|

History

>

2008 > USA > Economy (VII)

Lewis Scott

Editorial cartoon

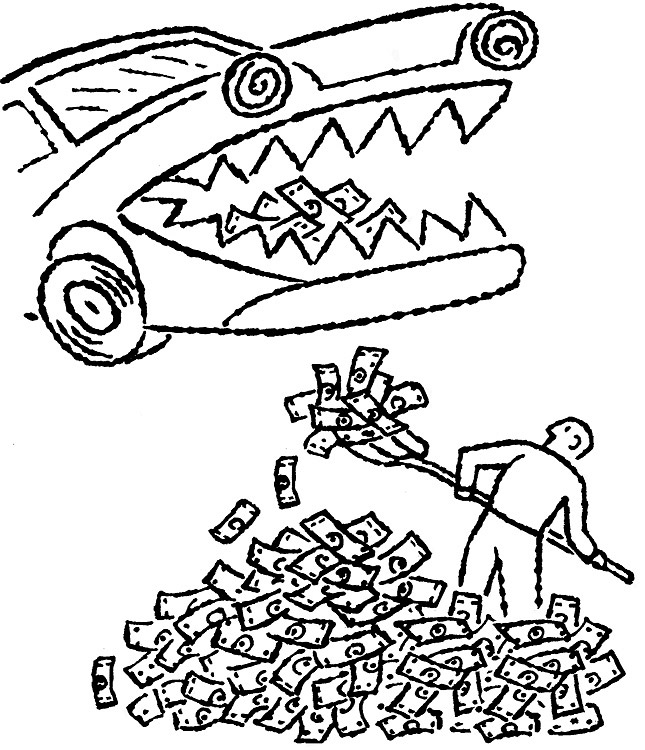

Getting There, Without Going Broke

NYT July 6, 2008

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/06/opinion/l06gas.html

A Hidden Toll on Employment:

Cut to Part Time

July 31, 2008

The New York Times

By PETER S. GOODMAN

The number of Americans who have seen their full-time jobs

chopped to part time because of weak business has swelled to more than 3.7

million — the largest figure since the government began tracking such data more

than half a century ago.

The loss of pay has become a primary source of pain for millions of American

families, reinforcing the downturn gripping the economy. Paychecks are shrinking

just as home prices plunge and gas prices soar, furthering the austerity across

the nation.

“I either stop eating, or stop using anything I can,” said Marvin L. Zinn, a

clerk at a Walgreens drugstore in St. Joseph, Mich., who has seen his take-home

pay drop to about $550 every two weeks from about $650, as his weekly hours have

dropped to 37.5 from 44 in recent months.

Mr. Zinn has run up nearly $2,000 in credit card debt to buy food. He has put

off dental work. He no longer attends church, he said, “because I can’t afford

to drive.”

On the surface, the job market is weak but hardly desperate. Layoffs remain less

frequent than in many economic downturns, and the unemployment rate is a

relatively modest 5.5 percent. But that figure masks the strains of those who

are losing hours or working part time because they cannot find full-time work —

a stealth force that is eroding American spending power.

All told, people the government classifies as working part time involuntarily —

predominantly those who have lost hours or cannot find full-time work — swelled

to 5.3 million last month, a jump of greater than 1 million over the last year.

These workers now amount to 3.7 percent of all those employed, up from 3 percent

a year ago, and the highest level since 1995.

“This increase is startling,” said Steve Hipple, an economist at the Labor

Department.

The loss of hours has been affecting men in particular — and Hispanic men more

so. Among those who were forced into part-time work from the spring of 2007 to

the spring of 2008, 73 percent were men and 35 percent were Hispanic.

Some 28 percent of the jobs affected were in construction, 14 percent in retail

and 13 percent in professional and business services, according an analysis by

Mr. Hipple.

“The unemployment rate is giving you a misleading impression of some of the

adjustments that are taking place,” said John E. Silvia, chief economist of

Wachovia in Charlotte. “Hours cut is a big deal. People still have a job, but

they are losing income.”

Many experts see the swift cutback in hours as a precursor of a more painful

chapter to come: broader layoffs. Some struggling companies are holding on to

workers and cutting shifts while hoping to ride out hard times. If business does

not improve, more extreme measures could follow.

“The change in working hours is the canary in the coal mine,” said Susan J.

Lambert of the University of Chicago, a professor of social service

administration and an expert in low-wage employment. “First you see hours get

short, and eventually more people will get laid off.”

For the last decade, Ron Temple has loaded and unloaded bags for United Airlines

in Denver, earning more than $20 an hour, plus generous health and flight

benefits. On July 6, as management grappled with the rising cost of fuel, Mr.

Temple and 150 other people in Denver were offered an unpalatable set of

options: they could transfer to another city, go on furlough without pay and

hope to be rehired, or stay on at reduced hours.

Mr. Temple and his wife say they cannot envision living outside Colorado, and

they probably could not sell their house. Similar homes are now selling for

about $180,000, while they owe the bank $203,000.

So Mr. Temple took the third option. He reluctantly traded in his old shift — 3

p.m. to midnight — for a shorter stint from 5:30 p.m. to 10 p.m. He gave up

benefits like paid lunches and overtime. His take-home pay shrunk to $570 every

two weeks from about $1,350, he said.

Mr. Temple’s wife, Ali, works as an aide at a cancer clinic, bringing home

nearly $1,000 every two weeks, he said. But collectively, they earn less than

half of what they did.

Suddenly, they are having trouble making their $1,753 monthly mortgage payment,

he said. They are relying on credit cards to pay the bills, running up balances

of $2,700 so far. Gone are their dinners at the Outback Steakhouse. Mr. Temple

recently bought cheap, generic groceries from a church that sells them to people

in need.

“That’s the first time in my life I’ve had to do that,” he said. “We are cutting

back in every way.”

Mr. Temple has been searching for another job, applying for a cashier’s position

at Safeway and a clerk’s job at Home Depot, among others. But the market is

lean.

“I’ve applied more than 20 times, and I haven’t had a single call back,” he

said.

His search is constrained by the high price of gas. “I can’t afford to go drive

my truck around and look for a job,” he said.

So Mr. Temple has done his search online — until he fell behind on the bills,

and the local telephone company cut off Internet service. On a recent day, he

bicycled to a Starbucks coffee shop with his laptop for the free connection.

The growing ranks of involuntary part-timers reflect the sophisticated fashion

through which many American employers have come to manage their payrolls, say

experts.

In decades past, when business soured, companies tended to resort to mass

layoffs, hiring people back when better times returned. But as high technology

came to permeate American business, companies have grown reluctant to shed

workers. Even the lowest-wage positions in retail, fast food, banking or

manufacturing require computer skills and a grasp of a company’s systems.

Several months of training may be needed to get a new employee up to speed.

“Companies today would rather not go through the process of dumping someone and

hiring them back,” said Dean Baker, co-director of the Center for Economic and

Policy Research in Washington. “Firms are going to short shifts rather than just

laying people off.”

More part-time and fewer full-time workers also allows companies to save on

health care costs. Only 16 percent of retail workers receive health insurance

through their employer, while more than half of full-time workers are covered,

according to an analysis by Ms. Lambert, the University of Chicago employment

expert.

The trend toward cutting hours in a downturn lessens the pain for workers in one

regard: it moderates layoffs. Many companies now strive to keep payrolls large

enough to allow them to easily adjust to swings in demand, adding working hours

without having to hire when business grows.

But that also sows vulnerability, heightening the possibility that hours are cut

when the economy slows and demand for goods and services dries up.

“There’s a lot of people at risk in the economy when they keep the headcount

high and they only have so many hours to distribute,” Ms. Lambert said. “It

really is a trade-off for society.”

Goodyear Tire has in recent months idled work for a few days at a time at many

of it factories, as the company adjusts to weakening demand. At one plant in

Gadsden, Ala., workers expect they will soon lose a week’s wages to another

slowdown — something Goodyear would neither confirm nor deny.

