|

History > 2011 > USA > Economy (VI)

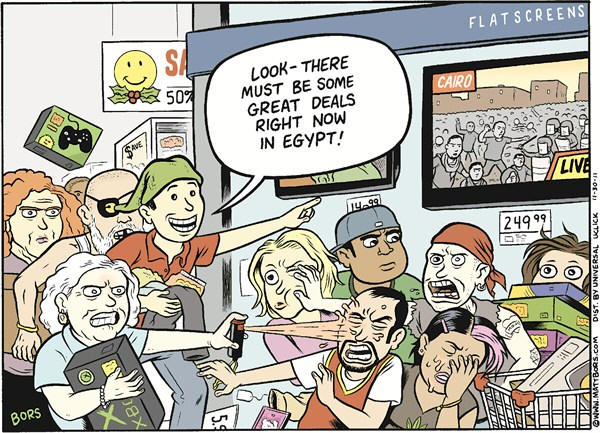

Matthew Bors

Matt Bors is a syndicated

editorial cartoonist for United Media,

as well as a graphic novelist, illustrator, witticist and blogger.

Bors scribbles from Portland, OR.

Cagle

28 November 2011

A World

in Denial of What It Knows

December

31, 2011

The New York Times

By GEOFFREY WHEATCROFT

Bath,

England

COULD there be a single phrase that explains the woes of our time, this dismal

age of political miscalculations and deceptions, of reckless and disastrous

wars, of financial boom and bust and downright criminality? Maybe there is, and

we owe it to Fintan O’Toole. That trenchant Irish commentator is a biographer

and theater critic, and a critic also of his country’s crimes and follies, as in

his gripping if horrifying book, “Ship of Fools: How Stupidity and Corruption

Sank the Celtic Tiger.”

He reminds us of the famous if gnomic saying by Donald H. Rumsfeld, then the

United States secretary of defense, that “There are known knowns... there are

known unknowns ... there are also unknown unknowns.” But the Irish problem, says

Mr. O’Toole, was none of the above. It was “unknown knowns.”

What he means is something different from denial, or evasion, irrational

exuberance or excess optimism. Unknown knowns were things that were not at all

inevitable, and were easily knowable, or indeed known, but which people chose to

“unknow.”

Unknown knowns were everywhere, from Wall Street to Brussels, from the Pentagon

to Penn State. Ireland merely happened to offer an extreme case, where “everyone

knew.” They just chose to forget that they knew — about the way that Irish banks

ran wild, how easy credit fueled a monstrous explosion of property prices and

speculative house-building. Bertie Ahern, the Irish prime minister at the time

of the rapid economic growth, merely boasted, “The boom is getting boomier,”

preferring to unknow the truth that booms always go bust.

Beginning in 2008, the skies were lighted up by financial conflagrations, from

Lehman Brothers to the Royal Bank of Scotland. These were dramatic enough — but

were they unforeseeable or unknowable? What kind of willful obtusity ever

suggested that subprime mortgages were a good idea? An intelligent child would

have known that there is no good time to lend money to people who obviously can

never repay it.

Or recall how we were taken into the Iraq war. That was the origin of Mr.

Rumsfeld’s curious words 10 years ago. When he murmured about “things we do not

know we don’t know,” he was touching on the unconventional weapons that Saddam

Hussein might — or might not — have held.

In a sense, Mr. Rumsfeld was more right than he realized. Those of us who

opposed the war may be asked to this day whether we knew what weaponry Iraq

possessed, to which the answer is that of course we didn’t. Nor, as it

transpired, did President George W. Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney, Mr.

Rumsfeld or Prime Minister Tony Blair of Britain.

But that was the wrong question. It should have been not “what weaponry does

Saddam Hussein possess?” but “Is Saddam Hussein’s weaponry, whatever it may be,

the real reason for the war, or is it a pretext confected after a decision for

war had already been taken?” The answer to that was obvious and could have been

known to all, but too many people chose to unknow it.

Then there was another unknown known: the likely consequences of an invasion.

Shortly before it began, Mr. Blair met President Jacques Chirac of France. As

well as reiterating his opposition to the coming war, Mr. Chirac offered the

prime minister specific warnings. Mr. Blair and his friends in Washington seemed

to think that they would be welcomed with open arms in Iraq, Mr. Chirac said,

but that they shouldn’t count on it. It was foolish to think of creating a

modern democracy in an artificial country with a divided society like Iraq. And

Mr. Chirac asked whether Mr. Blair realized that, by invading Iraq, they might

yet precipitate a civil war.

This has been described in a BBC documentary by someone present, Sir Stephen

Wall, a Foreign Office man then attached to Downing Street. As the British team

was leaving, Mr. Blair turned and said, “Poor old Jacques, he just doesn’t get

it,” to which Sir Stephen now adds dryly that he turned out to get it rather

better than “we” did.

At that time, Mr. Chirac was reviled in America, and his career has just ended

in disgrace, with a court conviction for embezzlement. But who was right about

Iraq? All the calamities that followed the invasion were not only foreseeable,

they were foreseen. And yet for Mr. Blair, as well as Washington, they were

unknown knowns.

One more such, bitter as it is to say so when many people have been ruined, was

the Bernard L. Madoff fraud. For years, his investors gratefully and

unquestioningly accepted returns that were strictly incredible. Loud warning

voices sounded. Harry Markopolos, a former investment officer, exhaustively

back-analyzed Mr. Madoff’s supposed figures by computer. He spent nearly nine

years repeatedly trying to explain to the Securities and Exchange Commission

that these figures were not merely incredible but mathematically impossible. And

still the S.E.C. chose to unknow it. Leos Janacek wrote a harrowing opera called

“The Makropulos Affair”; Peter Gelb at the Met should commission someone to

write “The Markopolos Affair” as a fable for our times.

In a very different kind of scandal, not everyone at Penn State, and certainly

not every fan, knew what had happened in the showers. But quite enough was known

by people who could have acted. They chose instead to unknow. And so to another

classic unknown known, the euro. The recent summit in Brussels turned into a

silly melodrama, with a British prime minister, David Cameron this time, once

more playing the pantomime villain. But Mr. Cameron was right, if for the wrong

reasons, to oppose the European Union’s latest frantic (and doomed) plan to prop

up the euro.

If truth be told (but it so rarely is!), the euro cannot work and could never

have worked. That is, a single currency embracing countries as diverse in social

culture, productivity, work practices and taxation as Germany and Greece, or the

Netherlands and Portugal, is economically impossible without much closer fiscal

and financial union — which is politically impossible. Anyone could have known

that at the time the euro was introduced, but for the rulers of the European

Union it was their very own unknown known.

“The Cloud of Unknowing” is a medieval classic of mystical writing, and

unknowing still hangs over us. It will be a happier new year if we can dispel

some of that cloud, try to unknow less, and know a little more.

Geoffrey

Wheatcroft is the author of “The Controversy of Zion,”

“The Strange

Death of Tory England” and “Yo, Blair!”

A World in Denial of What It Knows, NYT, 31.12.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/01/opinion/sunday/unknown-knowns-avoiding-the-truth.html

As

Good as It Gets?

December

31, 2011

The New York Times

The

economy was weak in 2011, but it ended better than it started, with growth up

from its lows and unemployment down from its highs. The question now is whether

that progress will continue into 2012. We wish we could say yes, but unless

policy makers are incredibly lucky or remarkably adept — certainly not the

description that comes to mind when thinking of, say, Congress — the answer is

no.

When data is released later this month, economists expect growth of around 3

percent for the last quarter of 2011, compared with 1.2 percent on average in

the first three quarters. But there is little in the latest growth spurt to

signal a self-reinforcing recovery going forward.

