|

Vocapedia

>

Arts >

Photography > Photography

Don McPhee 1945-2007

Orgreave, 1984

The police and NUM strikers clash

at Orgreave coking plant, near Sheffi eld,

during the miner’s strike

The Guardian

pp. 22-23

23

March 2007

Republished in The Guardian,

24 February 2009, p. 14, with

this caption:

Paul Castle (above, far left)

and George

‘Geordie’ Brealey (above, right)

at Orgreave in 1984.

http://digital.guardian.co.uk/guardian/2009/02/24/pdfs/gdn_090224_gtw_14_21993003.pdf

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2009/feb/24/miners-strike-photo-don-mcphee

Related

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/picture/2013/jun/18/

orgreave-yorkshire-miners-strike-photography

photograph

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/feb/19/

people-photograph-dont-have-voice-jim-mortram-norfolk-portraits

http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2013/dec/22/

our-addiction-to-photographing-our-lives

photograph

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/23/

arts/dan-budnik-dead.html

http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2013/dec/22/

our-addiction-to-photographing-our-lives

http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/04/23/

paris-city-of-rights/

photograph UK

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/mar/01/

deep-nostalgia-creepy-new-service-ai-animate-old-family-photos

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2017/jul/08/

how-an-old-photograph-has-helped-me-with-the-death-of-my-father

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/gallery/2016/nov/28/

lost-england-photographs-from-1870-to-1930

http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/jun/11/

what-if-you-had-no-family-photographs

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/may/26/

what-impact-do-shocking-and-dramatic-photos-have-on-you

http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/gallery/2016/may/19/

everyday-life-in-cornwall-captured-in-the-19th-century-in-pictures

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2013/may/20/

grayson-perry-artists-share-favourite-photographs

https://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2011/jun/27/

billy-the-kid-photograph-sold#zoomed-picture

photograph USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/09/

arts/flo-fox-dead.html

https://www.propublica.org/article/

family-photos-of-shoe-lane-destruction - April 23, 2024

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/08/

business/media/ai-generated-images.html

https://www.npr.org/sections/pictureshow/2021/12/25/

1060806892/indigenous-photographer-reflects-on-identity-

with-project-on-great-grandfather

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/12/

arts/19th-amendment-black-womens-suffrage-photos.html

http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2016/05/25/

mel-rosenthals-south-bronx-activism-and-engagement/

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/04/us/iwo-jima-

marines-bradley.html

http://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2016/02/17/

466453528/photos-three-very-different-views-of-japanese-internment

http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/11/05/

when-photographs-become-evidence/

http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/10/16/

staging-manipulation-ethics-photos/

http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/06/08/

magnum-chooses-the-decisive-and-transforming-photo/

https://www.npr.org/2006/08/21/

5685028/the-iwo-jima-photograph

photo USA

https://www.npr.org/2025/06/05/

nx-s1-5400606/napalm-girl-photo

family photographs / photos UK

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/mar/01/

deep-nostalgia-creepy-new-service-ai-animate-old-family-photos

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/jun/11/

what-if-you-had-no-family-photographs

family photographs

USA

https://www.propublica.org/article/

family-photos-of-shoe-lane-destruction - April 23, 2024

standalone photograph

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/aug/25/

observer-archive-the-standalone-photograph

shocking and dramatic photos

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/may/26/

what-impact-do-shocking-and-dramatic-photos-have-on-you

fake photos

USA

https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2017/02/05/

513252650/long-before-there-was-fake-news-there-were-fake-photos

be faked

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/08/

business/media/ai-generated-images.html

be manipulated

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/08/

business/media/ai-generated-images.html

doctored photos

USA

https://www.npr.org/sections/npr-history-dept/2015/10/27/

452089384/a-very-weird-photo-of-ulysses-s-grant

setting up photos

USA

https://archive.nytimes.com/lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/10/16/

staging-manipulation-ethics-photos/

digital photograph

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/sep/13/

i-lost-a-decade-of-photographs

digital photograph >

delete UK

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/sep/13/

i-lost-a-decade-of-photographs

photogenic

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2022/may/24/

birthday-paul-mccartney-harry-benson-

in-pictures

photogenic

USA

https://www.npr.org/2024/12/04/

g-s1-36764/how-to-pose-for-the-camera-with-confidence

pose

USA

https://www.npr.org/2024/12/04/

g-s1-36764/how-to-pose-for-the-camera-with-confidence

pose USA

https://www.npr.org/2024/12/04/

g-s1-36764/how-to-pose-for-the-camera-with-confidence

shot UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/series/

mybestshot

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2012/jan/18/

leo-maguire-best-shot-photography

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2008/nov/20/

best-shot-bruce-gilden

snapshot UK / USA

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/dec/27/

australian-on-mission-to-photograph-every-parish-church-in-england

https://www.npr.org/sections/npr-history-dept/2015/08/06/

429341622/the-back-story-a-photo-trend-from-the-1890s

snap

USA

https://www.npr.org/2015/10/24/

451184837/in-10-000-snaps-of-the-shutter-

a-photographic-census-of-a-city

snap

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/27/

travel/snapping-good-photos-with-your-phone.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/13/

technology/13novel.html

Upskirting is the term used to describe taking photographs,

often on a mobile-phone camera,

up an unsuspecting woman's skirt

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2009/feb/25/

women-upskirting

photo album app > Turning Phone Photos Into Albums

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/06/

technology/personaltech/organization-help-

for-turning-phone-photos-into-albums.html

cell phone photograph

picture UK

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/sep/17/

the-pictures-will-not-go-away-susan-sontag-and-photography

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/interactive/2013/may/19/

power-photography-time-mortality-memory

picture

USA

https://features.propublica.org/

garfield-park-archive/

in-those-pictures-you-can-see-the-community/ -

September 30, 2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/17/

opinion/photojournalism-children-nick-ut.html

The Guardian > That's me

in the picture UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/series/

thats-me-in-the-picture

pictures from the past

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/series/

pictures-from-the-past

phone

picture UK

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/article/2024/aug/10/

heather-mcalister-best-phone-picture

take pictures

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/gallery/2013/jul/27/

photography-london-underground-bob-mazzer

take pictures

USA

https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2016/02/17/

466453528/photos-three-very-different-views-of-japanese-internment

take photographs

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/09/

arts/flo-fox-dead.html

photograph

frame USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/09/

arts/flo-fox-dead.html

photo essay UK

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2023/jun/24/

abortion-rights-roe-v-wade-photo-essay

photography > digital / silver-gelatin process

https://www.economist.com/books-and-arts/2006/02/02/

unfrozen-in-time

photographer UK / USA

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/article/2024/may/23/

dafydd-jones-photographs-new-york-high-life-low-life

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2023/apr/27/

richard-avedon-photos-ny-exhibit

https://www.npr.org/sections/pictureshow/2022/10/29/

1125385306/a-photographer-documents-

her-personal-journey-with-breast-cancer

https://archive.nytimes.com/lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/10/16/

staging-manipulation-ethics-photos/

https://www.npr.org/sections/npr-history-dept/2015/08/06/

429341622/the-back-story-a-photo-trend-from-the-1890s

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2013/apr/14/

photography-self-publishing-afronauts-space

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2012/apr/28/

william-klein-interview-sony-photography

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2012/jan/19/

kodak-bankruptcy-digital-photography

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2012/jan/18/

leo-maguire-best-shot-photography

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/21/

arts/music/barry-feinstein-photographer-of-defining-rock-portraits-dies-at-80.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2010/feb/02/

john-bulmer-photograph-north-colour

Julia Margaret

Cameron, Photographer

October 21,

2003–January 11, 2004 at the Getty Center

https://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/cameron/

shooter

USA

http://www.npr.org/sections/npr-history-dept/2015/08/

06/429341622/the-back-story-a-photo-trend-from-the-1890s

portrait photographer

USA

http://www.npr.org/2016/04/24/

472702464/in-service-a-photographer-examines-the-flip-side-of-power

street photographer

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2014/jun/16/

garry-winogrand-street-photographer-retrospective-in-pictures

street photographer

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/26/

arts/simpson-kalisher-dead.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/20/

