|

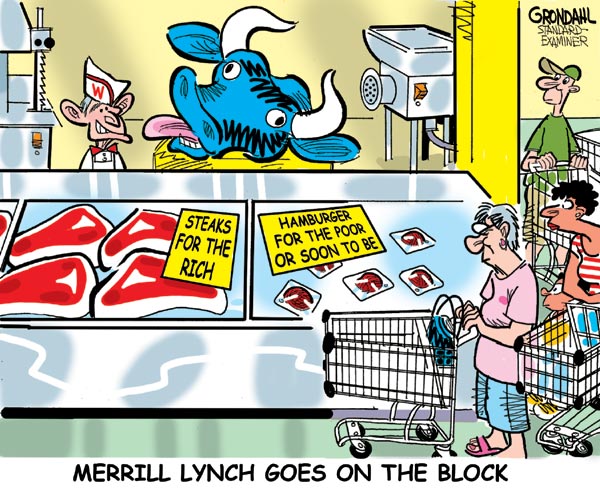

History > 2008 > USA > Poverty (I)

Cal Grondahl

Utah

Standard Examiner

Cagle

18.9.2008

L: US President George W. Bush.

Al Meyerhoff,

Legal Voice for the Poor,

Dies at 61

December 25, 2008

The New York Times

By STEVEN GREENHOUSE

Al Meyerhoff, a leading labor, environmental and civil rights lawyer who

brought a landmark case to stop sweatshop conditions for 30,000 workers on the

Pacific island of Saipan, died on Sunday in Los Angeles, where he lived. He was

61.

The cause was complications of leukemia, his wife, Marcia Brandwynne, said.

Mr. Meyerhoff, a loud, friendly bear of a man with a thick mane of tousled hair,

rose to prominence in several legal fields. As a civil rights litigator, he

successfully challenged a California law that prevented illegal immigrant

children from attending public school. As an environmental lawyer — he worked

for the Natural Resources Defense Council for 17 years — he challenged the

continued use of cancer-causing pesticides.

As a labor lawyer, he was co-lead counsel in suing Gap, Nordstrom, Ralph Lauren

and 20 other retailers, accused of obtaining garments from Saipan factories that

used guard dogs and had barbed-wire fences. Many of the workers, some of whom

Mr. Meyerhoff said were indentured servants, were immigrants from China who had

paid several thousand dollars to work in Saipan and were forced to toil 12 hours

a day, seven days a week, often without overtime pay.

“Saipan is America’s worst sweatshop,” Mr. Meyerhoff said in an interview with

The New York Times in 1999, referring to the island in the Northern Marianas

Islands, an American commonwealth near the Philippines. The lawsuit was one of

the most ambitious ever brought against sweatshops, sending a signal to

sweatshop owners in dozens of countries to improve conditions.

As part of the $20 million settlement, the apparel companies agreed to pay back

wages, follow a code of workplace conduct and pay for an independent monitor to

inspect the Saipan factories. Mr. Meyerhoff waived any fees.

Over the decades, Mr. Meyerhoff produced numerous op-ed articles for The Los

Angeles Times and The Huffington Post Web site, many letters in The New York

Times and The Washington Post and articles in law journals and environmental

magazines. He also testified 50 times before Congressional committees.

“I was meant to do this work,” Mr. Meyerhoff told online magazine of the Cornell

University Law School this year.

Albert Henry Meyerhoff Jr. was born in Ellington, Conn., on Sept. 20, 1947. He

told the Cornell Web magazine that as a boy he was harassed by bullies and that

as a result he developed “an active dislike of the abuse of power.”

Mr. Meyerhoff graduated from the University of Connecticut in 1969 and from the

Cornell law school in 1972. After law school, he turned down a high-paying

corporate law job to take a $60-a-week position with California Rural Legal

Assistance, which represented migrant workers and the rural poor. In one

lawsuit, he challenged the University of California over its underwriting of

research on farm mechanization, saying it hurt farm workers and family farms.

In 1981 Mr. Meyerhoff joined the Natural Resources Defense Council and became

director of its public health program. He helped pressure the chemical industry

to adopt tougher standards on pesticides by invoking a rarely used amendment

under the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act that prohibited the use of animal

carcinogens in processed foods. His litigation helped persuade the industry to

ban several dozen carcinogenic pesticides.

In 1988, he joined Coughlin Stoia, a class action law firm, from which he

brought the Saipan lawsuit, sued Enron and challenged Mexican cross-border

trucking, asserting that it violated United States health and safety standards.

Besides his wife, he is survived by his daughter, Leah, of New York City, his

mother, Ruth, of Ellington, Conn., and his brothers, George of Van Nuys, Calif.,

and Alan of Panama City, Fla.

“He was a warrior against the chemical industry,” Frances Beinecke, president of

the N.R.D.C., said of Mr. Meyerhoff. “He was a champion of the underserved. He

fought long and hard to make the world a safer place for farm workers, for kids,

for people working in factories and for people living in poverty who couldn’t

represent themselves.”

Al Meyerhoff, Legal

Voice for the Poor, Dies at 61, NYT, 25.12.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/25/business/25meyerhoff.html

Uninsured Put a Strain on Hospitals

December 9, 2008

The New York Times

By REED ABELSON

As increasing numbers of the unemployed and uninsured turn to

the nation’s emergency rooms as a medical last resort, doctors warn that the

centers — many already overburdened — could have even more trouble handling the

heart attacks, broken bones and other traumas that define their core mission.

Even before the recession became evident, many emergency rooms around the

country were already overcrowded, with dangerously long waits for some patients

and the frequent need to redirect ambulances to other hospitals.

“We have no capacity now,” said Dr. Angela F. Gardner, the president-elect of

the American College of Emergency Physicians, which represents 27,000 emergency

doctors. “There’s no way we have room for any more people to come to the table.”

In a report to be released Tuesday, her group warns that the nation’s system of

emergency rooms is in “serious condition.” Dr. Gardner argues that any public

discussion of overhauling the current health system must include the nation’s

emergency departments.

The number of patients coming to emergency departments has been steadily

increasing. Helping push up that volume have been the growing ranks of the

uninsured, because emergency rooms are legally obliged to see all patients who

enter their doors, regardless of their ability to pay. But even insured patients

who have no quick access to regular doctors are also showing up — among them

older people, who represent the fastest growing population of emergency room

visitors.

So far, there are no firm figures on the recent influx. But even two years ago,

when a government survey found that the annual volume of visits to emergency

departments had reached 120 million — a third higher than a decade earlier —

doctors considered many emergency rooms overburdened.

Now the recession, whose full impact is yet to be seen, threatens to make

conditions even worse, emergency doctors say. Hospitals are absorbing increasing

amounts in unpaid medical bills, and some are already experiencing much higher

numbers of patients without insurance.

For example, Denver Health, a public hospital system, had a 19 percent increase

in emergency visits by uninsured patients in November — to 3,325, up from 2,792

a year earlier.

“Virtually every time I work a nine-hour shift, I encounter a couple of patients

who have never been here before because they’ve just lost their insurance,” said

Dr. Vincent J. Markovchick, the director of the hospital’s emergency medical

services.

They include patients like Matthew Armijo, 29, who was laid off from his client

services job at a technology company in August and could continue his health

insurance only through October. He showed up at Denver Health’s urgent care

center, a part of the emergency department, suffering from increasing abdominal

pain. Mr. Armijo said he went there because he would not have to pay anything.

Denver Health expects the amount of care it delivers for which it will never be

paid to grow to more than $300 million this year, compared with $276 million in

2007.

Some patients are people who have delayed seeking medical care as long as they

can, like those who arrive during an asthma attack after deferring treatment.