Holiday shoppers had more cash to spend because of the decline in oil prices,

not a rise in wages. A drop in the jobless rate was driven by a mix of new

hiring and a large number of potential workers who gave up futile job searches.

Signs of life in the housing market, including more sales, were dampened by

falling prices as foreclosures continued.

The way to revive sustainable growth is with more government aid to help create

jobs, support demand and prevent foreclosures. As things stand now, however,

Washington will provide less help, not more, in 2012. Republican lawmakers

refuse to acknowledge that government cutbacks at a time of economic weakness

will only make the economy weaker. And too many Democrats, who should know

better, have for too long been reluctant to challenge them.

The drag from premature cuts is significant. Waning stimulus spending subtracted

an estimated half a percentage point from growth in 2011; this year, cutbacks

will very likely cost the economy a full percentage point of growth. That means

the best-case economic projection is for a new year of anemic expansion and high

joblessness — muddling along with growth of about 2 percent, which is too weak

to push unemployment much below its current 8.6 percent.

And even that dismaying prospect assumes that Congress will extend the payroll

tax cut and federal unemployment benefits beyond their expiration in late

February. It also assumes that the inevitable recession in Europe and the

expected slowdown in China will be shallow and pose no real threat to the United

States recovery. If those assumptions are wrong, growth in the United States

economy, if any, will be exceedingly meager and joblessness will rise.

It does not have to be this way. After nearly a year of trying to accommodate

Republicans in their calls for excessive budget cuts, President Obama finally

pushed a strong jobs bill including spending for public works, aid to state and

local governments and an infrastructure bank, as well as renewal of a payroll

tax break and jobless aid. Congressional Republicans blocked the bill, and with

it, the chance to create some 1.9 million jobs. But late last month, the

Republican leadership in the Senate and House retreated — even if extremists in

the party did not — and managed to temporarily extend the payroll tax cut and

jobless benefits.

The extension is only for two months, setting up another fight. But the good

news is that in the showdown, Mr. Obama and the Democratic leadership did not

back down. And at least some Republicans seemed to realize that their relentless

calls for cutting may have a political cost.

The economy, and struggling Americans, need a lot more help. Mr. Obama needs to

translate his newfound focus on the middle class into an agenda for broad

prosperity, making the case that what the nation needs now is a large short-run

effort to create jobs coupled with a plan to cut the deficit as the economy

recovers.

As Good as It Gets?, NYT, 31.12.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/01/opinion/sunday/as-good-as-it-gets-for-the-economy.html

Oil Prices Predicted to Stay Above $100 a Barrel

Through Next Year

December

28, 2011

The New York Times

By DIANE CARDWELL and RICK GLADSTONE

The

United States economy managed to cope this year despite triple-digit prices for

barrels of oil. The lessons may come in handy, economists say, because those

prices will probably be sticking around.

With Iran threatening to cut off about a fifth of the world’s oil supply by

closing the Strait of Hormuz and unrest in Iraq endangering the ability to

increase production there, financial analysts say prices for two important oil

benchmarks will average from $100 a barrel to $120 a barrel in 2012.

For consumers, who have been driving less and buying more fuel-efficient cars,

weakened demand has helped lower gasoline prices 70 cents since May, to a

national average of $3.24 for a gallon of regular unleaded, according to the AAA

Fuel Gauge Report.

Now, though, the focus has turned to Iran. On Wednesday, Iran and the United

States sharpened their tone over Iran’s vow to close the Strait of Hormuz if

Western powers tried to stifle Iran’s petroleum exports.

The catalyst for the Iranian threats are new efforts by the United States and

the European Union to pressure Iran into ending its nuclear program, which Iran

has refused to do despite four rounds of sanctions imposed by the United Nations

Security Council.

Those sanctions have not focused on Iran’s oil exports. But in recent weeks, the

European Union has talked openly of imposing a boycott on Iranian oil, and

President Obama is preparing to sign legislation that, if fully enforced, could

impose harsh penalties on all buyers of Iran’s oil, with the aim of severely

impeding Iran’s ability to sell it.

Rear Adm. Habibollah Sayyari, Iran’s naval commander, said in remarks carried by

an official Iranian new site that “closing the Strait of Hormuz is very easy for

Iranian naval forces.” Admiral Sayyari, whose forces were in the midst of

ambitious war game exercises in waters near the Strait of Hormuz, was the second

top Iranian official to make such a threat in 24 hours.

A spokeswoman for the United States Navy’s Fifth Fleet, which is based in

Bahrain and patrols the strait, responded: “Anyone who threatens to disrupt

freedom of navigation in an international strait is clearly outside the

community of nations; any disruption will not be tolerated.”

The Strait of Hormuz, with two mile-wide channels for commercial shipping,

connects the Gulf of Oman to the Persian Gulf, the principal loading point for

oil shipped from Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest oil exporter.

A Saudi official told The Associated Press that the other oil-producing gulf

nations are prepared to fill any shortfall in Iranian oil supply. But just as

unrest in Libya shook the oil market in 2011, concern over Iran could influence

prices in 2012.

Markets seemed to shrug off Iran’s threats. The price of the benchmark crude oil

contract on the New York Mercantile Exchange fell for the first time in more

than week, settling at $99.36 on Wednesday, down $1.98.

But several investment banks predict that the price of the benchmark crude on

the New York exchange will average about $110 next year while Brent crude oil,

which analysts say affects what most of the world pays for oil, will average

about $115 a barrel.

“The possibility that there might be a disruption in oil supply at some time in

2012 as Iran retaliates has, I think, permanently embedded a $10 to $20 premium

in the price of oil,” said Bernard Baumohl, chief global economist at the

Economic Outlook Group. “The danger is if oil starts to move toward $130 a

barrel, or even higher, depending on whether that confrontation will escalate.

Then you’re really talking about the prospect of the U.S. tipping over into

recession in addition to Europe, and that the whole global economy will be

facing an economic downturn.”

Analysts say that members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting

Countries, including Iran and Saudi Arabia, have an incentive to keep prices

near $100 a barrel. Many governments in the Middle East and North Africa spent

heavily on social assistance programs in response to the unrest of the Arab

Spring and are depending on higher prices to help meet their budgets.

“It would be nice if prices did come down quite substantially,” said Francisco

Blanch, head of commodity strategy at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, who added

that the chances were slim. “The idea that oil is going to stay high for a while

is pretty well entrenched because this is a premium fuel in the world economy,

there isn’t a lot of oil out there and whatever oil is available is pretty much

off bounds.”

Economists say they expect prices to remain high despite the relative weaknesses

of the American and European economies because global demand for oil —

especially diesel — is escalating and outstripping supply.

“There’s a consensus view that high prices will persist through 2012 because of

the premise that the rest of the world, the emerging economies, are using a lot

more fuel,” said Tom Kloza, chief oil analyst at the Oil Price Information

Service.

At the same time, there is uncertainty in the forecasts, with some analysts

predicting that prices could end up much lower as production increases in Libya

and North America and could even drop sharply if the European economy falls

apart. The United States Energy Information Administration, for instance,

estimated this month that the price of the benchmark West Texas Intermediate,

often called W.T.I., could fall as low as $49 a barrel or rise as high as $192

by the end of next year.

Sustained triple-digit oil prices could threaten the United States recovery,

costing jobs, raising the prices of food and other consumer goods and pushing a

gallon of gasoline to $5 or more. By one estimate, a $10 increase in the price

of a barrel of oil shaves 0.2 to 0.3 percentage points off the economy’s annual

growth rate.

Early this year, when W.T.I. crude oil finally reached $100 a barrel — the

highest it had been in more than two years — the economy proved more resilient

than in 2008, when crude crossed $100 a barrel and the country was mired in

recession.

