|

Vocapedia >

USA > U.S. Constitution

1791 > First Amendment > Free

speech

Clay Bennett

political cartoon

GoComics

September 20, 2025

https://www.gocomics.com/claybennett/2025/09/20

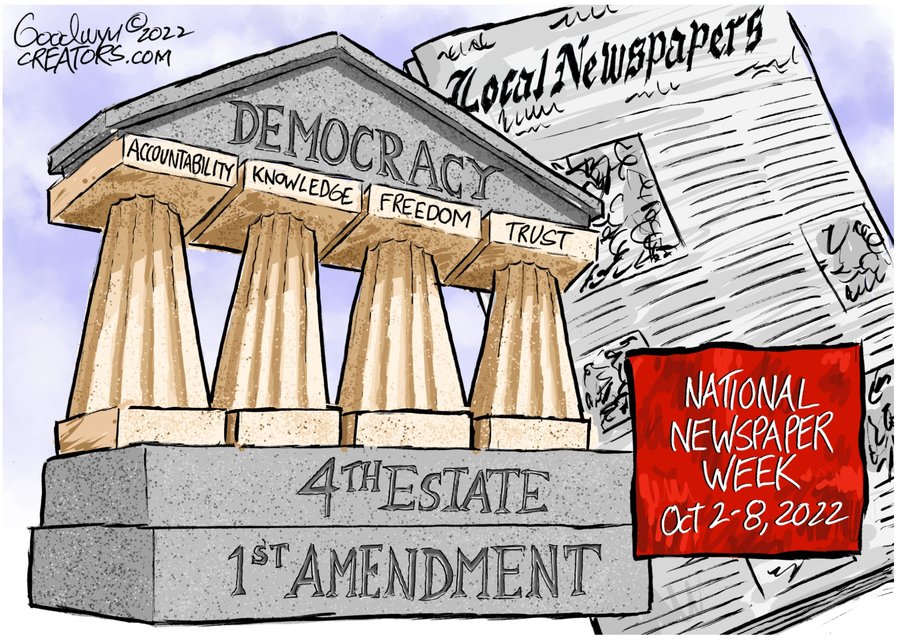

Al Goodwyn Editorial Cartoons

Al Goodwyn

political cartoon

GoComics

October 2, 2022

https://www.gocomics.com/algoodwyn/2022/10/02

Phil Hands

political cartoon

GoComics

Jun. 3,

2017

https://www.gocomics.com/phil-hands/2017/06/03

United States Constitution > First Amendment / Amendment I

Congress shall make no law

respecting an establishment of religion,

or

prohibiting the free exercise thereof;

or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press;

or the right of the people peaceably to assemble,

and to petition the government

for a redress of grievances.

https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/first_amendment

https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/First_amendment

USA >

Freedom of Speech

in the United

States / free speech / free speech rights

First Amendment guarantee of free speech

First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

UK / USA

It is worth noting here the important distinction

between what the First Amendment protects

(freedom from government restrictions on expression)

and the popular conception of free speech

(the affirmative right to speak your mind in public,

on which the law is silent).

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/18/

opinion/cancel-culture-free-speech-poll.html

https://www.nytimes.com/topic/subject/

first-amendment-us-constitution

2025

https://www.gocomics.com/claybennett/2025/09/20

https://www.gocomics.com/bill-bramhall/2025/09/20

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/09/19/

opinion/trump-freedom-of-speech-crackdown-kimmel.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/28/

opinion/free-speech-trump-maga.html

2023

https://www.npr.org/2023/08/14/

1193813087/kansas-newspaper-raid-police-chief-investigation

https://www.npr.org/2023/08/14/

1193676139/newspaper-marion-county-kansas-police-raid-first-amendment

https://www.npr.org/2023/07/05/

1186108696/social-media-us-judge-ruling-disinformation

https://www.npr.org/2023/03/27/

1166343615/supreme-court-immigration-free-speech

2022

https://www.gocomics.com/algoodwyn/2022/10/02

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/22/

us/politics/alex-jones-trial.html

https://www.gocomics.com/clayjones/2022/05/30

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/18/

opinion/cancel-culture-free-speech-poll.html

2021

https://www.npr.org/2021/06/23/

1001382019/supreme-court-rules-

cheerleaders-f-bombs-are-protected-by-the-first-amendment

https://www.npr.org/2021/04/28/

991683886/frightened-to-death-

cheerleader-speech-case-gives-supreme-court-pause

https://www.npr.org/2021/04/28/

988083256/at-supreme-court-mean-girls-meet-1st-amendment

https://www.npr.org/2021/04/05/

984440891/justice-clarence-thomas-takes-aims-

at-tech-and-its-power-to-cut-off-speech

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/06/

opinion/trump-lies-free-speech.html

2020

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/03/

opinion/facebook-trump-free-speech.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/02/