“People are scared,” said Dennis Battles, president of the local branch of the

United Steelworkers union, which represents about 1,350 workers there. “The cost

of gas, the cost of food and everything else is extremely high. It takes every

penny you make. And once it starts, when’s it going to quit? What’s going to

happen next month?”

A Hidden Toll on

Employment: Cut to Part Time, NYT, 31.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/31/business/economy/31jobs.html?hp

Bush Signs Housing Bill

July 30, 2008 8:08 a.m.

Associated Press

WASHINGTON -- President George W. Bush on Wednesday signed a massive housing

bill intended to provide mortgage relief for 400,000 struggling U.S. homeowners

and to stabilize financial markets.

Mr. Bush signed the bill without any fanfare or signing ceremony, affixing his

signature to the measure he once threatened to veto in the White House's Oval

Office in the early morning hours. He was surrounded by top administration

officials, including Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson and Housing Secretary

Steve Preston.

"We look forward to put in place new authorities to improve confidence and

stability in markets," White House spokesman Tony Fratto said. He added that the

Federal Housing Administration would begin right away to implement new policies

"intended to keep more deserving American families in their homes."

The measure, regarded as the most significant U.S. housing legislation in

decades, lets homeowners who cannot afford their payments refinance into more

affordable government-backed loans rather than losing their homes. It offers a

temporary financial lifeline to troubled mortgage companies Fannie Mae and

Freddie Mac, and tightens controls over the two government-sponsored businesses.

The House of Representatives passed the bill a week ago; the Senate voted

Saturday to send it to the president.

Mr. Bush didn't like the version emerging from Congress, and initially said he

would veto it, particularly over a provision containing $3.9 billion in

neighborhood grants. He contended the money would benefit lenders who helped

cause the mortgage meltdown, encouraging them to foreclose rather than work with

borrowers. But he withdrew that threat early last week, saying hurting

homeowners couldn't wait -- and even blaming the Democratic Congress' delays in

action for forcing an imperfect solution.

Meanwhile, many Republicans, particularly those from areas hit hardest by

housing woes, were eager to get behind a housing rescue as they looked ahead to

tough re-election contests. Mr. Paulson's request for the emergency power to

rescue Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac helped push through the measure. So did the

creation of a regulator with stronger reins on the government-sponsored

companies, which Republicans have long sought.

Democrats won cherished priorities in the bargain: the aid for homeowners, a

permanent affordable housing fund financed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and

the $3.9 billion in neighborhood grants.

Bush Signs Housing

Bill, WSJ, 30.7.2008,

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB121741699750696667.html?mod=hpp_us_whats_news

Bush signs sweeping housing bill

30 July 2008

USA Today

WASHINGTON (AP) — President Bush has signed a massive housing bill intended

to provide mortgage relief for 400,000 struggling U.S. homeowners and stabilize

financial markets.

A White House spokesman said Bush signed the measure Wednesday to "improve

confidence and stability in markets and to provide better oversight of Fannie

Mae and Freddie Mac."

The measure offers a temporary financial lifeline to troubled mortgage companies

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and tightens controls over the two

government-sponsored businesses.

It is regarded as the most significant U.S. housing legislation in decades. It

lets homeowners who cannot afford their payments refinance into more affordable

government-backed loans rather than losing their homes.

Bush signs sweeping

housing bill, UT, 30.7.2008,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/washington/2008-07-30-bush-housing_N.htm

Energy Prices

Are Bright Sliver in Grim Economy

July 30, 2008

The New York Times

By JAD MOUAWAD

The sharp drop in energy prices since the beginning of the

month is turning into a rare bright spot in a bleak economic landscape.

For the moment, at least, fears of a prolonged energy shock seem to have

subsided a bit.

Oil has fallen more than $23 a barrel, or 16 percent, since peaking on July 3.

Gasoline has slipped below $4 a gallon and is dropping fast as Americans drive

less. Natural gas prices, which had risen the fastest this year as traders

anticipated a hot summer, have fallen 33 percent since the beginning of the

month.

Crude oil prices extended their decline on Tuesday, falling 2.5 percent, to

$122.19 a barrel, their lowest level since the beginning of May. This helped

spur a broad rally in the stock market, with all major indexes rising more than

2 percent. But stock markets still remain close to the lows of earlier this

month, when they officially entered bear-market territory.

The declines in energy costs come after an equally sharp correction in the

prices of many agricultural commodities like corn, wheat and rice, which took

place a few weeks ago. These moves suggest to economists that global markets, in

a near-panic early this year to find prices high enough to allocate scarce

supplies, overshot the mark and bid prices too high.

Commodity prices remain extraordinarily high by historical standards. Gasoline

and particularly diesel remain especially costly despite the recent fall in

crude oil prices, partly because of strong demand from emerging markets that

continue to subsidize the retail sale of these fuels to consumers. But with the

economy weakening amid a housing crisis and a credit squeeze that show few signs

of improving, many traders have begun to believe demand for oil and other

commodities will soften worldwide. Investors became net sellers in the oil

market last week for the first time since mid-February 2007, according to

Barclays Capital.

“The market’s expectations have changed very rapidly and unexpectedly,” said

Edward Morse, the chief energy economist at Lehman Brothers. “The market went

out of control on the upside. But market participants realized there was much

more demand destruction than had been thought even a month ago, that inventories

are building up quickly, and that, in fact, more supplies are coming onto the

market.”

As a result of looser market fundamentals, many analysts believe energy prices

could keep falling through the end of the year. The president of the OPEC oil

cartel, Chakib Khelil, said Tuesday that oil might drop as low as $70 a barrel.

Whether that actually happens will depend on the course of the American economy

and its impact on the rest of the world. How long will the American slowdown

last and what effect will it have on emerging markets like China, which have

accounted for the bulk of the growth in oil demand?

Many experts warn that a hurricane hitting the oil-producing region of the Gulf

Coast or renewed tensions in the Persian Gulf could easily push prices back up

again, quickly.

Only a few weeks ago, Israel conducted war games and Iran tested new missiles,

renewing fears of a flare-up in the Middle East, and pushing oil prices to a

record of $145.29 a barrel. The recent shift in American policy regarding Iran,

with an emphasis on diplomacy, helped deflate some of the geopolitical risk

premium that had been built into oil prices.

“The one piece of good news we’ve had recently has been the drop in oil prices,”

said Bernard Baumohl, the chief global economist at the Economic Outlook Group.

“But there is nothing that tells us with any certainty that this decline can be

sustained. Just as abruptly as they have fallen, oil prices can rebound because

of geopolitical factors.”

Gasoline peaked at a nationwide average of $4.11 a gallon on July 17. Since

then, retail gasoline prices have been falling briskly, to a nationwide average

of $3.94 on Tuesday, according to AAA, the automobile group. Still, that is

$1.05 a gallon higher than at the same time last year, when gasoline sold for

$2.89 a gallon.

Natural gas settled at $9.22 a thousand cubic feet on Tuesday, down from a high

of about $13.58 at the beginning of the month, as a cooler-than-expected summer

helped curb the use of gas to generate electricity. That has led to a build-up

of commercial inventories.

The drop in oil prices has come as gasoline demand in the United States fell

sharply in recent months, thanks to Americans cutting back on their driving.

Gasoline consumption fell 3.6 percent in the week ending July 18, compared with

the year-earlier period, according to the Energy Department. Americans drove 9.6

billion fewer miles in May compared with the same period last year, a 3.7

percent decline and the biggest-ever drop at that time of year, the

Transportation Department said on Monday.

“People are waking up to the fact that prices have an impact on demand and that

what happens in the U.S. gasoline market has a worldwide impact,” said Daniel

Yergin, the chairman of Cambridge Energy Research Associates, a consulting firm.

The United States is the world’s largest oil consumer, and its gas market alone

is bigger than the entire Chinese oil market, he said.

“As a result of the economic slowdown and high prices, we’ve probably seen the

peak in American gasoline demand, at least for some years,” he said.