nyregion/for-a-street-photographer-the-weirder-the-better.html

USA > street

photography UK / USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/26/

arts/simpson-kalisher-dead.html

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2021/jun/02/

dawoud-bey-street-photography-harlem-new-york

sport photographer

UK

http://www.npr.org/2016/05/06/

476893044/a-relentless-sports-photographer-explains-how-he-got-his-shots

UrbExers

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/03/

opinion/vic-invades.html

war photography

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/13/

arts/design/war-photography-addario-capa-icp-sva.html

war photographer UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/feb/03/

don-mccullin-giles-duley-photography-retrospective-tate-interview

https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2016/jul/26/

life-and-death-as-a-war-photographer-netflix-series

http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/2011/jun/18/

war-photographers-special-report

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/feb/14/

iraq.features11

war photographer

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/18/

lens/shooting-war-photograper.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/08/

opinion/the-man-who-shot-vietnam.html

postmodern photographer USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/12/

arts/design/jan-groover-postmodern-photographer-dies-at-68.html

fashion photographer UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2020/may/13/

warhol-in-black-and-bowie-in-the-nude-portraits-by-victor-skrebneski-

in-pictures - Guardian picture gallery

https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/gallery/2017/may/17/

from-christy-turlington-to-kate-moss-through-the-lens-of-arthur-elgort-

in-pictures - Guardian picture gallery

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/sep/20/

big-picture-richard-avedon-women

fashion photographer

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/08/

arts/design/08penn.html

fashion photography

USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/26/

fashion/deborah-turbeville-fashion-photographer-dies-at-81.html

landscape photographer

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/video/2013/jul/11/

colin-prior-photography-landscape-unicorns-video

landscape

photographer USA

http://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2016/02/17/

466453528/photos-three-very-different-views-of-japanese-internment

nature

photography USA

https://www.npr.org/sections/pictureshow/2021/02/27/

970992758/housing-projects-and-empty-lots-how-chanell-stone-is-reframing-nature-photograph

wildlife photographer

UK / USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/19/

arts/peter-beard-dead.html

http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/oct/06/

wildlife-photography-pioneers-attenborough-camera

astrophotography UK

https://www.theguardian.com/science/gallery/2021/may/19/

shooting-for-the-stars-the-otherworldly-art-of-astrophotography-in-pictures

astrophotographer

USA

https://www.npr.org/2022/08/22/

1118713393/astrophotographers-moon-reddit-image

astronaut-photographers

USA

http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/06/25/

dateline-3/

studio

USA

https://www.npr.org/sections/pictureshow/2021/06/18/

1007389777/songs-for-freedom-a-juneteenth-playlist-from-pianist-lara-downes

The Photographers' Gallery

London UK

https://thephotographersgallery.org.uk/

voyeurism UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2010/sep/17/

panayiotis-lamprou-portrait-wife-photography

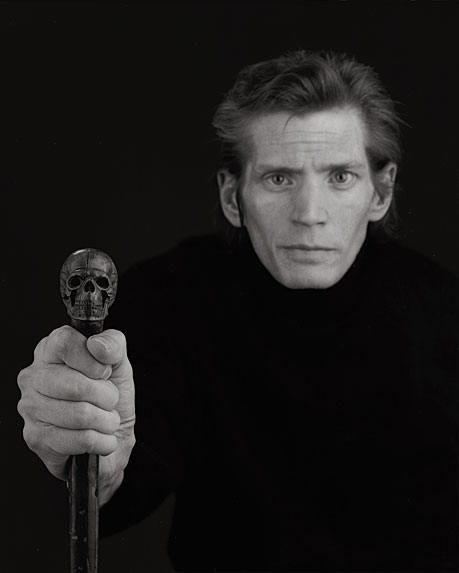

Robert

Mapplethorpe. Self-Portrait,

1988.

Gelatin-silver print,

26 5/8 x 22 1/2

inches.

Artist’s Proof 1/1.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Gift,

The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. 93.4305.

© The Estate of Robert Mapplethorpe.

http://www.guggenheimcollection.org/site/artist_work_lg_97A_3.html

photographic portraits UK

https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2010/dec/05/

10-best-photographic-portraits-mccabe

19th century > Victorian cartes de visite > family portraits

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2024/jun/01/

portrait-cards-victorian-collecting-craze-cartes-de-visite-paul-frecker-

in-pictures

USA > portrait

UK / USA

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/oct/09/

dawoud-bey-the-birmingham-project-photo-series

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/10/03/

magazine/01-brown-sisters-forty-years.html

photographic self-portraits UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/culture/2013/mar/23/

10-best-photographic-self-portraits

self-portraits USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/13/

arts/design/vivien-maier-photography-fotografiska.html

selfie

USA

https://www.npr.org/2017/12/13/

570558113/i-came-i-saw-i-selfied-how-instagram-transformed-the-way-we-experience-art

http://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2015/07/31/

427845743/what-selfies-tell-us-about-ourselves-and-how-others-see-us

http://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2015/07/27/

425681152/narcissistic-maybe-but-is-there-more-to-the-art-of-the-selfie

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/28/

fashion/a-defining-question-in-an-iphone-age-live-for-the-moment-or-record-it.html

http://www.nytimes.com/video/technology/personaltech/

100000002842065/app-smart-selfies.html

https://www.youtube.com/

watch?v=V81zxaBV56Y&list=PL4CGYNsoW2iCzzn4pZBJ58IZAAsSgng2V

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/29/

arts/the-meanings-of-the-selfie.html

nude

UK

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2014/jun/26/

history-of-nude-photography-in-pictures

landscapes UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/travel/gallery/2009/oct/19/

photography-scotland

photogram UK

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2015/nov/27/

at-first-light-the-most-iconic-camera-less-photographs-photograms-in-pictures

photography UK / USA

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/

photography

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/series/

sean-o-hagan-on-photography

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/series/

photography-then-and-now

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/06/

nyregion/mayor-adams-photo-venable-fake.html

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/feb/03/

don-mccullin-giles-duley-photography-retrospective-tate-interview

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2018/mar/01/

victorian-giants-the-birth-of-art-photography-national-portrait-gallery-london-in-pictures

https://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2017/02/22/

the-hidden-history-of-photography-and-new-york/

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2016/jun/07/

a-new-dawn-19th-century-photography-seizing-the-light

http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/12/23/

the-future-of-computational-photography/

http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/10/16/

staging-manipulation-ethics-photos/

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/26/

arts/design/with-cameras-optional-new-directions-in-photography.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/interactive/2013/may/19/

power-photography-time-mortality-memory

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/24/

sports/ozzie-sweet-who-helped-define-new-era-of-photography-dies-at-94.html

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2013/jan/10/

photography-art-of-our-time

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2012/oct/19/

photography-is-it-art

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2012/jan/19/

kodak-bankruptcy-digital-photography

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2011/apr/11/

paul-graham-interview-whitechapel-ohagan

photo

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/06/

nyregion/mayor-adams-photo-venable-fake.html

A new dawn:

19th-century photography awakens – in pictures

G 7 June 2016

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2016/jun/07/

a-new-dawn-19th-century-photography-seizing-the-light

computational

photography USA

http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/12/23/

the-future-of-computational-photography/

photographic ethics

USA

https://archive.nytimes.com/lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/06/16/

posing-questions-of-photographic-ethics/

Light And Dark:

The Racial Biases That Remain In Photography

USA

NPR April 16, 2014

https://www.npr.org/blogs/codeswitch/2014/04/16/

303721251/light-and-dark-the-racial-biases-that-remain-in-photography

The

Guardian > New Review's month in photography

UK

https://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/audioslideshow/2013/jun/28/

photography-arles-pieter-hugo-stezaker

https://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/interactive/2011/jan/06/

new-review-month-in-photography

World Photography Day UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2011/aug/19/

world-photography-day

photography enthusiast USA

http://gadgetwise.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/09/09/

canon-improves-its-mid-range-dslr/

International Center of Photography

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/topic/organization/

international-center-of-photography

documentary photography

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/05/

arts/design/ICP-documentary-photographers.html

social documentary photography

New York's Photo League

USA 1936-1951

Sixty years ago this week,

the Photo League fell victim to Cold War

witch hunts and blacklists, closing its doors

after 15 intense years of trailblazing

– and sometimes

hell-raising –

documentary photography.