This spring, oil prices peaked at about $114 a barrel and then fell, stabilizing

well below many predictions — in part because the Arab Spring did not stop oil

from flowing out of the Middle East to the extent that had been anticipated. Gas

prices have been declining since May and gross domestic product, while still

sluggish, grew throughout the year, according to the most recent Commerce

Department estimates.

Before 2008, gas prices had mainly stayed below $3 a gallon, and Americans were

less focused on fuel economy, buying larger cars including S.U.V.’s. But after

the price shock, when oil soared to $145 a barrel and average gas prices topped

$4, many of those habits changed. Since then, gas prices have remained volatile,

rising sharply toward the end of 2010 and the early part of this year before

beginning to decline.

New figures from the Federal Highway Administration show that Americans cut back

on their driving again in October. They logged 2.3 percent less, or 254 billion

miles, compared with October a year ago, the eighth consecutive month there has

been a decline. A broader measure — the 12-month total of miles driven — shows

that motorists fell back to the low of 2.963 trillion miles driven reached at

the end of the recession in 2009.

“It’s not just, I don’t have enough money, I don’t want to go out and buy gas,”

said John Gamel, a macroeconomic analyst at MasterCard Advisors SpendingPulse.

“It’s, I have found ways not to have to buy gas and so I’m going to keep doing

that.”

He added that Americans had been doing less discretionary driving because they

still perceived gas prices as being high. “Consumers have this belief that

prices will either go up or they will remain at elevated levels.”

Seth Feaster

and Elisabeth Bumiller contributed reporting.

Oil Prices Predicted to Stay Above $100 a Barrel Through Next Year, NYT,

28.12.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/29/business/oil-prices-predicted-to-remain-above-100-a-barrel-next-year.html

Economy Contributes

to Slowest Population Growth Rate Since ’40s

December 21, 2011

The New York Times

By SABRINA TAVERNISE

WASHINGTON — The population of the United States grew this

year at its slowest rate since the 1940s, the Census Bureau reported on

Wednesday, as the gloomy economy continued to depress births and immigration

fell to its lowest level since 1991.

The first measure of the American population in the new decade offered fresh

evidence that the economic trouble that has plagued the country for the past

several years continues to make its effects felt.

The population grew by 2.8 million people from April 2010 to July 2011,

according to the bureau’s new estimates. The annual increase, about 0.7 percent

when calculated for the year that ended in July 2011, was the smallest since

1945, when the population fell by 0.3 percent in the last year of World War II.

“The nation’s overall growth rate is now at its lowest point since before the

baby boom,” the Census Bureau director, Robert M. Groves, said in a statement.

The sluggish pace puts the country “in a place we haven’t been in a very long

time,” said William H. Frey, senior demographer at the Brookings Institution.

“We don’t have that vibrancy that fuels the economy and people’s sense of

mobility,” he said. “People are a bit aimless right now.”

Underlying the modest growth was an immigration level that was the lowest in 20

years. The net increase of immigrants to the United States for the year that

ended in July was an estimated 703,000, the smallest since 1991, Mr. Frey said,

when the immigrant wave that dates to the 1970s began to pick up pace. It peaked

in 2001, when the net increase of immigrants was 1.2 million, and was still

above 1 million in 2006. But it slowed substantially when the housing market

collapsed, and the jobs associated with its boom that were popular among

immigrants disappeared.

“Net immigration from Mexico is close to zero, and we haven’t seen that in at

least 40 years,” said Jeffrey S. Passel, senior demographer at the Pew Hispanic

Center. “We are in a very different kind of immigration situation.”

Mr. Passel said that the bulk of the reduction in recent years had been among

illegal immigrants, adding that apprehensions at the border are just 20 percent

of what they were a decade ago. (The Census Bureau does not ask foreign-born

residents their status, but Mr. Passel believes the count includes most people

here illegally. )

A lagging birth rate also contributed. Births in the United States declined

precipitously during the recession and its aftermath, down by 7.3 percent from

2007 to 2010, according to Kenneth M. Johnson, the senior demographer at the

Carsey Institute at the University of New Hampshire. There were slightly over

four million births in the year that ended in July, the lowest since 1999.

Economic trauma tends to depress births. In the Great Depression, the birth rate

fell by a third, Mr. Johnson said. It is unclear whether the current dip means

that births are being delayed or that they are foregone, as they were in the

Depression, he said.

In a particularly striking measure of economic distress, birth rates among

Hispanics, who are concentrated in states hardest hit by the economic downturn,

like Florida and Arizona, declined by 17 percent from 2007 to 2010, Mr. Johnson

said. That is compared with a 3.8 percent decline for whites and a 6.7 percent

decline for blacks. Rates dropped most sharply among young Hispanics, down by 23

percent for women ages 20 to 24 between 2007 and 2010.

There were bright spots. Florida, which had watched as the decades of robust

migration into the state reversed into net declines during the economic

downturn, was starting to recover. After net losses of migrants in 2008 and

2009, the state had a net gain of 108,000 newcomers in the year ending in July,

Mr. Frey said, the highest since 2006 and a signal that the worst may be behind

it.

Neither Arizona nor Nevada, other fast-growing states during the last decade,

was so lucky. Nevada’s rate of population gain in the year ending in July was

about a quarter what it was in the middle of the decade, and Arizona’s was about

half, Mr. Johnson said.

Economy Contributes to Slowest Population

Growth Rate Since ’40s, NYT, 21.12.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/22/us/economy-contributes-to-slowest-population-growth-rate-since-1940s.html

A Fight to Make Banks More Prudent

December

20, 2011

The New York Times

By JACK EWING

FRANKFURT

— For Philipp M. Hildebrand, it was a reminder of what happens when you get

between bankers and their bonuses.

Mr. Hildebrand, the president of the Swiss central bank, was called “arrogant”

and “egotistical” by bankers quoted anonymously in the pages of Swiss

newspapers. His supposed sin: Wanting banks to hold extra capital. The fact that

Mr. Hildebrand was himself a former hedge fund manager in New York seemed only

to heighten the sense that he had betrayed his profession.

“He’ll never find another job in Switzerland,” the Swiss newspaper Der Sonntag

quoted an unnamed high-ranking banker as threatening Mr. Hildebrand in 2010.

The unusually bitter attacks on a central bank chief were a measure of what was

at stake. Mr. Hildebrand, 48, had a high-visibility role in a struggle between

bankers trying to preserve their most lucrative business practices and

regulators trying to defuse a system that, many believe, nearly blew up the

world economy.

“Many of us on the public side had to deal with industry push-back, at times

amplified by public coverage,” Mr. Hildebrand said. “One lesson that emerges is

that the capacity of the financial industry to lobby for its short-term

interests is far reaching.”

The debate centers on an international accord that most people outside the

industry have never heard of, the so-called Basel III rules. The core issue and

main point of dispute is capital — the money that banks accumulate through

issuing stock and holding onto profits, money that they do not have to repay.

The regulators want banks to finance their operations with more capital and less

borrowed money. Advocates argue that the bigger the capital buffer, the greater

the stability of the financial system. But financing operations from capital,

rather than borrowing money, is less profitable, and that means lower bonuses.

“In the financial crisis the banks got the upside and the public got the

downside,” said Stephen G. Cecchetti, head of the monetary and economic

department of the Bank for International Settlements, in Basel, Switzerland. The

bank houses the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, the secretive panel that

establishes global banking standards. “We want to make sure that doesn’t happen

again.”

After some fierce battles, proponents of the tighter rules have achieved some

success in pushing through measures that will force banks to reduce risk. The

Federal Reserve on Tuesday published draft regulations that draw heavily on the

agreements reached in Basel. But there is a long phase-in period that the

banking industry could use to try to water down the rules. And many economists

fear that the new regulatory regime still allows banks to take outsize risks.

