by overhunting and habitat fragmentation, this wolf has a

wild population of about 100 in northeastern North Carolina.

WYOMING TOAD (Anaxyrus baxteri)

A fungal disease and predation have nearly wiped out the toad’s tiny population

in two counties. Captive breeding programs are trying to save it.

A Coast-to-Coast Guide to Endangered Species,

NYT,

13.5.2011,

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/15/

travel/endangered-species-travel-guide.html

Polar Bear

Is Made a Protected Species

May 15, 2008

The New York Times

By FELICITY BARRINGER

The polar bear, whose summertime Arctic hunting grounds have been greatly

reduced by a warming climate, will be placed under the protection of the

Endangered Species Act, Interior Secretary Dirk Kempthorne announced on

Wednesday.

But the long-delayed decision to list the bear as a threatened species may prove

less of an impediment to oil and gas industries along the Alaskan coast than

many environmentalists had hoped. Mr. Kempthorne also made it clear that it

would be “wholly inappropriate” to use the listing as a tool to reduce

greenhouse gases, as environmentalists had intended to do.

While giving the bear a few new protections — hunters may no longer import hides

or other trophies from bears killed in Canada, for instance — the Interior

Department added stipulations, seldom used under the act, that would allow oil

and gas exploration and development to proceed in areas where the bears live, as

long as the companies continue to comply with existing restrictions under the

Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Mr. Kempthorne said Wednesday in Washington that the decision was driven by

overwhelming scientific evidence that “sea ice is vital to polar bears’

survival,” and all available scientific models show that the rapid loss of ice

will continue. The bears use sea ice as a platform to hunt seals and as a

pathway to the Arctic coasts where they den. The models reflect varying

assumptions about how fast the concentration of greenhouse gases in the

atmosphere will increase.

In prepared remarks, the secretary, who earlier in his political life was a

strong opponent of the current Endangered Species Act, added, “This has been a

difficult decision.” He continued, “But in light of the scientific record and

the restraints of the inflexible law that guides me,” he made “the only decision

I could make.”

The Center for Biological Diversity, Greenpeace and the Natural Resources

Defense Council filed suit in 2005 to force a listing of the polar bear. The

center, based in Arizona, has been explicit about its hopes to use this — and

the earlier listing of two species of coral threatened by warming seas — as a

legal cudgel to attack proposed coal-fired power plants or other new sources of

carbon dioxide emissions.

But in both cases, the Bush administration has parried this legal thrust, saying

it had no obligation to address or try to mitigate the cause of the species’

decline — warming waters, in the case of the corals, or melting sea ice, in the

case of the bears — or the greenhouse-gas emissions from cars, trucks,

refineries, factories and power plants that contribute to both conditions.

On Wednesday, Mr. Kempthorne specifically ruled out that possibility, saying,

“When the Endangered Species Act was adopted in 1973, I don’t think terms like

‘climate change’ were part of our vernacular.”

The act, he said, “is not the instrument that’s going to be effective” to deal

with climate change.

Barton H. Thompson Jr., a law professor and director of the Woods Institute of

the Environment at Stanford University, said the decision reflected the

administration’s view that “there is no way, if your factory emits a greenhouse

gas, that we can say there is a causal connection between that emission and an

iceberg melting somewhere and a polar bear falling into the ocean.”

Few natural resource decisions have been as closely watched or been the subject

of such vehement disagreement within the Bush administration as this one,

according to officials in the Interior Department and others familiar with the

process.

After the department missed a series of deadlines, a federal judge ruled two

weeks ago that the decision had to be made by Thursday.

In recent days, some officials in the Interior Department speculated that the

office of Vice President Dick Cheney had tried to block the listing of the bear.

People close to these officials indicated that two separate documents — one

supporting the listing, and the other supporting a decision not to list the bear

— had been prepared for Mr. Kempthorne.

In an interview, Mr. Kempthorne and his chief of staff, Bryan Waidmann, said

they had not discussed the decision with anyone in the vice president’s office,

though they did not dispute that two documents had been made available for the

secretary’s signature this week.

“Let’s say I had my options available,” Mr. Kempthorne said.