From unabashedly leftist roots,

the group influenced a generation of

photographers

who transformed the documentary tradition,

elevating it to heady aesthetic

heights.

https://archive.nytimes.com/lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/11/04/

15-years-that-changed-photography/

https://www.soniahandelmanmeyer.com/

social documentary photography

Street Life in London in 1877 - in pictures UK 4 November 2013

A rare book which was one of the first examples

of social documentary photography

has been put up for auction.

Street Life in London,

written by Adolphe Smith

with photography

by the Scottish photographer John Thomson,

was published in 1877.

The aim of the book was stated

as being 'to bring before the public some account

of the present condition of the London street folk,

and to supply a series of faithful pictures

of the people themselves'

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2013/nov/04/

photography-london-street-life-in-london

USA > street photography

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2021/jun/02/

dawoud-bey-street-photography-harlem-new-york

travel photography UK

https://www.theguardian.com/travel/

photography

sports photography UK

https://www.theguardian.com/sport/gallery/2019/feb/05/

gerry-cranham-simply-the-best-in-pictures

digital photography

UK

http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/gadgets-and-tech/features/

digital-photography-has-it-become-an-obsession-1606148.html

pixel UK

http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/gadgets-and-tech/features/

digital-photography-has-it-become-an-obsession-1606148.html

photo USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/01/

world/asia/vietnam-execution-photo.html

photo storage USA

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/27/

travel/photo-storage-by-personality-yours-.html

image > Images Of The Dead

And The Change They

Provoke USA

https://www.npr.org/2013/03/21/

174958974/when-to-release-difficult-images

eye-catching images UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/2013/mar/28/

picture-desk-live-the-best-news-pictures-of-the-day

abiding image UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2009/feb/24/

miners-strike-photo-don-mcphee

iconic image UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/nov/02/

why-theres-no-such-thing-as-an-iconic-image-stuart-franklin-magnum-photos

USA > iconic image UK

/ USA

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2022/nov/22/

cars-bars-and-burger-joints-william-egglestons-iconic-america-

in-pictures - Guardian picture gallery

https://www.npr.org/sections/pictureshow/2013/01/27/

170276058/an-iconic-life-image-you-must-see

https://www.npr.org/2012/06/03/

154234617/napalm-girl-an-iconic-image-of-war-turns-40

USA > Cars, bars and burger joints:

William Eggleston’s iconic America – in pictures

UK

The landmark series Outlands

created a new visual language of gas stations,

diners and signage that inspired

a generation of photographers

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2022/nov/22/

cars-bars-and-burger-joints-william-egglestons-iconic-america-

in-pictures

- Guardian picture gallery

iconic photo USA

http://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2017/01/13/

509650251/study-what-was-the-impact-of-the-iconic-photo-of-the-syrian-boy

http://www.npr.org/2016/09/18/

494442131/life-after-iconic-photo-todays-parallels-of-american-flags-role-in-racial-protes

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/04/us/iwo-jima-

marines-bradley.html

http://www.npr.org/2009/03/24/

102112403/the-vietnam-war-through-eddie-adams-lens

https://www.npr.org/2004/05/10/

1891360/vivid-photos-remain-etched-in-memory

vivid

photos USA

https://www.npr.org/2004/05/10/

1891360/vivid-photos-remain-etched-in-memory

black and white

colour UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2010/feb/02/

john-bulmer-photograph-north-colour

photo albums UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2011/jun/14/

photo-albums-digital-collection

2010's best photography books

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2010/dec/10/

sean-o-hagan-photography-books-christmas

photography books UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2008/sep/25/

stephen.shore.photography

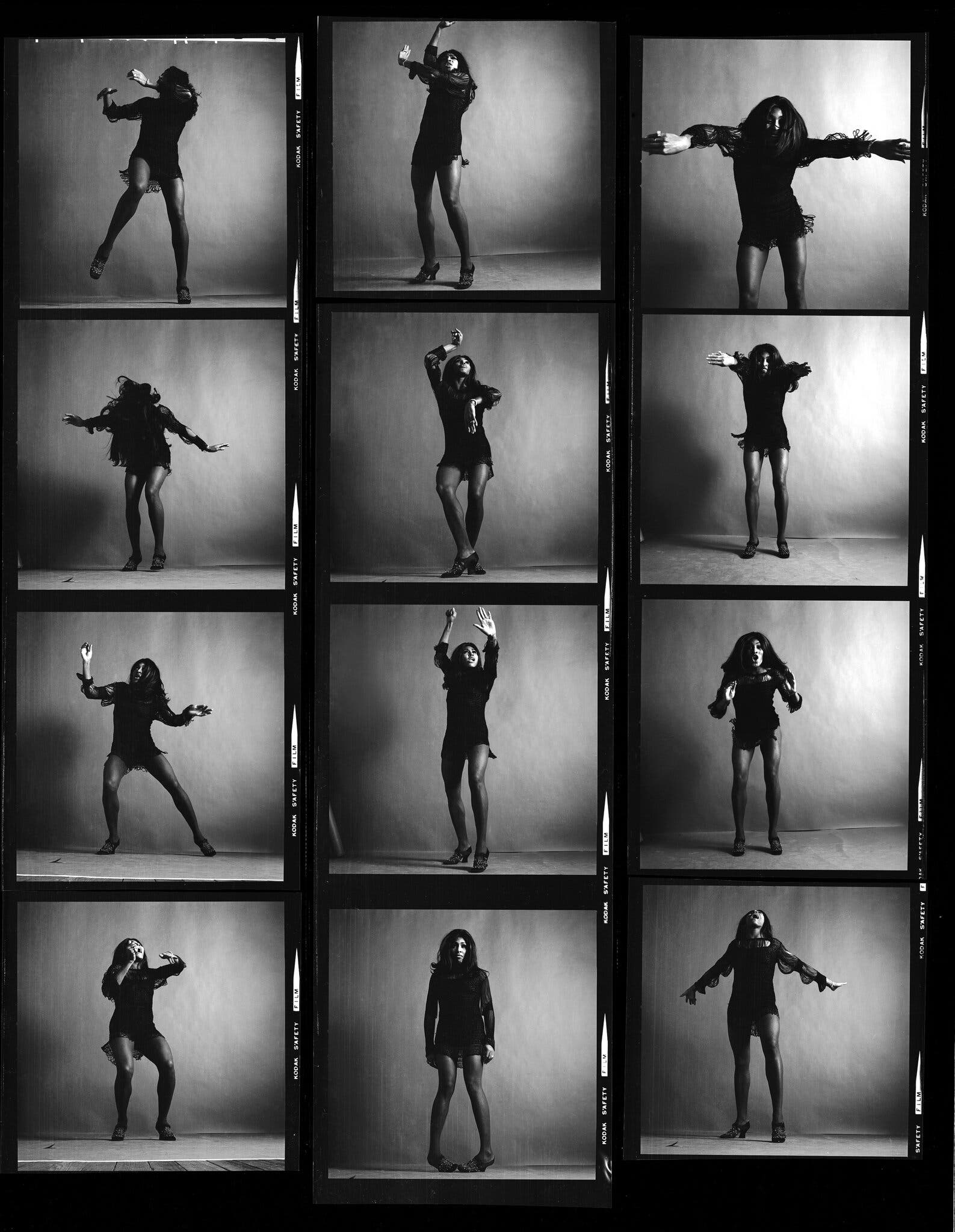

Ms. Turner’s physicality as a performer

was just as compelling to photographers

as it was to audiences.

Photograph: Jack Robinson/Hulton Archive,

via Getty Images

Anglonautes's note: this is a 6x6 contact

sheet.

Tina Turner: A Life in Photos

A performer who leveraged fringe, sequins

and sparkles

to electrifying effect onstage.

