|

Vocapedia >

Arts >

Photography >

Cameras > Polaroid

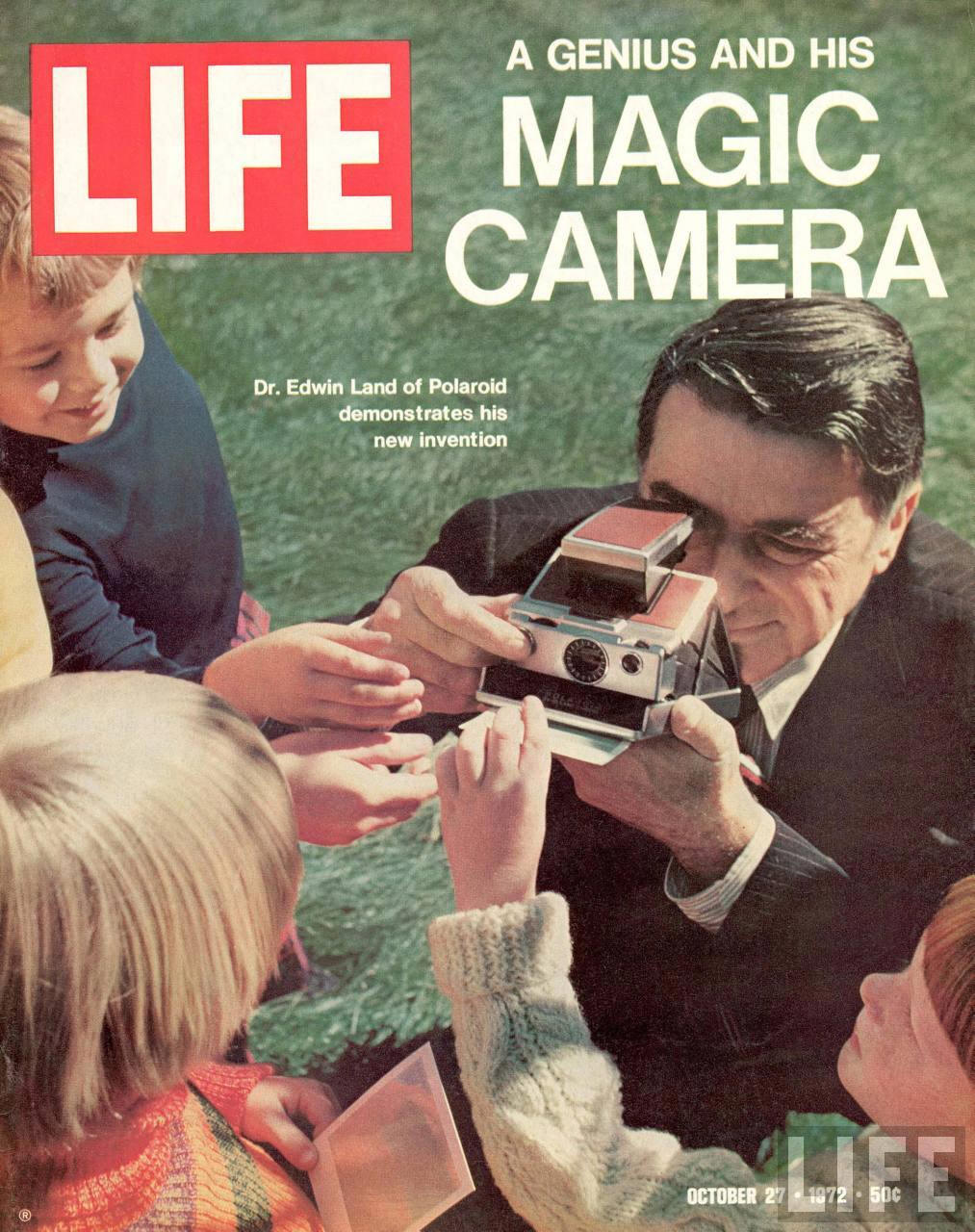

Cover of LIFE magazine dated 10-27-1972

w. logo & pic of Polaroid's Edwin Land

w.

new instant camera;

photo by Co Rentmeester.