The provision of the act that the Interior Department is using to lighten the

regulatory burden that the listing imposes on the oil and gas industry — known

as a 4(d) rule — was intended to permit flexibility in the management of

threatened species, as long as the chances of conservation of the species would

be enhanced, or at least not diminished.

Kassie Siegel, a lawyer for the Center for Biological Diversity, said the

listing decision was an acknowledgment of “global warming’s urgency” but would

have little practical impact on protecting polar bears.

“The administration acknowledges the bear is in need of intensive care,” Ms.

Siegel said. “The listing lets the bear into the hospital, but then the 4(d)

rule says the bear’s insurance doesn’t cover the necessary treatments.”

The science on polar bears in a warming climate is nuanced, which allowed the

administration to shape its decision the way it did. Over all, scientists agree

that rising temperatures will reduce Arctic ice and stress polar bears, which

prefer seals they hunt on the floes. But few foresee the species vanishing

entirely for a century and likely longer.

There are more than 25,000 bears in the Arctic, 15,500 of which roam within

Canada’s territory. A scientific study issued last month by a Canadian group

established to protect wildlife said that 4 of 13 bear populations would most

likely decline by more than 30 percent over the next 36 years, while the others

would remain stable or increase.

M. Reed Hopper of the Pacific Legal Foundation, a property-rights group based in

Sacramento, called the decision to list the polar bear “unprecedented” and said

his group would sue the Interior Department over the decision.

“Never before has a thriving species been listed” under the Endangered Species

Act, he said, “nor should it be.”

John Baird, the environment minister for Canada, said Wednesday that the

government would adopt an independent scientific panel’s recommendation to

declare polar bears a species “of special concern,” a lower designation than

endangered, and he promised to take other unspecified actions.

Management of the bear populations is the responsibility of Canadian provinces

and territories. The territorial government of Nunavut, which is home to upward

of 15,000 polar bears, had campaigned against new United States protections for

the bear, largely because of worries that the lucrative local bear hunts by

residents of the United States would stop when trophy skins could no longer be

brought home.

Andrew C. Revkin and Ian Austen contributed reporting.

Polar Bear Is Made a Protected Species,

NYT,

15.5.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/15/us/15polar.html

Editorial

Until All the Fish Are Gone

January 21, 2008

The New York Times

Scientists have been warning for years that overfishing is degrading the health

of the oceans and destroying the fish species on which much of humanity depends

for jobs and food. Even so, it would be hard to frame the problem more

dramatically than two recent articles in The Times detailing the disastrous

environmental, economic and human consequences of often illegal industrial

fishing.

Sharon LaFraniere showed how mechanized fishing fleets from the European Union

and nations like China and Russia — usually with the complicity of local

governments — have nearly picked clean the oceans off Senegal and other

northwest African countries. This has ruined coastal economies and added to the

surge of suddenly unemployed migrants who brave the high seas in wooden boats

seeking a new life in Europe, where they are often not welcome.

The second article, by Elisabeth Rosenthal, focused on Europe’s insatiable

appetite for fish — it is now the world’s largest consumer. Having overfished

its own waters of popular species like tuna, swordfish and cod, Europe now

imports 60 percent of what it consumes. Of that, up to half is contraband, fish

caught and shipped in violation of government quotas and treaties.

The industry, meanwhile, is organized to evade serious regulation. Big factory

ships from places like Europe, China, Korea and Japan stay at sea for years at a

time — fueling, changing crews, unloading their catch on refrigerated vessels.

The catch then enters European markets through the Canary Islands and other

ports where inspection is minimal. After that, retailers and consumers neither

ask nor care where the fish came from, or whether, years from now, there will be

any fish at all.

From time to time, international bodies try to do something to slow overfishing.

The United Nations banned huge drift nets in the 1990s, and recently asked its

members to halt bottom trawling, a particularly ruthless form of industrial

fishing, on the high seas. Last fall, the European Union banned fishing for

bluefin tuna in the eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean, where bluefin have been

decimated.

The institution with the most potential leverage is the World Trade

Organization. Most of the world’s fishing fleets receive heavy government

subsidies for boat building, equipment and fuel, America’s fleet less so than

others. Without these subsidies, which amount to about $35 billion annually,

fleets would shrink in size and many destructive practices like bottom trawling

would become uneconomic.