NYT

May 24, 2023

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/24/

style/tina-turner-photos.html

contact sheet USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/24/

style/tina-turner-photos.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/06/

sports/football/

fire-didnt-stop-a-game-and-50-years-later-the-proof-still-fascinates.html

https://www.vivianmaier.com/gallery/contact-sheets/

documentary photography

UK

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2003/may/17/

photography.artsfeatures

documentary photographer

USA

https://www.npr.org/sections/pictureshow/2011/04/01/

135023986/frontier-utah-

as-seen-by-mormon-bishop-documentary-photographer

documentarians USA

https://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2017/05/04/

the-power-of-photography-for-teenage-documentarians/

USA > document

UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/article/2024/may/23/

dafydd-jones-photographs-new-york-high-life-low-life

https://www.theguardian.com/culture/gallery/2016/sep/13/

jack-london-the-paths-men-take-photographs-book

Gilman Paper Company Collection of photographs

USA

https://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/17/

arts/design/17gilm.html

photo studio

exhibition UK

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/jul/05/

family-of-man-photography-edward-steichen

Flickr

online photo management and

sharing application.

Show off your favorite photos and videos to the world

https://www.flickr.com/

photo-sharing application >

Instagram UK / USA

https://www.instagram.com/

https://instagram.com/nytimes/

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/instagram

http://www.npr.org/sections/itsallpolitics/2015/09/03/

436923997/instagram-the-new-political-war-room

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/10/arts/design/

instagram-takes-on-growing-role-in-the-art-market.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/16/fashion/

your-instagram-picture-worth-a-thousand-ads.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/18/arts/design/

sharing-cultural-jewels-via-instagram.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/10/fashion/

fashion-in-the-age-of-instagram.html

http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2014/feb/06/

urban-instagram-photographers-you-should-follow

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2013/apr/29/

instagram-facebook-photo-sharing-site

http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/us-news-blog/2013/feb/05/

instagram-users-fightback-stolen-photos

https://archive.nytimes.com/dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/04/09/

facebook-buys-instagram-for-1-billion/

Picasa

a software download from Google

that helps you organize, edit,

and share your photos

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Picasa

LyveHome

https://www.mylyve.com/lyvehome

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/15/

technology/personaltech/a-cloud-free-way-to-organize-your-far-flung-photos.html

Corpus of news articles

Arts > Photography

Scratching Under the Vinyl Era

November 8, 2010

The New York Times

By TIM ARANGO

The images have been scattered about in dusty and moldy

warehouses, relics of the pre-Internet age when photography was integral to

selling music, and the photographers — names like Irving Penn, Annie Leibovitz,

Lee Friedlander and Robert Mapplethorpe — went on to become nearly as famous as

the subjects they captured and defined.

“Every day is like, what am I going to find today?” said Grayson Dantzic, the

archivist for Atlantic Records in New York. With colleagues at Warner Music

Group, Atlantic’s parent, he is part of an ambitious project to recover the

company’s story — and a good chunk of American cultural history as well — by

excavating the contents of nearly 100,000 boxes from warehouses around the

globe, whose accumulated photographs and other memorabilia track popular music

from the Edwardian and Victorian ages to disco and jazz, from Beethoven to Miles

Davis.

In an industry whose product is now compressed into tidy digital bits, the

project is an exercise in record-keeping that is partly motivated by the

urgencies of economics. The material is potentially quite valuable, and the

company is searching for ways to make money from it, through high-end art books,

sales to collectors and applications for iPads.

The project is also a story of what media companies have left behind as they

increasingly move to digital formats, a reconfiguring that has upended the

economics of the business.

“I wanted to take an inventory of what we had,” said Edgar Bronfman Jr., the

chairman and chief executive of the Warner Music Group. “We thought it was

important from an artistic standpoint, from a corporate culture standpoint and

potentially from a consumer standpoint.”

Mr. Bronfman, who calls the project “Sight of Sound,” added: “I think there’s

the potential to make money. It’s indefinable.”

The archive project may also be instructive for reintegrating visual art into

music marketing.

“Visual art has historically been a powerful component that deepens fans’ music

experience,” said Will Tanous, an executive vice president at Warner who is

overseeing the project. “We lost that in recent years. But with today’s emerging

digital platforms, we have the opportunity to inspire a renaissance in visual

art associated with music.”

After Mr. Bronfman and investors bought the company in 2004 from Time Warner, it

took a few years for executives to realize what the company had in storage under

Time Warner’s name, and they sent lawyers to the former owners to secure

permission to release the materials.

In close to a year of digging, the company has only pricked the surface: there

are still 14,000 boxes in New Jersey alone that haven’t been touched, and tens

of thousands more elsewhere in the United States and abroad in places like

Brazil, Japan and Australia.

Warner Music traces its corporate lineage back to 1811 through its ownership of

the music publisher Warner Chappell, whose business then was selling sheet music

and the machines to play it: pianos. Among the finds is a black-and-white photo

of a Chappell piano being delivered to Buckingham Palace. Songbooks dating to

the 1830s are among the oldest items. More recent materials include drawings by

Maurice Sendak, who produced cover art for Elektra Records before he became

famous as a children’s illustrator; a hand-written history of Atlantic Records

by its co-founder Ahmet Ertegun; and recording contracts for some titans of

American music.

“Aretha’s contract is right there,” said Mr. Dantzic, referring to Aretha

Franklin and pointing to a box on a shelf above his computer. In another box is

Ray Charles’s original recording contract, signed with an ‘X.’ In a separate

office is a piano from the 1920s that George Gershwin played, come upon in a

cluttered storage area.

A photocopy of a letter from Beethoven to a former pupil recommending Chappell

as a music publisher, dated 1819, has sent Warner’s archivists digging for the

valuable original.

But the bulk of the delights — of potential value to high-end collectors — are

the rock and jazz photographs, including a series of unpublished black-and-white

shots of Led Zeppelin in the studio in 1969 by Jim Cummins. The intimate

collection by Mr. Cummins, who was an Atlantic photographer, portrays a group of

young rockers before they became hugely famous and includes a rare image of

Robert Plant, the band’s singer, playing the acoustic guitar.

“There was a real sense of documentation back then,” said Bob Kaus, an Atlantic

executive who is involved in the project. “Music and art really go together.”

Among other images Mr. Dantzic displayed recently were platinum palladium prints

Penn took of Miles Davis; New Orleans jazz photos from the 1950s by Mr.

Friedlander, whose work is currently on display at the Whitney Museum of

American Art in New York; a contact sheet of Ms. Leibovitz’s images of Ms.

Franklin at the Fillmore West in 1971, as well as a collection of shots of the

same event taken by Jim Marshall, the rock photographer who died this year.

(Photography aficionados will enjoy an image Mr. Marshall took of Ms.

Leibovitz.) Materials related to some of Mapplethorpe’s early days as a

photographer for Elektra in the 1970s — he shot at least one album cover for the

band Television — are being sought in an archive on the West Coast.

Before the Internet, photography was so much a part of selling music that record

companies spared little expense to hire photographers to shoot album covers and

document a band’s work, on the road and in the studio. Today that documentation

occurs, but often by the bands themselves, with flip cameras and mobile phones.

The vinyl record, in effect, provided a large canvas for a photographer — a

surface made smaller with the advent of the compact disc, and virtually

non-existent in today’s world of digital downloads.

“I’ve had my ego stroked a lot,” said Mr. Cummins, who recalled entering record

stores and seeing his work on giant displays. “You were definitely an integral

part of what was done.”

Jac Holzman, who founded Warner’s Elektra Records 60 years ago, was a pioneer in

integrating visual art and popular music — and documenting the artistic process

at every stage, including the marketing and business aspects. When the company

placed a billboard for the Doors on the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles in the

1960s, the Doors were on hand, and Mr. Holzman made sure it was all

photographed.

“We were all adept at photography,” Mr. Holzman said. “Any employee who would be

at a session was given a camera. I never went to a session without a camera.”

These days “you don’t have the canvas to show your work,” said Neal Preston, a

photographer who worked for Atlantic in the 1970s and whose own images of Led

Zeppelin and others from that era have been uncovered in the archive project.

“There is a deep connection for a lot of us in terms of what an album cover

means to us emotionally,” he said. “It goes hand in hand with the music. At

least it used to.”

Mr. Preston spent years on the road with bands, photographing fly-on-the-wall

moments at the behest of Atlantic Records.

“These jobs aren’t given out anymore,” he said. “Bands and labels don’t want to

spend the money.”

Lisa Tanner was hired as a photographer by Atlantic in the late 1970s when she

was just 17, and hit the road with bands like the Rolling Stones, Foreigner and

Yes.

“You just sort of hung out,” she said, “and waited for a moment to happen.” .