Flaws in earlier Basel rules, known as Basel II, allowed the financial crisis to

gather in the first place, many economists say, enabling the illusion that banks

were comfortably cushioned against risk. In fact, the banks had badly

underestimated the malignant potential of their holdings. Faulty regulation also

worsened the European sovereign debt crisis, assigning government bonds

virtually zero risk. That encouraged banks to extend billions in credit to

countries like Greece and Italy, setting up a dangerous correlation between the

solvency of countries and the health of banks. The thinking, in effect, was “Why

imprison capital to insure against losses that were unlikely ever to happen?”

The technical term was “risk weighted assets.” It was as if a homeowner only had

to make a down payment on the part of a house that might catch fire. Other parts

of the property, like the swimming pool and the lawn, would not count.

The flaws in this model became obvious in the days after investment bank Lehman

Brothers collapsed in 2008. Banks that appeared to be well capitalized

discovered that they had hugely underestimated risk. Derivatives tied to the

United States real estate market, with top credit ratings, suddenly became

impossible to sell and effectively worthless.

One of the most vivid examples was right around the corner from Mr. Hildebrand’s

office in Zurich, the Swiss bank UBS. In the years before the crisis, UBS was,

on paper, one of the best capitalized banks in the world. But in the course of

2008 UBS rapidly depleted its cushion as it absorbed losses from investments in

the American real estate market.

On paper the risk-weighted assets of UBS — the total of all the money it had at

risk — were 374 billion Swiss francs (about $400 billion in today’s dollars) at

the end of 2007. But that was an adjusted figure based on the bank’s overly

optimistic estimate of the amount at risk.

Gross assets, counting everything without adjusting for perceived risk, were

much larger: 3.3 trillion Swiss francs. Measured against these total assets, UBS

capital was well below 2 percent.

In October 2008, the Swiss National Bank, where Mr. Hildebrand was then vice

president, was forced to commit $60 billion to rescue UBS.

In response, Mr. Hildebrand as well as top officials in the United States and

Britain began trying to revive an old-fashioned idea, the so-called leverage

ratio, as an extra layer of insurance in addition to tougher capital

requirements for risk-weighted assets.

The aim was to set a minimum level of capital to be held against gross assets,

regardless of estimated risk, to restrain the banks’ strong incentive to make

optimistic assumptions and supercharge leverage.

Banks considered the leverage ratio a blunt tool, an insult to all the

investments they had made in the last decade to create sophisticated risk

management systems, as well as a threat to potential profits and payouts to top

bankers.

A few months before Lehman Brothers went bankrupt, when UBS was already in

trouble and Swiss regulators proposed a leverage ratio as part of a package of

new capital rules, “the reaction was that we were completely crazy,” said Daniel

Zuberbühler, vice chairman of the board of the Swiss financial regulator, known

as Finma.

After Lehman, the mood swung sharply. “My impression was that at the highest

political level there was pretty close to a global consensus that things needed

to change,” said Stefan Ingves, governor of Sweden’s central bank, who has been

chairman of the Basel Committee since June.

But there was powerful resistance from organizations like the Washington-based

Institute of International Finance, whose membership includes most of the

world’s largest banks.

Industry groups lobbied their national representatives on the Basel Committee

furiously, to some effect. In countries like Germany and France, bankers helped

convince top officials that differences in accounting standards effectively

required European banks to hold more capital than their counterparts in the

United States, putting them at a disadvantage.

The debate peaked in mid-2010, as the European sovereign debt crisis was

emerging as a threat to the survival of the euro. In July of that year, the

heads of central banks and top regulatory officials, who oversee the work of the

Basel Committee, met to try to sign off on an agreement that would be approved

by the Group of 20 leaders.

It was, Mr. Hildebrand and other participants agree, a difficult meeting. More

than 50 representatives of 27 countries sat around a large elliptical table in a

conference room at the Bank for International Settlements in Basel. Jean-Claude

Trichet, then president of the European Central Bank, served as chairman.

According to several participants, the debate frequently became emotional, and

it looked as if the meeting could break up without reaching an agreement,

leaving the global financial system as vulnerable as before.

Mr. Trichet reminded the participants that it was up to them to prevent another

financial crisis. The Western democracies, he warned darkly, could not survive

another.

And he used a simple pressure tactic. The meeting began in the morning, with

only beverages like coffee and water for sustenance. At lunchtime, employees set

up a buffet lunch, but Mr. Trichet refused to adjourn.

The meeting dragged on until late afternoon. Finally, the exhausted and hungry

delegates agreed on a compromise. It included a leverage ratio of 3 percent of

assets, as well as several other provisions advocated by the Swiss, British and

Americans but opposed by the banks. But the leverage ratio would not be fully

enforced until 2018, to give banks plenty of time to raise more capital.

Soon after, the leaders of the G-20 nations endorsed the proposals. But that is

hardly the end of the story. The rules are simply a benchmark, and it is up to

individual nations to enshrine them in local law.

The Institute of International Finance has published studies maintaining that

the Basel rules will force banks to substantially curtail lending and undercut

economic growth. One study predicted that the Basel III rules would cost seven

million jobs. Many economists counter that such studies ignore the huge cost to

society of financial crises.

Mr. Cecchetti, of the Bank for International Settlements, called the Institute

of International Finance forecasts “completely outside historical experience.”

Will Basel III make the world a safer place?

Many economists worry that the leverage ratio, at just 3 percent, is much too

low. Banks can still borrow $32 for every dollar they hold in capital.

In Switzerland, Mr. Hildebrand pushed for local rules that would be more

rigorous than the Basel rules. It was this push that inspired so much bile from

the banks in 2010.

But circumstances were on Mr. Hildebrand’s side. As Swiss legislators were

debating the proposals earlier this year, UBS disclosed that a 31-year-old

employee had caused losses of $2.3 billion by making unauthorized trades.

Afterward, it was harder for banks to argue they had learned the lessons of the

crisis. The law passed.

A Fight to Make Banks More Prudent, NYT, 20.12.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/21/business/global/a-fight-to-make-banks-hold-more-capital.html

Fed

Proposes New Capital Rules for Banks

December

20, 2011

The New York Times

By EDWARD WYATT

WASHINGTON — The Federal Reserve on Tuesday proposed rules that would require

the largest American banks to hold more capital — and to keep it more easily

accessible — to protect against another financial crisis.

But the Fed, the nation’s chief banking regulator, added that the final capital

rules were unlikely to be more stringent than international limits that were

still under development.

That is a small victory for banks who warned that they would be severely

disadvantaged if capital requirements here were stricter than those governing

overseas banks. Bank representatives are still wary about details that remain to

be worked out, however, including how much of an extra capital cushion would be

imposed on the biggest of the big institutions like Bank of America, JPMorgan

Chase and Citigroup.

In a 173-page proposal that tied to the Dodd-Frank regulatory law passed last

year, the Fed also proposed formal limits on the amount of credit exposure that

a bank holding company can have to any major borrower, be it another bank or

corporation.

The goal is to prevent one bank from being susceptible to failure because of a

relationship with another large institution. The lack of a cash cushion in the

2008 financial crisis caused many firms to try to rapidly unwind transactions

that had troubled institutions on the other side of them, worsening a partner’s

troubles and accelerating the market’s crash.

“A lot of the proposals are built around things that the Federal Reserve and

other regulators believe did not work as well as they could leading up to the

financial crisis,” said Deborah P. Bailey, a director in Deloitte & Touche’s

banking and securities group. Over all, she added, the proposals “are designed

to make sure that banks are strong and won’t need government help going

forward.”