The W.T.O. has never had a reputation for environmental zeal. But knowing that

healthy fisheries are important to world trade and development, the group has

begun negotiating new trade rules aimed at reducing subsidies. It produced a

promising draft in late November, but there is no fixed schedule for a final

agreement.

The world needs such an agreement, and soon. Many fish species may soon be so

depleted that they will no longer be able to reproduce themselves. As 125 of the

world’s most respected scientists warned in a letter to the W.T.O. last year,

the world is at a crossroads. One road leads to tremendously diminished marine

life. The other leads to oceans again teeming with abundance. The W.T.O. can

help choose the right one.

Until All the Fish Are Gone, NYT, 21.1.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/21/opinion/21mon1.html

Op-Ed Contributor

The Vanishing Man of the Forest

January 6, 2007

The New York Times

By BIRUTE MARY GALDIKAS

ONCE again, I am driving, under the blazing

equatorial sun, down an uncomfortable, rutty relic of a road into the interior

of central Borneo. With me are two uniformed police men, one armed with a

machine gun. The landscape is bleak, no trees, no shade as far as the eye can

see. Our mission is to confiscate orangutan orphans whose mothers have been

killed as a result of the sweeping forest clearance taking place throughout

Borneo.

Many years ago, Louis Leakey, the great paleo-anthropologist whose work at

Olduvai Gorge and other sites in East Africa revolutionized our knowledge of

human origins, encouraged me to study wild orangutans — just as he had

encouraged Jane Goodall to study chimpanzees and Dian Fossey to study gorillas.

Later, he laughingly called us the “trimates,” or the three primates.

Orangutans are not as well known as chimpanzees and gorillas. But like their

African cousins, orangutans are great apes, our closest living relatives in the

animal kingdom, and the most intelligent animals, with the exception of humans,

to have evolved on land. Orangutans are reclusive, semi-solitary, quiet, highly

arboreal and red, facts that come as a surprise to some people. Their name is

derived from the Malay words “orang hutan,” which literally mean “person of the

forest.” And it is the orangutan’s profound connection to the forest that is

driving it to extinction.

Without forests, orangutans cannot survive. They spend more than 95 percent of

their time in the trees, which, along with vines and termites, provide more than

99 percent of their food. Two forests form their only habitat, and they are the

tropical rain forests of Borneo and Sumatra.

Sumatra is exclusively Indonesian, as is the two thirds of the island of Borneo

known as Kalimantan. That places 80 to 90 percent of the orangutan population,

which numbers only 40,000 to 50,000, in Indonesia, with the remainder in

Malaysian Borneo. What happens in Indonesia, particularly Kalimantan, will

determine the orangutan’s future.

When I first arrived in Central Kalimantan in 1971, orangutans were already

endangered because of poaching (for the pet trade and for the cooking pot) and

deforestation (by loggers and by villagers making way for gardens and rice

fields).

But it was all relatively small-time. The forests of Kalimantan were vast —

Indonesia’s are the second largest tropical rain forests in the world, after

Brazil’s — and forest conversion rates small. People still used axes and saws to

cut down trees and traveled by dugout canoes or small boats with inboard

engines.

I went straight to work, beginning a wild orangutan study that continues to this

day, and establishing an orangutan rehabilitation program, the first in

Kalimantan, which has returned more than 300 ex-captive orangutans to the wild.

But the wild is increasingly difficult to find. In the late 1980s, as it entered

the global economy, Indonesia decided to become a major producer and exporter of

palm oil, pulp and paper. Before this, the government had endorsed selective

logging. Now vast areas of forest were slated for conversion to plantations to

grow trees for palm oil and paper production. Monster-sized bulldozers,

replacing the chain saws of the early logging boom, tore up the forest,

clear-cutting as many as 250,000 acres at once for palm oil plantations.

At the same time, the price of wood, particularly the valuable hardwoods that

grow in Indonesia’s rain forests and fetch a high price on the black market,

increased. Illegal logging became rampant, even in national parks and reserves.

While illegal logging degrades the forest, plantations absolutely destroy it.