Americans remain unhappy about the state of the economy. But consumer confidence

rose slightly this month compared with last, according to a report released on

Tuesday by the Conference Board, a private research group. That was mainly

because of the declining gasoline prices, said Ian Shepherdson, the chief United

States economist at High Frequency Economics.

One big question is what will happen to Chinese oil demand.

China has been the biggest driver of global energy demand in recent years,

experts said. From 2000 to 2007, China’s energy demand grew by 65 percent,

contributing to a 12 percent jump in global oil demand. In that period, China

accounted for a third of the total increase in oil consumption around the world.

This year, Chinese oil demand is expected to grow by 5.6 percent, thanks mostly

to increases in gasoline and diesel consumption. This growth would account for

nearly half of the rise in oil consumption worldwide, which is expected to reach

nearly 900,000 barrels a day, according to the International Energy Agency.

But that too may be changing, some economists said.

“We have seen the economies of emerging countries, like China, India, and Brazil

begin to slow down,” Mr. Baumohl said. “That should begin to soften the price of

oil.”

Kate Galbraith contributed reporting.

Energy Prices Are

Bright Sliver in Grim Economy, NYT, 30.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/30/business/30crude.html

Home Prices Fall in May;

Consumer Confidence Is Flat

July 30, 2008

The New York Times

By MICHAEL M. GRYNBAUM

Two trouble spots in the economy showed little sign of

improvement in the last few months, as home prices fell again in May and

consumer confidence stagnated in July, according to a pair of reports out

Tuesday.

Home prices, already falling at the steepest rate in two decades, tumbled again

in May, according to the Case-Shiller index, a widely watched survey that

measures prices in 20 major metropolitan areas.

Prices were down 15.8 percent from May 2007, including a 0.9 percent one-month

drop in May alone. The 10-city price index, which dates to 1988, dropped 16.9

percent, its sharpest decline on record.

All 20 cities measured by the index showed annual declines in home values, and

10 cities have suffered double-digit percentage declines in the last year. Miami

and Las Vegas have fared the worst, with prices in each city dropping more than

28 percent since May 2007.

There were some signs that the decline has started to abate. Prices in seven

regions, including Boston, Dallas and Charlotte, improved in May, some for the

second straight month. Boston, for example, was up 1.05 percent in May, though

values are still 6.2 percent below where they were a year prior.

The report “does seem to suggest the rate of decline of existing home prices is

slowing,” Ian Shepherdson of High Frequency Economics wrote in a note. “To be

sure, prices are still falling very rapidly, and there is no prospect of any

rebound this year and probably next, but a slower rate of fall is welcome

nonetheless.”

Las Vegas, Miami and Phoenix had the sharpest declines in May, with Miami losing

3.6 percent. The city recorded a 28.3 percent price drop for the last 12 months.

Another month of falling home values may continue to put pressure on investors

who are concerned the housing crisis is fueling the credit problems on Wall

Street. Last week, a dip in sales of newly built homes helped lead to a sharp

decline in the stock market.

In a separate report on Tuesday, the Conference Board, a private research group,

said that Americans remained unhappy about the state of their economy in July,

though their confidence did not change markedly from a month prior.

The group’s consumer confidence index rose to 51.9 from 51 in June, and a

measure of expectations about the economy’s prospects rose to 43 from 41.4.

Those figures are historically very low.

“It is not a particularly good sign that consumer confidence and sentiment

levels remain as low as they are, even after almost $100 billion of tax rebates

have hit consumer’s wallets in the past several months,” Joshua Shapiro, the

chief domestic economic at MFR, said in a note.

The Conference Board sends its questionnaire to 5,000 households.

Home Prices Fall in

May; Consumer Confidence Is Flat, NYT, 30.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/30/business/economy/30econ.html?hp

OPINION

Obamanomics Is a Recipe for Recession

July 29, 2008

Page A17

The Wall Street Journal

By MICHAEL J. BOSKIN

What if I told you that a prominent global political figure in

recent months has proposed: abrogating key features of his government's

contracts with energy companies; unilaterally renegotiating his country's

international economic treaties; dramatically raising marginal tax rates on the

"rich" to levels not seen in his country in three decades (which would make them

among the highest in the world); and changing his country's social insurance

system into explicit welfare by severing the link between taxes and benefits?

The first name that came to mind would probably not be Barack

Obama, possibly our nation's next president. Yet despite his obvious general

intelligence, and uplifting and motivational eloquence, Sen. Obama reveals this

startling economic illiteracy in his policy proposals and economic

pronouncements. From the property rights and rule of (contract) law foundations

of a successful market economy to the specifics of tax, spending, energy,

regulatory and trade policy, if the proposals espoused by candidate Obama ever

became law, the American economy would suffer a serious setback.

To be sure, Mr. Obama has been clouding these positions as he heads into the

general election and, once elected, presidents sometimes see the world

differently than when they are running. Some cite Bill Clinton's move to the

economic policy center following his Hillary health-care and 1994 Congressional

election debacles as a possible Obama model. But candidate Obama starts much

further left on spending, taxes, trade and regulation than candidate Clinton. A

move as large as Mr. Clinton's toward the center would still leave Mr. Obama on

the economic left.

Also, by 1995 the country had a Republican Congress to limit President Clinton's

big government agenda, whereas most political pundits predict strengthened

Democratic majorities in both Houses in 2009. Because newly elected presidents

usually try to implement the policies they campaigned on, Mr. Obama's proposals

are worth exploring in some depth. I'll discuss taxes and trade, although the

story on his other proposals is similar.

First, taxes. The table nearby demonstrates what could happen to marginal tax

rates in an Obama administration. Mr. Obama would raise the top marginal rates

on earnings, dividends and capital gains passed in 2001 and 2003, and phase out

itemized deductions for high income taxpayers. He would uncap Social Security

taxes, which currently are levied on the first $102,000 of earnings. The result

is a remarkable reduction in work incentives for our most economically

productive citizens.

The top 35% marginal income tax rate rises to 39.6%; adding the state income

tax, the Medicare tax, the effect of the deduction phase-out and Mr. Obama's new

Social Security tax (of up to 12.4%) increases the total combined marginal tax

rate on additional labor earnings (or small business income) from 44.6% to a

whopping 62.8%. People respond to what they get to keep after tax, which the

Obama plan reduces from 55.4 cents on the dollar to 37.2 cents -- a reduction of

one-third in the after-tax wage!

Despite the rhetoric, that's not just on "rich" individuals. It's also on a lot

of small businesses and two-earner middle-aged middle-class couples in their

peak earnings years in high cost-of-living areas. (His large increase in energy

taxes, not documented here, would disproportionately harm low-income Americans.

And, while he says he will not raise taxes on the middle class, he'll need many

more tax hikes to pay for his big increase in spending.)

On dividends the story is about as bad, with rates rising from 50.4% to 65.6%,

and after-tax returns falling over 30%. Even a small response of work and

investment to these lower returns means such tax rates, sooner or later, would

seriously damage the economy.

On economic policy, the president proposes and Congress disposes, so presidents

often wind up getting the favorite policy of powerful senators or congressmen.

Thus, while Mr. Obama also proposes an alternative minimum tax (AMT) patch, he

could instead wind up with the permanent abolition plan for the AMT proposed by

the Ways and Means Committee Chairman Charlie Rangel (D., N.Y.) -- a 4.6%

additional hike in the marginal rate with no deductibility of state income

taxes. Marginal tax rates would then approach 70%, levels not seen since the

1970s and among the highest in the world. The after-tax return to work -- the

take-home wage for more time or effort -- would be cut by more than 40%.

Now trade. In the primaries, Sen. Obama was famously protectionist, claiming he

would rip up and renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta).

Since its passage (for which former President Bill Clinton ran a brave anchor

leg, given opposition to trade liberalization in his party), Nafta has risen to

almost mythological proportions as a metaphor for the alleged harm done by

trade, globalization and the pace of technological change.