opinion/george-floyd-protests-first-amendment.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/19/

opinion/coronavirus-first-amendment-protests.html

2019

https://www.npr.org/2019/06/24/

732512169/supreme-court-strikes-down-ban-on-trademarking-

immoral-scandalous-words-symbols

https://www.npr.org/2019/03/22/

705739383/trump-and-universities-in-fight-

over-free-speech-federal-research-funding

2018

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/01/

opinion/first-amendment-liberals-conservatives.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/23/

business/media/trump-twitter-block.html

https://www.npr.org/2018/03/20/

593675135/abortion-and-freedom-of-speech-

a-volatile-mix-heads-to-the-supreme-court

https://www.npr.org/2018/01/23/

579884628/victims-of-neo-nazi-troll-storm-find-difficulties-

doing-something-about-it

https://www.npr.org/2018/01/03/

571647322/students-identify-with-50-year-old-supreme-court-case

2017

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/07/

obituaries/les-whitten-muckraking-columnist-and-novelist-dies-at-89.html

https://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2017/11/07/

562619874/first-amendment-advocates-charge-trump-cant-block-critics-on-twitter

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/27/

opinion/twitter-first-amendment.html

http://www.npr.org/2017/08/26/

546167516/police-struggle-to-balance-public-safety-with-free-speech-during-protests

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/08/19/

544684355/bostons-free-speech-rally-organizers-deny-links-to-white-nationalists

http://www.npr.org/2017/06/04/

531314097/alt-right-white-nationalist-free-speech-the-far-rights-language-

explained

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/08/12/

542982015/home-to-university-of-virginia-prepares-for-violence-

at-white-nationalist-rally

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/07/12/

536842197/lawsuit-says-

its-unconstitutional-for-president-trump-to-block-critics-on-twitte

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/16/

opinion/michelle-carter-didnt-kill-with-a-text.html

http://www.npr.org/2017/06/04/

531314097/alt-right-white-nationalist-free-speech-

the-far-rights-language-explained

http://www.gocomics.com/phil-hands/2017/06/03

http://www.npr.org/2017/05/05/

527092506/states-consider-legislation-to-protect-free-speech-on-campus

http://www.npr.org/2017/02/26/

517086190/north-carolina-law-makes-facebook-a-felony-for-former-sex-offenders

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/07/us/

high-school-students-first-amendment.html

http://www.npr.org/2017/02/07/

513981813/appeals-court-considers-whether-to-lift-stay-on-immigration-order

2016

http://www.gocomics.com/marshallramsey/2016/11/30

http://www.gocomics.com/nickanderson/2016/11/30

http://www.gocomics.com/glennmccoy/2016/11/30

http://www.gocomics.com/claybennett/2016/11/30

http://www.npr.org/2016/10/26/

499442453/the-twitter-paradox-how-a-platform-designed-for-free-speech-

enables-internet-tro

http://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2016/03/22/

471416946/from-reagans-cyber-plan-to-apple-vs-fbi-everything-is-up-for-grabs

http://www.npr.org/2016/02/26/

468297955/apples-first-amendment-argument

2015

http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2015/11/02/

when-a-generation-becomes-less-tolerant-of-free-speech

http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2015/08/11/

431690567/court-strikes-down-new-hampshires-ban-on-selfies-in-the-voting-booth

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/02/

opinion/the-court-and-online-threats.html

http://www.npr.org/2015/03/23/

394308609/is-a-confederate-flag-license-plate-free-speech

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/12/us/

expulsion-of-two-oklahoma-students-leads-to-free-speech-debate.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/24/

opinion/why-tolerate-terrorist-publications.html

2014

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/02/

opinion/censorship-in-your-doctors-office.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/27/

opinion/the-supreme-court-was-right-to-allow-anti-abortion-protests.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/27/

opinion/a-unanimous-supreme-court-abortion-rights-lose-a-buffer.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/09/

opinion/sunday/the-uninhibited-press-50-years-later.html

http://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/2014/01/

first-amendment-case-brings-abortion-protesters-rights-before-supreme-court.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/12/us/

bloggers-incarceration-raises-first-amendment-questions.html

2013

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/10/

opinion/protecting-the-speech-we-hate.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/03/us/

politics/first-amendments-role-comes-into-question-as-leakers-are-prosecuted.html