“I am definitely seeing patients coming in presenting worse in their illness

because they are further along,” said Dr. Katherine A. Bakes, the director of

the program’s emergency services for children.

Other doctors around the country also report treating people who seem to have no

other option. One emergency room doctor in Iowa, Dr. Thomas E. Benzoni, said he

recently saw a mother come in with her two children for what he thought was

routine care. When he asked her why she had not gone to her family doctor, she

said she did not have health insurance.

“I don’t know what else she was supposed to do,” Dr. Benzoni said.

The increase is not affecting all emergency rooms. Some emergency physicians, in

fact, said there had actually been a recent decline in visits. A report by the

American Hospital Association for July, August and September found a slight

overall decrease in hospital traffic, including emergency visits, as some people

apparently sought to avoid spending money on anything they did not deem

absolutely essential.

But as the recession continues, many officials of the college of emergency

doctors predict it is only a matter of time until the rising number of uninsured

and the delays in getting primary care create a crisis.

“I think we’re seeing the tip,” said Dr. Nicholas J. Jouriles, the group’s

current president. Patients, he said, will have no choice but to come to the

emergency department when they have no money or insurance. “They will get turned

away elsewhere,” he said.

One of the doctors’ major concerns is the long waits by patients requiring a

hospital bed. The doctors group, surveying its members last year, learned of at

least 200 deaths related to the practice of “boarding” — in which patients on

stretchers line the corridors until they can be moved into a bed.

“Crowding is a national public health problem,” said Dr. Jesse M. Pines, an

emergency physician in Philadelphia.

Patients forced to wait for hours on end for a bed clearly suffer.

“It was pure hell,” recalled Robert Roth, whose 90-year-old mother, Kato, last

year spent 36 hours at the emergency department of a Queens hospital, near her

home in Jackson Heights, waiting for a room after going to the emergency room in

the middle of the night. Mrs. Roth, who had a recent series of falls, said she

had been hearing music in her ears, and both her son and the doctor he called

were worried about a possible stroke.

After the first five hours of waiting, she became increasingly disoriented and

delusional. Mr. Roth was unable to stay with her during the entire wait. After

he left and returned, he said, the hospital staff told him they had no idea

where she was. She turned up in an empty room off the emergency department, and

her physical and mental condition had clearly deteriorated, Mr. Roth said. She

believed that she had been kidnapped.

When she had to go several weeks later to another emergency department in

Manhattan, she endured a 20-hour wait for a room, again becoming disoriented

after several hours, forcing her to be sedated.

The emergency staffs “just seemed overwhelmed, overwhelmed,” said Mr. Roth, who

wondered why emergency departments could not handle the elderly in a special

fashion.

Dr. Ann S. O’Malley is a physician and senior researcher for the Center for

Studying Health System Change, a nonprofit group in Washington that has studied

emergency services in different communities. While some hospitals have taken

steps to reduce crowding and move patients more efficiently from the emergency

department into rooms, Dr. O’Malley said, others have responded by expanding

their facilities — attracting more patients.

“Emergency departments,” she said, “are a kind of barometer of the general

health of the rest of the system.”

Dr. Eric J. Lavonas, an emergency physician in Denver, said: “The nation’s

emergency rooms are the end of the line. We will strain and stretch and bulge

under the weight.”

Dr. Gardner, of the emergency doctors’ group, said the question now is whether

the emergency room safety net will break — how often people with heart attacks

will not be able to get care in time to be saved. Her group’s report, she said,

is meant to alert people to the precarious nature of the system.

“What they don’t understand,” she said, “is that the system is fundamentally

flawed and will fail.”

Melinda Sink contributed reporting from Denver.

Uninsured Put a

Strain on Hospitals, NYT, 9.12.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/09/business/09emergency.html

Governors Urge Obama

to Help The Poor,

Boost Economy

December 2, 2008

Filed at 1:03 p.m. ET

The New York Times

By REUTERS

PHILADELPHIA (Reuters) - U.S. state governors urged President-elect Barack

Obama on Tuesday to pump money into infrastructure and help support the poor as

a sinking economy hits state budgets hard.

Obama, who takes over from President George W. Bush on January 20, pledged to

involve states in his plans to tackle the U.S. recession and create or save 2.5

million jobs.

The president-elect has spent much of the time since his November 4 victory over

Republican John McCain forming his economic team and advocating a massive new

stimulus package.

"I'm not simply asking the nation's governors to help implement our economic

recovery plan, I'm going to be interested in having you help draft and shape

that economic plan," Obama told a meeting that included Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin,

the former Republican vice-presidential candidate.

"I'm going to listen to you, especially when we disagree because one of the

things that has served me well in my career is discovering that I don't know

everything," Obama said.

The meeting came the day after the National Bureau of Economic Research

confirmed that the United States had entered recession in December 2007. The

downturn, which many economists expect to persist through the middle of the next

year, is already third-longest since the Great Depression.

Pennsylvania Gov. Ed Rendell, touted as a possible energy secretary in the Obama

administration, opened the meeting by pressing for Congress to extend

unemployment benefits and increase food stamp availability.

"Those are things that don't go to us as governors, don't go to our budgets but

help our citizens," he said.

Rendell said on Monday governors would ask for $136 billion in infrastructure

funds to stimulate the economy immediately and cover health care for the poor.

Obama acknowledged that, unlike the federal government, U.S. states had to

balance their budgets. He said immediate measures were needed to help deal with

the crisis.

"Forty-one of the states that are represented here are likely to face budget

shortfalls this year or next, forcing you to choose between reining in spending

and raising taxes," Obama said. "To solve this crisis and to ease the burden on

our states, we need action and we need action swiftly."

Nearly all 50 governors attended, including California's Arnold Schwarzenegger,

who on Monday declared a fiscal emergency and called lawmakers into a special

session to tackle a widening budget gap.

(Editing by Alan Elsner)

(additional reporting by Deborah Charles and Lisa Lambert

Governors Urge Obama to

Help The Poor, Boost Economy, NYT, 2.12.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/reuters/washington/politics-us-usa-obama.html

Editorial

Sewing Up the Safety Net

November 27, 2008

The New York Times

Largely missing from the discussion about the faltering economy is the

recession’s impact on the 37 million Americans who are already living at or

below the poverty line — and the millions more who will inevitably join their

ranks as the downturn worsens.

Poverty and joblessness go hand in hand. If unemployment rises in the coming

year from today’s 6.5 percent to 9 percent, as some analysts predict, another

7.5 million to 10.3 million people could become poor, according to a new study

by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

The prospect of nearly 50 million Americans in poverty is even more daunting

when one considers the holes that have been punched in the safety net over the

last quarter-century. Since the Reagan administration, the federal government

has steadily reduced its role in curtailing poverty, or even in coordinating

state and local efforts to help alleviate it.

Meanwhile, most states reduced or eliminated cash assistance for single poor

adults and limited access to food stamps. Stricter eligibility requirements keep

thousands of people from collecting jobless benefits. Facing budget deficits,

cash-strapped states will be tempted to cut social programs even more. The

experience of being poor in America, never easy, will soon become even more

difficult for more people — unless Congress boosts food stamps, modernizes the

unemployment compensation system and takes other steps to strengthen the ability

of the federal and state governments to help the millions who will need

assistance.

This is all the more important since the current poverty statistics

significantly understate reality. The federal yardstick used to gauge poverty is

severely outdated, giving too much weight to some factors in a typical family

budget, like the cost of food, and not counting others, like the cost of child

care and out-of-pocket medical costs. It also doesn’t consider regional

differences in the cost of living and doesn’t include the cost of child care,

taxes or the value of noncash benefits such as food stamps or tax credits.