Yet since Nafta was passed (relative to the comparable period before passage),

U.S. manufacturing output grew more rapidly and reached an all-time high last

year; the average unemployment rate declined as employment grew 24%; real hourly

compensation in the business sector grew twice as fast as before; agricultural

exports destined for Canada and Mexico have grown substantially and trade among

the three nations has tripled; Mexican wages have risen each year since the peso

crisis of 1994; and the two binational Nafta environmental institutions have

provided nearly $1 billion for 135 environmental infrastructure projects along

the U.S.-Mexico border.

In short, it would be hard, on balance, for any objective person to argue that

Nafta has injured the U.S. economy, reduced U.S. wages, destroyed American

manufacturing, harmed our agriculture, damaged Mexican labor, failed to expand

trade, or worsened the border environment. But perhaps I am not objective, since

Nafta originated in meetings James Baker and I had early in the Bush 41

administration with Pepe Cordoba, chief of staff to Mexico's President Carlos

Salinas.

Mr. Obama has also opposed other important free-trade agreements, including

those with Colombia, South Korea and Central America. He has spoken eloquently

about America's responsibility to help alleviate global poverty -- even to the

point of saying it would help defeat terrorism -- but he has yet to endorse, let

alone forcefully advocate, the single most potent policy for doing so: a

successful completion of the Doha round of global trade liberalization. Worse

yet, he wants to put restrictions into trade treaties that would damage the

ability of poor countries to compete. And he seems to see no inconsistency in

his desire to improve America's standing in the eyes of the rest of the world

and turning his back on more than six decades of bipartisan American

presidential leadership on global trade expansion. When trade rules are not

being improved, nontariff barriers develop to offset the liberalization from the

current rules. So no trade liberalization means creeping protectionism.

History teaches us that high taxes and protectionism are not conducive to a

thriving economy, the extreme case being the higher taxes and tariffs that

deepened the Great Depression. While such a policy mix would be a real change,

as philosophers remind us, change is not always progress.

Mr. Boskin, professor of economics at Stanford University and senior fellow at

the Hoover Institution, was chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under

President George H.W. Bush.

Obamanomics Is a

Recipe for Recession, WSJ, 29.7.2008,

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB121728762442091427.html?mod=hpp_us_inside_today

Gas prices drive push to reinvent America's suburbs

29 July 2008

USA Today

By Haya El Nasser

MARICOPA, Ariz. — Mayor Tony Smith proudly waves a thank-you letter from a

major builder telling him that no city has ever reached out to him in his

30-year career the way Maricopa did.

What Maricopa has been doing is unusual, especially for a distant suburb.

This city about 35 miles south of Phoenix is asking builders not to develop just

isolated subdivisions behind walls, but whole communities that encourage walking

by including stores, schools and services nearby.

"The people of Maricopa don't want to be a bedroom community, a city of

rooftops," Smith says. "They want a self-sustained community."

Especially today. As gas prices hover around $4 a gallon, the nation's

far-flung suburbs — which have boomed because they could provide larger homes at

cheaper prices to those willing to drive farther — are losing their appeal.

Soaring energy costs and the foreclosure epidemic have jolted many Americans

into realizing that their lifestyles are at risk. For many, ever-lengthening

commutes in the search for affordable homes no longer make financial sense.

In Maricopa and elsewhere, a movement is underway to transform suburbs from

bedroom communities that sprang up during an era of cheap gasoline to lively,

more cosmopolitan places that mix houses with jobs, shops, restaurants, colleges

and entertainment.

Suburbs on the far edge of metro areas are turning aside strip malls and

creating new downtowns and neighborhoods that favor pedestrians. They're trying

to attract more employers and services such as hospitals, colleges and small

airports.

The appeal of urbanism is spreading to far suburbs such as Rancho Cucamonga,

Calif.(about 42 miles east of Los Angeles), and Huntersville, N.C., about 16

miles north of Charlotte. Centers that combine residential, retail, office and

entertainment are becoming popular far from urban centers.

Small historic towns on the edge of metropolitan areas such as Brighton, Colo.,

northeast of Denver, and Plainfield, Ill., southwest of Chicago, are emphasizing

their Main Streets and history to provide a sense of community outside the walls

of sprawling subdivisions.

Mass transit is being embraced by towns that wouldn't have been born without the

automobile. Here in Maricopa, the city introduced bus service to Phoenix and

Tempe this year, providing the first mass transit alternative to residents, many

of whom commute about 35 miles to Phoenix.

Such changes could have a profound effect on the way the nation develops as it

prepares to absorb an estimated 100 million more people by about 2040.

The scent of change is in the air in Maricopa, even in the way city officials

talk. Words such as "bedroom community" have become dirty words. "Green,"

"sustainable," "walkable," "mass transit," "conservation," "open space" and

"energy-efficient" punctuate the suburban dialogue.

"Absolutely, suburbs are not going to go away," says David Goldberg, spokesman

for Smart Growth America, a national coalition of groups pushing for

conservation and sustainable growth. "But the math is becoming very clear."

Until now, people were willing to drive increasingly far for a home they could

afford. "Drive-till-you-qualify collapsed," Goldberg says. "It's done. It's not

going to work as a housing strategy anymore."

Living costs soar

In the past year, as gas prices skyrocketed, the housing bubble burst and

transit ridership soared, the cost of living farther out for many Americans went

from manageable to pricey.

An analysis of real estate data by Fiserv Lending Solutions shows that home

prices have fallen more in towns and neighborhoods far from urban centers than

in close-in suburbs.

Developers traditionally have flocked to fields at the edge of metro areas to

avoid the stricter zoning rules and higher fees they face in older, more densely

populated communities. But that could be changing.

"The trends that pushed housing demand toward distant suburbs and rural areas

were not sustainable," says David Stiff, chief economist at Fiserv. "The problem

is that it can be two, three, four times as expensive to develop in close-in

neighborhoods vs. outlying neighborhoods, if there's any space at all."

If gas prices continue to climb or government provides incentives to build more

densely and closer in, development patterns should evolve, planners say.

"People respond to economic incentives," Stiff says. "Reducing commuting costs,

trying to be more environmentally conscious and trying to find the cheapest

housing affect decisions simultaneously."

"We're sort of stuck with retrofitting the suburbs," says Scott Bernstein, head

of the Center for Neighborhood Technology, which for years has urged that

transportation costs be a criterion for mortgage qualification. "That's not all

that bad. … There's nothing like a crisis to get people to try something."

Fresh ideas about development are spreading. A new website gives "walk" scores

for more than 2,500 neighborhoods in the 40 largest cities (walkscore.com).

Bernstein's group publishes a housing and transportation affordability index for

52 metropolitan areas (htaindex.cnt.org/).

Kenneth Himmel says now is "the perfect moment to be doing everything we're

talking about."

The developer of the Reston Town Center in Virginia, the Time Warner Center in

New York and City Place in West Palm Beach, Fla., says: "Some people will say,

'For $300,000 to $325,000, what are my options to live closer?' Maybe it's a

smaller home. … Do they want to drive or do they want to be five or 10 minutes

from their office? People will make the trade."

The new reality

The Phoenix area is legendary for sprawl. The city alone covers 517 square

miles. Surrounding it is 14,000 square miles (twice the size of New Jersey) of

desert dotted by seas of rooftops.

Foreclosures have hit the region hard — more than 5,500 the first six months of

this year. Home construction permits have slowed by more than half in many

communities. Still, building crews are grading tracts of land far from downtown.

Buckeye, more than 30 miles west of Phoenix, and Maricopa, a similar distance to

the south, are the suburbs that have the highest number of new single-family

home permits.

It's there that the seeds of change are taking root.

"We've got to get jobs to keep people from driving," says Buckeye Mayor Jackie

Meck, who worries that gas "could easily go to $8, $10" a gallon.

Meck and town manager Jeanine Guy say Buckeye's goal was never to be a bedroom

community but a gateway to California and the Pacific Rim. Already, developers

of a master-planned community on 1,100 acres 30 miles beyond Buckeye — 60 miles

from Phoenix — are rethinking their project because of fuel costs. They want to

turn it into a distribution center that would cut gas costs for truckers from

the West who are delivering goods to the Phoenix area.