Date taken: October 27, 1972

Photographer: Co Rentmeester

Life Images

http://images.google.com/hosted/life/a685634fe49337a6.html

No. 3242

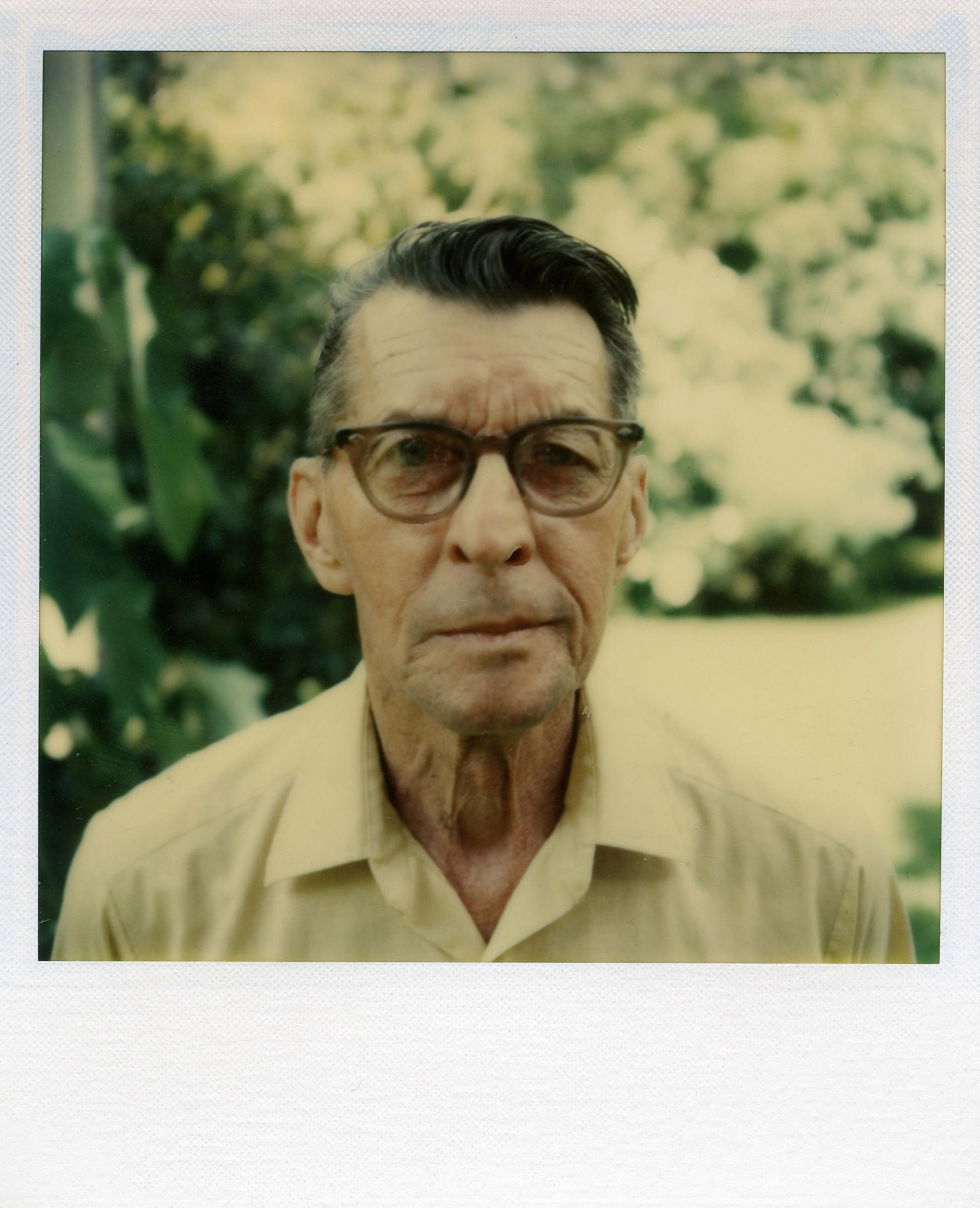

Who are the

Polaroid people?