The National Academy of Sciences years ago recommended a new measure of poverty

that takes such variables into account. But the revised framework has never been

adopted because, among other reasons, it would add several million more people

to the ranks of the poor.

If there was ever a time for more precise measurements, it is now. Better

numbers will produce a better understanding of poverty, and will enhance

Washington’s ability to respond in the difficult days ahead.

Sewing Up the Safety

Net, NYT, 27.11.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/27/opinion/27thu3.html

States

forced

to cut health coverage for poor

28.10.2008

USA Today

By Julie Appleby

Economic

troubles are forcing states to scale back safety-net health-coverage programs —

even as they brace for more residents who will need help paying for care.

Many cuts

affect Medicaid, which pays for health coverage for 50 million low-income adults

and children nationwide, including nearly half of all nursing home care. The

joint federal-state program is a target because it consumes an average 17% of

state budgets — the second-biggest chunk of spending in most states, right

behind education.

"Medicaid

programs across the U.S. are going to be severely damaged," says Kenneth Raske,

president of the Greater New York Hospital Association. He expects some

hospitals nationwide may drop services and some hospitals and nursing homes may

lay off employees.

Among the cuts:

• Hawaii this month halted funding for a 7-month-old program aimed at covering

all the state's uninsured children.

• South Carolina Gov. Mark Sanford must decide by Thursday whether to sign a

budget that would slash $160 million in health care, including an 8.1% cut to

Medicaid and a 10.8% cut to the Department of Mental Health. Programs to help

autistic children, the elderly who need prescription drugs and low-income

workers may be hit.

• California in July cut payments to hospitals 10% under its Medicaid program,

Medi-Cal. It had planned to restore 5% in March, but Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger

has called an emergency legislative session Nov. 5 to deal with

lower-than-expected revenues.

Health care is a likely target, says Jan Emerson of the California Hospital

Association, who expects more hospitals to drop out of Medi-Cal if extra cuts

occur. Less than half the state's hospitals currently contract with Medi-Cal.

They treat Medi-Cal patients in their ERs, but then transfer them to other

hospitals.

• Massachusetts this month cut $293 million from its Medicaid budget, including

$40 million from the Cambridge Health Alliance for care it already provided to

low-income residents. The alliance, which runs three hospitals and dozens of

clinics, says that cut plus other state cuts could total an amount equal to the

cost of 650 full-time employees — or 20% of its workforce. "We can't absorb that

without some serious re-evaluation of what we do," spokesman Doug Bailey says.

"Everything is on the table."

The cuts follow several years of strong budgets and state efforts to bring

health coverage to more low-income adults and children.

"When the economy goes down, states have increased pressure (from more

uninsured), yet have to curtail plans to broaden coverage," says Diane Rowland,

executive vice president of the Kaiser Family Foundation, a non-partisan think

tank.

For every 1% jump in unemployment, about 1 million more people enroll in

Medicaid, the group found in September.

Lawmakers in at least 27 states are facing budget gaps just months after dealing

with some of the largest shortfalls since the recession in 2001, reports the

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a Washington think tank. States can only

make Medicaid cuts that affect people covered under optional state programs,

such as children whose families earn slightly more than federal guidelines

require.

"We're expecting budget gaps for the rest of this year and into fiscal 2010 to

be about $100 billion," says Elizabeth McNichol, a senior fellow at the center.

"Health care gets hit hard when states have to cut back."

States forced to cut health coverage for poor, UT,

28.10.2008,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/2008-10-28-health-cuts_N.htm

U.S. Reports Drop in Homeless Population

July 30,

2008

The New York Times

By RACHEL L. SWARNS

WASHINGTON

— The number of chronically homeless people living in the nation’s streets and

shelters has dropped by about 30 percent — from 175,914 to 123,833 — from 2005

to 2007, Bush administration officials said on Tuesday.

Housing officials say the statistics, which are collected annually from more

than 3,800 cities and counties, may reflect better data collection and some

variation in the number of communities reporting. But officials also attribute

much of the decline to a policy shift promoted by Congress and the

administration that has focused federal and local resources on finding stable

housing for homeless people suffering from drug addiction, mental illness or

physical disabilities, long deemed the hardest to help in the homeless

population.

Under the strategy, known as “housing first,” local officials have over the last

eight years increasingly placed the chronically homeless into permanent shelter

— apartments, halfway houses or rooms — and provided them with services for drug

addiction, mental illness and health problems.

Until cities and states began adopting the plan, many homeless people seemed to

shuttle endlessly between emergency shelters, hospitals and the street.

Officials and housing experts say the “housing first” program has begun to

stabilize the chronically homeless population, which the administration defines

as disabled individuals who have been continuously homeless for more than a year

or have experienced at least four episodes of homelessness in the past three

years.

Researchers who study the issue say they believe the decline is the most

significant in years.

“We can all be encouraged that we’re making progress in reducing chronic street

homelessness,” the housing secretary, Steven C. Preston, said. “But we must also

recognize that we have a long way to go to find a more lasting solution for

those struggling with homelessness every day.”

Some advocates for the homeless criticized the administration’s focus on the

chronically homeless, saying that homeless families and those who live on the

margins — in motels or doubled up with friends and family — are falling behind.

In New York City, for instance, the number of chronically homeless people

dropped to 5,233 in 2007 from 7,002 in 2005, statistics show. The total number

of homeless people increased to 50,372 from 48,154 during that time.

Nationally, chronically homeless people account for about 18 percent of the

homeless population.

“We should be focused on ending homelessness for everybody, not just a small

segment of the homeless population,” said Michael Stoops, the acting director of

the National Coalition for the Homeless, an advocacy group based here, who said

homeless families needed additional resources.

Mr. Stoops said he remained concerned that cities and states were undercounting

the homeless. And he said that federal cuts in financing for affordable housing

programs had left the country unprepared for the waves of people struggling to

find housing after losing homes to foreclosure.

But Martha R. Burt, a research associate at the Urban Institute here who has

studied homelessness for more than two decades, described the decline in chronic

homelessness as “nothing short of phenomenal.”

“These are the people who everyone thought were hopeless: the undeserving poor,”

Ms. Burt said. “They’re not hopeless. You can get them into housing, and for the

most part they will not go back into the street if they have the right

supportive services.”

The Department of Housing and Urban Development collects the statistics as part

of its Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress. Nationally, the total

number of homeless people counted on a single night in January — the measure

used to count homeless families on the streets and in shelters — dropped to

666,295 in 2007, from 754,147 in 2005.

The report said that 1.6 million people spent time in homeless shelters between

Oct. 1, 2006 and Sept. 30, 2007. Seventy percent of those people were

individuals; the rest were families with children. About 13 percent of all

homeless adults living in shelters were veterans.

Dennis P. Culhane, a professor of social policy at the University of

Pennsylvania and an author of this year’s report, acknowledged that “a lot of

people in tough housing situations don’t get counted.” Mr. Culhane said the

government needed a standard measure and counted only people living in shelters

or on the street.

Mr. Culhane attributed much of the decline in chronic homelessness to the

efforts of Congress, administration officials and local communities. In 1999,

Congress told HUD to direct about one-third of its financing for homelessness to

permanent housing.

Meanwhile, federal and local officials embraced the focus on the chronically

homeless. HUD has financed the development of 10,000 to 12,000 new units of

supported housing for that population every year over the past four years, Mr.

Culhane said.

“We’re moving in the right direction, without a doubt,” he said.

Representative Maxine Waters, Democrat of California and chairwoman of the House

Subcommittee on Housing and Community Opportunity, said more money was needed

for homeless families and children.