In Maricopa, the city for the first time is encouraging builders to create

sustainable communities that use alternative forms of energy or are near jobs,

goods and services. Already, the city is home to Arizona's first ethanol plant

and a facility that uses recycled water to flush toilets. And there are the

commuter buses to downtown Phoenix and Tempe.

When gas prices inched toward $4 a gallon, Donna Nance bemoaned her 40-mile,

one-way commute to work her job as the court clerk in downtown Phoenix. Gas

would now cost her $60 a week, a blow for a single mom who had moved here to get

a house at a better price.

She considered moving closer, at the risk of giving up her three-bedroom,

single-family home and might have done it if Maricopa had not introduced

Phoenix-bound commuter buses in April. Nance, 43, now drives 7 miles to the bus

stop and enjoys the ride. Even if gas prices keep climbing, Nance says she has

no reason to leave.

"We hit a sweet spot starting a transit program here," Mayor Smith says.

It's a reflection of how some suburbs are trying to replace their "middle of

nowhere" image with a "there." "Maybe gas drops to $3 a gallon and people will

say we don't need to do this anymore," says Guy, the Buckeye town manager. "We

do."

Gas prices drive push to

reinvent America's suburbs, UT, 29.7.2008,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2008-07-29-nosale_N.htm

White House Predicts $482 Billion Deficit

July 29, 2008

The New York Times

By ROBERT PEAR and DAVID M. HERSZENHORN

WASHINGTON — The White House predicted Monday that President

Bush would leave a record $482 billion deficit to his successor, a sobering

turnabout in the nation’s fiscal condition from 2001, when Mr. Bush took office

after three consecutive years of budget surpluses.

The worst may be yet to come. The deficit announced by Jim Nussle, the White

House budget director, does not reflect the full cost of military operations in

Iraq and Afghanistan, the potential $50 billion cost of another economic

stimulus package, or the possibility of steeper losses in tax revenues if

individual income or corporate profits decline.

The new deficit numbers also do not account for any drains on the national

treasury that might result from further declines in the housing market.

The White House forecast was prepared before passage of the huge housing

assistance package that Mr. Bush has promised to sign. That legislation would

put taxpayer money at risk in numerous ways, especially if housing prices

continue to decline.

Mr. Nussle predicted Monday that the deficit would more than double in the

current 2008 fiscal year — to $389 billion, from $162 billion in 2007 — before

shooting up to $482 billion in the 2009 fiscal year, which begins in about two

months.

The deficit projected for 2009 would be the largest in absolute terms, easily

surpassing the record of $413 billion in 2004. The White House and many

economists prefer to measure the deficit as a share of the economy. The

projected 2009 deficit would be 3.3 percent of the economy. That is the largest

share since 2004, but well below the percentages recorded in the 1980s and early

1990s. In 1983, the deficit was 6 percent of the overall economy.

The bleak outlook for the budget will crimp the ability of the next president to

carry out ambitious spending plans. And it adds to fiscal pressures that were

already building because of the growth of Medicare and Social Security.

Senator John McCain of Arizona, the presumptive Republican presidential

nomination, said the new report showed “the dire fiscal condition of the federal

government.”

“There is no more striking reminder of the need to reverse the profligate

spending that has characterized this administration’s fiscal policy,” Mr. McCain

said.

Jason Furman, the economic policy director for the campaign of Senator Barack

Obama of Illinois, the presumptive Democratic nominee, said Mr. Obama would cut

wasteful spending, close corporate tax loopholes and roll back tax cuts for the

wealthiest Americans, “while making health care affordable and putting a

middle-class tax cut in the pocket of 95 percent of workers and their families.”

Mr. Furman said Mr. McCain was “proposing to continue the same Bush economic

policies that put our economy on this dangerous path.”

The new estimate of the 2009 deficit was $74 billion higher than Mr. Bush and

Mr. Nussle had predicted in the president’s budget just six months ago.

Mr. Nussle said the deterioration of the fiscal outlook resulted from “a

softening of the economy,” and a reduction in anticipated revenue. He attacked

Congressional Democrats, saying they had allowed spending to grow out of

control.

Representative John M. Spratt Jr., Democrat of South Carolina and chairman of

the House Budget Committee, said the new deficit figures confirmed “the dismal

legacy of the Bush administration.”

“Under its policies,” Mr. Spratt said, “the largest surpluses in history have

been converted into the largest deficits in history.”

The recently passed housing bill authorizes the Treasury Department to spend

virtually unlimited amounts to rescue the nation’s two mortgage finance giants,

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, should they be at risk of collapse. The

Congressional Budget Office estimated the new rescue authority could add a total

of $25 billion to the deficit in the next two years.

The budget office said there was a better than even chance the rescue authority

would not be used, so there would be no cost. On the other hand, it said there

was a 5 percent chance that one or both of the mortgage giants would need such

assistance to cover as-yet-unrecognized losses greater than $100 billion.

Robert L. Bixby, executive director of the Concord Coalition, a nonpartisan

budget watchdog group, said of the federal commitment: “It may not cost

anything. But if it costs a little bit, it may begin to cost a lot. You start to

deal with market psychology here. It all adds up to a pretty scary picture.”

On Monday, the Bush administration announced a new program that could reduce

some of taxpayers’ huge exposure to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and, at the same

time, reduce the dominance of the companies.

Treasury Secretary Henry M. Paulson Jr. said that four of the nation’s largest

banks had endorsed an administration effort to create a new market in a

financial instrument that could be used to finance mortgages. The instrument,

known as covered bonds, could provide a new source of cash for lending

institutions.

When Mr. Bush took office, he predicted that federal debt held by the public —

the amount borrowed by the government to pay for past deficits — would shrink to

just 8 percent of the gross domestic product in 2009. He now estimates that it

will amount to 40 percent.

Senator Kent Conrad, Democrat of North Dakota and chairman of the Senate Budget

Committee, said, “President Bush will be remembered as the most fiscally

irresponsible president in our nation’s history.”

Mr. Nussle bristled when asked about the Democrats’ suggestion that Mr. Bush had

transformed a surplus into deficit.

“There is much more to the book than the first page and the last page,” Mr.

Nussle said. “There are many, many pages and chapters in between. Democrats seem

to have not read all of them.”

Mr. Nussle asserted that Mr. Bush had inherited a recession and had to make up

for years of inadequate spending on the military, intelligence and homeland

security under President Bill Clinton.

The new White House report also includes these predictions:

¶Total federal revenues will decline slightly from 2007 to 2008.

¶In 2008 and in each of the next three years, corporate income tax collections

will be lower than the amount collected in 2007.

¶Federal spending will increase nearly 8 percent this year and then 6.5 percent

in 2009. In 2009, federal spending will be equivalent to 21.1 percent of the

economy, the largest share since 1993.

The White House now predicts that the economy will grow 1.6 percent this year,

after accounting for inflation, compared with its estimate of 2.7 percent in

February. The estimate of growth for 2009 was also lowered, to 2.2 percent, from

3 percent.

Edward P. Lazear, chairman of the president’s Council of Economic Advisers,

pointed to oil prices as a culprit. “Every time oil prices go up, it takes off

some growth from our economy,” Mr. Lazear said.

Spending on some domestic programs — like veterans’ medical care, unemployment

benefits and food and nutrition assistance — is growing faster than in the

comparable period last year.

Another factor adding to the deficit is the distribution of tax rebates to

individuals under the economic stimulus package signed into law by Mr. Bush in

February. About $79 billion has been paid out through June.

Stephen Labaton contributed reporting.

White House Predicts

$482 Billion Deficit, NYT, 29.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/29/washington/29budget.html?hp

The Downfall of a California Dreamer

July 29, 2008

The New York Times

By VIKAS BAJAJ

PASADENA, Calif. — After his mortgage company nearly crashed a

decade ago, Michael W. Perry set a new course. He bought a bank so the company,

soon rechristened IndyMac Bank, would never run short of money again.