One man's quest to

solve 6,000 mysteries

G

Monday 17 August 2015 07.00 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2015/aug/17/

found-polaroid-people-solve-6000-mysteries-in-pictures

No. 11010

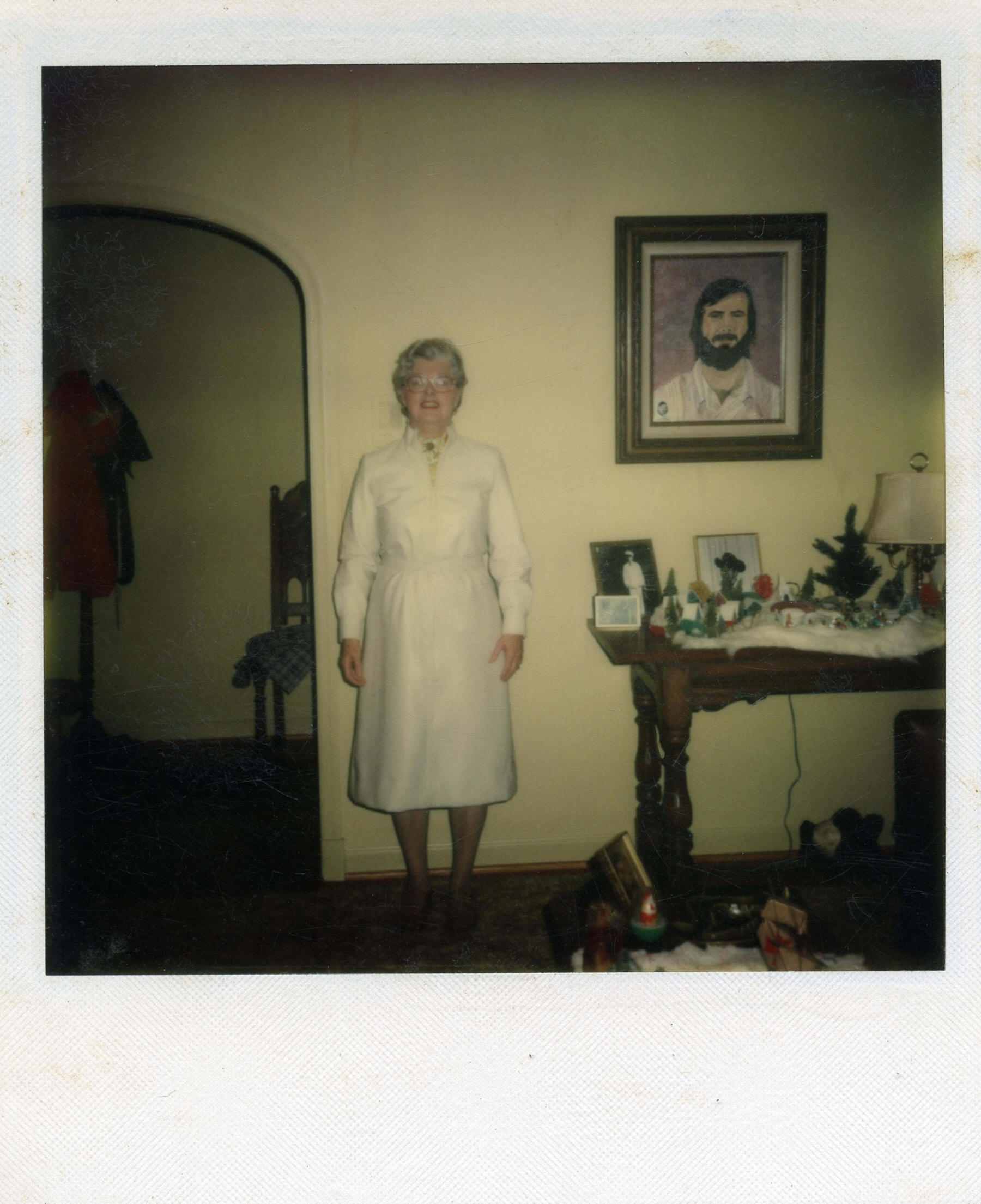

Who are the

Polaroid people?

One man's quest to

solve 6,000 mysteries

G

Monday 17 August 2015 07.00 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2015/aug/17/

found-polaroid-people-solve-6000-mysteries-in-pictures

No. 088

Who are the

Polaroid people?

One man's quest to

solve 6,000 mysteries

G

Monday 17 August 2015 07.00 BST

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2015/aug/17/

found-polaroid-people-solve-6000-mysteries-in-pictures

The demise of Polaroid’s instant film cameras

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/28/

weekinreview/28kimmelman.html

https://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2008/12/28/

weekinreview/1228_POLAROID_SS_index.html

Polaroid UK / USA

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/

polaroid

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2024/dec/13/

dietmar-busse-new-york-photography

https://www.npr.org/2023/05/11/

1174343605/virginia-hid-execution-files-from-the-public-

heres-what-they-dont-want-you-to-se

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/06/

style/clifton-mooney-polaroids.html

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/jun/22/

private-polaroids-robby-muller-cinematographer-

arles-like-sunlight-coming-through-clouds

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/sep/18/

strictly-analogue-polaroids-past-present-and-future-a-photo-essay

https://www.nytimes.com/video/

opinion/100000005503617/the-polaroid-job.html

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/in-sight/wp/2018/02/05/

this-man-collected-6000-orphaned-polaroids-

see-what-hes-doing-to-tell-their-stories/

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2016/oct/29/

polaroid-moments-the-art-of-instant-images-in-pictures

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2016/sep/14/

oliver-blohm-photographer-polaroids-sturm-und-zwang-in-pictures

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/aug/19/