“While this is great news,” Ms. Waters said, “we cannot rest because there is

much that remains to be done.”

U.S. Reports Drop in Homeless Population, NYT, 29.7.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/30/us/30homeless.html

Related >

http://www.hudhre.info/documents/3rdHomelessAssessmentReport.pdf

Drop in

homeless count seen

as 'success story'

28 July

2008

USA Today

By Wendy Koch

The U.S.

had 12% fewer homeless last year than in 2005, and the greatest decline occurred

among those who chronically live on the streets or in emergency shelters,

according to a federal report to be released Tuesday.

"This is a

success story," says Dennis Culhane, a University of Pennsylvania professor and

co-author of the report by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

(HUD). He attributes the decline to better tracking and to increased efforts to

house the "chronically homeless" — disabled adults who are continuously homeless

for at least a year.

The number of people on the street or in emergency shelters on a single night in

January, the month in which the tally was taken, fell from 763,010 in 2005 to

671,888 last year, the report says. Most were homeless temporarily. Among those

who were chronically homeless, the number fell from 175,914 in 2005 to 123,833

in 2007.

"This reduction is the largest documented decrease in homelessness in our

nation's history," says Philip Mangano, executive director of the U.S.

Interagency Council on Homelessness, which coordinates federal efforts. He says

it shows that the increase in housing units for the long-term homeless, funded

by HUD and communities, is working.

Homeless advocates say the data, which come from 3,800 cities and counties that

receive HUD funds, do not count every homeless person and do not reflect this

year's weaker economy.

"Chronic homelessness may be down, but the non-chronic population is

increasing," says Michael Stoops, acting executive director of the National

Coalition for the Homeless, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group. He says

he's getting reports of shelters filling with families that have lost homes to

foreclosure.

A lot of people become homeless when they are forced to choose between paying

for food and gas, which have sharply increased in cost this year, or housing,

says Nan Roman, president of the National Alliance to End Homelessness, a

non-profit group.

"These are tough times," says Culhane, adding that homeless numbers often

reflect the economy. He says this year's homeless data, which HUD is starting to

receive for January, paints a "mixed" picture of increases in some areas, such

as Connecticut, and decreases in others, including New York City.

Mangano sees an upside to the weak housing market, saying foreclosures create

opportunities for communities to buy properties at lower prices to use as

shelters.

For the first time, HUD's report includes a count of people using shelters or

transitional housing during a full year. From October 2006 to September 2007,

1.6 million people sought help for homelessness. Of those, 69% were men, 64%

were minorities, and 30% were in families.

Drop in homeless count seen as 'success story' , UT,

28.7.2008,

http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2008-07-28-homeless_N.htm

Letters

To Help

Those on the Lowest Rungs

June 22,

2008

The New York Times

To the

Editor:

Re “After

75 Years, the Working Poor Still Struggle for a Fair Wage,” by Adam Cohen

(Editorial Observer, June 17):

While raising the minimum wage is necessary, it is not sufficient to improve the

financial well-being of most low-wage workers.

Government policy makers must learn from the positive effects of the

welfare-to-work strategies of the Clinton administration. The support services

provided to those who leave welfare are valuable for many other groups that

employers are reluctant to hire, including those with criminal records.

In addition, an expansion and strengthening of vocational programs at community

colleges is crucial to skill development and wage growth.

The government must also reduce the phasing out of benefits from the earned

income tax credit and food stamps so that wage increases are not offset by the

reduction in benefits from these and other means-tested programs.

A comprehensive strategy, with a higher minimum wage as its foundation, can

enable many families to distance themselves from poverty.

Robert Cherry

Brooklyn, June 17, 2008

The writer is a professor of economics at Brooklyn College.

•

To the Editor:

The minimum wage isn’t only a matter of assisting the working poor. It’s also a

matter of assisting the broader middle class and achieving a more fair and

equitable wage distribution.

According to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Current Population

Survey, after New York State increased its minimum wage to $6.75 an hour from $6

in 2006, the median wage also rose for those who had been earning up to at least

91 percent over the state minimum wage and most likely rose above that.

Meanwhile, in those states that still had the federal minimum wage of $5.15 an

hour, the median wages of those making up to at least 91 percent over the

minimum wage were stagnant.

The real opposition from businesses to raising the minimum wage comes from the

obligation they feel to raise the wages of those who earn somewhat more than the

statutory minimum wage.

Given that a minimum wage that keeps up with, say, the rate of inflation may put

an end to wage stagnation at the bottom of the wage distribution and among the

lower middle class, the overall welfare benefits cannot be overstated.

Oren M. Levin-Waldman

New York, June 17, 2008

The writer is a professor of public policy at Metropolitan College.

•

To the Editor:

We commend Adam Cohen for calling attention to the importance of the minimum

wage and for pointing out that in real dollars, that wage is worth far less than

it was in the 1960s.

Mr. Cohen rightly notes that public work supports, like the earned income tax

credit and subsidized health insurance, are also effective ways to help low-wage

workers. But another issue — child care — also needs our attention.

Good care is unaffordable even for many middle-income families — in nearly every

state, center-based care for two children costs more than the state’s median

rent.

Research is clear that providing children with high-quality care in their

earliest years improves school achievement, which, down the road, means a

stronger work force.

In addition to higher wages and health insurance, our nation should make

affordable child care for all families a priority.

Nancy K. Cauthen

New York, June 17, 2008

The writer is deputy director, National Center for Children in Poverty at

Columbia University.

To Help Those on the Lowest Rungs, NYT, 22.6.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/22/opinion/l22wage.html

Food

Stamps Buy Less, and Families Are Hit Hard

June 22,

2008

The New York Times

By LESLIE KAUFMAN

Making ends

meet on food stamps has never been easy for Cassandra Johnson, but since food

prices began their steep climb earlier this year, she has had to develop new

survival strategies.

She hunts for items that are on the shelf beyond their expiration dates because

their prices are often reduced, a practice she once avoided.

Ms. Johnson, 44, who works in customer service for a medical firm, knows that

buying food this way is not healthy, but she sees no other choice if she wants

to feed herself and her 1-year-old niece Ammni Harris and 2-year-old nephew

Tramier Harris, who live with her.

“I live paycheck to paycheck,” said Ms. Johnson, as she walked out of a market

near her home in Hackensack, N.J., pushing both Ammni and the week’s groceries

in a shopping cart. “And we’re not coping.”

The sharp rise in food prices is being felt acutely by poor families on food

stamps, the federal food assistance program.

In the past year, the cost of food for what the government considers a minimum

nutritional diet has risen 7.2 percent nationwide. It is on track to become the

largest increase since 1989, according to April data, the most recent numbers,

from the United States Department of Agriculture. The prices of certain staples

have risen even more. The cost of eggs, for example, has increased nearly 20

percent, and the price of milk and other dairy products has risen 10 percent.

But food stamp allocations, intended to cover only minimum needs, have not

changed since last fall and will not rise again until October, when an increase

linked to inflation will take effect. The percentage, equal to the annual rise

in prices for the minimum nutritional food basket as measured each June, is

usually announced by early August.

Some advocates and politicians say that this relief will not come soon enough

and will probably not be adequate to keep pace with inflation.

Stacy Dean, the director of food assistance for the Center on Budget and Policy

Priorities, a Washington social issues research and advocacy organization,

estimates that the rising food prices have resulted in two fewer bags of

groceries a month for the families most reliant on the program.

“We know food stamps are falling short $34 a month” of the monthly $576 that the

government says it costs a family of four to eat nutritional meals, she said.