2011

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/07/04/

what-does-the-first-amendment-protect/

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/28/us/

28scotus.html

http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/03/02/us-

usa-military-funerals-factbox-idUSTRE7214RB20110302

http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/03/02/us-

usa-military-funerals-idUSTRE7213R320110302

2010

http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2010/10/06/

free-speech-and-picketing-funerals

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/07/

opinion/07thu1.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/22/

opinion/22tue1.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/16/us/

politics/16court.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/24/

opinion/24sat1.html

2009

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/07/us/

07scotus.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/23/us/

23bar.html

free

speech / freedom of speech

https://constitution.findlaw.com/amendment1.html

https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/billofrights

https://memory.loc.gov/ammem/help/constRedir.html

https://bancroft.berkeley.edu/FSM/

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/04/

opinion/04stone.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/16/

business/16tobacco.html

press freedom

https://www.npr.org/2023/08/14/

1193676139/newspaper-marion-county-kansas-police-raid-first-amendment

on free-speech grounds

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/16/

business/16tobacco.html

on First Amendment grounds

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/28/us/

28scotus.html

comply with the

First Amendment

free-speech right

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-military-funerals/

supreme-court-allows-military-funeral-anti-gay-protests-idUSTRE7213R3

20110302

cancel culture

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/18/

opinion/cancel-culture-free-speech-poll.html

Corpus of news articles

USA > U.S. Constitution

First Amendment > Free speech - 1791

Why Tolerate

Terrorist Publications?

JAN. 23, 2015

The New York Times

The Opinion Pages

Op-Ed Contributor

By MARTIN LONDON

WHILE most of us would agree that religious fundamentalists,

foreign and domestic, sometimes do serious harm to our society, there are other

kinds of fundamentalists who are also dangerous: I refer to legal

fundamentalists.

More precisely, the tranche of lawyers, academicians, journalists and publishers

who, over the years, have developed into First Amendment fundamentalists and

have become a powerful influence on our government. Currently, they appear to

have persuaded our attorney general that the amendment bars him from taking

action against Inspire magazine, published on the Internet by Al Qaeda in the

Arabian Peninsula.

The organization is a sworn enemy of the United States, and its web publication

is available throughout the land. The online magazine proclaims its goals of

providing inspiration and justification to inflict harm on the United States as

well as Britain, France and other countries, by killing its citizens, preferably

in large numbers. It encourages its readers to engage in attacks.

Photo

Credit Mike McQuade

The magazine has given instructions for building car bombs as well as

pressure-cooker bombs using material from a kitchen or a hardware store. Those

instructions were followed to the letter by the Tsarnaev brothers, who murdered

three and sent 264 to hospitals in the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing.

It also — in its issue this past Christmas Eve — shared a new bomb recipe aimed

at bringing down civilian airliners. According to Inspire, the new bomb would

not be detected by the Transportation Security Administration metal detectors,

only potentially by sniffer machines. But even if detected, the bomb probably

wouldn’t be discovered, the publication says, without probing into orifices that

a T.S.A. officer might be reluctant to visit.

In Britain, possession of the online magazine is a crime. Is this publication

protected by our First Amendment? Not on your life!

In 1791, our forebears, anxious lest the new government adopt some of the

restrictions that had been imposed by the king, adopted a basic commandment

barring the government from making any law “abridging the freedom of speech.”

Does that mean what it says? Obviously not, because we have adopted many laws

abridging speech, such as in cases of child porn, perjury, false representation,

libel and slander, criminal conspiracy, etc. The list is substantial. When it

comes to political speech, how do we distinguish the good speech from the bad?

We look to bedrock principles.

For example, threats are not protected because they provide no social value. The

idea behind the First Amendment, wrote the founders, was that the citizens be

free to criticize their government. And over the next several centuries, our

courts have developed a great body of law refining and expanding that concept.