anatomy-of-an-artwork-warhol-self-portrait-1981

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/aug/16/

andrei-tarkovsky-polaroid-photographs-auctioned-bonhams-solaris

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/21/

arts/design/champion-of-a-polaroid-behemoth-yields-to-the-digital-world.html

http://www.npr.org/2016/04/10/

469330626/to-access-her-big-boxy-muse-photographer-

set-her-sights-on-allen-ginsberg

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p03kd3mh - 16/03/2016 GMT

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/dec/28/

gift-polaroid-relationship-mother

http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/10/20/

rescuing-discarded-images-of-everyday-black-life/

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2015/aug/17/

found-polaroid-people-solve-6000-mysteries-in-pictures

http://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2015/jul/29/

andy-warhols-intimate-polaroids-from-divine-to-bianca-jagger

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2012/jan/18/

patti-smith-camera-solo-polaroids

http://www.thedailybeast.com/galleries/2011/08/06/

helmut-newton-polaroids-photos.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/gallery/2010/may/30/

photography-polaroid

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2010/apr/05/

polaroid-impossible-project-instant-photography

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/11/

arts/design/11polaroid.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/gallery/2009/oct/07/

polaroid-photography-warhol-walker

http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/gadgets-and-tech/features/

isex-how-pornography-has-revolutionised-technology-1749247.html

- 17 July 2009

20-inch-by-24-inch Polaroid

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/06/

arts/design/with-film-supply-dwindling-a-photographer-

known-for-huge-portraits-stares-at-retirement.html

South Africa > Polaroid's ID-2 camera

UK

(it) had a "boost" button to increase the flash

– enabling it to be used to photograph black people

for the notorious passbooks, or "dompas",

that allowed the state to control their movements.