“The sudden price increases on top of everything else like soaring fuel and

health care have meant squeeze and strain that is unprecedented since the late

1970s.”

The declining buying power of food stamps has not gone unrecognized in

Washington. In May, Congress passed a farm bill that would raise the minimum

amount of food stamps that families receive, starting in October. The bill,

which was passed over President Bush’s veto, will also raise for the first time

since 1996 the amount of income that families of fewer than four can keep for

costs like housing or fuel without having their benefits reduced.

This month, a coalition led by Representative Jesse Jackson Jr. called on

Congress to immediately enact a temporary 20 percent increase in food stamps.

Officials at the Agriculture Department, which administers the program, say

there is no precedent for such an action. Families on food stamps have been hit

hard across the nation, but perhaps not as hard as families in New York, where

food costs are substantially higher than prices almost everywhere else,

including other urban areas, according to the Food Research and Action Center, a

research and advocacy group in Washington.

The more than one million New Yorkers on food stamps receive on average $107 a

month in assistance, which is slightly higher than the average for the rest of

the country. But it is not enough to close the gap in food costs, experts say.

Poor families interviewed in the New York area say that they are not going

hungry — thanks in large part to the city’s strong network of 1,200 soup

kitchens and food pantries — but that they have really felt the pinch. To cope,

many say, they are doing without the basics.

June Jacobs-Cuffee of Brooklyn shares $120 a month in food stamps with her

19-year-old epileptic son. She says that even after her once-a-month trip to the

food pantry at St. John’s Bread & Life in Brooklyn, she has had to give up red

meat and is also cutting back on buying fresh fruits and sticking instead with

canned goods and fruit cocktail.

“It is not a question of running out, yet,” she said. “But it does require very

careful budgeting.”

The most recent census data showed that from 2003 to 2006 an average of 1.3

million New Yorkers identified themselves as “food insecure,” meaning that they

were worried about being able to buy enough food to keep their families

adequately fed. City officials are concerned that the food price increase has

caused that number to increase significantly.

“I am much more worried about the state of hunger in New York City than I was 6

or 12 months ago,” said Christine C. Quinn, the City Council speaker. Ms. Quinn

said that food pantries were increasingly complaining about being tapped out.

She added, “What we are hearing from constituents is that they are having to

make tougher and tougher decisions like to water down milk for kids or not

purchase medication to keep money for food.”

Yessenia Villar, who lives in Washington Heights and works tutoring children in

Spanish and English, knows about tough choices. She says it is getting harder to

stretch her monthly $190 in food stamps to cover food for herself, her mother

and her 5-year-old daughter. At the end of the month, she runs out of oil, rice

and, most painful of all, plantains, which have gone from five for $1 to two for

$1, she says.

She says she has stopped buying extras like summer sandals for herself, and has

also given up treats like cookies and ice cream for her daughter. “I used to

make all my groceries for $150 a month and then have a little extra,” she said.

“Now it is, like, crazy.”

Nate Schweber contributed reporting.

Food Stamps Buy Less, and Families Are Hit Hard, NYT,

22.6.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/22/nyregion/22food.html?hp

Editorial

Observer

After

75 Years, the Working Poor Still Struggle for a Fair Wage

June 17,

2008

The New York Times

By ADAM COHEN

At the

height of the Great Depression, industry convinced President Franklin Roosevelt

and Congress to enact a law allowing companies to collude to drive up prices. To

balance out this giveaway to big business, the law gave workers something that

they had long been fighting for: the first federal minimum wage.

This week marks the 75th anniversary of the National Industrial Recovery Act —

which Roosevelt signed June 16, 1933, at the end of his famous first 100 days —

and of the federal minimum wage. It was a grudging, almost accidental win, and

the road since then has been rocky. Advocates for low-income workers have had a

hard time keeping the minimum wage at a reasonable level and passing other laws

necessary to fulfill the original goal: ensuring that people who work hard can

achieve a reasonable standard of living.

When progressives set out to establish a national minimum wage, they faced stiff

opposition. Industry insisted that government should not interfere with its

relations with its employees. Organized labor was also opposed. (“If you give

them something for nothing,” one labor leader objected, “they won’t join the

union.”) The pro-business Supreme Court presented the biggest obstacle, ruling

that minimum wages were unconstitutional.

The Depression provided an opening. Progressives injected minimum-wage and

maximum-hours provisions into the NIRA. These provisions were technically

voluntary, but if companies wanted the government to approve the minimum prices

and production limits they desperately wanted, they had to agree to minimum

wages. Most industries adopted a minimum hourly wage of at least 40 cents.

The Supreme Court declared the NIRA unconstitutional, but the idea of a federal

minimum wage had taken hold. In 1938, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards

Act — which a more progressive Supreme Court upheld — creating a mandatory

federal minimum wage.

The new law was enormously effective: within a year, it brought millions of

low-paid workers up to a wage of 30 cents an hour. It also had major weaknesses,

notably that it was not indexed to inflation. Congress has to raise it, which

leaves low-income workers at the mercy of politics.

The minimum wage continues to have powerful enemies. Businesses that pay low

wages lobby strongly against increases, arguing that they cause jobs to

disappear. The Bush administration has been hostile. When Elaine Chao was

nominated to be the next labor secretary, she called for states to be able to

opt out of the federal minimum wage — which would destroy the whole idea of a

national minimum wage.

Last year, the new Democratic-controlled Congress raised the minimum wage for

the first time in 10 years. The increase was a real victory. But even with it,

the minimum wage — which reaches $7.25 an hour in 2009 — is still far below

where it was in the 1960s, in real dollars. A family of three earning the 2009

minimum wage would still be well below the federal poverty line. And because the

minimum wage remains unindexed, low-wage workers will fall even further behind

before Congress rouses itself to grant another increase.

Economists, who are more sophisticated today than they were in 1933, now place

more emphasis on raising the Earned Income Tax Credit. Because it is tied to

family income rather than wage levels, the tax credit can be targeted precisely

at workers who need it most. There has also, understandably, been considerable

focus this year on trying to provide the working poor — and everyone else — with

affordable health care.

In this year’s “change” election, more attention should be paid to the working

poor, who were hit especially hard by the economic policies of the last eight

years. There should be talk of tax credits and health care — and the minimum

wage. Advocates for the working poor argue for a better raise than the one

Congress passed last year — perhaps one set at half the national average hourly

wage, which would bring it roughly to where it was in the 1960s, and tie it to

the rate of inflation.

The minimum wage can play a vital role in lifting hard-working families above

the poverty line. But as Roosevelt understood, it is also about something

larger: what kind of country America wants to be. “A self-supporting and

self-respecting democracy,” he said in the Congressional message that

accompanied the Fair Labor Standards Act, can plead “no economic reason for

chiseling workers’ wages.”

After 75 Years, the Working Poor Still Struggle for a Fair

Wage, NYT, 17.6.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/17/opinion/17tue4.html?ref=opinion

In Food

Price Crunch, More Americans Seek Help

May 7, 2008

Filed at 7:26 a.m. ET

By REUTERS

The New York Times

BALTIMORE

(Reuters) - Carolyn Stanley, a single mother with five children, receives $327

in food stamps each month to feed her family. With prices for staples like bread

and cheese going ever higher, each month is harder than the last.

She buys hot dogs over higher-quality meat and feeds her kids cereal, but even

with other government support she often has to seek help from local churches and

from friends.

"The food runs out somewhere within the middle of the month, or getting close to

the end," said Stanley, 49. "It is not easy. I pray."

While food inflation is causing tensions and riots around the world, even the

affluent United States is being touched. Stories such as Stanley's are becoming

more common as Americans increasingly turn to food stamps and other programs to

make ends meet.