And the destruction is not only immediate, but also long-term. Forest-clearing

leaves huge amounts of dry branches and other wood litter on forest floors; a

small spark can ignite enormous forest fires, particularly in times of drought.

During the 1997 El Niño drought, approximately 25 million acres, an area about

half the size of Oklahoma, burned in Indonesia. Thousands of orangutans died.

Indonesia has achieved its goal of becoming one of the two largest palm-oil

producers and exporters in the world. But at what cost? At least half of the

world’s wild orangutans have disappeared in the last 20 years; biologically

viable populations of orangutans have been radically reduced in size and number;

and 80 percent of the orangutan habitat has either been depopulated or totally

destroyed. The trend shows no sign of abating: government maps of future planned

land use show more of the same, on an increasing scale.

•

We’re back in the jeep. The police view the trip inland as a success. They

confiscated five orangutans and one woman volunteered her crab-eating macaque,

an unprotected species. Two of the orangutan owners, both women, shed tears, but

we invited them to visit their “pets” at the Orangutan Foundation

International’s Care Center and Quarantine, where they will be rehabilitated and

eventually released to the wild.

I am pleased to think that five more orphan orangutans will once again feel the

branches and leaves under their feet as they swing through the trees. Yet I am

somewhat melancholy. The fragile forests that make orangutan life possible are

fast disappearing. Where, I wonder, are the billionaire philanthropists and the

international policies that will prevent orangutans — and all great apes — from

going extinct?

Indonesia is a vast, densely populated country where millions live in or near

poverty. The temptation to exploit natural resources to feed people today, never

mind tomorrow, and to expand the economy, is great. And the plantations are but

one example. Surface-mining of gold in the alluvial fans of white sand has been

practiced for two decades, leaving virtual moonscapes near the National Park

where I work. Now zircon mining has entrenched itself all over Central

Kalimantan, with each zircon mine obliterating 1,000 acres of rain forest. Two

years ago nobody, myself included, even knew what zircon was.

The international community must recognize that it has some responsibility for

what happens to the great rain forests of Indonesian Borneo. Foreign investment

in local development programs needs to be expanded. Village level projects, like

the one financed by the United States Agency for International Development and

run by Boston-based World Education near where I work, have empowered farmers,

strengthened village economies and employed local people, giving them a stake in

preserving the forest.

We need more of these programs. Indonesia could also impose a special tax on

companies that profit from rain forest destruction, with the revenues dedicated

to forest and orangutan conservation. Proper labeling of palm oil content could

allow a consumer boycott of soap, crackers, cookies and other products that

contain it. Finally, Indonesia needs to be more vigorous in enforcing the

excellent laws it already has to protect its forests.

When I arrived in 1971, Borneo was almost a Garden of Eden, the most remote

place on earth. Now it has been drawn into the global economy, one government

decision, one business plan at a time. But the destruction of Borneo’s forests

and the extinction of the orangutans are not inevitable. It is possible to

protect our ancient heritage and closest of kin — one orangutan, one national

park, one piece of irreplaceable forest at a time. We only need to decide to do

it.

Birute Mary Galdikas is president

and co-founder

of Orangutan Foundation

International

in Los Angeles

and a professor

at Simon Fraser University in

British Columbia.

The

Vanishing Man of the Forest,

NYT, 6.1.2007,

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/06/

opinion/06galdikas.html

Study Sees

‘Global Collapse’

of Fish

Species

November 3, 2006

The New York Times

By CORNELIA DEAN

If fishing around the world continues at its

present pace, more and more species will vanish, marine ecosystems will unravel

and there will be “global collapse” of all species currently fished, possibly as

soon as midcentury, fisheries experts and ecologists are predicting.

The scientists, who report their findings today in the journal Science, say it

is not too late to turn the situation around. As long as marine ecosystems are

still biologically diverse, they can recover quickly once overfishing and other

threats are reduced, the researchers say.

But improvements must come quickly, said Boris Worm of Dalhousie University in

Nova Scotia, who led the work. Otherwise, he said, “we are seeing the bottom of

the barrel.”

“When humans get into trouble they are quick to change their ways,” he

continued. “We still have rhinos and tigers and elephants because we saw a clear

trend that was going down and we changed it. We have to do the same in the

oceans.”