Of particular interest, she said, are provisions that require large banks to

have a stand-alone committee of the board that would work with a company’s chief

risk officer and be responsible for companywide risk management.

“Clearly that reflects the view that boards need to be more engaged and

involved,” Ms. Bailey said.

Under the proposals, which will be open for public comment until March 31, banks

with more than $50 billion in assets would be required, for now, to maintain a

cushion equal to 5 percent of assets even during periods of unexpected stress.

That standard is up from 4 percent previously and from much lower levels

maintained by some large banks during the growth of the housing bubble.

That 5 percent is also the same level that was outlined by the Fed last month

when it laid out plans for another round of bank stress tests. But the Fed also

warned that banks will be required to match significantly stricter international

requirements in the near future, including a larger amount of required capital

based on a bank’s overall asset size.

The international standards, known as the Basel III accords, are expected to set

capital requirements for the largest multinational financial institutions at 7

percent of capital plus a surcharge of up to 2.5 percent depending on a bank’s

overall risk levels. Those standards are not expected to be phased in until

2016, at the earliest.

The Fed’s proposed rules also incorporate triggers intended to provide early

warnings that a bank might be sliding into financial trouble. Those triggers

would activate restrictions on growth, capital distributions and dividends, as

well as limit executive compensation and asset sales.

The Federal Reserve tried in the proposals to address one of the central

problems of the financial crisis: the interconnectedness of large financial

institutions and its effect on bank stability.

For the roughly 30 banks in the United States with more than $50 billion in

assets, the new requirements would limit their credit exposure to a single

counterparty to 25 percent of the bank’s regulatory capital. The very largest

banks face stricter limits of 10 percent of capital for credit exposure between

two banks with more than $500 billion in total consolidated assets, or between

one bank of that size and a large nonbank financial company.

Currently, there are only a handful of American banks with more than $500

billion in assets including Bank of America, Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase and Wells

Fargo. The Fed and other regulators have yet to specify which nonbank financial

companies will be treated as systemically important enough to be required to

meet the stricter limits on credit exposure.

Individual banks were already subject to some limits on single-borrower lending

and investments, but those limits did not apply to bank holding companies. The

previous limits also did not account for credit exposures generated by

derivatives and other complex transactions.

A trade group representing Wall Street firms and large banks expressed cautious

optimism about the proposals, which are subject to revision based on public

comments before they are finalized sometime next year.

“We are pleased to see the Fed is taking a phased-in approach to a number of

these measures,” said Kenneth E. Bentsen Jr., an executive vice president at the

Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association. He said he hoped that the

final rules would help “to ensure the safety and soundness of our financial

system while not significantly curtailing the system’s ability to contribute to

economic growth and job creation.”

This article

has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: December 20, 2011

An earlier version of this article erroneously stated that only four American

banks

(Bank of

America, Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo)

had more

than $500 billion in assets.

Fed Proposes New Capital Rules for Banks, NYT, 20.12.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/21/business/fed-proposes-new-capital-rules-for-banks.html

The

Middle-Class Agenda

December

19, 2011

The New York Times

Earlier

this month, President Obama delivered his first unabashed 2012 campaign speech.

Unlike his opponents, Mr. Obama acknowledged the ravages of income equality, the

hollowing out of the American middle class. There is no hyperbole in the urgency

he conveyed about “a make-or-break moment for the middle class, and for all

those who are fighting to get into the middle class.”

The challenge for Mr. Obama is to translate the plight of the middle class into

an agenda for broad prosperity. Congress’s inability to cleanly extend even

emergency measures though 2012 — including the temporary payroll tax cut and

federal unemployment benefits — underscores the difficulty. The alternative is

continued decline.

Recent government data show that 100 million Americans, or about one in three,

are living in poverty or very close to it. Of 13.3 million unemployed Americans

now searching for work, 5.7 million have been looking for more than six months,

while millions more have given up altogether. Even a job is no guarantee of

middle-class security. The real median income of working-age households has

declined, from $61,600 in 2000 to $55,300 in 2010 — the result of abysmally slow

job growth even before the onset of the recession.

Economic growth alone, even if it accelerated, would not be enough to restore

the middle class. Mr. Obama refuted the Republican notion that market forces

alone can ensure broad prosperity, when the economic health of American families

also depends on government action.

It was a speech that called out for a plan. Here are the elements that matter

most:

CREATING

GOOD JOBS Despite Republican obstructionism, Mr. Obama must continue to offer

stimulus bills that include spending for public works, high-tech manufacturing

and an infrastructure bank. He must stress that obstruction costs jobs — the

bill recently filibustered by Republicans would have created an estimated 1.9

million jobs in 2012. The Republican stance also endangers future prosperity by

denying needed infrastructure upgrades and making it likely that international

competitors will outstrip America in jobs and technology.

In particular, Mr. Obama needs to debunk the notion that job creation is at odds

with environmental protection. Republicans have portrayed opposition to the

Keystone XL oil pipeline as a job killer. The truth is, oil addiction and the

failure to invest in new energy sources will be far bigger job killers. What’s

needed is a plan to create millions of clean energy jobs and to link those jobs

to workers in fossil fuel industries who otherwise would be displaced. The

climate bill that died in 2010 would have begun that transformation; the need to

try again only becomes more pressing with each passing year.

At the same time, Mr. Obama cannot ignore that most of the fast-growing

occupations in America are lower-paying service jobs, like home health care and

food service, in which it’s all but impossible to make a living. To lift wages

requires generous tax credits for low earners, a higher minimum wage, and

guaranteed health care so that wages are not consumed by medical costs. Job

training efforts must also focus on the service sector, helping to build

so-called career ladders, say, from home health aid to licensed vocational

nurse.

STOPPING

FORECLOSURES In his Kansas speech, Mr. Obama said banks “should be working to

keep responsible homeowners in their homes.” That’s too weak. The banks have

never made an all-out effort to help homeowners and unless compelled to do so,

they never will, because, in many cases, they can make more by foreclosing

rather than by modifying troubled loans.

Federal agencies can keep working with some state attorneys general and try to

settle with banks over foreclosure abuses in exchange for a commitment from them

to modify some $20 billion worth of troubled loans, or they can conduct a

thorough federal investigation into the banks’ conduct during the mortgage

bubble, looking for a far bigger settlement. The market is beset with $700

billion of negative equity; potential bank abuses are unexplored; the public is

demanding accountability. Mr. Obama should opt for a thorough federal inquiry.

In the meantime, an antiforeclosure plan that is up to the scale of the problem

would include unrelenting political pressure for principal write-downs of

underwater loans, expanded refinancings for borrowers in high-rate loans, and

forbearance for unemployed homeowners.

REGULATING THE BANKS Mr. Obama said banks are fighting the Dodd-Frank reform

“every inch of the way.”

The question is what he will do to fight back. A good start would be for him to

tell the American public whether the law is capable of performing as intended.

Is he confident that a major bank on the verge of failure could be successfully

dismantled? Is he sure that risky bank trading will be sufficiently curtailed?

If he is not confident that the law can work as intended, he must ensure better

implementation or call for a revamp of the statute itself.

He can also personally advance specific Dodd-Frank provisions. Republicans are

intent on destroying the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau; Mr. Obama

should try to recess appoint his nominee to lead the bureau, Richard Cordray,

whom Republicans recently filibustered. Mr. Obama must make clear that he

supports a strong Dodd-Frank disclosure rule on the ratio of the pay of chief

executives to that of rank-and-file employees. Such disclosure is crucial to

changing the corporate norms that have allowed for unjustifiably vast pay

discrepancies.