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/jan/25/

racism-colour-photography-exhibition

Corpus of news articles

Arts > Photography > Polaroids

Critic’s Notebook

The Polaroid:

Imperfect, Yet Magical

December 28, 2008

The New York Times

By MICHAEL KIMMELMAN

The next few months will end an era that began six decades ago with a

contraption called the Model 95 camera. That accordion-style machine delivered

instant photography at a price tag equivalent to some $850 today. The SX-70,

which spit out color prints, arrived in 1972. American life during the late 20th

century had found its Boswell.

The demise of Polaroid’s instant film cameras has been coming for years. Digital

technology did it in. The decision this year by the company that Edwin Land

founded to stop manufacturing the film has left devotees who grew up with

Polaroid’s palm-size white-bordered prints bereft. They have signed up in the

thousands as members of SavePolaroid.com. Digital cameras that print instant

pictures have materialized to fill the void, providing a practical substitute.

But as in most affairs of the heart, logic is beside the point.

Cold-blooded blogs during the last year have dished about Polaroid’s leaky

developers and the impossibility of making copies from instant film prints or of

fiddling with them, which, by the way, was precisely why police photographers

long ago cottoned to them for crime scenes and mug shots. A friend the other day

also complained about how Polaroids often came out yellow and, when left on the

rainy porch or stuck onto the refrigerator door along with the shopping lists

and report cards, ended up faded and curled.

All true. One is reminded of the pragmatists’ disdain for long-playing records

when compact disks arrived. Then D.J.’s and audiophiles revived LPs, in part

precisely for the virtues of its inconvenience.

That is to say, LPs, like Polaroids, entailed certain obligating rituals. Igor

Stravinsky near the end of his life spent evenings confined to a chair. He

listened often to Beethoven. His assistant, Robert Craft, would cue the records

up, then, when one side was finished, rise from his seat, carefully flip the

vinyl disk over, place the needle at the beginning, and rejoin the composer, a

simple act of devotion required by the limits of LP technology, endlessly

repeated until it became a routine binding Stravinsky and Craft like father and

son.

I can still picture my own father with his Polaroid camera. “Cheese,” he would

actually say, and the machine would whir before expelling a print with the

negative still attached, requiring the shutterbug to wait a prescribed time

before peeling it off. My father would check his watch, shaking the covered

snapshot as if the photograph were a thermometer. Then at the right moment, with

a surgeon’s delicate hands, he would separate the negative in a single motion

and reveal — well, who knew what.

Because that was part of the beauty of the Polaroid. Mystery clung to each

impending image as it took shape, the camera conjuring up pictures of what was

right before one’s eyes, right before one’s eyes. The miracle of photography,

which Polaroids instantly exposed, never lost its primitive magic. And what

resulted, as so many sentimentalists today lament, was a memory coming into

focus on a small rectangle of film.

Or maybe not. Digital technology now excuses our mistakes all too easily — the

blurry shot of Aunt Ruth fumbling with a 3-wood at the driving range; or the one

of Cousin Jeff on graduation day where a flying Frisbee blocked the view of his

face; or of Seth in his plaid jacket heading to his first social, the image

blanched by the headlight of Burt’s car coming up the driveway; or the pictures

of you beside the Christmas tree where your hair is a mess.

Digital cameras let us do away with whatever we decide is not quite right, and

so delete the mishaps that not too often but once in a blue moon creep onto film

and that we appreciate only later as accidental masterpieces. In fact, the new

technology may be not more convenient but less than Polaroid instant film

cameras were, considering the printers and wires and other electronic gadgets

now required, but at this one thing, the act of destruction, a source of

unthinking popularity in our era of forgetfulness and extreme makeovers, digital

performs all too well. Polaroids, reflecting our imperfectability, reminded us

by contrast of our humanity.