Scratching Under the

Vinyl Era,

NYT,

8.11.2010,

https://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/09/

arts/music/09archive.html

News Photos, on the Move,

Make News

February 2, 2010

The New York Times

By RANDY KENNEDY

In the middle of December two trailer trucks left New York

City bound for Austin, Tex., packed with a precious and unusual cargo: the

entire collection of pictures amassed over more than half a century by the

Magnum photo cooperative, whose members have been among the world’s most

distinguished photojournalists.

It is one of the most important photography archives of the 20th century,

consisting of more than 180,000 images known as press prints, the kind of prints

once made by the collective to circulate to magazines and newspapers. They are

marked on their reverse sides with decades of historical impasto — stamps,

stickers and writing chronicling their publication histories — that speaks to

their role in helping to create the collective photo bank of modern culture.

“The trucks had GPS, and I was so nervous, I was tracking every single second of

the trip,” Mark Lubell, Magnum’s director, said.

Since Magnum’s founding in 1947 by Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, George

Rodger, David Seymour and William Vandivert, the prints have always been kept at

the agency’s headquarters, which has moved around Manhattan. But like many other

photo agencies Magnum began digitally scanning its archive many years ago, and

in 2006, the cooperative’s membership voted to begin exploring a sale, whose

proceeds would be used to help reinvent Magnum for a new age.

Then last year, after discussions between Mr. Lubell and various scholarly

institutions around the country, the archive was quietly sold to MSD Capital,

the private investment firm for the family of Michael S. Dell, the computer

tycoon. And the new owners have reached an agreement with the Harry Ransom

Center at the University of Texas at Austin to place it there, for study and

exhibition, for at least the next five years. It will be the first time that the

archive, which for the last several years had been crowded onto shelves at

Magnum’s modest offices on West 25th Street, will be accessible to scholars and

the public.

Thomas F. Staley, the director of the Ransom Center — which has become well

known for its collections of the papers of writers like Edgar Allan Poe, James

Joyce and Don DeLillo — said that it planned to scan every image (Magnum itself

has scanned fewer than half), to begin historical research and to organize

exhibitions centered on portions of the archive.

“It catches so many of the world’s great photojournalists in one fell swoop,”

Mr. Staley said. “These were the best of the best in their field. We want to

make it a research collection. We want to bring scholars in to work in it, time

and time again.”

Neither Magnum nor MSD — made up of Mr. Dell and two managing partners, Glenn R.

Fuhrman and John C. Phelan, both well-known art collectors — would comment about

the price of the sale, which included only the prints. (The image rights will be

retained by the collective’s photographers and their estates.) But a person with

knowledge of the transaction, who was not authorized to discuss it and spoke on

the condition of anonymity, said the Ransom Center had insured the collection

for more than $100 million.

The Magnum archive joins a parade of other collections of vintage photographic

prints, including those of The New York Times and the National Geographic

Society, that have changed hands in the past few years, as publications and

photo agencies, moving aggressively to digitization, have realized they are

sitting on valuable historical property.

Like other photo agencies, Magnum has seen its fortunes decline in recent years,

along with those of the magazines and newspapers that once published the work of

its photographers more regularly. The best known of these pictures went on to

have long financial afterlives, thanks to licensing agreements that placed them

everywhere from television to books and Web sites. But in a world of

camera-phone images, bloggers and inexpensive photojournalism flooding the

Internet, the cooperative’s finances have suffered.

“You could see the handwriting on the wall,” said Mr. Lubell, who took over as

director six years ago, “and the handwriting was shrinking and shrinking.” With

the proceeds from the sale the agency — which represents the work of 13 estates

and 51 current members, including well-known photographers like Bruce Davidson,

Eve Arnold, Susan Meiselas, Martin Parr and Alec Soth — will try to recreate

itself as a media entity on the Web, relying less on publications and more on

its ability to tell its own stories of world events and trends.

The earliest pictures in the archive date from before Magnum’s founding, to the

work of photographers like Capa during the Spanish Civil War. The latest are

from 1998, when the cooperative stopped using press prints as a way to circulate

its images. In between those years are images that make it seem as if a Magnum

photographer was present at almost every significant world event — D-Day, the

civil rights movement, the rise of Fidel Castro — and also around to capture

almost every celebrity and newsmaker: Gandhi, Monroe, Sinatra, Kennedy, Ali.

“For prints that worked this hard and traveled this much, they’re really in

quite good condition,” Mr. Lubell said.

And they are relics from an age of photography that has now almost fully passed.

“Given the technical changes that have taken place in the world of photography,

including the digitization of images,” Mr. Fuhrman of MSD Capital, said in a

statement, “a collection of prints like these will never exist again.”

News Photos, on the

Move, Make News, NYT, 2.2.2010,

https://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/02/

arts/design/02magnum.html

Art Review

America, Captured in a Flash

September 25, 2009

The New York Times

By HOLLAND COTTER

Like probably a zillion other school kids, “My country tears of thee” was the

way I understood the first line of “America.” Maybe that’s the way the

Swiss-born photographer Robert Frank heard it too when he came to the United

States from Europe in 1947, at 22, with English his second, third or fourth

language.

Sadness seems to trickle through the 83 photographs in his classic 1959 book,

“The Americans,” his disturbed and mournful song-of-the-road portrait of a new

homeland and the subject of a 50th-anniversary exhibition now at the

Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Once rejected for its pessimism, now sanctified for its political prescience,

the book distills heartache, anger, fear, loneliness and occasional joy into a

brew that has changed flavor with time but stayed potent. You may not know

exactly what you’re imbibing when you pick up “The Americans” for the first

time, or when you visit the Met show, but a few pictures in, and you’re hooked.

Some images you will recognize even if you never knew where they came from: a

shot of a woman standing in an apartment window, her face hidden by a windblown

American flag; a middle-aged black woman, maybe a nurse, holding a baby with

skin so pale it looks extraterrestrial.

Mr. Frank took those pictures in Hoboken, N.J., and Charleston, S.C. The

photograph used on the cover of the book’s first American edition was from New

Orleans. It’s an exterior shot of a trolley car seen from the side, its

passengers seated in the social order that prevailed in a pre-civil-rights,

pre-feminist, pre-youth-culture nation.

From left to right we see, one behind the other, a white man, a white woman, a

white boy, a white girl, a black man, a black woman. The white woman looks with

sharp-eyed suspicion at the camera; the white boy, impassive but curious, sees

it too; so does the black man, who seems to be on the verge of tears.

I’m reading feelings in here, but I think Mr. Frank was reading them into his

subjects, which is why his pictures, separately and together, feel so personally

laden. At this point, in 1955, he was on the first leg of a transcontinental car

trip that would last 10 months and take him 10,000 miles. He was still learning

the American language, the language of race and class, a stranger in a strange

land that was getting more baffling.

How did he come to be there? Born in a German Jewish family in Zurich in 1924,

he was interested in picture making early on. He apprenticed with several

leading local photographers in his teens; in his early 20s he was doing

promising work, examples of which are in the Met show. But he was

temperamentally restless and impulsive. He needed to leave home, so he headed

for New York.

He was restless there too. He landed a job at Harper’s Bazaar and quickly

ditched it. He left for a photography jaunt to Central and South America, came

back to New York, got married, had a child, went to France and Spain for a

spell, returned to New York again, had another child.

Socially, his impulsiveness worked for him. He was good at introducing himself

to people. That’s how he met Edward Steichen, then curator of photography at the

Museum of Modern Art, and how he later met Walker Evans, who hired him as an

assistant and more or less arranged for him to get a Guggenheim fellowship in

1955. That gave Mr. Frank enough money to travel the country, photographing as

he went, with the goal of producing a book.

He made three separate car trips of different lengths, the first from New York

to Detroit, the second from New York to Savannah, Ga. The third trip, in a

secondhand Ford Business Coupe, was the big one. It took him, with many stops,

through the Deep South and Texas to Los Angeles. There, joined by his family, he

took a breather before heading back east alone, through Montana to Chicago, then

to New York.

The New Orleans picture came fairly early in this trip. It was a miracle that he

got it. He was focused on shooting a parade when he suddenly swung around, and

there was the trolley. Many pictures happened that way. He was in the right

place at the right time, but he also had the right reflexes, a dancer’s

combination of precision and abandon. And he had the right instincts or, maybe,

attitude. For some people a camera is armor. For Mr. Frank it was an antenna, a

feeling and thinking device.