At a cost of about $39 billion to the U.S. Treasury, nearly one in 10 Americans

-- 28 million people -- are expected next year to use food stamps, which would

be the highest enrolment in the program apart from a spike after the Gulf Coast

hurricanes of 2005.

U.S. food prices are expected to rise by up to 5 percent this year, part of a

global trend driven fueled by consumption in rapidly developing countries such

as China, adverse weather, and the funneling of food crops to make biofuels.

"People don't want to talk about hunger in America because that's not supposed

to have happened. Didn't we take care of that a generation or two ago?" said

Kevin McGuire, Food Stamp director for Maryland. "Well, not really." The number

of beneficiaries jumped 12 percent in Maryland from a year ago.

MAKING ENDS

MEET

The crunch comes as the economy takes a sharp turn for the worse and many see

the number of people receiving food stamps as advance indicator of an economic

slump.

Today, food stamp officials are not only watching more people apply for the

benefits, they're seeing more of them come from the working poor, people whose

low-wage jobs still leave them eligible under the program's strict income caps.

"Having a job isn't enough anymore. Having two or three jobs isn't enough

anymore," said Marcia Paulson, spokeswoman for Great Plains Food Bank in North

Dakota, where nearly half the households on food stamps have at least one adult

with a job.

"Our pantries are overwhelmed," said Diane Doherty, director of the Illinois

Hunger Coalition, which helps the needy find food assistance and sign up for

food stamps.

Doherty said people's food stamps are running out more quickly due to higher

prices -- often within two weeks. More than ever are receiving stamps for the

first time, she said.

"They're just not able to make ends meet when they're trying to raise a family

on these meager salaries, with the cost of housing and now with the cost of

gas," she said.

Maryland's McGuire is one official who believes that the annual adjustments in

food stamp dollars have been inadequate.

Nationally, the average benefit per person early this year was about $100 per

month -- around $1 a meal.

The government will adjust that payout in June, but people won't see their

benefits change until October.

Stanley, who receives no child support for her daughters, the youngest of whom

is in the first grade, hopes that federal officials will act more quickly.

"If you've ever lived the crunch of that poverty level, you would understand

that people need more," Stanley said.

OUTREACH

PARTLY BEHIND GROWING ROLLS

Program officials are quick to stress that food stamps were never intended to

make up a family's entire food budget, and point to other programs that can help

needy families -- school lunches, after-school programs, and food banks.

"We firmly believe that no American should go hungry," said Kate Houston, a

deputy undersecretary at USDA.

The growing rolls of food stamp beneficiaries is a mixed picture, Houston said,

reflecting in part a success in reaching out to eligible people who hadn't

received help in the past.

"The program is designed to expand and contract based on economic conditions,"

she said.

House and Senate lawmakers, forging a final compromise on a giant agriculture

law, now plan to add over $10 billion to the food stamp program over the next

decade, raising the standard income deduction, boosting the minimum benefit to

$14 a month, an increase of $4, and giving more to food pantry donations.

Food stamp officials are counseling people on how to make their stamps last as

long as possible -- buying ground beef or other meat when it's on sale and

freezing it, for example.

That may be cold comfort for people like Sandra Fowler, 42, a mother in suburban

Chicago who recently applied for food stamps, and describes her situation as

increasingly desperate.

Fowler is months behind on mortgage payments on her house and is going through a

messy divorce.

"It will feed my children, at least. I've been going to a food pantry, waiting

in line. The choices are really limited -- there might be some eggs, canned

goods," she said.

Most experts predict that high crop and fuel prices will linger for at least two

to three years, and sky-high oil and gasoline prices are unlikely to abate any

time soon.

Even in the country known as the 'land of plenty,' McGuire said, the cost crunch

"affects literally at a gut level what's going on" for the less fortunate.

"We're going to need to start stitching the safety net a little bit bigger."

(Reporting by Missy Ryan; Additional reporting by Andrew Stern in Chicago and

Carey Gillam in Kansas City; Editing by Russell Blinch and Eddie Evans.)

In Food Price Crunch, More Americans Seek Help, NYT,

7.5.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/reuters/world/lifestyle-usa-poverty-foodstamps.html

Downturn

Reviving Rift Over ’96 Welfare Change

April 11,

2008

The New York Times

By PETER S. GOODMAN

In the

summer of 1996, President Bill Clinton delivered on his pledge to “end welfare

as we know it.” Despite howls of protest from some liberals, he signed into law

a bill forcing recipients to work and imposing a five-year limit on cash

assistance.

As first lady, Hillary Rodham Clinton supported her husband’s decision, drawing

the wrath of old friends from her days as an advocate for poor children. Some

accused the Clintons of throwing vulnerable families to the winds in pursuit of

centrist votes as Mr. Clinton headed into the final stages of his re-election

campaign.

Despite the criticism and anxiety from the left, the legislation came to be

viewed as one of Mr. Clinton’s signature achievements. It won broad bipartisan

praise, with some Democrats relieved that it took a politically difficult issue

off the table for them, and many liberals came to accept if not embrace it.

Mrs. Clinton’s opponent in the race for the Democratic presidential nomination,

Senator Barack Obama, said in an interview that the welfare overhaul had been

greatly beneficial in eliminating a divisive force in American politics.

Mrs. Clinton, now a senator from New York, rarely mentions the issue as she

battles for the nomination, despite the emphasis she has placed on her

experience in her husband’s White House.

But now the issue is back, pulled to the fore by an economy turning down more

sharply than at any other time since the welfare changes were imposed. With

low-income people especially threatened by a weakening labor market, some

advocates for poor families are raising concerns about the adequacy of the

remaining social safety net. Mrs. Clinton is now calling for the establishment

of a cabinet-level position to fight poverty.

As social welfare policy returns to the political debate, it is providing a

window into the ways in which Mrs. Clinton has navigated the legacy of her

husband’s administration and the ideological crosscurrents of her party.

In an interview, Mrs. Clinton acknowledged that “people who are more vulnerable”

were going to suffer more than others as the economy turned down. But she put

the blame squarely on the Bush administration and the Republicans who controlled

Congress until last year. Mrs. Clinton said they blocked her efforts, and those

of other Democrats, to buttress the safety net with increased financing for

health insurance for impoverished children, child care for poor working mothers,

and food stamps.

Mrs. Clinton expressed no misgivings about the 1996 legislation, saying that it

was a needed — and enormously successful — first step toward making poor

families self-sufficient.

“Welfare should have been a temporary way station for people who needed

immediate assistance,” she said. “It should not be considered an anti-poverty

program. It simply did not work.”

During the presidential campaign, she has faced little challenge on the issue,

in large part because Mr. Obama has supported the 1996 law. “Before welfare

reform, you had, in the minds of most Americans, a stark separation between the

deserving working poor and the undeserving welfare poor,” Mr. Obama said in an

interview. “What welfare reform did was desegregate those two groups. Now,

everybody was poor, and everybody had to work.”

Mr. Obama called the resulting law “an imperfect reform.” Like Mrs. Clinton, he

called for an expansion of government-provided health care, child care and job

training to assist women making the transition from welfare to work — programs

he says he helped expand in Illinois as a state senator.

Asked if he would have vetoed the 1996 law, Mr. Obama said, “I won’t second

guess President Clinton for signing.”

Among some advocates for the poor, the growing prospect of a severe recession

and evidence of backsliding from the initial successes of the policy shift have

crystallized fresh concern. Many remain upset that Mrs. Clinton, once seemingly

a stalwart member of their camp, supported a law that they contend left many

people at risk.