The financial world now knows how this story ended. Just before 3 p.m. on July

11, federal regulators arrived at Mr. Perry’s headquarters here and seized

IndyMac, which was buckling under its burden of bad loans. The debacle, one of

the biggest bank failures in American history, could cost the Federal Deposit

Insurance Corporation as much as $8 billion. Shareholders have been all but

wiped out.

The collapse of IndyMac, one of the nation’s largest mortgage lenders, was the

most vivid example to date of the dangers now confronting the nation’s banks and

their investors. Two more lenders, both of them relatively small, were taken

over by the government last Friday, and many analysts believe more banks will

fail as home prices weaken and loan defaults mount.

Fears about the banking industry continue to haunt the stock market. The

Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index fell 1.9 percent on Monday, and financial

stocks tumbled 4.6 percent.

The F.D.I.C. is still trying to unravel the mess at IndyMac. The tableau of the

collapse was shocking, replete with a run on the bank, snaking lines of anxious

customers and sober assurances from Washington. Not since the 1980s has an

American bank failed so spectacularly.

How could this happen? There has been a lot of finger-pointing. The Office of

Thrift Supervision, the federal regulator that oversaw IndyMac, contends that

Senator Charles E. Schumer, Democrat of New York, caused a panic among customers

by issuing dire warnings about the bank.

Mr. Schumer maintains that the Office of Thrift Supervision was slow to spot the

problems at IndyMac, an offshoot of the Countrywide Financial Corporation, the

giant mortgage company that has come to symbolize many of the excesses of the

subprime era.

But behind the political pyrotechnics is a simple truth: Executives at IndyMac,

like many people on both Wall Street and Main Street, apparently never dreamed

that home prices might fall. To the contrary, IndyMac made many loans on terms

that implicitly assumed prices would keep rising.

Since 2000, IndyMac collected deposits from customers and used the money to make

lucrative — and, it turns out, perilous — mortgages a rung above subprime. The

bank also let people borrow money without their providing documentation to

verify their income and assets.

As long as home prices continued to go up, the company’s strategy was very

lucrative for executives, employees and shareholders. Analysts say the boom

perpetuated an insatiable hunger for mortgages and a complacency about the risks

they posed.

“The sales culture took over, and the sales division really drove the company,”

said Paul J. Miller Jr., an analyst at Friedman, Billings, Ramsey.

Mr. Perry, whom friends and co-workers described as a hands-on manager who

sometimes personally weighed in on mortgage applications, pushed the boundaries

of his trade. But apparently not even Mr. Perry, who spent much of his career at

IndyMac and its predecessor companies, saw the trouble until it was too late. He

was predicting as recently as February that the bank would not only weather the

downturn in the housing market but that it would even turn a profit this year.

Through a spokesman, Mr. Perry declined to comment for this article on the

advice of his lawyers.

Formed in 1985 as a small division of Countrywide, IndyMac started making loans

in the 1990s and became fully independent in 1997. The company nearly went under

when the credit markets seized up in 1998, but Mr. Perry steered the company

through that crisis by reducing its reliance on Wall Street financing. In July

2000, he acquired a savings bank to gain access to what was widely presumed to

be a more stable source of financing: customers’ deposits.

“He certainly never forgot that experience,” Thomas K. Brown, chief executive of

Second Curve Capital, said of IndyMac’s troubles in 1998. Mr. Brown, whose hedge

fund had owned 5 percent of IndyMac late last year, described Mr. Perry as an

“eternal optimist.”

Mr. Brown said Mr. Perry often referred to IndyMac’s previous hardships by

saying, “We have made tough decisions in the past.”

Most of this decade was a golden era for IndyMac, whose profits grew threefold

from 2001 to 2006. The company specialized in alternative-A, or alt-A,

mortgages, which are made to borrowers with good credit but are not quite as

conservative as the prime loans eligible to be bought by Fannie Mae and Freddie

Mac, the mortgage giants.

For a long time, Mr. Perry disputed the growing belief that the problems in

subprime mortgages would infect alt-A loans.

“That’s like saying that our headquarters in Pasadena is ‘in between’ Los

Angeles and Las Vegas,” he said in March 2007. “True enough, but there’s the

question of degree: Pasadena is 11 miles northeast of Los Angeles and Las Vegas

is 262 miles northeast of Pasadena.”

While alt-A loans have, in fact, defaulted at much lower rates than subprime

mortgages, they have nonetheless proved problematic. IndyMac’s biggest problem

was a $10 billion portfolio of loans that it had been unable to sell last summer

when credit markets froze up.

By the spring of this year, Mr. Perry and his board were working feverishly to

raise money, find an acquirer or sell parts of the company, an effort known

inside the bank as “Project Iron Man.” Several private equity firms, including

Cerberus Capital Management and Oaktree Capital Management, talked to the

company, but none of them made a hard offer, according to several people briefed

on or involved in the talks.

By late June, IndyMac executives realized no savior would emerge soon, and the

Office of Thrift Supervision told the bank it was no longer “well capitalized.”

Mr. Perry began laying out plans for closing IndyMac’s mortgage lending business

and dismissing half the company’s employees. The bank hoped to reduce its

portfolio of loans but continue its profitable reverse-mortgage business to buy

time until the housing market stabilized.

What came next stunned IndyMac and its regulators. Mr. Schumer wrote a letter to

the Office of Thrift Supervision and F.D.I.C. questioning the bank’s viability.

Reports of the letter created a run: In three days, customers withdrew $100

million.

Mr. Schumer later said regulators were “on top of the situation,” but confidence

in IndyMac continued to ebb. By Day 11, more than $1.3 billion had been

withdrawn from the bank, according to the Office of Thrift Supervision. Many of

the customers who withdrew their money had balances of less than $100,000, the

maximum amount insured by the F.D.I.C.

“Because there were so few bank failures in recent years, people didn’t fully

understand deposit insurance,” said John Bovenzi, the chief operating officer at

F.D.I.C. who was appointed chief executive of IndyMac Federal Bank, the

government-run successor to IndyMac.

Mr. Bovenzi sat at a conference table in Mr. Perry’s former office, a bare room

that had been stripped of the former chief executive’s personal effects save one

forlorn plant. In the hallways, business cards of F.D.I.C. officials were taped

outside offices, many of which still had names of former IndyMac officials on

them. The F.D.I.C. said it has kept all the bank’s former top executives, except

Mr. Perry.

In the aftermath of the failure the O.T.S. and Mr. Schumer traded barbs about

who was responsible. The O.T.S. director, John Reich, said Mr. Schumer’s remarks

“undermined the public confidence essential for a financial institution.” Mr.

Schumer retorted that the Office of Thrift Supervision should have moved earlier

to check “IndyMac’s poor and loose lending practices.”

Analysts said IndyMac would have gone under or been sold sooner or later, but

added that Mr. Schumer’s remarks may have sped up the process by a few months.

IndyMac executives suspected the end was near even before the regulators turned

up. Examiners do not warn banks they are coming, but they typically take over

failing institutions on Fridays so they can have a weekend to put things in

order and reopen under government control on Monday.

As the lines grew outside IndyMac branches during the week of July 7, Mr. Perry

talked with an Office of Thrift Supervision official to assess the situation.

“We’ll talk to you on Friday,” the official said, according to one bank official

briefed on the call. As word of the call spread through IndyMac, executives

began packing their personal belongings.

Stephen Labaton contributed reporting from Washington and Louise Story from New

York.

The Downfall of a

California Dreamer, NYT, 29.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/29/business/29indymac.html

Write-Down Is Planned at Merrill

July 29, 2008

The New York Times

By LOUISE STORY

Only 10 days after stunning Wall Street with a huge quarterly loss, Merrill

Lynch unexpectedly disclosed another multibillion-dollar write-down on Monday

and sought to bolster its finances once again by selling new stock to the public

and to an investment company controlled by Singapore.