Once back in New York at the end of his travel year, he carried his instincts

and reflexes into the darkroom and onto the editing table. From the many

thousands of pictures he had snapped, he made hundreds of contact sheets; the

Met has a fascinating selection. And from these he pulled around a thousand

working prints, which he tacked to his studio walls and slowly, slowly whittled

down to 100, to 95, to 86, to 83.

That final selection forms the bulk of the show “Looking In: Robert Frank’s ‘The

Americans,’ ” which was organized by Sarah Greenough, senior curator of

photographs at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, and Jeff L. Rosenheim

of the Met’s photography department. As in the book, the sequence begins with

the Hoboken flag and unfolds in four sections, distinguished by mood and tempo.

Images of flags, cars and jukeboxes set up a light, steady under-beat for

recurring character types: socialites and politicians, bikers and retirees,

urban cowboys, hot-to-trot teenagers and just plain folks. A starlet in

Hollywood strikes a pose; three drag queens vamp on a New York City street. A

hard-eyed waitress glares into space; a hotel elevator attendant dreams a

pensive dream as people in furs and suits blur past her.

Occasionally figures appear in landscapes, as in an image of an itinerant

preacher kneeling, robed in white, beside the Mississippi River. Just as often,

landscapes are all but empty. A Montana mining town seen from a window looks

blasted and abandoned; a stretch of New Mexican highway, shot from ground-level,

road-kill perspective, is a blank line to the horizon until you spot a speck of

a car.

A similar road appears in another photograph, though here the car is parked

right in front of us, its headlights on. Through the windshield we see dim

figures — Mr. Frank’s first wife, Mary, and their two children — bundled

together for warmth. Whether they are asleep or sitting in open-eyed exhaustion

is hard to say, they are so shadowy, so near but so far away.

Theirs is the concluding image in “The Americans,” and it is true to the spirit

of the sequence as a whole. It is not a perfect picture in any conventional way.

Its balances are odd; its atmosphere is blurry and grainy, as if with static or

dust. Like many of Mr. Frank’s pictures, it isn’t about an event but about an

uncertain moment between events, when emotional guards are down, and dark

feelings can flow in. In the way a film still does, it seems to call for a

larger narrative to make sense. (In 1958 Mr. Frank announced that he was giving

up still photography for films, and he made many.)

The ostensibly throwaway style of this and other pictures had a huge influence,

from the 1960s forward, on young artists who understood that traditional models

of resolution and wholeness, in art as in life, are unstable, if not illusory.

That “The Americans” could embody this concept while being a virtuosic feat of

formal discipline and psychic endurance only increased its exemplary status,

except perhaps to Mr. Frank himself, now 84, whose attitude toward his book has

tended to grow more antagonistic with its critical and commercial success.

And how does the “The Americans” come across today? In the nominally post-racial

Obama era, its political urgencies feel less immediate than they once did, but

also prophetic. Its mournful tenderness, without being sentimental, seems deeper

than ever. The days and nights it records are more than a half-century gone. The

preacher, the nurse, the woman hidden by the flag, the sharp-eyed woman and the

tearful black man on the trolley are, you imagine, gone.

What’s left is a still-strange country and a book of pictures by a foreigner who

came to America impulsively, traveled our roads restlessly, and by not fully

knowing our language heard it correctly and told us, the way we could not,

truths about ourselves.

“Looking In: Robert Frank’s ‘The Americans’ ”

remains through Jan. 3

at the

Metropolitan Museum of Art;

(212) 535-7710, metmuseum.org.

America, Captured in a

Flash,

NYT, 25.9.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/25/arts/design/25frank.html

Faked Photographs:

Look, and Then Look Again

August 23, 2009

The New York Times

By BILL MARSH

What a marvel the first photographic images must have been to their

early-19th-century viewers — the crisp, unassailable reality of scenes and

events, unfiltered by an artist’s paintbrush or point of view.

And what an opportunity for manipulation. It didn’t take long for schemers to

discover that with a little skill and imagination, photographic realism could be

used to create manufactured realities.

“The very nature of photography was to record events,” said Hany Farid, a

professor of computer science at Dartmouth University and a detective of

photographic fakery. “You’d think there would have been a grace period of

respect for this new technology.”

But the tampering began almost immediately: affixing Lincoln’s head to another

politician’s more regally posed body; re-arranging the grim detritus of Civil

War battlefields to be better composed for the camera; erasing political

enemies.

Sorting icons of truth from icons of propaganda is often a thorny business that

can take decades to resolve, and that’s if it gets resolved. The long-argued

case of Robert Capa’s shocking “Falling Soldier” of 1936, taken during the

Spanish Civil War, has recently flared again. Is this a loyalist soldier in his

fatal moment, or is it staged? A Spanish researcher has scrutinized the terrain

in the photo’s background and determined that it is not an area near Cerro

Muriano, as Capa had said, but another spot, about 35 miles away. Whether this

forces the conclusion that the scene was acted out is being debated with fresh

vigor. (Critics have raised doubts about the photo since the 1970s.)

Questions dogged Joe Rosenthal’s Pulitzer Prize-winning shot of Marines raising

the flag at Iwo Jima from the start — the result of a conversation overheard and

misunderstood, according to Hal Buell, who wrote a book about the image.

The photo was a sensation when it appeared in newspapers in the States. Back on

the war front, someone asked Mr. Rosenthal if his picture had been staged. The

photographer, who did not know which frame had been published, said yes —

referring to a different picture of those same Marines whooping it up for the

camera at Mr. Rosenthal’s request.

Time magazine prepared an article about the alleged set-up that was never

published, but details leaked out and went viral in the manner of the day. Mr.

Buell, the retired head of the Associated Press photo service, says that despite

film of the whole event proving the authenticity of Mr. Rosenthal’s work, a

whiff of controversy stubbornly lives on.

One famous photo has been subject to a mundane form of fakery that it can’t seem

to shake, years later. The photographer John Paul Filo caught the death of a

Kent State student and the anguished reaction it provoked in a young bystander,

and won the Pulitzer Prize for it. But the editors of Life magazine saw room for

improvement, removing a post from behind the bystander’s head to tidy things up

a bit.

The altered image has been published and republished, Mr. Filo lamented, despite

his protests. “The picture keeps on living and working,” he said.

Here is a gallery of historic images, identified by Dr. Farid and other sources,

that have been manipulated or accused of being frauds.

Faked Photographs: Look,

and Then Look Again, NYT, 23.8.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/23/weekinreview/23marsh.html

The Faces in the South Bronx Rubble

August 23, 2009

The New York Times

By DAVID GONZALEZ

By the rivers of Babylon

There we sat down and wept

When we remembered Zion.

Psalm 137

THE afternoon sun dipped low over the empty lots around Charlotte Street.

There in the long shadows stood three boys against a backdrop of smashed bricks,

crumpled beer cans and a busted bike wheel. Behind them, past the tall weeds of

this urban prairie, loomed decrepit apartment buildings.

Yet the trio were grinning, their faces friendly, even goofy. Look closer at the

picture and you can see why they smile: A scrawny mutt’s snout peeks out from

their huddle.

Thirty years ago this summer, I returned to the South Bronx, where I grew up,

with a Yale diploma in one hand and a beat-up Pentax camera in the other. Raised

to get a good education, become a doctor and escape, I had instead come right

back to teach photography — on Charlotte Street, no less, the world’s most

famous slum.

In the four years I had been away, the South Bronx had gone from anonymous to

notorious, a brand name for urban decay and despair. The landscape of my

childhood had vanished, its buildings abandoned, stripped and incinerated.

Private tragedies became public humiliation in 1977. Howard Cosell damned the

place, declaring, “The Bronx is burning,” as the cameras showed fires flickering

beyond Yankee Stadium. Looters picked clean Tremont Avenue’s stores during that

summer’s blackout. President Jimmy Carter made an obligatory pilgrimage — as

Ronald Reagan would during his campaign in 1980 — for a photo-op amid the

rubble.