RAISING

TAXES, REDUCING THE DEFICIT Tax reform is essential. But there is no way to

build public consensus for broad reform without first reversing the lavish tax

breaks for the rich. In addition to letting the high-end Bush-era tax cuts

expire at the end of 2012, Mr. Obama could call for all forms of income to be

taxed at the same rates, rather than allowing lower rates for investment income,

which flows mostly to wealthy Americans. Income tax rates also need to be

adjusted at the top of the scale, so that the affluent, say, couples with

taxable income of $400,000 a year, are not paying the same top rate as

multimillionaires.

Mr. Obama should also drop his opposition to a financial transactions tax. That

stance may have made sense when the banks were reeling from the financial

crisis, but it is now at odds with a stated desire to rein in the financial

sector and raise needed revenue.

Mr. Obama has more than established his willingness to cut the deficit, agreeing

to spending cuts that, in fact, are too deep for the weak economy. Now he needs

to dominate the deficit debate, not by trying to meet Republican demands for

ever more spending cuts, but by explaining that more cuts would undermine the

recovery. In the near term, high-end tax increases are a better way to control

the deficit. They are less of a drag on economic activity than broad tax

increases or federal spending cuts.

More jobs. Fewer foreclosures. Less financial risk. Progressive taxation. Those

policies will give the middle class a fighting chance. But the list is not

exhaustive. The pillars of a healthy middle class also include public education,

Social Security, unions, child care, affirmative action and, not least, campaign

finance reform, since inequality is reinforced by the political power of the

wealthy.

The Middle-Class Agenda, NYT, 19.12.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/20/opinion/the-middle-class-agenda.html

Life

Goes On, and On ...

December

17, 2011

The New York Times

By JAMES ATLAS

A FRIEND

calls from her car: “I’m on my way to Cape Cod to scatter my mother’s ashes in

the bay, her favorite place.” Another, encountered on the street, mournfully

reports that he’s just “planted” his mother. A third e-mails news of her

mother’s death with a haunting phrase: “the sledgehammer of fatality.” It feels

strange. Why are so many of our mothers dying all at once?

As an actuarial phenomenon, the reason isn’t hard to grasp. My friends are in

their 60s now, some creeping up on 70; their mothers are in their 80s or 90s.

Ray Kurzweil, the author of “The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend

Biology,” believes that we’re close to unlocking the key to immortality. Perhaps

within this century, he prophesies, “software-based humans” will be able to

survive indefinitely on the Web, “projecting bodies whenever they need or want

them, including virtual bodies in diverse realms of virtual reality.” Neat, huh?

But for now, it’s pretty much dust to dust, the way it’s always been — mothers

included. (Most of our fathers are long gone, alas. Women live longer than men.)

It’s the ones who aren’t dead who should baffle us. My own mother, for instance,

still goes to the Boston Symphony and attends a weekly current events class at

Brookhaven, her “lifecare living” center (can’t we find a less technocratic

word?) near Boston. She writes poems in iambic pentameter for every occasion. At

94, she’s hardly anomalous: there are plenty of nonagenarians at Brookhaven.

Ninety is the new old age. As Dr. Muriel Gillick, a specialist in geriatrics and

palliative care at Harvard Medical School, says, “If you’ve made it to 85 then

you have a reasonable chance of making it to 90.” That number has nearly tripled

in the last 30 years. And if you get that far... it’s been estimated that there

will be eight million centenarians by 2050.

It won’t end there. Scientists are closing in on the mechanism of what are

called “senescent cells,” which cause the tissue deterioration responsible for

aging. Studies of mice suggest that targeting these cells can slow down the

process. “Every component of cells gets damaged with age,” Leonard Guarente, a

biology professor at M.I.T., explained to me. “It’s like an old car. You have to

repair it.” We’re not talking about immortality, Professor Guarente cautions.

Biotechnology has its limits. “We’re just extending the trend.” Extending the

trend? I can hear it now: 110 is the new 100.

Is this a good thing or a bad thing? On the debit side, there’s the ... debit.

The old-age safety net is already frayed. According to some estimates, Social

Security benefits will run out by 2037; Medicare insurance is guaranteed only

through 2024. These projected shortfalls are in part the unintended consequence

of the American health fetish. The ad executives in “Mad Men” firing up Lucky

Strikes and dosing themselves with Canadian Club didn’t have to worry. They’d be

dead long before it was time to collect.

Then there’s the question of whether reaching 5 score and 10 is worth it — the

quality-of-life question. Who wants to end up — as Jaques intones in “As You

Like It” — “sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything”? You may live to

be as old as Methuselah, who lasted 969 years, but chances are you’ll feel it.

Worse — it’s no longer a rare event — you can outlive your children. Reading the

obituary of Christopher Ma, a Washington Post executive who had been a college

classmate of mine, I was especially sad to see that Chris was survived by his

wife, a daughter, a son, a brother, two sisters and “his mother, Margaret Ma of

Menlo Park, Calif.” Can anything more tragic befall a parent than to be

predeceased by a child?

These are the perils old people suffer. What about us, the boomers, now

ourselves elderly children? One challenge my entitled generation faces is that

many of our long-lived parents are running through their retirement money, which

leaves the burden of supporting them to us. (To their credit, it’s a burden that

often bothers our parents, too.) And the cost of end-stage health care is huge —

a giant portion of all medical expenses in this country are incurred in the last

months of life. Meanwhile, our prospects of retirement recede on the horizon.

Also, elder care is stressful and time consuming. The broken hips, the trips to

the E.R., the bill paying and insurance paperwork demand patience. A paper

titled “Personality Traits of Centenarians’ Offspring” suggests this cohort

scores high marks “extraversion, openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness.”

But even the well-adjusted find looking after old parents tough.

In the mid-’80s, when the idea of the “sandwich generation” was born — boomers

saddled with the care of aging parents while raising their own children — it

seemed like a problem we would eventually outgrow. Twenty-five years later,

we’re still sandwiched, and some of those caught in the middle feel the squeeze.

So what’s the good part? Time spent with an elderly parent can offer an

opportunity for the resolution of “unfinished business,” a chance to indulge in

last-act candor. A college classmate writes in our 40th-reunion book of

ministering to her chronically ill mother and being “moved by how the twists and

turns of complicated health care have deepened our relationship.” I hear a lot

about late-in-life bonding between parent and child.

My mother needs a minor operation. “I’ve outlasted my time,” she says as she’s

wheeled into surgery. “Anyway, you’re too old to have a mother.” Thanks, Ma.

What about Rupert Murdoch? His mother is 102. Also, if I’m too old to have a

mother, why do I still feel like a child?

Two weeks later, Mom comes to Vermont to recuperate. My father, who died a

decade ago at 87, is buried in the field behind our house (hope this is legal).

His gravestone reads “Donald Herman Atlas 1913-2001,” and it has an epitaph from

his favorite poet, T. S. Eliot, carved in italics: “I grow old ... I grow old

.../ I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled.” Mom likes to visit him

there. Standing over Dad’s grave, she carries on a dialogue of one. “I thought

I’d have joined you by now, Donny, but I’m a tough old bird.” As she heads back

up to the house, she turns and waves. “À bientôt.” See you soon.

Not so fast, Mom. I still have issues.

James Atlas

is the author of “My Life in the Middle Ages: A Survivor’s Tale.”

Life Goes On, and On ..., NYT, 17.12.2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/18/opinion/sunday/old-age-life-goes-on-and-on.html

Text:

Obama’s Speech in Kansas

December

6, 2011

The New York Times

Following

is a text of President Obama’s speech in Osawatomie,

Kan. on Tuesday, as released by the White House:

THE

PRESIDENT: Thank you, everybody. Please, please have a seat. Thank you so much.

Thank you. Good afternoon, everybody.

AUDIENCE: Good afternoon.