Glossy talismans in unreal colors, as ephemeral as breath on glass, they wreaked

all the more havoc with our emotions for being so unassuming and commonplace.

One of history’s least dewy-eyed photographers, Walker Evans spent his last

years snapping some 2,500 Polaroids. During the early 1970s, to help introduce

its product, Polaroid doled out SX-70s with unlimited film to a few prominent

photographers, Evans among them.

He was having trouble wielding bigger cameras by then, and, clunky though it

could be, the SX-70 gave him a fresh lease on life. Its point-and-shoot

technology nicely dovetailed with his lean, laconic, democratic scrutiny of the

world, stripping photographs down to their bare-bone essentials. It was a

prosaic machine for an art about prosaic things in which, as in the camera

itself, Evans found a kind of grave eloquence.

A contrarian, he also embraced its off-key colors and the fact that many other

photographers didn’t take the everyman device seriously (not yet anyway). Along

with some fish-eyed close-ups of pretty young women he was trying to impress,

Evans composed abstract vignettes and snapped street signs that let him fool

around with words and puns as he had done decades earlier and generally better.

But he also shot great pictures of ready-mades, like the toothy grill of a

junked pink Ford parked in a bunch of weeds, a bittersweet elegy of bygone

America that in his hands stayed blessedly clear of nostalgia.

Other artists came to love Polaroids, of course. Warhol recognized it as the

perfect tool to capture the gaudy, passing glamour of the disco 1970s, not to

mention the genitals of visitors to the Factory, whom he apparently asked to

drop their pants for posterity’s sake. (“It was surprising who’d let me and who

wouldn’t,” he reportedly said.) Conceptual artists like Vito Acconci identified

with its quotidian efficiency and William Wegman made a nice career

photographing Weimaraners he called Man Ray and Fay Ray. David Hockney produced

Cubist collages; Chuck Close, portraits. The paradox of such a mass-market

machine serving elite purposes proved irresistible to many artists and the

Polaroid snapshot became a cliché in high art circles, whose diaristic potential

continues to lure chroniclers of fashion like Dash Snow.

Ultimately, though, it’s the populist tradition that lends the demise of

Polaroid instant film its poignancy: the power of all those ordinary pictures to

salvage forgotten lives — and the finality of the moment after which the mass of

billions of snapshots preserving millions of anonymous instants of happiness or

private consequence ceases to grow and, with us, heads toward oblivion.

In “The Emigrants,” W. G. Sebald’s narrator by chance notices an item in a

Lausanne newspaper about the discovery of a dead Alpine climber, a

long-forgotten man who happened to have been very dear to someone the narrator

once knew and had himself nearly forgotten. The climber’s remains were suddenly

released by a glacier in Switzerland, where he had gone missing 72 years

earlier.

“And so they are ever returning to us, the dead,” Sebald writes. “At times they

come back from the ice more than seven decades later and are found at the edge

of the moraine, a few polished bones and a pair of hobnailed boots.”

Or as a yellowing Polaroid snapshot we dumped into a shoebox one day long ago

and forget in a corner of the attic; or clipped to the back of the sun visor in

the old Buick; or that migrated behind the refrigerator, waiting to be

rediscovered.

The Polaroid: Imperfect,

Yet Magical,

NYT,

28.12.2008,

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/28/

weekinreview/28kimmelman.html

Novelties

Instant Digital Prints

(and Polaroid Nostalgia)

April 13, 2008

The New York Times

By ANNE EISENBERG

MILLIONS of families once snapped Polaroid photographs and enjoyed passing

around the newly minted prints on the spot, instead of waiting a week for them

to be developed.

Now, Polaroid wants to conjure up those golden analog days of vast sales and

instant gratification — this time with images captured by digital cameras and

camera phones.

This fall, the company expects to market a hand-size printer that produces color

snapshots in about 30 seconds.