The only way I could even try to confront this confusion was to slice it up into

snapshots, each frame giving the illusion of a neat answer to inexplicable

questions. For five years, I wandered from Fordham Road to Mott Haven, taking

thousands of pictures in parks, street fairs, stores and even empty lots.

The negatives ended up stuffed in a closet. And the South Bronx was quietly

transformed in the late 1980s by community campaigns that created new homes,

community gardens and smaller schools. I became a journalist and traveled to

Latin America, where I confronted poverty that made New York’s worst look tame.

But I always came back to the Bronx. I have spent much of my professional life

chronicling the same streets I photographed as a young man. Six years ago, I

moved back for good, with my wife and son. Some people thought I was crazy;

cynics swore it hadn’t changed much from the Bad Old Days of 1979.

This year, I dug out the old pictures. The images may be black and white, but to

look back upon them now is to discover that their secrets are revealed in shades

of gray. In a landscape that was written off as uninhabitable — if not

unsalvageable — you can see creativity, faith and even a kind of innocence.

Click. In the middle of a Mott Haven street, a lone couple hugs tightly and

twirls to the music of an unseen orchestra. Squeegee boys dart out among the

land yachts rolling off the Deegan to cadge a quick quarter.

Click. A couple with faces etched by lines depicting a tough journey rest for a

moment, she with her groceries and he with a beer. An artist fills an abandoned

building with lithe torsos made from the charred wood that had choked its

apartments. A blind guitarist sings boleros from a faraway island.

The Bad Old Days?

Where some saw only rubble, life persisted in all of its ordinary glory. Where

many fled in despair, others made a valiant stand. And where outsiders trembled,

those who knew what this had been — and might one day become — clung to an

affection that defied all logic.

•

Click.

Youngsters scramble about a schoolyard, a jumble of shapes and shadows. Close

up, one plays with a toy gun. Now, look past him, beyond the fence.

Desolation.

Community School 61 was about the only occupied building on Charlotte Street

when I arrived in September 1979 to teach photography. It was an old-style

red-brick schoolhouse, unlike the Brutalist concrete learning factories that had

become popular that decade.

The classroom overlooked a heartbreaking panorama of rubble, on streets that had

incongruous names like Suburban or Home. One week, a Hollywood film crew

descended on a nearby block and built a wood-frame church. Just as quickly, they

torched it, so it could serve as a suitably charred ruin for their movie,

“Wolfen.”

The plot revolved around wolves reclaiming the urban wasteland. Right. Then

again, if wolves had actually roamed this area centuries before, one could see

why they were upset with how things had turned out.

Some afternoons, buses rolled down the street and unloaded their nervous cargo.

One by one, tourists stepped out, snapped a few frames of the devastation and

retreated to the safety of their seats behind tinted windows. Off they went,

with snapshots that became props for their tales of derring-do back home.

The pictures taken by my students were anything but despairing. They clicked

happily away in the schoolyard, acting out superhero stories. They snapped their

mothers cooking or their kid sisters sleeping. On Halloween, they ran around in

costumes improvised from baggy skirts and jackets, their faces hidden behind

Groucho glasses.

Before the devastation, this neighborhood had been a familiar backdrop to my own

childhood. A music shop where my father bought guitar strings was on Southern

Boulevard. The furniture store where he paid his weekly tribute for our

plastic-covered sectional sofa was on Prospect Avenue. The five and dime where

my mother worked the lunch counter was on Westchester Avenue.

No matter how far north or west my family moved to outrun the fires, we kept

going back to the South Bronx. When we lived north of Crotona Park we trekked

past Boston Road to visit friends and relatives on our old block on Beck Street.

Halfway between these two neighborhoods, on Southern Boulevard, was the Freeman

Theater, which featured musicals by Mexico’s singing cowboy, Antonio Aguilar. To

a boy like me, raised watching the broken-English bumbling of mustachioed

banditos, Aguilar was a revelation. The Mexicans were the good guys, and Aguilar

was the most heroic of the bunch, proudly singing atop his noble steed. In

Spanish.

Freeman, indeed.

•

The Freeman went dark in the 1970s and was sealed shut with bricks. The blocks

around it grew silent, too, as people left and buildings crumbled. Yet the South

Bronx was anything but quiet. Fire alarms and sirens became so frequent that a

friend joked that you could dance to their frenzied rhythm.

The Walkman was born the year I returned, 1979, but no one wanted a private

soundtrack. Music was communal, binding rebellious teenagers or nostalgic

parents. This was the granddaddy of file sharing: blast it out on the streets.

Old men with accordions and guitars would set up outside bodegas, playing for

beer and companionship. Teenagers with boom boxes perched atop one shoulder like

a bazooka bopped onto subway trains, drowning out the noise of grinding wheels

as the No. 5 train made its tight turn onto Westchester Avenue.

Down by the Hub, the commercial crossroads where several streets cut through

Third Avenue, loose-limbed dancers with fat-laced Puma sneakers and helmetlike

Kangol caps ruled the streets and playgrounds. Felt letters on sweatshirts

declared their allegiances — Rock Steady Crew, Rockwell Association — announcing

to the world the nascent B-boy culture that would help launch hip-hop’s global

assault.

Inside a graffiti-slathered storefront — where a spray-painted gravedigger

walked among the tombstones — B-boys and graffiti writers from the Bronx mingled

with artists and writers from downtown. This common ground was Fashion Moda, an

alternative gallery that became world famous.

The South Bronx was abuzz with creativity, even as policymakers wrote it off.

City officials suggested a policy of gradually cutting services to the worst

neighborhoods. They called it planned shrinkage. It sounded more like thinning

out your family by feeding the kids less each day.

Small surprise that the art from that era mocked the conventional wisdom. Along

Charlotte Street, an artist wrote BROKEN PROMISES on the same buildings that

served as stage sets for politicians who visited to troll for votes.

Inside a tenement near the Hub, a sculptor repopulated the building with figures

made from garbage. The effect was startling: sticklike phantasms leaned against

walls. Their heads were cardboard boxes, painted with big eyes and fierce teeth,

like a shaman’s mask. Instead of incense to invoke the spirits, there was the

pungent funk of mold and garbage, mixed with the burnt aroma of arsons past.

•

A guitarist, his face obscured by sunglasses and a hat, croons tropical love

songs outside a shoe store. Behind him, a mannequin’s arm lifts her skirt,

frozen in a pirouette. In case passers-by were unmoved by the music, his guitar

was emblazoned with “I Am Blind.”

Click.

He was El Cieguito de Lares — the Little Blind Guy from Lares. His Puerto Rican

birthplace was where islanders rebelled against Spain in 1868. It was fitting

that he was on Fordham Road, since that was the Bronx’s Maginot Line, where

businesses, not bunkers, would stop the creeping tide of arson.

Unlike Tremont Avenue, which had been picked clean by looters, Fordham Road

bustled. The movie theaters had yet to be converted into discount clothing

stores. Alexander’s — its huge sign immortalized in the opening moments of “The

Wanderers” — stood sentry.

A few bookstores managed to stay open, as did some old-style candy stores with

fountains. Old Irish ladies with no-nonsense cloth coats, and Jewish ones with

babushkas and beat-up sandals, chatted in the vest-pocket park across the street

from Cye Wells, which probably clothed their sons.

Lapels were wide and pointed, shirts were tight and garish, and none had a

strand of natural fiber. Halfway up the Concourse from Alexander’s, a barber did

brisk business giving young men identical Tony Manero disco haircuts, kept

shell-hard with hot blasts from a dryer and dizzying clouds of hair spray.

Yet on the edges of this world were troubling signs. At playgrounds near Webster

Avenue or parks on Jerome Avenue, young men rushed up to strangers whispering,

“Pillow, sess, nickels and treys,” as they offered fat little manila envelopes

stuffed with pot. Some sales were finalized in restrooms, with the seller

offering a free hit.

The fires that everybody worried would rip past Fordham Road never happened — at

least not the ones that incinerated buildings. Within a decade, thousands of

smaller fires — the kind that set rocks of crack aglow — exacted a deadlier

price.

•

“Hey, mista! Take a pickcha!”

Five boys jostled into the frame, all faces and hands, plastic water pistols

jutting out at odd angles. Minutes later, four girls stood in the same spot,

smiling coquettishly.