THE PRESIDENT: Well, I want to start by thanking a few folks who’ve joined us

today. We’ve got the mayor of Osawatomie, Phil Dudley is here. (Applause.) We

have your superintendent Gary French in the house. (Applause.) And we have the

principal of Osawatomie High, Doug Chisam. (Applause.) And I have brought your

former governor, who is doing now an outstanding job as Secretary of Health and

Human Services — Kathleen Sebelius is in the house. (Applause.) We love

Kathleen.

Well, it is great to be back in the state of Tex — (laughter) — state of Kansas.

I was giving Bill Self a hard time, he was here a while back. As many of you

know, I have roots here. (Applause.) I’m sure you’re all familiar with the

Obamas of Osawatomie. (Laughter.) Actually, I like to say that I got my name

from my father, but I got my accent — and my values — from my mother.

(Applause.) She was born in Wichita. (Applause.) Her mother grew up in Augusta.

Her father was from El Dorado. So my Kansas roots run deep.

My grandparents served during World War II. He was a soldier in Patton’s Army;

she was a worker on a bomber assembly line. And together, they shared the

optimism of a nation that triumphed over the Great Depression and over fascism.

They believed in an America where hard work paid off, and responsibility was

rewarded, and anyone could make it if they tried — no matter who you were, no

matter where you came from, no matter how you started out. (Applause.)

And these values gave rise to the largest middle class and the strongest economy

that the world has ever known. It was here in America that the most productive

workers, the most innovative companies turned out the best products on Earth.

And you know what? Every American shared in that pride and in that success —

from those in the executive suites to those in middle management to those on the

factory floor. (Applause.) So you could have some confidence that if you gave it

your all, you’d take enough home to raise your family and send your kids to

school and have your health care covered, put a little away for retirement.

Today, we’re still home to the world’s most productive workers. We’re still home

to the world’s most innovative companies. But for most Americans, the basic

bargain that made this country great has eroded. Long before the recession hit,

hard work stopped paying off for too many people. Fewer and fewer of the folks

who contributed to the success of our economy actually benefited from that

success. Those at the very top grew wealthier from their incomes and their

investments — wealthier than ever before. But everybody else struggled with

costs that were growing and paychecks that weren’t — and too many families found

themselves racking up more and more debt just to keep up.

Now, for many years, credit cards and home equity loans papered over this harsh

reality. But in 2008, the house of cards collapsed. We all know the story by

now: Mortgages sold to people who couldn’t afford them, or even sometimes

understand them. Banks and investors allowed to keep packaging the risk and

selling it off. Huge bets — and huge bonuses — made with other people’s money on

the line. Regulators who were supposed to warn us about the dangers of all this,

but looked the other way or didn’t have the authority to look at all.

It was wrong. It combined the breathtaking greed of a few with irresponsibility

all across the system. And it plunged our economy and the world into a crisis

from which we’re still fighting to recover. It claimed the jobs and the homes

and the basic security of millions of people — innocent, hardworking Americans

who had met their responsibilities but were still left holding the bag.

And ever since, there’s been a raging debate over the best way to restore growth

and prosperity, restore balance, restore fairness. Throughout the country, it’s

sparked protests and political movements — from the tea party to the people

who’ve been occupying the streets of New York and other cities. It’s left

Washington in a near-constant state of gridlock. It’s been the topic of heated

and sometimes colorful discussion among the men and women running for president.

(Laughter.)

But, Osawatomie, this is not just another political debate. This is the defining

issue of our time. This is a make-or-break moment for the middle class, and for

all those who are fighting to get into the middle class. Because what’s at stake

is whether this will be a country where working people can earn enough to raise

a family, build a modest savings, own a home, secure their retirement.

Now, in the midst of this debate, there are some who seem to be suffering from a

kind of collective amnesia. After all that’s happened, after the worst economic

crisis, the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, they want to

return to the same practices that got us into this mess. In fact, they want to

go back to the same policies that stacked the deck against middle-class

Americans for way too many years. And their philosophy is simple: We are better

off when everybody is left to fend for themselves and play by their own rules.

I am here to say they are wrong. (Applause.) I’m here in Kansas to reaffirm my

deep conviction that we’re greater together than we are on our own. I believe

that this country succeeds when everyone gets a fair shot, when everyone does

their fair share, when everyone plays by the same rules. (Applause.) These

aren’t Democratic values or Republican values. These aren’t 1 percent values or

99 percent values. They’re American values. And we have to reclaim them.

(Applause.)

You see, this isn’t the first time America has faced this choice. At the turn of

the last century, when a nation of farmers was transitioning to become the

world’s industrial giant, we had to decide: Would we settle for a country where

most of the new railroads and factories were being controlled by a few giant

monopolies that kept prices high and wages low? Would we allow our citizens and

even our children to work ungodly hours in conditions that were unsafe and

unsanitary? Would we restrict education to the privileged few? Because there

were people who thought massive inequality and exploitation of people was just

the price you pay for progress.

Theodore Roosevelt disagreed. He was the Republican son of a wealthy family. He

praised what the titans of industry had done to create jobs and grow the

economy. He believed then what we know is true today, that the free market is

the greatest force for economic progress in human history. It’s led to a

prosperity and a standard of living unmatched by the rest of the world.

But Roosevelt also knew that the free market has never been a free license to

take whatever you can from whomever you can. (Applause.) He understood the free

market only works when there are rules of the road that ensure competition is

fair and open and honest. And so he busted up monopolies, forcing those

companies to compete for consumers with better services and better prices. And

today, they still must. He fought to make sure businesses couldn’t profit by

exploiting children or selling food or medicine that wasn’t safe. And today,

they still can’t.

And in 1910, Teddy Roosevelt came here to Osawatomie and he laid out his vision

for what he called a New Nationalism. “Our country,” he said, “…means nothing

unless it means the triumph of a real democracy…of an economic system under

which each man shall be guaranteed the opportunity to show the best that there

is in him.” (Applause.)

Now, for this, Roosevelt was called a radical. He was called a socialist —

(laughter) — even a communist. But today, we are a richer nation and a stronger

democracy because of what he fought for in his last campaign: an eight-hour work

day and a minimum wage for women — (applause) — insurance for the unemployed and

for the elderly, and those with disabilities; political reform and a progressive

income tax. (Applause.)

Today, over 100 years later, our economy has gone through another

transformation. Over the last few decades, huge advances in technology have

allowed businesses to do more with less, and it’s made it easier for them to set

up shop and hire workers anywhere they want in the world. And many of you know

firsthand the painful disruptions this has caused for a lot of Americans.

Factories where people thought they would retire suddenly picked up and went

overseas, where workers were cheaper. Steel mills that needed 100 — or 1,000

employees are now able to do the same work with 100 employees, so layoffs too

often became permanent, not just a temporary part of the business cycle. And

these changes didn’t just affect blue-collar workers. If you were a bank teller

or a phone operator or a travel agent, you saw many in your profession replaced

by ATMs and the Internet.

Today, even higher-skilled jobs, like accountants and middle management can be

outsourced to countries like China or India. And if you’re somebody whose job

can be done cheaper by a computer or someone in another country, you don’t have

a lot of leverage with your employer when it comes to asking for better wages or

better benefits, especially since fewer Americans today are part of a union.

Now, just as there was in Teddy Roosevelt’s time, there is a certain crowd in

Washington who, for the last few decades, have said, let’s respond to this

economic challenge with the same old tune. “The market will take care of

everything,” they tell us. If we just cut more regulations and cut more taxes —

especially for the wealthy — our economy will grow stronger. Sure, they say,

there will be winners and losers. But if the winners do really well, then jobs

and prosperity will eventually trickle down to everybody else. And, they argue,

even if prosperity doesn’t trickle down, well, that’s the price of liberty.