Beam a photograph from a cellphone to the printer and, with a gentle purr, out

comes the full-color print — completely formed and dry to the touch.

The printer, which connects wirelessly by Bluetooth to phones and by cable to

cameras, will cost about $150. The images are 2 inches by 3 inches, the size of

a credit card. The new printers are so lightweight that a Polaroid executive

demonstrating them recently had three tucked unnoticeably into various pockets

of his trim jacket, whipping them out as if he were Harpo Marx.

The printer opens like a compact with a neat, satisfying click. Inside, no

cartridges or toner take up space. Instead, there is a computer chip, a

2-inch-long thermal printhead and a novel kind of paper embedded with

microscopic layers of dye crystals that can create a multitude of colors when

heated.

When the image file is beamed from the camera to the printer, a program

translates pixel information into heat information. Then, as the paper passes

under the printhead, the heat activates the colors within the paper and forms

crisp images.

The unusual paper is the creation of former employees of Polaroid who originated

the process there. They spun off as a separate company, Zink Imaging, in 2005

after Polaroid’s bankruptcy and eventual sale to the Petters Group Worldwide in

Minnetonka, Minn. The Alps Electric Company in Tokyo will make the printers.

The potential market for instant printing of photos captured by phones and

digital cameras is vast and largely untapped, said Steve Hoffenberg, an analyst

at Lyra Research, a market research firm in Newtonville, Mass. “There’s an

explosion in picture taking,” he said, “primarily because of the sheer number of

camera phones out there on a worldwide basis.” Lyra projects shipments of about

880 million camera phones in 2008.

But it may be hard for the new printers to find a niche. About 478 billion

photographs will be taken worldwide in 2008, Mr. Hoffenberg said, most of them

by camera phones, but only a tiny fraction of those clicks will end up as

prints.

“People can just post picture files on a Web page, or e-mail them to other

people,” he said. “These days people have many options.”

The printers might catch on for social occasions like family gatherings, he

said, or among teenagers who enjoy exchanging photos, or among professional

groups like real estate agents who want to hand an instant image to a

prospective home buyer.

The snapshots will cost less than traditional Polaroid prints, which typically

have run at least $1, and often more, during the last decade, said Jim Alviani,

director for business development for Polaroid. The Zink paper for the printer

will sell in 10-packs for $3.99, and in 30-packs for $9.99, so the cost will be

about 33 to 40 cents a sheet.

The rechargeable lithium ion battery that runs the printer will last for about

15 shots.

The prints, which are borderless, have a semigloss finish and an adhesive

backing that can be peeled off if users want to stick them on a locker or a

notebook cover, for instance.

The paper that makes the small printer possible will be used not only with

Polaroid, but also with other brands in the future, said Steve Herchen, the

chief technology officer of Zink, in Bedford, Mass.

The Tomy Company in Tokyo, for example, will embed a Zink-friendly printer

directly within a camera that it plans to distribute, he said. The Foxconn

Technology Group of Taiwan will make this integrated camera-printer.

Zink paper looks like ordinary white photographic paper, but its composition is

different.

“We begin with a plastic web,” Mr. Herchen said, “and then put down our

image-forming materials in multiple thin layers of dye crystals.”

Each 2-by-3-inch print has about 100 billion of these crystals. During printing,

about 200 million heat pulses are delivered to the paper to form the colors.

However ingenious the process, Mr. Hoffenberg of Lyra said, people might still

not be tempted to convert camera clicks into prints.

“Potential markets can exist because they aren’t tapped, but also because they

aren’t actually a market,” he said. “It’s not always evident up front which is

the case.”

Instant Digital Prints

(and Polaroid Nostalgia),

NYT,

13.4.2008,

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/13/

technology/13novel.html

Explore more on these topics

Anglonautes > Vocapedia

photography

media > photojournalism

Related > Anglonautes

>

Arts

photography

war photography

photography > galleries

|