“If there is no national controversy about welfare reform, we paid an awfully

high price,” said Peter Edelman, a law professor at Georgetown University who

has known Mrs. Clinton since her college days, and who quit his post as

assistant secretary of social services at the Department of Health and Human

Services in protest after Mr. Clinton signed the measure.

“They don’t acknowledge the number of people who were hurt,” Mr. Edelman said.

“It’s just not in their lens. It was predictably bad public policy.”

Forcing families to rely on work instead of government money went well from 1996

to 2000, when the economy was booming and paychecks were plentiful, economists

say. Since then, however, job creation has slowed and poverty has risen. The

current downturn could be the first serious test of how well the changes brought

about by the 1996 law hold up under sharp economic stress.

“We should have enormous concern about the lack of a fully functioning safety

net for families with children,” said Mark H. Greenberg, director of the Poverty

and Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress, a liberal research

group.

In many ways, Mrs. Clinton has sought to moderate her liberal image since

leaving the White House. But on welfare, she has faced the opposite problem:

accusations from some liberals that she sold out their principles for a

politically calculated centrism.

On the campaign trail, Mrs. Clinton is largely focused on the middle class.

Since the departure from the Democratic race of John Edwards, who had made

poverty a centerpiece of his campaign, there has been little debate about social

welfare policy. But in promising on Friday to establish a cabinet-rank

poverty-fighting position if she is elected, Mrs. Clinton reintroduced the topic

and the question of her record.

In the interview, conducted last month, Mrs. Clinton said she had followed

through on her promise to address what she viewed as shortcomings in the welfare

law after being elected to the Senate in 2000. She said she had pressed for

legislation that would have increased financing for child care for poor mothers

by up to $11 billion, seeking to expand food stamps, and allowing welfare

recipients to draw cash aid while attending school.

Those provisions were blocked by the Republican leadership.

“We’ve had to mostly spend our time since President Bush came in to office

preventing bad things from happening,” Mrs. Clinton said.

Many welfare advocates dispute Mrs. Clinton’s characterization. Since entering

the Senate, they say, she has shown a predilection for compromise at the expense

of the poor.

When the overhaul bill came up for reauthorization, Sandra Chapin, a former

welfare recipient affiliated with a coalition called Welfare Made a Difference,

lobbied Congress to allow more women to attend college while they received aid.

Mrs. Clinton “wouldn’t have anything to do with it,” Ms. Chapin said.

Ms. Chapin, now program director of the Consumer Federation of California,

posted an e-mail message to a discussion board in February accusing Mrs. Clinton

of having “had a hand in devaluing motherwork in this country, and no doubt

sending thousands of children and their families deeper into poverty.”

In the interview, and in her memoir, Mrs. Clinton said she had serious

misgivings about some of the changes proposed to the welfare system as the issue

percolated through Washington in the mid-1990s.

Her husband had taken office with a pledge to dismantle the old system. He

embraced time limits for cash aid and allowing states to largely decide for

themselves how to spend the money. He set out to expand job training, access to

health care, child care and food stamps.

When the Republicans took over Congress after the 1994 elections, making Newt

Gingrich the House speaker, they seized the initiative. Twice, they passed bills

seeking to impose time limits on welfare benefits while cutting other aid.

Twice, Mr. Clinton vetoed the bills, with the encouragement of Mrs. Clinton.

In August 1996, three months before Election Day, Congress sent the White House

a third bill. This one imposed time limits on cash benefits and barred most

legal immigrants from receiving welfare. But it maintained guarantees for

Medicaid and food stamps and increased financing for child care. This time, Mr.

Clinton signed.

“I agreed that he should sign it and worked hard to round up votes,” Mrs.

Clinton wrote in her memoir.

Mrs. Clinton remained troubled by parts of the bill, she wrote in her memoir,

particularly the provision barring welfare for legal immigrants. But “pragmatic

politics” had to be considered. “If he vetoed welfare reform a third time,” she

wrote, “Bill would be handing the Republicans a potential political windfall.”

Marian Wright Edelman, the founder of Children’s Defense Fund, an activist group

that had given Mrs. Clinton her first job, blasted the Clintons as betraying the

poor, opening a rift that Mrs. Clinton called “sad and painful.” Mrs. Edelman’s

husband, Peter, quit his administration post.

In the years that followed, the number of those on welfare rolls plummeted by

more than 60 percent. A study last year by the Congressional Budget Office found

that from 1991 to 2005, poor families with children saw their inflation-adjusted

incomes climb by 35 percent, as employment climbed.

In recent years, however, low-skilled women have struggled. The percentage of

poor single mothers neither working nor drawing cash assistance surged from

under 20 percent before the welfare overhaul to more than 30 percent in 2005,

according to the Congressional Research Service. During the same period, the

number of children in poverty rose to 12.8 million from 11.6 million, according

to census data.

Downturn Reviving Rift Over ’96 Welfare Change, NYT,

11.4.2008,

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/11/us/politics/11welfare.html?hp

Poor get poorer as recession threat looms: report

Wed Apr 9, 2008

4:26am EDT

Reuters

By Lisa Lambert

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - The gap between rich and poor in many states has

broadened at a quickening pace since the last U.S. recession, which could make

it difficult for low-income families to weather the current economic downturn,

according to a report issued Wednesday.

Since the late 1990's average incomes have declined 2.5 percent for families on

the bottom fifth of the country's economic ladder, while incomes have increased

9.1 percent for families on the top fifth, said the report from the

liberal-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and Economic Policy

Institute.

The result is that the average incomes of the top five percent of families are

12 times the average incomes of the bottom 20 percent.

"The report's bottom line is that since the late 1980's income gaps widened in

37 states and have not narrowed in any states," said Jared Bernstein, one of the

report's authors. "In fact, we've found that the trend toward growing inequality

has accelerated during this decade."

Meanwhile, the middle class has remained virtually stagnant, with average

incomes growing by just 1.3 percent in nearly eight years, the report said.

The report drew from 20 years of U.S. Census Bureau data collected from 1987

through 2006 on post-federal tax changes in real incomes, and is one of the few

to record income inequality on a state-by-state basis. It did not include

capital gains and losses in its calculations.

The technology boom and economic expansion of the late 1990's put many

lower-income families in better positions at the start of the 2001 economic

downturn than they are in now, when many economists say a downturn has begun,

Bernstein said.

Elizabeth McNichol, another author of the report, said wages grew before the

2001 recession, but they did not increase much during the past several years of

recovery. In a conference call with reporters, she pointed to Connecticut, which

has had the greatest increase in income inequality since the 1980's, according

to the report.

In Connecticut, incomes of the wealthiest 20 percent are eight times those of

the poorest 20 percent, according to the report. New York has the greatest

disparity, with incomes of the top 20 percent 8.7 times the bottom ones,

followed by Alabama, where the top are 8.5 times the bottom.

Only recently has Connecticut begun recovering from the downturn of six years

ago, according to Douglas Hall, associate director of research for Connecticut

Voices for Children, who participated in the call. By August 2007 the state

gained enough jobs to make up for those lost in the last recession, he said, but

now it is losing them again.

Even though the study did not include capital gains, Bernstein said the effects

of booming wealth on Wall Street for most of this decade did contribute to the

spread between incomes, showing up as higher salaries.

Some have criticized income inequality studies. Writing for the conservative

Cato Institute last year, Alan Reynolds said tax law changes skew the numbers.

For example, executives once took stock options that were taxed as capital gains

but now take nonqualified stock options that are taxed as salaries.

Bernstein said that if the report had considered capital gains, the disparities

would have likely been greater, as capital gains generally affect higher-income

people.