In the area of national security and politics, there are no wrong ideas, and

free speech is indispensable to the disclosure of truth.

The most recent and most expansive Supreme Court decision on protected speech in

the context of national security was the Brandenburg case in 1969, which struck

down an Ohio law that criminalized advocacy of crime, violence or terrorism as a

means of accomplishing political reform. The statute was unconstitutional, the

court said, because political speech is protected unless it is “directed to

inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce

such action.” Because this Ohio statute did not adequately distinguish between

abstract advocacy versus true incitement to imminent action, the conviction of

Clarence Brandenburg, a Ku Klux Klan leader, was reversed.

In looking at the question of what speech is protected and what is not, courts

have always looked to context. For example, every Supreme Court decision on this

subject recognizes war as an exception to the First Amendment, even though the

Constitution says no such thing. The classic example cited by the older cases is

recognition of the government’s unfettered right, in time of war, to ban the

publication of information revealing the sailing dates of troop transports. Ten

years after Brandenburg, a district judge in the United States v. Progressive

case enjoined the publication of classified nuclear bomb formulas. The court

found that times had changed, war was no longer limited to foot soldiers who

travel to battle sites on troop transports, and even though it was not clear

that a reader would imminently “build a hydrogen bomb in the basement,” the

scope of the danger overwhelmed the imminence factor.

The balancing act was succinctly explained by Robert W. Warren, the district

court chief judge who, when referring to Patrick Henry’s famous liberty-or-death

choice, explained, “in the short run, one cannot enjoy freedom of speech,

freedom to worship, freedom of the press unless one first enjoys the freedom to

live.”

The balancing test must look at what is real. The measurement of imminence

changes when we are talking about detonating a nuclear bomb in New York City as

opposed to an unlicensed rally blocking the Brooklyn Bridge.

The federal government should move decisively to block Inspire on the web. It is

criminal incitement that has produced lawless action, and no sentient judge

would today say otherwise.

It is one thing for Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. to excuse the journalist

James Risen from revealing a book source, and quite another to permit virulent

enemies to recruit, train and support those who would destroy our country. If we

sanction this kind of so-called freedom, we risk horrible consequences. The

Paris bombing is small stuff compared with what would happen if our civilian

airline system were crippled. I fear that in response to more terrorism, we

would see repression on a terrifying scale.

Martin London,

of counsel to the law firm

Paul, Weiss, Rifkind,

Wharton & Garrison,

has litigated First Amendment issues.

A version of this op-ed appears in print

on January 24, 2015,

on page A19 of the

New York edition

with the headline:

Why Tolerate Terrorist Publications?.

Why Tolerate Terrorist Publications?,

NYT,

JAN 23, 2015,

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/24/

opinion/why-tolerate-terrorist-publications.html

Let’s Give Up on the Constitution

December 30, 2012

The New York Times

By LOUIS MICHAEL SEIDMAN

Washington

AS the nation teeters at the edge of fiscal chaos, observers are reaching the

conclusion that the American system of government is broken. But almost no one

blames the culprit: our insistence on obedience to the Constitution, with all

its archaic, idiosyncratic and downright evil provisions.

Consider, for example, the assertion by the Senate minority leader last week

that the House could not take up a plan by Senate Democrats to extend tax cuts

on households making $250,000 or less because the Constitution requires that

revenue measures originate in the lower chamber. Why should anyone care? Why

should a lame-duck House, 27 members of which were defeated for re-election,

have a stranglehold on our economy? Why does a grotesquely malapportioned Senate

get to decide the nation’s fate?

Our obsession with the Constitution has saddled us with a dysfunctional

political system, kept us from debating the merits of divisive issues and

inflamed our public discourse. Instead of arguing about what is to be done, we

argue about what James Madison might have wanted done 225 years ago.

As someone who has taught constitutional law for almost 40 years, I am ashamed

it took me so long to see how bizarre all this is. Imagine that after careful

study a government official — say, the president or one of the party leaders in

Congress — reaches a considered judgment that a particular course of action is

best for the country. Suddenly, someone bursts into the room with new

information: a group of white propertied men who have been dead for two

centuries, knew nothing of our present situation, acted illegally under existing

law and thought it was fine to own slaves might have disagreed with this course

of action. Is it even remotely rational that the official should change his or

her mind because of this divination?