Moving to purge itself of the tricky mortgage-linked investments that have

brought the once-proud firm to its knees, Merrill said that it had sold almost

all of the troublesome investments, once valued at nearly $31 billion, at a

fire-sale price of 22 cents on the dollar.

As a result, Merrill expects to record a write-down of $5.7 billion for the

third quarter. Such an outcome could push Merrill into the red for a fifth

consecutive quarter if revenue remains weak and would bring its charges since

the credit crisis erupted last summer to more than $45 billion.

The problems at Merrill, the nation’s largest brokerage, underscore how bankers

and policy makers are struggling to contain the damage to the financial system

and the broader economy caused by the collapse of housing-related debt. The

latest news came on a day when the International Monetary Fund said there was no

end in sight to the housing slump, a forecast that depressed financial shares as

well as the broader market.

To shore up its finances, Merrill said it would raise $8.5 billion in new

capital from common shareholders, including $3.4 billion from the investment arm

of the Singapore government, Temasek Holdings, which, with an 8.85 percent stake

as of June 30, is already Merrill’s largest shareholder. Those shares and a

conversion of preferred securities into common stock will dilute the value of

stock held by current shareholders by about 40 percent.

John A. Thain, who has struggled to turn Merrill around since becoming chief

executive in December, said the sale of the worrisome investments, known as

collateralized debt obligations, or C.D.O.’s, was “a significant milestone in

our risk reduction efforts.”

The C.D.O.’s have plunged in value over the last year, forcing Merrill to take

one write-down after another and sapping investors’ confidence. Merrill’s share

price fell 11.6 percent on Monday, before the news of the write-down and stock

sale were announced after the close of trading. Merrill is trading near its

lowest level in a decade.

But the sale of the C.D.O.’s, to an investment fund based in Dallas, may enable

Merrill to move on, investors said.

“What they sold, from a headline standpoint, is certainly constructive because

they have reduced risk in a very sensitive area,” said Thomas C. Priore, chief

executive of Institutional Credit Partners, a $12 billion hedge fund and C.D.O.

manager in New York.

Merrill had been working on the C.D.O. sale and the effort to raise capital

before its earnings call but did not finalize the actions until recent days.

Merrill’s sales could cause further write-downs at other Wall Street firms with

C.D.O. exposure. If those companies — the likes of Citigroup and Lehman Brothers

— have similar C.D.O.’s valued at prices higher than those at which Merrill

sold, the firms may be forced to take additional charges to reflect the

difference.

Merrill recently moved to raise money by selling its 20 percent stake in

Bloomberg L.P., the financial news and data company, for $4.425 billion. Mr.

Thain hinted at the C.D.O. sale in the quarterly earnings call, in response to a

question from Meredith Whitney, an analyst with Oppenheimer & Company.

“Why not, at this point, be the first to purge assets and get it over with? And,

if that means raising capital, raise capital,” Ms. Whitney said.

Mr. Thain responded that Merrill had been selling assets but had not yet sold

any C.D.O.’s.

“Your question is a very leading one, and that would certainly be something that

we would hope that we could do,” Mr. Thain said.

Merrill sold the investments at a steep loss. The United States super senior

asset backed-security C.D.O.’s that Merrill sold were once valued at $30.6

billion. As of the end of second-quarter, Merrill valued them at $11.1 billion —

or 36 cents on the dollar. And Merrill sold them for $6.7 billion to an

affiliate of Lone Star Funds, the Dallas private equity firm.

Merrill provided 75 percent financing to Lone Star Funds, which means Merrill

lent the private equity fund about $5 billion to complete the sale.

The discounted sales will cause the majority of Merrill’s write-down in the

third quarter.

Merrill also said it had settled a battle with the reinsurance company XL

Capital Assurance, which had insured some of the firm’s C.D.O.’s.

Write-Down Is Planned at

Merrill, NYT, 29.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/29/business/29merrill.html?hp

Fuel Subsidies Overseas Take a Toll on U.S.

July 28, 2008

The New York Times

By KEITH BRADSHER

JAKARTA, Indonesia — To understand why fuel prices in the

United States have soared over the last year, it helps to talk to the captain of

a battered wooden freighter here.

He pays just $2.30 a gallon for diesel, the same price Indonesian motorists pay

for regular gasoline. His vessel burns diesel by the barrel, so when the

government prepared for a limited price increase this spring, he took to the

streets to protest.

“If the government increases the price of fuel any more, my business will

collapse totally,” said the boat captain, Sinar, who like many Indonesians uses

only one name.

From Mexico to India to China, governments fearful of inflation and street

protests are heavily subsidizing energy prices, particularly for diesel fuel.

But the subsidies — estimated at $40 billion this year in China alone — are also

removing much of the incentive to conserve fuel.

The oil company BP, known for thorough statistical analysis of energy markets,

estimates that countries with subsidies accounted for 96 percent of the world’s

increase in oil use last year — growth that has helped drive prices to record

levels.

In most countries that do not subsidize fuel, high prices have caused oil demand

to stagnate or fall, as economic theory says they should. But in countries with

subsidies, demand is still rising steeply, threatening to outstrip the growth in

global supplies.

President Bush warned about the effects of subsidies on July 15. “I am

discouraged by the fact that some nations subsidize the purchases of product,

like gasoline, which, therefore, means that demand may not be causing the market

to adjust as rapidly as we’d like,” he said.

Indeed, the biggest question hanging over global oil markets these days may be

how much longer countries can keep paying the high cost of subsidizing their

consumers. If enough countries start passing the true cost of oil through to

their citizens, many economists believe, demand growth will slow, bringing the

oil market into better balance and lowering prices — although the long-term

economic rise of China and other populous countries makes it unlikely that

gasoline prices will plunge back to the levels of several years ago.

China raised gasoline and diesel prices on June 21, though still keeping them

below world levels. World oil prices plunged more than $4 a barrel within

minutes on the expectation that Chinese demand would slow.

In Indonesia, the government spends six times as much on energy subsidies as it

does on agricultural investments, even as rice prices have skyrocketed this

year.

Many countries, like India, have raised oil prices considerably in recent

months, only to watch world prices climb even further, pushing up the cost of

subsidies once again. China’s estimated $40 billion in subsidies this year is up

from $22 billion last year, mainly for this reason, although consumption has

also risen, with Chinese buying 18 percent more cars in the first half of this

year than in the period a year earlier.

Political pressures and inflation concerns continue to prevent many countries —

particularly in Asia, where inflation has become an acute problem — from ending

subsidies and letting domestic prices bounce up and down.

“You talk about subsidies, you’re not only talking about the economy, you’re

talking about politics,” said Purnomo Yusgiantoro, Indonesia’s minister of

energy and mineral resources. He ruled out further price increases this year

beyond one in May that raised the price of diesel and regular gasoline to $2.30

a gallon.

Nobuo Tanaka, executive director of the International Energy Agency, said that

subsidies were clearly a big factor contributing to the mismatch in supply and

demand that has helped push up world oil prices. “We think the price mechanism

is not working enough to make consumers more efficient,” he said.

Indonesia spends more on fuel subsidies, $20 billion this year, than any country

except China. Some economists estimate that fuel use in Indonesia would fall by

as much as a fifth if the government were to eliminate subsidies entirely.

Malaysia’s government incited public anger on June 4 when it raised gasoline

prices by 40 percent. The prime minister, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, announced the

following week that he would retire, although he has since said that he will not

do so until 2010.

Before adjusting the prices, Malaysia was spending 7.5 percent of its entire

economic output on fuel subsidies, a greater share than any other nation.

Indonesia follows with 4 percent.

Coming elections in Indonesia and India make further subsidy reductions less

likely in both countries. And big oil exporters like Saudi Arabia have so much

revenue right now that they can easily afford to subsidize fast-growing domestic

demand.

Chinese fuel policy is the hardest to predict: the country’s leaders are

struggling to reduce inflation and are not expected to take any action on fuel

until after the Olympics, at the earliest. But they are also campaigning for

greater energy efficiency and less reliance on fuel imports.