Those two pictures were taken on Aug. 10, 1979 — the day I turned 22 — as my

friend Rafa Ramirez and I spent an afternoon at a Mott Haven street fair showing

off the work of other Puerto Rican photographers. We did this a lot, bringing

art to the people as part of our work with En Foco, the Latino photographers’

group that had hired me to teach at C.S. 61.

The children we encountered that day were like so many others from those years.

They would ask — if not demand — that you take their picture. They all had their

poses, filled with mock bravado or impish charm.

I have no idea what became of them. Maybe the boys got caught up in the insane

violence that swept the area when crack wars broke out on those same streets,

riddling hallways and passers-by with volleys of bullets. Maybe the girls became

mothers before they became high school graduates.

Then again, maybe not.

The projects and tenements that lined those streets were home — even in the Bad

Old Days — to people who worked and studied. Others might find it hard to

believe, but lawyers and doctors came from there. Yes, there was poverty and

violence. But there was also life that defied death.

Of all the stories told by these images, there is one that runs through all of

them — my own. They chronicle how I made peace with the past as I figured out

the future.

In the Bad Old Days of 1979, I was an exile in the land of my birth, ashamed of

my neighborhood and myself. When my father died the next year, one of his

friends quietly asked me at the wake, “How’s medical school?” — stunning me with

the realization that Papi never had the heart to admit I had forsaken medicine

for photography.

Three decades later, I’m still making pictures, with both words and cameras. The

landscape is cleaner and safer. For sure, money, health and hope can be in short

supply on some blocks.

But life lingers. Kids play in the street. Music blares from windows. And while

new faces are in old buildings, a few people still remember me. At churches

where I once fidgeted in pews, I drop in for morning Mass, the priest nodding at

me from the altar as I settle in.

Click.

A battered trash can rests outside 858 Beck Street, below the window that was my

— and my parents’ — room. My earliest memory is of sitting on the floor right by

that window. I couldn’t see the garbage. I was too entranced by Papi playing his

guitar.

Whether through sheer luck or providence, the buildings from my childhood

survived the 1970s crucible. Some days, I can drive through every neighborhood I

ever called home, knowing that by the end of my journey, I am happily and

exactly where I should be.

In the Bronx.

The Faces in the South

Bronx Rubble, NYT, 22.8.2009,

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/23/nyregion/23bronx.html

Images, the Law and War

May 17, 2009

The New York Times

By ADAM LIPTAK

WASHINGTON — It was a hypothetical question in a Supreme Court argument, and

it was posed almost 40 years ago. But it managed to anticipate and in some ways

to answer President Obama’s argument for withholding photographs showing the

abuse of prisoners in Iraq and Afghanistan.

What if, Justice Potter Stewart asked a lawyer for The New York Times in the

Pentagon Papers case in 1971, a disclosure of sensitive information in wartime

“would result in the sentencing to death of 100 young men whose only offense had

been that they were 19 years old and had low draft numbers?” The Times’s lawyer,

Alexander M. Bickel, tried to duck the question, but the justice pressed him:

“You would say that the Constitution requires that it be published and that

these men die?”

Mr. Bickel yielded, to the consternation of allies in the case. “I’m afraid,” he

said, “that my inclinations of humanity overcome the somewhat more abstract

devotion to the First Amendment.”

And there it was: an issue as old as democracy in wartime, and as fresh as the

latest dispute over pictures showing abuse of prisoners in the 21st century. How

much potential harm justifies suppressing facts, whether from My Lai or Iraq,

that might help the public judge the way a war is waged in its name?

The exchange also contained more than a hint of the court’s eventual calculus:

The asserted harm can’t be vague or speculative; it must be immediate and

concrete. It must be the sort of cost that gives a First Amendment lawyer pause.

As it happened, Mr. Bickel’s response outraged the American Civil Liberties

Union and other allies of the newspaper in the Pentagon Papers case, which

concerned the Nixon administration’s attempt to prevent publication of a secret

history of the Vietnam War. They disavowed Mr. Bickel’s answer and said the

correct response was, “painfully but simply,” that free people are entitled to

evaluate evidence concerning the government’s conduct for themselves.

Which is a good summary of the interest on the other side: Scrutiny of abuses by

the government enhances democracy because it promotes accountability and prompts

reform.

Justice William O. Douglas, in a 1972 dissent in a case about Congressional

immunity, described his view of the basic dynamic. “As has been revealed by such

exposés as the Pentagon Papers, the My Lai massacres, the Gulf of Tonkin

‘incident,’ and the Bay of Pigs invasion,” he wrote, “the government usually

suppresses damaging news but highlights favorable news.”

Indeed, the Nixon administration successfully opposed the use of the Freedom of

Information Act to obtain the release of documents and photographs concerning

the killings of hundreds of South Vietnamese civilians in 1968 at My Lai. (The

decision led Congress to broaden that law.)

Disclosure of abuses can also provoke a backlash. The indelible images that

emerged from the Vietnam War helped turn the nation against the war, and may

have steeled America’s enemies. And earlier photographs of abuse at the Abu

Ghraib prison in Iraq were used for propaganda and recruitment by insurgents

there.

How, then, to apply the lessons of history and law to the possible disclosure of

additional images of prisoner mistreatment by Americans in the current wars?

On Wednesday, when Mr. Obama announced that the government was withdrawing from

an agreement to comply with court orders requiring release of the images, he

said there was little to learn from them and much to fear. But he offered

speculation on both sides of the balance.

“The publication of these photos would not add any additional benefit to our

understanding of what was carried out in the past by a small number of

individuals,” he said. “In fact, the most direct consequence of releasing them,

I believe, would be to further inflame anti-American opinion and to put our

troops in greater danger.”

The first assertion, which the Bush administration also made, is not universally

accepted. In a 2005 decision ordering the release of the images, Judge Alvin K.

Hellerstein of the Federal District Court in Manhattan said they may provide

insights into whether the abuses shown were indeed isolated and unauthorized.

And the claim that harm would follow disclosure — that terrorists, for example,

would exact revenge — is hard to measure or prove. “The terrorists in Iraq and

Afghanistan do not need pretexts for their barbarism,” Judge Hellerstein wrote.

In the Pentagon Papers case, too, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of

publication, saying, in essence, that speculation about potential harm was not

sufficient.

There are, of course, profound differences between the two cases. One concerned

the constitutionality of a prior restraint against publishing information

already in the hands of the press; the other is about whether civil rights

groups are entitled to obtain materials under the Freedom of Information Act.

But both involve contentions that serious harm would follow from publication.

Justice Stewart’s answer, in his concurrence in the 6-to-3 decision, was that

assertions are not enough. “I cannot say,” he wrote, that disclosure “will

surely result in direct, immediate and irreparable damage to our nation or its

people.” In other contexts, too, the Supreme Court has endorsed limits on speech

only when it would cause immediate and almost certain harm to identifiable

people. More general and diffuse consequences have not done the trick.

In 1949, for instance, the court overturned the disorderly conduct conviction of

a Chicago priest whose anti-Semitic speech at a rally had provoked a hostile

crowd to riot. Free speech, Justice Douglas wrote, “may indeed best serve its

high purpose when it induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with

conditions as they are or even stirs people to anger.”

Fear of violence, however, was enough to persuade many people that publication

of cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad should be discouraged or forbidden.

Andrew C. McCarthy, a former federal prosecutor who has handled terrorism cases,

said the only prudent course in the current case is to withhold the images. “If

you’re in a war that’s been authorized by Congress, it should be an imperative

to win the war,” he said. “If you have photos that could harm the war effort,

you should delay release of the photos.”

But Jameel Jaffer, a lawyer with the civil liberties union, said history favored

disclosure, citing the 2004 photographs from Abu Ghraib and the 1991 video of

police beating Rodney King in Los Angeles.

But the touchstone remains the Pentagon papers case. It not only framed the

issues, but also created a real-world experiment in consequences.

The government had argued, in general terms, that publication of the papers

would cost American soldiers their lives. The papers were published. What

happened?

David Rudenstine, the dean of the Cardozo Law School and author of “The Day the

Presses Stopped,” a history of the case, said he investigated the aftermath with

an open mind.

“I couldn’t find any evidence whatsoever from any responsible government

official,” he said, “that there was any harm.”

Images, the Law and War,