Constitutional disobedience may seem radical, but it is as old as the Republic.

In fact, the Constitution itself was born of constitutional disobedience. When

George Washington and the other framers went to Philadelphia in 1787, they were

instructed to suggest amendments to the Articles of Confederation, which would

have had to be ratified by the legislatures of all 13 states. Instead, in

violation of their mandate, they abandoned the Articles, wrote a new

Constitution and provided that it would take effect after ratification by only

nine states, and by conventions in those states rather than the state

legislatures.

No sooner was the Constitution in place than our leaders began ignoring it. John

Adams supported the Alien and Sedition Acts, which violated the First

Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of speech. Thomas Jefferson thought every

constitution should expire after a single generation. He believed the most

consequential act of his presidency — the purchase of the Louisiana Territory —

exceeded his constitutional powers.

Before the Civil War, abolitionists like Wendell Phillips and William Lloyd

Garrison conceded that the Constitution protected slavery, but denounced it as a

pact with the devil that should be ignored. When Abraham Lincoln issued the

Emancipation Proclamation — 150 years ago tomorrow — he justified it as a

military necessity under his power as commander in chief. Eventually, though, he

embraced the freeing of slaves as a central war aim, though nearly everyone

conceded that the federal government lacked the constitutional power to disrupt

slavery where it already existed. Moreover, when the law finally caught up with

the facts on the ground through passage of the 13th Amendment, ratification was

achieved in a manner at odds with constitutional requirements. (The Southern

states were denied representation in Congress on the theory that they had left

the Union, yet their reconstructed legislatures later provided the crucial votes

to ratify the amendment.)

In his Constitution Day speech in 1937, Franklin D. Roosevelt professed devotion

to the document, but as a statement of aspirations rather than obligations. This

reading no doubt contributed to his willingness to extend federal power beyond

anything the framers imagined, and to threaten the Supreme Court when it stood

in the way of his New Deal legislation. In 1954, when the court decided Brown v.

Board of Education, Justice Robert H. Jackson said he was voting for it as a

moral and political necessity although he thought it had no basis in the

Constitution. The list goes on and on.

The fact that dissenting justices regularly, publicly and vociferously assert

that their colleagues have ignored the Constitution — in landmark cases from

Miranda v. Arizona to Roe v. Wade to Romer v. Evans to Bush v. Gore — should

give us pause. The two main rival interpretive methods, “originalism” (divining

the framers’ intent) and “living constitutionalism” (reinterpreting the text in

light of modern demands), cannot be reconciled. Some decisions have been

grounded in one school of thought, and some in the other. Whichever your

philosophy, many of the results — by definition — must be wrong.

IN the face of this long history of disobedience, it is hard to take seriously

the claim by the Constitution’s defenders that we would be reduced to a

Hobbesian state of nature if we asserted our freedom from this ancient text. Our

sometimes flagrant disregard of the Constitution has not produced chaos or

totalitarianism; on the contrary, it has helped us to grow and prosper.

This is not to say that we should disobey all constitutional commands. Freedom

of speech and religion, equal protection of the laws and protections against

governmental deprivation of life, liberty or property are important, whether or

not they are in the Constitution. We should continue to follow those

requirements out of respect, not obligation.

Nor should we have a debate about, for instance, how long the president’s term

should last or whether Congress should consist of two houses. Some matters are

better left settled, even if not in exactly the way we favor. Nor, finally,

should we have an all-powerful president free to do whatever he wants. Even

without constitutional fealty, the president would still be checked by Congress

and by the states. There is even something to be said for an elite body like the

Supreme Court with the power to impose its views of political morality on the

country.

What would change is not the existence of these institutions, but the basis on

which they claim legitimacy. The president would have to justify military action

against Iran solely on the merits, without shutting down the debate with a claim

of unchallengeable constitutional power as commander in chief. Congress might

well retain the power of the purse, but this power would have to be defended on

contemporary policy grounds, not abstruse constitutional doctrine. The Supreme

Court could stop pretending that its decisions protecting same-sex intimacy or

limiting affirmative action were rooted in constitutional text.