Many in Asia bridle at being told to reduce oil use, particularly by the United

States, a country of sport-utility vehicles and big houses.

“What about the energy consumption in the United States? Isn’t it one of the

highest in the world?” said Irvan Saefurrohman, a student activist in Jakarta

who organized a fuel-price demonstration in May that turned violent as

protesters threw rocks at police and set cars on fire.

Making matters worse, Asia’s own oil production has barely risen over the last

decade.

Indonesia, with extensive oil fields that made it a top target for Japanese

conquest during World War II, became a net oil importer in 2004. Output from its

aging fields has fallen almost 40 percent since 1995, and the country plans to

withdraw from OPEC at the end of this year.

So Asian nations increasingly compete with the West to import oil from the

Mideast and Africa.

In Asia, subsidies have been particularly prevalent for diesel, although many

countries subsidize gasoline as well. The subsidies have been an important

reason diesel prices have climbed almost twice as quickly as gasoline prices

have over the last year in the United States.

Many governments see diesel as more important because truckers and ship captains

need it to distribute goods; if diesel prices rise, consumer prices often

follow. Diesel is essentially the same fuel as heating oil, so high diesel

prices mean high prices for heating oil. Spiraling prices already have some in

the Northeast United States worried about how families will afford to heat their

homes this winter.

To be sure, subsidies are not the only cause of high crude oil prices. Strong

global economic growth, particularly in Asia, is requiring a lot of energy.

Political tensions between the United States and Iran and market psychology have

played a role.

Additional factors have contributed to strong demand for diesel in particular.

European automakers have been shifting toward the production of more cars with

diesel engines, which typically get more miles to the gallon than

gasoline-powered cars — although the cost advantage of burning diesel is

disappearing with higher prices.

When Vietnam reduced fuel subsidies on July 21, it raised domestic gasoline

prices by 31 percent, to $4.22 a gallon for 92-octane fuel. But Vietnam

increased diesel prices by only 14.3 percent, to $3.54 a gallon.

The fast-growing demand in China is skewed toward diesel as well. Automakers are

on track to sell half as many gas-powered cars in China this year as in the

United States. But in China they already sell at least 50 percent more medium-

and heavy-duty trucks, the workhorses of a manufacturing economy. Virtually all

of those run on diesel.

The cheapest fuel per gallon in many Asian countries is not diesel but kerosene,

commonly used for cooking by the very poor. In India, for example, the

government subsidizes kerosene so heavily that it sells for just 97 cents a

gallon, compared with $5 a gallon in the United States.

While the subsidies encourage greater consumption, eliminating them is not easy.

“If you reduce the subsidy for kerosene, people are likely to forage in the

forests for fuel, and environmentally that is very bad,” said Ifzal Ali, the

chief economist of the Asian Development Bank.

Kerosene is similar to jet fuel, so strong Asian demand has helped push up costs

for airlines.

Some spending on subsidies is simply wasted: Mr. Yusgiantoro, the Indonesian

official, said that fishing boats take drums of subsidized diesel out to sea for

resale to foreign fishing vessels. But a lot of subsidies are delaying what

could otherwise be a slowing of economic activity.

Mr. Sinar, the freighter captain, said that his vessel hauls cement to outlying

islands with limited cement production of their own. Higher diesel costs would

make it much costlier to move the cement, which would force builders to accept

the prices of their local cement producers and probably cause a construction

slowdown.

The nearly 30 percent increase in prices for low-octane gasoline, which

Indonesia put in place in May, has already prompted some less affluent families

to drive less. Subrata, a 34-year-old who sells gasoline in glass bottles to

local motorcyclists in Karawang, Indonesia, said that the increase had halved

his sales — and that plenty of motorists were upset.

If the price rises further, he said, “people will not buy it and it will be a

heavy blow for the lower classes.”

Fuel Subsidies

Overseas Take a Toll on U.S., NYT, 28.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/28/business/worldbusiness/28subsidy.html?hp

Worried Banks Sharply Reduce Business Loans

July 28, 2008

The New York Times

By PETER S. GOODMAN

Banks struggling to recover from multibillion-dollar losses on

real estate are curtailing loans to American businesses, depriving even healthy

companies of money for expansion and hiring.

Two vital forms of credit used by companies — commercial and industrial loans

from banks, and short-term “commercial paper” not backed by collateral —

collectively dropped almost 3 percent over the last year, to $3.27 trillion from

$3.36 trillion, according to Federal Reserve data. That is the largest annual

decline since the credit tightening that began with the last recession, in 2001.

The scarcity of credit has intensified the strains on the economy by withholding

capital from many companies, just as joblessness grows and consumers pull back

from spending in the face of high gas prices, plummeting home values and

mounting debt.

“The second half of the year is shot,” said Michael T. Darda, chief economist at

the trading firm MKM Partners in Greenwich, Conn., who was until recently

optimistic that the economy would continue expanding. “Access to capital and

credit is essential to growth. If that access is restrained or blocked, the

economic system takes a hit.”

Companies that rely on credit are now delaying and canceling expansion plans as

they struggle to secure finance.

Drew Greenblatt, president of Marlin Steel Wire Products, figured it would be

easy to get a $300,000 bank loan to finance a new robot for his factory in

Baltimore. His company, which makes parts for makers of home appliances, is

growing and profitable, he said. His expansion would add three new jobs to an

economy hungry for work.

But when Mr. Greenblatt called the local branch of Wachovia — the same bank that

had been aggressively marketing loans to him for years — he was distressed by

the response.

“The exact words were, ‘We’re saying no to almost everybody,’ ” Mr. Greenblatt

recalled. “This is why God made banks, for this kind of transaction. This is

going to slow down the American economy.”

Earlier this year, credit extended by banks to companies and consumers was still

growing at double-digit rates compared with three months earlier, according to

an analysis of Federal Reserve data by Goldman Sachs. By mid-June, bank credit

was declining at an annualized pace of more than 6 percent.

That is a drop of nearly $150 billion, an amount much larger than the value of

the tax rebates the government has sent to households this year in an effort to

spur economic activity.

Financial industry executives say tighter credit from major banks represents a

swing back to a realistic assessment of risk, after years of handing out money

with abandon. Those practices produced a mortgage crisis whose losses could

reach $1 trillion, by many estimates.

“Before, they wouldn’t verify income and they were loose on the valuations of

collateral,” said John W. Kiefer, chief executive of First Capital, a private

commercial lender. “Now they’re tightening down on the ability to repay. They go

off the reservation, and now they come back to basics. It’s preservation for

many of them at this point. It’s survival.”

But if the newfound caution of American banks is prudent in the long run, the

immediate impact is amplifying the troubles with the economy. The Federal

Reserve has been lowering interest rates aggressively to make money flow more

loosely and to spur economic activity.

The financial system is not going along: As banks hold on to their dollars,

mortgage rates are climbing. So are borrowing costs for corporations.

Some suggest that the banks, spooked by enormous losses, have replaced a

disastrously indiscriminate willingness to hand out money with an equally

arbitrary aversion to lend — even on industries that continue to grow.

“There’s been a lot of disruption in the credit market, and a lot of traditional

lenders have really tightened up,” said Gregory Goldstein, president of

Macquarie Equipment Finance, which leases computer gear and other technology to

companies. “Before, some of the standards they lent on were weak, but we think

they have overshot and gone too far on the other end.”

Such was Mr. Greenblatt’s reaction, as he learned that an infusion of credit for

his Baltimore factory would not come easily. His company has been enjoying

double-digit sales growth. This month, it received the two largest orders in its

history, he said.

“It was jubilation,” he said. “I was doing the Funky Chicken.”

The initial call to Wachovia left him dismayed.

“I’m stunned,” Mr. Greenblatt said. “God is smiling on this factory. We’re at

such an exciting inflection point, and this is what a bank is supposed to do.

There’s sand in the gears.”

No loan meant one fewer order for the factory in Chicago that makes the robot

Mr. Greenblatt wants to buy, and fewer hours for workers there. It meant less