The report is one of many in recent years to identify severe environmental

degradation in the world’s oceans and to predict catastrophic loss of fish

species. But experts said it was unusual in its vision of widespread fishery

collapse so close at hand.

The researchers drew their conclusion after analyzing dozens of studies, along

with fishing data collected by the United Nations Food and Agricultural

Organization and other sources. They acknowledge that much of what they are

reporting amounts to correlation, rather than proven cause and effect. And the

F.A.O. data have come under criticism from researchers who doubt the reliability

of some nations’ reporting practices, Dr. Worm said.

Still, he said in an interview, “there is not a piece of evidence” that

contradicts the dire conclusions.

Jane Lubchenco, a fisheries expert at Oregon State University who had no

connection with the work, called the report “compelling.”

“It’s a meta analysis and there are challenges in interpreting those,” she said

in an interview, referring to the technique of collective analysis of disparate

studies. “But when you get the same patterns over and over and over, that tells

you something.”

But Steve Murawski, chief scientist of the Fisheries Service of the National

Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, said the researchers’ prediction

of a major global collapse “doesn’t gibe with trends that we see, especially in

the United States.”

He said the Fisheries Service considered about 20 percent of the stocks it

monitors to be overfished. “But 80 percent are not, and that trend has not

changed substantially,” he said, adding that if anything, the fish situation in

American waters was improving. But he conceded that the same cannot necessarily

be said for stocks elsewhere, particularly in the developing world.

Mr. Murawski said the Bush administration was seeking to encourage international

fishery groups to consider adopting measures that have been effective in

American waters.

Twelve scientists from the United States, Canada, Sweden and Panama contributed

to the work reported in Science today.

“We extracted all data on fish and invertebrate catches from 1950 to 2003 within

all 64 large marine ecosystems worldwide,” they wrote. “Collectively, these

areas produced 83 percent of global fisheries yields over the past 50 years.”

In an interview, Dr. Worm said, “We looked at absolutely everything — all the

fish, shellfish, invertebrates, everything that people consume that comes from

the ocean, all of it, globally.”

The researchers found that 29 percent of species had been fished so heavily or

were so affected by pollution or habitat loss that they were down to 10 percent

of previous levels, their definition of “collapse.”

This loss of biodiversity seems to leave marine ecosystems as a whole more

vulnerable to overfishing and less able to recover from its effects, Dr. Worm

said. It results in an acceleration of environmental decay, and further loss of

fish.

Dr. Worm said he analyzed the data for the first time on his laptop while he was

overseeing a roomful of students taking an exam. What he saw, he said, was “just

a smooth line going down.” And when he extrapolated the data into the future “to

see where it ends at 100 percent collapse, you arrive at 2048.”

“The hair stood up on the back of my neck and I said, ‘This cannot be true,’ ”

he recalled. He said he ran the data through his computer again, then did the

calculations by hand. The results were the same.

“I don’t have a crystal ball and I don’t know what the future will bring, but

this is a clear trend,” he said. “There is an end in sight, and it is within our

lifetimes.”

Dr. Worm said a number of steps could help turn things around.

Even something as simple as reducing the number of unwanted fish caught in nets

set for other species would help, he said. Marine reserves would also help, he

said, as would “doing away with horrendous overfishing where everyone agrees

it’s a bad thing; or if we banned destructive fishing in the most sensitive

habitats.”

Josh Reichert, who directs the environmental division of the Pew Charitable

Trusts, called the report “a kind of warning bell” for people and economies that

depend on fish.

But predicting a global fisheries collapse by 2048 “assumes we do nothing to fix

this,” he said, “and shame on us if that were to be the case.”

Study

Sees ‘Global Collapse’ of Fish Species,

NYT,

3.11.2006,

https://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/03/

science/03fish.html

Explore more on these topics

Anglonautes > Vocapedia

Earth > wildlife

Earth > climate change, global warming

Earth > geography,

animals, wildlife,

endangered and extinct species,

resources,

agriculture / farming, gardening,

population, waste, pollution,

global warming, climate change,

weather, extreme weather, disasters,

climate action, activists

|