The deep-seated fear that such disobedience would unravel our social fabric is

mere superstition. As we have seen, the country has successfully survived

numerous examples of constitutional infidelity. And as we see now, the failure

of the Congress and the White House to agree has already destabilized the

country. Countries like Britain and New Zealand have systems of parliamentary

supremacy and no written constitution, but are held together by longstanding

traditions, accepted modes of procedure and engaged citizens. We, too, could

draw on these resources.

What has preserved our political stability is not a poetic piece of parchment,

but entrenched institutions and habits of thought and, most important, the sense

that we are one nation and must work out our differences. No one can predict in

detail what our system of government would look like if we freed ourselves from

the shackles of constitutional obligation, and I harbor no illusions that any of

this will happen soon. But even if we can’t kick our constitutional-law

addiction, we can soften the habit.

If we acknowledged what should be obvious — that much constitutional language is

broad enough to encompass an almost infinitely wide range of positions — we

might have a very different attitude about the obligation to obey. It would

become apparent that people who disagree with us about the Constitution are not

violating a sacred text or our core commitments. Instead, we are all invoking a

common vocabulary to express aspirations that, at the broadest level, everyone

can embrace. Of course, that does not mean that people agree at the ground

level. If we are not to abandon constitutionalism entirely, then we might at

least understand it as a place for discussion, a demand that we make a

good-faith effort to understand the views of others, rather than as a tool to

force others to give up their moral and political judgments.

If even this change is impossible, perhaps the dream of a country ruled by “We

the people” is impossibly utopian. If so, we have to give up on the claim that

we are a self-governing people who can settle our disagreements through mature

and tolerant debate. But before abandoning our heritage of self-government, we

ought to try extricating ourselves from constitutional bondage so that we can

give real freedom a chance.

Louis Michael Seidman,

a professor of constitutional law

at Georgetown

University,

is the author of the forthcoming book

“On Constitutional Disobedience.”

Let’s Give Up on the Constitution,

NYT,

30.12.2012,

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/31/

opinion/lets-give-up-on-the-constitution.html

The First Amendment,

Upside Down

June 27, 2011

The New York Times

The Supreme Court decision striking down public matching funds in Arizona’s

campaign finance system is a serious setback for American democracy. The opinion

written by Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. in Monday’s 5-to-4 decision shows

again the conservative majority’s contempt for campaign finance laws that aim to

provide some balance to the unlimited amounts of money flooding the political

system.

In the Citizens United case, the court ruled that the government may not ban

corporations, unions and other moneyed institutions from spending in political

campaigns. The Arizona decision is a companion to that destructive landmark

ruling. It takes away a vital, innovative way of ensuring that candidates who do

not have unlimited bank accounts can get enough public dollars to compete

effectively.

Arizona’s campaign finance law provided a set amount of money in initial public

support for candidates who opted into its financing system, depending on the

type of election. If a candidate faced a rival who opted out, the state would

match the spending of the privately financed candidate and independent groups

supporting him, up to triple the initial amount. Once that limit is reached, the

publicly financed candidate receives no other public funds and is barred from

using private contributions, no matter how much more the privately financed

candidate spends.

Chief Justice Roberts found that this mechanism “imposes a substantial burden”

on the free speech rights of candidates and independent groups because it

penalized them when their spending triggered additional money for a candidate

who opted into the public program. The court turns the First Amendment on its

head. It denies the actual effect of the Arizona law, which is not to limit

spending but to increase it with public funds. The state program expands

political speech by giving all candidates, not just the wealthy, a chance to run

— while allowing privately financed candidates to spend as much as they want.

Justice Elena Kagan, writing in dissent, dissects the court’s willful

misunderstanding of the result. Rather than a restriction on speech, she says,

the trigger mechanism is a subsidy with the opposite effect: “It subsidizes and

produces more political speech.” Those challenging the law, she wrote, demanded

— and have now won — the right to “quash others’ speech” so they could have “the

field to themselves.” She explained that the matching funds program — unlike a

lump sum grant to candidates — sensibly adjusted the amount disbursed so that it

was neither too little money to attract candidates nor too large a drain on

public coffers.

Arizona’s system was a response to a history of terrible corruption in the

state’s politics. Rather than seeing the law as a way to control corruption, the

court struck it down as a limit on the right of wealthy candidates and

independent groups to speak louder than others.

The ruling left in place other public financing systems without such trigger

provisions, including public financing for presidential elections. It shows,

however, how little the court cares about the interest of citizens in Arizona or

elsewhere in keeping their electoral politics clean.