Now, it’s a simple theory. And we have to admit, it’s one that speaks to our

rugged individualism and our healthy skepticism of too much government. That’s

in America’s DNA. And that theory fits well on a bumper sticker. (Laughter.) But

here’s the problem: It doesn’t work. It has never worked. (Applause.) It didn’t

work when it was tried in the decade before the Great Depression. It’s not what

led to the incredible postwar booms of the ‘50s and ‘60s. And it didn’t work

when we tried it during the last decade. (Applause.) I mean, understand, it’s

not as if we haven’t tried this theory.

Remember in those years, in 2001 and 2003, Congress passed two of the most

expensive tax cuts for the wealthy in history. And what did it get us? The

slowest job growth in half a century. Massive deficits that have made it much

harder to pay for the investments that built this country and provided the basic

security that helped millions of Americans reach and stay in the middle class —

things like education and infrastructure, science and technology, Medicare and

Social Security.

Remember that in those same years, thanks to some of the same folks who are now

running Congress, we had weak regulation, we had little oversight, and what did

it get us? Insurance companies that jacked up people’s premiums with impunity

and denied care to patients who were sick, mortgage lenders that tricked

families into buying homes they couldn’t afford, a financial sector where

irresponsibility and lack of basic oversight nearly destroyed our entire

economy.

We simply cannot return to this brand of “you’re on your own” economics if we’re

serious about rebuilding the middle class in this country. (Applause.) We know

that it doesn’t result in a strong economy. It results in an economy that

invests too little in its people and in its future. We know it doesn’t result in

a prosperity that trickles down. It results in a prosperity that’s enjoyed by

fewer and fewer of our citizens.

Look at the statistics. In the last few decades, the average income of the top 1

percent has gone up by more than 250 percent to $1.2 million per year. I’m not

talking about millionaires, people who have a million dollars. I’m saying people

who make a million dollars every single year. For the top one hundredth of 1

percent, the average income is now $27 million per year. The typical CEO who

used to earn about 30 times more than his or her worker now earns 110 times

more. And yet, over the last decade the incomes of most Americans have actually

fallen by about 6 percent.

Now, this kind of inequality — a level that we haven’t seen since the Great

Depression — hurts us all. When middle-class families can no longer afford to

buy the goods and services that businesses are selling, when people are slipping

out of the middle class, it drags down the entire economy from top to bottom.

America was built on the idea of broad-based prosperity, of strong consumers all

across the country. That’s why a CEO like Henry Ford made it his mission to pay

his workers enough so that they could buy the cars he made. It’s also why a

recent study showed that countries with less inequality tend to have stronger

and steadier economic growth over the long run.

Inequality also distorts our democracy. It gives an outsized voice to the few

who can afford high-priced lobbyists and unlimited campaign contributions, and

it runs the risk of selling out our democracy to the highest bidder. (Applause.)

It leaves everyone else rightly suspicious that the system in Washington is

rigged against them, that our elected representatives aren’t looking out for the

interests of most Americans.

But there’s an even more fundamental issue at stake. This kind of gaping

inequality gives lie to the promise that’s at the very heart of America: that

this is a place where you can make it if you try. We tell people — we tell our

kids — that in this country, even if you’re born with nothing, work hard and you

can get into the middle class. We tell them that your children will have a

chance to do even better than you do. That’s why immigrants from around the

world historically have flocked to our shores.

And yet, over the last few decades, the rungs on the ladder of opportunity have

grown farther and farther apart, and the middle class has shrunk. You know, a

few years after World War II, a child who was born into poverty had a slightly

better than 50-50 chance of becoming middle class as an adult. By 1980, that

chance had fallen to around 40 percent. And if the trend of rising inequality

over the last few decades continues, it’s estimated that a child born today will

only have a one-in-three chance of making it to the middle class — 33 percent.

It’s heartbreaking enough that there are millions of working families in this

country who are now forced to take their children to food banks for a decent

meal. But the idea that those children might not have a chance to climb out of

that situation and back into the middle class, no matter how hard they work?

That’s inexcusable. It is wrong. (Applause.) It flies in the face of everything

that we stand for. (Applause.)

Now, fortunately, that’s not a future that we have to accept, because there’s

another view about how we build a strong middle class in this country — a view

that’s truer to our history, a vision that’s been embraced in the past by people

of both parties for more than 200 years.

It’s not a view that we should somehow turn back technology or put up walls

around America. It’s not a view that says we should punish profit or success or

pretend that government knows how to fix all of society’s problems. It is a view

that says in America we are greater together — when everyone engages in fair

play and everybody gets a fair shot and everybody does their fair share.

(Applause.)

So what does that mean for restoring middle-class security in today’s economy?

Well, it starts by making sure that everyone in America gets a fair shot at

success. The truth is we’ll never be able to compete with other countries when

it comes to who’s best at letting their businesses pay the lowest wages, who’s

best at busting unions, who’s best at letting companies pollute as much as they

want. That’s a race to the bottom that we can’t win, and we shouldn’t want to

win that race. (Applause.) Those countries don’t have a strong middle class.

They don’t have our standard of living.

The race we want to win, the race we can win is a race to the top — the race for

good jobs that pay well and offer middle-class security. Businesses will create

those jobs in countries with the highest-skilled, highest-educated workers, the

most advanced transportation and communication, the strongest commitment to

research and technology.

The world is shifting to an innovation economy and nobody does innovation better

than America. Nobody does it better. (Applause.) No one has better colleges.

Nobody has better universities. Nobody has a greater diversity of talent and

ingenuity. No one’s workers or entrepreneurs are more driven or more daring. The

things that have always been our strengths match up perfectly with the demands

of the moment.

But we need to meet the moment. We’ve got to up our game. We need to remember

that we can only do that together. It starts by making education a national

mission — a national mission. (Applause.) Government and businesses, parents and

citizens. In this economy, a higher education is the surest route to the middle

class. The unemployment rate for Americans with a college degree or more is

about half the national average. And their incomes are twice as high as those

who don’t have a high school diploma. Which means we shouldn’t be laying off

good teachers right now — we should be hiring them. (Applause.) We shouldn’t be

expecting less of our schools –- we should be demanding more. (Applause.) We

shouldn’t be making it harder to afford college — we should be a country where

everyone has a chance to go and doesn’t rack up $100,000 of debt just because

they went. (Applause.)

In today’s innovation economy, we also need a world-class commitment to science

and research, the next generation of high-tech manufacturing. Our factories and

our workers shouldn’t be idle. We should be giving people the chance to get new

skills and training at community colleges so they can learn how to make wind

turbines and semiconductors and high-powered batteries. And by the way, if we

don’t have an economy that’s built on bubbles and financial speculation, our

best and brightest won’t all gravitate towards careers in banking and finance.

(Applause.) Because if we want an economy that’s built to last, we need more of

those young people in science and engineering. (Applause.) This country should

not be known for bad debt and phony profits. We should be known for creating and

selling products all around the world that are stamped with three proud words:

Made in America. (Applause.)

Today, manufacturers and other companies are setting up shop in the places with

the best infrastructure to ship their products, move their workers, communicate

with the rest of the world. And that’s why the over 1 million construction

workers who lost their jobs when the housing market collapsed, they shouldn’t be

sitting at home with nothing to do. They should be rebuilding our roads and our

bridges, laying down faster railroads and broadband, modernizing our schools —

(applause) — all the things other countries are already doing to attract good

jobs and businesses to their shores.

Yes, business, and not government, will always be the primary generator of good

jobs with incomes that lift people into the middle class and keep them there.

But as a nation, we’ve always come together, through our government, to help

create the conditions where both workers and businesses can succeed. (Applause.)