(Reporting by Lisa Lambert, Editing by Chizu Nomiyama)

Poor get poorer as

recession threat looms: report, R, 9.4.2008,

http://www.reuters.com/article/domesticNews/idUSN0838901420080409

Food

Stamp Use at Record Pace as Jobs Vanish

March 31,

2008

The New York Times

By ERIK ECKHOLM

Driven by a

painful mix of layoffs and rising food and fuel prices, the number of Americans

receiving food stamps is projected to reach 28 million in the coming year, the

highest level since the aid program began in the 1960s.

The number of recipients, who must have near-poverty incomes to qualify for

benefits averaging $100 a month per family member, has fluctuated over the years

along with economic conditions, eligibility rules, enlistment drives and natural

disasters like Hurricane Katrina, which led to a spike in the South.

But recent rises in many states appear to be resulting mainly from the economic

slowdown, officials and experts say, as well as inflation in prices of basic

goods that leave more families feeling pinched. Citing expected growth in

unemployment, the Congressional Budget Office this month projected a continued

increase in the monthly number of recipients in the next fiscal year, starting

Oct. 1 — to 28 million, up from 27.8 million in 2008, and 26.5 million in 2007.

The percentage of Americans receiving food stamps was higher after a recession

in the 1990s, but actual numbers are expected to be higher this year.

Federal benefit costs are projected to rise to $36 billion in the 2009 fiscal

year from $34 billion this year.

“People sign up for food stamps when they lose their jobs, or their wages go

down because their hours are cut,” said Stacy Dean, director of food stamp

policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities in Washington, who noted

that 14 states saw their rolls reach record numbers by last December.

One example is Michigan, where one in eight residents now receives food stamps.

“Our caseload has more than doubled since 2000, and we’re at an all-time record

level,” said Maureen Sorbet, spokeswoman for the Michigan Department of Human

Services.

The climb in food stamp recipients there has been relentless, through economic

upturns and downturns, reflecting a steady loss of industrial jobs that has

pushed recipient levels to new highs in Ohio and Illinois as well.

“We’ve had poverty here for a good while,” Ms. Sorbet said. Contributing to the

rise, she added, Michigan, like many other states, has also worked to make more

low-end workers aware of their eligibility, and a switch from coupons to

electronic debit cards has reduced the stigma.

Some states have experienced more recent surges. From December 2006 to December

2007, more than 40 states saw recipient numbers rise, and in several — Arizona,

Florida, Maryland, Nevada, North Dakota and Rhode Island — the one-year growth

was 10 percent or more.

In Rhode Island, the number of recipients climbed by 18 percent over the last

two years, to more than 84,000 as of February, or about 8.4 percent of the

population. This is the highest total in the last dozen years or more, said Bob

McDonough, the state’s administrator of family and adult services, and reflects

both a strong enlistment effort and an upward creep in unemployment.

In New York, a program to promote enrollment increased food stamp rolls earlier

in the decade, but the current climb in applications appears in part to reflect

economic hardship, said Michael Hayes, spokesman for the Office of Temporary and

Disability Assistance. The additional 67,000 clients added from July 2007 to

January of this year brought total recipients to 1.86 million, about one in 10

New Yorkers.

Nutrition and poverty experts praise food stamps as a vital safety net that

helped eliminate the severe malnutrition seen in the country as recently as the

1960s. But they also express concern about what they called the gradual erosion

of their value.

Food stamps are an entitlement program, with eligibility guidelines set by

Congress and the federal government paying for benefits while states pay most

administrative costs.

Eligibility is determined by a complex formula, but basically recipients must

have few assets and incomes below 130 percent of the poverty line, or less than

$27,560 for a family of four.

As a share of the national population, food stamp use was highest in 1994, after

several years of poor economic growth, with an average of 27.5 million

recipients per month from a lower total of residents. The numbers plummeted in

the late 1990s as the economy grew and legal immigrants and certain others were

excluded.

But access by legal immigrants has been partly restored and, in the current

decade, the federal and state governments have used advertising and other

measures to inform people of their eligibility and have often simplified

application procedures.

Because they spend a higher share of their incomes on basic needs like food and

fuel, low-income Americans have been hit hard by soaring gasoline and heating

costs and jumps in the prices of staples like milk, eggs and bread.

At the same time, average family incomes among the bottom fifth of the

population have been stagnant or have declined in recent years at levels around

$15,500, said Jared Bernstein, an economist at the Economic Policy Institute in

Washington.

The benefit levels, which can amount to many hundreds of dollars for families

with several children, are adjusted each June according to the price of a

bare-bones “thrifty food plan,” as calculated by the Department of Agriculture.

Because food prices have risen by about 5 percent this year, benefit levels will

rise similarly in June — months after the increase in costs for consumers.

Advocates worry more about the small but steady decline in real benefits since

1996, when the “standard deduction” for living costs, which is subtracted from

family income to determine eligibility and benefit levels, was frozen. If that

deduction had continued to rise with inflation, the average mother with two

children would be receiving an additional $37 a month, according to the private

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Both houses of Congress have passed bills that would index the deduction to the

cost of living, but the measures are part of broader agriculture bills that

appear unlikely to pass this year because of disagreements with the White House

over farm policy.

Another important federal nutrition program known as WIC, for women, infants and

children, is struggling with rising prices of milk and cheese, and growing

enrollment.

The program, for households with incomes no higher than 185 percent of the

federal poverty level, provides healthy food and nutrition counseling to 8.5

million pregnant women, and children through the age of 4. WIC is not an

entitlement like food stamps, and for the fiscal year starting in October,

Congress may have to approve a large increase over its current budget of $6

billion if states are to avoid waiting lists for needy mothers and babies.

Food Stamp Use at Record Pace as Jobs Vanish, NYT, 31.3.2008,http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/31/us/31foodstamps.html?hp

Washington’s Grand Experiment to Rehouse the Poor

March 21,

2008

The New York Times

By ERIK ECKHOLM

WASHINGTON

— When District of Columbia officials tore down the decrepit housing project in

southeast Washington where Samantha Jackson lived with her teenage son, they

promised that they would build a more attractive, mixed-income community and

that former tenants like herself could come back.

“I was very happy,” recalled Ms. Jackson, 42, a school custodian. “The area was

rough and scary.”

Ms. Jackson, who has been staying with a friend since the demolition in 2004, is

now in line to buy, with subsidies, a new apartment in a town house in the same

neighborhood, and she can hardly wait. “It looks like Hollywood to me,” Ms.

Jackson said of the onetime slum where glossy buildings and the Washington

Nationals stadium are also rising.

Bucking national trends and citing what they call “a moral goal,” District of

Columbia officials have pledged to preserve and even expand low-income housing,

replacing dangerous projects with new communities that keep both poor and “work

force” residents — firefighters, teachers and laborers — in the mix.

The redevelopment of the Arthur Capper and Carrollsburg projects, where Ms.

Jackson lived, is the first in the country to promise replacement of all

low-income units within the same neighborhood, said Michael Kelly, director of

the city Housing Authority.

“Mr. Kelly is undertaking a great experiment to see if he can turn around

distressed neighborhoods and keep the original residents there to benefit,” said

Sue Popkin, a housing expert at the Urban Institute. “It’s a gamble. We don’t

know how to take a terrible neighborhood and make it nice while keeping the same

people there.”

The federal government no longer pays to build housing projects, which in

Washington, Chicago and other cities became symbols of concentrated poverty.

Since the early 1990s, it has given money under a program called Hope VI to tear

down distressed projects, to be replaced by mixed communities built with private

partners. In a pattern that critics disparage as “demolish and disperse,” some

former tenants return but most scatter with rental vouchers, destroying

community ties. District officials say they have learned from past mistakes.