The First Amendment,

Upside Down,

NYT,

27.6.2011,

https://www.nytimes.com/2011/06/28/

opinion/28tue1.html

A Bruise on the First Amendment

June 21, 2010

The New York Times

Forty-three years ago, when the nation lived in fear of Communist

sympathizers and saboteurs, the Supreme Court said that even the need for

national defense could not reduce the First Amendment rights of those

associating with American Communists.

On Monday, in the first case since the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks to test free

speech against the demands of national security in the age of terrorism, the

ideals of an earlier time were eroded and free speech lost. By preserving an

extremely vague prohibition on aiding and associating with terrorist groups, the

court reduced the First Amendment rights of American citizens.

The case was not about sending money to terrorist organizations or serving as

their liaison, activities that are clearly and properly illegal. And it did not

stop people from simply saying they support the goals of groups like Hamas or Al

Qaeda, as long as they are not actually working with those groups. But it could

have a serious impact on lawyers, journalists or academics who represent or

study terrorist groups.

The case arose after an American human rights group, the Humanitarian Law

Project, challenged the law prohibiting “material support” to terror groups,

which was defined in the 2001 Patriot Act to include “expert advice or

assistance.” The law project wanted to provide advice to two terrorist groups on

how to peacefully resolve their disputes and work with the United Nations. The

two groups — the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam and the Kurdistan Workers’

Party — have violent histories and their presence on the State Department’s

official list of terrorist groups is not in dispute.

But though the law project was actually trying to reduce the violence of the two

groups, the court’s opinion, written by Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. on behalf

of five other justices, said that did not matter and ruled the project’s efforts

illegal. Even peaceful assistance to a terror group can further terrorism, the

chief justice wrote, in part by lending them legitimacy and allowing them to

pretend to be negotiating while plotting violence.

In a powerful dissent, Justice Stephen Breyer, also speaking for Justices Ruth

Bader Ginsburg and Sonia Sotomayor, swept away those arguments. If providing

legitimacy to a terror group was really a crime, he wrote, then it should also

be a crime to independently legitimize a terror group through speech, which it

is not. Never before, he said, had the court criminalized a form of speech on

these kinds of grounds, noting with particular derision the notion that peaceful

assistance buys negotiating time for an opponent to achieve bad ends.

The court at least clarified that acts had to be coordinated with terror groups

to be illegal, but many forms of assistance may still be a criminal act,

including filing a brief against the government in a terror-group lawsuit.

Academic researchers doing field work in conflict zones could be arrested for

meeting with terror groups and discussing their research, as could journalists

who write about the activities and motivations of these groups, or the

journalists’ sources. The F.B.I. has questioned people it suspected as being

sources for a New York Times article about terrorism, and threatened to arrest

them for providing material support.

There remains a reasonable way of resolving these disputes. Justice Breyer

proposed a standard that would criminalize this kind of speech or association

“only when the defendant knows or intends that those activities will assist the

organization’s unlawful terrorist actions.” Because he was unable to persuade a

majority on the court, Congress needs to enact this standard into law.

A Bruise on the First

Amendment,

NYT,

21.6.2010,

https://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/22/

opinion/22tue1.html

Explore more on these topics

Anglonautes > Vocapedia

law > USA > U.S. Constitution

law > USA > U.S. Supreme Court,

Justices,

State Supreme Courts

technology > WikiLeaks

technology > Wikileaks > Julian Assange

free press, censorship

media, press,

newspapers, magazines,

radio, podcasting, TV,

journalism,

photojournalism, journalist safety,

free speech,

free press,

fake news,

misinformation,

disinformation,

cartoons, illustrations,

advertising

Internet

freedom, censorship

social

media,

influencers, fake news,

disinformation,

misinformation

publishing industry,

ban, censorship

justice, law, death penalty,

U.S. Constitution, U.S. Supreme Court > USA

Anglonautes >

History > 20th century > USA

Vietnam war > The Pentagon Papers - 1971

Vietnam war

opponents >

Pentagon Papers 1971-1973 >

Daniel Ellsberg (1931-2023)

Richard Nixon

(1913-1994),

Watergate 1972-1974

Richard Milhous Nixon (1913-1994)

37th President of the United States 1969-1974

Historical

documents > USA

|